Abstract

A fundamental goal of double-blind alcohol challenge studies is to reduce alcohol expectancies, though there is little research on the effectiveness of blinding procedures and their relationship to acute alcohol responses. This study examined social drinkers’ perception of beverage content and related alcohol response during three separate double-blind experimental sessions with placebo, low dose alcohol (0.4 g/kg), and high dose alcohol (0.8 g/kg). Using the Alternative Substance Paradigm, participants (N=182) were informed that the beverage they consumed might contain alcohol, a stimulant, a sedative, or a placebo. At several timepoints, subjective and objective measures were obtained and participants were asked to identify which substance they received. During both placebo and low dose alcohol sessions, 33% and 50% of participants, respectively, did not correctly identify the beverage content; during the high dose alcohol session, 20% did not correctly identify the beverage. While correct and incorrect identifiers at any dose level did not differ on major background variables, drinking characteristics, or psychomotor performance during these sessions, they did differ on self-reported subjective responses, with greater sedation reported by incorrect identifiers in the placebo and high dose conditions. In sum, results suggest that the Alternative Substance Paradigm may be a viable option for alcohol laboratory studies, particularly for repeated sessions in within-subjects designs and in cases where the experimenter wants to reduce expectancy by not revealing a priori that alcohol is being administered.

Keywords: alcohol, social drinker, blinding procedures, alcohol expectancy, balanced-placebo design, alternative substance paradigm

INTRODUCTION

Oral alcohol challenge studies have provided important information about dose- and time-dependent subjective and performance effects of alcohol as well as variability and individual differences in this acute alcohol response (see Morean & Corbin, 2010 for review). They have also helped illustrate the relationship between alcohol response and future alcohol problems in participants with variable drinking patterns and family history (King, de Wit, McNamara, & Cao, 2011; Schuckit & Smith, 1996). Unfortunately, if participants are aware they are consuming alcohol, measurement of true alcohol response in the laboratory may be confounded with their expectations or expectancies (Jones, Corbin, & Fromme, 2001). Depending on the aims of the specific project, activation of these expectancies could question the validity of overall study results.

The balanced-placebo design (BPD; Carpenter, 1967; 1968, McKay & Schare, 1999) was developed several decades ago to address this issue by including four experimental groups that cross expectancy (i.e., being told that a beverage contains alcohol or placebo) with beverage content (i.e., alcohol or placebo). Research with the BPD and its modifications has shown that instructional set plays a vital role in alcohol response: participants who are told that they have consumed alcohol report greater subjective intoxication (i.e., feeling drunk), have slower reaction times (Finnigan, Hammersley, & Millar, 1995), and engage in more risky simulated driving behaviors (Burian, Hensberry, & Liguori, 2003) than those informed they did not consume alcohol, regardless of actual beverage content. Further, while there are variations in specific blinding procedures and manipulation checks across studies, research generally indicates that, even after consuming a placebo drink, participants often report a moderate degree of subjective intoxication (Corbin et al., 2008; Cronce & Corbin, 2010; Greenstein et al., 2010) and estimate that some alcohol was in the beverage they consumed (Corbin et al., 2008). Various studies have shown, however, that successful blinding decreases as alcohol dose increases: 44% of participants in one study guessed they had consumed some alcohol after receiving a moderate dose versus 90% in another study after an intoxicating dose of alcohol (Martin & Sayette, 1993). Despite this knowledge, previous studies have not elucidated the relationship between successful participant blinding and acute responses to alcohol and placebo as measured in the laboratory. Also lacking are comparisons of background and/or drinking characteristics of participants who correctly identify a consumed beverage versus those who do not.

To minimize expectancy and refrain from disclosing that a beverage contains alcohol, several studies have instead informed participants that they may receive one of many active substances, such as a stimulant, sedative, or alcohol, a placebo, or some combination of these (Acheson, Mahler, Chi, & de Wit, 2006; Chi & de Wit, 2003; de Wit, Crean, & Richards, 2000; King, Houle, de Wit, Holdstock, & Schuster, 2002; King, McNamara, Angstadt, & Phan, 2010; King, McNamara, Conrad, & Cao, 2009; Mintzer & Griffiths, 2001). The advantages of this paradigm, which we now coin “The Alternative Substance Paradigm” (ASP), include less recruitment bias, as advertisements do not specify the research as an alcohol study; not being limited to between-subjects and/or four cell designs; and leaving out the ethical dilemma of informing participants that they are not receiving alcohol when they actually are, i.e., the antiplacebo cell of the BPD. While the ASP has been used in several studies, to our knowledge, there have been no published reports examining its effectiveness in blinding participants to beverage content and reducing expectancy effects. Further, it is unclear whether identification of beverage content would vary by dose level as shown in BPD designs that assess amount of alcohol received or if experienced drinkers would have greater accuracy when identifying beverages than novice or lighter drinkers. These points are particularly important, given the implications of inadequate blinding for the validity of results in acute alcohol response research.

