Abstract

Incarceration, particularly when recurrent, can significantly compromise the health of individuals living with HIV. Despite this, the occurrence of recidivism among individuals with HIV has been little examined, particularly among those leaving jail, who may be at especially high risk for return to the criminal justice system. We evaluated individual- and structural-level predictors of recidivism and time to re-incarceration in a cohort of 798 individuals with HIV leaving jail. Nearly a third of the sample experienced at least one re-incarceration event in the 6 months following jail release. Having ever been diagnosed with a major psychiatric disorder, prior homelessness, having longer lifetime incarceration history, having been charged with a violent offense for the index incarceration and not having health insurance in the 30 days following jail release were predictive of recidivism and associated with shorter time to re-incarceration. Health interventions for individuals with HIV who are involved in the criminal justice system should also target recidivism as a predisposing factor for poor health outcomes. The factors found to be associated with recidivism in this study may be potential targets for intervention and need to be further explored. Reducing criminal justice involvement should be a key component of efforts to promote more sustainable improvements in health and well-being among individuals living with HIV.

Keywords: HIV, Jail, Recidivism, Criminal justice populations

Introduction

The epidemics of incarceration and HIV are inextricably linked in the United States. An estimated one in six HIV-infected persons in the U.S. spend time in a jail or prison every year [1]. In a 6-year follow-up study of an HIV-infected cohort in an urban county jail, 73 % of individuals were re-incarcerated an average of 6.8 times over 552 days [2]. While recidivism has been widely studied in the criminal justice population, this phenomenon is still not well understood among individuals with HIV, particularly among those leaving jail, and has yet to be examined in a large cohort. Jail detainees undergo shorter incarcerations and may move more frequently between correctional facilities and home communities. As such, jail incarceration is destabilizing in ways that are distinct from longer-term prison incarceration [3–6]. Additionally, due to rapid turnover, jail detainees are often less likely than prisoners to access antiretroviral therapy, HIV care and other evidence-based interventions during confinement and be linked to care after release. The unique dynamics of jail incarceration, along with co-occurring substance use and psychiatric disorders, homelessness and poverty, may place individuals leaving jail at especially high risk for reincarceration [6–9].

Incarceration, particularly when recurrent, has been shown to contribute to social and economic instability, increase engagement in HIV risk behaviors [8, 10–13] and compromise medication adherence, retention in care and immunological and virological outcomes among individuals with HIV [3, 4, 9, 14–18]. Despite the significant impact of recidivism on health and health behaviors, few health interventions for individuals with HIV who are involved in the criminal justice system have addressed recidivism directly as a predisposing factor for poor health outcomes. Additionally, few interventions have achieved conclusive reductions in recidivism or have assessed this outcome [2]. Health interventions for this population have largely focused on directly modifying HIV risk behaviors or enhancing linkage to HIV treatment and care [2, 19–27]. Some have argued that to elicit more sustainable health outcomes, such interventions should also address risk for recidivism [2, 9, 28–30] and target modifiable individual and structural-level risk factors for recidivism.

However, risk characteristics for recidivism have yet to be well elucidated among individuals with HIV who are in the criminal justice system and are the focus of the present study. We examined individual and structural-level predictors of recidivism and time to re-incarceration in a large cohort of HIV-infected individuals leaving jail. The period following release from jail is often fraught with instability, it is thereby critical to understand the characteristics of those who are re-incarcerated during this early time of vulnerability and those who are not.

Methods

Study Sample

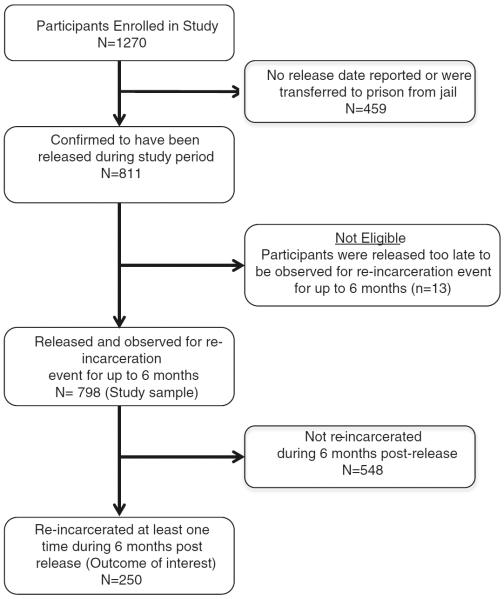

Analyses were based on data collected as a part of completed multi-site study, Enhancing linkages to HIV primary care and services in jail settings initiative (EnhanceLink). EnhanceLink is a study of health-related interventions for released HIV-infected jail detainees funded by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Health Resources and Services Administration. The study began in 2008 at ten demonstration sites across the country (CT, GA, IL, MA, NY, OH, PA [2 sites], SC, RI) and was designed to implement and evaluate innovative models of linkage to community-based primary care and other health and social services for HIV-infected individuals leaving jail. HIV-infected individuals who were 18 years or older and able to provide informed consent were eligible to participate in the survey-based evaluation. Recruitment procedures, eligibility criteria and distinct features of each site have been described previously [6], with all sites providing case management services along with other ancillary services. Between January 2008 and March 2011, 1,270 individuals were enrolled in the evaluation portion of the study and completed the baseline assessment. Based on our outcome of interest, re-incarceration up to 6 months post-release, we excluded (see Fig. 1) from analysis individuals without a reported release date from their index incarceration (n = 450, 35.4 % of total), those who were transferred from their index incarceration to prison (n = 9, 0.71 % of total) and individuals released too late to be observed for a re-incarceration event for up to 6 months (n = 13, 1 % of total), leaving a study sample of 798 individuals (62.8 % of total).

Fig. 1.

