Abstract

To gain insight into the molecular regulation of human heart development, a detailed comparison of the mRNA and miRNA transcriptomes across differentiating human-induced pluripotent stem cell (hiPSC)–derived cardiomyocytes and biopsies from fetal, adult, and hypertensive human hearts was performed. Gene ontology analysis of the mRNA expression levels of the hiPSCs differentiating into cardiomyocytes revealed 3 distinct groups of genes: pluripotent specific, transitional cardiac specification, and mature cardiomyocyte specific. Hierarchical clustering of the mRNA data revealed that the transcriptome of hiPSC cardiomyocytes largely stabilizes 20 days after initiation of differentiation. Nevertheless, analysis of cells continuously cultured for 120 days indicated that the cardiomyocytes continued to mature toward a more adult-like gene expression pattern. Analysis of cardiomyocyte-specific miRNAs (miR-1, miR-133a/b, and miR-208a/b) revealed an miRNA pattern indicative of stem cell to cardiomyocyte specification. A biostatistitical approach integrated the miRNA and mRNA expression profiles revealing a cardiomyocyte differentiation miRNA network and identified putative mRNAs targeted by multiple miRNAs. Together, these data reveal the miRNA network in human heart development and support the notion that overlapping miRNA networks re-enforce transcriptional control during developmental specification.

Introduction

Ethical and technical difficulties make examining early events in human development difficult, if not impossible. Human-induced pluripotent stem cells (hiPSCs) are a promising model to help bridge this gap and provide an understanding of the molecular events guiding early human development [1]. In this light, a major advantage of hiPSC-derived tissues over primary tissue is their ability to maintain functional properties in vitro and to be reproducibly expanded to produce tissue from a defined genetic background. These properties, and their ability to differentiate into any adult tissue, make hiPSCs an attractive therapeutic target for tissue replacement therapies, and as an in vitro system for drug development and discovery [2,3].

One key regulator of mammalian development is the miRNAs, which are short, ∼22 nucleotide RNAs that posttranscriptionally silence hundreds to thousands of target mRNAs [4]. The critical developmental role of miRNAs can be inferred from the finding that deletion of a number of genes in the miRNA biogenesis pathway results in early embryonic lethality [5,6]. Individual miRNAs inhibit the translation and/or destabilize the mRNA, through miRNA targets typically located in the 3′ untranslated region (UTR), although increasing evidence suggests that miRNA target sites in other regions of the mRNA can modulate expression. The precise mechanism of target identification is not completely understood; however, a number of rules have been determined, including the seed sequence from position 2–7 of the miRNA that requires perfect complementarity to the target mRNA [7].

The developmental role of individual miRNAs has been extensively studied in mouse cardiomyogenesis. A number of miRNAs have been implicated in the development and homeostasis of the mammalian heart [8,9]: mir-1, mir-133a/b, mir-143, mir-145, and mir-208a/b. For instance, the loss of 1 of the 2 genomic mir-1 loci (mir-1–2) in the mouse results in cardiac morphogenic and electrophysiology defects such as ventricular septation defects, decreased heart rate, and prolongation of ventricular depolarization [10]. In addition to their role in heart development, the dysregulation of these miRNAs, as well as several others, has been observed in human diseases, including chronic heart failure, hypertension, myocardial infarcts, and hypertrophy [9].

The differentiation of hiPSCs to cardiomyocytes has been reported by a number of groups and is perhaps the most well-studied hiPSC-derived tissue [11–14]. A number of specific molecular markers (NKX2-5, cardiac troponins cTnI/cTnT/cTnC, and α/β myosin heavy chains) have been leveraged to aid in the purification of hiPSC-derived cardiomyocytes [15,16]. Given the voltage-dependent contractile nature of cardiomyocytes, the observation of spontaneous beating and the ability to quantitatively measure the electrophysiology of these cells provide a robust means of phenotypic characterization [17].

To better understand the molecular regulation of human cardiomyogenesis, both mRNA and miRNA expression levels were determined by microarray using a fine-scale timeline of differentiation. Comparison of the mRNA profile to both human fetal and adult heart samples revealed that the hiPSC-derived cardiomyocytes progressively mature toward a more adult-like phenotype during extended culture. Next, all possible anticorrelated, differentially expressed mRNA/miRNA pairs were examined for their predicted miRNA targets. A network of overlapping targets for each miRNA was developed in an unbiased, unsupervised manner. This analysis resulted in 2 independent miRNA networks: one associated with the pluripotent state, which contained known pluripotent miRNAs, and a second associated with known cardiomyocyte miRNAs. This method was able to identify all previously known heart-development miRNAs as well as some miRNAs not previously associated with cardiac development. Thus, the integration of miRNA and mRNA transcript profiling of hiPSC-derived cardiomyocytes is a useful means of gleaning novel information about human cardiac development.

Materials and Methods

Cardiomyocyte differentiation

hiPSC generation, genetic engineering, and cardiomyocyte differentiation were carried out as described [18]. Briefly, hiPSCs were generated from a human fibroblast cell line via reprogramming through retroviral expression of SOX2, OCT4, NANOG, and LIN28 [19]. A single clone from this reprogramming step was propagated and subjected to genetic engineering to enable cardiomyocyte enrichment through drug selection. A fusion of the blasticidin resistance gene (BSD) encoding Blasticidin S Deaminase from Aspergillus terreus fused to the mRFP1 red fluorescent protein gene (Clontech, Mountain View, CA) was inserted into the MYH6 locus downstream of the MYH6 open reading frame using methods similar to Klug and colleagues [20]. The expression construct contained a picornovirus 2A linker sequence [21] between the MYH6 open reading frame and the blasticidin resistance/mRFP1 fusion gene to enable bicistronic expression of the proteins. Analysis of genomic DNA across the homology arms of the recombination construct using polymerase chain reaction (PCR) identified an hiPSC clone that was correctly targeted at the MYH6 locus. This hiPSC clone was propagated and maintained in feeder-free culture using mTeSR1® (Stem Cell Technologies, Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada) on a Matrigel™ substrate (Beckton Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, NJ). These hiPSCs were formed into aggregates and cultured in differentiation medium containing 100 ng/mL zebrafish basic fibroblast growth factor and 10% fetal bovine serum prior to the differentiation of cardiac myocytes. On day 14 of differentiation, the cultures were subjected to blasticidin selection (25 μg/mL) to purify the cardiomyocyte population (see Supplementary Fig. S1; Supplementary Data are available online at www.liebertonline.com/scd). Following blasticidin selection, cultures were maintained in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium containing 10% fetal bovine serum for the duration of the cultures. On days 0, 3, 7, 10, 14, 20, 28, 35, 45, 60, 90, and 120, approximately 3 million cells were removed for RNA collection. The differentiation protocol and sample collection were performed in 3 independent replicates as indicated by Run 1, 2, and 3 in Figs. 1 and 3.

