Abstract

Background

We assessed trajectories of children’s internalizing symptoms as predicted by interactions among maternal internalizing symptoms, respiratory sinus arrhythmia (RSA), and child sex.

Method

An ethnically and socio-economically diverse sample of children (n = 251) participated during three study waves. Children’s mean ages were 8.23 years (SD = 0.72) at T1, 9.31 years (SD = 0.79) at T2, and 10.28 years (SD = 0.99) at T3.

Results

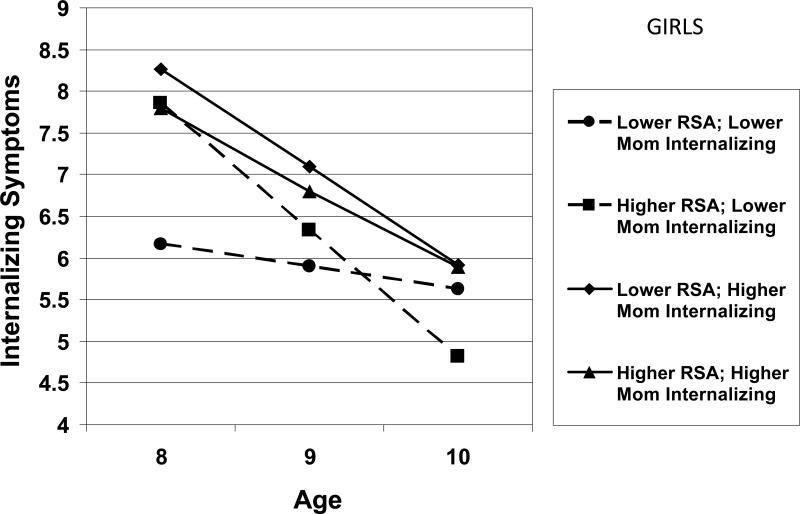

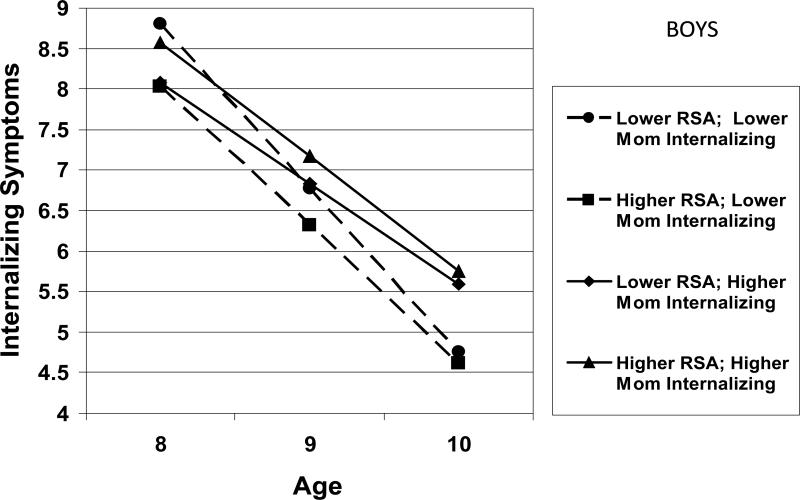

Multiple-indicator multilevel latent growth analyses showed maternal internalizing symptoms interacted with child RSA and sex to predict children's internalizing symptoms. Girls with higher RSA whose mothers had lower levels of internalizing symptoms showed the steepest decline in internalizing symptoms across time. Girls with lower RSA whose mothers had higher levels of internalizing symptoms showed the highest levels of internalizing symptoms at T3, whereas boys with higher RSA whose mothers had higher levels of internalizing symptoms showed the highest levels of internalizing symptoms at T3.

Conclusions

Findings build on this scant literature and support the importance of individual differences in children's physiological regulation in the prediction of psychopathology otherwise associated with familial risk.

Keywords: Internalizing symptoms, children, physiological regulation, respiratory sinus arrhythmia

Results from epidemiological studies illustrate rates of internalizing disorders increase dramatically during adolescence (Kessler et al., 2005) and show predictive validity for the development of subsequent depressive and anxiety disorders (Kovacs & Devlin, 1998). Comorbidity rates for depression and anxiety are typically reported to be 50% (Angold, Colstello, &Erkanli, 1999). Individuals diagnosed with internalizing disorders tend to show impairment across multiple domains and are at increased risk for suicide attempts (Bolton et al., 2008). Thus, it is important to identify risk and protective factors during childhood that influence the development of internalizing disorders. One promising approach is the study of how biological and environmental factors interact to predict individual differences in risk and resilience to psychopathology (Steinberg &Avenevoli, 2000).

Environmental factors such as parental depression (particularly maternal depression) and individual differences in physiological activity, including those pertaining to parasympathetic nervous system (PNS) activity, contribute to risks for internalizing disorders among children and adolescents (Shannon, Beauchaine, Brenner, Neuhas, &Gatzke-Kopp, 2007). As noted by developmental psychopathologists (Cicchetti & Rogosch, 2002), it is critical to consider individual differences in abnormal and normal development and how complex interactions of biological and environmental processes contribute to risk and protective factors for psychopathology. The current study is consistent with this perspective and aims to identify individual differences in physiological regulation that can exacerbate or ameliorate risk for child internalizing symptoms otherwise associated with maternal internalizing symptoms.

The goals of this study were twofold. First, we examined individual growth trajectories of children's internalizing symptoms from mean ages 8-10 and investigated the predictive role of maternal internalizing symptoms and children's basal respiratory sinus arrhythmia (RSA; an index of PNS functioning) in accounting for changes in children's internalizing symptoms over time. For children in this age group the 3-month prevalence rates for internalizing disorders range from 0.3 - 7.5% (Costello, Mustillo, Erkanli, Keeler, & Angold, 2003), highlighting the need to study individual differences in these disorders over time and to understand better trajectories of internalizing disorders prior to the dramatic increase observed in adolescence.Second, we examined interactions among maternal internalizing symptoms and children's RSA to identify trajectories of increased risk and/or resilience in the development of children's internalizing symptoms. Because sex has been associated with risk for internalizing symptoms (Hankin, Wetter, & Cheely, 2008), we also investigated child sex as a moderator of effects. We build on the current literature by using a longitudinal design, multiple reporters, and advanced statistical techniques to investigate if RSA moderates the link between maternal internalizing symptoms and the development of children's internalizing symptoms; to our knowledge, this is the first such examination in the literature.

