Abstract

The Problem

Conducting community-partnered research conferences is a powerful yet underutilized approach to translating research into practice and improving result dissemination and intervention sustainability strategies. Nonetheless, detailed descriptions of conference features and ways to use them in empirical research are rare.

Purpose of Article

We describe how community-partnered conferences may be integrated into research projects by using an example of Community Partners in Care, a large cluster-randomized controlled trial that uses Community Partnered Participatory Research principles.

Key Points

Our conceptual model illustrates the role community-partnered research conferences may play in three study phases and describes how different conference features may increase community engagement, build two-way capacity, and ensure equal project ownership.

Conclusion(s)

As the number of community-partnered studies grows, so too does the need for practical tools to support this work. Community-partnered research conferences may be effectively employed in translational research to increase two-way capacity-building and promote long-term intervention success.

Introduction

Conducting inclusive community-partnered research conferences to engage community, increase their participation in research, and ensure shared project ownership is a powerful yet underutilized approach to translating research into practice and improving intervention sustainability. Such conferences are held in community-trusted locations where grassroots community members, including those not directly involved in the research, are invited to attend, partner with academics to conduct research, build capacity through trainings on evidence-based practices, learn about research findings through community-academic co-led presentations, and provide input on how the research findings may be interpreted and used to influence policy-makers.1,2 Community-partnered research conferences are quite different from academic research conferences and community-wide events. On the one hand, academic research conferences are typically held at universities or convention centers and primarily organized by and for the scientific community. When community members are engaged, they rarely participate as equal partners; instead, they are typically treated as passive recipients of research results or potential study subjects.3 On the other hand, community-wide events, such as health fairs, are not typically focused on research per se and are organized by community members, held in community locations, and may invite academics to help increase community awareness of a particular disease.4

Community-partnered research conferences have a potential to help community and academic partners share knowledge about community concerns and problems that can be addressed using evidence-based treatment approaches; decrease the level of community distrust in research; strengthen community-academic partnerships; and increase community ownership of interventions and their outcomes.1,2 Nonetheless, there are few empirical evaluations of community-partnered research conferences in the Community-Based Participatory Research (CBPR) literature,2 only one model of how such conferences can be conducted,1 and no discussion of how they can be integrated into large-scale randomized quality improvement (QI) trials.

The goal of this paper, which was written by academic and community partners who have been working together for more than four years, is to describe the process of planning and conducting community-partnered research conferences to explain how they may be integrated into research projects to facilitate the translation of research into practice and policy. To do so, we use the experiences of Community Partners in Care (CPIC), a large cluster randomized controlled trial (RCT) that tests two different approaches for implementing and disseminating evidence-based collaborative care interventions for depression.5 Because the detailed description of the CPIC study and its outcomes is outside of the scope of this paper, we focus on the planning and execution of the community-partnered research conferences and discuss how community-partnered research conferences may increase community engagement, build two-way capacity, and ensure equal project ownership, which are critical for successful translation of research into practice.

Community Conferences in the CBPR Literature

Although previous research suggests that community engagement/empowerment, capacity-building, and shared project ownership separate partnered research from other forms of collaborative and action-oriented research6 and that large-scale community conferences can help projects reach these goals,1 there is insufficient information in the CBPR literature on how to systematically integrate community-partnered research conferences in the context of rigorous research studies. Articles that discuss community research conferences often either summarize presentations and panel discussions from a particular conference7,8 or briefly mention community conferences or forums without discussing how they were conducted and evaluated.9–11

Our literature review results suggest that conferences are commonly used as a community engagement tool.3,14–17 High levels of engagement at conferences is typically achieved by inviting community partners to share their knowledge of community needs and interests;11,12 involving them in agenda planning and participant recruitment;12,13 advertising the conferences widely, making registration free, and offering conference participants networking opportunities.14,15 Although articles may report high levels of community engagement, they rarely explain how conference features and activities were designed to facilitate participants’ research capacity and sense of project ownership.6,16 For example, many community conferences are modeled after academic research conferences, which often focus only on sharing research findings with the community rather than having knowledge transfer,1 and do not focus on hands-on practical activities and skill-building exercises that can increase community participation in research and ensure long-term use of conference/training materials.

A typical community conference described in the literature uses a didactic approach and focuses on information delivery to conference participants rather than helping them identify concrete ways of using conference materials and study findings in their own agencies for QI purposes. 3,18–21 Articles that detail approaches to community capacity-building often report on training and education interventions that had limited sample sizes.17 Moreover, published articles rarely describe conference features that can help community partners increase their level of research commitment, sense of project ownership, and/or engagement with the project after the conference. A notable exception is Salihu et al’s article,12 which describes how community feedback from the first conference evaluation was used to design subsequent conferences and how community-valued products were developed to ensure continuous project engagement and a sense of ownership.

Furthermore, we know of only one model of conducting community research conferences in the CBPR literature, which was developed by Healthy African American Families (HAAF) to explain how to promote community engagement, two-way capacity-building, and shared project ownership.1 Although the stated objectives of this model are not unique in the CBPR field, what sets this model apart is the way these goals are achieved. In particular, the HAAF conference model (1) challenges researchers to make the research process transparent and open to the community, which helps decrease the level of community distrust in research; (2) requires that scientific information be translated in such a way that lay community members can understand and utilize it, which increases community capacity to use research to reduce health disparities; (3) calls for research results to be given back to the community, thereby increasing community ownership of the research data collected in the community; and (4) stresses the importance of equal information exchange and project ownership throughout all research phases, which increases the practical use of study findings.

