Abstract

Objectives.

To examine the relationships between loneliness, social and health behaviors, health, and mortality among older adults in China.

Method.

Data came from a nationally representative sample of 14,072 adults aged 65 and older from the 2002, 2005, and 2008 waves of the Chinese Longitudinal Healthy Longevity Survey. A cross-lagged model combined with survival analysis was used to assess the relationships between loneliness, behavioral and health outcomes, and risk of mortality.

Results.

About 28% of older Chinese adults reported feeling lonely, and lonely adults faced increased risks of dying over the subsequent years. Some of the effect was explained by social and health behaviors, but most of the effect was explained by health outcomes. Loneliness both affects and is affected by social activities, solitary leisure activities, physical exercise, emotional health, self-rated health, and functional limitations over a 3-year period.

Discussion.

Loneliness is part of a constellation of poor social, emotional, and health outcomes for Chinese older adults. Interventions to increase the social involvement of lonely individuals may improve well-being and lengthen life.

Key Words: Activities, China, Cross-lagged path model, Emotional health, Functional health, Health behaviors, Loneliness, Longitudinal study, Mortality, Older adults, Self-rated health.

Loneliness is a common, distressing feeling that arises from the assessment that one’s social relationships are inadequate (Hawkley & Cacioppo, 2010; Pinquart & Sorenson, 2003). Recent research in Western countries suggests that between 20% and 40% of older adult feel lonely (Savikko, Routasalo, Tilvis, Strandberg, & Pitkälä, 2005). These feelings of loneliness are associated with a number of subsequent behavioral and health problems, such as reductions in physical activity (Hawkley, Thisted, & Cacioppo, 2009), depressive symptoms (Cacioppo, Hawkley, & Thisted, 2010), poor functional health (Luo, Hawkley, Waite, & Cacioppo, 2012), and impaired mental health and cognition (Cacioppo, Hughes, Waite, Hawkley, & Thisted, 2006; Wilson et al., 2007). Research at the biological level has linked loneliness with increased vascular resistance (Cacioppo et al., 2002; Hawkley, Berntson, Burleson, & Cacioppo, 2003), increased systolic blood pressure (Hawkley, Thisted, Masi, & Cacioppo, 2010), and altered immunity (Kiecolt-Glaser et al., 1984; Pressman et al., 2005), which could ultimately make lonely people susceptible to a variety of illness.

Although a sizeable literature has addressed the causes and consequences of loneliness in Western countries, we know little about lonely feelings in older adults in other societies (Wu et al., 2010; Yang & Victor, 2008). Family is an important source of support for older people, especially in China, where the cultural tradition emphasizes the family system and collectivism. However, the last 30 years have seen drastic declines in fertility, changes in social attitudes, and uneven rates of economic mobility, all of which have contributed to rapid increases in one-person and one-couple-only households and in the proportions of older adults who do not live with children (Zeng & Wang, 2003; Zhang, 2004). Currently, the “empty-nest elderly family” in China accounts for almost 25% of the households headed by older adults, and this number is expected to increase to 90% by 2030. One study of older adults in China using national samples showed that although about 16% felt lonely in 1992, the number has increased to nearly 30% by 2000 (Yang & Victor, 2008). These feelings of loneliness are positively associated with age, rural residency, being divorced or widowed, low social support, and poor health (Chen, Hicks, & While, 2013; Wang et al., 2011; Wu et al., 2010; Yang & Victor, 2008). But we know little about the consequences of loneliness for the subsequent health and mortality of older adults in China (Lai, 2012). Several studies showed a positive relationship between loneliness and poor health among older Chinese adults, but they were limited to small non-representative samples, most often of the empty-nest households, and they were all cross-sectional. This study examines the relationships between loneliness, social and health behaviors, physical, emotional, and functional health outcomes, and risk of mortality using a national longitudinal survey of older adults in China. The two main research questions are (a) Does loneliness predict mortality among older adults in China? (b) Is the effect of loneliness on mortality explained by social and health behaviors and by emotional, physical, and functional health?

Loneliness, Social and Health Behaviors, and Mortality

There is increasing evidence, mostly in the West, that feelings of isolation and loneliness predict mortality (Luo et al., 2012; Patterson & Veenstra, 2010; Penninx et al., 1997; Shiovitz-Ezra & Ayalon, 2010; Tilvis et al., 2004). One plausible mechanism through which loneliness increases the risk of mortality is the social and health behaviors. Cacioppo and Hawkley (2009) suggest that loneliness activates implicit hypervigilance for social threat in the environment. Chronic activation of social threat surveillance diminishes executive functioning, and heightened impulsivity reduces the ability of individuals to engage in health behaviors that require self-control. Unconscious social threat surveillance also produces cognitive biases in which lonely individuals tend to preferentially perceive, remember, and expect negative social information. Negative social expectations, in turn, tend to elicit negative behaviors from others, thereby setting in motion a self-fulfilling prophecy in which lonely people actively distance themselves from would-be social partners in self-protection believing that the cause of the social distance is out of their control (Cacioppo & Hawkley, 2009). Empirical evidence generally supports these propositions. Loneliness was found to be associated with a lower likelihood of physical activity participation and a faster decline in physical activity participation over a 2-year follow-up period (Hawkley et al., 2009). Lonely individuals were also found to be more likely to smoke (DeWall & Pond, 2011; Shankar, McMunn, Banks, & Steptoe, 2011) and to be less socially active (Hawkley et al., 2008).

Although research on the link between loneliness, health behaviors, and health or mortality in China is very limited, some recent research points to levels of some of these key measures and to associations between them. It is clear, for example, that smoking is quite widespread in China. A national prevalence survey in 1996 showed that 34% of respondents smoked, with tobacco consumption more prevalent among men (63%) than women (4%) (Yang et al., 1999). Only a minority of smokers in this survey recognized that lung cancer (36%) and heart disease (4%) can be caused by smoking. Ross and Zhang (2008) report that Chinese older adults engage in leisure activities like playing mah-jong, watching TV, or reading at levels between “never” and “sometimes” and that those who engage in these activities show lower levels of psychological distress. The same authors find that 30% of Chinese older adults report that they exercise, with exercise associated with lower levels of distress. Sun and Liu (2006) find that among the oldest old Chinese, solitary activities, either active or sedentary, are significantly associated with lower mortality risk.

Loneliness, Health, and Mortality

Although social and health behaviors may mediate the relationship between loneliness and mortality, the effect of loneliness on mortality may be more directly explained by health, as health outcomes are the more proximal predictors of mortality (Luo et al., 2012). The effects of emotional, physical, and functional health on mortality have been well documented both in China (Dupre, Liu, & Gu, 2008; Sun & Liu, 2006; Yu et al., 1998) and in the West (Ariyo et al., 2000; Everson, Roberts, Goldberg, & Kaplan, 1998; Idler & Benyamini, 1997; Okun, August, Rook, & Newsom, 2010). Because loneliness affects social and health behaviors which, in turn, affect health (Everard, Lach, Fisher, & Baum, 2000; Hao, 2008; Keysor, 2003; Lee & Park, 2006; Lennartsson & Silverstein, 2001; Menec & Chipperfield, 1997; Silverstein & Parker, 2002; Sun & Liu, 2006), we expect that loneliness also affects health outcomes. Loneliness as an adverse state was shown to be associated with feelings of sadness, anxiety, and low self-esteem and to lead to increases in depressive symptoms over time (Cacioppo et al., 2010; Hagerty & Williams, 1999; Luo et al., 2012; Wei, Russell, & Zakalik, 2005). Loneliness was also found to be negatively associated with self-rated health and to lead to declines in self-rated health over time (Nummela, Seppänen, & Uutela, 2011; Segrin & Domschke, 2011; Stephens, Alpass, Towers, & Stevenson, 2011). In addition, lonely individuals show higher levels of functional limitations (Greenfield & Russell, 2011) and are more likely to show increases in limitations (Luo et al., 2012), at least in studies in Western countries.

