Abstract

An increasing number of studies have implicated that the activation of innate immune system and inflammatory mechanisms are of importance in the pathogenesis of numerous diseases. The innate immune system is present in almost all multicellular organisms in response to pathogens or tissue injury, which is performed via germ-line encoded pattern-recognition receptors (PRRs) to recognize pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) or dangers-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs). Intracellular pathways linking immune and inflammatory response to ion channel expression and function have been recently identified. Among ion channels, transient receptor potential (TRP) channels are a major family of non-selective cation-permeable channels that function as polymodal cellular sensors involved in many physiological and pathological processes. In this review, we summarize current knowledge about classifications, functions, and interactions of TRP channels and PRRs, which may provide new insights into their roles in the pathogenesis of inflammatory diseases.

Keywords: TRP channels, immune homeostasis, inflammation, Ca2+ influx, NLR, TLR

Introduction

The activation of innate immune system and inflammatory mechanisms are of importance in the pathogenesis of numerous diseases. The innate immune system is the first line of defense against pathogens and tissue injury, which is responsible for initiating immune responses to resolve infections and repair damaged tissues. Initiation of the innate immune response is triggered by recognition of pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) or danger-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs) by pathogen recognition receptors (PRRs).1 Engagement of PRRs by PAMPs and DAMPs leads to a multitude of changes in the transcriptional and posttranslational cascades of innate immune cells that bring proinflammatory cytokines, chemokines, and growth factors into circulation.2 Intracellular pathways linking immune and inflammatory response to ion channels have been identified.3,4 Among ion channels, transient receptor potential (TRP) channels are a major family of non-selective cation-permeable channels, which are classified into 6 subfamilies on the basis of sequence homology and function as diverse cellular sensors.5 There are strong indications that TRP channels are involved in the pathogenesis of many inflammatory diseases.6 This brief review summarizes current evidence that relates to the interactions of PRRs and TRP channels, which may provide new insights into their roles and regulatory mechanisms.