Subject disposition

Data Analysis

Dependent Variables

Our primary outcome of interest for the multivariate analysis, recidivism, was defined dichotomously as having any re-incarceration event within 6 months following release from jail. Re-incarceration was determined across all sites through a combination of client self-report, case manager follow-up with the client or correctional personnel, and confirmed assessment of correctional databases. Our outcome of interest for the survival analysis was time to reincarceration, defined as the number of days between first release from jail and first re-incarceration within the 6-month post-release observation period.

Independent Variables

Covariates of interest included socio-demographic and other factors associated with criminal justice involvement and recidivism that have been previously described. We examined relevant factors in three time periods: the time before the index jail incarceration, the time during the index incarceration, and the time following release from the index incarceration. All `pre-incarceration' variables pertain to the 30 days prior to the index jail incarceration, with the exception of one variable: employment status, which was defined as the client's employment pattern over the previous 3 years. All variables classified as `after release' pertain to the 30 days following release from the index jail incarceration, with the exception of housing status after release, which was defined as the client's housing status on the last day of the first 30 days following their release.

Health-related variables assessed include pre-incarceration drug and alcohol addiction severity and psychiatric illness severity, ever having been diagnosed with a major psychiatric illness (e.g. bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, major depression, post-traumatic stress syndrome), and HIV-related clinical outcomes (e.g. CD4 count and viral load) during the index incarceration. Key structural and institutional factors of interest included pre-incarceration homelessness and housing status after release, total lifetime incarceration, and having any health insurance or medical benefits pre-incarceration and after release. Service-related factors evaluated included completion of discharge planning prior to jail release, attending a drug treatment program after release (e.g. methadone maintenance treatment, in-patient drug treatment facility, out-patient drug treatment facility), and meeting with a community provider after release regarding health and social needs. Additional criminal justice factors were also assessed.

Pre-incarceration homelessness was defined as a composite of two variables—self-reporting homelessness or reporting sleeping in a shelter, park, empty building, bus station, on the street, or in another public place in the 30 days prior to incarceration. Post-release housing status was divided into three categories: homeless (e.g. living in an abandoned building, car, on the street or in a park, shelter or other emergency housing arrangement); temporary or transitional housing (e.g. in the home or apartment of friends or relatives where client did not pay rent; supported housing); and personal housing (e.g. in a home, apartment or room where client pays rent/mortgage, or own housing). Virologic suppression was defined as a plasma viral load of <400 copies/mL, and CD4 count and viral load during the index incarceration were calculated as an average of all test results reported during the index incarceration. Drug and alcohol use severity was assessed using the addiction severity index and calculated using previously validated cut-offs for alcohol and drug use [31, 32]. A psychiatric composite index was also compiled for each participant based on their answers to questions previously described in the addiction severity index composite score manual [31]. The variable `ever having been diagnosed with a major psychiatric disorder' was based on an assessment of the client's jail medical chart after release. This means that, at the very latest, clients were diagnosed with a major psychiatric disorder by the time of release from their index incarceration, but could have been diagnosed prior to the index incarceration.

Statistical Analysis

Analyses were stratified by the outcome of interest, re-incarceration in the 6 months following release, to assess for differences between the two comparison groups, re-incarcerated and not re-incarcerated. Univariate logistic regression analyses were performed between each independent variable and the dichotomous outcome variable. Three multivariate logistic regression models were created to reflect the different timeframes of the independent variables, with the first model assessing pre-incarceration predictors of subsequent re-incarceration, the second model assessing pre-release predictors of re-incarceration, and the third model assessing post-release predictors of re-incarceration. Independent variables significant at p < 0.05 at the univariate level were included in the multivariate models and each multivariate model was controlled for by race, ethnicity, gender, age and site. Independent variables with p < 0.05 in the multivariate model were considered to be statistically significant.

We also conducted survival analysis using univariate Cox proportional-hazards regression on predictors of time to re-incarceration, using independent variables that were significant in the multivariate logistic regression model. Independent variables with p < 0.05 were considered to be statistically significant in the univariate survival analysis.

Results

Table 1 describes participants' socio-demographic characteristics and predictors of re-incarceration in the 6 months following release at the univariate level. In the overall sample (n = 798), participants were mostly male, African American, and unemployed at the time of the index incarceration, with those who were subsequently re-incarcerated sharing this socio-demographic profile. Most individuals had spent <3 months in jail for their index incarceration and nearly a third of the sample (31.3 %) had at least one re-incarceration event in the 6 months following release, with the mean time to re-incarceration being 78 days (standard deviation 57). An estimated 26 % of all participants and 51 % of all re-incarcerated participants had been previously diagnosed with a major psychiatric disorder. With regard to HIV clinical outcomes, 46 % of all participants and 32 % of re-incarcerated participants reported viral loads during incarceration averaging to<400 copies/mL, the threshold for viral suppression. Interestingly, 79 % of individuals before the index incarceration, as opposed to 63 % of individuals after release from the index incarceration, reported having any health insurance or medical benefits. Site was significant at the univariate level but was not a significant predictor in the multivariate model (data not shown).

Table 1.

