Abstract

Background

Femoroacetabular impingement (FAI) now represents one of the most common causes of early cartilage and labral damage in the non-dysplastic hip. Biomarkers of cartilage degradation and inflammation are associated with osteoarthritis. It was not known whether patients with FAI have elevated levels of biomarkers of cartilage degradation and inflammation.

Hypothesis

We hypothesized that, compared to athletes without FAI, athletes with FAI would have elevated levels of the inflammatory C-reactive protein (CRP) and the cartilage degradation marker, cartilage oligomeric matrix protein (COMP).

Study Design

Descriptive laboratory study Methods: Male athletes with radiographically confirmed FAI (N=10) were compared to male athletes with radiographically normal hips with no evidence of FAI or hip dysplasia (N=19). Plasma levels of COMP and CRP were measured, and subjects also completed the Short Form-12 (SF-12) and Hip disability and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score (HOOS) surveys.

Results

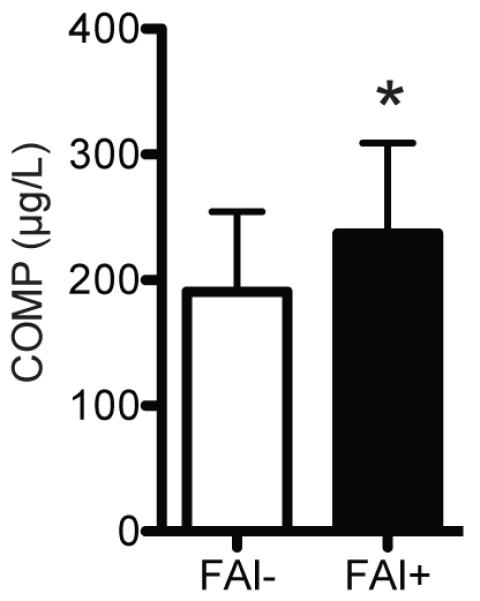

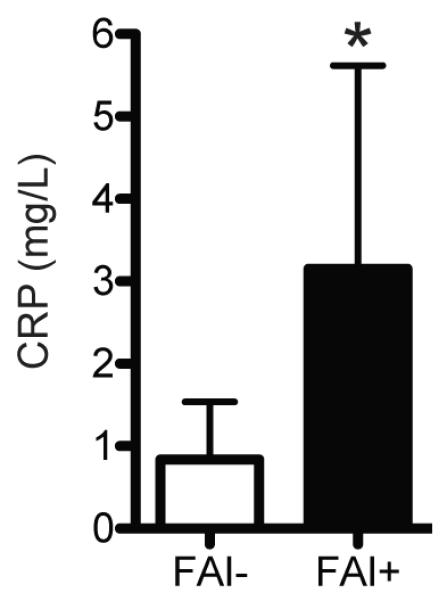

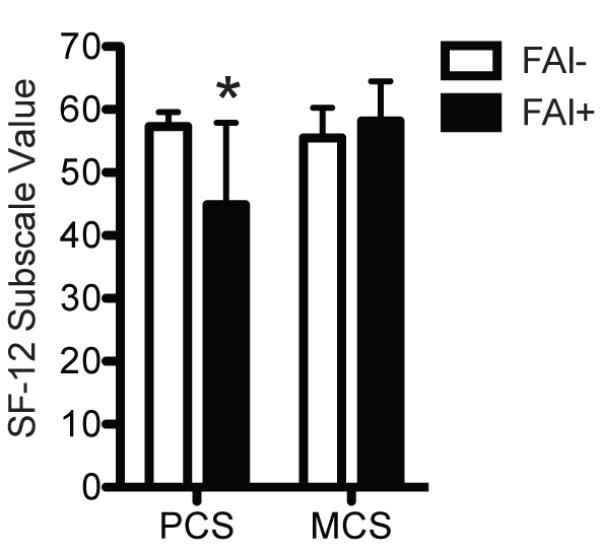

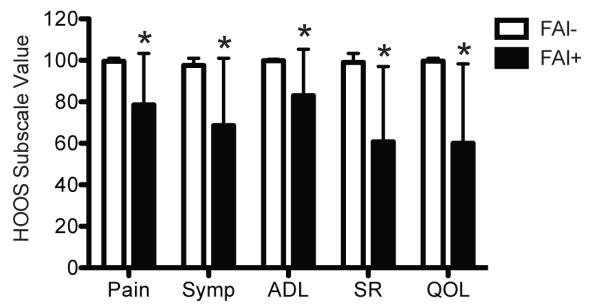

Compared with control athletes, athletes with FAI had a 24% increase in COMP levels and a 276% increase in CRP levels, as well as a 22% decrease in SF-12 physical component scores, and decreases in all of the HOOS subscale scores.

