Abstract

Objectives

To assess patterns and functional consequences of mitral apparatus infarction after acute MI (AMI).

Background

The mitral apparatus contains two myocardial components – papillary muscles and the adjacent LV wall. Delayed-enhancement CMR (DE-CMR) enables in-vivo study of inter-relationships and potential contributions of LV wall and papillary muscle infarction (PMI) to mitral regurgitation (MR).

Methods

Multimodality imaging was performed: CMR was used to assess mitral geometry and infarct pattern, including 3D DE-CMR for PMI. Echocardiography (echo) was used to measure MR. Imaging occurred 27±8 days post-AMI (CMR, echo within 1 day).

Results

153 patients with first AMI were studied. PMI was present in 30% (n=46; 72% posteromedial, 39% anterolateral). When stratified by angiographic culprit vessel, PMI occurred in 65% of patients with left circumflex, 48% with right coronary, and only 14% of patients with left anterior descending infarctions (p<0.001). Patients with PMI had more advanced remodeling as measured by LV size and mitral annular diameter (p<0.05). Increased extent of PMI was accompanied by a stepwise increase in mean infarct transmurality within regional LV segments underlying each papillary muscle (p<0.001). Prevalence of lateral wall infarction was 3.0 fold higher among patients with, compared to those without, PMI (65% vs. 22%, p<0.001). Infarct distribution also impacted MR, with greater MR among patients with lateral wall infarction (p=0.002). Conversely, MR severity did not differ based on presence (p=0.19) or extent (p=0.12) of PMI, or by angiographic culprit vessel. In multivariable analysis, lateral wall infarct size (OR=1.20[CI=1.05–1.39], p=0.01) was independently associated with substantial (≥moderate) MR even after controlling for mitral annular (OR=1.22[1.04–1.43], p=0.01) and LV end-diastolic diameter (OR=1.11 [0.99–1.23], p=0.056).

Conclusions

PMI is common post-AMI, affecting nearly one-third of patients. PMI extent parallels adjacent LV wall injury, with lateral infarction – rather than PMI - associated with increased severity of post-AMI MR.

Introduction

Mitral regurgitation (MR) is a serious consequence of acute myocardial infarction (AMI) that confers risk for adverse outcomes, including heart failure and death.1–3 Despite advances in coronary reperfusion, MR remains common following AMI, occurring in up to 50% of patients.1, 4 MR can beget MR, as regurgitation itself contributes to chamber dilation, hypertrophy, and systolic dysfunction.5–7 This cascade can further distort both chamber and valve geometry, resulting in progressive MR. While mitral repair/replacement can effectively treat severe MR and medical therapies can prevent adverse remodeling, clinical outcomes can be compromised if therapy is delayed.8–11 Consistent with these clinical observations, animal studies have demonstrated that early treatment of even moderate MR can reduce left ventricular (LV) volumes, attenuate adverse remodeling, and prevent contractile dysfunction.6 Thus, identification of indices that predict development and progression of post-AMI MR is important for implementation of effective therapeutic interventions.

The mitral valve apparatus includes two myocardial components – papillary muscles and the adjacent LV wall.12 Both are believed to contribute to mitral valve integrity through direct contractile effects to maintain valve closure as well as secondary effects on valve geometry.12, 13 The link between papillary muscle infarction (PMI) and severe MR is well established in the context of papillary rupture.14–16 It is also possible that lesser degrees of papillary necrosis can produce lesser MR that increases with time. PMI can occur without rupture, a phenomenon originally reported in experimental as well as autopsy studies17–19 and recently shown in-vivo using delayed enhancement CMR (DE-CMR), which enables high resolution imaging of both PMI and LV wall infarcts in a manner that closely agrees with pathology-evidenced myocyte necrosis.20–22 PMI and LV infarct distribution have each been studied as isolated predictors of MR. However, results have varied,5, 23–26 possibly due to the fact that their inter-relationship and potential independent contributions to MR have not been examined.

This study examined patterns and consequences of mitral apparatus infarction following AMI. To this end, CMR was performed to assess cardiac function, geometry, and infarct pattern – including high resolution 3D DE-CMR for PMI. Transthoracic echocardiography (echo) was performed for dedicated assessment of MR. The aims were to determine (1) clinical and imaging predictors of post-AMI PMI, and (2) relative impact of PMI and adjacent LV wall infarction on early post-AMI MR.

Methods

Population

The population was comprised of consecutive patients with first ST elevation MI enrolled in a prospective registry of post-AMI remodeling (clinical trials # NCT00539045) between September 2006 – August 2011 at Weill Cornell Medical College. Patients with intrinsic mitral dysfunction (prolapse, rheumatic, prior surgery) were excluded. Imaging was performed within a pre-specified time limit of 6 weeks following AMI. All patients underwent CMR and echo within 1 day.

Comprehensive clinical data were collected, including cardiac risk factors, CAD history, NYHA functional class, and medication regimen. Coronary angiograms were reviewed for infarct location and coronary dominance. Cardiac enzymes (creatine phosphokinase, MB-fraction) were collected for serologic estimation of infarct size. The study was conducted in accordance with the Weill Cornell Institutional Review Board (IRB).

Image Acquisition

Cardiac Magnetic Resonance

CMR was performed using 1.5 Tesla scanners (General Electric, Waukesha WI). Exams consisted of two components - (1) cine-CMR for function/morphology and (2) DE-CMR for infarct quantification.

Cine-CMR was performed using a steady-state free precession pulse sequence. Short axis images were acquired contiguously from the level of the mitral valve annulus through the apex. Long axis images were acquired in standard two-, three- and four-chamber orientations.

DE-CMR was performed following intravenous gadolinium infusion (0.2 mmol/kg). In all patients, tailored PMI imaging was attempted using a 3-dimensional (3D) DE-CMR pulse sequence that provides high-resolution imaging (matrix size 256×256; typical in plane resolution 1.4×1.4mm, slice thickness 5mm) acquired during free-breathing via a navigator gating algorithm.27 When 3D DE-CMR was unsuccessful (16%), imaging was limited to breath-held 2D DE-CMR. For both 2D and 3D DE-CMR, inversion times were adjusted to null viable myocardium and contiguous short axis images were acquired throughout the LV.

Echocardiography

Transthoracic echo was performed by experienced sonographers using commercially available equipment (General Electric Vivid-7, Philips ie33) with phased array transducers.

Images were acquired using a pre-specified registry protocol, including dedicated MR assessment in accordance with American Society of Echocardiography consensus guidelines.28 Imaging was performed in parasternal, sub-costal, as well as apical 2-, 3-, and 4-chamber orientations. Color Doppler was used to assess presence and severity of MR based on jet area, depth, vena contracta, and directionality. Pulsed wave Doppler included assessment of MR duration and pulmonary vein flow profile. 2D imaging was used for related parameters, including mitral valve and annular morphology.

Image Interpretation

Cardiac Magnetic Resonance

DE-CMR was used to detect PMI. In accordance with established criteria,13 papillary muscles were defined as discrete myocardial structures within the LV cavity that were typically circular in cross-sectional shape and either anterolateral or posteromedial in location. PMI was deemed present if any papillary hyperenhancement was evident on DE-CMR short axis images. PMI was further categorized by location and extent - partial or complete, stratified using a threshold of >50% papillary myocardium (Figure 1).

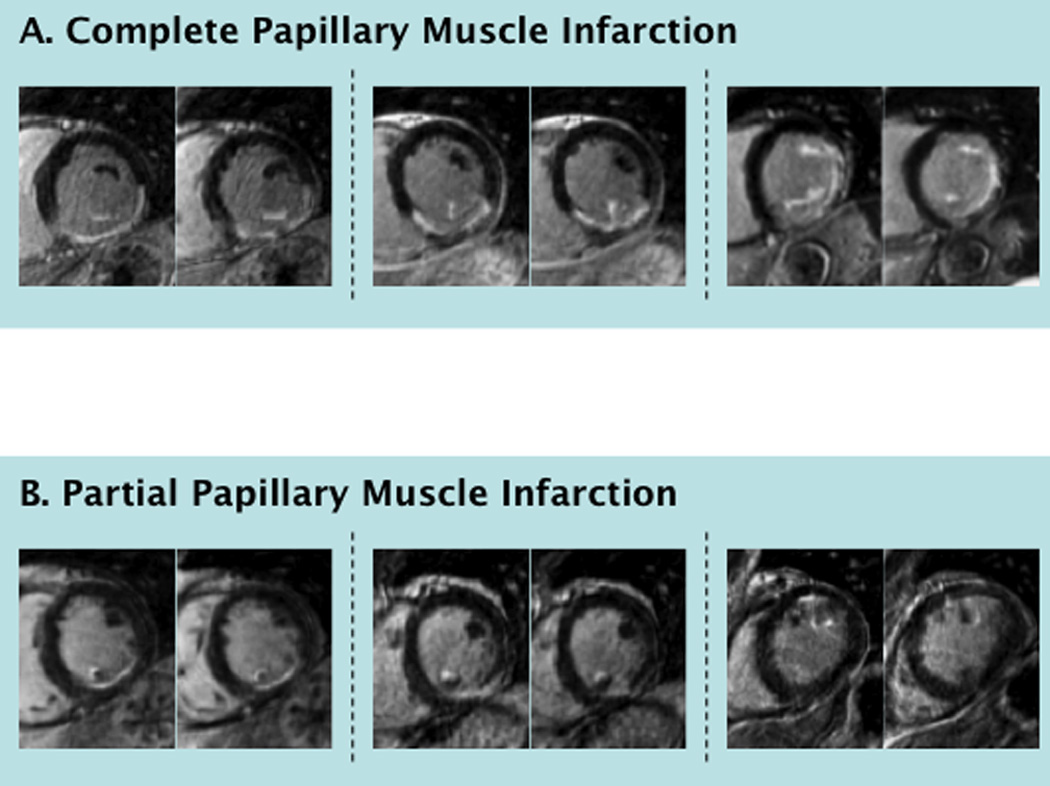

Figure 1. Representative Examples.

