Abstract

The nucleotide substrate specificity of yeast poly(A) polymerase (yPAP) was examined with various ATP analogues of clinical relevance. The triphosphate derivatives of cladribine (2-Cl-dATP), clofarabine (Cl-F-ara-ATP), fludarabine (F-ara-ATP), and related derivatives were incubated with yPAP and 32P-radiolabeled RNA oligonucleotide primers in the absence of ATP to assay polyadenylation. While 2-Cl-ATP resulted in primer elongation, ara-ATP and F-ara-ATP were poor substrates for yPAP. In contrast, the triphosphate derivatives of cladribine (2-Cl-dATP), clofarabine (Cl-F-ara-ATP) and its corresponding deoxyribose derivative (Cl-F-dATP) were substrates and caused chain termination in the absence of ATP. We further investigated whether analog incorporation at the 3′-terminus of RNA primers negatively impacts polyadenylation with ATP by generating RNA oligonucleotides containing either a terminal clofarabine, Cl-F-dAdo, or cladribine residue. Incorporation of any of these analogs blocks the ability of yPAP to extend RNA past the analog site, impeding the addition of a poly(A)-tail. To determine whether modified ATP analogues exhibit a concentration dependent effect on polyadenylation, poly(A)-tail synthesis by yPAP with modified ATP analogues in combination with a constant level of ATP was also examined. With all the ATP analogues assayed in these studies, there was a significant reduction in poly(A)-tail length with increasing amounts of analog triphosphate. Taken together, our results suggest that polyadenylation inhibition may be a component in the mechanism of action of adenosine analogues.

Keywords: RNA processing, transcription, polyadenylation inhibition, nucleoside analogs, cladribine, clofarabine, fludarabine

Introduction

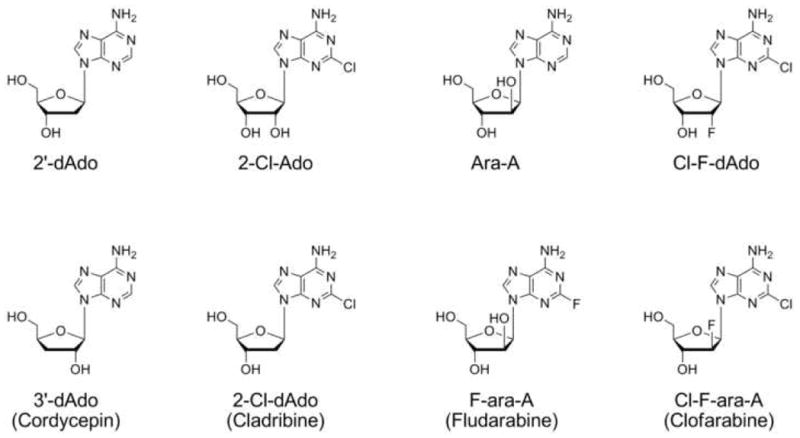

Nucleoside analogues are chemotherapeutic agents that have been successful in the clinic towards a number of cancer types. In particular, deoxyadenosine-based analogues such as cladribine and fludarabine (Figure 1) have both been shown to be active against various forms of leukemias and lymphomas (reviewed in [1]). Clofarabine, a second generation chemotherapeutic agent developed following the effectiveness of fludarabine, is active against several hematological malignancies, including acute and chronic leukemias (reviewed in[2]), myelodysplastic syndromes [3], and advanced pediatric acute leukemias [4].

Figure 1.

Chemical structures of various nucleoside analogues.

An advantageous feature of nucleoside analogues is that they exhibit antineoplastic activity against replicating cells by targeting DNA-related events, as well as quiescent cells via DNA-independent mechanisms. We are currently investigating the role of adenosine and deoxyadenosine analogues on RNA-directed mechanisms [5–8]. Our rationale for studying RNA-related processes stems from previous findings that related adenosine analogues under investigation in our laboratory inhibit polyadenylation. Previously, we have demonstrated that 8-chloroadenosine (8-Cl-Ado), 8-aminoadenosine (8-amino-Ado), and 8-azidoadenosine inhibit yeast poly(A) polymerase (yPAP) in cell-free primer extension assays [7]. We have also shown that a known polyadenylation inhibitor, cordycepin (3′-deoxyadenosine, 3′-dAdo), induces cell death in multiple myeloma cell lines [9], thus we are investigating effects of other clinically relevant deoxyadenosine analogs on polyadenylation.

During post-transcriptional processing, pre-mRNA is modified into functional transcripts via three major steps: 5′-end methylguanosine capping, splicing, and 3′-end cleavage and polyadenylation. Polyadenylation is catalyzed by poly(A) polymerase (PAP) and is one of the key steps in the post-transcriptional RNA processing required for the synthesis and maintenance of mRNA transcripts. 3′-End cleavage and polyadenylation in vivo are tightly regulated processes coupled to transcription (reviewed in [10]), involving numerous protein complexes [11]. The addition of a 3′-end poly(A) tail to eukaryotic mRNAs is required for the transport of RNA from the nucleus to the cytoplasm [12], translation efficiency [13], and the regulation of mRNA degradation [14]. RNA poly(A)-tail length has also been shown to correlate with mRNA stability [15].

PAP protein expression and activity appears to be altered in cancerous cells compared to non-cancerous cells. The catalytic activity of PAP has been found to be higher in acute leukemia cell extracts as compared to those from chronic leukemias, which was greater than in normal lymphocytes [16, 17]. Similarly, PAP is overexpressed in more aggressive forms of breast cancer compared to the indolent forms of the disease, and may serve as a poor prognostic marker in primary breast cancer [18]. Since polyadenylation is a process that is required for cell survival and occurs independent of DNA synthesis, targeting polyadenylation may be an effective RNA-directed strategy for the treatment of cancers.

Polyadenylation is a template-independent step catalyzed by PAP, which uses ATP as its substrate. Given that halogenated analogues cladribine, fludarabine, and clofarabine contain a similar adenosine core structure as ATP, our hypothesis is that they may also be a substrate for PAP and affect polyadenylation efficiency. Once these drugs are metabolized intracellularly into their corresponding triphosphate derivatives, they may be incorporated efficiently into poly(A)-tails by PAP. Alternatively, analog triphosphates may inhibit polyadenylation via two different mechanisms. First, they may be directly incorporated into nascent RNAs during either transcription or polyadenylation, and prevent further primer elongation causing subsequent chain termination. Second, they may act as inhibitors for PAP and reduce the poly(A)-tail length of newly synthesized RNAs, which would reduce the stability of the transcript as well as negatively affect the nuclear transport and translation efficiency. In particular, polyadenylation inhibition may have a significant impact on transcripts that have a short half-life, and thus understanding the effects of analogs with an adenine base on PAP is key for the further development of RNA-directed agents.

