“Only one link of the chain of destiny can be handled at a time.” – Winston Churchill

All proteins are translated from RNA, but only a fraction of RNAs appear to be translated into proteins. Advanced genomics technologies have uncovered noncoding regulatory RNAs exhibiting extraordinary diversity in size, structure, and molecular function. We know a great deal about small (~20 nt) microRNAs that postranscriptionally regulate translation of protein from target mRNAs having complementary 3’ sequences. These linear single stranded nucleotides are transcribed either as independent gene products or as passengers within so-called miRtrons (microRNA-containing introns) of protein coding genes, then processed and exported from the nucleus where they incorporate into RNA-induced silencing complexes1. Because some microRNAs exhibit altered expression or differing circulating levels, they are being assessed as diagnostic biomarkers in cardiac disease. As yet, we know far less about the larger (>200 nt) long noncoding (lnc) RNAs. LncRNAs are generated as antisense transcripts of protein coding genes, as sense transcripts from within protein coding gene introns, or as independent transcripts originating from intergenic regions2. Unlike short microRNAs, lncRNAs are sufficiently long to develop multiple intramolecular RNA-RNA interactions conferring upon them complex three dimensional structures. The unique physical configurations of different lncRNAs enables many of them to bind specific sets of proteins. Likewise, openly configured single strand RNA sequences within lncRNA structures permit them to bind to complementary sequences in the genome. The combination of these two characteristics, protein binding and recognition of specific DNA sequences, evokes a characteristic lncRNA functionality: chaperoning transcriptional modulators or chromatin modifiers to specific genomic locations. In this manner, lncRNAs can epigenetically regulate gene expression3.

Our nascent but growing understanding of lncRNA biology generally assumes that they are produced by, and act upon, the nuclear genome. In the current issue of Circulation Research, Kumarswamy and colleagues provide evidence that late circulating levels of the lncRNA uc022bqs.1, which they have named LIPCAR, are associated with adverse outcomes after MI (ventricular dilatation) or in chronic heart failure (cardiovascular mortality)4. Intriguingly, this lncRNA is described as mitochondrial-derived. Indeed, approximately three fourths of lncRNAs reported as “highly abundant” in plasma samples assayed from the REVE-2 study cohort were classified as originating from the mitochondrial genome. Likewise, the seven lncRNAs Kumarswamy, et al consistently detected in plasma samples were all categorized as mitochondrial4. Although mitochondrial dysfunction5 and mitochondrial-derived factors6, 7 have previously been nominated as biomarkers of cardiac disease, the observation that mitochondrial-derived lncRNAs are so numerous and abundant has implications far beyond their detection in disease.

Modern animal mitochondrial (and plant chloroplast) genomes are fragmentary remnants of the primordial bacterial genomes that immigrated into our eukaryotic single cell ancestors through endosymbiotic partnering8, 9. Like their bacterial predecessors, mitochondrial genomes are comprised of circular double stranded DNA that lacks chromatin structure. Compared to nuclear DNA, mitochondrial DNA has a differect genetic alphabet for encoding amino acids. Human mitochondrial DNA is ~16.5 kb and encodes the 16S and 12S mitochondrial ribosomal RNAs and 22 transfer RNAs necessary for mitochondrial protein synthesis, as well as 13 proteins of the electron transport chain that drives ATP synthesis. The primordial mitochondrial DNA that encoded the other >1,000 mitochondrial protein-coding genes has, over evolutionary time, been exported to the nucleus10.

