Abstract

Nav1.5 dysfunctions are commonly linked to rhythms disturbances that include type 3 long QT syndrome (LQT3), Brugada syndrome (BrS), sick sinus syndrome (SSS) and conduction defects. Recently, this channel protein has been also linked to structural heart diseases such as dilated cardiomyopathy (DCM).

Keywords: heart, arrhythmias, sodium channels, gating pore, Nav1.5, dilated cardiomyopathy, structural model

So far, 17 mutations on Nav1.5 gene have been linked to a particular clinical phenotype grouping mixed cardiac arrhythmias and DCM. Most of these mutations are localized on the highly conserved voltage sensitive domain (VSD) of Nav1.5 channel. Mutations in the center of these VSDs create a conduction pathway, known as gating pore, through which cations can permeate. Here, we discuss the hypothesis that DCM linked mutations of the Nav1.5 channel create gating pores similar to the one observed as a result of the R219H mutation.7 Using the structural model of the Nav1.4 channel’s VSDs,17 we show that most of the Nav1.5 DCM linked mutations could induce gating pores. This implies that cations could permeate through the gating pores and may underlay the mixed arrhythmias and DCM phenotype.

Several Nav1.5 mutations are linked to dilated cardiomyopathy phenotypes, but their pathogenic mechanism remains to be elucidated

Dilated cardiomyopathy (DCM) is a common disorder characterized by a contraction defect of the left ventricle which is the result of its dilatation. The prevalence of DCM is estimated at 1 case out of 2500 individuals.1 DCM patients often suffer from various forms of arrhythmias as well as heart failure. Its high prevalence, incidence, and mortality make it an important health concern.

Nowadays, genetically inherited dilated cardiomyopathies are evaluated to account for 30% to 48% of all DCM cases.2 Mutations of the Nav1.5 channel are estimated to account for 1.7% of all familial dilated cardiomyopathy cases3 to 3% of all DCM cases2 making it a major cause of inherited DCM. Interestingly, mutations of Nav1.5 are usually linked to pure arrhythmic disorders such as Brugada syndrome4 or Long QT syndrome.5 Moreover, Nav1.5 linked DCM phenotypes are often severe as they usually feature various forms of arrhythmias such as bundle branch block, atrio-ventricular blocks, atrial fibrillation, and ventricular tachycardia (Table 1).

Table 1. Characteristics of Nav1.5 DCM linked mutations.

| Mutation | Localization | Biophysical defect | Clinical Phenotype | Reference | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Current density | Activation | Inactivation | Persistent Current | AFL | AFib | Tach | AVB and/or BBB | PVC | TdP | ||||

| Gain of function | S216L | S3-S4 / DI | ≈ | ≈ | + | 1,17% | x | 2 , 26 - 28 | |||||

| R814W | R3 – S4 /DII | ≈ | - | ≈ | ≈ | x | x | 6 , 29 | |||||

| D1595H | S3 / DIV | ≈ | - | ≈ | ND | x | 6 , 29 | ||||||

| P2005A | C-term | ND | ≈ | + | 0,54% | x | 2 , 28 | ||||||

| Intermediate | R219H | R1 – S4 / DI | ≈ | ≈ | ≈ | ND | x | x | x | x | 7 | ||

| R222Q | R2 – S4 / DI | ↓,≈ | - | - | ≈ | x | x | x | x | x | 2 , 30 - 33 | ||

| R225W | R3 – S4 /DI | ↓ | + | + | ND | x | x | 24 | |||||

| R814Q | R3 – S4 /DII | ND | - | - | ND | x | x | 16 , 34 | |||||

| D1275N | S3 / DIII | ≈, ↓ | ≈, + | ≈, -, + | ↑ | x | x | x | x | x | 29 , 35 - 40 | ||

| V1279I | S3 / DIII | ND | ND | ND | ≈ | x | x | x | 3 | ||||

| F1520L | DIII - DIV loop | ND | ND | ND | ND | x | x | 3 | |||||

| Loss of function | T220I | S4 / DI | ↓ | ≈ | - | ND | x | x | x | 29 , 35 , 41 | |||

