Abstract

Background

Differences between those who engage in nonmedical prescription opioid use for reasons other than pain relief and those who engage in nonmedical use for reasons related to pain only are not well understood.

Methods

Adults in a residential treatment program participated in a cross-sectional self-report survey. Participants reported whether they used opioids for reasons other than pain relief (e.g., help sleep, improve mood, or relieve stress). Within those with past-month nonmedical opioid use (n=238), logistic regression tested differences between those who reported use for reasons other than pain relief and those who did not.

Results

Nonmedical use of opioids for reasons other than pain relief was more common (66%) than nonmedical use for pain relief only (34%), and those who used for reasons other than pain relief were more likely to report heavy use (43% vs. 11%). Nonmedical use for reasons other than pain relief was associated with having a prior overdose (Odds Ratio [OR]=2.54), 95% CI:1.36-4.74) and use of heroin (OR=4.08, 95% CI:1.89-8.79), barbiturates (OR=6.44, 95% CI:1.47, 28.11), and other sedatives (OR=5.80, 95% CI: 2.61, 12.87). Individuals who reported nonmedical use for reasons other than pain relief had greater depressive symptoms (13.1 vs. 10.5) and greater pain medication expectancies across all three domains (pleasure/social enhancement, pain reduction, negative experience reduction).

Conclusions

Among patients in addictions treatment, individuals who report nonmedical use of prescription opioids for reasons other than pain relief represent an important clinical sub-group with greater substance use severity and poorer mental health functioning.

Keywords: prescription opioids, nonmedical use, pain, addictions treatment

1. Introduction

Medical and nonmedical use (i.e., using more than prescribed by a medical provider, without a prescription, or for purposes other than pain care) of opioid pain medications has increased substantially in the U.S. in the past decade, particularly among adults (Fortuna, Robbins, Caiola, Joynt & Halterman, 2010; Paulozzi, Budnitz & Xi, 2006; Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration Office of Applied Studies, 2009; Zacny, Bigelow, Compton, Foley, Iguchi & Sannerud, 2003). Consequently, prescription opioids are now among the most common drugs used nonmedically among Americans (Substance Abuse & Mental Health Services Administration, 2010). Given the negative consequences that have been associated with this rise in nonmedical prescription opioid use, most notably the rise in unintentional overdose deaths due to prescription opioids (Okie, 2010; Paulozzi & Ryan, 2006), reducing nonmedical use has become a crucial public health issue.

In an effort to understand this growing public health problem, it is important to examine why individuals report that they engage in nonmedical use of opioids. A small body of literature has examined self-reported reasons for nonmedical prescription opioid use, most of which has utilized samples of late high school and college-age youth (McCabe, Cranford, Boyd & Teter, 2007; McCabe, Boyd, Cranford & Teter, 2009a; McCabe, Boyd & Teter, 2009b). In these studies, those using prescription opioids only for pain relief were less likely than those reporting other motives to report behaviors consistent with a diagnosable substance use disorder. (McCabe, et al., 2007; McCabe, et al., 2009a) In another study among adolescents in grades 7 through 12; when nonmedical opioid users were stratified into two groups, those self-treating pain and those using for non-pain-related motives, those using due to non-pain-related motives reported more drug-related problems (Boyd, McCabe, Cranford & Young, 2006).

In addition to focusing on younger populations, most of the prior research on motives for nonmedical opioid use has studied individuals who are relatively high functioning, such as college students. It is also important to understand distinctions in type of nonmedical use in adults with more established patterns of substance use to understand how type of use may perpetuate and maintain substance use. This work could be particularly important in addictions treatment settings, which frequently treat individuals with recent nonmedical use of opioids (Price, Ilgen & Bohnert, 2011). The only study of motives for nonmedical prescription drug use among middle-aged and older adults to our knowledge included a sample of 18- to 65-year-old methadone maintenance patients, residential drug treatment clients, and active street drug users (Rigg & Ibanez, 2010). In this study, use for reasons other than pain relief was common (Rigg & Ibanez, 2010).

Understanding the reasons for substance use, including use of prescription opioids, is important for the development of drug use behavior change interventions (Pomazal & Brown, 1977). The present study sought to compare those who engage in nonmedical prescription opioid use for reasons other than pain relief and those who engage in nonmedical use for reasons related to pain only in a sample of adults in residential addictions treatment. This study focused on the distinction between nonmedical use of prescription opioids for self-treatment of pain vs. other motivations specifically because prior research in adolescents and young adults has highlighted the importance of this distinction (Boyd, et al., 2006; McCabe, et al., 2007; McCabe, et al., 2009b). Additionally, pain is common among individuals in addictions treatment (Trafton, Oliva, Horst, Minkel & Humphreys, 2004), and persistent pain is associated with poorer addictions treatment outcomes (Caldeiro, Malte, Calsyn, Baer, Nichol, Kivlahan & Saxon, 2008). Nonmedical use that is solely for the purpose of pain relief likely indicates poorly managed pain, for which interventions focused on improving pain management may be an appropriate adjunct to traditional substance use-focused interventions. We also sought to extend prior studies by examining a broader array of correlates, including demographic, drug use-related, pain-related, and psychological factors.

