Abstract

The photoelectrical properties of multilayer WS2 nanoflakes including field-effect, photosensitive and gas sensing are comprehensively and systematically studied. The transistors perform an n-type behavior with electron mobility of 12 cm2/Vs and exhibit high photosensitive characteristics with response time (τ) of <20 ms, photo-responsivity (Rλ) of 5.7 A/W and external quantum efficiency (EQE) of 1118%. In addition, charge transfer can appear between the multilayer WS2 nanoflakes and the physical-adsorbed gas molecules, greatly influencing the photoelectrical properties of our devices. The ethanol and NH3 molecules can serve as electron donors to enhance the Rλ and EQE significantly. Under the NH3 atmosphere, the maximum Rλ and EQE can even reach 884 A/W and 1.7 × 105%, respectively. This work demonstrates that multilayer WS2 nanoflakes possess important potential for applications in field-effect transistors, highly sensitive photodetectors, and gas sensors, and it will open new way to develop two-dimensional (2D) WS2-based optoelectronics.

Graphene, the monolayer counterpart of graphite, has attracted extensive attention in recent years because of its unusual electrical, optical, magnetic and mechanical properties1,2,3,4. It displays an exceptionally high carrier mobility exceeding 106 cm2 V−1 s−1 at 2 K and 15000 cm2 V−1 s−1 at room temperature5,6, and the linear dispersion of the Dirac electrons near the K point makes graphene be used as photodetector with high operation frequencies7 and ultrawide band operation8. However, the zero bandgap of graphene limits its applications in optoelectronics, for example, field-effect transistors (FETs) based on graphene cannot be effectively switched off due to the high OFF-currents. In contrast, 2D transition metal dichalcogenides (TMDCs) with chemical formula MX2 (M = Mo, W, Ga, etc. and X = S, Se or Te) possess sizable bandgaps9,10 around 1–2 eV, which attracted widely interest due to their interesting physical properties and applications in nanoelectronics, sensing and photonics11,12,13,14,15,16. Particularly, the 2D TMDCs based FETs, photodetectors and gas sensors have been extensively studied. As one earliest TMDCs used in FETs, WSe2 crystal17 shows high mobility (>500 cm2 V−1 s−1), ambipolar behavior and 104 on/off ratio at 60 K. Afterwards, mono or few-layer MoS2 FETs with a back-gated18 and top-gated configuration19 are reported to exhibit an excellent on/off ratio (~108) and room-temperature mobility of > 200 cm2 V−1 s−1. Although the high photodetection performance, several problems such as very low responsivity (~10−2 A/W) and external quantum efficiency (0.1–0.2%) still remain with graphene photodetectors20,21. Compared to graphene-based devices, photodetectors made from TMDCs thin layers can exhibit enhanced responsivity and selectivity. For example, a few-layer MoS2 photodetector is demonstrated with improved responsivity (0.57 A/W) and fast photoresponse11 (~70–110 μs), and the monolayer MoS2-based devices22 show a maximum photoresponsivity of 880 A/W. Recently, 2D GaS and GaSe thin nanosheets are also reported as high performance photodetectors13,14,23,24. Moreover, TMDCs suggest opportunities in molecular sensing applications due to the high surface-to-volume ratio. For instance, single and few-layer MoS2 sheets have been demonstrated to be sensitive detectors for NO, NO2, NH3 and triethylamine gas25,26,27,28. The detection mechanism is probably due to the n-doping or p-doping induced by the adsorbed gas molecular, changing the resistivity of the intrinsically n-doped MoS2. However, as a typical member of 2D TMDCs materials, WS2 thin layers are less studied on their photoelectrical properties. Particularly, no research has been reported for the potential application of WS2 in photodetector and gas sensors. Actually, WS2 possesses some advantages compared to MoS2. For example, MoS2 is usually procured from natural sources with no control over contaminations. WS2 exhibits higher thermal stability29 and wider operation temperature range as lubricants30. A recent calculation also shows that single layer WS2 has the potential to outperform other 2D crystals in FETs applications due to its favorable bandstructure31, and the transistors based on chemically synthesized layered WS2 is also reported to exhibit 105 room temperature modulation and ambipolar behavior32.

In this paper, multilayer WS2 nanoflakes are exfoliated from the commercially available WS2 crystals (Lamellae Co.) onto 300 nm SiO2/Si substrates using conventional mechanical exfoliation technique. The multilayer WS2 nanoflakes transistors show excellent field-effect properties with a high electron mobility of 12 cm2/Vs and high sensitive to red light (633 nm) with Rλ (defined as the photocurrent generated per unit power of the incident light on the effective area) of 5.7 A/W and high EQE (defined as the number of photo-induced carriers detected per incident photons) of 1118%, indicating the 2D WS2 will be a new promising material for high performance photodetectors. Moreover, the sensing of various gas molecules on this transistor is preliminary investigated for the first time. We find strong response upon exposure to reducing gas of ethanol and NH3, which can serve as electron donors, enhancing n-type and conductivity of WS2 nanoflakes. On the contrary, the oxidizing gas of oxygen can act as electron acceptors to withdraw substantial electrons from the WS2 nanoflakes, depleting its n-type and reducing the conductivity. We also observe the enhanced Rλ and prolonged response to the reducing gas, caused by temporary charge perturbation in the WS2 nanoflakes from the adsorbed electron donors. Remarkably, the maximum Rλ of the device can reach 884 A/W under light illumination of 50 μW/cm2 at the NH3 atmosphere, which is 106 times higher than the first graphene-based photodetectors7 and 105 times higher than previous reports for monolayer MoS2 phototransistors33. Here, the excellent electrical, photosensitive and gas sensing properties of the multilayer WS2 nanoflakes transistors are studied systematically, suggesting great potential practical applications in FETs, photodetectors and gas sensors.