| E446K | DI - DII loop | ↓ | ≈ | - | 0,22% | x | 3 , 42 | ||||||

| A1180V | DII-DIII loop | ≈ | ≈ | - | 0,50% | x | x | 43 | |||||

| R1193Q | DII-DIII loop | ≈ | ≈ | - | ~1% | x | 44 , 45 | ||||||

| ΔQKP 1507–1509 | DIII - DIV loop | ≈ | + | ≈ | ~2% | x | x | 46 , 47 | |||||

| I1835T | C-term | ↓ | ≈ | - | ≈ | 30 | |||||||

↑, Increase; ↓, Decrease; ≈, No impact; +, shifted toward more positive values; -, shifted toward more negative values; AFL, atrial flutter; AFib, atrial fibrillation; AVB, first, second, or third degree atrio-ventricular block; BBB, incomplete right or left bundle branch block; ND, not determined; PVC, premature ventricular contractions; Tach, tachycardia; TdP, Torsades de Pointes

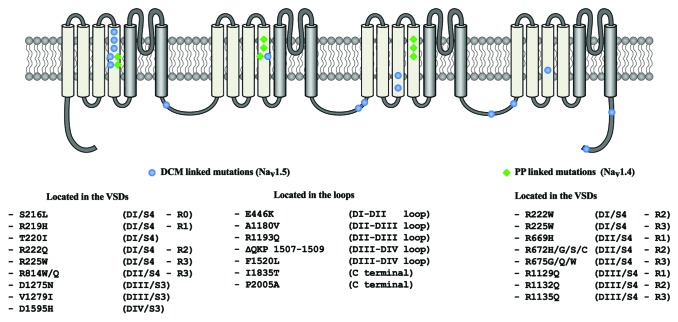

A total of 17 Nav1.5 mutations have been reported to be associated to the development of DCM (Table 1). These mutations are located either in the intracellular loops of the protein or in its voltage sensitive domains (VSDs) (Fig. 1). Recently, it has been reported that some of these mutations are linked to very similar familial phenotypes although they induce divergent biophysical defects6 (Table 1). Our investigation of the Nav1.5/R219H mutation revealed that it induces a cationic leak in the usually non-conductive VSD of the channel.7 Such leak currents have already been observed in similar proteins.8-10 They have been named gating pore currents or omega currents. In the cardiomyocyte, it is possible that gating pore currents have deleterious effects, which could lead to DCM. However, Nav1.5 mutations outside the VSD motifs are not though to generate such currents. This means that the generation of gating pore currents alone cannot explain the development of the pathology.

Figure 1. Two-dimensional structure of the voltage-gated sodium channels. The location of the Nav1.5 mutations associated with the mixed arrhythmias and DCM phenotype are shown in blue while location of the Nav1.4 mutations associated with periodic paralysis are shown in green.

Thus, despite recent advances in understanding of the link between Nav1.5 mutations and DCM, the pathological mechanism linking the mutations and the phenotype is still a subject of debate. Here we discuss our hypothesis on how Nav1.5 and DCM are linked based on the data available from studies on Nav1.5 and the similar Nav1.4 channel expressed in skeletal muscle.

Mutations in the channel’s intracellular loops all seem to generate persistent current

Table 1 shows that some mutations that occur on the intracellular loops of the channel could be classified either as gain-of-function mutations (ex: ΔQKP 1507–1509) or loss-of-function mutations (ex: A1180V). However, these DCM linked mutations induce persistent sodium current. This persistent current could be the single common characteristic which links all the mutations located in the intracellular loops. Indeed, it is known that persistent sodium current can lead to sodium overload and calcium overload.11 Both phenomena are known to decrease the sarcomere’s sensitivity to calcium.12 Incidentally, investigation of the known gene mutations linked to DCM shows that diminution in the sarcomere’s sensitivity to calcium are often linked to DCM.13

It is yet unclear why some mutations which induce persistent current are linked to DCM while others are not.5 The amplitude of the persistent sodium current may account for these differences.

