Abstract

Background

Olaparib has single-agent activity against breast/ovarian cancer (BrCa/OvCa) in germline BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutation carriers (gBRCAm). We hypothesized addition of olaparib to carboplatin can be administered safely and yield preliminary clinical activity.

Methods

Eligible patients had measurable or evaluable disease, gBRCAm, and good end-organ function. A 3 + 3 dose escalation tested daily oral capsule olaparib (100 or 200mg every 12 hours; dose level1 or 2) with carboplatin area under the curve (AUC) on day 8 (AUC3 day 8), then every 21 days. For dose levels 3 to 6, patients were given olaparib days 1 to 7 at 200 and 400 mg every 12 hours, with carboplatin AUC3 to 5 on day 1 or 2 every 21 days; a maximum of eight combination cycles were permitted, after which daily maintenance of olaparib 400mg every12 hours continued until progression. Dose-limiting toxicity was defined in the first two cycles. Peripheral blood mononuclear cells were collected for polymorphism analysis and polyADP-ribose incorporation. Paired tumor biopsies (before/after cycle 1) were obtained for biomarker proteomics and apoptosis endpoints.

Results

Forty-five women (37 OvCa/8 BrCa) were treated. Dose-limiting toxicity was not reached on the intermittent schedule. Expansion proceeded with olaparib 400mg every 12 hours on days 1 to 7/carboplatin AUC5. Grade 3/4 adverse events included neutropenia (42.2%), thrombocytopenia (20.0%), and anemia (15.6%). Responses included 1 complete response (1 BrCa; 23 months) and 21 partial responses (50.0%; 15 OvCa; 6 BrCa; median = 16 [4 to >45] in OvCa and 10 [6 to >40] months in BrCa). Proteomic analysis suggests high pretreatment pS209-eIF4E and FOXO3a correlated with duration of response (two-sided P < .001; Pearson’s R 2 = 0.94).

Conclusions

Olaparib capsules 400mg every 12 hours on days 1 to 7/carboplatin AUC5 is safe and has activity in gBRCAm BrCa/OvCa patients. Exploratory translational studies indicate pretreatment tissue FOXO3a expression may be predictive for response to therapy, requiring prospective validation.

DNA repair is essential for cells to survive damage caused by ambient environmental toxins, chemotherapy, and other treatments (1,2). Homologous recombination (HR) is a predominantly error-free mechanism to repair double-strand DNA break (DSB). Key components of DSB repair are the tumor-suppressor proteins BRCA1 and BRCA2. Dysfunctional HR leads to activation of the base excision repair pathway, a single-strand DNA break repair pathway requiring polyADPribose polymerase (PARP) (3). Increased PARP-1 expression and/or activity in tumor cells has been demonstrated in many tumor types (4–6). Active base excision repair stalls replication to allow single-strand DNA break repair. The absence of single-strand DNA break repair causes DNA helix strain at transcription forks and leads to DSBs requiring HR and, therefore, BRCA1 and BRCA2 (7).

Development of DSBs in the absence of HR activates nonhomologous end joining, a poor-fidelity DSB repair pathway. PARP inhibition has been shown to induce phosphorylation of DNA-dependent protein kinase and permit error-prone nonhomologous end joining in HR-deficient cells (8). Thus, HR dysfunction sensitizes cells to PARP inhibition, leading to further chromosomal instability, cell cycle arrest, and apoptosis (9). Germline HR deficiency improves the therapeutic window for PARP inhibition (10–12).

The interrelationship between DNA repair pathways led to the development of PARP inhibitors (PARPis) as therapeutic agents. Olaparib, an oral PARP1/2 inhibitor, is tolerated at single-agent continuous doses up to 400mg twice daily (capsules) (13). It has been active as monotherapy in tumors with defective HR, specifically germline BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations (gBRCAm). Clinical activity with prolonged disease stabilization and tumor burden reduction has been reported in gBRCAm-associated breast and/or ovarian cancer (gBRCAm BrCa/OvCa) (14–18). Phase II studies have confirmed the activity of olaparib monotherapy with response rates of 41% in gBRCAm patients with advanced BrCa (17) and 31% to 40% in those with OvCa (13,15). The optimal application of PARPis in treatment of gBRCAm BrCa/OvCa has not yet been determined.

gBRCAm carriers with OvCa have increased susceptibility to platinums (19) and often receive multiple lines of platinum-based chemotherapy and can have longer overall survival than nonmutation carriers (20,21). It has been demonstrated preclinically that concomitant use of olaparib increases cytotoxic activity of cisplatin in cisplatin-resistant OvCa cell lines (22), and an intermittent schedule of olaparib with carboplatin yields antitumor activity in a BRCA2-mutated human ovarian cancer xenograft model (23). Thus, we hypothesized addition of olaparib to carboplatin as a stress to the DNA repair machinery would improve clinical benefit of carboplatin and could be safely given to women with gBRCAm-associated cancers. We conducted a phase I/Ib study to evaluate the safety, tolerability, and activity of olaparib administered with carboplatin. Our translational aim was to discover potential predictive biomarkers of response to the carboplatin/PARPi combination.

Methods

Patients

This phase I/Ib study (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT01445418) was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Center for Cancer Research, National Cancer Institute (NCI). Eligibility criteria included gBRCAm BrCa/OvCa or BrCa/OvCa with a BRCAPro score of 30% or higher (24); recurrent or refractory disease or locally advanced unresectable BrCa; measureable (biopsiable for expansion cohort) or evaluable disease; ECOG performance status of 0 to 2; normal end-organ function except grade 1 an emia, neutropenia, leukopenia, and aspartate aminotransferase/alanine aminotransferase (AST/ALT); no tumor-related therapy for 4 weeks and no platinum for at least 6 months; no NCI Common Terminology Criteria (CTCAE v3.0) grade 4 platinum allergic reaction; no prior PARPis; no infection requiring antibiotics within 7 days; and no brain metastases diagnosed or active within the past year. All patients provided written informed consent.

Drug Administration

This open-label, 3 + 3 dose escalation incorporated continuous daily or intermittent olaparib capsules at doses of 100 to 400mg every 12 hours (Table 1; Figure 1) with carboplatin area under the curve (AUC) 3–5 (AUC3–5) once per 21-day cycle. No more than eight combination cycles were given, and all nonprogressing patients received daily maintenance of olaparib 400mg every12 hours until disease progression. Pegfilgrastim was indicated for use in subsequent cycles if the day 1 absolute neutrophil count was 1500 to 1800 per milliliter or if the day 1 absolute neutrophil count was less than 1500 per milliliter, necessitating a treatment delay. Pegfilgrastim was not allowed during the first 2 cycles of the dose-escalation phase because those were the cycles used to determine safety, and once initiated, pegfilgrastim was continued during the combination treatment cycles. It was not allowed during olaparib maintenance therapy. Safety was assessed and adverse events graded every cycle (CTCAE v3.0). Tumor response was assessed by imaging and physical exam every two cycles using RECIST v1.0 (25).

