Abstract

Background:

Cynanchum paniculatum, belongs to the family Asclepiadaceae and is used to treat various diseases, such as invigorate blood, alleviate edema and to relieve pain and toxicity for a long time.

Materials and Methods:

4,5-Dimethoxypyrocatechol was isolated from the 80% methanol extract of C. paniculatum and its neuroprotective effect was evaluated by MTT assay.

Results:

4,5-Dimethoxypyrocatechol had neuroprotective effect on the glutamate-induced cellular oxidative death in HT22 cells.

Conclusion:

Furthermore, we found that reactive oxygen species (ROS) accumulation and calcium concentration by oxidative stress were reduced by 4,5-dimethoxypyrocatechol in HT22 cells.

Keywords: Cynanchum paniculatum; 4,5-dimethoxypyrocatechol; HT22 cells; neuroprotective effect

INTRODUCTION

Oxidative stress was implicated in various neurodegenerative diseases including Alzheimer's disease (AD).[1] Oxidative stress causes neuronal cell death and necrosis resulting in neuronal diseases.[2] Glutamate is the major excitatory neurotransmitter in brain and can contribute to neuronal cell death.[3,4] High levels of extracellular glutamate generate excitotoxicity, and this causes calcium (Ca2+) to enter cells, leading to neuronal damage via increased reactive oxygen species (ROS) levels.[5,6] Glutamate induced oxidative stress results in the depletion of glutathione and accumulation of ROS levels by inhibiting the uptake of cystine through the glutamate/cystine antiporter system x(c)−.[7,8]

The immortalized mouse hippocampal HT22 cells, a sub-line of HT4 cells, have been used as an in vitro hippocampal cholinergic neuronal model for studying the mechanism of oxidative glutamate toxicity.[9]

The whole plant or root of Cynanchum paniculatum Kitagawa (Asclepiadaceae family) that is found in Korea, China, and Japan has been used to treat many diseases, such as rheumatoid arthritis, lumbago, abdominal pain, vomiting, and acute gastro-enteritis, and it used as an anodyne. There are several reports in the literature indicating that C. paniculatum has the anti-inflammatory and antinociceptive effects.[10] C. paniculatum is known to contain compounds such as paeonol, C21 steroids, glycosides, and alkaloids. Paeonol is a major active compound in C. paniculatum.[11,12] We isolated 10 compounds, paeonol, 4-acetylphenol, 2,5-dihydroxy-4-methoxyacetophenone, 2,3-dihydroxy-4-methoxyacetophenone, acetoveratrone, 2,5-dimethoxyhydroquinone, vanillic acid, resacetophenone, m-acetylphenol, and 3,5-dimethoxy-hydroquinone from C. paniculatum and investigated their neuroprotective effects.[13]

The aim of this study was to isolate additional compounds from C. paniculatum and to evaluate their neuroprotective effect against glutamate-induced oxidative stress in mouse HT22 cells.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plant materials

The roots of C. paniculatum were purchased from Kyungdong traditional herbal market in Seoul and were identified by Dr. Young Bae Seo, a professor of the College of Oriental Medicine, Daejeon University (Daejeon, Korea). A voucher specimen (No. CJ021M) was deposited in the Department of Biomaterials Engineering in Kangwon National University.

Extraction and isolation

Roots of C. paniculatum (5.2 kg) were extracted using 80% methanol by ultrasonication-assisted extraction at room temperature. The extract was partitioned with n-hexane, CHCl3, EtOAc, and n-BuOH. The CHCl3 fraction (36.86 g) was subjected to silica gel column chromatography (CC) to obtain eight (A–H) fractions. Compound A was isolated from C by Sephadex-LH 20 CC and preparative HPLC on a C18 YMC hydrosphere (250 mm × 20 mm I.D. S-5 μm).

