Neonatal encephalopathy caused by perinatal hypoxiaischemia in term newborn infants occurs in 1 to 3 per 1000 births1 and leads to high mortality and morbidity rates with life-long chronic disabilities.2,3 Although therapeutic hypothermia is a significant advance in the developed world and improves outcome,4,5 hypothermia offers just 11% reduction in risk of death or disability, from 58% to 47%. Therefore, there still is an urgent need for other treatment options. Further, there are currently no clinically established interventions that can be given antenatally to ameliorate brain injury after fetal distress.

One of the major limitations to progress is what may be called “the curse of choice.” A large number of possible neuroprotective therapies have shown promise in pre-clinical studies.6,7 How should we select from them? There is no consensus at present on which drugs have a high chance of success for either antenatal or postnatal treatment. There are insufficient societal resources available to test them all. Thus, it is imperative to marshal finite resources and prioritize potential therapies for investigation. The authors believe that facilitating discussion of strategy and findings in “competing” laboratories is critical to facilitate efficient progress toward optimizing neuroprotection after hypoxia-ischemia.

Few studies have examined possible interactions of medications with hypothermia and whether combination therapies augment neuroprotection. The timing of the administration of medications may be critical to optimize benefit and avoid neurotoxicity (eg, early acute treatments targeted at amelioration of the neurotoxic cascade compared with subacute treatment that can promote regeneration and repair). Intervention early on in the cascade of neural injury is likely to achieve more optimal neuroprotection8,9; however, there is frequently little warning of impending perinatal hypoxia-ischemia episodes. Sensitizing factors such as maternal pyrexia,10 maternal/fetal infection,11,12 and poor fetal growth13 are well recognized and contribute to the heterogeneity of the fetal response and outcome in neonatal encephalopathy. We include potential antenatal therapy medications in the scoring process; however, electronic fetal monitoring has a low positive predictive value (3%–18%) for identifying intrapartum asphyxia.14–18 At present, therefore, any antenatal intervention potentially involves treatment of many cases that do not need treatment in order to benefit a few at risk of brain injury.

In January 2008, investigators from research institutions with a special interest in neuroprotection of the newborn appraised published evidence about medications that have been used in pre-clinical animal models, pilot clinical studies, or both as treatments for: (1) antenatal therapy for fetuses with a diagnosis of antenatal fetal distress at term; and (2) postnatal therapy of infants with moderate to severe neonatal encephalopathy. The aims of this study were to: (1) prioritize potential treatments for antenatal and postnatal therapy; and (2) provide a balanced reference for further discussions in the perinatal neuroscience community for future research and clinical translation of novel neuroprotective treatments of the newborn.

Methods

A systematic PubMed search up to June 2011 was undertaken to identify medications with evidence of neuroprotection in pre-clinical studies when given either antenatally or postnatally after perinatal hypoxia-ischemia. For antenatal treatments, each medication was scored to a manual score of 60 by using 6 questions, each ranked 1 to 10: (1) placental transfer; (2) ease of administration; (3) knowledge about starting dose; (4) adverse effects; (5) teratological or toxic effects; and (6) overall benefit and efficacy. For postnatal treatments, each drug was scored to a total possible score of 50 by using 5 questions, each scored 1 to 10: (1) ease of administration; (2) knowledge about starting dose; (3) adverse effects; (4) teratological or toxic effects; and (5) overall benefit and efficacy.

The 12 authors represent perinatal neuroscience research groups from The Netherlands, United Kingdom, United States, Sweden, and New Zealand. Two to 3 medications were assigned to each member; each member was asked to evaluate the scientific literature, score the assigned medications, and present this evidence to the group, justifying the scores. General guidance for the scores were: score 0 to 3, no evidence or some significant concerns; score 4 to 5, some evidence or some concerns; score 6 to 8, good evidence or minor concerns; and score 9 to 10, compelling evidence and no significant concerns. Final scores reflected the opinion of the whole group. A total of 5 meetings were held, the first by Skype (Microsoft Skype Division, Luxembourg City, Luxembourg) in January 2009, and the final meeting was held in May 2011.

Results

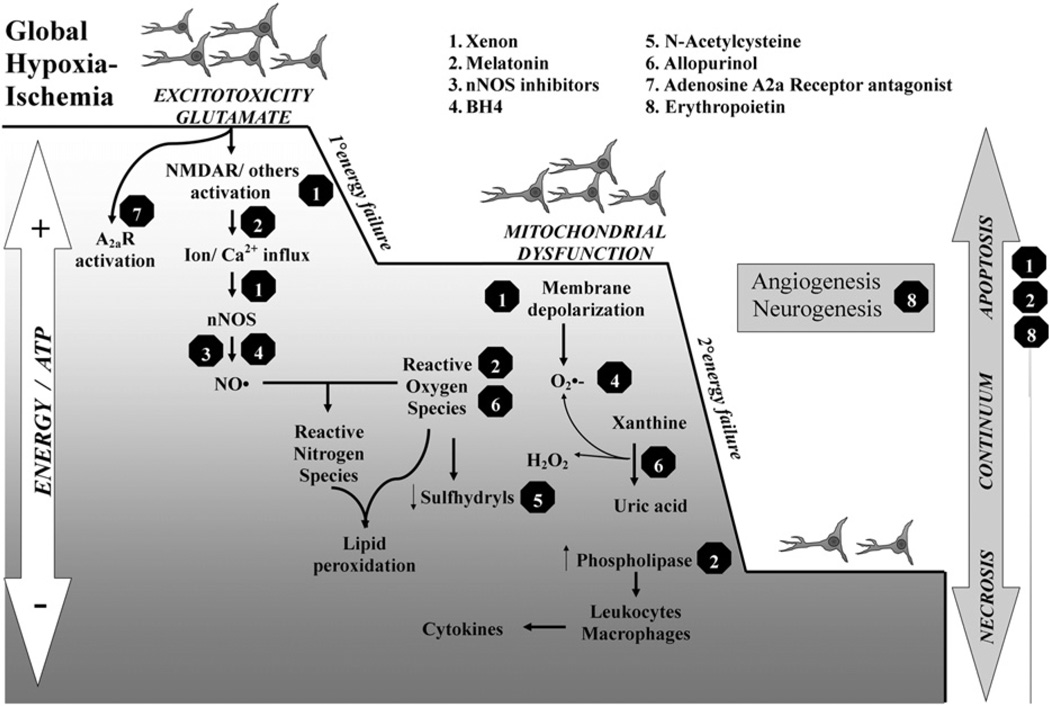

Thirteen neuroprotective medications were identified. The possible mechanisms of action are shown in the Figure. They were classified as US Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved (adenosine A2A receptor antagonist, allopurinol, erythropoietin [Epo], melatonin, memantine, N-acetylcysteine [NAC], resveratrol, topiramate, vitamins C & E, tetrahydrobiopterin [BH4]) and non-FDA-approved (Epo-mimetic peptides, neuronal nitric oxide synthase [nNOS] inhibitors, xenon).

Figure.

Simplified schematic representation of putative neurotoxic cascade targets for some promising medications. After global hypoxia-ischemia, glutamate-induced excitotoxicity proceeds via NMDA receptor activation, producing Ca2+ influx and therefore activation of Ca2+-dependent NOS, particularly nNOS. At high concentrations, NO• reacts with superoxide (O•−) to produce peroxynitrite (ONOO−), which in turn induces lipid peroxidation and mitochondrial nitrosylation. Consequently, mitochondrial dysfunction and membrane depolarization develop with further release of O•− and decline in sulfhydryls, such as glutathione. Ca2+ also triggers other mechanisms including: (1) the irreversible proteolytic conversion of xanthine dehydrogenase to xanthine oxidase producing significant amounts of O•− and H2O2 in the process; and (2) the activation of cytosolic phospholipases, increasing eicosanoid release and inflammation. During the acute energy depletion, some cells undergo primary cell death, the magnitude of which will depend on the severity and duration of hypoxia-ischemia. After reperfusion, the initial hypoxia-induced cytotoxic edema and accumulation of excitatory amino acids typically resolve in 30 to 60 minutes, with apparent recovery of cerebral oxidative metabolism. It is thought that the neurotoxic cascade is largely inhibited during the latent phase and that this period provides a “therapeutic window.” Cerebral oxidative metabolism may then secondarily deteriorate 6 to 15 hours later (termed secondary energy failure in studies using phosphorus-31 or proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy). This phase is marked by the onset of seizures, secondary cytotoxic edema, accumulation of cytokines, and mitochondrial failure. Mitochondrial failure is a key step leading to delayed cell death. The degree of energy failure influences the type of cell death displayed by neurons during early and delayed stages, the degree of trophic support influences the angiogenesis and neurogenesis during the recovery phase after hypoxia-ischemia. Each treatment shown targets single or multiple points in the cascade initiated by hypoxia-ischemia, and many show potential effects by improving neuronal survival, regeneration, or both.

Potential Antenatal Neuroprotective Therapies to be Given to the Mother in Whom Fetal Distress is Detected

The medication with the highest score was BH4 (score 54/60, 90%), which was chosen for ease of administration, absence of teratological effects, and potential benefit. Melatonin (49/60, 82%) was the second choice, because of ease of administration and placental transfer and benefit. The medications with the lowest scores were topiramate and memantine (6/60, 10%). nNOS inhibitors were ranked third (75%). Xenon scored 42 of 60 (70%) and was ranked fourth; most points were lost in the “ease of administration” category. Allopurinol was ranked fifth (67%), followed by vitamins C and E (39/60, 65%). NAC, Epo-mimetics, Epo, resveratrol, and adenosine A2A receptor antagonists all scored <60% (Table I).

