Abstract

Background

Longlasting and unbearable pain is the most common and striking symptom of chronic pancreatitis. Accordingly, pain relief and improvement in patients' quality of life are the primary goals in the treatment of this disease. This systematic review aims to summarize the available data on treatment options.

Methods

A systematic search of MEDLINE/PubMed and the Cochrane Library was performed according to the PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analysis. The search was limited to randomized controlled trials and meta-analyses. Reference lists were then hand-searched for additional relevant titles. The results obtained were examined individually by two independent investigators for further selection and data extraction.

Results

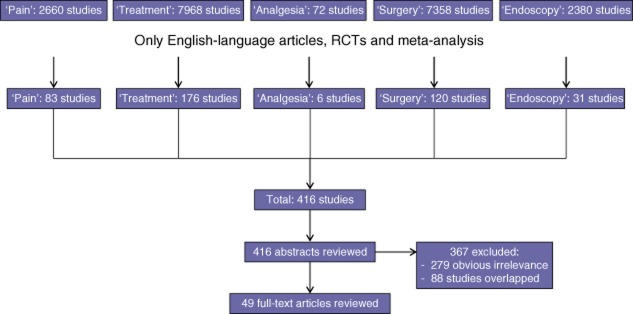

A total of 416 abstracts were reviewed, of which 367 were excluded because they were obviously irrelevant or represented overlapping studies. Consequently, 49 full-text articles were systematically reviewed.

Conclusions

First-line medical options include the provision of pain medication, adjunctive agents and pancreatic enzymes, and abstinence from alcohol and tobacco. If medical treatment fails, endoscopic treatment offers pain relief in the majority of patients in the short term. However, current data suggest that surgical treatment seems to be superior to endoscopic intervention because it is significantly more effective and, especially, lasts longer.

Introduction

Chronic pancreatitis (CP) is a painful inflammatory disease that leads to progressive and irreversible destruction of the pancreatic parenchyma.1,2 Recurrent episodes of acute pancreatitis may result in tissue fibrosis and the loss of exocrine and endocrine function, along with steatorrhea, malabsorption, diabetes and unbearable pain.3 The majority of patients with CP demonstrate constant or recurrent severe and often opioid-refractory abdominal pain. Pancreatic pain characteristically presents as deeply penetrating and dull epigastric pain, which radiates to the back and is often worsened by ingestion. This classical pattern of pain is not universal, and the character, location and quality of pain can be quite inconsistent.4

A pathophysiological mechanism for pain in CP that has been repeatedly discussed is the increase in intrapancreatic pressure either within the pancreatic duct or in the pancreatic parenchyma, which leads to ischaemia and the inflammation of pancreatic tissue.5,6 It is noteworthy in this context, however, that there seems to be no direct relationship between the presence of duct dilatation and pain.7 Furthermore, it has long been recognized that the severity of abdominal pain sensations correlates with the extent of intrapancreatic neural damage and alterations.8,9 However, the underlying molecular pathways are incompletely understood and probably multifactorial. A hypothesis that is increasingly discussed proposes that neural inflammatory cell infiltration leads to pancreatic neuritis and neural plasticity with enlarged nerves and the formation of a dense intrapancreatic neural network. All these neural alterations are responsible for causing the characteristic pancreatic neuropathy and consequent neuropathic pain.8–12 Because the underlying pain mechanisms are just beginning to be understood, the treatment of pain in CP is often empirical and insufficient. The objective of this article was to review, summarize and assess the level of evidence on the effectiveness of different treatment options in painful CP.

Materials and methods

Searches of the MEDLINE, PubMed and Cochrane Library databases were performed using the search terms ‘pain’, ‘treatment’, ‘analgesia’, ‘surgery’ and ‘endoscopy’ and, alternatively, these terms matched with ‘chronic pancreatitis’ for papers published from the inception of the database in question to 31 March 2013. Searches were limited to English-language articles describing randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and meta-analyses as these are considered to represent the highest level of evidence.

The results obtained were examined individually by two independent investigators (JGD'H, GOC). Firstly, titles and abstracts were read; if the article was considered relevant by at least one of the investigators, full-text articles were retrieved and studied. Articles for inclusion were required to report on studies that had systematically investigated any form of treatment in patients with painful CP and used pain reduction as one of their outcome measures. Articles reporting on studies outwith the scope of the review and those that overlapped across the searches were excluded. Reference lists extracted from the 49 full-text articles published between 1983 and 2012 and selected for systematic review were hand-searched for additional relevant titles.

The following study characteristics were extracted from the articles: authors; publication year; publishing journal; study design and size; study duration; type of intervention, and outcome measures related to pain. Studies were categorized according to the primarily investigated treatment strategy for painful CP based on whether they referred to medical treatment, interventional treatment (including endoscopic and radiological interventions), surgical treatment, and any comparisons between any of these types of treatment.

Results

The initial search identified 416 articles. Duplicate studies were excluded (n = 88). Screening of titles and abstracts resulted in the exclusion of a further 279 articles, the content of which fell outwith the scope of this review and was obviously irrelevant (Fig. 1). Finally, 49 studies were included for full-text review.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram showing the present literature review, determination of eligibility and inclusion of studies in the systematic review. RCT, randomized controlled trial