In the present report, we examined the ATP derivatives of several deoxyadenosine analogues used to treat hematological malignancies in RNA polyadenylation assays using yPAP. The analogues investigated include cladribine, fludarabine, and clofarabine, and related derivatives. The triphosphates of cladribine (2-Cl-dATP) and clofarabine (Cl-F-ara-ATP) both produce chain termination during RNA primer extensions with yPAP in the absence of ATP. Incorporation of either cladribine or clofarabine into the 3′-terminus of RNA also hindered the ability of yeast PAP to produce chain extension with ATP. In primer extension reactions including both analog triphosphate and ATP simultaneously, a concentration-dependent reduction in poly(A)-tail length was observed with the triphosphate derivatives of cladribine, fludarabine (F-ara-ATP), clofarabine, and thus polyadenylation inhibition may contribute to the cytotoxicity of these chemotherapeutics.

Materials and Methods

Materials

T4 polynucleotide kinase (30 units/μL) and yPAP (600/μL) were purchased from United States Biochemical Corp (Cleveland, OH). Enzyme concentrations of yPAP for polyadenylation assays (reported in units/μL of reaction total volume in the protocols below). A 10-bp DNA ladder was obtained from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA). [γ-32P] ATP (7000 Ci/mmol) was purchased from Moravek Biochemicals (Brea, CA). ATP, 2′-dATP, GTP, and dGTP were obtained from Amersham Biosciences (Piscataway, NJ), and ara-ATP was obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (A-6642, St. Louis, MO). Cordycepin triphosphate (3′-dATP) and 2-Cl-ATP were procured from Ambion Inc (Austin, TX). Clofarabine triphosphate (Cl-F-ara-ATP), fludarabine triphosphate (F-ara-ATP), Cl-F-dATP, cladribine triphosphate (2-Cl-dATP), and ara-GTP were custom synthesized by Sierra BioResearch (Tuscon, AZ). Radioactive bands on polyacrylamide gels were visualized using an Amersham Biosciences Storm PhosphorImager and analyzed using Amersham Biosciences ImageQuant software.

RNA Oligonucleotides

RNA primer 5′-UGUGCCCGA-3′ was purchased from Dharmacon Research Inc.(Lafayette, CO) and was deprotected at 37 °C for 30 min with 400 μL of 100 mM acetic acid, adjusted to pH 3.8 with TEMED. The purity was verified by RP-HPLC and MALDI-TOF-MS (calculated [M]+ = 2832.8 and found [M]+ = 2829.7), and the oligonucleotide was used without further purification.

Preparation of 5′-32P-Radiolabeled Oligonucleotides

RNA oligonucleotide primer 5′ UGU GCC CGA 3′ (20 pmol) was incubated at 37 °C for 60 min with 10.5 units of T4 polynucleotide kinase in a 20 μL reaction mixture containing 10 mM Tris acetate, 10 mM magnesium acetate, 50 mM potassium acetate, and 24 pmol of [γ-32P]ATP (8.4 Ci/μL, 7000 Ci/mmol). The reaction was quenched with 2 μL of 100 mM EDTA, and the labeled RNA was purified by 7 M -20% denaturing polyacylamide gel electrophoresis (dPAGE) with 89 mM Tris, 89 mM borate, and 1 mM EDTA as the running buffer. The radiolabeled RNA was visualized by autoradiography, excised, and eluted by soaking the gel piece in 100 μL of buffer (200 mM NaCl, 10 mM Tris at pH 7.5, 1 mM EDTA) at 25 °C for 12 h. The eluted product was purified using a NAP-5 Sephadex G-25 column and stored in double-distilled H2O.

yPAP Substrate Specificity Assays

Radiolabeled RNA oligonucleotide primer 5′ UGU GCC CGA 3′ (200 nM) was incubated at 37 °C for 1 h in a solution containing yPAP and a single modified nucleoside triphosphate in the absence of ATP. The extension reactions were analyzed by 7 M-20% dPAGE. Final extension conditions were as follows: 250 μM analog NTP, 200 nM RNA primer, and 4 U/μL yPAP in yPAP reaction buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.0), 50 mM KCl, 0.7 mM MnCl2, 0.2 mM EDTA, 100 μg/ml acetylated BSA, and 10% glycerol). The triphosphates assayed were ATP, 2′-dATP, 3′-dATP, 2-Cl-ATP, 2-Cl-dATP, ara-ATP, F-ara-ATP, Cl-F-ara-ATP, Cl-F-dATP, GTP; dGTP, ara-GTP. Each experiment was performed in triplicate

Isolation and Polyadenylation of 3′-Terminal Modified Primers

Radiolabeled RNA primer 5′ UGU GCC CGA 3′ (200 nM) was incubated at 37 °C for 1 h in a solution containing yPAP and a single modified nucleoside triphosphate in the absence of ATP. The extension reactions were analyzed by 7 M-20% dPAGE. Final extension conditions were as follows: 250 μM analog NTP, 200 nM RNA primer, 24 U/μL yPAP in yPAP reaction buffer. The triphosphates assayed were 2-Cl-dATP, Cl-F-ara-ATP, and Cl-F-dATP. The extension reactions were terminated by the addition of 1 volume of 2x gel loading buffer, and the products were analyzed by 7 M-20% dPAGE. The chain terminated products were visualized by autoradiography, excised, and eluted by soaking the gel piece in 100 μL of buffer (200 mM NaCl, 10 mM Tris (pH 7.5), 1 mM EDTA) at 25 °C for 12 h. The eluted products were purified using a NAP-5 Sephadex G-25 column (Amersham Biosciences) and stored in double-distilled H2O. The 3′-terminal modified RNA primers then were incubated at 37 °C for 1 h in a solution containing 100 μM ATP, and 4 U/μL yPAP in yPAP reaction buffer. The extension reactions were terminated by the addition of 1 volume of 2x gel loading buffer, and the products were analyzed by 7 M-20% dPAGE. Each experiment was performed in triplicate

Polyadenylation Inhibition Assays with Unnatural Triphosphates and ATP

Radiolabeled RNA primer 5′ UGU GCC CGA 3′ (200 nM) was incubated at 37 °C for 1 h in a solution containing 250 μM ATP, 10–250 μM analog NTP, 4 U/μL yPAP in yPAP reaction buffer. The triphosphates assayed were F-ara-ATP, ara-ATP, 2-Cl-dATP, Cl-F-ara-ATP and Cl-F-dATP. The extension reactions were terminated by the addition of 1 volume of 2x gel loading buffer, and the products were analyzed by 7 M-20% dPAGE. Each experiment was performed in triplicate.

