Abstract

Background

There is still some controversy regarding the ethical issues involved in live donor liver transplantation (LDLT) and there is uncertainty on the range of perioperative morbidity and mortality risks that donors will consider acceptable.

Methods

This study analysed donors’ inclinations towards LDLT using decision analysis techniques based on the probability trade-off (PTO) method. Adult individuals with an emotional or biological relationship with a patient affected by end-stage liver disease were enrolled. Of 122 potential candidates, 100 were included in this study.

Results

The vast majority of participants (93%) supported LDLT. The most important factor influencing participants’ decisions was their wish to improve the recipient's chance of living a longer life. Participants chose to become donors if the recipient was required to wait longer than a mean ± standard deviation (SD) of 6 ± 5 months for a cadaveric graft, if the mean ± SD probability of survival was at least 46 ± 30% at 1 month and at least 36 ± 29% at 1 year, and if the recipient's life could be prolonged for a mean ± SD of at least 11 ± 22 months.

Conclusions

Potential donors were risk takers and were willing to donate when given the opportunity. They accepted significant risks, especially if they had a close emotional relationship with the recipient.

Introduction

Liver transplantation (LT) represents the only cure for patients with end-stage liver disease (ESLD).1 Despite efforts to increase the number of donors, patients with ESLD still outnumber the pool of available grafts,2,3 which results in a 7–10% mortality rate among patients on the waiting list.4,5 The discrepancy between organ supply and demand has become the biggest challenge for the transplant community.6 The need for more liver grafts has led clinicians and policymakers to identify strategies that might help to close the gap between demand and supply.7–9 The utilization of grafts from extended criteria donors10,11 has been valuable, but insufficient to provide an adequate number of organs.8 In more recent years, a considerable number of transplant programmes have embraced the use of grafts from patients suffering cardiac death12,13 and from living donors.14,15

Living donor liver transplantation (LDLT) was pioneered in children and small adults. To date, more that 12 000 adult LDLTs have been performed worldwide.16 By promoting LDLT, transplant centres might increase the number of available grafts and reduce the mortality risk of patients on the waiting list.5 Several other benefits are unique to LDLT, such as the short cold ischaemia time, the anticipated good quality of the grafts and the fact that transplant surgery can be performed electively.17,18 However, LDLT is a technically complex procedure19 that absorbs substantial human and financial resources20 and is ethically controversial because of the risks to donors.15,21–25 There is still some disagreement regarding the ethics surrounding LDLT26,27 and there is uncertainty on the range of perioperative morbidity and mortality risks that living liver donors (LLDs) will consider acceptable.28 To investigate some of these issues, a prospective study was designed to assess potential LLDs’ inclinations towards LDLT and to measure the strength of their choices. Secondary aims were to determine the minimal survival benefits to recipients and the perioperative morbidity and mortality risks that potential LLDs will consider acceptable before proceeding with donation.

Materials and methods

Study population and settings

During the period between February 2009 and October 2011, a total of 96 patients with ESLD were referred to the Queen Elizabeth II Medical Centre (Halifax, NS, Canada) for LT. All of these patients were eventually listed for a cadaveric LT after they had been fully assessed. Individuals who were responsible for patients’ daily care or who were emotionally or biologically related to the potential recipients were identified and screened for this study. Of the 122 potential participants, 22 subjects did not consent to participate. A total of 100 individuals satisfied the inclusion criteria and were enrolled. Recruitment took place in the outpatient clinics at a tertiary university centre in which only cadaveric LTs are currently performed.

Human subject protection

This study was approved by the Queen Elizabeth II Health Sciences Centre Institutional Review Board.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Participants were informed that LDLT was not performed at the study institution but was available in other Canadian university hospitals. They were provided with a written questionnaire in order to collect information on their sociodemographic status and past medical history. Inclusion criteria required each potential participant to: have a well-established emotional or biological relationship with a patient referred for LT; to be aged >18 years; to be fit enough to undergo hepatic resection; to be able to provide informed consent, and to be numerically literate. A shortened validated psychometric test29 incorporating numerical computation questions involving basic principles of arithmetic, such as addition, subtraction, multiplication, division and the calculation of percentages, was administered to participants to assess their numeracy. Participants were excluded if they were unable to pass the psychometric test, were aged >60 years, were affected by any major comorbid condition or had an abnormal body mass index (BMI) defined as a BMI of <20 kg/m2 or >30 kg/m2.30,31 Other exclusion criteria were a history of previous hepatic resection or major abdominal surgery, and the presence of a significant visual, hearing or communication impairment.

Participants’ education

Participants were provided a summary table of the potential risks associated with LDLT (Table 1) and were given standardized written and oral information about LDLT. Consent forms and educational materials were written at a sixth-to-eighth-grade reading level as recommended by previous studies.32 Prior to each interview, participants underwent a detailed briefing on the content of the written educational material. After the oral educational session, they were asked if they needed any further clarification; participants who declined that offer were considered to be fully informed of the three significant components of the surgical procedure: (i) the health burden imposed on the donor undergoing hepatic resection; (ii) the possible adverse outcomes and benefits for both the donor and the recipient, and (iii) the likelihood that these outcomes would occur.

Table 1.

Summary of risks and benefits of living donor liver transplantation (LDLT) extracted from scientific articles published in English during the last decades

| Category | LDLT variables | Value | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Donors’ satisfaction | Donors who were satisfied with their decision | 74–100% | 83,89 |

| Donors who would donate again | 73–100% | 73,74,83,89,116 | |

| Donors who would encourage others to donate | 81–92% | 73,83 | |

| Donors’ risks | Donors who developed at least one perioperative complication | 30–50% | 15,58,73,104,107,117–120 |

| Donors who developed multiple complications after surgery | 19–21% | 15,104 | |

| Donors who developed postoperative life-threatening complications | 12–35% | 23 | |

| Donors who developed major complications that required reoperation | 1.5–4.5% | 15,104,117,121 | |

| Donors who developed bile leaks requiring interventions such as percutaneous drainage or endoscopic bile duct stenting | 4–9% | 15 | |

| Donors who developed wound infections | 20% | 15 | |

| Donors who developed postoperative urinary infections | 10% | 15 | |

| Donors who developed incisional hernias | 5–20% | 15,122 | |

| Donors who developed postoperative liver failure requiring liver transplantation | 0.20% | 123 | |

| Donors who experienced postoperative depression that resolved | 2–14% | 116,117,122,124 | |

| Donors’ risk of death | Risk of death for donors as a result of surgical complications | 0.1–0.5% | 15,62,102,123,125 |

| Donors’ operation | Donors in whom an incision was made but who were unable to donate because of an unexpected finding during the operation | 2–4.9% | 15,103,119,126 |

| Donors who needed at least one unit of blood transfused during or after surgery | 1–4.9% | 107,121,127 | |

| Mean donor blood loss during surgery | 500–750 ml | 107 | |

| Donors’ recovery | Mean hospital stay for the donor after surgery | 6–7 days | 73,120–122,127 |

| Time necessary for donors to recover completely from surgery | 2–14 weeks | 73,116 | |

| Donors’ long-term sequelae | Donors who experienced at least one complication after 1 year from donation | 7% | 15 |

| Donors who needed to be readmitted to hospital after being discharged home | 7–11% | 121,122 | |

| Donors who needed to change their job as a consequence of their surgery | 0% | 73 | |

| Donors who encountered financial expenses not fully covered by their insurance | 50% | 116 | |

| Recipients’ benefit | Recipients alive at 1 year after LDLT | 81–94% | 61,93,106 |

Questionnaires

Standardized socioeconomic and demographic questionnaires were administered to all participants. Data on the following variables were collected: age; gender; relationship with the potential recipient; ethnicity; highest level of education; marital status; living situation; employment, and annual household income. The Charlson Self-Administered Comorbidity Questionnaire was also used to assess donors’ health conditions33 and prescriptions of medications regularly taken were recorded.

Identification of relevant variables

During the development of the study protocol, a group of expert hepatobiliary and transplant surgeons was consulted to help identify relevant variables that might influence donors’ inclinations towards LDLT. The following variables were selected: the donor's risk for mortality and morbidity; the donor's risk for long-term complications that might decrease his or her physical capacity; the financial burden imposed by income losses or expenses that the donor or his or her family might face before and after LDLT; the donor's hospital stay and length of time off work or time out from social or familial duties, and, finally, the recipient's expected survival benefit.

