Abstract

The development of new antibacterial agents has become necessary to treat the large number of emerging bacterial strains resistant to current antibiotics. Despite the different methods of resistance developed by these new strains, the A-site of the bacterial ribosome remains an attractive target for new antibiotics. To develop new drugs that target the ribosomal A-site, a high-throughput screen is necessary to identify compounds that bind to the target with high affinity. To this end, we present an assay that uses a novel fluorescein-conjugated neomycin (F-neo) molecule as a binding probe to determine the relative binding affinity of a drug library. We show here that the binding of F-neo to a model Escherichia coli ribosomal A-site results in a large decrease in the fluorescence of the molecule. Furthermore, we have determined that the change in fluorescence is due to the relative change in the pKa of the probe resulting from the change in the electrostatic environment that occurs when the probe is taken from the solvent and localized into the negative potential of the A-site major groove. Finally, we demonstrate that F-neo can be used in a robust, highly reproducible assay, determined by a Z′-factor greater than 0.80 for 3 consecutive days. The assay is capable of rapidly determining the relative binding affinity of a compound library in a 96-well plate format using a single channel electronic pipette. The current assay format will be easily adaptable to a high-throughput format with the use of a liquid handling robot for large drug libraries currently available and under development.

Keywords: Ribosome RNA, Aminoglycoside, Fluorescence, A-site, F-neo, Ribosome binding ligands, Screening

Aminoglycoside antibiotics are bactericidal agents composed of two or more amino sugars joined in glycosidic linkage to a hexose nucleus [1,2]. This family of antibiotics has been highly successful in the treatment of many bacterial diseases [3–5]. The target of many aminoglycosides, such as neomycin, is the 16S RNA of the bacterial ribosome. The binding of the aminoglycosides to the bacterial ribosome results in an inhibition of protein synthesis and translational errors that ultimately kill bacterial cells [6]. However, during recent years the emergence of resistant strains of bacteria to aminoglycosides has limited their effectiveness as antibiotics [5,7,8]. The emergence of these resistant strains has necessitated the need for new drugs and next generation aminoglycoside-based compounds to treat these pathogens.

There are numerous mechanisms by which bacteria can become resistant to aminoglycosides, including reduced uptake, changes to the ribosomal binding site, and modifications to the aminoglyco-sides by bacterial enzymes [9–11]. However, the primary characteristic of compounds with antibiotic mechanisms similar to aminoglycosides remains their ability to bind to the ribosomal A-site with high affinity. Following the identification of compounds that bind to A-site RNA, antibacterial activity can be subsequently screened against resistant bacteria cell lines. Therefore, a large number of compounds and derivatives will need to be generated and screened in order to develop drugs that are not susceptible to the mechanisms of resistance of these pathogenic bacteria. To address this need, the number of compounds for the targeting of the ribosomal A-site is rapidly increasing due in part to the derivations of natural aminoglycosides and synthetic aminoglycoside mimics as well as the development of novel compounds that act by a similar mechanism [5,12–14].

As the number of compounds grows, it becomes more urgent to develop a high-throughput screen for the identification of compounds that bind to the A-site RNA as a first approximation of antibacterial activity. Multiple methods have been used in the identification of potential antibiotics. Nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR)2 screening methods have been used previously to identify lead compounds that bind to the A-site using competition assays and other techniques [15]. However, these methods require large amounts of RNA and are not adaptable for high- throughput techniques. Fluorescently labeled RNA has been used in previous screens as a method for monitoring drug–RNA interactions. Although these derivatives have been useful tools in the detection of drug interactions with the A-site, each contains deficiencies for large-scale use in a high-throughput format.

We present here a fluorescence-based competition assay using a 27-base RNA model of the ribosomal A-site (Fig. 1) and a novel fluorescent reporter molecule. The model A-site contains the structural features of the Escherichia coli 16S RNA A-site and has been used to chemically and structurally characterize the interactions of aminoglycosides with the A-site [16–19]. In addition, we report the properties of a fluorescein derivative of neomycin (Fig. 2) that shows a robust decrease in fluorescence intensity on binding to the model ribosomal A-site. The fluorescein–neomycin conjugate (F-neo) allows the direct measurement of drug binding to the A-site. In addition, the fluorescein is attached via a thiourea linkage to neomycin at a position that is not predicted to be involved in contacts with the RNA bases in the absence of the fluorescein. We also demonstrate that the intensity change in the fluorescence is a result of a shift in the pKa for the fluorescein moiety due to the electrostatic potential (ESP) of the RNA. Finally, we show that F-neo can be used as a probe in a competition assay for the screening of compound libraries for A-site binding. This assay is readily adaptable to a high-throughput format as larger compound libraries are established.

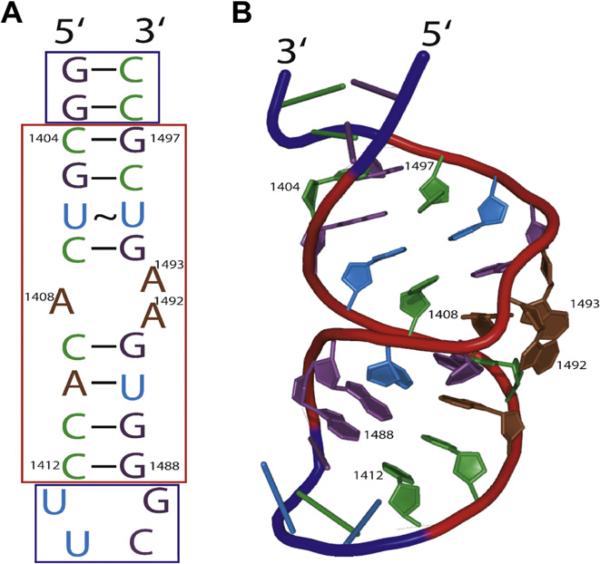

Fig.1.