HT22 cell culture

Mouse hippocampal HT22 cells were obtained from Seoul National University, Korea. HT22 cells were cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% (v/v) fetal bovine serum (FBS), 100 U/ml penicillin, and 100 μg/ml streptomycin, and maintained at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2.

Measurement of cell viability

Cell viability was evaluated by MTT assay. HT22 cells (6.7 × 104 cells/300 μL) were seeded into 48-well plates. After 24 h of incubation, the cells were treated with various concentrations of samples and 50 μM trolox, a well-known antioxidant, and were further incubated for 1 h. Then, 2 mM glutamate was added to the DMEM medium for 24 h. MTT solution (1 mg/mL) was applied to the cells and incubated for 3 h. The formazan formed was dissolved in 300 μL of dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO). Optical density was measured at 570 nm using an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) reader. Neuroprotective activity of samples was investigated by relative protection ratio (%).

Determination of ROS level

The level of intracellular ROS was detected using 2′7′-dichlorofluorescein diacetate (H2-DCF-DA) in HT22 cells. Cells (6.74 × 104/well) were treated with 2 mM glutamate in the presence or absence of sample. After 8 h of glutamate treatment, the cells were stained with 10 μM DCF-DA in Hanks’ balanced salt solution for 30 min in a dark room. The cells were then extracted with 1% Triton X-100 in PBS for 10 min at 37°C. Fluorescence was recorded with an excitation wavelength of 490 nm and an emission wavelength of 525 nm.

Measurement of Ca2+ concentration

Cytosolic Ca2+ concentration in HT22 cells was measured by fluorescence assay using the Fura-2AM. HT22 cells (6.74 × 104/well) were plated into 48-well plates. After treatment of 10, 50, and 100 μM of sample and 2 μM Fura-AM, glutamate was added to each well. After 2 h, the cells were washed with PBS and then suspend in 1% Triton X-100. Fluorescence was measured at an excitation wavelength of 400 nm and an emission wavelength of 535 nm.

DPPH radical scavenging assay

The DPPH radical scavenging assay was performed for the determination of free radical-scavenging activity by the decreases in absorbance of DPPH solution. Various concentrations of sample (150 μL) were added to 150 μL of 0.4 mM DPPH-methanol solution into a 96-well microplate. After 30 min at darkroom, reduction of the DPPH free radical was measured by recording the absorbance at 517 nm. L-Ascorbic acid was used as a positive control. The assay was repeated three times. Percentage inhibition was calculated using the formula, (1 − sample absorbance/only DPPH absorbance) ×100.

RESULTS

Isolation of a compound from C. paniculatum

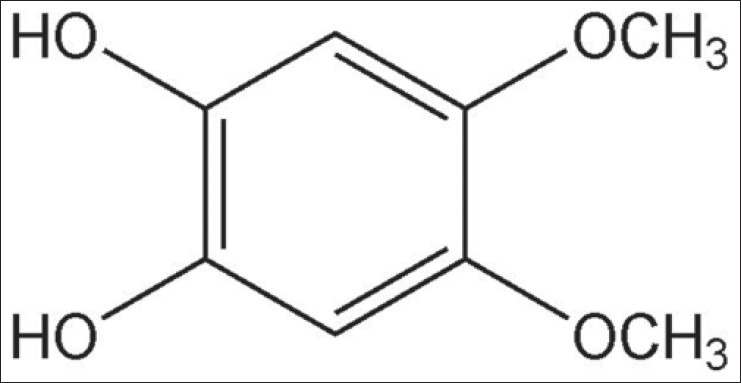

We isolated compound A from CHCl3 fraction of C. paniculatum and elucidated it using a 1H and 13C nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR). The structure of isolated compound A was identified as 4,5-dimethoxypyrocatechol by comparison with a previously reported spectroscopic data and its structure [Figure 1].

Figure 1.