Conclusion

Athletes with FAI demonstrate early biochemical signs of increase cartilage turnover and systemic inflammation.

Clinical Relevance

Chondral injury secondary to the repetitive microtrauma of FAI might be reliably detected using biomarkers. In the future, these biomarkers might be utilized as screening tools to identify at-risk patients and assess the efficacy of therapeutic interventions such as hip preservation surgery in altering the natural history and progression to osteoarthritis.

Keywords: C-reactive protein, cartilage oligomeric matrix protein, osteoarthritis, HOOS, SF-12

Introduction

Hip osteoarthritis (OA) is the second most common site of OA, with 10% of the population experiencing pain, limited function and disability from this condition 2. Femoroacetabular impingement (FAI) is one of the most common mechanisms that leads to the development of early cartilage and labral damage in the non-dysplastic hip 4, 7, 11, 15, 37. The development of symptomatic hip injury in the non-arthritic hip is related to the underlying structural anatomy of the hip joint combined with the applied mechanical loads. While the combination of dynamic and static factors that impact the mechanics of the hip joint are complex, the most common structural deformities are a loss of femoral head-neck offset (“cam”), focal or global acetabular over-coverage (“pincer”), or combined impingement deformity. These anatomic abnormalities of the proximal femur and/or acetabulum result in repetitive collisions occurring during dynamic hip motion that lead to regional loading of the femoral head-neck junction against the acetabular rim which can precipitate labral injury, chondral delamination, and a degenerative cascade of more extensive, nonfocal intra-articular injury 1, 5, 18. The severity of the labral and associated cartilaginous injury is often dependent upon the duration of the untreated injury, suggesting the importance of early diagnosis and treatment 13, 23, 29.

Several studies have now established that the surgical treatment of FAI is an effective and safe method to reliably achieve pain relief and improved function at short-term to mid-term follow-up in patients without significant OA 5, 15, 30. Using 3D models based on CT scans, we and others have demonstrated an improvement in vivo hip kinematics after surgical correction of FAI 6, 26. While FAI decompression improves the in vivo kinematics after surgical correction of FAI, to-date there have been no studies that have correlated specific prognostic indicators of OA with successful treatment of FAI by hip preservation surgery. In addition, the existing literature does not provide support for prophylactic surgical intervention in asymptomatic individuals, as an alteration in the natural history or progression of OA after FAI surgery has not been established with the available short- and mid-term follow-up.

Many biomarkers of inflammation and cartilage turnover have been used to study the progression of OA. Cartilage oligomeric matrix protein (COMP) is a connective tissue extracellular matrix (ECM) protein that binds several other ECM proteins and helps to organize collagen II rich matrices 19, 34. COMP also circulates in the blood and is a marker of cartilage turnover, with increased levels of COMP associated with joint inflammation and OA 19, 34. C-reactive protein (CRP) is a biological marker that is associated with inflammation 10, and there is a correlation between increasing CRP levels and the severity of OA 35.

While COMP and CRP have a well established role in tracking the progression of early cartilage breakdown and inflammation and in patients with OA, it is not known whether they are altered in the presence of FAI prior to the establishment of more advanced degenerative OA. We hypothesized that athletes with FAI would have elevated levels of biomarkers of inflammation and cartilage catabolism. To test this hypothesis, we measured the levels of COMP and CRP in male athletes with FAI, and compared this to activity-matched and age-matched male athletes with radiographically normal hip morphology.