The goal of the current study, therefore, was to determine the effectiveness of beverage blinding in the aforementioned ASP. A secondary aim was to examine the effects of blinding on subjective and objective alcohol responses. To our knowledge, this is the first study to assess such factors in a design that does not explicitly reveal that alcohol will be administered. We hypothesized that: a) at a high oral alcohol dose (0.8g/kg) [vs. low dose (0.4 g/kg)], participants would be better able to identify alcohol as the study beverage due to stronger alcohol effects and taste cues; b) heavy social drinkers (vs. light drinkers) would be more accurate in identifying beverage content due to greater exposure to alcohol; and c) participants who incorrectly identified beverage content (vs. those who correctly identified the beverage) would show differential subjective and performance responses. Exploratory analyses also examined beverage identification early in the session (30 minutes after beverage consumption) versus the end of the session (180 minutes), sex effects, and acute alcohol response among subgroups of incorrect identifiers.

METHOD

Participants

Participants were enrolled in the larger, ongoing Chicago Social Drinking Project (CSDP), which examines subjective, objective, and physiological responses to alcohol in social drinkers (for a detailed report of these findings for the entire sample, see King et al., 2011). The current study included 182 of the 190 (96%) participants in the first wave cohort of CSDP. The first eight participants in CSDP were not asked to estimate beverage content and therefore were not eligible for the current study. Participants were aged 21-35 years, had a body mass index (BMI) between 19-30 kg/m2, and were in good general health. As part of CSDP, participants were recruited for one of two drinking groups based on alcohol consumption patterns over the past two (or more) years: heavy drinkers were those individuals who “binged” (i.e., consumed five or more drinks on one occasion for men/four or more for women) at least once weekly and light drinkers had rare or no binge drinking episodes. These criteria capture the SAMSHA criteria for “heavy drinking” (SAMSHA, 2005) and are consistent with epidemiological data (Dawson et al., 2008) and heavy social drinking samples examined in recent alcohol challenge studies (King & Epstein, 2005; King et al., 2002; McKee, Harrison, & Shi, 2010; Ray & Hutchison, 2007; Ray et al., 2007). To ensure that light drinkers were regular consumers of alcohol and would not be adversely affected by an alcohol challenge, they needed to consume at least one drink per week. In addition, they were allowed a maximum of six drinks per week to avoid any overlap with the heavy drinking group, who consumed a minimum of 10 drinks weekly. For heavy drinkers, an upper limit of five binge episodes per week and an average weekly total of 40 drinks per week was employed to screen out extreme drinkers or alcoholics who may exhibit confounds of withdrawal symptoms or who would be otherwise unable to comply with abstinence requirements prior to the laboratory sessions.

Procedure

Recruitment

Participants were recruited via local media, the Internet, and through flyers advertising a study that examined the effects of common substances, i.e., stimulants (like caffeine), sedatives (like an antihistamine), alcohol, or a non-active substance (placebo) on mood and behavior among a range of social drinkers. This ASP description was reiterated to candidates during the screening visit and at all experimental sessions. At in-person screening, candidates signed the informed consent form; underwent a brief physical examination with blood and urine test for hepatic liver function, complete blood count, and toxicology; participated in a diagnostic interview; and completed several psychosocial and health history questionnaires. Candidates were excluded from participation if they were taking any psychotropic medications, had a major medical or psychiatric condition (including past or current alcohol or substance dependence, excluding nicotine), or had a positive urine screen (morphine, cocaine, methamphetamine, barbiturates, or benzodiazepines). Women were also excluded if they were pregnant or breastfeeding.

Laboratory sessions

All study procedures were reviewed and approved by the University of Chicago Institutional Review Board. Participants completed three, five-hour afternoon or evening laboratory sessions, each starting between 3:00-5:00 pm and separated by at least 48 hours. Prior to each session, participants were instructed to abstain from drugs and alcohol for 48 hours, and food, caffeine, and smoking for three hours. Abstinence was verified upon arrival through self-report of last alcohol and substance use, breath tests for carbon monoxide (Smokerlyzer®, Bedfont Scientific, Medford NJ) and alcohol (Alco-Sensor III, Intoximeter, St. Louis, MO, USA), and a urine toxicology test randomly administered before one of the three sessions. Additionally, female participants underwent a pregnancy test prior to each session. Following these compliance measures, participants consumed a small snack (20% of daily calories based on body weight) to help reduce the potential for alcohol-induced nausea and avoid hunger effects on mood state.

Participants then completed baseline subjective and objective measures and consumed their study beverage. At various intervals after beverage consumption, participants repeated study measures and breathalyzer tests (Alco-Sensor IV, Intoximeter; St. Louis, MO, USA). The breathalyzer, identified as a more general “breath test” to further decrease alcohol expectancy, was placed on a blinded setting so subsequent breathalyzer results displayed readings of 0.00 g/210 L, with actual readings downloaded later to a computer by a second research assistant. Between timepoints, participants could watch television or movies or read in the comfortable, living room-like laboratory testing rooms. At the end of each five-hour session, when breathalyzer readings were 0.04 g/210 L or lower, participants were transported home by a car service to ensure safety. After the last session, participants were compensated with a check for $200 and received a debriefing form in a sealed envelope that they discussed with a research assistant. The debriefing form used a grid that contained check boxes for stimulant, sedative, alcohol, placebo, or a combination of these, and the appropriate box and dose was checked for each session.