Sociodemographic characteristics and predictors of re-incarceration among recently released HIV-infected jail detainees (N = 798)

| Characteristic | Total sample | Re-incarcerated | Not re-incarcerated | Unadjusted odds ratio (95 % CI) | p- value | Adjusted odds ratio (95 % CI) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 798 | 250 | 548 | |||||

| Age | |||||||

| 20–38 years | 167 (21.1 %) | 42 (22.5 %) | 125 (20.7 %) | Referent | – | – | – |

| 39–44 years | 184 (23.3 %) | 50 (26.7 %) | 134 (22.2) | 1.11 (0.69, 1.79) | 0.67 | – | – |

| 45–49 years | 201 (25.4 %) | 49 (26.2 %) | 152 (25.2 %) | 0.96 (0.60, 1.54) | 0.86 | – | – |

| 50 years or older | 238 (30.1 %) | 46 (24.6) | 192 (31.8 %) | 0.71 (0.44, 1.15) | 0.16 | – | – |

| Gender | |||||||

| Female | 252 (31.7 %) | 51 (27.1 %) | 201 (33.2 %) | Referent | – | – | – |

| Male | 542 (68.3 %) | 137 (72.9 %) | 405 (66.8 %) | 1.33 (0.93, 1.92) | 0.12 | – | – |

| Ethnicity | |||||||

| Non-Hispanic | 568 (72.8 %) | 138 (75.0 %) | 430 (72.1 %) | Referent | – | – | – |

| Hispanic | 212 (27.2 %) | 46 (25.0 %) | 166 (27.9 %) | 0.86 (0.59, 1.26) | 0.45 | – | – |

| Race | |||||||

| White | 164 (20.8 %) | 38 (20.2 %) | 126 (21.0 %) | Referent | – | – | – |

| African American | 472 (60.0 %) | 118 (62.8 %) | 354 (59.1 %) | 1.11 (0.73, 1.68) | 0.64 | – | – |

| Other | 151 (19.2 %) | 32 (17.0 %) | 119 (19.9 %) | 0.89 (0.52, 1.52) | 0.67 | – | – |

| Sexual orientation | |||||||

| Heterosexual | 627 (80.0 %) | 145 (78.8 %) | 482 (80.3 %) | Referent | – | – | – |

| Bisexual | 77 (9.8 %) | 21 (11.4 %) | 56 (9.3 %) | 1.25 (0.73, 2.13) | 0.42 | – | – |

| Homosexual | 80 (10.2 %) | 18 (9.8 %) | 62 (10.3 %) | 0.97 (0.55, 1.68) | 0.90 | – | – |

| Education attained before index incarceration | |||||||

| Less than high school | 410 (51.4 %) | 95 (50.0 %) | 315 (51.9 %) | Referent | – | – | – |

| High school or higher | 387 (48.6 %) | 95 (50.0 %) | 292 (48.1 %) | 1.08 (0.78, 1.49) | 0.65 | – | – |

| Employment status before index incarceration | |||||||

| Unemployed | 513 (67.0 %) | 128 (70.7 %) | 385 (65.8 %) | Referent | – | – | – |

| Working full or part-time | 158 (20.6 %) | 31 (17.1 %) | 127 (21.7 %) | 0.75 (0.47, 1.14) | 0.17 | – | – |

| Retired/disabled | 95 (12.4 %) | 22 (12.2 %) | 73 (12.5 %) | 0.91 (0.54, 1.52) | 0.71 | – | – |

| Employment status after release | |||||||

| Unemployed | 459 (79.8 %) | 114 (79.7 %) | 345 (79.9 %) | Referent | – | – | – |

| Working full or part-time | 26 (4.5 %) | 4 (2.8 %) | 22 (5.1 %) | 0.55 (0.19, 1.63) | 0.28 | – | – |

| Retired/disabled | 90 (15.7 %) | 25 (17.5 %) | 65 (15.0 %) | 1.16 (0.70, 1.93) | 0.56 | – | – |

| Having any health insurance/medical benefits before index incarceration | |||||||

| No | 160 (20.2 %) | 40 (21.3 %) | 120 (19.9 %) | Referent | – | – | – |

| Yes | 632 (79.8 %) | 148 (78.7 %) | 484 (80.1 %) | 0.92 (0.61, 1.37) | 0.67 | – | – |

| Having any health insurance/medical benefits after release | |||||||

| No | 69 (12.1 %) | 28 (20.0 %) | 41 (9.5 %) | Referent | – | Referent | – |

| Yes | 502 (87.9 %) | 112 (80.0 %) | 390 (90.5 %) | 0.42 (0.25, 0.71) | <0.01 | 0.34 (0.13, 0.86) | <0.05 |

| Homeless before index incarceration | |||||||

| No | 485 (61.5 %) | 99 (52.7 %) | 386 (64.2 %) | Referent | – | Referent | – |

| Yes | 304 (38.5 %) | 89 (47.3 %) | 215 (35.8 %) | 1.61 (1.16, 2.25) | <0.01 | 1.82 (1.25, 2.63) | <0.01 |

| Housing status after release | |||||||

| Own housing | 177 (37.6 %) | 44 (40.7 %) | 133 (36.6 %) | Referent | – | – | – |

| Temporary or transitional housing | 263 (55.8 %) | 58 (53.7 %) | 205 (56.5 %) | 0.86 (0.55, 1.34) | 0.49 | – | – |

| Homeless/shelter or other emergency housing arrangement | 31 (6.6 %) | 6 (5.6 %) | 25 (6.9 %) | 0.73 (0.28, 1.88) | 0.51 | ||

| Total lifetime incarceration | |||||||

| Less than 5 years | 430 (54.6 %) | 87 (46.3 %) | 343 (57.2 %) | Referent | – | Referent | – |

| 5 or more years | 358 (45.4 %) | 101 (53.7 %) | 257 (42.8 %) | 1.55 (1.12, 2.15) | <0.01 | 1.73 (1.18, 2.52) | <0.01 |

| Charged with any violent offenses for index incarceration | |||||||

| No | 687 (87.1 %) | 151 (80.3 %) | 536 (89.2 %) | Referent | – | Referent | – |

| Yes | 102 (12.9 %) | 37 (19.7 %) | 65 (10.8 %) | 2.02 (1.30, 3.14) | <0.01 | 1.51 (1.14, 2.00) | <0.01 |

| Charged with any drug-related offenses for index incarceration | |||||||

| No | 467 (59.2 %) | 127 (67.6 %) | 340 (56.6 %) | Referent | – | Referent | – |