Physiological/Biological Risks for Internalizing Symptoms

PNS activity is most commonly assessed via RSA, which is a measure of heart rate variability and provides a noninvasive index of parasympathetic control over the heart (Berntson, Cacioppo, & Grossman, 2007). It has been proposed that RSA during baseline conditions reflects the status of the PNS at rest and its capacity to react to environmental challenges (Porges, 2007). Further, RSA can be considered a stable individual difference across childhood and early adolescence (El-Sheikh, 2005a).

A large body of evidence suggests that children's RSA is an important factor in the development of adaptive and maladaptive behavior (Calkins & Keane, 2004; Beauchaine, 2001). Higher resting RSA is associated with a more organized response to stress through greater behavioral flexibility and adaptability (Porges, 1992), is related to positive emotionality (Oveis et al., 2009), and may function as a protective factor against the development of psychopathology(Shannon et al., 2007). Conversely, lower RSA is associated with poor self-regulation, and more problem behavior (Beauchaine, 2001). However, it is important to note that the relations between RSA and psychological adjustment are multifaceted (e.g., involve complex interactions between the PNS and the environment), may vary across age and context,and are most meaningful and coherent when viewed from a developmental psychopathology framework (Beauchaine, 2001; Obradovic, Bush, Stamperdahl, Adler, & Boyce, 2010).

Environmental Risks for Internalizing Symptoms

Children of mothers with internalizing disorders are at increased risk for developing symptoms of depression and anxiety (Garber & Cole, 2010; Micco et al., 2009). Children of depressed mothers are at least three times more likely to develop a mood disorder or other psychiatric problems compared to children of non-depressed mothers (Weissman, Wickamaratne, Moreau, &Olfson, 2006). Moreover, children of depressed mothers often demonstrate an earlier age of onset of depression, longer duration of depressive episodes, greater functional impairment, and a higher likelihood of recurrence compared to the offspring of non-depressed mothers (Goodman & Tully, 2006). Further, risk for anxiety disorders is particularly high in offspring of anxious mothers (Hirshfield-Becker, Micco, Simoes, &Henin, 2008), with children of mothers with anxiety disorders almost five times more likely to meet criteria for an anxiety disorder than children of non-anxious mothers (Beidel & Turner, 1997). Taken together, research has established that children of mothers with internalizing disorders have higher rates of depression and anxiety compared to normal control offspring.We controlled for fathers’ internalizing symptoms in the current study to provide a more direct assessment of relations between mothers’ and children’s internalizing symptoms.

Child Sex

Given the sex difference in internalizing symptoms (Hankin et al., 2008), baseline RSA (El-Sheikh 2005b; Salomon, 2005), and susceptibility to maternal depression (Goodman & Tully, 2006), we investigated if sex moderated associations among RSA, maternal psychopathology, and children's internalizing symptoms. Previous research has shown that boys have higher resting RSA levels than girls (e.g., El-Sheikh 2005b), although some studies have not found this relation (Suess, Porges, &Plude, 1994). In addition, there is evidence that sex moderates the association between maternal depression and offspring adjustment, with girls showing increased sensitivity to maternal depression, compared to boys (Goodman & Tully, 2006). Beginning in adolescence, girls (but not boys) show a marked increase in anxiety and depressive symptoms (Angold, Erkanli, Silberg, Eaves, & Costello, 2002), and comorbidity of anxiety and depressive disorders is more common in girls (Hankin et al., 2008). Given the previous research that supports sex differences in resting RSA, children's internalizing symptoms, and susceptibility to maternal depression, investigating potential moderation by sex is an important goal as such knowledge informs etiological theories on the development of internalizing symptoms.

Physiology/Biology X Family Risk Interactions

Despite clear evidence that indicates maternal internalizing symptoms elevate the risk for internalizing symptoms in children, not all children who are exposed to maternal psychopathology develop problems later in life (Masten, Best, &Garmezy, 1990). A comprehensive understanding of vulnerability and protective factors for the development of psychopathology requires consideration of biology by environment interactions (El-Sheikh & Erath, in press; Steinberg &Avenevoli, 2000). Findings to date suggest that higher RSA functions as a protective factor against adjustment problems in the context of family adversity (El-Sheikh, 2005a; El-Sheikh & Erath, in press). There are, however, few longitudinal studies that examine interactions between maternal psychopathology,especially internalizing symptoms,and children's RSA, in defining risk and resilience for the development of children's internalizing symptoms.

The current study builds upon previous work that investigated interactions between parental internalizing symptoms and children's RSAto predict children's conduct problems, depression, and emotion regulation (Blandon, Calkins, Keane, & O'Brien, 2008; Shannon et al., 2007). Shannon and colleagues (2007) showed 8- to 12-year-old children with higher RSA were protected from depressive symptoms, but less so the higher their mother's melancholic symptoms. Despite the significant contribution that the Shannon and colleagues’ (2007) paper makes toward a better understanding of risk and resilience, the study utilized a cross-sectional design and mothers reported on their depression symptoms as well as those of their children, a clear methodological limitation.

The Current Study

We assessed the predictive role of maternal internalizing symptoms in interaction with both children's RSA and sex to predict changes in children's internalizing symptoms over time. We hypothesized that children with higher levels of maternal internalizing symptoms and lower levels of RSA would be at increased risk for internalizing symptoms. In the context of higher levels of maternal internalizing symptoms, we expected that children with higher levels of RSA would be protected against initial levels and increases in internalizing symptoms. We also expected that relations between maternal internalizing symptoms and RSA in the prediction of children's internalizing symptoms would be more pronounced for girls given their sensitivity to environmental factors, such as maternal depression (Davies &Windle, 1997).