Typical examples of complete (1A) and partial (1B) PMI detected by DE-CMR (each example comprised of two short axis images within the affected papillary muscle). As shown, complete PMI was often associated with transmural infarction of the adjacent LV wall whereas partial PMI was associated with subendocardial infarction. Upper right shows bilateral, complete PMI with transmural infarction of the inferior and lateral walls.

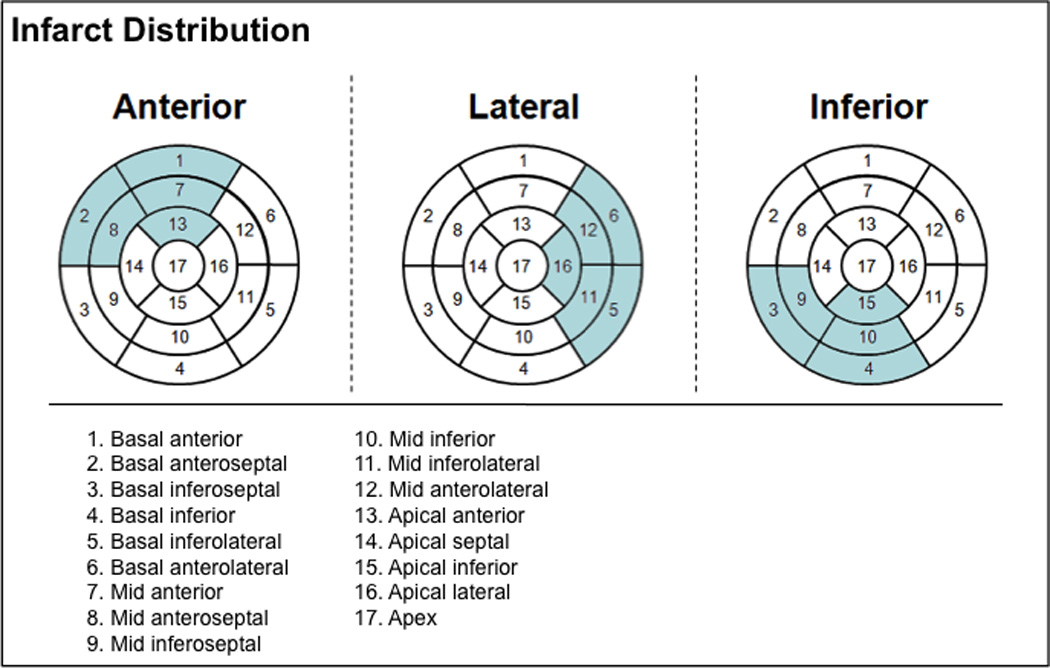

Global LV infarct size (% LV myocardium) was quantified on DE-CMR using the full-width at half-maximum method.22, 29 Reproducibility of infarct size quantification, as tested in a sub-group comprising 15% of the study population (n=23), yielded small intra- (Δ=0.2±1.5% LV myocardium [limits of agreement = −2.7, +3.1%]) and inter-observer differences (Δ=−0.6±1.3% LV myocardium [limits of agreement = −3.3, +2.0%]). LV infarct transmurality was scored using a 17-segment model/5 point per-segment scoring system (0=no hyperenhancement; 1=1–25%; 2=26–50%; 3=51–75%; 4=76–100%).30 Relative infarct burden within designated anterior, inferior, and lateral territories (Figure 2) was calculated as the proportion of segmental scores contained within each territory, multiplied by global LV infarct size.

Figure 2. Infarct Distribution.

Bullseye plots illustrating segments assigned to each regional infarct category (anterior = anterior/anteroseptal, lateral = anterolateral/inferolateral, inferior = inferior/inferoseptal, segments). Each category was comprised of five segments (highlighted in respective bullseye plots) such that total myocardium subtended by each was equivalent.

CMR was also analyzed for conventional indices of cardiac structure and function. LVEF and cavity volumes were based on end-diastolic and end-systolic endocardial contours of contiguous short-axis images, with end-diastolic diameter measured in short axis at mid-LV level. Regional LV contractile function was graded using a 17-segment/5-point scoring system (0=normal contraction; 1=mild hypokinesia; 2=moderate hypokinesia; 3=severe hypokinesia; 4=akinesia; 5=dyskinesia). Left atrial and mitral geometric indices were measured in accordance with established methodological conventions.26, 31 Left atrial area was planimetered in 4-chamber orientation, with volume calculated based on area and chamber length (8/3π*area2/length) from the posterior left atrium to the mitral annulus.31 Mitral indices were measured in 3-chamber orientation:26 Mitral annular diameter was measured in a linear plane extending from the respective junctions of anterior and posterior valve leaflets with the atrial wall. Coaptation depth was defined as the distance between leaflet coaptation and the mitral annulus. Tenting area encompassed the area enclosed between the annulus and the mitral valve leaflets. Atrial and mitral annular indices were measured during ventricular end-systole.

Echocardiography

Echo was the reference for MR, which was quantified based on regurgitant fraction (RF). RF was calculated based on differential stroke volume (SV) as calculated (VTI * πr2) using Doppler and 2D echo indices acquired at the mitral and aortic valve annuli (RF = [SVmitral − SVaorta]/SVmitral * 100%). Reproducibility of MR quantification based on regurgitant fraction,32, 33 as well as study center expertise for MR assessment,34–36 have been previously reported. MR severity was graded using established cutoffs in accordance with American Society of Echocardiography guidelines (mild [RF<30%] moderate [30–39%], moderate-severe [40–49%], severe [≥50%]).28

Each respective modality (CMR, echo) was interpreted by an experienced reader blinded to clinical data and other imaging tests.

Statistical Methods

Comparisons of continuous variables were made using Student’s t test (expressed as mean ± standard deviation) for two group comparisons, with adjunctive use of Levene’s Test to assess for approximate equality of variance between groups. ANOVA was used for multiple group comparisons. Categorical variables were compared using Pearson Chi-square or, when fewer than 5 expected outcomes were expected per cell, Fisher’s exact test. Ordinal variables were compared using Kruskal-Wallis one-way analysis or the Jonckheere-Tempestra test, with the latter used to test between-group differences in graded MR severity. Logistic regression was used to evaluate multivariable associations between imaging parameters and MR. Two-sided p<0.05 was considered indicative of statistical significance. Calculations were performed using SPSS 19.0 (SPSS, Chicago, IL).

Results

The population was comprised of 153 patients with AMI. CMR was performed 27±8 days post-AMI (90% > 14 days). Echo was performed within 1 day of CMR in all patients (95% within 4 hours).

PMI was present in 30% (n=46) of patients, among whom 72% had posteromedial, and 39% anterolateral papillary involvement. Concomitant involvement of both papillary muscles was present in 11% (5/46) of affected patients. Figure 1 provides representative examples of PMI identified by DE-CMR.

Table 1 details clinical and conventional imaging characteristics of the study population, with stratification based on presence or absence of PMI. Patients with PMI were clinically similar to those without PMI. Regarding imaging, results demonstrate that PMI was associated with more advanced remodeling based on LV chamber size and mitral annular diameter (p<0.05).

Table 1.

