Abstract

Objectives

Galantamine is an acetylcholinesterase inhibitor and an allosteric modulator of the α4β2 and α7 nicotinic receptors. There are several case reports describing the potential benefits of galantamine for negative symptoms associated with schizophrenia. This secondary analysis describes the effects of galantamine on psychopathology in people with schizophrenia.

Methods

Subjects with clinically stable chronic schizophrenia were randomized to adjunctive galantamine (24 mg/d) or placebo in a 12-week double-blind trial. Symptomatology was assessed with the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS) and the Clinical Global Impression Scale. The Scale for the Assessment of Negative Symptoms (SANS) was used to measure negative symptoms.

Results

Eighty-six patients with Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition diagnosis of schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder taking a stable dose of antipsychotic medications were randomized to adjunctive treatment with study drug (galantamine, n = 42; placebo, n = 44); 73 subjects completed the study (galantamine, n = 35; placebo, n = 38). No significant differences were found on BPRS total score (P = 0.585) or BPRS subfactor scores. Scale for the Assessment of Negative Symptoms total scores also did not decrease significantly (P = 0.106) in either group; however, galantamine treatment was associated with a greater benefit in the SANS subfactor, alogia (P = 0.007).

Conclusions

The lack of robust significant effects of galantamine on negative, and other symptom domains, may be due to the relatively low baseline level of these symptoms in the tested population. Galantamine may have some benefit on certain negative symptoms, particularly alogia. Studies specifically designed to address the issue of the efficacy of galantamine for negative symptoms are needed to confirm this observation.

Keywords: schizophrenia, galantamine, randomized controlled trials, nicotine

Antipsychotic medications are the mainstay of the pharmacological treatment of people with schizophrenia. Current medications all act at the dopamine D2 receptors and are mainly effective in alleviating the positive psychotic symptoms of schizophrenia. They do not effectively ameliorate other dimensions of the illness such as impairments in cognition or negative symptoms.1,2 Furthermore, a substantial group of people with schizophrenia do not respond at all to antipsychotic therapy or have only a partial and insufficient response.3 Adjunctive treatment strategies using agents that do not directly target the dopamine system may offer useful synergy in drug action and improve response.

The nicotinic cholinergic system is of interest in this population. A substantially greater proportion of people with schizophrenia smoke cigarettes compared with normal controls or people with other mental disorders.4 This phenomenon has led to investigations of the nicotinic receptor as a possible target for the treatment of symptoms associated with schizophrenia. The 2 most abundant nicotinic receptors in the central nervous system are the α4β2 and the α7 nicotinic receptors.5 Genetic studies have shown that polymorphisms of the α7 nicotinic receptor gene (CHRNA7) are related to the vulnerability of developing schizophrenia.6,7 Postmortem studies have also found that people with schizophrenia have lower concentrations of both nicotinic receptors in several brain regions,8–10 lending support to the hypothesis that a dysregulation of the nicotinic system may contribute to the symptomatology of schizophrenia.

Acute nicotine administration has been shown to improve some impairments in schizophrenia, including sensory gating,11,12 smooth eye pursuit,13,14 and neuropsychological performance in specific domians.15–17 However, there is little evidence to suggest that nicotine robustly improves psychopathology18–20; only 1 study has found cigarette smoking to improve negative symptoms.16 Nicotine has a very high affinity for the α4β2 nicotinic receptor.21 However, chronic nicotine induces tachyphylaxis22 in humans and has many serious associated toxicities. Therefore, it is not an ideal agent to use for long-term enhancement of nicotinic receptor function and may not represent the optimal method of assessing nicotinic enhancement for the treatment of psychopathology in schizophrenia.

Galantamine is an acetylcholinesterase inhibitor (AChEI) and an allosteric modulator of the α4β2 and α7 nicotinic receptors.23–25 Several case reports found galantamine beneficial for improving symptoms in treatment refractory subjects with schizophrenia26,27 and also those with prominent negative symptoms.28,29 Another small open-label study reported improvements in the Positive and Negative Symptom Scale (PANSS) total and positive symptom scores with galantamine treatment.30 Recently, however, 3 randomized placebo-controlled studies found galantamine did not have a significant effect on the total psychopathology or negative symptoms in people with schizophrenia.31–33 However, the largest of these double-blind trials recruited only 38 subjects31 and was in a population that have tardive dyskinesia.