Method

Participants

Families participated in the three study waves. At T1, participants were 251 children (123 boys and 128 girls; age range = 6.67-10.67,M age = 8.23, SD = 0.72) and their parents from the Southeastern United States. Children were recruited from local schools. Second or third grade children from two parent homes in which parents had cohabitated for at least two years were eligible for participation. Children diagnosed with ADHD, learning disability, mental retardation, or chronic illness were not eligible for participation in order to decrease confounds that could affect results and to generalize findings to a normative population.Out of families whom we contacted from a list of names given to us by schools and who qualified for the study, 37% participated. To minimize nesting of data, only one child per family was included in the study. Children were not excluded if they took medication. Of the children on medication, approximately 2% of the sample (6 children) took medication for asthma and 1% (4 children) took medication for allergies. All procedures were approved by the Institutional Review Board.

Consistent with community demographics, the sample was comprised of 64% Europeanand 36% African- Americanchildren. Based on Hollingshead criteria (1975), the sample was diverse in relation to socioeconomic status (SES; M raw score = 37.38; SD = 9.92). The median family income was in the \$35,000 to \$50,000 range. Parents were either married or had been living together for an extended period (M = 10 years, SD = 5.67 years), and on average mothers and fathers were 33.40 (SD = 5.98 years) and 36.29 (SD = 6.62 years) years old, respectively. Most children (74%) lived with both biological parents; 26% lived with the mother and step-father or boyfriend.

One year later at T2 (M = 12.84 months, SD = 2.06, lag between T1 and T2), 217 children (105 boys and 112 girls) and their families returned (86% retention rate; children's age range = 7.58-11.92,M age = 9.31, SD = .79). One year after T2, (M = 11.34 months between T2 and T3, SD = 1.62 months) 183 children (88 boys and 95 girls) and their families returned at T3(85% retention rate from T2; children's age range = 8.83-13.17, M age = 10.28, SD = 0.99). Reasons for attrition included lack of interest in participating and geographic relocation.

Procedures

For brevity, only procedures and measures pertinent to the current investigation are discussed. At each study wave, families visited our university-based research laboratory. Parents’ and children's consent and assent for participation were obtained. Parents self-reported on several questionnaires while children completed questionnaires via interview with a trained researcher. In cases where the biological parents were separated or divorced, the live-in partner participated. Children participated in a physiological assessment session in which RSA measures were obtained. The child was left alone in the room for a 6-min adaptation period followed by a 3-min recorded baseline. Children were seated throughout the protocol and were asked to relax and not move much throughout the session.

Measures

Children's internalizing symptoms

At all waves, children reported on depressive symptoms using the 27-item Children's Depression Inventory (CDI; Kovacs, 1985); one item regarding suicidal ideation was excluded. The CDI has demonstrated good test-retest reliability and discriminant validity (Kovacs, 1985). In the current study, α’s = .71 to .95 across studywaves. Children reported on anxiety symptoms via the 28-item Revised Children's Manifest Anxiety Scale (RCMAS; Reynolds & Richmond, 1978). The RCMAS has demonstrated test-retest reliability and concurrent validity (James, Reynolds, & Dunbar, 1994). In the current study, α’s = .91 to .92.

Parents’ internalizing symptoms

At T1, mothers and fathers reported on their own internalizing symptoms using the Symptom Checklist-90-Revised (SCL-90-R; Derogatis, 1983). The Anxiety and Depression subscales were pertinent. The depression scale consisted of 13items (e.g., ‘feeling low in energy or slowed down’), and the anxiety scale was composed of 10items (e.g., ‘spells of terror or panic’). Likert-type response choices ranged from 1 (not at all) to 5 (extremely). The depression and anxiety scales were significantly correlated for mother-reports (r = .74, p < .001) and father-reports (r = .75, p < .001) and were summed to create an internalizing symptoms score for each parent. For the current study αs= .93 for mothers’ and .87 for fathers’ internalizing symptoms.

Marital conflict

Due to the link between marital conflict and children's internalizing problems (Cummings & Davies, 2010), and the role of RSA in the link between marital conflict and children's internalizing symptoms (El-Sheikh & Whitson, 2006), marital conflict was covaried. At T1, mothers and fathers reported on marital conflict perpetrated by the spouse using the Psychological/Verbal Aggression and Physical Aggression scales (αs = .71 to .96) of the Revised Conflict Tactics Scale (CTS2; Straus, Hamby, Boney-McCoy, &Sugarman, 1995). Children completed the 19-item Destructive Conflict scale of the Children's Perceptions of Interparental Conflict Scale (CPIC; Grych, Seid, &Fincham, 1992); α = .92. Children’s reports of marital conflict were significantly correlated with mothers’ and fathers’ reports. One marital conflict composite score was generated by standardizing and averaging parent and child reports.

RSA data acquisition and reduction

At T1, children's RSA was measured following standard guidelines (Berntson, Cacioppo, & Quigley, 1991). Two electrocardiography (ECG) electrodes were placed on the rib cage approximately 10-15 cm below the armpits. An additional electrode was used to ground the signal; for more detail see El-Sheikh, 2005b. A pneumatic bellows belt was placed around the chest to assess changes in respiration. A custom bioamplifier from SA Instruments (San Diego, CA) was used and the signal was digitized with the Snap-Master Data Acquisition System (HEM Corportation, Southfield, MI). To measure ECG, the bioamplifier was set for bandpass filtering with half power cutoff frequencies of .1 and 1,000 Hz and the signal was amplified with a gain of 500. The ECG signal was processed using the Interbeat Interval (IBI) Analysis System from the James Long Company (Caroga Lake, NY).

R-waves were identified using an automated algorithm. The R-wave times were converted to IBI's and resampled into equal time intervals of 125ms. In addition to computation of the mean and variance of heart period, the prorated IBIs were used for assessing heart period variability due to RSA. RSA during the baseline was calculated for the entire epoch. RSA was determined by the peak-to-valley method and all the units were in seconds; this methodology has been shown to be appropriate for quantifying RSA (Bernston et al., 1997).

Data Analytic Strategy

Multiple-indicator multilevel (MIML) latent growth analyses were conducted to examine individual changes in trajectories of children’s internalizing symptoms. MIML examines the growth curve of a latent variable created from multiple observed indicators through structural equation modeling (SEM) techniques, thus providing an extra level at the foundation of the model (Wu, Liu, Gadermann, &Zumboa, 2009). The MIML model consists of three levels: Level 1 (the measurement model); Level 2 (the latent growth model); and Level 3 (the inter-individual model). The use of multiple indicators in the Level 1 measurement model accounts for random and systematic measurement errors, and thus allows the modeling of growth and change in the true scores. At Level 2, the intercept growth factor and the slope growth factor are latent variables that describe individual trajectories in change over time. Predictors are included in the Level 3 model to examine relations among variables and the latent intercept and slope growth factors. Analyses were conducted in AMOS 18.