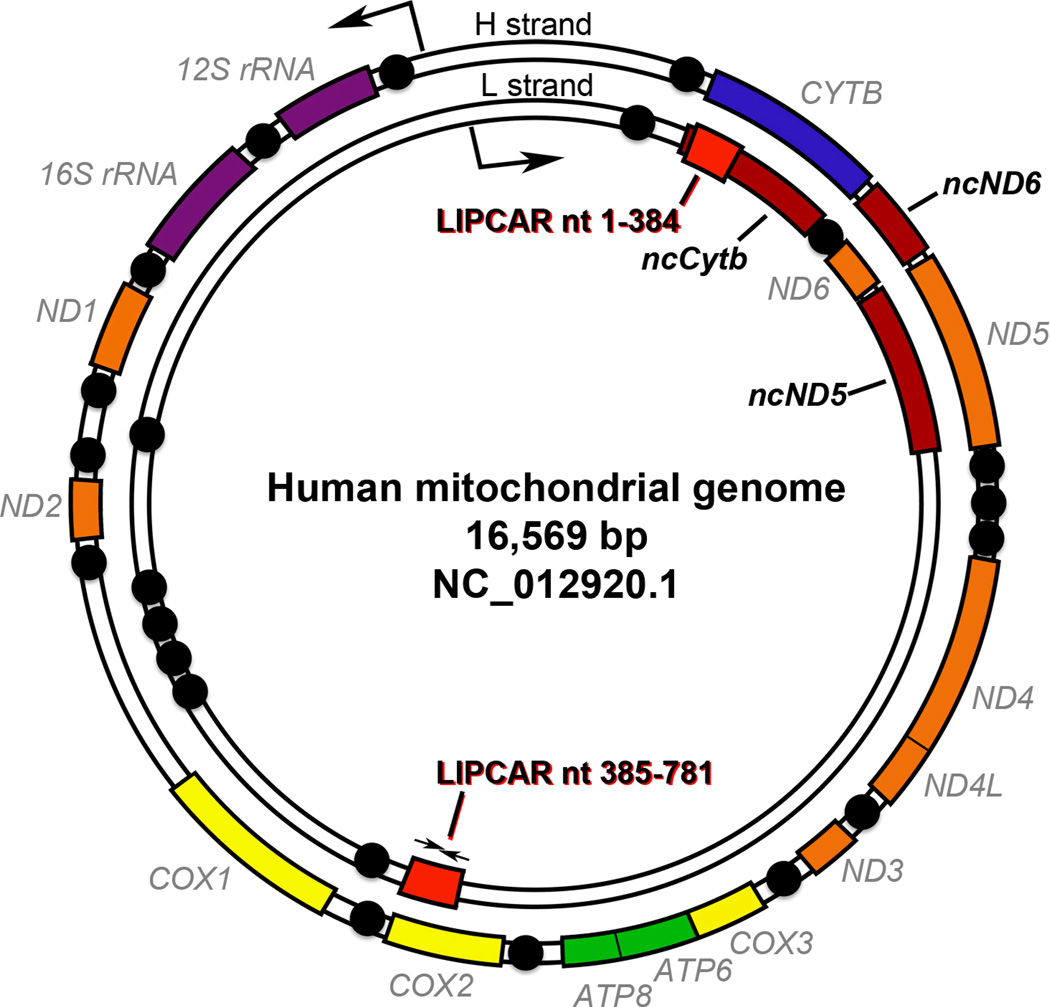

The two strands of the circular mitochondrial genome are designated “heavy” (H) and “light” (L) based on their GC content and sedimentation characteristics (Figure). The H strand is genetically congested, containing both ribosomal RNA genes, 14 of the tRNAs, and 12 of the 13 protein coding genes. By comparison, the L strand has only one protein coding gene and the remaining 8 tRNAs. Mitochondrial protein coding genes are intronless and, with three exceptions, are each separated by tRNAs. Both strands are transcribed as large polycistronic precursor transcripts that are processed into individual functional units.

Figure. Map of LIPCAR and other lncRNAs on the human mitochondrial genome.

The double stranded circular human mitochondrial genome is represented showing positions of tRNA (black spheres), rRNA (purple segments) and protein coding genes (orange, yellow, blue, and green segments). Validated mitochondrial lncRNAs are rust segments. LIPCAR sequences map to red segments; small arrows indicate position of qPCR primers.

Evidence has been accumulating in support of a mitochondrial origin for some noncodingRNAs. Numerous putative mitochondrial small RNAs were first detected after small RNA deep sequencing data mapped to human and murine mitochondrial genomes; many of these noncodingRNAs were validated as originating from mitochondria in studies comparing normal and mitochondria-depleted cells11. Recently, strand-specific RNA sequencing uncovered three lncRNAs generated from the human mitochondrial genome12. As each lncRNA is the antisense counterpart to a mitochondrial protein coding gene, they were designated lncND5 RNA, lncND6 RNA, and lncCytb RNA (Figure). The ND5 and CytB protein coding genes are on the H strand, so their lncRNA gene counterparts are on the L strand; conversely, the lncND6 gene is located on the H strand. These mitochondrial lncRNAs can form RNAse-resistant duplexes with their respective complementary mRNAs, which is postulated to modulate mRNA expression or stability12. These interesting data support the existence of functional mitochondrial lncRNAs, and provide a strong impetus for efforts to discover and characterize others.