| Yes | 322 (40.8 %) | 61 (32.4 %) | 261 (43.4 %) | 0.63 (0.44, 0.88) | <0.01 | 0.66 (0.50, 0.88) | <0.01 |

| Charged with any property-related offenses for index incarceration | |||||||

| No | 520 (65.9 %) | 116 (61.7 %) | 404 (67.2 %) | Referent | – | – | – |

| Yes | 269 (34.1 %) | 72 (38.3 %) | 197 (32.8 %) | 1.27 (0.91, 1.79) | 0.16 | – | – |

| Charged with any public disorder offenses for index incarceration | |||||||

| No | 678 (85.9 %) | 157 (83.5 %) | 521 (86.7 %) | Referent | – | – | – |

| Yes | 111 (14.1 %) | 31 (16.5 %) | 80 (13.3 %) | 1.29 (0.82, 2.02) | 0.27 | – | – |

| Charged with any probation/parole violation for index incarceration | |||||||

| No | 711 (90.1 %) | 171 (91.0 %) | 540 (89.9 %) | Referent | – | – | – |

| Yes | 78 (9.9 %) | 17 (9.0 %) | 61 (10.1 %) | 0.88 (0.50, 1.55) | 0.66 | – | – |

| Charged with any other type of charge of index incarceration | |||||||

| No | 714 (90.5 %) | 173 (92.0 %) | 541 (90.0 %) | Referent | – | – | – |

| Yes | 75 (9.5 %) | 15 (8.0 %) | 60 (10.0 %) | 0.78 (0.43, 1.41) | 0.41 | – | – |

| Sentenced for index incarceration | |||||||

| No | 553 (70.3 %) | 133 (70.7 %) | 420 (70.1 %) | – | – | – | – |

| Yes | 234 (29.7 %) | 55 (29.3 %) | 179 (29.9 %) | – | – | – | – |

| Days spent in jail during index incarceration | |||||||

| Less than 91 days | 486 (62.3 %) | 120 (63.8 %) | 366 (61.8 %) | Referent | – | Referent | – |

| 91–180 days | 172 (22.1 %) | 47 (25.0 %) | 125 (21.1 %) | 1.15 (0.77, 1.70) | 0.26 | 1.53 (0.46, 5.13) | 0.66 |

| 181–272 days | 62 (7.9 %) | 8 (4.3 %) | 54 (9.1 %) | 0.45 (0.21, 0.98) | <0.05 | 1.31 (0.30, 4.26) | 0.55 |

| 272–370 days | 60 (7.7 %) | 13 (6.9 %) | 47 (7.9 %) | 0.84 (0.44, 1.61) | 0.65 | 1.09 (0.28, 4.19) | 0.93 |

| Released on probation or parole | |||||||

| No | 637 (79.8 %) | 149 (78.4 %) | 488 (80.3 %) | Referent | – | – | – |

| Yes | 161 (20.2 %) | 41 (21.6 %) | 120 (19.7 %) | 1.12 (0.75, 1.67) | 0.58 | – | – |

| Average time to re-incarceration | |||||||

| Mean number of days (SD) | – | 77.9 (57) | – | – | – | – | – |

| Newly diagnosed with HIV during index incarceration | |||||||

| No | 756 (96.2 %) | 179 (95.2 %) | 577 (96.5 %) | Referent | – | – | – |

| Yes | 30 (3.8 %) | 9 (4.8 %) | 21 (3.5 %) | 1.38 (0.62, 3.07) | 0.43 | – | – |

| CD4 count during index incarceration | |||||||

| Less than 350 | 258 (45.2 %) | 50 (37.3 %) | 208 (47.6 %) | Referent | – | Referent | – |

| At or greater than 350 | 313 (54.8 %) | 84 (62.7 %) | 229 (52.4 %) | 0.66 (0.44, 0.98) | <0.05 | 0.71 (0.46, 1.10) | 0.12 |

| Viral load during index incarceration | |||||||

| Less than 400 | 368 (67.3 %) | 79 (61.2 %) | 289 (69.1 %) | Referent | – | – | – |

| At or greater than 400 | 179 (32.7 %) | 50 (38.8 %) | 129 (30.9 %) | 1.42 (0.94, 2.14) | 0.10 | – | – |

| Ever diagnosed with a major psychiatric disorder | |||||||

| No | 589 (73.8 %) | 126 (66.3 %) | 463 (76.2 %) | Referent | – | Referent | – |

| Yes | 209 (26.2 %) | 64 (33.7 %) | 145 (23.8 %) | 1.62 (1.14, 2.31) | <0.01 | 2.07 (1.14, 3.75) | <0.05 |

| Composite alcohol score before index incarceration | |||||||

| 0.15< | 499 (66.5 %) | 120 (66.3 %) | 379 (66.6 %) | Referent | – | – | – |

| 0.15 | 251 (33.5 %) | 61 (22.7 %) | 190 (33.4 %) | 1.01 (0.71, 1.45) | 0.94 | – | – |

| Composite drug score before index incarceration | |||||||

| 0.12< | 250 (33.6 %) | 65 (35.9 %) | 185 (32.8 %) | Referent | – | – | – |

| 0.12 | 495 (66.4 %) | 116 (64.1 %) | 379 (67.2 %) | 0.87 (0.61, 1.24) | 0.44 | – | – |

| Composite psychiatric score before index incarceration | |||||||

| 0.22< | 360 (47.6 %) | 84 (46.2 %) | 276 (48.0 %) | Referent | – | – | – |

| 0.22 | 397 (52.4 %) | 98 (53.8 %) | 299 (52.0 %) | 1.08 (0.77, 1.50) | 0.66 | – | – |

| Discharge plan was completed for client prior to release | |||||||

| Yes | 104 (14.1 %) | 23 (12.6 %) | 81 (14.5 %) | Referent | – | – | – |

| No | 636 (85.9 %) | 159 (87.4 %) | 477 (85.5 %) | 1.17 (0.71, 1.93) | 0.53 | – | – |