Structured interviews

All interviews were held in a quiet and comfortable location in which the participant and interviewer were alone in order to prevent any external pressure that might influence participants’ decisions. The research assistant who administered all the questionnaires and who carried out the interviews (SD) had been trained to perform probability trade-off (PTO) interviews34 and followed a standardized protocol summarized in the following four stages.

Stage 1: the participant was asked whether he or she was willing or unwilling to undergo a partial hepatic resection in order to provide a transplantable graft for a recipient of his or her choice.

Stage 2: the strength of the participant's decision to donate was tested by eliciting his or her willingness to donate when the following characteristics were modified: (i) the degree of emotional or biological closeness between the recipient and the donor; (ii) the cause of the liver disease responsible for hepatic failure in the potential recipient; (iii) the likelihood of disease recurrence after LDLT, and (iv) the age of the recipient.

Stage 3: the importance of variables identified by experts as relevant was measured on a 10-point psychometric visual analogue scale (VAS) (0 = not important; 10 = very important).35

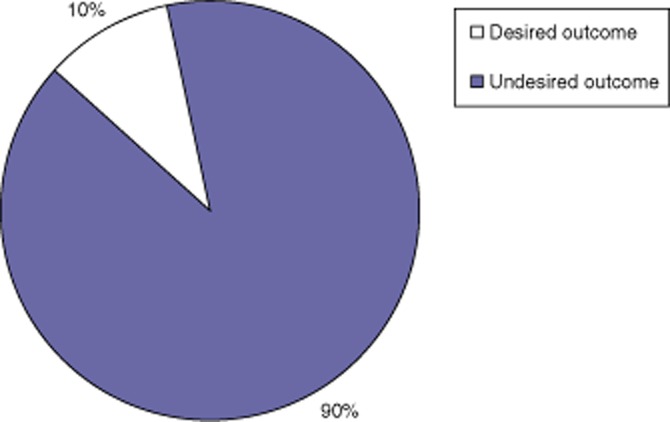

Stage 4: a PTO interview was used to evaluate the strength of the participant's choices. The PTO technique36 is a formal and quantitative decision analysis technique that uses standardized instructions and visual aids. An example of the visual aids used in this study is represented in Fig. 1.37–39

Figure 1.

A pie chart used as a visual aid to illustrate to participants in this study the likelihood of expected outcomes in living donor liver transplantation

Probability trade-off interviews and their rationale

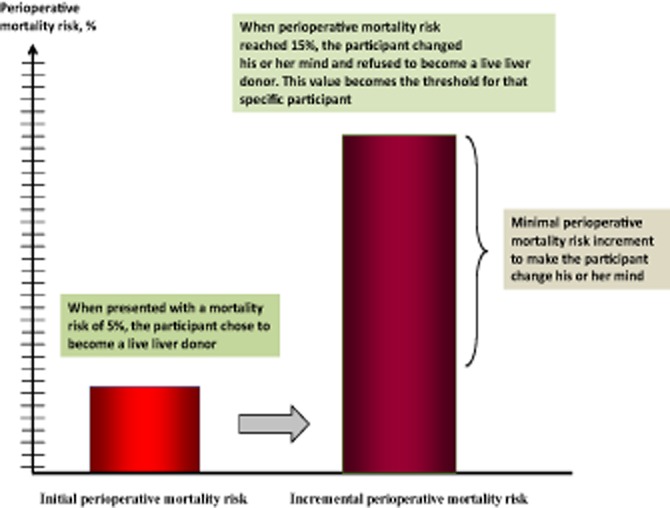

The rationale for using PTO techniques was based on theoretical and practical considerations. Probability trade-off has been shown to capture the complexities of clinical decisions that are made under conditions of uncertainty and has demonstrated high coefficients of test–retest reliability (0.78–0.94).40,41 The method is able to determine how strongly individuals adhere to their treatment preferences34,39 and allows an assessment of potential donor thresholds for donor morbidity and mortality, and recipient survival.42–44 In essence, the participant would declare whether he or she was willing or unwilling to donate after being fully informed of the expected outcomes of LDLT. Then the interviewer would increase or decrease the probability of a variable (e.g. donor morbidity) until the participant changed his or her mind (Fig. 2).34,36,39,45,46 The difference between the expected probability quoted at the beginning of the interview and the probability of the event that would make the participant change his or her mind was measured. The difference between the two probabilities represented a measure of the strength of the participant's preferences.

Figure 2.

Representation of how probability trade-off technique works. The participant was given an initial scenario (left-hand bar) in which the risk for perioperative mortality following living donor liver transplantation was 5%. During the interview, the risk for perioperative mortality was increased by increments of 1% until it reached 15% (right-hand bar). At this level of risk, the participant changed his or her mind and declined to become a live liver donor. In this example, this participant's threshold for perioperative mortality risk was 15% and the maximum risk increment tolerable (threshold value minus initial value) was 10%

Sample size

The sample size required to elicit participants’ preferences using PTO interviews was calculated. Previous studies have shown that on average 20–30 participants are necessary to explore all the important aspects of the research question and to achieve theoretical saturation.47,48 Theoretical saturation is the point at which the results of elicitations become repetitive or when no new themes emerge, and the incremental improvement to the theory is minimal.49 Estimations for this study indicated that 100 consecutive participants would lead to theoretical saturation and would allow an exploration of the hypothesis that donor preferences are associated with an emotional, socioeconomic or familial relationship between the participant and recipient, the recipient's age, the cause of liver failure and the risk for recurrent disease.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive data were reported using estimates of central tendency (means, medians) and spread [standard deviations (SDs), ranges] for continuous data and frequencies and percentages for categorical data. Comparisons between groups were made using cross-tabulation with the appropriate test statistics (Pearson's chi-squared test or Fisher's exact test as appropriate) for categorical variables and the Wilcoxon test for non-normally distributed continuous data. spss Statistics for Windows Version 19.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA) was used for all statistical analyses. All reported P-values are two-sided. P-values of <0.05 are considered to indicate statistical significance.

Results

Baseline participant characteristics

The demographic and socioeconomic characteristics of participants are summarized in Table 2. Demographic characteristics reflected the demographic and socioeconomic statuses of residents of the Canadian provinces of Nova Scotia, Prince Edward Island, Newfoundland and Labrador, and New Brunswick.50 The majority of patients who were referred for LT suffered from cirrhosis secondary to alcoholism (32%) or infection with hepatitis C virus (HCV) (18%) (Table 3).51,52

Table 2.

Participants’ characteristics (n = 100)

| Variable | Values |

|---|---|

| Age, years, mean ± SD | 47.8 ± 12.4 |

| Gender, female, n | 70 |

| Social or familial relationship of participant to recipient, n | |

| Child | 18 |

| Sibling | 11 |

| Spouse/partner | 42 |

| Parent | 4 |

| Niece/nephew | 2 |

| Other | 23 |

| Participants’ ethnicity, n | |

| African-Canadian | 4 |

| First Nation | 5 |

| White | 91 |

| Participants’ highest level of education, n | |

| University | 33 |

| College | 35 |

| High school | 31 |

| Elementary school | 1 |

| Participants’ social status, n | |

| Common law | 15 |

| Married | 63 |

| Single (widow) | 4 |

| Single (divorced or separated) | 6 |

| Single (never married) | 12 |

| Composition of participant's household, n | |

| Alone | 5 |

| Spouse/partner | 77 |

| Parents | 2 |

| Child/children | 6 |

| Friends | 7 |

| Others | 3 |

| Subject's current employment status, n | |

| Home-maker | 5 |

| Unemployed | 6 |

| On disability | 7 |

| Employed | 68 |

| Retired | 12 |

| Student | 2 |

| Subject's current work status, n | |

| Part-time | 24 |

| Full-time | 76 |

| Participants’ employment status, n | |

| Employed by others | 85 |

| Self-employed | 15 |

| Participants’ average number of work hours per week, n | |

| 0–20 | 4 |

| 21–40 | 41 |

| >41 | 25 |

| Participants’ household overall income per year (2010), n | |

| <Can$50 000 | 41 |

| Can$50 000–100 000 | 42 |

| Can$100 001–150 000 | 8 |

| >Can$150 000 | 6 |

| Participant's average income per year (2010), n | |

| <Can$50 000 | 68 |

| Can$50 000–100 000 | 24 |

| Can$100 001–150 000 | 5 |

| >Can$150 000 | 3 |

| Households financially dependent on participant, n | |

| Yes | 87 |

| No | 13 |

| Individuals financially supported by the subject at the time of the interview, n | |

| 4 | 3 |

| 3 | 9 |

| 2 | 22 |

| 1 | 38 |

| 0 | 28 |

| People dependent on participant for care, n | |

| 4 | 3 |

| 3 | 7 |

| 2 | 16 |

| 1 | 36 |

| 0 | 38 |

SD, standard deviation.

