Abstract

Modulation of autotaxin (ATX), the lysophospholipase D enzyme that produces lysophosphatidic acid (LPA), with small-molecule inhibitors is a promising strategy for blocking the ATX/LPA signaling axis. While discovery campaigns have been successful in identifying ATX inhibitors, many of the reported inhibitors target the catalytic cleft of ATX. A recent study provided evidence for an additional inhibitory surface in the hydrophobic binding pocket of ATX, confirming prior studies that relied on enzyme kinetics and differential inhibition of substrates varying in size. Multiple hits from a previous high-throughput screening (HTS) for ATX inhibitors were obtained with aromatic sulfonamide derivatives interacting with the hydrophobic pocket. Here we describe the development of a ligand-based strategy and its application in a virtual screening, which yielded novel high-potency inhibitors that target the hydrophobic pocket of ATX. Characterization of the structure-activity relationship of these new inhibitors forms the foundation of a new pharmacophore model of the hydrophobic pocket of ATX.

Keywords: Autotaxin, Virtual Screening, Inhibitors, Enzymology

Introduction

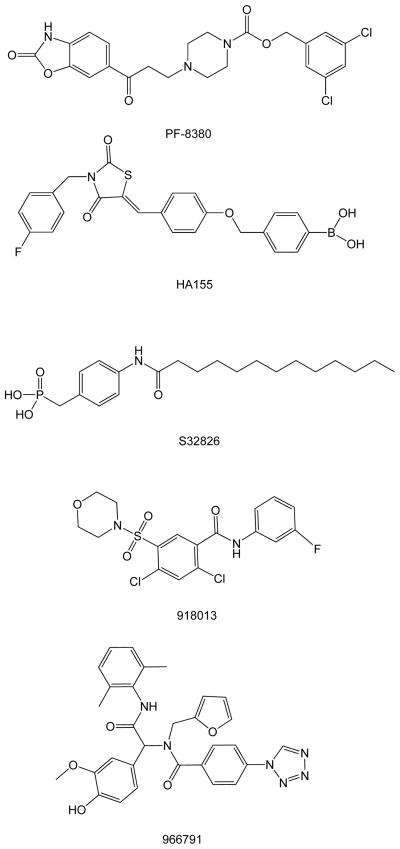

Autotaxin (ATX) inhibitors represent an emerging class of drug candidates with therapeutic potential in the treatment of disease conditions that include cancer, cardiovascular disease, chronic inflammation, and neuropathic pain [1–5]. Numerous medicinal chemistry efforts have been successful in identifying ATX inhibitors; among these are HA155, PF-8380, S32826, and the benzyl- and naphthyl-methylphosphonic acid compounds RG-22 and RG-30b (Fig. 1) [6–11].

Figure 1.

Chemical structures of known ATX inhibitors.

Despite these efforts, scant success has been reported in the preclinical development of therapeutic agents that target ATX. One reason for the slow progress in drug development is that many of the small molecules identified to date are lipid-like, which leads to unsuitable partition coefficients for drugs (log P >5) that limit their therapeutic utility. Mechanistically, many of the ATX inhibitors reported to date have targeted the catalytic site of ATX [12], and the binding site of those that may not work by blocking the catalytic site has not been elucidated in detail. Therefore, lipid-like inhibitors mimicking ATX’s natural substrate lysophosphatidylcholine (LPC) or its product lysophosphatidic acid (LPA), or having a molecular mass larger than 500 Daltons are all causes for failing Lipinski’s rule of five that defines the properties for an orally bioavailable active drug [13]. Recent crystal structures of ATX with the active-site inhibitor HA155 cocrystallized have provided insight into potentially inhibitory surfaces of ATX, which should accelerate the rational discovery of the next generation of small-molecule drug-like ATX inhibitors [14–16].

Recently we reported the characterization of an ATX inhibitor, 918013 (Fig. 1), that exerts its blocking action via interactions with the hydrophobic pocket of ATX, an area outside the catalytic site [17]. This competitive inhibitor demonstrated the same pharmacological and biological effects on ATX activity as compounds that block the catalytic site. The anti-invasive and antimetastatic effect of 918013 suggested the potential utility of ATX inhibitors that interact only with the hydrophobic pocket as new tools for the elucidation of the role of ATX and LPA in vivo. Compound 918013 was only one of multiple hits identified in HTS of ATX inhibitors containing an aromatic sulfonamide group.

Here we report the application of a focused virtual and experimental screening approach using the University of Cincinnati Drug Discovery Center (UC-DDC) database of approximately 340,000 searchable chemical structures. In this virtual screening, we have initially identified 230 in silico hits, of which 38 inhibited ATX hydrolysis of the LPC-like fluorogenic substrate-3 (FS-3) by >50% at 10 μM, yielding an experimentally validated hit rate of 17%. Examination of the structure-activity relationship (SAR) of this series of compounds showed that small changes to the structure of these compounds at four positions can result in dramatic changes in pharmacological properties. Using this SAR examination of the aromatic sulfonamide scaffold, we developed a new and spatially more constrained pharmacophore design and delineated the unique interactions between the aromatic sulfonamide group with residues lining the hydrophobic pocket of ATX. This search strategy identified a new ATX inhibitor, compound 403070, with an inhibition constant (Ki) of 8.4 nM and drug-like properties. This inhibitor provides an excellent starting point for optimization and in vivo testing and also validates a new pharmacophore model of the hydrophobic pocket.

Results

Identification of Novel ATX Inhibitors by Virtual Screening

We recently implemented a HTS assay to identify small-molecule inhibitors of ATX. In screening 10,000 compounds from a diversity set of the UC-DDC database, we identified 196 potential ATX inhibitors that caused 50% inhibition of the hydrolysis of FS-3 when applied at 10 μM. Six of these compounds were found to have close similarity, all sharing an aromatic sulfonamide motif that includes 918013. In order to identify new ATX inhibitors, a virtual screening was performed, applying a series of two-dimensional similarity searches. Molecular fingerprints based on molecular access system keys were calculated for the UC-DDC library of >340,000 compounds. Three sequential rounds of database screenings were performed using three different templates as queries: 918013 (5,997 hits), 934313 (2,360 hits), and 897131 (1,754 hits). A Tanimoto threshold of >80 was applied as cutoff for each screening [18]. We applied an intersection inequality approach to combine the search results, maximizing the chances of identifying compounds with similar degrees of ATX inhibition. Cross matching the database results using the three templates yielded 230 overlapping virtual hits.