2. Methods

2.1 Sample and Design

This study used cross-sectional data (Price, et al., 2011) addictions collected from January to November of 2009. Participants were recruited via presentations made collected at a large residential treatment center in Waterford, Michigan, which provides services to patients in the surrounding areas of Michigan, including the urban areas of Flint and Detroit. Data were by research staff to all patients during didactic groups at the treatment site. Patients requiring treatment for withdrawal at admission were treated in a separate detoxification unit prior to treatment on the unit where recruitment took place. Interested participants were informed of the study protocol and given the opportunity to provide written informed consent; those who consented were given a self-administered pen-and-paper questionnaire. Participants were compensated for their time with a $10 gift card. Exclusion criteria included being under the age of 18, being unable to speak or understand English, being unable to provide voluntary written consent, and having current acute psychotic symptoms.

In total, 351 individuals completed surveys, 24% of whom were female. The mean age was 35.6 (Standard Deviation [SD] = 10.8). The distribution of the primary substance for which treatment was sought in this sample was as follows: 30.2% alcohol, 19.4% heroin, 16.0% cocaine, 9.7% marijuana, 4.0% other opiates, and 20.8% other or missing. The average number of years of regular alcohol use to intoxication for participants with lifetime alcohol use was 10.8 (SD = 9.4). The average years of regular use for heroin, cocaine, and marijuana was 6.2 (SD = 5.9), 8.1 (SD = 7.4), and 11.3 (SD = 8.4) among users of each substance, respectively.

Primary analyses were restricted to individuals who reported past-month nonmedical use of prescription opioids, based on items from the Current Opioid Misuse Measure (COMM) (Butler, Budman, Fernandez, Houle, Benoit, Katz & Jamison, 2007), as described by Price and colleagues (2011) and below. This was the case for 238 of the 351 (68%) respondents. All study procedures were approved by the University of Michigan Medical School Institutional Review Board.

2.2 Measures

2.2.1 Opioid Pain Medication Use

The COMM is a 17-item measure that was developed to detect nonmedical use of opioids among individuals prescribed opioids for pain (Butler, et al., 2007). Based on prior research in the present sample, six items from the COMM were used to define nonmedical prescription opioid use (Price, et al., 2011), which have an α=0.93. These six items were: 1) “How often have you taken your medications differently from how they are prescribed?”; 2) “How often have you needed to take pain medications belonging to someone else?”; 3) “How often have you had to go to someone other than your prescribing physician to get sufficient pain relief from your medications?”; 4) “How often have you had to take more of your medication than prescribed?”; 5) “How often have you borrowed pain medication from someone else?”; and 6) “How often have you used your pain medication for symptoms other than pain (e.g., to help you sleep, improve your mood, or relieve stress)?” All items assessed past-month use and used a five-point scale ranging from “never” to “very often.” Individuals were further classified as nonmedical users who used for reasons other than pain if they reported any use in response to the question “How often have you used your pain medications for symptoms other than pain (e.g., to help you sleep, improve your mood, or relieve stress?)” Thus, individuals classified as using for reasons other than pain relief may or may not have also been using opioids for pain relief. Individuals who responded “never” to this question but endorsed at least one of the other five core COMM questions used to assess nonmedical use were classified as using nonmedically only for pain relief. The six core items selected from the COMM were also used to identify heavy non medical prescription opioid use; heavy nonmedical prescription opioid use was defined as a response of “very often” on any of the six items.

The Pain Medications Expectancy Questionnaire (PMEQ) (Ilgen, Roeder, Webster, Mowbray, Perron, Chermack & Bohnert, 2011) was used to assess the degree to which participants expect that they would use pain medications in specific situations. The PMEQ has three domains: pleasure/social enhancement, pain reduction, and negative experience reduction. For each domain, a mean score was created by averaging the responses of the corresponding items.

2.2.2 Pain

Pain severity and pain interference were measured using sub-scales from the West Haven-Yale Multidimensional Pain Inventory (WHYMPI) (Kerns, Turk & Rudy, 1985). In the pain severity sub-scale, 17 items using a Likert scale between 0 and 6 assess pain level, the degree to which pain limits participation in work, social activities, and chores, as well as impact of pain on mood and tension. In the pain interference sub-scale, 18 items, also using a scale of 0 to 6, assess the degree to which pain interferes with common activities.