Table I.

Potential antenatal neuroprotective therapies to be given to the mother in whom fetal distress is detected

| BH4 | Melatonin | nNOS inhibitors |

Xenon | Allopurinol | Vitamin C and E |

NAC | Epo mimetic peptides |

Epo | Resveratrol | Adenosine A2A receptor antagonist |

Memantine | Topiramate | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ease of administration | 10 | 10 | 10 | 2 | 7 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 7 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Starting dose | 10 | 7 | 10 | 8 | 6 | 5 | 5 | 3 | 3 | 5 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Placental transfer | 8 | 10 | 8 | 10 | 10 | 7 | 1 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Side effects | 8 | 7 | 6 | 7 | 4 | 4 | 6 | 6 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Teratological effects | 10 | 8 | 1 | 8 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 8 | 10 | 10 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Benefit | 8 | 7 | 10 | 7 | 3 | 3 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 4 | 5 | 1 | 1 |

| FDA approved | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes |

| Total score (maximum 60) | 54 | 49 | 45 | 42 | 40 | 39 | 37 | 37 | 32 | 30 | 10 | 6 | 6 |

| Rank (% score) | 1 (90%) | 2 (82%) | 3 (75%) | 4 (70%) | 5 (67%) | 6 (65%) | 7 (57%) | 7 (57%) | 8 (53%) | 9 (50%) | 10 (17%) | 11 (10%) | 11 (10%) |

Medications are ranked from highest (left) to lowest score (right).

Each item is marked out of 10 and totalled to give an overall score of 60.

10 = highest; 0 = lowest

Potential Postnatal Neuroprotective Therapies to be Given as Rescue Therapies in Moderate to Severe Neonatal Encephalopathy

The medication with the highest score was melatonin (45/50; 90%), the medication with the second highest score was Epo (86%), and the medication with the third highest score was NAC (80%). The drugs with the lowest scores were BH4 and nNOS inhibitors (both 10%). Epo-mimetics were ranked fourth (38/50, 76%). Allopurinol was ranked fifth (35/50, 70%), and xenon was ranked sixth (34/50, 68%). Resveratrol, vitamins C and E, memantine, topiramate, and adenosine A2A receptor antagonists scored between 68% (resveratrol) and 44% (adenosine A2A receptor antagonists; Table II).

Table II.

Potential postnatal neuroprotective therapies

| Melatonin | Epo | NAC | Epo mimetic peptides |

Allopurinol | Xenon | Resveratrol | Vitamins C and E |

Memantine | Topiramate | Adenosine A2A receptor antagonist |

nNOS inhibitors |

BH4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ease of administration | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 7 | 4 | 8 | 9 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 1 | 1 |

| Starting dose | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 8 | 6 | 5 | 6 | 5 | 4 | 5 | 1 | 1 |

| Adverse effects | 10 | 8 | 10 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 4 | 6 | 6 | 5 | 8 | 1 | 1 |

| Teratological/neurodegenerative effects | 10 | 10 | 10 | 7 | 10 | 8 | 10 | 8 | 10 | 9 | 2 | 1 | 1 |

| Benefit | 8 | 8 | 3 | 6 | 3 | 8 | 6 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 5 | 1 | 1 |

| FDA approved | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes |

| Total score (maximum 50) | 45 | 43 | 40 | 38 | 36 | 34 | 33 | 33 | 27 | 25 | 22 | 5 | 5 |

| Rank (% score) | 1 (90%) | 2 (86%) | 3 (80%) | 4 (76%) | 5 (72%) | 6 (68%) | 7 (66%) | 7 (66%) | 8 (54%) | 9 (50%) | 10 (44%) | 11 (10%) | 11 (10%) |

Medications are ranked from highest scores (left) to lowest score (right).

Each item is marked out, and the total is combined to give the overall score of 50.

10 = highest optimal score; 0 = lowest score.

The top 6 medications in both the antenatal or postnatal category are reviewed below, because a ranking in the top 6 suggests that these drugs are most likely to reach the clinical arena in the next 5 to 10 years. Putative mechanisms of neuroprotection are summarized in the Figure.

Tetrahydrobiopterin (FDA Approved)

BH4 (antenatal therapy, rank 1: score 90%; postnatal therapy, rank 11: score 10%) is an important co-factor for a number of enzymes, such as aromatic amino acid hydroxylases, which convert phenylalanine to tyrosine (phenylketonuria), tyrosine to L-dopa, and tryptophan to 5-hydroxytryptophan and nitric oxide synthase (NOS). It is synthesized de novo from guanosine triphosphate by 3 enzymatic reactions controlled by guanosine triphosphate cyclohydrolase I, 6-pyruvoyl-tetrahydropterin synthase, and sepiapterin reductase. Deficits in these enzymes result in motor disturbances, such as dopa-responsive dystonia. A newly identified defect in sepiapterin reductase causes motor disabilities and mental disturbances in children early in life. BH4 is a developmental factor determining the vulnerability of fetal brain to hypoxiaischemia. There is evidence that BH4 deficiency can exacerbate oxidative injury19 and that neonatal hypoxia-ischemia can cause relative BH4 deficiency.20 Maternal treatment with BH4 increased fetal levels in basal ganglia and significantly ameliorated motor deficits and decreased stillbirths.21

Transfer of BH4 was demonstrated in mice and also for an BH4 analog in rabbits,21,22 but placental transfer is untested in humans.

There have been extensive safety trials for the application of BH4 therapy in humans,23 including human pregnancy.24 From long-term follow-up in humans, BH4 in a wide range of doses has no adverse events.20,25 Doses of 10 mg/kg per day have been used without problems,24,26,27 although for purposes of neuroprotection a higher dose may need to be given. BH4 in the synthetic preparation form sapropterin dihydrochloride, was approved by FDA for use in pregnancy with certain provisos.

There are no known adverse effects, but more extensive studies in pregnant women need to be done.

No teratological effects have been documented.

BH4 levels increase during normal fetal development21 and are crucial for brain development. In rabbits, maternal supplementation with sepiapterin can significantly increase the BH4 levels in the fetal brain and decrease the incidence of motor deficits or death after fetal hypoxia-ischemia.21 In addition to disrupting normal neurotransmitter production in the brain, hypoxia-ischemia reduces the availability of BH4 in the brain. Such decreases in BH4 levels with hypoxia-ischemia could contribute to the severity of neurological outcomes from hypoxia-ischemia. Substantial amounts of BH4 can be detected in cerebrospinal fluid when given peripherally to patients with hyperphenylalaninemia caused by defective biopterin synthesis. Treatment with BH4 can ameliorate some cases of dystonia,28,29 further emphasizing the importance of BH4 in the development of motor disturbances. There have been no studies of the combination of BH4 with therapeutic hypothermia after hypoxia-ischemia. It is unknown whether long-term supplementation is required for prevention/amelioration of hypoxia-ischemia injury or whether acute administration at the time of fetal distress would be effective. However, the safety and efficacy profile make BH4 supplementation an excellent candidate for further study.

Melatonin (FDA Approved)

Melatonin (N-acetyl-5-methoxytryptamine; antenatal therapy, rank 2: score 82%; postnatal therapy, rank 1: score 90%) is produced mainly by the pineal gland, allowing the entrainment of circadian rhythms of several biological functions.30 Melatonin actions are mediated through specific receptors,31 but it can also function as an antioxidant32 and has anti-apoptotic effects.33

Because of its lipophilic properties, melatonin easily crosses most biological cell membranes, including the placenta34–36 and the blood-brain barrier.37

Melatonin can be administered intravenously, although it needs to be dissolved in an excipient, such as alcohol or propylene glycol. Oral doses show good uptake in tissues, even in patients who are critically ill.38 A neonatal intravenous formulation needs to be developed; it is unclear how much melatonin is absorbed after oral or rectal doses in infants who have been cooled and asphyxiated.

A wide range of melatonin doses were used in various species to treat brain injury. An intraperitoneal melatonin dose of 0.005 mg/kg is neuroprotective in newborn mice,39 and doses as high as 200 mg/kg have been administered to pregnant rats throughout most of pregnancy without adverse effects to either the mother or the offspring.40 The optimal neuroprotective dose still needs to be determined, although a 5-mg/kg infusion for 6 hours started 10 minutes after resuscitation and repeated at 24 hours augmented hypothermic neuroprotection in the newborn piglet.41

Continuous infusion of a relatively high dose of melatonin (20 mg/kg/h for 6 hours) to fetal sheep after intrauterine asphyxia resulted in slower recovery of fetal blood pressure after umbilical cord occlusion, without changes in fetal heart rate, acid base status, or mortality rate.42 Melatonin has been used safely in children with sleep abnormalities related to neurological disease43 and in septic newborns without serious adverse effects.44

There are no clinical safety studies of antenatal melatonin administration; however, animal studies indicate that even doses as high as 200 mg/kg for several days during pregnancy in rats do not have toxic effects on either mother or fetus.40 Melatonin has very low toxicity in clinical studies.45

Several animal studies have shown neuroprotective benefits from melatonin treatment, both when given before and after birth. When administered directly to the sheep fetus after umbilical cord occlusion, melatonin attenuated the production of 8-isoprostanes and reduced the number of activated microglia cells and terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase dUTP nick end labeling (TUNEL)-positive cells in the brain.42 Maternal administration (1 mg bolus, then 1 mg/h for 2 hours) also prevented subsequent increase in free radical production in fetal sheep exposed to intrauterine asphyxia.46 Low-dose melatonin (0.1 mg/kg/day) administered to the mother for 7 days at the end of pregnancy reduced signs of cerebral inflammation and apoptosis after birth asphyxia in the spiny mouse.47 Evidence from both clinical and experimental studies supports the safety of melatonin antenatally, with no teratological or other toxic effects.