In this article, we report a secondary analysis on the effects of adjunctive galantamine on psychopathology in a large double-blind trial of chronically ill subjects with schizophrenia. Because cigarette smoking may be a complicating factor in clinical trials assessing medications that act at the nicotinic receptor, we also investigated the effects of cigarette smoking status on galanta-mine effects. Postmortem results have found smoking increases the quantity of high-affinity nicotinic receptors in the cortex of people with schizophrenia.10 The up-regulation of receptors from smoking enhances the number of receptors but may also cause a desensitization of these receptors.10,34 Smoking may enhance galantamine treatment of negative symptoms because of the fact galantamine allosterically modulates nicotinic receptors, thereby increasing the affinity of the receptor for acetylcholine, unlike other AChEIs (donepezil and rivastigmine) which only augment nicotinic receptor firing through inhibition of acetylcholine metabolism.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Inclusion/Exclusion Criteria

Subjects included were inpatients or outpatients between the ages of 18 and 60 years with a Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition (DSM-IV) diagnosis of schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder as assessed by the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV.35 The primary outcome measure in this clinical trial was cognition; therefore, each subject was required to have at least minimal impairment in cognition as defined by a Repeatable Battery of Assessment of Neuropsychological Status36 total score of 90 or less. Neurocognitive results are presented elsewhere.37 A minimum or maximum total score for the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS)38 or Scale for the Assessment of Negative Symptoms (SANS)39 was not required; however, all subjects were required to be in a chronic-stable phase of illness, as assessed by their primary physician. Subjects were required to be treated with a second-generation anti-psychotic, other than clozapine, or a low-dose first-generation antipsychotic without concomitant anticholinergic treatment and have a Simpson-Angus Extrapyramidal Symptom40 total score of 4 or less. Excluded subjects were those with an organic brain disease (eg, seizure disorder, stroke), mental retardation, a history of second- or third-degree atrioventricular block, and a chronic unstable medical condition or those who are pregnant. Subjects should not have a DSM-IV diagnosis of alcohol or substance abuse in the last month or a DSM-IV diagnosis of alcohol or substance dependence in the last 6 months. Also, subjects currently treated with ACHEIs were excluded.

Assessments

Clinical assessments included the BPRS (18 items; 1- to 7-point scale), SANS (22 items; 1- to 5-point scale), and the Clinical Global Impression Scale (CGI). All 3 assessments were performed biweekly. Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale subfactors included positive symptoms (conceptual disorganization, suspiciousness, hallucinations, and unusual thought content) and anxiety/depression (anxiety, depression, guilt, and somatic concern).41 A modified SANS total score was used which included all items except inappropriate affect, poverty of content of speech, social inattentiveness, inattentiveness during mental status testing, and all global items.42 All raters were trained, and intraclass correlation coefficients for the 3 clinical assessments ranged from 0.76 to 0.9.

Study Methods

Subjects were randomly assigned to adjunctive galanta-mine or placebo for 12 weeks in this double-blind, parallel-group trial. Before randomization, subjects were assessed for stability of symptoms in a 2-week evaluation phase. The University of Maryland and the State of Maryland Department of Health and Mental Hygiene institutional review boards approved the study. Written informed consent was obtained from all subjects after study procedures and risks had been fully explained and before participation in the study. Subject ability to provide valid informed consent was documented using study-specific procedures.43

Dosing and Adherence

Subjects randomized to galantamine were started on 8 mg/d, the dose was increased by 8-mg/d increments every 4 weeks. If subjects could not tolerate the increase in dose, they were allowed to continue on the last tolerated dose. Galantamine and matching placebo were given twice daily. Adherence was measured by weekly pill counts and medication review. An adherence plan was also put into place for all outpatient subjects; this consisted of medication checks by family and/or mental health care providers who had extensive contact with subjects. Subjects were considered adherent to study medication if they had received 75% of their medication.

Statistical Analysis

Mixed-model analysis of covariance was used to examine changes in BPRS and SANS total scores and subscales. We also examined the interaction of smoking status by medication treatment on the effects of positive and negative symptoms. Subjects were defined as smokers if they had an expired CO of 8 ppm or greater at baseline, or a chart record of current smoking in the absence of measurements. Analysis for smokers versus nonsmokers was conducted by adding terms for smoking, smoking × treatment, smoking × time, and smoking × treatment × time to the mixed models for each outcome measure.