Experimental Validation of Virtual Hit ATX Inhibitors

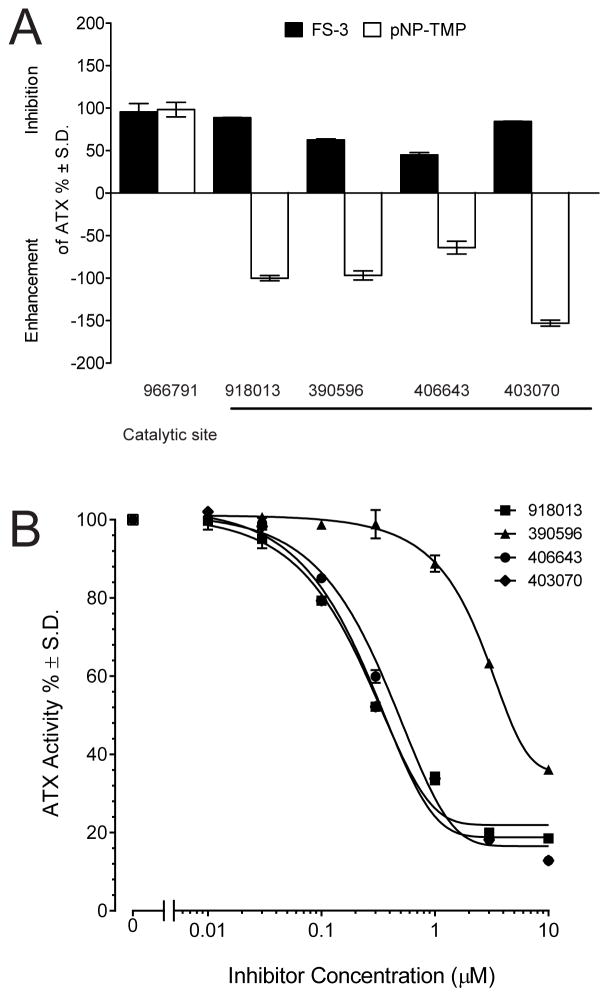

Inhibition assays of ATX-mediated hydrolysis of FS-3 were performed with the selected 230 compounds applied at a fixed concentration of 10 μM. A compound was defined as an experimentally validated hit if it caused >50% inhibition of the hydrolysis of the model lysophospholipase D substrate FS-3. Thirty-eight inhibitory compounds from the initial screening met this criterion (17% hit rate, Fig. S2). ATX, also known as nucleotide pyrophosphate phosphatase 2 (NPP2), belongs to a family of enzymes that possess phosphodiesterase activity against the nucleotide substrate p-nitrophenyl thymidine 5′-monophosphate (pNP-TMP). The size of the hit set was further decreased by applying a series of five experimental filters that included: 1) substrate selectivity for the lysophospholipase substrate FS-3 versus the nucleotide-like substrate pNP-TMP (Fig. 2A); 2) determination of the dose–response relationship for inhibition of lysophospholipase D enzyme activity (Table 1); 3) counter-screening to eliminate molecular aggregates in the presence of 0.01% Triton X-100 (Fig. 2B); 4) inhibition of the hydrolysis of 3-acyl-7-dimethylaminonaphthyl-1-LPC (ADMAN-LPC, Table 1); and 5) cleavage of different molecular species of LPC (Table 2). A compound was designated as desirable if it had IC50 < 1 μM and inhibited FS-3, LPC, and ADMAN-LPC hydrolysis. Application of this stringent set of criteria was satisfied by only three compounds: 390596, 406643, and 403070 (Fig. 3), with respective IC50 values of 141.4, 58.14, and 21.49 nM and Ki values ranging from 8–440 nM against the FS-3 substrate. In addition, we found 12 other compounds that had potency with IC50 values < 3 μM (see Table S1).

Figure 2.

Identification and characterization of ATX inhibitors by HTS. Panel A: Comparison of substrate selectivity against FS-3 (filled bars) and pNP-TMP (open bars) for the three inhibitors applied at 10 μM. Compound 966791 is a representative example of a catalytic site inhibitor that blocks the hydrolysis of both FS-3 and pNP-TMP and is included to validate the assay. Bars in the upward direction represent inhibition of the hydrolysis of a substrate, whereas downward deflection indicates enhancement. The inhibition was normalized to the cleavage of the substrate in the absence of the inhibitors designated as 100%. Panel B: Dose-response curve of most potent aromatic sulfonamide hits from virtual screening using the FS-3 substrate in Triton X-100 counter-screening. Data points are the mean of triplicate determinations.

Table 1.

Summary of the in vitro pharmacological characterization of selected ATX inhibitors

| FS-3 | ADMAN-LPC | Invasion Assay | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Compound | % Inhibition at 10 μMA | IC50(nM)B | Mechanism of InhibitionC | Ki (nM)D | % inhibition at 10 μME | % inhibition at 10 μMF |

| 918013 | 89 ± 0.3 | 32 ± 5.8 | Competitive | 14.6 ± 1.5 | 85 ± 11.0 | 67 ± 14.4 |

| 390596 | 63 ± 1.0 | 141 ± 9.4 | Competitive | 435 ± 6.5 | 33 ± 6.2 | 48 ± 13.0 |

| 406643 | 45 ± 2.9 | 58 ± 3.7 | Competitive | 413 ± 27 | 34 ± 18.0 | 13 ± 25.2 |

| 403070 | 84 ± 0.2 | 21 ± 3.7 | Competitive | 8.4 ± 1.1 | 100 ± 0.0 | 82 ± 3.5 |

Hydrolysis of 1 μM FS-3 by 10 nM ATX was measured after 4 h incubation in the presence and absence of 10 μM inhibitor and presented as mean percent inhibition of ATX ± SD (n=3).

FS-3 hydrolysis was utilized to determine inhibitor potency in which 0.03–30 μM concentrations of inhibitors were assayed for effects on 10 nM ATX-mediated hydrolysis of 1 μM FS-3 after 4 h incubation. Percent ATX activity was plotted versus inhibitor concentration, and non-linear regression analysis was performed in GraphPad Prism version 5.0a to calculate mean IC50 ± SD (n=3).

