Abstract

Mammalian heart cells undergo a marked reduction in proliferative activity shortly after birth, and thereafter grow predominantly by hypertrophy. Our understanding of the molecular mechanisms underlying cardiac maturation and senescence is based largely on studies at the whole-heart level. Here, we investigate the molecular basis of the acquired quiescence of purified neonatal and adult cardiomyocytes, and use microRNA interference as a novel strategy to promote cardiomyocyte cell cycle re-entry. Expression of cyclins and cyclin-dependent kinases (CDKs) and positive modulators were down-regulated, while CDK inhibitors and negative cell cycle modulators were up-regulated during postnatal maturation of cardiomyocytes. The expression pattern of microRNAs also changed dramatically, including increases in miR-29a, miR-30a and miR-141. Treatment of neonatal cardiomyocytes with miRNA inhibitors anti-miR-29a, anti-miR-30a, and antimiR-141 resulted in more cycling cells and enhanced expression of Cyclin A2 (CCNA2). Thus, targeted microRNA interference can reactivate postnatal cardiomyocyte proliferation.

Keywords: Cell cycle, Cardiomyocytes, Cyclins, microRNA, Western blot

Introduction

The mammalian heart grows by hyperplasia during intrauterine life, but cardiomyocyte proliferation becomes increasingly rare after birth. Instead, postnatal cardiac growth is dominated by cardiomyocyte hypertrophy [1,2], although new cardiomyocytes can form throughout life at a low rate [3,4]. Up to 30% of cardiomyocytes can eventually enter into S phase, but rarely progress to mitosis and cytokinesis [5]. Despite the stereotypical cell cycle withdrawal of postnatal cardiomyocytes in vivo, such cells possess substantial cellular plasticity in vitro, with dedifferentiation and cell cycle reactivation [6].

Mechanistic studies have focused primary on the expression of cell cycle molecules at the transcript and protein levels. While few studies included dissociated cardiomyocytes, whole heart preparations were used extensively in previously studies, despite the fact that they contain diverse cell populations including cardiomyocytes, endothelial cells, smooth muscle cells and fibroblasts [7–10]. Interventions targeting defined elements of the cell cycle have yielded enhanced yet scant cardiac proliferation and growth [9,11]. During the past decade, microRNAs (miRNAs), a group of small non-coding endogenous RNAs ~22 nucleotides in length, have emerged as critical regulators of mRNA and protein expression, adding to the complex post-transcriptional regulatory network [12–16]. Here we characterize the expression levels of cell cycle-related molecules (mRNA and protein) and regulatory miRNAs in purified cardiomyocytes from neonatal and adult rat hearts. Exposure of neonatal rat cardiomyocytes (NRCMs) to selected anti-miRNAs enhanced the expression of cyclin and sustained higher cell cycle activity, providing an alternative strategy to treat heart diseases where cardiac growth is deficient.

Materials and Methods

Dissociation, purification and primary culture of cardiomyocytes

Animal procedures were conducted in accordance with humane animal care standards outlined in the NIH Guide for the Care and Use of Experimental Animals; and the study was approved by the Cedars-Sinai Medical Center Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC 2423). NRCMs were isolated from newborn pups (1d, Wistar-Kyoto) as described [17]. Briefly, ventricles were dissected by cutting out the lower 70% of the heart, chopped into 6 even pieces, and washed in HBSS to remove blood. The heart tissues were incubated with Trypsin (1 mg/ml) on a shaker overnight at 4°C. After the wash and quench of Trypsin, the tissues were digested for several time by collagenase (0.3 mg/ml) at 37°C for 1–2 minutes in a rotating bottle until the tissues completely dissociated, and the collagenase solution (containing NRCMs) collected and quenched by fetal bovine serum (FBS). Isolated cells were washed, filtered through 40 µm cell strainer, and then pre-plated in tissue culture flask for 45 minutes twice at 37°C to remove fibroblasts. Enriched NRCMs were plated in 1 million cells/well in 12-well plates, resulting in about 50% confluence on the day of initial plating. The culture medium was Medium 199 (Invitrogen) supplemented with 1% MEM non-essential amino acids, 2 mM L-glutamine, 100 U/mL penicillin, 100 µg/mL streptomycin, plus 10% FBS for the first day of culture, and 2% starting on the second day of culture. Cells were remained in for 3 to 6 days with 50% medium replacement every 2 days.

Adult cardiomyocytes were enzymatically dissociated using Liberase (Roche Applied Science; in 0.1–0.15 Wunsch collagenase Unit/ml) from 4-month- and 1-year-old Wistar-Kyoto rat hearts with a Langendorff apparatus, followed by purification steps [6]. Differential centrifugation and multiple pre-plating steps were adopted to obtain highly-purified cardiomyocyte preparations that were directly used for gene and protein expression analysis, or culture on laminin-coated cover glass in multi-well plates to verify the purify. The purity of NRCM as well as adult cardiomyocytes was assessed by immunocytochemical detection of cardiac markers α-myosin heavy chain (α-MHC) and non-cardiac markers CD90 (for fibroblasts) and CD31 (for endothelial cells). Staining with mitochondrial dye tetramethylrhodamine methyl ester perchlorate (TMRM) was performed for NRCM preparations as a complementary purity assessment using flow cytometry [18]. Cells were incubated with TMRM (50 nM; Sigma) dissolved in IMDM medium at 37°C for 20 minutes, followed by wash and 20-minute incubation in normal IMDM to remove unbound dye. Approximately 90% of post-plated cells stained strongly with TMRM as compared to ~70% of the preplating population, verifying the enrichment of NRCMs using the above cited methods (Supplemental Figure S1).

Protein extraction and western blotting

Myocytes were lysed with RIPA buffer (Thermo Scientific, Rockford, IL) supplemented with protease inhibitor cocktails (Roche Applied Sciences, Indianapolis, IN), and phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (0.5 mM), 2-Mecaptoethanol (0.5 mM), Na3VO4 (1 mM), NaF (10 mM), and β-glycerophosphate (1 mM). Extracted total proteins were quantified by Bicinchoninic Acid (BCA) Protein Assay kit (Pierce), followed by denaturation in sample buffer at 100°C for 5 minutes. Western Blots were performed as described previously [19] to evaluate the expression of cell cycle-related proteins using antibodies against CCND1 (1:500, Cell Signaling), CCNA2 (1:500, Abcam), CCNB1 (1:200, Abcam), CDK1/Cdc2 (1:500, Millipore), CDK2 (1:200, Abcam), CDK4, CDK6, p15, p16, p21, and p27 (1:500, 1:500, 1:1000, 1:500, 1:200, and 1:500 respectively, from Cell Signaling), p53 and p57 (1:500 and 1:400, respectively, Abcam), H3K4m2 (dimethylated histone H3 at lysine 4, 1:4000, Epitomics), Telomerase (1:200, Abcam. Horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies were used, and the signals were visualized by using SuperSignal West Femto maximum sensitivity substrate (Thermo Scientific) and exposed to Gel Doc™ XR System (Bio-Rad). Signal intensity of target molecules was analyzed using QuantityOne software (Bio-Rad), and expressions were normalized by that of Glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) (antibody from Epitomics, 1:2000).