Results

Characterization of multilayer WS2 nanoflakes

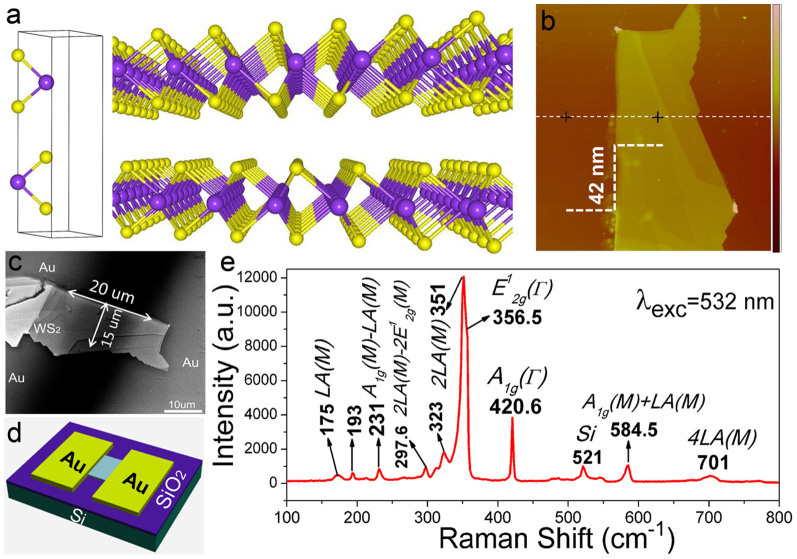

Bulk WS2 is an indirect-bandgap (1.4 eV) semiconductor, but can turn into a direct-bandgap (2.1 eV) material when exfoliated into the monolayer state34. Each single plane of WS2 comprises a trilayer composed of a tungsten layer sandwiched between two sulfur layers in a trigonal prismatic coordination as shown in Figure 1a. The multilayer WS2 nanoflakes based transistors were fabricated with a coplanar electrode geometry by “gold-wire mask moving” technique35,36. Through the AFM (Figure 1b and Figure S1) and SEM (Figure 1c) images of actual devices with SiO2 as bottom gating, the thickness of the WS2 nanoflakes is about 42 nm, and the width and length of the channel are 20 μm and 15 μm, respectively. Figure 1d shows the schematic diagram of the device. EDX (Figure S2) results indicate the existence of S and W elements with an atom ratio of 2 in the WS2 nanoflakes.

Figure 1. Characterization of the multilayer WS2 nanoflakes.

(a) Primitive cell and three-dimensional schematic representation of a typical WS2 structure with the sulfur atoms in yellow and the tungsten atoms in purple. Atomic force microscopy (AFM) image (b) and scanning electron microscopy (SEM) image (c) of the actual transistor based on multilayer WS2 nanoflakes. (d) Schematic diagram of the device. The thickness of WS2 nanoflakes is 42 nm. The width (W) and length (L) of the channel in the device is 15 μm and 20 μm, respectively. (e) Room-temperature Raman spectrum from the multilayer WS2 nanoflakes, using the 532 nm laser.

The first-order Raman spectra of the WS2 nanoflakes showed two optical phonon modes at the Brillouin zone center (E12g(Γ) and A1g(Γ)) and one longitudinal acoustic mode at the M point (LA(M)). E12g(Γ) was an in-plane optical mode, A1g(Γ) corresponded to out-of-plane vibrations of the sulfur atoms, and the longitudinal acoustic phonons LA(M) were in-plane collective movements of the atoms (Figure S3). Raman spectra of the WS2 nanoflakes were performed with the 532 nm laser excitations (Figure 1e). The first-order Raman peaks are identified at 175, 356.5 and 420.6 cm−1, which are attributed to the LA(M), E12g(Γ) and A1g(Γ) modes, respectively. Additional peaks correspond to the second-order Raman modes which are multiphonon combinations of these first-order modes. Our Raman results for the multilayer WS2 nanoflakes agree well with the previous reports37,38,39.

Electrical properties under dark and light illumination

Owing to the lack of dangling bonds, structural stability and high mobility40, 2D TMDCs were promising materials for FETs. To evaluate the electrical performance of the multilayer WS2 nanoflakes, the bottom-gated transistors on SiO2/Si were fabricated. Figure 2a and 2b show the typical output and transfer characteristics respectively, performing an n-type behavior. According to the previous reports41,42, in the case of VG > VT and |VDS| ≪ |VG − VT|, the FETs are turned on. The positive gate voltage (VG) can induce large amounts of electrons in the interfaces between the WS2 nanoflakes and SiO2 substrate, and a conducting channel is created which allows the current to flow between the source and drain. The FETs operate like a resistor and work at linear region, thus the source-drain current (IDS) can linearly depend of source-drain voltage (VDS) as shown in the inset of Figure 2a. In this case, the IDS and VDS can satisfy the formula  , where L is channel length (20 μm), W is channel width (15 μm), and Ci is the gate capacitance which can be given by equation Ci = εoεr/d, εo (8.85 × 10−12 F/m) is vacuum dielectric constant, and εr (3.9) and d (300 nm) are dielectric constant and thickness of SiO2, respectively. The field-effect carrier mobility (μ) and threshold voltage (VT) of WS2 nanoflakes based FETs can be calculated from the linear region of the output properties by supplying the values of IDS and VDS at different VG into the above equation. We get that VT = −3.5 V, and the electrons mobility is up to 12 cm2/Vs. To estimate the intrinsic doping level of the prepared WS2 nanoflakes, IDS at zero VG was modeled as

, where L is channel length (20 μm), W is channel width (15 μm), and Ci is the gate capacitance which can be given by equation Ci = εoεr/d, εo (8.85 × 10−12 F/m) is vacuum dielectric constant, and εr (3.9) and d (300 nm) are dielectric constant and thickness of SiO2, respectively. The field-effect carrier mobility (μ) and threshold voltage (VT) of WS2 nanoflakes based FETs can be calculated from the linear region of the output properties by supplying the values of IDS and VDS at different VG into the above equation. We get that VT = −3.5 V, and the electrons mobility is up to 12 cm2/Vs. To estimate the intrinsic doping level of the prepared WS2 nanoflakes, IDS at zero VG was modeled as  , where n2D is the 2D carrier concentration, q is the electron charge. From the output characteristics of WS2 nanoflakes (Figure 2a), n2D is extracted to be ~1.4 × 1011 cm−2. We have also performed Hall-effect measurements with four-probes on the WS2 nanoflakes to accurately determine μ and n2D, and the results are very similar with the field-effect μ and n2D (Figure S4).

