Abstract

For a century, Drosophila has been a favored organism for genetic research. However, the array of materials and methods available to the Drosophila worker has expanded dramatically in the last decade. The most common gene targeting tools, zinc finger nucleases, TALENs, and RNA-guided CRISPR/Cas9, have all been adapted for use in Drosophila, both for simple mutagenesis and for gene editing via homologous recombination.

For each tool, there exist a number of web sites, design applications, and delivery methods. The successful application of any of these tools also requires an understanding of methods for detecting successful genome modifications. This article provides an overview of the available gene targeting tools and their application in Drosophila. In lieu of simply providing a protocol for gene targeting, we direct the researcher to resources that will allow access to the latest research in this rapidly evolving field.

Keywords: TALEN, CRISPR, Zinc finger nuclease, Gene targeting, Drosophila, Nuclease, NHEJ, Homologous recombination

1. Introduction

Drosophila melanogaster has enjoyed the distinction of excellent molecular tools for genetic manipulations since the discovery of P elements in the 1970s [1, 2]. P elements were quickly developed, not only for transgenesis, but also to induce deletions and to stimulate homologous recombination [3–5]. This was followed by the development of the FLP/FRT and UAS-GAL4 systems in the early 1990’s [6–8]. Subsequently, two important events in the spring of 2000 laid the seeds for a decade of growth in genome engineering in Drosophila and other organisms. The first was the completion of the Drosophila genome sequence [9]. The second was the publication of the first method for targeted mutagenesis by homologous recombination (HR) in Drosophila [10]. In the years following these events, the field of genome engineering has gradually accelerated. The development of the site specific integrase, ΦC31, in combination with the ability to use HR to position attP sites as desired, allowed the use of transgenes while minimizing concerns about position effect [11–14]. However, all these techniques, while vastly increasing the geneticist’s toolbox, continue to have their limitations.

The development of zinc finger nucleases (ZFNs) made the stimulation of HR easier, and eliminated the necessity of first introducing P element constructs [15–17]. ZFNs could be designed to target the gene of interest, introducing a double strand break [15, 18], which has been shown repeatedly to stimulate recombination. In addition, ZFNs allowed targeted mutagenesis via nonhomologous end joining (NHEJ) [15, 16]. In the best case scenarios, ZFNs produced frequencies of mutagenesis of as many as 25% of all gametes [16]. ZFNs have been used to determine the best designs for donors, and create mutations in genes with no known nulls [19, 20]. However, ZFNs proved less than ideal, as further experiments demonstrated context effects between zinc finger modules that lowered the chances of success for individual ZFNs. Thus, a low rate of success, difficult selection protocols [21] or expensive reagents (CompoZr, Sigma-Aldrich) limited the interest of the Drosophila community in adding targeted mutagenesis to an already extensive engineering toolkit. ZFNs proved more popular in organisms with more limited genetics [22, 23].

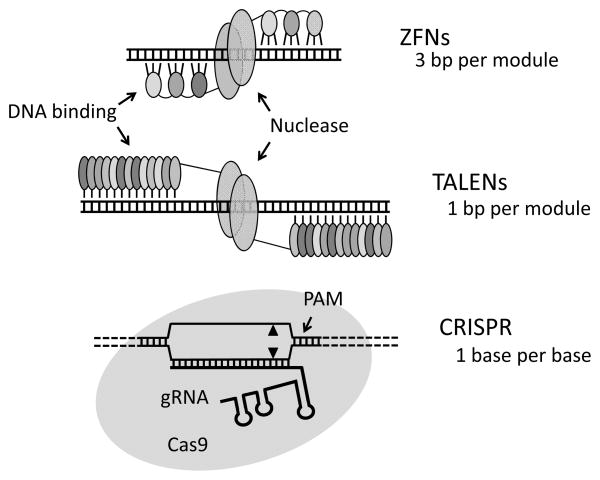

In the last several years, however, two new reagents have been developed that have re-engaged the interest of the Drosophila community. These are the transcription activator-like effector nucleases (TALENs) [24] and the RNA-guided Cas9 nuclease from the bacterial clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeat (CRISPR) system (for simplicity, we will refer to these nucleases as CRISPRs) (Figure 1). Both reagents are easier to construct, less likely to be toxic and more generally accessible to the fly community than ZFNs. Both have already been proven effective in generating targeted mutations, homologous recombination, and targeted insertions and deletions in Drosophila [25–29]. Each has specific pros and cons, which must be evaluated to determine the best tool for a given task.

Figure 1.

Diagrams of targetable nucleases. In the zinc-finger nucleases (ZFNs) and transcription activator-like effector nucleases (TALENs), each DNA-binding module is shown as a small, shaded oval; the FokI nuclease domains are large ovals. Each zinc finger contacts primarily 3 base pairs; each TALE module binds a single base pair. In both cases, two DNA-binding domains, each linked to one nuclease domain, are required to promote dimerization and cleavage. The CRISPR components are the Cas9 nuclease, a guide RNA that has about 20 bases of homology to the genomic target, and a small protospacer-adjacent motif (PAM) in the target.

The purpose of this review is to introduce the researcher to TALENs, CRISPRs, and ZFNs, along with the various techniques currently available for constructing reagents, implementing mutagenesis, and recovering mutants. We will cover available protocols, advantages and pitfalls, and direct researchers to available resources to guide them through the genome engineering process.

2. Background

2.1 Genome engineering uses cellular DNA repair machinery

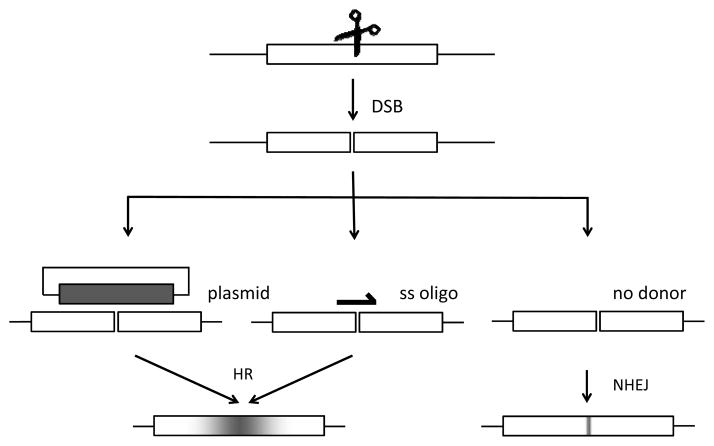

Like ZFNs, TALENs and CRISPRs both work by guiding a nuclease to a designated site of the researcher’s choice and instigating a double-strand break (DSB). At this point, cellular mechanisms take over and repair the break. The repair process must result in a change in DNA sequence to be detected. In general, there are two available repair pathways (Figure 2). The first is a simple processing and rejoining of the ends, termed non-homologous end-joining, or NHEJ. This process frequently results in small insertions or deletions (indels), often inactivating a gene by causing a frameshift or interrupting critical protein residues. On occasion, a large deletion (>100bp), or even more rarely, a large insertion may result [30].

Figure 2.

Cellular mechanisms of double-strand break (DSB) repair. Sequence changes can be introduced following a nuclease-induced DSB both by the inaccurate nonhomologous end join (NHEJ) pathway and by homologous recombination (HR), using a donor molecule as a template. Shading in the HR product indicates that the frequency of donor sequence incorporation at the target decreases with distance from the break.

The second pathway that may be used is repair by homologous recombination, or HR. If HR occurs between the broken chromosome and the sister chromatid or the homolog, the event will result in restoration of the original sequence and be undetectable. By providing a homologous donor DNA (Figure 2), the researcher can introduce a modification of choice, from single nucleotide changes to deletions to genetic tags [17, 25–29].