Table 1.

Dose levels and distribution of patients (n = 45)

| Dose level | Schedule and dose | Ovarian cancer, No. | Breast cancer, No. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Olaparib oral, every 12 hours | Carboplatin AUC IV every 3 weeks | |||

| 1 | 100mg, days 1–21 | 3, day 8 | 6 | 1* |

| 2 | 200mg, days 1–21 | 3, day 8 | 4 | 1* |

| 3 | 200mg, days 1–7 | 3, day 1 or 2 | 4 | 1† |

| 4 | 400mg, days 1–7 | 3, day 1 or 2 | 4 | 0 |

| 5 | 400mg, days 1–7 | 4, day 1 or 2 | 2 | 1† |

| 6 | 400mg, days 1–7 | 5, day 1 or 2 | 6 | 0 |

| Expansion cohort | 400mg, days 1–7 | 5, day 1 or 2 | 11 | 4†† |

* Triple negative breast cancer. AUC IV = area under the curve intravenously.

† Estrogen receptor/progesterone receptor–positive breast cancer.

†† Two cases were triple-negative breast cancer and 2 cases were estrogen receptor/progesterone receptor–positive breast cancer.

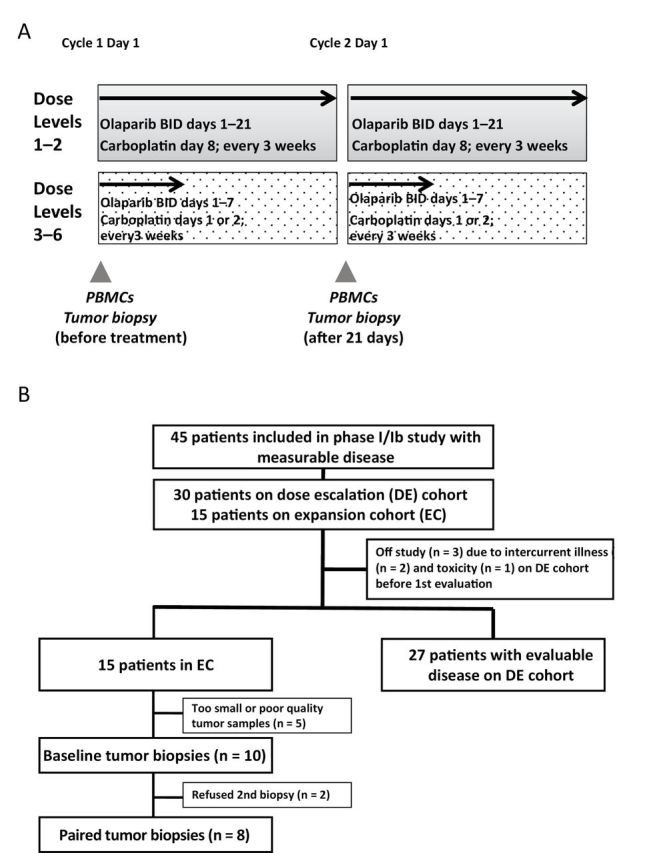

Figure 1.

Study schema (A) and CONSORT diagram (B). This shows the treatment schedule and timing of the blood and research biopsies collection. BID = twice a day, PBMCs = peripheral blood mononuclear cells.

Dose-limiting toxicities were defined as grade 3/4 nonhematologic and grade 4 hematologic adverse events related to study medications occurring during the first two cycles of therapy, with the following exceptions: grade 3 diarrhea, nausea, or vomiting must have been unresponsive to optimal medical management, and asymptomatic grade 3 hypomagnesemia, hyponatremia, hypophosphatemia, and hypocalcemia rapidly reversed with medical management. Grade 3 thrombocytopenia lasting for 7 or more days or requiring transfusion and grade 4 neutropenia for 7 or more days or with fever were dose-limiting. Complete blood counts and serum chemistries were monitored weekly during the dose-limiting toxicity period. Study treatment was discontinued for progression of disease, intercurrent illness, adverse events not recovering to grade 1 or less within 3 weeks, and patient preference.

Translational Studies

Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) were collected at baseline and before cycle 2 (Figure 1A), separated within 4 hours, and stored in aliquots at −80oC until use. PBMC DNA polyADP-ribose (PAR) incorporation was measured using a commercial PAR immunoassay (Trevigen, Gaithersburg, MD) as described (26). PBMC DNA was isolated for polymorphism analysis of PARP1 A762V, XRCC1 R194W, and XRCC1 Q399R using a commercial DNA purification kit (Qiagen, Germantown, MD) as described (27).

Paired research tumor biopsies were collected in expansion cohort patients for reverse-phase protein arrays (RPPAs) and apoptosis assessment. Percutaneous biopsies were obtained by interventional radiologists under computed tomography or ultrasound guidance (28,29). Samples were processed in real time in optimal cutting temperature compound and stored at −80°C as described (29). Optimal quality of tissue was defined as a set of paired sequential biopsies that were suitable as defined by solid tissue areas containing at least 50% tumor cells and less than 25% necrosis (28,30,31). Tissue area was measured as described (29,32); tissue was lysed (33), then RPPAs were executed by the MD Anderson RPPA Core Facility (34). Total protein per spot on the RPPA was measured by colloidal gold stain and used to standardize signals per standard procedures (29,34).

Immunohistochemistry was used to examine expression of FOXO3a in biopsy sections stained using standard procedures (29) (anti-FOXO3a. 1:100 dilution; Cell Signaling, Boston, MA) with detection using SignalStain DAB Substrate Kit. Staining was positive when localized to the nucleus. The number of nuclear stained tumor cells in five high-power fields were summed as described (29).

The DeadEnd colorimetric TUNEL kit (Promega, Madison, WI) was used per manufacturer’s instructions to examine apoptosis (35). Eight paired biopsy samples were available. The apoptotic index was defined as the percentage of TUNEL-positive single cells in five high-power fields.