RESULTS

Subjects

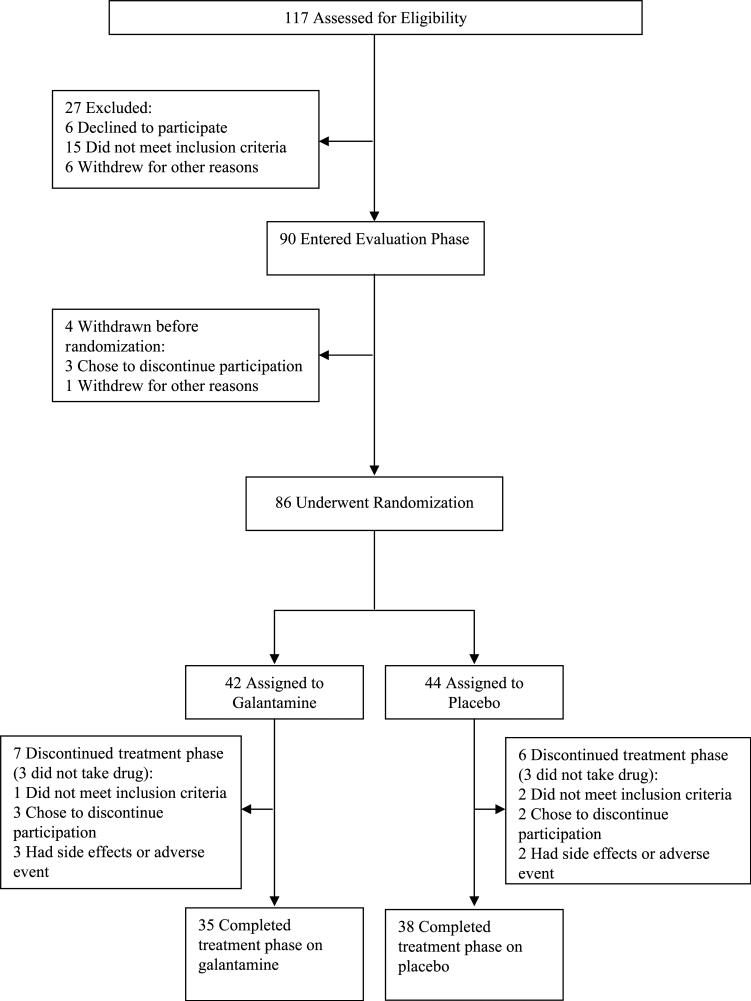

The progression of subjects from recruitment through the end of study is shown in Figure 1. In the galantamine arm, 32 subjects were outpatients and 10 were inpatients, whereas the placebo arm had 31 outpatients and 13 inpatients. In both arms, 3 subjects were treated with low doses of conventional antipsychotics. The remaining subjects were treated with second-generation antipsychotics. Seventy-nine subjects received at least 1 postrandomization symptom assessment and are included in the psychopathology analyses. Demographic and clinical characteristics of the subjects who entered the double-blind phase are presented in Table 1. There were no significant differences in demographic, clinical, or baseline symptom characteristics. The effects of galantamine on neurocognition, side effects, and extrapyramidal symptoms are reported elsewhere.

FIGURE 1.

Diagram of subject progression through clinical trial.

TABLE 1.