2.2 TALEN overview

TALENs, like ZFNs, are chimeric proteins with a designed DNA recognition domain attached to the non-specific FokI nuclease domain. This nuclease must dimerize to create a double strand break (DSB), but the dimer interface is weak and doesn’t promote dimerization effectively [31–35]. Thus, two TALENs are required to generate a designer nuclease (Figure 1). When undesired cleavage of off-target sites occurs, this is typically a property of a single TALEN or ZFN protein that dimerizes at sequences related to the intended target [16]. In order to reduce this possibility, TALENs (and ZFNs) are now often constructed with FokI variants that have been engineered to function as obligate heterodimers [36, 37].

The TALE (transcription activator-like effector) proteins were first identified in plant pathogens of the genus Xanthomonas. [38, 39]. TALEs are injected into the host plant by the bacteria, where they recognize DNA targets in the host genome and activate the expression of genes that facilitate multiplication and spread of the pathogen [40]. A typical TALE has a tandem array of 15.5–19.5 highly conserved repeats. DNA binding specificity is a function of only two residues, termed the repeat-variable diresidues (RVDs), of the ~34 that make up each of these repeats. A number of these RVDs have been characterized and selected for use in building TALENs targeted to user-defined sequences (Figure 1) [41, 42]. The DNA-recognition and binding properties of each of these modules are sufficiently independent of each other that they can be easily ordered to recognize almost any DNA sequence. However, the high degree of similarity between the multiple repeats has necessitated the development of unique cloning strategies to facilitate rapid generation of reagents. These strategies will be discussed later.

2.3. CRISPR overview

CRISPRs are the latest genome engineering tool to enter the stage [43–47]. In recent years, an adaptive immune system, termed CRISPR-Cas, has been identified in bacteria and archaea [48]. This system is based on integration into the microbial genome of DNA fragments from invading viruses, which are subsequently transcribed and processed into short CRISPR RNAs (crRNAs). In the Type II CRISPR system, this crRNA, in conjunction with a trans-activating CRISPR RNA (tracrRNA), crRNA targets Cas proteins to complementary DNA, which is then cleaved and degraded. Then, a single protein, Cas9, cleaves both strands of the target DNA as directed by the crRNA [49].

Several groups have now shown that Cas9 can be efficiently targeted either by a crRNA/tracrRNA pair, or by a single RNA, termed a guide RNA (gRNA), that has features of both (Figure 1) [25, 29, 43–45, 50–52]. With this system, two components are necessary, but only one, the gRNA, must be re-engineered for each target. The gRNA or crRNA typically has 20 base pairs of homology to the target. In addition, the target must have a PAM (protospacer adjacent motif) flanking the 3′ end of this 20 bp homology (see Figure 1). When using the most commonly available Cas9 protein, from Streptococcus pyogenes, the PAM sequence is 5′-NGG or, less effectively, NAG [53]. Cas9 from other species, with different PAMs, are being investigated as alternatives [54]. A variety of protocols are already available for generating Cas9 and the gRNA, which will be detailed below.

3. Choosing a reagent

3.1 Availability of targets

When deciding whether to use TALENs or CRISPRs to mutate a gene, several factors should be considered. There are very few restrictions on TALEN target selection. Two inverted half-sites of 15 to 20 bp, separated by 12 to 20 bp, are required. The 5′-most nucleotide of each half site should be a T. Some initial surveys of naturally occurring sites suggested some rules about what the first few bases should be, but subsequent research has shown that these rules can be largely disregarded [31, 55–57]. Recent papers indicate that even the requirement for a 5′ T may be negotiable [55, 58]. However, Streubel et al. [59] have established additional, very broad guidelines: at least three strong RVDs (targeting G or C) should be included in each TALEN monomer, and stretches of weak RVDs (for A and T, and sometimes G) greater than six should be avoided. It is worth noting that there is still some debate on the contribution of various RVDs in binding [59, 60].

Six RVDs are currently in common use. Three (in the one-letter amino acid code), NI, NG, and HD, show a high degree of specificity for their allotted targets, A, T, and C respectively [38, 61]. The fourth, NN, is the canonical RVD for targeting G. Like HD, it binds strongly to its target base, but it also binds A, in some contexts as strongly as it does G. Two other RVDs, NK and NH, are more specific for G, but bind much less strongly, with NH being the stronger of the two [59, 62].

CRISPR targets are about 23 bp long. The first 20 bp will match the designed gRNA, and this must be followed in the target by the PAM, 5′-NGG. Depending on how the gRNA is produced, there can be additional limitations on the base(s) at the 5′ end of the target. For example, the T7 and SP6 promoters currently used for in vitro RNA production, as well as the Drosophila U6 snRNA promoter commonly being used for in vivo RNA expression, require one or two Gs as the first base(s) [43, 52, 63]. Recent studies have indicated that mismatches in the 7–9 bases farthest from the PAM are more easily tolerated than those in the remaining gRNA [63], so the requirement for the 5′ Gs can be relaxed [64].

3.2. Potential off-target effects

Specificity is a concern with all of the nucleases. We encountered toxicity due to off-target cleavage with one ZFN in two of the first three pairs we produced [16, 18]. As noted above, this problem can be ameliorated by using non-homodimerizing variants of the FokI cleavage domain. This precaution is often used with TALENs, as well [26], even though research by several labs indicates that this is typically not an issue [37, 65–67]. Users should be aware that the first-generation obligate heterodimer modifications reduce cleavage activity significantly, and activity is largely restored by second-generation adjustments [26, 36].

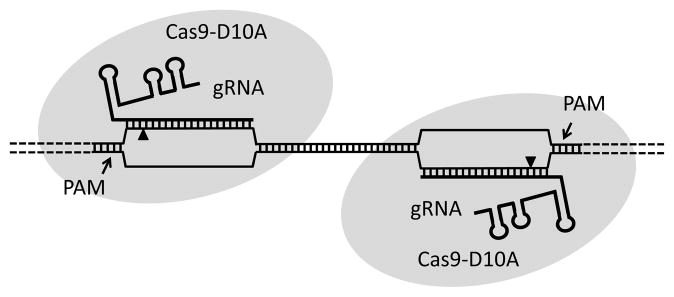

Off-target cutting by CRISPRs is still under investigation, but initial studies indicate that this is a more significant problem than it is for TALENs, as mismatches near the 5′ end of the gRNA are rather well tolerated [53, 63, 68, 69]. As an alternative, when HR is the desired result, a Cas9 nickase has been engineered which greatly reduces both the possibility of off-target mutagenesis, and end-joining mutations at the target, though at the expense of efficiency [52, 63]. Two groups have come up with an inventive way to increase the specificity of CRISPRs. They use the Cas9 nickase with two gRNAs that are targeted to closely spaced sequences on complementary strands (Figure 3). The paired nicks effectively create a double strand break that stimulates NHEJ and HR with efficiencies similar to wild type Cas9 [70, 71].

Figure 3.

Paired nicking with CRISPRs. A modified Cas9 protein with one active site mutated (D10A) cuts only one strand of the target DNA. Providing two guide RNAs (gRNAs) directed to sequences in close proximity on opposite strands leads to an effective DSB.

For two reasons off-target cleavage is somewhat less of an issue in Drosophila than in some other organisms, although the researcher must continue to be aware of the possibility. First, the genome is rather small compared to mammals, so the concentration of potential secondary targets is lower. Second, if off-target mutations are generated, it is relatively simple to avoid their effects by using independently derived mutations in a single gene, or by cleaning up the background by repeated out-crossing.

