Abstract

Craniospinal irradiation (CSI) is associated with infertility risk for adolescent/young adult women. We explore two methods of reducing ovarian exposure: oophoropexy (surgical removal of the ovaries from the path of the X-ray beam) and proton therapy (to allow the beam to stop without exposing the ovaries/uterus). In the case discussed, oophoropexy followed by X-ray CSI reduced ovarian dose to that at which 50% of oocytes are expected to survive, and the patient appears to have viable oocytes; this technique did not reduce uterine dose. Proton therapy would have eliminated the ovarian and uterine dose and the need for oophoropexy.

Keywords: : craniospinal irradiation, oophoropexy, fertility preservation in cancer survivors, fertility after radiation, proton therapy

Radiation to the entire neuro-axis, generally referred to as craniospinal irradiation (CSI), is an integral component of therapy for a variety of central nervous system (CNS) tumors that may affect young people. Most of these tumors are associated with high cure rates, thus treatment results in potential risk for survivorship issues.1,2 Unfortunately for girls and young women, among these risks is decreased reproductive potential, largely a result of radiation that exits through the abdomen and pelvis during treatment of the spine.3 The radiation dose associated with premature ovarian failure is variable within the literature, but generally assumed to be quite low. Mathematical modeling factoring oocyte decay with age estimates the dose of radiation required to destroy 50% of human oocytes to be approximately 2 Gy(relative biologic effectiveness [RBE]),4 and an effective sterilizing dose (ESD, when 97.5% of oocytes will be destroyed) to range from 5 to 20 Gy(RBE). A lower ESD is associated with increasing age due to the decrease in ovarian follicles with age.5 Clinical recommendations vary, but include maintaining ovarian dose less than 3 Gy(RBE) in order to prevent radiation-related decreases in fertility.5 A dose of 3 Gy(RBE) would be expected to cause ovarian failure at age 33 for girls treated while aged 5–15 years old. The uterus is less sensitive to radiotherapy; however, risks of fetal loss and pre-term labor are recognized in women who received pelvic radiation in childhood,6 and doses of 14–30 Gy(RBE) are expected to increase the risk of uterine dysfunction.5 Unfortunately, these dose constraints, particularly for the ovaries, are far below the doses generally needed for the curative treatment of brain tumors affecting the craniospinal axis, which include a spinal radiation dose ranging from 23–40 Gy(RBE). Although the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) Practice Guidelines recommend consideration of oocyte cryopreservation for adolescent and young adult (AYA) patients prior to cancer treatment,7 most tumors for which CSI is utilized require treatment in a relatively short time from diagnosis; as such, allowing time for oocyte harvest is often not practical. Furthermore, cryopreservation of ovarian tissue does not address the fertility risk associated with uterine exposure.

Interestingly, risk of ovarian damage from radiation appears to increase with age, so reproductive and hormonal consequences of abdominopelvic radiation are somewhat unique to female AYA patients requiring CSI.8 Although ASCO guidelines recommend that fertility issues be discussed with all post-pubertal AYA cancer patients prior to beginning treatment, oncologists cite lack of time, lack of knowledge, and discomfort in discussing fertility and sexuality as reasons that many do not provide adequate counseling regarding fertility preservation options.9 As such, many female patients report that fertility issues are not addressed before treatment initiation, and that even when these issues are addressed, discussions are not satisfactory to them.10 Here we outline potential options for ovarian and uterine sparing during CSI and review a pertinent case of a patient who received multidisciplinary treatment to this end.

Methods of Reducing Oocyte Exposure to Radiotherapy

The goal of all radiation therapy is to deliver the radiation dose to the areas of gross tumor or risk for presence of microscopic tumor cells and to avoid delivery of radiation to organs at risk (OARs). For the purposes of this discussion, we will consider the ovaries and uterus as OARs, and the brain and spine as areas of gross tumor and regions at risk. General options for ovary and uterus-sparing generally take one of two approaches: either the OARs may be separated physically in space from the radiation beam, or advanced radiation techniques and technologies may be used to avoid dose delivery to OARs. Common surgical approaches to remove the ovaries from regions of radiation dose include oophoropexy and ovarian transposition. In order to reduce ovarian radiation exposure during CSI, the ovaries can be moved anterolaterally or inferiomedially. The anterolateral approach often involves moving one or both ovaries and transecting the fallopian tube.11 Moving the ovaries away from the radiation field has been shown to decrease dose to the ovaries in the setting of CSI.12,13 Successful return of ovarian function after transposition has been reported,14,15 but surgical techniques that involve fallopian tube transection may prevent unassisted conception and require patients to undergo in vitro fertilization for successful pregnancy to occur. The movement of the ovaries inferiorly may allow intact preservation of the fallopian tubes, potentially allowing achievement of natural pregnancy as well as oocyte preservation.