Clinically, melatonin appears to have beneficial effects when given to children who were both asphyxiated48 and septic.44 After birth, melatonin can protect against excitotoxic lesions induced by ibotenate in newborn mice. Given in low doses (0.005–5 mg/kg i.p.), melatonin reduced brain lesions in the white matter >80%, and melatonin was still (but less) effective when given 4 hours after the insult39 and reduced learning deficits.49 Protection of the cerebral white matter has also been shown after 2 hours of hypoxic insults in newborn rats,50 and melatonin decreased microglial activation and astroglial reaction and promoted oligodendrocyte maturation in growth restricted rat pups.51 Furthermore, in a model of lipopolysacchride-induced hypoxic-ischemic injury in neonatal rats, melatonin reduced injury by 45% when given repeatedly at 5 mg/kg, and a higher dose (20 mg/kg) did not significantly protect the brain.52

nNOS Inhibitors (Not FDA Approved)

Nitric oxide (NO; antenatal therapy, rank 3: score 75%; postnatal therapy, rank 11: score 10%) is produced in excessive amounts early in the reoxygenation/reperfusion phase after perinatal hypoxia-ischemia. NO is a ubiquitous intercellular messenger and signaling molecule53 and is important for neuronal survival, differentiation, and precursor proliferation.54 Three different isoforms of NOS have been identified: the endothelial (eNOS), nNOS, both constitutionally present, and inducible NOS (iNOS). All NOS-isoforms are upregulated after hypoxia-ischemia. The toxic effects of NO may be produced by its reaction with superoxide to form peroxynitrite and other reactive nitrogen species, although NO can also have direct effects on mitochondria. In hypoxia-ischemia, however, NO is involved in the early phase injury and during the secondary energy failure that occurs from 6 to 48 hours after the primary event.55 The higher the nNOS activity, the more likely the region would be infarcted by stroke. In a 14- to 18-day-old rat stroke model, core NOS activity was always greater than penumbral NOS activity.56 This suggests that short-term inhibition of NO in hypoxia-ischemia should be preferred compared with long-term inhibition.

Neonatal mice lacking the gene for nNOS are less vulnerable to hypoxic-ischemic brain injury. The favorite nNOS inhibitor previously was 7-nitroindazole (7-NI). 7-NI, 100 mg/kg, given after carotid artery ligation but 30 minutes before hypoxia in 7-day rats protected against cerebral hypoxia-ischemia injury.57 In a dose of 1 mg/kg before hypoxia-ischemia to 3- to 5-day old piglets, 7-NI decreased caspase immunoreactivity and DNA fragmentation.58 In adult stroke, protection by 7-NI has been inconclusive.59 This may reflect non-specific inhibition of eNOS, causing a decrease in cerebral blood flow, worsening hypoxia.59 With a new fragment-based de novo design approach, novel and more specific nNOS inhibitors were developed.60,61 With the help of radiography diffraction and crystal structure determination,62 a series of compounds have been developed that have much higher in vitro specificity and potency than available nNOS inhibitors.60,62 These new inhibitors are at least few hundred fold more specific than 7-NI.

Placental transfer has not been tested in humans. In rabbits, a theoretical dose of 150 binding affinity for equilibration in total blood volume resulted in 50% inhibition of NO produced in the fetal brain, indicating both placental and blood-brain transfer.

The new compounds, HJ619 and JI-8, tested in a perinatal model of hypoxia-ischemia are water-soluble and can be given intravenously. Starting dose is unknown. The minimum effective dose of inhibition of nNOS has not been shown in animal models.

Adverse effects are also unknown. Doses as high as 8 mg/kg (15.8 µmoles/kg) of JI-8 were tested and found to have no obvious toxicity in rabbits.63 Teratological effects are unknown.

The new compounds, HJ619 and JI-8, inhibited fetal brain NOS activity in vivo, reduced NO concentration in the fetal brain, and dramatically ameliorated deaths and number of newborn kits exhibiting signs of cerebral palsy in a rabbit model.62 These compounds have also shown to be superior to 7-NI; at the same 15.8 µmoles/kg dose, 7-NI did not show neuroprotection and decreased maternal blood pressure steadily during the medication’s administration, and JI-8 did not, indicating that 7-NI could be acting on eNOS.63

Inhibition of eNOS is deleterious, but nNOS inhibition is neuroprotective in perinatal hypoxia-ischemia.53 Recent studies with the combination of 7-NI and aminoguanidine have demonstrated long-lasting protection with combined inhibition of nNOS and iNOS.64 However, 1-(2-trifluoromethylphenyl) imidazole, another inhibitor of both nNOS and iNOS, showed worse outcome after whole body ischemia.65 Another dual inhibitor, 2-iminobiotin, showed protection only in female rat pups after hypoxiaischemia, but the protection was independent of the NO pathway.66,67

Xenon (Not FDA Approved)

Xenon (antenatal therapy, rank 4: score 70%; postnatal therapy, rank 6: score 68%) has been shown to be a very safe anesthetic and potent neuroprotectant. Xenon is a non-competitive antagonist of the N-methyl-D aspartate (NMDA) subtype of the glutamate receptor.68 Other actions include activation of the background two-pore K+-channel,69 inhibition of the calcium/calmodulin dependent protein kinase II,70 activation of anti-apoptotic effectors Bcl-XL and Bcl-271, and induced expression of hypoxia inducible factor 1 alpha and its downstream effectors Epo and vascular endothelial growth factor, which can interrupt the apoptotic pathway.72

Inhalational anesthetics can cross the placental barrier, but there is no suppression of the newborn because of the fast plasma clearance.73 Inhalational analgesia could be an ideal strategy for the fetus before delivery.

A disadvantage of xenon is its cost (approximately $20 per liter) and thus the need for closed-circuit delivery and recycling systems, which can be overcome with recirculating xenon neonatal ventilators.

According to the current level of knowledge, xenon is not teratogenic74 nor has it been associated with neurodegeneration; rather it has been seen to reduce isoflurane-induced neuronal death.71,75

Xenon rapidly crosses the blood-brain barrier because of its very low blood-gas partition co-efficient.76 When administered concurrently with hypoxia in neonatal rats, xenon decreased brain injury, with a significant effect at concentrations of 40% atm and greater.77 When administered after the insult, only concentrations ≥60% atm were protective 4 hours after hypoxia-ischemia. However, when combined with hypothermia, a 90-minute exposure to the combination of xenon 20% atm and hypothermia at 35°C 4 hours after the hypoxic insult was neuroprotective. Thus, cooling and hypothermia appear to have a synergy in some models77 and are additive in others.78

Xenon is an attractive agent to use in the sick newborn because of its cardiovascular stability,79 myocardial protective properties,80 and ability to rapidly cross the blood-brain barrier. Xenon has previously been used in neonates in assessment of cerebral blood flow, without adverse effects.81

There are no neuroprotective studies of antenatal xenon treatment. However, in an in vivo model of neonatal asphyxia involving hypoxic-ischemic injury to 7-day-old rats, preconditioning with 70% xenon 4 hours before hypoxia-ischemia reduced infarction size 7 days after and improved neurologic function 30 days after injury.82 Phosphorylated cyclic adenosine 3′,5′-monophosphate-response element binding protein was increased with xenon exposure. Also, the pro-survival proteins Bcl-2 and brain-derived neurotrophic factor were upregulated with xenon treatment.

After the discovery that xenon is an antagonist of the NMDA subtype of the glutamate receptor,68 several groups have demonstrated xenon neuroprotection in in-vitro83,84 and in-vivo models.77,78,85 Combined xenon and cooling is effective even when xenon administration is delayed for some hours.86,87 Neuroprotective effects have been demonstrated by 50% xenon continued for 24 hours started 2 hours after hypoxiaischemia with hypothermia in piglets.88 Xenon alone without hypothermia did not provide significant neuroprotection on the basis of proton (1H) magnetic resonance spectroscopy biomarkers and transferase dUTP nick end labeling (TUNEL)-positive cells in one model,88 but provided additive histological benefit to cooling in another piglet model.89 An alternative strategy to minimize costs is to use a combination of 20% xenon and 1.5% sevoflurane, which was effective as a pre-conditioning stimulus to protect against subsequent hypoxiaischemia90; however, there are potential concerns about the neurotoxicity of sevoflurane in the neonatal brain.91–93

Further advances in delivery technology will be required before translation to clinical trials. Xenon was given to 12 infants with neonatal encephalopathy undergoing therapeutic hypothermia in a pilot study by Thoresen et al.94 The first 6 infants received increasing xenon concentrations from 25% to 50% for 3 to 12 hours, and infants 6 to 12 received 50% xenon for 12 hours. Fifty percent xenon was sedative, and the heart rate dropped by 10%, but there was no hypotension or change in cardiac output. A cuffed tube was used to minimize xenon loss. Two phase II clinical trials are planned in the United Kingdom. A phase II clinical trial in Bristol will assess the incremental benefit of adding 50% xenon to therapeutic hypothermia. The Medical Research Council-funded clinical trial in London will use 30% xenon for 24 hours to be started within 12 hours after birth as long as cooling is started within 6 hours.