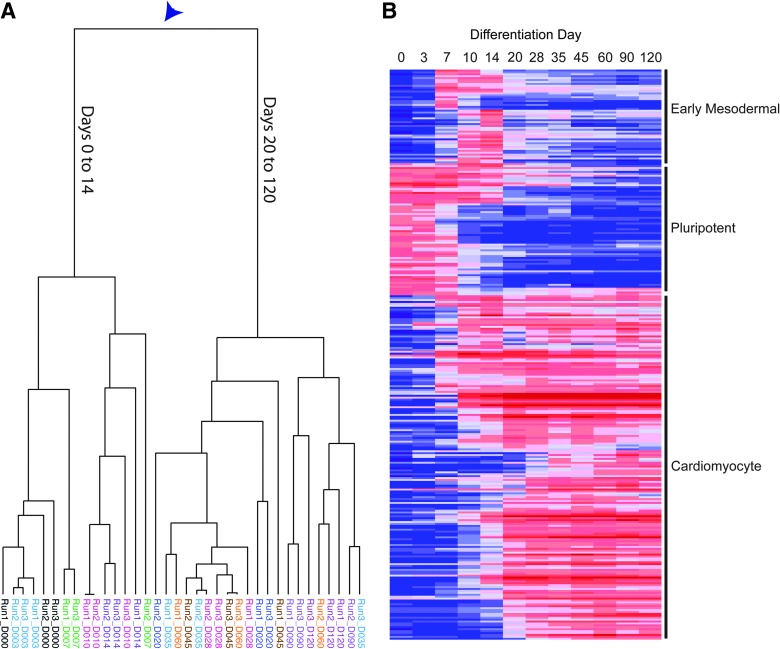

FIG. 1.

The differentiation time course from human-induced pluripotent stem cells (hiPSCs) to cardiomyocytes. Three independent differentiations were performed (Run 1, 2, and 3), and RNA was sampled at days 0, 3, 7, 10, 14, 20, 25, 35, 45, 60, 90, and 120 days. (A) Dendogram of all independent samples derived from unsupervised hierarchical clustering. Arrowhead shows location of important bifurcation. (B) Heat map of expression of the 298 differentially expressed genes.

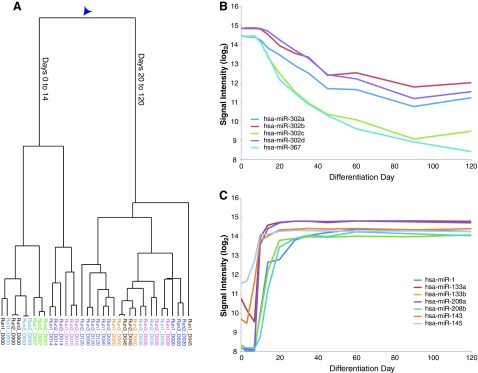

FIG. 3.

miRNA expression profiles during cardiomyocyte differentiation. (A) Dendogram of all independent samples derived from unsupervised hierarchical clustering. Arrowhead shows location of important bifurcation. (B) The expression profile of the pluripotency-associated hsa-mir-302 cluster. (C) The expression profile of miRNAs involved in mammalian heart development (hsa-mir-1, hsa-mir-133a/b, hsa-mir-208a/b, hsa-mir-143, and hsa-mir-145).

Gene expression profiling

Total RNA from hiPSC-derived cardiomyocytes was isolated using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) according to the manufacturer's protocol. Adult and fetal human total RNAs were purchased (Ambion, Austin, TX, and Clontech). Primary cardiomyocyte cultures were purchased from 3 manufacturers: Promocell Passage 5 (Promocell, Heidelberg, Germany), Celprogen Passage 4 (Celprogen, San Pedro, CA), and Sciencell Passage 12 (Sciencell, Carlsbad, CA). Gene expression microarray experiments were conducted on Illumina HumanWG6-V3 BeadChip (Illumina, San Diego, CA) containing 48,804 probes derived from human genes in the NCBI RefSeq and UniGene databases. Five hundred nanograms of total RNA was amplified and biotinylated using the TotalPrep RNA amplification kit (Ambion). For each sample, 1.5 μg of labeled cRNAs was hybridized onto human beadchip using the Illumina whole-genome gene expression direct hybridization protocol. The beadchips were scanned using Illumina iScan and the signal intensity was measured. All microarray data were deposited in gene expression omnibus (GEO).