3.3. Cost

Each TALEN monomer must be individually engineered. Although a variety of protocols exist to facilitate construction, there is still a significant investment in time and materials. A number of companies and university cores also offer to design and deliver TALENs, which may be cost effective if your lab needs only one or a few pairs. Although reliable TALENs are available at a much lower cost than ZFNs, the expense is not insignificant. CRISPR reagents, in contrast, are much less expensive. The Cas9 plasmid is available from a variety of sources, including Addgene, and gRNAs can be constructed for the cost of a pair of long oligos. In addition, several companies and cores now offer CRISPR reagents.

3.4. Goals

TALENs and CRISPR appear to have equal chances of being effective both in producing targeted mutations via end-join repair and homologous recombination in Drosophila [25–29, 72]. When specificity is the principal criterion – for example, if the target is highly similar to other sequences in the genome - TALENs may be the best choice. In contrast, if several targets are to be knocked out in a single fly, CRISPR requires only the introduction of multiple gRNAs, which appear well tolerated.

4. Designing and engineering TALENS and CRISPR reagents

4.1 Tools for choosing and designing TALENs and CRISPRs

In the past two years, the tools and protocols for designing and building TALENs have burgeoned. The best choice depends on each researcher’s situation and preference. An ever-increasing number of websites offer freely available guidance or tools to design both TALENs and CRISPRs (see Table 1). Only a few are discussed here.

Table 1.

Websites for ZFN, TALEN and CRISPR design

| Website name | Website address | Primary Function |

|---|---|---|

| TAL effector | http://www.genome-engineering.org/taleffectors | TALEN information resource |

| CRISPR | http://www.genome-engineering.org/crispr | CRISPR information resource |

| TALEN Targeter | https://tale-nt.cac.cornell.edu | TALEN design |

| TALengineering.org | http://www.talengineering.org | TALEN information resource |

| E-TALEN | http://www.e-talen.org/E-TALEN | TALEN design |

| E-CRISP | http://www.e-crisp.org/E-CRISP/ | CRISPR/gRNA design |

| flyCRISPR | http://flycrispr.molbio.wisc.edu/ | fly-specific CRISPR/gRNA design |

| oxfCRISPR | http://groups.mrcfgu.ox.ac.uk/liu-group/useful-links/oxfcrispr/oxfcrispr | fly-specific CRISPR/gRNA design |

| CRISPR flydesign | http://www.crisprflydesign.org/ | fly-specific CRISPR/gRNAdesign |

| DRSC | http://www.flyrnai.org/crispr/ | searchable listing of all fly gRNA targets |

| Cas9 guide RNA design | http://cas9.cbi.pku.edu.cn | gRNA design for model systems |

| flyCas9 | http://www.shigen.nig.ac.jp/fly/nigfly/cas9/index.jsp | fly-specific CRISPR/gRNAdesign |

| EENdb | http://eendb.zfgenetics.org/index.php | database of engineered nucleases |

| Addgene | http://www.addgene.org/genome_engineering | plasmid and information resource |

| Mojo Hand | http://www.talendesign.org | TALEN design |

| ZiFIT Targeter | http://zifit.partners.org/ZiFiT | TALEN, ZFN and CRISPR design |

4.1.1. TAL effector and CRISPR at Genome-engineering.org

The forum genome-engineering.org, moderated by the Zhang lab [73], features a TAL Effector section that offers a comprehensive overview of TALENs, a reference library of primary literature (2008–2011), instructions on generating TALENs using the Zhang lab tools, and links to online design and sequence alignment tools. The site also has a CRISPR section that provides some guidance, a CRISPR tool that identifies sites sufficiently unique to be safely targeted, but does not yet search the Drosophila genome. In the meantime, there is a link to an NCBI “track” listing all possible gRNA targets in which the 12 nucleotides of the so-called seed sequence are unique. The site features very active discussion forums for both TALEN and CRISPR targeting.

4.1.2. TALEN targeter

TALEN targeter, hosted by Cornell University and developed and maintained by the Bogdanove lab, is a comprehensive tool for choosing TALEN sites, but does not currently discuss CRISPRs [31, 74]. The website allows the user to choose various ranges of TALEN spacer length based on different researchers’ results, select between NN and NH RVDs for targeting G nucleotides, choose among published guidelines, and search several model organism genomes for off- target possibilities. The tool chooses all possible TALENs, and gives the user various ways to sort among them and choose the ones best suited to their use. It also lists any restriction sites that may be disrupted by TALEN cutting and could be used in screening. Other resources on the site guide the user through TALEN assembly via the Golden Gate method, developed by the Voytas lab [31], and allow the user to investigate off-target sites and specificities. These tools may also be downloaded onto the user’s computer.

4.1.3. TALengineering.org

The Joung lab hosts a comprehensive forum and newsgroup at TALengineering.org on the various protocols available to build and design TALENs. Not all of the links and references on the pages are correct, but they are sufficient to locate the desired information.

4.1.4. E-TALEN and E-CRISP

The Boutros lab at the German Cancer Research Lab hosts E-TALEN and E-CRISP, with tools to search unique sites in, among others, the Drosophila genome, as well as tools to evaluate targets chosen by other means. E-TALEN allows a choice among several assembly kits to inform design, and both tools allow the user to specify the end purpose of the experiment (knock-out, N- or C-terminal tagging) as well as other tool-specific criteria [75].

4.1.5. Drosophila specific tools

flyCRISPR is hosted by the University of Wisconsin, and is a genome engineering tool devoted to Drosophila and CRISPR/Cas. The site gives protocols for assembling gRNAs using tools developed by the O’Connor-Giles lab in conjunction with the labs of Melissa Harrison and Jill Wildonger, discusses donor design for homologous recombination, presents Drosophila injection protocols, and hosts a news and discussion group that is devoted to Drosophila. oxfCRISPR is another Drosophila specific site, hosted by the Liu lab at Oxford University, and provides similar information to reproduce the protocol designed by their lab [25]. CRISPR flydesign, a third Drosophila tool, is hosted by the Bullock lab in Cambridge, England, and provides information about their lab tools and protocols, as well as a discussion forum. The Drosophila RNAi screening center at Harvard University, DRSC, has a searchable resource that details and locates all possible gRNA targets in the Drosophila genome, and allows application of very rigorous testing for potential off-target sites [76].. Cas9 guide RNA Design, developed by the Kong lab, is hosted at the Center for Bioinformatics, Peking University, Beijing and searches the Drosophila genome, among others [77]. FlyCas9 is hosted by the National Institute of Genetics in Kyoto, Japan, and hosts both a target finder, and protocols for following the methods of Kondo and Ueda [78]. They also provide the necessary stocks for this protocol, in conjunction with the Drosophila Genetic Resource Center, Kyoto, Japan.

4.1.6. EENdb

The Engineered EndoNuclease database (EENdb), hosted by Peking University, attempts to gather and sort all data on genome editing by technology, organism, targeted site, and results. They include links to tools, references, and protocols. Although their CRISPR/Cas information is currently limited, their TALEN and ZFN databases are well designed [79].

4.1.7 Addgene

Addgene is a non-profit plasmid repository that provides plasmids for many purposes for a minimal charge. They are distributing most of the CRISPR, ZFN, and TALEN plasmids that have been published. Their site also has links to many available web tools, and is constantly updated.

4.2 TALEN assembly protocols

At least a dozen independent assembly protocols or tool kits for building TALENs have been developed in the last two years [24, 28, 80–84]. Each of these protocols proposes to deliver completed TALENs in under one week.