, where n2D is the 2D carrier concentration, q is the electron charge. From the output characteristics of WS2 nanoflakes (Figure 2a), n2D is extracted to be ~1.4 × 1011 cm−2. We have also performed Hall-effect measurements with four-probes on the WS2 nanoflakes to accurately determine μ and n2D, and the results are very similar with the field-effect μ and n2D (Figure S4).

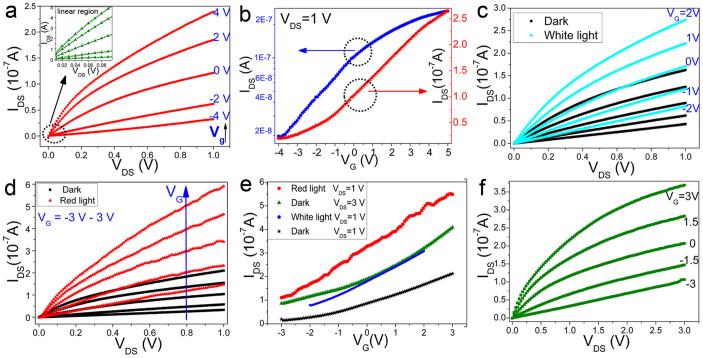

Figure 2. Field effect of the multilayer WS2 nanoflakes.

(a) Output characteristics of the transistor based on multilayer WS2 nanoflakes using Au/Au as the drain/source electrodes. The inset is linear region at low source drain voltage. (b) Transfer characteristics of the device at a fixed VDS of 1 V on a log scale (left y axis) and on a linear scale (right y axis). All measurements were performed in air at room temperature with the absence of light. Output characteristics of the device with (c) white light (15 mW/cm2) from LEDs and (d) red light (633 nm, 15 mW/cm2) from red lasers. (e) Transfer characteristics of the devices in dark and under light illumination. (f) Output characteristics of the devices in dark with VDS ranging from 0 to 3 V.

The multilayer WS2 nanoflakes FETs were also illuminated with white light from LED and red light from red laser, and the output characteristics of the devices are shown in Figure 2c and 2d, respectively. The transfer characteristic curves under dark and light are shown in Figure 2e. The curves are obviously improved under both white and red light illumination, indicating the photosensitive property to the visible light. As discussed above, our prepared WS2 nanoflakes perform n-type behavior with an intrinsic density of electrons of about 1.4 × 1011 cm−2. The carriers density can be modulated by supplying the electrical gating, which can be explained simply using the parallel-plate capacitor model. When positive VG is added on the bottom of dielectric (SiO2), much electrons will be induced in the interface between WS2 nanoflakes and SiO2, serving as conductive channel and increasing the drain current. In contrast, negative VG will deplete the electrons in the interface and reduce the drain current. In addition, the increased VDS can increase the carrier drift velocity and reduce the carrier transit time Tt (defined as Tt = L2/μVDS), thus contributing to the increased drain current (Figure 2e and 2f). Table 1 show the VT, μ and n2D under dark and light illumination for the multilayer WS2 nanoflakes, which are extracted from the linear region of output characteristics. We found that the absolute values of VT, μ and n2D are all increased under light illumination. The photo-generated carriers contribute to the increased electrons density resulting in that larger negative voltage is needed to deplete them. The electron mobility (μ) can be obtained from the equation  , the source drain current IDS and current change between ON and OFF states are increased under light illumination, leading to the increased slope of

, the source drain current IDS and current change between ON and OFF states are increased under light illumination, leading to the increased slope of  , and hence enhancing the calculated mobility.

, and hence enhancing the calculated mobility.

Table 1. Threshold voltage (VT), electron mobility (μ), and density of electrons (n2D) of a typical transistor under dark and light illumination.

| Parameters | VT (V) | μ (cm2/Vs) | n2D (1010 cm-2) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dark | −3.5 | 12 | 9.4 |

| White light | −3.6 | 19.7 | 11 |

| Red light | −4 | 25 | 17 |

Photodetector based on WS2 nanoflakes

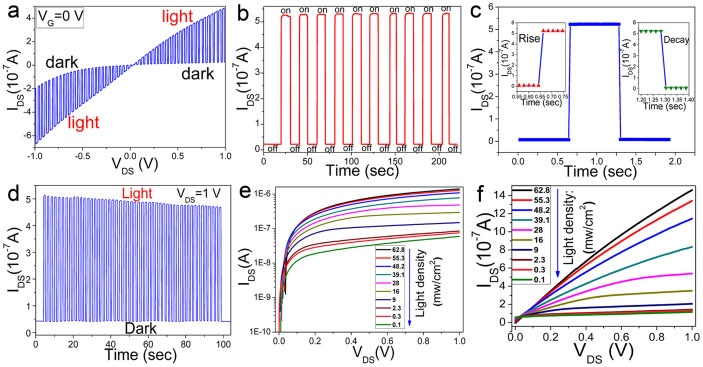

Few- or monolayer MoS2 was demonstrated as ultrasensitive photodetectors based on the previous reports11,22,43. In contrast to the widely studied MoS2 used for photodetectors, little attention has been paid to the 2D WS2. According to the above analysis, the multilayer WS2 nanoflakes can response to the visible light especially the red light with 633 nm since the energy of the red light approximates the band gap of WS2. Therefore, the photosensitive properties of the WS2 nanoflakes based photodetctors for the red light was measured systematically. Figure 3a shows the output characteristics under chopped red light irradiation with zero VG. The drain current can be modulated rapidly by the chopped light, and the current is significantly increased under the light irradiation compared to that in dark, implying a quick response to red light. As shown in Figure 3b, with light irradiation on/off, the device can work between low and high impedance states fast and reversibly with an on/off ratio (defined as Iphoto/Idark) of 25, allowing the device to act as a high quality photosensitive switch. The device also exhibits very fast dynamic response for both rise and decay process (Figure 3c), the response and recovery time is shorter than the detection limit of our measurement setup (20 ms), which is shorter than values for phototransistors based on monolayer MoS2 and hybrid graphene quantum dot22,44, and it is also orders of magnitude shorter than the amorphous oxide semiconductors phototransistors45. Stability test of photo-switching behavior of the WS2 nanoflakes is also performed by switching the light on/off quickly and repetitively, accordingly the photocurrent of the device can change instantly between “ON” state and “OFF” state (Figure 3d). After hundreds of cycles, the photocurrent can still change with light switching on/off, displaying a high reversibility and stability of the device. Figure 3e shows the output characteristics under different light illumination densities. When the WS2 nanoflakes absorb the incident photons, large amounts of electron-pairs generate, forming like a conductive channel, and then being extracted by VDS to form the photocurrent. With increasing light density, the photocurrent is increased significantly. From the “output” characteristics shown in Figure 3f, our phototransistor can be open by the incident light of about 10 mW/cm2. So, like the electrical field effect, the incident light field can also act as a “gating” to modulate the density of carries in the source drain channel and make important effect on the electrical properties of the device.