Quantitative reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction

Cryopreserved cardiomyocytes (Cellular Dynamics International, Madison, WI) were plated according to the manufacturer's instructions in a 384-well plate. On days 2, 6, 10, and 14 postplating (equivalent to days 34, 40, 42, and 46 days postdifferentiation), RNA was collected with the Cells-to-Ct kit (Invitrogen) according to manufacturer's instructions. CASQ2 (Hs00154286_m1), CKMT2 (Hs00176502_m1), COX6A2 (Hs00193226_g1), CRYAB (Hs00157107_m1), and PPIA (4333763F) Taqman probes were used for analysis (ABI, Foster City, CA). qPCR was performed on the Fluidigm Biomark HD (Fluidigm, South San Francisco, CA) with ABI 2× qPCR master mix as per manufacturer's instructions (ABI, Foster City, CA). Expression was calculated using the ΔΔCt method with each gene normalized to PPIA [22].

miRNA microarray profiling

miRNA profiling experiments were performed on the Illumina 12-sample Universal BeadChip (Illumina) that cover the expression of 1,146 miRNAs described in the miRBase database as well as novel targets identified with Illumina sequencing. Eight hundred nanograms of total RNA was polyadenylated allowing cDNA conversion using Illumina Human v2 microRNA expression profiling kit (Illumina). The cDNA pool was then amplified using miRNA-specific oligos and fluorescently labeled in order to allow measurement of the signal intensity with the Illumina iScan. miRNA microarrays were run in triplicate across 12 time points. Temporally altered miRNAs and mRNAs were determined within each dataset using the time course package in R [23], with the top differentially expressed genes and miRNAs being determined using a Hotelling's t-statistic [24]. All microarray data were deposited in GEO.

Microarray analysis

For both gene expression and miRNA profiling, data analysis was performed using Partek® Genomics Suite software, version 6.5 (Partek, Inc., St. Louis, MO). Significant differentially expressed genes were identified for a P value [false discovery rate (FDR)] of 0.05 and a fold-change of 10 and 2.5 for mRNA and miRNA data, respectively. Gene ontology (GO) analysis and hierarchical clustering were carried out using Roche in-house applications.

Cardiac-specific gene signature

The 203 gene specific list was determined using the Genomic Institute of the Novartis Research Foundation (GNF) expression atlas [25]. A gene was considered cardiac specific if the cardiac expression was (≥10× the median tissue expression, and the rank order of the heart expression was either 1, 2, or 3 relative to other tissues. GO analysis was performed with GATHER [26] and clustering was performed with Genepattern [27].

Correlating miRNA and mRNA expression data

Pearson correlations were calculated for all possible pairs of miRNA and mRNAs from microarray expression data. Inversely correlated miRNA-mRNA pairs (R<−0.8) for the top 200 temporally differentially expressed miRNAs were cross-referenced with an internally curated database of miRNA targets. The target prediction database was developed by using the TargetScan prediction algorithm [28] with a custom set of species to determine target binding conservation. Results from this analysis yielded a set of predicted miRNA targets of 119 out of the top 200 having expression values negatively correlated to differentially expressed miRNAs within this dataset.

Generating networks of miRNAs

To determine functional relationships between temporally altered miRNAs, we compiled the set of negatively correlated predicted mRNA targets for each of the top 200 differentially expressed miRNAs within this dataset. One hundred and nineteen out of the top 200 miRNAs had expression negatively correlated with mRNAs, which were also predicted to be targets of these miRNAs. We calculated the intersection of the targets of all possible pairs of these 119 miRNAs and determined the statistical significance of the percentage of overlapping targets of each pair using a hypergeometric test. A score for the percentage of overlapping targets between a pair of miRNAs was then determined by taking the negative log of the adjusted hypergeometric P value:

|

An miRNA network was subsequently generated using cytoscape (www.cytoscape.org), with nodes representing individual miRNAs and edges indicating the target overlap score between any 2 miRNAs. The most interconnected subnetworks within the larger miRNA network were determined using the MCode algorithm [29].

Computational analysis of predicted miRNA targets

GO analysis was performed on sets of negatively correlated predicted targets of individual miRNAs using the Pathway Studio 7.1 software suite (Ariadne Genomics, Rockville, MD) to determine common biological functions across sets of miRNA targets. Enrichment of miRNA targets within a gene set was similarly determined in Pathway Studio. Significance of enrichment of GO categories and miRNA targets was determined by a Fisher's exact test as implemented in Pathway Studio.

Results

Differentiation of hiPSCs to cardiomyocytes results in a stable, heart-like transcriptional phenotype

The transcriptome of hiPSC-derived cardiomyocytes was examined using expression profiling on a finely delineated timescale. Samples were taken during the differentiation from iPS to cardiomyocytes over a 120-day period, spanning 7 initial time points—days 0, 3, 7, 10, 14, 20, and 28—and 5 postdifferentiation time points—35, 45, 60, 90, and 120. Beating was first observed on day 14 and continued throughout the time course. This analysis was performed on 3 independent differentiations. Unsupervised hierarchical clustering of the samples (signal intensity across all genes) revealed a major branch point separating days 0 to 14 and days 20 to 120 (Fig. 1A). This branch point corresponds with the onset of the antibiotic selection at day 14 that is used to purify MYH6-positive cardiomyocytes. Fluorescence-activated cell sorting analysis of MYH6-RFP revealed a rapid increase in the cell purity from 16% RFP+ cells at day-14 preselection to 94% RFP+ at day 28 (Supplementary Fig. S1). Thus, the branch point may not reflect changes in developmentally regulated genes occurring from day 14 to day 20 of differentiation, but may simply reflect the dramatic increase in the purity of cardiomyocyte population. Indeed, these postselection datasets may represent the transcriptomes of the most highly purified population of hiPSC-derived cardiomyocytes reported to date. Furthermore, the close relationship of postselection samples from day 20 to day 120 indicates that once initiated, the cardiomyocyte gene expression is highly stable.

Self-organizing maps of the most highly expressed genes (10-fold above background, FDR <0.05) revealed 3 prominent classes of genes, identified by the timing of maximal gene expression: pluripotent specific, early mesodermal, and cardiomyocyte specific (Fig. 1B and Supplementary Table S1). GO analysis was used to further characterize the pluripotency-related class of genes (stem cell maintenance and stem cell development, P<0.0001; Supplementary Table S2). These genes included several associated with pluripotency, such as the prototypical transcriptional network genes OCT4 (POU5F1) and SOX2. NANOG expression was enriched but absent from our list because it did not meet the 10-fold above background criteria (Supplementary Table S3). In addition to the pluripotency-associated transcription factors, a number of other genes known to be expressed in pluripotent stem cells were included in the list, such as DNMT3B, LIN28, LIN28B, SALL4, REX1, and JARID2 [30,31].