Alcohol Administration

Participants received a placebo beverage (0.0 g/kg; 1% volume of ethanol as taste mask), a low dose alcohol beverage (0.4 g/kg; 8% volume alcohol), and a high dose alcohol beverage (0.8 g/kg; 16% volume alcohol) in counterbalanced order. All study drinks included 190-proof ethanol, water, flavored drink mix, and sucralose-based sugar substitute and were prepared prior to each session by a separate, unblinded staff member. The participant's total drink volume was consistent across all study sessions and based on individual body weight, with an average volume of 471 mL (range: 327-668 mL). Incidentally, there were no significant differences in body weight between correct and incorrect identifiers (defined below), so drink volumes were comparable across all groups. Women received 85% of the dose of men to account for sex differences in total body water (Frezza et al., 1990; Sutker, Tabakoff, Goist, & Randall, 1983). The total beverage volume was divided into two equal portions and served in clear plastic, lidded cups with straws. As presented during the consent and screening procedures, participants were reminded that the beverage might contain a stimulant (like caffeine), sedative (like an antihistamine), alcohol, placebo, or a combination of these substances. All participants consumed the beverage over fifteen minutes (five minutes for each portion separated by a five-minute rest interval) in the presence of the research assistant (Brumback, Cao, & King, 2007; King et al., 2011; King, Munisamy, de Wit, & Lin, 2006).

Subjective Measures

At 30 and 180 minutes after initiation of beverage consumption, participants completed the Biphasic Alcohol Effects Scale (BAES; Martin, Earleywine, Musty, Perrine, & Swift, 1993), which yields two reliable and valid subscales (i.e., stimulation and sedation) and can be validly administered without disclosing that participants consumed alcohol (Rueger, McNamara, & King, 2009). Participants were then asked to estimate the content of the beverage (i.e., “Which substance do you think you received?”) with response choices “sedative, stimulant, alcohol, or placebo (no substance)” presented left to right on the computer screen. Participants were classified as either correct or incorrect identifiers at each session timepoint. Correct identifiers accurately identified the beverage content (i.e., chose “placebo (no substance)” during the placebo session or “alcohol” during the low and high dose alcohol sessions). Incorrect identifiers identified the beverage as an active substance during the placebo session, or chose “stimulant,” “sedative,” or “placebo (no substance)” during the alcohol sessions. After the primary substance identification, participants were asked whether they thought they had received a second substance and, if so, which substance they had received. The base rates of guessing a secondary substance were relatively low (9%, 17%, and 13% of participants during placebo, low dose alcohol, and high dose alcohol sessions, respectively). An even smaller subset (4%, 9%, and 6% of participants during placebo, low dose alcohol, and high dose alcohol sessions, respectively) was incorrect with their primary substance guess but correct on beverage identification with their secondary substance guess. Repeating the main analyses with correct beverage identification based on either first or second guess did not change the overall pattern of results, so to maintain clarity of presentation, the paper focuses on primary beverage identification.

Objective Measures

Performance measures were obtained before and at several intervals after beverage consumption to capture objective impairment. These included the Digit Symbol Substitution Task (DSST; Wechsler, 1981), a measure of perceptual-motor processing, and the Grooved Pegboard (Lafayette Instruments, Lafayette, IN, USA), a test of motor speed and fine motor coordination. Both tasks have proven sensitive to the acute intoxicating effects of alcohol (Brumback et al., 2007; Doty, Kirk, Cramblett, & de Wit, 1997; Holdstock & de Wit, 2001; Ramchandani, Flury, et al., 2002; Ramchandani, O'Connor, et al., 1999).

Statistical Analyses

After establishing which participants were able to correctly identify beverage content at each session, baseline and substance use characteristics for correct and incorrect identifiers, as well as heavy and light drinkers, were compared using Student's t-tests and Chi-square tests, as appropriate. To address our first hypothesis, Wilcoxon signed-rank tests were used to compare the proportions of incorrect identifiers at each dose, allowing for any overlap created by the within-subjects design. To address the second study question, a Chi-square test was used to compare correct and incorrect identification as a function of drinking group (i.e., heavy vs. light drinkers). Time (i.e., 30 vs. 180 minutes) and gender effects were also considered, on an exploratory basis, using separate Chi-square tests. Finally, (drinking group: heavy vs. light) × 2 (identifier group: correct vs. incorrect) analyses of variance (ANOVAs) were conducted on subjective (BAES) and performance (DSST, Pegboard) measures using change scores from baseline response to the peak post-beverage increase. Given the heterogeneity inherent in incorrect identification (i.e., any one of three different substances), one-way ANOVAs were conducted to further examine the effects of beverage estimation, followed by Tukey's post-hoc tests, as appropriate.

RESULTS

Overall, participants were 25.6 M ± 3.3 SD years old, with a majority of Caucasian race (72.0%) and a balanced sex ratio (55% male). With regard to drinking group, heavy drinkers were less educated, had greater drinking days per month, and consumed more drinks per drinking day than light drinkers (see Table 1). Correct and incorrect identifiers at all doses and timepoints did not differ on age, sex, race, or education or prior exposure to alcohol, stimulants, or sedatives (see Table 2). Average breath alcohol concentrations during the sessions confirmed 0.00 g/210 L of breath at all timepoints for the placebo session, and revealed the expected breath alcohol levels at 30, 60, 120 and 180 minutes [low dose (in g/210 L breath): 0.04 M ± 0.01 SD, 0.04 ± 0.01, 0.02 ± 0.01, 0.01 ± 0.01; high dose (in g/210 L breath): 0.08 ± 0.02, 0.09 ± 0,02, 0.07 ± 0.01, 0.05 ± 0.01)].