The chemical structures of 4,5-dimethoxypyrocatechol

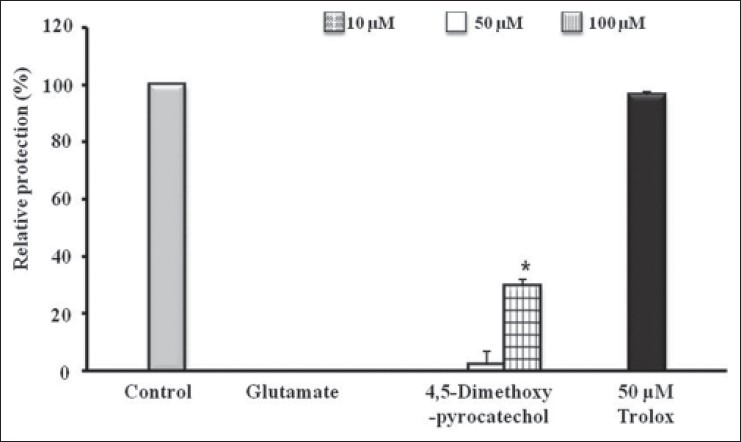

Cell viability

To investigate whether 4,5-dimethoxypyrocatechol protects against glutamate-induced neuronal cell death in HT22 cell, MTT assay was performed. The relative protection (%) of 4,5-dimethoxypyrocatechol was 2.19% and 29.59% at 50 μM and 100 μM, respectively [Figure 2].

Figure 2.

The neuroprotective effects of 4,5-dimethoxypyrocatechol on glutamate-induced cytotoxicity in HT22 cells. HT22 cells were treated with 10, 50, and 100 μM of 4,5-dimethoxypyrocatechol, and then incubated for 24 h with glutamate (2 mM). Positive control, trolox (50 μM) exhibited relative protective activity (96.39 ± 1.25%). Each bar represents the mean ± SD of three independent experiments. *P< 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 vs. SCRT (ANOVA)

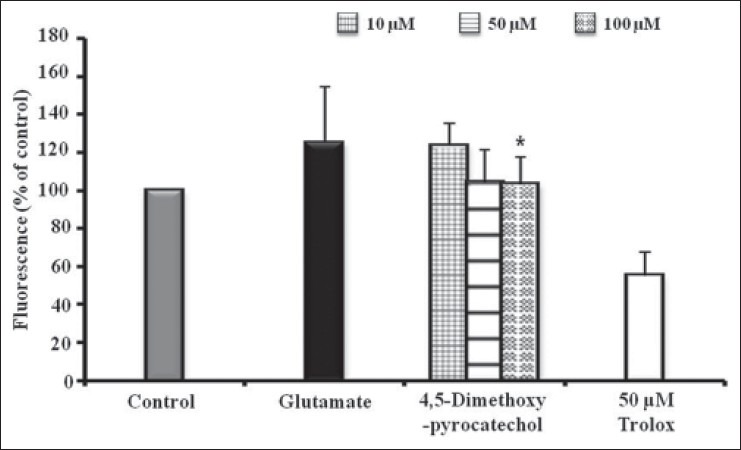

ROS measurement

To evaluate the effect of 4,5-dimethoxypyrocatechol on the intracellular ROS induced by oxidative stress, ROS levels were determined by 2′7′-dichlorofluorescein diacetate (H2-DCF-DA) in HT22 cells.[14] The level of ROS of glutamate-stimulated cells was recorded as 125.14%. The level of ROS on 4,5-dimethoxypyrocatechol-treated cells was recorded as 123.74%, 104.23%, and 103.36% at 10, 50, and 100 μM, respectively. 4,5-Dimethoxypyrocatechol suppressed glutamate-induced intracellular ROS production in cells [Figure 3].

Figure 3.