4.2.1 Golden Gate Cloning

The first published protocols for constructing designer TALENs adapted the recently described Golden Gate cloning technology [31, 85–87]. Briefly, this protocol involves exploiting the separation of DNA recognition and cleavage domains in Type IIS restriction enzymes. Since the sequence of the cleavage site is unrestricted, it is possible to design modules that, after digestion with a single enzyme, e.g. BsaI, exhibit unique 4 base 5′ cohesive ends. Modules are designed and chosen to facilitate a single assembly order. Up to ten modules are combined in a single digestion/ligation reaction and assembled in the proper order in one step. Proper design results in the recognition site being lost, allowing a second reaction to join together multiple repeat arrays and clone them into an expression vector. Several labs have designed modifications of this basic method, using different restriction enzymes, using PCR to amplify modules from a smaller number of initial plasmids, building dimers, trimers and tetramers as the initial units, or modifying codon usage in the repeats to minimize repetitiveness [28, 73, 81–84, 88–91]. It should be noted the method of Katsuyama et al., designated “easy-T” results in cloning the TALEN into a vector provided with a copia promoter, for direct injection into Drosophila.

4.2.2. Non-Golden gate protocols

A smaller number of unique protocols have been introduced. REAL (Restriction Enzyme and Ligation) and REAL-Fast are protocols that use serial digestions and ligations of a library of repeat plasmids to construct TALENs [92, 93]. While REAL starts with single RVD plasmids, REAL-Fast uses preassembled series of two, three, or four RVDs as a starting point. These modules were developed for an additional protocol, FLASH [56], which moves the reaction to the solid phase, allowing multiple sequential ligations without intervening cloning steps. Other similar solid-state protocols exist [94]. An additional solid-state methodology, termed iterative capped assembly, uses a similar protocol, with the addition of a cap that can be added to each step to terminate incorrect chains [95].

A final protocol that has recently been introduced is that of ligation independent cloning [80]. This assembly method relies on the exonuclease activity of T4 DNA polymerase to generate 10–15 base single-stranded tails that can be used to anneal a library of dimer modules to create 6-mers. These 6-mers can be transformed and grown without isolation, yielding cassettes that can be subjected once again to exonuclease activity and annealing, yielding TALENs with up to 18 RVD repeats.

An interesting aspect of the many methods represented here, is that several different species of Xanthomonas have been used to provide the TALE domain framework. Although no careful comparison has been done, all seem to work reasonably well.

4.3 Engineering CRISPRs

One advantage of CRISPR mutagenesis is that the Cas9 protein, once modified for a particular organism and delivery protocol, needs no further adaptation. Only the gRNA must be re-engineered.

4.3.1. Cas9 for Drosophila

A number of Cas9 options are available to Drosophila researchers. Any Cas9 vector used for zebrafish, such as those used by the Joung lab [96] or the Wente and Chen labs [69], are adequate for generating mRNA for injection, as is the plasmid constructed by Yu et al. [29]. If you choose to do direct plasmid injection, the hsp70-Cas9 plasmid described at flyCRISPR is available through Addgene [27]. Another option available to the fly community is gRNA, or gRNA-expressing plasmid, injections into flies engineered to express Cas9, either in the germline, or ubiquitously, with or without tracrRNA. Fly lines expressing the wild type or nickase form of Cas9 are described at CRISPR flydesign (Bullock lab stocks, available from the Bullock lab) and at flyCRISPR (developed by the O’Connor-Giles, Harrison and Wildonger labs and available at the Bloomington stock center). All of these fly stocks are available prepublication, to allow more rapid access to the fly community and a wider base of testers. Ren et al. have also generated and tested two lines expressing a germline Cas9 [76], as well as a vector for expressing u6-sgRNA as have Sebo et al. [97]. Kondo and Ueda, [78] generated a Cas9 fly line they have used to cross to flies engineered to express their desired gRNA, resulting in a higher frequency of mutagenesis without requiring in vitro transcription. This protocol is not useful for HR, since it does not readily include a donor DNA, but appears efficient at generating deletions. There is good evidence accumulating that injecting into a fly expressing Cas9 is more efficient and cost effective than mRNA injections for Cas9. In addition, injecting into animals that express a germline-limited Cas9 seems to avoid the problems associated with creating widespread biallelic mutations of a lethal gene in the injected fly. We and others have observed that this is not uncommon and creates a challenging situation for mutant recovery [26, 76]. Additional lines are rapidly becoming available.

4.3.2. gRNA generation

Two primary choices exist for constructing gRNAs. The first is to synthesize long oligos carrying the unique gRNA sequence and amplify a PCR product for in vitro gRNA synthesis [25]. The second is to synthesize shorter oligos to be annealed and cloned into gRNA vectors, either for gRNA synthesis or for injection as a plasmid. A good protocol for the first is described in Basset et al. (2013) [25]. Gratz et al. have constructed a vector that will place the gRNA or a crRNA sequence under the control of the Drosophila U6 promotor for direct plasmid injection [27], as have Kondo and Ueda [78]. Any plasmid useful for generating gRNA in vitro for zebrafish injections is also useful for Drosophila RNA injections [64].

5. Homologous Recombination vs. Targeted Mutagenesis vs. Deletions

5.1. Targeted mutagenesis

The simplest use of the above tools is simply to use them to knock out the gene of interest via non-homologous end joining (NHEJ). Successful application of targeted mutagenesis requires simply the deployment of either a pair of TALENs or Cas9 plus a gRNA. Targeted mutagenesis has been demonstrated in Drosophila with ZFNs, TALENs and CRISPR [17, 25–29, 72, 78]. Repair by NHEJ generates primarily small insertions and/or deletions and relies largely on frame-shifts to eliminate gene expression.

5.1.1. Choosing the target

Target choice is key in generating a knock-out by targeted mutagenesis. Generating a frameshift late in the coding sequence may result in producing a truncated, partially active protein, or even a dominant negative allele. Thus, a target site early in the coding region is usually best when generating a simple knock-out.

5.1.2. Targeted Deletions

Given that both TALENs and CRISPR reagents are normally well tolerated by Drosophila, it is possible to generate larger targeted deletions simply by injecting two pairs of TALENs or two gRNAs directed to the sites of the desired end-points of the deletions [26, 27, 78]. Deletions generated in this manner will generally have endpoints within the targets of the two nucleases, but will not be precisely predictable.

5.2. Homologous recombination

5.2.1. Oligonucleotide donors

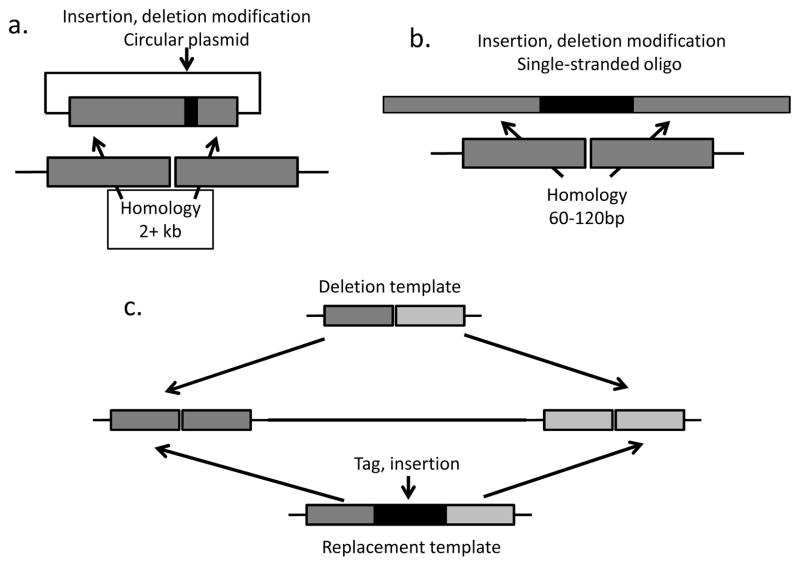

Adding a donor to CRISPR, ZFN, or TALEN mutagenesis experiments allows generation of precise mutations, templated deletions, or precise insertion of tags or markers into a desired site. Two types of donors are useful in Drosophila. The simplest to design and prepare is a single-stranded oligonucleotide (ss oligo) carrying 80–100 bases of homology to the target [19, 27] (Figure 4). The homology can be split by a tag or insert, such as an attP sequence, or can be contiguous. In fact, by properly designing a ss oligo donor (or a plasmid donor), precise deletions can be generated, or an entire gene can be replaced with a desirable feature (Figure 4) [27].