Although the HAAF model describes features of successful community engagement conferences, less is known about the optimal ways of using such conferences in large-scale CBPR RCTs, the golden standard in medical research, implemented in natural settings. The lack of information on community-partnered research conferences in the peer-reviewed literature may be attributed to the fact that this topic may be considered too applied for peer-reviewed scientific journals. While community and academic conference organizers may have a wealth of experiences that they are ready to share, academic journals may be more interested in publishing RCT results than articles on how to conduct community-partnered research conferences. Therefore, we outline a conceptual model of how community-partnered research conferences may be utilized throughout different phases of RCTs by building on the HAAF-type community engagement conference model and using CPIC as an example.

Community Partners in Care Study

CPIC is the only large cluster RCT that has utilized all elements of the HAAF community engagement conference model1 and conducted multiple conferences throughout the project to engage community, build capacity, and ensure research participation and shared project ownership. Fielded in two underserved communities in Los Angeles (South Los Angeles and Hollywood/Metro), CPIC is adapting an evidence-based, collaborative care model developed by the Partners in Care study to community settings.5,18 The project recruited 536 agency administrators/providers and 1,018 clients from 50 partner agencies. Study agencies offer mental health, social, faith-based, health, and substance abuse services (see Table 1). They were randomized to test the effectiveness of two approaches to implementing and disseminating QI interventions in community-based agencies: (1) a low-intensity Resources for Services (RS) intervention approach that relies on capacity-building through technical assistance via webinars and conference calls for providers and (2) a high-intensity Community Engagement and Planning (CEP) approach that relies on collaborative intervention planning, design, and implementation strategies and employs Community Partnered Participatory Research (CPPR) methods–a manualized version of the CBPR approach.19,20 As a CPPR project, CPIC relies on the principles of joint academic-community leadership, community participation, and capacity-building. Community and academic partners equally share decision-making power and knowledge, develop mutual trust, and possess the right to disagree; both are represented on the project’s Steering Council.21 CPIC has a phase-based project structure and uses community-partnered research conferences to smoothly transition from one phase to another.

Table 1.

CPIC Participating Agencies

|

Service Planning Area (SPA) 4 Hollywood/Metro Los Angeles |

Service Planning Area (SPA) 6 South Los Angeles |

|---|---|

| AIDS Healthcare Foundation | All Peoples Christian Center |

| Amanecer Community Counseling Services | Asian American Drug Abuse Program |

| Assistance League of Southern California | Augustus Hawkins Mental Health Center |

| BHS, Inc. | Avalon Carver Community Center |

| City of LA Department of Recreation and Parks | Black Women for Wellness |

| Clínica Monseñor Oscar Romero | Bryant Temple African Methodist Episcopal Church |

| DMH Downtown Mental Health Center | Children’s Institute, Inc. |

| DMH Hollywood Mental Health Center | Curves Culver City |

| Downtown Women’s Center | DMH West Central Mental Health Center |

| Gateways Hospital | Drew Child Development Corp. |

| Hope Street Family Center | First African Presbyterian Church |

| Jewish Family Services Los Angeles | Free N’ One |

| JWCH Institute, Inc. | His Sheltering Arms |

| LAC + USC Healthcare Network | Homeless Outreach Program Integrated Care System |

| Los Angeles Christian Health Centers | INMED Mothernet Los Angeles |

| Para Los Niños | Institute for Black Parenting |

| People Assisting the Homeless | Kaiser Permanente Watts Counseling and Learning Center |

| QueensCare Health & Faith Partnership | Kedren Mental Health Center |

| Skid Row Housing Trust | New Vision Church of Jesus Christ |

| St. Thomas the Apostle Church | People Coordinated Services |

| The Saban Free Clinic | Personal Involvement Center, Inc. |

| Volunteers of America | Profile Designs |

| South Central Prevention Coalition | |

| St. John’s Well Child & Family Center | |

| THE Clinic, Inc. | |

| United Women in Transition | |

| Watts Health Foundation | |

| Watts Labor Community Action Center | |

| CPIC Steering Council Agencies | |

| Avalon Carver Community Center | Los Angeles County Department of Mental Health |

| Behavioral Health Services, Inc. | Los Angeles Urban League |

| Cal State University Dominguez Hills | NAMI Urban Los Angeles |

| Charles Drew University of Medicine and Science | National Institute of Mental Health |

| Children’s Bureau | New Vision Church of Jesus Christ |

| City of Los Angeles Department of Recreation and Parks |

People Assisting The Homeless |

| COPE Health Solutions | QueensCare Family Clinics |

| DMH- West Central Mental Health Center | QueensCare Health & Faith Partnership |

| First African Presbyterian Church | RAND Health |

| Healthy African American Families II | St. John’s Well Child & Family Center |

| Homeless Outreach Program/Integrated Care System | The Saban Free Clinic |

| Jewish Family Services of Los Angeles | THE Clinic, Inc. |

| Kaiser Watts Counseling & Learning Center | UCLA Semel Institute Center for Health Services & Society |

| Los Angeles Christian Health Centers | USC Keck School Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences |

CPIC Conference Features

CPIC considers community-partnered research conferences a crucial component of CBPR projects. While each CPIC conference has its own goals, all conferences are designed to help engage community in research; build two-way capacity to understand, participate in, and utilize research; and ensure shared project participation and ownership (see Table 2). Each conference goal is operationalized and measured to track conference effectiveness.2 Conference evaluation forms, information collected using handheld devices distributed to all conference attendees, and post-conference interviews with conference attendees and organizers are used for conference evaluation purposes; all data collection procedures are optional and approved by RAND Institutional Review Board. Below we describe how different CPIC conferences are designed to help reach three overarching study goals and use conference evaluation data to describe participants’ feedback.