Inhibition of reactive oxygen species generation. HT22 cells were treated with 10, 50, and 100 μM of 4,5-dimethoxypyrocatechol and then exposed to 2 mM glutamate for 8 h increased ROS production. Trolox (10 μM) was used as a positive control. Each bar represents the mean ± SD of three independent experiments. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 vs. glutamate-injured cells (ANOVA)

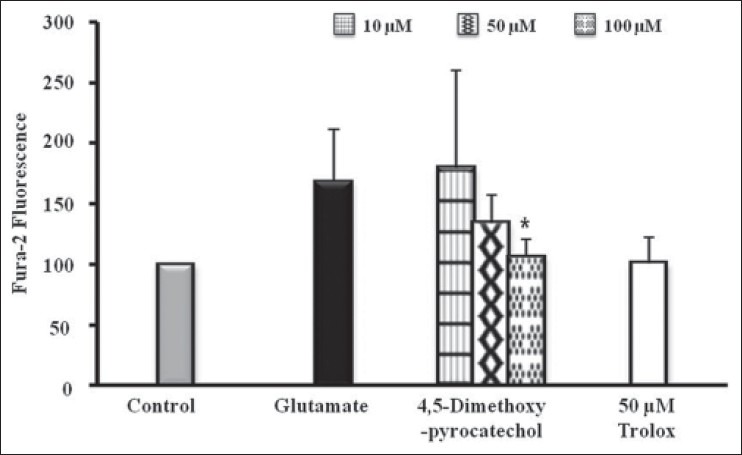

Determination of intracellular Ca2+ concentration

For the measurement of intracellular Ca2+ concentration, 2 μM Fura-AM was used. Exposure of HT22 cells to glutamate-induced oxidative stress resulted in 167.99% increase in Ca2+ level. However, increase in the Ca2+ level was reduced by 4,5-dimethoxypyrocatechol (100 μM), and the value of Ca2+ value was recorded as 106.28% [Figure 4].

Figure 4.

Effect of homosyringaldehyde on intracellular Ca2+ accumulation in glutamate-treated HT22 cells. 4,5-Dimethoxypyrocatechol was treated with 2 μM Fura-2 AM 1 h before exposure to glutamate. The alteration of Ca2+ concentration measured 2 h after glutamate treated. The data present means ± SD. *P< 0.05, **P < 0.01 and ***P < 0.001 vs. glutamate-injured cells (ANOVA)

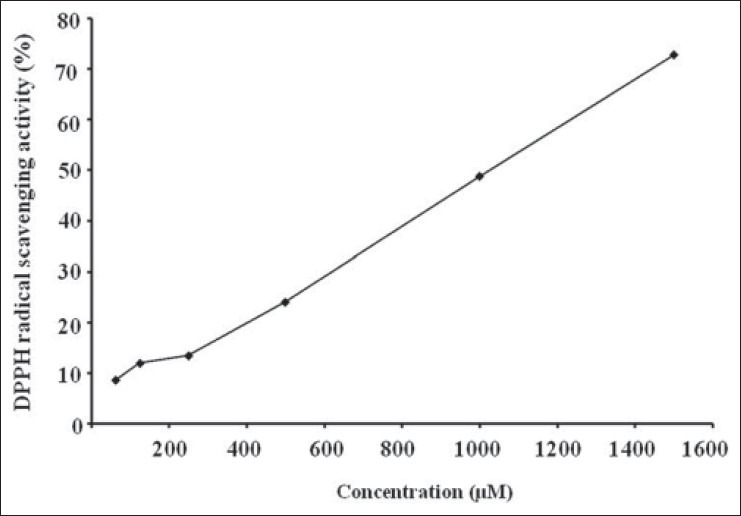

Antioxidant activity

To evaluate the antioxidant ability of 4,5-dimethoxy pyrocatechol, DPPH radical scavenging activity was assayed. As shown in Figure 5, 4,5-dimethoxypyrocatechol showed prominent DPPH inhibitory activity with IC50 values of 931.75 μM.

Figure 5.