Real-time PCR

Total RNA (containing microRNA) were isolated from NRCMs or adult cardiomyocytes using Ambion’s mirVANA kit [6]. The expression of cell cycle-related genes were performed using 384-well RT2 Profiler PCR array from SABiosciences (Frederick, MD) while microRNAs were detected using TaqMan Low Density Array Rodent MicroRNA A+B Cards Set v2.0 (Applied Biosystems), according to manufacturers’ protocols. Real-time qPCR detection and data extraction were performed on SDS 7900 Fast system (Applied Biosystems) and the accompanying software.

Transfection of anti-microRNA

miRNA inhibitors anti-miR-29a, anti-miR-30a, and anti-miR-141, and anti-miR negative control #1 were purchased from Ambion. Transfection of anti-miRs in NRCMs at final concentrations of 10 or 100 nM with Lipofectamine 2000 Reagent (Invitrogen) were performed on the first day of plating. Two days post-transfection, cells were collected and total protein or total RNA was extracted in order to evaluate the levels of cell cycle gene transcripts and regulatory miRNAs.

Flow cytometry

Flow cytometry was performed on a FACScan (Becton Dickinson) to analyze NRCM purity in conjunction with TMRM staining, and to analyze the cell cycle in anti-miRNA-treated NRCMs complemented with Propidium Iodide (PI) staining. For cell cycle evaluation, harvested NRCMs were fixed with 70% Ethanol for 15 minutes at room temperature followed by PI staining at 37°C for 40 minutes before being subjected to flow cytometry analysis. Acquired data were analyzed using FlowJo (Tree Star, Inc, Ashland, OR) with the cell cycle module with Watson model to fit cell cycle phases.

Data analysis and statistics

PCR array data were analyzed with Data Assist software (Applied Biosystems), with four endogenous controls (U6 rRNA, snoRNA135, U87, and Y1) for normalization, and Benjamini-Hocheberg FDR-adjusted p<0.05 was taken as significant. Expression data of transcripts and miRNAs in postnatal cardiomyocytes were processed using Ingenuity IPA software (www.ingenuity.com) for data mining of regulated microRNA and genes. Additionally, TargetScan, PicTar and Tarbase were used to identify potential miRNA targets. Group data are expressed as Mean ± S.E. unless specified. Difference between groups was evaluated by student t test, with a p<0.05 considered significantly different.

Results

Progressive down-regulation of cyclins and cyclindependent kinases (cdks) genes in adult cardiomyocytes

We assessed the purity of NRCM preparations by checking for contamination by CD90 or CD31. At all times assessed (2 hr, 3 days and 6 days), such contamination was present in ~5% of cells (Supplemental Figure S2). Highly-purified NRCMs developed spontaneous contractile activity and grew progressively larger over 6 days in culture (Supplemental Figure S3). Within 6 days, NRCMs entered into a quiescent state of the cell cycle as revealed by FACS profiling, with only ~12% of cells in cycling phases (S/G2/M) (Supplemental Figure S4). To characterize the basis of the changes, we examined the expression of genes and proteins pertaining to cell cycle regulation in myocytes at different stages.

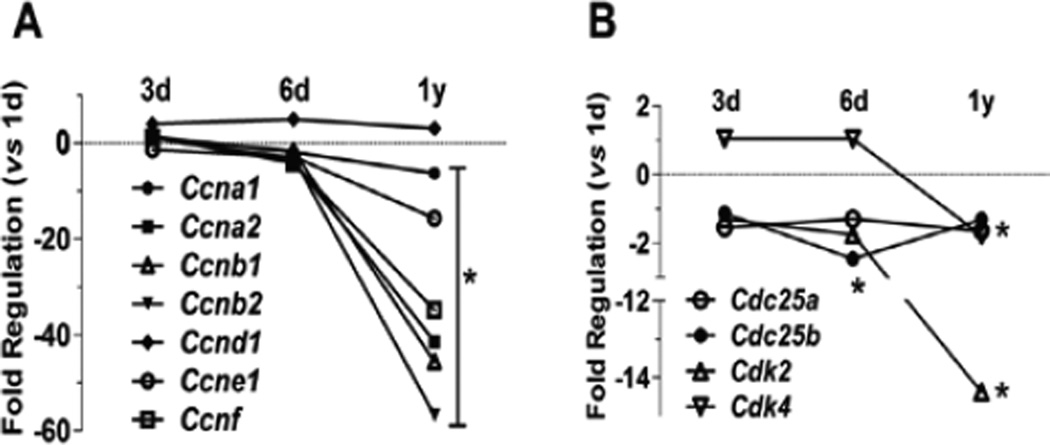

As illustrated in Figure 1, the levels of cyclin and CDK transcripts in cardiomyocytes gradually decreased over the first 6 days of postnatal maturation, and then steeply declined over one year. Compared to newborn cardiomyocytes (1d), cyclin A (Ccna1 and Ccna2) responsible for initiating the G1/S transition was reduced by 1.9- and 3.8-fold in 6-day culture when the cells retreated from active cell cycle, and plummeted 6.3- and 41.5-fold in 1-year old myocytes. Another G1-S cyclin gene, Ccne1, was also remarkably down-regulated (p<0.05). The S/G2/M phase cyclins Ccnb1 and Ccnb2 were reduced significantly in 6d or 1yr cardiomyocytes. The G0 phase cyclin D gene Ccnd1 was increased slightly (3–5 fold) during postnatal maturation, but remained essentially unchanged at 1 year. On the other hand, CDKs that form partners with cyclins in order to function actively, were reduced in parallel, e.g. Cdk2 decreased 14.3-fold in 1-year myocytes as compared to 1 day myocytes (p<0.05). Genes of the Cell Division Cycle (CDC) 25 family, such as Cdc25a and Cdc25b, have been demonstrated to activate G1/S phase CDKs (e.g. Cdk4/6) and M phase CDK1 thus moving forward the cell cycling in progression [20]; Cdc25a and Cdc25b were down-regulated 1–2 fold during postnatal development.