In summary, the exact concentration and duration of xenon therapy needed for neuroprotection in newborn infants is unclear.

Allopurinol (FDA Approved)

Allopurinol (antenatal therapy, rank 5; score 65%; postnatal therapy, rank 5: score 72%) is an inhibitor of xanthine oxidase, and xanthine dehydrogenase. Xanthine oxidase is a ready source of superoxide and hydrogen peroxide in its reaction with the purines, xanthine and hypoxanthine. Allopurinol is thought to act indirectly as an antioxidant, although it is a weak antioxidant by itself.

Allopurinol crosses the placenta.

The intravenous form is a very alkaline solution. The oral form may not be suitable for mothers who are candidates for general anesthesia. High doses are needed for antenatal neuroprotection. Because allopurinol needs to prevent oxidant production by xanthine oxidase, it must be administered early.

Maternal allopurinol (500 mg) during fetal hypoxia, indicated with non-reassuring fetal heart rate tracing or fetal scalp pH <7.20, lower cord blood levels of S-100B in human pregnancies in which fetal hypoxia was suspected at >36 weeks gestation.95 Studies in immature rats found that allopurinol treatment (135 mg/kg subcutaneous) 15 minutes after hypoxia-ischemia reduced brain edema and long-term brain damage.97 Preservation of cerebral phosphorus-31 (31P) MRS energetics was found in a study of pre-treatment with allopurinol in neonatal rats, suggesting that neuroprotection may be attributed in part to preservation of energy metabolites.98

In contrast with rodents, humans do not have high circulating levels of xanthine oxidase. However, there are supporting human data. In randomized controlled trials in adults, high-dose allopurinol (>10 mg/kg) reduced reperfusion injury in patients undergoing coronary bypass grafting surgery.99 Further, in infants with hypoplastic left heart syndrome who undergo deep hypothermic cardiac arrest, pre-treatment with allopurinol reduced postoperative adverse cardiac and neurological outcomes.100,101 A Cochrane review in 2008102 suggested that meta-analysis of data from 3 clinical trials did not reveal a statistically significant difference in the risk of death during infancy or incidence of neonatal seizures.103–105 There was no significant effect on neurodevelopmental outcome in surviving children in the one trial that assessed it.103 The antenatal allopurinol for reduction of birth asphyxia induced damage (ALLO) trial has started in the Netherlands96 as a randomized double-blind placebo-controlled multicenter study to test 500 mg of intravenous allopurinol in pregnant women at term with suspected intrauterine hypoxia. Primary outcomes are S100B and oxidative stress in umbilical cord blood. A recent study suggested benefit in a subgroup of infants with moderate encephalopathy.106

Vitamins C and E (FDA Approved)

Ascorbic acid (AA) or vitamin C (antenatal therapy, rank 6: score 65%; postnatal therapy, rank 7: score 66%) can scavenge free radicals at supraphysiological concentrations107; however, AA does not penetrate the blood-brain barrier. Its oxidized form, dehydroascorbic acid (DHA), enters the brain by means of facilitative transport.

AA does not easily diffuse across cell membranes, but can be oxidized to DHA in the stomach. DHA is uncharged and readily passes through cell membranes. DHA diffuses passively across the placenta; the placenta can also transport AA by a sodium-dependent mechanism, possibly using the same transporter as glucose.108

Intravenous administration of DHA allows supraphysiologic concentrations of ascorbate to be achieved in the brain, whereas AA administration does not. A dose of 250 mg/kg or 500 mg/kg DHA administered at 3 hours post-ischemia reduced infarct volume by 6- to 9-fold, to only 5% with the highest DHA dose (P < .05).

Teratological and adverse effects have not been documented.

When given before ischemia, DHA was associated with dose-dependent increase in post-reperfusion cerebral blood flow, with reductions in neurological deficit and mortality. In reperfused cerebral ischemia, mean infarct volume was reduced from 53% and 59% in vehicle- and AA-treated animals, respectively, to 15% in 250 mg/kg DHA-treated animals (P < .05).109 In rat pups, there was no benefit from postnatal treatment after hypoxia-ischemia with Mito vitamin E, a mitochondrial antioxidant.110 However, in a study in asphyxiated rat pups, the combination of methylprednisolone with vitamin E therapy reduced hypoxia-ischemia brain damage significantly.111 Only one randomized-controlled clinical study in term infants who were asphyxiated has been performed, which found that the combination of AA with ibuprofen had no effect on outcome at 6 months of age.112

N-Acetylcysteine (FDA Approved)

NAC (antenatal therapy, rank 7: score 57%; postnatal therapy, rank 3: score 80%) is a precursor of glutathione and can therefore act as an anti-oxidant and is also a scavenger of oxygen free radicals.113 NAC is used clinically for mucolysis and as an antidote for paracetamol intoxication in high doses (150–300 mg/kg daily).

NAC-dependent effects have been reported after oral, intraperitoneal, or intravenous administration. In most experiments to evaluate neuroprotective effects of NAC, repeated or chronic administration has been used. There is no consensus on a neuroprotective dose, and a wide range of concentrations have been used in experimental studies, from 25 mg/kg in neonatal mice to 1 g/kg (orally) in pregnant rats.

No teratological effects are known, and NAC usage is believed to be safe during pregnancy in humans.114 Of concern, two experimental studies reported adverse effects. When pregnant mice were administered two doses of NAC immediately after and 3 hours after LPS, NAC aggravated LPS-induced preterm labor.115 In fetal sheep, NAC exacerbated LPS-induced fetal hypoxemia and hypotension and induced polycythemia.116 NAC is also associated with adverse reactions that limit its use in humans, particularly anaphylactic reactions, including rash, pruritus, angioedema, bronchospasm, tachycardia, and hypotension,117 usually occurring within 2 hours of the initial infusion.

In humans, NAC is transported across the placenta,118 although transport across the blood-brain barrier is believed to be poor, and therefore it has been assumed that NAC is exerting its neuroprotective action at the level of the vascular bed.119

Only studies showing protective effects against injury caused by in utero inflammation in the fetal brain have been reported. Intraperitoneal pre-treatment of E18 pregnant rats with NAC (50 mg/kg) attenuated LPS-induced expression of inflammatory mediators in fetal rat brains and prevented postnatal LPS-induced hypomyelination.120 NAC administered to pregnant rats in their drinking water (500 mg/kg/day), from E17 to birth, prevented LPS-induced oxidative stress in the hippocampus of male fetuses and completely restored long-term potentiation in the hippocampus and spatial recognition performance in male 28-day-old offspring.121 Post-treatment with NAC, 4 hours after the LPS challenge, prevented loss of glutathione in hippocampus and improved spatial learning deficits.122

Gressens et al found a neuroprotective effect of NAC (25–250 mg/kg) after excitotoxic brain injury model in neonatal mice.123 Further, after LPS-sensitized hypoxic-ischemic brain injury in neonatal rats, NAC (200 mg/kg) provided marked neuroprotection, with as much as 78% reduction of brain injury, which was associated with improvement of the redox state and inhibition of apoptosis.52 Beneficial effects of NAC have also been demonstrated in non-rodent studies. After neonatal hypoxia-reoxygenation in piglets, NAC (150-mg/kg bolus and 20 mg/kg/h, intravenous for 24 hours) reduced cerebral oxidative stress with improved cerebral oxygen delivery and reduced caspase-3 and lipid hydroperoxide concentrations in cortex.124 In a similar study, hypoxiareoxygenation-induced cortical hydrogen peroxidase was reduced with NAC.125 Combination therapy of systemic hypothermia (30.0 ± 0.5°C, 2 hours) induced immediately after neonatal hypoxia-ischemia and NAC (50 mg/kg, i.p. daily until sacrifice) significantly improved neonatal reflexes and reduced both white and grey matter damage 4 weeks after hypoxia-ischemia.126

Erythropoietin (FDA Approved)

In vitro, the Epo receptor (antenatal therapy, rank 7: score 53%; postnatal therapy, rank 2: score 86%) is expressed in hippocampal and cerebral cortical neurons,127 and neuronal messenger RNA expression of Epo is markedly increased in response to hypoxia.128 Epo triggers several different signaling pathways via receptor binding. Neuroprotective effects have been associated with Janus kinase/Stat5 activation and nuclear factor kappa B phosphorylation,129 and Stat5 and Akt are required for neurotrophic effects of Epo.130 Epo also stimulates other growth factors, including vascular-endothelial growth factor secretion131 and brain-derived neurotrophic factor,132 which may be beneficial in the injured brain.

Epo is not an appropriate antenatal therapy because little if any crosses the human placenta.133 If an Epo-responsive condition were present in the fetus, it is conceivable that Epo could be administered via umbilical cord infusion, but this seems cumbersome and not clinically feasible in the setting of fetal hypoxic injury.

Epo has been administered intravenously or subcutaneously. It requires small volumes, so it does not impose a fluid burden. The most commonly used treatment regimens used to stimulate erythropoiesis in neonates is 400 U/kg 3 times a week given subcutaneously or 200 U/kg daily given intravenously. The optimal dose, number of doses, or dosing interval for Epo neuroprotection in humans have not yet been determined. In rodent stroke models, it is clear that multiple doses are more effective than a single dose, with 3 doses of 1000 U/kg given immediately after injury, 24 hours, and 7 days later showing equivalent benefit to 3 doses of 5000 U/kg given at 24 hour intervals for 3 days after injury.134,135 It is known that neuronal apoptosis is prolonged after brain injury and that neurogenesis and angiogenesis play a part in brain repair. Epo effects include decreasing neuronal apoptosis while increasing neurogenesis and angiogenesis, so a longer duration of therapy might provide optimal outcomes.