Clinical and Conventional Imaging Characteristics in Relation to PMI

| Parameter | Overall (n=153) |

PMI+ (46) |

PMI- (107) |

P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CLINICAL | ||||

| Age (year) | 57±12 | 60±13 | 56±12 | 0.06 |

| Male gender | 82% (126) | 89% (41) | 79% (85) | 0.15 |

| Atherosclerosis Risk Factors | ||||

| Hypertension | 46% (70) | 50% (23) | 44% (47) | 0.49 |

| Hypercholesterolemia | 46% (70) | 39% (18) | 49% (52) | 0.28 |

| Diabetes Mellitus | 25% (38) | 26% (12) | 24% (26) | 0.81 |

| Tobacco Use | 34% (52) | 30% (14) | 36% (38) | 0.54 |

| Family History | 26% (40) | 28% (13) | 25% (27) | 0.70 |

| Prior Coronary Artery Disease | ||||

| PCI | 5% (7) | 9% (4) | 3% (3) | 0.20 |

| CABG | 1% (1) | 2% (1) | 0% (0) | 0.30 |

| New York Heart Association Class (I/II/II/IV) | 82% (126) / 14% (22) / 3% (4) / 1% (1) | 78% (36) / 15% (7) / 4% (2) / 2% (1) | 84% (90) / 14% (15) / 2% (2) / 0% (−) | 0.34 |

| Cardiovascular Medications | ||||

| Beta-blocker | 97% (148) | 98% (45) | 96% (103) | 1.00 |

| HMG CoA-Reductase Inhibitor | 94% (144) | 96% (44) | 94% (100) | 0.73 |

| Loop diuretic | 5% (7) | 4% (2) | 5% (5) | 1.00 |

| Nitroglycerin | 7% (10) | 9% (4) | 6% (6) | 0.49 |

| Aspirin | 100% (153) | 100% (46) | 95% (107) | - |

| Thienopyridines | 95% (145) | 91% (42) | 96% (103) | 0.24 |

| MI Treatment Strategy | ||||

| Thrombolysis | 26% (39) | 26% (12) | 25% (27) | 0.91 |

| Percutaneous coronary intervention | 75% (114) | 74% (34) | 75% (80) | 0.91 |

| Cardiac Magnetic Resonance | ||||

| Left Ventricular Function/Geometry | ||||

| Ejection fraction (%) | 52.5 ± 11.9 | 52.3 ±1 1.8 | 52.6 ± 12.0 | 0.89 |

| Wall motion score | 0.8 ± 0.6 | 0.9 ± 0.6 | 0.8 ± 0.6 | 0.45 |

| End-diastolic diameter (cm) | 5.5 ± 0.5 | 5.7 ± 0.5 | 5.5 ± 0.5 | 0.02 |

| End-diastolic diameter (height adjusted) | 0.03 ± 0.003 | .033 ± 0.003 | 0.032 ± 0.003 | 0.04 |

| End-diastolic volume (ml) | 153.1 ± 42.4 | 163.4 ± 39.2 | 148.7 ± 43.2 | 0.049 |

| End-diastolic volume index (ml/m2) | 77.6 ± 19.0 | 81.4 ± 17.6 | 76.0 ± 19.4 | 0.11 |

| End-systolic volume (ml) | 75.5 ± 37.4 | 80.8 ± 37.2 | 73.2 ± 37.4 | 0.25 |

| End-systolic volume index (ml/m2) | 38.3 ± 18.4 | 40.3 ± 18.3 | 37.4 ± 18.5 | 0.38 |

| Myocardial mass (gm) | 131.1 ± 32.3 | 136.7 ± 33.5 | 128.8 ± 31.6 | 0.17 |

| Myocardial mass index (gm/m2) | 66.4 ± 14.2 | 67.8 ± 14.7 | 65.8 ± 14.0 | 0.42 |

| Left Atrial Geometry | ||||

| Left atrial diameter (cm) | 3.6 ± 0.5 | 3.6 ± 0.6 | 3.6 ± 0.5 | 0.91 |

| Left atrial area (cm2) | 22.1 ± 4.9 | 22.2 ± 5.4 | 22.0 ± 4.7 | 0.87 |

| Left atrial volume (ml) | 79.2 ± 27.6 | 79.6 ± 31.2 | 79.0 ± 26.0 | 0.90 |

| Left atrial volume index (ml/m2) | 40.4 ± 14.0 | 39.7 ± 15.0 | 40.7 ± 13.6 | 0.67 |

| Mitral Annular Geometry | ||||

| Annulus diameter (cm) | 2.8 ± 0.4 | 2.9 ± 0.4 | 2.8 ± 0.4 | 0.046 |

| Coaptation height (cm) | 0.6 ± 0.2 | 0.6 ± 0.2 | 0.6 ± 0.2 | 0.82 |

| Tenting area (cm2) | 0.9 ± 0.4 | 0.9 ±0.4 | 0.9 ± 0.4 | 0.64 |

Boldface indicates p values < 0.05

Infarct Parameters

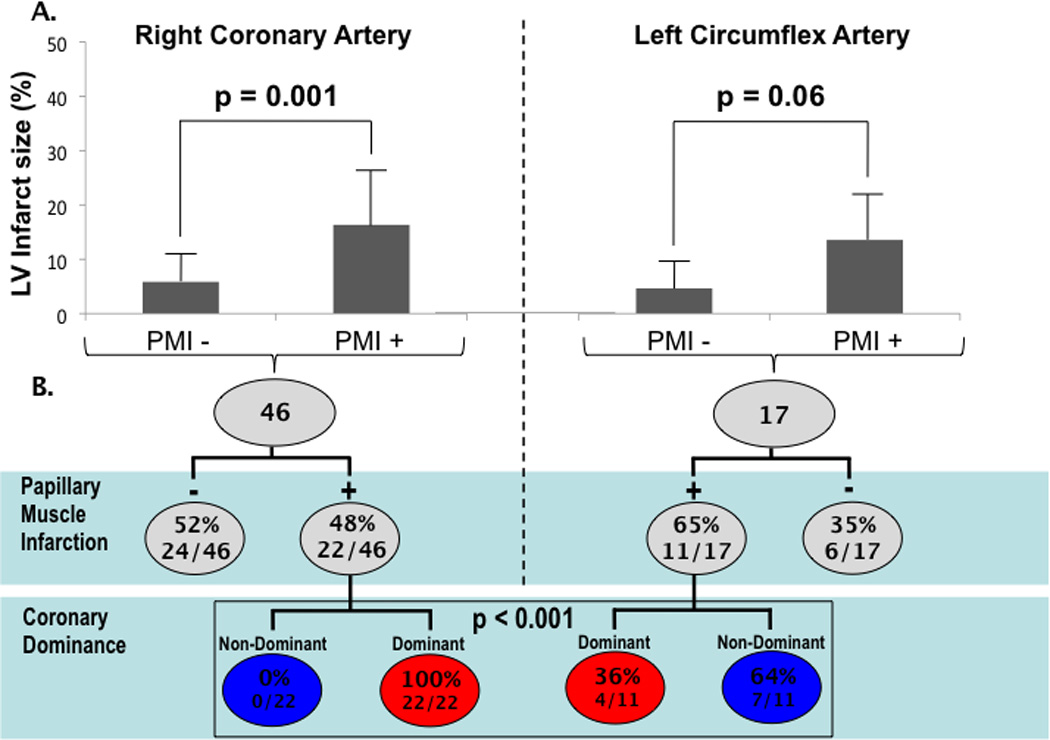

Among the total of 46 patients with PMI, nearly half (48%) occurred in the context of RCA culprit-vessel infarction, with the remainder near evenly divided between LAD (28%) and LCx (24%) involvement. When stratified by culprit vessel, PMI occurred in 65% (11/17) of patients with LCx, 48% (22/46) of patients with RCA, and only 14% (13/90) of patients with LAD infarcts (p<0.001).

Table 2 examines infarct-related parameters in relation to PMI. As shown, patients with PMI were more likely to have angiography-evidenced LCx (24% vs. 6%, p=0.001) or RCA (48% vs. 22%, p=0.002) culprit vessel involvement than those without PMI. Regarding infarct distribution on DE-CMR, prevalence of lateral wall infarction was 3.0 fold higher among patients with, compared to those without, PMI (65% vs. 22%, p<0.001). Prevalence of inferior wall infarction was 1.6 fold higher among patients with, compared to those without, PMI (72% vs. 45%, p=0.003).

Table 2.