Statistical Analyses

Protocol-defined expansion occurred for exploratory predictive biomarker analyses. For any given translational endpoint comparison, 10 paired biopsies were needed to provide 80% power to detect a difference between pre- and on-treatment values equal to 1 standard deviation of the difference (α2 = 0.05). The association of proteomic endpoints with response and/or progression-free survival (PFS) was examined using the log-rank test (GraphPad Prism 6, La Jolla, CA). Correlation between polymorphisms in PARP1 and XRCC1 and PFS was tested using the log-rank test, and response was tested using the Fisher exact test. Baseline PAR concentrations were compared with response and PFS using the Fisher exact test. The mean of TUNEL results from baseline and after cycle 1 were compared using a two-tailed paired t test (Prism 6). TUNEL results were correlated with response by Pearson correlation coefficient (JMP 9.0; SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

Normalized, median-centered values for each protein in the RPPA were analyzed for linear correlation to duration of response for each patient using JMP 9.0. One hundred sixty-seven proteins were assessed by RPPA. Analysis of variance was performed, and the false discovery rate was controlled for with an alpha of 0.05 by the method of Hochberg (36) to correct for multiple comparisons. The identified proteins were then screened for a minimal model that would describe duration of response for each patient using the JMP 9.0 Model Screening platform with P values derived from a simulation of 10000 Lenth t ratios. Statistically significant proteins predicted from the model screening platform were analyzed using the JMP 9.0 Model Builder suite to construct a least squares regression model of the linear combination of the statistically significant proteins. Variance inflation factors for multicollinearity were calculated in JMP 9.0. Interslide reproducibility for the RPPA has been examined by multiple groups and found to be high in tumor tissue and cell lines, with mean coefficients of variation across all antibodies of less than 10% (37,38).

A P value of less than .05 was considered statistically significant, and all statistical tests were two-sided.

Results

Patients

Patient accrual is shown in the CONSORT diagram (n = 45) (Figure 1B), and characteristics are presented in Table 2. gBRCAm status was obtained as part of clinical trial enrollment from the patient’s commercially obtained genetic test results in most cases: a deleterious mutation risk outcome was estimated using the BRCAPro model for one patient. BRCA1 mutation was most common (71.1%). Patients had various BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations, with 20 different mutations in 32 BRCA1 mutation carriers, and nine different mutations in 11 BRCA2 mutation carriers. These include seven patients with 5385insC BRCA1 (21.9%) and three patients with 6174delT BRCA2 (27.2%), the most common mutations. All but two OvCa patients had high-grade serous OvCa, and all previously had received carboplatin (median platinum-free interval = 14 months; range = 6–55), with 62% deemed platinum resistant or refractory. One of eight BrCa patients previously had received platinum-based therapy. All patients were heavily pretreated (median = 5 months; range = 2–11). The median treatment-free interval for all patients was 8 months (range = 3–34 months).

Table 2.

Patient characteristics (n = 45)

| Patient characteristics | Number |

|---|---|

| Age, y, median (range) | 52 (35–73) |

| BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutational status | |

| BRCA1 | 32 |

| BRCA2 | 11 |

| Both BRCA1 and 2 | 1 |

| BRCAPro ≥30% | 1 |

| Tumor type | |

| Ovarian cancer* | 37 |

| Platinum sensitive | 14 |

| Platinum resistant | 16 |

| Platinum refractory | 7 |

| Breast cancer | 8 |

| Triple-negative breast cancer | 4 |

| Estrogen receptor/progesterone receptor–positive breast cancer | 4 |

| ECOG performance status | |

| 0 | 1 |

| 1 | 40 |

| 2 | 4 |

| Median number of prior regimens (range) | |

| Prior chemotherapeutic agents | 5 (2–11) |

| Prior biologic agents | 0 (0–4) |

| Prior hormonal agents | 0 (0–4) |

* Thirty-five patients had high-grade serous ovarian cancer, and two had moderately differentiated serous ovarian cancer. Platinum sensitive: recurs 6 or more months after cessation of platinum-based chemotherapy; platinum resistant: progression within 6 months of platinum-based therapy; platinum-refractory: progression on platinum-based therapy.

Dose Optimization

A total of 545 cycles were administered to 45 patients (median = 10 cycles; range = 1 to >45), at six dose levels with twice-daily olaparib doses ranging from 100 to 400mg and carboplatin ranging from AUC 3 to 5. Continuous daily olaparib at 200mg every 12 hours with every-3-week carboplatin AUC3 resulted in dose-limiting toxicity of grade 3 thrombocytopenia lasting greater than 7 days in each of two ovarian cancer patients. This led to a revised schedule of twice-daily olaparib on days 1 to 7 of each 21-day cycle, on which backbone the carboplatin dose escalation proceeded. Maximum tolerated dose was not reached on the intermittent schedule, defining the highest tested dose as the expansion phase dose: olaparib 400mg every 12 hours on days 1 to 7 with carboplatin AUC5.

Adverse Events

Common nonhematologic events were nausea, fatigue, headache, and gastroesophageal reflux (Table 3). These were mainly mild to moderate in severity, self-limiting, and manageable with standard treatments. Hematologic toxicity was the most common adverse event, with anemia in 37 of 45 (82.2%) patients, reaching grade 3 or 4 in seven patients (15.6%). All seven patients received red cell transfusions, and two required carboplatin dose reduction; all completed their planned eight cycles. Neutropenia was seen in 77.8% and was grade 3 in 19 patients (42.2%); no grade 4 or fever during neutropenia occurred. Twenty-two of 45 patients (48.9%) received pegfilgrastim starting as early as cycle 2 (non–dose limiting toxicity cohort) to avoid treatment delays, continuing during combination therapy cycles only. Thrombocytopenia was observed in 29 of 45 patients (64.4%) and was grade 3 or 4 in nine of 45 patients (20.0%). Three of nine patients had carboplatin dose reduction and subsequently discontinued carboplatin early. There was no statistically significant difference in hematologic toxicities as a function of BRCA1 vs BRCA2 mutation, although it was underpowered for this analysis. One patient with grade 4 thrombocytopenia without bleeding required platelet transfusion because of intercurrent illness. Seven patients (15.6%) discontinued carboplatin before the planned eight cycles because of hypersensitivity reaction (n = 4) (39) or myelosuppression (n = 3). One patient, who received four prior platinum-based regimens, had repeated grade 3 thrombocytopenia lasting greater than 7 days on olaparib monotherapy. Bone marrow study revealed no dysplasia or lymphoproliferative disorder. She had an unmaintained partial response of 6 months.

Table 3.

