Abstract

We investigated whether microglia form gap junctions with themselves, or with astrocytes, oligodendrocytes, or neurons in vivo in normal mouse brains, and in pathological conditions that induce microglial activation - brain injury, a model of Alzheimer’s disease. Although microglia are in close physical proximity to glia and neurons, they do not form functional gap junctions under these pathological conditions.

Introduction

Gap junctions (GJs) are intercellular channels between apposed cells that permit the diffusion of ions and small molecules typically less than 1000 Da (Bruzzone et al., 1996). In vertebrates, GJs are comprised of a family of integral membrane proteins known as connexins (Cxs) that are named according to their predicted molecular mass (Willecke et al., 2002). The traditional view was that astrocytes are coupled to each other (A:A coupling) by Cx43:Cx43 and Cx30:Cx30 homotypic channels, and to oligodendrocytes (A:O coupling) by heterotypic Cx47:Cx43 and/or Cx32:Cx30 channels (Altevogt and Paul, 2004;Mugnaini, 1986;Nagy and Rash, 2000; Nagy and Rash, 2003; Nagy et al., 2003; Orthmann-Murphy et al., 2007;Rash et al., 2001a;Rash et al., 2001b). Dye transfer studies in acute brain slices confirmed A:A, and A:O coupling through Cx47:Cx43, and also demonstrated direct O:O coupling by Cx32:Cx32 and Cx47:Cx47 homotypic channels (Maglione et al., 2010;Wasseff and Scherer, 2011).

A number of reports indicate that microglia express connexins, and/or form GJs in vitro (Dobrenis et al., 2005;Eugenin et al., 2001; Garg et al., 2005; Martinez et al., 2002; Saez et al., 2013). Accordingly, we sought to address how microglia interact with the CNS panglial syncytium in vivo under normal and pathological conditions that activate microglia - brain injury, a model of Alzheimer disease, and following activation by lipopolysaccharide (LPS) injection. Our dye transfer studies indicate that microglia do not form functional GJs with themselves, astrocytes, oligodendrocytes, or neurons in vivo in normal brain or in these models.

Methods

Animals

We used B6.129P-Cx3cr1tm1Litt/J mice (also referred to as CX3CR1-EGFP; Jackson laboratory), in which the Egfp gene in knocked into the Cx3cr1 locus. In these mice, microglia are the only cells in the CNS that express EGFP since they are the only CNS cells that express the fractalkine receptor (CX3CR1) (Jung et al., 2000).

To induce traumatic brain injury, P16 -P20 mice were anesthetized with a mixture of ketamine/xylazine, a small burr hole was drilled through the skull over the cerebrum, and a 25 gauge needle was inserted 3–4 times through the hole, and then the wound was closed with sutures (Levine, 1994). To generate Alzheimer mice model expressing EGFP in microglia, CX3CR1-EGFP mice were crossed with transgenic mice that express the P301S mutant human microtubule-associated protein tau, MAPT, referred to as P301S (Yoshiyama et al., 2007). To induce activation by LPS, P20 mice were injected by LPS (0.5mg/kg, IP injection; Sigma) as previously described (Kondo et al., 2011).

Electrophysiology

All experiments were conducted using an Olympus BX51WI fixed stage microscope, fitted with infrared differential interference contrast (IR-DIC), and videomicroscopy through an Olympus DP-71 color camera using DP-71 software. The whole cell recordings were conducted using a Model 2400 amplifier (A-M systems); signals were digitized using National Instruments USP interface card, and analyzed using WCP software (version 4.0.7, John Dempster, Department of Physiology & Pharmacology, University of Strathclyde, Scotland). Acute brain slices were prepared as previously reported (Wasseff and Scherer, 2011), and slices were incubated in oxygenated (95% O2-5%CO2), artificial cerebrospinal fluid (ACSF) composed of 119 mM NaCl, 2.5 mM KCl, 1.0 mM NaH2PO4, 1.3 mM MgSO4, 2.5 mM CaCl2, 11 mM dextrose, and 26.2 mM NaHCO3 (pH 7.4, 295–305 mOsm). For whole cell studies, electrodes were filled with a solution composed of 105 mM K-gluconate, 30 mM KCL, 0.3 mM EGTA, 10 mM HEPES, 10 mM phosphocreatine, 4 mM ATP-Mg2, 0.3 mM GTP-Tris, with 0.1% Sulforhodamine-B (SR-B; MW 559; Invitrogen).