Inhibitor mechanism of action was assessed via FS-3 hydrolysis in which FS-3 concentrations of 0.3–10 μM were incubated in the presence of 10 nM ATX with 0, 0.5× or 2× the previously-calculated IC50 concentrations for each inhibitor. Reaction rate data were then simultaneously fitted via non-linear regression in the Michaelis-Menten equations for competitive, non-competitive, uncompetitive or mixed-mode inhibition. Mechanism was selected based on the highest global correlation coefficient in conjunction with interpretation of the program’s calculated α value which reflects the change in affinity for enzyme to substrate upon inhibitor binding.

Ki was also calculated based on the selected Michaelis-Menten non-linear regression analysis of FS-3 hydrolysis reaction rate data and presented as mean Ki ± SD (n=3).

Hydrolysis of 30 μM ADMAN-LPC by 30 nM ATX was assessed after 4 h incubation and subsequent modified Bligh-Dyer extraction of lipids, which were then separated via TLC. Separated lipids were imaged under UV transillumination, and densitometry was conducted in ImageJ software for comparison of ADMAN-LPA versus ADMAN-LPC in order to calculate percent inhibition of ATX ± SD (n=3).

A2058 human melanoma cell invasion was measured utilizing the BD Biosciences BD BioCoat™ Matrigel-coated tumor invasion system. Cell invasion was measured after 16 h incubation in the presence of 0.3 nM ATX in conjunction with 1 μM LPC 18:1 ± 10 μM inhibitor and presented as mean percent cell invasion ± SD (n=3).

Table 2.

Inhibition of ATX-mediated Hydrolysis of LPCs

| % Inhibition (± SD) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Compound | LPC 14:0 | LPC 16:0 | LPC 18:0 | LPC 18:1 |

| 918013 | 41.0 ± 5.1 | 55.4 ± 1.7 | 43.6 ± 2.6 | 51.8 ± 2.4 |

| 390596 | 34.9 ± 0.6 | 54.6 ± 0.9 | 36.2 ± 2.3 | 43.9 ± 3.0 |

| 406643 | 25.0 ± 1.8 | 29.3 ± 2.9 | 10.4 ± 3.6 | 12.4 ± 2.1 |

| 403070 | 39.1 ± 2.7 | 42.9 ± 2.3 | 23.0 ± 3.6 | 24.5 ± 2.5 |

Data (relative fluorescence) were recorded as a mean value of the triplicates for each sample and reported as % inhibition of ATX-mediated LPC hydrolysis.

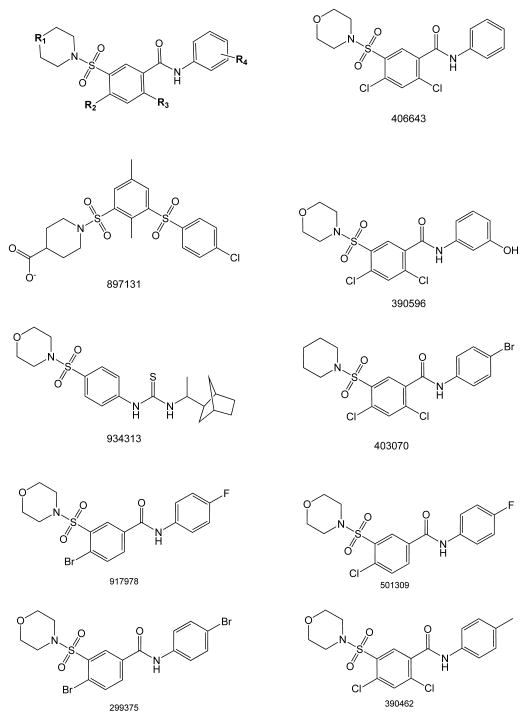

Figure 3.

The structural scaffold of the aromatic sulfonamide hits and selected chemical structures used in SAR studies from the virtual screening.

The Enzyme Kinetics of ATX Inhibition by Aromatic Sulfonamide Inhibitors

The aromatic sulfonamide ATX inhibitors were tested in the presence of increasing concentrations of FS-3. These experiments were performed using 0.5 and 2 times the IC50 of the inhibitors. The data were fitted via nonlinear regression into the Michaelis-Menten equations for competitive, noncompetitive, uncompetitive, and mixed-mode inhibition to determine the best model that could be fitted to the inhibition curves (see Methods, Table 1). These experiments showed that all three of our aromatic sulfonamide inhibitors inhibit ATX-mediated hydrolysis of FS-3 by a competitive mechanism of action. The Ki of 403070 is 8.43 nM, which is similar to that of our primary lead 918013 (14.64 nM, which was found from a HTS [17]).

Inhibition of the ATX Cleavage of Natural LPC Species by the Aromatic Sulfonamide Compounds

These three compounds were tested for the inhibition of the ATX-mediated hydrolysis of LPC 14:0, LPC 16:0, LPC 18:0, and LPC 18:1 (Table 2). The results of these experiments showed every compound inhibited the cleavage of all four molecular species of LPC with similar efficacy when applied at 10 μM. Thus, these hydrophobic pocket inhibitors do not show any preference to acyl chain of the substrate at this maximally effective concentration.

Structure-Activity Relationships for ATX inhibitors

After establishing the rank order of potency and common competitive mechanism of action of these aromatic sulfonamide compounds against lysophospholipid-like substrates, we examined their SAR (Fig. 3). The preliminary SAR analysis of this series of compounds suggested an overall trend in activity with replacement of the R1-4 groups (Fig. 3) in comparison to 918013. Replacement of the electronegative group in 918013 with a less bulky and more polar phenolic hydroxyl group in 390596 showed a five-fold decrease in potency (see Table 1 for IC50 values). The unsubstituted benzamide analog 406643 showed a 13-fold decrease in Ki value compared to 918013 (Table 1). Relocation of the fluorine to the para position and removal of the chlorine ortho to the carboxamide in compound 501309 reduced the potency of inhibition to 6.7 μM. Thus, changes in the R4 substituent affected efficacy (compare 918013, 390596, 406643, 403070, and 390462). In the non-chlorine-containing compounds 917978 and 299375, in which the two chlorines (R2 and R3) were replaced with a single bromine at R2 and the R4 substituents were either p-fluoro or p-bromo, efficacy was nearly identical. Thus, the R4 halogen group is of importance in determining the efficacy of the compound. By comparing the R4 substituent that was m-fluoro (918013) or p-bromo (403070) versus p-methyl (390462), m-hydroxyl (390596), or a hydrogen (406643), it appears that the size of the R4 substituent is more important for activity than its orientation. The effect of the orientation of the R4 group is best demonstrated by comparing compounds 918013 and 403070: the orientation of the R4 substituent is different, yet both have almost identical IC50 and Ki values (Table 1).