Table 2.

Three Goals of Partnered Research Projects and Key Features of Community-Partnered Research Conferences that May Help Achieve Them

| Goals of Partnered Research Projects |

Recommended Conference Features |

|---|---|

| Community Engagement |

|

| Two-Way Capacity Building |

|

| Shared Project Participation and Ownership |

|

Community Engagement

All CPIC conferences are widely advertised in community, are free of charge, take place in non-university settings, and offer plenty of opportunities for attendees to network and actively participate in different conference activities. Conference topics are selected based on community needs and interests, and all conferences are planned by a team of community and academic partners. Free breakfasts and lunches are served at each conference, and raffles are held to motivate participants to stay until the end of the conference. Fun activities, such as aromatherapy, drumming, and yoga sessions, are offered to conference participants to ensure high level of conference attendance and to create a community-friendly environment.

Two-Way Capacity-Building

CBPR assumes that participation in research is a win-win situation for all parties involved.22 While academic partners gain a better understanding of community problems and needs, community partners learn about research and evidence-based approaches to improving community health.6 To ensure that both community and academic partners can benefit from conference attendance, CPIC conference seating arrangements are planned in advance. Round tables are used to facilitate interaction among conference attendees, and name cards are placed on the tables to ensure that community and academic partners are intermingled. CPIC also offers Continuing Education Units to all attendees so that agency representatives can be paid for the time they spend on improving their capacity. All conference materials are available in English and Spanish and are distributed free of charge to attendees so that they can share them with colleagues who were not able to attend.

Shared Project Participation and Ownership

Shared project participation and ownership are always emphasized at CPIC conferences. Community and academic partners equally participate in the study design and data collection and analysis. Any discoveries made during the project are co-owned by them. In terms of interpersonal relationships, participants are required to treat each other equally and respectfully. All CPIC presentations are given jointly by community and academic partners to ensure that complex information is presented in an easy-to-understand and useful format, questions are answered promptly, and the practical value of conference material is clearly explained. At the request of community partners, the audience response system is used to help conference organizers collect real time data on attendees’ comprehension and perceived usefulness of presented material, which makes it easier to modify how the information is presented.

Conceptual Model of Integrating Community-Partnered Research Conferences in Scientific Studies

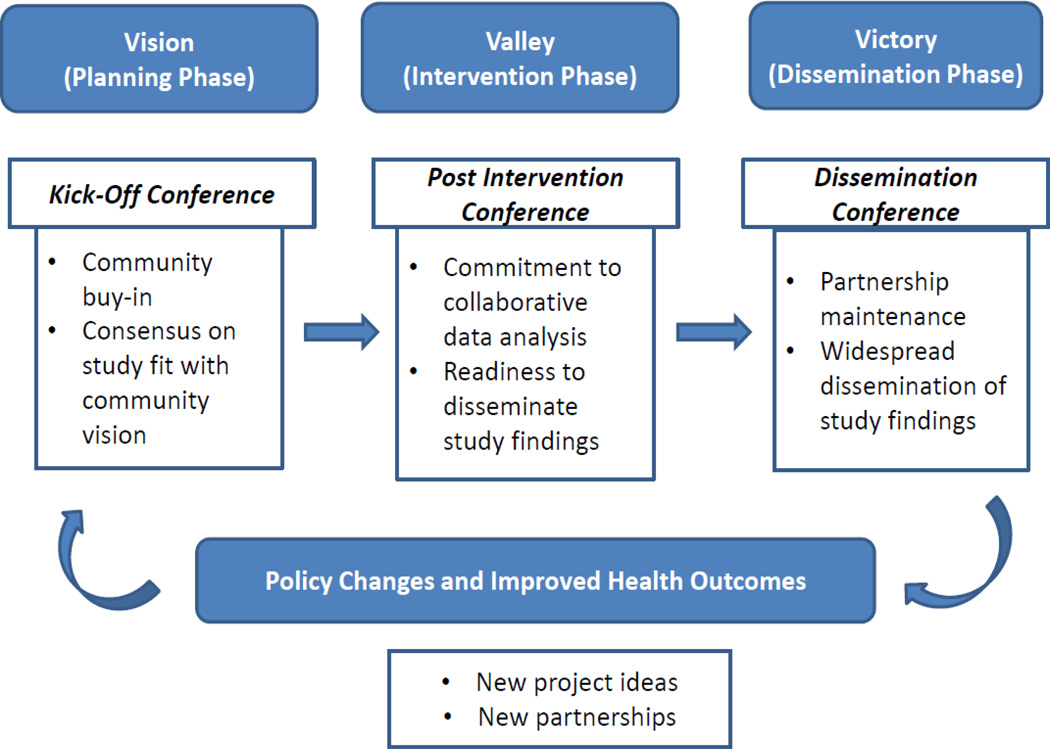

Figure 1 illustrates how conferences can engage community in all research phases, build two-way capacity, and ensure shared project participation and ownership. It also shows how conferences can be integrated into research projects by allowing study leaders to share with community project participants what was learned during the preceding phase, obtain community feedback on the activities planned for the next phase, and work with community on result dissemination and intervention sustainability issues. Below we describe how community-partnered research conferences were integrated into CPIC and illustrate how different conference features were designed and implemented to help reach three study goals.

