Abstract

Glucocorticoids are an important class of anti-inflammatory/immunosuppressive drugs. A crucial part of their anti-inflammatory action results from their ability to repress proinflammatory transcription factors such as nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB) and activator protein-1 (AP-1) upon binding to the glucocorticoid receptor (GR). Accordingly, sensor cells quantifying their effect on inflammatory signal-induced NF-κB activation can provide useful information regarding their potencies as well as their transrepression abilities. Here, we report results obtained on their effect in suppressing both the TNFα- and the CD40L-induced activation of NF-κB in sensor cells that contain an NF-κB–inducible SEAP construct. In these cells, we confirmed concentration-dependent NF-κB activation for both TNFα and CD40L at low nanomolar concentrations (EC50). Glucocorticoids tested included hydrocortisone, prednisolone, dexamethasone, loteprednol etabonate, triamcinolone acetonide, beclomethasone dipropionate, and clobetasol propionate. They all caused significant, but only partial inhibition of these activations in concentration-dependent manners that could be well described by sigmoid response-functions. Despite the limitations of only partial maximum inhibitions, this cell-based assay could be used to quantitate the suppressing ability of glucocorticoids (transrepression potency) on the expression of proinflammatory transcription factors caused by two different cytokines in parallel both in a detailed, full dose-response format as well as in a simpler single-dose format. Whereas inhibitory potencies obtained in the TNF assay correlated well with consensus glucocorticoid potencies (receptor-binding affinities, Kd, RBA, at the GR) for all compounds, the non-halogenated steroids (hydrocortisone, prednisolone, and loteprednol etabonate) were about an order of magnitude more potent than expected in the CD40 assay in this system.

Keywords: CD154, corticosteroids, Hill equation, TNF, transrepression

1. Introduction

Because of their potent antiinflammatory and immunosuppressive effects, glucocorticoids are one of the most widely used drug classes: they are commonly utilized in a variety of clinical diseases and are the drug of choice and the mainstay of therapy in many of them [1-4]. Their longtime and widespread use notwithstanding, details of their molecular mechanism of action started to emerge only during the last quarter of the past century [5-9], and several aspects remain to be clarified. These steroids exert their main effect by binding to glucocorticoid receptors (GRs), a member of the steroid-thyroid-retinoid receptor super-family [10, 11].

The physiological effects generated by drugs are, ultimately, a function of various properties that determine their overall absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion (ADME) as well as their ability to generate a response at their intended target(s). Among these properties, receptor-binding affinity (RBA) tends to be a major determining factor, and it is particularly so for glucocorticoids because GRs from different tissues and even from different species seem to be essentially the same. Consequently, relative RBAs (rRBAs; usually expressed as percent values with dexamethasone as reference set at 100%) are commonly used as a measure of glucocorticoid potency, and various in vitro and in vivo pharmacological properties tend to correlate closely with RBA. For example, RBA has been shown to be related to the clinical efficacy of inhaled glucocorticoids [12], to side effects such as cortisol suppression [13, 14], or to immunosuppressive potency [15]. We have shown that for inhaled corticosteroids, average recommended daily doses as well as their daily doses causing quantifiable cortisol suppression are closely correlated with rRBA if doses on a logarithmic scale (log 1/D) are represented as a function of the log rRBA values (as customary in quantitative structure-activity relationship, QSAR, studies) [16].

According to our current knowledge of the mechanism of action (see, e.g., [8]), the inactive GR is sequestered in the cytoplasm complexed with chaperones until it becomes an activated transcription factor upon binding to ligand. Glucocorticoids are lipophilic enough and can passively diffuse through the plasma membrane into the cytoplasm and bind to the GR with high affinity. Upon ligand binding, GR dissociates from the multimeric protein complex and translocates to the nucleus, where it will exert its effects via several mechanisms. The therapeutic success of glucocorticoids is largely attributed to their ability to reduce the expression of proinflammatory genes via activation of the GR and the concomitant inhibition of the activity of proinflammatory transcription factors, including nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB) and activator protein-1 (AP-1), through a mechanism called transrepression. During the last two decades, considerable research effort has been directed toward the identification of so-called dissociated glucocorticoids that can have limited transactivation through the glucocorticoid response element (GRE) mediated response, but are still able to transrepress transcription factors – mainly, NF-κB and/or AP-1 [17, 18].