Baseline Demographic and Clinical Symptom Rating Scores

| Characteristics | Galantamine (n = 42) | Placebo (n = 44) |

|---|---|---|

| Age, mean ± SD, yrs | 49.9 ± 9.2 | 49.5 ± 9.9 |

| Male sex, % | 88.1 | 84.1 |

| White race, % | 33.3 | 40.9 |

| Age at onset, mean ± SD, yrs | 24.4 ± 7.8 | 25.9 ± 7.2 |

| Clinical assessments, mean ± SD | ||

| BPRS total score | 34.2 ± 9.3 | 34.9 ± 10.6 |

| BPRS positive score | 10.1 ± 5.4 | 10.6 ± 5.0 |

| BPRS anxiety/depression score | 7.7 ± 3.2 | 8.0 ± 3.4 |

| SANS total score | 32.3 ± 12.7 | 29.7 ± 12.3 |

| SANS alogia score | 0.84 ± 0.63 | 0.57 ± 0.64 |

| SANS anhedonia score | 2.45 ± 1.07 | 2.33 ± 1.16 |

| SANS avolition score | 2.27 ± 0.93 | 2.44 ± 1.13 |

| SANS blunted affect score | 1.50 ± 0.92 | 1.21 ± 0.81 |

| CGI | 4.3 ± 0.7 | 4.3 ± 0.8 |

Psychopathology

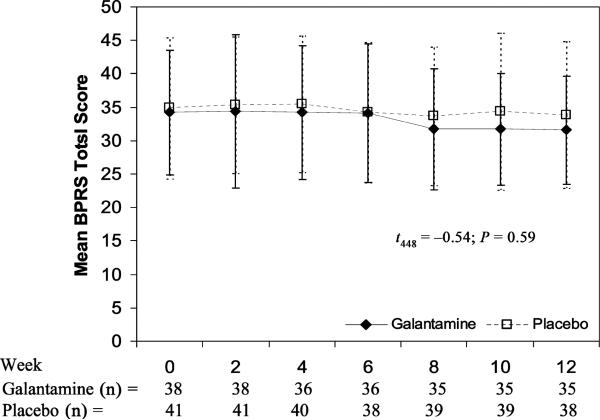

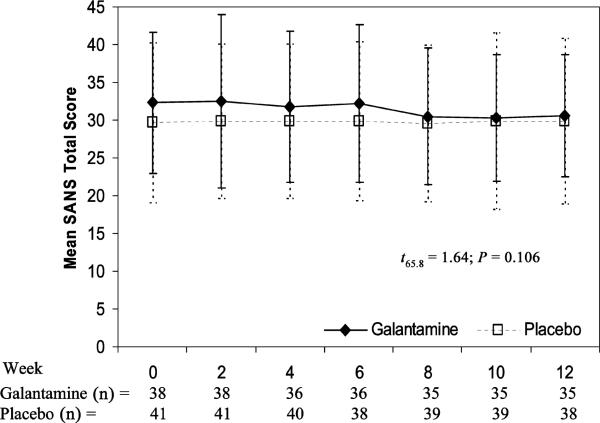

No significant differences were observed between the galantamine and placebo treatment arms on BPRS total score (mean ± SE) with galantamine showing an estimated change over 12 weeks of j –2.1 ± 1.1 versus placebo –0.7 ± 1.35 (t448 = –0.54; P = 0.59) (Fig. 2). Similarly, the SANS total score was not significantly different between galantamine (–1.9 ± 0.83) and placebo (0.04 ± 0.83) (t65.8 = 1.64; P = 0.106) (Fig. 3).

FIGURE 2.

Change in BPRS total score × treatment group.

FIGURE 3.

Change in SANS total scores × treatment group.

The treatment arms also did not differ in estimated change scores for the BPRS subfactor scores of positive symptoms (galantamine, –0.8 ± 0.5, vs placebo, –0.5 ± 0.4) (t448 = –0.55; P = 0.58) or anxiety/depression (galantamine, –0.1 ± 0.4, vs placebo, –0.4 ± 0.3) (t448 = 0.65; P = 0.51). An analysis of the SANS subfactor scores found that alogia was significantly improved in the galantamine treatment arm (–0.21 ± 0.05) compared with placebo (–0.02 ± 0.08) (t71.2= 2.77; P = 0.007). There was also a trend noted for improvements with galantamine in the blunted affect subfactor score (–0.21 ± 0.08) versus placebo (–0.02 ± 0.08) (t71.3= j1.77; P = 0.081). No treatment differences for anhedonia (galantamine, –0.03 ± 0.08, vs placebo, 0.08 ± 0.08) (t69.3= 0.94; P = 0.35) or avolition (galantamine, –0.02 ± 0.09, vs placebo, –0.02 ± 0.09) (t62.7 = 0.06; P = 0.95) subfactors were observed.

There was no difference in the change of CGI severity scores (F1,78 = 0.00; P = 0.96); neither arm showed significant changes during the study (galantamine [mean ± SD]: baseline, 4.3 ± 0.7; end point, 4.2 ± 0.8; and placebo [mean ± SD]: baseline, 4.3 ± 0.8; end point, 4.2 ± 0.7).

Effects of Smoking on Treatment of Psychopathology

The percentage of subjects classified as smokers was similar between the 2 groups. The galantamine treatment arm had 17 (45%) of the 38 subjects meet criteria for smoking, compared with 24 (58%) of the 41 subjects in the placebo arm. The exploratory analysis did not find a significant interaction of smoking status with treatment group on the BPRS and SANS subfactor scores (Table 2). The one exception was with the anxiety/depression subfactor of the BPRS scale in which there was a trend toward a treatment × smoking interaction (P = 0.097).