To our knowledge, all previous studies on loneliness and health among older Chinese adults were cross-sectional, and most of them treated loneliness as the dependent variable. These studies showed that poor self-rated health, chronic conditions, functional impairment, and cognitive impairment are significant risk factors for loneliness among older Chinese adults (Liu, Dupre, Gu, Mair, & Chen, 2012; Liu & Ni, 2003; Pan et al., 2010; Wu et al., 2009; Yang & Victor, 2008). Health was conceptualized as the outcome in a few studies, but they were limited to empty-nest older adults in selected counties/cities. For example, one study examined empty-nest rural older adults in one county of Hubei Province and found that loneliness is correlated with eight physical and mental health scales derived from the 36-Item Short-Form Health Survey, but this study did not control for other variables (Liu & Guo, 2007). Other studies showed that loneliness has significant effects on physical and mental health after controlling for demographics and social relationships. For example, Liu, Liang, and Gu (1995) find a positive relationship between loneliness and poor self-rated health among older adults in Wuhan, the capital city of Hubei Province. Wang, Shu, Dong, Luo, and Hao (2013), using a sample of empty-nest older adults in selected communities of Sichuan Province, China, find that loneliness is associated with anxiety disorder. Wu and colleagues (2011) found loneliness is associated with life satisfaction in one county of Anhui Province.

Although our study focuses on the consequences of loneliness for behavioral and health outcomes, it should be noted that behaviors and health status could also be risk factors for loneliness. Some older adults are socially isolated and have few opportunities to meet people, whereas others lack sufficient resources and skills to build and maintain meaningful social connections, both of which contribute to feeling of loneliness (de Jong Gierveld & van Tilburg, 1999). Poor health presents a barrier to establishing and maintaining a satisfying network of personal relationships (Cohen-Mansfield, Shmotkin, & Goldberg, 2009). Social activity participation provides the opportunity to meet people and can make people feel socially connected (Jylhä, 2004). Solitary leisure activity participation is often used as a coping strategy to deal with social isolation and it is suggested that constructive and enjoyable solitary activities may help alleviate loneliness by enhancing the individual’s mood and sense of control (de Jong Gierveld, van Tilburg, & Dykstra, 2006; Pettigrew & Roberts, 2008). Physical exercise improves an individual’s mood and offers opportunity for socialization, which can help combat loneliness (McAuley et al., 2000). Smoking may provide short-term relief of stress and anxiety, but it could also increase loneliness because smokers are likely to experience frequent rejection or ostracism (DeWall & Pond, 2011).

Based on previous theories and literature, we hypothesize that loneliness is positively associated with risk of subsequent mortality among older adults in China and that this effect is due at least in part to the negative effects of loneliness on social and health behaviors and on emotional, physical, and functional health. Previous studies on the effect of loneliness on mortality often measured loneliness and behavioral and health outcomes at the same time so that causal relationships could not be established. As Luo and colleagues (2012) suggest, if these behavioral and health variables are to be considered as plausible mechanisms through which loneliness affects mortality, it is necessary to show that loneliness predicts changes in behaviors and health over time while controlling for concurrent effects of these variables on loneliness.

The current study adds to what is known about the consequences of loneliness generally and to the understanding of loneliness among older adults in China. We move beyond past research by estimating cross-lagged models combined with survival analysis to assess the relationships between loneliness, behavioral and health outcomes, and risk of mortality.

Method

Data

Data came from 2002, 2005, and 2008 waves of the Chinese Longitudinal Healthy Longevity Survey (CLHLS), jointly conducted by the Institute of Population Research at Peking University, China Research Center on Aging, and Duke University. The original CLHLS is a national, longitudinal survey of Chinese adults aged 80 and older. It randomly selected about half of the total number of counties and cities of 22 provinces with the survey areas covering 985 million persons or 85% of the total population in China. The baseline survey was conducted in 1998 and the four follow-up surveys with replacement of deceased elders were conducted in 2000, 2002, 2005, and 2008. Since the 2002 wave, the survey has been expanded to also include those aged between 65 and 79 years. The survey collected information on sociodemographic characteristics; lifestyle; and physical, emotional, and cognitive health status. The interviews were carried out by an enumerator and a physician, a nurse, or a medical school student who also performed a basic health examination at the home of each respondent. The baseline survey had a response rate of 88%. Details on the survey design can be found in the study by Zeng, Vaupel, Xiao, Zhang, and Liu (2002) and in the following online source http://www.geri.duke.edu/china_study/index.htm.

Because our target population is older adults in general and 2002 was the first year when all older adults aged 65 and older were sampled, we used data from the 16,020 respondents in the 2002 sample. To have a more clearly defined sample representation (i.e., older Chinese adults aged 65 and older in 2002) and because one of our outcomes was mortality risk over a 6-year period, we did not include the respondents who were added in 2005 to replace those who were deceased between 2002 and 2005. Our analysis also excluded 222 respondents aged over 105 in 2002 because previous research showed that age reporting of the Chinese older adults was generally reliable up to the age of 105 (Zeng et al., 2002). Further excluding 1,593 respondents who were “not able to answer” the question on loneliness and additional 133 respondents who were missing on sociodemographic and behavioral and health variables in the 2002 interview, our analytical sample included 14,072 respondents. Among them, 7,668 were reinterviewed in 2005, 4,603 died between 2002 and 2005, and 1,801 were lost to follow-up. In 2008, 4,033 were reinterviewed, 2,245 died between 2005 and 2008, and additional 1,390 were lost to follow-up. In our analysis, the respondents who were lost to follow-up were not deleted but were treated as being censored. Bivariate correlation analysis showed that the respondents with higher levels of loneliness and poorer physical and emotional health were more likely to drop out and those who were older, women, Han, living in urban areas, living in a nursing home, and having fewer children living nearby or visiting were also more likely to drop out.

Measures

Loneliness.

Loneliness was measured in 2002, 2005, and 2008 with a single question asking how often the respondent feels lonely and isolated. The 5-point response scale ranged from “never” to “always.” Although there have been some concerns that self-report of an undesirable emotional state with a single item may lead to underestimates of the true prevalence of loneliness, this single-question measure has been widely used (e.g., Nummela et al., 2011; Patterson & Veenstra, 2010; Savikko et al., 2005; Shiovitz-Ezra & Ayalon, 2010; Theeke, 2009; Yang & Victor, 2008, 2011) and has been reported to have good face and predictive validity (Tilvis, Jolkkonen, Pitkala, & Strandberg, 2000). In addition, this single-question measure was the original standard against which multi-item instruments were validated and it has been shown to be highly correlated with the two most widely used loneliness assessment tools, the UCLA Loneliness Scale (Russell, 1996) and the de Jong Gierveld Loneliness Scale (de Jong Gierveld & van Tilburg, 1999). A study that compared this approach to the scales that indirectly asked about perceived social isolation via questions relating to social networks and the availability of confiding relationships found that the two approaches gave similar estimates of the prevalence of “severe” levels of perceived social isolation, but they were inconsistent in estimating the prevalence of “intermediate” categories of loneliness (Victor, Grenade, & Boldy, 2005). Furthermore, as noted by Bell and Gonzalez (1988), those measures that rely on indirect items, which assess the lack of support that may lead to loneliness, might be confounded with social support itself. Because the question on loneliness in CLHLS is highly skewed with fewer respondents in the “always” and “often” categories, we also experimented with a dichotomous scale that combined “sometimes,” “often,” and “always” into one category and “seldom” and “never” into another category. This analysis produced generally similar results to those using the 5-point scale.

Mortality.

The dates of death for the period 2002–2008 for deceased respondents were collected from various sources including death certificates, next of kin, and neighborhood committees. All dates were validated, and the dates reported on death certificates were used when available; otherwise the next of kin’s report was used, followed by neighborhood registries (Gu & Dupre, 2008). We created a mortality status indicator for each of the follow-up surveys, which was coded 1 if the respondent died in a specific time period, 0 if the respondent is still alive, and a missing value flag if the respondent died during a preceding time period or has dropped out of the study.

Health outcomes.