Immunohistochemistry

Briefly, wounded P20 mice were euthanized 4 days following injury, perfused with 4% paraformaldehyde, processed and immunostained using rabbit antibody against Cx43 (1:2,000; Sigma) as previously described (Wasseff et al., 2011).

Results

Microglia do not form GJs with the panglial syncytium in normal mice, and do not form GJs following activation

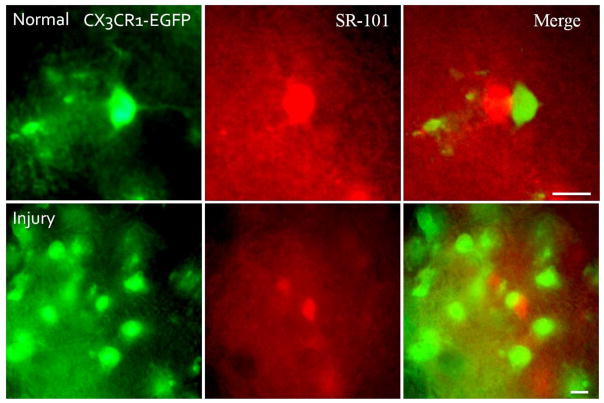

To determine whether microglia form functional GJs with the panglial syncytium, we examined the neocortex of P20 CX3CR1-EGFP mice (n=3) by incubating the brain slices in 0.1% sulforhodamine-101 (SR-101; MW 559; Invitrogen) for 20 min. This fluorescent dye is taken by astrocytes in connexins independent manner and diffuses in the glial syncytium including oligodendrocytes through GJs (Nimmerjahn et al., 2004;Wasseff and Scherer, 2011). Despite the close proximity of microglia and SR-101 positive glial cells in the glial syncytium, there was no SR-101 diffusion from the glial syncytium to microglia (Fig. 1; upper panels).

Figure 1. Microglia do not form GJs with the CNS syncytium in vivo following injury.

These are digital images of neocortex from a normal P20 CX3CR1-EGFP mouse (upper panels) and a CX3CR1-EGFP mouse 4 days after stab wounds (lower panels). The sections were imaged with FITC, to visualize EGFP in microglia (left panels), and TRITC, to visualize sulforhodmine-101 (SR-101) in the glial syncytium (middle panels). Scale bars: 10 um. SR-101 labeled the glial syncytium (astrocytes and oligodendrocytes), but did not diffuse into microglia despite their close proximity, either in normal neocortex or following traumatic injury.

Wounding the brain has been reported to result in diffuse intracellular Cx43-immunoreactivity in microglia 4–7 days following injury (Eugenin et al., 2001). These findings motivated us to determine whether microglia form functional GJs following injury. So we injured the neocortex of P16 to P20 CX3CR1-EGFP mice (n=6), and after 4–7 days, incubated the brain slices at the site of injury in SR-101. The site of injury showed extensive microglia infiltration (Fig. 1; lower panels), and similar to uninjured mice, despite the close proximity of microglia and SR-101 positive glial cells in the glial syncytium, there was no SR-101 diffusion from the glial syncytium to microglia (Fig. 1; lower panels).