Results

Poly(A) Polymerase Nucleotide Specificity

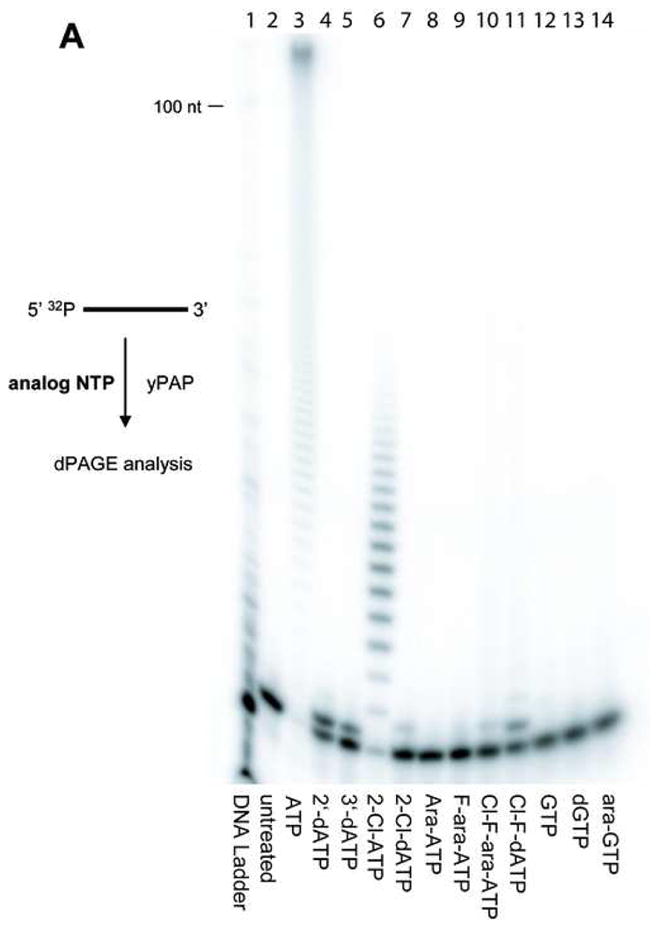

To assess the substrate specificity of yPAP, a number of modified ATP analogues were assayed with yPAP under standard conditions[19]. The chemical structures of the parent nucleoside analogues are shown in Figure 1. Primer extensions with yPAP were conducted using a synthetic RNA primer (5′-UGUGCCCGA-3′) in reactions containing 200 nM RNA primer and 250 μM each analogue triphosphate in the absence of ATP. The extension reactions were incubated at 37 °C for 1 h and then analyzed by 20% dPAGE as shown in Figure 2A. Polyadenylation in the presence of the natural substrate ATP produced a poly(A) tail several hundred nucleotides in length (Figure 2A, lane 3). Known PAP inhibitor, 2′-dATP [20, 21], and chain terminator, 3′-dATP [22–24], were used as a positive controls. Incubation with 2′dATP or 3′-dATP produced a single extension product (Figure 2A, lanes 4–5), consistent with incorporation and chain termination. Polyadenylation reactions with modified nucleotides exhibited similarities based on the type of modification. Both 2-Cl-ATP and its deoxyribose analogue 2-Cl-dATP were incorporated by yPAP into the 3′-terminus of the RNA primer, however, in different fashions. Although poly(A)-tail synthesis with 2-Cl-ATP alone was less than with natural ATP, the poly(A)-tail was extended beyond ten nucleotides in length (Figure 2A, lane 6). In contrast, the active metabolite of cladribine, 2-Cl-dATP, resulted in a single termination product with no further detectable extension (Figure 2A, lane 7). While both 2-Cl-ATP and 2-Cl-dATP were substrates for yPAP, neither arabinosyl analogues, ara-ATP nor F-ara-ATP, appeared to be incorporated by yPAP (Figure 2A, lanes 8–9). Interestingly, the active metabolite of clofarabine, Cl-F-ara-ATP, which contains a fluorine atom in the arabinose C2′-position instead of a hydroxyl group, acts as a chain terminator for yPAP (Figure 2A, lane 10). Although only a low level of extended product was detected, the resulting product was only one nucleotide longer, which is indicative of chain termination. Similarly, the related analogue Cl-F-dATP which contains a fluorine atom in the ribose C2′-position, is also a chain terminator (Figure 2A, lane 11). To verify that our experimental system was consistent with the natural selectivity of PAP for ATP over other purine nucleotides, primer extension assays were also conducted with three 5′-triphosphates of guanine nucleosides; GTP, dGTP and arabinosyl-GTP (ara-GTP) (Figure 2A, lane 12–14). In all cases, no significant incorporation into the primer was detected above untreated primer alone. A graphical representation of the results from Figure 2A are shown in Figure 2B. Primer extension products and unextended primers were quantified using ImageQuant software and corrected for background noise level, then expressed as a percentage of the total signal. The extended products were classified into two categories; primers extended by a single nucleotide and primers extended beyond one nucleotide. The primer extensions that resulted in a majority of the product accumulating as the single extension product were considered chain terminators in these assays. As evident from the data (Figure 2B), primer incubated with ATP resulted in >95% product that was greater than one nucleotide in length. Among all analogues tested, 2-Cl-ATP showed a similar extension profile. 2′-dATP and 3′-dATP, as well as Cl-F-dATP were good substrates for incorporation but only a small percent of these primers were extended further. Importantly, triphosphates of cladribine, fludarabine, clofarabine and ara-A were not good substrates for incorporation. In fact, F-ara-ATP and ara-ATP behaved similarly as triphosphates containing guanine rather than an adenine base. In all of these cases the incorporation was less than 10% of the total substrate.

Figure 2. Substrate specificity of yPAP toward various purine triphosphate analogues.

(A) Elongation of RNA primer 5′ UGU GCC CGA 3′ by yPAP. A mixture containing 200 nM 5′-32P-radiolabeled RNA primer, 4 U/μL yPAP, 250 μM analogue triphosphate, 20 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.0), 50 mM KCl, 0.7 mM MnCl2, 0.2 mM EDTA, 100 μg/ml acetylated BSA, and 10% glycerol was incubated at 37 °C for 1 h. The products were analyzed by 20% dPAGE. Lane 1, radiolabeled 10-bp DNA ladder; lane 2, 5′-32P-radiolabeled unextended primer (no NTP); lane 3, ATP; lane 4, 2′-dATP; lane 5, 3′-dATP; lane 6, 2-Cl-ATP; lane 7, 2-Cl-dATP; lane 8, ara-ATP; lane 9, F-ara-ATP; lane 10, Cl-F-ara-ATP; lane 11, Cl-F-dATP, lane 12, GTP; lane 13, dGTP, lane 14, ara-GTP. (B) Graphical representation of RNA primer extension by yPAP with various modified triphosphates. Shown is the distribution of single extension products (white) and full extension products beyond first incorporation (hatched) as a percentage of the total counts in each lane, as determined using ImageQuant software. These experiments were conducted in triplicate with similar results.

