Abstract

Background

When a neuropsychiatric symptom due to encephalopathy develops in a patient with anti-thyroid antibodies, especially when the symptom is steroid-responsive, Hashimoto's encephalopathy (HE) needs to be included in the differential diagnosis of the patient. Although HE is an elusive disease, it is thought to cause various clinical presentations including seizures, myoclonus, and epilepsia partialis continua (EPC).

Case Report

We present the case of a 33-year-old Japanese woman who acutely developed EPC in the right hand as an isolated manifestation. A thyroid ultrasound showed an enlarged hypoechogenic gland, and a thyroid status assessment showed euthyroid with high titers of thyroid antibodies. A brain MRI revealed a nodular lesion in the left precentral gyrus. Corticosteroid treatment resulted in a cessation of the symptom.

Conclusions

A precentral nodular lesion can be responsible for steroid-responsive EPC in a patient with anti-thyroid antibodies and may be caused by HE. The serial MRI findings of our case suggest the presence of primary demyelination, with ischemia possibly due to vasculitis around the demyelinating lesion.

Key Words: Hashimoto's encephalopathy, Epilepsia partialis continua, Vasculitis, Demyelination, MRI, Hashimoto's disease

Background

Epilepsia partialis continua (EPC) is a rare form of focal status epilepticus and is characterized by rapidly recurring seizures that can last for hours, days, weeks, or even longer. It mainly differs from other types of motor seizures and localization-related status epilepticus types in the particular physiology of the primary sensorimotor cortex, which restricts the extent of discharges through a long-loop reflex mechanism. EPC is often resistant to anti-epileptic drugs and corticosteroid therapy [1].

On the other hand, Hashimoto's encephalopathy (HE) is a rare autoimmune disease characterized by high titers of anti-thyroid antibodies and a variety of neuropsychological disturbances [2]. Since there is no specific method for diagnosing HE, its diagnosis depends on the exclusion of other etiologies such as infectious, metabolic, toxic, vascular, neoplastic and paraneoplastic causes. MRIs in patients with HE are usually normal [3], but in several cases MRI findings of diffuse or focal white matter changes have been reported.

Clinical symptoms of HE are non-specific, and the disease course varies ranging from acute, subacute, chronic, progressive to relapsing-remitting [4, 5]. HE patients often present with involuntary movement that includes tremor (80%), myoclonus (65%) or seizures (60%); however, EPC in HE is rare [3, 6]. Herein we report the unique case of a patient with anti-thyroid antibodies who presented with steroid-responsive EPC and a contra-lateral frontal nodular lesion involving the motor cortex.

Case Presentation

A previously healthy 33-year-old Japanese woman presented with involuntary muscle twitch in the right hand in October 2011. She had had low-grade fever for a month before the onset of the neurological symptom. Her involuntary movement gradually aggravated, and she visited a local hospital on day 6. Brain CT and cervical MRI were normal and therefore she was referred to our hospital on day 10. A neurological examination revealed no abnormalities except for EPC in the right hand that was continuous with a semi-rhythmic quality (frequency of 10–15 times/min) and was sometimes aggravated by voluntary movements.

A laboratory evaluation showed normal blood cell counts, electrolyte levels, sedimentation rates, and urinalysis. Anti-nuclear, anti-dsDNA, and anti-cardiolipin antibodies were all negative. Electrocardiography, ultrasound cardiography, and chest radiographs were unremarkable. Electroencephalogram demonstrated slow sporadic high-amplitude waves in the frontoparietal regions. Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) analysis revealed a normal white blood cell count and protein level. Oligoclonal bands were negative and the myelin basic protein level was within the normal range.

