Introduction

Dysregulation in mineral and bone metabolism may contribute to the development of vascular calcification, cardiovascular disease and adverse clinical outcomes in patients with end-stage renal disease1. Clinical management of mineral and bone disorder (MBD) is typically based on repeated measurement of laboratory markers, specifically parathyroid hormone (PTH) calcium, and phosphorus, and therapeutic interventions aimed at keeping these MBD markers within specific target ranges. The 2009 Kidney Disease Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) guidelines2 and the 2010 Kidney Disease Outcomes Quality Initiative (KDOQI) US commentary3 suggest different target levels for these markers than previously recommended in the 2003 KDOQI guideline.4 The most notable change was a less stringent range for PTH levels, with the previously recommended range of 150–300 pg/mL relaxed to 2–9 times the upper limit of assay normal (approximately 130–600 pg/mL). These different recommended target ranges may have led to changes in clinical practices in the field of MBD. Additionally, the End-Stage Renal Disease Prospective Payment System (PPS)5 implemented in January 2011 also may have led to changes in utilization of MBD-related intravenous drugs. For example, the PPS may have impactedprescription of vitamin D analoguesespecially among patient subgroups that require higher average doses6 (i.e., black patients, Medicaid recipients, and patients aged < 55).

Using data from the national sample of the US Dialysis Outcomes and Practice Patterns Study (DOPPS) Practice Monitor (DPM), we report trends in serum PTH, calcium, and phosphorus levels, MBD therapies, and nephrologist survey data between August 2010 and April 2013.

Methods

We used data from the August 2013 edition of the DPM (www.dopps.org/dpm) in these analyses. Each monthly cross-section between August 2010 and April 2013 included approximately 3489 patients. Trend outcomes reported here include serum levels of PTH, total calcium, and phosphorus; MBD-related treatments including intravenous (IV) and oral vitamin D analogues, cinacalcet, and phosphate binders; and MBD targets reported from surveys of DOPPS medical directors between 2009 and 2012.

Trends in upper target levels of MBD markers were analyzed with the Mantel-Haenszel chi-square test. Survey-weighted linear and logistic regressions were used to model longitudinal trends in serum levels of PTH (log-transformed), total calcium, and phosphorus, as well as the proportion of patients with PTH ≥600 pg/mL. Contrast adjustments included time (using a linear spline with 1 knot at April 2011 to improve model fit), race (black vs. non-black), Medicaid status (yes vs. no), and age group (< 55 vs. ≥55).

