Abstract

Background

Intact cartilage in the lateral compartment is an important requirement for medial unicompartmental knee arthroplasty (UKA). Progression of cartilage degeneration in the lateral compartment is a common failure mode of medial UKA. Little is known about factors that influence the mechanical properties of lateral compartment cartilage.

Questions/purposes

The purposes of this study were to answer the following questions: (1) Does the synovial fluid white blood cell count predict the biomechanical properties of macroscopically intact cartilage of the distal lateral femur? (2) Is there a correlation between MRI grading of synovitis and the biomechanical properties of macroscopically intact cartilage? (3) Is there a correlation between the histopathologic assessment of the synovium and the biomechanical properties of macroscopically intact cartilage?

Methods

The study included 84 patients (100 knees) undergoing primary TKA for varus osteoarthritis between May 2010 and January 2012. All patients underwent preoperative MRI to assess the degree of synovitis. During surgery, the cartilage of the distal lateral femur was assessed macroscopically using the Outerbridge grading scale. In knees with an Outerbridge grade of 0 or 1, osteochondral plugs were harvested from the distal lateral femur for biomechanical and histologic assessment. The synovial fluid was collected to determine the white blood cell count. Synovial tissue was taken for histologic evaluation of the degree of synovitis.

Results

The mean aggregate modulus and the mean dynamic modulus were significantly greater in knees with 150 or less white blood cells/mL synovial fluid compared with knees with greater than 150 white blood cells/mL synovial fluid. There was no correlation among MRI synovitis grades, histopathologic synovitis grades, and biomechanical cartilage properties.

Conclusions

The study suggests that lateral compartment cartilage in patients with elevated synovial fluid white blood cell counts has a reduced ability to withstand compressive loads.

Level of Evidence

Level III, diagnostic study. See the Instructions for Authors for a complete description of levels of evidence.

Introduction

Osteoarthritis (OA) is one of the most common causes of knee pain and disability [11, 13, 51]. Overall, knee OA is more common in the medial than in the lateral compartment [31]. Unicompartmental knee arthroplasty (UKA) is an effective treatment option for end-stage medial compartment arthritis [10] and currently is experiencing increasing popularity [41, 46]. Intact cartilage in the lateral compartment is an important requirement for medial UKA [17], but its assessment remains challenging [23].

Brocklehurst et al. [7] showed that there is no significant difference in the biochemical composition between visually intact cartilage from osteoarthritic and nonarthritic knees. Obeid et al. [35], however, showed that clinically, radiologically, and morphologically intact cartilage in the uninvolved compartment is mechanically inferior to cartilage from nonarthritic knees. Inflammation is recognized to play a substantial role in the pathogenesis of osteoarthritis [5, 6, 16, 34]. In more recent years, several inflammatory mediators released by cartilage, bone, and synovium have been described [16, 19, 25]. Determination of the number of white blood cells (WBC) in the synovial fluid is a crucial diagnostic test in the discrimination between inflammatory or noninflammatory forms of joint effusion [14, 43, 47, 49]. The biomechanical properties of articular cartilage are governed by the composition and structure of its extracellular matrix [9]. Cartilage remodeling processes are highly active under inflammatory conditions [37]. The increased turnover rate and atypical composition of newly synthesized extracellular matrix appear to compromise the quality of the extracellular cartilage matrix [27, 29]. These compositional changes affect the mechanical stability of articular cartilage which ultimately leads to fibrillation and fissure formation [40, 44].

To our knowledge, whether the presence of intraarticular inflammation has an effect on the quality of lateral compartment cartilage in patients considered for UKA has not been reported.

The objective of our study was to evaluate the effect of increased inflammation in the knee on the biomechanical properties of macroscopically intact lateral compartment cartilage in patients undergoing TKA for varus OA.

We asked the following research questions: (1) Does the synovial fluid WBC count predict the biomechanical properties of macroscopically intact cartilage of the distal lateral femur? (2) Is there a correlation between MRI grading of synovitis and the biomechanical properties of macroscopically intact cartilage? (3) Is there a correlation between the histopathologic assessment of the synovium and the biomechanical properties of macroscopically intact cartilage?

Patients and Methods

Eighty-four patients (100 knees) undergoing primary TKA for varus OA were prospectively enrolled in our study between May 2010 and January 2012. The exclusion criteria were secondary arthritis and neutral or valgus alignment observed on hip-to-ankle AP standing radiographs.