Figure 4.

A variety of donor designs have proven useful in templating HR. a. Long homologies in a circular plasmid donor allow introduction of large and small changes both close to and far from the nuclease-induced DSB. b. Single-stranded synthetic oligonucleotides can template small changes close to the break, including introduction of short sequence tags. c. Both ss oligos and long donors with homologies to sites flanking two DSBs can be used to delete large stretches of DNA, or to replace them with a desired sequence.

5.2.2. Plasmid donor

When the goal is to introduce long insertions or deletions, or to change sequences located far from the cleavage site, it is preferable to use a plasmid donor. In this case, at least one kb of homology on either side of the breakpoint is necessary to achieve good frequencies of HR [19]. Donors can be constructed in any convenient vector and should be injected as circular molecules [17, 28]. An alternative is to provide the donor à la Rong and Golic – initially as an integrated transgene that is then liberated and linearized – although this requires considerable strain construction [10, 15]. Whether the donor for injection is a ss oligo or a plasmid, concentrations between 200 μg/ml and 500 μg/ml are usually effective [19]. Although it might seem intuitive that HR would be more frequent with larger concentrations of donor, there seems to be a limit on the amount of total nucleic acids tolerated by the embryo (unpublished results).

5.2.3. Increasing the frequency of HR

The ratio of HR to NHEJ can be increased by injecting into a stock that lacks DNA ligase IV. Lig4 is necessary for repair by the canonical NHEJ pathway, and disrupting NHEJ increases the frequency of repair by HR [17, 19, 30]. Another method for increasing the ratio of HR to NHEJ is to use nickases. A single nickase, either a chimeric nuclease or Cas9, creates a single strand break [52, 63, 98]. In this situation, repair is primarily either precise (undetectable) or by HR. However, the total number of mutants generated is greatly reduced.

6. Mutation detection

6.1. G0 screening

There are a variety of ways to determine if a mutagenesis experiment has been successful. Generally, unless a germline-specific nuclease has been used, protocols that allow testing of the injected (G0) animals for signs of mutagenesis are most desirable. First the G0 flies are crossed to an appropriate stock - either a balancer stock or, if the phenotype is known and not lethal, a stock that will reveal mutant F1 animals. After allowing several days to produce F1 offspring, the G0 animals can be recovered and tested for mosaicism. Vials established by non-mosaic animals can be discarded and attention focused on the most promising lines.

If a desired mutation produces a visible, cell autonomous phenotype – for instance, a cuticle phenotype such as yellow or ebony – G0 animals can be examined for mosaic tissue. This provides an early, visible indication that targeting is successful, but this is an imperfect system for identifying potential founders, as somatic tissues can be mutated without the germline being affected and vice versa. With particularly robust TALENs and CRISPRs, G0 flies can be so well mutated that they appear phenotypically mutant, even when the phenotype requires biallelic targeting [26]. This can be a handicap if the targeted gene creates a lethal or sterile phenotype. Using germline-specific nucleases can help mitigate this concern [76]. Likewise, if HR is used to introduce a visible marker, such as GFP or mini-white, G0 animals can be screened for mosaicism, and mutant F1 animals can be identified phenotypically.

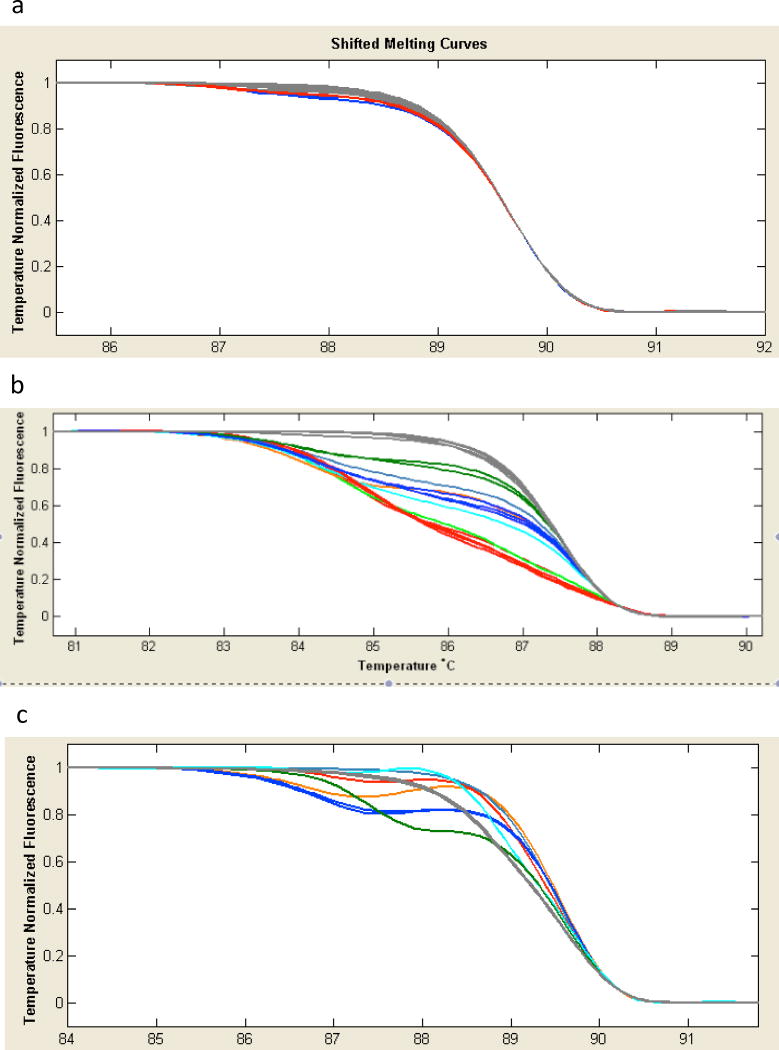

6.2. High Resolution Melting Assay

When an expected phenotype is unknown, a simple method for screening for mosaic G0 flies, or heterozygous F1 animals, is High Resolution Melting Analysis (HRMA) (Figure 5) [37]. This protocol involves amplifying a short, 90- to 150-base PCR product in the presence of appropriate dyes, followed by the generation of heteroduplexes in a final melting and reannealing step. The reactions are then tested for changes in melting curves indicating changes in sequence. HRMA requires a realtime PCR machine, or HRM dedicated machine, and appropriate software, but is highly sensitive to frequencies of mutation as low as 2 or 3 %, and is rapid and cost effective [37].

Figure 5.

Detecting mutations with HRMA. a and b, HRMA of G0 flies. Each colored trace represents melting of PCR products from an individual fly. In a, a low level of mutation is detected in 3 of the flies tested (red and blue traces are displaced slightly from the rest). In b, most of the flies show high levels of mutation. c, HRMA of F1 flies produced by crossing G0’s to a balancer stock. Each trace represents a single fly derived from two of the G0’s shown in panel a.