Table 3.

Primary aetiology of liver failure in 96 patients referred for liver transplantation

| Aetiology of liver failure | % |

|---|---|

| Alcohol-induced cirrhosis | 33% |

| Viral hepatitis C | 18% |

| Primary biliary cirrhosis | 10% |

| Other causes | 9% |

| Non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) | 8% |

| Primary sclerosing cholangitis | 8% |

| Autoimmune hepatitis | 8% |

| Acute liver failure | 5% |

| Viral hepatitis B | 2% |

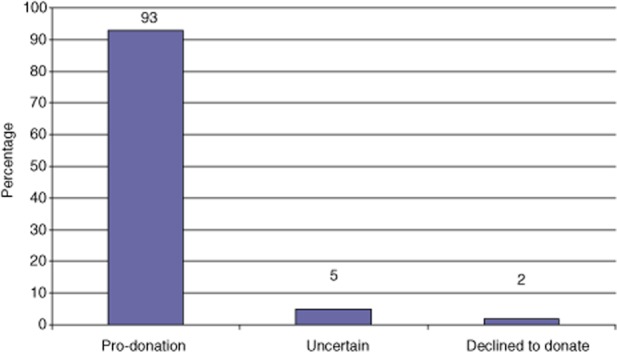

Participants’ willingness to donate

A total of 93% of participants chose to become donors (P = 0.0001) (Fig. 3). No statistically significant difference was noted between the two genders (P = 0.72). The limited number of participants who were ambivalent or refused donation did not allow any investigation of possible prognostic factors associated with a negative response towards living donation.

Figure 3.

Preferences of participants asked if they were willing to undergo partial hepatectomy to donate part of their liver to a potential recipient waiting for a liver transplant (P = 0.0001)

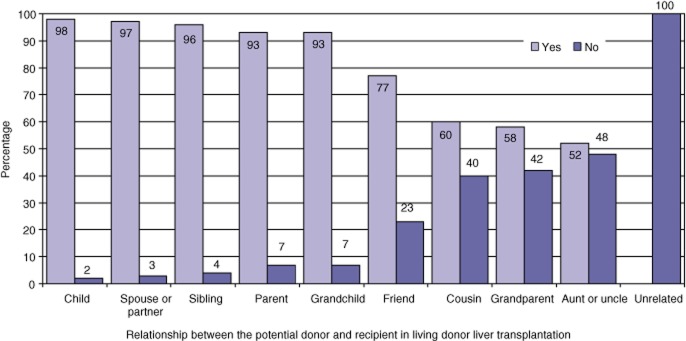

Biological and social relationship with the recipient

The intimacy of the relationship between the participant and patient played an important role in participants’ decisions. As the biological or social relationship between the donor and recipient pair was modified to a more distant association, participants became less inclined to donate (Fig. 4) (P = 0.0001).

Figure 4.

Percentages of participants willing to donate part of their liver in living donor liver transplantation based on the recipient–donor relationship (P = 0.0001)

Recipient characteristics and cause of liver disease

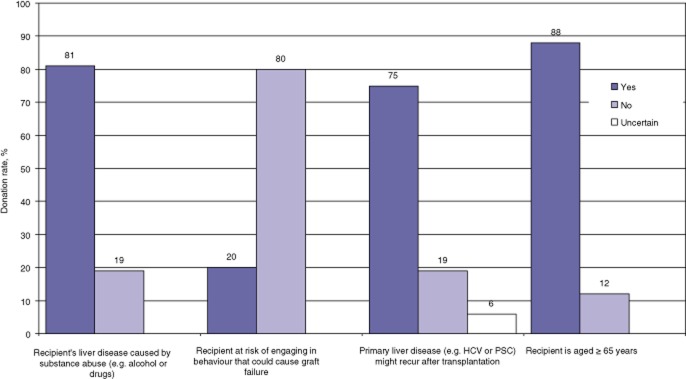

Participants’ decisions on donation also depended on additional factors such as the aetiology of the recipient's liver failure, the recipient's age and the probability that liver failure would reoccur after LT (P = 0.0001) (Fig. 5). Even when the aetiology of ESLD was self-inflicted, such as in alcoholic cirrhosis, 81% of participants were keen to donate if surgery could prolong the recipient's survival. However, their decision was conditional on the existing conduct of the recipient as only 20% were willing to undergo surgery if the recipient continued to indulge in the behaviour that had caused liver failure. Participants were largely willing to donate (75%) even when the primary disease responsible for liver failure was likely to reoccur, such as in HCV-positive recipients, and 88% of participants were willing to donate to individuals aged >65 years.

Figure 5.

Percentages of participants willing to donate part of their liver in living donor liver transplantation based on the primary cause of the liver disease affecting the recipient, the probability that liver failure might reoccur because of the nature of the original disease or self-inflicted hepatotoxicity and the age of the recipient (P = 0.001). HCV, hepatitis C virus; PSC, primary sclerosing cholangitis

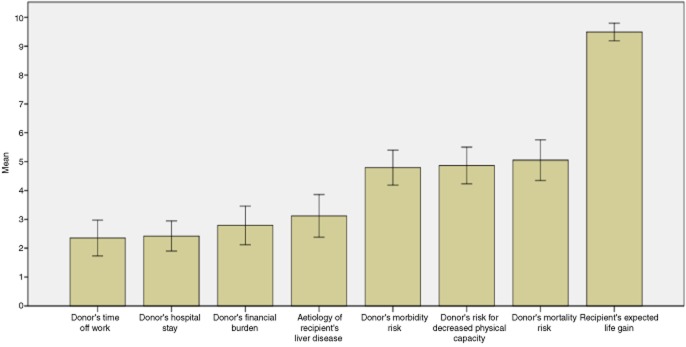

Importance of selected variables

Figure 6 represents the levels of importance attributed by participants to the variables identified as influential by experts. The most dominant variable was the recipient's potential life gain, followed by the donor's morbidity, mortality and loss of his or her own physical capacity. Factors such as the donor's time off work, the length of the donor's hospital stay, the financial burden to the donor, and the aetiology of the liver disease were considered less important (P = 0.001). No statistically significant differences were noted between participants who were self-employed and those who worked in other capacities, or according to the gender or age of participants.

Figure 6.

Importance attributed to some of the variables influencing participant decisions. Values were measured using a visual analogue scale (VAS; 0 = non-important, 10 = extremely important) in 93 participants who were willing to donate. The number of participants who were ambivalent or against donation was too small to allow any meaningful analysis. Error bars show 95% confidence intervals

Risk and benefit thresholds

All participants who expressed the desire to donate underwent PTO interviews to measure the strength of their decisions. Ambivalent participants and subjects who said they would refuse to donate were excluded as they were a group too small to provide any meaningful information for the scope of this study. Thresholds of relevant variables were grouped in three categories. The first category related to the perioperative risks and financial burdens experienced by the participant. The second category concerned the time the recipient would spend on the waiting list for a cadaveric graft and the benefits that he or she would obtain from LDLT. The last category related to the surgical expertise of the transplant team. The mean, range and SD values of the thresholds are summarized in Table 4.

Table 4.