Drug-related adverse events by maximum grade per patient (n = 45)

| Adverse event | Grade 1 | Grade 2 | Grade 3 | Grade 4 | Grade 3/4 total (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hematology* | |||||

| Neutropenia | 1 | 15 | 19 | 0 | 19/45 (42.2) |

| Thrombocytopenia | 13 | 7 | 7 | 2 | 9/45 (20.0) |

| Anemia | 8 | 22 | 6 | 1 | 7/45 (15.6) |

| Gastrointestinal disorders | |||||

| Nausea | 19 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 1/45 (2.2) |

| Vomiting | 3 | 4 | 1 | 0 | 1/45 (2.2) |

| Gastroesophageal reflux disease | 10 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Constipation | 4 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Diarrhea | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Anorexia | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Chemistry | |||||

| Hyponatremia | 13 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 2/45 (4.4) |

| Hypokalemia | 4 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 2/45 (4.4) |

| Hypomagnesaemia | 17 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Increased AST | 10 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Increased ALT | 10 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Increased Cr | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1/45 (2.2) |

| Other | |||||

| Fatigue | 17 | 2 | 3 | 0 | 3/45 (6.7) |

| Carboplatin allergic reaction | 1 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 2/45 (4.4) |

| Dehydration | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 2/45 (4.4) |

| Weight loss | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Headache | 14 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

* For 21 patients on olaparib 400mg twice a day (days 1–7) with carboplatin area under the curve 5 dose and schedule: grade 3 neutropenia (n = 15 patients), grade 3 anemia (n = 3 patients), grade 4 anemia (n = 1 patient), grade 3 thrombocytopenia (n = 3 patients), grade 4 thrombocytopenia (n = 1 patient; her bone marrow function recovered without platelet transfusions). AST = aspartate aminotransferase; ALT = alanine aminotransferase; Cr = creatinine.

Clinical Activity

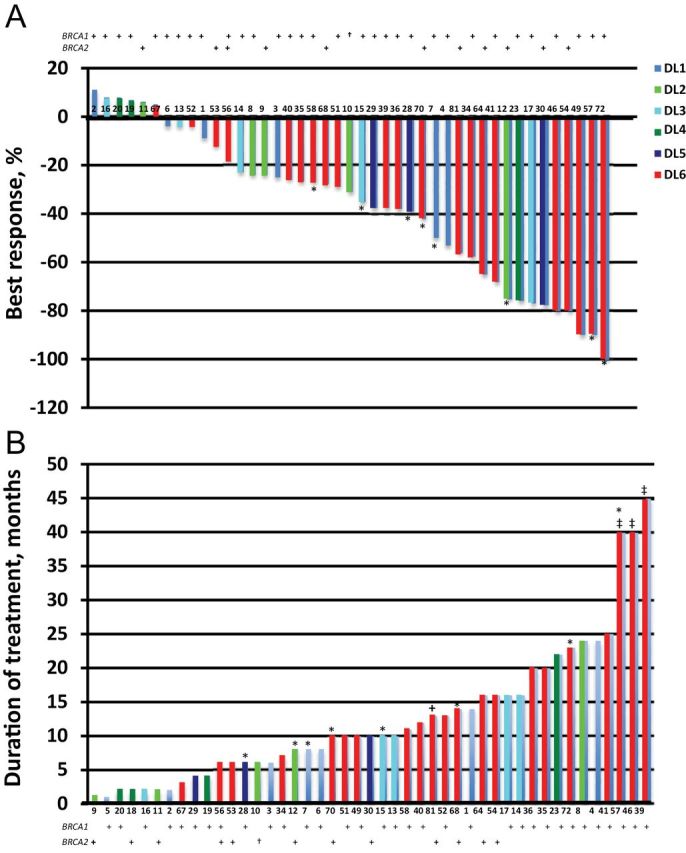

All patients had RECIST measurable or evaluable disease, and 42 were evaluable for response determination (Figure 2; Table 4); 3 patients discontinued treatment during cycle 1 or 2 because of withdrawal (1) and intercurrent illness (2), without evidence of progression. Confirmed objective responses were observed in 22 of 42 patients (52.4%). One BrCa patient achieved a complete response (duration = 23 months); 6 others had a partial response for a total response rate of 87.5% in the BrCa patients. Ten of 14 (71.4%) platinum-sensitive and five of 20 (25.0%) platinum-resistant/refractory OvCa patients attained partial response with median duration of response of 16 months (range = 4 to >45 months) and 13 months (range = 6 to >40 months), respectively. Nine of 20 (45.0%) platinum-resistant/refractory OvCa patients had stable disease (SD) with a median duration of response 10 months (range = 6–16 months), making a clinical benefit rate of 70.0% in platinum-resistant/refractory OvCa patients. There was no statistically significant difference in PFS by BRCA mutation status; again, this was underpowered for this analysis (Supplementary Figure 1, available online).

Figure 2.

Waterfall plot. Best RECIST response (A) and duration of response (B) are graphed for each patient. Color code defines dose level (DL) of treatment, and the number is an arbitrary patient assignment. The asterisk (*) represents breast cancer patients, and the dagger (†) indicates the one patient with BRCAPro score 68%. The double dagger (‡) identifies patients still receiving therapy at the time data were locked for analysis. Patient 9 was not censored for the response analysis because study treatment was discontinued after one cycle because of intercurrent illness, although computed tomography assessment at 6 weeks showed stable disease.

Table 4.

Clinical response (n = 42)*

| Best response | Ovarian cancer (n = 34)† | Breast cancer (n = 8) | Total No. (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. (%) | Median duration in months (range) | No. (%) | Median duration in months (range) | ||

| CR | 0 | 1 (12.5) | 23 | 1 (2.4) | |

| PR | 15 (44.1) | 16 (4 to >45) | 6 (75) | 10 (6 to >40) | 21 (50.0) |

| SD ≥ 4 mo | 13 (38.2) | 11 (6 to 24) | 1 (12.5) | 14 | 14 (33.3) |

| PD | 6 (17.6) | 0 | 6 (14.3) | ||

| Overall response rate | 15/34 (44.1) | 7/8 (87.5) | 22 (52.4) | ||

| Clinical benefit rate | 28/34 (82.3) | 8/8 (100)‡ | 36 (85.7) | ||

* CR = complete response; PD = progression of disease; PR = partial response; SD = stable disease.

† One patient with ovarian cancer was not censored for the response analysis because study treatment was discontinued after one cycle because of intercurrent illness, although computed tomography assessment at 6 weeks showed stable disease.