There are no known teratogenic effects.

Neonatal Epo treatment has been studied in randomized controlled trials of erythropoiesis, with few reported adverse effects, and the medication is thought to be safe at doses ranging as high as 2100 units/kg/week.136,137 Complications seen in adults (eg, hypertension, clotting, seizures, polycythemia, and death) have not been observed in infants. Angiogenesis may be an important adverse effect in preterm infants at risk for retinopathy of prematurity.

There are extensive data in vitro and in vivo demonstrating both early and late benefit mediated by the multimodal effects of Epo.138 After hypoxia-ischemia in neonatal rodents, Epo facilitated recovery of sensorimotor function,139 improved behavioral and cognitive performances,140 and preserved integrity of cerebral tissue.141 Human trials are just beginning, but show promise.142–144

Epo-Mimetics (Not FDA Approved)

The possibility of developing Epo-mimetic peptides (antenatal therapy, rank 7: score 57%; postnatal therapy, rank 4: score 76%) that have specific subsets of Epo characteristics has been of great interest, because these molecules might circumvent unwanted clinical effects or provide improved permeability with the ability to cross the placenta or blood-brain barrier. The tissue protective functions of Epo can be separated from its stimulatory action on hematopoiesis, and novel Epo derivatives and mimetics, such as asialo-Epo145,146 and carbamylated Epo,147–149 have been developed. Epotris is a peptide which corresponds to the C alpha-helix region (amino-acid residues 92–111) of human Epo and which has neuroprotective properties.150 No studies have been done to assess safety or efficacy of these compounds as perinatal treatments.

Discussion

The opinions expressed in this review are meant to generate further discussion and to promote international coordination; they are not meant as firm recommendations. Both the choice of agent and the scores are subjective, but are informed by the authors’ earlier experience and knowledge. We acknowledge that many new promising drugs, some of which target specific pathways,156 have been left out. However, this is an ongoing process, and the study group plans to continuously update the priority scoring on the basis of new evidence and welcomes input from other investigators. We also did not consider medications that had undergone extensive clinical trials in this review, such as magnesium sulfate. Most of the positive evidence with magnesium sulfate is for the preterm population151; pre-clinical and clinical evidence for magnesium sulfate in term hypoxia-ischemia is less good than other approaches152,153; and term infants may have significant risk of hypotension at high doses.154

Medications targeting antenatal neuroprotection (before or during an acute hypoxic-ischemic insult and administered to the mother) are likely to have different properties from those showing benefit after an hypoxic-ischemic insult. For example, BH4 scored highest as an antenatal neuroprotective agent, whereas it scored lowest as a postnatal neuroprotective agent. This discrepancy may partly reflect a lack of postnatal studies of its neuroprotective effects and suggests the need for such evidence. Melatonin, however, scored high for both antenatal and postnatal neuroprotection; this emphasizes the remarkable safety, efficacy, and ease of administration of this medication and suggests that melatonin has strong potential to be translated to the clinic for clinical trials in babies with encephalopathy. Epo scored second highest for postnatal therapies; however, because it does not cross the placenta, it is impractical for antenatal therapies. More work is needed on safety and efficacy studies with Epo mimetics, but these compounds are also promising.

Many of the challenges in neonatal neuroprotection research are also faced in translational research in adult stroke. A disturbingly large number of potential therapies that were effective in animals were not proven effective in subsequent clinical trials.155 It is unclear whether this reflects lack of rigor in testing, differences in the pattern and evolution of cell death between rodents and humans, or laboratory conditions.156 To address these concerns, the Stroke Therapy Academic Industry Roundtable group proposed that criteria for agents in clinical trials157 should include adequate dose-response and serum concentration measurements; confirmation of efficacy in relevant time windows; the use of physiological and behavioral outcome measures in animal studies instead of only infarct size; use of multiple types of stroke models; trials in larger species; and reproducibility of pre-clinical results by independent laboratories.158

This collaboration is intended to support a similar platform of continuous review and discussion in the perinatal and neuroscience communities and help promote cooperative work on the most promising therapies to ensure rapid translation to the clinic. We hope that this collegial and cooperative approach will improve efficiency and future successes in neonatal neuroprotection studies.