Materials and Methods

Subjects

This study was approved by the blinded Institutional Review Board. All subjects provided informed consent prior to participating in the study. Subjects were recruited from our sports medicine clinic or from flyers placed around campus. The inclusion criteria for the control group (FAI-) included physically active male athletes, 18 to 40 years of age, with radiographically normal hips (absence of FAI and dysplasia), and negative anterior impingement and flexion, adduction, and internal rotation (FADIR) manual tests 33. Subjects were excluded from the control group if they had a previous history of hip pain, lower extremity injury, major medical illnesses or musculoskeletal diseases. The inclusion criteria for the experimental group (FAI+) included symptomatic physically active male athletes, 18 to 40 years of age, with radiographically confirmed presence of cam-type, pincer-type, or mixed FAI lesions, and positive anterior impingement and FADIR manual tests. The exclusion criteria for the experimental group were a history of hip surgery, hip dysplasia, significant hip joint chondral degeneration (greater than Tönnis grade I), other lower extremity injury not related to FAI, major medical illnesses or musculoskeletal diseases. The presence or absence of cam, pincer or mixed FAI lesions on AP, frog lateral or Dunn lateral radiographs was determined by a board certified and fellowship trained musculoskeletal radiologist according to the guidelines of Ganz 18.

Measurement of Biomarkers

Approximately 3mL of blood was collected from an antecubital vein into a K2-EDTA tube. Blood was spun down at 1000×g for 10 minutes, and plasma was removed and stored at −80°C until use. Plasma samples were analyzed in duplicate using ELISAs for COMP (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN) and ultra-sensitive CRP (Calbiotech, Spring Valley, CA) in a SpectraMax plate reader (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA). Assays were conducted following the instructions from the manufacturer.

Questionnaires

All subjects completed the SF-12 survey to evaluate general health 39, the HOOS questionnaire to evaluate hip-specific function 24, and Tegner scale to evaluate physical activity level 38.

Statistical Analyses

Results are presented as mean±SD. Prism 5.0 (GraphPad Software, LaJolla, CA) was used to analyze results. Differences between groups were tested using Student’s t-tests (α=0.05).

Results

To determine if athletes with FAI have elevated levels of biomarkers of cartilage degradation and inflammation and differences in SF-12 and HOOS scores, we recruited age-, activity- and BMI-matched subjects with radiographically confirmed absence of FAI (Table 1) to serve as a healthy control group. Compared with controls, athletes with FAI had a 24% increase (P=0.04) in circulating levels of COMP (Figure 1) and a 276% increase (P<0.001) in circulating levels of CRP (Figure 2). We also asked each subject to complete the SF-12 and HOOS questionnaires. Athletes with FAI had a 22% reduction (P<0.001) in the SF-12 PCS but no change (P=0.11) in the SF-12 MCS (Figure 3). For the HOOS questionnaire, athletes with FAI had a 21% reduction (P<0.001) in pain subscale scores, a 30% reduction (P<0.001) in symptoms scores, a 17% decrease (P=0.001) in activities of daily living scores, a 39% decrease (P<0.001) in sport and recreation scores, and a 40% reduction (P<0.001) in hip-related quality of life scores (Figure 4).

Table 1. Characteristics of subjects without FAI (FAI−) and subjects with FAI (FAI+).

Values are presented as mean±SD. No differences between FAI− and FAI+ subjects was measured for any of these categories.

| FAI− | FAI+ | |

|---|---|---|

| Number of Subjects | 19 | 10 |

| Age (years) | 22.3±3.4 | 23.1±6.4 |

| Tegner Activity Level | 7.7±1.0 | 7.3±2.9 |

| Body Mass Index (kg × m−2) | 24.8±2.6 | 26.5±3.5 |

Figure 1. Circulating COMP Levels.

Compared with control athletes (FAI-, N=19), athletes with FAI (FAI+, N=10) had an elevation in circulating COMP levels. Values are mean±SD. *, significantly different from FAI- (P<0.05).

Figure 2. Circulating CRP Levels.

Compared with control athletes (FAI-, N=19), athletes with FAI (FAI+, N=10) had an elevation in circulating CRP levels. Values are mean±SD. *, significantly different from FAI- (P<0.05).

Figure 3. SF-12 Scores.