Because there were three time points (ages 8, 9, and 10) linear latent growth was modeled and all analyses followed established guidelines (Singer & Willett, 2003). Children's age, ethnicity, and SES were included as covariates. In addition, marital conflict and paternal internalizing symptoms were controlled1. Correlated variables, as shown in Table 1, were allowed to covary in the final model. All continuous predictor variables were mean centered and categorical variables were coded as 0 or 1 to facilitate interpretation (Aiken & West, 1991). Outlier data points (± 4 SD) were removed from the data file prior to data analysis.

Table 1.

Estimated Means, Standard Deviations, and Correlations

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Sex | -- | |||||||||||||

| 2. Age (T1) | −.20** | -- | ||||||||||||

| 3. Ethnicity | .04 | −.11 | -- | |||||||||||

| 4. SES | −.03 | .09 | −.21** | -- | ||||||||||

| 5. Marital Conflict | −.12 | .08 | −.03 | .01 | -- | |||||||||

| 6. Mom-Int | .01 | .01 | .03 | −.12 | .11 | -- | ||||||||

| 7. Dad-Int | −.08 | −.02 | .04 | −.10 | .22* | .15* | -- | |||||||

| 8. RSA | −.02 | .03 | .28** | −.08 | .08 | .04 | .10 | -- | ||||||

| 9. CDI age 8 | .04 | −.09 | .08 | −.05 | .07 | .03 | .01 | .01 | -- | |||||

| 10. RCMAS age 8 | .14* | −.16* | .13 | −.01 | .07 | .05 | .04 | .02 | .46** | -- | ||||

| 11. CDI age 9 | −.05 | −.09 | −.05 | −.05 | .10 | .03 | .04 | .03 | .42** | .28** | -- | |||

| 12. RCMAS age 9 | .05 | −.14* | .13 | .02 | .05 | .17* | .03 | −.01 | .34** | .56** | .44** | -- | ||

| 13. CDI age 10 | −.05 | −.15 | −.01 | −.12 | .05 | .10 | −.07 | −.05 | .40** | .28** | .37** | .34** | -- | |

| 14. RCMAS age 10 | .06 | −.23* | .25* | −.17* | −.07 | .10 | −.01 | .06 | .20** | .37** | .25** | .54** | .52** | -- |

| Mean | -- | 8.23 | -- | 37.38 | 4.04 | 4.74 | 3.42 | .15 | 7.90 | 11.52 | 7.15 | 9.84 | 4.85 | 7.66 |

| SD | -- | .72 | -- | 9.92 | 2.65 | 4.66 | 3.40 | .08 | 6.14 | 6.93 | 6.67 | 7.14 | 5.19 | 6.82 |

Note. Sex was coded 1 for females and 0 for males. Ethnicity was coded 0 for European Americans and 1 for African Americans.

SES = Socioeconomic status; RSA = Respiratory Sinus Arrhythmia; Mom-Int = Maternal Internalizing Symptoms; Dad-Int = Paternal Internalizing Symptoms; CDI = Children's Depression Inventory; RCMAS = Revised Manifest Anxiety Scale for Children

p< .05

p< .01.

An unconditional model was initially fit to determine variability in outcome measures. Next, a conditional growth model for children's internalizing symptoms was fit to assess the hypothesized interactions among study variables. Simple slopes for interactions were plotted at ± 1 SD and their significance was tested. These simple slopes are predicted trajectories for prototypical children (Curran, Bauer, & Willoughby, 2004).

Full-Information Maximum Likelihood (FIML) estimation was used to handle missing data, allowing all available data to be used in analyses. A missing-values analysis was conducted on the main study variables and covariates. At age 8, 248 children had data on internalizing symptoms; at age 9, 206 children (83% retention rate) had data on internalizing symptoms; at age 10, 165 children (80% retention rate from T2) had data on this outcome. Missingness of children's internalizing symptoms at Time 3 (i.e., the outcome variable) was not related to any study variables with one exception: children with higher CDI scores at T1 were more likely to havemissing data than children with lower CDI scores, t (248) = 2.72, p< .01.Children who did not return for Time 2 or Time 3 did not differ from those at Time 1 in regards to age, sex, race, or SES. Participants who did not participant at T2 did not return to the lab for T3, except for one family.

Results

Preliminary

Descriptive statistics and correlations among study variables are presented in Table 1. African American children demonstrated significantly higher levels of RSA compared to European American children, t (238) = -4.46, p< .001. Children's age at Time 1 was negatively correlated with anxiety symptoms across all time points. As expected, children's depressive and anxiety symptoms were positively correlated within and across time. Paternal internalizing symptoms were significantly correlated with maternal internalizing symptoms and marital conflict. Maternal internalizing symptoms at Time 1 were significantly correlated with the latent children's internalizing symptoms factor at Time 2, r = .16, p< 05. No significant relations were found among paternal internalizing symptoms at Time 1 and the latent children's internalizing symptoms factor at any time point.

Analyses

Unconditional Growth of Children's Internalizing Symptoms

A multi-level unconditional growth model was fit to examine developmental trajectories of children's internalizing symptoms across three years. CDI and RCMAS scores at ages 8, 9, and 10 composed latent variables that represented children's internalizing symptoms at each time point. The intercept represents the initial level of internalizing symptoms at age 8 and the slope represents growth across time. Individual variability around the intercept and slope were allowed to vary randomly. The unconditional latent growth model fit the data well, χ2 (6) = 9.96, p = .13, χ2/df= 1.66, CFI = .99, RMSEA = .05, p = .43. Significant individual variability was found for both the intercept (σ20 = 14.46, p< .001) and the slope (σ21 = 3.27, p< .001), indicating that this variability could be accounted for by adding predictors.