| Met with community provider in regards to HIV primary care after release | |||||||

| No | 271 (36.1 %) | 75 (42.4 %) | 196 (34.1 %) | Referent | Referent | – | |

| Yes | 480 (63.9 %) | 102 (57.6 %) | 378 (65.9 %) | 0.71 (0.50, 1.00) | <0.05 | 0.64 (0.33, 1.22) | 0.17 |

| Met with community provider in regards to substance abuse after release | |||||||

| No | 350 (51.2 %) | 79 (50.0 %) | 271 (51.6 %) | Referent | – | – | – |

| Yes | 333 (48.8 %) | 79 (50.0 %) | 254 (48.4 %) | 1.07 (0.75, 1.52) | 0.72 | – | – |

| Met with community provider in regards to mental health care after release | |||||||

| No | 360 (67.7 %) | 102 (75.6 %) | 258 (65.0 %) | Referent | – | Referent | – |

| Yes | 172 (32.3 %) | 33 (24.4 %) | 139 (35.0 %) | 0.60 (0.39, 0.94) | <0.05 | 0.58 (0.32, 1.05) | 0.07 |

| Met with community provider in regards to employment after release | |||||||

| No | 373 (92.3 %) | 94 (96.9 %) | 279 (90.9 %) | Referent | – | – | – |

| Yes | 31 (7.7 %) | 3 (3.1 %) | 28 (9.1 %) | 0.32 (0.10, 1.07) | 0.06 | – | – |

| Met with community provider in regards to housing after release | |||||||

| No | 387 (66.6 %) | 89 (65.9 %) | 298 (66.8 %) | Referent | – | – | – |

| Yes | 194 (33.4 %) | 46 (34.1 %) | 148 (33.2 %) | 1.04 (0.69, 1.56) | 0.85 | – | – |

| Attended any form of drug treatment program after release | |||||||

| No | 485 (67.5 %) | 116 (67.1 %) | 369 (67.7 %) | Referent | – | – | – |

| Yes | 233 (32.5 %) | 57 (32.9 %) | 176 (32.3 %) | 1.03 (0.72, 1.48) | 0.87 | – | – |

Independent variables with p < 0.05 in the multivariate model are highlighted in bold

Results from the multivariate logistic regression assessing pre-index incarceration predictors of subsequent re-incarceration are presented in Table 1. Participants reporting to have been homeless before the index incarceration were more likely to be re-incarcerated during the six months following release (AOR = 1.82, p < 0.01). Those who were re-incarcerated were also more likely to have been cumulatively incarcerated for five or more years in their lifetime (OR = 1.73, p < 0.01) and more likely to have been charged with a violent offense for their index incarceration (AOR = 1.51, p < 0.01), but less likely to have been charged with a drug-related offense (AOR = 0.66, p < 0.01).

In the multivariate logistic regression assessing pre-release predictors of re-incarceration, neither the length of the index incarceration nor HIV-related clinical outcomes during incarceration were predictive of re-incarceration during the six months following release (see Table 1).

In multivariate logistic regression assessing post-release predictors of re-incarceration, participants reporting not having any health insurance or medical benefits in the 30 days following release from index incarceration (AOR = 0.34, p < 0.05) and those reporting having been diagnosed with a major psychiatric disorder were more likely to be re-incarcerated (OR = 2.07, p < 0.05) (see Table 1). Additionally, compared to those in the 20–38 age range, being in the 45–49 age range (AOR = 0.40, p < 0.05) and being 50 years or older (AOR = 0.40, p < 0.05) appeared to be protective against re-incarceration (data not shown).

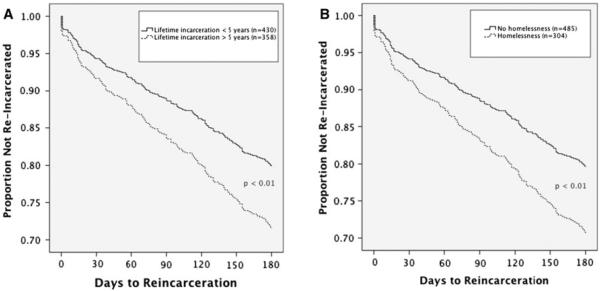

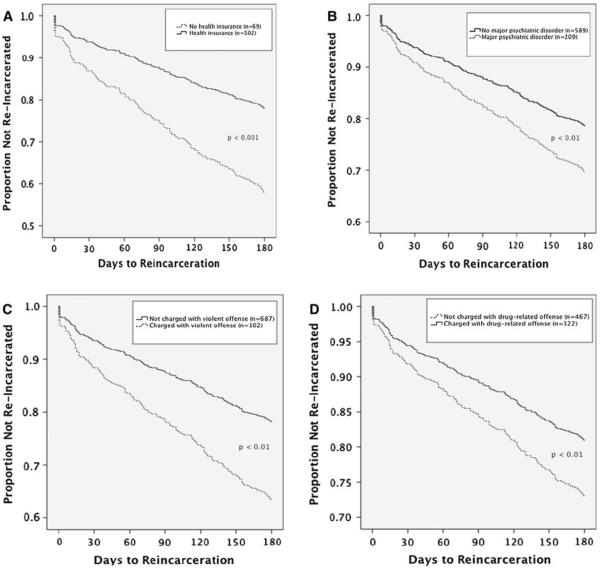

Figure 2 presents results from the univariate Cox proportional-hazards regression assessing predictors of time to re-incarceration. Individuals who were cumulatively incarcerated for five years or longer in their lifetime (HR 1.49, p < 0.01) (see Fig. 2a), homeless prior to index incarceration (HR 1.52, p < 0.01) (see Fig. 2b), ever diagnosed with a major psychiatric disorder (HR 1.50, p < 0.01) (see Fig. 3b), or charged with any violent offenses for the index incarceration (HR 1.85, p < 0.01) (see Fig. 3c) were more likely to be re-incarcerated sooner. Conversely, having any health insurance or medical benefits after release (HR 0.47, p < 0.001) (see Fig. 3a) or being charged with any drug-related offenses for the index incarceration (HR 0.67, p < 0.01) (see Fig. 3d) was associated with longer time to re-incarceration.