6.3. Mismatch detection

A number of enzyme systems have been developed that identify mosaic or heterozygous animals by cutting mismatched duplexes. The most common of these are CEL1 (Surveyor, Transgenomic) and T7 Endonuclease I (T7EI, New England Biolabs) [27, 78]. In either case, the region of interest is amplified, denatured and re-annealed to produce heteroduplexes. Cleavage occurs at the site of the mismatch, and the cut products are visible on a gel. The absence of cut product in a G0 animal indicates an absence of detectable levels of targeted chromosomes, and that animal can be eliminated from future screening. Mutant F1 animals can be identified by forming duplexes between PCR fragments from the F1 animals and wild type animals, or using heterozygous animals. In most conditions, the detection limit of these assays is in the range of a few percent.

6.4. Restriction site loss/gain

Restriction enzyme (RE) resistance can be used to screen for G0 mosaics and mutant F1 animals if the target includes a restriction site that can be mutated by NHEJ. The procedure is similar: the region of interest is amplified, cut with the relevant RE and examined on a gel for product resistant to digestion. Likewise, when a donor is used to introduce an RE site, the PCR product can be examined for sensitivity. This protocol can also be used to test for G0 mosaic animals, if a ubiquitous source of TALENs or CRISPRs has been used.

6.5. Other PCR-based detection methods

PCR can also be used to detect other types of products. Insertions and deletions will change the size of an amplified fragment. If the changes are small, high resolution by capillary electrophoresis may be required. Large deletions can be detected using primers flanking the ends of the deletion. Large insertions produced by HR would yield unique products using one primer inside the insertion and another primer outside the homology used for recombination.

7. Discussion

The initial attraction of Drosophila as a subject for genetic studies was based on its short generation time, convenient husbandry, and a remarkable range of observable phenotypes under simple Mendelian control. Novel tools and approaches have been developed over many years, including radiation-induced mutagenesis, balancer chromosomes, P element transgenesis, deletion collections, etc. Until recently, however, flies shared with most other organisms a significant deficit in the ability to introduce specific, targeted sequence changes at natural genomic loci.

With the advent of targetable nucleases, researchers can now make arbitrarily chosen modifications essentially anywhere in the genome with high accuracy, efficiency and specificity. The new tools will be used in Drosophila for basic studies of gene function – not only knockouts, but also detailed structure-function analyses. They will be used to produce models of human genetic diseases and to explore complex aspects of cellular pathways and spatial organization. The applications are limited largely by the imagination.

The choice among the available reagents – TALENs, CRISPRs and ZFNs – depends on the situation at hand. CRISPRs are in many ways the easiest to design, construct and employ, but there may be concerns about specificity. For applications in which multiple targets will be addressed, CRISPRs offer the best options for multiplexing. TALENs have few constraints in the choice of target sequence, so they may be preferred when a very precisely located cut is desired. Some existing ZFNs are still among the most effective targeted nucleases.

It seems at this point that it will be difficult to improve on the simplicity of the CRISPR system, with its reliance on a single protein and recognition through Watson-Crick base pairing. The current reagents all arose from unexpected sources, however, and additional advances may well be in the unpredictable future. All in all, this is a great time to be a geneticist.

Highlights.

TALENS, ZFNs, and CRISPRs have all been successfully used in Drosophila.

A variety of criteria are presented to evaluate the best reagent for an experiment.

Tools for target choice, reagent construction and mutant screening are presented.