Mutations in the channel’s VSDs could be linked to DCM via the induction of gating pores

The remaining Nav1.5 DCM linked mutations are all located in the VSDs (Fig. 1). Interestingly, very similar mutations in Nav1.4 channel have been shown to cause periodic paralysis phenotypes. For example, the Nav1.4 mutations, R675Q and R675W have all been shown to cause periodic paralysis14,15 via the induction of a gating pore. The mutation of the corresponding residues in Nav1.5 (R814Q and R814W) are linked to DCM phenotypes.2,6,16 The similar localization of the periodic paralysis linked mutations in Nav1.4 and DCM linked mutations in Nav1.5 (Fig. 1) prompted us to further examine the spatial localization of those mutations.

We recently reported that the Nav1.5/R219H mutation was linked to a familial DCM phenotype.7 This mutation did not change the classical biophysical properties of the channel which indicated that neither activation, inactivation nor recovery defects of the channel were linked to the pathology. However, the mutation did induce a proton-selective gating pore. This confirms that the induction of a gating pore might be a common characteristic linking all VSD located Nav1.5 mutations to DCM.

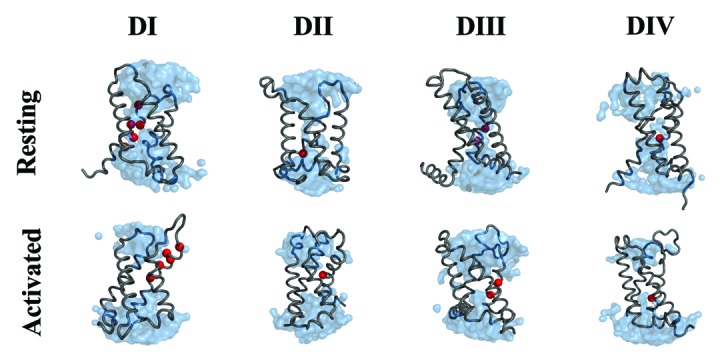

Using the structural model of the VSDs that we recently published,17 we examined more closely the environment of the DCM linked mutations. As shown by Figure 2, most VSD located mutations are located in close proximity to the VSD’s hydrophobic septum either in the channel’s resting or activated state. This septum maintains a separation between the extracellular and the intracellular media. The collapse of the hydrophobic septum in either of these states gives rise to the gating pore, which would be implicated in the pathogenesis of periodic paralysis and DCM.

Figure 2. Structural model of the Nav1.4 channel’s VSDs in their resting and activated conformations. The protein is displayed as a gray ribbon. The water crevices are shown in blue and the residues which correspond to the DCM linked mutations in Nav1.5 are displayed as red spheres.

To this day, most mutations known to induce gating pores occur on the highly conserved positively charged amino acids of the S4 segment. It is postulated that such mutations disrupt the interaction between the charged amino acid on the S4 segment and a motif formed by residues in the S1, S2, and S3 segments of the VSD called the gating charge transfer center (GCTC).17,18 Thus, it is possible that mutations affecting residues in the GCTC would generate a similar gating pore. Indeed, the Nav1.5/D1275N and Nav1.5/F1520L could disrupt the S4-GCTC interactions thus inducing gating pores. Similarly, mutations located in close proximity to key amino acids may affect the structure of the helice, which may in turn disrupt the GCTC-S4 interaction. Such a mechanism could occur for the Nav1.5/T220I and Nav1.5/V1279I mutations.

Both the gating pore mechanism and the persistent current mechanism may lead to ionic homeostasis imbalance

Gating pores have been shown to be permeable to monovalent ions such as proton, sodium, and potassium. Both proton and sodium permeation through these pores would lead to acidosis and calcium overload which would diminish the sensitivity of sarcomeres to calcium. Similar consequences could be expected as the result of the persistent sodium current. Thus, this mechanism could unify all the DCM linked Nav1.5 mutations.