2.2.3 Additional Measures

Demographic variables, including gender, race/ethnicity, marital status, education, and age, were assessed. Drug use in the 30 days prior to treatment was assessed with the Addiction Severity Index (ASI) (McLellan, Kushner, Metzger, Peters, Smith, Grissom, Pettinati & Argeriou, 1992). For each drug type, participants were asked “How many days in the 30 days before treatment have you used [name of drug]?” Lifetime overdose experience was assessed using the following item from the ASI (McLellan, et al., 1992): “How many times have you overdosed on drugs?” Physical health status was assessed using the Physical Component Summary (PCS) of the 12-item Short-Form (SF-12) Health Survey and mental health status was assessed using the Mental Component Summary (MCS) of the SF-12 (Ware, Kosinski & Keller, 1996); for both measures, higher scores indicated better physical or mental functioning. The nine-item Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) was used to assess the presence of depressive symptoms and severity of depression (Kroenke, Spitzer & Williams, 2001). Suicidal ideation was measured with the Beck Scale for Suicide Ideation (BSS) (Beck, Steer & Ranieri, 1988).

2.3 Statistical Analyses

All analyses were completed in Stata, version 10 (Statacorp, 2008). We calculated the percent of the sub-sample (those with nonmedical opioid use) in groups defined using the motive for use and heavy use variables from the COMM (Butler, et al., 2007). In the next step, we examined the bivariate associations of type of use (pain relief only vs. other motivations) with a number of demographic, drug use, health, and pain characteristics using logistic regressions. We further examined the relationship of each drug use-, health-, and pain-related variable with motive for use in a separate multivariable model that adjusted for age, sex, and race. A two-sided p-value of 0.05 was used for all significance testing. Because our prior analyses in this sample found that many individuals who endorse the COMM items do not also endorse the ASI single-item assessing past 30-day non-prescribed opioid medication use (Price, et al., 2011), we conducted supplementary analyses examining the relationship between endorsement of the ASI item and type of nonmedical opioid use.

2.3.1 Missing Data

None of the 351 respondents were missing data on the key variables of prescription opioid use, heavy use, and motivations for use. Of the 238 who had recent nonmedical prescription opioid use and were included in primary analyses, 10 (4%) had missing data on one or more of the covariates. All analyses used all available data.

3. Results

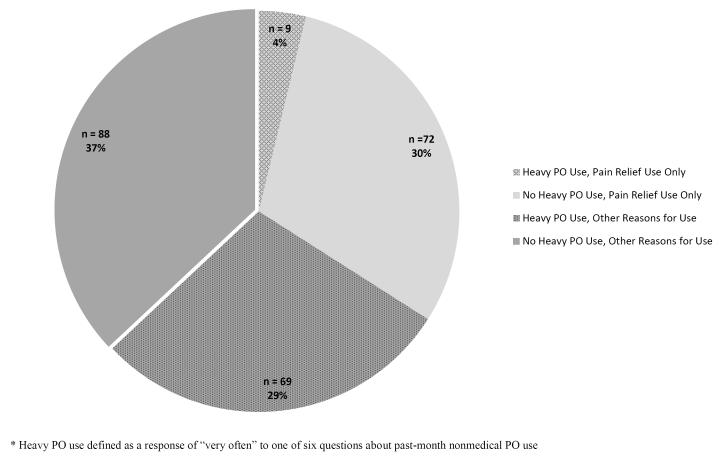

Figure 1 presents the distribution of type of nonmedical prescription opioid use among those respondents who endorsed any nonmedical prescription opioid use. Nonmedical use for motives other than pain relief was more common than use for pain relief only (66% vs. 34% of all nonmedical users). Heavy prescription opioid use was more common among those who used for reasons other than pain than those who only used for pain relief; among those who used for other reasons, 43% (69 out of 157) reported heavy use, while among those who only used for pain relief, 11% (9 out of 81) reported heavy use.

Figure 1.

Distribution of past-month nonmedical prescription opioid (PO) use, by motives for use.

Among those respondents who reported nonmedical prescription opioid use (n=238), those who reported use for reasons other than pain relief (n=157) were different from those who reported use only for pain relief (n=81) in a number of ways (Table 1). Participants who reported use for reasons other than pain relief were more likely to be female, white, and younger. In addition to a greater proportion of participants who reported use for reasons other than pain relief that were under the age of 35, the average age was younger in this group (33.7, SD = 10.3) than among those who did not use for reasons other than pain relief (38.0, SD = 10.8, t (235) =3.0, p = 0.003). Participants who reported use for reasons other than pain relief were also more likely to have experienced an overdose, and to have used heroin, barbiturates, and other sedatives in the past 30 days. Current suicidal ideation did not differ between groups, but the two other indices of mental health (overall mental health and depressive symptoms) both suggested that individuals who had used prescription opioids for reasons other than pain had poorer mental health. Specifically, for each unit increase in SF-12 mental health score (for which a higher score indicates better mental health), participants were 3% less likely to be in the group who had used for non-pain relief reasons, and for each unit increase in depressive symptom score, participants were 6% more likely to be in this group.