Emotional health, self-rated health, and functional limitations were assessed in 2002, 2005, and 2008. (a) Emotional health. CLHLS asked several questions on affective experiences and these items have been used to create indexes on emotional well-being among older Chinese adults in earlier studies (Chen & Short, 2008; Ross & Zhang, 2008). Two items tap positive affect: “Do you always look on the bright side of things?” and “Are you as happy as when you were young?” and two items tap negative affect: “Do you often feel fearful or anxious?” and “Do you feel the older you get, the more useless?” The 5-point response scale to each item ranged from “never” to “always.” With the two items tapping negative affect reverse coded, the index was derived by averaging scores on these items. It ranges from 0 to 4 with higher values associated with better emotional health and Cronbach’s alpha ranges from .57 to .60 for the three waves. The relatively low reliability scores compared with the more established measures in the literature may reflect the smaller number of items used to construct the index (Chen & Short, 2008). Factor analysis showed that the four items load on a single factor with all loadings greater than 0.6. Combining these four items allows us to capture emotional well-being versus distress as a continuum with high levels of well-being on one end and high levels of distress on the other (Ross & Zhang, 2008). (b) Self-rated health was based on the question asking respondents to rate their current health on a 5-point scale ranging from “very bad” to “very good.” (c) Functional limitations. During the medical examination, respondents were asked to perform several moves, including (i) putting hand behind neck, (ii) putting hand behind lower back, (iii) raising arms upright, (iv) standing up from sitting in a chair, and (v) picking up a book from the floor. The number of functional limitations is a count of the number of these movements the respondent could not make; it ranges from 0 (no limitations) to 5 (5 limitations).

Behavioral covariates.

These include social activity participation, solitary leisure activity participation, physical exercise, and smoking and were assessed in each wave. (a) Social activity participation. Respondents were asked how often they participated in different types of activities with the 5-point response scale ranging from “never” to “almost every day.” The level of social activity participation is the average of responses to two items: (i) playing cards and/or mah-jong and (ii) organized social activities. (b) Solitary leisure activity participation. The level of solitary leisure activity participation is the average of responses to three activity items: (i) gardening (including both indoor and outdoor gardening), (ii) reading newspaper/books, and (iii) watching TV and/or listening to radio. The score for each activity type ranges from 0 to 4 with higher values indicating more frequent participation. Because reading is not applicable to illiterate elders, we controlled for education in all multivariate analyses (Ross & Zhang, 2008). Additional analyses using an index without reading showed similar results (available from the author). (c) Physical exercise. Respondents were asked whether they regularly participate in physical exercise and an affirmative answer to this question was coded 1. (d) Smoking status was based on answers to the questions whether the respondent currently smokes and whether they smoked in the past. These questions were recoded into three categories: never smoked, past smoker, and current smoker. We also created a dichotomous measure to indicate whether the respondent ever smoked.

Sociodemographic covariates.

Sociodemographic characteristics represent contextual factors that are related to loneliness, health behaviors, health, and mortality (Chen et al., 2013; de Jong Gierveld & van Tilburg, 1999; Hawkley et al., 2008; Liu & Ni, 2003; Pinquart & Sorenson, 2003; Savikko et al., 2005; Theeke, 2009; Victor, Scambler, Bowling, & Bond, 2005; Wang et al., 2011; Wu et al., 2010; Yang & Victor, 2008). The observed relationship between loneliness and behavioral and health outcomes may be spurious if these characteristics are not controlled for. In multivariate models, we control for age, gender, ethnicity (Han vs. non-Han), residence (urban vs. rural), education (some schooling vs. no schooling), financial independence, relative economic status, living arrangement, number of children nearby, and number of visiting children measured in 2002. Financial independence was coded 1 if the respondent relies on retirement wage, spouse, or own employment as the primary means of financial support. Relative economic status was measured with the question: “How do you rate your economic status compared with others in your local area?” The 5-point response scale ranges from “very poor” to “very rich.” Living arrangement was based on marital status and the listing of household members. It has five categories: married living with spouse only, married living with spouse and others (most often children), unmarried living alone, unmarried living with others (most often children), and living in a nursing home. Number of children nearby is a count of non-resident children living in the same village or neighborhood. Number of visiting children is a count of non-resident children who often visit.

Statistical Procedures

Descriptive statistics were weighted by the sampling weight, which was calculated based on the age–sex–urban/rural residence-specific distribution of the population. Given that the CLHLS is specially designed by considering the clusters of age–sex–urban/rural residence, the weighted descriptive distributions can be generalized to the elderly population in China (Zeng et al., 2002). The multivariate analyses were not weighted as research has shown that including variables related to sample selection in the regression produces unbiased coefficients without weights (Winship & Radbill, 1994).

To test the relationship between loneliness, social and health behaviors, health outcomes, and mortality, we estimated a series of models that combined cross-lagged panel analysis with survival analysis using Mplus Version 7 (Muthén & Muthén, 1998–2012). Time to death was assessed by a discrete time survival analysis, which models the hazard probability of dying in a specific time interval, given that it has not happened yet. Two dichotomous variables indicating whether the respondent died between 2002 and 2005 and between 2005 and 2008 were included in these models. Cross-lagged path analysis examines the relationships between loneliness and behavioral and health variables. Cross-lagged path analysis is widely used to infer causal associations in data from longitudinal research designs. By estimating autoregressive and cross-lagged paths, this approach allows us to simultaneously address the reciprocal relationship between loneliness and behavioral and health variables (Curran, 2000). The combined model of survival analysis and cross-lagged path analysis allows us to estimate the effects of loneliness and behavioral and health variables on mortality once the cross-lagged relationship between loneliness and the behavioral and health variables is taken into account (de Leeuw et al., 2011). Because our models include categorical variables and censored data, parameters in the models were estimated using weighted least squares with robust standard errors and mean- and variance-adjusted chi-square test statistic and the coefficients for mortality are Probit regression coefficients (Muthén & Muthén, 1998–2012). The Probit regression model expresses the probability of mortality given a set of risk factors as P(Y = 1) = F(−t + Σb i × X i), where F is the standard normal distribution function, t is the Probit threshold, and b is the Probit regression slope.

Missing data were not imputed; rather, available data from all 14,072 respondents were used in analyses. Full Information Maximum Likelihood (FIML) estimation was used to handle missing data (Muthén & Muthén, 1998–2012). The FIML method uses all information of the observed data, including mean and variance for the missing portions of a variable, given the observed portion(s) of other variables. FIML produces consistent and efficient estimates when the data are “missing at random” (MAR) and produces less biased estimates than other methods when the data deviate from MAR (Wothke, 1998). The degree of model fit was assessed with the chi-square goodness of fit statistic and the root-mean-square error of approximation (RMSEA). A model with an RMSEA of 0.05 or less is characterized as having a good fit and 0.10 or more as having a poor fit (Hu & Bentler, 1999; MacCallum, Browne, & Sugawara, 1996).

We first assessed a model with only loneliness and mortality. Then, separate models were estimated for loneliness and each behavioral and health variable. This allows us to see how much of the loneliness–mortality relationship can be explained by each of these behavioral and health variables. The models for behavioral outcomes include sociodemographic characteristics, whereas the models for health outcomes also include behavioral variables as covariates. In the final model, we included loneliness and all behavioral and health variables with each having an effect on mortality and having a cross-lagged relationship with other behavioral and health variables. This model allows us to assess the independent effects of each variable net of other behavioral and health variables. The theoretical models assume that prospective relationships between variables are stable over time. These assumptions were modeled by applying equality constraints to the autoregressive and cross-lagged paths, thereby imposing “stationarity” on the relationships among variables in the model. It is also assumed that the 3-year prospective effects of covariates on mortality, loneliness, and behavioral and health variables did not differ from one time point to another. Therefore, equality constraints were applied to each of these covariates over the two 3-year intervals (Cacioppo et al., 2010). Additional analyses showed that the models without equality constraints did not significantly improve model fit for five out of the eight models estimated. Although the unconstrained model fit the data better for solitary leisure activity participation, emotional health, and self-rated health, the results on the relationships between loneliness and these variables and their effects on mortality were similar to those from constrained models; thus, we present results from the constrained models for these outcomes for consistency with other outcomes. Correlations between variables and residuals at a given time were also estimated.