Medical treatment

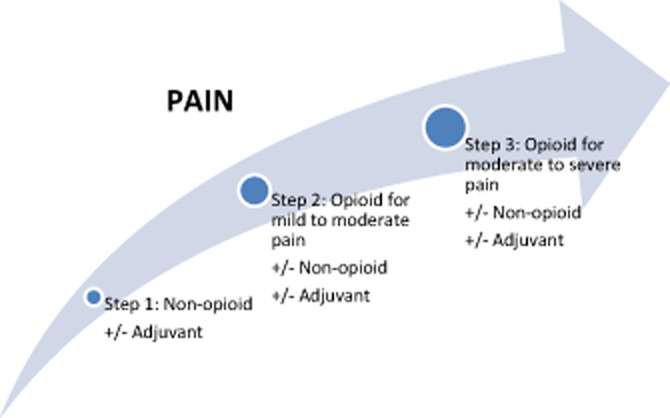

The initial challenge in CP concerns making the correct diagnosis. Early-stage CP has been recognized in the context of endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) when patients present with typical pancreatic-type pain. However, whether these EUS findings represent true early-stage CP that will progress or whether they are false positive findings remains unclear.13 Diagnosis can be especially challenging in small duct disease because patients often lack characteristic structural changes. Accordingly, patients with small duct CP are generally poorly represented in all of the published studies on treatment of painful CP. Once the diagnosis of CP is confirmed, patients are advised to maintain a strict abstinence from tobacco and alcohol and require longterm analgesic medications for pain control. For pain medication titration, the step-up approach of the analgesic ladder described by the World Health Organization (WHO) is proposed (Fig. 2). Tramadol is one of the few analgesic medications to have been prospectively evaluated in painful CP and has been shown to be equivalent to more potent narcotics, with a lower incidence of gastrointestinal side-effects and less potential for addiction.14 Transdermal fentanyl plaster may be useful in some patients, but it is not the ideal first-choice analgesic because it implies a considerable need for additional rescue morphine and skin-related side-effects.15 Allopurinol has been shown to be ineffective in a very small randomized trial.16 Although evidence is low for CP pain, the additional treatment of these pain states with non-narcotic adjunctive medications such as selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) has become increasingly popular as these agents have been successfully used in other chronic pain states.17,18 Because pancreatic pain syndrome has been identified as neuropathic,8 novel approaches for pain treatment have been tested. Here, the gabapentoid pregabalin has been identified as a successful therapeutic tool in adjunctive medication for the treatment of pancreatic pain in patients with CP.19–22

Figure 2.

The analgesic ladder defined by the World Health Organization. Adapted from the World Health Organization101

Pancreatic enzyme supplementation is frequently used in patients with painful CP although, despite several prospective trials and meta-analysis, evidence for pain reduction through pancreatic enzyme replacement remains inconsistent.23–29 However, as pancreatic enzyme supplementation usually has positive effects on diarrhoea, fat malabsorption and weight loss with no relevant side-effects, a therapeutic regime with a pancreatic enzyme supplement is generally appropriate for 6–8 weeks and should be discontinued if it proves ineffective.30,31 In such instances, non-enteric coated enzymes should always be prescribed, together with a proton-pump inhibitor to prevent the hydrolysis of the enzyme by gastric acid.32

Other medical therapies, such as antioxidants or octreotide, used in the treatment of CP have been repeatedly studied and discussed, but the results of these investigations remain inconclusive and therefore the use of these therapies is not recommended in daily routine.33–39 This is underlined by the results of the most recent RCT on the use of antioxidants (the ANTICIPATE Study) which did not show any effect on pain in patients with CP.40 Researchers evaluating these placebo-controlled studies should keep in mind the finding that the pooled estimated placebo rate of abdominal pain remission in clinical trials of CP has been shown to be almost 20%, which can make interpretation of results quite difficult.41

Acupuncture and transcutaneous electric nerve stimulation were evaluated during the mid-1980s, but neither proved to show any substantial pain relief that could substitute for or supplement medical treatment.42

Interventional treatment

Coeliac block

If sufficient pain relief cannot be achieved by medical therapy, and if there is no sign of pancreatic or biliary duct obstruction, more invasive strategies should be considered. As most pancreatic nociceptive afferents are thought to pass through the coeliac ganglion, nerve block (anaesthetic and/or steroid) or neurolysis (alcohol) represent common treatment options for pancreatic pain. About half of patients treated with EUS-guided coeliac block for painful CP experience a significant decrease in pain.43 Here, EUS-guided techniques have proven safer, more effective and more longlasting than fluoroscopy-guided or computed tomography (CT)-guided techniques.43–45 The addition of triamcinolone to standard bupivacaine for the EUS-guided block does not increase pain relief or lengthen the effects and it makes no difference whether one or two injections are applied.46,47 A single old and underpowered randomized study comparing the effects of coeliac plexus block with a surgical procedure (pancreaticogastrostomy) suggests the operative procedure provides better longterm results.48 Unfortunately, in most cases coeliac nerve block shows only a transient effect and persistent pain relief is maintained in only about 10% of patients at 24 weeks.49 Therefore, this therapeutic option seems to be more effective and reasonable in patients with malignant disease and a short anticipated lifespan. However, neural block strategies to achieve temporary pain relief may be considered in patients with CP and severe pain.50

Thoracoscopic splanchnicectomy

A more invasive procedure that is similar to the percutaneous or endoscopic coeliac plexus block is bilateral thoracoscopic splanchnicectomy. This can be performed with a higher degree of precision and avoids the side-effects associated with the local diffusion of neurolytic solutions.51 However, similarly to the coeliac plexus block, most studies show that thoracoscopic splanchnicectomy seems to be more effective in the short term because early good results decline with time after the intervention.52 Given the contradictory results reported in the literature, thoracoscopic splanchnicectomy cannot be recommended as a standard treatment option to achieve the longterm relief of pain in CP.

Endoscopy

Endoscopic therapy aims to relieve pain by draining the main pancreatic or biliary duct to reduce the pressure of the pancreatic parenchyma. It may be used for the treatment of local complications, such as ductal strictures, stones or pancreatic pseudocysts, in appropriately pre-selected patients. Nearly half of patients referred for non-surgical pancreatic duct drainage procedures require the extraction of obstructing stones. This is traditionally attempted by endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) after pancreatic sphincterotomy if the stones are <10 mm in diameter, not too numerous and located in the main duct.53 Unfortunately, many patients do not meet these criteria and are therefore not suitable for endoscopic treatment. However, large, retrospective, non-randomized multicentre series have demonstrated that in a very select group of patients with ductal anatomy that is amenable to endoscopic therapy, significant pain relief can be achieved (with a median of three ERCPs) in approximately two-thirds of all treated patients.54,55 A randomized trial comparing the outcomes of endoscopic stenting with those of a sham procedure for painful CP, in which the improvement of abdominal pain is the primary endpoint, is currently recruiting.56

Extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy

In addition to endoscopic therapy, extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy (ESWL) is a safe method of fragmenting stones prior to ERCP and should therefore be considered to decrease the number of ERCPs needed for successful stone clearance.57 Furthermore, increasing evidence demonstrates that ESWL alone may be an effective solitary option in patients with painful CP and pancreatic duct dilatation.58–60

Surgical treatment

Classical indications for surgery in CP are stenosis of the common bile duct or the duodenum, vascular obstruction, pseudocysts, the suspicion of neoplasm, and abdominal pain that fails to respond to conservative and endoscopic treatment options. The main purpose of a surgical intervention in CP is the relief of pain and the simultaneous preservation of as much of the pancreatic parenchyma as possible. Very few studies have examined the optimal timing of surgical therapy, but the resulting data indicate that early intervention would seem to be more beneficial. A study published by Nealon and Thompson suggested that early operative duct decompression should be performed in patients with CP because it can delay the progressive functional destruction of the pancreas.61 Ihse et al. drew similar conclusions in patients with dilatation or obstruction of the pancreatic duct and biliary pancreatitis,62 whereas others have described a progressive functional impairment despite surgery.63 The latest study identified surgery within 3 years of the onset of symptoms, fewer than five previous endoscopic treatments, and the absence of preoperative opioid use as independent factors associated with the achievement of greater pain relief.64 Similar results were shown recently by van der Gaag et al., who were able to show that preoperative daily opioid use and high numbers of preceding endoscopic procedures are associated with persistent severe pain.65 Furthermore, these authors showed that both physical and mental quality of life (QoL) remained postoperatively impaired in comparison with QoL in the general population.65 However, it is apparent across the studies that the lack of any commonly accepted system for staging CP makes comparisons very difficult. Therefore, current data are still insufficient to allow for final recommendations, but suggest that an early surgical intervention within the first 3 years of the onset of symptoms may be beneficial.66