TABLE 2 Change in Psychopathology Among Subjects Based on Smoking Status and Medication

| Smokers |

Nonsmokers |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Galantamine (n = 17) |

Placebo (n = 24) |

Galantamine (n = 21) |

Placebo (n = 17) |

Smoking × Treatment Interaction* |

|||

| Change in Slope† | Change in Slope† | Change in Slope† | Change in Slope† | t | df | P | |

| BPRS | |||||||

| Total score | –1.3 (1.5) | –1.4 (1.1) | – 2.8 (1.6) | –1.0 (1.3) | 0.68 | 428 | 0.497 |

| Positive symptoms subfactor | –1.0 (0.8) | –0.6 (0.5) | – 0.8 (0.8) | –0.3 (0.6) | 0.08 | 428 | 0.939 |

| Anxiety/depression subfactor | 0.5 (0.6) | –0.6 (0.4) | –0.6 (0.4) | –0.1 (0.4) | 1.67 | 428 | 0.097 |

| SANS | |||||||

| Total score | –2.18 (1.25) | 1.26 (1.05) | –1.79 (1.09) | –1.72 (1.18) | –1.47 | 63.6 | 0.147 |

| Alogia subfactor | –0.17 (0.07) | 0.00 (0.06) | –0.24 (0.06) | –0.07 (0.07) | –0.04 | 68.9 | 0.965 |

| Anhedonia subfactor | –0.10 (0.13) | 0.09 (0.11) | 0.03 (0.11) | 0.06 (0.12) | –0.65 | 67.3 | 0.518 |

| Avolition subfactor | –0.06 (0.13) | 0.03 (0.11) | 0.01 (0.11) | –0.07 (0.12) | –0.69 | 60.6 | 0.494 |

| Blunted affect subfactor | –0.25 (0.12) | 0.11 (0.10) | –0.19 (0.10) | –0.19 (0.11) | –1.64 | 68.9 | 0.105 |

Statistical tests from mixed model for unbalanced repeated measures with linear time trends (slopes).

Estimated change over 12 weeks (SE).

CONCLUSIONS

In this study, subjects with chronic schizophrenia and stable positive and negative symptoms did not show improvement in global measures of these symptoms with adjunctive galantamine treatment compared with placebo. Previous reports have found improvements in negative symptoms with galantamine,28,29 although larger controlled studies have not replicated these observations.31–33 It should be noted, however, that subjects in this study were recruited based on cognitive ability and stability of psychiatric symptoms. Thus, subjects enrolled in the study did not have high levels of negative symptoms or enduring symptomatology, consequently, this study may not have adequately detected galantamine's effects on persistent negative symptoms. Nevertheless, despite low to moderate levels of negative symptoms at baseline, galantamine-treated subjects did improve in alogia, a SANS subfactor. This finding is similar to that described in a previous case series by Ochoa and Clark.29 In an open-label trial, these authors reported that in a subject population with high levels of negative symptoms, galantamine treatment (N = 13) showed the most robust symptom improvements in the alogia subfactor of the SANS among all the negative symptom domains measured.

Alogia, or poverty of speech, is considered a core aspect of the negative symptom construct.44 It has been suggested that alogia is related to the cognitive impairments present in schizophrenia.45 In fact, it has been suggested that semantic memory disorganization may contribute to the symptom of alogia in schizophrenia.46 Therefore, it is possible that the observed improvements in alogia are related to the improvements of processing speed and verbal memory that were also observed in this group.

Galantamine may improve only a subset of negative symptoms. It is widely accepted that pharmacological agents influence specific domains of cognition; recently, it has been suggested that the treatment of negative symptoms should be thought of in the same way: not globally, but only in specific symptom domains.44 In this study, alogia was improved, and blunted affect tended toward improvement with galantamine treatment. Blunted affect and alogia are highly correlated subfactors on the SANS.47 As high doses of nicotine have also been shown to improve alogia in subjects with schizophrenia,16 there is now support that the symptoms of alogia may be mediated, in part, through alterations in the nicotinic system.