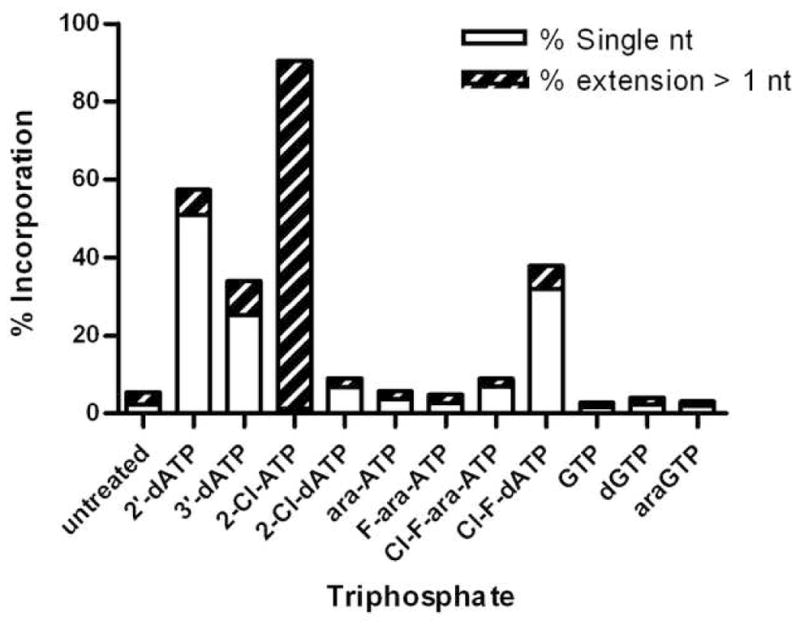

3′-Terminal Cladribine, Clofarabine and Cl-F-dAdo Residues Block Polyadenylation

Data from the previous experiment (Figure 2) suggest that 2-Cl-dATP, Cl-F-ara-ATP and Cl-F-dATP chain terminate RNA primer extension in the absence of ATP. However, it was unclear whether yPAP would be able to synthesize poly(A)-tails with ATP following the incorporation of any of these three analogues. In order to assess effects of incorporation of either 2-Cl-dATP, Cl-F-ara-ATP or Cl-F-dATP at 3′-terminal sites, the chain terminated RNA products were generated and re-assayed in the presence of ATP and yPAP. Synthetic RNA oligonucleotides containing 3′-terminal modifications were produced by repeating the primer extension reactions as in Figure 2A. The unextended primers and chain terminated products were visualized using autoradiography and isolated. Following elution from the gel fragments, both the unextended primers and 3′-terminal modified products were re-assayed in polyadenylation reactions with yPAP at 37 °C, with or without ATP (Figure 3). Control primer extension resulted in rapid poly(A)-tail extension (Figure 3, lane 2) over a hundred nucleotides in length. The unextended RNA primer recovered from the gel fragments was re-subjected to polyadenylation conditions (Figure 3, lane 5), and showed a reduced poly(A)-tail length compared to control, which may have resulted from salts during gel elution. The 3′-terminal chain terminated products containing 2-Cl-dATP (lanes 6–7), Cl-F-ara-ATP (lanes 8–9) and Cl-F-dATP (lanes 10–11) were all re-assayed with yPAP in the presence or absence of ATP, and analyzed by 20% dPAGE. In all three cases, the site-specific introduction of 3′-terminal modified ATP analogues inhibited polyadenylation by yPAP. Only very slight primer extension of one nucleotide was observed in each case, suggesting that 2-Cl-dATP, Cl-F-ara-ATP, Cl-F-dATP at 3′-terminal sites block poly(A)-tail synthesis by yPAP.

Figure 3. Deoxyadenosine analogues block polyadenylation of RNA primers by yPAP and ATP.

Elongation of RNA primer 5′ UGU GCC CGA X 3′, where X is modified with deoxyadenosine analogues. A solution containing 5′-32P-radiolabeled RNA primer, 4 U/μL yPAP, 100 μM ATP, 20 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.0), 50 mM KCl, 0.7 mM MnCl2, 0.2 mM EDTA, 100 μg/ml acetylated BSA, and 10% glycerol was incubated at 37 °C for 1 h. The products were analyzed by 20% dPAGE. Lane 1, radiolabeled 10-bp DNA ladder; lane 2, 5′-32P-radiolabeled primer (no modification); lane 3, control primer and ATP; lane 4, Ado terminated primer; lane 5, Ado terminated primer and ATP; lane 6, 2-Cl-dAdo terminated primer; lane 7, 2-Cl-dAdo terminated primer and ATP; lane 8, Cl-F-ara-A terminated primer; lane 9, Cl-F-ara-A terminated primer and ATP; lane 10, Cl-F-dAdo terminated primer; lane 11, Cl-F-dAdo terminated primer and ATP. These experiments were conducted in triplicate and a single representative gel is shown.