E. coli ribosomal A-site. (A) Secondary structure of the model A-site used in the development of the high-throughput screen for drugs that bind to the ribosomal A-site. The red box indicates the residues that are present in the E. coli 16S ribosomal RNA (rRNA). (B) Three-dimensional representation of panel A modeled from the NMR structure of the model A-site (PDB ID: 1PBR). Residues present in the E. coli 16S rRNA are shown as cartoon bases and are color-coded purple (guanine), green (cytosine), blue (uracil), and brown (adenine) and numbered according E. coli ribosome in both panels A and B. (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the Web version of this article.)

Fig.2.

(A and B) Chemical structures of neomycin (A) and fluorescein–neomycin conjugate (F-neo) (B). (C) Equilibrium between the monoanion and dianion of fluorescein or F-neo. Only the dianion has a large fluorescence peak at 517 nm when excited at 490 nm.

Materials and methods

The E. coli A-site model RNA oligonucleotide (5′-GGCGUCACACCUUCGGGUAAGUCGCC-3′) was synthesized using standard phosphoramidite solid phase synthesis with a 2′ ACE protecting group (Thermo Scientific). All RNA oligos were deprotected before use according to the manufacturer's protocol, and the deprotection buffer was removed by evaporation using a SpeedVac (GeneVac). The RNA oligos were resuspended in diethylpyrocarbonate (DEPC-treated water (OmniPur) to the desired concentration, and the concentrations of oligonucleotides were determined by absorbance at 260-nm and 10-mm pathlengths with a Nanodrop 2000c (Thermo Scientific) using an extinction coefficient provided by the manufacturer. Neomycin (Fisher), paromomycin (MP Biomedicals), gentamycin (Fisher), streptomycin (Fisher), and ribostamycin (MP Biomedicals) were suspended in DEPC-treated water to the stock concentration. Neamine was prepared as described previously [20] and suspended in DEPC-treated water. The neomycin–fluorescein conjugate (F-neo) was synthesized and purified as described previously [21]. Briefly, F-neo was prepared by coupling an activated fluorescein ester with neomycin amine followed by deprotection of Boc groups using trifluoroacetic acid (TFA).

Absorbance measurements of F-neo were obtained using a Cary 1E ultraviolet–visible (UV–Vis) spectrophotometer at 490 nm with a pathlength of 10 mm in 10 mM Mopso, 0.4 mM ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA), and 50 mM NaCl. The concentration of F-neo was 3.0 μM for all measurements, and the concentration of E. coli A-site oligo was 3.3 μM when present.

All dockings were performed as blind dockings using AutoDock Vina 1.0 [22]. Docking was performed using an “exhaustiveness” value of 12. All other parameters were used as default. All rotatable bonds within the ligand were allowed to rotate freely, and the A-site was kept rigid. All ligand structures were created using Discovery Studio Visualizer 2.5 and then brought to their energetically minimized structures by the Vega ZZ program [23] using a conjugate gradient method with an SP4 force field. AutoDock Tools version 1.5.4 [24] was used to convert the ligand and receptor molecules to the proper file formats for AutoDock Vina docking. All structures were visualized, and images were made using Pymol [25].

ESP calculation was performed on the model ribosome A-site alone by solving the nonlinear Poisson–Boltzmann equation using the Adaptive Poisson–Boltzmann Solver (APBS) [26] with the Pymol interface. Calculations were run at 150 mM NaCl with a probe size of 1.4 Å. The van der Waals radius and partial charges of the atoms of the RNA were calculated using Amber force fields as implemented in PDB2PQR [27,28].

Cuvette-based fluorescence measurements were made using a Photon Technology International spectrofluorometer (Lawrenceville, NJ, USA) with a slit width of 1.5 nm and an excitation wavelength of 490 nm. Emission scans were measured from 500 to 575 nm. Temperature was held at 25 °C, and samples were stirred with a stir bar. Samples contained a buffer composed of 10 mM Mopso, 0.4 mM EDTA, and 50 mM NaCl at pH 7.0 as well as 0.3 μM A-site oligonucleotide and 0.3 μM F-neo in standard assay or as indicated in the figure captions. Samples were titrated with increasing concentrations of aminoglycosides, and the change in fluorescence intensity was recorded.

Binding affinity was determined from the emission spectra measured at 517 nm in 10 mM Mopso, 50 mM NaCl, and 0.4 mM EDTA at pH 7.0. The concentration of F-neo was 0.3 μM, and the E. coli A-site was titrated at the indicated molar equivalents. Scatchard analysis was performed as described previously [14].

The displacement of F-neo from the E. coli ribosomal A-site RNA by neomycin was performed in 200-μl volumes at 0.3 μM neomycin to 0.1 μM E. coli A-site/F-neo complex using 100 reads/well with a Genios Pro plate reader (Tecan) in a 96-well black round-bottom plate (Greiner). The emission was measured at a wavelength of 535 nm using an excitation wavelength of 485 nm, and all experiments were performed in 10 mM Mopso, 50 mM NaCl, and 0.4 mM EDTA at pH 7.0.