Figure 1.

A Model for Integrating Community-Partnered Research Conferences in Scientific Studies

Phase I-Vision

The first CPIC phase, called Vision, is the intervention planning phase.23 It focused on clarifying project goals and developing a strategy for community-academic collaboration. Most of the study activities took place within the study Steering Council and different committees, such as design, operations and recruitment, implementation evaluation, and community engagement.19,20

Project Kick-Off Conference

To celebrate a transition to the intervention phase, two kick-off conferences were conducted. 257 participants representing a wide range of agencies attended these two conferences (see Table 3). Titled “It Takes a Village: Beating Depression in Our Community,” these conferences took place before agency randomization into the two study arms and focused on explaining the study design, reinforcing agencies’ interest in the study, and introducing participants to evidence-based approaches to treating depression used in CPIC (see Tables 4 and 5).2 Although the importance of obtaining stakeholder buy-in prior to implementing evidence-based practices and conducting research studies is well-documented in the implementation science literature,24,25 CPIC kick-off conferences were designed to identify additional relevant stakeholders in community; to activate interest and participation in the randomized QI trial among already recruited agencies; to stimulate a dialogue, promote a sense of collective efficacy, and offer opportunities for learning and networking; and to introduce evidence-based toolkits and collaborative care models. Finally, both conferences have been evaluated by the CPIC implementation evaluation workgroup; evaluation results were published in a peer-reviewed journal.2 Community buy-in and commitment, as well as consensus on the study fit with community vision were developed during this conference, which helped move the project into the next phase.

Table 3.

CPIC Conference Participation by Agency Type

| Agency Type | Kick-Off Conference in South LA n (%) |

Kick-Off Conference in Hollywood n (%) |

Post- Intervention Conference n (%) |

Dissemination Conference n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary care | 2 (2%) | 24 (20%) | 14 (13%) | 13 (11%) |

| Mental health services | 22 (16%) | 24 (20%) | 18 (17%) | 14 (12%) |

| Substance abuse | 26 (19%) | 5 (4%) | 14 (13%) | 8 (7%) |

| Homeless services | 0 | 2 (1%) | 3 (3%) | 5 (4%) |

| Social community services | 45 (33%) | 29 (24%) | 38 (35%) | 40 (35%) |

| Academic Institutions | 38 (28%) | 32 (26%) | 20 (18%) | 35 (30%) |

| Unknown | 2 (2%) | 6 (5%) | 1 (1%) | 1 (1%) |

| Total | 135 | 122 | 108 | 116 |

Table 4.

Kick-Off Conference Agenda and Learning Objectives (South Los Angeles)

| Welcome and Study/Partner Introduction and History |

|

| Panel on Community Models for Delivering Services |

|

| Panel on Research Models of Collaborative Care for Depression |

|

| Why Community Partners in Care? |

|

| Breakout Session I: Treating Depression: Diagnosis and Treatment Choices |

|

| Breakout Session II: Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) |

|

| Breakout Session III: Care Management, Case Work and Outreach |

|

| Breakout Session IV: Care Team Leadership |

|

| Conference Wrap-up and Community Engagement Activity “Stone Soup” |

|

Table 5.

Kick-Off Conference Agenda and Learning Objectives (Hollywood/Metro LA)

| Welcome. The History of CPIC: Meet the Partners |

|

| Let’s Talk About Depression: How Does Depression Manifest Itself in a Variety of Populations in Hollywood/Metro LA? (open dialogue with community) |

|

| Panel on the Strengths of the Collaborative Care for Depression Research Model |

|

| Discussion on the Status of Depression Care in Our Community: What are the Issues, Problems, and Potential Solutions? (open dialogue with community) |

|

| Community Engagement Activity “Stone Soup” |

|

| Breakout Session I: Treating Depression: Diagnosis and Treatment Choices |

|

| Breakout Session II: Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) |

|

| Breakout Session III: Care Management, Case Work and Outreach |

|

| CPIC is Coming to a Computer Near You! |

|

| Conference Wrap-up |

|

Community Engagement

To help participants feel more comfortable sharing their ideas and participate in conference activities, CPIC conferences use ice-breakers and community engagement exercises. For example, the kick-off conferences used a “Stone Soup” exercise to illustrate the value of cooperation among the entire community when resources are scarce.26 In the “Stone Soup” story, a traveler, who only has an empty pot, stones, and water, invites several townsfolk to make soup by adding very small amounts of ingredients they had in their possession. Many people contribute to the soup adding what they could to the pot. Eventually, a pot of delicious soup is made and shared by the entire community. In this CPIC ice-breaker, agency representatives were encouraged to describe the resources already available in community to treat depression and that could be leveraged by CPIC. This exercise helped deliver a message that by working together, community representatives could generate new perspectives on reducing health disparities even when resources are scarce.