Probability trade-off values for participants’ decision making

| Variable | Minimum | Maximum | Mean | SD | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Donors’ burden | Risk of perioperative complications that would make participants decline to donate | 0.5 | 100 | 64.2 | 35.9 |

| Risk of perioperative mortality that would make participants decline to donate | 0.1 | 100 | 40.4 | 33.6 | |

| Weeks required to make a complete recovery after partial hepatectomy that would make participants decline to donate | 2 | 104 | 26.7 | 23.7 | |

| Financial burden that would make participants decline to donate, Can$, year 2010 | 500 | 5000 | 1868 | 1762 | |

| Number of transfusions of packed red blood cells that would make participants decline to donate | 1 | 10 | 4.3 | 2.9 | |

| Recipient characteristics | Months spent by the recipient on the cadaveric organ waiting list that would make participants decide to donate | 0 | 24 | 6.0 | 5.8 |

| Recipient's survival probability at 1 month that would make participants decide to donate | 0 | 100 | 46.1 | 30.4 | |

| Recipient's survival probability at 1 year that would make participants decide to donate | 0 | 98 | 35.9 | 29.5 | |

| Months of life gained by recipient that would make participants decide to donate | 0 | 156 | 11.4 | 22.1 | |

| Maximum recipient age that would make participants decline donation, years | 40 | 100 | 74.6 | 9.9 | |

| Transplant team experience | Minimum number of living related liver surgeries already performed by the surgical transplant team that would make participants feel comfortable about donating | 0 | 140 | 14.2 | 20.6 |

SD, standard deviation.

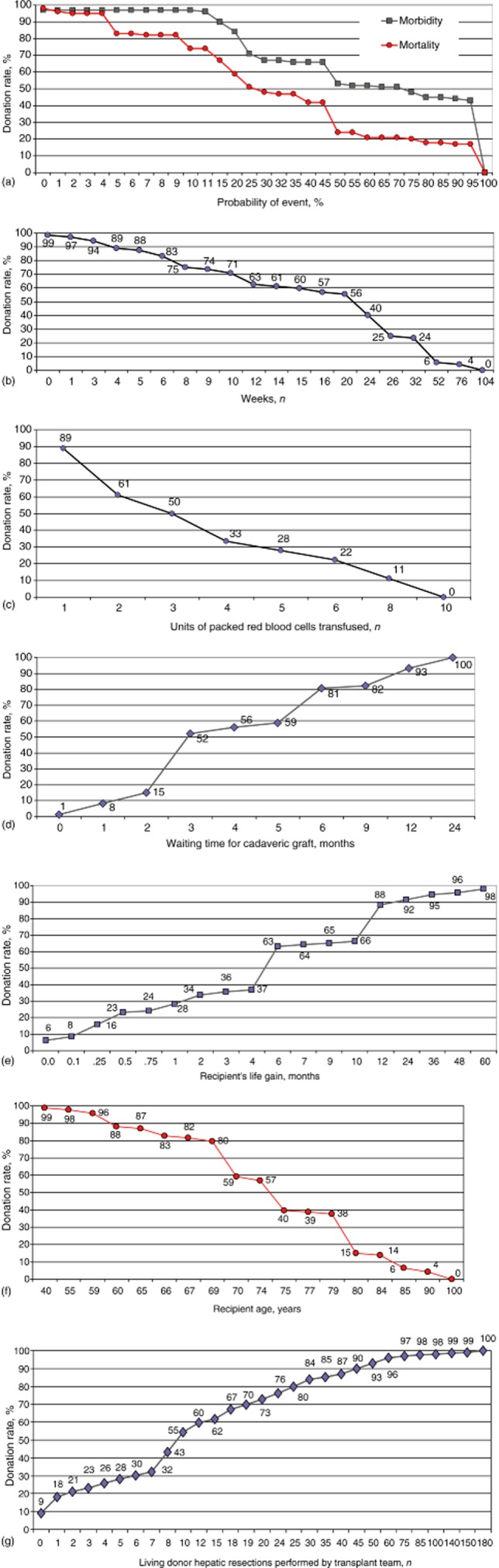

Risk and benefit curves

Curves showing cumulative percentages indicating participants’ preferences are reported in Fig. 7 (a–g). These curves represent participants’ choices under different circumstances and were calculated by varying the potential risks and benefits of LDLT.

Figure 7.

Donors’ inclination to undergo hepatectomy in relation to: (a) operative risks for complications and death; (b) the time required to make a full recovery after surgery; (c) the likelihood of requiring blood transfusions; (d) the length of time spent by the recipient on the waiting list; (e) the recipient's survival benefit; (f) the recipient's age, and (g) the transplant team's surgical expertise

Figure 7a represents participants’ inclinations to donate according to the potential risks of surgery. Half (50%) of participants declined surgery when the risk for complications was ≥75% [interquartile range (IQR): 25–100%] and the risk for death was ≥30% (IQR: 10–50%). Half (50%) of participants refused surgery when the expected time necessary for their recovery was ≥24 weeks (IQR: 8–30 weeks) and the median quantity of transfusion required amounted to ≥3 units of packed red blood cells (IQR: 2–6 units) (Fig. 7b, c). Half (50%) of participants declined LDLT when the recipient's median time on the waiting list for a cadaveric LT was ≤3 months (IQR: 3–6 months), when the median survival benefit to the recipient was ≤6 months (IQR: 1–12 months) and when the median age of the recipient was ≥75 years (IQR: 70–80 years) (Fig. 7d–f). With regard to the technical experience of the surgical team, 50% of participants felt they would feel comfortable about donating only when transplant surgeons had already performed at least 10 LDLTs (IQR: 5–25 LDLTs) (Fig. 7g).

Discussion

Over the last decades, outcomes of patients receiving LDLTs have improved to the point that53 they are now comparable to cadaveric grafts.54–61 The small but not negligible risks to donors make LDLT controversial from a purely ethical point of view.21,60,62 Previous studies have addressed how members of society,26,63–69 health care providers27,66,68,70,71 and patients on the waiting list72 feel about LDLT. A handful of studies have examined how living donors felt about LDLT after they had undergone surgery.48,55,73–75 Although listening to the voices of donors is paramount, recall bias played a role in donors’ responses in these studies because their decisions had already been made and they had survived surgery.76 It is not surprising that the vast majority of the donors recruited in these studies supported LDLT because their donations may have saved family members or friends.77–80 In reality, however, choices must be made in the face of uncertainty and the risks for undesirable events must be carefully weighted.81 The ethical dimension of equipoise mandates that the risk to the donor must balance the benefit to the recipient,82 but it is still unclear who should make the ultimate decision in support or rejection of the practice of LDLT. Because no previous studies have investigated donors’ preferences prior to undergoing surgery, the present authors recruited a pool of potential donors and elicited their inclinations and measured the strength of their decisions.34,39–44

The primary result of the present study showed that the majority of participants desired to become donors. Contrary to other studies, in which ambivalent feelings towards LDLT were measured in 20–65% of subjects,67,83–85 only 5% of participants were ambivalent and 2% declined surgery. The percentage of participants in the present study who were ambivalent about or opposed to becoming donors is considerably lower than the ranges previously described by others.67,83–85 This may reflect the fact that, although participants satisfied the criteria required of a donor, they knew that opportunities to donate were not available at the study transplant centre, although they were informed that these were available in other Canadian transplant centres. Because the study institution did not offer any opportunity to participate in LDLT, study subjects may have felt that their decisions did not have any tangible implications and carried no real risks to their health. Another possible explanation is that the vast majority of participants were spouses, children and siblings of patients in need of an LT. These participants may have been more motivated than other groups because of the strength of their emotional relationships with the potential recipients or because they felt guilty about or accountable for recipients’ conditions.86,87 When participants were asked for the rationale for their decision to donate, the desire to prolong the recipient's life emerged as the main motive, even if the benefits to the recipient were moderate.88 The donor–recipient relationship played an important role because the percentage of participants willing to donate declined when the relationship with the recipient became more distant.46 In general, potential donors were ready to make a great deal of self-sacrifice as they put the benefits to the recipient far ahead of their own risks.86,87 Participants were willing to donate even when the potential recipient was elderly or affected by liver failure that might reoccur. They also had high thresholds for changing their minds when they were told that surgery might imply the need for several blood transfusions, the need to take considerable time off work, a long period of convalescence, relatively high financial burdens and, above all, high morbidity and mortality. In a manner similar to that observed by Papachristou et al.,48 the present study subjects also gave the impression that they desired to keep the recipient alive at any cost, without fully appreciating the very high personal risks inherent in the fulfilling of this wish. However, donors’ willingness to donate was not unconditional because no donors were willing to take part in donation to a stranger and the rate of willingness to donate decreased when the potential recipient continued to harm his or her liver or was elderly.

