Abstract

Fetal alcohol syndrome (FAS) is a prenatal disease characterized by fetal morphological and neurological abnormalities originating from exposure to alcohol. Although FAS is a well-described pathology, the molecular mechanisms underlying its progression are virtually unknown. Moreover, alcohol abuse can affect vitamin metabolism and absorption, although how alcohol impairs such biochemical pathways remains to be elucidated. We employed a variety of systems chemo-biology tools to understand the interplay between ethanol metabolism and vitamins during mouse neurodevelopment. For this purpose, we designed interactomes and employed transcriptomic data analysis approaches to study the neural tissue of Mus musculus exposed to ethanol prenatally and postnatally, simulating conditions that could lead to FAS development at different life stages. Our results showed that FAS can promote early changes in neurotransmitter release and glutamate equilibrium, as well as an abnormal calcium influx that can lead to neuroinflammation and impaired neurodifferentiation, both extensively connected with vitamin action and metabolism. Genes related to retinoic acid, niacin, vitamin D, and folate metabolism were underexpressed during neurodevelopment and appear to contribute to neuroinflammation progression and impaired synapsis. Our results also indicate that genes coding for tubulin, tubulin-associated proteins, synapse plasticity proteins, and proteins related to neurodifferentiation are extensively affected by ethanol exposure. Finally, we developed a molecular model of how ethanol can affect vitamin metabolism and impair neurodevelopment.

Introduction

The maternal consumption of alcohol, especially during the initial 3–6 weeks of brain development, can lead to abnormal fetal nervous system changes during pregnancy, resulting in fetal alcohol syndrome (FAS) and fetal alcohol syndrome disorders (FASD) (de la Monte and Kril, 2014; Jaurena et al., 2011; O'Leary, 2004; Wentzel and Eriksson, 2009; Zhou et al., 2011). Although alcohol abstinence is recommended during pregnancy, more than 20% of pregnant women worldwide continue to abuse alcohol (van der Wulp et al., 2013). In these cases, a wide range of abnormal neurological outcomes can arise from FAS, including excessive neuron apoptosis (Genetta et al., 2007; Maffi et al., 2008), the risk of neuronal disorders (RNDs), and brain malformations during early embryonic development that affect neural crest and neural tube development (Wentzel and Eriksson, 2009; Zhou et al., 2011). In addition, alcohol abuse induces neuronal changes that affect both prenatal and postnatal life, including learning and cognitive impairments in young adults (O'Leary, 2004). Although FAS is an extensively studied pathology, the molecular pathways underlying its effects remain to be elucidated.

One of the many pathways affected by alcohol consumption is vitamin metabolism. Vitamin supplementation is necessary for fetal development, and specific vitamins play pivotal roles in the control of embryonic neurodevelopment (Table 1). For example, vitamins A and B9 are related to neural tube closure and development (Table 1). In addition, reduced intake of vitamins has also been related to brain malformations or changes in neurodifferentiation patterns (Table 1). Moreover, alcohol consumption is already known to decrease the serum levels and absorption of the active forms of vitamin A (retinoic acid; RA), vitamin B1 (thiamine; TM), vitamin B9 (folic acid; FA), and vitamin E (α-tocopherol; α-TC) (Bjorneboe et al., 1987; Goez et al., 2011; Hewitt et al., 2011; Qin and Crews, 2013; Singleton and Martin, 2001). However, knowledge concerning the mechanisms through which alcohol affects the vitamin levels and metabolism at the molecular level is still scarce. Furthermore, because the effects of FAS are mainly on the nervous system and because all vitamins appear to play pivotal roles in brain formation (Table 1), it is crucial to understand the interplay between vitamins' biochemical pathways and alcohol during neurogenesis.

Table 1.

Major Vitamins Present in the Interactome for M. musculus and Their Role During Neurodevelopment or Proper Neural Tissue Function Throughout Embryonic Brain Development or Neuronal in vitro Lineages

| Vitamin | Role in the neural tissue |

|---|---|

| Vitamin A (RA) | RA is related to the control of the hindbrain and forebrain development and neural tube differentiation (Jiang et al., 2012; Rhinn and Dolle, 2012). It also regulates neuronal patterning along the anterior-posterior axis (Shearer et al., 2012). |

| Vitamin C (AC) | Vitamin C is essential for hippocampal development and for hippocampal postnatal function in guinea pigs (Tveden-Nyborg et al., 2012). Vitamin C also exerts anti-oxidant effects, preventing neurotoxic insults in the brain, such as ROS production (Tveden-Nyborg and Lykkesfeldt, 2009). Another study showed that ascorbic acid is highly present throughout midbrain development during human pregnancy (Adlard et al., 1974). Moreover, ascorbic acid was able to induce differentiation of CNS precursor cells into neurons and astrocytes (Lee et al., 2003) |

| Vitamin D [25-(OH) D3]/[1,25-(OH)2D3] | Vitamin D induces neurite formation (Eyles et al., 2011). Additionally, 25-hydroxyvitamin D3 upregulates nerve growth factor (NGF), which is essential for survival and growth of hippocampal and forebrain neurons (Eyles et al., 2011). Vitamin D deficiency is also correlated with decreased apoptosis and diminished cortex thickness (Eyles et al., 2013; Harms et al., 2011). The vitamin D receptor (VDR) is also present in the hippocampus (Eyles et al., 2013). |

| Vitamin K (PQN/MQN) | Promotes survival of cultured rat embryo CNS neurons (Nakajima et al., 1993). Pregnant women treated with vitamin K antagonist (warfarin) presented fetuses with abnormal dilatation of cerebral ventricle, microcephaly and mental retardation (Tsaioun, 1999). Showed neuroprotective role against oxidative stress (Josey et al., 2013). |

| Vitamin E (α-TC) | Described as playing an essential role in early brain formation, where tocopherol transporter protein (TTP) was present in the hindbrain and forebrain in zebrafish (Miller et al., 2012). |

| Vitamin B12 (CBL) | CBL is related to the process of myelination (Black, 2008), and deficiency in vitamin B12 is related to neural tube defects (Kirsch et al., 2013; van de Rest et al., 2012; Veena et al., 2010). Although not confirmed, a study shows that vitamin B12 deficiency might play a role in the developing brain and may change the normal cognitive status later in life (Bhate et al., 2008). |

| Vitamin B9 (FA) | FA supplementation reduces the risk of neural tube defects in human embryos (Kirsch et al., 2013; Leung et al., 2013; Ross, 2010). It is also essential for fetal spine and cranial formation (Morse, 2012). Deficiency in FA is also related to inhibited neural rosette differentiation in monkey embryonic stem cells (Chen et al., 2012b). |

| Vitamin B6 (PDX) | Pyridoxine was related to increased survival of neuronal cells in vitro by stimulation neurotransmitter release (Danielyan et al., 2011). Additionally, a study in rats shows that PDX deficiency caused diminished hippocampal weight and electrical activity, most likely due to poor myelination (Krishna and Ramakrishna, 2004). The catalytic form of vitamin B6 (pyridoxal phosphate) is also found in multiple parts of the brain and has its highest concentration in the olfactory tubercle (Ebadi, 1981). |

| Vitamin B5 (PA) | Inactivation of panthotenate kinases, which phosphorylates PA, is related to neurodegeneration diseases during childhood (Garcia et al., 2012). Nevertheless, no studies have been performed to elucidate the role of PA alone during brain formation throughout embryogenesis. |

| Vitamin B3 (NC) | Newborn mice injected with an antagonist of niacin showed damage in the central nervous system (CNS), and motor neurons as well as dorsal horn cells in the spinal cord showed signs of chromatolysis (Aikawa and Suzuki, 1986). However, no studies have been performed to elucidate the role of NC alone during brain formation throughout embryogenesis. |

| Vitamin B2 (RBF) | RBF deficiency reduced the levels of important components of the myelin membrane in adult rats (Ogunleye and Odutuga, 1989). However, no studies have been performed to elucidate the role of RBF alone during brain formation throughout embryogenesis. |

| Vitamin B1 (TM) | TM deficiency in rats caused abnormal growth of the hippocampus (Ba et al., 1996), and appears to affect myelinogenesis, axonal growth and synapsis formation (Ba, 2005). TM deffciency was also related to thalamus degeneration in alcoholics (Qin and Crews, 2013) |

| Vitamin H (BT) | Errors in biotin metabolism can cause enlargement of cerebral ventricles (Yokoi et al., 2009). |

AC, Ascorbic acid; BT, Biotin; CBL, Cobalamin; 25-(OH) D3, 25-hydroxyvitamin D3; 1,25-(OH)2D3, 1,25 hydroxyvitamin D3; FA, Folic acid (folate); MQN, Menaquinone; NC, Niacin; PA, Panthotenic acid; PDX, Pyridoxine; PQN, Phylloquinone; RA, Retinoic acid; RBF, Riboflavin; α-TC, α-Tocopherol; TM, Thiamine.

Using systems chemo-biology tools, we investigated different interactomic databases to elucidate the interplay between ethanol and different vitamins in the model organism Mus musculus. In addition, we compared transcriptomic data from available experimental studies that simulated maternal alcohol abuse and the effects of ethanol in the nervous system of the fetuses of M. musculus. Transcriptomic data originating from the adult M. musculus brain exposed to ethanol was also investigated to elucidate the main biological processes and changes in mRNA expression from ethanol over the short and long terms. Finally, the results gathered from systems chemo-biology analyses were used to develop interaction models for ethanol and vitamin metabolism, as well as to identify the gene expression changes caused by ethanol exposure in the nervous systems at different developmental stages and adulthood.