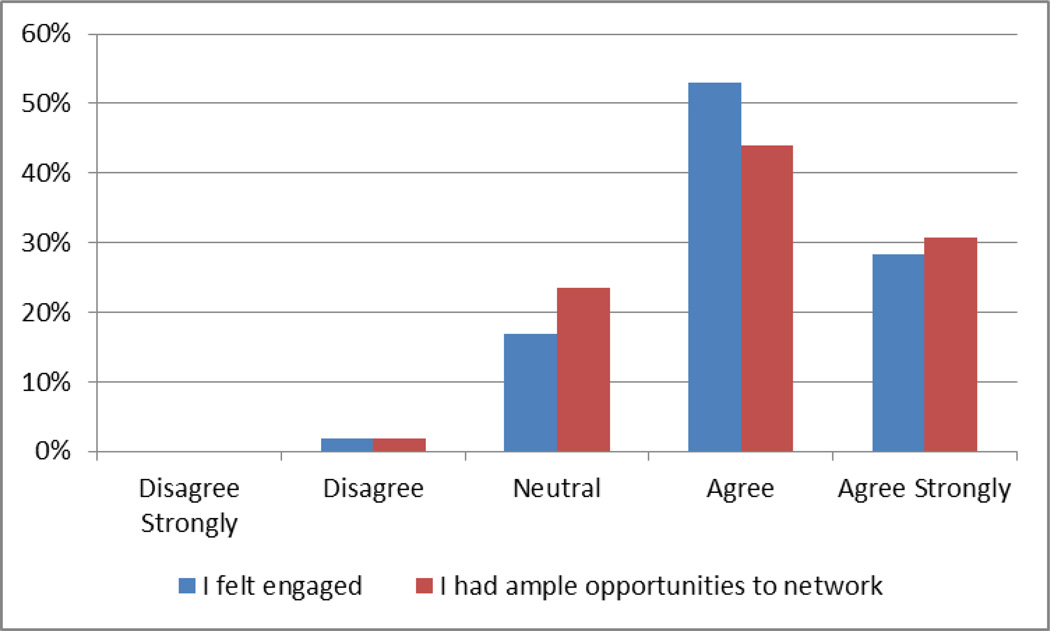

CPIC conference evaluations always include questions about community engagement. For example, out of 65% of kick-off conference attendees who filled out optional conference evaluation forms, roughly four-fifths either “agreed” or “agreed strongly” that they felt engaged throughout the conference and more than 70% either “agreed” or “agreed strongly” that they had ample opportunities to meet and network with other conference participants (see Figure 2). These results suggest a high level of community engagement. The following participant comments also illustrate what conference participants enjoyed the most: “[I enjoyed] interactive approach with client/community participation.” “Warm, friendly organizers and speakers.” “The networking, learning about the study and services available.”2

Figure 2.

Select Kick-Off Conference Evaluation Results (Combined N=166)

Capacity-Building

Besides offering large group presentations and panel discussions, all CPIC conferences use small group hands-on trainings and break-out discussion sessions. A small group format helps increase conference participants’ capacity to address mental health issues, because participants discuss study materials, engage in role playing exercises, and share personal stories. One of the most popular break-out sessions during the kick-off conference was about using Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) to treat depression. Participating agencies received a series of CBT trainings for free before a DMH roll-out of CBT as an evidence-based approach to depression care, which not only helped study agencies increase their capacity, but also stay ahead of their competitors. Moreover, during the kick-off conferences, agency representatives received a CPIC flash drive with all study materials, including depression care toolkits, manuals, forms, and patient education materials.

Shared Project Participation and Ownership

Training on cultural competency for both community and academic partners was offered as part of the first CPIC conferences to ensure productive collaboration. To reinforce the value of community input and shared project ownership, CPIC kick-off conferences integrated role playing activities designed to help community partners learn new information in an easy-to-understand format and increase a sense of project ownership because participants had to start using project materials right after the conference.

Phase II-Valley

The second phase, called Valley, is the intervention phase. 27 While RS agencies only received training in evidence-based approaches for depression care, CEP agencies also collaborated on modifying the intervention and developing a network that can offer depression-related services that go beyond what traditional providers offer. From the academic perspective, this phase is the actual trial, because its results would determine the effectiveness of using CPPR as an implementation approach in depression QI studies. From the community perspective, this is a pilot that would help determine what approach works best for community and therefore is worth implementing in the next study phase.19

Post-Intervention Conference

A post-intervention conference, titled “Hope for Beating Depression in Our Communities: Initial Findings from Community Partners in Care,” was conducted after the RCT to allow all study agencies to share their intervention experiences, reengage the RS partner agencies into the study, learn about collaborative approaches to the analysis and interpretation of baseline client data in ways that are scientifically sound and meaningful to community, and start planning for dissemination (see Table 6). 108 individuals representing both CEP and RS agencies attended this conference (see Table 3). This conference helped ensure community commitment to collaborative data analysis and readiness to disseminate study findings.

Table 6.

Post-Intervention Conference Agenda and Learning Objectives

| Welcome and Introduction to Community Partners in Care |

|

| Panel I: See the Data |

|

| Panel II: Share Perspectives |

|

| Panel III: Plan For the Future |

|

Community Engagement

During conference presentations, CPIC leaders often use metaphors to explain complex scientific concepts. For example, a study leader used a “CPIC Garden” metaphor during the post-intervention conference to illustrate the phases of CPIC. He brought a basket filled with seed packets and gave a packet of seeds to every conference participant. He also identified other study leaders as CPIC gardeners by giving them their own gardening hats. Similar to gardeners who help plants grow by providing water, soil, and fertilizers, CPIC leaders provide study trainings and support to participating agencies. In the Valley phase, the seeds have been planted. In the Victory phase, the planted fruits and vegetables would be harvested and distributed in the community. The experiences of agencies with the highest yield would be studied to develop the most effective strategies of using the study tools. The use of the garden metaphor helped clearly illustrate study phases in plain language free of scientific jargon. This type of common communication reduces barriers between community and academics participants.