Compared with control athletes (FAI-, N=19), athletes with FAI (FAI+, N=10) had lower SF-12 PCS scores but no difference in MCS scores. Values are mean±SD. *, significantly different from FAI- (P<0.05).

Figure 4. HOOS Scores.

Compared with control athletes (FAI-, N=19), athletes with FAI (FAI+, N=10) had decreased pain, symptoms (Symp), hip related activities of daily living (ADL), sport and recreation (SR) and hip related quality of life (QOL) HOOS subscale values. Values are mean±SD. *, significantly different from FAI- (P<0.05).

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to determine if athletes with symptomatic FAI had elevated biomarkers of cartilage degeneration and inflammation. In the current study, COMP and CRP levels were significantly higher in athletes with FAI compared to age and activity matched athletes without FAI. Additionally, we identified that athletes with FAI also had reduced SF-12 PCS scores and significant reductions in all of the HOOS subscale scores. These results suggest that biochemical changes are occuring within the joints of patients with FAI that may contribute to the subsequent development of OA.

Hip OA is one of the most severe and frequent disabilities in the elderly population, and primary hip arthroplasties represent a quarter of the total joint replacement surgeries performed annually 2. Developmental dysplasia, slipped capital femoral epiphyses and Legg-Calvé-Perthes disease have long been strongly associated with the development of OA later in life, but these conditions are responsible for less than 10% of primary hip arthroplasties 28. The mechanisms that lead to the development of the majority of hip OA cases remains largely unknown 20, 28. Recently, Ganz and colleagues 4, 17, 18 put forth a theory that the anatomic abnormalities of the proximal femur and or acetabulum in patients with FAI result in regional loading of the femoral head-neck junction against the acetabular rim, leading to labral injury, chondral delamination, and a degenerative cascade of more extensive, nonfocal intra-articular injury. Anatomical simulations 6, 26, whole body kinematics 12 and T2* MRI studies 3, 9 strongly support a connection between FAI and the development of OA.

COMP is a glycoprotein found in articular cartilage that helps to stabilize and align type II collagen molecules. When articular cartilage is broken down, COMP is released into the circulation which makes it a useful marker of cartilage degeneration 19. Circulating levels of COMP are elevated in patients with radiographically apparent OA, and increase as OA burden increases 14, 16, 36. While there are no specific reference values of COMP available for younger subjects that assess the risk of developing OA, the increased COMP levels in athletes with FAI compared to age- and activity-matched asymptomatic controls provide the first biochemical evidence to support a potential connection between FAI and OA, and provide support for the use of biomarkers as a diagnostic and screening tool for FAI.

CRP is an acute phase protein that plays a central role in initiating the systemic response to inflammation, with circulating levels rising 1000-fold or more over baseline following acute injuries or infections 10. While CRP has traditionally been used as a marker for acute conditions, over the past decade there has been a recognition that chronic, low level elevations in CRP are linked to greater risk of developing cardiovascular disease, obesity and metabolic syndrome 21, 22. Screening guidelines for CRP and cardiovascular disease risk from the American Heart Association and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention place individuals with CRP levels less than 1 mg/L at low relative risk, individuals between 1 and 3 mg/L are at average risk, and individuals over 3 mg/L are at high risk 32. In the current study, mean CRP levels for control athletes (0.83 mg/L) would be classified in the low risk category, but the mean score of athletes with FAI (3.15 mg/L) would be in the high risk category. Cardiovascular disease is multifactorial in nature and CRP levels are only one screening tool to assess risk 21, but as OA is associated with cardiovascular disease 31 these results may suggest that FAI results in a low level of inflammation that could potentially place individuals at greater risk of developing cardiovascular or metabolic diseases later in life. While further studies are necessary, it is possible that reducing inflammation associated with FAI may not only lead to reduced pain, improved physical function and greater range of motion, there may be indirect health benefits associated with the surgical treatment of FAI.