GO analysis revealed that the early mesodermal gene list was significantly associated with the GO term multicellular organismal development (P<3e-16), specifically of the mesoderm (mesoderm development, P<3e-7; Supplementary Table S2). Among the upregulated genes with this GO term included known mesoderm markers, such as MESP1, and endoderm markers, such as SOX17, DKK1, GATA5, and EOMES, which are consistent with a mesendoderm intermediate cell type [32,33]. The prototypical early mesoderm marker T-brachyury was similarly induced, but did not reach the 10-fold above background criteria required for inclusion in this analysis (Supplementary Table S3). Although the antibiotic selection of cardiomyocytes may confound the transient gene list, a majority of early mesoderm genes return to baseline prior to the addition of antibiotic.

Finally, GO analysis of the cardiomyocyte-specific genes revealed a strong enrichment for heart-specific genes (muscle contraction, P=6.94e-26; heart development, P=2.7e-16; heart contraction, P=1.69e-12; Supplementary Table S2). A number of critical heart genes were expressed, such as the transcription factor NKX2-5, the myosin heavy and light chains (MYH6, MYH7, MYL2, and MYL7), and the cardiac troponins (TNNI3, TNNT2, and TNNC1). Taken together, these data confirm that hiPSCs follow the predicted developmental programs as they differentiate toward cardiomyocytes: first, starting as undifferentiated cells, transitioning through a mesendoderm intermediate, and finally becoming terminally differentiated cardiomyocytes.

Maturation of hiPSC-derived cardiomyocytes over extended culture

Next, the RNA transcriptomes were profiled from whole human heart tissue, both fetal and adult, to serve as the base comparator for the hiPSC to cardiomyocyte differentiation. The RNAs were examined from 3 normal adult heart samples (total 1, total 2, left ventricle), 1 hypertensive heart (diseased), and 1 pooled fetal heart sample (fetal; Supplementary Table S3). The comparison of the human heart biopsies and hiPSC-derived cardiomyocytes was narrowed to genes specific to the heart such that expression differences in the most critical genes could be identified. The heart-specific gene signature list was compiled from the GNF human tissue-panel expression atlas [25] (See Materials and Methods section). This list contains 203 genes (Supplementary Table S4) and GO analysis confirmed the heart-specific nature (muscle contraction, muscle development, striated muscle contraction, regulation of heart contraction rate, all with P<0.0001; Supplementary Table S5). The expression levels for each of the 203 heart-specific genes were determined in the human heart samples, iPS to cardiomyocyte differentiation, and primary human cardiomyocyte cultures and hierarchically clustered cultures, showing high levels of expression in each heart sample (Supplementary Fig. S2). Primary cardiomyocyte cultures are dedifferentiated cells from the human heart that reenter the cell cycle, and these cells had poor expression of a number of critical heart genes. This finding calls into question their usefulness as a model for studying the heart.

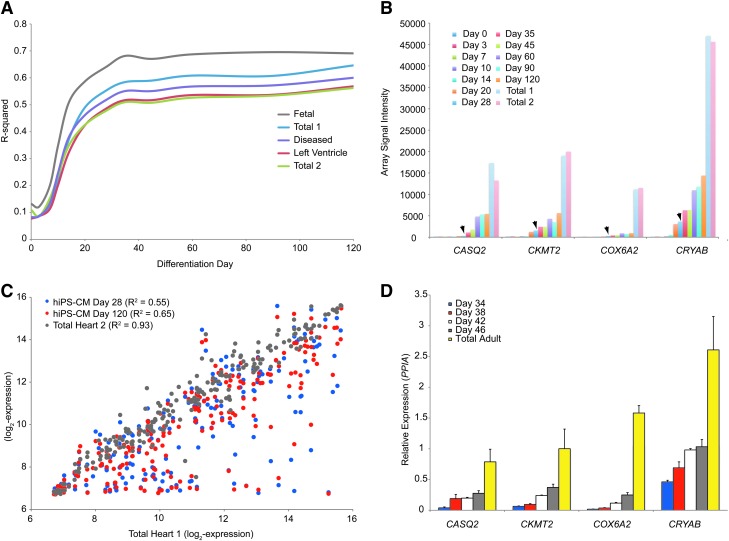

For each time point during the hiPSC differentiation, the expression levels for the genes on the heart signature list were compared with the human heart samples and Pearson correlation coefficients were calculated (Fig. 2A). As expected, essentially no correlation was observed between undifferentiated hiPSCs (day 0) and adult heart samples (R2=0.09). However, R2 values exponentially increased during the cardiomyocyte commitment phase of differentiation. Comparison of the time course hiPSC-derived cardiomyocytes to the fetal heart sample correlated well (Fig. 2A; R2=0.64 day 28 vs. fetal heart; R2=0.69 day 120 vs. fetal heart). The strong correlation between fetal heart and the iPS-derived cardiomyocytes was expected and has been observed in other examinations of pluripotent stem cells differentiating toward cardiomyocytes [16,34]. Once the cardiomyocyte population had been established, the R2 values continued to rise in a linear fashion when compared with the adult tissues (R2=0.55 day 28 vs. total 1; R2=0.65 day 120 vs. total 1). If this linear rise in correlation was to continue at a constant rate, an extrapolation predicts that the hiPSC-derived cardiomyocytes would converge with the adult heart expression profile after approximately 2 years (data not shown).

FIG. 2.

Cardiomyocytes continue to mature in extended culture. (A) R-squared values were computed between each of the 5 human heart RNAs and the differentiation days for the 203 heart-specific genes. Note the continued increase in R-squared after day 28. (B) Direct comparison of the heart-specific genes between a single total heart sample (total 1) and day 28 and day 120 of differentiation. (C) Analysis of 4 genes that continued to increase toward the adult level of expression in extended culture: CASQ2, CKMT2, COX6A2, and CRYAB. Shown are the array signal intensities for each of the days of differentiation and the 2 total adult heart RNAs. Arrowheads highlight day 28 expression. (D) Quantitative reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR) confirmation of the 4 genes. Expression is relative to PPIA. Each bar represents 16 wells (average±standard error of the mean).