Strengths of this study

The present study has several strengths. To the present authors’ knowledge, this is the first investigation designed to measure risk thresholds in potential donors in a prospective and systematic way. Participants were selected only if they satisfied very stringent inclusion criteria that were comparable with the criteria used by most transplant centres when selecting potential LLDs. This strategy represented an attempt to control for some of the socioeconomic and emotional characteristics that might influence decision making and preferences. In addition, the fact that participants were not able to donate because LDLT was not offered at the study centre was in some ways advantageous because participants’ decisions were not subject to the psychological or emotional pressure88 that occurs when donors are evaluated for LDLT in centres at which this procedure is performed. Another of the most important aspects of the present study was that participants were fully informed about the risks and benefits associated with LDLT.89 This required the input of a dedicated person and took several hours and therefore is not feasible in most busy clinical settings. Because the present study adhered to a well-defined study protocol, the authors are confident that all possible measures were taken to make participants very well informed and that there are no other significant measures that could have improved the quality of participants’ education on LDLT. Other strong points of this study include the method (PTO) used to elicit preferences in a systematic and impartial way.

Limitations of this study

This study has several shortcomings. In the majority of decision analysis models, it is assumed that individuals make decisions based only on rational thinking.90 This may not be true in health care as several studies have shown that decision making can be led by emotions more than it is by a lucid cognitive process,90–92 and that decisions are influenced by cultural and social characteristics.48,73,74,93 Unlike members of the transplant team, who have experience with the complications of the procedure, potential donors have a more superficial understanding based on descriptions of the probabilities of events. Volk et al.94 speculated that donors may assume that LDLT will benefit the recipient because it is being offered by the medical community, as other authors have indicated,95,96 and many donors appear to make decisions even before they know the risks of the operation.48,75,84,91,93,94,97

Another important limitation concerned the possibility that potential donors might not have fully understood the risks associated with donation27,56,93 as the thresholds for the risks for morbidity and mortality in this study were outside the range considered sensible by any health care provider. Although the present study was carried out following a standardized interview process and the numerical literacy of all participants was tested, participant preferences were measured only once. Therefore it is reasonable to think that their opinions might change over time98,99 and that donors might later be unwilling to accept that level of risk as it is well known that some LDLT donors change their commitment just before their operation. Therefore, further research should clarify the actual risk thresholds of donors closer to the time of surgery to allow for the meaningful generalization of the present findings.

Clinical implications

The results of this study may have several practical implications because individuals who have an emotional attachment to someone who is suffering from ESLD are very interested in LDLT. Therefore, LDLT should be openly discussed with patients and their families and friends as the human cost of an insufficient supply of cadaveric grafts remains high.4,100 During the last decade, the number of adult LDLTs performed in North America has declined. This may reflect the occurrence of a donor death in New York in 2002, but it may also reflect the introduction of the Model for End-stage Liver Disease (MELD) scoring system, which gives patients with hepatocellular carcinoma, formerly the most common recipients of LDLTs, priority in the use of cadaveric livers.59,101–104 The combination of these factors may explain why LDLTs currently account for <5% of all LTs in the USA.105,106

Live donor morbidity and mortality are inevitable,107 but nowadays the mortality risk is estimated to be as low as 0.2–0.5%108,109 and 5-year recipient survival exceeds 70%.85 In comparison, participants in the present study indicated they would accept a 70% risk for morbidity, a 30% risk for mortality, and a recipient life gain of only 6 months. This disparity between the actual risks reported in the literature and those considered acceptable by participants in the present study brings to attention two key issues. Firstly, the risks of LDLT are currently lower than the risks donors are willing to accept and, secondly, donors are willing to accept a greater level of risk than are clinicians.27

Because of the discrepancy between the views of clinicians and potential donors, health care providers should recognize that they should not make decisions on LDLTs alone. The information that LDLT can save selected patients with ESLD or hepatocellular carcinoma should be shared with patients and their families and friends, although the procedure carries some risks that cannot be minimized.88 The present authors believe that shared decision making satisfies all of the parties involved88,110–114 and that, regardless of recipient outcomes, there are benefits to be derived by potential donors from their active involvement in some of the decision making that can reduce their anxiety and regret about being unable to help a loved person in need.115 Nevertheless, the present authors share the concerns raised by Malago et al.62 over the fact that, since 1998, the potential benefits of LDLT have encouraged the rapid and uncoordinated worldwide development of programmes offering the procedure. Therefore, health professionals should maintain a central role in guiding, informing, counselling and warning all parties of the risks and benefits associated with LDLT. This is to guarantee that the right of healthy individuals to make choices regarding the act of donation89 is fulfilled only in centres that have demonstrated excellent outcomes and have the necessary resources.62

Conclusions

The present study offers a snapshot of the opinions of potential LLDs on LDLT and the risks that come with this procedure. The study findings indicate that potential donors are risk takers and that 93% of subjects appeared to be interested in donating. The most important reason for donating is to keep a loved person alive, especially if there is a very close emotional relationship between the recipient and donor, even in the presence of significant risk for perioperative morbidity and mortality.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by a Seed Grant of Can$50 000 provided by the Department of Surgery, Dalhousie University to the senior author. In addition, the authors thank Dr Mark Walsh, Dr Kevork Peltekian, Dr Ian Alwayn, Dr Marie Lareya, Mary Jane McNeal, Catherine Guimont, Geri Hirsh and Carla Burgess for their assistance during the recruitment of participants, and Sabrina Poirier for her secretarial support.

Conflicts of interest

None declared.

References

- 1.Kim WR, Brown RS, Jr, Terrault NA, El-Serag H. Burden of liver disease in the United States: summary of a workshop. Hepatology. 2002;36:227–242. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2002.34734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gill JS, Klarenbach S, Cole E, Shemie SD. Deceased organ donation in Canada: an opportunity to heal a fractured system. Am J Transplant. 2008;8:1580–1587. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2008.02314.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Scientific Registry of Transplant Recipients/Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network. SRTR/OPTN Annual Report. 2009 Available at http://www.ustransplant.org/annual_reports/current/ (last accessed 23 July 2011)