In this study, cigarette smoking did not modify the effects of galantamine on any of the psychiatric symptoms. Randomization for treatment was not based on smoking status or amount of cigarettes smoked per day. Therefore, a treatment interaction between smoking and galantamine cannot be rejected based on this trial. Other studies are needed to examine the effects of medications that allosterically modulate nicotinic receptors in subjects who smoke cigarettes versus nonsmokers.

The results of this study are limited by the fact that this was a secondary analysis with chronic stable subjects who did not have high levels of symptomatology, specifically in negative symptoms where a hypothesized effect may occur. In particular, symptoms of alogia, where a possible effect was noted, were both infrequent and moderate in severity.

Recently, another nicotinic medication, varenicline, has been reported to exacerbate psychiatric symptoms in 2 case reports.48,49 Varenicline is a partial agonist at the α4β2 nicotinic receptor and, at doses higher than those typically used for smoking cessation, a full agonist at the α7 nicotinic receptor.50 Cholinergic neurons mediate norepinephrine and dopamine release, which in turn can precipitate psychiatric symptoms. However, similar to the findings of others,29,30,32,33 galantamine treatment was safe in our study: illness exacerbation did not occur during treatment in any subject.

In conclusion, this study did not confirm earlier reports that adjunct galantamine treatment improves global negative symptoms, but suggestive improvements were noted in alogia. Further study is needed inthose with alogia to determine if galantamine is effective for this primary and enduring negative symptom in people with schizophrenia.

Acknowledgments

The study was primarily funded by 2 Stanley Medical Research Institute awards (R.R.C. and R.W.B.) and also in part by the VA Capitol Network (VISN 5) Mental Illness Research, Education, and Clinical Center (MIRECC); and P30 068580 (R.W.B.). Double-blind medications were provided by Ortho-McNeil Neurologics, Inc.

Robert R. Conley is an employee of Eli Lilly. Deanna L. Kelly is member of the advisory board of Solvay and Bristol-Myers Squibb and received honoraria from Astra-Zeneca and grant support from Abbott and Astra-Zeneca. Patricia Ball received grant support from Eli Lilly. Robert W. Buchanan is a DSMB member of Pfizer. Dwight Dickinson is a DSMB member of Wyeth; consultant of Memory, Organon, and Roche; and member of the advisory board of Astra-Zeneca, Glaxo-Smith-Kline, Pfizer, Sanofi-Aventis, and Solvay.

Footnotes

Douglas L. Boggs, Robert P. McMahon and Stephanie Feldman have no competing interests or financial support to disclose.