Infarct Size and Distribution

| PMI | Posteromedial PMI | Anterolateral PMI | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Present (n=46) |

Absent (n=107) |

P | Present (n=33)† |

Absent (n=120) |

P | Present (n=18)† |

Absent (n=135) |

P | |

| INFARCT SIZE | |||||||||

| DE-CMR | |||||||||

| % LV hyperenhancement | 16.0 ± 10.9 | 12.3 ± 8.9 | 0.03 | 15.4 ± 10.8 | 12.9 ± 9.2 | 0.19 | 20.2 ± 13.3 | 12.5 ± 8.7 | 0.03 |

| Cardiovascular Enzymes | |||||||||

| Creatine phosphokinase | 2590±2344 | 2164±1836 | 0.25 | 2351±1782 | 2271 ±2057 | 0.85 | 2962±3118 | 2201 ± 1794 | 0.36 |

| Creatine phosphokinase-MB | 243±207 | 199±188 | 0.30 | 256±206 | 199±189 | 0.21 | 191 ± 200 | 216 ± 195 | 0.70 |

| Duration of Symptoms | |||||||||

| Chest pain interval (hours) | 12.4±9.4 | 10.2±8.4 | 0.17 | 12.4±9.6 | 10.4±8.5 | 0.29 | 13.7±9.6 | 10.5±8.6 | 0.15 |

| INFARCT DISTRIBUTION | |||||||||

| DE-CMR | |||||||||

| Anterior wall | 35% (16) | 70% (75) | <0.001 | 12% (4) | 73% (87) | <0.001 | 78% (14) | 57% (77) | 0.09 |

| Lateral wall | 65% (30) | 22% (23) | <0.001 | 73% (24) | 24% (29) | <0.001 | 61% (11) | 31% (42) | 0.01 |

| Inferior wall | 72% (33) | 45% (48) | 0.003 | 91% (30) | 43% (51) | <0.001 | 44% (8) | 54% (73) | 0.44 |

| Anterior + Inferior Wall | 15% (7) | 20% (21) | 0.52 | 12% (4) | 20% (24) | 0.30 | 28% (5) | 17% (23) | 0.33 |

| Lateral + Anterior Wall | 17% (8) | 12% (13) | 0.39 | 6% (2) | 16% (19) | 0.25 | 44% (8) | 10% (13) | 0.001 |

| Lateral + Inferior Wall | 50% (23) | 11% (12) | < 0.001 | 64% (21) | 12% (14) | <0.001 | 39% (7) | 21% (28) | 0.13 |

| Lateral + Anterior + Inferior Wall | 9% (4) | 4% (4) | 0.24 | 6% (2) | 5% (6) | 0.68 | 22% (4) | 3% (4) | 0.007 |

| Angiography (infarct-related artery) | |||||||||

| Left Anterior Descending | 28% (13) | 72% (77) | <0.001 | 0% (0) | 75% (90) | <0.001 | 72% (13) | 57% (77) | 0.22 |

| Left Circumflex | 24% (11) | 6% (6) | 0.001 | 33% (11) | 5% (6) | <0.001 | 22% (4) | 10% (3) | 0.12 |

| Right Coronary | 48% (22) | 22% (24) | 0.002 | 67% (22) | 20% (24) | <0.001 | 6% (1) | 33% (45) | 0.02 |

| Anatomically dominant artery* | 57% (26) | 26% (28) | <0.001 | 79% (26) | 23% (28) | <0.001 | 6% (1) | 39% (53) | 0.005 |

Either left circumflex or right coronary artery

5 subjects had concomitant posteromedial and anterolateral PMI

Regarding infarct size, Table 2 demonstrates that overall % LV infarction by DE-CMR was larger among patients with PMI (p=0.03), with parallel albeit non-significant relationships between PMI and the enzymatic and clinical indices of peak CPK and chest pain duration (both p=NS). However, the relation between PMI and infarct size varied according to culprit vessel involvement. Among patients with left anterior descending (LAD) infarcts, LV infarct size (% myocardium) was similar between patients with and without PMI (18±11% vs. 15±9%, p=0.32). In contradistinction, Figure 3A illustrates that among patients with either RCA or LCX culprit involvement, PMI was accompanied by over a 2-fold increase in LV infarct size (p=0.001, p=0.056 respectively).

Figure 3. Infarct Size and Coronary Anatomy.

(3A) Infarct size (mean±SD) stratified by PMI among patients with RCA and LCX culprit vessels. (3B) Stratification of RCA and LCX infarcts by presence of PMI (upper row) and coronary dominance pattern (lower row).

While both RCA and LCX infarction increased relative likelihood for PMI, the impact of coronary dominance varied by culprit vessel. Figure 3B first stratifies both RCA and LCX infarcts based on PMI and then stratifies patients with PMI by coronary dominance; among patients with RCA infarcts, PMI exclusively occurred (100%) in the setting of right or co-dominant coronary anatomy, whereas less than half (36%) of patients with PMI and LCX infarcts were left or co-dominant (p<0.0001). All RCA infarcts with PMI had posteromedial involvement (n=22); 50% (11/22) had infarcts of the adjacent mid inferolateral wall.

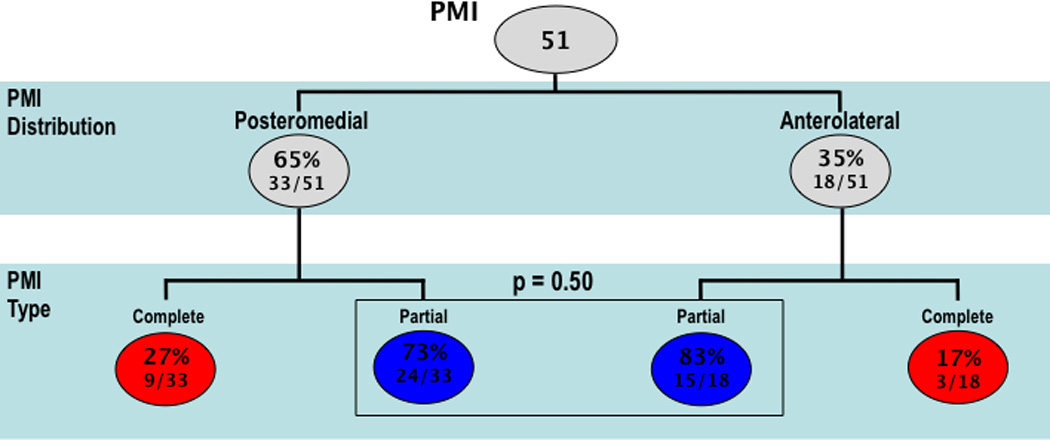

PMI Extent and LV Infarct Transmurality

In over three-fourths of cases (76%), PMI was partial, as defined by ≤50% papillary hyperenhancement. Figure 4 compares PMI type by anatomic distribution, demonstrating that PMI type (partial vs. complete) did not differ between the anterolateral and posteromedial papillary muscles (p=0.50).

Figure 4. PMI Location and Type.

Stratification of PMI by location (upper row) and type (lower row). Analysis based on total PMI (n=51) among 46 patients (n=5 with bilateral PMI).

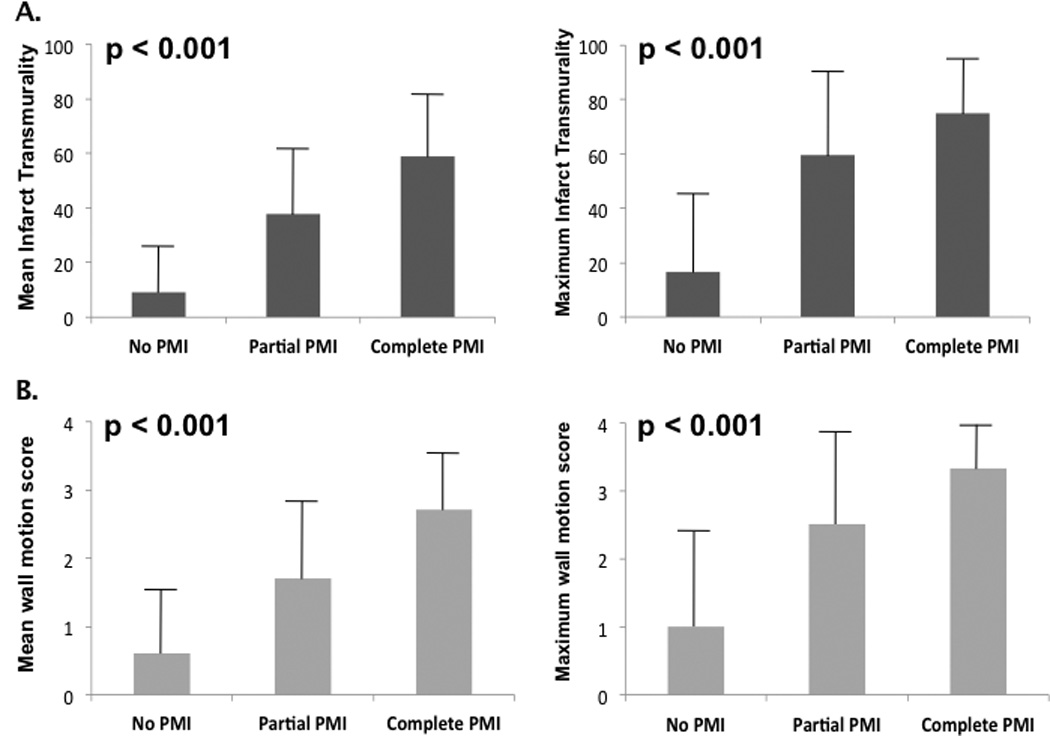

Figure 5 relates PMI type to both infarct transmurality and severity of contractile dysfunction in the adjoining LV wall. As shown (5A), increased extent of PMI was accompanied by a stepwise increase in mean infarct transmurality within adjacent LV segments underlying each papillary muscle (p<0.001). Similar results were obtained (5B) when contractile dysfunction (segmental wall motion score) was used as a surrogate marker for injury (p<0.001).

Figure 5. PMI in Relation to Left Ventricular Injury.