Capacity-Building

Conference organizers make sure that enough time is allocated for questions and answers during all sessions, and that the last conference session provides an opportunity for community and academic conference organizers to summarize conference discussions and address any outstanding questions. To build community research capacity, the post-intervention conference, for example, featured a real-time data analysis session. One agency representative was interested in learning about depression among elderly study clients. A CPIC statistician performed basic descriptive analyses to answer this question in front of the audience, projected statistical output on a screen, and helped conference participants interpret the results.

Conference evaluations support joint data analysis as one of the capacity-building activities that community partners find useful: 95% (n=76) of the post-intervention conference participants responded “yes” to a question about whether conference organizers did a good job of building capacity in the community. This question was asked right after the data analysis presentation, and conference attendees used an audience response system to answer it. Overall, comments made by conference attendees suggest that there is a strong need for ongoing capacity-building: “Please continue providing resources to build capacity.” “Continue CBT training for community care partners. “Publish findings and share information with the wider community.” “Join both study arms to enable more individuals to unite for the care of depressed individuals/groups.”

Shared Project Participation and Ownership

Hands-on data analyses sessions conducted during the post-intervention conference helped ensure shared project ownership in two ways. First, by seeing how their colleagues ask questions about client data, conference participants, who may have never had any exposure to scientific research, became more engaged in the scientific process and started asking questions about how CPIC could help identify factors that impact depression, and how study resources could be used to address community needs based on collected evidence. Second, many attendees learned that they could use CPIC results in their own agencies: “We are in the process of integrating primary care with behavioral health services, and the data is [sic] very useful in our planning of ‘where, what, and how’ to better serve our community,” said one conference participant.

Phase III-Victory

The last CPIC phase, called Victory, is the dissemination phase.28 Currently, CPIC partners are in the process of describing and disseminating study findings. Thematic data analysis groups have been formed to facilitate collaborative data interpretation and dissemination. For example, community and academic partners interested in the issue of homelessness are looking at how the intervention affected the level of depression among the homeless population. Partners are preparing manuscripts for submission to academic journals and conferences, as well community-valued outlets, such as community conferences, newsletters, and radio presentations, hoping that study results would lead to policy changes intended to improve the services that depressed clients may need, and ultimately lead to improvements in health outcomes. Moreover, the partnership experiences and study findings are expected to help community and academic partners as they start working on a CPIC follow-up study that was recently funded by the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute and will help continuously engage community around the topic of depression.

Dissemination Conference

The victory phase culminated in a final community-partnered research dissemination conference, titled “How Our Community Can Beat Depression in Los Angeles: Latest CPIC Study Results.” Although the main goals of this conference were to celebrate project accomplishments, present latest study results, and discuss lessons learned, conference organizers emphasized the importance of partnership maintenance and sustainability to ensure continuous provision of evidence-based depression care services, discussed necessary policy changes highlighted by the study findings, and generated ideas for future partnered projects (see Table 7). 116 participants representing different agency types attended this conference (see Table 3).

Table 7.

Dissemination Conference Agenda and Learning Objectives

| Welcome and Introduction to Community Partners in Care |

|

| Panel I: What We Learned from Community Partners in Care |

|

| Panel II: Policy Panel |

|

| Working Lunch |

|

| Panel III: Dissemination Activities & Plans: National Library of Medicine project update |

|

| Panel IV: Dissemination Activities & Plans: Building Resiliency & Increasing Community Hope (B-RICH) Pilot Study Update |

|

Community Engagement

The dissemination conference invited not only CPIC agencies, but also community-based organizations that did not participate in this study, as well as county and federal policy-makers. Conference attendees were greeted by a local Congresswoman who has strong relationships with the community that date back to her work as a Los Angeles grassroots community organizer. To promote a wide use of project findings, conference presenters explained how community partners were engaged in all project phases to illustrate that the interventions were conducted in close collaboration with community, rather than on community. Community and academic partners presented study findings using jargon-free language. Policy-makers discussed how study findings may inform the ongoing healthcare reform and can be used to improve depression care in Los Angeles and other places.

Capacity-Building

During the working lunch, conference participants were asked to think about the implications of CPIC findings for their communities and generate ideas for how this project and other research on depression in Los Angeles should move forward by participating in the “Dreams” exercise. Participants seated around the same table were asked to put their ideas on a sheet of paper, attach it to a string with a balloon, and bring it to the center of the room. Once all balloons were collected, a community partner released them, symbolizing how dreams about the future of depression care are spreading in community so that one day they may become a reality. Our review of ideas suggested by conference participants revealed that there is a need for engaging the faith community, building connections between substance abuse and mental health agencies, helping community deal with stigma associated with depression, training lay healthcare workers on depression, reaching out to local and national media outlets to disseminate CPIC findings, and lobbying for changes in the way agencies are reimbursed for mental health services.