Materials and Methods

Interactome data mining and the design of chemo-biology networks

To design chemo-biology interatomic networks and to elucidate the interplay among neurodevelopment, vitamins, and ethanol, the metasearch engines STITCH 3.1 (http://stitch.embl.de) and STRING 9.05 (http://string-db.org) (Jensen et al., 2009; Snel et al., 2000) were used. All major active forms of vitamins (Table 1) commonly employed in commercial vitamin supplementation, as well as ethanol, were used as the initial seeds for network prospecting in STITCH. The STITCH software allows visualization of the physical connections between different biomolecules and chemical compounds, whereas STRING shows only biomolecules interactions (Kuhn et al., 2012). Each connection (edge) among biomolecules possesses a degree of confidence between 0.0 and 1.0 (with 1.0 indicating the highest confidence). The parameters used to prospect the networks for M. musculus in STITCH and STRING software were as follows: all prediction methods enabled, excluding text mining; 95 to 100 interactions (for each vitamin subnetwork for the ethanol subnetwork), resulting in a 2213-node network. In addition, a new network was developed to construct an interactome network for the microarray data for M. musculus, resulting in a network of 7395 nodes (Fig. 1); degree of confidence, medium (0.400); and a network depth equal to 1. The results gathered using these search engines were analyzed with Cytoscape 2.8.2 (Shannon et al., 2003) and Cytoscape 3.0. In addition, the GeneCards [http://www.genecards.org/] (Rebhan et al., 1997; Safran et al., 2010), KEGG [http://www.genome.jp/kegg/] (Carbon et al., 2009; Kanehisa and Goto, 2000), AmiGO 1.8 [http://amigo.geneontology.org/cgi-bin/amigo/go.cgi] (Carbon et al., 2009), Reactome [http://www.reactome.org] (Jupe et al., 2012), BioCyc [http://biocyc.org/] (Caspi et al., 2010), and QuickGO [http://www.ebi.ac.uk/QuickGO/] (Binns et al., 2009) search engines were also employed, using their default parameters.

FIG. 1.

Experimental systems chemo-biology workflow. In (A), the primary network is composed of 1287 nodes (14 vitamins, ethanol, and 1262 biomolecules). The nodes linked to the ethanol subnetwork are shown with red borders. The vitamins were selected and used as initial inputs for searching different small subnetworks that were merged into a single large interactome. (B) Secondary network composed of 2213 nodes (14 vitamins, ethanol, and 2198 biomolecules). The data for nodes associated with vitamin and ethanol metabolism were gathered from multiple databases and merged with the primary network. (C) Mus musculus-Ethanol-Network (MME-Network), composed of 7723 nodes (14 vitamins, ethanol, and 7708 biomolecules). The data gathered from the microarrays were collected from the GEO database and were then entered into STRING and merged with the secondary network. The MME-Network was further analyzed with Cytoscape 2.8.2 and 3.0.

Gene expression data for the interatomic networks

We evaluated the transcriptomic data gathered from the matrix file GSE43324 (available at Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) [http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo]) as follows: pregnant C57BL/6J mice treated with saline, where fetuses were euthanized at embryonic day 16 (E.16) and whole brains were removed (termed control group “b”), compared with pregnant C57BL/6J mice prenatally treated with intraperitoneal injections of ethanol (2.5 g/kg of ethanol in saline) during gestational days 14 and 16 (acute ethanol exposition; group “a”), followed by embryo euthanasia at E.16, as described by Janus and Singh (2013). A mean value of expression for each gene was generated for both groups “a” and “b”. In addition, a transcriptional analysis, derived from matrix file GSE34469, was performed using pregnant M. musculus treated with saline, where the adult offspring were euthanized at postnatal day 70 (termed control group “b”), and compared to pregnant M. musculus treated with ethanol injections (2.5 g/kg of ethanol in saline) twice on gestational days 8 and 11, where the adult offspring were sacrificed at postnatal day 70 (ethanol group “a”), as described by Janus et al. (2012). The same transcriptomic study compared pregnant M. musculus treated with saline, where the adults were sacrificed at postnatal day 70 and the whole brains were removed (termed control group “b”), and pregnant M. musculus treated with ethanol injections (2.5 g/kg of ethanol in saline) twice on gestational days 14 and 16, where the adult offspring were sacrificed at postnatal day 70 (ethanol group “a”).

Finally, data were gathered from another study derived from the matrix file GSE34549. Here, we compared M. musculus treated with 0.15 M saline alone as the control, where the adults were sacrificed at day postnatal 60 and the whole brains were removed (termed control group “b”), with M. musculus treated with ethanol injections (2.5 g/kg of ethanol in 0.15 M saline) twice on days 4 and 7, the adult mouse was sacrificed at postnatal day 60 (ethanol group “a”), as described by Kleiber (2012).

Additionally to the average expression values (already calculated with log 2) of the datasets, we applied Equation 1 (Castro et al., 2009), to value the relative expression, and the gathered data were overlaid in interactomes-derived clusters.

|

where a corresponds to the ethanol treated samples, and b indicates the control group. In this sense, the genes were considered overexpressed when 0.55<Z≤1.00; genes were considered underexpressed when 0.00<Z<0.45 and, at last, genes were considered nondifferentially expressed when 0.45<Z<0.55.

Different Venn Diagrams were created using the online tool Data Overlapping and Area-Proportional Venn Diagram [http://apps.bioinforx.com/bxaf6/tools/app_overlap.php] to visualize the number of over- and underexpressed genes shared among the networks.

Modular analysis of the main interactome network

The MME-Network (Fig. 1C) was analyzed in terms of the major clusters or module composition using the program Molecular Complex Detection (MCODE) (Bader and Hogue, 2003). MCODE is based on vertex weighting by the local neighborhood density and outward traversal from a locally dense seed protein, and isolates the dense regions according to parameters selected by the researcher (Bader and Hogue, 2003). The parameters for MCODE cluster finding were as follows: loops included; degree cutoff, 3; expansion of a cluster by one neighbor shell allowed (fluff option enabled); deletion of a single connected node from clusters (haircut option enabled); node density cutoff, 0.1; node score cutoff, 0.2; kcore, 2; and maximum network depth, 100. Each cluster generates a value of “cliquishness” (Ci), which is the degree of connection in a given group of proteins. Thus, the higher the Ci value, the more connected the cluster (Bader and Hogue, 2003).

Centrality analysis of the major resulting network

Centrality analysis was performed for the “secondary network” (Fig. 1B) using the program CentiScaPe 1.2 (Scardoni et al., 2009). In this analysis, the CentiScaPe algorithm evaluates each network node according to the node degree, betweenness, and closeness to establish the most “central” nodes within the network. Thus, the most topologically relevant node for a determined biochemical pathway or module can be obtained and further analyzed. In general terms, the closeness analysis (1) indicates the probability that any node in our network is relevant to another protein/chemical compound in a signaling network or its associated network (Scardoni et al., 2009), as determined using Equation 2:

|

where the closeness value of node v (Clo(v)) is determined by computing and totaling the shortest paths among node v and all other nodes (w; dist(v,w)) found within a network (1). The average closeness (Clo) score was obtained by calculating the sum of different closeness scores (Cloi) divided by the total number of nodes analyzed (N(v)) (Equation 3).

|

The higher the closeness value compared to the average closeness score, the higher the relevance of a specific node for the other nodes within the network/module. In turn, the betweenness indicates the number of the shortest paths that go through each node (Equation 4) (Newman, 2005; Scardoni et al., 2009):

|

where σsw total number of the shortest paths from node s to node w, and σsw (v) is the number of those paths that pass through the node. The average betweenness score (Bet) of the network was calculated using Equation 5, where the sum of different betweenness scores (Beti) is divided by the total number of nodes analyzed (N(v)):)].

|

Thus, nodes with high betweenness scores compared to the average betweenness score of the network are responsible for controlling the flow of information through the network topology. The higher a node's betweenness score, the higher the probability that the node connects different modules or biological processes, such nodes are called bottleneck nodes.

Finally, the node degree (Deg(v)) is a measure that indicates the number of connections (Ei) that involve a specific node (v) (Equation 6):

|

The average node degree of a network (Deg) is given by Equation 7, where the sum of different node degree scores (Beti) is divided by the total number of nodes (N(v)) present in the network:

|

Nodes with a high node degree are called hubs (Scardoni et al., 2009) and have key regulatory functions in the cell.

Gene ontology analyses of the major resulting network

The modules generated by MCODE were further studied by focusing on major biology-associated processes using the Biological Network Gene Ontology (BiNGO) 2.44 Cytoscape 2.8.3 plugin (Maere et al., 2005), available at http://www.cytoscape.org/plugins2.php#IO_PLUGINS. The degree of functional enrichment for a given cluster and category was quantitatively assessed (p value) using a hypergeometric distribution. BiNGO provides p values assessed by functional themes that are overrepresented on a given set of genes (e.g., clusters) (Maere et al., 2005). Multiple test correction was also assessed by applying the false discovery rate (FDR) algorithm (Benjamini and Hochberg, 1995), which was fully implemented in BiNGO software at a significance level of p<0.05. The most statistically relevant processes were taken into account when developing the interaction model.

Results

Design of the interactome networks, topological analysis and transcriptomic data for Mus musculus

Systems chemo-biology tools allow prospecting of new drug targets and interaction between chemical compounds and biological networks (Chandra and Padiadpu, 2013; Csermely et al., 2013; Schneider and Klabunde, 2013). Our group has successfully employed systems chemo-biology to discover potential new anti-tumor drugs for gastric cancer (Rosado et al., 2011) and to understand the molecular pathways underlying fetal malformations associated with tobacco abuse during pregnancy (Feltes et al., 2013).

We first prospected small networks related to (i) the main active forms of each vitamin (Table 1), named the “primary network” (Fig. 1A), and (ii) metabolic-associated pathways for each vitamin and for ethanol in the STITCH and STRING databases for M. musculus, named the “secondary network” (Fig. 1B). Once gathered, these small networks were merged with the transcriptomic data in one large network named the M. musculus-ethanol network (MME-Network) (Fig. 1C).