Fluorescent anisotropy measurements were performed in a quartz cuvette using a Jobin Yvon Horiba Fluoromax-3 spectrofluorometer and an excitation wavelength of 485 nm. Changes in emission were measured at 517 nm. Samples contained 0.1 μM A-site and 0.1 μM F-neo in a buffer composed of 10 mM Mopso, 0.4 mM EDTA, and 50 mM NaCl at pH 7.0. Samples were titrated with increasing concentrations of neomycin as indicated, and the change in fluorescence anisotropy was recorded.

Results and discussion

Mechanism of fluorescence change for A-site RNA-bound F-neo

F-neo consists of a known A-site binding molecule, neomycin, with a known fluorescent dye, fluorescein (Fig. 2). Fluorescein has been highly characterized and is known to exist in four different protonation states [29,30]. The monoanion and dianion are the only two relevant states at biological pH, with a pKa between 6 and 7. The dianion has a strong absorbance peak at 485 nm and gives a strong emission peak at 517 nm, whereas the monoanion absorbs weakly at 485 nm with negligible emission efficiency at 517 nm when excited at 485 nm [31]. This change in the excitation and emission properties of fluorescein has allowed this molecule to be used as a probe for changing pH as well as the electrostatic environment [32].

The quenching of the fluorescein dye is unique from dyes such as coumarin and the oxazine used in “smart probes” [33,34]. These dyes are quenched in the presence of guanines by an electron transfer from the guanine to the dye's excited state; however, these dyes are not sensitive to changes in the electrostatic environment. Fluorescein is ideally suited for the detection for assays of nucleic acid binding. Although guanines may contribute to the quenching of fluorescein [35], the major contributor to the quenching appears to be the change in the electrostatic environment [36,29]. Previous work has demonstrated that fluorescein is quenched only in the presence of the phosphate groups of nucleic acid, and no quenching occurs when linked to peptide nucleic acids (PNAs) [36]. In addition, conjugating fluorescein can alter the pKa between the monoanion and dianion species [29].

The value of the F-neo probe is that it has similar fluorescent properties to nonconjugated fluorescein and maintains similar binding properties to nonconjugated neomycin, both of which can be exploited using a simple fluorescence-based assay to measure the A-site binding affinities of molecules. The excitation and emission wavelengths of F-neo are unchanged compared with those of fluorescein. The titration of F-neo with A-site oligonucleo-tide results in approximately a 3-fold decrease in the fluorescence observed at 517 nm (Fig. 3). Scatchard analysis indicates one binding site of F-neo per oligonucleotide and a dissociation constant of 43 nM, consistent with previously reported values for the binding of neomycin to the ribosomal A-site [17,37,38].

Fig.3.

Emission spectrum from a titration of bacterial A-site into F-neo. (A) Emission spectra of 0.3 μM F-neo excited at 490 nm with the addition of 0 μM (black circles) to 0.45 μM (red circles) of the model E. coli ribosomal RNA A-site. (B) Graphical analysis of the fluorescence emission peak (517 nm) of 0.3 μM F-neo with increasing concentrations of A-site. Results were normalized to molar equivalents of A-site to molar equivalents of F-neo. Experiments were performed in 10 mM Mopso, 0.4 mM EDTA, and 50 mM NaCl at pH 7.0. (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the Web version of this article.)

To investigate the mechanism of quenching of F-neo on binding to the A-site RNA, the equilibrium between the fluorescent and nonfluorescent forms of F-neo was determined by evaluating the absorbance spectrum as a function of pH (Fig. 4). As with the nonconjugated fluorescein, we examined the equilibrium between a nonfluorescent monoanion and a fluorescent dianion species of the fluorescein moiety of F-neo (Fig. 2). The absorption spectra as a function of pH for F-neo give a pKa between the monoanion and dianion of 6.84. This value is similar to the pKa of 6.37 determined for free fluorescein and other fluorescein-conjugated probes [32,29,39]. The small change in the pKa between F-neo and fluorescein indicates that the conjugation to neomycin does not significantly alter the fluorescent properties of fluorescein and demonstrates that the equilibrium between the monoanion and dianion forms of fluorescein is present in F-neo. The similarity in the pH-dependent absorbance of F-neo with fluorescein illustrates that the properties that are exploited for fluorescein as a probe can also be attributed to F-neo.

Fig.4.

Effect of A-site oligonucleotide on the pKa of F-neo. (A) Absorbance spectra of F-neo. Absorbance spectra of 3.0 μM F-neo in 10 mM Mopso, 0.4 mM EDTA, and 50 mM NaCl at pH 7.10 (D), pH 5.95 (L), and pH 2.5 (F). (B) Absorbance (490 nm) of F-neo as a function of pH in the absence (solid circles) and presence (open circles) of the model A-site RNA. Data points were derived from absorbance spectra in a buffer containing 10 mM Mopso, 0.4 mM EDTA, and 50 mM NaCl with the pH adjusted by the addition of sodium hydroxide accordingly.

On binding to A-site RNA, the dianion form of the free F-neo is destabilized by the negative potential of the RNA backbone, shifting the equilibrium toward nonfluorescent monoanion. The electrostatic potential (ψ) of nucleic acids can be measured by a pKa shift of the fluorescein [29,40]. The ψ at the binding site is directly proportional to the shift in pKa of the fluorescein by Eq. (1):

| (1) |

where R = 8.312 J mol–1 K–1, T = 298.2 K, NA = 6.023 × 1023, and e = 1.602 × 10–19.