- 4.Molinari M, Renfrew PD, Petrie NM, De Coutere S, Abdolell M. Clinical epidemiological analysis of the mortality rate of liver transplant candidates living in rural areas. Transpl Int. 2011;24:292–299. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-2277.2010.01200.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Barshes NR, Horwitz IB, Franzini L, Vierling JM, Goss JA. Waitlist mortality decreases with increased use of extended criteria donor liver grafts at adult liver transplant centres. Am J Transplant. 2007;7:1265–1270. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2007.01758.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wertheim JA, Petrowsky H, Saab S, Kupiec-Weglinski JW, Busuttil RW. Major challenges limiting liver transplantation in the United States. Am J Transplant. 2011;11:1773–1784. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2011.03587.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Metzger RA, Delmonico FL, Feng S, Port FK, Wynn JJ, Merion RM. Expanded criteria donors for kidney transplantation. Am J Transplant. 2003;3(Suppl. 4):114–125. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-6143.3.s4.11.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Durand F, Renz JF, Alkofer B, Burra P, Clavien PA, Porte RJ, et al. Report of the Paris consensus meeting on expanded criteria donors in liver transplantation. Liver Transpl. 2008;14:1694–1707. doi: 10.1002/lt.21668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Foster R, Zimmerman M, Trotter JF. Expanding donor options: marginal, living, and split donors. Clin Liver Dis. 2007;11:417–429. doi: 10.1016/j.cld.2007.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gruttadauria S, Pagano D, Echeverri GJ, Cintorino D, Spada M, Gridelli BG. How to face organ shortage in liver transplantation in an area with low rate of deceased donation. Updat Surg. 2010;62:149–152. doi: 10.1007/s13304-010-0030-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Briceno J, Ciria R, de la Mata M, Rufian S, Lopez-Cillero P. Prediction of graft dysfunction based on extended criteria donors in the Model for End-stage Liver Disease score era. Transplantation. 2010;90:530–539. doi: 10.1097/TP.0b013e3181e86b11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Uemura T, Ramprasad V, Hollenbeak CS, Bezinover D, Kadry Z. Liver transplantation for hepatitis C from donation after cardiac death donors: an analysis of OPTN/UNOS data. Am J Transplant. 2012;12:984–991. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2011.03899.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Deshpande R, Heaton N. Can non-heart-beating donors replace cadaveric heart-beating liver donors? J Hepatol. 2006;45:499–503. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2006.07.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Abecassis M, Adams M, Adams P, Arnold RM, Atkins CR, Barr ML, et al. Consensus statement on the live organ donor. JAMA. 2000;284:2919–2926. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.22.2919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Abecassis MM, Fisher RA, Olthoff KM, Freise CE, Rodrigo DR, Samstein B, et al. Complications of living donor hepatic lobectomy – a comprehensive report. Am J Transplant. 2012;12:1208–1217. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2011.03972.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nadalin S, Bockhorn M, Malago M, Valentin-Gamazo C, Frilling A, Broelsch CE. Living donor liver transplantation. HPB. 2006;8:10–21. doi: 10.1080/13651820500465626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Florman S, Miller CM. Live donor liver transplantation. Liver Transpl. 2006;12:499–510. doi: 10.1002/lt.20754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lonze BE, Parsikia A, Feyssa EL, Khanmoradi K, Araya VR, Zaki RF, et al. Operative start times and complications after liver transplantation. Am J Transplant. 2010;10:1842–1849. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2010.03177.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cattral MS, Molinari M, Vollmer CM, Jr, McGilvray I, Wei A, Walsh M, et al. Living-donor right hepatectomy with or without inclusion of middle hepatic vein: comparison of morbidity and outcome in 56 patients. Am J Transplant. 2004;4:751–757. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2004.00405.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Trotter JF, Campsen J, Bak T, Wachs M, Forman L, Everson G, et al. Outcomes of donor evaluations for adult-to-adult right hepatic lobe living donor liver transplantation. Am J Transplant. 2006;6:1882–1889. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2006.01322.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cronin DC, 2nd, Millis JM, Siegler M. Transplantation of liver grafts from living donors into adults – too much, too soon. N Engl J Med. 2001;344:1633–1637. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200105243442112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Beavers KL, Sandler RS, Shrestha R. Donor morbidity associated with right lobectomy for living donor liver transplantation to adult recipients: a systematic review. Liver Transpl. 2002;8:110–117. doi: 10.1053/jlts.2002.31315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Freise CE, Gillespie BW, Koffron AJ, Lok AS, Pruett TL, Emond JC, et al. Recipient morbidity after living and deceased donor liver transplantation: findings from the A2ALL Retrospective Cohort Study. Am J Transplant. 2008;8:2569–2579. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2008.02440.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Simpson MA, Pomfret EA. Searching for the optimal living liver donor psychosocial evaluation. Am J Transplant. 2012;12:7–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2011.03806.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.D′Alessandro AM, Peltier JW, Dahl AJ. The impact of social, cognitive and attitudinal dimensions on college students′ support for organ donation. Am J Transplant. 2012;12:152–161. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2011.03783.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cotler SJ, McNutt R, Patil R, Banaad-Omiotek G, Morrissey M, Abrams R, et al. Adult living donor liver transplantation: preferences about donation outside the medical community. Liver Transpl. 2001;7:335–340. doi: 10.1053/jlts.2001.22755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cotler SJ, Cotler S, Gambera M, Benedetti E, Jensen DM, Testa G. Adult living donor liver transplantation: perspectives from 100 liver transplant surgeons. Liver Transpl. 2003;9:637–644. doi: 10.1053/jlts.2003.50109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.DiMartini A, Cruz RJ, Jr, Dew MA, Fitzgerald MG, Chiappetta L, Myaskovsky L, et al. Motives and decision making of potential living liver donors: comparisons between gender, relationships and ambivalence. Am J Transplant. 2012;12:136–151. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2011.03805.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Numerical computation – practice test 1. Available at http://www.psychometric-success.com (last accessed 1 January 2009)

- 30.Sorensen TI, Virtue S, Vidal-Puig A. Obesity as a clinical and public health problem: is there a need for a new definition based on lipotoxicity effects? Biochim Biophys Acta. 2010;1801:400–404. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2009.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Marsh JW, Gray E, Ness R, Starzl TE. Complications of right lobe living donor liver transplantation. J Hepatol. 2009;51:715–724. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2009.04.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gordon EJ, Bergeron A, McNatt G, Friedewald J, Abecassis MM, Wolf MS. Are informed consent forms for organ transplantation and donation too difficult to read? Clin Transplant. 2012;26:275–283. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0012.2011.01480.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40:373–383. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(87)90171-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Llewellyn-Thomas HA. Investigating patients’ preferences for different treatment options. Can J Nurs Res. 1997;29:45–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Paul-Dauphin A, Guillemin F, Virion JM, Briancon S. Bias and precision in visual analogue scales: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Epidemiol. 1999;150:1117–1127. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a009937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Llewellyn-Thomas H, Sutherland HJ, Tibshirani R, Ciampi A, Till JE, Boyd NF. The measurement of patients’ values in medicine. Med Decis Making. 1982;2:449–462. doi: 10.1177/0272989X8200200407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kiebert GM, Stiggelbout AM, Leer JW, Kievit J, de Haes HJ. Test–retest reliabilities of two treatment-preference instruments in measuring utilities. Med Decis Making. 1993;13:133–140. doi: 10.1177/0272989X9301300207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wilkins EG, Lowery JC, Copeland LA, Goldfarb SL, Wren PA, Janz NK. Impact of an educational video on patient decision making in early breast cancer treatment. Med Decis Making. 2006;26:589–598. doi: 10.1177/0272989X06295355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Llewellyn-Thomas HA, Naylor CD, O'Connor AM. Eliciting patient preferences. Ann Intern Med. 1993;118:76. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-118-1-199301010-00017. author reply: 77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Street RL, Jr, Voigt B, Geyer C, Jr, Manning T, Swanson GP. Increasing patient involvement in choosing treatment for early breast cancer. Cancer. 1995;76:2275–2285. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19951201)76:11<2275::aid-cncr2820761115>3.0.co;2-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yates JF, Patalano A, editors. Decision Making and Aging. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum; 1999. pp. 31–54. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Woolf SH. Shared decision-making: the case for letting patients decide which choice is best. J Fam Pract. 1997;45:205–208. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Drake RE, Deegan PE. Shared decision making is an ethical imperative. Psychiatr Serv. 2009;60:1007. doi: 10.1176/ps.2009.60.8.1007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Drake RE, Cimpean D, Torrey WC. Shared decision making in mental health: prospects for personalized medicine. Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 2009;11:455–463. doi: 10.31887/DCNS.2009.11.4/redrake. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Llewellyn-Thomas HA. Patients’ health care decision making: a framework for descriptive and experimental investigations. Med Decis Making. 1995;15:101–106. doi: 10.1177/0272989X9501500201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Llewellyn-Thomas HA, Williams JI, Levy L, Naylor CD. Using a trade-off technique to assess patients’ treatment preferences for benign prostatic hyperplasia. Med Decis Making. 1996;16:262–282. doi: 10.1177/0272989X9601600311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Eng J. Sample size estimation: how many individuals should be studied? Radiology. 2003;227:309–313. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2272012051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Papachristou C, Walter M, Dietrich K, Danzer G, Klupp J, Klapp BF, et al. Motivation for living-donor liver transplantation from the donor's perspective: an in-depth qualitative research study. Transplantation. 2004;78:1506–1514. doi: 10.1097/01.tp.0000142620.08431.26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Fontanella BJ, Luchesi BM, Saidel MG, Ricas J, Turato ER, Melo DG. Sampling in qualitative research: a proposal for procedures to detect theoretical saturation. Cad Saude Publica. 2011;27:388–394. doi: 10.1590/s0102-311x2011000200020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Statistics Canada. 2013. Available at http://www.statcan.gc.ca/start-debut-eng.html (last accessed 16 February 2013)