An in-depth analysis of the gene expression level was performed on differentiation days 28 and 120 relative to the adult heart (total 1) (Fig. 2B). The heart-specific genes were rank-ordered by expression levels of the total heart RNA and the expression levels of days 28 and 120 were overlaid. A majority of the genes have similar levels of expression to human heart, with most genes remaining unchanged over the period of extended culture. However, several genes express a more adult heart–like expression level over time (Fig. 2C), suggesting that extended culture matures the cardiomyocytes. qRT-PCR analysis of these genes during an independent extended culture (days 34–46) revealed a similar pattern (Fig. 2D). Thus, these data suggest that during extended culture the cardiomyocytes continue to mature.

These maturity genes include CASQ2, whose forced overexpression in fetal-like hiPSC-derived cardiomyocytes results in a more mature calcium handling phenotype [35]. Beyond CASQ2, CRYAB and DESMIN (not shown) were identified as maturation genes. Desmin is a major intermediate filament protein in cardiomyocytes and CRYAB (αB-crystallin) is the chaperone for folding Desmin [36]. Desmin is expressed early in the heart during embryogenesis, but the levels of expression continue to increase during development [37]. Mutations in either protein result in myofibrillar myopathies [36]. Finally, genes involved in mitochondrial function were also found to increase over the time course—CKMT2, CKM (not shown), and COX6A2. COX6A2 is particularly relevant as it is the heart-specific subunit of the Cytochrome C complex [38]. This analysis reveals a number of genes maturing during extended culture that mimic heart development.

miRNA profiling during hiPSC differentiation

The expression of all known human miRNAs was measured across the entire time course of experiment to complement the mRNA expression data. The identical samples used for mRNA analysis were processed for miRNA arrays. Hierarchical clustering of the miRNA data revealed the major bifurcation between days 0 to 14 versus days 20 to 120 (Fig. 3A), similar to the clustering based on mRNA expression (Fig. 1A). These data suggest that during antibiotic purification of cardiomyocytes, the miRNA expression remains relatively stable.

The expression time course of miRNAs associated with pluripotency, differentiation, and heart development was analyzed to validate the expression data generated. The pluripotency-associated miR-302 cluster (miR-302a, -302b, -302c, -302d, and -367) declined over the differentiation time course (Fig. 3B), as expected [39,40]. Although the levels of the miRNAs never returned to baseline, even at 120 days, such residual miR-302 expression has been observed in other differentiation experiments [39,41,42]. The let-7 family of miRNAs, which reinforce the commitment to differentiation [43], also exhibited the expected expression pattern with the levels increasing during differentiation (Supplementary Fig. S3). Finally, the expression pattern of miRNAs previously shown to be important in heart development and disease was examined: developmentally regulated miR-1, miR-133a, miR-133b, miR-208a, miR-208b, miR-143, and miR-145 [8]; hypertrophy-associated miR-199a and miR-214 [44]; and a circulating serum biomarker of human myocardial infarction, miR-499 [45,46]. These miRNAs all followed the predicted patterns given their roles in cardiomyocyte function, disease, and development (Fig. 3C).

Defining the human cardiac developmental miRNA network

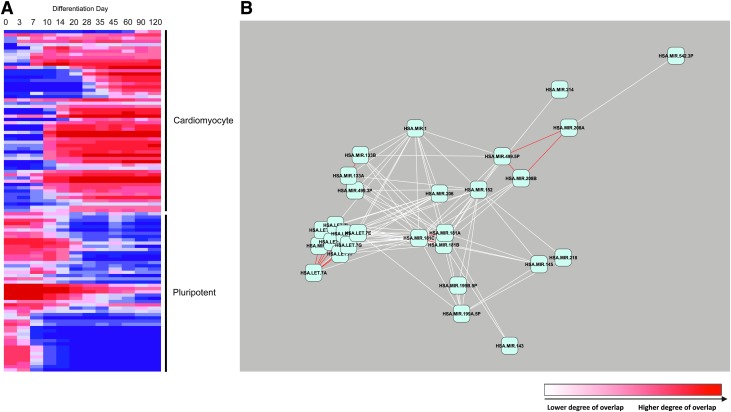

To better understand the role of miRNAs during cardiac development, the expression patterns of the predicted targets of differentially expressed miRNAs were examined. First, a list of differentially expressed miRNAs and mRNAs over the differentiation time course was computed. Hierarchical clustering of the 119 temporally regulated mature miRNAs identified 2 main groups, either pluripotency or cardiac (Fig. 4A). Since miRNAs generally downregulate expression of mRNA targets [47], potential miRNA/mRNA interactions were examined among the anticorrelated miRNA/mRNA expression pairs. Next, the computationally predicted targets of each miRNA [28] (see Materials and Methods section) were determined among the anticorrelated mRNAs to identify genes that maybe developmentally regulated by miRNAs. GO and pathway analysis of the predicted targets of the miRNAs identified enrichment in a number of developmentally important signaling pathways, including transforming growth factor-β, Notch, Hedgehog, fibroblast growth factor, and insulin-like growth factor (Supplementary Table S6). Additional categories identified included cell cycle categories, including G1-S transition and cell cycle arrest (Supplementary Table S6). These results are consistent with the exit from the cell cycle of cells upon terminal differentiation.

FIG. 4.

The cardiomyocyte miRNA differentiation network. Differentially expressed miRNAs and mRNAs were identified, and the computationally predicted miRNA/mRNA targets were computed for anticorrelated sets. The shared target overlap between miRNAs was calculated. (A) Heat map of expression of the 119 miRNAs that were differentially expressed segregates into 2 groups: pluripotent and cardiomyocyte differentiated. (B) The network of miRNAs in cardiomyocyte differentiation. Two large, independent networks were assembled—1 pluripotent and 1 differentiated. Shown are the top 5% of overlaps, with the top 1% shaded red.