Figure 1. Reduction of genes encoding cyclins and cyclin-dependent kinases (CDKs).

Expression of cyclin (A) and CDK (B) genes detected by real-time qPCR in 3d, 6d and 1 year (1y) myocytes as compared to NRCM at 1d. For better visualization, SE bar is omitted. *p<0.05 vs 1d.

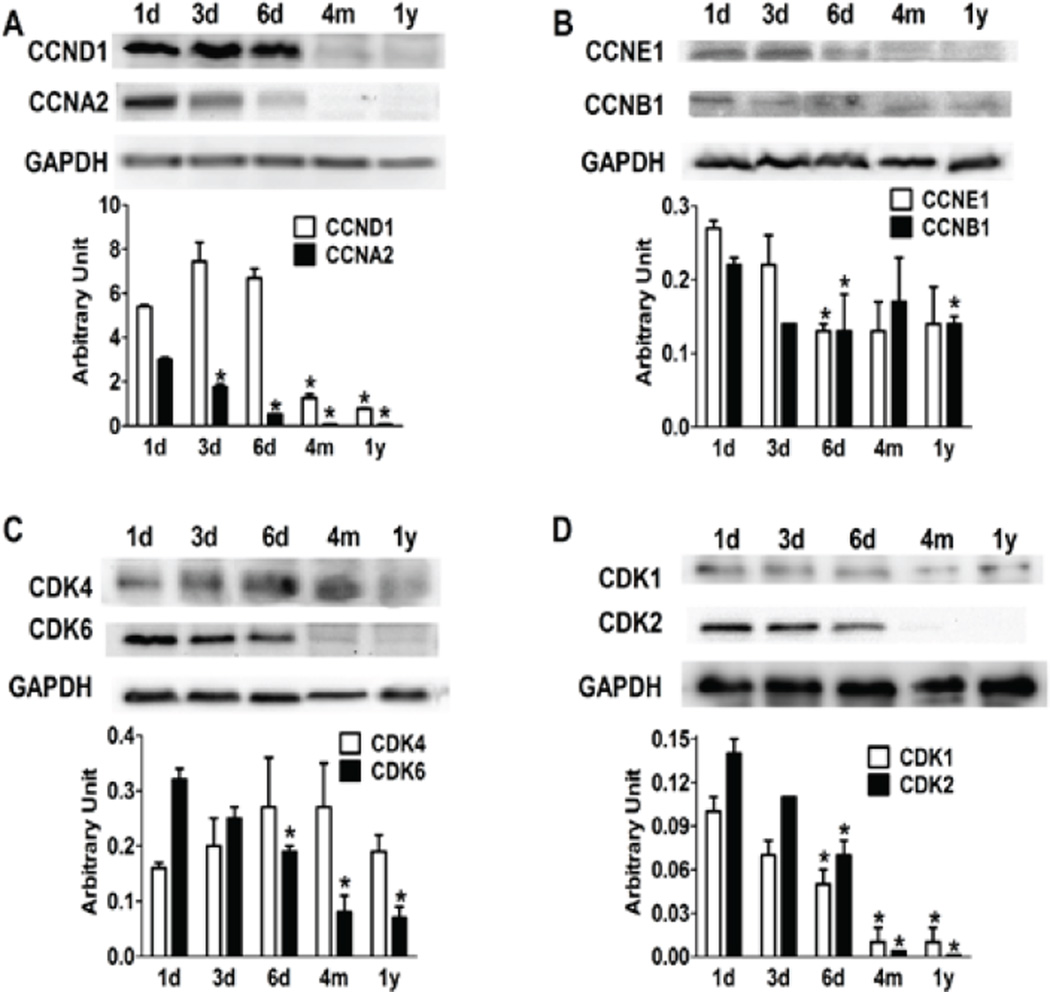

At the protein level, there were also remarkable changes during postnatal growth and maturation. Western blots revealed significant reduction of most cyclin and CDK proteins (Figure 2). Among the cyclins, both Ccnd1 and Ccna2 were more abundant in the neonatal period, but vanished in the adult, although Ccnd1 transcript did not change significantly in adult myocytes as compared to that in NRCMs (Figure 2A, Figure 1A). Ccne1 and Ccnb1, important for G1/S and S/M progression, were expressed sparsely in neonatal cardiomyocytes, and were further reduced in adult (4-month and 1 year-old) cells (Figure 2B). Most CDK proteins were down-regulated in 4-month adult cardiomyocytes, and barely detectable in old (1 year) myocytes (Figure 2C, Figure 2D).

Figure 2. Expression levels of cyclin and cyclin-dependent kinase (CDK) proteins during postnatal maturation of cardiomyocytes.

Western blots reveal most cyclins (A, B) and CDKs (C, D) are down-regulated in postnatal myocytes as compared to new born (1d) myocytes. *p<0.05 vs 1d.

The data are consistent with the reduced cell cycle activity observed in the heart after birth [21].