There are several limitations to the current study. The study included males only and, in this regard, is not necessarily generalizable to the entire population. Several studies have reported variability in the types and morphology of FAI between genders, with females demonstrating more pincer-type disease that is more difficult to reliably detect or characterize on plain radiographs 8. Although we would anticipate a positive correlation between the size of FAI-associated chondral lesions and COMP levels, we did not directly quantify the extent of chondral lesions in the athletes with FAI in this study. We also included individuals less than 40 years of age, but this age limit was selected to minimize the anticipated chondrolabral disease and articular cartilage degeneration that is known to progress with age in the presence of absence of FAI. We also evaluated only a single time point in athletes with FAI and did not assess whether COMP and CRP levels change over time. Future longitudinal studies are necessary to further define the changes in these biomarkers with time and with or without corrective surgical intervention. A limitation in the use of any circulating biomarker of cartilage breakdown is the inability to identify specific joints where they originated. We attempted to aspirate synovial fluid under ultrasound guidance to correlate with serum measures, but the low volume of synovial fluid in the hip joint, along with the small amount of contaminating blood from skin and subcutaneous tissues made it difficult to obtain sufficient quantities of clean synovial fluid for analysis. Similarly, although CRP is largely produced in the liver in response to proinflammatory signals sent from inflamed tissues 10, we cannot directly determine a causal link between FAI and elevated CRP levels. Recent work identified that radiographic signs of FAI were frequently observed in collegiate NFL prospects, although not every athlete that showed signs of FAI had symptoms of hip or groin pain 27. Additional insight would be gained in future studies evaluating both genders, a wider variety of age levels, a spectrum of specific FAI subtypes and symptom levels, and additional biomarkers of inflammation and OA.

Despite the limitations of the study, our results provide the first biochemical support linking FAI with increase cartilage turnover and elevated systemic inflammation. Clinical intervention for FAI is currently indicated for symptomatic hip pain and deterioration in function, and unfortunately patients with FAI often present after significant chondral and labral injury has occurred 8. While anatomical, biomechanical and now biochemical studies have linked FAI to the development of OA, prognostic indicators of OA that correlate with successful hip preservation surgery have not yet been identified. It is also not known whether prophylactic preservation surgery in asymptomatic individuals will be effective, as an alteration in the natural history or progression of OA after corrective surgery for FAI has not been determined. Given the importance that biomarkers play in tracking the progression and severity of joint degeneration and inflammation in patients with OA 19, 25, 34, biomarkers may serve as a useful and cost-effective tool to identify at-risk FAI patients and assess the efficacy of therapeutic interventions such as hip preservation surgery in altering the natural history and progression to OA.

What is known about the subject

While surgical decompression of FAI improves hip kinematics, there have been no studies that have identified specific prognostic indicators of osteoarthritis that will correlate with successful hip preservation surgery.

What this study adds to existing knowledge

This is the first study to-date that demonstrates significant differences in the levels of circulating biomarkers of inflammation and chondral injury in asymptomatic patients with FAI compared to matched controls.