Results

Trends in facility-reported MBD targets

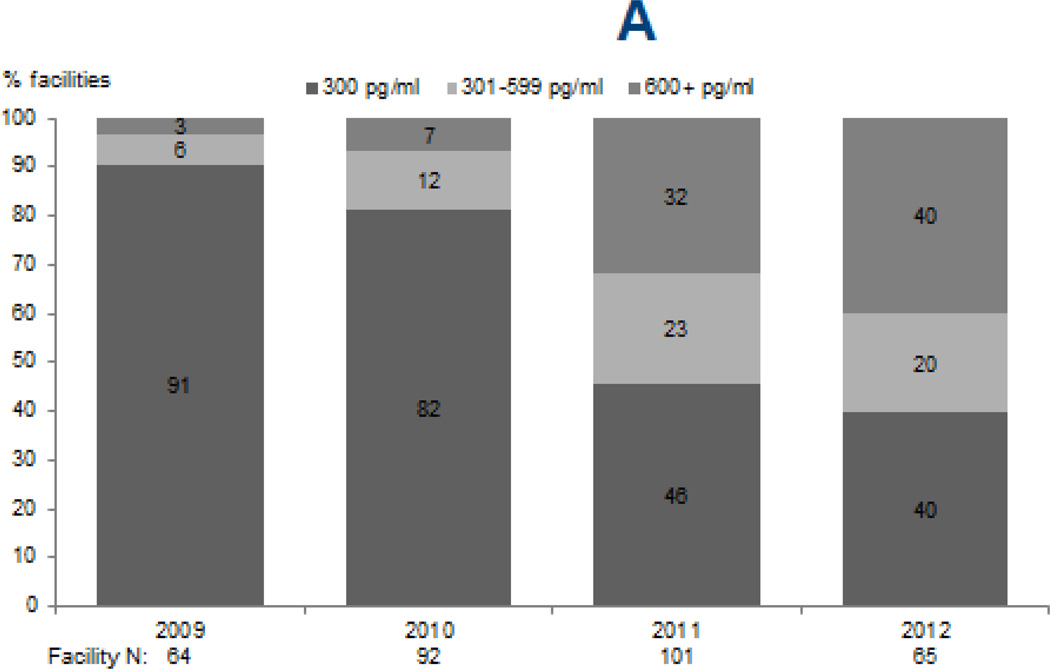

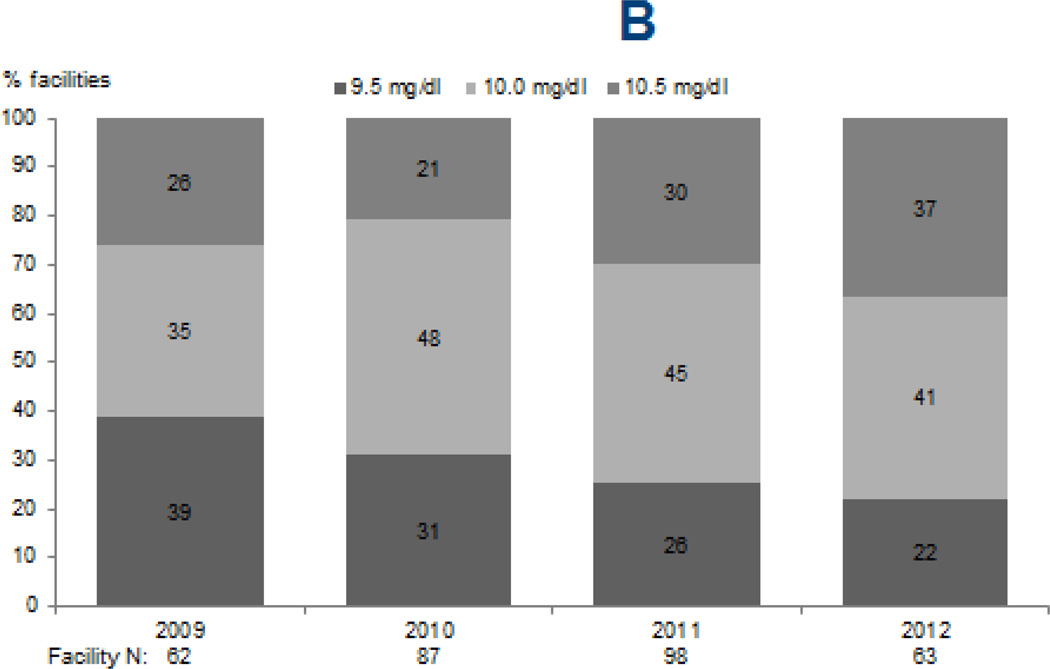

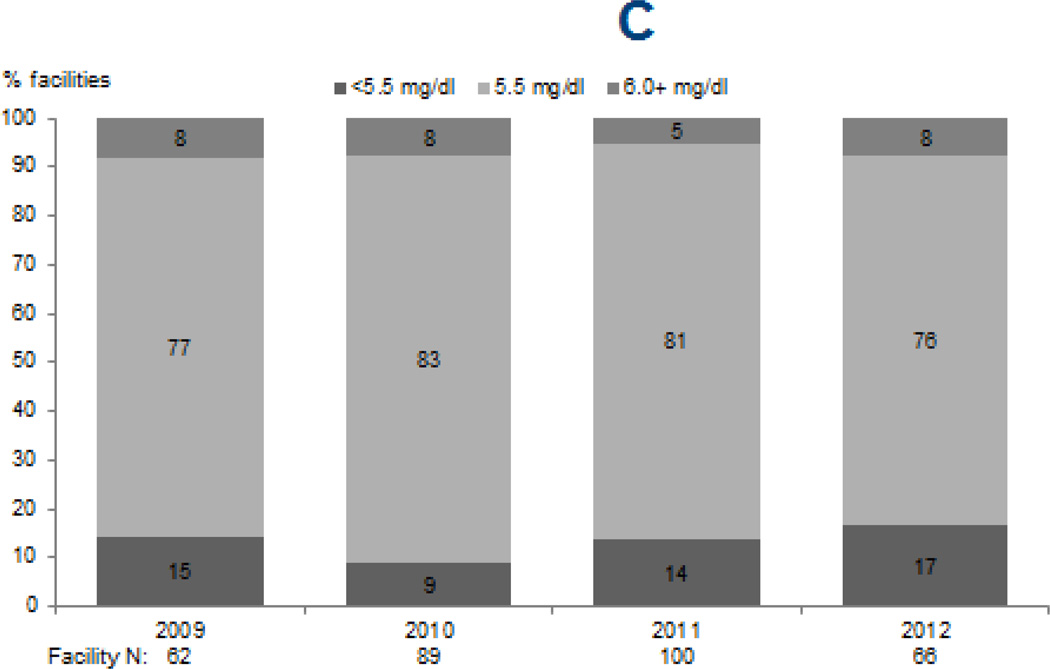

Upper limits of targets for PTH (p < 0.0001) and calcium (p=0.02) increased from 2009 through 2012, while phosphorus targets remained largely unchanged (Figure 1). The percentage of facilities reporting an upper PTH target of ≥600 pg/mL sharply increased from 3% and 7% in 2009 and 2010 to 40% in 2012. Likewise, the percentage of facilities reporting an upper limit for calcium target of 10.5 mg/dL increased from 26% and 21% in 2009 and 2010 to 37% in 2012. The majority of facilities (76–83%) reported an upper phosphorus target of 5.5 mg/dL in each survey year, with no clear trend observed (p=0.4).

Figure 1. Facility-reported upper levels of target ranges for markers of mineral and bone disorder, 2009–2012.

Legend: Data reflect upper limits of targets reported by DOPPS medical directors for serum PTH (A), total serum calcium (B), and serum phosphorus (C) during DOPPS phases 4 (2009–2011) and 5 (2012).

Trends in serum PTH levels and related treatments