Table 1.

Background Characteristics and Substance Use for Light and Heavy Drinkers

| Light Drinkersa (n = 82) | Heavy Drinkersb (n = 100) | |

|---|---|---|

| General Characteristics | ||

| Age (years) | 26.0 (3.4) | 25.2 (3.0) |

| Education (years) | 16.6 (2.0) | 15.7 (1.4)*** |

| Gender (% male) | 41 (50.0%) | 59 (59.0%) |

| Race (% Caucasian) | 54 (65.9%) | 78 (78.0%) |

| Drinking Behavior | ||

| Frequency (drinking days/month) | 6.4 (3.2) | 14.4 (5.3)*** |

| Quantity (average # of drinks/drinking day) | 1.7 (0.5) | 5.2 (1.9)*** |

| Substance Use | ||

| Lifetime marijuana use (ever used) | 38 (46.4%) | 91 (91.0%)*** |

| Lifetime caffeine use (ever used) | 78 (95.1%) | 96 (96.0%) |

| Lifetime tranquilizer use (ever used) | 3 (3.7%) | 24 (24.0%) |

Note: Data are n (%) or mean (SD) as appropriate.

Light social drinkers are defined as those who drink five or less standard alcoholic drinks per week with rare or no binge drinking.

Heavy social drinkers are defined as those who binge at least five times per month (i.e., consume 5+ drinks for men, 4+ for women on one occasion).

p < 0.001

Table 2.

Background Characteristics and Substance Use for Correct and Incorrect Identifiers

| Placebo Session | Low Alcohol Session | High Alcohol Session | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Correct Identifiers (n=112) |

Incorrect Identifiers (n=70) |

Correct Identifiers (n=82) |

Incorrect Identifiers (n=100) |

Correct Identifiers (n=146) |

Incorrect Identifiers (n=36) |

|

| General Characteristics | ||||||

| Age (years) | 25.4 (3.2) | 25.9 (3.4) | 25.1 (3.4) | 26.0 (3.1) | 25.5 (3.2) | 25.9 (3.4) |

| Education (years) | 16.3 (1.6) | 15.8 (2.0) | 16.0 (1.3) | 16.2 (2.1) | 16.2 (1.8) | 15.7 (1.8) |

| Gender (% male) | 51 (45.5%) | 31 (44.3%) | 33 (40.2%) | 49 (49.0%) | 67 (45.9%) | 15 (41.7%) |

| Race (% Caucasian) | 84 (75.0%) | 48 (68.6%) | 57 (69.5%) | 75 (75.0%) | 111 (76.0%) | 21 (58.3%) |

| Drinking Behavior | ||||||

| % Heavy social drinkera | 38 (54.3%) | 38 (54.3%) | 44 (53.7%) | 56 (56.0%) | 82 (56.2%) | 18 (50.0%) |

| Frequency (drinking days/month) | 10.9 (5.8) | 10.6 (6.3) | 10.6 (6.0) | 10.9 (6.0) | 11.1 (6.1) | 9.4 (5.3) |

| Quantity (average # of drinks/drinking day) | 3.6 (2.3) | 3.7 (2.2) | 3.6 (2.2) | 3.6 (2.4) | 3.6 (2.3) | 3.5 (2.2) |

| Substance Use | ||||||

| Lifetime marijuana use (ever used) | 82 (73.2%) | 47 (67.1%) | 61 (74.4%) | 68 (68.0%) | 97 (66.4%) | 32 (88.9%) |

| Lifetime caffeine use (ever used) | 108 (96.4%) | 66 (94.3%) | 79 (96.3%) | 95 (95.0%) | 138 (94.5%) | 36 (100%) |

| Lifetime tranquilizer use (ever used) | 15 (13.4%) | 12 (17.1%) | 11 (13.4%) | 16 (16.0%) | 23 (15.8%) | 4 (11.1%) |

Note: Data are n (%) or mean (SD) as appropriate. Data represent correct and incorrect identifiers at each session at the +180 minute timepoint. There were no differences between correct and incorrect identifiers on these characteristics or behaviors at any session.

Heavy social drinkers are defined as those who “binge” at least five times per month (i.e., consume 5+ drinks for men, 4+ for women on one occasion).

As shown in Table 3, beverage identification did not differ at 30 minutes compared to 180 minutes post-consumption [Χ2 (1, N =182)≤0.35, ps=ns]. Therefore, participants were grouped using their ratings at the end of each session (180 minutes) to parallel the timepoint most often reported in validity checks. Participants were most likely to incorrectly identify beverage content during the low dose alcohol session (55% incorrect), followed by the placebo session [38% incorrect; z(182)=-3.71, p<0.001], and finally, the high dose alcohol session [20% incorrect; z(182)=-3.16, p<0.01]. There were no differences in beverage identification as a function of drinking group, with similar rates of incorrect identification in heavy versus light drinkers, i.e., 38% vs. 37% at placebo, 56% vs. 54% at low dose alcohol, and 18% vs. 22% at high dose alcohol, respectively [Χ2 (1, N =182)≤0.75, ps=ns]. Similarly, gender had no effect on beverage identification at any dose level [i.e., men vs. women: Χ2 (1, N=182) ≤ 0.24, ps=ns].

Table 3.