Results

Descriptive Statistics

Weighted descriptive statistics are presented in Table 1. On a scale from 0 to 4, the average level of loneliness was 0.95 in 2002. The majority of older adults seldom (32%) or never (41%) felt lonely, but 21% sometimes, 5% often, and 2% always felt lonely (not shown in table). In additional t tests of changes in behavioral and health outcomes over time among those who were reinterviewed both in 2005 and 2008 (results not shown in table), the average level of loneliness significantly increased (p < .01) from 2002 to 2008. We observed decreases in levels of social activity participation (p < .001), solitary leisure activity participation (p < .001), and the proportion of current smokers (p < .001), which mainly occurred between 2005 and 2008 as only the declines between 2005 and 2008 are statistically significant. The proportion of older adults reporting physical exercise did not change. Emotional health and self-rated health showed steady declines from 2002 to 2008 (p < .001), whereas the number of functional limitations steadily increased (p < .001), as both changes from 2002 to 2005 and from 2005 to 2008 are statistically significant for these three health outcomes.

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics

| Variables | 2002 | 2005 | 2008 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (%) | SD | Mean (%) | SD | N | Mean (%) | SD | N | |

| Loneliness (0–4) | 0.95 | 0.98 | 0.98 | 1.02 | 7,082 | 1.00 | 1.02 | 3,707 |

| Social activities (0–4) | 0.57 | 0.88 | 0.54 | 0.86 | 7,667 | 0.47 | 0.84 | 4,033 |

| Solitary leisure activities (0–4) | 1.51 | 1.11 | 1.45 | 1.08 | 7,667 | 1.36 | 1.00 | 4,033 |

| Physical exercise | 37.2 | 37.4 | 7,668 | 36.6 | 4,033 | |||

| Never smoked | 60.8 | 56.4 | 7,668 | 56.4 | 4,033 | |||

| Past smoker | 13.4 | 17.9 | 21.9 | |||||

| Current smoker | 25.7 | 25.7 | 21.6 | |||||

| Emotional health (0–4) | 2.66 | 0.71 | 2.60 | 0.72 | 7,238 | 2.47 | 0.66 | 3,789 |

| Self-rated health (0–4) | 2.46 | 0.91 | 2.40 | 0.94 | 7,230 | 2.40 | 0.95 | 3,784 |

| Functional difficulties (0–5) | 0.10 | 0.46 | 0.16 | 0.64 | 7,668 | 0.18 | 0.70 | 4,033 |

| Age (65–105) | 72.34 | 5.94 | ||||||

| Female | 52.9 | |||||||

| Ethnic Han | 94.2 | |||||||

| Urban | 35.2 | |||||||

| Some education | 49.0 | |||||||

| Financial independence | 48.8 | |||||||

| Relative economic status (0–5) | 2.01 | 0.65 | ||||||

| Married living only with spouse | 31.6 | |||||||

| Married living with others | 25.3 | |||||||

| Unmarried living alone | 12.6 | |||||||

| Unmarried living with others | 28.3 | |||||||

| Living in a nursing home | 2.3 | |||||||

| Number of children nearby (0–9) | 1.28 | 1.58 | ||||||

| Number of children visiting (0–11) | 3.10 | 1.94 | ||||||

Note. N = 14,072 in year 2002. Results are weighted.

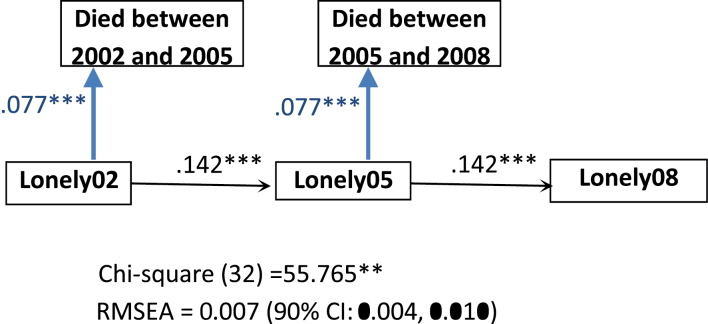

Loneliness and Mortality

Among the 14,072 older adults, 4,603, or 33% (12% if weighted), died between 2002 and 2005, and 2,245, 16% (10% if weighted), died between 2005 and 2008. Results from the combined models of survival analysis and cross-lagged path analysis are presented in Figures 1–3. The first model assesses the relationship between loneliness and mortality net of sociodemographic covariates (Figure 1). The results support stationary processes and fit the data well. The RMSEA is 0.007 (90% confidence interval [CI] = 0.004, 0.010). Net of sociodemographic covariates, loneliness at Time 1 is associated with increased mortality risk in a 3-year period (B = 0.077, p < .001). Most of the covariates are associated with mortality in the expected ways (not shown; available from author). Those who are older, men, ethnic Han, financially dependent on others, and reporting lower economic status than others are more likely to die in the 3-year period than those who are younger, women, non-Han, financially independent, and reporting higher economic status than others. Among different living arrangements, older adults living in nursing homes had the highest mortality risk, followed by the unmarried living with others and the married living with others, and the unmarried living alone and the married living only with the spouse have the lowest mortality risk. The number of children living nearby and the number of children often visiting do not have significant effects on mortality. Based on these results, for a Han ethnic urban female adult aged 85 with some education, financially independent, perceiving similar economic status as others, unmarried living with children, having one child living nearby, and two children often visit, the probability of dying between 2002 and 2005 is 36% if she never feels lonely, but it would be 48% if she always feels lonely.

Figure 1.

Model of loneliness and mortality net of sociodemographic covariates (age, gender, ethnicity, urban residence, education, financial independence, relative economic status, marital status, number of children visiting, and number of children living nearby). Results on sociodemographic covariates are not shown. The estimates are unstandardized coefficients. **p < .01, ***p < .001; two-tailed tests.

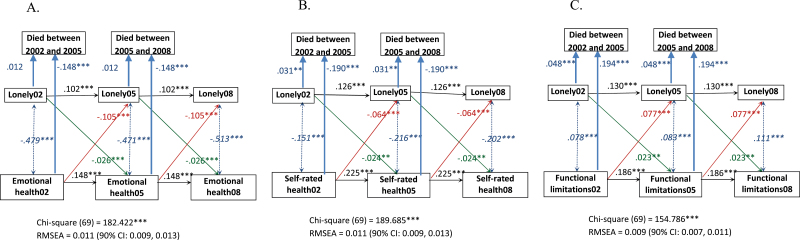

Figure 3.

Cross-lagged relationship between loneliness and health net of sociodemographic covariates (age, gender, ethnicity, urban residence, education, financial independence, relative economic status, marital status, number of children visiting, and number of children living nearby) and social and health behaviors (social activities, solitary leisure activities, physical exercise, and smoking). Results in sociodemographic covariates and social and health behaviors are not shown. Italicized estimates are standardized covariances (i.e., correlations) and the remaining estimates are unstandardized coefficients. **p < .01, ***p < .001; two-tailed tests. (A) Emotional health. (B) Self-rated health. (C) Functional limitations.

The 3-year change in loneliness is significantly associated with several demographic covariates (not shown; available from author). Holding constant the Time 1 level of loneliness and other covariates, levels of loneliness 3 years later are higher for those who are older, women, non-Han ethnic, living in rural areas, financially dependent on others, and having relatively lower economic status compared with others. Living arrangements also affect changes in loneliness. The increase in loneliness is highest among older adults who are living alone, followed by those in nursing homes, and then by those who are unmarried and living with their children; they are all significantly higher compared with those living with only a spouse. Those living with a spouse and children, however, have marginally significantly lower levels of loneliness than those living with only a spouse. In addition, the number of children often visiting is negatively associated with levels of loneliness.