Moreover, ionic homeostasis imbalance and alterations to the biophysical properties of Nav1.5 could explain the arrhythmias experienced by the patients. Acidosis in the heart could induce cardiac conduction disorders through the block of connexins 40/4319 and affect the function of ion channels.20 Most importantly, proton-selective gating pores could change sodium homeostasis through the activation of the sodium-proton antiport exchanger.21 This sodium overload could lead to an elevation of the myocytes’ resting potential which would facilitate the onset of cardiac arrhythmias. Furthermore, excess in intracellular sodium could lead the activation of the sodium-calcium exchanger in its reverse mode.11 This would increase the intracellular calcium concentration leading to cardiomyocyte apoptosis22 as well as major dysfunctions of heart rhythm or cardiac contractile function.12

Ionic homeostasis imbalance is the most likely mechanism to explain the association between Nav1.5 mutations and DCM

It should be mentioned that other hypothesis linking Nav1.5 to DCM has been put forward. Indeed, some may argue that DCM is the result of severe arrhythmic phenotypes.23 Such a hypothesis would be congruent with the severity of the various Nav1.5 linked DCM familial phenotypes. However, this hypothesis would not account for the observations of Bezzina et al. who have reported that a 1-y-old patient with Nav1.5 mutation was affected by DCM even though arrhythmia episodes before death were of short duration.24,25

Thus, we suggest that a mechanism involving ionic homeostasis imbalance via the induction of either gating pore currents or persistent sodium current is the only mechanism likely to provide the link between Nav1.5 mutations and DCM. Of course, further investigations are warranted to confirm this. We suggest that studies on Nav1.5 linked DCM mutations should focus on determining whether mutations located in the VSDs yield gating pores. Then, it would be interesting to determine if persistent sodium currents generated by Nav1.5 mutant channels could lead to sodium and/or calcium overload. Finally, it should be shown that sodium and calcium overload can, if experienced chronically, lead to DCM.

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by grants from the Heart and Stroke Foundation of Quebec (HSFQ), the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR, MOP-111072, and MOP-130373).