‡ One CR in triple-negative breast cancer, six PRs in triple-negative breast cancer (n = 3) and estrogen receptor/progesterone receptor (ER/PR)–positive breast cancer (n = 3), and 1 SD in ER/PR positive breast cancer were observed.

Translational Studies

PAR concentrations were measured in PBMCs taken at baseline from 33 of 45 patients, and paired PAR concentrations were measured after cycle 1 in 30 of 33 patients. Inadequate PBMC DNA was the major limitation to measuring PAR concentrations in all patients. No correlation was seen between initial PAR incorporation and clinical activity. Decrease in PAR incorporation by greater than 50% after one cycle was observed in 19 of 30 patients and did not correlate with response or PFS.

Polymorphisms were examined in the 15 expansion cohort patients with no statistically significant associations detected (Supplementary Table 1, available online).

The mean apoptotic index at baseline was 53.3% (standard deviation = 27.4%–68.0%) and increased to 77.6% (standard deviation = 53.2%–90.3%) post-cycle1 (p=0.02). The percentage apoptotic index change per patient trended to inversely correlate with duration of response (P = .07; R 2 = 0.497) (Supplementary Figure 2, available online).

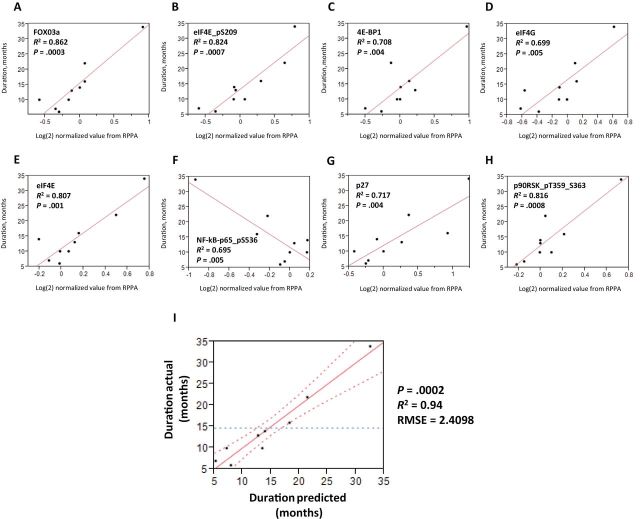

The relationship between protein expression in pretreatment biopsies and response frequency and duration was examined for 167 proteins by RPPA. Nine of 10 patients had a response duration of 6 or more months (8 partial response; 1 stable disease). Their proteomic results were used for development of a response predictor. Initial analysis indicated eight targets statistically significantly correlated with response duration after Hochberg correction. eIF4E, FOXO3a, pS209-eIF4E, pT359/S363-p90RSK, 4E-BP1, eIF4G, pS536-NFkB p65, and p27 were differentially expressed between patients with short and long times on study; the level of expression correlated positively or negatively with the patient’s duration of response to olaparib/carboplatin (Figure 3, A–H). We next examined the data to determine which differences statistically significantly contributed to a linear model predicting response duration. This examination limited the model to pS209-eIF4E and FOXO3a. The two-factor model efficiently predicts the duration of survival among this cohort of patients, as shown by the strong correlation between actual and predicted duration (P < .001; R 2 = 0.94; root mean square error = 2.41) (Figure 3I).

Figure 3.

The relationship between pretreatment biopsy protein expression and response duration. A cutoff of R 2 of 0.8 was used to select the top potential predictive biomarkers. A–H) Eight proteins were statistically significantly correlated with progression-free survival (PFS) of 6 or more months. I) pS209-eIF4E and FOXO3a were isolated as drivers for the PFS outcome (P < .001; R 2 = 0.94; root mean square error [RMSE] = 2.41). Reverse-phase protein arrays (RPPAs) were analyzed for correlations between pretreatment protein levels and duration of response with a two-tailed analysis of variance and controlled for false discovery rate of 0.05.

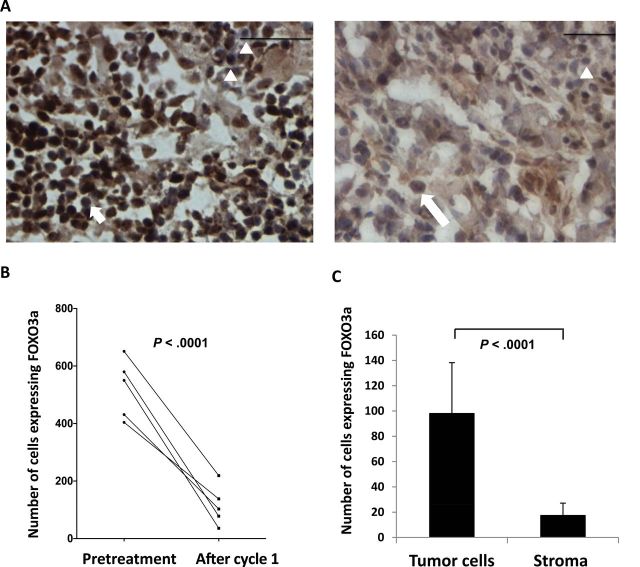

We sought to confirm RPPA results by immunohistochemistry in biopsy specimens. We measured expression of the two proteins found to be predictive of response duration, FOXO3a and pS209-eIF4E, in paired frozen tumor sections, available for five of nine patients. FOXO3a-positive cells were statistically significantly reduced in frequency after one cycle of treatment in all five patients (Figure 4A). The mean of FOXO3a-positive cells was 3.8-fold higher before therapy compared with after 1 cycle of treatment (P < .001) (Figure 4B). Greater FOXO3a staining was observed in tumor cells, confirming them as the source of the FOXO3a signal (P < .001 vs stroma) (Figure 4C). Staining of pS209-eIF4E was poorly reproducible.

Figure 4.

Validation of FOXO3a using immunohistochemistry. A) Example of paired FOXO3a stained biopsy set (×400 magnification). Left: pretreatment biopsy. Right: after cycle 1 (C1). Arrowheads: negatively stained nuclei, note similar intensity in pre– and post–cycle 1 samples. Short arrow: tumor cells with positively stained nuclei. Long arrow: tumor cell with positively stained cytosol. Scale bar = 50 μm. B) FOXO3a-positive tumor cell nuclei are reduced after one cycle of treatment. Paired samples sets for five patients were available for enumeration. The mean of FOXO3a-positive cells at baseline vs post-cycle 1 treatment: 427.73 (range = 181–758; standard deviation (SD) = 198.96; 95% confidence interval [CI] = 229.77 to 625.69) vs 112 (range = 19–358; SD = 90.89; 95% CI = 20.78 to 202.58; P < .0001). C) Tumor cells are the source of the FOXO3a signal (P < .001). Tumor and stromal cells with positively stained nuclei were counted per five high-power fields. The median of immunohistochemistry results between tumor and stromal cells were compared using a two-tailed paired Student t test.