Fig. 2.

Structural-level predictors of time to re-incarceration

Fig. 3.

Individual-level predictors of time to re-incarceration

Discussion

In our analysis of this large sample of recently released HIV-infected jail detainees, we identified several individual- and structural-level predictors of recidivism. With regard to individual-level predictors, having a major psychiatric illness appeared to be predictive of recidivism and was associated with shorter time to re-incarceration. One structural-level factor, not having health insurance or medical benefits following release from incarceration, also appeared to be predictive of recidivism and shorter time to re-incarceration. While linking individuals to health insurance or medical benefits after jail release may not necessarily reduce risk for recidivism, health insurance may represent a stabilizing resource or attainment of some level of stability or, in the very least, indicates greater potential for accessing health services. Conversely, its absence may be a marker for a level of instability or lack of access to supportive resources that contributes to risk for re-incarceration.

If having health insurance has any stabilizing effects in this population, interventions assisting HIV-infected jail detainees in securing healthcare entitlements and medical benefits may have the potential to impact risk for recidivism following jail release, although this association needs to be more closely explored in future studies [33]. Medical entitlements, such as Medicaid, can be terminated for those who enter jails and prisons, with an estimated 90 % of states having implemented policies that terminate Medicaid coverage for inmates [34]. Although expansion of Medicaid coverage through the Affordable Care Act will allow significantly more individuals to access healthcare, routine Medicaid termination practices in the criminal justice system will continue to present a considerable barrier to efforts to expand healthcare coverage, particularly for the most vulnerable populations. Suspending, rather than terminating, Medicaid benefits upon incarceration would likely improve the health of those returning to the community [34] and may have other far-reaching health and social benefits, with the potential to be cost saving. Clarifying these potential benefits for policymakers and redressing this broad lapse in healthcare coverage should be a key priority in efforts to improve the health of individuals with HIV who are in the criminal justice system.

Our finding on prior major psychiatric diagnosis as a predictor of recidivism suggests the need for interventions specifically targeting recurrent criminal justice involvement among individuals with major psychiatric disorders. Broader efforts to integrate mental health care with HIV care would likely increase the accessibility of mental health care for this population and may have the potential to reduce criminal justice involvement among those who are mentally ill alongside improving both HIV-related and mental health outcomes. However, because few health and mental health interventions for criminal justice-involved individuals with HIV have been assessed for their effects on recidivism, future studies of such interventions should consider incorporating recidivism as an outcome and assessing the potential effects of different health-related services.

Being charged with a violent offense was also predictive of re-incarceration, potentially highlighting a subset of jail detainees that may require focused intervention, although the relationship between criminal charge and recidivism needs to be much better characterized. Interestingly, those charged with drug-related offenses at the index incarceration were less likely to be re-incarcerated, an unusual correlation given the extensive literature on recidivism among people who use drugs. It is possible that in this particular study, the high level of linkage to ancillary services, such as substance abuse treatment programs, may have affected the relationship between drug use and re-incarceration.

Two other important structural factors explored in the study—incarceration history and prior homelessness—were also predictive of recidivism in this sample. The finding that the longer individuals are incarcerated for over their lifetime, the more likely they are to return to the criminal justice system, may reflect the destabilizing nature of incarceration and recidivism. The correctional system, in addition to being a powerful acculturating environment, has both short and long-term destabilizing effects and should be targeted directly as a risk factor for recidivism [35]. Prior homelessness is another potentially destabilizing factor related to recidivism that should be explored in future interventions. The link between housing instability and HIV has been demonstrated previously [36–38] and there is a growing evidence-base for housing-based structural interventions for people living with HIV and their cost-effectiveness [37–41]. Less is known, however, about the potential effects of this type of structural intervention on recidivism among people with HIV who are unstably housed, an outcome that should be evaluated in future housing-based prevention interventions. Our findings underscore that interventions targeting recidivism should address the structural and institutional factors contributing to recidivism alongside the individual-level risk factors. Important key structural factors, such as discrimination in arrests and sentencing and community and neighborhood-level factors, were not explored in this study and merit thorough investigation.

Our findings may not be generalizable to the broader jail population. Selection bias and attrition bias were important limitations of the study. For example, individuals participating in EnhanceLink had a length of stay that greatly exceeded the median length of stay of typical jail detainees. A significant proportion of individuals (n = 450) enrolled in the study also had no recorded release date from their index incarceration (e.g. could have been transferred to another correctional facility from which they were subsequently released to the community). Without further information on whether these individuals were released to the community, uncertainty in their release status resulted in them being excluded from analysis. Further, due to loss of participants over the course of the study, missing data may have also increased the potential for type II error in multivariate regression analyses and, if the data were not missing at random, could have biased odds-ratios. As with most studies involving vulnerable populations, outside of a few time points, more dynamic data on key variables were also not available. Housing status, particularly in this population, is likely to be far more fluid than what data from a few time points can capture. We assessed housing status in the 30 days prior to the index incarceration and in the 30 days after release and used these two time points to predict re-incarceration events that may have occurred much later on, with participants possibly having experienced changes in their housing status. This may explain why housing status immediately before the index incarceration was predictive of re-incarceration but housing status in the 30 days following release was not. Immediately following release, far fewer clients reported being homeless or shelter use, with most reporting being in temporary or transitional housing. This reported status likely changes over time for many individuals, and although there is data available on their housing status at 6 months, this data cannot be used to predict re-incarceration events that have already occurred and would be missing for those who were re-incarcerated by the six-month time point. Despite this limitation, our analysis suggests that, in the very least, homelessness may be marker for a level of instability that place individuals at risk for re-entry into the criminal justice system. Housing instability after release from incarceration and the pathways by which it impacts recidivism ultimately need to be better understood so that interventions can effectively address these risk dynamics.