During surgery, the distal lateral femoral condyle of all knees was macroscopically analyzed using the Outerbridge grading scale [36]. Knees with an Outerbridge Grade 2 or more were excluded from the current study because they were not considered potential candidates for UKA, leaving 72 knees (37 left knees and 35 right knees) in 63 patients (29 men and 34 women) included in the study. The mean age of the patients was 66 years (range, 49–87 years), and their mean BMI was 25.1 kg/m2 (range, 17–37 kg/m2). The study was approved by the institutional review board and all participants signed an informed consent.

Radiographic and MRI Protocols

Each patient received a preoperative standardized hip-to-ankle AP standing radiograph and underwent MRI of the knee. All images were stored in a generic DICOM format.

Hip-to-ankle AP standing radiographs were obtained following standardized institutional protocols with the crosshair of the radiographic beam centered between the knees.

All subjects underwent MRI using 1.5-T or 3-T clinical scanners (GE Healthcare, Waukesha, WI, USA) using an eight-channel phased-array transmit receive coil (Invivo, Orlando, FL, USA), a quadrature receive-only lower extremity coil (Invivo), or a three-channel phased-array receive-only shoulder coil (USA Instruments Inc, Aurora, OH, USA). Two-dimensional fast spin echo images were obtained in three planes.

The radiographic grading and all measurements were performed on a picture archiving and communication system with commercial planning software (Sectra IDS7TM; Sectra, Linköping, Sweden).

On hip-to-ankle AP standing radiographs, the hip-knee-ankle angle was defined as the angle between the femoral mechanical axis (center of hip to center of knee) and the tibial mechanical axis (center of knee to center of ankle) [30, 32, 33]. On MRI, overall synovitis in the knee was assessed using the Whole-Organ Magnetic Resonance Imaging Score (WORMS) which is based on the estimated percentage of synovial cavity distension, taking into account joint effusion and synovial thickening or debris: no distension (Grade 0), 0% to 33% distension (Grade 1), 34% to 66% distension (Grade 3), and 67% to 100% distension (Grade 4) [39].

Sample Collection

During surgery, 8-mm osteochondral plugs were removed from the center of the distal lateral femoral condyle. Osteochondral samples were placed in protease inhibitor (Sigma Aldrich, St Louis, MO, USA) and stored at −20° C. Synovial fluid was aspirated before opening the capsule, and sent for a WBC count. The WBC count served as an indicator of inflammation in the knee. Samples of synovial tissue were taken from the suprapatella pouch along the anterior distal femur and sent to the pathology laboratory for further processing in 10% buffered formalin.

Synovial fluid was available from 47 knees in 47 patients. These knees were split into two groups to assess the effect of the synovial fluid WBC count on biomechanical cartilage properties. The two groups were formed in a way so that the synovial fluid WBC count in Group 1 resembled the number of normal nonarthritic knees (63 WBC/mL) [42]. Therefore, starting with the lowest available synovial fluid WBC counts, knees were included in Group 1 in an ascending order. At 150 WBC/mL, the mean count in Group 1 best matched the synovial fluid WBC count previously described for normal, nonarthritic knees [42]. The mean synovial fluid WBC count of 63/mL was defined as normal before initiation of the study. The separation in the two groups at 150 WBC/mL does not serve as a cutoff and is based only on the mean synovial fluid WBC count for normal knees. The mean synovial fluid WBC count was 60/mL (95% CI, 44–75) in Group 1 (n = 34 knees, 34 patients) and 328/mL (95% CI, 212–434) in Group 2 (n = 13 knees, 13 patients), respectively.

Demographic data for patients in Groups 1 and 2 showed no differences regarding age, sex, mechanical alignment, macroscopic Outerbridge grades, microscopic Mankin grades, MRI synovitis grades, or histopathologic synovitis grades (Table 1).

Table 1.

Demographic data for the patients*

| Parameter | Group 1 | Group 2 | Differences between groups |

|---|---|---|---|

| (N = 34 patients) | (N = 13 patients) | ||

| Age (years) | 68 | 65 | p = 0.368 |

| Females (number) | 20 (59%) | 5 (38.5%) | p = 0.867 |

| Males (number) | 14 (41%) | 8 (61.5%) | |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 25.2 | 25.0 | p = 0.600 |

| (95% CI, 23.6–26.8) | (95% CI, 20.9–29.2) | ||

| Hip-knee-ankle angle (degrees) | 8.8 | 7.2 | p = 0.490 |

| (95% CI, 7.2–10.3) | (95% CI, 5.3–9.2) | ||

| Outerbridge grades | 0.2 | 0.2 | p = 0.675 |

| (95% CI, 0.0–0.3) | (95% CI, 0.0–0.5) | ||

| Mankin grades | 1.4 | 1.2 | p = 0.792 |

| (95% CI, 0.7–2.2) | (95% CI, 0.4–1.9) | ||

| MRI synovitis grades | 2.6 | 2.4 | p = 0.347 |

| (95% CI, 2.3–2.8) | (95% CI, 2.1–2.7) | ||

| Histopathologic synovitis grades | 2.3 | 2.5 | p = 0.488 |

| (95% CI, 2.0–2.6) | (95% CI, 1.9–3.2) |

* There were no significant differences between the two groups. Synovial fluid was available for only 47 patients. For the remaining patients, no synovial fluid could be aspirated from their knees during surgery.