Transient Receptor Potential Channels: Classification and Function

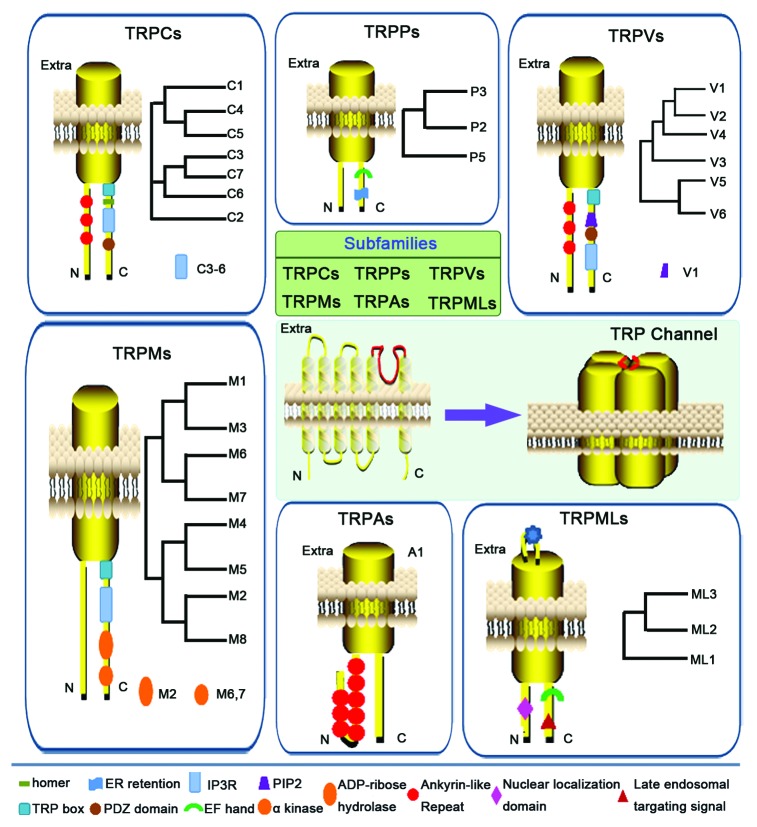

Transient receptor potential (TRP) channels are a family of non-selective cation-permeable channels that function as polymodal cellular sensors involved in many physiological processes.7 Mutations in genes encoding TRP channels have been demonstrated to be the cause of several inherited diseases that affect a variety of systems including the renal, skeletal, and nervous system.4,6,8 As shown in Figure 1, all TRP channels are membrane proteins with 6 putative transmembrane segments (S1–S6) and a cation-permeable pore region between S5 and S6. Currently, 28 different mammalian TRP channels are identified and classified into 6 subfamilies on the basis of sequence homology: TRP canonical (TRPC; TRPC1–7), TRP vanilloid (TRPV; TRPV1–6), TRP melastatin (TRPM; TRPM1–8), TRP polycystin (TRPP; TRPP2, TRPP3, TRPP5), TRP mucolipin (TRPML; TRPML1–3), and TRP ankyrin (TRPA; TRPA1).6,9 Different subfamilies of TRP channels display a variety of gating mechanism and cation selectivity,10,11 which can be opened by direct ligand binding, G-protein coupled signaling, or membrane depolarization.12,13 TRPC channels consist of the proteins closely related to the first identified member of TRP channels, the “canonical” Drosophila TRP, now named as TRPC1. Functionally, TRPC family has been implicated in a diverse set of diseases such as hypertension, vascular inflammation, cardiac hypertrophy, and progressive kidney failure. The mammalian TRPV channels are thermo- and chemosensitive channels which are composed of 6 members.14 TRPV1 is the best characterized member of TRPVs, which can be activated by a diverse range of stimuli, including membrane depolarization, noxious heat, vanilloid and endocannabinoid compounds, extracellular protons, and inflammatory mediators. It has been shown that TRPV1 plays a pivotal role in pain and neurogenic inflammation.15 TRPM channels exhibit highly variable permeability to Ca2+ and Mg2+, ranging from Ca2+ impermeable (TRPM4 and TRPM5) to highly Ca2+ and Mg2+ permeable (TRPM6 and TRPM7).16,17 Although TRPMs have not yet been fully functionally characterized, TRPM1 appears to function as a tumor suppressor and TRPM3 is considered as a possible candidate gene involved in the etiology of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS).18,19 The TRPML subfamily consists of 3 members, which are primarily intracellular proteins in cytosolic compartments20,21 and characterized by a large E1 loop (between S1 and S2) with several N-glycosilation sites. All TRPMLs have short cytosolic tails (between 61 to 72 amino acids) with a palmitoylation site in a cysteine-rich region.21,22 TRPP subfamily has 3 members, TRPP2, TRPP3, and TRPP5 (also named as PKD2, PKD2L1, and PKD2L2, respectively), mutations in Trpp2 and PKD1 lead to autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease.23 The only member of the TRPA subfamily TRPA1 has recently emerged as another potential therapeutic target in the treatment of chronic visceral inflammation and pain except for TRPV1. Meanwhile, the role of TRPA1 in gastrointestinal inflammatory disorders is becoming increasingly clear.24 Although connections of TRP channels to a plethora of diseases are well documented, the regulatory mechanisms of TRP channels and their effects on particulars of Ca2+ homeostasis and cellular functions are not well understood. This review focuses on the aspects of interactions between TRP channels and PRRs in mediating the immune and inflammatory responses.

Figure 1. Classification and structural topology of transient receptor potential (TRP) channels. All TRP channels are membrane proteins with 6 putative transmembrane segments (S1–S6) and a cation-permeable pore region between S5 and S6. The cytoplasmic amino (N) and carboxy (C) termini are variable in length and contain different domains. Currently, 28 different mammalian TRP channels are identified and classified into 6 subfamilies on the basis of sequence homology: TRP canonical (TRPC; TRPC1–7), TRP vanilloid (TRPV; TRPV1–6), TRP melastatin (TRPM; TRPM1–8), TRP polycystin (TRPP; TRPP2, TRPP3, TRPP5), TRP mucolipin (TRPML; TRPML1–3), and TRP ankyrin (TRPA; TRPA1).