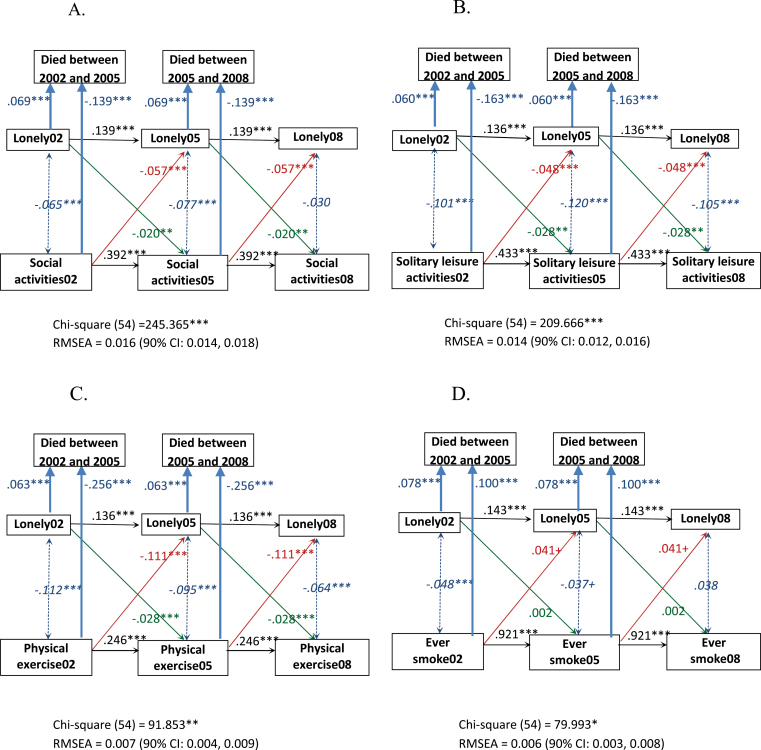

Loneliness, Social and Health Behaviors, and Mortality

Figure 2 presents results from the combined models of mortality and cross-lagged relationship between loneliness and social and health behaviors net of sociodemographic covariates. The results support stationary processes and in each case fit the data well. The RMSEA is 0.016 (90% CI = 0.014, 0.018) for social activity participation, 0.014 (90% CI = 0.012, 0.016) for solitary leisure activity participation, 0.007 (90% CI = 0.004, 0.009) for physical exercise, and 0.006 (90% CI = 0.003, 0.008) for smoking. In the model for social activity participation, net of sociodemographic characteristics, the effect of loneliness on 3-year mortality risk is slightly attenuated compared with the model without social activities (B = 0.069), but it is significant and levels of social activity participation have a significant negative effect on 3-year mortality risk. Both the 3-year lagged effect of loneliness on social activity participation and the 3-year lagged effect of social activity participation on loneliness are significant, which points to a reciprocal relationship between loneliness and social activity participation. Similar relationships were also found in the models for solitary leisure activity participation and physical exercise. For solitary leisure activity participation, net of sociodemographic characteristics, the effect of loneliness on 3-year mortality risk is significant and is also just slightly smaller than the effect in Figure 1 (B = 0.060), and levels of solitary leisure activity participation have a significant negative effect on 3-year mortality risk. Both the 3-year lagged effect of loneliness on solitary leisure activity participation and the 3-year lagged effect of solitary leisure activity participation on loneliness are negative and significant.

Figure 2.

Model of mortality and cross-lagged relationship between loneliness and social and health behaviors net of sociodemographic covariates (age, gender, ethnicity, urban residence, education, financial independence, relative economic status, marital status, number of children visiting, and number of children living nearby). Results on sociodemographic covariates are not shown. Italicized estimates are standardized covariances (i.e., correlations) and the remaining estimates are unstandardized coefficients. +p < .1, *p < .05, **p < .01, ***p < .001; two-tailed tests. (A) Social activities. (B) Solitary leisure activities. (C) Physical exercise. (D) Smoking.

For physical exercise, the effect of loneliness on 3-year mortality risk is slightly smaller than in Figure 1 but is significant (B = 0.063) and participation of physical exercise has a significant negative effect on 3-year mortality risk. Both the 3-year lagged effect of loneliness on physical exercise and the 3-year lagged effect of physical exercise on loneliness are negative and significant. In the model for smoking, we modeled ever smoking because it better captures smoking history than current smoking and has stronger health effects. Both loneliness and ever smoking have significant positive effects on 3-year mortality, but the size of the effect of loneliness on 3-year mortality does not change from the one in Figure 1. In addition, no reciprocal relationship between loneliness and smoking was observed; we saw a marginally significant and positive effect of ever smoking on changes in loneliness over a 3-year period, but the effect of loneliness on smoking is not significant. In order to capture current smoking status, which may be more subject to change, this model (Figure 2D) was rerun using current smoking status and neither the effect of loneliness on changes in smoking nor the effect of smoking on changes in loneliness was significant (not shown).

Loneliness, Health, and Mortality

The relationships between loneliness, health, and mortality while controlling for sociodemographic and behavioral covariates were examined next and the results are shown in Figure 3. The results support the stationary processes and these models fit the data well. The RMSEA is 0.011 (90% CI = 0.009, 0.013) for emotional health, 0.011 (90% CI = 0.009, 0.013) for self-rated health, and 0.009 (90% CI = 0.007, 0.011) for functional limitations. In the model for emotional health, once the reciprocal relationship between loneliness and emotional health is taken into account, the direct effect of loneliness on 3-year mortality risk substantially decreases (B = 0.012) and is no longer statistically significant. Emotional health, however, has a strong negative and significant effect on 3-year mortality risk. We see a reciprocal relationship between loneliness and emotional health. Both the 3-year lagged effect of loneliness on emotional health and the 3-year lagged effect of emotional health on loneliness are negative and significant.

In the model for self-rated health, once the reciprocal relationship between loneliness and self-rated health is taken into account, the direct effect of loneliness on 3-year mortality risk is cut in half (B = 0.031) but remains statistically significant. Self-rated health also has a strong and significant negative effect on 3-year mortality risk. Both the 3-year lagged effect of loneliness on self-rated health and the 3-year lagged effect of self-rated health on loneliness are negative and significant. In the model for functional limitations, once the reciprocal relationship between loneliness and functional limitations is taken into account, the direct effect of loneliness on 3-year mortality risk decreases (B = 0.048), but it remains statistically significant. Functional limitations have a strong positive effect on 3-year mortality risk. Both the 3-year lagged effect of loneliness on functional limitations and the 3-year lagged effect of functional limitations on loneliness are positive and significant.

The final model that includes all seven behavioral and health variables and the cross-lagged paths between each pair of these variables fits the data well (results not shown). The RMSEA is 0.012 (90% CI = 0.011, 0.013). Net of sociodemographic and other behavioral and health variables, the direct effect of loneliness on 3-year mortality risk is no longer statistically significant. The 3-year lagged effects of loneliness on physical exercise (B = −0.013) and emotional health (B = −0.024) are significant. The 3-year lagged effects of emotional health, self-rated physical health, social activity participation, and exercise on loneliness are negative and remain significant, whereas the 3-year lagged effects of functional limitations and ever smoking on loneliness are positive and remain significant. These results suggest that social and health behaviors and health outcomes explain the observed relationship between loneliness and later mortality.

Discussion

A growing literature based on Western countries indicated that loneliness is associated with many physiological, biological, and behavioral problems in middle-aged and older adults. This study extended this research to examine the prevalence of loneliness and its health consequences for older adults in a non-Western country, China, which has been experiencing tremendous social and economic transformations in the last several decades. The results showed that among older Chinese people, 28% reported feeling lonely and nearly 7% reported often or always feeling lonely. These numbers are similar to a report by Yang and Victor (2008) and compatible to those reported in Western countries (de Jong Gierveld & van Tilburg, 1999; Theeke, 2009). However, the causes underlying loneliness in Chinese older adults may differ from those in Western countries. In China, the social changes that may have led to loneliness include the breakdown of the traditional family support system brought about by social, economic, and demographic changes. These may have taken a psychological toll on older people in a collective culture that values interdependence, mutual support, and common goals (Wu et al., 2010; Yang & Victor, 2008).

The hypothesis that loneliness is associated with increased mortality risk is supported by the data. Consistent with previous research in Western countries (Luo et al., 2012; Patterson & Veenstra, 2010; Shiovitz-Ezra & Ayalon, 2010), we found that after taking into account sociodemographics and social relationships, elderly Chinese with higher levels of loneliness tend to die earlier than those with lower levels of loneliness. Also consistent with previous research, behavioral and health outcomes at least partially mediate the effect of loneliness on mortality among older Chinese adults as we see attenuations of the direct effect of loneliness on mortality once behavioral and health variables were added. In general, the similarities found in our analysis of China and in previous studies in Western countries suggest that the prevalence of loneliness among the elderly Chinese is on a par with their Western counterparts and that the causal links between loneliness, health, and mortality are also similar. For example, Patterson and Veenstra (2010), using data from the Alameda County Study, found that the relationship between loneliness and mortality was largely explained by health behaviors and depression. Using data from the Health and Retirement Study, Shiovitz-Ezra and Ayalon (2010) found that the effect of loneliness on mortality substantially decreased after controlling for medical status, functional impairment, and depression among older U.S. adults. Also using data from this survey, Luo and colleagues (2012) showed that the relationship between loneliness and mortality over 6 years was not explained by social relationships or health behaviors but was modestly explained by health outcomes.