Anti-oxidant effects of 4,5-dimethoxypyrocatechol; DPPH radical scavenging activity.*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 vs. control (ANOVA)

DISCUSSION

Glutamate-induced oxidative cell death is mediated by c-jun N-terminal kinase (JNK), one of the mitogen-activated protein kinase and various apoptosis-inducing factors.[15] Glutamate toxicity can block the glutamate/cystine antiporter system x(c)−, followed by the depletion of glutathione. Ca2+ accumulation and generation of ROS is a common pathway of many forms of cell death.[16,17] HT22 cell is a good in vitro model system for screening for agents that may prevent glutamate-induced oxidative cell death. HT22 cell also expresses essential cholinergic markers, such as choline acetyltransferase, muscarinic acetylcholine receptors, and high-affinity choline transporter, but it does not have functional iontropic receptors, such as the N-methyl-D-asparatate (NMDA) receptor.[18,19]

Our previous study showed that C. paniculatum was found to exhibit neuroprotective effect and isolated neuroprotective phenolic compounds.[13] In addition, the present study isolated compound from C. paniculatum and identified it as 4,5-dimethoxypyrocatechol. Also, 4,5-dimethoxypyrocatechol showed neuroprotective effect against glutamate-induced cell death in HT22 cell. 4,5-Dimethoxypyrocatechol dose-dependently reduced cell death and exhibited significant neuroprotective effect at 100 μM. To better understand the underlying mechanism of neuroprotective effect of 4,5-dimethoxypyrocatechol from oxidative glutamate toxicity, we examined inhibitory effect of ROS production and intracellular Ca2+ elevation. The result of these experiments showed that 4,5-dimethoxypyrocatechol reduced glutamate-induced ROS reduction and attenuated acceleration of Ca2+ fluxes in HT22 cells.

In addition, to evaluate the antioxidative effect of 4,5-dimethoxypyrocatechol, DPPH radical scavenging activity was investigated. DPPH radical is a stable free radical, which has been widely used to evaluate the radical-scavenging ability of antioxidants. 4,5-Dimethoxypyrocatechol showed scavenging activity for DPPH radical.

4,5-Dimethoxypyrocatechol has a catechol structure and is a phenolic compound. Many studies have demonstrated that phenolic compounds have more effective antioxidant activity and neuroprotective effect against the cytotoxicity of glutamate and hydrogen peroxide. This neuroprotective effect of phenolic compounds might be due to its antioxidant activity.[20,21]

In conclusion, 4,5-dimethoxypyrocatechol from C. paniculatum showed involvement of neuroprotection to prevent glutamate-induced oxidative cell death through its activity to suppress ROS, inhibition of Ca2+ concentration, and antioxidantive effect. Therefore, 4,5-dimethoxypyrocatechol may be a valuable source of potential neuroprotective agents.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

This research was supported by Basic Science Research Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) funded by the Ministry of Education, Science, and Technology (2010-0005149).