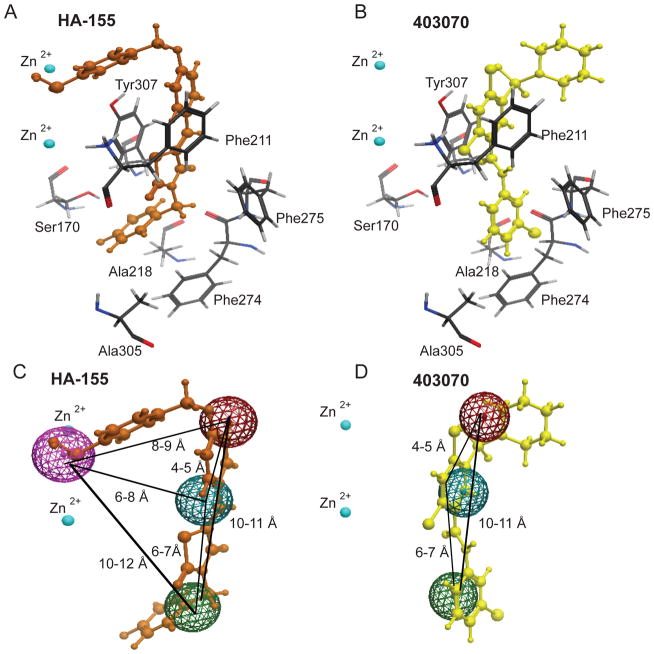

Molecular Docking of 403070 into the Hydrophobic Pocket of ATX

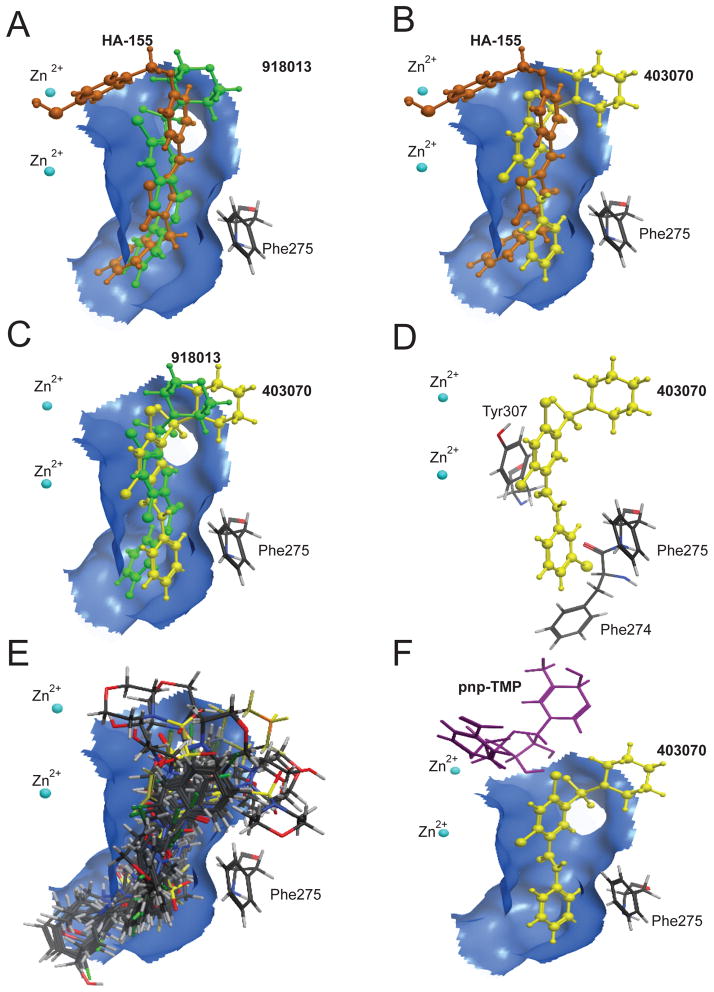

To further elucidate the mechanism of ATX inhibition by 403070, molecular docking studies were performed using the ATX crystal structure PDB 2XRG [15]. The previous kinetic studies suggested that 918013 is a competitive inhibitor of FS-3 without inhibiting pNP-TMP hydrolysis [17]. This pattern leads to the hypothesis that 403070, like 918013 and its analogs, occupies the hydrophobic pocket of ATX without interfering with the pNP-TMP placement at the catalytic site. Indeed, when 403070 was docked into this ATX structure (Fig. 4A), it occupied the ATX hydrophobic pocket without protruding into the catalytic cleft. On the basis of this model, 918013 and 403070, different only at the R1 and R4 positions (Fig. 3), docked in a similar space in the hydrophobic pocket and engaged in the same interactions with this inhibitory surface (Fig. 4B & C). These results are consistent with the competitive binding mechanism of 403070 against FS-3 and its lack of inhibition of pNP-TMP cleavage. Furthermore, the conservation of binding interactions between compounds 918013 and 403070 provides a plausible explanation for the similarity of their potency and efficacy (Table 1).

Figure 4.

Molecular modeling of the interaction of ATX with its inhibitors. Docked position of active hits for 918013 (green; panel A) and 403070 (yellow; panel B), shown overlayed on HA155 (orange) in the hydrophobic pocket (blue). Panel C: Overlay of 918013 (yellow) with 403070 (green) in the hydrophobic pocket (blue) shows the striking similarities between the positions and binding interactions of the two inhibitors. Panel D: Key π-π interactions between 403070 (yellow) and ATX involve hydrophobic residues Tyr307, Phe274, and Phe275. Panel E: Overlay of 38 virtual hit compounds individually docked to ATX show a very tight placement in the hydrophobic pocket. Panel F: Simultaneous docking of pNP-TMP and 403070 into the ATX structure shows no interference in binding. This type of docking simulation provides a plausible explanation for the lack of inhibition and enhancement of pNP-TMP hydrolysis by 403070.