Progressively up-regulation of inhibitory cell cycle molecules in cardiomyocytes

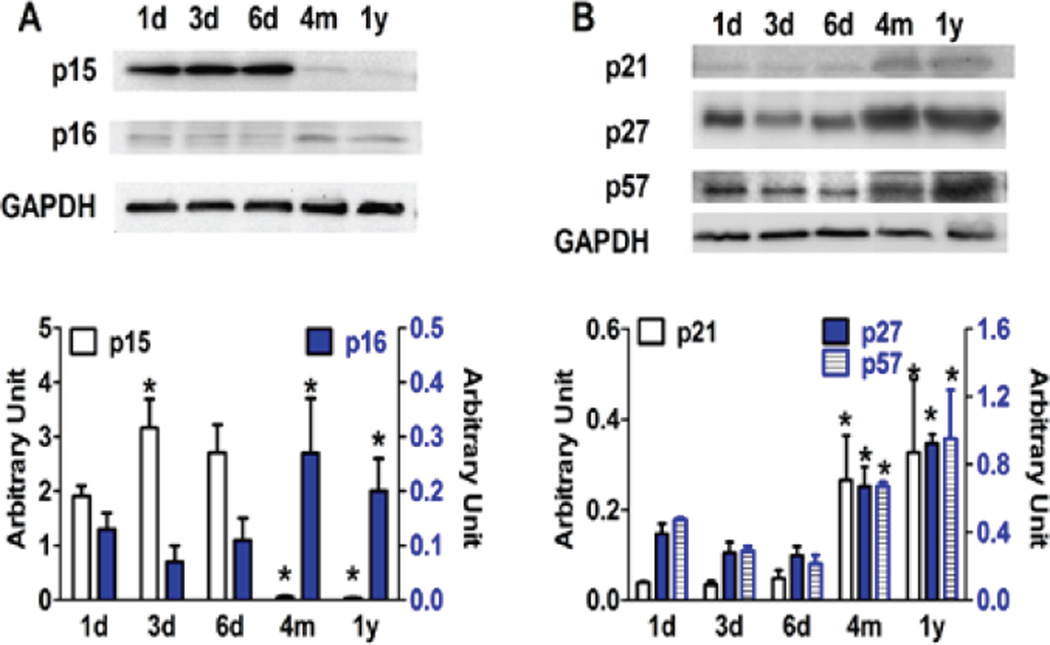

Since the cell cycle status is determined by tightly-regulated cyclins and CDKs that are usually positive molecules, and counteracted by checkpoint controllers that inhibit cell cycle progression, we also evaluated the levels of the key inhibitors, INK4 and CIP/KIP families of cell cycle molecules in cardiomyocytes. Except for p15, all members of INK4 and CIP/KIP were upregulated in 4-month and 1-year old cardiomyocytes, while remaining relative stable during the first week of in vitro development (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Expression levels of CDK inhibitors during postnatal maturation of cardiomyocytes.

Western blots reveal that most CDK inhibitors are upregulated in postnatal myocytes as compared to new born (1d) myocytes. *p<0.05 vs 1d.

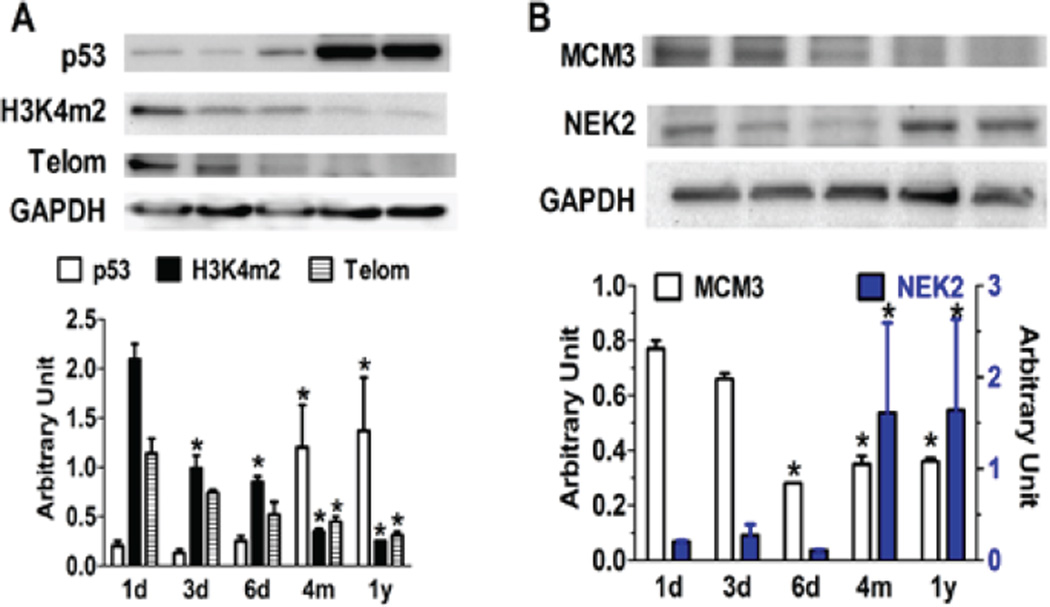

Expressions of cell cycle regulators

Cell cycle activity is controlled by both the positive molecules (e.g. cyclins and CDKs) and the negative regulators such as CDK inhibitors that form a binding complex for cell cycle progression or inhibition. There are also other intermediate regulators that control the cell cycle, such as p53 and telomerase. As shown in Figure 4, p53, a tumor repressor that promotes cell cycle arrest, was dramatically up-regulated in adult cardiomyocytes, while the level of methylated Histone 3 at lysine 4 (H3K4me), a transcriptional activation modulator, was down-regulated. Telomerase, responsible for the maintenance of DNA length during genetic replication, also reduced in adult cardiomyocytes. These regulators, together with cyclins, CDKs, and CDKIs tightly restrict cell cycle progression in adult myocytes.

Figure 4. Expression levels of intermediate cell cycle regulators during postnatal maturation of cardiomyocytes.

Western blots show the upregulation of cell cycle repressor p53, but down-regulation of transcription activator di-methylated Histone 3 at lysine 4 (H3K4m2) and telomerase (Telom) in postnatal myocytes as compared to new born cells (1d). vs 1d.