REFERENCES

- 1.Murphy BP, Chung YC, Park TW, et al. Pharmacological treatment of primary negative symptoms in schizophrenia: a systematic review. Schizophr Res. 2006;88(1Y3):5–25. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2006.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Keefe RS, Silva SG, Perkins DO, et al. The effects of atypical antipsychotic drugs on neurocognitive impairment in schizophrenia: a review and meta-analysis. Schizophr Bull. 1999;25(2):201–222. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a033374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Conley RR, Buchanan RW. Evaluation of treatment-resistant schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 1997;23(4):663–674. doi: 10.1093/schbul/23.4.663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.de Leon J, Diaz FJ. A meta-analysis of worldwide studies demonstrates an association between schizophrenia and tobacco smoking behaviors. Schizophr Res. 2005;76(2–3):135–157. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2005.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hellstrom-Lindahl E, Mousavi M, Zhang X, et al. Regional distribution of nicotinic receptor subunit mRNAs in human brain: comparison between Alzheimer and normal brain. Brain Res Mol Brain Res. 1999;66(1–2):94–103. doi: 10.1016/s0169-328x(99)00030-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stassen HH, Bridler R, Hagele S, et al. Schizophrenia and smoking: evidence for a common neurobiological basis? Am J Med Genet. 2000;96(2):173–177. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Leonard S, Gault J, Hopkins J, et al. Association of promoter variants in the alpha7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor subunit gene with an inhibitory deficit found in schizophrenia. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2002;59(12):1085–1096. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.59.12.1085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Freedman R, Hall M, Adler LE, et al. Evidence in postmortem brain tissue for decreased numbers of hippocampal nicotinic receptors in schizophrenia. Biol Psychiatry. 1995;38(1):22–33. doi: 10.1016/0006-3223(94)00252-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Durany N, Zochling R, Boissl KW, et al. Human post-mortem striatal alpha4beta2 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor density in schizophrenia and Parkinson’s syndrome. Neurosci Lett. 2000;287(2):109–112. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(00)01144-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Breese CR, Lee MJ, Adams CE, et al. Abnormal regulation of high affinity nicotinic receptors in subjects with schizophrenia. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2000;23(4):351–364. doi: 10.1016/S0893-133X(00)00121-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Griffith JM, O’Neill JE, Petty F, et al. Nicotinic receptor desensitization and sensory gating deficits in schizophrenia. Biol Psychiatry. 1998;44(2):98–106. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(97)00362-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Adler LE, Hoffer LD, Wiser A, et al. Normalization of auditory physiology by cigarette smoking in schizophrenic patients. Am J Psychiatry. 1993;150(12):1856–1861. doi: 10.1176/ajp.150.12.1856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tanabe J, Tregellas JR, Martin LF, et al. Effects of nicotine on hippocampal and cingulate activity during smooth pursuit eye movement in schizophrenia. Biol Psychiatry. 2006;59(8):754–761. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Olincy A, Johnson LL, Ross RG. Differential effects of cigarette smoking on performance of a smooth pursuit and a saccadic eye movement task in schizophrenia. Psychiatry Res. 2003;117(3):223–236. doi: 10.1016/s0165-1781(03)00022-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Depatie L, O’Driscoll GA, Holahan AL, et al. Nicotine and behavioral markers of risk for schizophrenia: a double-blind, placebo-controlled, cross-over study. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2002;27(6):1056–1070. doi: 10.1016/S0893-133X(02)00372-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Smith RC, Singh A, Infante M, et al. Effects of cigarette smoking and nicotine nasal spray on psychiatric symptoms and cognition in schizophrenia. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2002;27(3):479–497. doi: 10.1016/S0893-133X(02)00324-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Smith RC, Warner-Cohen J, Matute M, et al. Effects of nicotine nasal spray on cognitive function in schizophrenia. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2006;31(3):637–643. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dalack GW, Meador-Woodruff JH. Acute feasibility and safety of a smoking reduction strategy for smokers with schizophrenia. Nicotine Tob Res. 1999;1(1):53–57. doi: 10.1080/14622299050011151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yang YK, Nelson L, Kamaraju L, et al. Nicotine decreases bradykinesia-rigidity in haloperidol-treated patients with schizophrenia. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2002;27(4):684–686. doi: 10.1016/S0893-133X(02)00325-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Evins AE, Deckersbach T, Cather C, et al. Independent effects of tobacco abstinence and bupropion on cognitive function in schizophrenia. J Clin Psychiatry. 2005;66(9):1184–1190. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v66n0915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Brody AL, Mandelkern MA, London ED, et al. Cigarette smoking saturates brain alpha 4 beta 2 nicotinic acetylcholine receptors. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2006;63(8):907–915. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.63.8.907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Martin LF, Kem WR, Freedman R. Alpha-7 nicotinic receptor agonists: potential new candidates for the treatment of schizophrenia. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2004;174(1):54–64. doi: 10.1007/s00213-003-1750-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schilstrom B, Ivanov VB, Wiker C, et al. Galantamine enhances dopaminergic neurotransmission in vivo via allosteric potentiation of nicotinic acetylcholine receptors. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2007;32(1):43–53. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1301087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Samochocki M, Hoffle A, Fehrenbacher A, et al. Galantamine is an allosterically potentiating ligand of neuronal nicotinic but not of muscarinic acetylcholine receptors. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2003;305(3):1024–1036. doi: 10.1124/jpet.102.045773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dajas-Bailador FA, Heimala K, Wonnacott S. The allosteric potentiation of nicotinic acetylcholine receptors by galantamine is transduced into cellular responses in neurons: Ca2+ signals and neurotransmitter release. Mol Pharmacol. 