Conditional Growth of Children's Internalizing Symptoms

Maternal internalizing symptoms

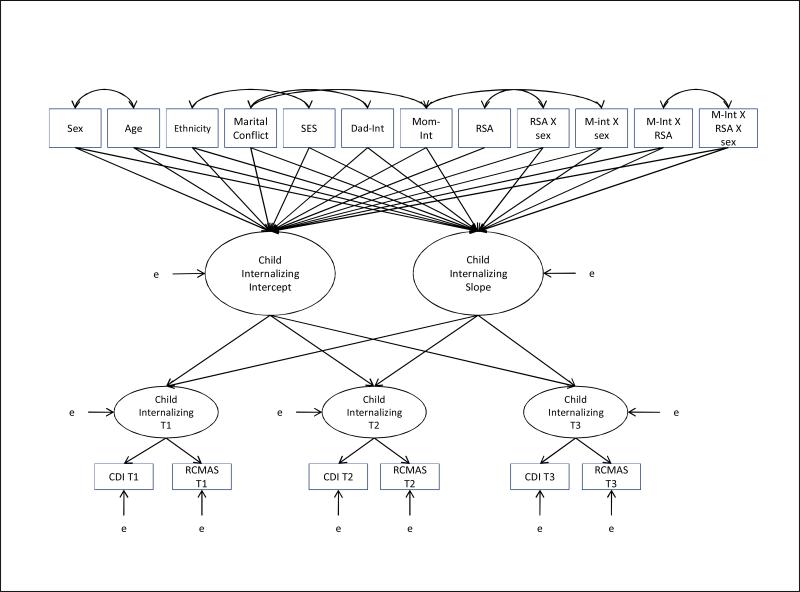

The conceptual multi-level conditional growth model is presented in Figure 1. Fit indices for this model were good, χ2 (122) = 195.95, p<.01, χ2/df= 1.61, CFI = .94, RMSEA = .05, p = .57. Parameter estimates for the model are presented in Table 2. Initial SES levels were significantly negatively related to the slope of children's internalizing symptoms (children with higher initial SES showed more steeply declining symptoms over time), β= -.29, p< .05. Also, children's initial age was marginally negatively related to internalizing symptoms at age 8 (younger children showed higher initial symptoms),β = -.14, p = .06. African American children demonstrated higher initial levels of internalizing symptoms than their European American counterparts, β = -.15, p = .05. Initial marital conflict was associated with higher initial levels of internalizing symptoms, and higher marital conflict was associated with more steeply declining levels of internalizing symptoms in children, β = .15, p =.05 and β = -.22, p =.08, respectively.

Figure 1.

The Conceptual Conditional Growth Model for Children's Internalizing Symptoms.

Table 2.

Parameter Estimates and Standard Errors for Conditional Growth Models of Children's Internalizing Symptoms Predicted by Maternal Internalizing Symptoms, RSA, Child Sex, and Their Interactions

| Children's Internalizing Symptoms |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept factor | ΔR2 | Slope factor | ΔR2 | |||||

| Predictor | B | SE | β | B | SE | β | ||

| Covariates | .104 | .193 | ||||||

| Sex | .836 | .520 | .125 | −.540 | .307 | −.215† | ||

| Age | −.056 | .030 | −.144† | −.015 | .018 | −.101 | ||

| Race | 1.068 | .546 | .153† | −.044 | .323 | −.017 | ||

| SES | .029 | .026 | .085 | −.036 | .016 | −.287* | ||

| Marital Conflict | .193 | .100 | .153† | −.104 | .059 | −.220† | ||

| Dad-Int | .021 | .087 | .021 | −.039 | .051 | −.104 | ||

| Main effects | .005 | .032 | ||||||

| Mom-Int | .121 | .079 | .167 | −.017 | .047 | −.061 | ||

| Baseline RSA (RSA) | .762 | 1.120 | .180 | −.727 | .660 | −.456 | ||

| 2-way interactions | .011 | .054 | ||||||

| Mom-Int × RSA | −.225 | .099 | −.241* | .151 | .058 | .429* | ||

| Mom-Int × sex | −.115 | .111 | −.112 | .079 | .066 | .204 | ||

| RSA × sex | −.504 | .671 | −.199 | .382 | .395 | .400 | ||

| 3-way interactions | .031 | .070 | ||||||

| Mom-Int × RSA × sex | .342 | .146 | −.245* | −.181 | .086 | −.345* | ||

| Total R2 | .150 | .350 | ||||||

Note. B = unstandardized coefficient, SE = standard error, β = standardized coefficient.

Sex was coded 0 for females and 1 for males. Race was coded 0 for European Americans and 1 for African Americans. SES = Socioeconomic status; MC = Marital Conflict; RSA = Respiratory Sinus Arrhythmia; Mom-Int = Maternal Internalizing Symptoms; Dad-Int = Paternal Internalizing Symptoms

p< .10

p< .05

Several two-way interactions were found on the intercept and slope, but these were subsumed under a significant three-way interaction (Maternal Internalizing Symptoms x Child RSA x Sex). Plotting this interaction (Figure 2a) revealed that children with higher RSA whose mothers reported lower internalizing symptoms demonstrated the lowest levels of internalizing symptoms at age 10; conversely, children with lower RSA whose mothers reported higher internalizing symptoms demonstrated the highest levels of internalizing symptoms at age 10. Figure 2a shows that girls with higher RSA whose mothers had lower levels of internalizing symptoms showed the steepest decline in trajectories of internalizing symptoms over time. In the context of lower levels of maternal internalizing symptoms and lower RSA, boys demonstrated significant decreases in internalizing symptoms over time (Figure 2b), whereas girls showed initially low levels of internalizing symptoms that did not significantly decline over time. Simple slope analyses revealed that all slopes depicted in Figures 2a and 2b significantly differed from zero (p< .01) except the slope for girls with lower RSA whose mothers had lower levels of internalizing symptoms. The model accounted for 15% of the variance in the intercept and 35% of the variance in the slope.

Figure 2.