Discussion

Recurrent gBRCAm BrCa/OvCa is not curable and constitutes an important unmet clinical need. The PARPi class has interesting clinical potential (15–17), although its optimal use remains undefined. Ongoing clinical trials are testing PARPis alone or in combination with chemotherapy and at various points in a patient’s therapeutic lifetime. We show that addition of olaparib to carboplatin can be given safely and yields clinical benefit in women with gBRCAm BrCa/OvCa who have received multiple prior chemotherapy regimens. Twice-daily continuous olaparib with every-3-week carboplatin was tolerable and active. Expected overlapping toxicities of nausea and bone marrow suppression were observed, and cytopenias were dose limiting with continuous olaparib. Maximization of carboplatin to AUC5 required an intermittent olaparib schedule, 400mg twice daily for days 1 to 7 of a 21-day cycle. Activity was seen with this intermittent schedule. This combination dose can be administered on a 3-week cycle for up to eight cycles with 48.9% of patients requiring growth factor support; maintenance olaparib at full dose on a continuous schedule until disease progression was well tolerated. Our exploratory translational studies suggest that pretreatment tumor FOXO3a expression may represent a biomarker predictive for response to the combination.

PARPis have demonstrated activity for treatment of gBRCAm-associated and BRCA-like cancers, either as single agents or in combination with DNA-damaging agents (16–18,40–42). The majority (85.7%) of our patients had clinical benefit by prolonged stable disease and/or reduction in tumor size. Response rates of 44.1% in OvCa and 87.5% in BrCa suggest at least additive effects by these agents. The rate and duration of response to olaparib monotherapy has been associated with platinum sensitivity (16). In our cohort, two-thirds of OvCa patients were either platinum resistant or refractory, yet had a response rate of 25.0% and a clinical benefit rate of 70.0%. This may reflect the effect of PARPi itself. These findings support the hypothesis that tumors with DNA repair defects may be sensitive to PARPi-based therapy even after acquiring platinum resistance.

Our findings present an opportunity to develop rational combinations of PARPis with other DNA-damaging agents. This is an area of much interest in the community, and the optimal method for administration of PARPi, intermittent vs continuous, is still under investigation. Unfortunately, the combination of PARPis with cytotoxic chemotherapy has been hampered by overlapping toxicities yielding increased gastrointestinal complaints and increased myelotoxicity, limiting the dose of olaparib and/or chemotherapy (43,44). Further studies are needed to determine whether the combination affects long-term patient outcomes, similar to what has been shown for PFS2, the time between initiation of olaparib and disease progression on a subsequent therapy, in the randomized, placebo-controlled phase II olaparib maintenance study in platinum-sensitive relapsed OvCa (41,45).

Our study has some limitations. First, a small sample size may introduce biases in estimating response rate. Second, response rate and PFS were secondary objectives, and the study was not powered to address these questions. The translational endpoints were exploratory in nature, and although controlling for multiple comparisons was performed to reduce the incidence of type 1 errors, all findings will need to be examined in a prospective nature before definitive conclusions can be drawn. The translational tissue observations came from core needle biopsies of a lesion selected for the safety of biopsy rather than a specific clinical characteristic; these biochemical results may vary within intrinsically heterogeneous lesions. Together our findings are provocative and will require a prospectively powered examination of activity.

The susceptibility of patients with gBRCAm BrCa/OvCa to DNA-damaging agents, including PARPis, has validated gBRCAm as a predictive biomarker for PARPi response (18,46). However, the challenge remains to identify, develop, and validate effective biomarkers to apply within this patient population to predict who is likely to benefit from PARPi therapies. Several areas under development include functional assessments of telomeric instability as a marker of HR deficiency (47,48), BRCA2 silencing by promoter hypermethylation, collateral gene alteration such as EMSY amplification, or events such as mutations in other genes in the HR deficiency/Fanconi anemia pathway genes (49–51). We prospectively planned to measure PAR incorporation into PBMC DNA and confirmed this assay does not predict clinical benefit (18,42,52).

Our exploratory proteomic analyses indicate that the levels of eight proteins were correlated with length of response to olaparib/carboplatin. Statistical modeling identified FOXO3a and pS209-eIF4E as the best predictors of response duration. FOXO3a was originally reported as a tumor suppressor gene in human cancers, associated with cell cycle regulation through Fas-mediated death (53). Multiple preclinical studies have shown that FOXO3a promotes phosphorylation of ATM at S1981 and activates the ATM–Chk2–p53-mediated apoptotic program in response to DNA damage (54,55). Our data confirm that increased FOXO3a expression before treatment correlated with longer duration of response to olaparib/carboplatin. Greater than 70% reduction in FOXO3a-positive cells after one cycle of treatment occurred in five tested patients with prolonged response. Studies with a larger cohort are needed to examine FOXO3a and pS209-eIF4E as integrated predictive biomarkers. Increased eIF4E has been associated with malignant progression (56,57) and enhancement of expression of c-Myc and matrix metalloproteinase 9, both important in OvCa (58,59). Our data linked increased baseline pS209-eIF4E expression with a longer duration response; this was not reproducible using phospho-specific immunohistochemistry, likely because of technical challenges, including our tumor biopsies being stored as fresh frozen specimens, poor antibody affinity, and/or instability of the phosphorylation site.

There are now a number of PARPis in phase I to III clinical investigation in BrCa and OvCa, many focusing on gBRCAm patients. The drug class has tolerable toxicity profiles with reports of prolonged daily drug administration for at least 3 years (13). Identification of patients with predictive markers will facilitate individualizing therapy. Our data suggest further clinical exploration of olaparib in combination with carboplatin followed by olaparib maintenance is warranted in patients with gBRCAm-associated cancers. Dissecting the influence of key proteins in DSB DNA repair and evaluating the role of FOXO3a will provide evidence to inform subsequent PARPi studies.

Funding

This clinical trial and translational studies were funded by the Intramural Program of the Center for Cancer Research, NCI, National Institutes of Health. The PAR assay was funded in part by NCI Contract No. HHSN261200800001E (JJ/JD). Olaparib was supplied to the Center for Cancer Research, NCI under a Cooperative Research and Development Agreement between the CCR/NCI and AstraZeneca.