Figure 3. The performance of the multilayer WS2 nanoflakes as photodetector.

(a) Drain-source (IDS-VDS) characteristic of the device based on the WS2 nanoflakes under the chopped red light illumination (633 nm, 30 mW/cm2). (b) Time-dependent photocurrent response during the light switching on/off at source drain voltage of 1.0 V. (c) Dynamic response characteristic of the device. The inset is corresponding to the rise (left) and decay (right) process. (d) Stability test of photo-switching behavior of the device with light switching on/off quickly and repetitively. (e) Source-drain (IDS-VDS) characteristics of the device under different incident optical power density from 0.1 to 62.8 mW/cm2 on a log scale. (f) “Output” characteristics of the device with light as “gating”.

Gas sensing and its effect on photoresponse

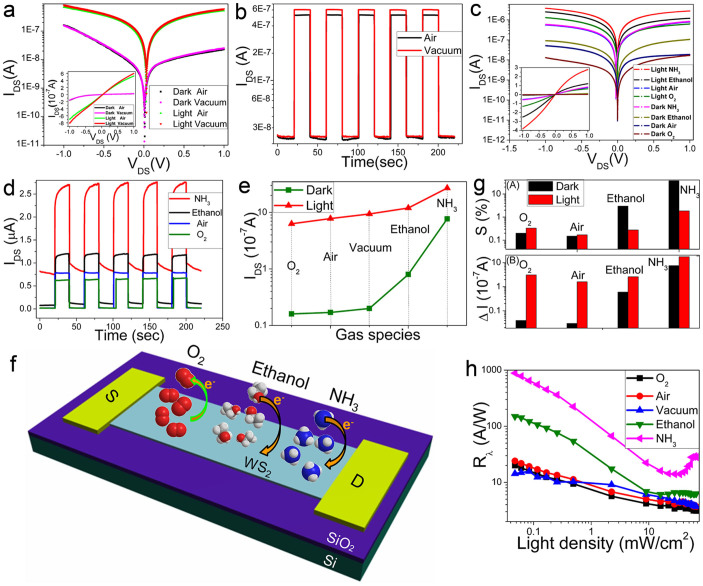

Previous reports showed that the photoelectrical response properties were strongly affected by gas environment for the MoS2 monolayer-based phototransistors43. We also performed the photosensitive measurements of our devices in ambient air and under vacuum. The drain current under vacuum is higher than that in ambient air under both dark and light (Figure 4a), and the increment of current is more obvious under light illumination shown in the inset. Moreover, the photosensitivity is also enhanced under vacuum (Figure 4b). Density functional theory (DFT) calculations12 discover that the O2 and H2O molecules can interact weakly to the TMDCs monolayer with binding energies ranging from 70 to 140 meV and substantial electrons can transfer into the physical-adsorbed gas molecules from the semiconductors. Large amounts of O2 and H2O molecules exist in air and the WS2 nanoflakes display n-type behavior from the above Hall and field-effect results. In our case, O2 and H2O molecules in ambient air can be physically adsorbed on the surface of the WS2 nanoflakes and withdraw numerous electrons from WS2, depleting the n-type of WS2 nanoflakes. Thus the resistance becomes larger due to the reduction of major conduction electrons, corresponding to the reduced IDS. Upon light illumination in air, much electron-hole pairs generate and the density of electrons in the WS2 nanoflakes is improved as discussed above. O2 and H2O molecules as electron acceptors will have more electrons to accept, corresponding to more gas molecules in ambient can be adsorbed and deplete more electrons, leading to the decreased photosensitivity. Moreover, the photocurrent shows a strong dependence on light intensity and the experimental data are fitted by a power equation Iph = aPα, where a is scaling constant, and α is exponent. Under vacuum, the photocurrent displays a power dependence of ~0.91 (function: Iph = 0.26P0.91) as shown in Figure S5a, indicating a superior photocurrent capability and a high efficiency of photo-generated charge carriers from the absorbed photons. However, the exponent α in air (function: Iph = 0.52P0.73) shown in Figure S5b is smaller than that under vacuum, indicating the route of the loss of the photo-exited carrier by the adsorbed O2 or H2O molecules in air. Similar phenomenon is also observed in MoS2-based phototransistor43.

Figure 4. Gas sensing and its effect on photoresponse.

(a) IDS-VDS characteristics (on a log scale of y-axis) of the WS2 nanoflakes photodetectors under dark or in the presence of light (633 nm, 30 mW/cm2) measured in air and in vacuum. The insert is corresponding curve on a linear scale of y axis. (b) Time-dependent photocurrent response under air and vacuum during the light switching on/off. (c) IDS-VDS characteristics (on a log scale of y-axis) of the device under dark or in the presence of light (633 nm, 40 mW/cm2) measured in various gas atmospheres. The inset is corresponding curves on a linear scale of y axis. (d) Time-dependent photocurrent response under various gas atmospheres. (e) The extracted dark current and photocurrent under different gas atmospheres. (f) Schematic diagram of charge transfer process between adsorbed gas molecules and the multilayer WS2 nanoflakes transistor. (g) The gas sensitivity (A) (defined as S = |(Igas − Ivacuum)/Ivacuum|) and current change (B) (defined as ΔI = |Igas − Ivacuum|) under different conditions. (h) The photo-responsivity Rλ under various gas atmospheres, showing high sensitivity. The device exhibits a maximum Rλ of 884 A/W with low light density of 50 μW/cm2.