Innate Immune Receptors: Classification and Function

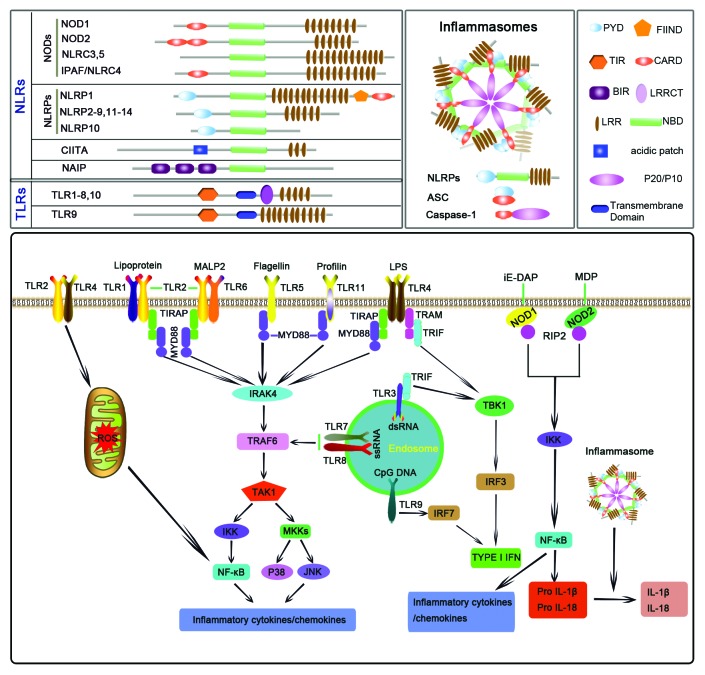

The innate immune response is initiated through the activation of PRRs by PAMPs or DAMPs. Currently, 4 major classes of PRRs have been identified consisting of transmembrane proteins such as the Toll-like receptors (TLRs) and C-type lectin receptors (CLRs), as well as cytoplasmic proteins such as the Retinoic acid-inducible gene (RIG)-I-like receptors (RLRs) and NOD-like receptors (NLRs).25 Among them, TLRs and NLRs are 2 major subfamilies of PRRs, which provide immediate responses against pathogenic invasion or tissue injury.1,26,27 TLRs, the first identified PRRs, are type I transmembrane proteins with an extracellular or luminal binding domain composed of leucine-rich repeats (LRRs) and intracellular Toll–interleukin 1 (IL-1) receptor (TIR) domains required for downstream signal transductions.28,29 TLRs are normally divided into 2 major subgroups based on their cellular localization and PAMP ligands.30 TLR3, TLR7, TLR8, and TLR9 detect virus-derived ssRNA or dsRNA and are located in intracellular vesicles such as the endoplasmic reticulum (ER), endosomes and lysosomes. Conversely, TLR1, TLR2, TLR4, TLR5, and TLR6 are located on the cell surface and can sense various PAMPs, including lipopolysaccharide (LPS)4, peptidoglycan, bacterial flagellum, and fungal cell wall components.31,32 As shown in Figure 2, upon activation, TLRs recruit a specific set of adaptor molecules that harbor TIR domain, such as MyD88 and TIR-domain-containing adaptor inducing IFN-β (TRIF), and initiate downstream signaling events, thereby lead to the secretion of proinflammatory mediators.33 In addition, TLR signaling simultaneously induces maturation of dendritic cells (DCs), which is responsible for the induction of adaptive immunity.30

Figure 2. Classification, activation and function of Toll-like receptors (TLRs) and NOD-like receptors (NLRs). TLRs are transmembrane proteins with an extracellular or luminal binding domain composed of leucine-rich repeats (LRRs) and intracellular Toll–interleukin 1 (IL-1) receptor (TIR) domains required for downstream signal transduction. NLRs share highly conserved structures consisting of (1) a centrally located, conservative nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain (NBD) that mediates self-oligomerization and is essential for the activation of NLRs, (2) a C-terminal leucine-rich repeat (LRR) domain that is involved in recognition of conserved microbial patterns or other ligands, and (3) a N-terminal effector domain, which is responsible for protein–protein interaction with adaptor molecules that result in signal transduction. Inflammasomes are a subfamily of NLR protein complexes that recognize a diverse set of inflammation-inducing stimuli and that control the production of important proinflammatory cytokines such as IL-1β and IL-18.

The NLR family of intracellular PRRs has recently been identified and plays a critical role in the control of inflammatory and immune responses through the modulation of different signaling pathways, including those dependent on NF-κB and caspase-1-mediated cleavage of IL-1β and IL-18.34 NLR proteins share highly conserved structures29,35and are divided into several subfamilies based on the nature of their N-terminal domains (Fig. 2).36 NOD1 and NOD2 are 2 well-characterized members of noninflammasome NLRs, which mediate the activation of NF-κB and mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPKs) in response to peptidoglycan-related molecules.37 In dendritic cells, macrophages, and monocytes, activation of NODs leads mainly to the production of proinflammatory cytokines and expression of co-stimulatory molecules and adhesion molecules.38 In addition to being present in inflammatory cells, studies from our laboratory and by others have found that NOD2 is also highly expressed in the kidney including renal proximal tubule epithelial cells39 and glomerular cells69 and cardiovascular system including vascular smooth muscle cells40 and endothelial cells.41

Inflammasomes are a subfamily of NLR protein complexes that control the production of proinflammatory cytokines such as IL-1β and IL-18.42 Furthermore, they have been found to regulate other important aspects of inflammation and tissue repair such as pyroptosis, a form of cell death.43 Among the NLRs, NLRP1, NLRP3, NLRP6, NLRP12, and IPAF have been identified to assemble into inflammasomes. The inflammasome is composed of the intracellular adaptor protein ASC (apoptosis-associated speck-like protein containing a CARD) and a “sensor NLR” that function as molecular scaffolds for the activation of caspase-1 to secrete IL-1β and IL-18.44 The NLRP3 inflammasome is one of the most extensively studied NLR members and is activated by a wide range of signals of pathogenic, endogenous, and environmental origin.45,46 In addition, NLRP3 is also alerted to the presence of endogenous danger signal molecules released during or indicative of tissue injury, such as extracellular ATP, hyaluronan, amyloid-β fibrils, and uric acid crystals.47 Currently, 3 distinct mechanisms have been proposed to account for NLRP3 activation: potassium efflux,48,49 the generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS),50 and phagolysosomal destabilization.42,43,51 Except for the critical role of NLRP3 in common autoimmune diseases, more recent studies have indicated that NLRP3 inflammasome contributes to the regulation of insulin signaling,52 and the pathogenesis of atherosclerosis,51 myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury,53 and neurodegeneration.43,54 In this review, we describe recent findings of the interactions between PRRs and TRP channels.