The first surgical attempts to relieve pancreatic pain in CP were initiated in the early 19th century and were focused on the draining of the pancreatic duct by means of pancreatostomy67 or pancreatic left resection.68 Since then, surgical strategies for the treatment of CP have continuously evolved. Puestow and Gillesby were the first to combine a pancreatic left resection with a longitudinal opening of the pancreatic duct and an anastomosis to the small intestine.69 Only 2 years later, Partington and Rochelle published what they called a ‘modified’ Puestrow–Gillesby procedure, in which they preserved the tail of the pancreas and extended the opening of the pancreatic duct.70 This surgical technique is nowadays known as the Partington–Rochelle procedure and continues to be used in surgical practice, with low morbidity and mortality, especially in patients with dilated pancreatic ducts of >7 mm. This drainage operation has been shown to facilitate longterm pain relief in around 60–70% of patients, although some groups have reported even higher success rates of up to 98% in selected patients.71,72

Drainage operations are usually ineffective in patients without dilatation of the main pancreatic duct. These patients' pain sensations are thought to evolve from neuropathic changes within the pancreatic head, as described earlier. Long before these underlying neural alterations are discovered, the pancreatic head is identified as the leading site of the disease, often carrying a dominant inflammatory mass.73 Therefore, several surgical procedures have been applied for the resection of the pancreatic head. The standard Kausch–Whipple procedure for the radical resection of the pancreatic head, duodenum and gastric antrum with the pylorus and gallbladder was initially established in the early 19th century for the treatment of malignancies of the pancreatic head and the periampullary region, but has subsequently also been used in the resection of inflammatory pancreatic head masses. As a result of relatively high rates of gastrointestinal symptoms and diabetes mellitus, the classic Kausch–Whipple procedure has often been replaced by the pylorus-preserving Whipple procedure introduced by Traverso and Longmire in 1978.74,75 This Traverso–Longmire procedure has proven to lead to longterm pain relief in around 90% of patients with painful CP.75,76 In the long term, however, the pylorus-preserving procedure has not been shown to offer any clear advantages in terms of gastrointestinal symptoms and diabetes mellitus.77 Therefore, pancreaticoduodenectomy either with or without pylorus preservation may be considered in patients with painful CP. In severe cases of CP in which the entire gland is affected, even total pancreatectomy is a viable option, in which perioperative morbidity and mortality are comparable with those of the Traverso–Longmire procedure and the resultant overall QoL is acceptable.78 However, based on the rationale that a resection of the gastric antrum, duodenum and common bile duct in benign disease may represent an overtreatment, Hans-Günther Beger introduced the duodenum-preserving resection of the pancreatic head in 1972.73 In the Beger procedure, the neck of the pancreas is divided over the portal vein, and the head and uncinate process of the pancreas are carefully excised, sparing the duodenum and the intrapancreatic bile duct. Fifteen years later, Frey and colleagues described a variation of the Beger procedure involving a more limited and organ-preserving resection in which the pancreatic head is decorticated and the duct is widely opened. Drainage is then achieved by pancreaticojejunostomy.79 The Frey procedure is commonly regarded as technically easier than the Beger operation because it does not require the dissection of the pancreas above the portal vein and the reconstruction is less complex. The Beger procedure was later modified by Markus W. Büchler to only partial resection of the pancreatic head and a short-range lateral pancreaticojejunostomy, known as the Berne technique.80,81 In 1998, Izbicki et al. introduced another parenchyma-preserving procedure in which a longitudinal V-shaped excision of the anterior pancreas is performed; nowadays this is not commonly performed, but it remains a treatment option, particularly in patients with small duct CP.82 Finally, Müller and colleagues have described a middle segmental pancreatic resection for use in patients with focal CP using a linear cutter and a retrocolic Roux-en-Y limb of jejunum for reconstruction, in which morbidity and mortality rates are comparable with those of other pancreatic resection procedures.83 One study suggests that perioperative octreotide may reduce the risk for postoperative complications in patients undergoing major pancreatic surgery for CP.84

When it comes to the issue of which of these procedures represents the optimal choice, evidence is limited to some monocentre trials and two meta-analyses (Table 1). In the first RCT on the type of surgical treatment for painful CP, Klempa and colleagues compared the classic Whipple procedure (n = 21) with the Beger procedure (n = 22). Here, patients submitted to a Beger procedure experienced less pain, better gain in body weight, better endocrine function and a shorter hospital stay.85 A similar study was published in 1995 by Büchler et al., who compared the duodenum-preserving pancreatic head resection (n = 20) with the pylorus-preserving Whipple procedure (n = 20). Again, the duodenum-sparing resection provided a better outcome in terms of pain relief, weight gain, glucose tolerance and insulin secretion capacity.80 However, these convincing early advantages of the Beger procedure were not maintained during the longterm follow-up of these patients (up to 14 years).86 Two randomized trials have compared the pylorus-preserving Whipple procedure with the Frey procedure; both showed the two procedures to be equally efficient in terms of providing pain relief. However, they also showed that the Frey procedure results in better QoL, although postoperative endocrine and exocrine pancreatic function were equivalent.82,87,88 Strate et al. compared the Beger procedure (n = 38) with the Frey procedure (n = 36) and were unable to show any difference between those two surgical options in mortality, QoL, pain relief, or exocrine and endocrine function.89 These data underline previous findings by Izbicki and colleagues in a slightly smaller cohort.90 Köninger et al. state that the Büchler procedure can be performed significantly faster and leads to a shorter hospital stay than the Beger operation.91 Finally, the most recent randomized trial was published in 2012 by Keck and colleagues, who found no difference between duodenum preservation and resection and suggested that both techniques are equally effective in the short and long term.92 The recently published protocol for the ChroPac Trial pertains to the first large, multicentre RCT to compare duodenum-preserving pancreatic head resection with pancreatoduodenectomy with the primary outcome represented by the patient's QoL at 24 months after surgery.93 The first results of this trial are expected in late 2013. Although 24 months may not represent a sufficiently long period for the estimation of longterm results, it is hoped that the trial will provide a better idea of the short-term outcomes and morbidity rates associated with these procedures. Until then, surgeons will be required to rely on the data currently available from these small trials. The existing data are best summarized in a recently published meta-analysis, in which duodenum-preserving pancreatic head resections (including those of the Beger, Frey and Büchler procedures) and pancreatoduodenectomy were shown to be equally effective in terms of pain relief, overall morbidity and incidence of postoperative endocrine insufficiency.94 However, the duodenum-preserving pancreatic head resection seems to be superior in terms of postoperative weight gain, exocrine and endocrine function, and longterm QoL. Similar results were obtained for the Beger and Frey procedures;94 however, the most recent meta-analysis suggests that the Beger procedure provides for better pain relief but higher morbidity, and the Frey procedure provides less sufficient pain relief but lower morbidity.95 Therefore, any of these surgical techniques are appropriate for the surgical treatment of painful CP. However, with reference to postoperative functional outcome, it should be remembered that most of these series show a postoperative deterioration in pancreatic function to some extent, which is probably unavoidable when pancreatic tissue is operatively removed. Furthermore, any interpretation of the longterm results of these studies should be made in the awareness that pancreatic pain may reduce spontaneously over time in line with the concept of ‘burnout’ outlined by Rudi Ammann et al. several years ago.96