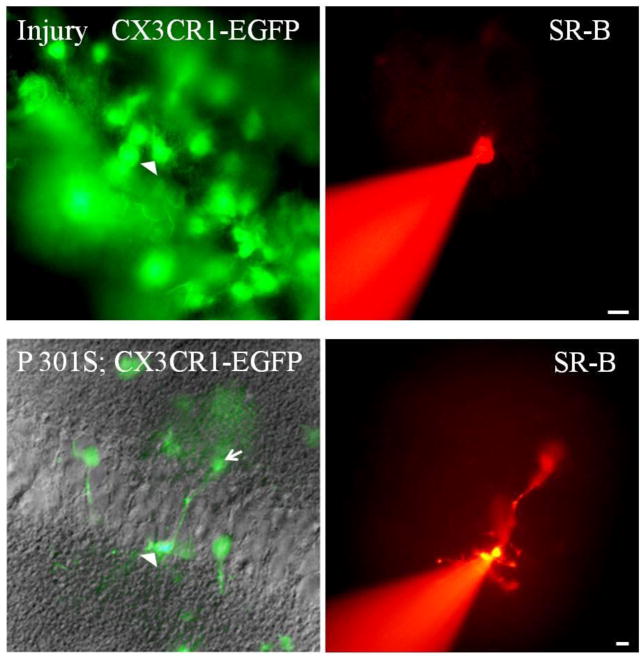

These results contradict the expectation that microglial are GJ-coupled after traumatic brain injury. To investigate this issue further, we patched individual EGFP-positive microglia in brain slices from the same animals (1–2 cells from each mouse, Fig. 2) with an electrode containing SR-B. Like SR-101, SR-B is a small fluorescence dye that can diffuse through A:A, A:O, and O:O GJs (Kafitz et al., 2008;Wasseff and Scherer, 2011). We did not observe transfer of SR-B between the injected cell and any other cell, including EGFP-positive microglia (Fig. 3; upper panels). In these mice A:O and O:O coupling remain intact (data not shown).

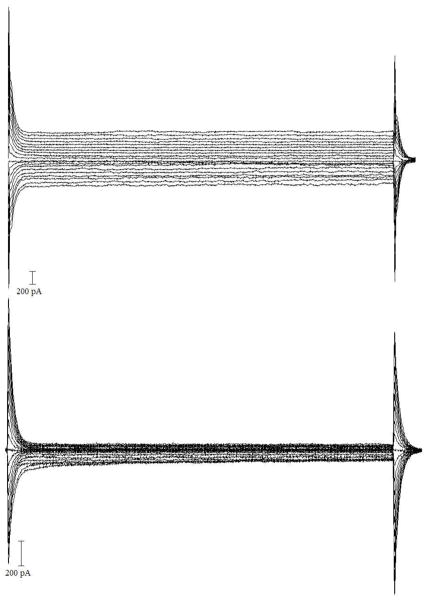

Figure 2. Volatge -dependent electrophysiological properties of microglia before after injury.

Examples of current responses induced by 20 voltage steps of 10 mV increment from −160 to +30 mV (holding potential, −70 mV) in microglia cells of uninjured P20 CX3CR1-EGFP mouse (upper traces) and 4 days after injury (lower traces).

Figure 3. Microglia do not form functional GJs after neocortical injury or in P301S mice.

These are digital images of acute slice of neocortex from CX3CR1-EGFP mice. The sections were imaged with FITC, with (lower panel) or without (upper panel) DIC optics, to visualize EGFP in microglia (left panels), and TRITC, to visualize Sulforhodamine-B (SR-B; right panels). Scale bars: 10 um. The uppers panels are taken from the neocortex of P24 mice 4 days after injury. An EGFP- positive microglia (marked by the arrowhead) was patched with an electrode containing SR-B and visualized for 20 min. SR-B did not diffuse into any of the surrounding brain cells. The lower panels are taken from a 105 days old P301S mouse. EGFP-positive microglia have extensive branching in the stratum pyramidale in the hippocampus. One EGFP–positive microglia (marked by the arrowhead) and it is processes (marked by arrow) was patched with an electrode containing SR-B and visualized for 20 min. SR-B diffused into the processes of the patched cell (arrow) but did not diffuse into any of the surrounding neurons or glial cells.

We also examined whether activated microglia can form functional GJs in the P301S model of Alzheimer disease, in which microglial activation occurs at 3 months of age (Yoshiyama et al., 2007). Microglia can be seen in the hippocampus with process extending between the pyramidal cells. We patched individual microglia (2 cells/mouse) with an electrode containing SR-B in the hippocampi of a 105 and a 237 day-old P301S mouse. We did not detect dye coupling between the microglia and themselves or any other neuronal or glial cell (Fig 3; lower panels); instead the dye was localized to the microglia cell body and its process. Incubating sections with SR-101 (5–10 sections/mouse) also failed to demonstrate GJ coupling between the microglia and the panglial syncytium (data not shown). In the P301S mice A:O and O:O coupling remain present.