To gain a higher level insight into the interplay between families of miRNAs during differentiation, the network of shared mRNA targets between individual miRNAs was investigated. A target overlap score was assigned for the significance of each set of predicted mRNA targets shared between 2 individual miRNAs (–log10 of the FDR of the significance of overlap), which allowed the most statistically significant overlaps to be visualized as a network. The top 5% of target overlaps were mapped as a network (Fig. 4B and Supplementary Fig. S3), with the top 1% labeled in red. The relative distance between miRNAs is also related to their target overlap, with the most highly related miRNAs based on shared targets being closest in proximity. The 2 most prominent networks with a large degree of overlap were pluripotency related (Supplementary Fig. S3), whose miRNAs are downregulated during the differentiation time course, and differentiation related (Fig. 4B), whose miRNAs are upregulated during the differentiation. The most highly interconnected modules in both groups represented known miRNA families based on seed sequence [48]: the miR-302 family in the pluripotency network and the let-7 family in the cardiomyocyte network. Further highly interconnected subnetwork nodes that represent other families were also observed: miR-200bc (miR-200b/c and miR-429), miR-200a (miR-200a and miR-141), miR-15 (miR-195 and miR-497), and miR-181 (miR-181a/b/c). In addition to the most highly interconnected families, families and individual miRNAs with unrelated seed sequences were also connected, suggesting these miRNAs work in concert to regulate mRNAs during the cardiomyocyte differentiation. In the differentiation network, the heart development–specific miRNA families share nonoverlapping targets (Fig. 4B). For instance, miR-1 shares targets with miR-133a/b, yet miR-1 has no significant degree of overlap with miR-208a/b. Additionally, miR-1 and miR-181a/b/c both overlap with the let-7 family. On the other hand, miR-208a/b shares no significant overlaps with other heart-development miRNAs, and only overlaps with the miR-181a/b/c family. Examination of the temporal regulation of these miRNAs shows that the heart-development miRNAs are rapidly activated at days 7–10 (Fig. 3C), while the let-7 miRNAs are not expressed until later in the differentiation time course (Supplementary Fig. S3). These findings suggest that there are overlapping and distinct targets for different sets of miRNAs important in the differentiation of cardiomyocytes.

Discussion

In vitro assays present superb access to the chosen experimental system. Often times these systems are limited to single proteins, pathways, or portions thereof. The data presented here demonstrate that complex developmental processes can also be accessed and interrogated through in vitro models, namely differentiation of hiPSCs. Whole-genome mRNA transcript profiling and unsupervised hierarchical clustering over the differentiation and long-term maintenance of hiPSC-derived cardiomyocytes showed (1) a single major bifurcation of the mRNA and miRNA expression profiles occurring between culture days 14 and 20, (2) stable expression of cardiac-specific mRNAs and miRNAs following commitment, and (3) a high degree of correlation with the expression profile obtained from several human heart samples with a maturation of the hiPSC-derived cardiomyocytes over extended culture (Figs. 1 and 2). The primary bifurcation occurs during the antibiotic-based cardiomyocyte enrichment window, and the lack of significant branch points postenrichment demonstrates the attainment of stable expression profiles. The high correlation with the expression profiles of fetal and adult native heart samples is less than unity; however, this is not surprising as the heart is comprised of multiple cell types and these noncardiomyocytes within the native tissue may account for much of the discrepancy when compared with pure cardiomyocytes derived from hiPSCs. The important demonstration here is that the hiPSC-derived cardiomyocytes provide a long-term, stable in vitro experimental platform that is amenable to high-resolution interrogation.

Determining the role of individual miRNAs in development is challenging due to their functional overlap. For example, deletions of each miRNA gene individually in Caenorhabditis elegans results in few, if any, phenotypic consequences [49]. Yet miRNAs clearly play an important role in development since the deletion of the miRNA-processing machinery leads to early embryonic lethality in many higher species [5,6]. The data presented here provide the means for identifying miRNAs involved in cardiac development. Analysis of a comprehensive mRNA and miRNA expression time course enabled the assembly of pluripotency (Supplementary Fig. S4) and cardiomyocyte differentiation (Fig. 4B) miRNA networks. This method of network assembly also provided a quantitative measure of interrelatedness between nodes. Importantly, the most highly interrelated miRNAs identified by this unsupervised method were a part of previously identified families, such as the let-7 and miR-302 families as well as nodes of miRNAs previously associated with heart development.

Much of the functional redundancy of miRNAs is thought to be mediated by seed sequence homology between members of an miRNA family. Furthermore, although multiple distinct miRNA binding sites have been observed in the 3′-UTRs of single mRNAs, the functional significance of these observations remains unclear. Our data suggest that binding to individual mRNAs by miRNAs from unrelated families may provide an additional layer of regulation during the differentiation of cardiomyocytes. There are many interesting possibilities for why unrelated miRNAs may share targets. Perhaps the 2 (or more) miRNAs act synergistically to more drastically silence the mRNA and protein [50]. Or, there may be an important temporal component, where 1 miRNA is expressed first, followed by the expression of a second later in development. For example, we observed that miR-1, expressed early during the cardiomyocyte commitment phase of the differentiation, shared mRNA targets with the let-7 family of miRNAs, which are expressed only later during the differentiation time course, suggesting the 2 miRNA families cooperate temporally to regulate shared targets. Importantly, construction of this network was only possible because of the availability of high-resolution expression from both mRNA and miRNA during cardiomyocyte differentiation. This analysis revealed all of the known heart development miRNAs, suggesting that performing such an analysis on other tissues where the developmentally important miRNAs are unknown could yield novel developmental miRNAs.

The data presented herein demonstrate that in vitro differentiation recapitulates the major developmental milestones and will serve as a baseline for future work examining the role of miRNAs in heart disease. Future comparative analysis of these data with profiles generated from iPS cells from individuals with heritable heart disease could help uncover any disease-specific miRNA changes. Additionally, perturbing the normal miRNA content, by either overexpression of synthetic miRNA mimics or knockdown with antagomirs, could yield additional insight into the role miRNA plays in disease pathogenesis. Finally, by modulating miRNA expression during iPSC differentiation, one may be able to examine the positive and negative impacts miRNAs have during the genetic regulation of cardiogenesis. Therefore, this system is a powerful platform for studying the role of miRNAs in human cardiac development and disease.