When monitoring the absorption spectrum in the presence of the A-site RNA, we observed a reduction in A490 at pH 7.0 and a shift in the pKa (Fig. 4), consistent with a shift in equilibrium toward the protonated nonfluorescent form of F-neo on binding to the A-site. The binding of the E. coli A-site to F-neo causes an apparent shift in the pKa to 7.70, resulting in a ΔpKa of 0.86. Previous studies have shown that changes in the electrostatic environment of fluorescein changes the pKa between the monoanion and dianion species of the dye [40]. Our titration experiments indicate that this change in pKa also occurs in F-neo. The presence of the A-site increases the pKa of F-neo by nearly 1 pH unit.

Using Eq. (1), the electrostatic potential of the microenviroment for the bound fluorescein moiety of F-neo is –2.1 kT/e compared with the bulk solvent. The NMR structure of the model A-site with paromomycin shows that the aminoglycoside binds in the major groove of the RNA [17]. The X-ray crystal structure of neomycin in complex with a similar model A-site shows that the neomycin localizes in the major groove of the A-site [19]. Molecular modeling of F-neo with the A-site model suggests that the probe localizes in the major groove of the RNA, and the fluorescein moiety is positioned adjacent to the phosphates on the edge of the groove (Fig. 5A–C). The ESP of the model A-site indicates that the major groove is highly electronegative (Fig. 5D), with a potential of –15 to –25 kT/e within the major groove of the A-site.

Fig.5.

Docking of F-neo with the model ribosomal A-site. F-neo (A, cyan) was docked onto the ribosomal A-site using AutoDock (see Materials and methods). The positioning of paromomycin (B, yellow) with the model A-site was determined from the NMR structure (PDB ID: 1PBR), and the position of neomycin (C, green) in the model A-site was determined by the superimposition of the neomycin/A-site crystal structure (PDB ID: 2A04) onto the paromomycin NMR structure using the backbone atoms of common residues. In all three structures, rings I and II are in approximately the same position. (D) The docking of F-neo into the A-site places the fluorescein moiety into the major groove. The electrostatic surface mapped onto the model A-site shows the large negative potential associated with the major groove of the A-site. (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the Web version of this article.)

F-neo as a probe for a competitive binding assay

The fundamental properties that are unique to F-neo are its robust change in fluorescence on binding to the A-site RNA, as discussed above, and its specific binding to the A-site in a similar manner to that of other aminoglycosides. As discussed previously, molecular modeling studies have shown that the neomycin moiety of F-neo binds in the major groove in a fashion similar to that of the nonconjugated neomycin. This model of binding is further supported by the change in pKa, indicating that F-neo has localized into the highly electronegative environment of the major groove of the RNA. In addition, and most relevant to the development of a high-throughput assay, the F-neo is displaced by the addition of neomycin. Previous reports have shown that neomycin has nanomolar affinity for the model ribosomal A-site [38], which is similar to the affinity of F-neo determined here. We observe that titrating neomycin into the F-neo/A-site complex increases the fluorescence in a dose-dependent manner with a 1:1 stoichiometric ratio of drug-to-complex and an IC50 value of 89 nM (Fig. 6A). In addition, a strong signal window, measured as an increase in fluorescence, is present at a 2:1 M ratio, making F-neo an attractive candidate for probing A-site binding through competition assay with compound libraries.

Fig.6.

Displacement of F-neo from the A-site by neomycin. Fluorescence emission intensity (A) and anisotropy (B) of 0.1 μM F-neo/A-site complex with increasing concentrations of neomycin. Excitation of 485 nm was used in both experiments. (A) Emission measured at 535 nm with a 96-well fluorescence plate reader, resulting in an IC50 of 89 nM. (B) Emission measured at 517 nm using a spectrofluorometer, resulting in an IC50 of 78 nM. Experiments were performed in 10 mM Mopso, 0.4 mM EDTA, and 50 mM NaCl at pH 7.0.

Although other fluorescent probes have been developed for the screening of A-site binding compounds, F-neo offers many advantages for the development of a high-throughput screen. Previous probes have been incorporated into the bases of a model A-site, allowing changes in the fluorescence to be measured as changes to the RNA occur on drug binding [13,41,42]. In other techniques, fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET) analysis is used by labeling the RNA with a donor molecule and labeling an aminoglycoside with an acceptor dye [43,44]. Although these techniques give greater insight into the conformational changes that occur in the A-site on drug binding, these techniques require the specific labeling of the RNA bases for the detection of binding. In addition, these techniques could potentially detect binding events that could give rise to changes in the structure of the RNA and fluorescence of the dye that are unrelated to competitive binding.

Other probes that bind directly to the A-site RNA have been developed that can directly detect the binding of compounds through a competition assay. However, the binding of these compounds can be determined only through anisotropy measurements [38, 45–48]. In addition, the conjugation of these molecules occurs through amide linkages on ring I of the aminoglycosides. Structural information from NMR and X-ray crystallography indicate that aminoglycosides interact with the A-site through contacts at this position.

F-neo has several advantages over previous probes in that the fluorophore is attached to a molecule that binds to the ribosomal A-site. This combination allows the measurement of fluorescent change to be directly related to the binding or dissociation of the probe and not to changes in the RNA that are correlated to drug binding. In addition, the shift in the equilibrium from the highly fluorescent dianion to the nonfluorescent monoanion results in a large fluorescence signal between the unbound dianion F-neo and the bound monoanion species of F-neo.