TLR-Mediated Inflammatory Response is Associated with TRP Channel-Dependent Ca2+ Signaling

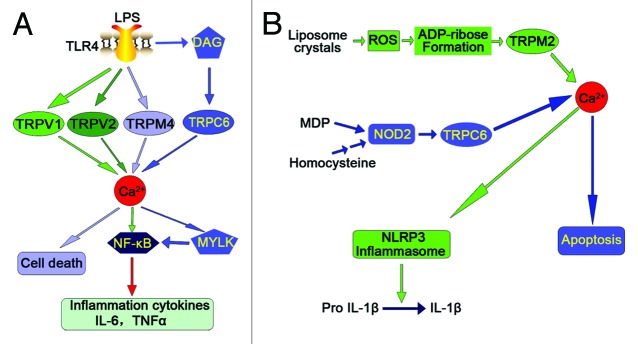

There is considerable evidence indicating that intracellular Ca2+ as a second messenger participates in TLR4-dependent signaling. However, how intracellular Ca2+ is increased in response to LPS and how they affect inflammatory response is poorly understood. An increasing number of studies have indicated that TLR-mediated immune response is associated with TRP channel-dependent Ca2+ signaling (Fig. 3A). Studies from Tauseef M et al. have identified a function of TRPC6 in endothelial cells showing that TRPC6-dependent Ca2+ signaling intersects with the TLR4 signaling pathway and hence contributes to LPS-induced lung endothelial permeability and NF-κB–dependent lung inflammation.55 They found that LPS induces Ca2+ entry in endothelial cells in a TLR4-dependent manner and deletion of TRPC6 renders mice resistant to this endotoxin-induced barrier dysfunction and inflammation, and protects against sepsis-induced lethality. Furthermore, they showed that LPS induces the production of the second messenger DAG in endothelial cells, which directly activates TRPC6 in a TLR4-dependent manner. TRPC6-mediated Ca2+ entry in turn activates myosin light chain kinase (MYLK), a regulator of endothelial contractility, resulting in LPS/TLR4-mediated NF-κB activation and contributing to the mechanism of lung inflammation.55 In addition to TRPC6, recent studies have also observed other TRP channels in mediating LPS-induced signaling pathways. A report has shown that LPS binds to receptors in trigeminal neurons and evoked a concentration-dependent increase in intracellular Ca2+ and inward currents. Furthermore, they found that LPS significantly sensitizes TRPV1 to capsaicin which is blocked by a selective TLR4 antagonist, indicating that LPS is capable of directly activating trigeminal neurons, and sensitizing TRPV1 via a TLR4-mediated mechanism.56 Recent studies by Yamashiro et al. have shown that TRPV2, but not members of the TRPC or TRPM families, mediates intracellular Ca2+ mobilization, which is involved in LPS-induced TNF-α and IL-6 expression in NF-κB-dependent manner in RAW264 macrophage.57 Because in these cells LPS acts through TLR4, it is tempting to speculate on a role of TRPV2 in modulating TLR4-dependent signaling in macrophages. Among TRPMs, TRPM4 has been demonstrated to be critically involved in LPS-induced endothelial cell death and inhibition of TRPM4 activity protects endothelium against LPS injury58 suggesting that the effects of LPS are, at least in part, associated with TRPM4 signaling.

Figure 3. Summarized recent findings of the interactions between pattern-recognition receptors (PRRs) and transient receptor potential (TRP) channels. (A) TLR-mediated inflammatory response is associated with TRP channel-dependent Ca2+ signaling. (B) TRP channel-dependent Ca2+ signaling intersects with NLR signaling pathways.

TRP Channel-Dependent Ca2+ Signaling Intersects with NLR-Signaling Pathways

Although hyperhomocysteinemia (hHcys) has been recognized as an important independent risk factor in the progression of end-stage renal disease (ESRD) and in the development of cardiovascular complications related to ESRD,59-61 the mechanisms triggering the pathogenic actions of hHcys are not yet fully understood. Recent studies from our laboratory investigated the contribution of NOD2 to the development of glomerulosclerosis in hHcys. Our results showed that NOD2 deficiency ameliorates renal injury in mice with hHcys. We further found that NOD2 induces TRPC6 expression and activity, leading to intracellular Ca2+ release, ultimately results in podocyte cytoskeleton rearrangement and apoptosis (Fig. 3B). This study for the first time establishes a previously unknown function of NOD2 for the regulation of TRPC6 channels, suggesting that TRPC6-dependent Ca2+ signaling is one of critical signal transduction pathways that links innate immunity mediator NOD2 to podocyte injury.62 In addition, TRPC6 has been linked to hypertension, cardiac hypertrophy, cardiac fibrosis, and neuronal degeneration. Therefore, pharmacological targeting of NOD2-mediated TRPC6 signaling pathways at multiple levels may help design a new approach to develop therapeutic strategies for prevention and the treatment of hHcys-associated end-organ damage.