Our docking simulations predict that the aromatic sulfonamide group makes aromatic interactions with the aromatic residues on the interface between the hydrophobic pocket and nucleotide-binding region of ATX (Fig. 4D). This ring portion of the aromatic sulfonamide series of compounds can engage residues Phe211, Tyr307, and Phe275 in a π-π charge-charge interaction. The R4 halogen on 918013 and 403070 occupies space deep in the hydrophobic pocket lined by residues Phe274, Ala305, Ser170, and Ala218. From these docked positions, the aromatic sulfonamide scaffold shows interactions that are analogous to that of LPC or the cocrystallized inhibitor HA155. Although some interacting residues are shared between our aromatic sulfonamide analogs and other previously identified inhibitors, the aromatic sulfonamide compounds do not protrude into the catalytic site. For example, catalytic site residues His360, His475, and His315 are too far away to interact with the aromatic sulfonamides in their docked position.

Because the Phe275Ala substituted ATX mutant retains FS-3 hydrolytic activity [17], we tested the inhibitory potency of 403070 on this mutant We hypothesized that 403070 would no longer inhibit this mutant due to the loss of its interaction with Phe275 in the hydrophobic pocket. Both compounds 918013 and 403070 showed a dramatic IC50 shift from the nanomolar range to >3 μM when the Phe275Ala ATX mutant was tested. These results provide important experimental proof for the interaction of aromatic sulfonamides with the inhibitory surface of the hydrophobic pocket in which Phe275 plays a crucial role.

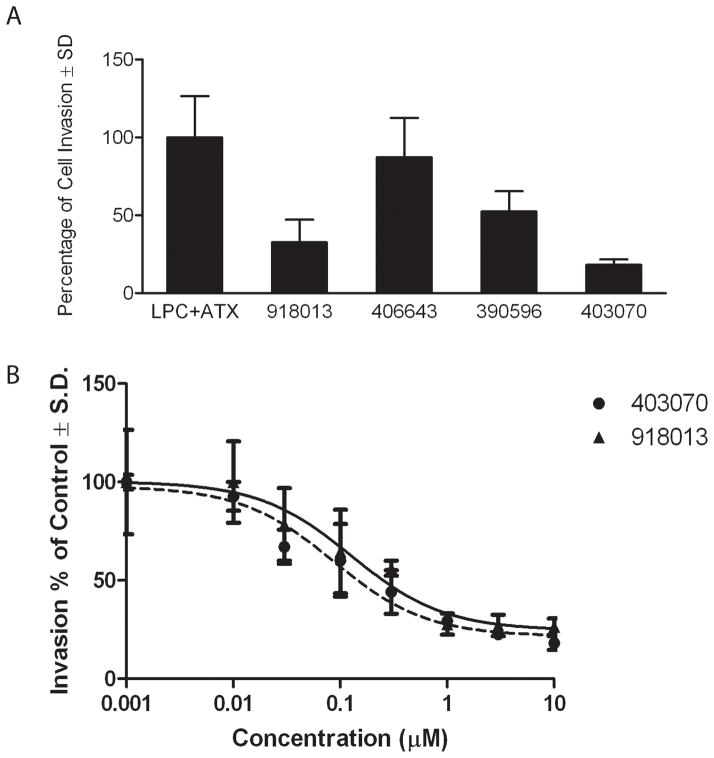

Effect of Inhibitors on Cell Invasion

To evaluate the effect of the new aromatic sulfonamide inhibitors in a cell-based system, we used ATX-dependent invasion of A2058 human melanoma cells. The compounds were initially screened at 10μM concentration. Dose response curves were then generated for compounds, which showed more than 50% inhibition of A2058 cell invasion. Both 918013 and 403070 caused a concentration-dependent decrease in A2058 invasion measured after a 16-h incubation with similar potencies (Fig. 6).

Figure 6.

Effect of ATX inhibitor hits on cancer cell invasion in vitro. A2058 human melanoma cells were applied to Matrigel-coated BD BioCoatTM chambers. ATX (0.1 nM) plus 1 μM of 18:1 LPC with or without 10 μM of the inhibitors was applied, and invasion was quantified 16 h later. For dose response curves, the inhibitors were applied at increasing concentrations ranging from 0.01 μM to 10 μM. The numbers shown are the mean of three experiments ± SD.

Discussion

Here we report the identification and pharmacological characterization of a novel series of ATX enzyme inhibitors with a common aromatic sulfonamide group at their core. This was accomplished by starting with an in silico search strategy, followed by biochemical and enzyme kinetics determinations and cell-based assays. This approach led to the identification of three novel ATX inhibitors with nanomolar inhibitory activity. The presented results further explore targeting the hydrophobic pocket of ATX as a means to competitively inhibit LPA production.

The recently solved ATX crystal structure revealed that there are multiple molecular surfaces at which small molecules may exert inhibitory action, including 1) the catalytic site, 2) the hydrophobic pocket, and 3) the hydrophobic channel [14,16,17]. Although previously described ATX inhibitors have evolved from lipid-like to nonlipid-like, the site of interaction for many of them has not been thoroughly described and experimentally characterized. More recently, we described two new nonlipid classes of compounds identified by a HTS campaign as ATX inhibitors. One class of compounds, designated as dual inhibitors (966791, Fig. 1), blocks the hydrolysis of both lysophospholipid-like and nucleotide-like substrates and binds near the catalytic site. In contrast to many published ATX inhibitors, another class, designated as single inhibitors, inhibits ATX via competition with lysophospholipid-like substrates but without inhibiting the phosphodiesterase-mediated hydrolysis of the nucleotide substrate pNP-TMP. Our present data on the aromatic sulfonamide series of compounds shows an increase in pNP-TMP hydrolytic activity, suggesting that these compounds not only fail to block the catalytic site shared by LPC and pNP-TMP but also, possibly via allosteric regulation of substrate binding and/or catalysis, enhance the phosphodiesterase activity. Our modeling studies are consistent with the finding that aromatic sulfonamide single inhibitors can bind to ATX simultaneously with pNP-TMP and enhance its hydrolysis (Fig. 4F). The comparable IC50 values of both hydrophobic-pocket and catalytic-site inhibitors strongly suggest that inhibition of the hydrophobic pocket of ATX is sufficient to disrupt the ATX/LPA signaling axis, as shown by our A2058 invasion assay. We have also demonstrated that the aromatic sulfonamide compounds inhibit ATX via a competitive mechanism of action against the LPC-like FS-3 substrate.