Biomechanics

Each osteochondral sample was oriented so that the center of the sample was perpendicular to a porous indenter (diameter, 1.25 mm) that was attached to the upper actuator of an EnduraTEC testing machine (EnduraTEC ElectroForce® 3200; Bose® Corporation, Eden Prairie, MN, USA). The load cell was zeroed with the weight of the indenter. The indenter was manually brought in close proximity to the cartilage surface and contact was determined when the load cell read approximately 1g. Then a compressive load of 20 g equivalent to 0.16 N/mm2 was applied at a rate of 5 g/second and held for 1 hour. A saline drip was applied to keep tissue moist throughout testing. After testing was completed, the indenter fixture was replaced with a needle fixture to measure cartilage thickness. The needle was started at the surface and moved through cartilage at 0.05 mm/second until it pierced bone. When the needle reached the cartilage-bone interface a drastic change in stiffness was observed. After biomechanical testing, samples were placed in 10% buffered formalin.

For data extraction of the biomechanical tests, displacement-time data were numerically fit to the biphasic indentation creep solution to determine the aggregate modulus (Ha) at each test site [8, 26]. The dynamic modulus was calculated by determining the stress and strain during the initial ramping portion of the test and identifying the linear slope of the resulting stress or strain curve. Data extraction resulted in bad data for six of the 72 knees, therefore, statistical analysis on biomechanical data was performed for 66 knees.

Histology

After biomechanical testing, osteochondral samples were decalcified in standard HCl solution with a chelating agent (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) and embedded in paraffin. Two 5-μm-thick sections were cut from each block and stained with hematoxylin and eosin and with safranin O-fast green. All sections were scored in consensus by an experienced, board-certified pathologist (GP) and a trained research fellow (WW) using the Mankin cartilage grading system [28]. The Mankin classification considers cartilage structure, cellularity, safranin O staining, and tidemark integrity and ranges from 0 (normal) to 14 (severe OA).

The synovial tissue was entirely sectioned at macroscopic examination, adequately sampled, and underwent standard processing, paraffin embedding, sectioned at 5 μm, and was stained with hematoxylin and eosin. Inflammation of the synovium was assessed using a validated histopathologic grading system [20, 21] which includes an analysis of the following morphologic alterations: (1) hyperplasia/enlargement of synovial lining cell layer; (2) activation of resident cells/synovial stroma; and (3) inflammatory infiltration. Each histopathologic quality is graded from absent (0), slight (1), and moderate (2), to strong (3), with summaries ranging from 0 (no inflammation) to 9 (strong synovitis).

The intraobserver reliability for the histopathologic cartilage assessment was performed for 20 random samples at two occasions separated by 4 weeks. Single measures are given for intraobserver calculations. Intraobserver and interobserver reliabilities for measurements of hip-knee-ankle angle have been reported [52]. An excellent intraobserver intraclass correlation coefficient (0.955) was observed for the microscopic cartilage assessment.

The histologic evaluation confirmed the intraoperative macroscopic assessment of cartilage in the lateral compartment. Osteochondral samples from 70 of 72 (97%) knees graded as Outerbridge Grade 0 or 1 had a histologically normal structure or only some surface irregularities. Among all knees visually assessed as intact (Outerbridge Grade 0/1), only one sample had clefts to the transitional zone and one sample had clefts to the radial zone, respectively. The mean Mankin grade was 1.1 (95% CI, 0.7–1.5).

For descriptive analysis, the hip-knee-ankle angle was expressed in degrees with 95% CIs and cartilage thickness was expressed in millimeters with 95% CIs. The distributions of all variables were examined in an exploratory data analysis and tested for normality using Kolmogorov-Smirnov tests. Because not all variables met the criteria for a normal distribution, the Mann-Whitney U test was performed to compare the distribution of variables. Spearman rank correlation (rs) was used for nonparametric correlations. A two-way mixed model with 95% CIs was used for calculation of the intraclass correlation coefficient. Probability values less than 0.05 were considered significant. Correlation was characterized as poor (0.00–0.20), fair (0.21–0.40), moderate (0.41–0.60), good (0.61–0.80), or excellent (0.81–1.00) [1]. Statistical tests were done using SPSS 16.0 software for Windows (SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL, USA).