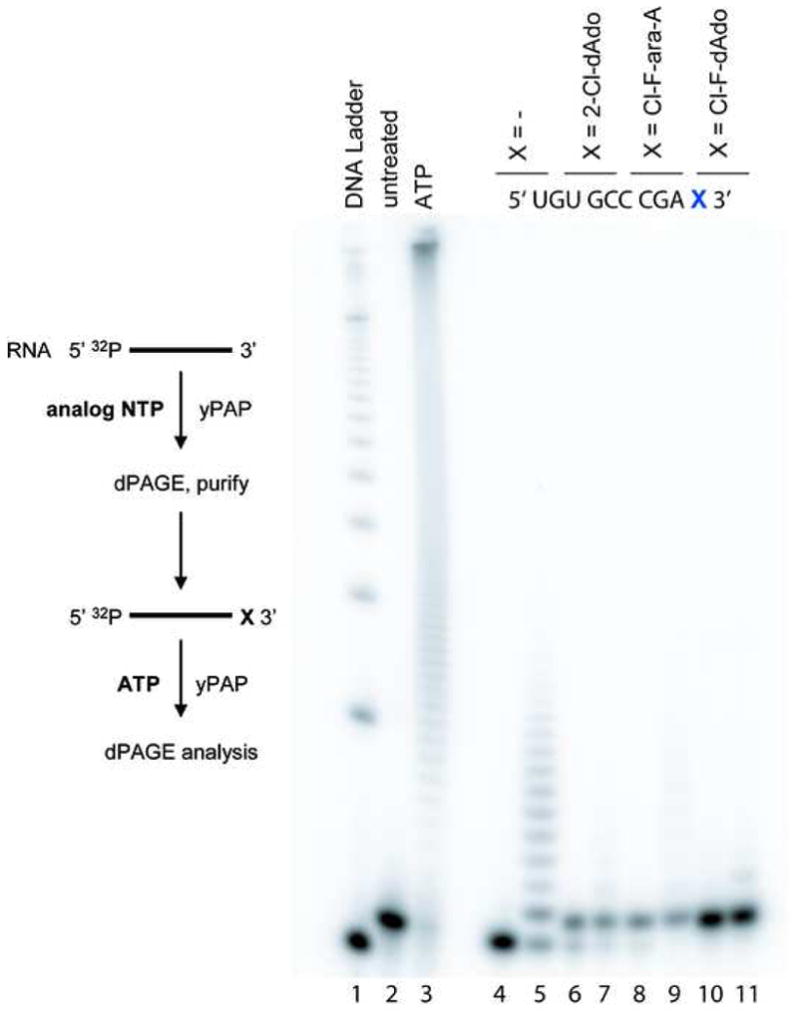

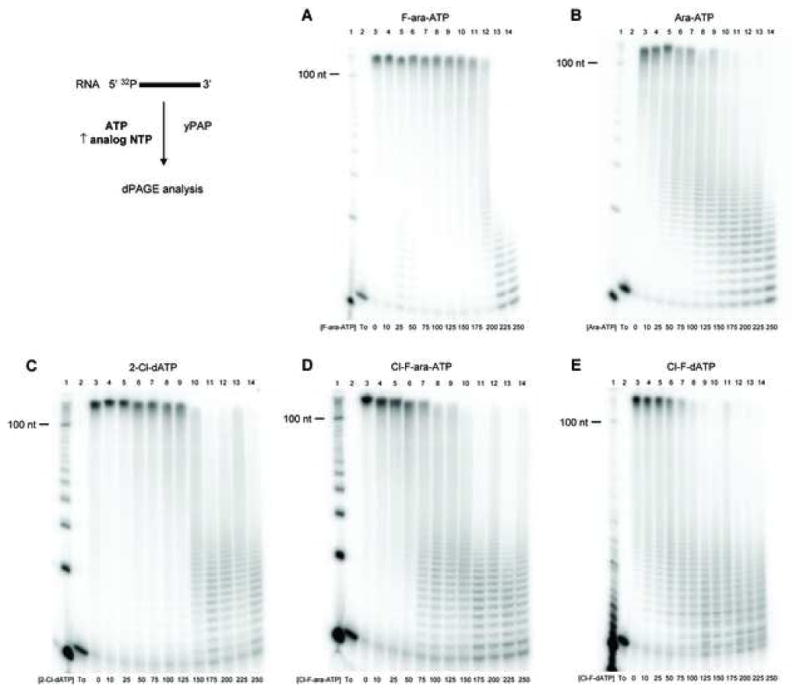

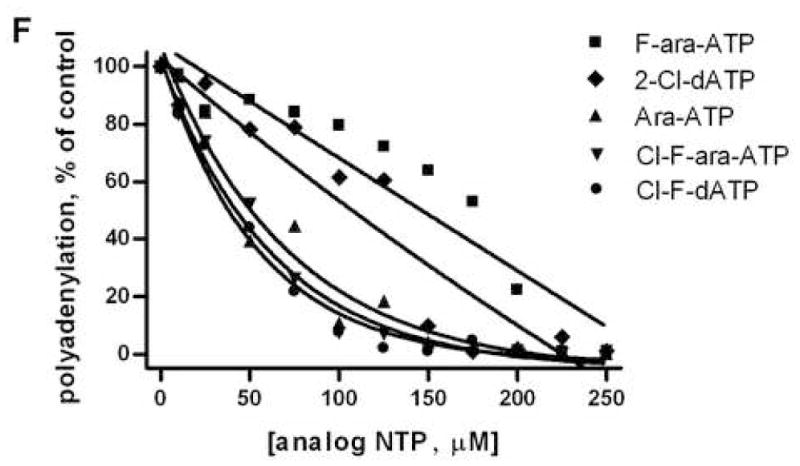

Inhibition of Polyadenylation by Modified ATP Analogues

While polyadenylation inhibition may occur following direct incorporation and subsequent chain termination, we also assessed whether inhibition was a result of competitive inhibition with ATP. For example, ara-ATP has previously been shown to inhibit polyadenylation by HeLa nuclear extracts in a competitive manner without incorporation into RNA [25]. Our results are consistent, and primer extension with yPAP and ara-ATP is not observed at detectable levels higher than primer alone. To assess the potential inhibition of yPAP by the same panel of ATP analogues, increasing amount of various ATP analogues were included in yPAP primer extension assays holding ATP constant. The same RNA primer used previously was incubated at 37 °C with yPAP, 250 μM ATP, and increasing amounts from 0 to 250 μM analogue triphosphate F-ara-ATP (Figure 4A), ara-ATP (Figure 4B), 2-Cl-dATP (Figure 4C), Cl-F-ara-ATP (Figure 4D), or Cl-F-dATP (Figure 4E). The reaction products were analyzed by 20% dPAGE, and the RNA primer alone and control primer extension with ATP alone are shown in lanes 2 and 3, respectively, or each figure. The percentage of poly(A)-tails greater than one hundred nucleotides in length relative to polyadenylation reactions with ATP alone were calculated using ImageQuant software for the varying concentration of each ATP analogue (Figure 4F). Although F-ara-ATP and ara-ATP were not chain terminators for yPAP, higher concentrations of each analogue resulted in the reduction of poly(A)-tail length with ATP. Under our assay conditions, concentrations of F-ara-ATP greater than 200 μM significantly reduce poly(A)-tail length (Figure 4A, lanes 13–14) and ara-ATP also shows a concentration-dependent reduction in tail length (Figure 4B, lanes 4–14). Similarly, the three chain terminators, 2-Cl-dATP, Cl-F-ara-ATP, Cl-F-dATP also show a reduction in poly(A)-tail length with increasing concentration (Figures 4C–E). To compare the potency of the analogue triphosphates when incubated with ATP, the relative level of polyadenylation compared to ATP alone was measured as a function of increasing analogue concentration (Figure 4F). As discussed above, all five analogues result in a concentration-dependent reduction in poly(A)-tail length. Cl-F-ara-ATP, Cl-F-dATP, and ara-ATP all reduce polyadenylation to ~50% of control at concentrations of approximately 40–50 μM under our assay conditions. 2-Cl-dATP was less potent and 50% reduction in primer extension was observed using ~100 μM of analogue. Finally, of the analogues assessed in this assay, F-ara-ATP was the least potent inhibitor of ATP-dependent poly(A)-tail synthesis, and concentrations about 125–150 μM were required to reduce polyadenylation to 50% of control reactions. Taken together, these results suggest that the ATP analogues F-ara-ATP, ara-ATP, 2-Cl-dATP, Cl-F-ara-ATP, and Cl-F-dATP all inhibit yPAP polyadenylation with ATP.

Figure 4. Reduction of poly(A) tail length by modified ATP analogues.

Gel electrophoretic analyses of an RNA primer 5′ UGU GCC CGA 3′ with yPAP, 250 μM ATP, and increasing amounts of ATP analogue: (A) F-ara-ATP, (B) Ara-ATP, (C) 2-Cl-dATP, (D) Cl-F-ara-ATP and (E) Cl-F-dATP. For each set of reactions, a solution (5 μL) containing 200 nM 5′-32P-radiolabeled RNA primer, 4U/μL yPAP, 100 μM ATP, 0–250 μM analogue ATP, 20 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.0), 50 mM KCl, 0.7 mM MnCl2, 0.2 mM EDTA, 100 μg/mL acetylated BSA, and 10% glycerol was incubated at 37 °C for 1 h. The products were analyzed by 20% dPAGE. Lane 1, radiolabeled 10-bp DNA ladder; lane 2, 5′-32P-radiolabeled primer (no triphosphates); lane 3, ATP only; lanes 4–14, 250 μM ATP with 10, 25, 50, 75, 100, 125, 150, 175, 200, 225, or 250 μM analogue triphosphate, respectively. (F) Graphical representation of figures (A–E). The extension of poly(A)-tail length for the varying concentrations of F-ara-ATP (■), Ara-ATP (▲), 2-Cl-dATP (◆), Cl-F-ara-ATP (▼), and Cl-F-dATP (●) were measured using ImageQuant analysis and then compared with control (without analogue) RNA primer extensions and expressed as a percentage of control. These experiments were conducted in triplicate with similar results.