To further investigate the gas effect on the electrical and photosensitive properties of the multilayer WS2 nanoflakes, the devices were placed in various gas environments during photoelectrical measurements. From the IDS − VDS characteristics (Figure 4c) and time-dependent photocurrent response at various gas atmospheres during the light switching on/off (Figure 4d), the WS2 nanoflakes can obviously response to the given gas molecules which play an important and different roles in the conductivity and photosensitive properties of the devices. Figure 4e summarizes the drain current under these gas molecules both in dark and under light illumination, the drain current of the device is decreased in O2 and air, but increased in ethanol and NH3, compared to that under vacuum. The current change is considered to result from the charge transfer between the WS2 nanoflakes and the adsorbed gas molecules as shown in Figure 4f. Once the vapor molecules come into contact with the surface of WS2, the gas molecule is expected to be adsorbed and subsequently change the charge carrier distribution in WS2 nanoflakes. O2 molecules can act as electron acceptors to accept electrons from WS2, leading to a reduction in overall conductivity. In contrast, ethanol and NH3 molecules, serving as electron donors, can donate electrons to the WS2 nanoflakes, which enhance the total conducting electrons density, resulting in the increased current. The gas sensitivity is defined as S = |(Igas − Ivacuum)/Ivacuum|, where Igas is current of the device in target gas, and Ivacuum is current under vacuum, VDS are 1 V. Figure 4g (A) shows the gas sensitivity of the device under different gas molecules. S is negative higher in O2 than that in air, because of the higher concentration of O2 acting as electron acceptor to deplete electrons. On the contrary, the ethanol and NH3 molecules can act as electron donors to increase electrons in WS2, displaying a positive S. Particularly, the sensitivity of NH3 is much higher than that of other gas molecules, indicating the WS2 nanoflakes are more sensitive to NH3. Interestingly, we notice that the gas sensitivity of ethanol and NH3 measured in dark is higher than that under light, but lower for O2 and ambient air, the possible reason has been described in Supporting Information. In addition, the current change ΔI caused by gas adsorption represents the amounts of adsorbed gas molecules to some extent shown in Figure 4g (B). Obviously, both oxidizing (O2) and reducing (NH3, ethanol) gas molecules are easier to be adsorbed in the WS2 nanoflakes under light illumination compared to under dark, ascribed to the redundant photo-excited electrons or holes.

Furthermore, the exponent α in O2 (I ~ P0.62, Figure S6a) becomes very small, indicating the photo-excited carriers are continuously consumed by the adsorbed O2 molecules with increasing light density. However, in ethanol (I ~ P1.02, Figure S6b) and NH3 (I ~ P2.5, Figure S6c), the α is significantly enhanced, implying a high efficiency of photo-generated charge carriers, attributed to that more reducing gas (ethanol or NH3) molecules can be adsorbed with increasing incident light density and more electrons can transfer from these adsorbates into the device. Thus, two physical processes upon light illumination including generation of photo-excited electrons and charge transfer from the adsorbed gas molecules can lead to the enhanced charge carrier density, demonstrating a high efficiency of photo-generated carriers. Figure 4h shows the Rλ acquired at different light power densities. At low illumination power density (50 μW/cm2) under NH3 atmosphere, the device reaches a high Rλ of 884 A/W and EQE of 1.7 × 105 %. The Rλ shows a monotonous decrease with increasing illumination intensity due to the saturation of trap states in the WS2 nanoflakes, which is similar with the MoS2-based photodetectors22. While, at high light powers under the ethanol and NH3 atmosphere, the Rλ presents a slight increase trend with increasing illumination intensity, further confirming that more reducing gas molecules can be adsorbed and transfer more electrons into the device under high illumination power. Moreover, the presence of gas molecules can also affect the dynamic response of the device, which is discussed in detail in Supporting Information (Figure S7). Briefly, unlike the single exponential formula for fitting the rise and fall photocurrent in other reports14,46, the dynamic response for rise and fall in our device under the reducing atmosphere (ethanol and NH3) can be perfectly fitted by double exponential formula, further indicating the existence of two physical mechanisms including rapid generation or recombination of photo-excited electron-hole pairs and gas adsorption or charge transfer process in the dynamic response to the light switching on/off.

Discussion

Based on the above experimental results, the multilayer WS2 nanoflakes exhibit n-type behavior with relatively large electron mobility of 12 cm2/Vs, which is much higher than the CVD-grown monolayer WS2 (μ = 0.01 cm2/Vs) by three orders of magnitude47 and comparable to the widely studied few- or monolayer MoS2 (μ = 0.1–10 cm2/Vs) fabricated without high-κ dielectrics19,47,48, but smaller than the top-gated transistors based on the monolayer MoS2 (>200 cm2/Vs) and WSe2 (~250 cm2/Vs) with high κ-dielectrics which are studied more recently19,49. According to the previous reports50,51,52,53, the mobility could be improved significantly by deposition of high-κ dielectric, such as HfO2 (εr = 19), on the top of 2D materials (graphene or TMDCs) owing to dielectric screening of coulomb scattering on charged impurities. The contact resistance or Schottky barrier could also influence the mobility extraction, and the low contact resistance would enhance the driven current and the electrons mobility by selecting the metal electrode with appropriate work function15. However, in our device, Schottky barrier existed in the Au-WS2 contacts from the non-linear characteristics of output curve. Thus, there is incredible room for improving the mobility of WS2 nanoflakes FETs by using high-k dielectric and optimizing the contact fabrication. Besides, the multilayer WS2 nanoflakes FTEs display very small on/off ratio of only 13 times, ascribed to the high off-state current which is attributed to the large thickness of our WS2 nanoflakes. It is predicted that mono-or few-layer WS2 would exhibit high field-effect on/off ratio through reducing the off-state current. Therefore, we also fabricated few-layer WS2 based FETs (Figure S8a). Through the transfer and output characteristics (Figure S8b–c), the few-layer WS2 FETs exhibit ambipolar properties, the electron and hole mobility are calculated to be 0.47 and 0.79 cm2/Vs, respectively, and the on/off ratio is significantly improved to be >104 attributed to the very low off-state current (10−11 A) which agrees well with our conjecture. Such results are different and showed higher on/off ratio but lower mobility of few-layer WS2 compared to the multilayer WS2 nanoflakes. Further study about the optoelectronic properties of few-layer WS2 TETs is necessary for the next step.