In addition to standard fluorescent experiments, fluorescent anisotropy measurements can also be performed with the F-neo probe and the A-site RNA. Although the fluorescent signal is largely quenched on binding to the RNA A-site, a measurable fluorescent signals remains. The remaining fluorescent signal allows for anisotropic measurements to be used as a tool to determine the binding of the probe to the RNA. In addition, a competition assay from anisotropic data using neomycin results in an IC50 value of 78 nM, a similar value to that using standard fluorescence (Fig. 6B).

Finally, F-neo has advantages over other fluorescently labeled A-site binding compounds due to the linkage of the fluorescein with neomycin. The linkage through the 5′ position of the ribose ring III is predicted through previous structures and modeling to be less intrusive in the binding of neomycin to the A-site RNA [19]. The low impact of the attachment at this position is confirmed by the similarities in the binding affinity F-neo and neomycin. This linkage also leaves the amine of ring I free to interact with the A-site. This change in the linkage of F-neo compared with other probes likely maintains the affinity and specificity of the aminoglycoside for the binding site to RNA.

Screening of RNA binding drugs

We have developed a drug screen based on the displacement of F-neo to determine the binding of compounds to the ribosomal A-site (Fig. 7A). This screen involves the displacement of F-neo by A-site binding molecules in a 96-well plate format using a fluorescence plate reader. Using the initial studies of this system, the quenching of the F-neo is used as a measure of binding to the A-site RNA. The displacement of F-neo by a competitive binding molecule is measured by an increase in fluorescence.

Fig.7.

Competitive binding assay using the F-neo probe. (A) Schematic of the competitive binding assay showing the increase in the fluorescence by the displacement of the probe by a competitive binding ligand. (B) Screening of an aminoglycoside library. Aminoglycosides were added at 0.3 μM neomycin, gentamycin, paromomycin, neamine, ribostamycin, and streptomycin to 0.1 μM E. coli A-site/F-neo complex. Each result was taken from the average of 2 wells/aminoglycoside. The emission was measured at a wavelength of 535 nm using an excitation wavelength of 485 nm. All experiments were performed in 10 mM Mopso (pH 7.0), 0.4 mM EDTA, and 50 mM NaCl (green) or 50 mM KCl (blue). F–Fo is calculated by subtracting the fluorescence of the experiment with the aminoglycoside present from the fluorescence of the A-site/F-neo complex in the absence of the aminoglycoside. (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the Web version of this article.)

The quality of the assay was determined by the calculation of the Z′-factor [49]. The Z′-factor is a statistical parameter used to determine the statistical significance between the positive and negative controls. Consistent with other similar assays, 48 wells were used as the positive control and 48 wells were used as the negative control, and three independent experiments were run on 3 consecutive days, with a Z′-factor calculated for each day to determine any variation between assays [50–52]. The final assay results were obtained using the average (μn) and standard deviation (σn) from 48 wells of 0.1 μM F-neo/E. coli model ribosomal A-site as the negative control and from the average (μp) and standard deviation (σp) from 48 wells of 0.1 μM F-neo/E. coli model ribosomal A-site mixed with 0.3 μM neomycin as the positive control.

The Z′-factor was calculated using Eq. (2) for the displacement of F-neo from the E. coli A-site by neomycin:

| (2) |

The three independent experiments performed on 3 consecutive days resulted in Z′-factors of 0.81, 0.80, and 0.82. The accepted scale of the Z′-factor is >0.5 is excellent, <0.5 but >0 is marginal, and <0 is unacceptable [49]. Our results indicate that the assay is suitable for the detection of drugs that bind to the ribosomal A-site of E. coli by the displacement of the F-neo probe.

The assay is capable of measuring the relative binding affinity of a drug library compared with neomycin in the 96-well format. The difference between the fluorescence intensity baseline of F-neo/A-site complex and complex with added drug (F–Fo) indicates the extent of the competition of drug for the binding site. The results of the assay establish the relative binding affinities of aminoglyco-sides tested to be neomycin > paromomycin ~ gentamycin > neamine > ribostamycin > streptomycin (Fig. 7 B). These results are consistent with the previously reported relative binding affinity of the aminoglycosides for the bacterial ribosomal A-site obtained by other methods [17,47,48], and the results of the assay are consistent in the presence of Na+ or K+ ions. These results further show that an F-neo-based assay can be used for rapid and efficient screening of aminoglycoside libraries for drug candidates.

The F-neo probe is versatile in that it can be used for standard fluorescence-based assays or anisotropy measurements. The probe is also versatile in its ability to bind to alternate nucleic acid targets [21,53–60], opening up the possibility for the development of similar assays for other therapeutic RNA and DNA targets. The assay presented here could act as the first approximation for RNA binding to identify lead compounds. More cumbersome, slower, and/or expensive secondary assays on the identified compounds, such as gel electrophoresis, circular dichroism (CD), and similar assays, would need to be performed to ensure the RNA's stability in the presence of the drug, which is outside the scope of the assay presented here, and in vivo assays could be performed to determine potential therapeutic agents.

Conclusion

The development of a high-throughput screen of a drug library requires that the probe has a robust signal, the results of the assay are highly reproducible, and the results of the assay are accurate. The above results demonstrate that our assay meets each of these criteria. In addition, the setup of a high-throughput assay should be rapid and simple. In our assay, the E. coli model A-site is premixed with in buffer with F-neo before addition to the wells of the plate. This allows the F-neo/A-site complex to be rapidly added to each well, followed by the rapid addition of each compound to be tested. Our assay takes less than 10 min for the setup of a 96-well plate using a single channel repeat pipette for the addition of the F-neo/A-site complex and a single channel micropipette for the addition of the library. In addition, time trials of the assay have demonstrated that the equilibration of the displacement of F-neo occurs rapidly, so no incubation is required following the addition of the compounds (data not shown) and the plates can be immediately measured on a plate reader.