References

- 1.Codd MB, Sugrue DD, Gersh BJ, Melton LJ., 3rd Epidemiology of idiopathic dilated and hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. A population-based study in Olmsted County, Minnesota, 1975-1984. Circulation. 1989;80:564–72. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.80.3.564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hershberger RE, Parks SB, Kushner JD, Li D, Ludwigsen S, Jakobs P, Nauman D, Burgess D, Partain J, Litt M. Coding sequence mutations identified in MYH7, TNNT2, SCN5A, CSRP3, LBD3, and TCAP from 313 patients with familial or idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy. Clin Transl Sci. 2008;1:21–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-8062.2008.00017.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McNair WP, Sinagra G, Taylor MRG, Di Lenarda A, Ferguson DA, Salcedo EE, Slavov D, Zhu X, Caldwell JH, Mestroni L, Familial Cardiomyopathy Registry Research Group SCN5A mutations associate with arrhythmic dilated cardiomyopathy and commonly localize to the voltage-sensing mechanism. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;57:2160–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2010.09.084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Moreau A, Keller DI, Huang H, Fressart V, Schmied C, Timour Q, Chahine M. Mexiletine differentially restores the trafficking defects caused by two brugada syndrome mutations. Front Pharmacol. 2012;3:62. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2012.00062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Moreau A, Krahn AD, Gosselin-Badaroudine P, Klein GJ, Christé G, Vincent Y, Boutjdir M, Chahine M. Sodium overload due to a persistent current that attenuates the arrhythmogenic potential of a novel LQT3 mutation. Front Pharmacol. 2013;4:126. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2013.00126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nguyen TP, Wang DW, Rhodes TH, George AL., Jr. Divergent biophysical defects caused by mutant sodium channels in dilated cardiomyopathy with arrhythmia. Circ Res. 2008;102:364–71. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.107.164673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gosselin-Badaroudine P, Keller DI, Huang H, Pouliot V, Chatelier A, Osswald S, Brink M, Chahine M. A proton leak current through the cardiac sodium channel is linked to mixed arrhythmia and the dilated cardiomyopathy phenotype. PLoS One. 2012;7:e38331. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0038331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tombola F, Pathak MM, Isacoff EY. Voltage-sensing arginines in a potassium channel permeate and occlude cation-selective pores. Neuron. 2005;45:379–88. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2004.12.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sokolov S, Scheuer T, Catterall WA. Gating pore current in an inherited ion channelopathy. Nature. 2007;446:76–8. doi: 10.1038/nature05598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Struyk AF, Cannon SCA. A Na+ channel mutation linked to hypokalemic periodic paralysis exposes a proton-selective gating pore. J Gen Physiol. 2007;130:11–20. doi: 10.1085/jgp.200709755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tang Q, Ma J, Zhang P, Wan W, Kong L, Wu L. Persistent sodium current and Na+/H+ exchange contributes to the augmentation of the reverse Na+/Ca2+ exchange during hypoxia or acute ischemia in ventricular myocytes. Pflugers Arch. 2012;463:513–22. doi: 10.1007/s00424-011-1070-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Clanachan AS. Contribution of protons to post-ischemic Na(+) and Ca(2+) overload and left ventricular mechanical dysfunction. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2006;17(Suppl 1):S141–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8167.2006.00395.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kimura A. Molecular basis of hereditary cardiomyopathy: abnormalities in calcium sensitivity, stretch response, stress response and beyond. J Hum Genet. 2010;55:81–90. doi: 10.1038/jhg.2009.138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sokolov S, Scheuer T, Catterall WA. Depolarization-activated gating pore current conducted by mutant sodium channels in potassium-sensitive normokalemic periodic paralysis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:19980–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0810562105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Matthews E, Labrum R, Sweeney MG, Sud R, Haworth A, Chinnery PF, Meola G, Schorge S, Kullmann DM, Davis MB, et al. Voltage sensor charge loss accounts for most cases of hypokalemic periodic paralysis. Neurology. 2009;72:1544–7. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000342387.65477.46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Frigo G, Rampazzo A, Bauce B, Pilichou K, Beffagna G, Danieli GA, Nava A, Martini B. Homozygous SCN5A mutation in Brugada syndrome with monomorphic ventricular tachycardia and structural heart abnormalities. Europace. 2007;9:391–7. doi: 10.1093/europace/eum053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gosselin-Badaroudine P, Delemotte L, Moreau A, Klein ML, Chahine M. Gating pore currents and the resting state of Nav1.4 voltage sensor domains. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:19250–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1217990109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tao X, Lee A, Limapichat W, Dougherty DA, MacKinnon R. A gating charge transfer center in voltage sensors. Science. 2010;328:67–73. doi: 10.1126/science.1185954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stergiopoulos K, Alvarado JL, Mastroianni M, Ek-Vitorin JF, Taffet SM, Delmar M. Hetero-domain interactions as a mechanism for the regulation of connexin channels. Circ Res. 1999;84:1144–55. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.84.10.1144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Biel M, Schneider A, Wahl C. Cardiac HCN channels: structure, function, and modulation. Trends Cardiovasc Med. 2002;12:206–12. doi: 10.1016/S1050-1738(02)00162-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Clanachan AS. Contribution of protons to post-ischemic Na(+) and Ca(2+) overload and left ventricular mechanical dysfunction. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2006;17(Suppl 1):S141–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8167.2006.00395.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lu F, Tian Z, Zhang W, Zhao Y, Bai S, Ren H, Chen H, Yu X, Wang J, Wang L, et al. Calcium-sensing receptors induce apoptosis in rat cardiomyocytes via the endo(sarco)plasmic reticulum pathway during hypoxia/reoxygenation. Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol. 2010;106:396–405. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-7843.2009.00502.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Groenewegen WA, Wilde AAM. Letter regarding article by McNair et al, “SCN5A mutation associated with dilated cardiomyopathy, conduction disorder, and arrhythmia”. Circulation. 2005;112:e9–, author reply e9-10. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.104.531475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bezzina CR, Rook MB, Groenewegen WA, Herfst LJ, van der Wal AC, Lam J, Jongsma HJ, Wilde AA, Mannens MM. Compound heterozygosity for mutations (W156X and R225W) in SCN5A associated with severe cardiac conduction disturbances and degenerative changes in the conduction system. Circ Res. 2003;92:159–68. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000052672.97759.36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bezzina CR, Remme CA. Dilated cardiomyopathy due to sodium channel dysfunction: what is the connection? Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2008;1:80–2. doi: 10.1161/CIRCEP.108.791434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hedley PL, Jørgensen P, Schlamowitz S, Wangari R, Moolman-Smook J, Brink PA, Kanters JK, Corfield VA, Christiansen M. The genetic basis of long QT and short QT syndromes: a mutation update. Hum Mutat. 2009;30:1486–511. doi: 10.1002/humu.21106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Olesen MS, Yuan L, Liang B, Holst AG, Nielsen N, Nielsen JB, Hedley PL, Christiansen M, Olesen S-P, Haunsø S, et al. High prevalence of long QT syndrome-associated SCN5A variants in patients with early-onset lone atrial fibrillation. Circ Cardiovasc Genet. 2012;5:450–9. doi: 10.1161/CIRCGENETICS.111.962597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wang DW, Desai RR, Crotti L, Arnestad M, Insolia R, Pedrazzini M, Ferrandi C, Vege A, Rognum T, Schwartz PJ, et al. Cardiac sodium channel dysfunction in sudden infant death syndrome. Circulation. 2007;115:368–76. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.646513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Olson TM, Michels VV, Ballew JD, Reyna SP, Karst ML, Herron KJ, Horton SC, Rodeheffer RJ, Anderson JL. Sodium channel mutations and susceptibility to heart failure and atrial fibrillation. JAMA. 2005;293:447–54. doi: 10.1001/jama.293.4.447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cheng J, Morales A, Siegfried JD, Li D, Norton N, Song J, Gonzalez-Quintana J, Makielski JC, Hershberger RE. SCN5A rare variants in familial dilated cardiomyopathy decrease peak sodium current depending on the common polymorphism H558R and common splice variant Q1077del. Clin Transl Sci. 2010;3:287–94. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-8062.2010.00249.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Laurent G, Saal S, Amarouch MY, Béziau DM, Marsman RFJ, Faivre L, Barc J, Dina C, Bertaux G, Barthez O, et al. Multifocal ectopic Purkinje-related premature contractions: a new SCN5A-related cardiac channelopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;60:144–56. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2012.02.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mann SA, Castro ML, Ohanian M, Guo G, Zodgekar P, Sheu A, Stockhammer K, Thompson T, Playford D, Subbiah R, et al. R222Q SCN5A mutation is associated with reversible ventricular ectopy and dilated cardiomyopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;60:1566–73. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2012.05.