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Coyle JT, Puttfarchen P. Oxidative stress, glutamate, and neurodegenerative disorders. Science. 1993;262:689–95. doi: 10.1126/science.7901908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Satoh T, Enokido Y, Kubo T, Yamada M, Hatanaka H. Oxygen toxicity induces apoptosis in neuronal cells. Cell Mol Neurobiol. 1998;18:649–66. doi: 10.1023/A:1020633919115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ikonomidou C, Turski L. Excitotoxicity and neurodegenerative diseases. Curr Opin Neurol. 1995;8:487–97. doi: 10.1097/00019052-199512000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fukui M, Song JH, Choi J, Choi HJ, Zhu BT. Mechanism of glutamate-induced neurotoxicity in HT22 mouse hippocampal cells. Eur J Pharmacol. 2009;617:1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2009.06.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mattson MP. Apoptosis in neurodegenerative disorders. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2000;1:120–9. doi: 10.1038/35040009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tan S, Wood M, Maher P. Oxidative stress induces a form of programmed cell death with characteristics of both apoptosis and necrosis in neuronal cells. J Neurochem. 1998;71:95–105. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1998.71010095.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Albrecht P, Lewerenz J, Dittmer S, Noack R, Maher P, Methner A. Mechanisms of oxidative glutamate toxicity: The glutamate/cystine antiporter system xc- as a neuroprotective drug target. CNS Neurol Disord Drug Targets. 2010;9:373–82. doi: 10.2174/187152710791292567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Davis JB, Maher P. Protein kinase C activation inhibits glutamate-induced cytotoxicity in a neuronal cell line. Brain Res. 1994;652:169–73. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(94)90334-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tan S, Schubert D, Maher P. Oxitosis: A novel form of programmed cell death. Curr Top Med Chem. 2001;1:497–506. doi: 10.2174/1568026013394741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Choi JH, Jung BH, Kang OH, Choi HJ, Park PS, Cho SH, et al. The anti-inflammatory and anti-nociceptive effects of ethyl acetate fraction of Cynanchi paniculati radix. Biol Pharm Bull. 2006;29:971–5. doi: 10.1248/bpb.29.971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mitsuhashi H, Sakurai K, Nomura T, Kawahara N. Constituents of asclepiadaceae plants. XVII. Components of Cynanchum wifordi Hemsley. Chem Pharm Bull (Tokyo) 1996;14:712–7. doi: 10.1248/cpb.14.712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Li SL, Tan H, Shen YM, Kawazoe K, Hao XJ. A pair of new C-21 steroidal glycoside epimers from the roots of Cynanchum paniculatum. J Nat Prod. 2004;67:82–4. doi: 10.1021/np034013c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Weon JB, Kim CY, Yang HJ, Ma CJ. Neuroprotective compounds isolated from Cynanchum paniculatum. Arch Pharm Res. 2012;35:617–21. doi: 10.1007/s12272-012-0404-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang H, Joseph JA. Quantifying cellular oxidative stress by dichlorofluorescein assay using microplate reader. Free Radical Biol Med. 1999;27:612–6. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(99)00107-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Saitoh M, Nishitoh H, Fujii M, Takeda K, Tobiume K, Sawada Y, et al. Mammalian thioredoxin is a direct inhibitor of apoptosis signal-regulating kinase (ASK) 1. EMBO J. 1998;17:2596–606. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.9.2596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Weikert S, Feryer D, Weih M, Isaev N, Busch C, Schultze J, et al. Rapid Ca2+ dependent NO-production from central nervous system cells in culture measured by NO-nitrite/ozone chemoluminescence. Brain Res. 1997;748:1–11. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(96)01241-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Weon JB, Yang HJ, Lee B, Yun BR, Ahn JH, Lee HY, et al. Neuroprotective activity of the methanolic extract of Lonicera japonica in glutamate-injured primary rat cortical cells. Pharmacogn Mag. 2011;7:284–8. doi: 10.4103/0973-1296.90404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liu J, Li L, Suo WZ. HT22 hippocampal neuronal cell line possesses functional cholinergic properties. Life Sci. 2009;84:267–71. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2008.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tan S, Sagara Y, Liu Y, Maher P, Schubert D. The regulation of reactive oxygen species production during programmed cell death. J Cell Biol. 1998;141:1423–32. doi: 10.1083/jcb.141.6.1423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Justino GC, Correia CF, Mira L, Borges Dos Santos RM, Martinho Simões JA, Silva AM, et al. Antioxidant activity of a catechol derived from abietic acid. J Agric Food Chem. 2006;54:342–8. doi: 10.1021/jf052062k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Li G, Min BS, Zheng C, Lee J, Oh SR, Ahn KS, et al. Neuroprotective and free radical scavenging activities of phenolic compounds from Hovenia dulcis. Arch Pharm Res. 2005;28:804–9. doi: 10.1007/BF02977346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]