On the contrary, TRPM2-mediated calcium mobilization can also induce NLRP3 inflammasome activation as shown in Figure 3B.63 Although reactive oxygen species (ROS) have a central role in NLRP3 inflammasome activation, how ROS signal assembly of the NLRP3 inflammasome remains elusive. It has been shown that accumulation of ROS can induce a calcium influx via the TRPM2 channel.64,65 TRPM2 is an oxidant-activated nonselective cation channel that is widely expressed in mammalian tissues and immune cells and plays a crucial role in innate immune regulation.66 TRPM2-mediated calcium influx has been implicated in ROS-induced chemokine production in monocytes.65 ROS stimulates intracellular ADP-ribose formation which, in turn, opens TRPM2 channels. These channels act as an endogenous redox sensor for mediating ROS-induced Ca2+ entry and the subsequent specific Ca2+-dependent cellular reactions such as endothelial hyper-permeability and apoptosis and inflammatory neutrophil infiltration.64,65 Zhong et al. have identified liposomes as novel activators of the NLRP3 inflammasome and further demonstrated that liposome-induced inflammasome activation also requires mitochondrial ROS. Moreover, they found that stimulation with liposomes/crystals induces ROS-dependent calcium influx via the TRPM2 channel, macrophages deficient in TRPM2 drastically impair NLRP3 inflammasome activation and IL-1β secretion.63 In addition, TRPM2 channel has been demonstrated to be required for innate immunity against Listeria monocytogenes, a known activator of the NLRP3 inflammasome.67-69 Collectively, these results indicate that TRPM2 as a key factor that links oxidative stress to the NLRP3 inflammasome activation and targeting TRPM2 may be effective for the treatment of NLRP3 inflammasome-associated inflammatory disorders.

Concluding Remarks

Despite remarkable progress in TRP channels and PRRs, there are still numerous aspects of their activation that need to be understood. In particular, the importance of TRP channel and PRR interactions has just started to be elucidated. Therefore, understanding the interactions of the TRP channel and PRR pathways will provide new insights into their roles in the pathogeneses of inflammatory diseases which are involved in the changes in ion transport.

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by grants from by the National 973 Basic Research Program of China (2012CB517700), The National Nature Science Foundation of China (81170772, 81070572, and 81328006), The Shandong Natural Science Fund for Distinguished Young Scholars (JQ201121) to F.Y., Foundation of Program for New Century Excellent Talents in University (NCET-11-0311) to F.Y., and The Nature Science Foundation of Shandong Province (ZR2012HM035).

Glossary

Abbreviations:

- ALS

amyotrophic lateral sclerosis

- ASC

apoptosis-associated speck-like protein containing a CARD

- BIR

baculovirus inhibition of apoptosis protein repeat

- CARD

caspase-recruiting domain

- CIITA

class II transactivator

- CLRs

C-type lectin receptors

- DAG

diacylglycerol

- ER

endoplasmic reticulum

- FIIND

function to find domain

- Hcys

homocysteine

- IRF

IFN regulatory factor

- LPS

lipopolysaccharide

- LRRs

leucine-rich repeats

- LRRCT

leucine-rich repeat C-terminal

- MAPK

mitogen-activated protein kinase

- MDP

muramyl dipeptide

- MKKs

MAPK kinases

- MYD88

myeloid differentiation factor 88

- MYLK

myosin light chain kinase

- NAIP

NLR apoptosis inhibitory protein

- NBD

nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain

- NLRs

NOD-like receptors

- NLRPs

NOD-like receptor pyrin domain containing

- NODs

nucleotide binding and oligomerization domain-containing proteins

- PYD

pyrin domain

- RIG

Retinoic acid-inducible gene

- RIP2

receptor-interacting protein 2

- ROS

reactive oxygen species

- TAK1

TGF-β-activated kinase 1

- TBK1

TANK-binding kinase 1

- TIR

Toll–interleukin 1 (IL-1) receptor

- TIRAP

TIR domain–containing adapter protein

- TLRs

Toll-like receptors

- TRAF6

TNF receptor-associated factor 6

- TRAM

TRIF-related adaptor molecule

- TRIF

TIR-domain-containing adaptor inducing IFN-β

- TRP

transient receptor potential

- TRPA

TRP ankyrin

- TRPC

TRP canonical

- TRPM

TRP melastatin

- TRPP

TRP polycystin

- TRPPM

TRP mucolipin

- TRPV

TRP vanilloid

References

- 1.Fukata M, Vamadevan AS, Abreu MT. Toll-like receptors (TLRs) and Nod-like receptors (NLRs) in inflammatory disorders. Semin Immunol. 2009;21:242–53. doi: 10.1016/j.smim.2009.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lamkanfi M, Dixit VM. Inflammasomes and their roles in health and disease. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2012;28:137–61. doi: 10.1146/annurev-cellbio-101011-155745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cahalan MD, Chandy KG. The functional network of ion channels in T lymphocytes. Immunol Rev. 2009;231:59–87. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2009.00816.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nilius B, Owsianik G. The transient receptor potential family of ion channels. Genome Biol. 2011;12:218. doi: 10.1186/gb-2011-12-3-218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lev S, Katz B, Minke B. The activity of the TRP-like channel depends on its expression system. Channels (Austin) 2012;6:86–93. doi: 10.4161/chan.19946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nilius B, Owsianik G. Transient receptor potential channelopathies. Pflugers Arch. 2010;460:437–50. doi: 10.1007/s00424-010-0788-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Majhi R, Sardar P, Goswami L, Goswami C. Right time - right location - right move: TRPs find motors for common functions. Channels (Austin) 2011;5:375–81. doi: 10.4161/chan.5.4.16969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Moran MM, McAlexander MA, Bíró T, Szallasi A. Transient receptor potential channels as therapeutic targets. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2011;10:601–20. doi: 10.1038/nrd3456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tano JY, Lee RH, Vazquez G. Macrophage function in atherosclerosis: potential roles of TRP channels. Channels (Austin) 2012;6:141–8. doi: 10.4161/chan.20292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vennekens R. Emerging concepts for the role of TRP channels in the cardiovascular system. J Physiol. 2011;589:1527–34. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2010.202077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Maroto R, Kurosky A, Hamill OP. Mechanosensitive Ca(2+) permeant cation channels in human prostate tumor cells. Channels (Austin) 2012;6:290–307. doi: 10.4161/chan.21063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kim H, Kim J, Jeon J-P, Myeong J, Wie J, Hong C, Kim HJ, Jeon JH, So I. The roles of G proteins in the activation of TRPC4 and TRPC5 transient receptor potential channels. Channels (Austin) 2012;6:333–43. doi: 10.4161/chan.21198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ahmmed GU, Malik AB. Functional role of TRPC channels in the regulation of endothelial permeability. Pflugers Arch. 2005;451:131–42. doi: 10.1007/s00424-005-1461-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Woudenberg-Vrenken TE, Bindels RJ, Hoenderop JG. The role of transient receptor potential channels in kidney disease. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2009;5:441–9. doi: 10.1038/nrneph.2009.100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.White JP, Urban L, Nagy I. TRPV1 function in health and disease. Curr Pharm Biotechnol. 2011;12:130–44. doi: 10.2174/138920111793937844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chubanov V, Waldegger S, Mederos y Schnitzler M, Vitzthum H, Sassen MC, Seyberth HW, Konrad M, Gudermann T. Disruption of TRPM6/TRPM7 complex formation by a mutation in the TRPM6 gene causes hypomagnesemia with secondary hypocalcemia. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:2894–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0305252101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chubanov V, Mederos y Schnitzler M, Wäring J, Plank A, Gudermann T. Emerging roles of TRPM6/TRPM7 channel kinase signal transduction complexes. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol. 2005;371:334–41. doi: 10.1007/s00210-005-1056-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lee N, Chen J, Sun L, Wu S, Gray KR, Rich A, Huang M, Lin JH, Feder JN, Janovitz EB, et al. Expression and characterization of human transient receptor potential melastatin 3 (hTRPM3) J Biol Chem. 2003;278:20890–7. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M211232200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nilius B, Voets T, Peters J. TRP channels in disease. Sci STKE. 2005;2005:re8. doi: 10.1126/stke.2952005re8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Curcio-Morelli C, Zhang P, Venugopal B, Charles FA, Browning MF, Cantiello HF, Slaugenhaupt SA. Functional multimerization of mucolipin channel proteins. J Cell Physiol. 2010;222:328–35. doi: 10.1002/jcp.21956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Venkatachalam K, Hofmann T, Montell C. Lysosomal localization of TRPML3 depends on TRPML2 and the mucolipidosis-associated protein TRPML1. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:17517–27. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M600807200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Grimm C, Jörs S, Guo Z, Obukhov AG, Heller S. Constitutive activity of TRPML2 and TRPML3 channels versus activation by low extracellular sodium and small molecules. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:22701–8. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.368876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tsiokas L. Function and regulation of TRPP2 at the plasma membrane. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2009;297:F1–9. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.90277.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lapointe TK, Altier C. The role of TRPA1 in visceral inflammation and pain. Channels (Austin) 2011;5:525–9. doi: 10.4161/chan.5.6.18016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Takeuchi O, Akira S. Pattern recognition receptors and inflammation. Cell. 2010;140:805–20. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.01.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bradbury J. Zebularine: a candidate for epigenetic cancer therapy. Drug Discov Today. 2004;9:906–7. doi: 10.1016/S1359-6446(04)03266-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Walsh D, McCarthy J, O’Driscoll C, Melgar S. Pattern recognition receptors--molecular orchestrators of inflammation in inflammatory bowel disease. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2013;24:91–104. doi: 10.1016/j.cytogfr.2012.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kawai T, Akira S. The role of pattern-recognition receptors in innate immunity: update on Toll-like receptors. Nat Immunol. 2010;11:373–84. doi: 10.1038/ni.1863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Carneiro LA, Magalhaes JG, Tattoli I, Philpott DJ, Travassos LH. Nod-like proteins in inflammation and disease. J Pathol. 2008;214:136–48. doi: 10.1002/path.2271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kawai T, Akira S. Toll-like receptors and their crosstalk with other innate receptors in infection and immunity. Immunity. 2011;34:637–50. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2011.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Brown J, Wang H, Hajishengallis GN, Martin M. TLR-signaling networks: an integration of adaptor molecules, kinases, and cross-talk. J Dent Res. 2011;90:417–27. doi: 10.1177/0022034510381264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jacobs SR, Damania B. NLRs, inflammasomes, and viral infection. J Leukoc Biol. 2012;92:469–77. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0312132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Blasius AL, Beutler B. Intracellular toll-like receptors. Immunity. 2010;32:305–15. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2010.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Saleh M. The machinery of Nod-like receptors: refining the paths to immunity and cell death. Immunol Rev. 2011;243:235–46. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2011.01045.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fritz JH, Ferrero RL, Philpott DJ, Girardin SE. Nod-like proteins in immunity, inflammation and disease. Nat Immunol. 2006;7:1250–7. doi: 10.1038/ni1412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kersse K, Bertrand MJ, Lamkanfi M, Vandenabeele P. NOD-like receptors and the innate immune system: coping with danger, damage and death. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2011;22:257–76. doi: 10.1016/j.cytogfr.2011.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Inohara N, Chamaillard M, McDonald C, Nuñez G. NOD-LRR proteins: role in host-microbial interactions and inflammatory disease. Annu Rev Biochem. 2005;74:355–83. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.74.082803.133347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Elinav E, Strowig T, Henao-Mejia J, Flavell RA. Regulation of the antimicrobial response by NLR proteins. Immunity. 2011;34:665–79. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2011.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shigeoka AA, Kambo A, Mathison JC, King AJ, Hall WF, da Silva Correia J, Ulevitch RJ, McKay DB. Nod1 and nod2 are expressed in human and murine renal tubular epithelial cells and participate in renal ischemia reperfusion injury. J Immunol. 2010;184:2297–304. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0903065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kwon MY, Liu X, Lee SJ, Kang YH, Choi AM, Lee KU, Perrella MA, Chung SW. Nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain protein 2 deficiency enhances neointimal formation in response to vascular injury. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2011;31:2441–7. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.111.235135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Madrigal AG, Barth K, Papadopoulos G, Genco CA. Pathogen-mediated proteolysis of the cell death regulator RIPK1 and the host defense modulator RIPK2 in human aortic endothelial cells. PLoS Pathog. 2012;8:e1002723. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Schroder K, Tschopp J. The inflammasomes. Cell. 2010;140:821–32. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.01.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Strowig T, Henao-Mejia J, Elinav E, Flavell R. Inflammasomes in health and disease. Nature. 2012;481:278–86. doi: 10.1038/nature10759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wilson AJ, Cheng YQ, Khabele D. Thailandepsins are new small molecule class I HDAC inhibitors with potent cytotoxic activity in ovarian cancer cells: a preclinical study of epigenetic ovarian cancer therapy. J Ovarian Res. 2012;5:12. doi: 10.1186/1757-2215-5-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rathinam VA, Vanaja SK, Fitzgerald KA. Regulation of inflammasome signaling. Nat Immunol. 2012;13:333–2. doi: 10.1038/ni.2237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bauernfeind F, Ablasser A, Bartok E, Kim S, Schmid-Burgk J, Cavlar T, Hornung V. Inflammasomes: current understanding and open questions. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2011;68:765–83. doi: 10.1007/s00018-010-0567-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Cassel SL, Eisenbarth SC, Iyer SS, Sadler JJ, Colegio OR, Tephly LA, Carter AB, Rothman PB, Flavell RA, Sutterwala FS. The Nalp3 inflammasome is essential for the development of silicosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:9035–40. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0803933105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Pétrilli V, Papin S, Dostert C, Mayor A, Martinon F, Tschopp J. Activation of the NALP3 inflammasome is triggered by low intracellular potassium concentration. Cell Death Differ. 2007;14:1583–9. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4402195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Arlehamn CS, Pétrilli V, Gross O, Tschopp J, Evans TJ. The role of potassium in inflammasome activation by bacteria. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:10508–18. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.067298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sorbara MT, Girardin SE. Mitochondrial ROS fuel the inflammasome. Cell Res. 2011;21:558–60. doi: 10.1038/cr.2011.20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Duewell P, Kono H, Rayner KJ, Sirois CM, Vladimer G, Bauernfeind FG, Abela GS, Franchi L, Nuñez G, Schnurr M, et al. NLRP3 inflammasomes are required for atherogenesis and activated by cholesterol crystals. Nature. 2010;464:1357–61. doi: 10.1038/nature08938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Vandanmagsar B, Youm YH, Ravussin A, Galgani JE, Stadler K, Mynatt RL, Ravussin E, Stephens JM, Dixit VD. The NLRP3 inflammasome instigates obesity-induced inflammation and insulin resistance. Nat Med. 2011;17:179–88. doi: 10.1038/nm.2279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Grundmann S, Bode C, Moser M. Inflammasome activation in reperfusion injury: friendly fire on myocardial infarction? Circulation. 2011;123:574–6. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.018176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Mathew A, Lindsley TA, Sheridan A, Bhoiwala DL, Hushmendy SF, Yager EJ, Ruggiero EA, Crawford DR. Degraded mitochondrial DNA is a newly identified subtype of the damage associated molecular pattern (DAMP) family and possible trigger of neurodegeneration. J Alzheimers Dis. 2012;30:617–27. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2012-120145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Tauseef M, Knezevic N, Chava KR, Smith M, Sukriti S, Gianaris N, Obukhov AG, Vogel SM, Schraufnagel DE, Dietrich A, et al. TLR4 activation of TRPC6-dependent calcium signaling mediates endotoxin-induced lung vascular permeability and inflammation. J Exp Med. 2012;209:1953–68. doi: 10.1084/jem.20111355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Diogenes A, Ferraz CC, Akopian AN, Henry MA, Hargreaves KM. LPS sensitizes TRPV1 via activation of TLR4 in trigeminal sensory neurons. J Dent Res. 2011;90:759–64. doi: 10.1177/0022034511400225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Yamashiro K, Sasano T, Tojo K, Namekata I, Kurokawa J, Sawada N, Suganami T, Kamei Y, Tanaka H, Tajima N, et al. Role of transient receptor potential vanilloid 2 in LPS-induced cytokine production in macrophages. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2010;398:284–9. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2010.06.082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Becerra A, Echeverría C, Varela D, Sarmiento D, Armisén R, Nuñez-Villena F, Montecinos M, Simon F. Transient receptor potential melastatin 4 inhibition prevents lipopolysaccharide-induced endothelial cell death. Cardiovasc Res. 2011;91:677–84. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvr135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Yi F, Xia M, Li N, Zhang C, Tang L, Li PL. Contribution of guanine nucleotide exchange factor Vav2 to hyperhomocysteinemic glomerulosclerosis in rats. Hypertension. 2009;53:90–6. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.108.115675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Yi F, Zhang AY, Li N, Muh RW, Fillet M, Renert AF, Li PL. Inhibition of ceramide-redox signaling pathway blocks glomerular injury in hyperhomocysteinemic rats. Kidney Int. 2006;70:88–96. doi: 10.1038/sj.ki.5001517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Yi F, Zhang AY, Janscha JL, Li PL, Zou AP. Homocysteine activates NADH/NADPH oxidase through ceramide-stimulated Rac GTPase activity in rat mesangial cells. Kidney Int. 2004;66:1977–87. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2004.00968.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Han H, Wang Y, Li X, Wang PA, Wei X, Liang W, Ding G, Yu X, Bao C, Zhang Y, et al. Novel role of NOD2 in mediating Ca2+ signaling: evidence from NOD2-regulated podocyte TRPC6 channels in hyperhomocysteinemia. Hypertension. 2013;62:506–11. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.113.01638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Zhong Z, Zhai Y, Liang S, Mori Y, Han R, Sutterwala FS, Qiao L. TRPM2 links oxidative stress to NLRP3 inflammasome activation. Nat Commun. 2013;4:1611. doi: 10.1038/ncomms2608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Hecquet CM, Malik AB. Role of H(2)O(2)-activated TRPM2 calcium channel in oxidant-induced endothelial injury. Thromb Haemost. 2009;101:619–25. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Yamamoto S, Shimizu S, Kiyonaka S, Takahashi N, Wajima T, Hara Y, Negoro T, Hiroi T, Kiuchi Y, Okada T, et al. TRPM2-mediated Ca2+influx induces chemokine production in monocytes that aggravates inflammatory neutrophil infiltration. Nat Med. 2008;14:738–47. doi: 10.1038/nm1758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Sumoza-Toledo A, Penner R. TRPM2: a multifunctional ion channel for calcium signalling. J Physiol. 2011;589:1515–25. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2010.201855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kim S, Bauernfeind F, Ablasser A, Hartmann G, Fitzgerald KA, Latz E, Hornung V. Listeria monocytogenes is sensed by the NLRP3 and AIM2 inflammasome. Eur J Immunol. 2010;40:1545–51. doi: 10.1002/eji.201040425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Mariathasan S, Weiss DS, Newton K, McBride J, O’Rourke K, Roose-Girma M, Lee WP, Weinrauch Y, Monack DM, Dixit VM. Cryopyrin activates the inflammasome in response to toxins and ATP. Nature. 2006;440:228–32. doi: 10.1038/nature04515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Knowles H, Heizer JW, Li Y, Chapman K, Ogden CA, Andreasen K, Shapland E, Kucera G, Mogan J, Humann J, et al. Transient Receptor Potential Melastatin 2 (TRPM2) ion channel is required for innate immunity against Listeria monocytogenes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:11578–83. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1010678108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]