Expression of microRNA in cardiomyocytes during postnatal cardiac development

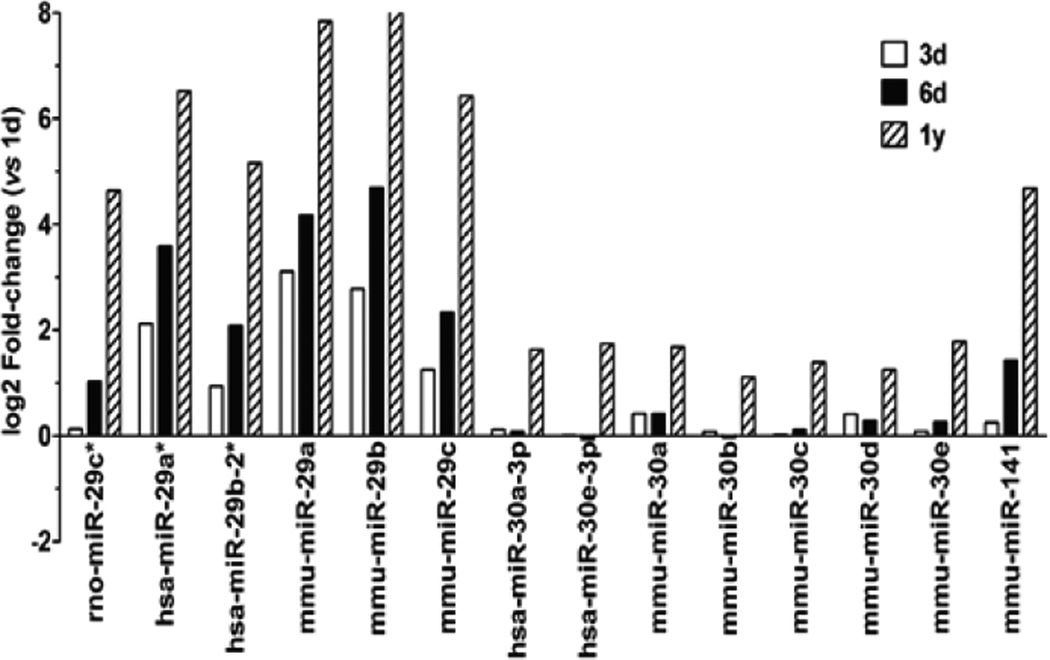

Increasing evidence demonstrates that transcript levels and protein expression are post-transcriptionally regulated by a group of non-coding regulatory microRNA [12]. During postnatal development, cardiomyocytes undergo significant changes in miRNA expression as compared to new born cells. Among 582 miRNAs tested in the qPCR array, 358 miRNAs were present in either group of cells, and 19 miRNAs were down-regulated while 14 miRNAs were upregulated with more than 2-fold changes during in vitro cardiac development (Supplemental Table S1). Further analysis revealed that miR-29, miR-30, and miR-141 families were all up-regulated in 6-day or 1-year old cardiomyocytes (Figure 5). In contrast, the expression of these miRs is significantly down-regulated in dedifferentiated cardiomyocytes which have regained proliferative ability [6].

Figure 5. Expression of miRNAs in postnatal cardiomyocytes.

Real-time qPCR revealed a panel of gradually up-regulated miRNA in 3d, 6d and 1y myocytes as compared to new born (1d) myocytes.

Anti-miRNA treatments in NRCM enhanced cyclin expression and increased cycling cells

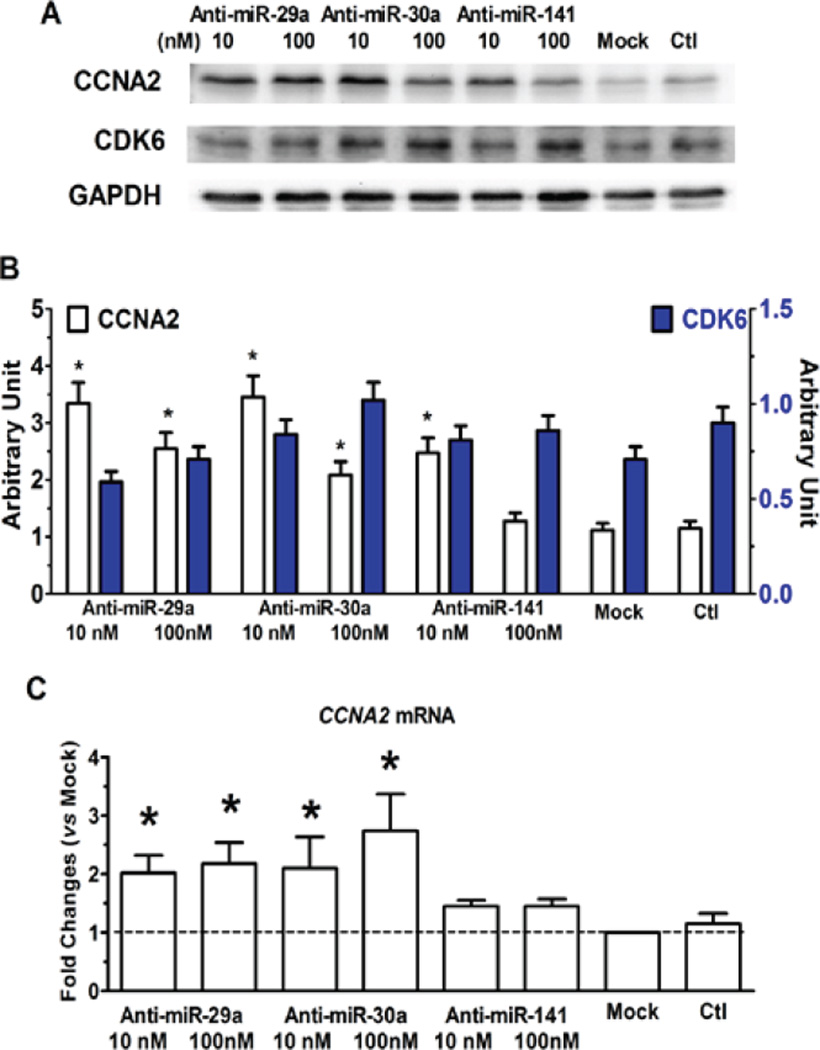

To evaluate the potential application of miRNA interference technology in regulating the cardiomyocyte cell cycle, relationships between the expression of mRNA, miRNA, and cell cycle protein were analyzed by IPA software. The miRNAs which were significantly regulated during maturation (quiescence) and dedifferentiation (and proliferation) of cardiomyocytes were then searched against the databases for target gene prediction. We identified that Ccna2 and CDK6 are among the predicted targets of miR-29, miR-30 or miR-141 (Supplemental Figure S5–S7), which are all upregulated during cardiac development (Figure 5). NRCMs were therefore treated with inhibitors of miRs (anti-miRs), including anti-miR-29a, anti-miR-30a, and anti-miR-141. As shown in Figure 6A and 6B, Ccna2 protein expression increased significantly in NRCMs exposed to anti-miRs, while the expression of CDK6 trended higher (p>0.05) as compared to that in untreated cells. The effects of anti-miRs on Ccna2 protein expression were correlated with enhanced mRNA expression (Figure 6C), consistent with relief of miRNA-mediated inhibition by the anti-miRs. Both CDK1/Cdc25b and CDK2 expression were slightly enhanced by anti-miR treatments but not significant different as compared to untreated cells (Data not shown).

Figure 6. Effects of Anti-miRNAs on cell cycle regulators.

Changes of protein expression resulted from anti-miRNA treatment to neonatal rat cardiomyocytes for 2 days assayed by Western blots (A, B). C, Fold changes of CCNA2 gene detected by real-time qPCR. *p<0.05 vs Mock treatment.