Discussion

The results presented in this paper suggest that polyadenylation inhibition by cladribine, fludarabine, or clofarabine may be a potential RNA-directed mechanism of action for these agents. The triphosphate derivatives of all three agents alone result in the reduction of poly(A)-tail length in a concentration dependent manner when incubated in tandem with ATP. Furthermore, incorporation of cladribine or clofarabine into the 3′-terminus of RNA primers blocks the ability of PAP to efficiently synthesize poly(A)-tails with ATP. Modification of the sugar moiety from ribose to arabinose (ara-ATP and F-ara-ATP) appears to negatively impact the ability for PAP to accept arabinose trisphosphates as substrates. While neither arabinose analogue is a substrate for yPAP, however the fluorinated arabinose analogue of clofarabine, Cl-F-ara-ATP, was an effective chain terminator. It is interesting to note that consistent with previous studies [7], the ATP analogues assessed in this study bearing modifications at the C-2 position in the adenine ring remain substrates for yPAP. Similarly, C-2 modified ATP analog, 2-amino-ATP, is used efficiently as a substrate by bovine PAP [26]. This is in contrast to a recent crystal structure of yPAP[27], which suggests that substrate specificity of PAP discriminates against groups at C2 of purines as a mechanism for selection of ATP over GTP.

Our results presented here infer a possible additional mechanism of action for cladribine, which is prescribed for the treatment of hairy cell leukemia (HCL)[28]. HCL is an indolent leukemia, and thus although cladribine is a deoxyadenosine analogue and is directed toward DNA, the RNA-directed inhibition of polyadenylation may explain, in part, the actions towards RNA. Cladribine has been shown to be cytotoxic to both replicating and resting cells [29, 30]. In replicating cells, the mechanism of action for cladribine is largely DNA-targeted, and 2-Cl-dATP causes chain termination of DNA synthesis [31, 32], and decreases dNTP pool levels via the inhibition of ribonucleotide reductase [33]. In quiescent cells, previously proposed mechanisms of cytotoxicity still involve DNA-related events. Cladribine incorporation into DNA inhibits cellular nucleotide excision DNA repair, resulting in the accumulation of DNA single-strand breaks, which ultimately leads to the induction of apoptosis via p53-dependent and p53-independent pathways [34–36]. Other proposed mechanisms involved include the disruption of mitochondrial integrity [37], and activation of caspases [38, 39], but studies have also indicated that cladribine incorporation into DNA reduced the level of full-length transcripts [40]. The inhibition of polyadenylation by 2-Cl-dATP presented here also is consistent with the decrease in full-length transcripts. We have shown that 2-Cl-dATP is incorporated into RNA primers by PAP causing chain termination, and that poly(A)-tail synthesis with ATP is abrogated following 3′-terminal RNA cladribine sites. In chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) patients treated with cladribine, intracellular concentrations 2-Cl-dATP in circulating leukemia cells were a median of 22μM [41] Although the nuclear concentration of 2-Cl-dATP in unknown, the levels accumulated are sufficient to chain terminate DNA synthesis and inhibit ribonucleotide reductase, as described above. Given that a significant proportion of RNA polyadenylation occurs in the nucleus, polyadenylation inhibition by 2-Cl-dATP may contribute to its overall mechanism of action.

Fludarabine is also cytotoxic to both dividing and resting cells and, in dividing cells, inhibits a number of DNA-related enzymes including ribonucleotide reductase [42], DNA polymerase alpha [43], DNA primase, DNA ligase, and topoisomerase II [44]. In resting cells, the mechanism of fludarabine appears to be RNA-directed [42]. Huang et al. demonstrated that F-ara-ATP inhibits RNA polymerase II, and that F-ara-A was preferentially incorporated into the poly(A)+ RNA fraction [45]. They further reported that ~78% of the incorporated fludarabine residues were located at the terminal position of RNA, subsequently terminating the RNA transcript and impairing its translation. In primary CLL cells, fludarabine cytotoxicity is directly correlated with inhibition of RNA transcription [8], and cellular F-ara-ATP accumulation in myeloblasts and CLL cells has been measured to range between 20 and 60 μM [46]. As discussed above with cladribine, these values reflect intracellular concentrations, and the nuclear concentration of F-ara-ATP may be higher. Our results that F-ara-ATP inhibits poly(A)-tail synthesis is concordant with the previous RNA-directed studies on fludarabine (Figure 4). Inhibition of RNA polyadenylation reduces transcript stability and translational efficiency, which coupled with a reduction in transcription, could significantly reduce the mRNAs levels for specific oncogenes. Indeed, a correlation was observed between cytotoxicity and the level of Bcl-2 mRNA downregulation following F-ara-A treatment [47].

In the case of clofarabine, the mechanisms of action reported to date include the inhibition of ribonucleotide reductase, and the incorporation of clofarabine into internal and terminal DNA sites, which causes chain termination and strand breakage leading to apoptosis. [37, 48, 49]. The published reports on clofarabine action focus largely on DNA-related events, however, our results indicate that RNA-directed effects may also contribute to its mechanism of action. Cl-F-ara-ATP alone with PAP causes chain termination during RNA polyadenylation. We further demonstrated that isolation of RNA primers terminated with a clofarabine residue at the 3′-terminal end blocks the ability for PAP to add a poly(A)-tail using the natural substrate ATP (Figure 3). In cases where both ATP and Cl-F-ara-ATP are present in the polyadenylation assays, there is a substantial decrease in poly(A)-tail length (Figure 4). These results suggest that clofarabine action may involve RNA-directed mechanisms. During therapy circulating leukemia cells accumulate clofarabine triphosphate at an intracellular concentration of 50 μM at the maximum tolerated dose (40mg/m2/d for 5 days) [50, 51]. Furthermore, there was an incremental increase in the triphosphate with daily infusions. In addition, clofarabine triphosphate is long-lived in leukemia cells, thus it is highly likely that inhibition of polyadenylation in achieved because 50% inhibition was obtained with 50 μM clofarabine triphosphate (Figure 4D and F). To aid this inhibition, 3′-terminal clofarabine moiety will inhibit any further polyadenylation (Figure 3). Taken together, these data suggest a role of clofarabine in polyadenylation inhibition.