Supplementary Material

Author Disclosure Statement

J.E.B., M.R., S.S., P.R., H.B., T.W., E.C., U.C., and K.L.K. are employees of Hoffman-La Roche. B.S. is an employee of Cellular Dynamics International.

References

- 1.Dvash T. Benvenisty N. Human embryonic stem cells as a model for early human development. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2004;18:929–940. doi: 10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2004.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stadtfeld M. Hochedlinger K. Induced pluripotency: history, mechanisms, and applications. Genes Dev. 24:2239–2263. doi: 10.1101/gad.1963910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pouton CW. Haynes JM. Embryonic stem cells as a source of models for drug discovery. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2007;6:605–616. doi: 10.1038/nrd2194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Babiarz JE. Blelloch R. StemBook. The Stem Cell Research Community; 2009. Small RNAs–their biogenesis, regulation and function in embryonic stem cells. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bernstein E. Kim SY. Carmell MA. Murchison EP. Alcorn H. Li MZ. Mills AA. Elledge SJ. Anderson KV. Hannon GJ. Dicer is essential for mouse development. Nat Genet. 2003;35:215–217. doi: 10.1038/ng1253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wang Y. Medvid R. Melton C. Jaenisch R. Blelloch R. DGCR8 is essential for microRNA biogenesis and silencing of embryonic stem cell self-renewal. Nat Genet. 2007;39:380–385. doi: 10.1038/ng1969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bartel DP. MicroRNAs: target recognition and regulatory functions. Cell. 2009;136:215–233. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cordes KR. Srivastava D. MicroRNA regulation of cardiovascular development. Circ Res. 2009;104:724–732. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.108.192872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kartha RV. Subramanian S. MicroRNAs in cardiovascular diseases: biology and potential clinical applications. J Cardiovasc Transl Res. 2010;3:256–270. doi: 10.1007/s12265-010-9172-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhao Y. Ransom JF. Li A. Vedantham V. von Drehle M. Muth AN. Tsuchihashi T. McManus MT. Schwartz RJ. Srivastava D. Dysregulation of cardiogenesis, cardiac conduction, and cell cycle in mice lacking miRNA-1-2. Cell. 2007;129:303–317. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.03.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhang J. Wilson GF. Soerens AG. Koonce CH. Yu J. Palecek SP. Thomson JA. Kamp TJ. Functional cardiomyocytes derived from human induced pluripotent stem cells. Circ Res. 2009;104:e30–e41. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.108.192237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bu L. Jiang X. Martin-Puig S. Caron L. Zhu S. Shao Y. Roberts DJ. Huang PL. Domian IJ. Chien KR. Human ISL1 heart progenitors generate diverse multipotent cardiovascular cell lineages. Nature. 2009;460:113–117. doi: 10.1038/nature08191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yang L. Soonpaa MH. Adler ED. Roepke TK. Kattman SJ. Kennedy M. Henckaerts E. Bonham K. Abbott GW, et al. Human cardiovascular progenitor cells develop from a KDR+ embryonic-stem-cell-derived population. Nature. 2008;453:524–528. doi: 10.1038/nature06894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Braam SR. Tertoolen L. van de Stolpe A. Meyer T. Passier R. Mummery CL. Prediction of drug-induced cardiotoxicity using human embryonic stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes. Stem Cell Res. 2010;4:107–116. doi: 10.1016/j.scr.2009.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hattori F. Chen H. Yamashita H. Tohyama S. Satoh YS. Yuasa S. Li W. Yamakawa H. Tanaka T, et al. Nongenetic method for purifying stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes. Nat Methods. 2010;7:61–66. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Xu XQ. Soo SY. Sun W. Zweigerdt R. Global expression profile of highly enriched cardiomyocytes derived from human embryonic stem cells. Stem Cells. 2009;27:2163–2174. doi: 10.1002/stem.166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Braam SR. Passier R. Mummery CL. Cardiomyocytes from human pluripotent stem cells in regenerative medicine and drug discovery. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2009;30:536–545. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2009.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ma J. Guo L. Fiene SJ. Anson BD. Thomson JA. Kamp TJ. Kolaja KL. Swanson BJ. January CT. High purity human induced pluripotent stem cell (hiPSC) derived cardiomyocytes: electrophysiological properties of action potentials and ionic currents. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2011;301:H2006–2017. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00694.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yu J. Vodyanik MA. Smuga-Otto K. Antosiewicz-Bourget J. Frane JL. Tian S. Nie J. Jonsdottir GA. Ruotti V, et al. Induced pluripotent stem cell lines derived from human somatic cells. Science. 2007;318:1917–1920. doi: 10.1126/science.1151526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Klug MG. Soonpaa MH. Koh GY. Field LJ. Genetically selected cardiomyocytes from differentiating embronic stem cells form stable intracardiac grafts. J Clin Invest. 1996;98:216–224. doi: 10.1172/JCI118769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Donnelly ML. Luke G. Mehrotra A. Li X. Hughes LE. Gani D. Ryan MD. Analysis of the aphthovirus 2A/2B polyprotein 'cleavage' mechanism indicates not a proteolytic reaction, but a novel translational effect: a putative ribosomal 'skip'. J Gen Virol. 2001;82:1013–1025. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-82-5-1013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pfaffl MW. A new mathematical model for relative quantification in real-time RT-PCR. Nucleic Acids Res. 2001;29:e45. doi: 10.1093/nar/29.9.e45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tai YC. Speed TP. On gene ranking using replicated microarray time course data. Biometrics. 2009;65:40–51. doi: 10.1111/j.1541-0420.2008.01057.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lu Y. Liu PY. Xiao P. Deng HW. Hotelling's T2 multivariate profiling for detecting differential expression in microarrays. Bioinformatics. 2005;21:3105–3113. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Su AI. Wiltshire T. Batalov S. Lapp H. Ching KA. Block D. Zhang J. Soden R. Hayakawa M, et al. A gene atlas of the mouse and human protein-encoding transcriptomes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:6062–6067. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0400782101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chang JT. Nevins JR. GATHER: a systems approach to interpreting genomic signatures. Bioinformatics. 