Results

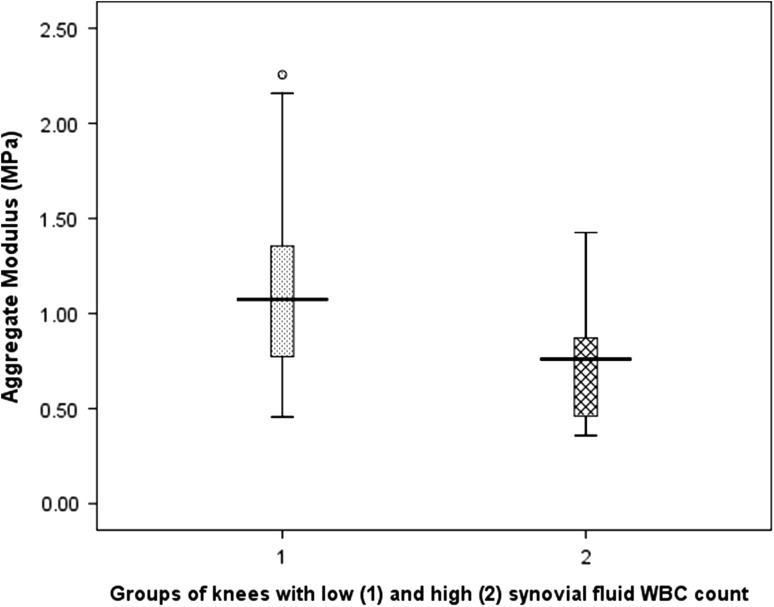

The lateral compartment cartilage is mechanically inferior in knees with an elevated synovial fluid WBC count. The mean aggregate modulus (Fig. 1) and mean dynamic modulus (Fig. 2) were significantly greater in Group 1 (≤ 150 WBCs/mL) compared with Group 2 (> 150 WBCs/mL) (Table 2).

Fig. 1.

A box plot illustrates the significant difference (p = 0.006) in the aggregate modulus between Group 1 and Group 2. Group 1 has a mean WBC count of 60/mL (95% CI, 44–75) and Group 2 has a mean WBC count of 328/mL (95% CI, 212–434), respectively.

Fig. 2.

A box plot illustrates the significant difference (p = 0.010) in the dynamic modulus between Group 1 and Group 2. Group 1 has a mean WBC count of 60/mL (95% CI, 44–75) and Group 2 has a mean WBC count of 328/mL (95% CI, 212–434), respectively.

Table 2.

Aggregate modulus, dynamic modulus, and cartilage thickness for intact cartilage*

| Parameter | Entire cohort | Group 1 | Group 2 | Differences between groups |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (N = 66 knees) | (N = 34 knees) | (N = 13 knees) | ||

| Aggregate modulus (MPa) | 1.02 | 1.10 | 0.74 | p = 0.006 |

| (95% CI, 0.91–1.13) | (95% CI, 0.94–1.26) | (95% CI, 0.55–0.93) | ||

| Dynamic modulus (MPa) | 5.85 | 6.12 | 4.26 | p = 0.010 |

| (95% CI, 5.25–6.46) | (95% CI, 5.22–7.02) | (95% CI, 3.17–5.36) | ||

| Cartilage thickness (mm) | 2.43 | 2.51 | 2.22 | p = 0.071 |

| (95% CI, 2.31–2.56) | (95% CI, 2.32–2.70) | (95% CI, 2.00–2.47) |

* Cartilage in Group 1 had significantly better biomechanical cartilage properties compared with Group 2. Data for the biomechanical tests of the entire cohort (66 knees) are presented. Knees in Groups 1 and 2 are subgroups of the entire cohort.

MRI grades of synovitis did not correlate with the aggregate modulus (rs = 0.097, p = 0.437) nor did it correlate with the dynamic modulus (rs = −0.096, p = 0.442).

Similarly, no correlations were observed between the histopathologic synovitis grades and the aggregate modulus (rs = −0.115, p = 0.362) and the dynamic modulus (rs = −0.061, p = 0.628), respectively. There was no correlation (p = 0.192) between the MRI grades of overall synovitis and the histopathologic synovitis grades.