References

- 1.Allen D, Beaule PE, Ramadan O, Doucette S. Prevalence of associated deformities and hip pain in patients with cam-type femoroacetabular impingement. The Journal of bone and joint surgery. British volume. 2009;91(5):589–594. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.91B5.22028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons . The burden of musculoskeletal diseases in the United States : prevalence, societal, and economic cost. American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons; Rosemont, IL: 2008. ISBN 9780892035335. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Apprich S, Mamisch TC, Welsch GH, et al. Evaluation of articular cartilage in patients with femoroacetabular impingement (FAI) using T2* mapping at different time points at 3.0 Tesla MRI: a feasibility study. Skeletal radiology. 2011 doi: 10.1007/s00256-011-1313-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Beck M, Kalhor M, Leunig M, Ganz R. Hip morphology influences the pattern of damage to the acetabular cartilage: femoroacetabular impingement as a cause of early osteoarthritis of the hip. The Journal of bone and joint surgery British volume. 2005;87(7):1012–1018. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.87B7.15203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bedi A, Chen N, Robertson W, Kelly BT. The management of labral tears and femoroacetabular impingement of the hip in the young, active patient. Arthroscopy : the journal of arthroscopic & related surgery : official publication of the Arthroscopy Association of North America and the International Arthroscopy Association. 2008;24(10):1135–1145. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2008.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bedi A, Dolan M, Hetsroni I, et al. Surgical Treatment of Femoroacetabular Impingement Improves Hip Kinematics: A Computer-Assisted Model. The American Journal of Sports Medicine. 2011;39(1_suppl):43S–49S. doi: 10.1177/0363546511414635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bedi A, Dolan M, Leunig M, Kelly BT. Static and dynamic mechanical causes of hip pain. Arthroscopy : the journal of arthroscopic & related surgery : official publication of the Arthroscopy Association of North America and the International Arthroscopy Association. 2011;27(2):235–251. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2010.07.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bedi A, Kelly BT. Femoroacetabular impingement. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2013;95(1):82–92. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.K.01219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bittersohl B, Hosalkar HS, Hughes T, et al. Feasibility of T2* mapping for the evaluation of hip joint cartilage at 1.5T using a three-dimensional (3D), gradient-echo (GRE) sequence: a prospective study. Magnetic resonance in medicine : official journal of the Society of Magnetic Resonance in Medicine / Society of Magnetic Resonance in Medicine. 2009;62(4):896–901. doi: 10.1002/mrm.22096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Black S, Kushner I, Samols D. C-reactive Protein. J Biol Chem. 2004;279(47):48487–48490. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R400025200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brand RA. Femoroacetabular impingement: current status of diagnosis and treatment: Marius Nygaard Smith-Petersen, 1886-1953. Clinical orthopaedics and related research. 2009;467(3):605–607. doi: 10.1007/s11999-008-0671-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brisson N, Lamontagne M, Kennedy MJ, Beaule PE. The effects of cam femoroacetabular impingement corrective surgery on lower-extremity gait biomechanics. Gait & posture. 2012 doi: 10.1016/j.gaitpost.2012.07.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Burnett RS, Della Rocca GJ, Prather H, Curry M, Maloney WJ, Clohisy JC. Clinical presentation of patients with tears of the acetabular labrum. The Journal of bone and joint surgery. American volume. 2006;88(7):1448–1457. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.D.02806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Clark AG, Jordan JM, Vilim V, et al. Serum cartilage oligomeric matrix protein reflects osteoarthritis presence and severity: the Johnston County Osteoarthritis Project. Arthritis Rheum. 1999;42(11):2356–2364. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(199911)42:11<2356::AID-ANR14>3.0.CO;2-R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Clohisy JC, St John LC, Schutz AL. Surgical treatment of femoroacetabular impingement: a systematic review of the literature. Clinical orthopaedics and related research. 2010;468(2):555–564. doi: 10.1007/s11999-009-1138-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Conrozier T, Saxne T, Fan CS, et al. Serum concentrations of cartilage oligomeric matrix protein and bone sialoprotein in hip osteoarthritis: a one year prospective study. Ann Rheum Dis. 1998;57(9):527–532. doi: 10.1136/ard.57.9.527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ganz R, Leunig M, Leunig-Ganz K, Harris WH. The etiology of osteoarthritis of the hip: an integrated mechanical concept. Clinical orthopaedics and related research. 2008;466(2):264–272. doi: 10.1007/s11999-007-0060-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ganz R, Parvizi J, Beck M, Leunig M, Notzli H, Siebenrock KA. Femoroacetabular impingement: a cause for osteoarthritis of the hip. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2003;(417):112–120. doi: 10.1097/01.blo.0000096804.78689.c2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Garvican ER, Vaughan-Thomas A, Clegg PD, Innes JF. Biomarkers of cartilage turnover. Part 2: Non-collagenous markers. Veterinary journal (London, England : 1997) 2010;185(1):43–49. doi: 10.1016/j.tvjl.2010.