Infarct transmurality (5A) and contractile dysfunction (5B) stratified by PMI. Bar graphs based on mean (left) and maximum (right) infarct scores in LV segments adjacent to each papillary muscle (posteromedial = mid inferior/inferolateral, anterolateral = mid anterior/anterolateral walls). Note parallels between PMI extent and severity of injury to adjacent LV segments, whether assessed by infarct transmurality (5A) or contractile dysfunction (5B) (all p<0.001 for trend).

Mitral Regurgitation

Among the total study population, echo-evidenced MR was mild or less in most cases, with greater severity present in 14% (n=22) of patients (moderate; n=7 | moderate-severe; n=12 | severe; n=3). Table 3 reports univariate analyses examining CMR, biomarker, and x-ray angiography parameters in relation to presence or absence of substantial (≥moderate) MR. As shown, patients with ≥moderate MR had worse LV dysfunction and more advanced LV, LA, and mitral annular remodeling (p≤0.001) than those with lesser or absent MR. Regarding infarct pattern, Table 3 also demonstrates that patients with ≤moderate MR had greater prevalence of lateral wall infarction on DE-CMR (p<0.001), with non-significant differences in infarct-related artery distribution potentially attributable to variability in lateral wall coronary vascular supply. Among patients with infarcts that encompassed more than one LV region, only the combination of lateral + anterior wall infarction was more common among patients with increased MR, consistent with the fact that patients with ≥moderate MR had larger overall LV infarct size (both p<0.01). In multivariable analysis, MR was independently associated with presence of lateral wall infarction (OR 3.86 [CI 1.40–10.69], p=0.009) even after controlling for overall LV infarct size (OR 1.07/% LV hyperenhancement [CI 1.02–1.12], p=0.01).

Table 3.

Cardiac Structure, Function, and Infarct Pattern in Relation to Mitral Regurgitation*

| Parameter | MR + (n=22) |

MR – (n=131) |

P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mitral Annular Geometry | |||

| Annulus diameter (cm) | 3.1 ± 0.4 | 2.8 ± 0.4 | < 0.001 |

| Coaptation height (cm) | 0.7 ± 0.2 | 0.6 ± 0.2 | 0.001 |

| Tenting area (cm2) | 1.2 ± 0.5 | 0.8 ± 0.3 | <0.001 |

| Left Atrial Geometry | |||

| Left atrial diameter (cm) | 4.2 ± 0.6 | 3.6 ± 0.5 | <0.001 |

| Left atrial area (cm2) | 25.7 ± 5.7 | 21.6 ± 4.5 | < 0.001 |

| Left atrial volume (ml) | 98.8 ± 33.7 | 75.9 ± 25.1 | <0.001 |

| Left atrial volume index (ml/m2) | 49.6 ± 16.5 | 38.9 ± 13.0 | 0.001 |

| Left Ventricular Function/Geometry | |||

| Ejection fraction (%) | 42.7 ± 12.2 | 54.2 ± 11.0 | < 0.001 |

| Wall motion score | 1.4 ± 0.8 | 0.7 ± 0.5 | < 0.001 |

| End-diastolic diameter (cm) | 6.0 ± 0.6 | 5.5 ± 0.7 | < 0.001 |

| End-diastolic volume (ml) | 191.9 ± 46.7 | 146.6 ± 38.1 | < 0.001 |

| End-diastolic volume index (ml/m2) | 97.1 ± 25.7 | 74.3 ± 15.4 | < 0.001 |

| End-systolic volume (ml) | 113.8 ± 50.6 | 69.1 ± 30.5 | 0.001 |

| End-systolic volume index (ml/m2) | 57.8 ± 27.2 | 35.0 ± 14.2 | 0.001 |

| Myocardial mass (gm) | 140.1 ± 32.6 | 129.6 ± 32.0 | 0.16 |

| Myocardial mass index (gm/m2) | 71.1 ± 18.4 | 65.7 ± 13.3 | 0.096 |

| Left Ventricular Infarct Pattern | |||

| Infarct Size | |||

| % LV hyperenhancement | 20.3 ± 12.8 | 12.3 ± 8.6 | 0.009 |

| Creatine phosphokinase | 2730 ± 2009 | 2215 ± 1995 | 0.29 |

| Creatine phosphokinase-MB | 270 ± 180 | 205 ± 196 | 0.28 |

| Infarct Distribution (DE-CMR) | |||

| Anterior Wall | 64% (14) | 59% (77) | 0.67 |

| Lateral Wall | 68% (15) | 29% (38) | < 0.001 |

| Inferior Wall | 59% (13) | 52% (68) | 0.53 |

| Anterior + Inferior Wall | 27% (6) | 17% (22) | 0.24 |

| Lateral + Anterior Wall | 41% (9) | 9% (12) | 0.001 |

| Lateral + Inferior Wall | 36% (8) | 21% (27) | 0.10 |

| Lateral + Anterior + Inferior Wall | 14% (3) | 4% (5) | 0.09 |

| PMI (DE-CMR) | 41% (9) | 28% (37) | 0.23 |

| Infarct-Related Artery (x-ray angiography) | |||

| Left Anterior Descending | 55% (12) | 60% (78) | 0.66 |

| Left Circumflex | 18% (4) | 10% (13) | 0.21 |

| Right Coronary | 27% (6) | 31% (40) | 0.76 |

stratified based on ≥moderate mitral regurgitation threshold

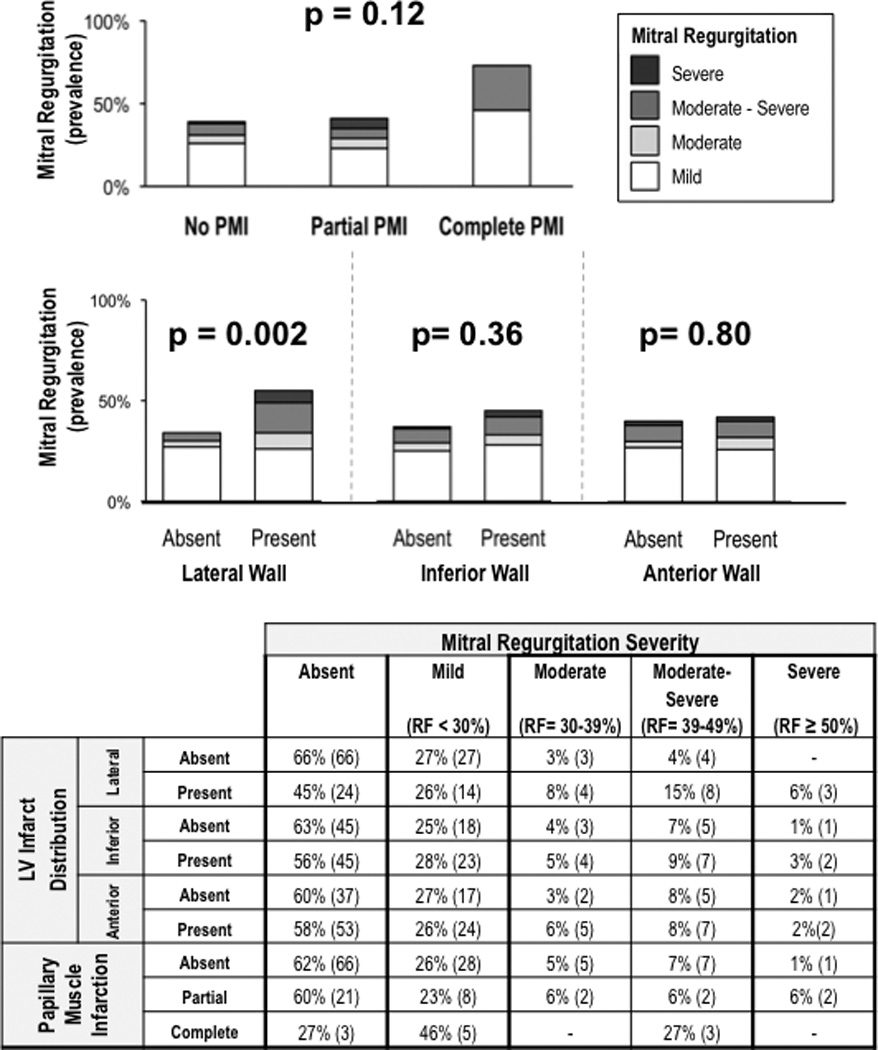

Figure 6 stratifies graded MR severity based on PMI extent and LV infarct distribution on DE-CMR – corresponding data is detailed in tabular form below each bar graph. PMI, categorized by extent of papillary muscle necrosis (p=0.12) or by binary presence/absence (p=0.19), was not associated with increased MR severity. However, LV infarct distribution did impact MR, as evidenced by increased MR severity in association with presence of lateral wall infarction (p=0.002). Of note, lateral wall infarct size was over three-fold larger among patients (n=5) with concomitant anterolateral and posteromedial PMI compared to those with absent or isolated PMI (p<0.001), paralleling a trend towards increased MR severity (p=0.09) in this group.

Figure 6. Mitral Regurgitation Severity.