As shown by the research that uncovered mitochondrial lncND5 RNA, lncND6 RNA, and lncCytb RNA, establishing the genomic position and sequence complementarity of a lncRNA can provide clues to its biological function. Mapping the complete 781 nt LIPCAR sequence (i.e. the uc022bqs.1 sequence as reported by the UCSC Genome Brower; http://genome.ucsc.edu) to the human mitochondrial genome provides an unexpected result: the 5’ half (nt 1–392) maps to antisense of the mitochondrial CYTB gene (nt 15887–15496 of NC_012920.1), but the 3’ half (nt 385–781) maps to antisense of the mitochondrial COX2 gene (nt 7982–7586) (Figure and Online Figure I). Indeed, the 5’ half of LIPCAR is wholly contained within the previously described mitochondrial lncCytb gene12. Thus, the two halves of LIPCAR are half a mitochondrial genome apart. Given that mitochondrial genes lack introns and are not known to undergo splicing, discontinuity of the LIPCAR lncRNA seems incongruous.

As noted, mitochondria have exported the vast majority of their ancestral genomes to the nucleus. What is sometimes overlooked is that the current mitochondrial genome has also been copied to the nuclear genome. Because differences between the amino acid codes of nuclear and mitochondrial genomes prevent nuclear-integrated copies of modern-day mitochondrial DNA from producing their encoded proteins, they have been considered to be non-functional and therefore commonly referred to as pseudogenes. Nevertheless, human mitochondrial DNA-derived nuclear insertions are abundant, comprising at least 500,000 base pairs (or 0.016% of the 3 billion base pair nuclear genome), and are present on all 24 nuclear chromosomes13. Indeed, the entire mitochondrial genome, including all protein-coding, rRNA, tRNA, and noncoding sequence, is replicated many times over within the nuclear genome. An early report described almost 300 nuclear inserts of mitochondrial DNA, ranging from nearly complete 10–14 kb inserts on chromosomes 1, 2, 4, and 9, to dozens of >2kb fragments randomly distributed throughout the genome10. As recent evidence indicates that pseudogenes can generate functional lncRNAs14, the question arises as to whether nuclear-integrated mitochondrial pseudogenes also function as real genes that express noncoding RNAs.

A BLAST search of the LIPCAR nucleotide sequence to the human nuclear genome shows >90% identity of the 385–781 nt sequence to chromosome 1, and of the entire 1–781 nt sequence to chromosome 5 (Online Figure I). The 385–781 half of LIPCAR also has ≥75% identity to COX2 pseudogene sequences on chromosomes 2, 4, 7, 8, 9, 10, 17, and X. As the qPCR primers Kumarswamy et al used to validate LIPCAR regulation in the post-MI LV remodeling study and assess its relationship to heart failure outcome4 are internal to the 385–781 nt half (Figure), this PCRassay will not confidently distinguish between mitochondrial-derived and nuclear-derived transcripts. Likewise, it is unclear what sequence tags for LIPCAR are present on the microarrays used by Kumarswamy et al for their initial screening tests. Therefore, the conservative interpretation is that the circulating RNA that predicts ventricular remodeling (and the other circulating lncRNAs the authors designated as mitochondrial-derived) may originate in the nucleus, mitochondria, or both. Since the various nuclear pseudogenes for mitochondrial COX2 have acquired subtle but site-specific nucleotide changes, RNA-sequencing15 of unamplified plasma lncRNA might resolve ambiguities about LIPCAR biogenesis. Such information could also propel efforts to define the cell of origin and potential DNA targets of LIPCAR, which are currently indeterminate.

The confounding influence of nuclear-entrapped mitochondrial genomic fragments is not new16, 17. Furthermore, whether the LIPCAR lncRNA (or its PCR-amplified fragment) is mitochondrial or nuclear does not alter its potential value as a cardiac biomarker. Indeed, the issues of biological function and potential diagnostic utility seem separate. A new biomarker will be useful if it shows a better sensitivity and specificity profile, or enhanced predictive value, than standard clinical diagnostics. As heretical as it may first seem, the molecular mechanism (or even existence) of biological activity for a biomarker is not important. Future prospective studies to assess whether circulating LIPCAR specifically predicts post-MI ventricular remodeling, and to define its reliability in identifying patients who are at greater risk for adverse outcomes in heart failure, will ultimately determine its utility as a biomarker. Meanwhile, discovering what noncoding RNAs are generated within mitochondria, and uncovering how they impact normal metabolic homeostasis and the response to injury or stress, will require an approach focused on basic mechanisms.