2003;64(5):1217–1226. doi: 10.1124/mol.64.5.1217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Allen TB, McEvoy JP. Galantamine for treatment-resistant schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 2002;159(7):1244–1245. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.159.7.1244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rosse RB, Deutsch SI. Adjuvant galantamine administration improves negative symptoms in a patient with treatment-refractory schizophrenia. Clin Neuropharmacol. 2002;25(5):272–275. doi: 10.1097/00002826-200209000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Arnold DS, Rosse RB, Dickinson D, et al. Adjuvant therapeutic effects of galantamine on apathy in a schizophrenia patient. J Clin Psychiatry. 2004;65(12):1723–1274. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v65n1219e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ochoa EL, Clark E. Galantamine may improve attention and speech in schizophrenia. Hum Psychopharmacol. 2006;21(2):127–128. doi: 10.1002/hup.751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Noren U, Bjorner A, Sonesson O, et al. Galantamine added to antipsychotic treatment in chronic schizophrenia: cognitive improvement? Schizophr Res. 2006;85(1–3):302–304. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2006.03.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Caroff SN, Walker P, Campbell C, et al. Treatment of tardive dyskinesia with galantamine: a randomized controlled crossover trial. J Clin Psychiatry. 2007;68(3):410–415. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v68n0309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lee SW, Lee JG, Lee BJ, et al. A 12-week, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of galantamine adjunctive treatment to conventional antipsychotics for the cognitive impairments in chronic schizophrenia. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2007;22(2):63–68. doi: 10.1097/YIC.0b013e3280117feb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schubert MH, Young KA, Hicks PB. Galantamine improves cognition in schizophrenic patients stabilized on risperidone. Biol Psychiatry. 2006;60(6):530–533. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kumari V, Aasen I, ffytche D, et al. Neural correlates of adjunctive rivastigmine treatment to antipsychotics in schizophrenia: a randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind fMRI study. Neuroimage. 2006;29(2):545–556. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2005.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, et al. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IVAxis Disorders (SCID-IV) Biometrics Research Department, New York State Psychiatric Institute; New York, NY: 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gold JM, Queern C, Iannone VN, et al. Repeatable battery for the assessment of neuropsychological status as a screening test in schizophrenia, I: sensitivity, reliability, and validity. Am J Psychiatry. 1999;156(12):1944–1950. doi: 10.1176/ajp.156.12.1944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Buchanan RW, Conley RR, Dickinson D, et al. Galantamine for the treatment of cognitive impairments in people with schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 2008;165(1):82–89. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2007.07050724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Overall J, Gorham D. The Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale. Psychol Rep. 1962;10:799–812. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Andreasen NC. Negative symptoms in schizophrenia. Definition and reliability. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1982;39(7):784–788. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1982.04290070020005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Simpson GM, Angus JW. A rating scale for extrapyramidal side effects. Acta Psychiatr Scand Suppl. 1970;212:11–19. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1970.tb02066.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Guy W. ECDEU Assessment Manual for Psychopharmacology, Revised (DHEW Publication No. ADM 76-338) US Department of Health and Human Services; Rockville, MD: 1976. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Buchanan RW, Javitt DC, Marder SR, et al. The Cognitive and Negative Symptoms in Schizophrenia Trial (CONSIST): the efficacy of glutamatergic agents for negative symptoms and cognitive impairments. Am J Psychiatry. 2007;164(10):1593–1602. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2007.06081358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.DeRenzo EG, Conley RR, Love R. Assessment of capacity to give consent to research participation: state-of-the-art and beyond. J Health Care Law Policy. 1998;1(1):66–87. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kirkpatrick B, Fenton WS, Carpenter WT, Jr, et al. The NIMH-MATRICS consensus statement on negative symptoms. Schizophr Bull. 2006;32(2):214–219. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbj053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bilder RM, Goldman RS, Robinson D, et al. Neuropsychology of first-episode schizophrenia: initial characterization and clinical correlates. Am J Psychiatry. 2000;157(4):549–559. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.157.4.549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sumiyoshi C, Sumiyoshi T, Nohara S, et al. Disorganization of semantic memory underlies alogia in schizophrenia: an analysis of verbal fluency performance in Japanese subjects. Schizophr Res. 2005;74(1):91–100. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2004.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Blanchard JJ, Cohen AS. The structure of negative symptoms within schizophrenia: implications for assessment. Schizophr Bull. 2006;32(2):238–245. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbj013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Freedman R. Exacerbation of schizophrenia by varenicline. Am J Psychiatry. 2007;164(8):1269. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2007.07020326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kohen I, Kremen N. Varenicline-induced manic episode in a patient with bipolar disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2007;164(8):1269–1270. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2007.07010173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Mihalak KB, Carroll FI, Luetje CW. Varenicline is a partial agonist at alpha4beta2 and a full agonist at alpha7 neuronal nicotinic receptors. Mol Pharmacol. 2006;70(3):801–815. doi: 10.1124/mol.106.025130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]