Discussion

Successful outcomes with UKA require strict observation of indications [12]. One of the most important factors influencing long-term survival is the condition of cartilage in the opposite femorotibial compartment [48]. Little is known about factors that influence the mechanical properties of lateral compartment cartilage. To the best of our knowledge, there is no published study describing the clinical value of assessing intraarticular inflammation in the preoperative workup for UKA. We therefore evaluated the clinical value of the synovial fluid WBC count, the MRI synovitis grading system, and the histopathologic assessment of the synovium in patients with medial compartment arthritis. Our study showed that the lateral compartment cartilage is mechanically inferior in knees with an elevated synovial fluid WBC count. However, no correlations were observed between MRI synovitis grades and histopathologic synovitis grades, and any of the biomechanical cartilage properties.

Our study has some limitations. First, the groups were selected to create one group with synovial fluid WBC similar to that of nonarthritic joints [42]. It can be argued that the separation based on normal synovial fluid WBC is arbitrary and based only on previously reported values of normal synovial fluid WBC counts. However, we do not aim to suggest a cutoff level of synovial fluid WBC predicting normal biomechanical cartilage properties. Rather, our study shows that relatively small differences in synovial fluid WBC already have a substantial effect on cartilage properties. Second, this is a clinical study and not an experimental study. Therefore, a causal relationship between increased synovial fluid WBC counts and reduced cartilage stiffness cannot be concluded with certainty. However, we tried to control for as many confounding variable as possible: age, sex, mechanical alignment, macroscopic Outerbridge grades, microscopic Mankin grades, MRI synovitis grades, and histopathologic synovitis grades. Third, we did not analyze cytokines and chemokines profiles of synovial fluid, which might be helpful to discriminate between knees with early degenerative changes and more advanced OA in the lateral compartment [18]. Fourth, in 25 of the 72 knees, no synovial fluid WBC count was available because we were unable to aspirate fluid. This could have affected the sample size in Group 2. Fifth, because the same osteochondral plugs were analyzed biomechanically and histologically, the initial biomechanical test could have affected the histologic analysis. To minimize this affect, biomechanical tests always were performed in the middle, whereas the histologic sections were cut on the periphery of the 8-mm plug. Sixth, cartilage samples were not tested biochemically, which does not allow correlating inflammation to water, proteoglycan, and collagen content. Finally, there was no postoperative followup to investigate whether the lateral compartment actually deteriorates more rapidly in knees with high preoperative synovial fluid WBC counts. Although important, this question is beyond the scope of the study. Future studies are needed to confirm that intraarticular inflammation presents a risk factor for more rapid cartilage degeneration after prosthesis implantation in a UKA.

The study suggests that the lateral compartment cartilage in patients with elevated synovial fluid WBC counts shows reduced ability to withstand compressive loads. Knees with medial unicompartmental arthritis and increased synovial fluid WBC counts have mechanically inferior cartilage in the lateral compartment compared with knees with a WBC count less than 150/mL. The data provide additional insight into which patients are at risk for progression of lateral compartment cartilage degeneration after medial UKA. The American College of Rheumatology defines that up to 2000 WBC/mL synovial fluid are normal for osteoarthritic joints [2]. These values can be explained by a moderate inflammatory response to osteoarthritis [3]. In the current study, the two groups were formed in a way so that the synovial fluid WBC count in Group 1 resembled the number for normal nonarthritic knees. The mean synovial fluid WBC count in our study is relatively low in comparison to this, which also is reflected in low histopathologic synovitis grades. Our study is unique because it suggests that even small changes in synovial fluid WBC levels have an influence on the biomechanical cartilage properties and might explain significant differences of the biomechanical properties of lateral compartment cartilage.Based on the available literature, we believe our study is the first describing the influence of joint inflammation on biomechanical properties of lateral compartment cartilage in medial unicompartmental arthritis.

The aggregate modulus in our study was within the range previously reported for normal human lateral femoral condyles [4, 22, 50]. However, the calculated dynamic modulus was lower than described by Kurkijärvi et al. [22]. They reported on the dynamic modulus of 13 nonarthritic samples of the distal lateral femur with a mean dynamic modulus of 10.0 MPa and a SD of 3.7 MPa. Whether these higher values are caused by the small sample size (n = 13) in their study or because they present samples from nonarthritic knees remains unclear [22]. The MRI synovitis grades did not correlate with cartilage biomechanics. The MRI grading scale we used classifies synovitis in four grades based on overall synovial distension. We believe that a more refined grading scale is required to establish correlations of biomechanical cartilage properties with grades of synovial inflammation on MRI.