The assay presented here is comparable in simplicity, speed, and scale to other fluorescence-based competition screens, such as those previously used to screen A-site binding [61], as well as fluorescent intercalator displacement (FID) assays using thiazole orange for the screening of G-quadruplexes [62] and FID assays using ethidium bromide to screen DNA binding affinity of compound libraries [63]. As with these fluorescence-based competition assays, our screen is readily adaptable to a high-throughput format with the implementation of a 386-well plate and liquid handling robotic systems [64,65]. In addition, the optimal reaction volumes and the concentration of the F-neo probe were determined by the monitoring of the standard deviation of the measurements using manual pipetting. It is likely that the conversion to robotic systems will improve the precision of these measurements and allow for even smaller volumes and lower concentrations to be used. The adaptation of the screen presented here to a high-throughput format could be a standard method for screening large libraries of potential antibiotics for ribosomal A-site binding.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (R15CA125724 and R41GM097917). We thank Professor Jeffrey T. Petty (Furman University) for his help with anisotropy experiments.

Footnotes

Abbreviations used: NMR, nuclear magnetic resonance; F-neo, fluorescein–neomycin conjugate; ESP, electrostatic potential; DEPC, diethylpyrocarbonate; EDTA, ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid.

References

- 1.Chow CS, Bogdan FM. A structural basis for RNA–ligand interactions. Chem. Rev. 1997;97:1489–1514. doi: 10.1021/cr960415w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arya DP. Aminoglycoside–nucleic acid interactions: the case for neomycin. Top. Curr. Chem. 2005;253:149–178. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schatz A, Bugie E, Waksman SA. Streptomycin, a substance exhibiting antibiotic activity against Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria. Proc. Soc. Exp. Biol. Med. 1944;55:66–69. doi: 10.1097/01.blo.0000175887.98112.fe. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Waksman SA, Lechevalier HA. Neomycin, a new antibiotic active against streptomycin-resistant bacteria, including tuberculosis organisms. J. Antibiot. 1949;109:305–309. doi: 10.1126/science.109.2830.305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Arya DP. Aminoglycoside Antibiotics: From Chemical Biology to Drug Discovery. Wiley-Interscience; Hoboken, NJ: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lynch SR, Puglisi JD. Structural origins of aminoglycoside specificity for prokaryotic ribosomes. J. Mol. Biol. 2001;306:1037–1058. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2000.4420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.De Stasio EA, Moazed D, Noller HF, Dahlberg AE. Mutations in 16S ribosomal RNA disrupt antibiotic–RNA interactions. EMBO J. 1989;8:1213–1216. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1989.tb03494.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhou J, Wang G, Zhang LH, Ye XS. Modifications of aminoglycoside antibiotics targeting RNA. Med. Res. Rev. 2007;27:279–316. doi: 10.1002/med.20085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Davies J, Wright GD. Bacterial resistance to aminoglycoside antibiotics. Trends Microbiol. 1997;5:234–240. doi: 10.1016/S0966-842X(97)01033-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Beauclerk A, Cundliffe E. Sites of action of two ribosomal–RNA methylases responsible for resistance to aminoglycosides. J. Mol. Biol. 1987;193:661–671. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(87)90349-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mingeot-Leclercq M, Glupczynski Y, Tulkens P. Aminoglycosides: activity and resistance. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 1999;43:727–737. doi: 10.1128/aac.43.4.727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhou Y, Gregor VE, Ayida BK, Winters GC, Sun Z, Murphy D, Haley G, Bailey D, Froelich JM, Fish S, Webber SE, Hermann T, Wall D. Synthesis and SAR of 3,5-diamino-piperidine derivatives: novel antibacterial translation inhibitors as aminoglycoside mimetics. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2007;17:1206–1210. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2006.12.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bryan MC, Wong C-H. Aminoglycoside array for the high-throughput analysis of small molecule–RNA interactions. Tetrahedron Lett. 2004;45:3639–3642. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kumar S, Kellish P, Robinson WE, Jr., Wang D, Appella DH, Arya DP. Click dimers to target HIV TAR RNA conformation. Biochemistry. 2012;51:2331–2347. doi: 10.1021/bi201657k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yu L, Oost TK, Schkeryantz JM, Yang J, Janowick D, Fesik SW. Discovery of aminoglycoside mimetics by NMR-based screening of Escherichia coli A-site RNA. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003;125:4444–4450. doi: 10.1021/ja021354o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fourmy D, Recht MI, Blanchard SC, Puglisi JD. Structure of the A site of Escherichia coli 16S ribosomal RNA complexed with an aminoglycoside antibiotic. Science. 1996;274:1367–1371. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5291.1367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fourmy D, Recht MI, Puglisi JD. Binding of neomycin-class aminoglycoside antibiotics to the A-site of 16S rRNA. J. Mol. Biol. 1998;277:347–362. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1997.1552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Recht MI, Fourmy D, Blanchard SC, Dahlquist KD, Puglisi JD. RNA sequence determinants for aminoglycoside binding to an A-site rRNA model oligonucleotide. J. Mol. Biol. 1996;262:421–436. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1996.0526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhao F, Zhao Q, Blount K, Han Q, Tor Y, Hermann T. Molecular recognition of RNA by neomycin and a restricted neomycin derivative. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2005;44:5329–5334. doi: 10.1002/anie.200500903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Park WKC, Auer M, Jaksche H, Wong C-H. Rapid combinatorial synthesis of aminoglycoside antibiotic mimetics: use of a polyethylene glycol-linked amine and a neamine-derived aldehyde in multiple component condensation as a strategy for the discovery of new inhibitors of the HIV RNA Rev responsive element. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1996;118:10150–10155. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Xi H, Davis E, Ranjan N, Xue L, Hyde-Volpe D, Arya DP. Thermodynamics of nucleic acid “shape readout” by an aminosugar. Biochemistry. 2011;50:9088–9113. doi: 10.1021/bi201077h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Trott O, Olson AJ. AutoDock Vina: improving the speed and accuracy of docking with a new scoring function, efficient optimization, and multithreading. J. Comput. Chem. 2010;31:455–461. doi: 10.1002/jcc.21334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pedretti A, Villa L, Vistoli G. VEGA—an open platform to develop chemo-bioinformatics applications, using plug-in architecture and script programming. J. Comput. Aided Mol. Des. 2004;18:167–173. doi: 10.1023/b:jcam.0000035186.90683.f2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sanner MF. Python: a programming language for software integration and development. J. Mol. Graphics Modell. 1999;17:57–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Brunger A, Adams P, Clore G, DeLano W, Gros P, Grosse-Kunstleve R, Jiang J, Kuszewski J, Nilges M, Pannu N, Read R, Rice L, Simonson T, Warren G. Crystallography and NMR system: a new software suite for macromolecular structure determination. Acta Crystallogr. D. 1998;54:905–921. doi: 10.1107/s0907444998003254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Baker NA, Sept D, Joseph S, Holst MJ, McCammon JA. Electrostatics of nanosystems: application to microtubules and the ribosome. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2001;98:10037–10041. doi: 10.1073/pnas.181342398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dolinsky TJ, Czodrowski P, Li H, Nielsen JE, Jensen JH, Klebe G, Baker NA. PDB2PQR: expanding and upgrading automated preparation of biomolecular structures for molecular simulations. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:W522–W525. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dolinsky TJ, Nielsen JE, McCammon JA, Baker NA. PDB2PQR: an automated pipeline for the setup, execution, and analysis of Poisson–Boltzmann electrostatics calculations. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:W665–W667. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lavis LD, Rutkoski TJ, Raines RT. Tuning the pKa of fluorescein to optimize binding assays. Anal. Chem. 2007;79:6775–6782. doi: 10.1021/ac070907g. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Friedrich K, Woolley P. Electrostatic potential of macromolecules measured by pKa shift of a fluorophore. Eur. J. Biochem. 1988;173:227–231. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1988.tb13988.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Alvarez-Pez J, Ballesteros L, Talavera E, Yguerabide J. Fluorescein excited-state proton exchange reactions: nanosecond emission kinetics and correlation with steady-state fluorescence intensity. J. Phys. Chem. 2001;105:6320–6332. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Friedrich K, Woolley P, Steinhauser KG. Electrostatic potential of macromolecules measured by pKa shift of a fluorophore: 2. Transfer RNA. Eur. J. Biochem. 1988;173:233–239. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1988.tb13989.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Knemeyer JP, Marme N, Sauer M. Probes for detection of specific DNA sequences at the single-molecule level. Anal. Chem. 2000;72:3717–3724. doi: 10.1021/ac000024o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Marras SA, Kramer FR, Tyagi S. Efficiencies of fluorescence resonance energy transfer and contact-mediated quenching in oligonucleotide probes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002;30:e122. doi: 10.1093/nar/gnf121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ranasinghe RT, Brown T. Fluorescence based strategies for genetic analysis. Chem. Commun. 2005;44:5487–5502. doi: 10.1039/b509522k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sjoback R, Nygren J, Kubista M. Characterization of fluorescein–oligonucleotide conjugates and measurement of local electrostatic potential. Biopolymers. 1998;46:445–453. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0282(199812)46:7<445::AID-BIP2>3.0.CO;2-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hamasaki K, Rando RR. Specific binding of aminoglycosides to a human rRNA construct based on a DNA polymorphism which causes aminoglycoside-induced deafness. Biochemistry. 1997;36:12323–12328. doi: 10.1021/bi970962r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ryu D, Rando R. Aminoglycoside binding to human and bacterial A-site rRNA decoding region constructs. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2001;9:2601–2608. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0896(01)00034-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Diehl H, Horchak-Morris N. Studies on fluorescein. 5. The absorbency of fluorescein in the ultraviolet, as a function of pH, Talanta. 1987;34:739–741. doi: 10.1016/0039-9140(87)80232-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Friedrich K, Woolley P. Electrostatic potential of macromolecules measured by pKa shift of a fluorophore. 1. The 30 terminus of 16S RNA. Eur. J. Biochem. 1988;173:227–231. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1988.tb13988.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Llano-Sotelo B, Azucena EF, Kotra LP, Mobashery S, Chow CS. Aminoglycosides modified by resistance enzymes display diminished binding to the bacterial ribosomal aminoacyl–tRNA site. Chem. Biol. 2002;9:455–463. doi: 10.1016/s1074-5521(02)00125-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Liang F, Greenberg WA, Hammond JA, Hoffmann J, Head SR, Wong C. Evaluation of RNA-binding specificity of aminoglycosides with DNA microarrays. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2006;103:12311–12316. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0605264103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kaul M, Barbieri CM, Pilch DS. Fluorescence-based approach for detecting and characterizing antibiotic-induced conformational changes in ribosomal RNA: comparing aminoglycoside binding to prokaryotic and eukaryotic ribosomal RNA sequences. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004;126:3447–3453. doi: 10.1021/ja030568i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Xie Y, Dix AV, Tor Y. FRET enabled real time detection of RNA–small molecule binding. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009;131:17605–17614. doi: 10.1021/ja905767g. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wang Y, Rando RR. Specific binding of aminoglycoside antibiotics to RNA. Chem. Biol. 1995;2:281–290. doi: 10.1016/1074-5521(95)90047-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wang Y, Killian J, Hamasaki K, Rando RR. RNA molecules that specifically and stoichiometrically bind aminoglycoside antibiotics with high affinities. Biochemistry. 1996;35:12338–12346. doi: 10.1021/bi960878w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wang Y, Hamasaki K, Rando RR. Specificity of aminoglycoside binding to RNA constructs derived from the 16S rRNA decoding region and the HIV–RRE activator region. Biochemistry. 1997;36:768–779. doi: 10.1021/bi962095g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ryu DH, Litovchick A, Rando RR. Stereospecificity of aminoglycoside–ribosomal interactions. Biochemistry. 2002;41:10499–10509. doi: 10.1021/bi026086l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zhang JH, Chung TD, Oldenburg KR. A simple statistical parameter for use in evaluation and validation of high throughput screening assays. J. Biomol. Screen. 1999;4:67–73. doi: 10.1177/108705719900400206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Grimes KD, Aldrich CC. A high-throughput screening fluorescence polarization assay for fatty acid adenylating enzymes in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Anal. Biochem. 2011;417:264–273. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2011.06.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Duffy S, Avery VM. Development and optimization of a novel 384-well anti-malarial imaging assay validated for high-throughput screening. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2012;86:84–92. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.2012.11-0302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Morelock MM, Hunter EA, Moran TJ, Heynen S, Laris C, Thieleking M, Akong M, Mikic I, Callaway S, DeLeon RP, Goodacre A, Zacharias D, Price JH. Statistics of assay validation in high throughput cell imaging of nuclear factor kappa B nuclear translocation. Assay Drug Dev. Technol. 2005;3:483–499. doi: 10.1089/adt.2005.3.483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Willis B, Arya DP. An expanding view of aminoglycoside–nucleic acid recognition. Adv. Carbohydr. Chem. Biochem. 2006;60:251–302. doi: 10.1016/S0065-2318(06)60006-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Shaw NN, Xi H, Arya DP. Molecular recognition of a DNA:RNA hybrid: subnanomolar binding by a neomycin–methidium conjugate. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2008;18:4142–4145. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2008.05.090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Willis B, Arya DP. Major groove recognition of DNA by carbohydrates. Curr. Org. Chem. 2006;10:663–673. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Willis B, Arya DP. Recognition of B-DNA by neomycin–Hoechst 33258 conjugates. Biochemistry. 2006;45:10217–10232. doi: 10.1021/bi0609265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ranjan N, Andreasen KF, Kumar S, Hyde-Volpe D, Arya DP. Aminoglycoside binding to Oxytricha nova telomeric DNA. Biochemistry. 2010;49:9891–9903. doi: 10.1021/bi101517e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Willis B, Arya DP. Triple recognition of B-DNA by a neomycin–Hoechst 33258–pyrene conjugate. Biochemistry. 2010;49:452–469. doi: 10.1021/bi9016796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Xue L, Ranjan N, Arya DP. Synthesis and spectroscopic studies of the aminoglycoside (neomycin)–perylene conjugate binding to human telomeric DNA. Biochemisry. 2011;50:2838–2849. doi: 10.1021/bi1017304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kumar S, Xue L, Arya DP. Neomycin–neomycin dimer: an all-carbohydrate scaffold with high affinity for AT-rich DNA duplexes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011;133:7361–7375. doi: 10.1021/ja108118v. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Hamasaki K, Rando RR. A high-throughput fluorescence screen to monitor the specific binding of antagonists to RNA targets. Anal. Biochem. 1998;261:183–190. doi: 10.1006/abio.1998.2740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Tran PL, Largy E, Hamon F, Teulade-Fichou MP, Mergny JL. Fluorescence intercalator displacement assay for screening G4 ligands towards a variety of G-quadruplex structures. Biochimie. 2011;93:1288–1296. doi: 10.1016/j.biochi.2011.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Boger D, Fink B, Hedrick M. Total synthesis of distamycin A and 2640 analogues: a solution-phase combinatorial approach to the discovery of new, bioactive DNA binding agents and development of a rapid, high-throughput screen for determining relative DNA binding affinity or DNA binding sequence selectivity. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2000;122:6382–6394. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Glass LS, Bapat A, Kelley MR, Georgiadis MM, Long EC. Semi-automated high-throughput fluorescent intercalator displacement-based discovery of cytotoxic DNA binding agents from a large compound library. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2010;20:1685–1688. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2010.01.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Largy E, Hamon F, Teulade-Fichou MP. Development of a high-throughput G4–FID assay for screening and evaluation of small molecules binding quadruplex nucleic acid structures. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2011;400:3419–3427. doi: 10.1007/s00216-011-5018-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]