Beverage Identification by Session at +30 and +180 Minutes after Beverage Ingestion

| +30 minutes | +180 minutes | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Placebo | Low Dose Alcohol | High Dose Alcohol | Placebo | Low Dose Alcohol | High Dose Alcohol | |

| Correct Identifiers | 59% | 51% | 80% | 62% | 45% | 80% |

| Incorrect Identifiers | 41% | 49% | 20% | 38% | 55% | 20% |

| By category: | ||||||

| Stimulant | 15% | 12% | 6% | 9% | 13% | 6% |

| Sedative | 21% | 28% | 14% | 22% | 31% | 14% |

| Alcohol | 5% | --- | --- | 7% | --- | --- |

| Placebo (No Substance) | --- | 9% | 0% | --- | 11% | 0% |

Note: N=182 subjects

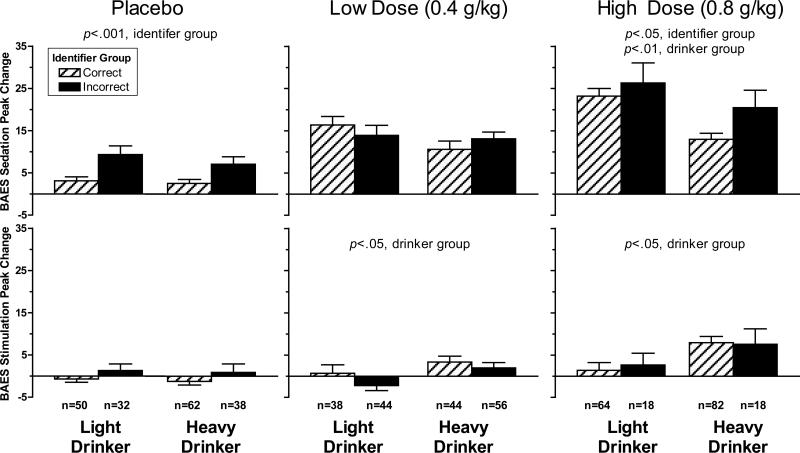

As shown in Figure 1, during the placebo session, those who incorrectly identified the beverage as containing an active substance reported greater BAES sedation than those who correctly identified the placebo beverage [F(1,178)=15.55, p<0.001], but there were no differences between identifier groups on BAES stimulation [F(1,178)=2.60, p=ns]. In the low alcohol dose session, correct and incorrect beverage identifiers did not differ on either BAES sedation or stimulation [Fs(1,178)≤2.15, ps =ns]. Finally, in the high alcohol dose session, as in the placebo session, incorrect identifiers reported greater BAES sedation than correct identifiers [F(1,178)=3.69, p=0.05], but the identifier groups did not differ on BAES stimulation [F(1,178) =0.03, p=ns]. As expected, similar to our prior report (King, et al., 2011), heavy drinkers reported more stimulation than light drinkers at both the low and high dose alcohol sessions [Fs(1,178)≥4.71, ps<0.05] and light drinkers reported more sedation than heavy drinkers at the high dose alcohol session [F(1, 178) = 8.52, p<0.01]. There were no interactions of identifier and drinker group in any of these analyses [F(1,178)≤1.52, ps =ns].

Figure 1.

Peak increase in Sedation and Stimulation from baseline by Dose (placebo, low dose, high dose), Identifier Group (correct,incorrect), and Drinker Group (light drinker, heavy drinker). For placebo, sedation: p<0.001, identifier group (incorrect>correct); low dose, stimulation: p<0.05, drinker group (heavy drinker>light drinker); high dose, sedation: p<0.05, identifier group (incorrect>correct), p<0.01, drinker group (light drinker>heavy drinker); high dose, stimulation: p<0.05, drinker group (heavy drinker>light drinker).

Additional analyses were conducted during the placebo and high dose sessions to examine subjective alcohol response within incorrect identifiers by substance category compared to correct identifiers. Results for the placebo session revealed that those who incorrectly identified the beverage as a “sedative” (n=41) reported greater BAES sedation than those who correctly identified placebo [F(178)=16.18, p<0.001; Tukey's HSD: sedative > no substance, p < 0.001]. For the high dose alcohol session, those who incorrectly identified the beverage as a “stimulant”(n=10) reported greater BAES stimulation [F(178)=6.21, p<0.01; Tukey's HSD: stimulant > alcohol, p = 0.01] and those who incorrectly identified the beverage as a “sedative” (n=26) reported greater BAES sedation compared with those who correctly identified alcohol [F(178) =6.44, p <0.01; Tukey's HSD: sedative>alcohol; p<0.01].

In terms of objective alcohol response, there were no effects between correct and incorrect beverage identification on performance for either the DSST or Pegboard tasks [placebo, Fs(1,178)≤3.10, ps=ns; low dose, Fs(1,178)≤1.64, ps =ns; high dose, Fs(1,178)≤0.57, ps=ns]. For all analyses, there were no significant interactions between drinking and identifier group [F(1,178)≤3.79, ps=ns]. Further, including gender, drinking group, and order of sessions as covariates did not change results.