- 51.Lai JC, Roberts JP, Vittinghoff E, Terrault NA, Feng S. Patient, centre and geographic characteristics of nationally placed livers. Am J Transplant. 2012;12:947–953. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2011.03962.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Gillespie BW, Merion RM, Ortiz-Rios E, Tong L, Shaked A, Brown RS, et al. Database comparison of the adult-to-adult living donor liver transplantation cohort study (A2ALL) and the SRTR US Transplant Registry. Am J Transplant. 2010;10:1621–1633. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2010.03039.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Marcos A, Fisher RA, Ham JM, Shiffman ML, Sanyal AJ, Luketic VA, et al. Right lobe living donor liver transplantation. Transplantation. 1999;68:798–803. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199909270-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Trotter JF, Wachs M, Everson GT, Kam I. Adult-to-adult transplantation of the right hepatic lobe from a living donor. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:1074–1082. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra011629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Parikh ND, Ladner D, Abecassis M, Butt Z. Quality of life for donors after living donor liver transplantation: a review of the literature. Liver Transpl. 2010;16:1352–1358. doi: 10.1002/lt.22181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Fujita M, Akabayashi A, Slingsby BT, Kosugi S, Fujimoto Y, Tanaka K. A model of donors’ decision-making in adult-to-adult living donor liver transplantation in Japan: having no choice. Liver Transpl. 2006;12:768–774. doi: 10.1002/lt.20689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lo CM, Fan ST, Liu CL, Wei WI, Lo RJ, Lai CL, et al. Adult-to-adult living donor liver transplantation using extended right lobe grafts. Ann Surg. 1997;226:261–269. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199709000-00005. discussion 269–270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Umeshita K, Fujiwara K, Kiyosawa K, Makuuchi M, Satomi S, Sugimachi K, et al. Operative morbidity of living liver donors in Japan. Lancet. 2003;362:687–690. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)14230-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Akabayashi A, Slingsby BT, Fujita M. The first donor death after living-related liver transplantation in Japan. Transplantation. 2004;77:634. doi: 10.1097/01.tp.0000115342.98226.7c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Surman OS. The ethics of partial-liver donation. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:1038. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200204043461402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Olthoff KM, Merion RM, Ghobrial RM, Abecassis MM, Fair JH, Fisher RA, et al. Outcomes of 385 adult-to-adult living donor liver transplant recipients: a report from the A2ALL Consortium. Ann Surg. 2005;242:314–323. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000179646.37145.ef. Discussion 23–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Malago M, Testa G, Marcos A, Fung JJ, Siegler M, Cronin DC, et al. Ethical considerations and rationale of adult-to-adult living donor liver transplantation. Liver Transpl. 2001;7:921–927. doi: 10.1053/jlts.2001.28301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Simmons RG, Marine SK, Simmons R, editors. Gift of Life: The Effect of Organ Transplantation on Individual, Family, and Societal Dynamics. New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction Books; 1987. pp. 338–375. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Marcos A. Adult living donor liver transplantation: preferences about donation outside the medical community. Liver Transpl. 2001;7:341–342. doi: 10.1053/jlts.2001.23008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Martinez-Alarcon L, Rios A, Lopez MJ, Sanchez J, Lopez-Navas A, Parrilla P, et al. The attitude of future journalists toward living donation. Transplant Proc. 2009;41:2055–2059. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2009.06.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Rios A, Ramirez P, Rodriguez MM, Martinez L, Rodriguez JM, Galindo PJ, et al. Attitude of hospital personnel faced with living liver donation in a Spanish centre with a living donor liver transplant programme. Liver Transpl. 2007;13:1049–1056. doi: 10.1002/lt.21226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Popp FC, Eggert N, Hoy L, Lang SA, Obed A, Piso P, et al. Who is willing to take the risk? Assessing the readiness for living liver donation in the general German population. J Med Ethics. 2006;32:389–894. doi: 10.1136/jme.2005.013474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Castaing D, Azoulay D, Danet C, Thoraval L, Tanguy Des Deserts C, Saliba F, et al. Medical community preferences concerning adult living related donor liver transplantation. Gastroenterol Clin Biol. 2006;30:183–187. doi: 10.1016/s0399-8320(06)73151-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Neuberger J, Price D. Role of living liver donation in the United Kingdom. BMJ. 2003;327:676–679. doi: 10.1136/bmj.327.7416.676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Rios A, Conesa C, Ramirez P, Galindo PJ, Rodriguez JM, Rodriguez MM, et al. Attitudes of resident doctors toward different types of organ donation in a Spanish transplant hospital. Transplant Proc. 2006;38:869–874. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2006.02.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Fujita M, Matsui K, Monden M, Akabayashi A. Attitudes of medical professionals and transplantation facilities toward living-donor liver transplantation in Japan. Transplant Proc. 2010;42:1453–1459. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2009.12.072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Martinez-Alarcon L, Rios A, Conesa C, Alcaraz J, Gonzalez MJ, Montoya M, et al. Attitude toward living related donation of patients on the waiting list for a deceased donor solid organ transplant. Transplant Proc. 2005;37:3614–3617. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2005.08.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Karliova M, Malago M, Valentin-Gamazo C, Reimer J, Treichel U, Franke GH, et al. Living-related liver transplantation from the view of the donor: a 1-year follow-up survey. Transplantation. 2002;73:1799–1804. doi: 10.1097/00007890-200206150-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Cabello CC, Smolowitz J. Roller coaster marathon: being a live liver donor. Prog Transplant. 2008;18:185–191. doi: 10.1177/152692480801800307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Kim-Schluger L, Florman SS, Schiano T, O'Rourke M, Gagliardi R, Drooker M, et al. Quality of life after lobectomy for adult liver transplantation. Transplantation. 2002;73:1593–1597. doi: 10.1097/00007890-200205270-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Kantner J, Lindsay DS. Response bias in recognition memory as a cognitive trait. Mem Cognit. 2012;40:1163–1177. doi: 10.3758/s13421-012-0226-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Togashi JSY, Tamura S, Yamashiki N, Kaneko J, Aoki T, Hasegawa K, et al. Donor quality of life after living donor liver transplantation: a prospective study. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci. 2011;18:263–267. doi: 10.1007/s00534-010-0340-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Chan SC, Liu C, Lo CM, Lam BK, Lee EW, Fan ST. Donor quality of life before and after adult-to-adult right liver live donor liver transplantation. Liver Transpl. 2006;12:1529–1536. doi: 10.1002/lt.20897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Crowley-Matoka M, Siegler M, Cronin DC. Longterm quality of life issues among adult-to-paediatric living liver donors: a qualitative exploration. Am J Transplant. 2004;4:744–750. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2004.00377.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Sotiropoulos GC, Radtke A, Molmenti EP, Schroeder T, Baba HA, Frilling A, et al. Longterm follow-up after right hepatectomy for adult living donation and attitudes toward the procedure. Ann Surg. 2011;254:694–700. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e31823594ae. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Torrance GW. Toward a utility theory foundation for health status index models. Health Serv Res. 1976;11:349–369. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Concejero AM, Chen C. Ethical perspectives on living donor organ transplantation in Asia. Liver Transpl. 2009;15:1658–1661. doi: 10.1002/lt.21930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Rudow DL, Chariton M, Sanchez C, Chang S, Serur D, Brown RS., Jr Kidney and liver living donors: a comparison of experiences. Prog Transplant. 2005;15:185–191. doi: 10.1177/152692480501500213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Kuczewski MG, Marshall P. The decision dynamics of clinical research: the context and process of informed consent. Med Care. 2002;40(9 Suppl):V45–V54. doi: 10.1097/01.MLR.0000023955.04138.AF. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Miller CM. Ethical dimensions of living donation: experience with living liver donation. Transplant Rev (Orlando) 2008;22:206–209. doi: 10.1016/j.trre.2008.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Olbrish ME, Benedict SM, Cropsey KL, Ashworth A, Fischer RA. Characteristics of persons seeking to become adult–adult living liver donors: a single US centre experience with 150 donor candidates. In: Weimar W, Bos M, van Busschbach JJ, editors. Organ Transplantation: Ethical, Legal and Psychosocial Aspects Towards A Common European Policy. Lengerich: PABST Science Publishers; 2008. pp. 261–269. [Google Scholar]