The large MME-Network (Fig. 1C) was overlaid with four different transcriptomic datasets related to mouse offspring exposed to ethanol (Supplementary Table S1; Supplementary Material is available online at www.liebertpub.com). For this purpose, we used the public transcriptomic data available in the GEO database regarding M. musculus females exposed to the same concentration of ethanol (2.5 g ethanol/kg) during pregnancy and postnatal stage to simulate acute ethanol exposure. We also evaluated the late-life transcriptomic effects of ethanol exposure in the litters of pregnant females, which is necessary for understanding the cognitive and learning impairments observed in young adults with FAS (O'Leary, 2004). Thus, under- and over-upregulated genes were selected for transcriptome landscape analysis by overlaying these data on the following networks: (i) Prenatally-Exposed-Network (PE-Network; Fig. 2A), where the fetuses were exposed to ethanol during development (E.14 and E.16) and euthanized before birth (E.16), as described in the transcriptomics series GSE43324; (ii) Postnatal-Exposed MME-Network (PSE-Network; Fig. 2B), with pups exposed to ethanol (postnatal days 4 and 7) and euthanized at adult day 60 as indicated in GSE34549; (iii) Early Gestation-Exposed-Postnatal-Network (EGEP-Network; Fig. 2C), referent to transcriptomics series GSE34469 where the fetuses were exposed to ethanol during development (E.8 and E.11) and euthanized at adult day 70; and (iv) Late Gestation-Exposed-Postnatal-Network (LGEP-Network) (Fig. 2D), referent to the series GSE34469, in which the fetuses were exposed to ethanol during development (E.14 and E.16) and euthanized at adult day 70.

FIG. 2.

Network landscape analysis of microarray data from Mus musculus embryos exposed to ethanol (MME-Network). In (A), Prenatally Exposed (PE-) Network, derived from the transcriptomic analysis of prenatally ethanol-exposed embryonic brains from mice euthanized at E.16. (B) Postnatal-Exposed Network (PSE-Network), derived from a transcriptomic analysis of brains of postnatal ethanol-exposed mice, euthanized at day 70. (C) Early Gestation-Exposed-Postnatal-Network (EGEP-Network), derived from a transcriptomic analysis from the brains of prenatally ethanol-exposed embryos (E.4 and E.7), euthanized at postnatal day 60. (D) Late Gestation-Exposed-Postnatal-Network (LGEP-Network), derived from a transcriptomic analysis from the brain of prenatally ethanol-exposed embryos (E.14 and E.16), euthanized at postnatal day 60.

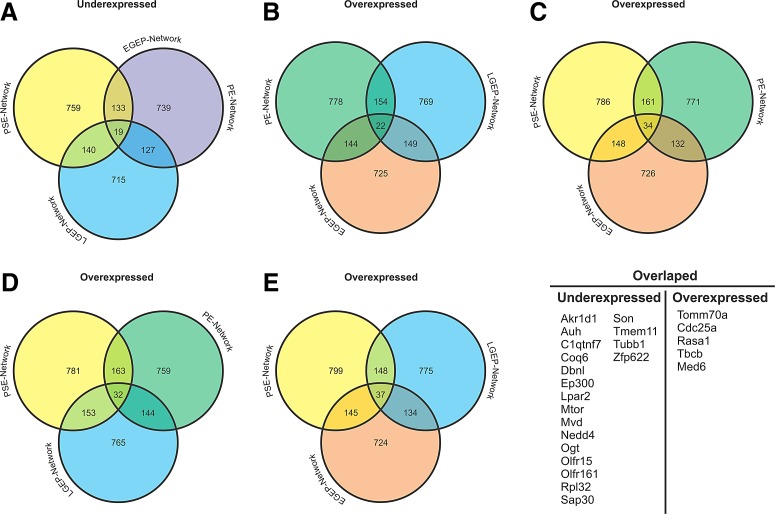

Once the networks were overlaid with transcriptomic data, we select all those genes whose expression were similar in all treatment conditions (Fig. 3), allowing us to further analyze what genes could be commonly associated with acute and chronic ethanol exposure. In this sense, 19 genes were identified that were underexpressed in the PE-, LGEP- and PSE-Networks (Fig. 3A). Interestingly, these same 19 genes were present in the EGEP-, LGEP- and PSE-Networks (Fig. 3A).

FIG. 3.

Overlaps between the under- and overexpressed genes in all transcriptomic datasets. The green circle represents the Prenatally-Exposed (PE-Network, mice prenatally exposed to ethanol during E.14 and E.16 and euthanized at E.16). The yellow circle indicates the Postnatally-Exposed Network (PSE-Network, in which the dams were exposed to ethanol at postnatal days 4 and 7, and the offspring were euthanized at adult day 60). By its turns, the blue circle refers to the Late Gestation-Exposed-Postnatal-Network (LGEP-Network, in which the fetuses were exposed to ethanol during development at E.14 and E.16 and euthanized at adult day 70). The orange circle represents the Early Gestation-Exposed-Postnatal-Network (EGEP-Network, in which fetuses were exposed to ethanol at E.8 and E.11 and euthanized at adult day 70). Finally, the purple circle represents a fusion of the EGEP- and PE-Networks because they displayed the same underexpressed genes in the overlaps. (A) Overlap of the underexpressed genes, which showed 19 genes in common (displayed in the table on the right side of the figure); (B) Venn diagrams of the overexpressed genes of the PE-, EGEP-, and LGEP-Networks, sharing 22 genes; (C) Overexpressed genes overlapping among the PE-, PSE-, and EGEP-Networks, which showed 34 shared nodes; (D) Venn diagram showing the overlap between the overexpressed genes among the PE-, PSE-, and LGEP-Networks, with 32 shared genes; (E) Overlaps between the overexpressed genes in the LGEP-, PSE-, and EGEP-Network, revealing 37 shared nodes. The common nodes among the Venn diagrams of B–E are also listed in the table on the right side of the figure.

Next, we generated another set of diagrams for overexpressed genes (Figs. 3B–E). The data show only five overexpressed genes that are shared among all transcriptomic series (Fig. 3B–E). The relationship of these genes and their probable roles during pregnancy, neurogenesis, and vitamin metabolism will be discussed further. Nevertheless, the fact they are present in different ethanol exposure experiments in individuals of different ages suggests that they are closely related with the long-term effects of ethanol in brain development and physiology. In addition, we evaluated the “secondary network” (Fig. 1B) for the most topologically relevant nodes.

In a scale-free biological network, the most topologically relevant nodes are the hub-bottlenecks (HBs) (Yu et al., 2007) because they combine the bottleneck function (nodes that connect different clusters within a network and, consequently, display a betweenness score above the network average) and the property of hubs (nodes with a number of connections above the average node degree value of the network). Thus, HBs are critical nodes in a biological network (Yu et al., 2007). In our analysis, we observed 349 HB nodes in the “secondary network” of M. musculus (Fig. 1B). Of the 349 HBs in the M. musculus secondary network, 174 (49.8%) were connected to the ethanol subnetwork (Fig. 4A).

FIG. 4.

Subnetworks derived from hubs-bottleneck (HB) analysis. Nodes colored with red borders are those found in the M. musculus-Ethanol Network (MME-Network). (A) M. musculus HBs; (B) HB displaying the expression data from the Prenatally Exposed Network (PE-Network); (C) HBs displaying the expression data from Postnatal-Exposed Network (PSE-Network); (D) HBs displaying the expression data from the Early Gestation-Exposed-Postnatal-Network (EGEP-Network); (E) HBs displaying the expression data from the Late Gestation-Exposed-Postnatal-Network (LGEP-Network). The Venn diagrams below each network display the overlaps between the indicated networks.

To understand how ethanol interacts with vitamins and the different proteins studied, we evaluated each transcriptomic network for the presence of modules or clusters, which allowed us to discover major biochemical pathways related to ethanol-vitamin metabolism. We found 15 modules above our cutoff score. Once the modules were obtained, a gene ontology (GO) analysis was performed. Biological processes that are important for neurodevelopment and neurobiological functions as well for vitamin metabolism that were present in each cluster were listed (Supplementary Table S2). The GOs relevant for vitamin, alcohol, and neurological function in Supplementary Table S2 are green. In addition, processes that were related to inflammation are blue, and the GOs related to amino acid metabolism are purple. Likewise, we performed additional GO analyses for the selected over- and underexpressed genes of each transcriptomic set. The main observed GOs were inflammation, synapses and neurotransmitter release, glutamate synthesis and metabolism, calcium ion signaling, and homeostasis and neurodifferentiation, and the summary of the GO information gathered in each network for over- and underexpressed genes is found in Table 2 (Fig. 3; for full data of the over- and underexpressed genes GO, see Supplementary Tables S3–6). Our analysis excluded GOs that were not associated with significant bioprocesses due to a lack of data or that were too general (e.g., the regulation of a biological process, regulation of transcription, or metabolism of organic substances). In addition, processes that were repeated among the GOs of over- and underexpressed genes were deleted. As expected, in the overexpressed GOs of different networks, the bioprocess of alcohol metabolism and processes associated with neuron physiology and function were highly expressed because the transcriptomic data were gathered from murine neural tissues (Supplementary Tables S3–S6).

Table 2.