Table 1.

Bivariate associations with type of opioid use, defined by motive for use, among those with recent nonmedical use.

| Use for reasons other than pain relief (n = 157) |

Use for pain relief only (n = 81) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristics | N (%) | N (%) | OR (95% CI)a |

p- value |

| Demographic | ||||

| Female gender | 52 (33.3) | 13 (16.5) | 2.54 (1.28, 5.02) |

0.007 |

| Caucasian | 121 (77.1) | 48 (59.3) | 2.31 (1.30, 4.12) |

0.005 |

| Married/Partnered | 36 (22.9) | 13 (16.5) | 1.51 (0.75, 3.05) |

0.25 |

| High School Education completed | 104 (66.2) | 45 (55.6) | 1.57 (0.91, 2.72) |

0.11 |

| Age greater than 35 years | 70 (44.6) | 51 (63.8) | 0.46 (0.26, 0.80) |

0.006 |

| Drug Use a | ||||

| History of overdose | 63 (40.7) | 17 (21.3) | 2.54 (1.36, 4.74) |

0.003 |

| Past 30 day heroin use | 53 (33.8) | 9 (11.1) | 4.08 (1.89, 8.79) |

< 0.001 |

| Past 30 day barbiturate use | 22 (14.0) | 2 (2.5) | 6.44 (1.47, 28.11) |

0.01 |

| Past 30 day sedative use | 61 (38.9) | 8 (9.9) | 5.80 (2.61, 12.87) |

< 0.001 |

| Past 30 day cocaine use | 76 (48.4) | 34 (42.0) | 1.30 (0.76, 2.23) |

0.35 |

| Past 30 day cannabis use | 66 (42.0) | 29 (35.8) | 1.30 (0.75, 2.26) |

0.35 |

| Mean (S.D.) | Mean (S.D.) | OR (95% CI) a |

p- value |

|

| Mental and Physical Health | ||||

| Physical Health (SF-12 PCS) | 45.6 (10.9) | 45.9 (11.2) | 1.00 (0.97, 1.02) |

0.84 |

| Mental Health (SF-12 MCS) | 36.5 (12.2) | 41.7 (11.7) | 0.97 (0.94, 0.99) |

0.003 |

| Depression (PHQ-9) | 13.1 (6.5) | 10.5 (6.9) | 1.06 (1.02, 1.11) |

0.005 |

| Suicidal Ideation (BSS) | 1.8 (4.7) | 1.8 (4.1) | 1.00 (0.94, 1.06) |

1.00 |

| Pain | ||||

| Pain Severity score (WHYMPI) | 3.0 (1.6) | 2.9 (1.9) | 1.04 (0.89, 1.22) |

0.60 |

| Pain Interference score (WHYMPI) | 2.7 (1.5) | 2.5 (1.7) | 1.09 (0.92, 1.30) |

0.30 |

| Pain Medications Expectancy Questionnaire |

||||

| -Pleasure/Social Enhancement score |

4.7 (3.0) | 2.8 (2.3) | 1.29 (1.15, 1.45) |

< 0.001 |

| -Pain Reduction score | 7.2 (2.1) | 5.3 (2.2) | 1.48 (1.29, 1.69) |

< 0.001 |

| -Negative Experience Reduction score |

5.7 (2.9) | 3.2 (2.3) | 1.40 (1.25, 1.58) |

< 0.001 |

reference group: pain relief use only;

measured from the Addiction Severity Index OR = Odds Ratio; CI = Confidence Interval; SF-12 = Short Form Health Survey; PCS = Physical Component Summary; MCS = Mental Component Summary; PHQ-9 = Patient Health Questionnaire; BSS = Beck Scale for Suicide Ideation; WHYMPI = West Haven-Yale Multidimensional Pain Inventory

Individuals whose nonmedical prescription opioid use was motivated by pain relief only were no different from those who used for non-pain relief reasons in terms of self-rated pain severity or pain interference. For those reporting use for reasons other than pain relief, the average pain score on a scale of 0 to 10 was 3.0 (SD = 1.6), and those reporting using for pain relief only had an average pain score of 2.9 (SD = 1.9). However, those individuals who used prescription opioids for non-pain relief reasons had higher average pain medication expectancy scores for all three domains of this measure; an increase in one unit in expectancy score for each domain was associated with an increase between 29 and 48% in odds of non-pain relief prescription opioid use.