Acknowledgements

Supported by NIH R01 HL108943.

Footnotes

The author declares no conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Condorelli G, Latronico MV, Dorn GW., 2nd microRNAs in heart disease: putative novel therapeutic targets? Eur Heart J. 2010;31:649–658. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehp573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schonrock N, Harvey RP, Mattick JS. Long noncoding RNAs in cardiac development and pathophysiology. Circ Res. 2012;111:1349–1362. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.112.268953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lee JT. Epigenetic regulation by long noncoding RNAs. Science. 2012;338:1435–1439. doi: 10.1126/science.1231776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kumarswamy R, Bauters C, Volkmann I, Maury F, Fetisch J, Holzmann A, Lemesle G, Degroote P, Pinet F, Thum T. The circulating long non-coding RNA LIPCAR predicts survival in heart failure patients. Circ Res. 2014 doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.114.303915. (In Press). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wei L, Salahura G, Boncompagni S, Kasischke KA, Protasi F, Sheu SS, Dirksen RT. Mitochondrial superoxide flashes: metabolic biomarkers of skeletal muscle activity and disease. FASEB J. 2011;25:3068–3078. doi: 10.1096/fj.11-187252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kim N, Lee Y, Kim H, Joo H, Youm JB, Park WS, Warda M, Cuong DV, Han J. Potential biomarkers for ischemic heart damage identified in mitochondrial proteins by comparative proteomics. Proteomics. 2006;6:1237–1249. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200500291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Marenzi G, Giorgio M, Trinei M, Moltrasio M, Ravagnani P, Cardinale D, Ciceri F, Cavallero A, Veglia F, Fiorentini C, Cipolla CM, Bartorelli AL, Pelicci P. Circulating cytochrome c as potential biomarker of impaired reperfusion in ST-segment elevation acute myocardial infarction. Am J Cardiol. 2010;106:1443–1449. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2010.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yang D, Oyaizu Y, Oyaizu H, Olsen GJ, Woese CR. Mitochondrial origins. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1985;82:4443–4447. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.13.4443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gray MW, Burger G, Lang BF. Mitochondrial evolution. Science. 1999;283:1476–1481. doi: 10.1126/science.283.5407.1476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mourier T, Hansen AJ, Willerslev E, Arctander P. The Human Genome Project reveals a continuous transfer of large mitochondrial fragments to the nucleus. Mol Biol Evol. 2001;18:1833–1837. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a003971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ro S, Ma HY, Park C, Ortogero N, Song R, Hennig GW, Zheng H, Lin YM, Moro L, Hsieh JT, Yan W. The mitochondrial genome encodes abundant small noncoding RNAs. Cell Res. 2013;23:759–774. doi: 10.1038/cr.2013.37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rackham O, Shearwood AM, Mercer TR, Davies SM, Mattick JS, Filipovska A. Long noncoding RNAs are generated from the mitochondrial genome and regulated by nuclear-encoded proteins. RNA. 2011;17:2085–2093. doi: 10.1261/rna.029405.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Woischnik M, Moraes CT. Pattern of organization of human mitochondrial pseudogenes in the nuclear genome. Genome Res. 2002;12:885–893. doi: 10.1101/gr.227202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rapicavoli NA, Qu K, Zhang J, Mikhail M, Laberge RM, Chang HY. A mammalian pseudogene lncRNA at the interface of inflammation and anti-inflammatory therapeutics. Elife. 2013;2:e00762. doi: 10.7554/eLife.00762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Matkovich SJ, Zhang Y, Van Booven DJ, Dorn GW., 2nd Deep mRNA sequencing for in vivo functional analysis of cardiac transcriptional regulators: application to Galphaq. Circ Res. 2010;106:1459–1467. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.110.217513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Perna NT, Kocher TD. Mitochondrial DNA: molecular fossils in the nucleus. Curr Biol. 1996;6:128–129. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(02)00441-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yao YG, Kong QP, Salas A, Bandelt HJ. Pseudomitochondrial genome haunts disease studies. J Med Genet. 2008;45:769–772. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2008.059782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]