DISCUSSION

The current study demonstrated that the ASP may be a viable option in human alcohol paradigms that include both alcohol and placebo beverage administration. Overall, successful blinding was strongest during the placebo and low dose alcohol sessions, with 38% and 55% of participants incorrectly identifying beverage content, respectively. Similar to studies using the BPD and its variants, the high dose alcohol condition was less successful for blinding than low dose alcohol or placebo, with 20% of participants inaccurately believing the beverage contained a sedative or stimulant. No specific characteristics emerged to identify participants who were accurate in identifying beverage content at any dose condition and, contrary to our hypothesis, experienced heavy social drinkers were not better able to identify alcohol than light drinkers. While subjective stimulation and performance were similar in all participants at all doses, those incorrectly identifying beverage content during both the placebo and high dose alcohol sessions reported increased sedation, and this was especially true of those participants who identified a “sedative”; those who identified a stimulant at high dose alcohol experienced greater stimulation as well.

Examining the effectiveness of blinding procedures is essential to the validity of oral alcohol challenge paradigms. Historically, relatively few double-blind studies have reported results from systematic manipulation checks (Breslin & Sobell, 1999; Hughes and Krahn, 1985). The studies that have reported such results have often focused on the placebo condition, during which most participants indicate they received at least some alcohol, experienced an increase in subjective intoxication, or both (e.g., Cronce & Corbin, 2010; Corbin et al., 2008; Giancola, 2006; Greenstein et al., 2010). It is difficult to directly compare results from these studies, however, as manipulation checks use different questions to assess blinding. Some suggest that successful blinding should result in participants’ correctly identifying beverage content at a level equal to chance (Hughes & Krahn, 1985), which would require a forced choice between alcohol and no substance when asking participants about beverage content. Others have asked participants how many alcoholic drinks they think they consumed in the beverage. The format of this question implies that participants have received some amount of alcohol, and this may artificially alter blinding rates. In the current study, the ASP offered a range of possible active substances, as opposed to a forced choice between alcohol and placebo, and it is conceivable that this created a different set of expectancies (discussed below). Lower success with beverage blinding at the high alcohol dose (0.8g/kg) has been a longstanding issue in human laboratory studies and was also observed in the present study, i.e., 20% of subjects did not identify the drink was alcohol compared to 55% during the low dose alcohol session. There may be a variety of reasons underlying the lower success with blinding at the high alcohol dose, including the inherent strong sensory and taste cues at this dose level, as well as the pronounced central nervous system effects of an intoxicating dose of alcohol (King et al., 2011).

The present study was the first, to our knowledge, to examine subjective and objective responses to multiple alcohol doses as they relate to blinding. The presence of an acute response to placebo might raise questions about its validity as a condition, as a placebo is defined in the literature as an inert substance that should not have any real effects on subjective or objective measures (Koshi & Short, 2007). However, others conjecture that a placebo condition should produce some drug-like effects, to allow researchers to separate actual alcohol response from the effects of expectancy or response bias (for review, see Morean & Corbin, 2010). In the current study, the substance identified by the incorrect identifiers matched their subjective experience (e.g., those who chose “sedative” were more sedated), which supports the validity of this manipulation. In contrast, performance on digit symbol and pegboard tasks were largely unaffected by successful blinding and did not differ between correct and incorrect identifiers at any dose level. A disconnect between subjective and objective response to alcohol has been demonstrated previously, with heavy drinkers perceiving themselves as less impaired than light drinkers, though actual performance was similarly impaired in both groups (Brumback et al., 2007). Therefore, we may conclude that identification of beverage type was more influenced by participants’ gauge of their subjective mood state than changes in psychomotor functioning. Given these findings, we anticipated that participants in the current study would show differential guessing rates based on drinking history, as heavy and light drinkers have shown differential subjective experiences after consuming alcohol (King et al., 2011). This was not the case, however, perhaps due to the novelty of the study beverage along with its stronger taste cues at the high alcohol dose. While heavy and light drinkers experience alcohol differently, it may be the case that the sensory aspects of the study beverage were most salient when definitively identifying beverage content. More specifically, olfactory and taste cues would have been consistent across all participants, regardless of drinking group. Therefore, we may speculate that the strength of these cues rendered drinking history less relevant and resulted in similar beverage identification rates between the groups, or alternatively, that the differential subjective effects experienced by heavy and light drinkers (stimulation or sedation) factored independently into alcohol identification, i.e., as a familiar effect after drinking.

Although the current study had many strengths, including a large sample, multiple alcohol doses, and a priori investigation of differential drinking patterns, there are limitations worth noting. First, the inclusion of several drug classes in the instructional set might have created novel expectancies about possible drug effects, though the information provided to participants emphasized similarity to commonly-used and legal substances (e.g., caffeine, antihistamine). A choice among several drug classes might have been especially salient for those who guessed they received a sedative, as the late afternoon and early evening sessions would have occurred when energy levels are lowest and participants are generally more sedated. Still, there was a sizable minority of participants who guessed they received a stimulant during one of the three sessions, and this advocates for its continued use as a guessing option. Second, we cannot ascertain the exact reasoning behind participants’ identification of beverage content, as strong taste cues are inherent in higher oral alcohol doses and likely decreased chances of incorrect guessing in the high dose alcohol condition. While most studies utilizing intravenous alcohol administration (Ramchandani, Plawecki, Li, & O'Connor, 2009; Ray et al., 2007; Zimmermann et al., 2008) do not employ the ASP, consideration of this method in such designs in the future would enable a more detailed analysis of subjective effects without the confound of taste cues on alcohol blinding. Third, this study might have been enhanced with more complex blinding procedures, such as the addition of a double-dummy, i.e., administering both a capsule and a beverage. Using such a design could increase the number of people who thought they received a combination of substances or a substance other than alcohol (i.e., sedative or stimulant). Though included in the questionnaire, most participants did not identify that a secondary substance had been administered within the beverage. That said, a double-dummy design should be thought out carefully as it could potentially create confusion with two modes of administration and might bias enrollment for those uncomfortable with capsule administration.