Interaction among Maternal Internalizing Symptoms, RSA, and Sex to Predict Changes in Children's Internalizing Symptoms

Discussion

We examined growth trajectories of children's internalizing symptoms as predicted by interactions among maternal internalizing symptoms, children's physiological regulation indexed by RSA, and child sex. To our knowledge, this is the first longitudinal assessment of the moderating role of RSA in the link between mothers’ and children's internalizing symptoms and makes a significant contribution to the literature. Findings illustrate significant interactions among familial risk, children's physiological regulation, and sex. These results highlight the importance of contemporaneous assessment of physiological and familial risk factors in the prediction of child psychopathology.

Trajectories of children's internalizing symptoms decreased from ages 8 to 10, a pattern that is consistent with previous findings for this age group (Keiley et al., 2000). Although effects of both maternal and paternal internalizing symptoms in the context of children's RSA and sex were investigated, only the model which contained maternal internalizing symptoms predicted trajectories of children's internalizing symptoms.Results of the three-way interaction showed that girls with higher RSA in conjunction with lowerlevels of maternal internalizing symptoms exhibited the steepest decline in internalizing symptoms from ages 8 to 10. Conversely, girls with lower RSA whose mothers had higher internalizing symptoms had the highest levels of internalizing symptoms at age 10. These findings support higher levels of RSA coupled with lower levels of maternal internalizing symptoms as protective factors against the development of internalizing symptoms in children.

These results are consistent with findings from one of the few studies to examine children's RSA in the context of maternal depressive symptoms (Shannon et al., 2007), in that they support the protective role of higher RSA against children’s depressive symptoms, particularly for girls. In addition, our results support previous findings that indicate higher baseline RSA in conjunction with lower maternal depressive symptoms is associated with increases in emotion regulation capacities (Blandon et al., 2008). However, in contrast to findings by Blandon and colleagues (2008), ourresults indicate the relation among maternal internalizing symptoms, RSA, and trajectories of children's internalizing symptoms vary by sex. The present results are generally consistent with evidence supportive of the protective role of children's RSA in the associations amongparental alcoholism (El-Sheikh, 2005a) or family conflict (see El-Sheikh & Erath, in press; El-Sheikh, Harger, & Whitson, 2001) and children’s adjustment and extend them to maternal internalizing symptoms.

This study builds upon earlier conceptual and empirical work on the protective link between higher RSA and psychopathology. The protective function of higher RSA has been shown in cross-sectional (Shannon et al., 2007) and longitudinal studies (El-Sheikh & Whitson, 2006) andcan be attributed to the ways in which PNS activity reflects effective coping, behavioral flexibility, and emotion regulation (Beauchaine, 2001). Although previous findings indicate higher RSA ameliorates risk, our results indicate that higher RSA is especially protective when combined with low maternal risk. Indeed, girls with lower levels of maternal internalizing symptoms and higher RSA showed declines in internalizing symptoms over time and the lowest final levels of symptoms.

It is important to note the significant sex difference in the relations among RSA, maternal internalizing symptoms, and child internalizing symptoms. Although boys and girls with higher RSA and lower maternal internalizing symptoms showed similar decreases in internalizing symptoms, girls with lower RSA and lower maternal internalizing symptoms showed a different pattern than boys with similar characteristics.These girls did not show significant changes in internalizing symptoms from ages 8 – 10 and demonstrated higher levels on internalizing symptoms at age 10 compared to boys with similar characteristics. The significant interaction may be explained by the continuous slope for girls with low RSA and low maternal internalizing symptoms, although significant change in internalizing symptoms for other groups of children is theoretically meaningful. In addition, it is noteworthy that boys with higher RSA and higher maternal internalizing symptoms showed the greatest level of internalizing symptoms at age 10, compared to girls with similar characteristics, while boys with higher RSA and lower maternal internalizing symptoms exhibited consistently low levels of internalizing symptoms. Although these results were unexpected, some parallels can be drawn to theories of biological sensitivity to context and differential susceptibility to environmental influence (Ellis, Boyce, Belsky, Bakermans-Kranenbrug, & van Ijzendoorn, 2011) in which highly biologically sensitive individuals are more susceptible to protective and harsh environmental influences in a “for better and for worse” manner. These theorieshave tended to focus on stress reactivity (Ellis & Boyce, 2008) but the newer iteration of the theory (Ellis et al., 2011) construes sensitivity more broadly and suggests that high levels of resting RSA may be a component of biological sensitivity or capacity to engage with environments at a physiological level (Porges, 1992). If this is the case, then the finding that boys with higher levels of both RSA and maternal internalizing symptoms showed somewhat higher levels of internalizing problems than other boys at age 10 may fit with this new perspective (Ellis et al., 2011).

Several factors not measured in the current study may account for the observed sex-related effects. For example, compared to boys, girls experience more stress, react to stress differently (e.g., with greater depressive symptoms), and generate more interpersonal stress, any of which may contribute to their increased risk for internalizing symptoms (Hankin et al., 2008). Further, Goodman and Tully (2008) note that mechanisms of transmission of risk from mothers to children are likely to be gender-stereotyped, such as emotion socialization processes, coping styles, and relationship roles. Beauchaine (2009) notes that RSA effects can act differently in boys and girls and calls for future studies to investigate if biology X environmental interactions apply to both boys and girls.Thus, it is likely that additional factors affect girls and likely contribute to their different pattern of results.

Findings need to be interpreted within the study's context and limitations. The community sample consisted of school-recruited 8- to 10-year olds and their parents. Whether results would generalize to children and parents with clinically significant internalizing problems or of different ages is speculative. Further, although the use of three waves of data constitutes an advance in this developing literature, four or more waves are needed for explication of nonlinear trajectories. Although null findings were observed for fathers’ internalizing symptoms, such results should be interpreted cautiously pending replication. In addition, the outcome variable of the present study may have affected the (lack of) significant contribution of paternal internalizing symptoms. That is, previous studies have shown paternal internalizing symptoms predict boy's externalizing behaviors (Pfiffner, McBurnett, Rathouz, &Judice, 2005), rather than internalizing symptoms.

Despite these limitations, the present study makes important contributions towards a better understanding of the moderating role of RSA in the link between maternal and children's internalizing symptoms and highlights the importance of child sex in this context. In the context of scant cross-sectional investigations, this is the first known longitudinal study to address RSA as a protective or vulnerability factor against internalizing symptoms in the context of exposure to parental internalizing symptoms. Results highlight the importance of individual differences including physiological regulation and child gender for a better understanding of growth in children's internalizing symptoms in the context of family risk.