In an effort to identify additional hydrophobic inhibitors, 918013 was used as a starting point for SAR studies. We began by performing a two-dimensional similarity search of the UC-DDC database using an aromatic sulfonamide scaffold. The search resulted in 5,997 hits based on homology to three different templates. Although the availability of the ATX crystal structures provides the opportunity for structure-based design, we devised a virtual screening approach to filter and rank the aromatic sulfonamide derivatives for experimental validation. Docking of analogs of 918013 showed that these all interacted in the same region of ATX (Fig. 4E). To reduce the set of 5,997 hits, we applied an intersection inequality approach. This strategy reduced the set to 230 compounds that were screened for inhibition of FS-3 hydrolysis, leading to 16 compounds with an IC50 <3 μM. Compound 403070 was the most potent ATX inhibitor identified in this study, with a Ki value of 8.43 nM against FS-3. In addition, compounds 390596 and 406643 also met our filtered screening criteria.

We explored the SAR of this aromatic sulfonamide scaffold by asking whether small changes at four sites of this scaffold affect biological activity (Fig. 3). Although the selected inhibitors exhibit structural similarity with 918013, they also contain some unique features. From the SAR analysis, we determined the tolerance of the substituents at four positions and the effect of these substitutions on ATX activity. The molecular docking results are in agreement with the experimental SAR observations. The combined approach allowed identification of functional groups conserved between our most active compounds.

The ATX crystal structure allowed us to investigate the binding mode of the aromatic sulfonamide derivatives. Docking of 403070 into ATX results in an orientation similar to that of our lead compound, 918013 (Fig. 4C). The primary interaction of the aromatic sulfonamide compounds with ATX are with R3 and R4 aromatic rings, which form a π-π interaction with the aromatic amino acid residues lining the hydrophobic pocket (Figs. 4D & 5B). In contrast, changes to the R1 portion of ring one seem to extend from the hydrophobic pocket of ATX, which lends itself as a reliable site for additional modifications in lead optimization. Thus, the present results provide insight into the structural requirements for the activity of hydrophobic pocket inhibitors and will guide the design of further derivatives.

Figure 5.

ATX hydrophobic pocket residues in complex with HA155 (orange; panel A) and 403070 (yellow; panel B). Panel C: Traditional structure-based pharmacophore hypothesis targeting the catalytic-site of ATX. Panel D: Revised ATX pharmacophore targeting the hydrophobic pocket. Three-dimensional spatial arrangements and distances between the centroids are represented in solid black lines. The pharmacophore features are shown as purple (hydrogen bond donor), red (hydrogen bond acceptor), cyan (hydrophobic group), and green (aromatic ring). The numbers represent distances between these functional groups.

Availability of the ATX crystal structure has provided understanding of the molecular surfaces important for the regulation of the lysophospholipase and phoshodiesterase enzymatic activity. Although previous drug discovery efforts have focused on targeting the catalytic site to develop competitive ATX inhibitors (Fig. 5A), our studies continue to exploit blocking the hydrophobic pocket with small molecules to have a strong inhibitory effect on the catalytic activity of ATX (Figs. 4 & 5) [15,16,19]. Current competitive ATX inhibitors (HA-155, e.g.; Fig. 5A) are designed to block ATX enzymatic activity by binding to the catalytic site, thus blocking both LPC and pNP-TMP binding/hydrolysis. Blocking the hydrophobic pocket, as achieved by our aromatic sulfonamide derivatives (Fig. 4), offers new opportunities for structure-based design of small-molecule competitive ATX inhibitors and supports the design of a more focused and structurally restricted pharmacophore model that no longer covers the entire LPC binding site (Fig. 5C) but instead is limited to the hydrophobic binding pocket (Fig. 5D).

In summary, we have identified aromatic sulfonamide derivatives as a new class of ATX inhibitors that are potent and competitive ATX inhibitors. Hydrophobic pocket inhibitors represent new chemical tools that may be useful in further development of ATX inhibitors. Because of their nanomolar potency and nonlipid properties, these hydrophobic pocket inhibitors are important lead compounds that may be useful as chemical tools for the further development of novel selective ATX inhibitors. Specific in silico, biochemical, and pharmacological assays targeting the hydrophobic pocket and the hydrophobic channel will need to be developed to guide the identification of novel types of ATX inhibitors.

Materials and Methods

Materials

The screening compound library was from the UC-DDC screening collection. The UC-DDC numbering nomenclature was used throughout out this study for compound identification. The compounds were dissolved in DMSO at a 10 mM stock concentration and stored at −80°C. For some studies, additional compounds were purchased from the Chembridge (San Diego, CA) screening collection (http://www.hit2lead.com). The compounds were more than 90% pure as certified by Hit2lead.com®. FS-3 and pNP-TMP substrates were from Echelon Biosciences (Salt Lake City, UT) and Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO), respectively.

Expression, Purification, and Activity of ATX

The expression, purification, and enzymatic assay conditions of human ATX and its Phe275Ala mutant were described previously [7,17].

Virtual Screening for ATX Inhibitors

Similarity Searching

A structural similarity search was conducted on the UC-DDC database using Molecular Operating Environment (MOE) [20] software. Specifically, the database was preprocessed with the module “wash,” which prepared the ligands with respect to protonation and tautomerization states, followed by generating molecular access keys fingerprints for each compound. Similarity searching was carried out independently for the three highly potent aromatic sulfonamide inhibitors from our HTS, compounds 918013, 897131, and 934313. For the similarity search tool, the Tanimoto coefficient was used as the similarity metric, set at a minimum of 0.8. In this step, the initial virtual subset of approximately 340,000 compounds was reduced by eliminating compounds that were distant from compounds 918013, 390596, and 406643 on the basis of their two-dimensional structural fingerprints. We analyzed the filtered databases of compounds obtained with the three parallel searches. The three filtered databases were merged to yield a library of 230 candidates selected for further analysis (Fig. S1).

Molecular Docking Analysis

The ATX structure was obtained by downloading a crystal structure of ATX complexed with HA155 inhibitor from the Protein Data Bank (PDB entry code 2XRG) into the MOE software. All water molecules, sugars, iodoacetamide, and nonpolar hydrogen atoms were removed, but the zinc heteroatoms records were retained. Search space was set as centered around the cocrystallized inhibitor HA155. Before docking, structures of compounds and ATX were preoptimized using the MOE software and saved in PDB format. The ATX macromolecule and all the compounds were imported into Autodock Tools [21]. Automated docking was performed using Autodock Vina [22].