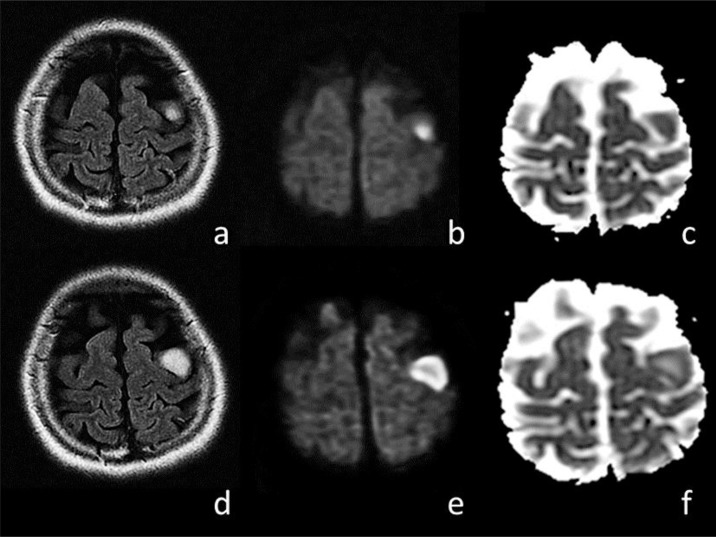

An MRI of the brain revealed a lesion in the left precentral gyrus on day 10 (fig. 1a–c). The lesion exhibited hyperintensities on diffusion-weighted images (DWI) and fluid-attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR) images, and isointensities on apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC) mapping. On day 12, a follow-up brain MRI scan revealed a slight enlargement of the lesion without contrast enhancement. The third MRI scan revealed a rapid enlargement of the lesion on day 22 (fig. 1d–f). The central part of the lesion showed hypointensities on T1-weighted images, hyperintensities on T2-weighted images, iso- to slight hyperintensities on DWI, and increased ADC values. The outer layer of the lesion showed hyperintensities on DWI and relatively restricted ADC values. Although a contrast enhancement MRI study was not performed, the lesion showed no enhancement on a brain CT scan conducted the same day. A thyroid ultrasound showed an enlarged hypoechogenic gland, and a thyroid status assessment showed euthyroid with high titers of anti-thyroglobulin antibodies and anti-thyroid peroxidase antibodies in the serum (342 and 100 IU/ml, respectively), which led to a diagnosis of Hashimoto's disease. A test for CSF anti-α-enolase antibody and serum anti-N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor antibody was negative. We ruled out multiple sclerosis based on a lack of dissemination in time or space, or anti-N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor encephalitis. The possibility of a clinically isolated syndrome, a first attack of multiple sclerosis, cannot be completely denied, but it was unlikely because of the patient's brain lesion involving the cortex, and negative oligoclonal bands or CSF myelin basic protein. Therefore, she was diagnosed with HE.

Fig. 1.

Brain MRIs of a patient with HE presenting with a unilateral frontal nodular lesion. The initial brain MRI on day 10 revealed a nodular lesion in the left precentral gyrus on FLAIR images (a), DWI (b), and an ADC map (c). MRIs conducted on day 22 showed an enlargement of the lesion on FLAIR images (d), hyperintensities in the central part of the lesion on DWI (e), and an increased value on an ADC map (f). A FLAIR MRI sequence revealed a remarkable reduction in the size of the lesion following steroid treatment as compared with that before treatment (not shown).

The EPC gradually spread to the right arm and the frequency increased to 1 cycle/second. Phenobarbital, phenytoin, lamotrigine, and levetiracetam were ineffective. Intravenous methylprednisolone therapy (1 g/day for 3 consecutive days) was initiated on day 23, followed by oral prednisolone (60 mg/day). The EPC completely ceased on day 37. On day 44, a brain MRI showed that the lesion had diminished. The titers of anti-thyroglobulin antibodies and anti-thyroid peroxidase antibodies were decreased on day 54 (101 and 58 IU/ml, respectively).