The associations of the drug use-, health-, and pain-related variables with motive for use after adjustment for demographic variables are reported in Table 2. In this table, the estimates reported in each row represent the results of a separate multivariable model that included the variable named in that row as well as age, sex, and race. The estimates obtained from these analyses were similar to those found in the bivariate regression models; the odds ratios obtained in these models were within the confidence intervals around the odds ratios obtained in the bivariate models, and vice versa.

Table 2.

Demographic-adjusteda models of use of prescription opioids for reasons other than pain relief, among those with recent use.

| Characteristics | OR (95% CI)b | p - value |

|---|---|---|

| Drug Use b | ||

| History of overdose | 2.10 (1.10, 4.02) | 0.03 |

| Past 30 day heroin use | 3.14 (1.41, 6.96) | 0.005 |

| Past 30 day barbiturate use | 4.91 (1.10, 21.86) | 0.04 |

| Past 30 day sedative use | 4.54 (2.00, 10.30) | < 0.001 |

| Past 30 day cocaine use | 1.33 (0.74, 2.36) | 0.34 |

| Past 30 day cannabis use | 1.17 (0.65, 2.10) | 0.61 |

| Mental and Physical Health | ||

| Physical Health (SF-12 PCS) | 0.98 (0.95, 1.01) | 0.19 |

| Mental Health (SF-12 MCS) | 0.97 (0.95, 0.99) | 0.01 |

| Depression (PHQ-9) | 1.06 (1.01, 1.11) | 0.01 |

| Suicidal Ideation (BSS) | 1.01 (0.95, 1.07) | 0.86 |

| Pain | ||

| Pain Severity score (WHYMPI) | 1.05 (0.89, 1.24) | 0.56 |

| Pain Interference score (WHYMPI) | 1.12 (0.93, 1.35) | 0.23 |

| Pain Medications Expectancy | ||

| -Pleasure/Social Enhancement score | 1.24 (1.10, 1.39) | < 0.001 |

| -Pain Reduction score | 1.41 (1.23, 1.63) | < 0.001 |

| -Negative Experience Reduction score | 1.34 (1.19, 1.52) | < 0.001 |

each model contains the covariate of interest along with age, race, and sex.

reference group: pain relief use only

measured from the Addiction Severity Index OR = Odds Ratio; CI = Confidence Interval; SF-12 = Short Form Health Survey; PCS = Physical Component Summary; MCS = Mental Component Summary; PHQ-9 = Patient Health Questionnaire; BSS = Beck Scale for Suicide Ideation; WHYMPI = West Haven-Yale Multidimensional Pain Inventory

3.1 Supplementary Analysis

Among the 81 individuals who had only reported nonmedical prescription opioid use for the purpose of self-treatment of pain, only 10 (12%) endorsed the ASI item assessing past 30-day prescription opioid use. In contrast, among the 157 individuals who reported use for reasons other than pain care, 71 (45%) endorsed the ASI past 30-day prescription opioid item. A χ2 test indicated that this difference was statistically significant (χ2 = 25.7, p < 0.001).

4. Discussion

The present study sought to compare sub-groups of individuals with recent nonmedical use of prescription opioids, with a focus on differences between those with nonmedical use for pain relief purposes only and those with nonmedical use for reasons other than pain relief (e.g., to improve mood, to sleep better, or to relax), with or without use for pain relief. Aside from a few notable exceptions, reasons for nonmedical prescription opioid use have been largely understudied (Fischer & Rehm, 2008; Zacny & Lichtor, 2008), particularly in middle-aged and older adult populations. This is despite the elevated rate of negative consequences of nonmedical prescription opioid use among middle-aged and older adults compared to other age groups; for example, prescription opioid overdose risk is particularly elevated for middle-aged adults (ages 35-55) (Warner, Chen & Makuc, 2009).

We found that past-month nonmedical use for non-pain relief reasons was more common than use for pain relief only, which is consistent with at least two studies among adolescent and young adult school-based samples (McCabe, et al., 2007; McCabe, et al., 2009a; McCabe, et al., 2009b). Furthermore, heavy nonmedical use was more common in the group who had used for reasons other than pain relief compared to the group who had used for pain relief only. Those with nonmedical use for reasons other than pain relief also reported more extensive substance use, poorer mental health, and higher expectancies that opioids could help them cope with positive and negative emotions and experiences.