Conclusions

Recidivism is a major destabilizing force in the lives of individuals with HIV and merits focused intervention. Individual and structural-level risk factors for recidivism identified in this study should be further studied in future health interventions for individuals with HIV who are involved in the criminal justice system. Reducing criminal justice involvement should be a component of efforts to promote more sustainable improvements in health and well-being among individuals living with HIV.

Acknowledgments

Enhancing Linkages to HIV Primary Care Services Initiative is a HRSA-funded Special Project of National Significance. Funding for this research was also provided through career development grants from the National Institute on Drug Abuse (K24 DA017072, FLA), research Grants from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (R01 AA018944, FLA), and an institutional research training grant from NIAID (T32 AI007517, AA). The funding sources played no role in study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, writing of the manuscript or the decision to submit the paper for publication.

References

- 1.Spaulding AC, Seals RM, Page MJ, Brzozowski AK, Rhodes W, Hammett TM. HIV/AIDS among inmates of and releasees from US correctional facilities, 2006: declining share of epidemic but persistent public health opportunity. PLoS One. 2009;4:e7558. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0007558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Marlow E, White MC, Tulsky JP, Estes M, Menendez E. Recidivism in HIV-infected incarcerated adults: influence of the lack of a high school education. J Urban Health. 2008;85:585–95. doi: 10.1007/s11524-008-9272-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Westergaard RP, Kirk GD, Richesson DR, Galai N, Mehta SH. Incarceration predicts virologic failure for HIV-infected injection drug users receiving antiretroviral therapy. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;53:725–31. doi: 10.1093/cid/cir491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kerr T, Marshall A, Walsh J, Palepu A, Tyndall M, Montaner J, et al. Determinants of HAART discontinuation among injection drug users. AIDS Care. 2005;17:539–49. doi: 10.1080/09540120412331319778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Beckwith CG, Zaller ND, Fu JJ, Montague BT, Rich JD. Opportunities to diagnose, treat, and prevent HIV in the criminal justice system. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2010;55(Suppl 1):S49–55. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181f9c0f7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Draine J, Ahuja D, Altice FL, Arriola KJ, Avery AK, Beckwith CG, et al. Strategies to enhance linkages between care for HIV/ AIDS in jail and community settings. AIDS Care. 2011;23:366–77. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2010.507738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Baillargeon J, Penn JV, Knight K, Harzke AJ, Baillargeon G, Becker EA. Risk of reincarceration among prisoners with cooccurring severe mental illness and substance use disorders. Adm Policy Ment Health. 2010;37:367–74. doi: 10.1007/s10488-009-0252-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Milloy MJ, Wood E, Small W, Tyndall M, Lai C, Montaner J, Kerr T. Incarceration experiences in a cohort of active injection drug users. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2008;27:693–9. doi: 10.1080/09595230801956157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Baillargeon J, Giordano TP, Harzke AJ, Spaulding AC, Wu ZH, Grady JJ, et al. Predictors of reincarceration and disease progression among released HIV-infected inmates. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2010;24:389–94. doi: 10.1089/apc.2009.0303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Morrow KM. HIV, STD, and hepatitis risk behaviors of young men before and after incarceration. AIDS Care. 2009;21:235–43. doi: 10.1080/09540120802017586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wood E, Li K, Small W, Montaner JS, Schechter MT, Kerr T. Recent incarceration independently associated with syringe sharing by injection drug users. Public Health Rep. 2005;120:150–6. doi: 10.1177/003335490512000208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Luther JB, Reichert ES, Holloway ED, Roth AM, Aalsma MC. An exploration of community reentry needs and services for prisoners: a focus on care to limit return to high-risk behavior. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2011;25:475–81. doi: 10.1089/apc.2010.0372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Werb D, Kerr T, Small W, Li K, Montaner J, Wood E. HIV risks associated with incarceration among injection drug users: implications for prison-based public health strategies. J Public Health (Oxf) 2008;30:126–32. doi: 10.1093/pubmed/fdn021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Milloy MJ, Kerr T, Buxton J, Rhodes T, Guillemi S, Hogg R, et al. Dose-response effect of incarceration events on nonadherence to HIV antiretroviral therapy among injection drug users. J Infect Dis. 2011;203:1215–21. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jir032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Springer SA, Pesanti E, Hodges J, Macura T, Doros G, Altice FL. Effectiveness of antiretroviral therapy among HIV-infected prisoners: reincarceration and the lack of sustained benefit after release to the community. Clin Infect Dis. 2004;38:1754–60. doi: 10.1086/421392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stephenson BL, Wohl DA, Golin CE, Tien HC, Stewart P, Kaplan AH. Effect of release from prison and re-incarceration on the viral loads of HIV-infected individuals. Public Health Rep. 2005;120:84–8. doi: 10.1177/003335490512000114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Maru DS, Bruce RD, Walton M, Mezger JA, Springer SA, Shield D, Altice FL. Initiation, adherence, and retention in a randomized controlled trial of directly administered antiretroviral therapy. AIDS Behav. 2008;12:284–93. doi: 10.1007/s10461-007-9336-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Palepu A, Tyndall MW, Chan K, Wood E, Montaner JS, Hogg RS. Initiating highly active antiretroviral therapy and continuity of HIV care: the impact of incarceration and prison release on adherence and HIV treatment outcomes. Antivir Ther. 2004;9:713–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bauserman RL, Richardson D, Ward M, Shea M, Bowlin C, Tomoyasu N, Solomon L. HIV prevention with jail and prison inmates: Maryland's prevention case management program. AIDS Educ Prev. 2003;15:465–80. doi: 10.1521/aeap.15.6.465.24038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wolitski RJ. Relative efficacy of a multisession sexual risk-reduction intervention for young men released from prisons in 4 states. Am J Public Health. 