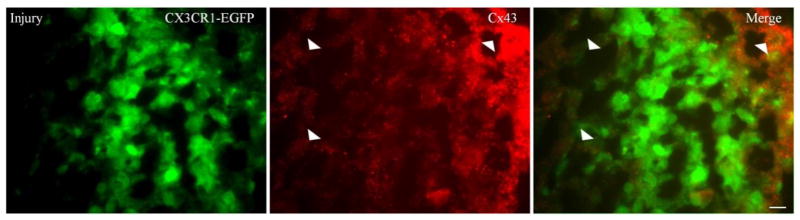

We sought to analyze whether the absence of dye transfer seen in the wounded mice is the result of lack of Cx43 at apposing cells, so we immunostained for Cx43 four days after injury. We did not see Cx43 GJs plaques between microglia, at the cell -cell interfaces, at the site of the injuries (Fig. 4). Although we found a diffuse up regulation of C x43 in the in surrounding uninjured cortex of wounded mice compared to uninjured littermates controls (n=2).

Figure 4. Microglia do not form Cx43 GJs plaques at the site of injury.

These are digital images of neocortex from a P24 CX3CR1-EGFP mouse 4 days after stab wounds. The sections were imaged with FITC, to visualize EGFP in microglia (left panels), and TRITC, to visualize Cx43 (middle panels). 10 um thick cryostate sections were immunostained for Cx43 using rabbit antiCx43 as a primary antibody, and TRITC-conjugated donkey anti rabbit as secondary antibody (1:200 dilution; Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories). Slides were mounted with Vectorshield and examined by epifluorescence (Leica DMR). Scale bars: 10 um. Merged images (right panel) show that EGFP-positive microglia did not form Cx43 GJs plaques. Cx43 up regulation can be seen more outside the site of injury compared to the site of injury (arrowheads). While up regulation of Cx43 can be seen on the surface of some microglia, these might reflect astrocytic end feet.

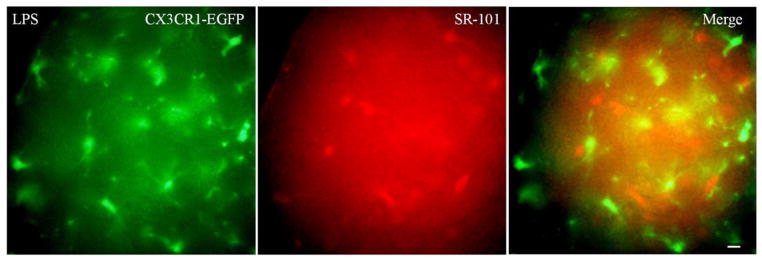

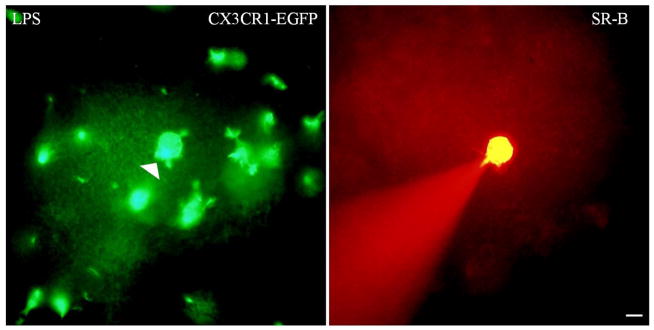

Because studies conducted in vitro utilized LPS to activate microglia, we injected P20 mice with LPS (0.5mg/kg, IP, n=3) and examined them using SR-101 incubation, and using electrodes containing SR-B (1–3 cells/mouse).We did not detect dye coupling between the microglia and themselves or any other cell (Fig 5).

Figure 5. Microglia do not form functional GJs with the CNS syncytium in vivo following LPS injection.