Key Points.

The study took a developmental psychopathology perspective to identifyenvironmental factors (e.g., maternal internalizing symptoms)and individual differences in physiological regulation that can exacerbate or ameliorate risk for child internalizing symptoms.

Multiple-indicator multilevel latent growth analyses indicated that maternal internalizing symptoms interacted with RSA and child sex in the prediction of children's internalizing symptoms.

Girls with higher RSA whose mothers had lower levels of internalizing symptoms showed the steepest decline in internalizing symptoms across time, whereas girls with lower RSA whose mothers had higher levels of internalizing symptoms showed the highest levels of internalizing symptoms at T3.

Findings support the importance of individual differences in children's physiological regulation as moderators of the link between maternal and children's internalizing symptoms.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by National Institute of Health Grant R01-HD046795. We wish to thank the staff of our Research Laboratory, most notably Lori Staton and Bridget Wingo, for data collection and preparation, and the school personnel, children, and parents who participated.

Footnotes

Declaration of Interest: We have no conflicts of interest to declare

An initial MIML growth model was fit for both maternal and paternal internalizing symptoms simultaneously to represent more accurately the family environment as an integrated whole. However, this model did not fit the data well, χ2 (167) = 739.98, p<.001, χ2/df= 4.43, CFI = .70, RMSEA = .12, p<.001, so a MIML model was fit for maternal internalizing symptoms separately. Additionally, an exploratory MIML growth model was fit for paternal internalizing symptoms. Although the model fit the data, χ2 (120) = 206.32, p<.01, χ2/df= 1.72, CFI = .95, RMSEA = .05, p = .35, paternal internalizing symptoms did not show any significant main effects or interactions to predict changes in children's internalizing symptoms over time. Null findings for paternal internalizing symptoms may be partially attributed to the large number of step-fathers (26%) in the current sample. For brevity, these results are not tabled; parameter estimates for this model are available upon request from the authors.

References

- Aiken LS, West SG. Multiple Regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Sage; Newbury Park, CA: 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Angold A, Costello EJ, Erkanli A. Comorbidity. The Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 1999;40:57–87. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angold A, Erkanli A, Silberg J, Eaves L, Costello EJ. Depression scale scores in 8-17-year-olds: Effects of age and gender. The Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2002;43:1052–1063. doi: 10.1111/1469-7610.00232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beauchaine T. Vagal tone, development, and Gray's motivational theory: Toward an integrated model of autonomic nervous system functioning in psychopathology. Development & Psychopathology. 2001;13:183–214. doi: 10.1017/s0954579401002012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beauchaine T. Some difficulties in interpreting psychophysiological research with children. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development. 2009;74 doi: 10.1111/j.1540-5834.2009.00509.x. 1, Serial No. 231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beidel DC, Turner SM. At risk for anxiety: I. Psychopathology in the offspring of anxious parents. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 1997;36:918–924. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199707000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berntson GG, Bigger JT, Jr., Eckberg DL, Grossman P, Kaufmann PG, Malik M, van der Molen MW. Heart rate variability: Origins, methods, and interpretive caveats. Psychophysiology. 1997;34:623–648. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8986.1997.tb02140.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berntson GG, Cacioppo JT, Grossman P. Whither vagal tone. Biological Psychology. 2007;74:295–300. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsycho.2006.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berntson GG, Cacioppo JT, Quigley KS. Autonomic determinism: The modes of autonomic control, the doctrine of autonomic space, and the laws of autonomic constraint. Psychological Review. 1991;98:459–487. doi: 10.1037/0033-295x.98.4.459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blandon AY, Calkins SD, Keane SP, O'Brien M. Individual differences in trajectories of emotion regulation processes: The effects of maternal depressive symptomatology and children's physiological regulation. Developmental Psychology. 2008;44:1110–1123. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.44.4.1110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolton JM, Cox BJ, Afifi TO, Enns MW, Bienvenu, O. J. Sareen J. Anxiety disorders and risk for suicide attempts: Findings from the Baltimore epidemiologic catchment area follow-up study. Depression and Anxiety. 2008;25:477–481. doi: 10.1002/da.20314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calkins SD, Keane SP. Cardiac vagal regulation across the preschool period: Stability, continuity, and implications for childhood adjustment. Developmental Psychobiology. 2004;45:101–112. doi: 10.1002/dev.20020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cicchetti D, Rogosch FA. A developmental psychopathology perspective on adolescence. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2002;70:6–20. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.70.1.6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costello EJ, Mustillo S, Erkanli A, Keeler G, Angold A. Prevalence and development of psychiatric disorders in childhood and adolescence. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2003;60:837–844. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.60.8.837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cummings EM, Davies PT. Marital conflict and children: An emotional security perspective. The Guildford Press; New York, NY: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Cummings EM, El-Sheikh M, Kouros CD, Keller PS. Children's skin conductance reactivity as a mechanism of risk in the context of parental depressive symptoms. The Journal of child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2007;48:436–445. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2006.01713.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curran PJ, Bauer DJ, Willoughby MT. Testing main effects and interactions in latent curve analysis. Psychological Methods. 2004;9:220–237. doi: 10.1037/1082-989X.9.2.220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies PT, Windle M. Gender-specific pathways between maternal depressive symptoms, family discord, and adolescent adjustment. Developmental Psychology. 1997;33:657–668. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.33.4.657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derogatis LR. SCL-90-R: Administration, scoring and procedures manual. Author; Minneapolis, MN: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Ellis BJ, Boyce WT. Biological sensitivity to context. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2008;17:183–187. [Google Scholar]