The finding that approximately 45% of all respondents in an addictions treatment setting reported recent nonmedical use of prescription opioids for reasons other than pain relief is of particular clinical concern. Although data on the prevalence of particular types of use from previous historical time periods were not available for analysis, this high prevalence may reflect the increases in nonmedical use of prescription opioids that have been observed in the U.S. population as a whole (Paulozzi, et al., 2006; Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration Office of Applied Studies, 2009). Reducing nonmedical use of prescription opioids may be particularly complex compared to other substances given the valid use of these substances for pain relief and the elevated levels of pain experienced among individuals with substance use disorders (Potter, Prather & Weiss, 2008; Rosenblum, Joseph, Fong, Kipnis, Cleland & Portenoy, 2003). Nonetheless, nonmedical use for reasons other than pain relief (e.g., to get high, to relax) may be best addressed through the same strategies used to approach use of other substances, such as alcohol and illicit drugs, because of the similarity in reason for use.

Although using for reasons other than pain management was more common than using only for pain management among those who had used opioids nonmedically, it is important to note that approximately 34% of nonmedical opioid users (and 23% of all residential addictions treatment patients surveyed) reported nonmedical use but did not report using for reasons other than pain management. Consequently, it may be inaccurate to assume that all nonmedical prescription opioid use is for reasons unrelated to pain among patients in addictions treatment. Regardless of the accuracy of this self-assessment of reason for use, talking to patients about their perceived reasons for nonmedical use of opioids may be important for conveying empathy and establishing a therapeutic alliance. For individuals who report nonmedical use of opioids for pain relief, a dialog about pain and pain-related coping may be clinically useful; however, the impact of pain-specific interventions in those in addictions treatment has not been systematically evaluated (Ilgen, Haas, Czyz, Webster, Sorrell & Chermack, 2011).

In this study of a sample of adults in a residential addictions treatment program, those individuals who had used for reasons other than pain relief were also more likely to report heavy nonmedical opioid use as well as recent nonmedical use of other controlled medications (specifically, sedatives and barbiturates) and street opioids/heroin, but not cannabis or cocaine. These findings suggest that individuals who use prescription opioids nonmedically and for nonpain relief purposes have greater substance use severity than individuals who use for pain relief only. Additionally, individuals in the present study who had used for reasons other than pain were more likely to report having had a non-fatal overdose and had poorer mental health. Collectively, these data provide further evidence that individuals who use opioids nonmedically for reasons other than pain relief constitute a group that at is particularly high risk for poor health outcomes.

We also found that those patients who had reported nonmedical prescription opioid use for non-pain relief reasons had higher pain medication expectancy scores across all three domains than individuals who used for pain relief only, including for the domain of pain reduction. Consistent with the finding that those individuals who had used for non-pain reasons were more likely to be heavy users and use other substances, the expectancy-related findings indicate that the individuals in this group are more likely to turn to prescription opioids for a variety of purposes, including physical pain relief, coping with other negative experiences, and for pleasure. Interestingly, there were no significant differences between groups across three measures of pain. Thus, assessment of pain level or pain conditions will not necessarily distinguish between individuals whose opioid use is strictly related to pain care and individuals who use at least some of the time for other reasons.

Those who had used opioids for reasons other than pain relief were also more likely to be female, to be Caucasian, and to be less than age 35 that those who had used opioids nonmedically but not for reasons other than pain relief in this sample. Prior research has demonstrated that women may have a more robust response to analgesics (Fillingim & Gear, 2004). The present findings highlight the need to understand gender differences in pain and opioid response and how these may result in differences in reasons for opioid use.

In our prior research describing the prevalence of nonmedical opioid use in this sample (Price, et al., 2011), opioid use than the single-item ASI question, which asks only about we found that the COMM ascertained a greater prevalence of prescription “non-prescribed” use. In the present study, participants who reported only nonmedical use for pain relief were significantly less likely than those who reported use for reasons other than pain relief to endorse the ASI item (12% vs. 45%). This finding suggests that individuals who use prescription opioids more than prescribed but for pain relief do not consider themselves to be engaging in “non-prescribed” use, interpreting “non-prescribed” to mean for reasons other than treating a medical condition. It is also possible that participants interpret “non-prescribed” to mean use of an opioid that was not prescribed directly to them by a doctor and that more of those who had used nonmedically but only used for pain relief had received their opioid medication from a doctor. In fact, there is evidence that nonmedical users motivated only by pain relief are significantly more likely to have been prescribed opioid medication from a doctor than those who report non-pain relief motives only (McCabe, et al., 2009a).