Acknowledgments

Work in our lab has been supported by grants from the NIH, and in part by the University of Utah Cancer Center support grant. We are grateful to people in our lab, particularly Jon Trautman, and to Tim Dahlem at the Mutation Generation and Detection Core Facility for participation in various experiments. We have enjoyed fruitful and interesting collaborations with the labs of Dan Voytas, Scott Hawley, David Grunwald and Mike Botchan. We acknowledge the openness and enthusiasm of the pioneer users of the CRISPR technology in the fly research community that has led to active and informative web conversations.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Rubin GM, Spradling AC. Science. 1982;218:348–353. doi: 10.1126/science.6289436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Spradling AC, Rubin GM. Science. 1982;218:341–347. doi: 10.1126/science.6289435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Engels WR. Bioessays. 1992;14:681–686. doi: 10.1002/bies.950141007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Engels WR, Preston CR. Genetics. 1984;107:657–678. doi: 10.1093/genetics/107.4.657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gloor GB, Nassif NA, Johnson-Schlitz DM, Preston CR, Engels WR. Science. 1991;253:1110–1117. doi: 10.1126/science.1653452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Golic MM, Rong YS, Petersen RB, Lindquist SL, Golic KG. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:3665–3671. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.18.3665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Golic KG, Lindquist S. Cell. 1989;59:499–509. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90033-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brand AH, Dormand EL. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 1995;5:572–578. doi: 10.1016/0959-4388(95)80061-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Adams MD, Celniker SE, Holt RA, vans CAE, Gocayne JD, Amanatides PG, Scherer SE, Li PW, Hoskins RA, Galle RF, George RA, Lewis SE, Richards S, Ashburner M, Henderson SN, Sutton GG, Wortman JR, Yandell MD, Zhang Q, Chen LX, Brandon RC, Rogers YH, Blazej RG, Champe M, Pfeiffer BD, Wan KH, Doyle C, Baxter EG, Helt G, Nelson CR, Gabor GL, Abril JF, Agbayani A, An HJ, Andrews-Pfannkoch C, Baldwin D, Ballew RM, Basu A, Baxendale J, Bayraktaroglu L, Beasley EM, Beeson KY, Benos PV, Berman BP, Bhandari D, Bolshakov S, Borkova D, Botchan MR, Bouck J, Brokstein P, Brottier P, Burtis KC, Busam DA, Butler H, Cadieu E, Center A, Chandra I, Cherry JM, Cawley S, Dahlke C, Davenport LB, Davies P, de Pablos B, Delcher A, Deng Z, Mays AD, Dew I, Dietz SM, Dodson K, Doup LE, Downes M, Dugan-Rocha S, Dunkov BC, Dunn P, Durbin KJ, vangelista CCE, Ferraz C, Ferriera S, Fleischmann W, Fosler C, Gabrielian AE, Garg NS, Gelbart WM, Glasser K, Glodek A, Gong F, Gorrell JH, Gu Z, Guan P, Harris M, Harris NL, Harvey D, Heiman TJ, Hernandez JR, Houck J, Hostin D, Houston KA, Howland TJ, Wei MH, Ibegwam C, Jalali M, Kalush F, Karpen GH, Ke Z, Kennison JA, Ketchum KA, Kimmel BE, Kodira CD, Kraft C, Kravitz S, Kulp D, Lai Z, Lasko P, Lei Y, Levitsky AA, Li J, Li Z, Liang Y, Lin X, Liu X, Mattei B, McIntosh TC, McLeod MP, McPherson D, Merkulov G, Milshina NV, Mobarry C, Morris J, Moshrefi A, Mount SM, Moy M, Murphy B, Murphy L, Muzny DM, Nelson DL, Nelson DR, Nelson KA, Nixon K, Nusskern DR, Pacleb JM, Palazzolo M, Pittman GS, Pan S, Pollard J, Puri V, Reese MG, Reinert K, Remington K, Saunders RD, Scheeler F, Shen H, Shue BC, Siden-Kiamos I, Simpson M, Skupski MP, Smith T, Spier E, Spradling AC, Stapleton M, Strong R, Sun E, Svirskas R, Tector C, Turner R, Venter E, Wang AH, Wang X, Wang ZY, Wassarman DA, Weinstock GM, Weissenbach J, Williams SM, Woodage T, Worley KC, Wu D, Yang S, Yao QA, Ye J, Yeh RF, Zaveri JS, Zhan M, Zhang G, Zhao Q, Zheng L, Zheng XH, Zhong FN, Zhong W, Zhou X, Zhu S, Zhu X, Smith HO, Gibbs RA, Myers EW, Rubin GM, Venter JC. Science. 2000;287:2185–2195. doi: 10.1126/science.287.5461.2185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rong YS, Golic KG. Science. 2000;288:2013–2018. doi: 10.1126/science.288.5473.2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bateman JR, Lee AM, Wu CT. Genetics. 2006;173:769–777. doi: 10.1534/genetics.106.056945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bischof J, Maeda RK, Hediger M, Karch F, Basler K. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:3312–3317. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0611511104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gao G, McMahon C, Chen J, Rong YS. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:13999–14004. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0805843105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Huang J, Zhou W, Dong W, Watson AM, Hong Y. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:8284–8289. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0900641106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bibikova M, Beumer K, Trautman JK, Carroll D. Science. 2003;300:764. doi: 10.1126/science.1079512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Beumer K, Bhattacharyya G, Bibikova M, Trautman JK, Carroll D. Genetics. 2006;172:2391–2403. doi: 10.1534/genetics.105.052829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Beumer KJ, Trautman JK, Bozas A, Liu JL, Rutter J, Gall JG, Carroll D. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:19821–19826. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0810475105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bibikova M, Golic M, Golic KG, Carroll D. Genetics. 2002;161:1169–1175. doi: 10.1093/genetics/161.3.1169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Beumer KJ, Trautman JK, Mukherjee K, Carroll D. G3 (Bethesda) 2013 doi: 10.1534/g3.112.005439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Liu JL, Wu Z, Nizami Z, Deryusheva S, Rajendra TK, Beumer KJ, Gao H, Matera AG, Carroll D, Gall JG. Mol Biol Cell. 2009;20:1661–1670. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E08-05-0525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Maeder ML, Thibodeau-Beganny S, Osiak A, Wright DA, Anthony RM, Eichtinger M, Jiang T, Foley JE, Winfrey RJ, Townsend JA, Unger-Wallace E, Sander JD, Muller-Lerch F, Fu F, Pearlberg J, Gobel C, Dassie JP, Pruett-Miller SM, Porteus MH, Sgroi DC, Iafrate AJ, Dobbs D, McCray PB, Jr, Cathomen T, Voytas DF, Joung JK. Mol Cell. 2008;31:294–301. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.06.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Perez-Pinera P, Ousterout DG, Gersbach CA. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2012;16:268–277. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2012.06.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Carroll D. Genetics. 2011;188:773–782. doi: 10.1534/genetics.111.131433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Joung JK, Sander JD. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2013;14:49–55. doi: 10.1038/nrm3486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bassett AR, Tibbit C, Ponting CP, Liu JL. Cell Rep. 2013;4:220–228. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2013.06.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Beumer KJ, Trautman JK, Christian M, Dahlem TJ, Lake CM, Hawley RS, Grunwald DJ, Voytas DF, Carroll D. G3 (Bethesda) 2013;3:1717–1725. doi: 10.1534/g3.113.007260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gratz SJ, Cummings AM, Nguyen JN, Hamm DC, Donohue LK, Harrison MM, Wildonger J, O’Connor-Giles KM. Genetics. 2013;194:1029–1035. doi: 10.1534/genetics.113.152710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Katsuyama T, Akmammedov A, Seimiya M, Hess SC, Sievers C, Paro R. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41:e163. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yu Z, Ren M, Wang Z, Zhang B, Rong YS, Jiao R, Gao G. Genetics. 2013;195:289–291. doi: 10.1534/genetics.113.153825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bozas A, Beumer KJ, Trautman JK, Carroll D. Genetics. 2009;182:641–651. doi: 10.1534/genetics.109.101329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cermak T, Doyle EL, Christian M, Wang L, Zhang Y, Schmidt C, Baller JA, Somia NV, Bogdanove AJ, Voytas DF. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;39:e82. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Christian M, Cermak T, Doyle EL, Schmidt C, Zhang F, Hummel A, Bogdanove AJ, Voytas DF. Genetics. 2010;186:757–761. doi: 10.1534/genetics.110.120717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kim YG, Cha J, Chandrasegaran S. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93:1156–1160. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.3.1156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bitinaite J, Wah DA, Aggarwal AK, Schildkraut I. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:10570–10575. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.18.10570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Durai S, Mani M, Kandavelou K, Wu J, Porteus MH, Chandrasegaran S. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:5978–5990. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Doyon Y, Vo TD, Mendel MC, Greenberg SG, Wang J, Xia DF, Miller JC, Urnov FD, Gregory PD, Holmes MC. Nat Methods. 2011;8:74–79. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dahlem TJ, Hoshijima K, Jurynec MJ, Gunther D, Starker CG, Locke AS, Weis AM, Voytas DF, Grunwald DJ. PLoS Genet. 2012;8:e1002861. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bogdanove AJ, Schornack S, Lahaye T. Curr Opin Plant Biol. 2010;13:394–401. doi: 10.1016/j.pbi.2010.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Scholze H, Boch J. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2011;14:47–53. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2010.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Boch J, Bonas U. Annu Rev Phytopathol. 2010;48:419–436. doi: 10.1146/annurev-phyto-080508-081936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Boch J, Scholze H, Schornack S, Landgraf A, Hahn S, Kay S, Lahaye T, Nickstadt A, Bonas U. Science. 2009;326:1509–1512. doi: 10.1126/science.1178811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Moscou MJ, Bogdanove AJ. Science. 2009;326:1501. doi: 10.1126/science.1178817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chang N, Sun C, Gao L, Zhu D, Xu X, Zhu X, Xiong JW, Xi JJ. Cell Res. 2013;23:465–472. doi: 10.1038/cr.2013.45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.DiCarlo JE, Norville JE, Mali P, Rios X, Aach J, Church GM. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41:4336–4343. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Friedland AE, Tzur YB, Esvelt KM, Colaiacovo MP, Church GM, Calarco JA. Nat Methods. 2013;10:741–743. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gaj T, Gersbach CA, Barbas CF., 3rd Trends Biotechnol. 2013;31:397–405. doi: 10.1016/j.tibtech.2013.04.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gasiunas G, Siksnys V. Trends Microbiol. 2013;21:562–567. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2013.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Koonin EV, Makarova KS. RNA Biol. 2013;10:679–686. doi: 10.4161/rna.24022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Jinek M, Chylinski K, Fonfara I, Hauer M, Doudna JA, Charpentier E. Science. 2012;337:816–821. doi: 10.1126/science.1225829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Burgess DJ. Nat Rev Genet. 2013;14:80. doi: 10.1038/nrg3409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Cho SW, Kim S, Kim JM, Kim JS. Nat Biotechnol. 2013;31:230–232. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Mali P, Yang L, Esvelt KM, Aach J, Guell M, DiCarlo JE, Norville JE, Church GM. Science. 2013;339:823–826. doi: 10.1126/science.1232033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hsu PD, Scott DA, Weinstein JA, Ran FA, Konermann S, Agarwala V, Li Y, Fine EJ, Wu X, Shalem O, Cradick TJ, Marraffini LA, Bao G, Zhang F. Nat Biotechnol. 2013;31:827–832. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Esvelt KM, Mali P, Braff JL, Moosburner M, Yaung SJ, Church GM. Nat Methods. 2013;10:1116–1121. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Miller JC, Tan S, Qiao G, Barlow KA, Wang J, Xia DF, Meng X, Paschon DE, Leung E, Hinkley SJ, Dulay GP, Hua KL, Ankoudinova I, Cost GJ, Urnov FD, Zhang HS, Holmes MC, Zhang L, Gregory PD, Rebar EJ. Nat Biotechnol. 2011;29:143–148. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Reyon D, Tsai SQ, Khayter C, Foden JA, Sander JD, Joung JK. Nat Biotechnol. 2012;30:460–465. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Chen S, Oikonomou G, Chiu CN, Niles BJ, Liu J, Lee DA, Antoshechkin I, Prober DA. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41:2769–2778. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks1356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Sun N, Liang J, Abil Z, Zhao H. Mol Biosyst. 2012;8:1255–1263. doi: 10.1039/c2mb05461b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Streubel J, Blucher C, Landgraf A, Boch J. Nat Biotechnol. 2012;30:593–595. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Meckler JF, Bhakta MS, Kim MS, Ovadia R, Habrian CH, Zykovich A, Yu A, Lockwood SH, Morbitzer R, Elsaesser J, Lahaye T, Segal DJ, Baldwin EP. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41:4118–4128. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Miller JC, Holmes MC, Wang J, Guschin DY, Lee YL, Rupniewski I, Beausejour CM, Waite AJ, Wang NS, Kim KA, Gregory PD, Pabo CO, Rebar EJ. Nat Biotechnol. 2007;25:778–785. doi: 10.1038/nbt1319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Cong L, Zhou R, Kuo YC, Cunniff M, Zhang F. Nat Commun. 2012;3:968. doi: 10.1038/ncomms1962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Cong L, Ran FA, Cox D, Lin S, Barretto R, Habib N, Hsu PD, Wu X, Jiang W, Marraffini LA, Zhang F. Science. 2013;339:819–823. doi: 10.1126/science.1231143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Hwang WY, Fu Y, Reyon D, Maeder ML, Kaini P, Sander JD, Joung JK, Peterson RT, Yeh JR. PLoS One. 2013;8:e68708. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0068708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Sun N, Zhao H. Biotechnol Bioeng. 2013;110:1811–1821. doi: 10.1002/bit.24890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Hisano Y, Ota S, Arakawa K, Muraki M, Kono N, Oshita K, Sakuma T, Tomita M, Yamamoto T, Okada Y, Kawahara A. Biol Open. 2013;2:363–367. doi: 10.1242/bio.20133871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Cade L, Reyon D, Hwang WY, Tsai SQ, Patel S, Khayter C, Joung JK, Sander JD, Peterson RT, Yeh JR. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40:8001–8010. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Fu Y, Foden JA, Khayter C, Maeder ML, Reyon D, Joung JK, Sander JD. Nat Biotechnol. 2013;31:822–826. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Jao LE, Wente SR, Chen W. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110:13904–13909. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1308335110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Mali P, Aach J, Stranges PB, Esvelt KM, Moosburner M, Kosuri S, Yang L, Church GM. Nat Biotechnol. 2013;31:833–838. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Ran FA, Hsu PD, Lin CY, Gootenberg JS, Konermann S, Trevino AE, Scott DA, Inoue A, Matoba S, Zhang Y, Zhang F. Cell. 2013;154:1380–1389. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.08.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Liu J, Li C, Yu Z, Huang P, Wu H, Wei C, Zhu N, Shen Y, Chen Y, Zhang B, Deng WM, Jiao R. J Genet Genomics. 2012;39:209–215. doi: 10.1016/j.jgg.2012.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Sanjana NE, Cong L, Zhou Y, Cunniff MM, Feng G, Zhang F. Nat Protoc. 2012;7:171–192. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2011.431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Doyle EL, Booher NJ, Standage DS, Voytas DF, Brendel VP, Vandyk JK, Bogdanove AJ. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40:W117–122. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Heigwer F, Kerr G, Walther N, Glaeser K, Pelz O, Breinig M, Boutros M. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41:e190. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Ren X, Sun J, Housden BE, Hu Y, Roesel C, Lin S, Liu LP, Yang Z, Mao D, Sun L, Wu Q, Ji JY, Xi J, Mohr SE, Xu J, Perrimon N, Ni JQ. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110:19012–19017. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1318481110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Ma M, Ye AY, Zheng W, Kong L. Biomed Res Int. 2013;2013:270805. doi: 10.1155/2013/270805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Kondo S, Ueda R. Genetics. 2013;195:715–721. doi: 10.1534/genetics.113.156737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Xiao A, Wu Y, Yang Z, Hu Y, Wang W, Zhang Y, Kong L, Gao G, Zhu Z, Lin S, Zhang B. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41:D415–422. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks1144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Schmid-Burgk JL, Schmidt T, Kaiser V, Honing K, Hornung V. Nat Biotechnol. 2013;31:76–81. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Ding Q, Lee YK, Schaefer EA, Peters DT, Veres A, Kim K, Kuperwasser N, Motola DL, Meissner TB, Hendriks WT, Trevisan M, Gupta RM, Moisan A, Banks E, Friesen M, Schinzel RT, Xia F, Tang A, Xia Y, Figueroa E, Wann A, Ahfeldt T, Daheron L, Zhang F, Rubin LL, Peng LF, Chung RT, Musunuru K, Cowan CA. Cell Stem Cell. 2013;12:238–251. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2012.11.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Zhang Z, Li D, Xu H, Xin Y, Zhang T, Ma L, Wang X, Chen Z, Zhang Z. PLoS One. 2013;8:e66459. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0066459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Uhde-Stone C, Gor N, Chin T, Huang J, Lu B. Biol Proced Online. 2013;15:3. doi: 10.1186/1480-9222-15-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Sakuma T, Hosoi S, Woltjen K, Suzuki K, Kashiwagi K, Wada H, Ochiai H, Miyamoto T, Kawai N, Sasakura Y, Matsuura S, Okada Y, Kawahara A, Hayashi S, Yamamoto T. Genes Cells. 2013;18:315–326. doi: 10.1111/gtc.12037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Morbitzer R, Elsaesser J, Hausner J, Lahaye T. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;39:5790–5799. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Zhang F, Cong L, Lodato S, Kosuri S, Church GM, Arlotta P. Nat Biotechnol. 2011;29:149–153. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Engler C, Kandzia R, Marillonnet S. PLoS One. 2008;3:e3647. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0003647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Geissler R, Scholze H, Hahn S, Streubel J, Bonas U, Behrens SE, Boch J. PLoS One. 2011;6:e19509. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0019509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Li L, Piatek MJ, Atef A, Piatek A, Wibowo A, Fang X, Sabir JS, Zhu JK, Mahfouz MM. Plant Mol Biol. 2012;78:407–416. doi: 10.1007/s11103-012-9875-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Li T, Huang S, Zhao X, Wright DA, Carpenter S, Spalding MH, Weeks DP, Yang B. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;39:6315–6325. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Weber E, Gruetzner R, Werner S, Engler C, Marillonnet S. PLoS One. 2011;6:e19722. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0019722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Reyon D, Khayter C, Regan MR, Joung JK, Sander JD. Curr Protoc Mol Biol. 2012;Chapter 12(Unit 12):15. doi: 10.1002/0471142727.mb1215s100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Sander JD, Cade L, Khayter C, Reyon D, Peterson RT, Joung JK, Yeh JR. Nat Biotechnol. 2011;29:697–698. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Wang Z, Li J, Huang H, Wang G, Jiang M, Yin S, Sun C, Zhang H, Zhuang F, Xi JJ. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2012;51:8505–8508. doi: 10.1002/anie.201203597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Briggs AW, Rios X, Chari R, Yang L, Zhang F, Mali P, Church GM. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40:e117. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Hwang WY, Fu Y, Reyon D, Maeder ML, Tsai SQ, Sander JD, Peterson RT, Yeh JR, Joung JK. Nat Biotechnol. 2013;31:227–229. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Sebo ZL, Lee HB, Peng Y, Guo Y. Fly (Austin) 2013;8 doi: 10.4161/fly.26828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Ding Q, Regan SN, Xia Y, Oostrom LA, Cowan CA, Musunuru K. Cell Stem Cell. 2013;12:393–394. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2013.03.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]