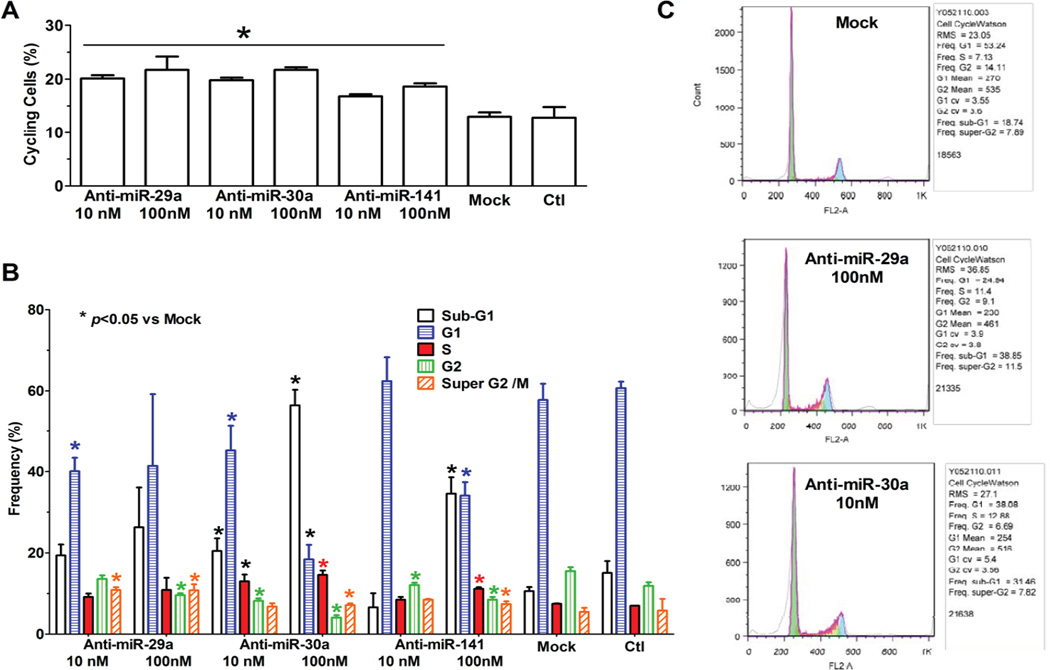

Up-regulation of Ccna2 by anti-miRNA inhibitors was accompanying with more cycling cells as compared to that of untreated groups. For example, treatment with both anti-miR-29a and anti-miR-30a for 2 days increased the number of cells in active cell cycle (in S or M phase) more than one fold as compared to mock-treatment of normally quiescent NRCMs during in vitro maturation (Figure 7).

Figure 7. Promotion of cell cycle in neonatal rat cardiomyocytes (NRCMs) by anti-miRNAs.

Anti-miRNA treatments of NRCMs for 2 days resulted in more cells in cycling phases (S or M phases) as revealed by flow cytometry (A, B). C, example flow cytometry plots fit with Watson model for cell cycle analysis. *p <0.05 vs Mock.

Discussion

The limit growth activity of cardiomyocytes in normal and diseased hearts has attracted attentions of generations of scientists and physicians to battle the life threatening cardiovascular conditions such as heart failure. Since the discovery of resident (adult) cardiac stem cells, cell-based therapies have been demonstrated to play a complex (beneficial) role in treating degenerative diseases such as congestive heart failure. However, the overall regeneration rate of cardiomyocytes from cardiac differentiation of either implanted or endogenous stem cells is very limited as compared to the amount of lost myocytes during a heart attack [22–24]. The confirmation of dedifferentiation and proliferation of cardiomyocytes has again drawn the attention to promote the proliferative activity of existing cardiomyocytes that possess the common genetic backgrounds as in other potent and active cycling cells [6,25–27].

Cell cycle activity is tightly controlled by a network of various molecules. Cyclins and CDKs can form complexes to promote the progression through cell cycle, while the cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitors (CDKIs) are proteins that interact with cyclin-CDK complexes to block kinase activity. There are two major CDKI families in animal cells:

1) The INK4 (Inhibitors of CDK4) family that includes p15, p16, p18 and p19, and exclusively binds to and inhibits the D-type cyclindependent kinases (CDK4 and CDK6); and 2) the Cip/Kip family which includes p21, p27 and p57, and inhibits broadly the activity of Cyclin-CDK complexes [28,29]. Previous gene-targeting studies aiming to promote myocyte proliferation based on the mixed results from whole-heart assays revealed enhanced yet still limited cell growth [5,30].

In this study, we compared purified postnatal cardiomyocytes in their expressions of major cell cycle molecules. We found consistent reduction of most cyclin and CDK molecules in our study with purified myocytes as compared to previous reports – they decreased during early postnatal in vitro development and were barely detectable in adult cardiomyocytes (Figures 1 and 2) [31,32]. Most cell cycle inhibitors, including p16, p21, p27 and p57 were instead higher in purified adult cardiomyocytes (Figure 3) [33]; this is different from previous studies showing undetectable level of p16, or reduced levels of p27 and p57 in whole heart preparation [34]. The reduction of p15 in purified adult cardiomyocytes may be compensated by the upregulation of other CDK inhibitors, including p27 which partners with p15 to regulate CDK4/CDK2 [35]. The combination of reduction in cyclins/CDKs along with increase in CDKIs results in cell cycle quiescence in adult cardiomyocytes. Additionally, augmentation of p53 and reduction of both H3K4m2 and telomerase (Figure 4) further enforce the arrest of cell cycle shortly after birth. On the other hand, when cardiomyocytes undergo dedifferentiation, the inhibitory cell cycle regulators such as p21 and p53 reduce remarkably, allowing myocytes to re-enter the cell cycle [6]. These molecular phenotypes suggest that cell cycle/proliferation and maturation/dedifferentiation are tightly regulated in cardiomyocytes.