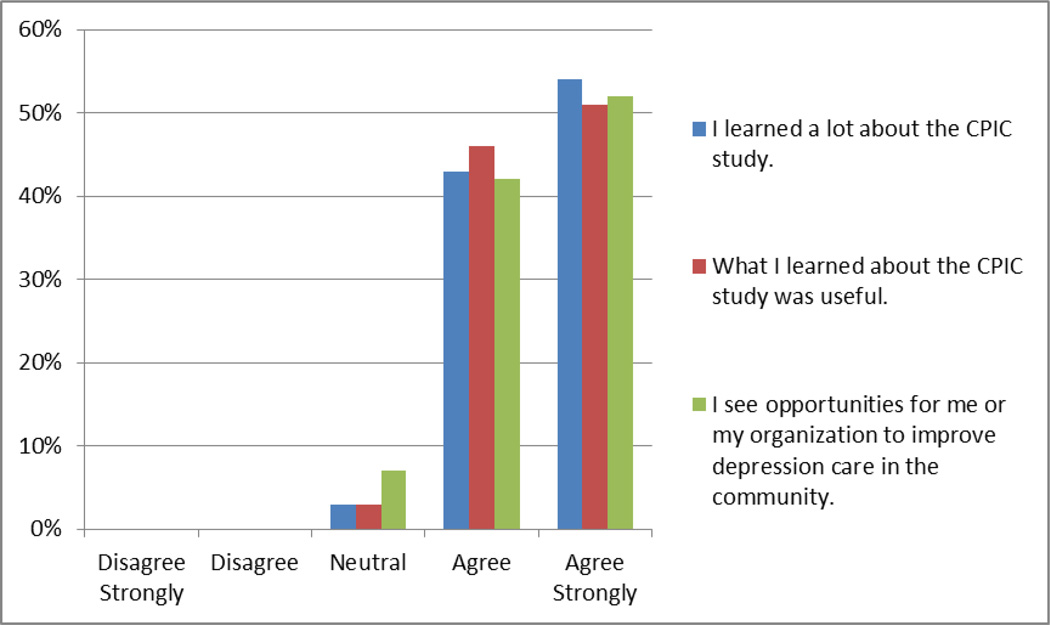

Conference evaluation results suggest that dissemination conference participants felt that what they learned about CPIC during the conference was useful. Indeed, out of 52% of conference attendees who participated in optional conference evaluation, 97% either “agreed” or “agreed strongly” that they have learned a lot about the CPIC study and that this information was useful. Moreover, 94% of participants either “agreed” or “agreed strongly” with the following statement: “I see opportunities for me or my organization to improve depression care in the community” (see Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Select Dissemination Conference Evaluation Results (N=60)

Shared Project Participation and Ownership

Following recommendations in the CBPR literature, 29 study leaders wrote a brief summary of project findings and their policy implications, which was used to discuss CPIC results with county, state, and federal policy-makers not present at the conference. During the dissemination conference, CPIC agencies started building relationships with agencies that were not engaged in the project to promote the dissemination of study findings and ensure its long-term use and impact on policy and subsequent improvement in community health. Finally, the study partners are archiving all CPIC materials in the National Library of Medicine and will make them available to the community at large free of charge.

Conclusions

Community-partnered research conferences are a powerful yet underutilized strategy in scientific research. Our study uses a CPIC example to illustrate how community-partnered research conferences may be integrated into scientific research to help community and academic study leaders reach the goals of community engagement in research, two-way capacity-building, and shared project participation and ownership, which are important for translating research into practice and ensuring its long-term use in community.6 Although additional longitudinal research is needed to validate our descriptive findings, explore their applicability to other settings, such as rural partnerships, and determine their sustainability, our study results suggest that conducting conferences at different project phases may help promote the short-term community benefits, such as depression awareness, ability to see how research results may apply to an individual patient or agency, and learning about evidence-based approaches to treating depression, as well as the long-term benefits, such as future engagement of community members in research, translation of research into practice and policy, and improvement of health outcomes.

Moreover, the main contribution of this study is that our model describes various features of community-partnered research conferences and explains the mechanisms through which they may help increase community participation in interventions and research activities. We argue that for community-partnered research conferences to be effective, they should be free and widely advertised; study leaders should use community-engagement activities and choose conference topics that address community needs. Community capacity to deal with pressing health issues may be increased if conferences combine lectures and hands-on activities, conference materials are distributed free of charge and translated into other languages, if needed, coaching on data analysis and other research activities is offered, and training on how to use study data for improving agency quality of services is provided. Finally, refraining from using scientific jargon during conferences, clearly addressing community questions and concerns, engaging community partners in summarizing policy implications of study findings, and co-presenting study findings in community-valued venues may help increase shared project participation and ownership.