The corresponding and senior authors had access to all the data and made the final decision to submit for publication. The study sponsors had no role in the design of the study; the collection, analysis, and interpretation of the data; the writing of the manuscript; and the decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

We thank Dr Seth Steinberg for his inputs on statistical analyses. We also thank Nicole Houston, RN, and Jennifer Squires, RN, CRNP, for their contributions in clinic.

References

- 1. Hoeijmakers JH. DNA repair mechanisms. Maturitas. 2001;38(1):17–22; discussion 22–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Rodon J, Iniesta MD, Papadopoulos K. Development of PARP inhibitors in oncology. Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 2009;18(1):31–43 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Annunziata CM, O’Shaughnessy J. Poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase as a novel therapeutic target in cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2010;16(18):4517–4526 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Tomoda T, Kurashige T, Moriki T, et al. Enhanced expression of poly(ADP-ribose) synthetase gene in malignant lymphoma. Am J Hematol. 1991;37(4):223–227 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Barnett JC, Bean SM, Nakayama JM, et al. High poly(adenosine diphosphate-ribose) polymerase expression and poor survival in advanced-stage serous ovarian cancer. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;115(1):49–54 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bieche I, de Murcia G, Lidereau R. Poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase gene expression status and genomic instability in human breast cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 1996;2(7):1163–1167 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Helleday T, Petermann E, Lundin C, et al. DNA repair pathways as targets for cancer therapy. Nat Rev Cancer. 2008;8(3):193–204 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Patel AG, Sarkaria JN, Kaufmann SH. Nonhomologous end joining drives poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP) inhibitor lethality in homologous recombination-deficient cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108(8):3406–3411 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Farmer H, McCabe N, Lord CJ, et al. Targeting the DNA repair defect in BRCA mutant cells as a therapeutic strategy. Nature. 2005;434(7035):917–921 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Hartwell LH, Szankasi P, Roberts CJ, et al. Integrating genetic approaches into the discovery of anticancer drugs. Science. 1997;278(5340):1064–1068 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Iglehart JD, Silver DP. Synthetic lethality—a new direction in cancer-drug development. N Engl J Med. 2009;361(2):189–191 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Bryant HE, Schultz N, Thomas HD, et al. Specific killing of BRCA2-deficient tumours with inhibitors of poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase. Nature. 2005;434(7035):913–917 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Kaye SB, Lubinski J, Matulonis U, et al. Phase II, open-label, randomized, multicenter study comparing the efficacy and safety of olaparib, a poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase inhibitor, and pegylated liposomal doxorubicin in patients with BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations and recurrent ovarian cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30(4):372–379 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Gelmon KA, Tischkowitz M, Mackay H, et al. Olaparib in patients with recurrent high-grade serous or poorly differentiated ovarian carcinoma or triple-negative breast cancer: a phase 2, multicentre, open-label, non-randomised study. Lancet Oncol. 2011;12(9):852–861 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Fong PC, Yap TA, Boss DS, et al. Poly(ADP)-ribose polymerase inhibition: frequent durable responses in BRCA carrier ovarian cancer correlating with platinum-free interval. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(15):2512–2519 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Audeh MW, Carmichael J, Penson RT, et al. Oral poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase inhibitor olaparib in patients with BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations and recurrent ovarian cancer: a proof-of-concept trial. Lancet. 2010;376(9737):245–251 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Tutt A, Robson M, Garber JE, et al. Oral poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase inhibitor olaparib in patients with BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations and advanced breast cancer: a proof-of-concept trial. Lancet. 2010;376(9737):235–244 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Fong PC, Boss DS, Yap TA, et al. Inhibition of poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase in tumors from BRCA mutation carriers. N Engl J Med. 2009;361(2):123–134 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Alsop K, Fereday S, Meldrum C, et al. BRCA mutation frequency and patterns of treatment response in BRCA mutation-positive women with ovarian cancer: a report from the Australian Ovarian Cancer Study Group. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30(21):2654–2663 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Vencken PM, Kriege M, Hoogwerf D, et al. Chemosensitivity and outcome of BRCA1- and BRCA2-associated ovarian cancer patients after first-line chemotherapy compared with sporadic ovarian cancer patients. Ann Oncol. 2011;22(6):1346–1352 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Chetrit A, Hirsh-Yechezkel G, Ben-David Y, et al. Effect of BRCA1/2 mutations on long-term survival of patients with invasive ovarian cancer: the national Israeli study of ovarian cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(1):20–25 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Nguewa PA, Fuertes MA, Cepeda V, et al. Poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase-1 inhibitor 3-aminobenzamide enhances apoptosis induction by platinum complexes in cisplatin-resistant tumor cells. Med Chem. 2006;2(1):47–53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Kortmann U, McAlpine JN, Xue H, et al. Tumor growth inhibition by olaparib in BRCA2 germline-mutated patient-derived ovarian cancer tissue xenografts. Clin Cancer Res. 2011;17(4):783–791 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. BayesMendel Lab. http://bcb.dfci.harvard.edu/bayesmendel/brcapro.php Accessed October 12, 2013

- 25. Therasse P, Arbuck SG, Eisenhauer EA, et al. New guidelines to evaluate the response to treatment in solid tumors. European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer, National Cancer Institute of the United States, National Cancer Institute of Canada. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2000;92(3):205–216 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Kinders RJ, Hollingshead M, Khin S, et al. Preclinical modeling of a phase 0 clinical trial: qualification of a pharmacodynamic assay of poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase in tumor biopsies of mouse xenografts. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14(21):6877–6885 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Gao R, Price DK, Sissung T, et al. Ethnic disparities in Americans of European descent versus Americans of African descent related to polymorphic ERCC1, ERCC2, XRCC1, and PARP1. Mol Cancer Ther. 2008;7(5):1246–1250 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Lee JM, Hays JL, Noonan AM, et al. Feasibility and safety of sequential research-related tumor core biopsies in clinical trials. Cancer. 2013;119(7):1357–1364 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Azad N, Yu M, Davidson B, et al. Translational predictive biomarker analysis of the phase 1b sorafenib and bevacizumab study expansion cohort. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2013;12(6):1621–1631 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Posadas EM, Kwitkowski V, Kotz HL, et al. A prospective analysis of imatinib-induced c-KIT modulation in ovarian cancer: a phase II clinical study with proteomic profiling. Cancer. 2007;110(2):309–317 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Posadas EM, Liel MS, Kwitkowski V, et al. A phase II and pharmacodynamic study of gefitinib in patients with refractory or recurrent epithelial ovarian cancer. Cancer. 2007;109(7):1323–1330 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Winters M, Dabir B, Yu M, et al. Constitution and quantity of lysis buffer alters outcome of reverse phase protein microarrays. Proteomics. 2007;7(22):4066–4068 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Rasool N, LaRochelle W, Zhong H, et al. Secretory leukocyte protease inhibitor antagonizes paclitaxel in ovarian cancer cells. Clin Cancer Res. 2010;16(2):600–609 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. MD Anderson Cancer Center. http://www.mdanderson.org/education-and-research/resources-for-professionals/scientific-resources/core-facilities-and-services/functional-proteomics-rppa-core/index.html Accessed March 26, 2014