- 87.Goldman LS. Liver transplantation using living donors. Preliminary donor psychiatric outcomes. Psychosomatics. 1993;34:235–240. doi: 10.1016/S0033-3182(93)71885-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.White SA, Pollard SG. Living donor liver transplantation. Br J Surg. 2005;92:262–263. doi: 10.1002/bjs.4939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Diaz GC, Renz JF, Mudge C, Roberts JP, Ascher NL, Emond JC, et al. Donor health assessment after living-donor liver transplantation. Ann Surg. 2002;236:120–126. doi: 10.1097/00000658-200207000-00018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Feather NT. An expectancy-value model of information-seeking behaviour. Psychol Rev. 1967;74:342–360. doi: 10.1037/h0024879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Naylor CD, Llewellyn-Thomas HA. Utilities and preferences for health states: time for a pragmatic approach? J Health Serv Res Policy. 1998;3:129–131. doi: 10.1177/135581969800300301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Silverman WA, Altman DG. Patients’ preferences and randomized trials. Lancet. 1996;347:171–174. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(96)90347-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Gordon EJ, Daud A, Caicedo JC, Cameron KA, Jay C, Fryer J, et al. Informed consent and decision-making about adult-to-adult living donor liver transplantation: a systematic review of empirical research. Transplantation. 2011;92:1285–1296. doi: 10.1097/TP.0b013e31823817d5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Volk ML, Marrero JA, Lok AS, Ubel PA. Who decides? Living donor liver transplantation for advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. Transplantation. 2006;82:1136–1139. doi: 10.1097/01.tp.0000245670.75583.3d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Gurmankin AD, Baron J, Hershey JC, Ubel PA. The role of physicians’ recommendations in medical treatment decisions. Med Decis Making. 2002;22:262–271. doi: 10.1177/0272989X0202200314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Kassirer JP. Adding insult to injury. Usurping patients’ prerogatives. N Engl J Med. 1983;308:898–901. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198304143081511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Bramstedt KA. Living liver donor mortality: where do we stand? Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:755–759. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2006.00421.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Mulley AG., Jr Assessing patients’ utilities. Can the ends justify the means? Med Care. 1989;3(Suppl):269–281. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Donovan J, Mills N, Smith M, Brindle L, Jacoby A, Peters T, et al. Quality improvement report: improving design and conduct of randomized trials by embedding them in qualitative research: ProtecT (prostate testing for cancer and treatment) study. Commentary: presenting unbiased information to patients can be difficult. BMJ. 2002;325:766–770. doi: 10.1136/bmj.325.7367.766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Trotter JF. Selection of donors and recipients for living donor liver transplantation. Liver Transpl. 2000;6(6 Suppl. 2):52–58. doi: 10.1053/jlts.2000.18685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Lee SG. Living-donor liver transplantation in adults. Br Med Bull. 2010;94:33–48. doi: 10.1093/bmb/ldq003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Broering DC, Wilms C, Bok P, Fischer L, Mueller L, Hillert C, et al. Evolution of donor morbidity in living related liver transplantation: a single-centre analysis of 165 cases. Ann Surg. 2004;240:1013–1024. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000146146.97485.6c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Trotter JF, Adam R, Lo CM, Kenison J. Documented deaths of hepatic lobe donors for living donor liver transplantation. Liver Transpl. 2006;12:1485–1488. doi: 10.1002/lt.20875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Ghobrial RM, Freise CE, Trotter JF, Tong L, Ojo AO, Fair JH, et al. Donor morbidity after living donation for liver transplantation. Gastroenterology. 2008;135:468–476. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.04.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.de Villa V, Lo CM. Liver transplantation for hepatocellular carcinoma in Asia. Oncologist. 2007;12:1321–1331. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.12-11-1321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Fan ST, Lo CM, Liu CL, Wang WX, Wong J. Safety and necessity of including the middle hepatic vein in the right lobe graft in adult-to-adult live donor liver transplantation. Ann Surg. 2003;238:137–148. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000077921.38307.16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Marubashi S, Nagano H, Wada H, Kobayashi S, Eguchi H, Takeda Y, et al. Donor hepatectomy for living donor liver transplantation: learning steps and surgical outcome. Dig Dis Sci. 2011;56:2482–2490. doi: 10.1007/s10620-011-1622-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Renz JF, Roberts JP. Longterm complications of living donor liver transplantation. Liver Transpl. 2000;6(Suppl. 2):73–76. doi: 10.1053/jlts.2000.18686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Middleton PF, Duffield M, Lynch SV, Padbury RT, House T, Stanton P, et al. Living donor liver transplantation – adult donor outcomes: a systematic review. Liver Transpl. 2006;12:24–30. doi: 10.1002/lt.20663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Lo B, Snyder L. Care at the end of life: guiding practice where there are no easy answers. Ann Intern Med. 1999;130:772–774. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Tulsky JA, Fischer GS, Rose MR, Arnold RM. Opening the black box: how do physicians communicate about advance directives? Ann Intern Med. 1998;129:441–449. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-129-6-199809150-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Brett AS. Limitations of listing specific medical interventions in advance directives. JAMA. 1991;266:825–828. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Hanson LC, Tulsky JA, Danis M. Can clinical interventions change care at the end of life? Ann Intern Med. 1997;126:381–388. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-126-5-199703010-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Fried TR, Bradley EH, Towle VR, Allore H. Understanding the treatment preferences of seriously ill patients. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:1061–1066. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa012528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Post SG. Altruism, happiness, and health: it's good to be good. Int J Behav Med. 2005;12:66–77. doi: 10.1207/s15327558ijbm1202_4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Erim Y, Beckmann M, Valentin-Gamazo C, Malago M, Frilling A, Schlaak JF, et al. Quality of life and psychiatric complications after adult living donor liver transplantation. Liver Transpl. 2006;12:1782–1790. doi: 10.1002/lt.20907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Morioka D, Egawa H, Kasahara M, Ito T, Haga H, Takada Y, et al. Outcomes of adult-to-adult living donor liver transplantation: a single institution's experience with 335 consecutive cases. Ann Surg. 2007;245:315–325. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000236600.24667.a4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Hashikura Y, Ichida T, Umeshita K, Kawasaki S, Mizokami M, Mochida S, et al. Donor complications associated with living donor liver transplantation in Japan. Transplantation. 2009;88:110–114. doi: 10.1097/TP.0b013e3181aaccb0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Guba M, Adcock L, MacLeod C, Cattral M, Greig P, Levy G, et al. Intraoperative ′no go′ donor hepatectomies in living donor liver transplantation. Am J Transplant. 2010;10:612–618. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2009.02979.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Adcock L, Macleod C, Dubay D, Greig PD, Cattral MS, McGilvray I, et al. Adult living liver donors have excellent long-term medical outcomes: the University of Toronto liver transplant experience. Am J Transplant. 2010;10:364–371. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2009.02950.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Brown RS, Jr, Russo MW, Lai M, Shiffman ML, Richardson MC, Everhart JE, et al. A survey of liver transplantation from living adult donors in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:818–825. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa021345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Shah SA, Cattral MS, McGilvray ID, Adcock LD, Gallagher G, Smith R, et al. Selective use of older adults in right lobe living donor liver transplantation. Am J Transplant. 2007;7:142–150. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2006.01596.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Muzaale AD, Dagher NN, Montgomery RA, Taranto SE, McBride MA, Segev DL. Estimates of early death, acute liver failure, and long-term mortality among live liver donors. Gastroenterology. 2012;142:273–280. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.11.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Verbesey JE, Simpson MA, Pomposelli JJ, Richman E, Bracken AM, Garrigan K, et al. Living donor adult liver transplantation: a longitudinal study of the donor's quality of life. Am J Transplant. 2005;5:2770–2777. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2005.01092.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Ringe B, Strong RW. The dilemma of living liver donor death: to report or not to report? Transplantation. 2008;85:790–793. doi: 10.1097/TP.0b013e318167345e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Ghobrial RM, Steadman R, Gornbein J, Lassman C, Holt CD, Chen P, et al. A 10-year experience of liver transplantation for hepatitis C: analysis of factors determining outcome in over 500 patients. Ann Surg. 2001;234:384–393. doi: 10.1097/00000658-200109000-00012. Discussion 93–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Burr AT, Csikesz NG, Gonzales E, Tseng JF, Saidi RF, Bozorgzadeh A, et al. Comparison of right lobe donor hepatectomy with elective right hepatectomy for other causes in New York. Dig Dis Sci. 2011;56:1869–1875. doi: 10.1007/s10620-010-1489-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]