References

- 1.Jones L, Collins BE. Participation in action: the Healthy African American Families community conference model. Ethn Dis. Winter. 2010;20(1 Suppl 2) S2-S15-20. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mendel P, Ngo VK, Dixon E, et al. Partnered evaluation of a community engagement intervention: Use of a kickoff conference in a randomized trial for depression care improvement in underserved communities. Ethn Dis. 2011 Summer;21 S1-78-S71-88. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Suarez JI, LeRoux PD. The First Neurocritical Care Research Conference: A Great Starting Point. Neurocritical care. 2012;16(1):4–5. doi: 10.1007/s12028-011-9614-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lucky D, Turner B, Hall M, Lefaver S, de Werk A. Blood pressure screenings through community nursing health fairs: motivating individuals to seek health care follow-up. J Community Health Nurs. 2011;28(3):119–129. doi: 10.1080/07370016.2011.588589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Khodyakov D, Sharif MZ, Dixon E, et al. An implementation evaluation of the community engagement and planning intervention in the CPIC depression care improvement trial. Community Ment Health J. doi: 10.1007/s10597-012-9586-y. In Press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cargo M, Mercer SL. The Value and Challenges of Participatory Research: Strengthening Its Practice. Annu Rev Public Health. 2008;29:325–350. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.29.091307.083824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brown P, Morello-Frosch R, Brody J, et al. Institutional review board challenges related to community-based participatory research on human exposure to environmental toxins: A case study. Environmental Health. 2010;9(1):39. doi: 10.1186/1476-069X-9-39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Levin JL, Doyle EI, Gilmore KH, Wickman AJ, Nonnenmann MW, Huff SD. Cultural Effectiveness in Research: A Summary Report of a Panel Session Entitled “Engaging Populations at Risk”. Journal of Agromedicine. 2009;14(4):390–399. doi: 10.1080/10599240903266508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Marcus MT, Taylor WC, Hormann MD, Walker T, Carroll D. Linking service-learning with community-based participatory research: An interprofessional course for health professional students. Nurs Outlook. 2011;59(1):47–54. doi: 10.1016/j.outlook.2010.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dalal M, Skeete R, Yeo HL, Lucas GI, Rosenthal MS. A Physician Team's Experiences in Community-Based Participatory Research: Insights into Effective Group Collaborations. Am J Prev Med. 2009;37(6):S288–S291. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2009.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Milam AJ, Bone L, Furr-Holden D, et al. Mobilizing for Policy: Using Community-Based Participatory Research to Impose Minimum Packaging Requirements on Small Cigars. Prog Community Health Partnersh. 2012;6(2):205–212. doi: 10.1353/cpr.2012.0027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Salihu HM, August EM, Alio AP, Jeffers D, Austin D, Berry E. Community-academic partnerships to reduce black-white disparities in infant mortality in Florida. Prog Community Health Partnersh. 2011;5(1):53–66. doi: 10.1353/cpr.2011.0009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Javier JR, Chamberlain LJ, Rivera KK, Gonzalez SE, Mendoza FS, Huffman LC. Lessons learned from a community-academic partnership addressing adolescent pregnancy prevention in Filipino American families. Prog Community Health Partnersh. 2010;4(4):305–313. doi: 10.1353/cpr.2010.0023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Travers R, Wilson M, McKay C, et al. Increasing Accessibility for Community Participants at Academic Conferences. Prog Community Health Partnersh. 2008;2(3):257–263. doi: 10.1353/cpr.0.0033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Katz ML, Pennell ML, Dignan MB, Paskett ED. Assessment of Cancer Education Seminars for Appalachian Populations. J Cancer Educ. 2011:1–7. doi: 10.1007/s13187-011-0291-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Glasgow RE, Emmons KM. How can we increase translation of research into practice? Types of evidence needed. Annu Rev Public Health. 2007;28:413–433. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.28.021406.144145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tumiel-Berhalter LM, Mclaughlin-Diaz V, Vena J, Crespo CJ. Building community research capacity: process evaluation of community training and education in a community-based participatory research program serving a predominately Puerto Rican community. Prog Community Health Partnersh. 2007;1(1):89–97. doi: 10.1353/cpr.0.0008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wells K, Sherbourne C, Schoenbaum M, et al. Impact of disseminating quality improvement programs for depression in managed primary care: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2000;283(2):212–220. doi: 10.1001/jama.283.2.212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chung B, Jones L, Dixon EL, Miranda J, Wells K. Using a Community Partnered Participatory Research Approach to Implement a Randomized Controlled Trial: Planning the Design of Community Partners in Care. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2010;21(3):780–795. doi: 10.1353/hpu.0.0345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Khodyakov D, Mendel P, Dixon E, Jones A, Masongsong Z, Wells K. Community Partners in Care: Leveraging Community Diversity to Improve Depression Care for Underserved Populations. International Journal of Diversity in Organisations, Communities and Nations. 2009;9(2):167–182. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jones L. Preface: Community-partnered participatory research: how we can work together to improve community health. Ethn Dis. Autumn. 2009;19(4 Suppl 6) S6-1-2. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Judd J, Frankish CJ, Moulton G. Setting standards in the evaluation of community-based health promotion programmes—a unifying approach. Health Promotion International. 2001;16(4):367–380. doi: 10.1093/heapro/16.4.367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jones L, Meade B, Norris K, et al. Develop a vision. Ethn Dis. 2009;19(4) S6-17-S16-30. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Aarons GA, Wells RS, Zagursky K, Fettes DL, Palinkas LA. Implementing evidence-based practice in community mental health agencies: A multiple stakeholder analysis. Am J Public Health. 2009;99(11):2087–2095. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.161711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Planas LG. Intervention design, implementation, and evaluation. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2008;65:1854–1863. doi: 10.2146/ajhp070366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chung B, Jones L, Terry C, Jones A, Forge N, Norris KC. Story of Stone Soup: a recipe to improve health disparities. Ethn Dis. 2010;20(1 Suppl 2):9–14. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jones L, Meade B, Koegel P, et al. Work through the valley: Plan. Ethn Dis. 2009;19(4) S6-31-S36-38. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jones L, Wells K, Meade B. Celebrate victory. Ethn Dis. 2009;19(4) S6-59-S56-71. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Izumi BT, Schulz AJ, Israel BA, et al. The one-pager: A practical policy advocacy tool for translating community-based participatory research into action. Prog Community Health Partnersh. 2010;4(2):141–147. doi: 10.1353/cpr.0.0114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]