Recently, miRNAs have been demonstrated not only critical in cardiovascular development, but also regulate the cell cycle activity in postnatal cardiomyocytes [15,36]. Porrello et al. compared the microRNA profiles in postnatal mouse hearts (P1 and P10) and determined that miR-15 family is regulated during postnatal cardiac development [36] Our qPCR data (not shown) revealed only mild changes for all the miR-15 family members in rat cardiomyocytes, suggesting that the role of miR-15 in regulating cardiomyocyte proliferation may be species-specific. It has been shown that miR-29 and miR-30 are more abundant in cardiac fibroblasts and target collagens; the downregulation of miR-29 or miR-30 in infarcted myocardium is associated with cardiac fibrosis [37,38]. However, the roles of these miRs in cardiomyocyte maturation and function during development remain elusive. Our study reveals a remarkable change of miRNA profile at different time points, especially the progressively upregulated miR-29, miR-30 and miR-141, as these are downregulated in dedifferentiated and proliferative adult cardiomyocytes [6]. Recent study on full panel of miRNA profiles in 2-day and 4-week old rat myocytes confirmed that miR-29 and miR-30 expressions are increased in adult myocytes, and anti-miR29a treatment to the neonatal myocytes results in more cycling cells by releasing the suppressed Ccnd2 gene [39]. Therefore, miR-29 can target to multiple cell-cycle-related genes. A previous study revealed that triple knockdown of inhibitory cell cycle regulators such as p21, p27, and p53 by siRNAs promoted cell cycle activity in cardiomyocytes [40]. We found that postnatal inhibition of the repressive miRNAs resulted in significant increase of CCNA2 mRNA and protein (Figure 6), confirming in-silico predictions (Supplemental Figure S5–S7). As CCNA2 is essential for both G1/S transition (by binding to CDK2) and passage into mitosis including in postnatal cardiomyocytes [41,42], we found significantly increased cycling postnatal cardiomyocytes with anti-miRNA treatments that are targeting to the increased miRNAs during postnatal myocyte quiescence. As different isoforms of miR-29 (a, b, and c) and miR-30 (a, b, c, d, and e) have conservative core sequences and their predicted targeting sites to the 3’UTR of CCNA2 or Cdk6 are highly homologous, it is likely that using antimiRs for other isoforms of miR-29 or miR-30 will have similar effects on these genes. miRNA has been demonstrated to play critical roles in the dedifferentiation and proliferation of retinal pigment cell [43], chondrocytes [44], mesenchymal stem cells [45], and Schwann cells [46]. The well-established in vitro neonatal cardiomyocyte culture model, together with adult cardiomyocyte analysis used in this study, provides insight into the molecular regulatory network that composes of mRNA, microRNA and protein. Further experimentation will be required to test whether these miRNAs are indeed key players in promoting myocyte proliferation. Our data and recent studies on miRNA profiling [39] and functional screening [47] demonstrate that developmentally regulated miRNAs can be promising targets for myocyte cell cycle control thereby cardiac regeneration.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Prabhav Anand for the preparation of NRCMs and Christian Houde for the assistance in protein analysis. E.M. holds the Mark S. Siegel Family Professorship of the Cedar-Sinai Medical Center.

Grants

This study was funded by NIH Grant R01HL083109 (to E.M.). Y.Z. was supported by the Research Fellowship from the Heart and Stroke Foundation of Canada.

Dr. Marbán is a founder and equity holder in Capricor Inc. Capricor provided no funding for the present study.

Footnotes

Disclosures

The remaining authors report no conflicts.