Experimental Validation of in Silico Hits

ATX enzymatic activity was determined by measuring the hydrolysis of LPC species, FS-3, ADMAN-LPC, or pNP-TMP. In brief, compounds were initially tested at 10 μM. The enzyme reactions were conducted in buffer consisting of 10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.2, 10 mM MgCl2, and 0.1% bovine serum albumin. These assays contained 4 nM recombinant ATX and 1 μM FS-3. Compounds were added to the mixture to a final volume of 20 μl. Compounds that showed >50% inhibition of ATX in the primary assay were subsequently titrated in a 10-point dose-response reaction against the FS-3 substrate. These reactions were performed using 4 nM recombinant ATX with the indicated drug concentrations in reaction buffer and 1 μM FS-3 substrate in a total volume of 20 μl in 384-well plates for 120 min at room temperature. Fluorescence was measured using a FlexStation 3 plate reader (Molecular Devices; Sunnyvale, CA).

Compounds were also assayed for inhibition against ATX phosphodiesterase activity using the pNP-TMP substrate. The assay contained final concentrations of 4 nM ATX, 1 mM pNP-TMP, and 10 μM of compound in the assay buffer described above. Absorbance was monitored at 485 nm to measure enzyme activity for 2 h.

ADMAN-LPC at a final concentration of 30 μM was resuspended in assay buffer containing 2 mg/ml BSA with or without 10 μM inhibitor and 30 nM ATX. The reaction was incubated at 37°C for 4 h. Lipids were extracted using a modification of the Bligh and Dyer protocol by adding 3.5 volumes of citrate phosphate buffer (61.4 mM citric acid and 74.8 mM sodium phosphate; pH 4.0), before extraction with chloroform and methanol (2:1, v:v). Lipids were dried and resuspended in 30 μl of chlorform/methanol (1:1) and separated on silica gel 60 TLC plates (Merck) using CHCl3/MeOH/NH4OH (60:35:8 v/v/v). Fluorescent LPC and LPA species were visualized by UV transillumination and quantified by densitometric analysis using NIH ImageJ software [23] to quantify the inhibition of LPA production by ATX.

Inhibition of ATX-mediated Hydrolysis of LPCs by the Amplex Red Choline Release Assay

ATX inhibition by the selected compounds was assessed via the Amplex Red choline release assay. Triplicate wells were loaded with 60 μl of reaction cocktail in ATX assay buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, 5 mM CaCl2, 30 μM BSA; pH 7.4), resulting in overall concentrations of 100 μM lipid substrate, 0 or 10 nM ATX, and 0 or 10 μM inhibitor per well. Fluorescence was read initially and after 2 h incubation at 37°C with excitation and emission wavelengths of 560 and 590 nm, respectively. Relative fluorescence was recorded as a mean value of the triplicates for each sample and reported as % inhibition of ATX-mediated LPC hydrolysis.

Mechanism of Inhibition

ATX activity assays were used to determine the inhibitory mechanism based on nonlinear regression analysis as described previously [24,25]. Briefly, inhibitor concentrations of 0, 0.5, and 2 times the experimentally calculated IC50 value were used in conjunction with a range of 0.3–20 μM FS-3 substrate concentrations to determine the initial reaction rate. Background-corrected fluorescence at excitation and emission wavelengths of 485 and 528 nm was plotted as a function of time. A carboxyfluorescein standard curve was then used to transform the data, as carboxyfluorescein is analogous to the fluorescent product of ATX-mediated FS-3 hydrolysis and can be correlated as such in a 1:1 ratio. The reaction rate was then plotted versus substrate concentration and simultaneously fitted via nonlinear regression into the Michaelis-Menten equations for competitive, noncompetitive, uncompetitive, and mixed-mode inhibition (see below) using GraphPad Prism v5 (GraphPad Software Inc.; San Diego, CA). The mechanism of inhibition was assigned based on the model providing the highest global nonlinear fit (R2) value while simultaneously accounting for GraphPad’s interpretation rules for the calculated α value. According to GraphPad, the α value is a measure of affinity such that when α= 1, enzyme-substrate binding is not affected, and a noncompetitive mechanism is assigned. A very large α value indicates inhibitor interference with enzyme-substrate binding, denoting a competitive model. When the value of α is very small, the inhibitor enhances the binding of enzyme and substrate, and thus an uncompetitive model is indicated. Finally, an intermediate α value is indicative of mixed-mode inhibition. After the inhibitory mechanism was determined, the Ki (inhibitor affinity for the enzyme) was calculated based on the consequent regression analysis. In our case, the best fit was obtained when using the formula for competitive inhibition:

Cell Invasion Assay

Cell invasion was measured using 24-well invasion chambers (BD Biosciences; San Jose, CA) with the Matrigel-coated film insert (8 μm pore size) as described previously [7]. In brief, A2058 cells (5 × 104), which were resuspended in serum-free DMEM supplemented with 0.1% BSA, were added to the top compartment of the invasion chamber. The various compounds were preincubated in serum-free DMEM/0.1% BSA with recombinant ATX for 30 min at 37°C, followed by the addition of 1 μM LPC 18:1 to the bottom chamber. The invasion chambers were incubated at 37°C in 5% CO2 for 16 h. Next, the filter inserts were removed from the wells and transferred to a new 24-well plate containing 4 μg/ml of calcein AM (Molecular Probes, Invitrogen) in Hank’s balanced salt solution. After a 1-h incubation, the fluorescence of invaded cells was measured with a FLEXStation 3 plate reader at excitation and emission wavelengths of 485 and 530 nm, respectively.

Statistical Data Analysis

The data were plotted using Prism version 4 or 5 (GraphPad Software Inc.; San Diego, CA) and presented as mean ± S.D. For compounds that behaved as competitive inhibitors, the Ki was calculated by fitting the data at various FS-3 concentrations and comparing them with the value obtained via the Cheng-Prussoff equation.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Structure-activity study of novel class of ATX inhibitors

Identification of a new ATX inhibitor pharmacophore

Delineation of molecular interactions between aromatic sulfonamides and ATX

Demonstration that blocking the ATX hydrophobic pocket with aromatic sulfonamide compounds is sufficient to disrupt ATX/LPA axis in cell-based assays

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by National Institutes of Health National Cancer Institute [Grant CA092160], the American Cancer Society [Grant 122059-PF-12-107-01-CDD], and the Van Vleet Endowment.