2006;22:2926–2933. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btl483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Reich M. Liefeld T. Gould J. Lerner J. Tamayo P. Mesirov JP. GenePattern 2.0. Nat Genet. 2006;38:500–501. doi: 10.1038/ng0506-500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Friedman RC. Farh KK. Burge CB. Bartel DP. Most mammalian mRNAs are conserved targets of microRNAs. Genome Res. 2009;19:92–105. doi: 10.1101/gr.082701.108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bader GD. Hogue CW. An automated method for finding molecular complexes in large protein interaction networks. BMC Bioinformatics. 2003;4:2. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-4-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kim J. Chu J. Shen X. Wang J. Orkin SH. An extended transcriptional network for pluripotency of embryonic stem cells. Cell. 2008;132:1049–1061. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.02.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Peng JC. Valouev A. Swigut T. Zhang J. Zhao Y. Sidow A. Wysocka J. Jarid2/Jumonji coordinates control of PRC2 enzymatic activity and target gene occupancy in pluripotent cells. Cell. 2009;139:1290–1302. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Stennard F. Ryan K. Gurdon JB. Markers of vertebrate mesoderm induction. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 1997;7:620–627. doi: 10.1016/s0959-437x(97)80009-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tada S. Era T. Furusawa C. Sakurai H. Nishikawa S. Kinoshita M. Nakao K. Chiba T. Characterization of mesendoderm: a diverging point of the definitive endoderm and mesoderm in embryonic stem cell differentiation culture. Development. 2005;132:4363–4374. doi: 10.1242/dev.02005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cao F. Wagner RA. Wilson KD. Xie X. Fu JD. Drukker M. Lee A. Li RA. Gambhir SS, et al. Transcriptional and functional profiling of human embryonic stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes. PLoS One. 2008;3:e3474. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0003474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Liu J. Lieu DK. Siu CW. Fu JD. Tse HF. Li RA. Facilitated maturation of Ca2+ handling properties of human embryonic stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes by calsequestrin expression. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2009;297:C152–C159. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00060.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Goldfarb LG. Dalakas MC. Tragedy in a heartbeat: malfunctioning desmin causes skeletal and cardiac muscle disease. J Clin Invest. 2009;119:1806–1813. doi: 10.1172/JCI38027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Duprey P. Paulin D. What can be learned from intermediate filament gene regulation in the mouse embryo. Int J Dev Biol. 1995;39:443–457. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bachman NJ. Riggs PK. Siddiqui N. Makris GJ. Womack JE. Lomax MI. Structure of the human gene (COX6A2) for the heart/muscle isoform of cytochrome c oxidase subunit VIa and its chromosomal location in humans, mice, and cattle. Genomics. 1997;42:146–151. doi: 10.1006/geno.1997.4687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Laurent LC. Chen J. Ulitsky I. Mueller FJ. Lu C. Shamir R. Fan JB. Loring JF. Comprehensive microRNA profiling reveals a unique human embryonic stem cell signature dominated by a single seed sequence. Stem Cells. 2008;26:1506–1516. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2007-1081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Suh MR. Lee Y. Kim JY. Kim SK. Moon SH. Lee JY. Cha KY. Chung HM. Yoon HS, et al. Human embryonic stem cells express a unique set of microRNAs. Dev Biol. 2004;270:488–498. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2004.02.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bar M. Wyman SK. Fritz BR. Qi J. Garg KS. Parkin RK. Kroh EM. Bendoraite A. Mitchell PS, et al. MicroRNA discovery and profiling in human embryonic stem cells by deep sequencing of small RNA libraries. Stem Cells. 2008;26:2496–2505. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2008-0356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Morin RD. O'Connor MD. Griffith M. Kuchenbauer F. Delaney A. Prabhu AL. Zhao Y. McDonald H. Zeng T et al. Application of massively parallel sequencing to microRNA profiling and discovery in human embryonic stem cells. Genome Res. 2008;18:610–621. doi: 10.1101/gr.7179508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Melton C. Blelloch R. MicroRNA Regulation of Embryonic Stem Cell Self-Renewal and Differentiation. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2010;695:105–117. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4419-7037-4_8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.van Rooij E. Sutherland LB. Liu N. Williams AH. McAnally J. Gerard RD. Richardson JA. Olson EN. A signature pattern of stress-responsive microRNAs that can evoke cardiac hypertrophy and heart failure. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:18255–18260. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0608791103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Adachi T. Nakanishi M. Otsuka Y. Nishimura K. Hirokawa G. Goto Y. Nonogi H. Iwai N. Plasma microRNA 499 as a biomarker of acute myocardial infarction. Clin Chem. 56:1183–1185. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2010.144121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wang GK. Zhu JQ. Zhang JT. Li Q. Li Y. He J. Qin YW. Jing Q. Circulating microRNA: a novel potential biomarker for early diagnosis of acute myocardial infarction in humans. Eur Heart J. 31:659–666. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehq013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Guo H. Ingolia NT. Weissman JS. Bartel DP. Mammalian microRNAs predominantly act to decrease target mRNA levels. Nature. 466:835–840. doi: 10.1038/nature09267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Griffiths-Jones S. Bateman A. Marshall M. Khanna A. Eddy SR. Rfam: an RNA family database. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31:439–441. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Miska EA. Alvarez-Saavedra E. Abbott AL. Lau NC. Hellman AB. McGonagle SM. Bartel DP. Ambros VR. Horvitz HR. Most Caenorhabditis elegans microRNAs are individually not essential for development or viability. PLoS Genet. 2007;3:e215. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.0030215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Doench JG. Petersen CP. Sharp PA. siRNAs can function as miRNAs. Genes Dev. 2003;17:438–442. doi: 10.1101/gad.1064703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.