Glossary

- 7-NI

7-nitroindazole

- AA

Ascorbic acid

- BH4

Tetrahydrobiopterin

- DHA

Dehydroascorbic acid

- eNOS

Endothelial nitric oxide synthase

- Epo

Erythropoietin

- FDA

US Food and Drug Administration

- NAC

N-acetylcysteine

- iNOS

Inducible nitric oxide synthase

- NMDA

N-methyl-D aspartate

- NO

Nitric oxide

- NOS

Nitric oxide synthase

- nNOS

Neuronal nitric oxide synthase

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Kurinczuk J, White-Koning M, Badawi N. Epidemiology of neonatal encephalopathy and hypoxic-ischaemic encephalopathy. Early Hum Dev. 2010;86:329–338. doi: 10.1016/j.earlhumdev.2010.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Marlow N, Rose A, Rands C, Draper ES. Neuropsychological and educational problems at school age associated with neonatal encephalopathy. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2005;90:F380–F387. doi: 10.1136/adc.2004.067520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Robertson CM, Finer NN, Grace MG. School performance of survivors of neonatal encephalopathy associated with birth asphyxia at term. J Pediatr. 1989;114:753–760. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(89)80132-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Edwards A, Brocklehurst P, Gunn A, Halliday H, Juszczak E, Levene M, et al. Neurological outcomes at 18 months of age after moderate hypothermia for perinatal hypoxic ischaemic encephalopathy: synthesis and meta-analysis of trial data. BMJ. 2010;340:C363. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gluckman P, Wyatt J, Azzopardi D, Ballard R, Edwards A, Ferriero D, et al. Selective head cooling with mild systemic hypothermia after neonatal encephalopathy: multicentre randomised trial. Lancet. 2005;365:663–670. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)17946-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kelen D, Robertson NJ. Experimental treatments for hypoxic ischaemic encephalopathy. Early Hum Dev. 2010;86:369–377. doi: 10.1016/j.earlhumdev.2010.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cilio M, Ferriero D. Synergistic neuroprotective therapies with hypothermia. Semin Fetal Neonatal Med. 2010;15:293–298. doi: 10.1016/j.siny.2010.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Carroll M, Beek O. Protection against hippocampal CA1 cell loss by post-ischaemic hypothermia is dependent on delay of initiation and duration. Metab Brain Dis. 1992;7:45–50. doi: 10.1007/BF01000440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gunn A, Gunn T, Gunning M, Williams C, Gluckman P. Neuroprotection with prolonged head cooling started before postischemic seizures in fetal sheep. Pediatrics. 1998;102:1098–1106. doi: 10.1542/peds.102.5.1098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Badawi N, Kurinczuk JJ, Keogh JM, Alessandri LM, O’Sullivan F, Burton PR, Pemberton PJ, Stanley FJ. Intrapartum risk factors for newborn encephalopathy: the Western Australian case-control study. BMJ. 1998;317:1554–1558. doi: 10.1136/bmj.317.7172.1554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lehnardt SML, Follett P, Jensen FE, Ratan R, Rosenberg PA, Volpe JJ, et al. Activation of innate immunity in the CNS triggers neurodegeneration through a Toll-like receptor 4-dependent pathway. PNAS. 2003;100:8514–8519. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1432609100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Eklind S, Mallard C, Leverin AL, Gilland E, Blomgren K, Mattsby-Baltzer I, et al. Bacterial endotoxin sensitizes the immature brain to hypoxic-ischaemic injury. Eur J Neurosci. 2001;13:1101–1106. doi: 10.1046/j.0953-816x.2001.01474.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Badawi N, Kurinczuk JJ, Keogh JM, Alessandri LM, O’Sullivan F, Burton PR, et al. Antepartum risk factors for newborn encephalopathy: the Western Australian case-control study. BMJ. 1998;317:1549–1553. doi: 10.1136/bmj.317.7172.1549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Williams KP, Galerneau F. Comparison of intrapartum fetal heart rate tracings in patients with neonatal seizures vs. no seizures: what are the differences? J Perinat Med. 2004;32:422–425. doi: 10.1515/JPM.2004.140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kumar S, Paterson-Brown S. Obstetric aspects of hypoxic ischemic encephalopathy. Early Hum Dev. 2010;86:339–344. doi: 10.1016/j.earlhumdev.2010.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Williams KP, Galerneau F. Intrapartum fetal heart rate patterns in the prediction of neonatal acidemia. Am J Obstet Gynaecol. 2003;188:820–823. doi: 10.1067/mob.2003.183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Westgate J, Wibbens B, Bennet L, Wassink G, Parer J, Gunn A. The intrapartum deceleration in center stage: a physiologic approach to the interpretation of fetal heart rate changes in labor. Am J Obstet Gynaecol. 2007;197:236.e1–236.e11. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2007.03.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vijgen S, Westerhuis M, Opmeer B, Visser G, Moons K, Porath M, et al. Cost-effectiveness of cardiotocography plus ST analysis of the fetal electrocardiogram compared with cardiotocography only. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2011;90:772–778. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0412.2011.01138.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Madsen JT, Jansen P, Hesslinger C, Meyer M, Zimmer J, Gramsbergen JB. Tetrahydrobiopterin precursor sepiapterin provides protection against neurotoxicity of 1-methyl-4-phenylpyridinium in nigral slice cultures. J Neurochem. 2003;85:214–223. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2003.01666.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fabian RH, Perez-Polo J, Kent TA. Perivascular nitric oxide and superoxide in neonatal cerebral hypoxia-ischemia. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2010;295:h1809–h1814. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00301.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vásquez-Vivar J, Whitsett J, Derrick M, Ji X, Yu L, Tan S. Tetrahydrobiopterin in the prevention of hypertonia in hypoxic fetal brain. Ann Neurol. 2009;66:323–331. doi: 10.1002/ana.21738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kaufman S, Kapatos G, McInnes R, Schulman J, Rizzo W. Use of tetrahydropterins in the treatment of hyperphenylalaninemia due to defective synthesis of tetrahydrobiopterin: evidence that peripherally administered tetrahydropterins enter the brain. Pediatrics. 1982;70:376–380. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Frye R, Huffman L, Elliott GR. Tetrahydrobiopterin as a novel therapeutic intervention for autism. Neurotherapeutics. 2010;7:241–249. doi: 10.1016/j.nurt.2010.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Giżewska M, Hnatyszyn G, Sagan L, Cyryłowski L, Zekanowski C, Modrzejewska M, et al. Maternal tetrahydrobiopterin deficiency: the course of two pregnancies and follow-up of two children in a mother with 6-pyruvoyl-tetrahydropterin synthase deficiency. J Inherit Metab Dis. 2009 doi: 10.1007/s10545-009-1073-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Trefz FK, Scheible D, Frauendienst-Egger G. Long-term follow-up of patients with phenylketonuria receiving tetrahydrobiopterin treatment. J Inherit Metab Dis. 2010 doi: 10.1007/s10545-010-9058-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Endres W, Niederwieser A, Curtius H, Wang M, Ohrt B, Schaub J. Atypical phenylketonuria due to biopterin deficiency. Early treatment with tetrahydrobiopterin and neurotransmitter precursors, trials of monotherapy. Helv Paediatr Acta. 1982;37:489–498. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Koch R, Moseley K, Guttler F. Tetrahydrobiopterin and maternal PKU. Mol Genet Metab. 2005;86:S139–S141. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2005.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fink J, Ravin P, Argoff C, Levine R, Brady R, Hallett M, et al. Tetrahydrobiopterin administration in biopterin-deficient progressive dystonia with diurnal variation. Neurology. 1989;39:1393–1395. doi: 10.1212/wnl.39.10.1393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Segawa M, Nomura Y, Nishiyama N. Autosomal dominant guanosine triphosphate cyclohydrolase I deficiency (Segawa disease) Ann Neurol. 2003;54:S32–S45. doi: 10.1002/ana.10630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Altun A, Ugur-Altun B. Melatonin: therapeutic and clinical utilization. Int J Clin Pract. 2007;61:835–845. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-1241.2006.01191.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Boutin JA, Audinot V, Ferry G, Delagrange P. Molecular tools to study melatonin pathways and actions. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2005;26:412–419. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2005.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hardeland R. Antioxidative protection by melatonin: multiplicity of mechanisms from radical detoxification to radical avoidance. Endocrine. 2005;27:119–130. doi: 10.1385/endo:27:2:119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Luchetti F, Canonico B, Betti M, Arcangeletti M, Pilolli F, Piroddi M, et al. Melatonin signaling and cell protection function. FASAB J. 2010;24:3603–3624. doi: 10.1096/fj.10-154450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Okatani Y, Okamoto K, Hayashi K, Wakatsuki A, Tamura S, Sagara Y. Maternal-fetal transfer of melatonin in pregnant women near term. J Pineal Res. 1998;25:129–134. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-079x.1998.tb00550.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Reppert S, Chez R, Anderson A, Klein D. Maternal-fetal transfer of melatonin in the non-human primate. Pediatr Res. 1979;13:788–791. doi: 10.1203/00006450-197906000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sadowsky D, Yellon S, Mitchell M, Nathanielsz P. Lack of effect of melatonin on myometrial electromyographic activity in the pregnant sheep at 138–142 days gestation (term = 147 days gestation) Endocronology. 1991;128:1812–1818. doi: 10.1210/endo-128-4-1812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Vitte P, Harthe C, Lestage P, Claustrat B, Bobillier P. Plasma, cerebrospinal fluid, and brain distribution of 14C-melatonin in rat: a biochemical and autoradiographic study. J Pineal Res. 1988;5:437–453. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-079x.1988.tb00787.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mistraletti G, Sabbatini G, Taverna M, Figini MA, Umbrello M, Magni P, et al. Pharmacokinetics of orally administered melatonin in critically ill patients. J Pineal Res. 2010;48:142–147. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-079X.2009.00737.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Husson I, Mesplès B, Bac P, Vamecq J, Evrard P, Gressens P. Melatoninergic neuroprotection of the murine periventricular white matter against neonatal excitotoxic challenge. Ann Neurol. 2002;51:82–92. doi: 10.1002/ana.10072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jahnke G, Marr M, Myers C, Wilson R, Travlos G, Price C. Maternal and developmental toxicity evaluation of melatonin administered orally to pregnant Sprague-Dawley rats. Toxicol Sci. 1999;50:271–279. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/50.2.271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Robertson N, Powell E, Faulkner S, Bainbridge A, Chandrasekaran M, Hristova M, et al. Improved neuroprotection with melatonin-augmented hypothermia vs hypothermia alone in a perinatal asphysia model. EPAS. 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 42.Welin AK, Svedin P, Lapatto R, Sultan B, Hagberg H, Gressens P, et al. Melatonin reduces inflammation and cell death in white matter in the mid-gestation fetal sheep following umbilical cord occlusion. Pediatr Res. 2007;61:153–158. doi: 10.1203/01.pdr.0000252546.20451.1a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jan J, O’Donnell M. Use of melatonin in the treatment of paediatric sleep disorders. J Pineal Res. 1996;21:193–199. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-079x.1996.tb00286.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gitto E, Karbownik M, Reiter R, Tan D, Cuzzocrea S, Chiurazzi P, et al. Effects of melatonin treatment in septic newborns. Pediatr Res. 2001;50:756–760. doi: 10.1203/00006450-200112000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Reiter R, Tan D, Mayo J, Sainz R, Leon J, Czarnocki Z. Melatonin as an antioxidant: biochemical mechanisms and pathophysiological implications in humans. Acta Biochim Pol. 2003;50:1129–1146. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Miller SL, Yan EB, Castillo-Meléndez M, Jenkin G, Walker DW. Melatonin provides neuroprotection in the late-gestation fetal sheep brain in response to umbilical cord occlusion. Dev Neurosci. 2005;27:200–210. doi: 10.1159/000085993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hutton LC, Abbass M, Dickinson H, Ireland Z, Walker DW. Neuroprotective properties of melatonin in a model of birth asphyxia in the spiny mouse (Acomys cahirinus) Dev Neurosci. 2009;31:437–451. doi: 10.1159/000232562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Fulia F, Gitto E, Cuzzocrea S, Reiter R, Dugo L, Gitto P, et al. Increased levels of malondialdehyde and nitrite/nitrate in the blood of asphyxiated newborns: reduction by melatonin. J Pineal Res. 2005;31:343–349. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-079x.2001.310409.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bouslama M, Renaud J, Olivier P, Fontaine RH, Matrot B, Gressens P, et al. Melatonin prevents learning disorders in brain-lesioned newborn mice. Neuroscience. 2007;150:712–719. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2007.09.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kaur C, Sivakumar V, Ling E. Melatonin protects periventricular white matter from damage due to hypoxia. J Pineal Res. 2010;48:185–193. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-079X.2009.00740.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Olivier P, Fontaine RH, Loron G, Van Steenwinckel J, Biran V, Massonneau V, et al. Melatonin promotes oligodendroglial maturation of injured white matter in neonatal rats. PLoS One. 2009;22:e7128. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0007128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wang X, Svedin P, Nie C, Lapatto R, Zhu C, Gustavsson M, et al. N-acetylcysteine reduces lipopolysaccharide-sensitized hypoxic-ischemic brain injury. Ann Neurol. 2007;61:263–271. doi: 10.1002/ana.21066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bolanos J, Almeida A, Stewart V, Peuchen S, Land J, Clark J, et al. Nitric oxide-mediated mitochondrial damage in the brain: mechanisms and implications for neurodegenerative diseases. J Neurochem. 1997;68:2227–2240. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1997.68062227.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Chen J, Tu Y, Moon C, Matarazzo V, Palmer A, Ronnett G. The localization of neuronal nitric oxide synthase may influence its role in neuronal precursor proliferation and synaptic maintenance. Dev Biol. 2004;269:165–182. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2004.01.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Perlman J. Intervention strategies for neonatal hypoxic-ischemic cerebral injury. Clin Ther. 2006;28:1353–1365. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2006.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ashwal S, Tone B, Tian H, Cole D, Liwnicz B, Pearce W. Core and penumbral nitric oxide synthase activity during cerebral ischemia and reperfusion in the rat pup. Pediatr Res. 1999;46:390–400. doi: 10.1203/00006450-199910000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Castillo J, Rama R, Davalos A. Nitric oxide-related brain damage in acute ischemic stroke. Stroke. 2000;31:852–857. doi: 10.1161/01.str.31.4.852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Parikh N, Katsetos C, Ashraf Q, Haider S, Legido A, Delivoria-Papadopoulos M, et al. Hypoxia-induced caspase-3 activation and DNA fragmentation in cortical neurons of newborn piglets: role of nitric oxide. Neurochem Res. 2003;28:1351–1357. doi: 10.1023/a:1024992214886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Willmot M, Gibson C, Gray L, Murphy S, Bath P. Nitric oxide synthase inhibitors in experimental ischemic stroke and their effects on infarct size and cerebral blood flow: a systematic review. Free Radic Biol Med. 2005;39:412–425. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2005.03.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ji H, Li H, Martasek P, Roman L, Poulos T, Silverman R. Discovery of highly potent and selective inhibitors of neuronal nitric oxide synthase by fragment hopping. J Med Chem. 2009;52:779–797. doi: 10.1021/jm801220a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ji H, Stanton B, Igarashi J, Li H, Martasek P, Roman L, et al. Minimal pharmacophoric elements and fragment hopping, an approach directed at molecular diversity and isozyme selectivity. Design of selective neuronal nitric oxide synthase inhibitors. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:3900–3914. doi: 10.1021/ja0772041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Ji H, Tan S, Igarashi J, Li H, Derrick M, Martasek P, et al. Selective neuronal nitric oxide synthase inhibitors and the prevention of cerebral palsy. Ann Neurol. 2009;65:209–217. doi: 10.1002/ana.21555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Yu L, Derrick M, Ji H, Silverman R, Whitsett J, Vasquez-Vivar J, et al. Neuronal NOS inhibition prevents cerebral palsy following hypoxiaischemia in fetal rabbits: Comparison between JI-8 and 7-nitroindazole. Dev Neurosci. 2011;33:312–319. doi: 10.1159/000327244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.van den Tweel ER, Peeters-Scholte C, van Bel F, Heijnen CJ, Groenendaal F. Inhibition of nNOS and iNOS following hypoxiaischaemia improves long-term outcome but does not influence the inflammatory response in the neonatal rat brain. Dev Neurosci. 2002;24:389–395. doi: 10.1159/000069044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Adams J, Wu D, Bassuk J, Arias J, Lozano H, Kurlansky P, et al. Nitric oxide synthase isoform inhibition before whole body ischemia reperfusion in pigs: vital or protective? Resuscitation. 2007;74:516–525. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2007.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Nijboer CH, Kavelaars A, van Bel F, Heijnen CJ, Groenendaal F. Gender-dependent pathways of hypoxia-ischemia-induced cell death and neuroprotection in the immature P3 rat. Dev Neurosci. 2007;29:385–392. doi: 10.1159/000105479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Nijboer CH, Groenendaal F, Kavelaars A, Hagberg HH, van Bel F, Heijnen CJ. Gender-specific neuroprotection by 2-iminobiotin after hypoxia-ischemia in the neonatal rat via a nitric oxide independent pathway. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2007;27:282–292. doi: 10.1038/sj.jcbfm.9600342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Franks N, Dickinson R, de Sousa S, Hall A, Lieb W. How does xenon produce anaesthesia? Nature. 1998;26:324. doi: 10.1038/24525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Gruss M, Bushell TJ, Bright DP, Lieb WR, Mathie A, Franks NP. Two-pore-domain K+ channels are a novel target for the anesthetic gases xenon, nitrous oxide, and cyclopropane. Mol Pharmacol. 2004;65:443–452. doi: 10.1124/mol.65.2.443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Petzelt CP, Kodirov S, Taschenberger G, Kox WJ. Participation of the Ca(2+)-calmodulin-activated Kinase II in the control of metaphase-anaphase transition in human cells. Cell Biol Int. 2001;25:403–409. doi: 10.1006/cbir.2000.0646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Ma D, Williamson P, Januszewski A, Nogaro MC, Hossain M, Ong LP, et al. Xenon mitigates isoflurane-induced neuronal apoptosis in the developing rodent brain. Anaesthesiology. 2007;106:746–753. doi: 10.1097/01.anes.0000264762.48920.80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Ma D, Lim T, Xu J, Tang H, Wan Y, Zhao H, et al. Xenon preconditioning protects against renal ischemic-reperfusion injury via HIF-1alpha activation. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009;20:713–720. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2008070712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Steffenson J. Inhalation analgesia-nitrous oxide-methoxflurane. Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins; 1970. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Lane GA, Nahrwold ML, Tait AR, Taylor-Busch M, Cohen PJ, Beaudoin AR. Anesthetics as teratogens: nitrous oxide is fetotoxic, xenon is not. Science. 1980;210:899–901. doi: 10.1126/science.7434002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Istaphanous G, Loepke A. General anesthetics and the developing brain. Curr Opin Anaesthesiol. 2009;22:368–373. doi: 10.1097/aco.0b013e3283294c9e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Goto T, Saito H, Shinkai M, Nakata Y, Ichinose F, Morita S. Xenon provides faster emergence from anesthesia than does nitrous oxidesevoflurane or nitrous oxide-isoflurane. Anaesthesiology. 1997;86:1273–1278. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199706000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Ma D, Hossain M, Chow A, Arshad M, Battson R, Sanders R, et al. Xenon and hypothermia combine to provide neuroprotection from neonatal asphyxia. Ann Neurol. 2005;58:182–193. doi: 10.1002/ana.20547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Hobbs C, Thoresen M, Tucker A, Aquilina K, Chakkarapani E, Dingley J. Xenon and hypothermia combine additively, offering long-term functional and histopathologic neuroprotection after neonatal hypoxia/ischemia. Stroke. 2008;39:1307–1313. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.107.499822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Coburn M, Kunitz O, Baumert JH, Hecker K, Haaf S, Zühlsdorff A, et al. Randomized controlled trial of the haemodynamic and recovery effects of xenon or propofol anaesthesia. Br J Anaesth. 2005;94:198–202. doi: 10.1093/bja/aei023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Preckel B, Schlack W, Heibel T, Rütten H. Xenon produces minimal haemodynamic effects in rabbits with chronically compromised left ventricular function. Br J Anaesth. 2002;88:264–299. doi: 10.1093/bja/88.2.264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Greisen G, Pryds O. Intravenous 133Xe clearance in preterm neonates with respiratory distress. Internal validation of CBF infinity as a measure of global cerebral blood flow. Scand J Clin Lab Invest. 1988;48:673–678. doi: 10.1080/00365518809085789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Ma D, Hossain M, Pettet GK, Luo Y, Lim T, Akimov S, et al. Xenon preconditioning reduces brain damage from neonatal asphyxia in rats. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2006;26:199–208. doi: 10.1038/sj.jcbfm.9600184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Wilhelm S, Ma D, Maze M, Franks N. Effects of xenon on in vitro and in vivo models of neuronal injury. Anaesthesiology. 2002;96:1485–1491. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200206000-00031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Ma D, Hossain M, Rajakumaraswamy N, Franks NP, Maze M. Combination of xenon and isoflurane produces a synergistic protective effect against oxygen-glucose deprivation injury in a neuronal-glial co-culture model. Anaesthesiology. 2003;99:748–751. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200309000-00034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Dingley J, Tooley J, Porter H, Thoresen M. Xenon provides short-term neuroprotection in neonatal rats when administered after hypoxiaischemia. Stroke. 2006;37:501–506. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000198867.31134.ac. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Martin JL, Ma D, Hossain M, Xu J, Sanders RD, Franks NP, Maze M. Asynchronous administration of xenon and hypothermia significantly reduces brain infarction in the neonatal rat. Br J Anaesth. 2007;98:236–240. doi: 10.1093/bja/ael340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Thoresen M, Hobbs CEHC, Wood T, Chakkarapani E, Dingley J. Cooling combined with immediate or delayed xenon inhalation provides equivalent long-term neuroprotection after neonatal hypoxiaischemia. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2009;29:707–714. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2008.163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Faulkner S, Bainbridge A, Kato T, Chandrasekaran M, Hristova M, Liu M, et al. Xenon augmented hypothermia reduces early lactate/NAA and cell death in Perinatal Asphyxia. Ann Neurol. 2011;70:133–150. doi: 10.1002/ana.22387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Chakkarapani E, Dingley J, Liu X, Hoque N, Aquilina K, Porter H, et al. Xenon enhances hypothermic neuroprotection in asphyxiated newborn pigs. Ann Neurol. 2010;68:330–341. doi: 10.1002/ana.22016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Luo Y, Ma D, Leong E, Sanders R, Yu B, Hossain M, et al. Xenon and sevoflurane protect against brain injury in a neonatal asphyxia model. Aneasthesiology. 2008;109:782–789. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e3181895f88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Satomoto M, Satoh Y, Terui K, Miyao H, Takishima K, Ito M, et al. Neonatal exposure to sevoflurane induces abnormal social behaviors and deficits in fear conditioning in mice. Anesthesiology. 2009;110:628–637. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e3181974fa2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Dong Y, Zhang G, Zhang B, Moir R, Xia W, Marcantonio E, et al. The common inhalational anesthetic sevoflurane induces apoptosis and increases beta-amyloid protein levels. Arch Neurol. 2009;66:620–631. doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2009.48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Lu Y, Wu X, Dong Y, Xu Z, Zhang Y, Xie Z. Anesthetic sevoflurane causes neurotoxicity differently in neonatal naïve and Alzheimer disease transgenic mice. Anesthesiology. 2010;112:1404–1416. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e3181d94de1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Thoresen M, Liu X, Tooley J, Chakkarapani E, Dingley J. First human use of 50% xenon inhalation during hypothermia for neonatal hypoxicischemic encephalopathy: the “Coolxenon” Feasibility Study. EPAS20111660.7. [Google Scholar]