Table 1.

Randomized controlled trials comparing surgical techniques in the treatment of painful chronic pancreatitis

| Techniques compared | Authors | Patients, n | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| Classic Whipple versus Beger | Klempa et al.85 | 43 | Beger procedure: less pain, greater weight gain, shorter hospital stay |

| Pylorus-preserving Whipple versus Beger | Büchler et al.80 | 40 | Beger procedure: less pain, greater weight gain, better glucose tolerance, higher insulin secretion capacity |

| Pylorus-preserving Whipple versus Frey | Izbicki et al.82 | 61 | Equally effective in terms of pain relief and definitive control of complications; Frey procedure provides better quality of life |

| Pylorus-preserving Whipple versus modification of Frey | Farkas et al.87 | 40 | Equally effective in pain relief; Frey procedure is superior in morbidity, hospital stay, and weight gain |

| Beger versus Frey | Strate et al.89 | 74 | Both procedures provide adequate pain relief and quality of life after longterm follow-up with no differences regarding exocrine and endocrine function |

| Beger versus Büchler | Köninger et al.91 | 65 | No differences in quality of life, significantly shorter operation times and hospital stay for the Büchler procedure |

| Pylorus-preserving Whipple versus duodenum-preserving pancreatic head resection (Beger or Frey or Büchler) | Diener et al.93 | Recruiting Aim = 200 | Expected 2013 |

A fairly new surgical technique that has been developed recently is that of autologous islet transplantation after total pancreatectomy. The most recent systematic review showed that a significant proportion of patients remained independent of need for insulin supplementation even in the long term (ranging from 46% at 5 years to 10% at 8 years).97 Although it may be too early to consider this option as a standard procedure, it may become a valid option in patients in whom total pancreatectomy is unavoidable.

Comparative studies

Endoscopic and surgical interventions are subject to controversy but both can be considered in CP patients in whom conservative pain treatment fails. Two RCTs have addressed the obvious question of whether endoscopic or surgical treatment is superior in the initial treatment of CP. Dite and colleagues were the first to investigate this controversial issue in an RCT.98 A total of 72 patients were randomized to either endoscopy or surgery, in which resection was the most common surgical procedure (80%) and surgical drainage was performed in 20% of patients. The most commonly performed endoscopic interventions were sphincterotomy and stenting, performed in 52% of patients, and/or stone removal, performed in 23% of patients in the endoscopy arm. Initial success rates in terms of pain relief were similarly high (>90% of patients achieved at least partial pain relief at 1 year) in both groups, but these clinical outcomes changed considerably at 3 years and 5 years of follow-up. In the surgical treatment group, 42% of patients were found to have maintained complete pain relief at 1 year, which marginally decreased to 41% at 3 years and 37% at 5 years. By contrast, patients in the endoscopic treatment arm initially showed an equally good clinical outcome, with 52% of patients enjoying complete pain relief at 1 year, but this effect substantially decreased to 11% at 3 years and 14% at 5 years. Accordingly, the rate of non-responders was disappointingly high at 33–35% in the endoscopy arm versus only 12–14% in the surgical treatment arm after 3 years and 5 years. Furthermore, similar outcomes in patient body weight became apparent. Initially, at 1 year after treatment, 60% of patients in the surgery treatment arm and 66% in the endoscopy arm achieved an increase in body weight, but this clinical outcome was found to have changed significantly at 5 years of follow-up. Only 27% of patients in the endoscopic treatment group showed a gain in body weight at 5 years, whereas >50% of patients in the surgical treatment group demonstrated a gain in body weight. In this RCT, Dite et al. were able to show for the first time that surgery seems to be superior to endoscopic treatment in terms of the achievement of longterm pain relief and gain in body weight.98

In 2007 Cahen and colleagues published a report on the second and more recent study on the same issue,99 and provided a very recent update of longterm follow-up in August 2011.100 Here, 39 patients were randomized to endoscopy (n = 19) or operative pancreaticojejunostomy (n = 20). Following an unscheduled interim analysis after a median follow-up of 24 months, the study was terminated early because of highly significant mean differences in the Izbicki pain score (11 versus 34) in favour of the surgical treatment arm (P < 0.001). Even more striking were the immense differences in the frequency of patients achieving complete or partial pain relief at the end of follow-up, with only 32% of patients in the endoscopic treatment group but 75% in the surgical treatment group showing at least partial relief. Furthermore, at longterm follow-up of up to 7 years, these numbers had not changed considerably (38% versus 80%). Additionally, endoscopically treated patients underwent significantly more re-interventions than surgically treated patients (n = 8 versus n = 3). There were no significant differences between the treatment groups in the number of complications. Although the endoscopy group experienced more overall complications than the surgery group (11 of 19 patients, 58%), all of these were minor. By contrast, only seven of 20 patients (35%) in the surgery group demonstrated complications. However, the only major complication to occur in the course of the trial developed in the surgery group. In addition, there were no differences between the treatment groups in the length of hospital stay or the number of hospital readmissions.100 On the basis of these results, the authors concluded that surgical drainage is superior to endoscopic treatment and should be regarded as the preferred treatment option.100 However, in less extensive disease, the authors still consider endoscopic treatment as a valuable alternative to surgery.100

Given the conclusions of these two RCTs, it would seem to be evident that surgical therapy is more effective and longer-lasting than endoscopic treatment and that rates of morbidity and mortality are comparable in both. Although these trials may be too small to enable the detection of possible differences in these secondary outcome measures, and larger RCTs may be required to confirm current evidence, surgical treatment for pain in CP must be regarded as the current standard of care. However, it should be noted that a subgroup of patients representing about 30% of the study population in both studies do seem to profit, even in the long term, from endoscopic treatment alone. A primary endoscopic approach may therefore also be justified in mild disease. Future studies should focus on further defining that group of patients who may benefit from a less invasive procedure.