The findings from cross-lagged path analyses lend further support for the plausible mediating role of behavioral and health outcomes in the effect of loneliness on mortality. Loneliness has cross-lagged effects on social activity participation, solitary leisure activity participation, and physical exercise even when the cross-lagged effects of these activities on loneliness are taken into account. Although the effects of loneliness on social activity participation and physical exercise have been found in previous studies in Western countries (Hawkley et al., 2008, 2009), among Chinese older adults, loneliness also reduces participation in solitary leisure activities. It is possible that the negative effect associated with loneliness inhibits individuals not only from social interactions but also from any leisure pursuit.

The Chinese data, however, did not show a reciprocal relationship between loneliness and smoking. Older adults who ever smoked had a marginally significant increase in loneliness over a 3-year period, but the effect of loneliness on changes in smoking was not significant. China is ranked among the top 20 countries in cigarette smoking rate worldwide; it is estimated that about 30%–35% of Chinese people smoke regularly and this rate has not changed much over time (Li, Hsia, & Yang, 2011; Yang et al., 1999). Smoking is often seen as a status symbol for Chinese men and cigarettes are often used as gifts and exchanged in social settings. What we see from the CLHLS data suggests that smoking is not a cure for loneliness and it substantially increases mortality risk in old age. Future research needs to examine attitudes toward smoking to gain a better understanding of the nature of loneliness–smoking relationship in China. This understanding could help public health programs develop strategies to reduce smoking.

The findings on the cross-lagged effects of loneliness on emotional health, self-rated health, and functional limitations after its effects on behavioral covariates and a reciprocal effect of these health variables on loneliness were taken into account are consistent with what was found in the U.S. older adults (Luo et al., 2012). Although the effects of health measures on 3-year changes in loneliness are generally larger than the effects of loneliness on 3-year changes in health outcomes, the effects of loneliness on all three health outcomes remain sizable and statistically significant after adjusting for the effects of these health variables on loneliness. This finding suggests a bidirectional loneliness–health relationship: poor health leads to feeling of loneliness and feeling lonely can further exacerbate health declines. In practice, this means that efforts to improve health and well-being among older adults not only must address the consequences of illness and disease but must also attend to older adults’ social connections and how they feel about them.

Several limitations of this study warrant further investigation in future research. First, as we mentioned earlier, the loneliness measure was based on self-report through in-person interviews and thus its prevalence may be underestimated because of the undesirable nature of this emotional state. In addition, despite its wide use in the literature and its high correlations with several established multiple-item scales, loneliness measured with a single question may still be less valid and reliable than a composite measure that taps multiple dimensions of perceived social isolation (Shiovitz-Ezra & Ayalon, 2012; Victor, Grenade, et al., 2005). Studies comparing single-item with multiple-item loneliness measures are particularly needed for non-Western societies because how these questions are interpreted and answered could be influenced by cultural background. Second, recent research suggests that chronic loneliness or fluctuating feelings of loneliness may be more strongly associated with mortality risk (Patterson & Veenstra, 2010; Shiovitz-Ezra & Ayalon, 2010). Because chronic loneliness was calculated using a respondent’s answers to the loneliness question at multiple time points, using this approach to study the effect of chronic loneliness would need to be limited to the respondents who were interviewed in both 2002 and 2005, and the results may be biased because about half of the older adults in the CLHLS survey died between 2002 and 2005 and those who died had higher levels of loneliness and poorer health than the respondents who stayed in the survey. Third, we used a “died-didn’t die” dichotomy at the two follow-up surveys for survival analysis so that we could estimate the models combining survival analysis and cross-lagged panel analysis in Mplus. Future research using a time sensitive model for survival analysis (e.g., measuring surviving months) may provide more accurate and robust findings.

In addition, the insignificance of the direct effect of loneliness on 3-year mortality risk after emotional health was added (Figure 3A) might be related to the high correlation between loneliness and emotional health (r = −.50 to −.55 for the three waves). Although previous literature suggests that loneliness is conceptually related to but distinct from other indicators of subjective well-being, such as depression (Cacioppo et al., 2006), it is possible that loneliness and poor emotional health as we measured here share some common roots (e.g., sadness). Future research that uses improved measures of loneliness and emotional health and also measures other personality traits may shed more light on the unique contribution of loneliness and poor emotional health to mortality.

Our study demonstrates that loneliness has similar health effects and these effects operate through similar mechanisms in older Chinese adults as in their Western counterparts. This issue warrants greater attention given rapid population aging and the growing number of empty-nest households in China. Because loneliness is part of a constellation of poor social, emotional, and health outcomes for Chinese older adults, interventions to increase the social involvement of lonely individuals may improve well-being and lengthen life.

Funding

This research is partially supported by grant R37 AG030481 from the National Institute on Aging and Clemson University Summer Research Grant.

Acknowledgments

We thank Rebecca N. H. de Leeuw for her assistance on data analysis. Y. Luo originated the research question. Both authors take responsibility for the integrity of the data, the accuracy of the data analysis, and interpretation of the findings.

References

- Ariyo A. A., Haan M., Tangen C. M., Rutledge J. C., Cushman M., Dobs A., Furberg C. D. (2000). Depressive symptoms and risks of coronary heart disease and mortality in elderly Americans. Circulation, 102, 1773–1779. 10.1161/01.CIR.102.15.1773 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell R. A., Gonzalez M. C. (1988). Loneliness, negative life events, and the provisions of social relationships. Communication Quarterly, 36, 1–15. 10.1080/01463378809369703 [Google Scholar]

- Cacioppo J. T., Hawkley L. C. (2009). Perceived social isolation and cognition. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 13, 447–454. 10.1016/j.tics.2009.06.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cacioppo J. T., Hawkley L. C., Crawford L. E., Ernst J. M., Burleson M. H., Kowalewski R. B, … Berntson G. G. (2002). Loneliness and health: Potential mechanisms. Psychosomatic Medicine, 64, 407–417 Retrieved from http://www.psychosomaticmedicine.org/ [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cacioppo J. T., Hawkley L. C., Thisted R. A. (2010). Perceived social isolation makes me sad: 5-Year cross-lagged analyses of loneliness and depressive symptomatology in the Chicago Health, Aging, and Social Relations Study. Psychology and Aging, 25, 453–463. 10.1037/a0017216 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cacioppo J. T., Hughes M. E., Waite L. J., Hawkley L. C., Thisted R. A. (2006). Loneliness as a specific risk factor for depressive symptoms: Cross-sectional and longitudinal analyses. Psychology and Aging, 21, 140–151. 10.1037/0882-7974.21.1.140 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen F., Short S. E. (2008). Household context and subjective well-being among the oldest old in China. Journal of Family Issues, 29, 1379–1403. 10.1177/0192513X07313602 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y., Hicks A., While A. E. (2013). Loneliness and social support of older people in China: A systematic literature review. Health & Social Care in the Community, 22, 113–123. 10.1111/hsc.12051 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen-Mansfield J., Shmotkin D., Goldberg S. (2009). Loneliness in old age: Longitudinal changes and their determinants in an Israeli sample. International Psychogeriatrics, 21, 1160–1170. 10.1017/S1041610206004200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curran P. J. (2000). A latent curve framework for the study of developmental trajectories in adolescent substance use. In Rose J. S., Chassin L., Presson C. C., Sherman S. J. (Eds.), Multivariate applications in substance use research: New methods for new questions (pp. 1–4). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates [Google Scholar]

- de Jong Gierveld J., van Tilburg T. (1999). Living arrangements of older adults in the Netherlands and Italy: Coresidence values and behaviour and their consequences for loneliness. Journal of Cross-Cultural Gerontology, 14, 1–24. 10.1023/A1006600825693 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Jong Gierveld J., van Tilburg T., Dykstra P. A. (2006). Loneliness and social isolation. In Vangelisti A., Perlman D. (Eds.), Cambridge handbook of personal relationships (pp. 485–500). Cambridge, MA: Cambridge University Press [Google Scholar]