List of non-standard abbreviations

- ADMAN-LPC

analog 3-acyl-7-dimethylaminonaphthyl - 1-LPC

- DMEM

Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium

- DMSO

dimethyl sulfoxide

- FS-3

fluorogenic substrate 3

- GPCR

G-protein coupled receptors

- HEK293T

human embryonic kidney cell line 293T

- HTS

high-throughput screening

- LPA

lysophosphatidic acid

- LPAR

LPA receptor

- LPC

lysophosphatidylcholine

- LPL

lysophospholipase

- NPP

nucleotide pyrophosphatase/phosphodiesterase

- PBS

phosphate-buffered saline

- PDE

phosphodiesterase

- PEG

polyethylene glycol

- pNP-TMP

p-nitrophenyl thymidine 5′-monophosphate

- UC-DDC

University of Cincinnati Drug Discovery Center

Footnotes

Figure showing the structures of the 38 active ATX inhibitors identified in this study are provided as Fig S1. Reported IC50 values for identified top aromatic sulfonamide compound are provided in Table S1. Results of the compounds screened at 10μM against FS-3 and pNP-TMP substrates are provided in Table S2.

References

- 1.Houben AJ, Moolenaar WH. Autotaxin and LPA receptor signaling in cancer. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2011;30:557–65. doi: 10.1007/s10555-011-9319-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nakanaga K, Hama K, Aoki J. Autotaxin--an LPA producing enzyme with diverse functions. J Biochem. 2010;148:13–24. doi: 10.1093/jb/mvq052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Okudaira S, Yukiura H, Aoki J. Biological roles of lysophosphatidic acid signaling through its production by autotaxin. Biochimie. 2010;92:698–706. doi: 10.1016/j.biochi.2010.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Liu S, Murph M, Panupinthu N, Mills GB. ATX-LPA receptor axis in inflammation and cancer. Cell Cycle. 2009;8:3695–701. doi: 10.4161/cc.8.22.9937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.van Meeteren LA, Moolenaar WH. Regulation and biological activities of the autotaxin-LPA axis. Prog Lipid Res. 2007;46:145–60. doi: 10.1016/j.plipres.2007.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.St-Coeur PD, Ferguson D, Morin P, Jr, Touaibia M. PF-8380 and closely related analogs: synthesis and structure-activity relationship towards autotaxin inhibition and glioma cell viability. Arch Pharm (Weinheim) 2013;346:91–7. doi: 10.1002/ardp.201200395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gupte R, et al. Benzyl and Naphthalene Methylphosphonic Acid Inhibitors of Autotaxin with Anti-invasive and Anti-metastatic Activity. Chem Med Chem. 2011;6:922–35. doi: 10.1002/cmdc.201000425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gierse J, et al. A novel autotaxin inhibitor reduces lysophosphatidic acid levels in plasma and the site of inflammation. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2010;334:310–7. doi: 10.1124/jpet.110.165845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Albers HM, van Meeteren LA, Egan DA, van Tilburg EW, Moolenaar WH, Ovaa H. Discovery and optimization of boronic acid based inhibitors of autotaxin. J Med Chem. 2010;53:4958–67. doi: 10.1021/jm1005012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ferry G, et al. S32826, a nanomolar inhibitor of autotaxin: discovery, synthesis and applications as a pharmacological tool. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2008;327:809–19. doi: 10.1124/jpet.108.141911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kawaguchi M, et al. Screening and X-ray Crystal Structure-based Optimization of Autotaxin (ENPP2) Inhibitors, Using a Newly Developed Fluorescence Probe. ACS Chemical Biology. 2013;8:1713–21. doi: 10.1021/cb400150c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Albers HM, Ovaa H. Chemical evolution of autotaxin inhibitors. Chem Rev. 2012;112:2593–603. doi: 10.1021/cr2003213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lipinski CA, Lombardo F, Dominy BW, Feeney PJ. Experimental and computational approaches to estimate solubility and permeability in drug discovery and development settings. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2001;46:3–26. doi: 10.1016/s0169-409x(00)00129-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nishimasu H, Ishitani R, Aoki J, Nureki O. A 3D view of autotaxin. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2012;33:138–45. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2011.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nishimasu H, et al. Crystal structure of autotaxin and insight into GPCR activation by lipid mediators. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2011;18:205–12. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hausmann J, et al. Structural basis of substrate discrimination and integrin binding by autotaxin. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2011;18:198–204. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fells JI, et al. Hits of a High-Throughput Screen Identify the Hydrophobic Pocket of Autotaxin/Lysophospholipase D as an Inhibitory Surface. Mol Pharm. 2013;84:415–424. doi: 10.1124/mol.113.087080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Willett P, Barnard JM, Downs GM. Chemical Similarity Searching. Journal of Chemical Information and Computer Sciences. 1998;38:983–996. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Koyama M, Nishimasu H, Ishitani R, Nureki O. Molecular dynamics simulation of Autotaxin: roles of the nuclease-like domain and the glycan modification. J Phys Chem B. 2012;116:11798–808. doi: 10.1021/jp303198u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Molecular Operating Environement (MOE) Software. Chemical Computing Group, Inc; Montreal: [Google Scholar]

- 21.Morris GM, Huey R, Lindstrom W, Sanner MF, Belew RK, Goodsell DS, Olson AJ. AutoDock4 and AutoDockTools4: Automated docking with selective receptor flexibility. J Comput Chem. 2009;30:2785–91. doi: 10.1002/jcc.21256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Trott O, Olson AJ. AutoDock Vina: improving the speed and accuracy of docking with a new scoring function, efficient optimization, and multithreading. J Comput Chem. 2010;31:455–61. doi: 10.1002/jcc.21334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schneider CA, Rasband WS, Eliceiri KW. NIH Image to ImageJ: 25 years of image analysis. Nat Methods. 2012;9:671–5. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hoeglund AB, Bostic HE, Howard AL, Wanjala IW, Best MD, Baker DL, Parrill AL. Optimization of a pipemidic acid autotaxin inhibitor. J Med Chem. 2010;53:1056–66. doi: 10.1021/jm9012328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.North EJ, Howard AL, Wanjala IW, Pham TC, Baker DL, Parrill AL. Pharmacophore development and application toward the identification of novel, small-molecule autotaxin inhibitors. Journal of medicinal chemistry. 2010;53:3095–105. doi: 10.1021/jm901718z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.