In sum, the current study demonstrates initial support for the ASP as a viable option in human alcohol laboratory studies. It has several advantages over prior paradigms in that it facilitates a within-subjects design, lessens recruitment bias for an “alcohol study,” and reduces ethical concerns of the antiplacebo cell as in the BPD. Since alcohol expectancies vary widely and may be important factors in human laboratory studies, the ASP represents a potentially important tool to capture acute responses in persons uninfluenced by recruitment into an “alcohol study” or by the knowledge of exclusively receiving alcohol during laboratory sessions. On the larger issue of assessing blinding, it is suggested that future research investigations address and routinely report on expectancy reduction, effectiveness of blinding, and ascertainment of manipulation checks (Breslin & Sobell, 1999).

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This research was supported by the NIH/NIAAA (#R01-AA013746), a Cancer Center grant (#P30-CA14599), and a General Clinical Research Center Grant (#M01-RR00055). These funding sources had no other role than financial support.

The authors would like to thank Harriet de Wit, Ph.D. for her role in experimental issues and Royce Lee, M.D. for performing medical screenings and providing medical oversight. We would also like to thank Irene Tobis, Ph.D., Curt Van Riper, Alyssa Epstein, Ph.D., Adrienne Dellinger, Lauren Kemp McNamara, and Ty Brumback, M.A. for conducting experimental sessions.

Footnotes

Presented in part at the 2009 Research Society on Alcoholism Conference, San Diego, CA

DISCLOSURES

All authors contributed significantly to the manuscript and have read and approved of this final version.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

- Acheson A, Mahler SV, Chi H, de Wit H. Differential effects of nicotine on alcohol consumption in men and women. Psychopharmacology. 2006;186:54–63. doi: 10.1007/s00213-006-0338-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breslin FC, Sobell SL. Alcohol administration methodology 1994-1995: What researchers do and do not report about subjects and dosing procedures. Addictive Behaviors. 1999;24:509–520. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4603(99)00002-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brumback T, Cao D, King A. Effects of alcohol on psychomotor performance and perceived impairment in heavy binge social drinkers. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2007;91:10–17. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2007.04.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burian SE, Hensberry R, Liguori A. Differential effects of alcohol and alcohol expectancy on risk-taking during simulated driving. Human Psychopharmacology: Clinical and Experimental. 2003;18:175–184. doi: 10.1002/hup.473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carpenter JA. Issues in research on alcohol. In: Fox R, editor. Ed.) Alcoholism: Behavioral Research, Therapeutic Approaches. Springer Publishing Company, Inc.; New York: 1967. pp. 16–23. [Google Scholar]