Aside from surgical approaches to protect the ovaries during radiation, radiation techniques to achieve the same end have been explored in some depth. The simplest of these is an ovarian block—a physical block used in an attempt to prevent radiation from entering the true pelvis, where the ovaries are located. During craniospinal irradiation, the entire pelvis cannot be blocked from radiation without the potential for also shielding tumor cells within the lower thecal sac; additionally, even in the best of settings, such blocks have been shown to offer poor ovarian protection due to the mobility of the pelvic anatomy.16 Other groups have demonstrated that careful identification of the ovaries during CSI planning using magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) may allow at least one ovary to be shielded during the delivery of radiotherapy.17,18 The use of more complex X-ray planning techniques, such as intensity-modulated radiation therapy (IMRT), has also been examined. During IMRT planning, the ovaries and other organs may be designated as “avoidance” organs, and the radiation dose to them reduced through a complex series of algorithms. Although IMRT is highly beneficial for reducing dose to many organs, its capacity to reduce dose meaningfully for a tissue as radiosensitive as the oocyte is quite limited, and ovarian exposure during CSI is likely to exceed 3–5 Gy(RBE) even when IMRT is utilized.19

Proton therapy is being used for the delivery of CSI at several centers around the United States, and has been shown to allow reduction in the radiation dose delivered to visceral organs anterior to the spinal cord.20–22 Proton therapy is not available at all centers where pediatric and AYA patients are treated, and craniospinal treatment, which is resource- and time-intensive, is not available at every proton center. In the case below, we outline and compare two of the most viable options for fertility preservation during CSI—oophoropexy for removal of the ovaries from the photon exit dose and proton therapy to eliminate this exit dose entirely. Of note, fertility may be affected by cranial radiation through disruption of the hypothalamic/pituitary axis and/or by other treatments, such as chemotherapy, required by this population. As such, reduction of radiation dose to the ovaries and uterus may not result in normal fertility for all girls and women receiving CSI. Certainly, however, preservation of pelvic fertility organs is expected to increase fertility options for all survivors after this type of treatment.

Case Report

An 18-year-old female was diagnosed with disseminated germinoma requiring craniospinal irradiation to 36 Gy(RBE) as the sole modality for curative treatment. Options for fertility preservation were discussed; the patient declined ovarian stimulation and elected laparoscopic oophoropexy. Prior to surgery, the patient's imaging was reviewed jointly by the radiation oncology and reproductive endocrinology teams, and the decision was made to relocate the ovaries inferiorly and medially, to the level of the uterosacral ligament. The patient underwent laparoscopic oophoropexy during which three ports were placed: a 5 mm port at the umbilicus, a 10 mm suprapubic port, and a 5 mm port in the left lower quadrant. Each ovary was moved inferiomedially and sutured to the ipsilateral uterosacral ligament. Two titanium hemoclips were placed on each ovary to allow for radiologic visualization.

Radiation treatment planning, delivery, and recovery

Delivery of CSI with protons was not available at our center at the time of diagnosis. Computed tomography (CT) simulation for X-ray CSI was performed both before and after moving the ovaries; the patient was positioned prone and immobilized in an aquaplast mask with arms at her sides. CT simulation images were obtained in 3 mm increments and images were transferred to the Eclipse treatment planning software version 8.9.09 (Varian; Palo Alto, CA). The uterus and ovaries were then contoured, along with other treatment structures and OARs. Standard craniospinal treatment fields using 6 MV photons were designed using opposed lateral fields to treat the entire brain, matched to two posterior-anterior (PA) spinal fields. A total of 36 Gy(RBE) in 1.8 Gy(RBE) fractions was prescribed to the entire craniospinal axis.

The patient tolerated radiation very well, with minimal acute toxicity. She did not require chemotherapy. She remained without evidence of disease 30 months from completion of her radiation. At 18 months from the completion of treatment, pelvic ultrasound demonstrated 20 antral follicles; her anti-Müllerian hormone level was 1.1 ng/ml, signifying preserved ovarian reserve and potential for natural pregnancy.