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nair K, Pekhletski R, Harris L, Care M, Morel C, Farid T, Backx PH, Szabo E, Nanthakumar K. Escape capture bigeminy: phenotypic marker of cardiac sodium channel voltage sensor mutation R222Q. Heart Rhythm. 2012;9:1681–8, e1. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2012.06.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chen LQ, Santarelli V, Horn R, Kallen RG. A unique role for the S4 segment of domain 4 in the inactivation of sodium channels. J Gen Physiol. 1996;108:549–56. doi: 10.1085/jgp.108.6.549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gui J, Wang T, Trump D, Zimmer T, Lei M. Mutation-specific effects of polymorphism H558R in SCN5A-related sick sinus syndrome. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2010;21:564–73. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8167.2010.01762.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gui J, Wang T, Jones RPO, Trump D, Zimmer T, Lei M. Multiple loss-of-function mechanisms contribute to SCN5A-related familial sick sinus syndrome. PLoS One. 2010;5:e10985. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0010985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Groenewegen WA, Firouzi M, Bezzina CR, Vliex S, van Langen IM, Sandkuijl L, Smits JPP, Hulsbeek M, Rook MB, Jongsma HJ, et al. A cardiac sodium channel mutation cosegregates with a rare connexin40 genotype in familial atrial standstill. Circ Res. 2003;92:14–22. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000050585.07097.D7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Laitinen-Forsblom PJ, Mäkynen P, Mäkynen H, Yli-Mäyry S, Virtanen V, Kontula K, Aalto-Setälä K. SCN5A mutation associated with cardiac conduction defect and atrial arrhythmias. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2006;17:480–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8167.2006.00411.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.McNair WP, Ku L, Taylor MRG, Fain PR, Dao D, Wolfel E, Mestroni L, Familial Cardiomyopathy Registry Research Group SCN5A mutation associated with dilated cardiomyopathy, conduction disorder, and arrhythmia. Circulation. 2004;110:2163–7. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000144458.58660.BB. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Watanabe H, Yang T, Stroud DM, Lowe JS, Harris L, Atack TC, Wang DW, Hipkens SB, Leake B, Hall L, et al. Striking In vivo phenotype of a disease-associated human SCN5A mutation producing minimal changes in vitro. Circulation. 2011;124:1001–11. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.987248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Benson DW, Wang DW, Dyment M, Knilans TK, Fish FA, Strieper MJ, Rhodes TH, George AL., Jr. Congenital sick sinus syndrome caused by recessive mutations in the cardiac sodium channel gene (SCN5A) J Clin Invest. 2003;112:1019–28. doi: 10.1172/JCI18062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Crotti L, Hu D, Barajas-Martinez H, De Ferrari GM, Oliva A, Insolia R, Pollevick GD, Dagradi F, Guerchicoff A, Greco F, et al. Torsades de pointes following acute myocardial infarction: evidence for a deadly link with a common genetic variant. Heart Rhythm. 2012;9:1104–12. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2012.02.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ge J, Sun A, Paajanen V, Wang S, Su C, Yang Z, Li Y, Wang S, Jia J, Wang K, et al. Molecular and clinical characterization of a novel SCN5A mutation associated with atrioventricular block and dilated cardiomyopathy. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2008;1:83–92. doi: 10.1161/CIRCEP.107.750752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wang Q, Chen S, Chen Q, Wan X, Shen J, Hoeltge GA, Timur AA, Keating MT, Kirsch GE. The common SCN5A mutation R1193Q causes LQTS-type electrophysiological alterations of the cardiac sodium channel. J Med Genet. 2004;41:e66. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2003.013300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kwon HW, Lee SY, Kwon BS, Kim GB, Bae EJ, Kim WH, Noh CI, Cho SI, Park SS. Long QT syndrome and dilated cardiomyopathy with SCN5A p.R1193Q polymorphism: cardioverter-defibrillator implantation at 27 months. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 2012;35:e243–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8159.2012.03409.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Keller DI, Acharfi S, Delacrétaz E, Benammar N, Rotter M, Pfammatter JP, Fressart V, Guicheney P, Chahine M. A novel mutation in SCN5A, delQKP 1507-1509, causing long QT syndrome: role of Q1507 residue in sodium channel inactivation. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2003;35:1513–21. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2003.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Shi R, Zhang Y, Yang C, Huang C, Zhou X, Qiang H, Grace AA, Huang CL-H, Ma A. The cardiac sodium channel mutation delQKP 1507-1509 is associated with the expanding phenotypic spectrum of LQT3, conduction disorder, dilated cardiomyopathy, and high incidence of youth sudden death. Europace. 2008;10:1329–35. doi: 10.1093/europace/eun202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]