References

- 1.De Falco M, Cobellis G, De Luca A. Proliferation of cardiomyocytes: a question unresolved. Front Biosci (Elite Ed) 2009;1:528–536. doi: 10.2741/e49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schneider MD. Myocardial infarction as a problem of growth control: cell cycle therapy for cardiac myocytes? J Card Fail. 1996;2:259–263. doi: 10.1016/s1071-9164(96)80049-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bergmann O, Bhardwaj RD, Bernard S, Zdunek S, Barnabé-Heider F, et al. Evidence for cardiomyocyte renewal in humans. Science. 2009;324:98–102. doi: 10.1126/science.1164680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Marbán E. Big cells, little cells, stem cells: agents of cardiac plasticity. Circ Res. 2007;100:445–446. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000260271.33215.9b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ahuja P, Sdek P, MacLellan WR. Cardiac myocyte cell cycle control in development, disease, and regeneration. Physiol Rev. 2007;87:521–544. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00032.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhang Y, Li TS, Lee ST, Wawrowsky KA, Cheng K, et al. Dedifferentiation and proliferation of mammalian cardiomyocytes. PLoS One. 2010;5:e12559. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0012559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Banerjee I, Fuseler JW, Price RL, Borg TK, Baudino TA. Determination of cell types and numbers during cardiac development in the neonatal and adult rat and mouse. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2007;293:H1883–H1891. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00514.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nag AC. Study of non-muscle cells of the adult mammalian heart: a fine structural analysis and distribution. Cytobios. 1980;28:41–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pasumarthi KB, Field LJ. Cardiomyocyte cell cycle regulation. Circ Res. 2002;90:1044–1054. doi: 10.1161/01.res.0000020201.44772.67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zak R. Development and proliferative capacity of cardiac muscle cells. Circ Res. 1974;35:17–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bicknell KA, Coxon CH, Brooks G. Can the cardiomyocyte cell cycle be reprogrammed? J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2007;42:706–721. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2007.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.He L, Hannon GJ. MicroRNAs: small RNAs with a big role in gene regulation. Nat Rev Genet. 2004;5:522–531. doi: 10.1038/nrg1379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Latronico MV, Condorelli G. MicroRNAs and cardiac pathology. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2009;6:419–429. doi: 10.1038/nrcardio.2009.56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhao Y, Samal E, Srivastava D. Serum response factor regulates a muscle-specific microRNA that targets Hand2 during cardiogenesis. Nature. 2005;436:214–220. doi: 10.1038/nature03817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Liu N, Olson EN. MicroRNA regulatory networks in cardiovascular development. Dev Cell. 2010;18:510–525. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2010.03.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mutharasan RK, Nagpal V, Ichikawa Y, Ardehali H. microRNA-210 is upregulated in hypoxic cardiomyocytes through Akt- and p53-dependent pathways and exerts cytoprotective effects. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2011;301:H1519–H1530. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01080.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kizana E, Chang CY, Cingolani E, Ramirez-Correa GA, Sekar RB, et al. Gene transfer of connexin43 mutants attenuates coupling in cardiomyocytes: novel basis for modulation of cardiac conduction by gene therapy. Circ Res. 2007;100:1597–1604. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.106.144956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hattori F, Chen H, Yamashita H, Tohyama S, Satoh YS, et al. Nongenetic method for purifying stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes. Nat Methods. 2010;7:61–66. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhang Y, Xiao J, Wang H, Luo X, Wang J, et al. Restoring depressed HERG K+ channel function as a mechanism for insulin treatment of abnormal QT prolongation and associated arrhythmias in diabetic rabbits. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2006;291:H1446–H1455. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01356.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nilsson I, Hoffmann I. Cell cycle regulation by the Cdc25 phosphatase family. Prog Cell Cycle Res. 2000;4:107–114. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4615-4253-7_10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yoshizumi M, Lee WS, Hsieh CM, Tsai JC, Li J, et al. Disappearance of cyclin A correlates with permanent withdrawal of cardiomyocytes from the cell cycle in human and rat hearts. J Clin Invest. 1995;95:2275–2280. doi: 10.1172/JCI117918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bernstein HS, Srivastava D. Stem cell therapy for cardiac disease. Pediatr Res. 2012;71:491–499. doi: 10.1038/pr.2011.61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Huu AL, Prakash S, Shum-Tim D. Cellular cardiomyoplasty: current state of the field. Regen Med. 2012;7:571–582. doi: 10.2217/rme.12.28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mohsin S, Siddiqi S, Collins B, Sussman MA. Empowering adult stem cells for myocardial regeneration. Circ Res. 2011;109:1415–1428. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.111.243071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mercola M, Ruiz-Lozano P, Schneider MD. Cardiac muscle regeneration: lessons from development. Genes Dev. 2011;25:299–309. doi: 10.1101/gad.2018411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Porrello ER, Mahmoud AI, Simpson E, Hill JA, Richardson JA, et al. Transient regenerative potential of the neonatal mouse heart. Science. 2011;331:1078–1080. doi: 10.1126/science.1200708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kubin T, Pöling J, Kostin S, Gajawada P, Hein S, et al. Oncostatin M is a major mediator of cardiomyocyte dedifferentiation and remodeling. Cell Stem Cell. 2011;9:420–432. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2011.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Denicourt C, Dowdy SF. Cip/Kip proteins: more than just CDKs inhibitors. Genes Dev. 2004;18:851–855. doi: 10.1101/gad.1205304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Vidal A, Koff A. Cell-cycle inhibitors: three families united by a common cause. Gene. 2000;247:1–15. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(00)00092-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lorts A, Schwanekamp JA, Elrod JW, Sargent MA, Molkentin JD. Genetic manipulation of periostin expression in the heart does not affect myocyte content, cell cycle activity, or cardiac repair. Circ Res. 2009;104:e1–e7. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.108.188649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kang MJ, Kim JS, Chae SW, Koh KN, Koh GY. Cyclins and cyclin dependent kinases during cardiac development. Mol Cells. 1997;7:360–366. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kang MJ, Koh GY. Differential and dramatic changes of cyclin-dependent kinase activities in cardiomyocytes during the neonatal period. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 1997;29:1767–1777. doi: 10.1006/jmcc.1997.0450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Poolman RA, Gilchrist R, Brooks G. Cell cycle profiles and expressions of p21CIP1 AND P27KIP1 during myocyte development. Int J Cardiol. 1998;67:133–142. doi: 10.1016/s0167-5273(98)00320-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Koh KN, Kang MJ, Frith-Terhune A, Park SK, Kim I, et al. Persistent and heterogenous expression of the cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor, p27KIP1, in rat hearts during development. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 1998;30:463–474. doi: 10.1006/jmcc.1997.0611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Reynisdóttir I, Massagué J. The subcellular locations of p15(Ink4b) and p27(Kip1) coordinate their inhibitory interactions with cdk4 and cdk2. Genes Dev. 1997;11:492–503. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.4.492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Porrello ER, Johnson BA, Aurora AB, Simpson E, Nam YJ, et al. MiR-15 family regulates postnatal mitotic arrest of cardiomyocytes. Circ Res. 2011;109:670–679. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.111.248880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.van Rooij E, Sutherland LB, Thatcher JE, DiMaio JM, Naseem RH, et al. Dysregulation of microRNAs after myocardial infarction reveals a role of miR-29 in cardiac fibrosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:13027–13032. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0805038105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Duisters RF, Tijsen AJ, Schroen B, Leenders JJ, Lentink V, et al. miR-133 and miR-30 regulate connective tissue growth factor: implications for a role of microRNAs in myocardial matrix remodeling. Circ Res. 2009;104:170–178. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.108.182535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cao X, Wang J, Wang Z, Du J, Yuan X, et al. MicroRNA profiling during rat ventricular maturation: A role for miR-29a in regulating cardiomyocyte cell cycle re-entry. FEBS Lett. 2013;587:1548–1555. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2013.01.075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Di Stefano V, Giacca M, Capogrossi MC, Crescenzi M, Martelli F. Knockdown of cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitors induces cardiomyocyte reentry in the cell cycle. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:8644–8654. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.184549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chaudhry HW, Dashoush NH, Tang H, Zhang L, Wang X, et al. Cyclin A2 mediates cardiomyocyte mitosis in the postmitotic myocardium. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:35858–35866. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M404975200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Morgan DO. Cyclin-dependent kinases: engines, clocks, and microprocessors. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 1997;13:261–291. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.13.1.261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tsonis PA, Call MK, Grogg MW, Sartor MA, Taylor RR, et al. MicroRNAs and regeneration: Let-7 members as potential regulators of dedifferentiation in lens and inner ear hair cell regeneration of the adult newt. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2007;362:940–945. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.08.077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hong E, Reddi AH. Dedifferentiation and redifferentiation of articular chondrocytes from surface and middle zones: changes in microRNAs-221/222, -140, and -143/145 expression. Tissue Eng Part A. 2013;19:1015–1022. doi: 10.1089/ten.TEA.2012.0055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Liu Y, Jiang X, Zhang X, Chen R, Sun T, et al. Dedifferentiation-reprogrammed mesenchymal stem cells with improved therapeutic potential. Stem Cells. 2011;29:2077–2089. doi: 10.1002/stem.764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Viader A, Chang LW, Fahrner T, Nagarajan R, Milbrandt J. MicroRNAs modulate Schwann cell response to nerve injury by reinforcing transcriptional silencing of dedifferentiation-related genes. J Neurosci. 2011;31:17358–17369. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3931-11.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Eulalio A, Mano M, Dal Ferro M, Zentilin L, Sinagra G, et al. Functional screening identifies miRNAs inducing cardiac regeneration. Nature. 2012;492:376–381. doi: 10.1038/nature11739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.