- Carpenter JA. Contributions from psychology to the study of drinking and driving. Quarterly Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1968;(Supplement 4):234–251. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chi H, de Wit H. Mecamylamine attenuates the subjective stimulant-like effects of alcohol in social drinkers. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2003;27:780–786. doi: 10.1097/01.ALC.0000065435.12068.24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corbin WR, Gearhardt A, Fromme K. Stimulant alcohol effects prime within session drinking behavior. Psychopharmacology. 2008;197:327–337. doi: 10.1007/s00213-007-1039-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cronce JM, Corbin WR. Effects of alcohol and initial gambling outcomes on within-session gambling behavior. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology. 2010;18:145–157. doi: 10.1037/a0019114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawson DA, Li TK, Grant BF. A prospective study of risk drinking: at risk for what? Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2008;95:62–72. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2007.12.00. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Wit H, Crean J, Richards JB. Effects of d-amphetamine and ethanol on a measure of behavioral inhibition in humans. Behavioral Neuroscience. 2000;114:830–837. doi: 10.1037//0735-7044.114.4.830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doty P, Kirk JM, Cramblett KJ, de Wit H. Behavioral responses to ethanol in light and moderate social drinkers following naltrexone pretreatment. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 1997;47:109–116. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(97)00094-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finnigan F, Hammersley R, Millar K. The effects of expectancy and alcohol on cognitive-motor performance. Addiction. 1995;90:661–672. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.1995.9056617.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frezza M, di Padova C, Pozzato G, Terpin M, Baraona E, Lieber CS. High blood alcohol levels in women. The role of decreased gastric alcohol dehydrogenase activity and first-pass metabolism. New England Journal of Medicine. 1990;322:95–99. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199001113220205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giancola PR. Influence of subjective intoxication, breath alcohol concentration, and expectancies on the alcohol-aggression relation. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2006;30:844–850. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2006.00099.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenstein JE, Kassel JD, Wardle MC, Veilleux JC, Evatt DP, Heinz AJ, Roesch LL, Braun AR, Yates MC. The separate and combined effects of nicotine and alcohol on working memory capacity in nonabstinent smokers. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology. 2010;18:120–128. doi: 10.1037/a0018782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holdstock L, de Wit H. Individual differences in responses to ethanol and d-amphetamine: A within-subject study. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2001;25:540–548. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes JR, Krahn D. Blindness and the validity of the double-blind procedure. Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology. 1985;5:138–142. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones BT, Corbin W, Fromme K. A review of expectancy theory and alcohol consumption. Addiction. 2001;96:57–72. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2001.961575.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keyes KM, Grant BF, Hasin DS. Evidence for a closing gender gap in alcohol use, abuse, and dependence in the United States population. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2008;93:21–29. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2007.08.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King AC, de Wit H, McNamara PJ, Cao D. Rewarding, stimulant and sedative alcohol responses and relationship to future binge drinking. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2011;68:389–399. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King AC, Epstein AM. Alcohol dose-dependent increases in smoking urge in light smokers. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2005;29:547–552. doi: 10.1097/01.alc.0000158839.65251.fe. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King AC, Houle T, de Wit H, Holdstock L, Schuster A. Biphasic alcohol response differs in heavy versus light drinkers. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2002;26:827–835. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King AC, McNamara PJ, Angstadt M, Phan KL. Neural substrates of alcohol-induced smoking urge in heavy drinking nondaily smokers. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2010;35:692–701. doi: 10.1038/npp.2009.177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King AC, McNamara PJ, Conrad MF, Cao D. Alcohol-induced increases in smoking behavior for nicotinized and denicotinized cigarettes in men and women. Psychopharmacology. 2009;207:107–17. doi: 10.1007/s00213-009-1638-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King A, Munisamy G, de Wit H, Lin S. Attenuated cortisol response to alcohol in heavy social drinkers. International Journal of Psychophysiology. 2006;59:203–209. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpsycho.2005.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koshi EB, Short CA. Placebo theory and its implications for research and clinical practice: A review of the recent literature. Pain Practice. 2007;7:4–20. doi: 10.1111/j.1533-2500.2007.00104.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin CS, Earleywine M, Musty RE, Perrine MW, Swift RM. Development and validation of the Biphasic Alcohol Effects Scale. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 1993;17:140–146. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1993.tb00739.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin CS, Sayette MA. Experimental design in alcohol administration research: Limitations and alternatives in the manipulation of dosage-set. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1993;54:750–761. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1993.54.750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKay D, Schare M. The effects of alcohol and alcohol expectancies on subjective reports and physiological reactivity: A meta-analysis. Addictive Behaviors: An International Journal. 1999;24:633–647. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4603(99)00021-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKee SA, Harrison ELR, Shi J. Alcohol expectancy increases positive responses to cigarettes in young, escalating smokers. Psychopharmacology. 2010;210:355–364. doi: 10.1007/s00213-010-1831-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mintzer MZ, Griffiths RR. Alcohol and false recognition: A dose-effect study. Psychopharmacology. 2001;159:51–57. doi: 10.1007/s002130100893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morean ME, Corbin WR. Subjective response to alcohol: A critical review of the literature. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2010;34:385–395. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2009.01103.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA) Helping Patients Who Drink Too Much: A Clinician's Guide. Bethesda, MD.: NIH Pub No. 05-3769. [Google Scholar]

- Ramchandani VA, Flury L, Morzorati S, Kareken D, Blekher T, Foroud T, Li TK, O'Connor S. Recent drinking history: Association with family history of alcoholism and acute response to alcohol during a 60 mg% clamp. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2002;63:734–744. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2002.63.734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramchandani VA, O'Connor S, Blekher T, Kareken D, Morzorati S, Nurnberger J, Li TK. A preliminary study of acute responses to clamped alcohol concentration and family history of alcoholism. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 1999;23:1320–1330. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramchandani VA, Plawecki M, Li TK, O'Connor S. Intravenous ethanol infusions can mimic the time course of breath alcohol concentrations following oral alcohol administration in healthy volunteers. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2009;33:938–44. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2009.00906.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ray LA, Hutchison KE. Effects of naltrexone on alcohol sensitivity and genetic moderators of medication response. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2007;64:1068–1077. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.64.9.1069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ray LA, Miranda R, Kahler CW, Leventhal AM, Monti PM, Swift R, Hutchison KE. Pharmacological effects of naltrexone and intravenous alcohol on craving for cigarettes among light smoker: A pilot study. Psychopharmacology. 2007;193:449–456. doi: 10.1007/s00213-007-0794-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rueger SY, McNamara PJ, King AC. Expanding the utility of the Biphasic Alcohol Effects Scale (BAES) and initial psychometric support for the Brief-BAES (B-BAES). Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2009;33:916–924. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2009.00914.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SAMHSA . National Survey on Drug Use and Health. Office of Applied Studies. Bethesda, MD.: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Schuckit MA, Smith TL. An 8-year follow-up of 450 sons of alcoholic and control subjects. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1996;38:861–868. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1996.01830030020005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sutker PB, Tabakoff B, Goist KC, Jr., Randall CL. Acute alcohol intoxication, mood states and alcohol metabolism in women and men. Pharmacology, Biochemistry, and Behavior. 1983;18:349–354. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(83)90198-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler D. WAIS-R Intelligence Manual: Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale-Revised. Harcourt, Brace, & Jovanovich; New York: 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Zimmermann US, Mick I, Vitvitskyi V, Plawecki MH, Mann KF, O'Connor S. Development and pilot validation of computer-assisted self-infusion of alcohol (CASE): A new method to study alcohol self-administration in humans. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2008;32:1321–1328. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2008.00700.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]