2006;96:1854–61. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.056044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Myers J, Zack B, Kramer K, Gardner M, Rucobo G, Costa-Taylor S. Get connected: an HIV prevention case management program for men and women leaving California prisons. Am J Public Health. 2005;95:1682–4. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.055947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Belenko SR, Shedlin M, Chaple M. HIV risk behaviors, knowledge, and prevention service experiences among African American and other offenders. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2005;16:108–29. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2005.0108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bryan A, Robbins RN, Ruiz MS, O'Neill D. Effectiveness of an HIV prevention intervention in prison among African Americans, Hispanics, and Caucasians. Health Educ Behav. 2006;33:154–77. doi: 10.1177/1090198105277336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ehrmann T. Community-based organizations and HIV prevention for incarcerated populations: three HIV prevention program models. AIDS Educ Prev. 2002;14:75–84. doi: 10.1521/aeap.14.7.75.23866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ross MW, Harzke AJ, Scott DP, McCann K, Kelley M. Outcomes of project wall talk: an HIV/AIDS peer education program implemented within the Texas State Prison system. AIDS Educ Prev. 2006;18:504–17. doi: 10.1521/aeap.2006.18.6.504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Needels K, James-Burdumy S, Burghardt J. Community case management for former jail inmates: its impacts on rearrest, drug use, and HIV risk. J Urban Health. 2005;82:420–33. doi: 10.1093/jurban/jti092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gasiorowicz M, Llanas MR, DiFranceisco W, Benotsch EG, Brondino MJ, Catz SL, et al. Reductions in transmission risk behaviors in HIV-positive clients receiving prevention case management services: findings from a community demonstration project. AIDS Educ Prev. 2005;17:40–52. doi: 10.1521/aeap.17.2.40.58694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Blankenship KM, Smoyer AB, Bray SJ, Mattocks K. Black-white disparities in HIV/AIDS: the role of drug policy and the corrections system. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2005;16:140–56. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2005.0110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Epperson MW, El-Bassel N, Chang M, Gilbert L. Examining the temporal relationship between criminal justice involvement and sexual risk behaviors among drug-involved men. J Urban Health. 2010;87:324–36. doi: 10.1007/s11524-009-9429-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vigilante KC, Flynn MM, Affleck PC, Stunkle JC, Merriman NA, Flanigan TP, et al. Reduction in recidivism of incarcerated women through primary care, peer counseling, and discharge planning. J Womens Health. 1999;8:409–15. doi: 10.1089/jwh.1999.8.409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.McLellan AT, Cacciola JC, Alterman AI, Rikoon SH, Carise D. The addiction severity index at 25: origins, contributions and transitions. Am J Addict. 2006;15:113–24. doi: 10.1080/10550490500528316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.McLellan AT, Luborsky L, Woody GE, O'Brien CP. An improved diagnostic evaluation instrument for substance abuse patients. The addiction severity index. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1980;168:26–33. doi: 10.1097/00005053-198001000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Morrissey JP, Cuddeback GS, Cuellar AE, Steadman HJ. The role of Medicaid enrollment and outpatient service use in jail recidivism among persons with severe mental illness. Psychiatr Serv. 2007;58:794–801. doi: 10.1176/ps.2007.58.6.794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wakeman SE, McKinney ME, Rich JD. Filling the gap: the importance of Medicaid continuity for former inmates. J Gen Intern Med. 2009;24:860–2. doi: 10.1007/s11606-009-0977-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Maru DS, Basu S, Altice FL. HIV control efforts should directly address incarceration. Lancet Infect Dis. 2007;7:568–9. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(07)70190-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chen NE, Meyer JP, Avery AK, Draine J, Flanigan TP, Lincoln T, et al. Adherence to HIV treatment and care among previously homeless jail detainees. AIDS Behav. 2011 doi: 10.1007/s10461-011-0080-2. doi:10.1007/s10461-011-0080-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Friedman MS, Marshal MP, Stall R, Kidder DP, Henny KD, Courtenay-Quirk C, et al. Associations between substance use, sexual risk taking and HIV treatment adherence among homeless people living with HIV. AIDS Care. 2009;21:692–700. doi: 10.1080/09540120802513709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Royal SW, Kidder DP, Patrabansh S, Wolitski RJ, Holtgrave DR, Aidala A, et al. Factors associated with adherence to highly active antiretroviral therapy in homeless or unstably housed adults living with HIV. AIDS Care. 2009;21:448–55. doi: 10.1080/09540120802270250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wolitski RJ, Kidder DP, Pals SL, Royal S, Aidala A, Stall R, et al. Randomized trial of the effects of housing assistance on the health and risk behaviors of homeless and unstably housed people living with HIV. AIDS Behav. 2010;14:493–503. doi: 10.1007/s10461-009-9643-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Holtgrave DR, Briddell K, Little E, Bendixen AV, Hooper M, Kidder DP, et al. Cost and threshold analysis of housing as an HIV prevention intervention. AIDS Behav. 2007;11:162–6. doi: 10.1007/s10461-007-9274-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kidder DP, Wolitski RJ, Royal S, Aidala A, Courtenay-Quirk C, Holtgrave DR, et al. Access to housing as a structural intervention for homeless and unstably housed people living with HIV: rationale, methods, and implementation of the housing and health study. AIDS Behav. 2007;11:149–61. doi: 10.1007/s10461-007-9249-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]