Major GO Terms Referent to Over- and Underexpressed Genes in the Interactomes for Each Transcriptomic Sets

| Network (expression) | GO | Corr p-value | x | Proteins |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PE-Network (overexpressed) | Negative regulation of apoptosis | 4.6×10−13 | 47 | BMI1|SNCB|XIAP|PAFAH2|PRDX3|ITSN1|ADORA1|WT1| |

| PCGF2|BDNF|CASP3|ATG5|LHX3|DNAJC5|MYC|HELLS| | ||||

| CD27|IHH|SPP1|FN1|ZC3HC1|MSH2|IL7|RXFP2|GRIN1| | ||||

| SPHK1|NR4A2|PROKR1|LIG4|DAPK1|ATF5|NME5|MNAT1|NOTCH1|EYA1|GNAQ|SFRP2|HIPK2|CX3CR1|SIX1|MTR| | ||||

| CFDP1|BMP7 | ||||

| Vasculature development | 4.1×10−7 | 31 | FGFR2|CAV1|NRP1|FGF9|LEPR|MMP2|WT1|CDH5| | |

| CTNNB1|SEMA5A|ATG5|APOE|TDGF1|GATAD2A|RHOB|NOS3|PLXND1|IHH|FN1|KLF5|SMAD5|SPHK1|EFNB2| | ||||

| GALT|FZD5|MNAT1|NOTCH1|PROK1|JUN|NTRK2|ZFPM2 | ||||

| Aging | 6.3×10−7 | 14 | MSH6|GNAO1|MSH2|POU1F1|GHRHR|NCAM1|CDKN2A| | |

| CYP27B1|APOE|MTR|MNT|SLC18A2|INPP5D|HAP1 | ||||

| Negative regulation of cell communication | 9.5×10−7 | 28 | HCRT|CAV1|FGFR3|GRIK1|FGF9|MBIP|ADORA1|GPC3| | |

| TDGF1|SKIL|INPP5D|AXIN1|IHH|PTPRC|AVP|PTPRF|PRKCD|CISH|SIGIRR|GRB10|CCND1|NOTCH1|BMPER|SFRP2|AVPR1A|BMP7|DRD1A|GRB14 | ||||

| Negative regulation of neuron apoptosis | 1.06×10−5 | 12 | BDNF|SNCB|XIAP|MSH2|HIPK2|SIX1|GRIN1|NR4A2| | |

| DNAJC5|PRDX3|LIG4|ITSN1 | ||||

| PE-Network (underexpressed) | Post-translational protein modification | 9.8×10−10 | 76 | CDK19|CDC14B|STK35|PTPN22|RPS6KB2|LPAR2|LATS2| |

| BTK|AKT1|GPX1|SIN3B|PRMT1|CRY2|PLOD1|SH2D1B1| | ||||

| PRKACA|FGF2|MAP2K7|EGFR|IRAK2|SRPK2|CAMK1G|PTPRM|PHKG2|CDK8|SOCS7|ARL6|PRKCQ|PPP1CA|EP300|PIAS4|PDGFRB|PIAS2|FBXO15|EIF2AK2|NSD1|UBE2T| | ||||

| MAP3K11|RAB3B|SRM|ERBB3|BRSK2|MAPKAPK3| | ||||

| TRIB3|KIT|EPHB3|CD74|GCKR|VRK1|MAP3K3|C1QTNF2|PKD1| | ||||

| PPP3CA|TCF3|PIK3R1|PTPN18|FLT4|TGFBR1|PTPRA|CS| | ||||

| PDE6G|EPHA1|RPS6KA1|GCK|PLK1|NEDD4|RNF2|NTRK1|PRKAR1A|GRK5|MTOR|MAPK8IP1|MERTK|IKBKB| | ||||

| BMPR1B|OPN4 | ||||

| Calcium ion homeostasis | 9.2×10−9 | 25 | GNA13|CCL2|PTGER3|PMCH|IL6ST|PIK3CB|HC|GRIK2| | |

| TRHR|PTH1R|NMB|PPOX|KCNA5|NPY1R|ITGB3|CSRP3| | ||||

| BAK1|HRH3|GCK|PLCG2|RYR1|TBXA2R|EPOR|BANK1| | ||||

| IL2 | ||||

| Retinoid metabolic process | 2.6×10−7 | 15 | EBP|CYP11A1|MVD|CYP11B1|AMACR|LSS|CPN2| | |

| SC4MOL|CYP17A1|INSIG2|AKR1C6|INSIG1|BMPR1B| | ||||

| FGF2|AKR1D1 | ||||

| c-AMP- mediated signaling | 1.9×10−6 | 15 | P2RY12|GNA13|ADRB3|NPB|ADRB1|PTGER3|ADCY8| | |

| S1PR4|ADCY5|PTH1R|LHCGR|HTR4|RAPGEF4|FSHR| | ||||

| OPRD1 | ||||

| Cognition | 5.9×10−4 | 80 | GLRA1|ADCY8|OLFR1254|OLFR703|OLFR295|UCHL1| | |

| RPE65|OLFR808|NR2E1|OLFR1016|GPX1|OLFR1469| | ||||

| OLFR692|OLFR1054|OLFR554|OLFR1427|OLFR228|PLCB2|GJE1|OLFR1058|OLFR1152|OLFR461|OLFR836|WNT10B| | ||||

| MYO6|OLFR460|OLFR1247|OLFR167|ESR2|OLFR1348| | ||||

| OLFR161|AAAS|OLFR399|OLFR59|OLFR11|OLFR96| | ||||

| OLFR15|OLFR90|OLFR392|OLFR1046|OLFR1045|OLFR16|OLFR1104|GJA10|OLFR1234|C3|OLFR1085|OLFR1442| | ||||

| OLFR829|OLFR1500|PPT1|KIT|OLFR137|OLFR729| | ||||

| OLFR437|OLFR821|OLFR578|OLFR381|ACE|HRH3| | ||||

| OLFR1176|OLFR720|OLFR1094|OLFR502|OLFR1226| | ||||

| OLFR282|OLFR1451|OLFR716|NPY1R|DBH|PDE6G| | ||||

| OLFR1458|OLFR2|OLFR449|OLFR993|OLFR1490|OLFR376|OLFR73|OPN4|OLFR1122 | ||||

| EGEP-Network (overexpressed) | Negative regulation of cell death | 7.5×10−6 | 30 | RBP4|TSPO|CAV1|NR2E3|PDX1|IL15|PTTG1|SLFN3|GLI3| |

| ADORA1|TGFB2|SLFN2|LIF|BDNF|GPC3|CDKN2B|HSF1| | ||||

| GATA3|RARA|ITCH|BMP2|WNT10B|JARID2|RALBP1| | ||||

| SMAD3|GJB6|CTH|PLA2G2A|GLMN|WNT11 | ||||

| EGEP-Network (underexpressed) | Positive regulation of axonogenesis | 7.4×10−6 | 9 | NTRK3|APC2|TIAM1|PLXNB1|ADNP|PAFAH1B1|NEFL| |

| DSCAM|NGF | ||||

| Positive regulation of cell communication | 4.6×10−5 | 25 | IL6|FKBP8|UTS2|PPARD|CARD9|ERBB4|CD3E|TAC1| | |

| ITGA2|JAG1|DGKI|MBD2|FURIN|NCAM1|ACVR1B| | ||||

| CDKN2A|MYD88|CD36|AGT|EXOC4|ADAM17|IL1B|NMU|CHUK|GHR | ||||

| Response to axon injury | 4.1×10−4 | 5 | LAMB2|BCL2|BAX|NEFL|MMP2 | |

| LGEP-Network (overexpressed) | Positive regulation of apoptosis | 1.3×10−13 | 42 | USP7|CDK5R1|TLR4|RRM2B|NR3C1|ZBTB16|LPAR1| |

| PMAIP1|MMP2|IL10|ALDH1A2|NOD1|ALDH1A3|TICAM1|PCSK9|DIABLO|INPP5D|FAS|TRAF6|CASP2|MAP2K7| | ||||

| MAP2K6|CCAR1|COL18A1|PRKCA|TXNIP|IL2RA|PTPRF| | ||||

| GRIN1|BRCA2|IDO1|ATM|CIDEC|NOTCH2|NOTCH1| | ||||

| ADRB2|PSEN1|EEF1E1|ENDOG|PDE5A|WNT11|LRP5 | ||||

| TNF-mediated signaling pathway | 1.9×10−4 | 5 | TRAF2|TNFRSF11A|TNFSF11|KRT18|FAS | |

| LGEP-Network (underexpression) | Positive regulation of cell communication | 4×10−9 | 32 | DCC|FGF18|FKBP8|CAV1|FGF9|CSF1|FGF10|LPAR2|EIF2A|ITGB3|TLR6|ITSN1|SRC|PHIP|ACVR1B|CD44|IFNG|GATA4|RBCK1|IL1A|CHUK|IL4|BMP4|DIXDC1|KL|CENPJ|KITL| |

| WNT7B|CCR2|JAK2|MTOR|GHSR | ||||

| Lamellipodium assembly | 7.2×10−4 | 5 | NCK1|SH2B1|CPB2|NCKAP1|FGD4 | |

| PSE-Network (overexpressed) | Negative regulation of apoptosis | 2.3×10−10 | 39 | XRCC5|STIL|FGFR1|XIAP|SNCA|ELK1|NFKB1|BDKRB2| |

| ADORA1|PHIP|BDNF|PTK2|CD44|ATG5|BCL2|AGT| | ||||

| PPP2CB|VNN1|NKX2-5|ERCC2|APC|BMP4|EEF1A2|SKP2| | ||||

| GIF|PROKR1|ESR2|TAX1BP1|DAPK1|RAD51|EYA1| | ||||

| TNFSF13B|IGBP1|MTR|CFDP1|TRP73|APIP|WNT7A| | ||||

| NGF | ||||

| Proteolysis | 1.1×10−4 | 41 | C2|MASP1|CNDP2|UBE3A|MMP8|ENPEP|MMP2|PSMB4| | |

| CYLD|CUL7|PPP2CB|USP34|CUL1|CAPN7|SEC11C|UFD1L|FBXO2|SKP2|CAPN2|FURIN|AFG3L1|PSMB8|PSMB9| | ||||

| FOLH1|BLMH|CUL4A|TMPRSS11E|CLPP|PRCP|CTSC| | ||||

| ADAM12|TBL1X|CTSH|PMPCA|PMPCB|NCLN|PLAU | ||||

| Tachykinin receptor signaling pathway | 2.1×10−4 | 4 | UQCRC2|METAP1|USP8|UQCRC1|APTACR2|TACR1|TAC1|TAC2 | |

| PSE-Network (underexpressed) | Axonogenesis | 5.2×10−7 | 24 | FGFR2|ENAH|CDK5R1|WNT3A|UCHL1|KIF5C|DPYSL5| |

| RTN4R|STXBP1|PIP5K1C|SLIT1|CXCL12|CTNNA2| | ||||

| NRCAM|ROBO1|CXCR4|MNX1|RIT1|SEMA3A|BMPR1B| | ||||

| BOC|APBB1|GAP43|KALRN | ||||

| Cytosolic ion calcium homeostasis | 1.04×10−5 | 16 | CALCR|MCHR1|RXFP3|EDN1|PTH1R|NMB|CXCR3|ITPR3|EDNRA|GCK|AGTR1A|RYR1|TGM2|UTS2R|GLP1R| | |

| CACNA1A | ||||

| Regulation of c-AMP biosynthetic process | 9×10−5 | 13 | CALCR|ADCY2|ADCYAP1R1|EDN1|PTH1R|TIMP2| | |

| EDNRA|S1PR3|HTR1B|S1PR4|HTR7|PTH|GLP1R | ||||

| Synaptic transmission | 7.6×10−4 | 21 | GJD2|MYO5A|STX1A|HTT|GABRA6|MAOB|PPYR1| | |

| CLSTN1|STXBP1|SNAPIN|NTSR2|CTNNA2|CTNNB1| | ||||

| HTR1B|CAMK4|HTR7|HRG|VAMP2|TPR|SNAP25| | ||||

| CACNA1A |

x, number of proteins associated with a given GO in the network.