Proton therapy planning dose comparison

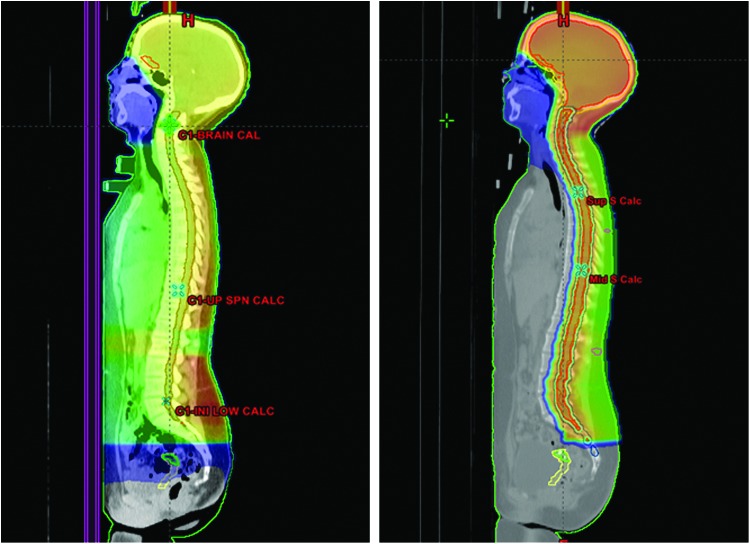

In order to evaluate ovarian and uterine dosimetry during proton-based CSI, proton plans were developed for the patient retrospectively, as proton therapy was not available at the time of her treatment and so this treatment could not be offered to her. Passively scattered PA proton fields were planned for the spinal portion of the treatment, reducing exit dose to all anterior visceral organs (Fig. 1).

FIG. 1.

Radiation dose distribution of craniospinal radiation plans using X-rays (left) and protons (right) for an adolescent girl receiving 36 Gy(RBE) to the craniospinal axis. The color-washed areas represent all areas receiving 0.5 Gy(RBE) or greater radiation dose. The uterus contour is outlined in yellow and the ovaries after oophoropexy are in green. Note the elimination of radiation dose to the uterus and other pelvic organs through use of proton therapy. RBE, relative biologic effectiveness.Color images available online at www.liebertpub.com/jayao

Radiation dose comparison

Post-oophoropexy, the patient was treated with X-ray CSI. The maximum ovarian dose was 2.5 Gy(RBE) and the maximum uterine dose was 3.4 Gy(RBE). The post-oophoropexy ovarian dose represented a decrease from the 3.8 Gy(RBE) maximum dose if no surgical procedure had been utilized and the patient had been treated with X-ray therapy to the spine. When proton plans were generated for treatment of her spine, the dose to the ovaries was essentially 0 in both the pre- and post-operative positions; the uterine dose was also essentially 0 (Table 1).

Table 1.

Maximum Radiation Doses to Ovaries and Uterus After Craniospinal Radiation Using X-Rays Versus Proton Beam Therapy

| Ovarian max | Ovarian mean | Uterine max | Uterine mean | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-oophoropexy X-rays | 3.8 Gy(RBE) | 1.7 Gy(RBE) | ||

| Post-oophoropexy X-rays | 2.5 Gy(RBE) | 1.3 Gy(RBE) | 3.4 Gy(RBE) | 1.1 Gy(RBE) |

| Pre-oophoropexy protons | 0.003 Gy(RBE) | 0.001 Gy(RBE) | ||

| Post-oophoropexy protons | 0.003 Gy(RBE) | 0.001 Gy(RBE) | 0.004 Gy(RBE) | 0.001 Gy(RBE) |

RBE, relative biologic effectiveness.

Summary and Conclusions

Proton therapy offers an elegant method of essentially eliminating dose delivery to the ovaries and uterus during CSI, and eliminates the need for any ovary-preserving surgical procedure. The patient described here was treated prior to the availability of proton therapy at our center. Her treatment with X-ray therapy following oophoropexy with inferiomedial relocation of the ovaries reduced the maximum ovarian radiation dose from nearly 4 Gy(RBE) to 2.5 Gy(RBE). The resulting dose is that at which a significant portion of oocytes would be expected to be viable; this was confirmed by her follow-up endocrinology studies demonstrating good ovarian reserve. Proton therapy would have reduced the dose to her ovaries and uterus by 1000-fold and likely resulted in less risk of ultimate fertility concerns. The patient's maximum uterine dose of 3.4 Gy with X-ray CSI is not expected to result in uterine dysfunction, although it was also reduced by 1000-fold on the proton CSI plan, and certainly 0 radiation dose is an improvement when any sensitive organs are concerned. As a result of these investigations and a review of the literature, we conclude that: (1) proton therapy has strong potential for fertility preservation through elimination of dose to ovaries and uterus during craniospinal irradiation for adolescent girls and women and (2) oophoropexy with X-ray-based spinal radiation is an acceptable alternative that appears to protect oocyte viability and hormone function when protons are not available. Further work on ultimate fertility and ability to bear children after proton CSI will be of utmost interest in the future.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Dr. Evan Spiegelman of the Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania, Department of Radiology, for his extensive review of the pelvic imaging obtained for this patient during treatment planning and conduction of this study.