Discussion

Corticosteroid therapy has not proved to be effective in EPC except in some rare cases [1]. Recently, a first case of autoimmune thyroid encephalopathy presenting as EPC has been reported [2]. This case shares features similar to our case: (1) steroid-responsive EPC; (2) the presence of serum thyroid antibodies, and (3) no cognitive impairment. However, both cases are untypical for HE because they do not show cognitive impairment [3, 4]. Although there are no standard criteria for the diagnosis of HE, the largest clinical study [3] on this subject proposed (1) encephalopathy manifested by cognitive impairment as a criterion and one or more of the following items: neuropsychiatric features (e.g. hallucinations, delusions or paranoia), myoclonus, generalized tonic-clonic or partial seizures, or focal neurologic deficits; (2) the presence of serum thyroid antibodies (thyroid peroxidase antibodies or mycrosomal antibodies); (3) euthyroid status or mild hypothyroidism that would not account for encephalopathy; (4) no evidence in blood, urine or CSF analyses of an infectious, toxic, metabolic or neoplastic process; (5) no serologic evidence of a neuronal voltage-gated calcium or potassium channel; (6) no findings on neuroimaging studies indicating vascular or neoplastic lesions, and (7) complete return to the patient's neurologic baseline status following corticosteroid treatment [3]. Although cognitive impairment was not apparent, our patient's condition fulfilled the rest of the criteria.

In our case, a brain MRI revealed a nodular lesion in the left precentral gyrus. An initial brain MRI indicated demyelination. In the third MRI, the central part of the lesion suggested that active degeneration had occurred, which may be similar to the T1 black holes seen in multiple sclerosis. The outer layer of the lesion suggested ischemia that was likely caused by vasculitis or inflammatory cell infiltrations. If inflammation did occur in our patient, it was around the venule rather than the small arteries because the lesion was near the cerebral cortex and next to the demyelinating lesion without involvement of the meninges. These findings suggest the presence of primary demyelination, with ischemia possibly due to vasculitis around the demyelinating lesion.

In this report, we describe a patient with anti-thyroid antibodies who presented as EPC because of the presence of a unilateral frontal nodular lesion. A steroid-responsive group may exist in EPC, which may be caused by the spectrum of HE. We recommend anti-thyroid antibody screening for EPC because HE responds well to steroid.

Disclosure Statement

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Acknowledgments

We thank Keiko Tanaka (Department of Neurology, Department of Life Science, Medical Research Institute Kanazawa Medical University) for the analysis of anti-N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor antibody and Makoto Yoneda (Second Department of Internal Medicine [Neurology], Faculty of Medical Sciences, University of Fukui) for the analysis of anti-α-enolase antibody.

References

- 1.Biraben A, Chauvel P. Epilepsia partialis continua. In: Engel J Jr, Pedley TA, editors. Epilepsy: A Comprehensive Textbook. Philadelphia: Lippincott-Raven; 1998. pp. 2447–2453. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mahad DJ, Staugaitis S, Ruggieri P, Parisi J, Kleinschmidt-Demasters BK, Lassmann H, Ransohoff RM. Steroid-responsive encephalopathy associated with autoimmune thyroiditis and primary CNS demyelination. J Neurol Sci. 2005;228:3–5. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2004.08.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Castillo P, Woodruff B, Caselli R, Vernino S, Lucchinetti C, Swanson J, Noseworthy J, Aksamit A, Carter J, Sirven J, Hunder G, Fatourechi V, Mokri B, Drubach D, Pittock S, Lennon V, Boeve B. Steroid-responsive encephalopathy associated with autoimmune thyroiditis. Arch Neurol. 2006;63:197–202. doi: 10.1001/archneur.63.2.197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chong JY, Rowland LP, Utiger RD. Hashimoto encephalopathy: syndrome or myth? Arch Neurol. 2003;60:164–171. doi: 10.1001/archneur.60.2.164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mijajlovic M, Mirkovic M, Dackovic J, Zidverc-Trajkovic J, Sternic N. Clinical manifestations, diagnostic criteria and therapy of Hashimoto's encephalopathy: report of two cases. J Neurol Sci. 2010;288:194–196. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2009.09.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Aydin-Özemir Z, Tüzün E, Baykan B, Akman-Demir G, Ozbey N, Gürses C, Christadoss P, Gökyigit A. Autoimmune thyroid encephalopathy presenting with epilepsia partialis continua. Clin EEG Neurosci. 2006;37:204–209. doi: 10.1177/155005940603700308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]