The present study has several limitations. Most crucial were limitations to the questions used to assess types of non-medical opioid use. While the COMM has the advantage of an established measure of nonmedical opioid use such as the ASI (Butler, et al., 2007) that likely has greater sensitivity to detecting non-medical opioid use in this sample than more traditional measures (Price, et al., 2011), no COMM questions directly assessed pain relief as a reason for nonmedical opioid use, and further research is needed to validate the measurement reason for use through these items. This study focused on the distinction between nonmedical use for pain relief and use for other reasons; additional distinctions may exist between individuals with specific type of non-pain relief motivations (e.g., using to “get high” vs. using to improve sleep) (Rigg & Ibanez, 2010), but these could not be readily differentiated with the items used in this study. Additionally, our measure of heavy opioid use was based on subjective reports of the frequency of use in specific situations from the COMM items because more objective frequency and quantity data were not available. Additional information on the initiation of nonmedical opioid use, such as whether medical use preceded nonmedical use, was not available from COMM items.

Data were cross-sectional and causal inferences are beyond the scope of this study. Consequently, our goal was to better understand the clinical profile of key sub-types of nonmedical prescription opioid users, rather than to disentangle causal relationships. As a result, we conducted multivariable analysis adjusting for only basic demographic characteristics, consistent with prior studies on motives for prescription medication use (Boyd, et al., 2006; McCabe, et al., 2009a; Rigg & Ibanez, 2010). Future research should include longitudinal data with larger samples to better elucidate causal processes related to type of use. All participants in this study were currently enrolled in a residential addictions treatment program and results may not generalize to other samples. The present study was also limited by the reliance on self-reported data of drug use behavior, although the high prevalence of nonmedical opioid use reported suggests that the participants were not strongly hindered by social desirability biases. This study focused on factors related to physical and mental health functioning and pain, and studies including additional measures of domains such as specific psychiatric comorbidities, personality, and DSM-IV substance use disorder symptom severity may further elucidate key differences between the sub-groups of interest.

4.1 Conclusions

Assessment of reasons for nonmedical prescription opioid use, in addition to prescription opioid use frequency, pain severity, and pain conditions, may aid appropriate pain treatment planning for individuals in addictions treatment. Nonmedical use of prescription opioids for reasons other than pain relief was common in this sample, and may signal an emerging and potentially critical issue in addictions treatment programs. Future research could explore how diversion behaviors, both obtaining opioids from a nonmedical source and sharing opioids obtained from a medical source with others, relates to motives for opioid use. The findings of the present study indicate those who use prescription opioids for pain relief only may have less severe substance use and mental health concerns than those who use for reasons other than pain relief, but additional treatment (beyond that traditionally incorporated in addictions settings) focused on pain may be helpful for individuals who are using opioids beyond their prescribed dose in order to treat their pain. Future research is needed to examine differences in success of addictions and pain management treatments between those whose nonmedical prescription opioid use is for reasons other than pain relief and those whose nonmedical use is for pain relief only.

Highlights.

• We examine nonmedical prescription opioid use among addictions treatment patients.

• We examine reasons for use: other than pain relief and only for self-treatment.

• Those with nonmedical use for other reasons had increased substance use severity.

• Those with nonmedical use for other reasons had poorer mental health functioning.

Acknowledgments

Role of Funding Source: The development of this article was supported by NIH grants R21DA026925, R01DA024678, and R01DA031160; CDA-09-204 from the Department of Veterans Affairs HSR&D and funding from the University of Michigan Department of Psychiatry. The fund ng agencies had no additional role in the study design, data collection, analysis and interpretation of the data, nor in the preparation and submission of the report, including the decision to submit.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errorsmaybe discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributors: All authors contributed to the conceptualization and design of the study analyses. Dr. Ilgen contributed to the design of the data collection. Dr. Bohnert was re ponsible for conducting analyses and Dr. Bohnert and Ms. Eisenberg shared responsibility for writing the first draft of the manuscript. Drs. Ilgen, Whiteside, McCabe, and Ms. Price provided substantive and conceptual feedback on all drafts.

Conflicts of Interest: All authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

References

- Beck AT, Steer RA, Ranieri WF. Scale for Suicide Ideation: Psychometric properties of a self-report version. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 1988;44:499–505. doi: 10.1002/1097-4679(198807)44:4<499::aid-jclp2270440404>3.0.co;2-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyd CJ, McCabe SE, Cranford JA, Young A. Adolescents’ motivations to abuse prescription medications. Pediatrics. 2006;118:2472–2480. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-1644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butler SF, Budman SH, Fernandez KC, Houle B, Benoit C, Katz N, et al. Development and validation of the Current Opioid Misuse Measure. Pain. 2007;130:144–156. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2007.01.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caldeiro RM, Malte CA, Calsyn DA, Baer JS, Nichol P, Kivlahan DR, et al. The association of persistent pain with out-patient addiction treatment outcomes and service utilization. Addiction. 2008;103:1996–2005. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2008.02358.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fillingim RB, Gear RW. Sex differences in opioid analgesia: clinical and experimental findings. Eur J Pain. 2004;8:413–425. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpain.2004.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer B, Rehm J. Nonmedical use of prescription opioids: Furthering a meaningful research agenda. Journal of Pain. 2008;9:490–493. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2008.03.002. discussion 494-496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fortuna RJ, Robbins BW, Caiola E, Joynt M, Halterman JS. Prescribing of controlled medications to adolescents and young adults in the United States. Pediatrics. 2010;126:1108–1116. doi: 10.1542/peds.2010-0791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ilgen MA, Haas E, Czyz E, Webster L, Sorrell JT, Chermack S. Treating chronic pain in Veterans presenting to an addictions treatment program. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice. 2011;18:149–160. [Google Scholar]