In addition, the modularity and GO combined analysis for the MME-Network reveled that all modules, with exception of cluster 9 (Supplementary Table S2), were associated with neurodevelopment, alcohol metabolism, and/or vitamin metabolism, indicating that those bioprocess are closely related. Because these clusters are defined by highly dense, interconnected regions, the fact that they show close relationships with those processes may be useful for understanding how FAS affects neurodevelopment through vitamin metabolism.

Centralities analysis and overlaps among the ethanol-exposed groups

We also compared the under- and overexpressed genes in the centrality results of the PE-Network versus PSE-Network analyses (Fig. 4B and 4C, respectively) to understand the main differences between alcohol abuse in the developing organism and in the adult individual. We also evaluated the results of the EGEP-Network versus the LGEP-Network analyses (Fig. 4D and 4E) to observe the changes in HB status in adult individuals exposed to ethanol at different stages of embryonic development (Fig. 4).

The centrality analysis of the secondary network (Fig. 1C), the overlaps among the under- and overexpressed genes of the PE-, EGEP-, LGEP- and PSE-Networks, and the overlaps of the expression of the HB subnetworks (Fig. 4B-E) resulted in a list of 51 potential targets involved in FAS progression (Table 3). Our results for the under- and overexpressed genes are listed in Table 3.

Table 3.

List of Overlapping Nodes Found in the Under- and Overexpressed Genes of All Four Networks (Fig. 3) and Among the HB Networks (Fig. 4)

| Protein | Identity | Role in neurodevelopment and/or neurological function | Expression |

|---|---|---|---|

| Adcy5 | Adenylate cyclase | NDL | Underexpressed |

| Akr1d1 | Aldo-Keto reductase | NDL | Underexpressed |

| Akt1 | Kinase | Involved in neuronal differentiation (Park et al., 2012). | Underexpressed |

| Aldh1a2 | Aldehyde dehydrogenase | Involved in the patterning of the CNS and neural tube (Marei et al., 2012; Strate et al., 2009). Could also be related to hindbrain defects in Xenopus laevis (Vitobello et al., 2011). | Underexpressed |

| Aldh1b1 | Aldehyde dehydrogenase | Downregulated by ethanol during early nerulation (Zhou et al., 2011). | Underexpressed (EGEP-LGEP) |

| Overexpressed (PE-PSE) | |||

| Aprt | Aphosphoribosyl-transferase | Aprt expression increases in course of neuron maturation in cell cultures (Brosh et al., 1990) | Underexpressed |

| Auh | Enoyl-CoA hydratase | Role in neural survival through its action on AU-rich elements (ARE) (Kurimoto et al., 2009). | Underexpressed |

| C1qtnf7 | C1q and TNF related protein | NDL | Underexpressed |

| Cd3g | T-Cell surface glycoprotein | NDL | Underexpressed |

| Chuk (IκBα) | Serine/threonine kinase | Expression of this protein blocks self-renewal and induces neurodifferentiation (Khoshnan and Patterson, 2012). | Underexpressed |

| Coq6 | Monooxygenase | NDL | Underexpressed |

| Cyp1a1 | Cytochrome P450 family | Related to xenobiotic metabolism in the brain, where this protein was found with high activity in glial cells (Kapoor et al., 2006) and also abundant in the cerebral cortex and cerebellum (Iba et al., 2003). | Underexpressed (EGEP-LGEP) |

| Overexpresed (PSE) | |||

| Cyp2c70 | Cytochrome P450 family | NDL | Underexpressed |

| Cyp2d10 | Cytochrome P450 family | NDL | Underexpressed |

| Dbn1 | Actin-binding adapter protein | Plays a role in spine formation and synaptogenesis (Park et al., 2009) | Underexpressed |

| Ep300 | Histone acetyltransferase | Expressed in multiple regions of the brain, including hippocampus, cerebral and cerebellar cortices and medulla oblongata (Tan et al., 2009) | Underexpressed |

| Gart | Phosphoribosyl-glycinamide Formyltransferase | Polymorphism in this gene was related to mouse neural tube defects (Pangilinan et al., 2012). This protein is also related to prenatal cerebellar development (Brodsky et al., 1997) | Underexpressed |

| Ggt1 | Gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase | NDL | Underexpressed |

| Lpar2 | Lysophosphatidic acid receptor | LPA has been implicated in neurogenesis of the CNS, targeting neural progenitors, neurons, astrocytes, microglia, oligodendrocytes and Schwann cells (Goldshmit et al., 2010) | Underexpressed |

| Mtor | Serine/Threonine kinase | Involved in synaptic plasticity, neuron survival and repair against brain injuries (Russo et al., 2012) | Underexpressed |

| Mvd | Mevalonate pyrophosphate decarboxylase | NDL | Underexpressed |

| Ncoa3 (Src3) | Histone acetyltransferase | Expressed at high levels in the hippocampus (Tetel, 2009). | Underexpressed |

| Nedd4 | E3 ubiquitin-protein ligase | NDL | Underexpressed |

| Ogt | O-Linked N-acetylglucosamine transferase | Cellular nutrient sensor, which may play a role in placental protection and in neurodevelopment by protecting the brain from insults such as nutrient deficiency (Howerton et al., 2013) | Underexpressed |

| Olfr15 | Olfactory receptor | NDL | Underexpressed |

| Olfr161 | Olfactory receptor | NDL | Underexpressed |

| Pik3cd | Kinase | NDL | Underexpressed |

| Rpl32 | Ribosomal protein | NDL | Underexpressed |

| Sap30 | Sin3A-associated protein | NDL | Underexpressed |

| Shmt1 | Serine hydroxymethyl-transferase | Related to prepulse inhibition in mice (Maekawa et al., 2010). Lack of Shmt1 also results in neural tube defects in mice (Beaudin et al., 2011) | |

| Tmen11 (PMI) | Transmembrane protein | Involved in Drosophila melanogaster synapse formation and lifespan (Macchi et al., 2013) | Underexpressed |

| Tubb1 | Tubulin, Beta 1 Class VI | Protein restricted to regions of the peripheral and central nervous system during early-differentiating neurons in zebrafish (Oehlmann et al., 2004). | Underexpressed |

| Zfp622 | Zinc finger protein | NDL | Underexpressed |

| Son | Splicing cofactor | Expression of Son was related to neurogenesis during embryogenesis and postnatal brain (Ahn et al., 2011). | Underexpressed |

| Aldh1a1 | Aldehyde dehydrogenase | ALDH1A1 expression appears in more differentiated parts of the developing brain such as cerebellar vermis or fetal white matter (Adam et al., 2012) | Overexpressed |

| Cad | Trifunctional protein (carbamyl phosphate synthetase, aspartate transcarbamylase and, dihydroorotase). | Cad protein was observed to be elevated during rat and hamster prenatal brain formation and hamster early postnatal brain development (Cammer and Downing, 1991). The authors argue that Cad is related to pyrimidine synthesis in astrocytes and in the grey matter. | Overexpressed |

| Carm1 | Methyltransferase | Expression of this protein, inhibits HuD, a protein that is important for neurodifferentiation, synaptogenesis and learning and memory (Lim and Alkon, 2012). | Overexpressed |

| Cdc25a | Phosphatase | NDL | Overexpressed |

| Cth | Broad substrate specificity (deaminase, dehydratase, lyase, desulfhydrase) | Polymorphisms in this gene were related to autism (Bowers et al., 2011). | Overexpressed |

| Dlat | Pyruvate dehydrogenase | NDL | Overexpressed |

| Dut (DUTPase) | Nucleotido-hydrolase | Expressed in the prenatal rat brain, DUTPase might is responsible to maintain the low frequency of dUMP incorporation into DNA (Focher et al., 1990). | Overexpressed |

| Hmgcr | Transmembrane glycoprotein | Overexpression of this protein, in combination to underexpression of ABCA1 (not present in our networks) is related to increased risk of Alzheimer's disease (Rodriguez-Rodriguez et al., 2009). | Overexpressed |

| Ikbkg | Kinase | NDL | Overexpressed |

| Med6 | Transcription factor | NDL | Overexpressed |

| Mtr | Methyltransferase | Uses cobalamin (CBL) as co-factor, where deficiency of CBL causes dramatic degrease of Mtr (Gueant et al., 2013). In the same article is discussed that CBL deficiency during mice is associated with impaired memory. | Overexpressed |

| Ncoa2 | Histone acetyltransferase | Overall, Ncoa2 expression is not detectable in the brain but is expressed in the anterior pituitary (Meijer et al., 2000) and in high levels in the dentate gyrus during adult stages but low on prenatal stages (Schmidt et al., 2007) | Overexpressed |

| Rasa1 | GTPase-activating protein | NDL | Overexpressed |

| Tbcb | Tubulin folding cofactor B | Overexpression of TBCB results in abnormalities in the growth cone morphology, later causing neuronal degeneration (Lopez-Fanarraga et al., 2007) | Overexpressed |

| Tomm70a (KIAA0719) | Translocase | Regulated by thyroid hormone, which can lead to brain malformations when at abnormal levels (Alvarez-Dolado et al., 1999). | Overexpressed |

| Uox | Urate oxidase | Uox expression is correlated to diminished neuroprotective effects of urate in astrocytes and neurons (Cipriani et al., 2012). Its expression is also related to exacerbate the lesions caused by 6-hydroxydopmaine in dopaminergic neurons (Chen et al., 2013). | Overexpressed |

The full description of the most relevant targets and proteins are discussed along the study.