Graded severity of echo-quantified MR stratified by PMI (top) and LV infarct distribution (bottom). Corresponding table provides a breakdown of MR severity in relation to PMI and LV infarction.

Logistic regression analysis was also used to test the association of infarct distribution with MR after controlling for conventional structural indices. In univariate analysis, presence of lateral wall infarction (OR 1.21 [CI 1.08–1.37], p=0.001) was significantly associated with substantial (≥moderate) MR, whereas PMI was not (OR 1.76 [CI 0.69–4.46], p=0.24). Multivariate modeling was used to test the independent association of lateral wall infarction with MR after controlling for conventional geometric indices of mitral annular and LV size. As shown in Table 4A, lateral wall infarct size (OR 1.20 per % LV myocardium [CI=1.05–1.39], p=0.01) and mitral annular diameter (OR 1.22 per mm [CI=1.05–1.45], p=0.009) were independently associated with MR, with a similar trend for LV chamber diameter (OR 1.11 per mm [CI=0.99–1.23], p=0.056). Substitution of lateral wall motion score (OR 1.25, CI 1.08–1.45, p=0.003) in the model (4B) also demonstrated an independent association between lateral wall dysfunction and MR. In contradistinction, use of angiography data did not demonstrate an independent association for LCX (4C) culprit involvement. Similar results were obtained when RCA (OR 0.68 [CI=0.21–2.18], p=0.52) or LAD (OR 0.90 [CI=0.32–2.51], p=0.83) culprit involvement was substituted in the model, consistent with overlap in coronary vascular supply to the lateral wall.

Table 4.

Structural Correlates of Mitral Regurgitation

| 4A. Lateral Wall Infarction | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Univariate Regression | Multivariate Regression Model χ2 = 29.37, p<0.001 |

|||

| Variable | Odds Ratio (95% Confidence Interval) |

P | Odds Ratio (95% Confidence Interval) |

P |

| Lateral Wall Infarct Size (% myocardium) | 1.21 (1.08 – 1.37) | 0.001 | 1.20 (1.05 – 1.39) | 0.01 |

| Mitral Annular Diameter (mm) | 1.29 (1.13 – 1.48) | <0.001 | 1.22 (1.05 – 1.45) | 0.009 |

| LV End Diastolic Diameter (mm) | 1.20 (1.09 – 1.33) | <0.001 | 1.11 (0.99 – 1.23) | 0.056 |

| PMI (complete or partial) | 1.76 (0.69 – 4.46) | 0.24 | ||

| Complete PMI | 2.43 (0.59 – 9.97) | 0.22 | ||

| Partial PMI | 1.57 (0.59 – 4.21) | 0.37 | ||

| 4B. Lateral Wall Contractility | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Univariate Regression | Multivariate Regression Model χ2 = 32.23, p<0.001 |

|||

| Variable | Odds Ratio (95% Confidence Interval) |

P | Odds Ratio (95% Confidence Interval) |

P |

| Lateral Wall Contractile Dysfunction (wall motion score) | 1.27 (1.13 – 1.43) | <0.001 | 1.25 (1.08 – 1.45) | 0.003 |

| Mitral Annular Diameter (mm) | 1.29 (1.13 – 1.48) | <0.001 | 1.24 (1.05 – 1.45) | 0.009 |

| LV End Diastolic Diameter (mm) | 1.20 (1.09 – 1.33) | <0.001 | 1.07 (0.95 – 1.21) | 0.25 |

| 4C. Infarct Related Artery | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Univariate Regression | Multivariate Regression Model χ2 = 23.99, p<0.001 |

|||

| Variable | Odds Ratio (95% Confidence Interval) |

P | Odds Ratio (95% Confidence Interval) |

P |

| Center Circumflex Infarction | 2.02 (0.59 – 6.87) | 0.26 | 2.26 (0.59 – 8.72) | 0.24 |

| Mitral Annular Diameter (mm) | 1.29 (1.13 – 1.48) | <0.001 | 1.20 (1.03 – 1.39) | 0.02 |

| LV End Diastolic Diameter (mm) | 1.20 (1.09 – 1.33) | <0.001 | 1.14 (1.03 – 1.27) | 0.01 |

Discussion

This study provides new insights regarding prevalence and physiologic consequences of infarction within two components of the mitral valve apparatus – papillary muscles and the adjacent LV wall. Key findings are as follows: 1) PMI is common in the current era, affecting nearly one-third (30%) of patients, with relative likelihood greater in the context of LCX or dominant RCA infarcts. 2) PMI typically occurs in the context of increased LV infarct size, as evidenced by over a 2-fold increase in infarct size among affected patients with LCX or RCA infarcts. 3) Lateral wall infarction, rather than presence or extent of PMI, is associated with increased MR as measured early post-AMI. In multivariate analysis, post-AMI MR is associated with lateral wall infarct size even after controlling for both mitral annular and LV chamber dilation.

Our findings provide new insight into the relation between PMI and MR. While prior studies have reported similar PMI prevalence, results have been discordant regarding PMI as a cause of MR. For example, whereas Tanimoto et al found no association between PMI and MR, Okayama et al reported that the two were linked.25, 26 Interestingly, in the latter study, infarction of both papillary muscles was associated with increased MR whereas single PMI was not. Our results suggest that LV infarct pattern may explain these variable findings. Among our population, only lateral wall infarction was associated with increased MR, and the association between lateral wall infarct size and MR remained significant even after controlling for PMI as well as conventional indices of LV and mitral geometry. PMI varied in both distribution and extent, with greater magnitude of papillary necrosis associated with increased infarct transmurality within the adjacent LV wall, suggesting that prior reported associations between bilateral PMI and MR may be attributable to increased lateral wall infarct size. Consistent with our results, an association between lateral wall infarction and MR was reported among patients with advanced LV dysfunction (LVEF<40%),23 although this prior study did not assess PMI, raising questions as to underlying reasons for MR. To the best of our knowledge, no prior study has examined the inter-relationship of PMI and LV infarct distribution on post-AMI MR.

Our finding that PMI has a negligible impact on MR is consistent with prior animal studies that have examined papillary physiology. Using a canine model in which coronary flow was reduced in a graded fashion, Matsuzaki et al found that papillary dysfunction alone was insufficient to cause MR, which was instead associated with LV free (lateral) wall hypokinesis and chamber dilation.37 The importance of lateral wall dysfunction was also demonstrated by Messas et al, who performed targeted LCX occlusion in a sheep model and found that LV infero-basal ischemia produced MR, whereas the addition of papillary ischemia paradoxically decreased MR by reducing leaflet tethering and improving valve coaptation.38 Regarding mitral geometry, animal studies by Kaul et al found that MR was associated with incomplete mitral valve closure rather than papillary ischemia.39 Clinical studies have also supported this concept: Uemura et al, studying 40 patients with prior MI, reported that papillary contractile dysfunction was associated with induction of leaflet tethering and MR attenuation,40 consistent with our multivariable analysis demonstrating that extent of PMI was not associated with increased MR. Taken together, these prior data support our observation that lateral wall injury and impaired valve coaptation, rather than papillary dysfunction, are key determinants of post-AMI MR.

It is important to recognize that animal studies that have assessed LV injury patterns in-vivo have typically relied on LV or papillary contractile dysfunction as surrogates for infarction,37–39 with questions remaining as to the direct impact of myocyte necrosis on mitral valve function. Other studies, which have assessed infarct size directly, have demonstrated the importance of lateral wall infarction using post-mortem analysis, raising uncertainty as to the impact of intrinsic differences between in-vivo assessment of mitral geometry/MR and ex-vivo infarct quantification.18, 41 To address these issues in a clinical setting, our study employed multimodality imaging for in-vivo assessment of infarct size, mitral valve geometry, and MR. CMR and echo were acquired using a tailored imaging protocol, with both tests performed within a 1 day interval. Results, obtained in a broad cohort of post-AMI patients, offer clinical evidence that both impaired mitral valve geometry (annular diameter) and lateral wall infarct size (% hyperenhancement) are independently associated with post-AMI MR, with a lesser, albeit significant, magnitude of association for LV chamber geometry as measured by end-diastolic diameter.

As DE-CMR provides a highly sensitive tool for assessment of infarct morphology, an additional study goal was to examine the relationship between infarct burden within the papillary muscles and adjacent LV wall. Prior DE-CMR studies, which have also reported increased prevalence of PMI in association with RCA and LCX culprit vessel involvement, have categorized PMI and LV infarct distribution in a binary fashion.25, 26 Our study examined graded extent of both papillary and LV wall infarction. Results demonstrate that papillary necrosis occurs in parallel with infarction of the adjacent LV wall, as evidenced by increased LV infarct size in association with greater extent of PMI. Rather than the notion of papillary muscles as end-organ structures particularly susceptible to jeopardized arterial supply, our results support the concept that papillary muscles and LV myocardium are similarly vulnerable to impaired perfusion. Taken together with our findings linking lateral wall infarct size to MR, these data emphasize the importance of prompt coronary reperfusion towards the common goals of preserving LV viability, preventing adverse remodeling, and minimizing MR after AMI.