- de Leeuw R. N., Sargent J. D., Stoolmiller M., Scholte R. H., Engels R. C., Tanski S. E. (2011). Association of smoking onset with R-rated movie restrictions and adolescent sensation seeking. Pediatrics, 127, e96–e105. 10.1542/peds.2009-3443 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeWall C. N., Pond R. S. (2011). Loneliness and smoking: The costs of the desire to reconnect. Self and Identity, 10, 375–385. 10.1080/15298868.2010.524404 [Google Scholar]

- Dupre M. E., Liu G., Gu D. (2008). Predictors of longevity: Evidence from the oldest old in China. American Journal of Public Health, 98, 1203–1208. 10.2105/AJPH.2007.113886 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Everard K. M., Lach H. W., Fisher E. B., Baum M. C. (2000). Relationship of activity and social support to the functional health of older adults. Journal of Gerontology: Social Sciences, 55B, S208–S212. 10.1093/geronb/55.4.S208 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Everson S. A., Roberts R. E., Goldberg D. E., Kaplan G. A. (1998). Depressive symptoms and increased risk of stroke mortality over a 29-year period. Archives of Internal Medicine, 158, 1133–1138. 10.1001/archinte.158.10.1133 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenfield E. A., Russell D. (2011). Identifying living arrangements that heighten risk for loneliness in later life. Journal of Applied Gerontology, 30, 524–534. 10.1177/0733464810364985 [Google Scholar]

- Gu D., Dupre M. E. (2008). Assessment of reliability of mortality and morbidity in the 1998–2002 CLHLS waves. In Zeng Y., Poston D., Vlosky D. A., Gu D. (Eds.), Healthy longevity in China: Demographic, socioeconomic, and psychological dimensions (pp. 99–115). Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Springer [Google Scholar]

- Hagerty B. M., Williams R. A. (1999). The effects of sense of belonging, social support, conflict, and loneliness on depression. Nursing Research, 48, 215–219. 10.1097/00006199-199907000-00004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hao Y. (2008). Productive activities and psychological well-being among older adults. Journal of Gerontology Social Sciences, 63, S64–S72. 10.1093/geronb/63.2.S64 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawkley L. C., Burleson M. H., Berntson G. G., Cacioppo J. T. (2003). Loneliness in everyday life: Cardiovascular activity, psychosocial context, and health behaviors. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 85, 105–120. 10.1037/0022-3514.85.1.105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawkley L. C., Cacioppo J. T. (2010). Loneliness matters: A theoretical and empirical review of consequences and mechanisms. Annals of Behavioral Medicine, 40, 218–227. 10.1007/s12160-010-9210-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawkley L. C., Hughes M. E., Waite L. J., Masi C. M., Thisted R. A., Cacioppo J. T. (2008). From social structural factors to perceptions of relationship quality and loneliness: The Chicago Health, Aging, and Social Relations Study. Journal of Gerontology Social Sciences, 63, S375–S384. 10.1093/geronb/63.6.S375 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawkley L. C., Thisted R. A., Cacioppo J. T. (2009). Loneliness predicts reduced physical activity: Cross-sectional and longitudinal analyses. Health Psychology, 28, 354–363. 10.1037/a0014400 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawkley L. C., Thisted R. A., Masi C. M., Cacioppo J. T. (2010). Loneliness predicts increased blood pressure: 5-Year cross-lagged analyses in middle-aged and older adults. Psychology and Aging, 25, 132–141. 10.1037/a0017805 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu L. T., Bentler P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling, 6, 1–55. 10.1080/10705519909540118 [Google Scholar]

- Idler E. L., Benyamini Y. (1997). Self-rated health and mortality: A review of twenty-seven community studies. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 38, 21–37. 10.2307/2955359 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jylhä M. (2004). Old age and loneliness: Cross-sectional and longitudinal analyses in the Tampere Longitudinal Study on Aging. Canadian Journal on Aging, 23, 157–168. 10.1353/cja.2004.0023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keysor J. J. (2003). Does late-life physical activity or exercise prevent or minimize disablement? A critical review of the scientific evidence. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 25, 129–136. 10.1016/S0749-3797(03)00176-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiecolt-Glaser J. K., Garner W., Speicher C., Penn G. M., Holliday J., Glaser R. (1984). Psychosocial modifiers of immunocompetence in medical students. Psychosomatic Medicine, 46, 7–14 Retrieved from http://www.psychosomaticmedicine.org/ [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lai Y. (2012). Research progress of elderly loneliness [in Chinese]. Chinese Journal of Gerontology, 32, 2429–2432. 10.3969/j.issn.1005-9202.2012.11.112 [Google Scholar]

- Lee Y., Park K. H. (2006). Health practices that predict recovery from functional limitations in older adults. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 31, 25–31. 10.1016/j.amepre.2006.03.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lennartsson C., Silverstein M. (2001). Does engagement with life enhance survival of elderly people in Sweden? The role of social and leisure activities. Journal of Gerontology Social Sciences, 56, S335–S342. 10.1093/geronb/56.6.S335 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Q., Hsia J., Yang G. (2011). Prevalence of smoking in China in 2010. New England Journal of Medicine, 364, 2469–2470. 10.1056/NEJMc1102459 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu G., Dupre M. E., Gu D., Mair C. A., Chen F. (2012). Psychological well-being of the institutionalized and community-residing oldest old in China: The role of children. Social Science & Medicine, 75, 1874–1882. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2012.07.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu L.-J., Guo Q. (2007). Loneliness and health-related quality of life for the empty nest elderly in the rural area of a mountainous county in China. Quality of Life Research, 16, 1275–1280. 10.1007/s11136-007-9250-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu X., Liang J., Gu S. (1995). Flows of social support and health status among older persons in China. Social Science & Medicine, 41, 1175–1184. 10.1016/0277-9536(94)00427-U [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Z. R., Ni J. F. (2003). Study on factors related to loneliness among elderly people [in Chinese]. Chinese Journal of Public Health, 19, 293–295. 10.11847/zgggws2003-19-03-20 [Google Scholar]

- Luo Y., Hawkley L. C., Waite L. J., Cacioppo J. T. (2012). Loneliness, health, and mortality in old age: A national longitudinal study. Social Science & Medicine, 74, 907–914. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.11.028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacCallum R. C., Browne M. W., Sugawara H. M. (1996). Power analysis and determination of sample size for covariance structure modeling. Psychological Methods, 1, 130–149. 10.1037/1082-989X.1.2.130 [Google Scholar]

- McAuley E., Blissmer B., Marquez D. X., Jerome G. J., Kramer A. F., Katula J. (2000). Social relations, physical activity, and well-being in older adults. Preventive Medicine, 31, 608–617. 10.1006/pmed.2000.0740 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menec V. H., Chipperfield J. G. (1997). Remaining active in later life. The role of locus of control in seniors’ leisure activity participation, health, and life satisfaction. Journal of Aging and Health, 9, 105–125. 10.1177/089826439700900106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén L. K., Muthén B. O. (1998–2012). Mplus user’s guide (7th ed.). Los Angeles, CA: Muthén and Muthén [Google Scholar]

- Nummela O., Seppänen M., Uutela A. (2011). The effect of loneliness and change in loneliness on self-rated health (SRH): A longitudinal study among aging people. Archives of Gerontology and Geriatrics, 53, 163–167. 10.1016/j.archger.2010.10.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okun M. A., August K. J., Rook K. S., Newsom J. T. (2010). Does volunteering moderate the relation between functional limitations and mortality? Social Science & Medicine, 71, 1662–1668. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.07.034 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan J. Y., Zhang M., Wang M., Zan P. X., Wei H. C., Ye D. Q., Huang F. (2010). Study on sleeping quality and loneliness among elderly people in rural area of Anhui province [in Chinese]. Chinese Journal of Disease Control & Prevention, 14, 335–337 Retrieved from http://www.zhjbkz.cn/ [Google Scholar]