As discussed above, the incident light field like the electrical field can also modulate the density of carries in the source drain channel and make the multilayer WS2 nanoflakes be used as ultrasensitive photodetectors with switching on/off ratio of 25 and fast response time of 20 ms. Rλ and EQE are critical parameters for evaluating the quality of photodetctors and large value of Rλ and EQE corresponds to high light-sensibility. Rλ and EQE can be expressed as Rλ = Iph/PS and EQE = hcRλ/eλ, where Iph is the photo-excited current; P is the light power intensity; S is the effective illumination area; h is Planck's constant; c is the velocity of light; e is electron charge; and λ is the excitation wavelength. From our experimental results, under light irradiation (633 nm) of 30 mW/cm2 with VDS of 1 V, the Rλ and EQE are calculated to be 5.7 A/W and 1118%, respectively, which are three orders of magnitude larger than the photodetectors reported for graphene or single-layer MoS27,33, and even comparable to the reported GaSe and GaS-based photodetctors13,14. The high Rλ and EQE are due to a high surface ratio which causes an efficient adsorption of photons. All of the optoelectronic parameters have been compared with those of other 2D materials (Table S1), demonstrating that the multilayer WS2 nanoflakes have great potential in optoelectronics and highly sensitive photodetectors.

Some theoretical calculations and experimental results about the gas sensing of graphene and MoS2-based transistors have been reported to demonstrate high sensitive to various gases, and it is pointed out that O2 and H2O can act as electron acceptors, whereas NH3 and ethanol are donors27,54,55,56,57. In our case, the WS2 nanoflakes transistors can also response to these given gas molecules. The source drain current of the device is decreased in O2 and air and increased in ethanol and NH3, attributed to the charge transfer between the WS2 nanoflakes and the adsorbed gas molecules, which makes WS2 nanoflakes can be used in gas sensors. In brief, the multilayer WS2 nanoflakes are very sensitive to reducing gases, especially NH3 molecules, but relatively poor sensitive to O2 molecules. Under light illumination, all the gas molecules can be further adsorbed due to the increased electron-hole pairs, and the gas sensitivity is increased for O2, but decreased for ethanol and NH3. To our best of knowledge, this is a first report that may create much interest in further study about the gas sensing performance or the mutual influence with light for monolayer WS2 or other 2D materials.

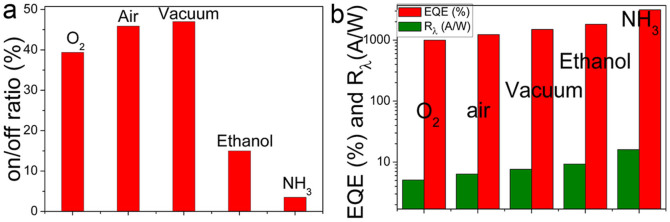

The gas molecules play an important role in the photosensitive properties. As on/off ratio, Rλ and EQE are critical parameters to evaluate the performance of a phototransistor, the effects of various gas molecules adsorption on the photosensitive properties are demonstrated with these parameters (Figure 5). Table 2 summarizes the performance parameters of our device at different gas atmospheres. The on/off ratio at all the gas atmospheres is lower than that in vacuum (Figure 5a). As mentioned above, poorly O2 molecules are adsorbed in dark, but the adsorption capacity of O2 is increased under light illumination. Thus, the reduction of photocurrent outweighs the reduction of dark current, leading to the reduced on/off ratio. As high sensitive gases for our device, the ethanol and NH3 have been strongly adsorbed in dark, leading to that the dark current becomes very large. When the light illuminates the device, the proportion of increased photocurrent is smaller among the total current, so that the on/off ratio is also decreased. However, the Rλ and EQE of our device are increased significantly in the presence of the ethanol and NH3 as shown in Figure 5b. The reason is that more ethanol or NH3 molecules will be adsorbed and donate more electrons when the light illuminated the device, and the number of photo-induced electrons detected per incident photons is overall increased. On the contrary, the oxidizing gases like O2 serving as electron acceptors will deplete the photo-induced electrons, leading to the decreased Rλ and EQE. Remarkably, the device even reaches a high Rλ of 884 A/W and EQE of 1.7 × 105 % at low illumination power density (50 μW/cm2) under NH3 atmosphere.

Figure 5. The effect of gas molecules on photoresponsive parameters.

The column diagram of (a) photosensitive on/off ratio, (b) Rλ and EQE of our device based on the multilayer WS2 nanoflakes at various gas atmospheres. The used incident light is 40 mW/cm2 with wavelength of 633 nm.

Table 2. Performance parameters (on/off ratio, Rλ and EQE) of the phototransistors based on the multilayer WS2 nanoflakes under light illumination (633 nm, 40 mW/cm2) at various gas atmospheres.

| Parameters | O2 | Air | Vacuum | Ethanol | NH3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| On/off ratio | 39 | 46 | 47 | 15 | 3.5 |

| Rλ (A/W) | 5.1 | 6.4 | 7.7 | 9.3 | 16.1 |

| EQE (%) | 999 | 1235 | 1500 | 1823 | 3146 |

Our experimental results also indicate that the gas molecules can influence the dependence of photoresponse on illumination intensity and the dynamic response to the light illumination. For example, at NH3 atmosphere, the dependent exponent α is significantly enhanced into 2.5, implying a high efficiency of photo-generated charge carriers attributed to that more NH3 molecules can be adsorbed with increased incident light density and more electrons can be transferred from these adsorbates. When the light is switched on, the response to light exhibits two stages including rapid rise and then slow increase process into saturation photocurrent, and the rise photocurrent curve is perfectly fitted by double exponential formula. All the results reveal that two kinds of physical process including the generation of photo-excited electron-hole pairs and charge transfer between the adsorbed gas molecules and the WS2 nanoflakes play an important role in the efficiency of photo-generated carriers and dynamic response of the device. The reducing gases especially NH3 would enhance the photosensitivity and efficiency of photo-generated charge carriers, and prolong the response due to their adsorption or desorption with light switching on or off.