Disclaimer

This paper was presented in part at the American Society for Radiation Oncology 54th Annual Meeting, October 28–31, 2012, Boston, Massachusetts, USA (Lester-Coll NH, Morse CB, Zhai HA, et al. “Proton therapy for sparing fertility in girls requiring craniospinal irradiation: is there a role for ooophoropexy?”).

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.Wolden SL, Wara WM, Larson DA, et al. Radiation therapy for primary intracranial germ-cell tumors. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1995;32(4):943–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Packer RJ, Gajjar A, Vezina G, et al. Phase III study of craniospinal radiation therapy followed by adjuvant chemotherapy for newly diagnosed average-risk medulloblastoma. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24(25):4202–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wallace WH, Shalet SM, Tetlow LJ, Morris-Jones PH. Ovarian function following the treatment of childhood acute lymphoblastic leukaemia. Med Pediatr Oncol. 1993;21(5):333–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wallace WH, Thomson AB, Kelsey TW. The radiosensitivity of the human oocyte. Hum Reprod. 2003;18(1):117–21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wallace WH, Thomson AB, Saran F, Kelsey TW. Predicting age of ovarian failure after radiation to a field that includes the ovaries. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2005;62(3):738–44 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Signorello LB, Mulvihill JJ, Green DM, et al. Stillbirth and neonatal death in relation to radiation exposure before conception: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet. 2010;376(9741):624–30 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Loren AW, Mangu PB, Beck LN, et al. Fertility preservation for patients with cancer: American Society of Clinical Oncology clinical practice guideline update. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31(19):2500–10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nicholson HS, Byrne J. Fertility and pregnancy after treatment for cancer during childhood or adolescence. Cancer. 1993;71(10 Suppl):3392–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Johnson RH, Kroon L. Optimizing fertility preservation practices for adolescent and young adult cancer patients. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2013;11(1):71–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yeomanson DJ, Morgan S, Pacey AA. Discussing fertility preservation at the time of cancer diagnosis: dissatisfaction of young females. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2013;60(12):1996–2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Morice P, Castaigne D, Haie-Meder C, et al. Laparoscopic ovarian transposition for pelvic malignancies: indications and functional outcomes. Fertil Steril. 1998;70(5):956–60 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tulandi T, Al-Took S. Laparoscopic ovarian suspension before irradiation. Fertil Steril. 1998;70(2):381–3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mitchell JD, Hitchen C, Vlachaki MT. Role of ovarian transposition based on the dosimetric effects of craniospinal irradiation on the ovaries: a case report. Med Dosim. 2007;32(3):204–10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Morice P, Thiam-Ba R, Castaigne D, et al. Fertility results after ovarian transposition for pelvic malignancies treated by external irradiation or brachytherapy. Hum Reprod. 1998;13(3):660–3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Thibaud E, Ramirez M, Brauner R, et al. Preservation of ovarian function by ovarian transposition performed before pelvic irradiation during childhood. J Pediatr. 1992;121(6):880–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fawcett SL, Gomez AC, Barter SJ, et al. More harm than good? The anatomy of misguided shielding of the ovaries. Br J Radiol. 2012;85(1016):e442–7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shigematsu N, Shinmoto H, Ito N, et al. Successful pregnancy and normal delivery after whole craniospinal irradiation in two patients. Anticancer Res. 2005;25(5):3481–7 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Harden SV, Twyman N, Lomas DJ, et al. A method for reducing ovarian doses in whole neuro-axis irradiation for medulloblastoma. Radiother Oncol. 2003;69(2):183–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pérez-Andújar A, Newhauser WD, Taddei PJ, et al. The predicted relative risk of premature ovarian failure for three radiotherapy modalities in a girl receiving craniospinal irradiation. Phys Med Biol. 2013;58(10):3107–23 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yoon M, Shin DH, Kim J, et al. Craniospinal irradiation techniques: a dosimetric comparison of proton beams with standard and advanced photon radiotherapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2011;81(3):637–46 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Howell RM, Giebeler A, Koontz-Raisig W, et al. Comparison of therapeutic dosimetric data from passively scattered proton and photon craniospinal irradiations for medulloblastoma. Radiat Oncol. 2012;7:116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kumar RJ, Zhai H, Both S, et al. Breast cancer screening for childhood cancer survivors after craniospinal irradiation with protons versus x-rays: a dosimetric analysis and review of the literature. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2013;35(6):462–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]