These are digital images of neocortex from CX3CR1-EGFP mouse. P20 mice were IP injected with 0.5mg/kg LPS to activate microglia and examined 2 days later. The sections were imaged with FITC, to visualize EGFP in microglia (left panel), and TRITC, to visualize sulforhodmine-101 (SR-101) in the glial syncytium (middle panel). Scale bar: 10 um. SR-101 labeled the glial syncytium but did not diffuse into microglia (right panel).

Discussion

Our studies contrast to the prior work done in cell culture. Eugenin et al. (2001) reported dye coupling in activated microglia cultured from wild type mice but not Gja1/Cx43-null mice. Similarly, activated microglia by Staphylococcus aureus-derived peptidoglycan were reported to express Cx43 and showed some dye transfer (Garg et al., 2005;Kielian, 2008). These studies reported GJs coupling as incidence of coupling, rather than number of coupled cells, shown as dye transfer between microglia and only one additional cell (Garg et al., 2005;Saez et al., 2013), but did not demonstrate a diffuse dye transfer to many cells such as what is seen between Cx43 coupled astrocytes or myocytes in vitro. By contrast to the transgenic line we used which confirm that EGFP- positive cells are microglia, there was no post injection immunostaining to confirm the type of the coupled cells that they were indeed microglia. Because electrophysiology cannot differentiate the activated microglia from the inactive ones (Khanna et al., 2001) we resorted to the SR-101 incubation approach and it confirmed that none of the EGFP-positive cells formed functional GJs. Prior work done in cell culture reported an increase in Cx43 immunoreactivity, but did not demonstrate obvious plaques at apposing cell membranes (Garg et al., 2005;Saez et al., 2013). Eugenin et al. (2001) also reported Cx43 positive immunoreactivity seen as diffuse intracellular labeling with more intense staining at some cell interfaces in injured rat brains. We did not find Cx43 plaques between microglia, and we did not find Cx43 upregulation at the site of injury. We did however observe an upregulation in Cx43 in surrounding uninjured cortex in the wounded mice.

Finally, a previous report (Dobrenis et al., 2005) also indicated that cultured human microglial express Cx36 mRNA, and low levels dye transfer studies in cultures indicated the existence of GJs between microglia themselves, and between microglia and neurons. Our data, in contrast, do not support the idea that microglia form functional gap junctions in vivo, even under pathological conditions that activate them.

Figure 6. Microglia do not form functional GJs with each other after LPS injection.