- Patterson A. C., Veenstra G. (2010). Loneliness and risk of mortality: A longitudinal investigation in Alameda County, California. Social Science & Medicine, 71, 181–186. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.03.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Penninx B. W., van Tilburg T., Kriegsman D. M., Deeg D. J., Boeke A. J., van Eijk J. T. (1997). Effects of social support and personal coping resources on mortality in older age: The Longitudinal Aging Study Amsterdam. American Journal of Epidemiology, 146, 510–519 Retrieved from http://aje.oxfordjournals.org/ [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pettigrew S., Roberts M. (2008). Addressing loneliness in later life. Aging & Mental Health, 12, 302–309. 10.1080/13607860802121084 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinquart M., Sorenson S. (2003). Risk factors for loneliness in adulthood and old age: A meta-analysis. In Shohov S. P. (Ed.), Advances in psychology research (Vol. 19, pp. 111–143). Hauppauge, NY: Nova Science [Google Scholar]

- Pressman S. D., Cohen S., Miller G. E., Barkin A., Rabin B. S., Treanor J. J. (2005). Loneliness, social network size, and immune response to influenza vaccination in college freshmen. Health Psychology, 24, 297–306. 10.1037/0278-6133.24.3.297 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross C. E., Zhang W. (2008). Education and psychological distress among older Chinese. Journal of Aging and Health, 20, 273–289. 10.1177/0898264308315428 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell D. W. (1996). UCLA Loneliness Scale (Version 3): Reliability, validity, and factor structure. Journal of Personality Assessment, 66, 20–40. 10.1207/s15327752jpa6601_2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savikko N., Routasalo P., Tilvis R. S., Strandberg T. E., Pitkälä K. H. (2005). Predictors and subjective causes of loneliness in an aged population. Archives of Gerontology and Geriatrics, 41, 223–233. 10.1016/j.archger.2005.03.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Segrin C., Domschke T. (2011). Social support, loneliness, recuperative processes, and their direct and indirect effects on health. Health Communication, 26, 221–232. 10.1080/10410236.2010.546771 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shankar A., McMunn A., Banks J., Steptoe A. (2011). Loneliness, social isolation, and behavioral and biological health indicators in older adults. Health Psychology, 30, 377–385. 10.1037/a0022826 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiovitz-Ezra S., Ayalon L. (2010). Situational versus chronic loneliness as risk factors for all-cause mortality. International Psychogeriatrics, 22, 455–462. 10.1017/S1041610209991426 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiovitz-Ezra S., Ayalon L. (2012). Use of direct versus indirect approaches to measure loneliness in later life. Research on Aging, 34, 572–591. 10.1177/0164027511423258 [Google Scholar]

- Silverstein M., Parker M. G. (2002). Leisure activities and quality of life among the oldest old in Sweden. Research on Aging, 24, 528–547. 10.1177/0164027502245003 [Google Scholar]

- Stephens C., Alpass F., Towers A., Stevenson B. (2011). The effects of types of social networks, perceived social support, and loneliness on the health of older people. Journal of Aging and Health, 23, 887–911. 10.1177/0898264311400189 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun R., Liu Y. (2006). Mortality of the oldest old in China: The role of social and solitary customary activities. Journal of Aging and Health, 18, 37–55. 10.1177/0898264305281103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Theeke L. A. (2009). Predictors of loneliness in U.S. adults over age sixty-five. Archives of Psychiatric Nursing, 23, 387–396. 10.1016/j.apnu.2008.11.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tilvis R. S., Jolkkonen K. H., Pitkala J., Strandberg T. E. (2000). Social networks and dementia. The Lancet, 356, 77–78. 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)73414-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tilvis R. S., Kähönen-Väre M. H., Jolkkonen J., Valvanne J., Pitkälä K. H., Strandberg T. E. (2004). Predictors of cognitive decline and mortality of aged people over a 10-year period. Journal of Gerontology: Medical Sciences, 59, M268–M274. 10.1093/gerona/59.3.M268 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Victor C. R., Grenade L., Boldy D. (2005). Measuring loneliness in later life: A comparison of differing measures. Reviews in Clinical Gerontology, 15, 63–70. 10.1017/S0959259805001723 [Google Scholar]

- Victor C. R., Scambler S. J., Bowling A. N. N., Bond J. (2005). The prevalence of, and risk factors for, loneliness in later life: A survey of older people in Great Britain. Ageing & Society, 25, 357–375. 10.1017/S0144686X04003332 [Google Scholar]

- Wang G., Zhang X., Wang K., Li Y., Shen Q., Ge X., Hang W. (2011). Loneliness among the rural older people in Anhui, China: Prevalence and associated factors. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 26, 1162–1168. 10.1002/gps.2656 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Z., Shu D., Dong B., Luo L., Hao Q. (2013). Anxiety disorders and its risk factors among the Sichuan empty-nest older adults: A cross-sectional study. Archives of Gerontology and Geriatrics, 56, 298–302. 10.1016/j.archger.2012.08.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei M., Russell D. W., Zakalik R. A. (2005). Adult attachment, social self-efficacy, self-disclosure, loneliness, and subsequent depression for freshman college students: A longitudinal study. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 52, 602–614. 10.1037/0022-0167.52.4.602 [Google Scholar]

- Wilson R. S., Krueger K. R., Arnold S. E., Schneider J. A., Kelly J. F., Barnes L. L, … Bennett D. A. (2007). Loneliness and risk of Alzheimer disease. Archives of General Psychiatry, 64, 234–240. 10.1001/archpsyc.64.2.234 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winship C., Radbill L. (1994). Sampling weights and regression analysis. Sociological Methods & Research, 23, 230–257. 10.1177/0049124194023002004 [Google Scholar]

- Wothke W. (2000). Longitudinal and multi-group modeling with missing data. In Little T. D., Schnabel K. U., Baumert J. (Eds.), Modeling longitudinal and multiple group data: Practical issues, applied approaches and specific examples pp. 219–240. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Publishers [Google Scholar]

- Wu Z.-Q., Cui G.-H., Zhang X.-J., Sun L., Tao F.-B., Sun Y.-H. (2009). Status and its determinants of loneliness in empty nest elderly [in Chinese]. Chinese Journal of Public Health, 25, 960–962. 10.11847/zgggws2009-25-08-36 [Google Scholar]

- Wu Z.-Q., Guo Z.-P., Li M.-Z., Yang X.-T., Liu X.-F., Zhang X.-J., Sun L. (2011). Life satisfaction and its determinants in empty-nest elderly [in Chinese]. Chinese Journal of Public Health, 27, 821–823. 10.11847/zgggws2011-27-07-03 [Google Scholar]

- Wu Z. Q., Sun L., Sun Y. H., Zhang X. J., Tao F. B., Cui G. H. (2010). Correlation between loneliness and social relationship among empty nest elderly in Anhui rural area, China. Aging & Mental Health, 14, 108–112. 10.1080/13607860903228796 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang G., Fan L., Tan J., Qi G., Zhang Y., Samet J. M, … Xu J. (1999). Smoking in China. JAMA: The Journal of the American Medical Association, 282, 1247–1253. 10.1001/jama.282.13.1247 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang K., Victor C. (2008). The prevalence of and risk factors for loneliness among older people in China. Ageing & Society, 28, 305–327. 10.1017/S0144686X07006848 [Google Scholar]

- Yang K., Victor C. (2011). Age and loneliness in 25 European nations. Ageing & Society, 31, 1368–1388. 10.1017/S0144686X1000139X [Google Scholar]

- Yu E. S., Kean Y. M., Slymen D. J., Liu W. T., Zhang M., Katzman R. (1998). Self-perceived health and 5-year mortality risks among the elderly in Shanghai, China. American Journal of Epidemiology, 147, 880–890 Retrieved from http://aje.oxfordjournals.org/ [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeng Y., Vaupel J. W., Xiao Z. Y., Zhang C. Y., Liu Y. Z. (2002). Sociodemographic and health profiles of the oldest old in China. Population and Development Review, 28, 251–273. 10.1111/j.1728-4457.2002.00251.x [Google Scholar]

- Zeng Y., Wang Z. (2003). Dynamics of family and elderly living arrangements in China: New lessons learned from the 2000 Census. The China Review, 3, 95–119 Retrieved from http://www.chineseupress.com/the-china-review [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Q. F. (2004). Economic transition and new patterns of parent-adult child coresidence in urban China. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 66, 1231–1245. 10.1111/j.0022-2445.2004.00089.x [Google Scholar]