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Goldring SR. Needs and opportunities in the assessment and treatment of osteoarthritis of the knee and hip: the view of the rheumatologist. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2009;91(Suppl 1):4–6. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.H.01443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Greenland P, Alpert JS, Beller GA, et al. 2010 ACCF/AHA guideline for assessment of cardiovascular risk in asymptomatic adults: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2010;56(25):e50–103. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2010.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Haffner SM. The metabolic syndrome: inflammation, diabetes mellitus, and cardiovascular disease. Am. J. Cardiol. 2006;97(2A):3A–11A. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2005.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ito K, Leunig M, Ganz R. Histopathologic Features of the Acetabular Labrum in Femoroacetabular Impingement. Clinical orthopaedics and related research. 2004;429:262–271. doi: 10.1097/01.blo.0000144861.11193.17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Klässbo M, Larsson E, Mannevik E. Hip disability and osteoarthritis outcome score. An extension of the Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index. Scandinavian journal of rheumatology. 2003;32(1):46–51. doi: 10.1080/03009740310000409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kraus VB. Osteoarthritis year 2010 in review: biochemical markers. Osteoarthritis and cartilage / OARS, Osteoarthritis Research Society. 2011;19(4):346–353. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2011.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kubiak-Langer M, Tannast M, Murphy SB, Siebenrock KA, Langlotz F. Range of motion in anterior femoroacetabular impingement. Clinical orthopaedics and related research. 2007;458:117–124. doi: 10.1097/BLO.0b013e318031c595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Larson CM, Sikka RS, Sardelli MC, et al. Increasing Alpha Angle is Predictive of Athletic-Related “Hip” and “Groin” Pain in Collegiate National Football League Prospects. Arthroscopy : the journal of arthroscopic & related surgery : official publication of the Arthroscopy Association of North America and the International Arthroscopy Association. 2013 doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2012.10.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lehmann TG, Engesæter IØ, Laborie LB, Lie SA, Rosendahl K, Engesæter LB. Total hip arthroplasty in young adults, with focus on Perthes disease and slipped capital femoral epiphysis: follow-up of 540 subjects reported to the Norwegian Arthroplasty Register during 1987-2007. Acta orthopaedica. 2012;83(2):159–164. doi: 10.3109/17453674.2011.641105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nepple JJ, Zebala LP, Clohisy JC. Labral disease associated with femoroacetabular impingement: do we need to correct the structural deformity? The Journal of arthroplasty. 2009;24(6 Suppl):114–119. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2009.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ng VY, Arora N, Best TM, Pan X, Ellis TJ. Efficacy of surgery for femoroacetabular impingement: a systematic review. The American Journal of Sports Medicine. 2010;38(11):2337–2345. doi: 10.1177/0363546510365530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ong KL, Wu BJ, Cheung BMY, Barter PJ, Rye K-A. Arthritis: its prevalence, risk factors, and association with cardiovascular diseases in the United States, 1999 to 2008. Ann Epidemiol. 2013;23(2):80–86. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2012.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pearson TA, Mensah GA, Alexander RW, et al. Markers of inflammation and cardiovascular disease: application to clinical and public health practice: A statement for healthcare professionals from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2003;Vol 107:499–511. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000052939.59093.45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Philippon MJ, Maxwell RB, Johnston TL, Schenker M, Briggs KK. Clinical presentation of femoroacetabular impingement. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2007;15(8):1041–1047. doi: 10.1007/s00167-007-0348-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Posey KL, Hecht JT. The role of cartilage oligomeric matrix protein (COMP) in skeletal disease. Current drug targets. 2008;9(10):869–877. doi: 10.2174/138945008785909293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Punzi L, Oliviero F, Plebani M. New biochemical insights into the pathogenesis of osteoarthritis and the role of laboratory investigations in clinical assessment. Critical reviews in clinical laboratory sciences. 2005;42(4):279–309. doi: 10.1080/10408360591001886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sharif M, Kirwan JR, Elson CJ, Granell R, Clarke S. Suggestion of nonlinear or phasic progression of knee osteoarthritis based on measurements of serum cartilage oligomeric matrix protein levels over five years. Arthritis Rheum. 2004;50(8):2479–2488. doi: 10.1002/art.20365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tanzer M, Noiseux N. Osseous abnormalities and early osteoarthritis: the role of hip impingement. Clinical orthopaedics and related research. 2004;(429):170–177. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tegner Y, Lysholm J. Rating systems in the evaluation of knee ligament injuries. Clinical orthopaedics and related research. 1985;(198):43–49. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ware JE, Kosinski M, Gandek B, et al. SF-12v2 Health Survey: Admin Guide for Clinical Trial Investigators. QualityMetric, Incorporated; 2010. [Google Scholar]