- 35. Jackson S, Ghali L, Harwood C, et al. Reduced apoptotic levels in squamous but not basal cell carcinomas correlates with detection of cutaneous human papillomavirus. Br J Cancer. 2002;87(3):319–323 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Hochberg Y. A sharper Bonferroni procedure for multiple tests of significance. Biometrika. 1988;75(4):800–802 [Google Scholar]

- 37. Yang JY, Yoshihara K, Tanaka K, et al. Predicting time to ovarian carcinoma recurrence using protein markers. J Clin Invest. 2013;123(12):5410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Cardnell RJ, Feng Y, Diao L, et al. Proteomic markers of DNA repair and PI3K pathway activation predict response to the PARP inhibitor BMN 673 in small cell lung cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2013;19(22):6322–6328 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Moon DH, Lee JM, Noonan AM, et al. Deleterious BRCA1/2 mutation is an independent risk factor for carboplatin hypersensitivity reactions. Br J Cancer. 2013;109(4):1072–1078 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Sandhu SK, Schelman WR, Wilding G, et al. The poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase inhibitor niraparib (MK4827) in BRCA mutation carriers and patients with sporadic cancer: a phase 1 dose-escalation trial. Lancet Oncol. 2013;14(9):882–892 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Ledermann J, Harter P, Gourley C, et al. Olaparib maintenance therapy in platinum-sensitive relapsed ovarian cancer. N Engl J Med. 2012;366(15):1382–1392 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Kummar S, Ji J, Morgan R, et al. A phase I study of veliparib in combination with metronomic cyclophosphamide in adults with refractory solid tumors and lymphomas. Clin Cancer Res. 2012;18(6):1726–1734 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Oza AM, Cibula D, Oaknin A, Poole CJ, Mathijssen RHJ, Sonke GS, Colombo N, ŠPacek J, Vuylsteke P, Hirte HW, Mahner S, Plante M, Schmalfeldt B, Mackay H, Rowbottom J, Tchakov I, Friedlander M. Olaparib plus paclitaxel plus carboplatin (P/C) followed by olaparib maintenance treatment in patients (pts) with platinum-sensitive recurrent serous ovarian cancer (PSR SOC): a randomized, open-label phase II study. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30(Suppl):abstract 5001. [Google Scholar]

- 44. Rajan A, Carter CA, Kelly RJ, et al. A phase I combination study of olaparib with cisplatin and gemcitabine in adults with solid tumors. Clin Cancer Res 2012;18(8):2344–2351 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Ledermann JA, Harter P, Gourley C, Friedlander M, Vergote I, Rustin GJ, Scott CL, Meier W, Shapira-Frommer R, Safra T, Matei D, Fielding A, Macpherson E, Dougherty B, Jürgensmeier JM, Orr M, Matulonis U. Olaparib maintenance therapy in patients with platinum-sensitive relapsed serous ovarian cancer (SOC) and a BRCA mutation (BRCAm). J Clin Oncol. 2013;31(Suppl):abstract 5505. [Google Scholar]

- 46. Safra T, Borgato L, Nicoletto MO, et al. BRCA mutation status and determinant of outcome in women with recurrent epithelial ovarian cancer treated with pegylated liposomal doxorubicin. Mol Cancer Ther. 2011;10(10):2000–2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Birkbak NJ, Wang ZC, Kim JY, et al. Telomeric allelic imbalance indicates defective DNA repair and sensitivity to DNA-damaging agents. Cancer Discov. 2012;2(4):366–375 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Graeser M, McCarthy A, Lord CJ, et al. A marker of homologous recombination predicts pathologic complete response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy in primary breast cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2010;16(24):6159–6168 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Konstantinopoulos PA, Spentzos D, Karlan BY, et al. Gene expression profile of BRCAness that correlates with responsiveness to chemotherapy and with outcome in patients with epithelial ovarian cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(22):3555–3561 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Veeck J, Ropero S, Setien F, et al. BRCA1 CpG island hypermethylation predicts sensitivity to poly(adenosine diphosphate)-ribose polymerase inhibitors. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(29):e563–e564; author reply e565–e566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Walsh T, Casadei S, Lee MK, et al. Mutations in 12 genes for inherited ovarian, fallopian tube, and peritoneal carcinoma identified by massively parallel sequencing. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108(44):18032–18037 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Kummar S, Kinders R, Gutierrez ME, et al. Phase 0 clinical trial of the poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase inhibitor ABT-888 in patients with advanced malignancies. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(16):2705–2711 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Chiacchiera F, Simone C. The AMPK-FoxO3A axis as a target for cancer treatment. Cell Cycle. 2010;9(6):1091–1096 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Tsai WB, Chung YM, Takahashi Y, et al. Functional interaction between FOXO3a and ATM regulates DNA damage response. Nat Cell Biol. 2008;10(4):460–467 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Chung YM, Park SH, Tsai WB, et al. FOXO3 signalling links ATM to the p53 apoptotic pathway following DNA damage. Nat Commun. 2012;3:1000. 1000.10.1038/ncomms2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Pettersson F, Yau C, Dobocan MC, et al. Ribavirin treatment effects on breast cancers overexpressing eIF4E, a biomarker with prognostic specificity for luminal B-type breast cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2011;17(9):2874–2884 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Coleman LJ, Peter MB, Teall TJ, et al. Combined analysis of eIF4E and 4E-binding protein expression predicts breast cancer survival and estimates eIF4E activity. Br J Cancer. 2009;100(9):1393–1399 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Ross JS, Ali SM, Wang K, et al. Comprehensive genomic profiling of epithelial ovarian cancer by next generation sequencing-based diagnostic assay reveals new routes to targeted therapies. Gynecol Oncol. 2013;130(3):554–559 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Sillanpaa S, Anttila M, Voutilainen K, et al. Prognostic significance of matrix metalloproteinase-9 (MMP-9) in epithelial ovarian cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 2007;104(2):296–303 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]