The histopathologic synovitis grading scale [20, 21] we used does not predict biomechanical cartilage properties. Although this grading system is the only established score [45], it is intended primarily to differentiate between OA and rheumatoid arthritis. More advanced immunohistochemical markers like Ki-67 or CD68 [38] might be necessary to define a more sensitive grading system for the synovium in patients with OA of the knee. Such a grading system might lead to better correlations of the histopathologic degree of synovitis and biomechanical properties of articular cartilage in the lateral compartment in patients with medial compartment OA. The lack of correlation between the MRI grades of overall synovitis and histopathologic synovitis might be explained by the different grading scales and because MRI evaluated the synovium of the entire knee but the histologic analysis only looked at samples from the suprapatella pouch. This explanation is supported by Lindblad and Hedfors [24] who reported that inflammatory changes of the synovium are present only adjacent to cartilage degeneration. Signs of synovial inflammation therefore seem to be more prominent in areas close to degenerated cartilage [15].

Our relatively small series suggested that the lateral compartment cartilage in varus knees with elevated synovial fluid WBC counts has inferior biomechanical properties compared with cartilage in knees with normal WBC counts. If confirmed by larger studies, it suggests that in knees with lateral compartment cartilage suitable for medial UKA (Outerbridge Grade 0 or 1), increased synovial fluid WBC levels might present a risk factor for more rapid cartilage deterioration than those with a low WBC. Longer followup of these patients is needed to see if the predictions of earlier deterioration of the lateral cartilage in the high WBC group occur.

Acknowledgments

We thank Suzanne A. Maher PhD, Department of Biomechanics, Hospital for Special Surgery for help in the study design and analysis of biomechanical data; Yana Bonfman, Department of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine, Hospital for Special Surgery for histologic preparation of the osteochondral samples and the synovium; Nadja Farshad-Amacker MD, Division of Magnetic Resonance Imaging, Hospital for Special Surgery for assistance in MRI assessment of the synovium; and Jad Bou Monsef MD, Adult Reconstruction & Joint Replacement Division, Hospital for Special Surgery for assistance with radiographic measurements.

Footnotes

The institution of the authors (FB) has received funding from Smith & Nephew, Memphis, TN, USA.

All ICMJE Conflict of Interest Forms for authors and Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research editors and board members are on file with the publication and can be viewed on request.

Each author certifies that his institution has approved the human protocol for this investigation, that all investigations were conducted in conformity with ethical principles of research, and that informed consent for participation in the study was obtained.