In addition to CMR and echo, our study included analysis of x-ray angiography for assessment of mitral apparatus perfusion patterns. Results demonstrated that right and left coronary dominance bore a variable impact on PMI. Among patients with RCA infarcts, all with PMI were right (or co-) dominant whereas for patients with LCX infarcts, less than half (36%) with PMI were left (or co-) dominant (p<0.001). Additionally, we observed a near two-fold higher prevalence of posteromedial (72%) compared to anterolateral (39%) PMI. This difference may be explained by the fact that the posteromedial papillary muscle is typically supplied by a single coronary artery, whereas the anterolateral papillary muscle is more frequently concomitantly perfused by two coronary arteries.42 Regarding MR, infarct-related culprit vessel was not independently associated with valvular regurgitation, consistent with the concept of variable arterial supply to the lateral wall.

Several limitations should be recognized. First, despite inclusion of a broad cohort of post-AMI patients, relatively few (14%) had substantial (≥moderate) MR, consistent with prior population based studies that have examined MR following AMI.43, 44 This limited our ability to examine the independent contributions of all structural variables in relation to MR, and may have resulted in some degree of overfitting in our multivariate models, which tested infarct distribution in relation to two established indices (mitral annular, left ventricular size) conventionally associated with MR. Additionally, as very few affected patients had severe MR, structural variables examined in this study could not be correlated with graded severity of valvular regurgitation. Though MR severity was measured based on regurgitant fraction, it is important to recognize that other well-validated methods for MR assessment, including effective regurgitant orifice area, were not tested. Finally, as MR was assessed within 6 weeks (27±8 days) of AMI, current findings may not apply to longer-term severity of post-AMI MR. Indeed, MR can dynamically change over time, and be influenced by LV remodeling as well as medical therapy. Additional research is necessary to examine the independent utility of mitral apparatus infarct pattern – including PMI – for prediction of long-term MR severity.

In summary, this study demonstrates the inter-relationship between papillary muscle and regional LV infarction and identifies lateral wall infarction (rather than PMI) as an independent marker for increased MR as measured early after AMI. This is the first in-vivo study to directly link regional LV infarct size and, by extension, infarct transmurality to MR. These findings are relevant to the design of therapies to treat MR, and to the tailoring of their application to individual patients. Applied clinically, findings suggest that LV plication therapies45 might be considered for CAD patients with severe MR and transmural infarction, whereas coronary reperfusion might be more beneficial as a primary strategy for patients with preserved viability in the lateral wall. DE-CMR also has the potential to guide interventional treatments for MR, such as targeted application of papillary repositioning46, 47 based on infarct distribution. More broadly, improved predictive models for MR are clinically important to better identify and promptly treat at-risk patients prior to development of adverse consequences such as cardiac chamber remodeling, heart failure, and arrhythmias. Further investigation is needed to test long-term predictors of post-AMI MR, as well as the utility of DE-CMR guided strategies to prevent or treat MR and its complications.

Acknowledgments

Sources of Funding: K23 HL102249-01, Lantheus Medical Imaging, Doris Duke Clinical Scientist Development Award (JWW)