Conclusions

Two of the primary goals in treating CP remain the provision of longterm pain relief and the facilitating of improvement in the patient's QoL. Achieving these goals remains an interdisciplinary challenge for radiologists, pain medicine specialists, gastroenterologists and surgeons. If pain relief and a consequent improvement in the patient's QoL cannot be achieved by medical therapy, current evidence suggests that surgery is the treatment of choice and is superior to endoscopic treatment. An initial endoscopic trial may be warranted, but, in the event of its failure, early surgical management is advised. Pancreatic resections can nowadays be performed with low morbidity and mortality in high-volume centres and can provide longterm pain relief in the vast majority of patients with painful CP. However, current evidence is largely based on the findings of small underpowered studies that demonstrate considerable risk for bias. Therefore, although they will be challenging to set up, larger RCTs with sufficient power are needed to confirm current evidence.

Conflicts of interest

None declared.

References

- 1.DiMagno EP. A short, eclectic history of exocrine pancreatic insufficiency and chronic pancreatitis. Gastroenterology. 1993;104:1255–1262. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(93)90332-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sarles H, Bernard JP, Johnson C. Pathogenesis and epidemiology of chronic pancreatitis. Annu Rev Med. 1989;40:453–468. doi: 10.1146/annurev.me.40.020189.002321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Witt H, Apte MV, Keim V, Wilson JS. Chronic pancreatitis: challenges and advances in pathogenesis, genetics, diagnosis, and therapy. Gastroenterology. 2007;132:1557–1573. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lankisch PG. Chronic pancreatitis. Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2007;23:502–507. doi: 10.1097/MOG.0b013e3282ba5736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Di Sebastiano P, di Mola FF, Büchler MW, Friess H. Pathogenesis of pain in chronic pancreatitis. Dig Dis. 2004;22:267–272. doi: 10.1159/000082798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ebbehoj N, Borly L, Bulow J, Rasmussen SG, Madsen P. Evaluation of pancreatic tissue fluid pressure and pain in chronic pancreatitis. A longitudinal study. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1990;25:462–466. doi: 10.3109/00365529009095516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kahl S, Zimmermann S, Genz I, Schmidt U, Pross M, Schulz HU, et al. Biliary strictures are not the cause of pain in patients with chronic pancreatitis. Pancreas. 2004;28:387–390. doi: 10.1097/00006676-200405000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ceyhan GO, Bergmann F, Kadihasanoglu M, Altintas B, Demir IE, Hinz U, et al. Pancreatic neuropathy and neuropathic pain – a comprehensive pathomorphological study of 546 cases. Gastroenterology. 2009;136:177–186. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.09.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ceyhan GO, Demir IE, Maak M, Friess H. Fate of nerves in chronic pancreatitis: neural remodelling and pancreatic neuropathy. Best Pract Res. 2010;24:311–322. doi: 10.1016/j.bpg.2010.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ceyhan GO, Bergmann F, Kadihasanoglu M, Erkan M, Park W, Hinz U, et al. The neurotrophic factor artemin influences the extent of neural damage and growth in chronic pancreatitis. Gut. 2007;56:534–544. doi: 10.1136/gut.2006.105528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ceyhan GO, Demir IE, Rauch U, Bergmann F, Müller MW, Büchler MW, et al. Pancreatic neuropathy results in ‘neural remodelling’ and altered pancreatic innervation in chronic pancreatitis and pancreatic cancer. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104:2555–2565. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2009.380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ceyhan GO, Michalski CW, Demir IE, Müller MW, Friess H. Pancreatic pain. Best Pract Res. 2008;22:31–44. doi: 10.1016/j.bpg.2007.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hernandez LV, Catalano MF. EUS in the diagnosis of early-stage chronic pancreatitis. Best Pract Res. 2010;24:243–249. doi: 10.1016/j.bpg.2010.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wilder-Smith CH, Hill L, Osler W, O'Keefe S. Effect of tramadol and morphine on pain and gastrointestinal motor function in patients with chronic pancreatitis. Dig Dis Sci. 1999;44:1107–1116. doi: 10.1023/a:1026607703352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Niemann T, Madsen LG, Larsen S, Thorsgaard N. Opioid treatment of painful chronic pancreatitis. Int J Pancreatol. 2000;27:235–240. doi: 10.1385/ijgc:27:3:235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Banks PA, Hughes M, Ferrante M, Noordhoek EC, Ramagopal V, Slivka A. Does allopurinol reduce pain of chronic pancreatitis? Int J Pancreatol. 1997;22:171–176. doi: 10.1007/BF02788381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Matsuzawa-Yanagida K, Narita M, Nakajima M, Kuzumaki N, Niikura K, Nozaki H, et al. Usefulness of antidepressants for improving the neuropathic pain-like state and pain-induced anxiety through actions at different brain sites. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2008;33:1952–1965. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1301590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Giannopoulos S, Kosmidou M, Sarmas I, Markoula S, Pelidou SH, Lagos G, et al. Patient compliance with SSRIs and gabapentin in painful diabetic neuropathy. Clin J Pain. 2007;23:267–269. doi: 10.1097/AJP.0b013e31802fc14a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Olesen SS, Bouwense SA, Wilder-Smith OH, van Goor H, Drewes AM. Pregabalin reduces pain in patients with chronic pancreatitis in a randomized, controlled trial. Gastroenterology. 2011;141:536–543. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Olesen SS, Graversen C, Olesen AE, Frokjaer JB, Wilder-Smith O, van Goor H, et al. Randomized clinical trial: pregabalin attenuates experimental visceral pain through sub-cortical mechanisms in patients with painful chronic pancreatitis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2011;34:878–887. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2011.04802.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Graversen C, Olesen SS, Olesen AE, Steimle K, Farina D, Wilder-Smith OH, et al. The analgesic effect of pregabalin in patients with chronic pain is reflected by changes in pharmaco-EEG spectral indices. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2012;73:363–372. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2011.04104.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bouwense SA, Olesen SS, Drewes AM, Poley JW, van Goor H, Wilder-Smith OH. Effects of pregabalin on central sensitization in patients with chronic pancreatitis in a randomized, controlled trial. PloS One. 2012;7:e42096. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0042096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Malesci A, Gaia E, Fioretta A, Bocchia P, Ciravegna G, Cantor P, et al. No effect of longterm treatment with pancreatic extract on recurrent abdominal pain in patients with chronic pancreatitis. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1995;30:392–398. doi: 10.3109/00365529509093296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Halgreen H, Pedersen NT, Worning H. Symptomatic effect of pancreatic enzyme therapy in patients with chronic pancreatitis. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1986;21:104–108. doi: 10.3109/00365528609034631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mossner J, Secknus R, Meyer J, Niederau C, Adler G. Treatment of pain with pancreatic extracts in chronic pancreatitis: results of a prospective placebo-controlled multicentre trial. Digestion. 1992;53:54–66. doi: 10.1159/000200971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vecht J, Symersky T, Lamers CB, Masclee AA. Efficacy of lower than standard doses of pancreatic enzyme supplementation therapy during acid inhibition in patients with pancreatic exocrine insufficiency. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2006;40:721–725. doi: 10.1097/00004836-200609000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Brown A, Hughes M, Tenner S, Banks PA. Does pancreatic enzyme supplementation reduce pain in patients with chronic pancreatitis: a meta-analysis. Am J Gastroenterol. 1997;92:2032–2035. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Winstead NS, Wilcox CM. Clinical trials of pancreatic enzyme replacement for painful chronic pancreatitis – a review. Pancreatology. 2009;9:344–350. doi: 10.1159/000212086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Isaksson G, Ihse I. Pain reduction by an oral pancreatic enzyme preparation in chronic pancreatitis. Dig Dis Sci. 1983;28:97–102. doi: 10.1007/BF01315137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lieb JG, 2nd, Forsmark CE. Review article: pain and chronic pancreatitis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2009;29:706–719. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2009.03931.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fasanella KE, Davis B, Lyons J, Chen Z, Lee KK, Slivka A, et al. Pain in chronic pancreatitis and pancreatic cancer. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2007;36:335–364. doi: 10.1016/j.gtc.2007.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chauhan S, Forsmark CE. Pain management in chronic pancreatitis: a treatment algorithm. Best Pract Res. 2010;24:323–335. doi: 10.1016/j.bpg.2010.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kirk GR, White JS, McKie L, Stevenson M, Young I, Clements WD, et al. Combined antioxidant therapy reduces pain and improves quality of life in chronic pancreatitis. J Gastrointest Surg. 2006;10:499–503. doi: 10.1016/j.gassur.2005.08.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Uden S, Bilton D, Nathan L, Hunt LP, Main C, Braganza JM. Antioxidant therapy for recurrent pancreatitis: placebo-controlled trial. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 1990;4:357–371. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.1990.tb00482.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Uden S, Schofield D, Miller PF, Day JP, Bottiglier T, Braganza JM. Antioxidant therapy for recurrent pancreatitis: biochemical profiles in a placebo-controlled trial. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 1992;6:229–240. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.1992.tb00266.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Malfertheiner P, Mayer D, Büchler M, Dominguez-Munoz JE, Schiefer B, Ditschuneit H. Treatment of pain in chronic pancreatitis by inhibition of pancreatic secretion with octreotide. Gut. 1995;36:450–454. doi: 10.1136/gut.36.3.450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lieb JG, 2nd, Shuster JJ, Theriaque D, Curington C, Cintron M, Toskes PP. A pilot study of octreotide LAR vs. octreotide t.i.d. for pain and quality of life in chronic pancreatitis. JOP. 2009;10:518–522. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shah NS, Makin AJ, Sheen AJ, Siriwardena AK. Quality of life assessment in patients with chronic pancreatitis receiving antioxidant therapy. World J Gastroenterol. 2010;16:4066–4071. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v16.i32.4066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bhardwaj P, Garg PK, Maulik SK, Saraya A, Tandon RK, Acharya SK. A randomized controlled trial of antioxidant supplementation for pain relief in patients with chronic pancreatitis. Gastroenterology. 2009;136:149–159. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.09.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Siriwardena AK, Mason JM, Sheen AJ, Makin AJ, Shah NS. Antioxidant therapy does not reduce pain in patients with chronic pancreatitis: the ANTICIPATE study. Gastroenterology. 2012;143:655–663. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2012.05.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Capurso G, Cocomello L, Benedetto U, Camma C, Delle Fave G. Meta-analysis: the placebo rate of abdominal pain remission in clinical trials of chronic pancreatitis. Pancreas. 2012;41:1125–1131. doi: 10.1097/MPA.0b013e318249ce93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ballegaard S, Christophersen SJ, Dawids SG, Hesse J, Olsen NV. Acupuncture and transcutaneous electric nerve stimulation in the treatment of pain associated with chronic pancreatitis. A randomized study. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1985;20:1249–1254. doi: 10.3109/00365528509089285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kaufman M, Singh G, Das S, Concha-Parra R, Erber J, Micames C, et al. Efficacy of endoscopic ultrasound-guided coeliac plexus block and coeliac plexus neurolysis for managing abdominal pain associated with chronic pancreatitis and pancreatic cancer. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2010;44:127–134. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0b013e3181bb854d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Puli SR, Reddy JB, Bechtold ML, Antillon MR, Brugge WR. EUS-guided coeliac plexus neurolysis for pain due to chronic pancreatitis or pancreatic cancer pain: a meta-analysis and systematic review. Dig Dis Sci. 2009;54:2330–2337. doi: 10.1007/s10620-008-0651-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Santosh D, Lakhtakia S, Gupta R, Reddy DN, Rao GV, Tandan M, et al. Clinical trial: a randomized trial comparing fluoroscopy guided percutaneous technique vs. endoscopic ultrasound guided technique of coeliac plexus block for treatment of pain in chronic pancreatitis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2009;29:979–984. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2009.03963.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Stevens T, Costanzo A, Lopez R, Kapural L, Parsi MA, Vargo JJ. Adding triamcinolone to endoscopic ultrasound-guided coeliac plexus blockade does not reduce pain in patients with chronic pancreatitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;10:186–191. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2011.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.LeBlanc JK, DeWitt J, Johnson C, Okumu W, McGreevy K, Symms M, et al. A prospective randomized trial of one versus two injections during EUS-guided coeliac plexus block for chronic pancreatitis pain. Gastrointest Endosc. 2009;69:835–842. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2008.05.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Madsen P, Hansen E. Coeliac plexus block versus pancreaticogastrostomy for pain in chronic pancreatitis. A controlled randomized trial. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1985;20:1217–1220. doi: 10.3109/00365528509089279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gress F, Schmitt C, Sherman S, Ciaccia D, Ikenberry S, Lehman G. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided coeliac plexus block for managing abdominal pain associated with chronic pancreatitis: a prospective single-centre experience. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96:409–416. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2001.03551.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wong GY, Sakorafas GH, Tsiotos GG, Sarr MG. Palliation of pain in chronic pancreatitis. Use of neural blocks and neurotomy. Surg Clin North Am. 1999;79:873–893. doi: 10.1016/s0039-6109(05)70049-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Malec-Milewska MB, Tarnowski W, Ciesielski AE, Michalik E, Guc MR, Jastrzebski JA. Prospective evaluation of pain control and quality of life in patients with chronic pancreatitis following bilateral thoracoscopic splanchnicectomy. Surg Endosc. 2013 doi: 10.1007/s00464-013-2937-0. Epub 2013/04/11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Baghdadi S, Abbas MH, Albouz F, Ammori BJ. Systematic review of the role of thoracoscopic splanchnicectomy in palliating the pain of patients with chronic pancreatitis. Surg Endosc. 2008;22:580–588. doi: 10.1007/s00464-007-9730-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Nguyen-Tang T, Dumonceau JM. Endoscopic treatment in chronic pancreatitis, timing, duration and type of intervention. Best Pract Res. 2010;24:281–298. doi: 10.1016/j.bpg.2010.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Rosch T, Daniel S, Scholz M, Huibregtse K, Smits M, Schneider T, et al. Endoscopic treatment of chronic pancreatitis: a multicentre study of 1000 patients with longterm follow-up. Endoscopy. 2002;34:765–771. doi: 10.1055/s-2002-34256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wilcox CM, Varadarajulu S. Endoscopic therapy for chronic pancreatitis: an evidence-based review. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2006;8:104–110. doi: 10.1007/s11894-006-0005-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wilcox CM, Lopes TL. A randomized trial comparing endoscopic stenting to a sham procedure for chronic pancreatitis. Clin Trials. 2009;6:455–463. doi: 10.1177/1740774509338230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Farnbacher MJ, Schoen C, Rabenstein T, Benninger J, Hahn EG, Schneider HT. Pancreatic duct stones in chronic pancreatitis: criteria for treatment intensity and success. Gastrointest Endosc. 2002;56:501–506. doi: 10.1067/mge.2002.128162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ohara H, Hoshino M, Hayakawa T, Kamiya Y, Miyaji M, Takeuchi T, et al. Single application extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy is the first choice for patients with pancreatic duct stones. Am J Gastroenterol. 1996;91:1388–1394. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Dumonceau JM, Costamagna G, Tringali A, Vahedi K, Delhaye M, Hittelet A, et al. Treatment for painful calcified chronic pancreatitis: extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy versus endoscopic treatment: a randomized controlled trial. Gut. 2007;56:545–552. doi: 10.1136/gut.2006.096883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Guda NM, Partington S, Freeman ML. Extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy in the management of chronic calcific pancreatitis: a meta-analysis. JOP. 2005;6:6–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Nealon WH, Thompson JC. Progressive loss of pancreatic function in chronic pancreatitis is delayed by main pancreatic duct decompression. A longitudinal prospective analysis of the modified Puestow procedure. Ann Surg. 1993;217:458–466. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199305010-00005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Ihse I, Borch K, Larsson J. Chronic pancreatitis: results of operations for relief of pain. World J Surg. 1990;14:53–58. doi: 10.1007/BF01670546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Warshaw AL, Popp JW, Jr, Schapiro RH. Longterm patency, pancreatic function, and pain relief after lateral pancreaticojejunostomy for chronic pancreatitis. Gastroenterology. 1980;79:289–293. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ahmed Ali U, Nieuwenhuijs VB, van Eijck CH, Gooszen HG, van Dam RM, Busch OR, et al. Clinical outcome in relation to timing of surgery in chronic pancreatitis: a nomogram to predict pain relief. Arch Surg. 2012;147:925–932. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.2012.1094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.van der Gaag NA, van Gulik TM, Busch OR, Sprangers MA, Bruno MJ, Zevenbergen C, et al. Functional and medical outcomes after tailored surgery for pain due to chronic pancreatitis. Ann Surg. 2012;255:763–770. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e31824b7697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Ahmed Ali U, Pahlplatz JM, Nealon WH, van Goor H, Gooszen HG, Boermeester MA. Endoscopic or surgical intervention for painful obstructive chronic pancreatitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;(1) doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD007884.pub2. CD007884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Link G. The treatment of chronic pancreatitis by pancreatostomy: a new operation. Ann Surg. 1911;53:768–782. doi: 10.1097/00000658-191106000-00005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Duval MK., Jr Caudal pancreatico-jejunostomy for chronic relapsing pancreatitis. Ann Surg. 1954;140:775–785. doi: 10.1097/00000658-195412000-00001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Puestow CB, Gillesby WJ. Retrograde surgical drainage of pancreas for chronic relapsing pancreatitis. AMA Arch Surg. 1958;76:898–907. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1958.01280240056009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Partington PF, Rochelle RE. Modified Puestow procedure for retrograde drainage of the pancreatic duct. Ann Surg. 1960;152:1037–1043. doi: 10.1097/00000658-196012000-00015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Greenlee HB, Prinz RA, Aranha GV. Longterm results of side-to-side pancreaticojejunostomy. World J Surg. 1990;14:70–76. doi: 10.1007/BF01670548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Gonzalez M, Herrera MF, Laguna M, Gamino R, Uscanga L, Robles-Diaz G, et al. Pain relief in chronic pancreatitis by pancreatico-jejunostomy. An institutional experience. Arch Med Res. 1997;28:387–390. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Beger HG, Büchler M, Bittner R. The duodenum preserving resection of the head of the pancreas (DPRHP) in patients with chronic pancreatitis and an inflammatory mass in the head. An alternative surgical technique to the Whipple operation. Acta Chir Scand. 1990;156:309–315. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Traverso LW, Longmire WP., Jr Preservation of the pylorus in pancreaticoduodenectomy. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1978;146:959–962. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Friess H, Berberat PO, Wirtz M, Büchler MW. Surgical treatment and longterm follow-up in chronic pancreatitis. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2002;14:971–977. doi: 10.1097/00042737-200209000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Müller MW, Friess H, Beger HG, Kleeff J, Lauterburg B, Glasbrenner B, et al. Gastric emptying following pylorus-preserving Whipple and duodenum-preserving pancreatic head resection in patients with chronic pancreatitis. Am J Surg. 1997;173:257–263. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9610(96)00402-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Jimenez RE, Fernandez-del Castillo C, Rattner DW, Chang Y, Warshaw AL. Outcome of pancreaticoduodenectomy with pylorus preservation or with antrectomy in the treatment of chronic pancreatitis. Ann Surg. 2000;231:293–300. doi: 10.1097/00000658-200003000-00001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Müller MW, Friess H, Kleeff J, Dahmen R, Wagner M, Hinz U, et al. Is there still a role for total pancreatectomy? Ann Surg. 2007;246:966–974. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e31815c2ca3. discussion 974–975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Frey CF, Smith GJ. Description and rationale of a new operation for chronic pancreatitis. Pancreas. 1987;2:701–707. doi: 10.1097/00006676-198711000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Büchler MW, Friess H, Müller MW, Wheatley AM, Beger HG. Randomized trial of duodenum-preserving pancreatic head resection versus pylorus-preserving Whipple in chronic pancreatitis. Am J Surg. 1995;169:65–69. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9610(99)80111-1. discussion 69–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Müller MW, Friess H, Leitzbach S, Michalski CW, Berberat P, Ceyhan GO, et al. Perioperative and follow-up results after central pancreatic head resection (Berne technique) in a consecutive series of patients with chronic pancreatitis. Am J Surg. 2008;196:364–372. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2007.08.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Izbicki JR, Bloechle C, Broering DC, Knoefel WT, Kuechler T, Broelsch CE. Extended drainage versus resection in surgery for chronic pancreatitis: a prospective randomized trial comparing the longitudinal pancreaticojejunostomy combined with local pancreatic head excision with the pylorus-preserving pancreatoduodenectomy. Ann Surg. 1998;228:771–779. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199812000-00008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Müller MW, Friess H, Kleeff J, Hinz U, Wente MN, Paramythiotis D, et al. Middle segmental pancreatic resection: an option to treat benign pancreatic body lesions. Ann Surg. 2006;244:909–918. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000247970.43080.23. discussion 918–920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Friess H, Beger HG, Sulkowski U, Becker H, Hofbauer B, Dennler HJ, et al. Randomized controlled multicentre study of the prevention of complications by octreotide in patients undergoing surgery for chronic pancreatitis. Br J Surg. 1995;82:1270–1273. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800820938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Klempa I, Spatny M, Menzel J, Baca I, Nustede R, Stockmann F, et al. [Pancreatic function and quality of life after resection of the head of the pancreas in chronic pancreatitis. A prospective, randomized comparative study after duodenum preserving resection of the head of the pancreas versus Whipple's operation.] Chirurg. 1995;66:350–359. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Müller MW, Friess H, Martin DJ, Hinz U, Dahmen R, Büchler MW. Longterm follow-up of a randomized clinical trial comparing Beger with pylorus-preserving Whipple procedure for chronic pancreatitis. Br J Surg. 2008;95:350–356. doi: 10.1002/bjs.5960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Farkas G, Leindler L, Daroczi M, Farkas G., Jr Prospective randomized comparison of organ-preserving pancreatic head resection with pylorus-preserving pancreaticoduodenectomy. Langenbecks Arch Surg. 2006;391:338–342. doi: 10.1007/s00423-006-0051-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Strate T, Bachmann K, Busch P, Mann O, Schneider C, Bruhn JP, et al. Resection vs. drainage in treatment of chronic pancreatitis: longterm results of a randomized trial. Gastroenterology. 2008;134:1406–1411. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.02.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Strate T, Taherpour Z, Bloechle C, Mann O, Bruhn JP, Schneider C, et al. Longterm follow-up of a randomized trial comparing the Beger and Frey procedures for patients suffering from chronic pancreatitis. Ann Surg. 2005;241:591–598. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000157268.78543.03. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Izbicki JR, Bloechle C, Knoefel WT, Kuechler T, Binmoeller KF, Broelsch CE. Duodenum-preserving resection of the head of the pancreas in chronic pancreatitis. A prospective, randomized trial. Ann Surg. 1995;221:350–358. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199504000-00004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Köninger J, Seiler CM, Sauerland S, Wente MN, Reidel MA, Müller MW, et al. Duodenum-preserving pancreatic head resection – a randomized controlled trial comparing the original Beger procedure with the Berne modification (ISRCTN No. 50638764) Surgery. 2008;143:490–498. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2007.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Keck T, Adam U, Makowiec F, Riediger H, Wellner U, Tittelbach-Helmrich D, et al. Short- and longterm results of duodenum preservation versus resection for the management of chronic pancreatitis: a prospective, randomized study. Surgery. 2012;152(Suppl. 1):95–102. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2012.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Diener MK, Bruckner T, Contin P, Halloran C, Glanemann M, Schlitt HJ, et al. ChroPac-trial: duodenum-preserving pancreatic head resection versus pancreatoduodenectomy for chronic pancreatitis. Trial protocol of a randomized controlled multicentre trial. Trials. 2010;11:47. doi: 10.1186/1745-6215-11-47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Diener MK, Rahbari NN, Fischer L, Antes G, Büchler MW, Seiler CM. Duodenum-preserving pancreatic head resection versus pancreatoduodenectomy for surgical treatment of chronic pancreatitis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Surg. 2008;247:950–961. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181724ee7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Yin Z, Sun J, Yin D, Wang J. Surgical treatment strategies in chronic pancreatitis: a meta-analysis. Arch Surg. 2012;147:961–968. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.2012.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Ammann RW, Akovbiantz A, Largiader F. Pain relief in chronic pancreatitis with and without surgery. Gastroenterology. 1984;87:746–747. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Bramis K, Gordon-Weeks AN, Friend PJ, Bastin E, Burls A, Silva MA, et al. Systematic review of total pancreatectomy and islet autotransplantation for chronic pancreatitis. Br J Surg. 2012;99:761–766. doi: 10.1002/bjs.8713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Dite P, Ruzicka M, Zboril V, Novotny I. A prospective, randomized trial comparing endoscopic and surgical therapy for chronic pancreatitis. Endoscopy. 2003;35:553–558. doi: 10.1055/s-2003-40237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Cahen DL, Gouma DJ, Nio Y, Rauws EA, Boermeester MA, Busch OR, et al. Endoscopic versus surgical drainage of the pancreatic duct in chronic pancreatitis. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:676–684. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa060610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Cahen DL, Gouma DJ, Laramee P, Nio Y, Rauws EA, Boermeester MA, et al. Longterm outcomes of endoscopic vs. surgical drainage of the pancreatic duct in patients with chronic pancreatitis. Gastroenterology. 2011;141:1690–1695. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.07.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.World Health Organization. Traitement de la douleur cancéreuse. Switzerland: Geneva; 1986. [Google Scholar]