References

- 1.Altman DG. Practical Statistics for Medical Research. London, UK: Chapman and Hall; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Altman R, Asch E, Bloch D, Bole G, Borenstein D, Brandt K, Christy W, Cooke TD, Greenwald R, Hochberg M, et al. Development of criteria for the classification and reporting of osteoarthritis: classification of osteoarthritis of the knee. Diagnostic and Therapeutic Criteria Committee of the American Rheumatism Association. Arthritis Rheum. 1986;29:1039–1049. doi: 10.1002/art.1780290816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Altman RD, Gray R. Inflammation in osteoarthritis. Clin Rheum Dis. 1985;11:353–365. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Athanasiou KA, Rosenwasser MP, Buckwalter JA, Malinin TI, Mow VC. Interspecies comparisons of in situ intrinsic mechanical properties of distal femoral cartilage. J Orthop Res. 1991;9:330–340. doi: 10.1002/jor.1100090304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bellucci F, Meini S, Cucchi P, Catalani C, Nizzardo A, Riva A, Guidelli GM, Ferrata P, Fioravanti A, Maggi CA. Synovial fluid levels of bradykinin correlate with biochemical markers for cartilage degradation and inflammation in knee osteoarthritis. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2013;21:1774–1780. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2013.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Berenbaum F. Osteoarthritis as an inflammatory disease (osteoarthritis is not osteoarthrosis!) Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2013;21:16–21. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2012.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brocklehurst R, Bayliss MT, Maroudas A, Coysh HL, Freeman MA, Revell PA, Ali SY. The composition of normal and osteoarthritic articular cartilage from human knee joints: with special reference to unicompartmental replacement and osteotomy of the knee. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1984;66:95–106. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brown TD, Singerman RJ. Experimental determination of the linear biphasic constitutive coefficients of human fetal proximal femoral chondroepiphysis. J Biomech. 1986;19:597–605. doi: 10.1016/0021-9290(86)90165-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Buckwalter JA, Mankin HJ. Articular cartilage: degeneration and osteoarthritis, repair, regeneration, and transplantation. Instr Course Lect. 1998;47:487–504. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cartier P, Khefacha A, Sanouiller JL, Frederick K. Unicondylar knee arthroplasty in middle-aged patients: a minimum 5-year follow-up. Orthopedics. 2007;30:62–65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Davis MA, Ettinger WH, Neuhaus JM, Mallon KP. Knee osteoarthritis and physical functioning: evidence from the NHANES I Epidemiologic Followup Study. J Rheumatol. 1991;18:591–598. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Deschamps G, Chol C. Fixed-bearing unicompartmental knee arthroplasty:patients’ selection and operative technique. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res. 2011;97:648–661. doi: 10.1016/j.otsr.2011.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ettinger WH, Jr, Fried LP, Harris T, Shemanski L, Schulz R, Robbins J. Self-reported causes of physical disability in older people: the Cardiovascular Health Study. CHS Collaborative Research Group. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1994;42:1035–1044. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1994.tb06206.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Freemont AJ. Role of cytological analysis of synovial fluid in diagnosis and research. Ann Rheum Dis. 1991;50:120–123. doi: 10.1136/ard.50.2.120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Goldenberg DL, Egan MS, Cohen AS. Inflammatory synovitis in degenerative joint disease. J Rheumatol. 1982;9:204–209. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Goldring MB, Otero M. Inflammation in osteoarthritis. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2011;23:471–478. doi: 10.1097/BOR.0b013e328349c2b1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Goodfellow JW, O’Connor J, Dodd CA, Murray DW. Unicompartmental Arthroplasty with the Oxford Knee. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Heard BJ, Fritzler MJ, Wiley JP, McAllister J, Martin L, El-Gabalawy H, Hart DA, Frank CB, Krawetz R. Intraarticular and systemic inflammatory profiles may identify patients with osteoarthritis. J Rheumatol. 2013;40:1379–1387. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.121204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kapoor M, Martel-Pelletier J, Lajeunesse D, Pelletier JP, Fahmi H. Role of proinflammatory cytokines in the pathophysiology of osteoarthritis. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2011;7:33–42. doi: 10.1038/nrrheum.2010.196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Krenn V, Morawietz L, Burmester GR, Kinne RW, Mueller-Ladner U, Muller B, Haupl T. Synovitis score: discrimination between chronic low-grade and high-grade synovitis. Histopathology. 2006;49:358–364. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.2006.02508.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Krenn V, Morawietz L, Haupl T, Neidel J, Petersen I, Konig A. Grading of chronic synovitis: a histopathological grading system for molecular and diagnostic pathology. Pathol Res Pract. 2002;198:317–325. doi: 10.1078/0344-0338-5710261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kurkijarvi JE, Nissi MJ, Kiviranta I, Jurvelin JS, Nieminen MT. Delayed gadolinium-enhanced MRI of cartilage (dGEMRIC) and T2 characteristics of human knee articular cartilage: topographical variation and relationships to mechanical properties. Magn Reson Med. 2004;52:41–46. doi: 10.1002/mrm.20104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Laskin RS. Unicompartmental tibiofemoral resurfacing arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1978;60:182–185. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lindblad S, Hedfors E. Arthroscopic and immunohistologic characterization of knee joint synovitis in osteoarthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 1987;30:1081–1088. doi: 10.1002/art.1780301001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Loeser RF, Goldring SR, Scanzello CR, Goldring MB. Osteoarthritis: a disease of the joint as an organ. Arthritis Rheum. 2012;64:1697–1707. doi: 10.1002/art.34453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mak AF, Lai WM, Mow VC. Biphasic indentation of articular cartilage: I. Theoretical analysis. J Biomech. 1987;20:703–714. doi: 10.1016/0021-9290(87)90036-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Maldonado M, Nam J. The role of changes in extracellular matrix of cartilage in the presence of inflammation on the pathology of osteoarthritis. Biomed Res Int. 2013;2013:284873. doi: 10.1155/2013/284873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mankin HJ, Dorfman H, Lippiello L, Zarins A. Biochemical and metabolic abnormalities in articular cartilage from osteo-arthritic human hips: II. Correlation of morphology with biochemical and metabolic data. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1971;53:523–537. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Martel-Pelletier J, Boileau C, Pelletier JP, Roughley PJ. Cartilage in normal and osteoarthritis conditions. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2008;22:351–384. doi: 10.1016/j.berh.2008.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Marx RG, Grimm P, Lillemoe KA, Robertson CM, Ayeni OR, Lyman S, Bogner EA, Pavlov H. Reliability of lower extremity alignment measurement using radiographs and PACS. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2011;19:1693–1698. doi: 10.1007/s00167-011-1467-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.McAlindon TE, Snow S, Cooper C, Dieppe PA. Radiographic patterns of osteoarthritis of the knee joint in the community: the importance of the patellofemoral joint. Ann Rheum Dis. 1992;51:844–849. doi: 10.1136/ard.51.7.844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Merle C, Waldstein W, Pegg E, Streit MR, Gotterbarm T, Aldinger PR, Murray DW, Gill HS. Femoral offset is underestimated on anteroposterior radiographs of the pelvis but accurately assessed on anteroposterior radiographs of the hip. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2012;94:477–482. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.94B4.28067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Moreland JR, Bassett LW, Hanker GJ. Radiographic analysis of the axial alignment of the lower extremity. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1987;69:745–749. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nam J, Perera P, Liu J, Rath B, Deschner J, Gassner R, Butterfield TA, Agarwal S. Sequential alterations in catabolic and anabolic gene expression parallel pathological changes during progression of monoiodoacetate-induced arthritis. PLoS One. 2011;6:e24320. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0024320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Obeid EM, Adams MA, Newman JH. Mechanical properties of articular cartilage in knees with unicompartmental osteoarthritis. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1994;76:315–319. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Outerbridge RE. The etiology of chondromalacia patellae. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1961;43:752–757. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.43B4.752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pearle AD, Warren RF, Rodeo SA. Basic science of articular cartilage and osteoarthritis. Clin Sports Med. 2005;24:1–12. doi: 10.1016/j.csm.2004.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pessler F, Dai L, Diaz-Torne C, Gomez-Vaquero C, Paessler ME, Zheng DH, Einhorn E, Range U, Scanzello C, Schumacher HR. The synovitis of “non-inflammatory” orthopaedic arthropathies: a quantitative histological and immunohistochemical analysis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2008;67:1184–1187. doi: 10.1136/ard.2008.087775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Peterfy CG, Guermazi A, Zaim S, Tirman PF, Miaux Y, White D, Kothari M, Lu Y, Fye K, Zhao S, Genant HK. Whole-Organ Magnetic Resonance Imaging Score (WORMS) of the knee in osteoarthritis. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2004;12:177–190. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2003.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Poole AR, Kobayashi M, Yasuda T, Laverty S, Mwale F, Kojima T, Sakai T, Wahl C, El-Maadawy S, Webb G, Tchetina E, Wu W. Type II collagen degradation and its regulation in articular cartilage in osteoarthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2002;61(suppl 2):ii78–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 41.Riddle DL, Jiranek WA, McGlynn FJ. Yearly incidence of unicompartmental knee arthroplasty in the United States. J Arthroplasty. 2008;23:408–412. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2007.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ropes MW, Bauer W. Synovial Fluid Changes in Joint Disease. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 1953. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Shmerling RH, Delbanco TL, Tosteson AN, Trentham DE. Synovial fluid tests: what should be ordered? JAMA. 1990;264:1009–1014. doi: 10.1001/jama.1990.03450080095039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Silver FH, Bradica G, Tria A. Elastic energy storage in human articular cartilage: estimation of the elastic modulus for type II collagen and changes associated with osteoarthritis. Matrix Biol. 2002;21:129–137. doi: 10.1016/S0945-053X(01)00195-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Slansky E, Li J, Haupl T, Morawietz L, Krenn V, Pessler F. Quantitative determination of the diagnostic accuracy of the synovitis score and its components. Histopathology. 2010;57:436–443. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.2010.03641.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Soohoo NF, Sharifi H, Kominski G, Lieberman JR. Cost-effectiveness analysis of unicompartmental knee arthroplasty as an alternative to total knee arthroplasty for unicompartmental osteoarthritis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2006;88:1975–1982. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.E.00597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Swan A, Amer H, Dieppe P. The value of synovial fluid assays in the diagnosis of joint disease: a literature survey. Ann Rheum Dis. 2002;61:493–498. doi: 10.1136/ard.61.6.493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Swienckowski JJ, Pennington DW. Unicompartmental knee arthroplasty in patients sixty years of age or younger. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2004;86(suppl 1):131–142. doi: 10.2106/00004623-200409001-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tercic D, Bozic B. The basis of the synovial fluid analysis. Clin Chem Lab Med. 2001;39:1221–1226. doi: 10.1515/CCLM.2001.196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Treppo S, Koepp H, Quan EC, Cole AA, Kuettner KE, Grodzinsky AJ. Comparison of biomechanical and biochemical properties of cartilage from human knee and ankle pairs. J Orthop Res. 2000;18:739–748. doi: 10.1002/jor.1100180510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Verbrugge LM, Lepkowski JM, Konkol LL. Levels of disability among U.S. adults with arthritis. J Gerontol. 1991;46:S71–S83. doi: 10.1093/geronj/46.2.S71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Waldstein W, Monsef JB, Buckup J, Boettner F. The value of valgus stress radiographs in the workup for medial unicompartmental arthritis. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2013;471:3998–4003. doi: 10.1007/s11999-013-3212-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]