- Ellis BJ, Boyce WT, Belsky J, Bakermans-Kranenbrug MJ, van Ijzendoorn MH. Differential susceptibility to the environment: An evolutional-neurodevelopment theory. Development and Psychopathology. 2011;23:7–28. doi: 10.1017/S0954579410000611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Sheikh M, Erath SA. Family conflict, autonomic nervous system functioning, and child adaptation: State of the science and future directions. Development and Psychopathology. doi: 10.1017/S0954579411000034. (in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Sheikh M, Harger J, Whitson SM. Exposure to interparental conflict and children's adjustment and physical health: The moderating role of vagal tone. Child Development. 2001;72:1617–1636. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Sheikh M, Whitson SA. Longitudinal relations between marital conflict and child adjustment: Vagal regulation as a protective factor. Journal of Family Psychology. 2006;20:30–39. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.20.1.30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Sheikh M. Does poor vagal tone exacerbate child maladjustment in the context of parental problem drinking? A longitudinal examination. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2005a;114:735–741. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.114.4.735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Sheikh M. Stability of respiratory sinus arrhythmia in children and young adolescents: A longitudinal examination. Developmental Psychobiology. 2005b;46:66–74. doi: 10.1002/dev.20036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garber J, Cole DA. Intergenerational transmission of depression: A launch and grow model of change across adolescence. Development and Psychopathology. 2010;22:819–830. doi: 10.1017/S0954579410000489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman SH, Tully E. Depression in women who are mothers: An integrative model of risk for the development of psychopathology in their sons and daughters. In: Keyes CLM, Goodman SH, editors. Women and depression: A handbook for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Cambridge University Press; Cambridge, UK: 2006. pp. 241–282. [Google Scholar]

- Goodman SH, Tully E. Children of depressed mothers: Implications for the etiology, treatment, and prevention of depression in children and adolescents. In: Abela JRZ, Hankin BL, editors. Handbook of child and adolescent depression. Guilford Press; New York, NY: 2008. pp. 415–440. [Google Scholar]

- Grych JH, Seid M, Fincham FD. Assessing marital conflict from the child's perspective: The children's perception of interparental conflict scale. Child Development. 1992;63:558–572. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1992.tb01646.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hankin BL, Wetter W, Cheely C. Sex differences in child and adolescent depression: A developmental psychopathological approach. In: Abela JRZ, Hankin BL, editors. Handbook of child and adolescent depression. Guilford Press; New York, NY: 2008. pp. 377–414. [Google Scholar]

- Hirshfield-Becker DR, Micco J, Simoes NA, Henin A. High risk studies and developmental antecedents of anxiety disorders. American Journal of Medical Genetics Part C: Seminars in Medical Genetics. 2008;148C(2):99–117. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.c.30170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollingshead AB. Four factor index of social status. Yale University Press; New Haven, Conn: 1975. [Google Scholar]

- James EM, Reynolds CR, Dunbar J. Self-report instruments. In: Ollendick NJTH, King, Yule W, editors. International handbook of phobic and anxiety disorders in children and adolescents. Springer; New York, NY: 1994. pp. 317–330. [Google Scholar]

- Keiley MK, Bates J, Dodge K, Pettit G. A cross-domain analysis: Externalizing and internalizing behaviors during 8 years of childhood. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2000;28:161–179. doi: 10.1023/a:1005122814723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Berglund P, Demler O, Jin R, Merikangas KR, Walters EE. Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2005;62:593–602. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kovacs M. The Children's Depression Inventory (CDI). Psychopharmacology Bulletin. 1985;21:995–998. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kovacs M, Devlin B. Internalizing disorders in childhood. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 1998;39:47–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masten AS, Best KM, Garmezy N. Resilience and development: Contributions from the study of children who overcome adversity. Development and Psychopathology. 1990;2:425–444. [Google Scholar]

- Micco JA, Henin A, Mick E, Kim S, Hopkins CA, Biederman J, Hirshfield-Becker DR. Anxiety and depressive disorders in offspring at high risk for anxiety: A meta-analysis. Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 2009;23:1158–1164. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2009.07.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Obradovic J, Bush NR, Stamperdahl J, Adler NE, Boyce WT. Biological sensitivity to context: The interactive effect of stress reactivity and family adversity on socioemotional behavior and school readiness. Child Development. 2010;81:270–289. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2009.01394.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oveis C, Cohen AB, Gruber J, Shiota MN, Haidt J, Keltner D. Resting respiratory sinus arrhythmia is associated with tonic positive emotionality. Emotion. 2009;9:265–270. doi: 10.1037/a0015383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfiffner LJ, McBurnett K, Rathouz PJ, Judice S. Family correlates of oppositional and conduct disorders in children with attention deficit/ hyperactivity disorder. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2005;33:551–563. doi: 10.1007/s10802-005-6737-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porges SW. Vagal tone: A physiologic marker of stress vulnerability. Pediatrics. 1992;90:498–504. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porges SW. The polyvagal perspective. Biological Psychology. 2007;74:116–143. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsycho.2006.06.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds CR, Richmond BO. What I think and feel: A revised measure of children's manifest anxiety. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 1978;6:271–280. doi: 10.1007/BF00919131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salomon K. Respiratory sinus arrhythmia during stress predicts resting respiratory sinus arrhythmia 3 years later in a pediatric sample. Health Psychology. 2005;24:68–76. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.24.1.68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shannon KE, Beauchaine TP, Brenner SL, Neuhas E, Gatzke-Kopp L. Familial and temperamental predictors of resilience in children at risk for conduct disorder and depression. Development and Psychopathology. 2007;19:701–727. doi: 10.1017/S0954579407000351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singer JD, Willett JB. Applied longitudinal data analysis: Modeling change and event occurrence. Oxford University Press; New York: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Steinberg L, Avenevoli S. The role of context in the development of psychopathology: A conceptual framework and some speculative propositions. Child Development. 2000;71:66–74. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Straus MA. Manual for the Conflict Tactics Scale. Family Research Laboratory, University of New Hampshire; Durham, NH: 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Suess PE, Porges SW, Plude DJ. Cardiac vagal tone andsustained attention in school-age children. Psychophysiology. 1994;31:17–22. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8986.1994.tb01020.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weissman MM, Wickramaratne P, Normura Y, Warner V, Pilowsky D, Verdeli H. Offspring of depressed parents: 20 years later. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2006;163:1001–1008. doi: 10.1176/ajp.2006.163.6.1001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu AD, Liu Y, Gadermann AM, Zumbo BD. Multiple-indicator multilevel growth model: A solution to multiple methodological challenges in longitudinal studies. Social Indicators Research: International Interdisciplinary Journal for Quality of Life Measurement. 2010;97:123–142. [Google Scholar]