- Ilgen MA, Roeder KM, Webster L, Mowbray OP, Perron BE, Chermack ST, et al. Measuring pain medication expectancies in adults treated for substance use disorders. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2011;115:51–56. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2010.10.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerns RD, Turk DC, Rudy TE. The West Haven-Yale Multidimensional Pain Inventory (WHYMPI) Pain. 1985;23:345–356. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(85)90004-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9: Validity of a brief depression severity measure. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2001;16:606–613. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCabe SE, Cranford JA, Boyd CJ, Teter CJ. Motives, diversion and routes of administration associated with nonmedical use of prescription opioids. Addictive Behaviors. 2007;32:562–575. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2006.05.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCabe SE, Boyd CJ, Cranford JA, Teter CJ. Motives for nonmedical use of prescription opioids among high school seniors in the United States: Self-treatment and beyond. Archives of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine. 2009a;163:739–744. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2009.120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCabe SE, Boyd CJ, Teter CJ. Subtypes of nonmedical prescription drug misuse. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2009b;102:63–70. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2009.01.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLellan AT, Kushner H, Metzger D, Peters R, Smith I, Grissom G, et al. The Fifth Edition of the Addiction Severity Index. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 1992;9:199–213. doi: 10.1016/0740-5472(92)90062-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okie S. A flood of opioids, a rising tide of deaths. New England Journal of Medicine. 2010;363:1981–1985. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1011512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paulozzi LJ, Budnitz DS, Xi Y. Increasing deaths from opioid analgesics in the United States. Pharmacoepidemiology Drug Saf. 2006;15:618–627. doi: 10.1002/pds.1276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paulozzi LJ, Ryan GW. Opioid analgesics and rates of fatal drug poisoning in the United States. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2006;31:506–511. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2006.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pomazal RJ, Brown JD. Understanding drug use motivation: A new look at a current problem. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1977;18:212–222. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Potter JS, Prather K, Weiss RD. Physical pain and associated clinical characteristics in treatment-seeking patients in four substance use disorder treatment modalities. Am J Addict. 2008;17:121–125. doi: 10.1080/10550490701862902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price AM, Ilgen MA, Bohnert AS. Prevalence and correlates of nonmedical use of prescription opioids in patients seen in a residential drug and alcohol treatment program. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2011;41:208–214. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2011.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rigg KK, Ibanez GE. Motivations for non-medical prescription drug use: A mixed methods analysis. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2010;39:236–247. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2010.06.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenblum A, Joseph H, Fong C, Kipnis S, Cleland C, Portenoy RK. Prevalence and characteristics of chronic pain among chemically dependent patients in methadone maintenance and residential treatment facilities. JAMA. 2003;289:2370–2378. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.18.2370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Statacorp Stata Statistical Software. (version 10) 2008 [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse & Mental Health Services Administration Results from the 2009 National Survey on Drug Use and Health. Summary of National Findings. 2010;Volume I [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration Office of Applied Studies The NSDUH Report: Trends in Nonmedical Use of Prescription Pain Relievers: 2002 to 2007. 2009 [Google Scholar]

- Trafton JA, Oliva EM, Horst DA, Minkel JD, Humphreys K. Treatment needs associated with pain in substance use disorder patients: implications for concurrent treatment. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2004;73:23–31. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2003.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ware J, Jr., Kosinski M, Keller SD. A 12-Item Short-Form Health Survey: Construction of scales and preliminary tests of reliability and validity. Medical Care. 1996;34:220–233. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199603000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warner M, Chen L, Makuc DM. Increase in fatal poisonings involving opioid analgesics in the United States, 1999-2006. NCHS Data Brief, no. 22. 2009 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zacny J, Bigelow G, Compton P, Foley K, Iguchi M, Sannerud C. College on Problems of Drug Dependence taskforce on prescription opioid non-medical use and abuse: position statement. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2003;69:215–232. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(03)00003-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zacny JP, Lichtor SA. Nonmedical use of prescription opioids: Motive and ubiquity issues. Journal of Pain. 2008;9:473–486. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2007.12.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]