To summarize, we report a comprehensive and systematic study about the optoelectronic properties including the field-effect, photosensitive and gas sensing behavior of the multilayer WS2 nanoflakes. The multilayer WS2 nanoflakes perform an n-type behavior with electron mobility of 12 cm2/Vs. The light can serve as “light gating” to modulate the carrier distribution in the WS2 nanoflakes, and the electrons density and mobility are improved under light illumination. Further, the photosensitive characteristics to red light (633 nm) are performed, and the τ, Rλ and EQE of the multilayer WS2 nanoflakes photodetectors are <20 ms, 5.7 A/W and 1118%, respectively, demonstrating that the 2D multilayer WS2 nanoflakes can be effectively used in highly sensitive photodetectors and fast photoelectric switches. Moreover, our devices can response to both oxidizing gas (O2) and reducing gas (ethanol, NH3) at room temperature ascribed to the charge transfer between the surface of the WS2 nanoflakes and physical-adsorbed gas molecules. Under the light illumination, more gas molecules would be adsorbed, and the O2 molecules acting as “p-dopants” can reduce the Rλ and EQE due to the consumption of photo-excited electrons, while the ethanol and NH3 molecules acting as “n-dopants” can significantly enhance the Rλ and EQE owing to the contribution of electrons. It is noted that the maximum Rλ and EQE can reach 884 A/W and 1.7 × 105 % respectively under the NH3 atmospheres, which is highest value of reports so far to our best knowledge. On the other hand, the dynamic response to light under ethanol and NH3 indicates the existence of two physical mechanisms involving the photo-generation or recombination of electron-hole pairs and gas adsorption or charge transfer. This work would also attract new interests in nanoelectronic and optoelectronic device based on mono- or few-layer WS2.

Methods

The transistors based on multilayer WS2 nanoflakes were fabricated with coplanar electrode geometry by “gold-wire mask moving” technique (Figure S9). Firstly, multilayer WS2 nanoflakes were exfoliated from the WS2 crystals onto 300 nm SiO2/Si substrates using mechanical exfoliation technique, and with vacuum-annealing at 350°C for 2 hours to remove the residual glue. Secondly, a micron gold-wire serving as a mask was fixed tightly on the top surface of WS2 nanoflakes, and then a pair of Au electrodes was deposited onto the substrate by thermal evaporation. To avoid the scattering of metallic atoms onto the side-face of SiO2/Si substrates, the sides of the substrate were covered with tinfoil. Moreover, the distance between the thermal evaporation boat and the sample was increased to 15 cm and the deposition rate was controlled at around 0.5 Å/s in order to minimize the heat influence. Finally, by slightly removing the Au wire mask and tinfoil, the Au electrodes were fabricated and a micron size gap was produced between the two electrodes.

Author Contributions

N.H. and J.L. conceived the project. N.H. performed the measurements. Z.W. performed AFM measurements. S.Y., Z.W., S.S.L., J.B.X. and J.L. edited the manuscript. N.H. and J.L. wrote the manuscript. All authors have read the manuscript.

Supplementary Material

Supporting Information

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China under Grant No.91233120 and the National Basic Research Program of China (2011CB921901).

References

- Geim A. K. Graphene: Status and Prospects. Science 324, 1530–1534 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avouris P., Chen Z. & Perebeinos V. Carbon-based electronics. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2, 605–615 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rao N. R., Sood A. K., Subrahmanyam K. S. & Govindaraj A. Graphene: the new two-dimensional nanomaterial. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 48, 7752–7777 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwierz F. Graphene transistors. Nat. Nanotechnol. 5, 487–496 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elias D. C. et al. Dirac cones reshaped by interaction effects in suspended graphene. Nature Phys. 7, 701–704 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- Geim A. K. & Novoselov K. S. The rise of graphene. Nature Mater. 6, 183–191 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xia F., Mueller T., Lin Y., Valdes-Garcia A. & Avouris P. Ultrafast graphene photodetector. Nat. Nanotechnol. 4, 839–843 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khan M. A., Kuznia J. N., Olson D. T., Blasingame M. & Bhattarai A. R. Schottky-barrier photodetector based on Mg-Doped P-type GaN films. Appl. Phys. Lett. 63, 2455–2456 (1993). [Google Scholar]

- Wilson J. A. & Yoffe A. D. Transition metal dichalcogenides: discussion and interpretation of observed optical, electrical and structural properties. Adv. Phys. 18, 193–335 (1969). [Google Scholar]

- Yoffe A. D. Layer compounds. Annu. Rev. Mater. Sci. 3, 147–170 (1993). [Google Scholar]

- Tsai D. S. et al. Few-Layer MoS2 with High Broadband Photogain and Fast Optical Switching for Use in Harsh Environments. ACS Nano 7, 3905–3911 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tongay S. et al. Broad-Range Modulation of Light Emission in Two-Dimensional Semiconductors by Molecular Physisorption Gating. Nano Lett. 13, 2831–2836 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu P. A. et al. Highly Responsive Ultrathin GaS Nanosheet Photodetectors on Rigid and Flexible Substrates. Nano Lett. 13, 1649–1654 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu P. A., Wen Z., Wang L., Tan P. & Xiao K. Synthesis of Few-Layer GaSe Nanosheets for High Performance Photodetectors. ACS Nano 6, 5988–5994 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu W. et al. Role of Metal Contacts in Designing High-Performance Monolayer n-Type WSe2 Field Effect Transistors. Nano Lett. 13, 1983–1990 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mak K., He K., Shan J. & Heinz T. F. Control of valley polarization in monolayer MoS2 by optical helicity. Nat. Nanotechnol. 7, 494–498 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Podzorov V., Gershenson M. E., Kloc C., Zeis R. & Bucher E. High-mobility field-effect transistors based on transition metal dichalcogenides. Appl. Phys. Lett. 84, 3301–3303 (2004). [Google Scholar]

- Ayari A., Cobas E., Ogundadegbe O. & Fuhrer M. S. Realization and electrical characterization of ultrathin crystals of layered transition-metal dichalcogenides. J. Appl. Phys. 101, 014507 (2007). [Google Scholar]