The median proportion of patients per facility-month with a reported measurement of PTH within 3 months declined modestly, by 2% per year from 100% in 2010 to 94% in 2013. Similarly, the adjusted odds of an individual patient having a PTH measurement reported within a 3 month period declined significantly from August 2010 to April 2013 (OR=0.98/month, 95% CI=0.97–0.99).

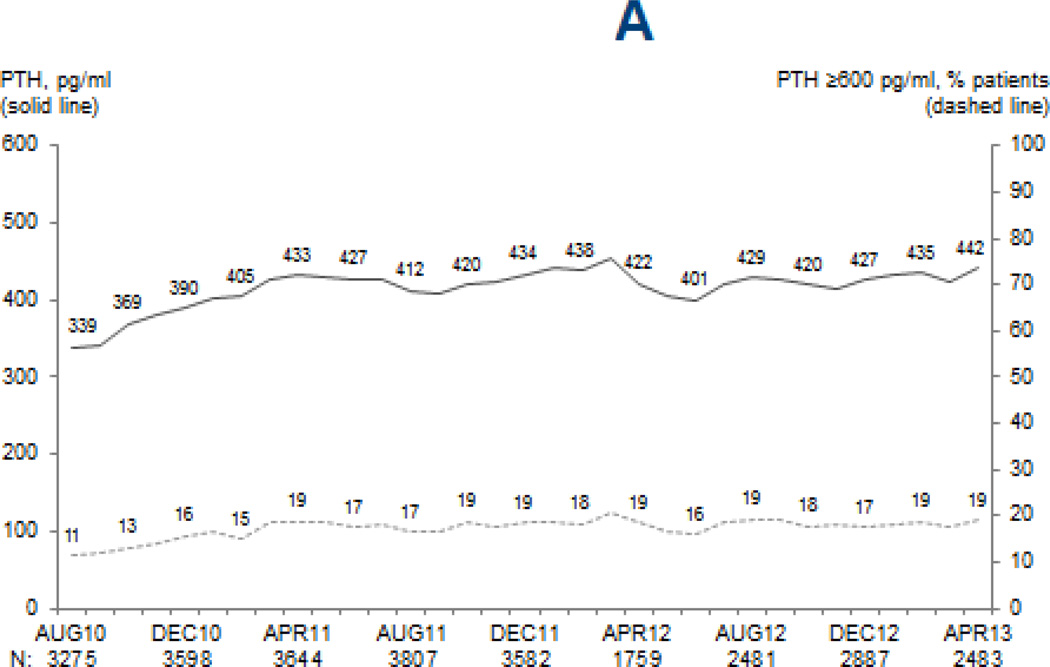

Mean (median) PTH levels increased from 339 pg/mL (245 pg/mL) in August 2010 to 433 pg/mL (321 pg/mL) in April 2011, increases of 28% and 31% respectively (p < 0.0001), but remained relatively stable since then (p=0.1) (Figure 2). Between August 2010 and April 2013, the percentage of patients with PTH ≥600 pg/mL nearly doubled, from 11% to 19%, and the percentage of patients with PTH ≥300 pg/mL increased from 36% to 56%. Although the relative increases in mean PTH were not different for black patients (p=0.3 vs. non-black), patients < 55 years old (p=0.1 vs. 55+) and patients with Medicaid (p=0.3 vs. non-Medicaid), mean absolute PTH levels remained higher in each of these subgroups (all p < 0.001).