In summary, polyadenylation inhibition may contribute to the mechanism of action of cladribine, fludarabine, and clofarabine in non-replicating hematological malignancies and polyadenylation inhibitors may represent a new strategy in targeting indolent cancers. Our ongoing work is focused on extending our observations using a yeast model system to include studying the effects of adenosine analogues on mammalian polyadenylation events. Because there is a high homology between the yeast and mammalian enzyme, we believe that data would be similar with mammalian PAP as observed with yPAP in the current report.

Acknowledgments

This work is supported in part by grants CA85915 and CA57629 from the National Cancer Institute, Department of Health and Human Services; and a Translational Research Award from the Leukemia and Lymphoma Society of America.

Footnotes

This work was previously presented as an abstract at the 2006 Annual AACR Meeting.

Contribution:

LSC: Designed and performed all of the experiments for this manuscript, analyzed data, and wrote the manuscript.

WP: Conceptualized this research and participated in writing the manuscript.

VG: Conceptualized this research and directed LSC for the design of experiments and analyses of data. She participated in writing the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: Authors do not have any conflict of interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Robak T, Korycka A, Kasznicki M, Wrzesien-Kus A, Smolewski P. Purine nucleoside analogues for the treatment of hematological malignancies: Pharmacology and clinical applications. Curr Cancer Drug Tar. 2005;5:421–444. doi: 10.2174/1568009054863618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bonate PL, Arthaud L, Cantrell WR, Jr, Stephenson K, Secrist JA, III, Weitman S. Discovery and development of clofarabine: a nucleoside analogue for treating cancer. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2006;5:855–863. doi: 10.1038/nrd2055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Faderl S, Gandhi V, O’Brien S, Bonate P, Cortes J, Estey E, Beran M, Wierda W, Garcia-Manero G, Ferrajoli A, Estrov Z, Giles FJ, Du M, Kwari M, Keating M, Plunkett W, Kantarjian H. Results of a phase 1–2 study of clofarabine in combination with cytarabine (ara-C) in relapsed and refractory acute leukemias. Blood. 2005;105:940–947. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-05-1933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jeha S, Gandhi V, Chan KW, McDonald L, Ramirez I, Madden R, Rytting M, Brandt M, Keating M, Plunkett W, Kantarjian H. Clofarabine, a novel nucleoside analog, is active in pediatric patients with advanced leukemia. Blood. 2004;103:784–789. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-06-2122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Balakrishnan K, Stellrecht CM, Genini D, Ayres M, Wierda WG, Keating MJ, Leoni LM, Gandhi V. Cell death of bioenergetically compromised and transcriptionally challenged CLL lymphocytes by chlorinated ATP. Blood. 2005;105:4455–4462. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-05-1699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Balakrishnan K, Wierda WG, Keating MJ, Gandhi V. Mechanisms of Cell Death of Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia Lymphocytes by RNA-Directed Agent, 8-NH2-Adenosine. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11:6745–6752. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-0553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen LS, Sheppard TL. Chain termination and inhibition of Saccharomyces cerevisiae poly(A) polymerase by C8-modified ATP analogs. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:40405–40411. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M401752200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Huang P, Sandoval A, Van Den Neste E, Keating MJ, Plunkett W. Inhibition of RNA transcription: A biochemical mechanism of action against chronic lymphocytic leukemia cells by fludarabine. Leukemia. 2000;14:1405–1413. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2401845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen LS, Stellrecht CM, Gandhi V. RNA-directed agent, cordycepin, induces cell death in multiple myeloma cells. Br J Haematol. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2007.06955.x. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gilmartin GM. Eukaryotic mRNA 3′ processing: A common means to different ends. Genes Dev. 2005;19:2517–2521. doi: 10.1101/gad.1378105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Colgan DF, Manley JL. Mechanism and regulation of mRNA polyadenylation. Genes Dev. 1997;11:2755–2766. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.21.2755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Huang Y, Carmichael GC. Role of polyadenylation in nucleocytoplasmic transport of mRNA. Mol Cell Biol. 1996;16:1534–1542. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.4.1534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sachs AB, Sarnow P, Hentze MW. Starting at the beginning, middle, and end: translation initiation in eukaryotes. Cell. 1997;89:831–838. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80268-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wilusz CJ, Wormington M, Peltz SW. The cap-to-tail guide to mRNA turnover. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2001;2:237–246. doi: 10.1038/35067025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Beelman CA, Parker R. Degradation of mRNA in eukaryotes. Cell. 1995;81:179–183. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90326-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Trangas T, Courtis N, Pangalis GA, Cosmides HV, Ioannides C, Papamichail M, Tsiapalis CM. Polyadenylic acid polymerase activity in normal and leukemic human leukocytes. Cancer Res. 1984;44:3691–3697. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Topalian SL, Kaneko S, Gonzales MI, Bond GL, Ward Y, Manley JL. Identification and functional characterization of neo-poly(A) polymerase, an RNA processing enzyme overexpressed in human tumors. Mol Cell Biol. 2001;21:5614–5623. doi: 10.1128/MCB.21.16.5614-5623.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Scorilas A, Talieri M, Ardavanis A, Courtis N, Dimitriadis E, Yotis J, Tsiapalis CM, Trangas T. Polyadenylate polymerase enzymatic activity in mammary tumor cytosols: a new independent prognostic marker in primary breast cancer. Cancer Res. 2000;60:5427–5433. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Haff LA, Keller EB. Polyadenylate polymerases from yeast. J Biol Chem. 1975;250:1838–1846. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kyriakopoulou CB, Nordvarg H, Virtanen A. A novel nuclear human poly(A) polymerase (PAP), PAP gamma. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:33504–33511. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M104599200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhelkovsky A, Helmling S, Moore C. Processivity of the Saccharomyces cerevisiae poly(A) polymerase requires interactions at the carboxyl-terminal RNA binding domain. Molecular and cellular biology. 1998;18:5942–5951. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.10.5942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rose KM, Bell LE, Jacob ST. Specific inhibition of chromatin-associated poly(A) synthesis in vitro by cordycepin 5′-triphosphate. Nature. 1977;267:178–180. doi: 10.1038/267178a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lingner J, Kellermann J, Keller W. Cloning and expression of the essential gene for poly(A) polymerase from S. cerevisiae. Nature. 1991;354:496–498. doi: 10.1038/354496a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Martin G, Keller W. Tailing and 3′-end labeling of RNA with yeast poly(A) polymerase and various nucleotides. RNA. 1998;4:226–230. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ghoshal K, Jacob ST. Ara-ATP impairs 3′-end processing of pre-mRNAs by inhibiting both cleavage and polyadenylation. Nucleic Acids Res. 1991;19:5871–5875. doi: 10.1093/nar/19.21.5871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Martin G, Moeglich A, Keller W, Doublie S. Biochemical and Structural Insights into Substrate Binding and Catalytic Mechanism of Mammalian Poly(A) Polymerase. J Mol Biol. 2004;341:911–925. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.06.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Balbo PB, Bohm A. Mechanism of poly(A) polymerase: structure of the enzyme-MgATP-RNA ternary complex and kinetic analysis. Structure. 2007;15:1117–1131. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2007.07.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hoffman MA, Janson D, Rose E, Rai KR. Treatment of hairy-cell leukemia with cladribine: response, toxicity, and long-term follow-up. J Clin Oncol. 1997;15:1138–1142. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1997.15.3.1138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Seto S, Carrera CJ, Kubota M, Wasson DB, Carson DA. Mechanism of deoxyadenosine and 2-chlorodeoxyadenosine toxicity to nondividing human lymphocytes. J Clin Invest. 1985;75:377–383. doi: 10.1172/JCI111710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Carson DA, Wasson DB, Taetle R, Yu A. Specific toxicity of 2-chlorodeoxyadenosine toward resting and proliferating human lymphocytes. Blood. 1983;62:737–743. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hentosh P, Koob R, Blakley RL. Incorporation of 2-halogeno-2′-deoxyadenosine 5-triphosphates into DNA during replication by human polymerases alpha and beta. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:4033–4040. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Griffig J, Koob R, Blakley RL. Mechanisms of inhibition of DNA synthesis by 2-chlorodeoxyadenosine in human lymphoblastic cells. Cancer Res. 1989;49:6923–6928. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Parker WB, Bapat AR, Shen JX, Townsend AJ, Cheng YC. Interaction of 2-halogenated dATP analogs (fluoride, chloride, and bromide) with human DNA polymerases, DNA primase, and ribonucleotide reductase. Mol Pharmacol. 1988;34:485–491. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Van Den Neste E, Cardoen S, Husson B, Rosier JF, Delacauw A, Ferrant A, Van den Berghe G, Bontemps F. 2-Chloro-2′-deoxyadenosine inhibits DNA repair synthesis and potentiates UVC cytotoxicity in chronic lymphocytic leukemia B lymphocytes. Leukemia. 2002;16:36–43. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2402331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pettitt AR, Clarke AR, Cawley JC, Griffiths SD. Purine analogues kill resting lymphocytes by p53-dependent and -independent mechanisms. Brit J Haematol. 1999;105:986–988. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.1999.01448.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pettitt AR, Sherrington PD, Cawley JC. The effect of p53 dysfunction on purine analogue cytotoxicity in chronic lymphocytic leukaemia. Brit J Haematol. 1999;106:1049–1051. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.1999.01649.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Genini D, Adachi S, Chao Q, Rose DW, Carrera CJ, Cottam HB, Carson DA, Leoni LM. Deoxyadenosine analogs induce programmed cell death in chronic lymphocytic leukemia cells by damaging the DNA and by directly affecting the mitochondria. Blood. 2000;96:3537–3543. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Genini D, Budihardjo I, Plunkett W, Wang X, Carrera CJ, Cottam HB, Carson DA, Leoni LM. Nucleotide requirements for the in vitro activation of the apoptosis protein-activating factor-1-mediated caspase pathway. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:29–34. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.1.29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Leoni LM, Chao Q, Cottam HB, Genini D, Rosenbach M, Carrera CJ, Budihardjo I, Wang X, Carson DA. Induction of an apoptotic program in cell-free extracts by 2-chloro-2′-deoxyadenosine 5′-triphosphate and cytochrome c. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:9567–9571. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.16.9567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hentosh P, Tibudan M. In vitro transcription of DNA containing 2-chloro-2′-deoxyadenosine monophosphate. Mol Pharmacol. 1995;48:897–904. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Albertioni F, Lindemalm S, Reichelova V, Pettersson B, Eriksson S, Juliusson G, Liliemark J. Pharmacokinetics of cladribine in plasma and its 5′-monophosphate and 5′-triphosphate in leukemic cells of patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Clin Cancer Res. 1998;4:653–658. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Plunkett W, Gandhi V, Huang P, Robertson LE, Yang LY, Gregoire V, Estey E, Keating MJ. Fludarabine: pharmacokinetics, mechanisms of action, and rationales for combination therapies. Seminars in Oncology. 1993;20:2–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Huang P, Chubb S, Plunkett W. Termination of DNA synthesis by 9-b-D-arabinofuranosyl-2-fluoroadenine. A mechanism for cytotoxicity. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:16617–16625. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tseng WC, Derse D, Cheng YC, Brockman RW, Bennett LL., Jr In vitro biological activity of 9-b-D-arabinofuranosyl-2-fluoroadenine and the biochemical actions of its triphosphate on DNA polymerases and ribonucleotide reductase from HeLa cells. Mol Pharmacol. 1982;21:474–477. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Huang P, Plunkett W. Action of 9-b-D-arabinofuranosyl-2-fluoroadenine on RNA metabolism. Mol Pharmacol. 1991;39:449–455. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Danhauser L, Plunkett W, Keating M, Cabanillas F. 9-beta-D-arabinofuranosyl-2-fluoroadenine 5′-monophosphate pharmacokinetics in plasma and tumor cells of patients with relapsed leukemia and lymphoma. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 1986;18:145–152. doi: 10.1007/BF00262285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gottardi D, De Leo AM, Alfarano A, Stacchini A, Circosta P, Gregoretti MG, Bergui L, Aragno M, Caligaris-Cappio F. Fludarabine ability to down-regulate Bcl-2 gene product in CD5+ leukemic B cells: in vitro/in vivo correlations. Brit J Haematol. 1997;99:147–157. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.1997.3353152.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Xie C, Plunkett W. Metabolism and actions of 2-chloro-9-(2-deoxy-2-fluoro-beta-D-arabinofuranosyl)-adenine in human lymphoblastoid cells. Cancer Res. 1995;55:2847–2852. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Parker WB, Shaddix SC, Chang CH, White EL, Rose LM, Brockman RW, Shortnacy AT, Montgomery JA, Secrist JA, 3rd, Bennett LL., Jr Effects of 2-chloro-9-(2-deoxy-2-fluoro-beta-D-arabinofuranosyl)adenine on K562 cellular metabolism and the inhibition of human ribonucleotide reductase and DNA polymerases by its 5′-triphosphate. Cancer Res. 1991;51:2386–2394. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gandhi V, Kantarjian H, Faderl S, Bonate P, Du M, Ayres M, Rios MB, Keating MJ, Plunkett W. Pharmacokinetics and Pharmacodynamics of Plasma Clofarabine and Cellular Clofarabine Triphosphate in Patients with Acute Leukemias. Clin Cancer Res. 2003;9:6335–6342. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kantarjian H, Gandhi V, Cortes J, Verstovsek S, Du M, Garcia-Manero G, Giles F, Faderl S, O’Brien S, Jeha S, Davis J, Shaked Z, Craig A, Keating M, Plunkett W, Freireich EJ. Phase 2 clinical and pharmacologic study of clofarabine in patients with refractory or relapsed acute leukemia. Blood. 2003;102:2379–2386. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-03-0925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]