- Radisavljevic B., Radenovic A., Brivio J., Giacometti V. & Kis A. Single-layer MoS2 transistors. Nat. Nanotechnol. 6, 147–150 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mueller T., Xia F. & Avouris P. Graphene photodetectors for high-speed optical communications. Nat. Photonics 4, 297–301 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- Nair R. R. et al. Fine Structure Constant Defines Visual Transparency of Graphene. Science 320, 1308–1308 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez-Sanchez O., Lembke D., Kayci M. & Kis A. Ultrasensitive photodetectors based on monolayer MoS2. Nat. Nanotechnol. 8, 497–501 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xue D. J. et al. Anisotropic Photoresponse Properties of Single Micrometer-Sized GeSe Nanosheet. Adv. Mater. 24, 4528–4533 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Late D. J. et al. GaS and GaSe Ultrathin Layer Transistors. Adv. Mater. 24, 3549–3554 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H. et al. Fabrication of single- and multilayer MoS2 film-based field-effect transistors for sensing NO at room temperature. Small 8, 63–67 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He Q. et al. Fabrication of flexible MoS2 thin-film transistor arrays for practical gas-sensing applications. Small 8, 2994–2999 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Late D. J. et al. Sensing Behavior of Atomically Thin-Layered MoS2 Transistors. ACS Nano 7, 4879–4891 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perkins F. K. et al. Chemical Vapor Sensing with Monolayer MoS2. Nano Lett. 13, 668–673 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brainard W. A. The Thermal Stability And Friction Of The Disulfides, Diselenides, And Ditellurides Of Molybdenum And Tungsten In Vacuum (10−9 to 10−6 torr). NASA, Washington, 1969. [Google Scholar]

- Prasad S. V., McDevitt N. T. & Zabinski J. S. Tribology of tungsten disulfide-nanocrystalline zinc oxide adaptive lubricant films from ambient to 500°C. Wear 237, 186–196 (2000). [Google Scholar]

- Leitao L., Kumar S. B., Yijian O. & Jing G. Performance Limits of Monolayer Transition Metal Dichalcogenide Transistors. IEEE Trans. Electron Devices 58, 3042–3047 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- Hwang W. S. et al. Transistors with chemically synthesized layered semiconductor WS2 exhibiting 105 room temperature modulation and ambipolar behavior. Appl. Phys. Lett. 101, 013107 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- Yin Z. et al. Single-layer MoS2 phototransistors. ACS Nano 6, 74–80 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuc A., Zibouche N. & Heine T. Influence of quantum confinement onthe electronic structure of the transition metal sulfide TS2. Phys. Rev. B 83, 245213 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- Tang Q. et al. Low Threshold Voltage Transistors Based on Individual Single-Crystalline Submicrometer-Sized Ribbons of Copper Phthalocyanine. Adv. Mater. 18, 65–68 (2006). [Google Scholar]

- Tang Q., Li H., Liu Y. & Hu W. High-Performance Air-Stable n-Type Transistors with an Asymmetrical Device Configuration Based on Organic Single-Crystalline Submicrometer/Nanometer Ribbons. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 128, 14634–14639 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elías A. L. et al. Controlled Synthesis and Transfer of Large-Area WS2 Sheets: From Single Layer to Few Layers. ACS Nano 7, 5235–5242 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frey G. L., Tenne R., Matthews M. J., Dresselhaus M. S. & Dresselhaus G. Optical Properties of MS2 (M = Mo, W) Inorganic Fullerene-like and Nanotube Material Optical Absorption and Resonance Raman Measurements. J. Mater. Res. 13, 2412–2417 (1998). [Google Scholar]

- Berkdemir A. et al. Identification of Individual and Few Layers of WS2 Using Raman Spectroscopy. Sci. Rep. 3, 1755 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- Fivaz R. & Mooser E. Mobility of charge carriers in semiconducting layer structures. Phys. Rev. 163, 743–755 (1967). [Google Scholar]

- Sze S. M. & Kwok K. Ng. Physics Of Semiconductors Devices. John Wiley & Sons, Hoboken, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Carlos G. M. & Márcio C. S. MOSFET Modeling For Circuit Analysis And Design. World Scientific. Singapore, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang W. et al. High-Gain Phototransistors Based on a CVD MoS2 Monolayer. Adv. Mater. 25, 3456–3461 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Konstantatos G. et al. Hybrid graphene-quantum dot phototransistors with ultrahigh gain. Nat. Nanotechnol. 7, 363–368 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeon S. et al. Gated three-terminal device architecture to eliminate persistent photoconductivity in oxide semiconductor photosensor arrays. Nature Mater. 11, 301–305 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang C. et al. High-performance photodetectors for visible and near-infrared lights based on individual WS2 nanotubes. Appl. Phys. Lett. 100, 243101 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- Lee Y. H. et al. Synthesis and Transfer of Single-Layer Transition Metal Disulfides on Diverse Surfaces. Nano Lett. 13, 1852–1857 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Novoselov K. S. et al. Two-dimensional atomic crystals. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 102, 10451–10453 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fang H. et al. High-performance single layered WSe2 p-FETs with chemically doped contacts. Nano Lett. 12, 3788–3792 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jena D. & Konar A. Enhancement of carrier mobility in semiconductor nanostructures by dielectric engineering. Phys. Rev. Lett. 98, 136805 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Konar A., Fang T. & Jena D. Effect of high-κ gate dielectrics on charge transport in graphene-based field effect transistors. Phys. Rev. B 82, 115452 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- Newaz A. K. M., Puzyrev Y. S., Wang B., Pantelides S. T. & Bolotin K. I. Probing charge scattering mechanisms in suspended graphene by varying its dielectric environment. Nature Commun. 3, 734 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen F., Xia J., Ferry D. K. & Tao N. Dielectric screening enhanced performance in graphene FET. Nano Lett. 9, 2571–2574 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leenaerts O., Partoens B. & Peeters F. M. Adsorption of H2O, NH3, CO, NO2, and NO on graphene: A first-principles study. Phys. Rev. B 77, 125416 (2008). [Google Scholar]

- Yuan W. & Shi G. Graphene-based gas sensors. J. Mater. Chem. A 1, 10078–10091 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- Schedin F. et al. Detection of individual gas molecules adsorbed on graphene. Nature Mater. 6, 652–655 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yue Q., Shao Z., Chang S. & Li J. Adsorption of gas molecules on monolayer MoS2 and effect of applied electric field. Nanoscale Res. Lett. 8, 425 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supporting Information