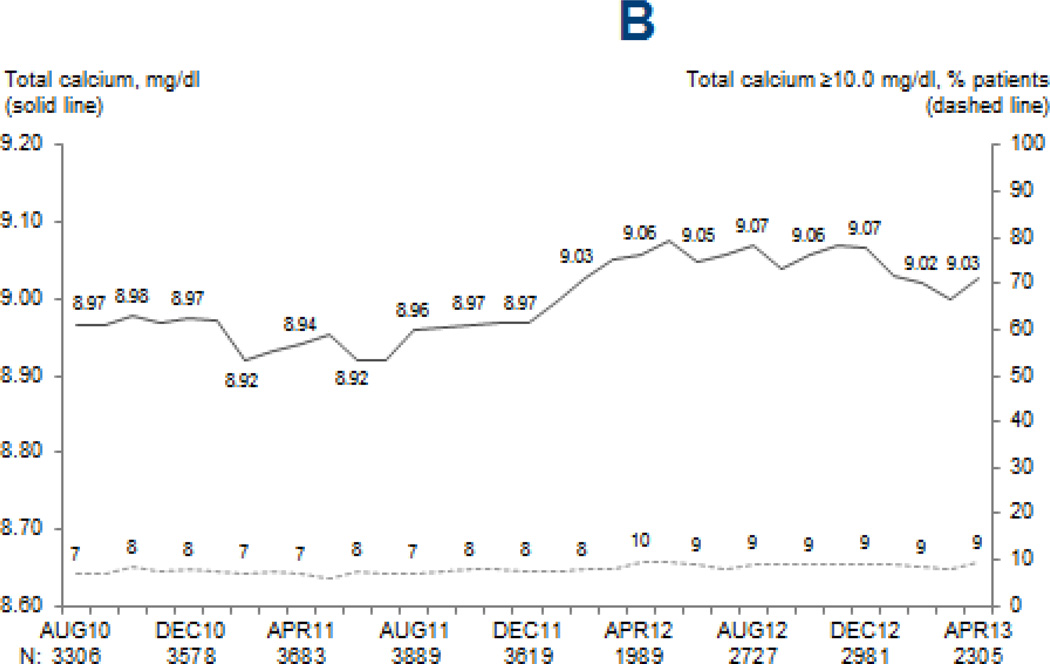

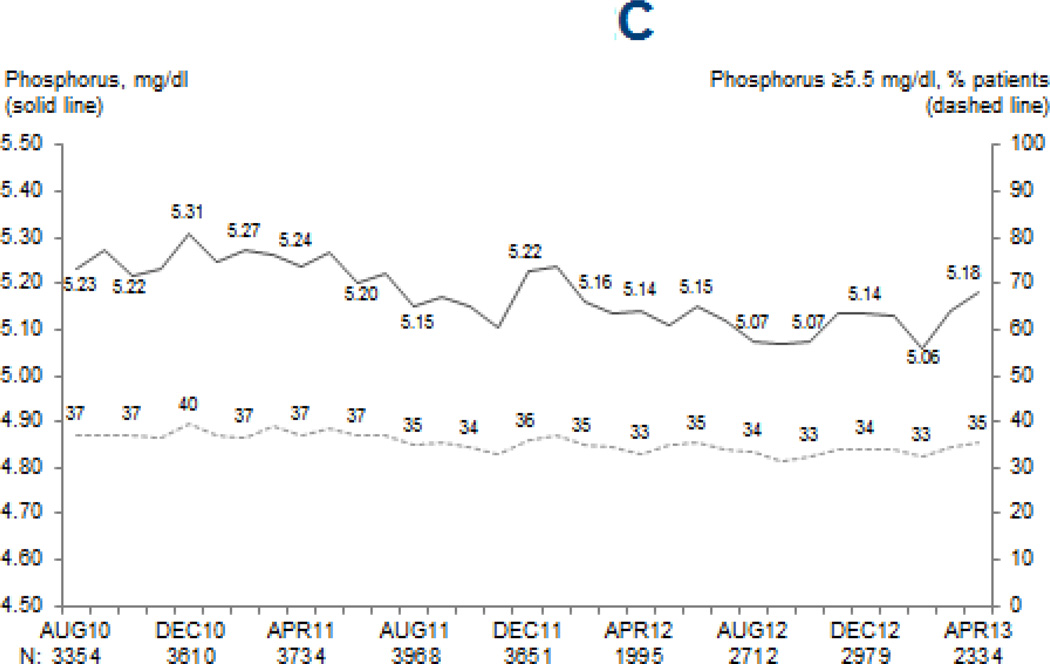

Figure 2. Mean MBD marker levels and proportion of patients above clinically-relevant cutpoints.