NDL, No Direct Link.

Among the selected targets is AU-rich hydrolase (AUH) (Table 3), a protein that binds to AU-rich elements (ARE) in RNAs (Kurimoto et al., 2009). AUH mRNA lacks ARE and is upregulated in the mouse brain when mood stabilizers (e.g., lithium carbonate and valproic acid) are administered. Interestingly, these drugs upregulate the expression of ARE-containing mRNAs, such as the apoptotic inducer BCL2 (Kurimoto et al., 2009). This correlation indicates that AUH may promote neuron survival against apoptosis. Because AUH is downregulated in our networks, it becomes an important target in understanding FAS-induced neuronal damage. Moreover, debrin 1 (Dbn1) was also found among the underexpressed genes in the prospected networks (Table 3). Dbn1 is related to the formation of neuronal gap junctions in the mesencephalic trigeminal nucleus, which is crucial for synapse function through receiving inputs from nerve terminals and neurotransmitters (Park et al., 2009). Synapse plasticity, and protection against brain injury (Russo et al., 2012) is also related to mTor expression, which was reduced in the four networks (Fig. 2A-D). Changes in the mTor pathway have also been linked to neurological diseases such as Alzheimer's and Parkinson's diseases (Russo et al., 2012). mTor has been linked to synaptic plasticity, both in long term potentiation in the hippocampus and by coordinating protein synthesis (Russo et al., 2012). The co-activator-associated arginine methyltransferase (Carm1) was also among the overexpressed genes in the overlaps between the HB subnetworks of the PE- and PSE-Networks (Fig. 4; Table 3). Carm1 was found to be responsible for the inhibition of HuD, a protein that is related to synaptogenesis, learning, memory, and neurodifferentiation (Lim and Alkon, 2012). This finding indicated that some of the highly topologically relevant proteins affected by ethanol are associated with synaptic plasticity, consistent with FAS-associated learning and memory impairments.

Proteins that belong to the tubulin family, such as Tub11, or that affect tubulin mechanisms, such as Tcbc and Son, were among our potential targets. Both Son, a splicing cofactor linked to mitotic spindle assemble (Ahn et al., 2011), and Tub11, a tubulin Beta 1 class VI, were among our underexpressed genes. Both proteins appear to be present during neurogenesis in embryonic development and are related to the differentiation of different brain regions (Ahn et al., 2011; Oehlmann et al., 2004). We also identified Tbcb among the overexpressed genes in our networks (Table 3). Tbcb is a tubulin-folding cofactor, primarily associated with axonogenesis, which can cause brain malformations when overexpressed (Lopez-Fanarraga et al., 2007). These results show that ethanol exposure induced the deregulation of tubulin and tubulin-associated proteins during neurodifferentiation.

The protein Gart was also among the overlaps of HB subnetworks in the underexpressed datasets for the PE- and PSE-Networks (Fig. 4). This protein appears to be expressed at higher levels in the prenatal cerebellum as compared to adults (Brodsky et al., 1997). More interestingly, human neuroblastoma cells treated with 6-hydroxy-dopamine, which mimic the effects of Parkinson's disease, showed Gart to be downregulated (Noelker et al., 2012). The authors also propose that downregulation of Gart could lead to neuron apoptosis. This is consistent with our data, which shows that in the PE- and PSE-Networks the process of negative regulation of apoptosis and neuron apoptosis to be overexpressed (Table 2). These observations indicate that Gart downregulation by ethanol during the early stages of development could lead to learning and memory impairments in adults.

The coactivator Ncoa3 (SCR3) is also present in the overlaps among the downregulated gene datasets in the HB subnetwork of the PE- and PSE-Networks (Fig. 4). Ncoa3 is expressed in the hippocampus and is related to retinoic acid (RA) signaling (Kashyap and Gudas, 2010). Retinoic acid (RA) is a vitamin A derivative involved in neural differentiation and neurogenesis (Chen et al., 2012) (Table 1). The presence of RA mediated the release of coactivators, leading to the transcriptional activation of retinoic acid receptors (RARs) (Kashyap and Gudas, 2010). In addition, Ncoa3 is a downstream mediator of vitamin D (VD) signaling (Ahn et al., 2009). These results indicate that ethanol is able to reduce VD and RA signaling through the downregulation of Ncoa3 in the prenatal brain, affecting brain regions such as the hippocampus. Moreover, Shmt1is another gene downregulated in the same network overlaps that is also related to vitamin metabolism and is a serine hydroxymethyltransferase involved in folate metabolism (Beaudin et al., 2011). The authors note that Shmt1(+/-) mice showed impairment in neural tube closure and that Shmt1 expression is also coordinated by RA, indicating that this protein could have an important role in ethanol-mediated brain defects.

Discussion

Interpolation between ethanol and vitamin metabolism during neurodevelopment

Considering the data gathered from systems biology analyses, we performed a more detailed evaluation of the major vitamin-related pathways and neurodevelopment processes affected by the ethanol in the following sections.

Retinol signalization, folic acid metabolism, synapsis induction, and circadian rhythm are affected by ethanol during embryogenesis

The GO analysis of cluster 3 (Supplementary Table S2) indicated the presence of proteins related to circadian rhythm and the folic acid, retinoid, and neurotransmitter metabolic processes. It should be noted that RA synthesis is induced upon the loss of synaptic activity and decreased dendritic calcium levels (Chen et al., 2012). In the prenatal ethanol exposure network (PE-network; Fig. 2A), we found that retinoid metabolic processes and Ca2+ ion homeostasis are underexpressed (Table 2). This is interesting because both calcium ion homeostasis and RA metabolism genes were underexpressed, showing that the induction of RA to overcome synaptic loss might not be possible in ethanol-exposed fetuses. Moreover, RARs have also been found to be essential for improved learning and memory in the adult brain and have even alleviated memory deficits in a transgenic mice model for Alzheimer's disease (Nomoto et al., 2012). Cognitive and learning abilities have already been found to be affected in young adults displaying FAS (O'Leary, 2004), and the impairment of RA metabolism could be an explanation that has not yet been examined. Moreover, RARα is abundantly found in the cortex and hippocampus (Nomoto et al., 2012). Our data indicated that RARα is downregulated in the EGEP-Network (Chen et al., 2012) (Supplementary Table S1), showing that the changes in synaptic plasticity and learning behaviors that depend on RA occur specifically during early development.

To corroborate the idea that ethanol affects RA, we observed that ALDH1A2 (RALDH2) gene, which codes for an aldehyde dehydrogenase and is responsible for the synthesis of RA from retinal (Strate et al., 2009), was found to be underexpressed in both the PE-Network and the PSE-Network (Fig. 4). This is interesting because ALDH1B1, another aldehyde dehydrogenase, is downregulated in ethanol-exposed embryos during nerulation (Zhou et al., 2011), a finding corroborated in our systems chemo-biology analysis, as ALDH1B1 was downregulated in both the EGEP-Network and the LGEP-Network (Fig. 4).

Folic acid (FA) metabolism was also associated with Cluster 3 (Supplementary Table S2). It is already known that ethanol affects folic acid absorption in guinea pigs (Hewitt et al., 2011) and that FA has multiple roles in neural tissue (Table 1). Remarkably, FA is able to differentiate neurospheres into multiple neural cell types and promote synaptic connections in Pax3-deficient mice (Ichi et al., 2012).

In the transcriptomic datasets analyzed, only the dihydrofolate reductase (DHFR) gene, which codes for a key enzyme in folate metabolism (Cluster 3: Supplementary Table S2), was found to be underexpressed in fetuses exposed to ethanol in the final phase of development (LGEP-Network; Fig. 2D). One study shows that FA deficiency decreases neural progenitor cell proliferation in the mouse forebrain during late gestation (Craciunescu et al., 2004). Therefore, ethanol may also affect neuronal proliferation through FA metabolism, mainly through DHFR deregulation.

Another important process found within Cluster 3 is circadian rhythm (Supplementary Table S2). Ethanol consumption and abuse affect are known to affect sleep cycles and melatonin secretion (Brager et al., 2010; Roehrs and Roth, 2001). Interestingly, our data analyses (PE-Network; Fig. 2A) indicate that calcium ion homeostasis is downregulated (Table 2). Circadian rhythm is controlled by melatonin secretion, which consequently has a central role in inducing neurodevelopment during embryogenesis by inducing calcium ion signaling (de Faria Poloni et al., 2011). In pregnant women, the abuse of ethanol could skew proper melatonin secretion and calcium ion signaling and subsequently change sleep induction and neurodevelopment. We found RA, thiamine (TM), α-tocopherol (α-TC) and phytonadione (phylloquinone; PQN) in cluster 3.

Ethanol negatively affects vitamin D metabolism and leads to its degradation

Another interesting cluster (Cluster 5) presented several GOs related to neurodevelopment and RA and VD metabolism (Supplementary Table S2). Among all of the genes/proteins belonging to this cluster, CYP2R1 (Figs. 2A and 2C) was found to be underexpressed in both murine fetuses exposed to ethanol (PE-Network; Fig. 2A) and also in murine adults that were exposed to ethanol during development (EGEP-Network; Fig. 2C).

CYP2R1 is a VD hydroxylase that converts vitamin D3 into the first active ligand (25-hydroxy vitamin D3—25OHD3) for the vitamin D receptor (VDR) (Eyles et al., 2013). VDR forms heterodimers with retinoid X receptors (RXR) to initiate transcription during the differentiation of different tissues (Eyles et al., 2013). It has been reported that VD deficiency is correlated with decreased intracellular calcium levels in rat cortex (Baksi and Hughes, 1982), which infers that ethanol affects calcium ion homeostasis in the PE-Network and is critical for neurodevelopment. VDr expression is also observed in differentiating fields in rodent brains and in proliferating cells in the lateral ventricle (Eyles et al., 2013).