- 95.Torrance HL, Benders MJ, Derks JB, Rademaker CM, Bos AF, Van Den Berg P, et al. Maternal allopurinol during fetal hypoxia lowers cord blood levels of the brain injury marker S-100B. Pediatrics. 2009;124:350–357. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-2228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Kaandorp JJ, Benders MJ, Rademaker CM, Torrance HL, Oudijk MA, de Haan TR, et al. Antenatal allopurinol for reduction of birth asphyxia induced brain damage (ALLO-Trial); a randomized double blind placebo controlled multicenter study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2010;10:8. doi: 10.1186/1471-2393-10-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Palmer C, Towfighi J, Roberts RL, Heitjan DF. Allopurinol administered after inducing hypoxia-ischemia reduces brain injury in 7-day-old rats. Pediatr Res. 1993;33:405–411. doi: 10.1203/00006450-199304000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Williams GD, Palmer C, Heitjan DF, Smith MB. Allopurinol preserves cerebral energy metabolism during perinatal hypoxia-ischemia: a 31P NMR study in unanesthetized immature rats. Neurosci Lett. 1992;144:103–106. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(92)90726-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Johnson WD, Kayser KL, Brenowitz JB, Saedi SF. A randomized controlled trial of allopurinol in coronary bypass surgery. Am Heart J. 1991;121:20–24. doi: 10.1016/0002-8703(91)90950-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Clancy RR, McGaurn SA, Goin JE, Hirtz DG, Norwood WI, Gaynor JW, et al. Allopurinol neurocardiac protection trial in infants undergoing heart surgery using deep hypothermic circulatory arrest. Pediatrics. 2001;108:61–70. doi: 10.1542/peds.108.1.61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.van Kesteren C, Benders MJ, Groenendaal F, van Bel F, Ververs FF, Rademaker CM. Population pharmacokinetics of allopurinol in full-term neonates with perinatal asphyxia. Ther Drug Monit. 2006;28:339–344. doi: 10.1097/01.ftd.0000211808.74192.86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Chaudhari T, McGuire W. Allopurinol for preventing mortality and morbidity in newborn infants with suspected hypoxic-ischaemic encephalopathy. Cochrane Database Sys Rev. 2008;2:CD006817. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006817.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Benders MJ, Bos AF, Rademaker CM, Rijken M, Torrance HL, Groenendaal F, et al. Early postnatal allopurinol does not improve short term outcome after severe birth asphyxia. Arch Dis Child. 2006;91:F163–F165. doi: 10.1136/adc.2005.086652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Gunes T, Ozturk MA, Koklu E, Kose K, Gunes I. Effect of allopurinol supplementation on nitric oxide levels in asphyxiated newborns. Pediatr Neurol. 2007;36:17–24. doi: 10.1016/j.pediatrneurol.2006.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Van Bel F, Shadid M, Moison RM, Dorrepaal CA, Fontijn J, Monteiro L, et al. Effect of allopurinol on postasphyxial free radical formation, cerebral hemodynamics, and electrical brain activity. Pediatrics. 1998;101:185–193. doi: 10.1542/peds.101.2.185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Kaandorp J, van Bel F, Veen S, Derks J, Groenendaal F, Rijken M, et al. Long-term neuroprotective effects of allopurinol after moderate perinatal asphyxia. Follow-up of two randomised controlled trials. Arch Dis Child. 2011 doi: 10.1136/archdischild-2011-300356. In press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Jackson T, Xu A, Vita J, Keaney JJ. Ascorbate prevents the interaction of superoxide and nitric oxide only at very high physiological concentrations. Circ Res. 1998;83:916–922. doi: 10.1161/01.res.83.9.916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Rybakowski C, Mohar B, Wohlers S, Leichtweiss H, Schröder H. The transport of vitamin C in the isolated human near-term placenta. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 1995;62:107–114. doi: 10.1016/0301-2115(95)02117-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Huang J, Agus D, Winfree C, Kiss S, Mack W, McTaggart R, et al. Dehydroascorbic acid, a blood-brain barrier transportable form of vitamin C, mediates potent cerebroprotection in experimental stroke. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:11720–11724. doi: 10.1073/pnas.171325998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Covey M, Murphy M, Hobbs C, Smith R, Oorschot D. Effect of the mitochondrial antioxidant, Mito Vitamin E, on hypoxic-ischemic striatal injury in neonatal rats: a dose-response and stereological study. Exp Neurol. 2006;199:513–519. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2005.12.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Daneyemez M, Kurt E, Cosar A, Yuce E, Ide T. Methylprednisolone and vitamin E therapy in perinatal hypoxic-ischemic brain damage in rats. Neuroscience. 1999;92:693–697. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(99)00038-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Aly H, Abd-Rabboh L, El-Dib M, Nawwar F, Hassan H, Aaref M, et al. Ascorbic acid combined with ibuprofen in hypoxic ischemic encephalopathy: a randomized controlled trial. J Perinatol. 2009;29:438–443. doi: 10.1038/jp.2009.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Aruoma O, Halliwell B, Hoey B, Butler J. The antioxidant action of N-acetylcysteine: its reaction with hydrogen peroxide, hydroxyl radical, superoxide, and hypochlorous acid. Free Radic Biol Med. 1989;6:593–597. doi: 10.1016/0891-5849(89)90066-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Riggs B, Bronstein A, Kulig K, Archer P, Rumack B. Acute acetaminophen overdose during pregnancy. Obstet Gynaecol. 1989;74:247–253. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Xu D, Chen Y, Wang H, Zhao L, Wang J, Wei W. Effect of N-acetylcysteine on lipopolysaccharide-induced intra-uterine fetal death and intra-uterine growth retardation in mice. Toxicol Sci. 2005;88:525–533. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfi300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Probyn M, Cock M, Duncan J, Tolcos M, Hale N, Shields A, et al. The anti-inflammatory agent N-acetyl cysteine exacerbates endotoxin-induced hypoxemia and hypotension and induces polycythemia in the ovine fetus. Neonatology. 2010;98:118–127. doi: 10.1159/000280385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Heard K. Acetylcysteine for acetaminophen poisoning. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:285–292. doi: 10.1056/NEJMct0708278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Horowitz R, Dart R, Jarvie D, Bearer C, Gupta U. Placental transfer of N-acetylcysteine following human maternal acetaminophen toxicity. J Toxicol Clin Toxicol. 1997;35:447–451. doi: 10.3109/15563659709001226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Schaper M, Gergely S, Lykkesfeldt J, Zbären J, Leib S, Täuber M, et al. Cerebral vasculature is the major target of oxidative protein alterations in bacterial meningitis. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2002;61:605–613. doi: 10.1093/jnen/61.7.605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Paintlia MK, Paintlia AS, Barbosa E, Singh I, Singh AK. N-acetylcysteine prevents endotoxin-induced degeneration of oligodendrocyte progenitors and hypomyelination in developing rat brain. J Neurosci Res. 2004;78:347–361. doi: 10.1002/jnr.20261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Lanté F, Meunier J, Guiramand J, Maurice T, Cavalier M, de Jesus Ferreira M, et al. Neurodevelopmental damage after prenatal infection: role of oxidative stress in the fetal brain. Free Radic Biol Med. 2007;42:1231–1245. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2007.01.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Lanté F, Meunier J, Guiramand J, De Jesus Ferreira M, Cambonie G, Aimar R, et al. Late N-acetylcysteine treatment prevents the deficits induced in the offspring of dams exposed to an immune stress during gestation. Hippocampus. 2008;18:602–609. doi: 10.1002/hipo.20421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Plaisant F, Clippe A, Vander Stricht D, Knoops B, Gressens P. Recombinant peroxiredoxin 5 protects against excitotoxic brain lesions in newborn mice. Free Radic Biol Med. 2003;34:862–872. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(02)01440-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Liu J, Lee T, Chen C, Bagim D, Cheung P. N-acetylcysteine improves hemodynamics and reduces oxidative stress in the brains of newborn piglets with hypoxia-reoxygenation injury. J Neurotrauma. 2010;27:1865–1873. doi: 10.1089/neu.2010.1325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Lee T, Tymafichuk C, Bigam D, Cheung P. Effects of postresuscitation N-acetylcysteine on cerebral free radical production and perfusion during reoxygenation of hypoxic newborn piglets. Pediatr Res. 2008;64:256–261. doi: 10.1203/PDR.0b013e31817cfcc0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Jatana M, Singh I, Singh A, Jenkins D. Combination of systemic hypothermia and N-acetylcysteine attenuates hypoxic-ischemic brain injury in neonatal rats. Pediatr Res. 2006;59:684–689. doi: 10.1203/01.pdr.0000215045.91122.44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Morishita E, Masuda S, Nagao M, Yasuda Y, Sasaki R. Erythropoietin receptor is expressed in rat hippocampal and cerebral cortical neurons, and erythropoietin prevents in vitro glutamate-induced neuronal death. Neuroscience. 1997;76:105–116. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(96)00306-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Juul S, Anderson D, Li Y, Christensen R. Erythropoietin and erythropoietin receptor in the developing human central nervous system. Pediatr Res. 1998;43:40–49. doi: 10.1203/00006450-199801000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Digicaylioglu M, Lipton S. Erythropoietin-mediated neuroprotection involves cross-talk between Jak2 and NF-kappaB signalling cascades. Nature. 2001;412:641–647. doi: 10.1038/35088074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Byts N, Samoylenko A, Fasshauer T, Ivanisevic M, Hennighausen L, Ehrenreich H, et al. Essential role for Stat5 in the neurotrophic but not in the neuroprotective effect of erythropoietin. Cell Death Differ. 2008;15:783–792. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2008.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]