Legend: Values at each month are based on the most recent monthly value obtained within the prior 3 months for serum PTH (A), and most recent monthly values for total serum calcium (B) and serum phosphorus (C). Adapted from the DOPPS Practice Monitor with permission of Arbor Research Collaborative for Health.

Mean PTH levels in 2012 were on average 10.4% higher among patients in facilities reporting an upper PTH target of 600 pg/mL vs. 300 pg/mL (p=0.09). Overall, no clear changes were observed for IV vitamin D prescription (73.5%; trend p=0.9) or cinacalcet prescription (22.7%; trend p=0.2). Although many facilities switched IV vitamin D preparation from paricalcitol to doxercalciferol during this time period (p=0.003), the increase in PTH did not differ by doxercalciferol vs. paricalcitol prescription among treated patients (preparation-time interaction p=0.9).

Trends in serum calcium and phosphorus levels and related treatments

The reported measurement frequency of serum calcium (p=0.8; mean=94%/month) and serum phosphorus (p=0.2; mean=95%/month) did not change over time. While statistically significant, the observed increase in serum calcium (from 8.97 to 9.03 mg/dL; p=0.003) and decrease in serum phosphorus (from 5.23 to 5.18 mg/dL; p=0.0007) were likely too small to be clinically meaningful (Figure 2). No temporal trend in dialysate calcium was observed (p=0.7). Phosphate binder use increased slightly, from 78% to 80% (p=0.003).

Summary

During this time of clinical guideline and reimbursement policy changes, PTH levels have increased overall among US dialysis patients. Overall, this trend is consistent with findings from other DOPPS countries, with the exception of Japan7. Since no trends in therapeutic regimens were observed that may explain the rise in PTH, it is likely that changes in MBD targets suggested in the 2009 KDIGO CKD-MBD guideline played a significant role. In fact, PTH levels were higher at dialysis units that reported higher PTH target levels. Whereas the increase in the upper limit of PTH target occurred sharply between 2010 and 2011, the shift toward higher targets for serum calcium occurred more gradually.

Given the recent rise in the percentage of patients with very high PTH levels, clinicians should continue to monitor MBD markers levels. Additional studies are needed to provide a higher level of evidence supporting a specific PTH target.

References

- 1.Goodman WG, Goldin J, Kuizon BD, et al. Coronary-artery calcification in young adults with end-stage renal disease who are undergoing dialysis. N Engl J Med. 2000;342:1478–1483. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200005183422003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) CKD–MBD Work Group. KDIGO clinical practice guideline for the diagnosis, evaluation, prevention, and treatment of chronic kidney disease–mineral and bone disorder (CKD–MBD) Kidney International. 2009;76(Suppl 113):S1–S130. doi: 10.1038/ki.2009.188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Uhlig K, Berns JS, Kestenbaum B, et al. KDOQI US commentary on the 2009 KDIGO Clinical Practice Guideline for the Diagnosis, Evaluation, and Treatment of CKD-Mineral and Bone Disorder (CKD-MBD) Am J Kidney Dis. 2010;55(5):773–799. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2010.02.340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.National Kidney Foundation. K/DOQI Clinical Practice Guidelines for Bone Metabolism and Disease in Chronic Kidney Disease. Am J Kidney Dis. 2003;42(suppl 3):S1–S202. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Medicare program; end-stage renal disease prospective payment system. Final rule. Fed Regist. 2010;75(155):49029–49214. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.End-Stage Renal Disease: CMS Should Monitor Access to and Quality of Dialysis Care Promptly After Implementation of New Bundled Payment System. Washington, DC: US Government Accountability Office; 2010. US Government Accountability Office. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tentori F, Bieber BA, Morgenstern H, et al. Parathyroid Hormone (PTH) Levels Rose Over Time in Hemodialysis (HD) Patients: Results from the Dialysis Outcomes and Practice Patterns Study (DOPPS) [European Renal Association-European Dialysis and Transplant Association Congress (ERA-EDTA)Abstract] Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 2012;27(suppl 2):ii52–ii54. [Google Scholar]