These are digital images of acute slice of neocortex from CX3CR1-EGFP mice. The sections were imaged with FITC to visualize EGFP in microglia (left panel), and TRITC, to visualize Sulforhodamine-B (SR-B; right panel). Scale bar: 10 um. An EGFP- positive microglia (marked by the arrowhead) was patched with an electrode containing SR-B and visualized for 20 min. SR-B did not diffuse into any of the surrounding EGFP-positive cells.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Altevogt BM, Paul DL. Four classes of intercellular channels between glial cells in the CNS. J Neurosci. 2004;24:4313–4323. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3303-03.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruzzone R, White TW, Paul DL. Connections with connexins: the molecular basis of direct intercellular signaling. Eur J Biochem. 1996;238:1–27. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1996.0001q.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dobrenis K, Chang HY, Pina-Benabou MH, Woodroffe A, Lee SC, Rozental R, Spray DC, Scemes E. Human and mouse microglia express connexin36, and functional gap junctions are formed between rodent microglia and neurons. J Neurosci Res. 2005;82:306–315. doi: 10.1002/jnr.20650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eugenin EA, Eckardt D, Theis M, Willecke K, Bennett MV, Saez JC. Microglia at brain stab wounds express connexin 43 and in vitro form functional gap junctions after treatment with interferon-gamma and tumor necrosis factor-alpha. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:4190–4195. doi: 10.1073/pnas.051634298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garg S, Md Syed M, Kielian T. Staphylococcus aureus-derived peptidoglycan induces Cx43 expression and functional gap junction intercellular communication in microglia. J Neurochem. 2005;95:475–483. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2005.03384.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jung S, Aliberti J, Graemmel P, Sunshine MJ, Kreutzberg GW, Sher A, Littman DR. Analysis of fractalkine receptor CX(3)CR1 function by targeted deletion and green fluorescent protein reporter gene insertion. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20:4106–4114. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.11.4106-4114.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kafitz KW, Meier SD, Stephan J, Rose CR. Developmental profile and properties of sulforhodamine 101--Labeled glial cells in acute brain slices of rat hippocampus. J Neurosci Methods. 2008;169:84–92. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2007.11.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khanna R, Roy L, Zhu X, Schlichter LC. K+ channels and the microglial respiratory burst. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2001;280:C796–806. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.2001.280.4.C796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kielian T. Glial connexins and gap junctions in CNS inflammation and disease. J Neurochem. 2008;106:1000–1016. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2008.05405.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kondo S, Kohsaka S, Okabe S. Long-term changes of spine dynamics and microglia after transient peripheral immune response triggered by LPS in vivo. Mol Brain. 2011;4 doi: 10.1186/1756-6606-4-27. 27-6606-4-27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levine JM. Increased expression of the NG2 chondroitin-sulfate proteoglycan after brain injury. J Neurosci. 1994;14:4716–4730. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.14-08-04716.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maglione M, Tress O, Haas B, Karram K, Trotter J, Willecke K, Kettenmann H. Oligodendrocytes in mouse corpus callosum are coupled via gap junction channels formed by connexin47 and connexin32. Glia. 2010;58:1104–1117. doi: 10.1002/glia.20991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez AD, Eugenin EA, Branes MC, Bennett MV, Saez JC. Identification of second messengers that induce expression of functional gap junctions in microglia cultured from newborn rats. Brain Res. 2002;943:191–201. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(02)02621-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mugnaini E. In: Astrocytes. Fedoroff S, Vernadakis A, editors. Vol. 1. Academic Press; Orlanodo florida: 1986. pp. 329–371. [Google Scholar]

- Nagy JI, Rash JE. Connexins and gap junctions of astrocytes and oligodendrocytes in the CNS. Brain Res Brain Res Rev. 2000;32:29–44. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0173(99)00066-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cx47: Implications from normal and connexin32 knockout mice. Glia. 44:205–218. doi: 10.1002/glia.10278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nimmerjahn A, Kirchhoff F, Kerr JN, Helmchen F. Sulforhodamine 101 as a specific marker of astroglia in the neocortex in vivo. Nat Methods. 2004;1:31–37. doi: 10.1038/nmeth706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rash JE, Yasumura T, Dudek FE, Nagy JI. Cell-specific expression of connexins and evidence of restricted gap junctional coupling between glial cells and between neurons. J Neurosci. 2001a;21:1983–2000. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-06-01983.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saez PJ, Shoji KF, Retamal MA, Harcha PA, Ramirez G, Jiang JX, von Bernhardi R, Saez JC. ATP is required and advances cytokine-induced gap junction formation in microglia in vitro. Mediators Inflamm. 2013;2013:216402. doi: 10.1155/2013/216402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wasseff S, Abrams CK, Scherer SS. A dominant connexin43 mutant does not have dominant effects on gap junction coupling in astrocytes. Neuron Glia Biol. 2011:1–11. doi: 10.1017/S1740925X11000019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wasseff SK, Scherer SS. Cx32 and Cx47 mediate oligodendrocyte:astrocyte and oligodendrocyte:oligodendrocyte gap junction coupling. Neurobiol Dis. 2011 doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2011.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willecke K, Eiberger J, Degen J, Eckardt D, Romualdi A, Guldenagel M, Deutsch U, Sohl G. Structural and functional diversity of connexin genes in the mouse and human genome. Biol Chem. 2002;383:725–737. doi: 10.1515/BC.2002.076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshiyama Y, Higuchi M, Zhang B, Huang SM, Iwata N, Saido TC, Maeda J, Suhara T, Trojanowski JQ, Lee VM. Synapse loss and microglial activation precede tangles in a P301S tauopathy mouse model. Neuron. 2007;53:337–351. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]