Interestingly, VD deficiency is associated with low induction of neurogenesis and the loss of apoptosis, generating larger brains due to abnormal proliferation (Eyles et al., 2013). This statement corroborates our GO results that indicate an increase in the negative regulation of apoptosis in EGEP-Network (Table 2). Thus, by affecting VD metabolism, VDR-dependent transcription could also be affected by ethanol, not only through target-protein recruitment but also through the formation of heterodimers with RXR, culminating in the loss of the signaling pathways associated with vitamin A.

Another gene directly related to VD metabolism is CYP27B1. The gene product converts 25-OHD3 into 24,25-hydroxy vitamin D3 and 1,25-hydroxy vitamin D3 (Eyles et al., 2013). Cyp27b1 was found to be underexpressed in the murine pups exposed to ethanol (PSE-Network; Fig. 2B).

Another important gene found among the overexpressed genes in the LGEP-Network (Fig. 2D) is CDK11B (CDK11p58) (Supplementary Table S1). Remarkably, CDK11p58 promotes the inhibition of VDR through ubiquitin-proteasome-mediated degradation (Chi et al., 2009), indicating that ethanol could interfere with VD action by promoting the degradation of VDR. Consistent with that hypothesis, protein ubiquitination was present in Cluster 5, proteolysis involved in cellular protein catabolic process was present in Cluster 15 (Supplementary Table S2), and the proteolytic genes were among those overexpressed in the transcriptomic sets of the PE- and PSE-Networks.

Interplay between ethanol exposure, vitamin deficiency, and neuroinflammation

A major result of this systems chemo-biology analysis is that ethanol has been directly connected to the positive induction of inflammation (Clusters 3, 5, 6, 8, 10–11, and 14; Supplementary Table S2), especially in the overexpression of genes in murine adult individuals exposed to ethanol during embryogenesis (EGEP-Network; Fig. 2C; Supplementary Table S4). This result indicates that the induction of inflammation occurs during early gestation and extends through development into adult. Consistent with these data, VDR deletion was observed to reduce the activity of IκBα protein, a potent inhibitor of the inflammatory-associated transcriptional factor NFκB, (Wu et al., 2010). It is important to note that inflammatory insults during pregnancy have already been correlated with Alzheimer's and Parkinson's diseases (Miller and O'Callaghan, 2008). Indeed, the activation of NFκB in adults leads to amyloid-β accumulation due to the synthesis of leukotriene D4 in cortical neurons (Wang et al., 2013).

In addition, IκBα promotes neurodifferentiation by blocking self-renewal and by indirectly reducing the levels of repressor element silencing transcription factor (REST), an inhibitor of neurogenesis (Khoshnan and Patterson, 2012).

Supporting the finding that vitamin metabolism could be correlated with neuroprotection against inflammation promoted by IκBα, proteins associated with the process of fat-soluble vitamin metabolism are underexpressed in the EGEP-Network (Supplementary Table S4).

Corroborating the hypothesis that ethanol can promote neuroinflammation through VDR downregulation, IκBα was underexpressed in the overlaps between the PE- and PSE-Networks (Fig. 4; Table 3). VD and AT, as well as RA, are fat-soluble vitamins and may protect neurons against inflammation.

Vitamin deficiency driven by ethanol exposure leads to altered glutamate uptake

Glutamate has a major role as an excitatory neurotransmitter in the mammalian brain and is responsible for multiple aspects of neural activity, such as cognition and memory, which are both affected by FAS and FASD (O'Leary, 2004; Ruediger and Bolz, 2007). However, the overstimulation of glutamate can be responsible for brain injury and neuron apoptosis (Lu et al., 2013). The data gathered in this study showed that fetuses exposed to ethanol (EGEP-Network; Fig. 2C) early in development display an overstimulation of glutamine metabolism, which is a normal component controlling of glutamate levels in the central nervous system through the glutamine-glutamate cycle (Supplementary Table S4).

Glutamate also activates G-protein-coupled metabotropic receptors that can exert their effects through the cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP) pathway (Ruediger and Bolz, 2007), which is related to neurodevelopment and melatonin regulation (de Faria Poloni et al., 2011). Interestingly, the cAMP pathway is downregulated (Table 2) in fetuses exposed to ethanol during development (PE-Network; Fig. 2A) and also in pups postnatally exposed to ethanol (PSE-Networks; Fig. 2B). This indicates that ethanol exposure in the brain might have a negative effect on the cAMP pathway, thereby resulting in defects in G-protein-coupled receptor activity. To corroborate with our hypothesis, it was already observed that glutamate levels are abnormally high during a mice model of FAS (Karl et al., 1995).

Ascorbic acid (AC) is released into the extracellular space to protect neurons exposed to cytotoxic concentrations of glutamate (Lane and Lawen, 2013). AC is a water-soluble vitamin, and water-soluble vitamin metabolic processes were among the GOs observed in cluster 12 (Supplementary Table S2).

The results from fetuses exposed to ethanol during the late phase of development (LGEP-Network; Fig. 2D) indicated that the gene coding for nicotinamide-nucleotide adenylyltransferase (NMNAT2), an enzyme predominantly expressed in the brain and related to NADP biosynthesis, is underexpressed. This result is interesting, as it seems that nicotinamide [niacin (NC)] deficiency is already correlated to neuronal damage (Table 1). It should be pointed the NMNAT2 was among the overexpressed genes in the EGEP-Network, indicating that the ethanol-induced deficiency in NC may be more aggressive in later stages of development.

Conclusion

In summary, in our chemo-systems biology analysis, we prospected interactomes and combined the topological, GO and transcriptomic analyses of four ethanol-exposed groups of mice at different ages. The results gathered from this work helped to elucidate FAS development and its interaction with vitamin metabolism (Fig. 5). Ethanol appears to impair biological processes such as (i) the circadian cycle; (ii) calcium ion homeostasis; (iii) the glutamine pathway; (iv) the cAMP pathway; (v) inflammation; (vi) neuron differentiation; and (vii) synapse formation and plasticity. These processes appear to be closely related to vitamin metabolism, particularly for RA, VD, NC, and FA. Because ethanol is already correlated with vitamin deficiency, and vitamins are crucial for brain development, understanding the relationship between ethanol and vitamins appears to be essential for preventing the development of FAS and related outcomes. The targets selected in this work by data crossing and HB analysis among the different ethanol-exposed mice also generated important targets to be reviewed for FAS prevention and treatment because none of them had previously been correlated with FAS or FASD. Tubulin and tubulin-associated proteins, synapse plasticity proteins, and the proteins related to neurodifferentiation are of particular interest.

FIG. 5.

Summary of the main findings of how ethanol may affect neurodevelopment in a FAS condition. The blue rectangles indicate a bioprocess in which the associated genes are found underegulated in the transcriptomic data and the red rectangles indicate those which are overexpressed. The black rectangles indicate the network where the bioprocess was observed. (A) summary of the action of ethanol in Ca2+ homeostasis and RA metabolism, resulting in the loss of synaptic potential and neurodifferentiation. (B) Summary of the observed negative effects of ethanol in folate and niacin metabolism. It also shows that ethanol leads to increased glutamate cytotoxicity. (C) action of ethanol in vitamin D metabolism. In this scenario, ethanol may provoke vitamin D receptor (VDR) degradation via proteasome. The model also indicates that vitamin D metabolism is negatively regulated by ethanol abuse, leading to loss of neurodifferentiation, and culminating in a negative regulation of both vitamin D and vitamin A signaling pathways.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Msc. Kendi Nishino Miyamoto for helping with the statistical analyzes. This work was supported by research grants from the Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPq; grant no. 301149/2012-7), the Programa Institutos Nacionais de Ciência e Tecnologia (INCT de Processos Redox em Biomedicina-REDOXOMA; grant no. 573530/2008-4), Fundação de Amparo a Pesquisa do Rio Grande do Sul FAPERGS (PRONEM grant no. 11/2072-2), and the Programa Binacional de Terapia Celular–Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior (PROBITEC-CAPES; grant no. 004/12).

Author Disclosure Statement

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

References

- Ahn EY, Dekelver RC, Lo MC, et al. (2011). SON controls cell-cycle progression by coordinated regulation of RNA splicing. Mol Cell 42, 185–198 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahn J, Albanes D, Berndt SI, et al. (2009). Vitamin D-related genes, serum vitamin D concentrations and prostate cancer risk. Carcinogenesis 30, 769–776 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bader GD, and Hogue CW. (2003). An automated method for finding molecular complexes in large protein interaction networks. BMC Bioinform 4, 2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baksi SN, and Hughes MJ. (1982). Chronic vitamin D deficiency in the weanling rat alters catecholamine metabolism in the cortex. Brain Res 242, 387–390 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beaudin AE, Abarinov EV, Noden DM, et al. (2011). Shmt1 and de novo thymidylate biosynthesis underlie folate-responsive neural tube defects in mice. Am J Clin Nutrition 93, 789–798 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benjamini Y, and Hochberg Y. (1995). Controlling the false discovery rate—A practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J Roy Stat Soc B Met 57, 289–300 [Google Scholar]