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interests: None

Citations

- 1.Amigoni M, Meris A, Thune JJ, Mangalat D, Skali H, Bourgoun M, Warnica JW, Barvik S, Arnold JM, Velazquez EJ, Van de Werf F, Ghali J, McMurray JJ, Kober L, Pfeffer MA, Solomon SD. Mitral regurgitation in myocardial infarction complicated by heart failure, left ventricular dysfunction, or both: prognostic significance and relation to ventricular size and function. Eur Heart J. 2007;28(3):326–333. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehl464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lamas GA, Mitchell GF, Flaker GC, Smith SC, Jr, Gersh BJ, Basta L, Moye L, Braunwald E, Pfeffer MA. Clinical significance of mitral regurgitation after acute myocardial infarction. Survival and Ventricular Enlargement Investigators. Circulation. 1997;96(3):827–833. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.96.3.827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Grigioni F, Enriquez-Sarano M, Zehr KJ, Bailey KR, Tajik AJ. Ischemic mitral regurgitation: long-term outcome and prognostic implications with quantitative Doppler assessment. Circulation. 2001;103(13):1759–1764. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.103.13.1759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ennezat PV, Darchis J, Lamblin N, Tricot O, Elkohen M, Aumegeat V, Equine O, Dujardin X, Saadouni H, Le Tourneau T, de Groote P, Bauters C. Left ventricular remodeling is associated with the severity of mitral regurgitation after inaugural anterior myocardial infarction--optimal timing for echocardiographic imaging. Am Heart J. 2008;155(5):959–965. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2007.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Neskovic AN, Marinkovic J, Bojic M, Popovic AD. Early predictors of mitral regurgitation after acute myocardial infarction. Am J Cardiol. 1999;84(3):329–332. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(99)00287-8. A328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Beeri R, Yosefy C, Guerrero JL, Abedat S, Handschumacher MD, Stroud RE, Sullivan S, Chaput M, Gilon D, Vlahakes GJ, Spinale FG, Hajjar RJ, Levine RA. Early repair of moderate ischemic mitral regurgitation reverses left ventricular remodeling: a functional and molecular study. Circulation. 2007;116(11 Suppl):I288–I293. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.681114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Beeri R, Yosefy C, Guerrero JL, Nesta F, Abedat S, Chaput M, del Monte F, Handschumacher MD, Stroud R, Sullivan S, Pugatsch T, Gilon D, Vlahakes GJ, Spinale FG, Hajjar RJ, Levine RA. Mitral regurgitation augments post-myocardial infarction remodeling failure of hypertrophic compensation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;51(4):476–486. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2007.07.093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stevens LM, Basmadjian AJ, Bouchard D, El-Hamamsy I, Demers P, Carrier M, Perrault LP, Cartier R, Pellerin M. Late echocardiographic and clinical outcomes after mitral valve repair for degenerative disease. J Card Surg. 2010;25(1):9–15. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8191.2009.00897.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kongsaerepong V, Shiota M, Gillinov AM, Song JM, Fukuda S, McCarthy PM, Williams T, Savage R, Daimon M, Thomas JD, Shiota T. Echocardiographic predictors of successful versus unsuccessful mitral valve repair in ischemic mitral regurgitation. Am J Cardiol. 2006;98(4):504–508. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2006.02.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Go AS, Hylek EM, Phillips KA, Chang Y, Henault LE, Selby JV, Singer DE. Prevalence of diagnosed atrial fibrillation in adults: national implications for rhythm management and stroke prevention: the AnTicoagulation and Risk Factors in Atrial Fibrillation (ATRIA) Study. Jama. 2001;285(18):2370–2375. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.18.2370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wolf PA, Mitchell JB, Baker CS, Kannel WB, D'Agostino RB. Impact of atrial fibrillation on mortality, stroke, and medical costs. Arch Intern Med. 1998;158(3):229–234. doi: 10.1001/archinte.158.3.229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Perloff JK, Roberts WC. The mitral apparatus. Functional anatomy of mitral regurgitation. Circulation. 1972;46(2):227–239. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.46.2.227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Roberts WC, Cohen LS. Left ventricular papillary muscles. Description of the normal and a survey of conditions causing them to be abnormal. Circulation. 1972;46(1):138–154. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.46.1.138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vlodaver Z, Edwards JE. Rupture of ventricular septum or papillary muscle complicating myocardial infarction. Circulation. 1977;55(5):815–822. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.55.5.815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wei JY, Hutchins GM, Bulkley BH. Papillary muscle rupture in fatal acute myocardial infarction: a potentially treatable form of cardiogenic shock. Ann Intern Med. 1979;90(2):149–152. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-90-2-149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nishimura RA, Schaff HV, Shub C, Gersh BJ, Edwards WD, Tajik AJ. Papillary muscle rupture complicating acute myocardial infarction: analysis of 17 patients. Am J Cardiol. 1983;51(3):373–377. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(83)80067-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hider CF, Taylor DE, Wade JD. The effect of papillary muscle damage on atrioventricular valve function in the left heart. Q J Exp Physiol Cogn Med Sci. 1965;50:15–22. doi: 10.1113/expphysiol.1965.sp001766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mittal AK, Langston M, Jr, Cohn KE, Selzer A, Kerth WJ. Combined papillary muscle and left ventricular wall dysfunction as a cause of mitral regurgitation. An experimental study. Circulation. 1971;44(2):174–180. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.44.2.174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tsakiris AG, Rastelli GC, Amorim Dde S, Titus JL, Wood EH. Effect of experimental papillary muscle damage on mitral valve closure in intact anesthetized dogs. Mayo Clin Proc. 1970;45(4):275–285. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kim RJ, Fieno DS, Parrish TB, Harris K, Chen EL, Simonetti O, Bundy J, Finn JP, Klocke FJ, Judd RM. Relationship of MRI delayed contrast enhancement to irreversible injury, infarct age, contractile function. Circulation. 1999;100(19):1992–2002. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.100.19.1992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fieno DS, Kim RJ, Chen EL, Lomasney JW, Klocke FJ, Judd RM. Contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging of myocardium at risk: distinction between reversible and irreversible injury throughout infarct healing. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2000;36(6):1985–1991. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(00)00958-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Amado LC, Gerber BL, Gupta SN, Rettmann DW, Szarf G, Schock R, Nasir K, Kraitchman DL, Lima JA. Accurate and objective infarct sizing by contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging in a canine myocardial infarction model. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;44(12):2383–2389. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2004.09.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Srichai MB, Grimm RA, Stillman AE, Gillinov AM, Rodriguez LL, Lieber ML, Lara A, Weaver JA, McCarthy PM, White RD. Ischemic mitral regurgitation: impact of the left ventricle and mitral valve in patients with left ventricular systolic dysfunction. Ann Thorac Surg. 2005;80(1):170–178. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2005.01.068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.D'Ancona G, Biondo D, Mamone G, Marrone G, Pirone F, Santise G, Sciacca S, Pilato M. Ischemic mitral valve regurgitation in patients with depressed ventricular function: cardiac geometrical and myocardial perfusion evaluation with magnetic resonance imaging. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2008;34(5):964–968. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcts.2008.07.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tanimoto T, Imanishi T, Kitabata H, Nakamura N, Kimura K, Yamano T, Ishibashi K, Komukai K, Ino Y, Takarada S, Kubo T, Hirata K, Mizukoshi M, Tanaka A, Akasaka T. Prevalence and clinical significance of papillary muscle infarction detected by late gadolinium-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging in patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction. Circulation. 2010;122(22):2281–2287. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.935338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Okayama S, Uemura S, Soeda T, Onoue K, Somekawa S, Ishigami K, Watanabe M, Nakajima T, Fujimoto S, Saito Y. Clinical significance of papillary muscle late enhancement detected via cardiac magnetic resonance imaging in patients with single old myocardial infarction. Int J Cardiol. 2011;146(1):73–79. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2010.04.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nguyen TD, Spincemaille P, Weinsaft JW, Ho BY, Cham MD, Prince MR, Wang Y. A fast navigator-gated 3D sequence for delayed enhancement MRI of the myocardium: comparison with breathhold 2D imaging. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2008;27(4):802–808. doi: 10.1002/jmri.21296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zoghbi WA, Enriquez-Sarano M, Foster E, Grayburn PA, Kraft CD, Levine RA, Nihoyannopoulos P, Otto CM, Quinones MA, Rakowski H, Stewart WJ, Waggoner A, Weissman NJ. Recommendations for evaluation of the severity of native valvular regurgitation with two-dimensional and Doppler echocardiography. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2003;16(7):777–802. doi: 10.1016/S0894-7317(03)00335-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Flett AS, Hasleton J, Cook C, Hausenloy D, Quarta G, Ariti C, Muthurangu V, Moon JC. Evaluation of techniques for the quantification of myocardial scar of differing etiology using cardiac magnetic resonance. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2011;4(2):150–156. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2010.11.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sievers B, Elliott MD, Hurwitz LM, Albert TS, Klem I, Rehwald WG, Parker MA, Judd RM, Kim RJ. Rapid detection of myocardial infarction by subsecond, free-breathing delayed contrast-enhancement cardiovascular magnetic resonance. Circulation. 2007;115(2):236–244. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.635409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lang RM, Biereg M, Devereux RM, Flachskampf FA, Foster E, Pellikka PA, Picard MA, Roman MJ, Seward S, Shanewise JS, Solomon SD, Spencer KT, St John Sutton M, Stewart WJ. Recommendations for Chamber Quantification: A Report from the American Society of Echocardiography's Guidelines and Standards Committee and the Chamber Quantification Writing Group, Developed in Conjunction with the European Association of Echocardiography, a Branch of the European Society of Cardiology. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2005;18(12):1440–1463. doi: 10.1016/j.echo.2005.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Enriquez-Sarano M, Bailey KR, Seward JB, Tajik AJ, Krohn MJ, Mays JM. Quantitative Doppler assessment of valvular regurgitation. Circulation. 1993;87(3):841–848. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.87.3.841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schwammenthal E, Chen C, Benning F, Block M, Breithardt G, Levine RA. Dynamics of mitral regurgitant flow and orifice area. Physiologic application of the proximal flow convergence method: clinical data and experimental testing. Circulation. 1994;90(1):307–322. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.90.1.307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jones EC, Devereux RB, Roman MJ, Liu JE, Fishman D, Lee ET, Welty TK, Fabsitz RR, Howard BV. Prevalence and correlates of mitral regurgitation in a population-based sample (the Strong Heart Study) Am J Cardiol. 2001;87(3):298–304. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(00)01362-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kontos J, Papademetriou V, Wachtell K, Palmieri V, Liu JE, Gerdts E, Boman K, Nieminen MS, Dahlof B, Devereux RB. Impact of valvular regurgitation on left ventricular geometry and function in hypertensive patients with left ventricular hypertrophy: the LIFE study. J Hum Hypertens. 2004;18(6):431–436. doi: 10.1038/sj.jhh.1001715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Palmieri V, Bella JN, Arnett DK, Oberman A, Kitzman DW, Hopkins PN, Rao DC, Roman MJ, Devereux RB. Associations of aortic and mitral regurgitation with body composition and myocardial energy expenditure in adults with hypertension: the Hypertension Genetic Epidemiology Network study. Am Heart J. 2003;145(6):1071–1077. doi: 10.1016/S0002-8703(03)00099-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Matsuzaki M, Yonezawa F, Toma Y, Miura T, Katayama K, Fujii T, Kohtoku N, Otani N, Ono S, Tateno S, et al. Experimental mitral regurgitation in ischemia-induced papillary muscle dysfunction. J Cardiol Suppl. 1988;18:121–126. discussion 127. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Messas E, Guerrero JL, Handschumacher MD, Chow CM, Sullivan S, Schwammenthal E, Levine RA. Paradoxic decrease in ischemic mitral regurgitation with papillary muscle dysfunction: insights from three-dimensional and contrast echocardiography with strain rate measurement. Circulation. 2001;104(16):1952–1957. doi: 10.1161/hc4101.097112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kaul S, Spotnitz WD, Glasheen WP, Touchstone DA. Mechanism of ischemic mitral regurgitation. An experimental evaluation. Circulation. 1991;84(5):2167–2180. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.84.5.2167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Uemura T, Otsuji Y, Nakashiki K, Yoshifuku S, Maki Y, Yu B, Mizukami N, Kuwahara E, Hamasaki S, Biro S, Kisanuki A, Minagoe S, Levine RA, Tei C. Papillary muscle dysfunction attenuates ischemic mitral regurgitation in patients with localized basal inferior left ventricular remodeling: insights from tissue Doppler strain imaging. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005;46(1):113–119. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2005.03.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gorman JH, 3rd, Gorman RC, Plappert T, Jackson BM, Hiramatsu Y, St John-Sutton MG, Edmunds LH., Jr Infarct size and location determine development of mitral regurgitation in the sheep model. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1998;115(3):615–622. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5223(98)70326-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Voci P, Bilotta F, Caretta Q, Mercanti C, Marino B. Papillary muscle perfusion pattern. A hypothesis for ischemic papillary muscle dysfunction. Circulation. 1995;91(6):1714–1718. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.91.6.1714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pastorius CA, Henry TD, Harris KM. Long-term outcomes of patients with mitral regurgitation undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention. Am J Cardiol. 2007;100(8):1218–1223. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2007.05.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Uddin AM, Henry TD, Hodges JS, Haq Z, Pedersen WR, Harris KM. The prognostic role of mitral regurgitation after primary percutaneous coronary intervention for acute ST-Elevation myocardial infarction. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2011 doi: 10.1002/ccd.23400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Liel-Cohen N, Guerrero JL, Otsuji Y, Handschumacher MD, Rudski LG, Hunziker PR, Tanabe H, Scherrer-Crosbie M, Sullivan S, Levine RA. Design of a new surgical approach for ventricular remodeling to relieve ischemic mitral regurgitation: insights from 3-dimensional echocardiography. Circulation. 2000;101(23):2756–2763. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.101.23.2756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hung J, Guerrero JL, Handschumacher MD, Supple G, Sullivan S, Levine RA. Reverse ventricular remodeling reduces ischemic mitral regurgitation: echo-guided device application in the beating heart. Circulation. 2002;106(20):2594–2600. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000038363.83133.6d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hung J, Chaput M, Guerrero JL, Handschumacher MD, Papakostas L, Sullivan S, Solis J, Levine RA. Persistent reduction of ischemic mitral regurgitation by papillary muscle repositioning: structural stabilization of the papillary muscle-ventricular wall complex. Circulation. 2007;116(11 Suppl):I259–I263. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.679951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]