- Binns D, Dimmer E, Huntley R, Barrell D, O'donovan C, and Apweiler R. (2009). QuickGO: A web-based tool for Gene Ontology searching. Bioinformatics 25, 3045–3046 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bjorneboe GE, Bjorneboe A, Hagen BF, Morland J, and Drevon CA. (1987). Reduced hepatic alpha-tocopherol content after long-term administration of ethanol to rats. Biochim Biophys Acta 918, 236–241 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brager AJ, Ruby CL, Prosser RA, and Glass JD. (2010). Chronic ethanol disrupts circadian photic entrainment and daily locomotor activity in the mouse. Alcoholism, Clin Exper Res 34, 1266–1273 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brodsky G, Barnes T, Bleskan J, Becker L, Cox M, and Patterson D. (1997). The human GARS-AIRS-GART gene encodes two proteins which are differentially expressed during human brain development and temporally overexpressed in cerebellum of individuals with Down syndrome. Human Mol Genet 6, 2043–2050 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carbon S, Ireland A, Mungall CJ, et al. (2009). AmiGO: Online access to ontology and annotation data. Bioinformatics 25, 288–289 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caspi R, Altman T, Dale JM, et al. (2010). The MetaCyc database of metabolic pathways and enzymes and the BioCyc collection of pathway/genome databases. Nucleic Acids Res 38, D473–479 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castro MA, Filho JL, Dalmolin RJ, et al. (2009). ViaComplex: Software for landscape analysis of gene expression networks in genomic context. Bioinformatics 25, 1468–1469 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chandra N, and Padiadpu J. (2013). Network approaches to drug discovery. Expert Opin Drug Disc 8, 7–20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen L, Lau AG, and Sarti F. (2014). Synaptic retinoic acid signaling and homeostatic synaptic plasticity. Neuropharmacology 78, 3–12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chi Y, Hong Y, Zong H, et al. (2009). CDK11p58 represses vitamin D receptor-mediated transcriptional activation through promoting its ubiquitin-proteasome degradation. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 386, 493–498 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craciunescu CN, Brown EC, Mar MH, Albright CD, Nadeau MR, and Zeisel SH. (2004). Folic acid deficiency during late gestation decreases progenitor cell proliferation and increases apoptosis in fetal mouse brain. J Nutrition 134, 162–166 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Csermely P, Korcsmaros T, Kiss HJ, London G, and Nussinov R. (2013). Structure and dynamics of molecular networks: A novel paradigm of drug discovery: A comprehensive review. Pharmacol Therapeut 138, 333–408 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Faria Poloni J, Feltes BC, and Bonatto D. (2011). Melatonin as a central molecule connecting neural development and calcium signaling. Funct Integrative Genom 11, 383–388 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De La Monte SM, and Kril JJ. (2014). Human alcohol-related neuropathology. Acta Neuropathol 127, 71–90 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eyles DW, Burne TH, and Mcgrath JJ. (2013). Vitamin D, effects on brain development, adult brain function and the links between low levels of vitamin D and neuropsychiatric disease. Frontiers Neuroendocrinol 34, 47–64 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feltes BC, Poloni Jde F, Notari DL, and Bonatto D. (2013). Toxicological effects of the different substances in tobacco smoke on human embryonic development by a systems chemo-biology approach. PloS One 8, e61743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Genetta T, Lee BH, and Sola A. (2007). Low doses of ethanol and hypoxia administered together act synergistically to promote the death of cortical neurons. J Neurosci Res 85, 131–138 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goez HR, Scott O, and Hasal S. (2011). Fetal exposure to alcohol, developmental brain anomaly, and vitamin A deficiency: A case report. J Child Neurol 26, 231–234 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hewitt AJ, Knuff AL, Jefkins MJ, Collier CP, Reynolds JN, and Brien JF. (2011). Chronic ethanol exposure and folic acid supplementation: Fetal growth and folate status in the maternal and fetal guinea pig. Reprod Toxicol 31, 500–506 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ichi S, Nakazaki H, Boshnjaku V, et al. (2012). Fetal neural tube stem cells from Pax3 mutant mice proliferate, differentiate, and form synaptic connections when stimulated with folic acid. Stem Cells Develop 21, 321–330 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaurena MB, Carri NG, Battiato NL, and Rovasio RA. (2011). Trophic and proliferative perturbations of in vivo/in vitro cephalic neural crest cells after ethanol exposure are prevented by neurotrophin 3. Neurotoxicol Teratol 33, 422–430 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen LJ, Kuhn M, Stark M, et al. (2009). STRING 8—A global view on proteins and their functional interactions in 630 organisms. Nucleic Acids Res 37, D412–416 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jupe S, Akkerman JW, Soranzo N, and Ouwehand WH. (2012). Reactome—A curated knowledgebase of biological pathways: megakaryocytes and platelets. J Thrombosis Haemostasis 10, 2399–2402 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanehisa M, and Goto S. (2000). KEGG: Kyoto encyclopedia of genes and genomes. Nucleic Acids Res 28, 27–30 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karl PI, Kwun R, Slonim A, and Fisher SE. (1995). Ethanol elevates fetal serum glutamate levels in the rat. Alcohol Clin Exper Res 19, 177–181 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kashyap V, and Gudas LJ. (2010). Epigenetic regulatory mechanisms distinguish retinoic acid-mediated transcriptional responses in stem cells and fibroblasts. J Biol Chem 285, 14534–14548 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khoshnan A, and Patterson PH. (2012). Elevated IKKalpha accelerates the differentiation of human neuronal progenitor cells and induces MeCP2-dependent BDNF expression. PloS One 7, e41794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuhn M, Szklarczyk D, Franceschini A, Von Mering C, Jensen LJ, and Bork P. (2012). STITCH 3: Zooming in on protein–chemical interactions. Nucleic Acids Res 40, D876–880 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurimoto K, Kuwasako K, Sandercock AM, et al. (2009). AU-rich RNA-binding induces changes in the quaternary structure of AUH. Proteins 75, 360–372 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lane DJ, and Lawen A. (2013). The glutamate aspartate transporter (GLAST) mediates L-glutamate-stimulated ascorbate-release via swelling-activated anion channels in cultured neonatal rodent astrocytes. Cell Biochem Biophys 65, 107–119 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim CS, and Alkon DL. (2012). Protein kinase C stimulates HuD-mediated mRNA stability and protein expression of neurotrophic factors and enhances dendritic maturation of hippocampal neurons in culture. Hippocampus 22, 2303–2319 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez-Fanarraga M, Carranza G, Bellido J, Kortazar D, Villegas JC, and Zabala JC. (2007). Tubulin cofactor B plays a role in the neuronal growth cone. J Neurochem 100, 1680–1687 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu XC, Dave JR, Chen Z, Cao Y, Liao Z, and Tortella FC. (2013). Nefiracetam attenuates post-ischemic nonconvulsive seizures in rats and protects neuronal cell death induced by veratridine and glutamate. Life Sci 92, 1055–1063 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maere S, Heymans K, and Kuiper M. (2005). BiNGO: A Cytoscape plugin to assess overrepresentation of gene ontology categories in biological networks. Bioinformatics 21, 3448–3449 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maffi SK, Rathinam ML, Cherian PP, et al. (2008). Glutathione content as a potential mediator of the vulnerability of cultured fetal cortical neurons to ethanol-induced apoptosis. J Neurosci Res 86, 1064–1076 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller DB, and O'Callaghan JP. (2008). Do early-life insults contribute to the late-life development of Parkinson and Alzheimer diseases? Metab Clin Exper 57, S44–49 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newman MEJ. (2005). A measure of betweenness centrality based on random walks. Soc Networks 27, 39–54 [Google Scholar]

- Noelker C, Schwake M, Balzer-Geldsetzer M, et al. (2012). Differentially expressed gene profile in the 6-hydroxy-dopamine-induced cell culture model of Parkinson's disease. Neurosci Lett 507, 10–15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nomoto M, Takeda Y, Uchida S, et al. (2012). Dysfunction of the RAR/RXR signaling pathway in the forebrain impairs hippocampal memory and synaptic plasticity. Mol Brain 5, 8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Leary CM. (2004). Fetal alcohol syndrome: Diagnosis, epidemiology, and developmental outcomes. J Paed Child Health 40, 2–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oehlmann VD, Berger S, Sterner C, and Korsching SI. (2004). Zebrafish beta tubulin 1 expression is limited to the nervous system throughout development, and in the adult brain is restricted to a subset of proliferative regions. Gene Expression Patt 4, 191–198 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park H, Yamada K, Kojo A, Sato S, Onozuka M, and Yamamoto T. (2009). Drebrin (developmentally regulated brain protein) is associated with axo-somatic synapses and neuronal gap junctions in rat mesencephalic trigeminal nucleus. Neurosci Lett 461, 95–99 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qin L, and Crews FT. (2013). Focal thalamic degeneration from ethanol and thiamine deficiency is associated with neuroimmune gene induction, microglial activation, and lack of monocarboxylic acid transporters. Alcohol Clin Exper Res 38, 357–371 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rebhan M, Chalifa-Caspi V, Prilusky J, and Lancet D. (1997). GeneCards: Integrating information about genes, proteins and diseases. Trends Genetics 13, 163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roehrs T, and Roth T. (2001). Sleep, sleepiness, sleep disorders and alcohol use and abuse. Sleep Med Rev 5, 287–297 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosado JO, Henriques JP, and Bonatto D. (2011). A systems pharmacology analysis of major chemotherapy combination regimens used in gastric cancer treatment: Predicting potential new protein targets and drugs. Curr Cancer Drug Targets 11, 849–869 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruediger T, and Bolz J. (2007). Neurotransmitters and the development of neuronal circuits. Adv Exper Med Biol 621, 104–115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russo E, Citraro R, Constanti A, and De Sarro G. (2012). The mTOR signaling pathway in the brain: Focus on epilepsy and epileptogenesis. Mol Neurobiol 46, 662–681 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Safran M, Dalah I, Alexander J, et al. (2010). GeneCards Version 3: The human gene integrator. Database J Biol Databases Curation 2010, baq020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scardoni G, Petterlini M, and Laudanna C. (2009). Analyzing biological network parameters with CentiScaPe. Bioinformatics 25, 2857–2859 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider HC, and Klabunde T. (2013). Understanding drugs and diseases by systems biology? Bioorg Med Chem Lett 23, 1168–1176 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shannon P, Markiel A, Ozier O, et al. (2003). Cytoscape: A software environment for integrated models of biomolecular interaction networks. Genome Res 13, 2498–2504 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singleton CK, and Martin PR. (2001). Molecular mechanisms of thiamine utilization. Curr Mol Med 1, 197–207 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snel B, Lehmann G, Bork P, and Huynen MA. (2000). STRING: A web-server to retrieve and display the repeatedly occurring neighbourhood of a gene. Nucleic Acids Res 28, 3442–3444 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]