Experimental GR binding affinities are typically obtained with rat cytosol preparations by determining the concentration (IC50) necessary to inhibit by 50% the binding of a given concentration of 3H-dexamethasone as radioligand. Depending on the assay, the binding affinity of dexamethasone (DEX) itself is usually somewhere in the range of 1–10 nM. Using a compilation of available published data, we have obtained Kd,DEX = 6.6 nM as a representative average and used this in our comprehensive review paper [16] to compare the RBA of a large number of glucocorticoids since, as mentioned, they are typically expressed as percent values relative to DEX (rRBA = Kd,DEX/Kd; rRBADEX = 100%). Availability of experimental assays to quantitatively evaluate the potency of glucocorticoids is critical, and it would be particularly preferable to have reliable cell-based assays to quantify the effect on NF-κB activation. These cell-based assays can also provide a better understanding of the complexities involved in glucocorticoid action. Along these lines, human lung carcinoma A549 cells transfected with NF-κB-responsive elements have been used in a few cases to estimate glucocorticoid activity [19-21].

Here, we report results obtained with seven representative glucocorticoids with a wide range of activity (hydrocortisone, prednisolone, dexamethasone, loteprednol etabonate, triamcinolone acetonide, beclomethasone dipropionate, and clobetasol propionate) in assays with sensor cells that can measure the TNFα- and CD40L-induced activations of NF-κB through an NF-κB–inducible secreted embryonic alkaline phosphatase (SEAP) construct. We are using these readily available cells as a standard cell-based model to assess ligand-induced receptor activation for selected members of the tumor necrosis superfamily (TNFSF) in our work focusing on small-molecule costimulatory modulation [22, 23]. Here, we evaluated the suitability of this model to quantitate glucocorticoid activity both in a detailed full dose-response format as well as in a single-dose format.

2. Experimental

2.1. Materials

All tested glucocorticoids as well as all chemicals and reagents used were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). The ligands used for stimulation in the cell assays (CD154 and TNFα; FLAG-tagged) were obtained from Axxora, LLC (San Diego, CA). Monoclonal anti-human CD154 (clone 40804) and anti-human TNFα antibodies (clone 1825) were purchased from R&D Systems (Minneapolis, MN).

2.2. Activation of CD40L sensor cells

HEK-Blue CD40L sensor cells that can serve to measure the bioactivity of CD40L via release of secreted embryonic alkaline phosphatase (SEAP) upon NF-κB activation following stimulation by CD40L (CD154) or TNFα were acquired from InvivoGen (San Diego, CA). This sensor cell line was generated by stable transfection of HEK293 cells with the human CD40 gene and an NF-κB-inducible SEAP construct, which consists of the SEAP reporter gene under the control of the IFN-β minimal promoter fused to five NF-κB (and five AP-1) binding sites. As before [23], cells were cultured and assayed for activation as recommended by the manufacturer. Briefly, the cells were cultivated in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle (DMEM) media supplemented with 4.5 g/L glucose, 10% v/v FBS, 50 U/mL penicillin, 50 μg/mL streptomycin, 100 μg/mL Normocin, and 2 mM l-glutamine. The cells were centrifuged and re-suspended in the same medium with 1% FBS, added to a 96-well microtiter plate at a density around 5 × 104 cells/well, and stimulated with TNF α (3 ng/mL) or CD40L (CD154, 25 ng/mL) diluted in the same media in the presence of different concentrations of the tested corticosteroids (0, 0.01, 0.1. 1.0, 10, 100, and 1000 nM; triplicates or quadruplicates per plate). After incubation with TNFα (20 h) or CD40L (30 h) at 37°C and 5% CO2, SEAP levels were determined by adding QUANTI-Blue™ reagent (InvivoGen) whose change in color intensity from pink to purple/blue is proportional to the enzyme’s activity. The level of SEAP was determined quantitatively using a spectrophotometer at 620–655 nm.

2.3. Data analysis

Data from five independent experiments (triplicates or quadruplicates for each condition) were normalized, converted to percent inhibition values, and analyzed with GraphPad Prism version 6 (GraphPad, San Diego, CA) using standard log inhibitor vs. response model with variable slopes (Hill equation). Since the bottom was restricted to zero, the model used for fitting was

| (1) |

with C being the concentration, Kd the binding (dissociation) constant, nH the Hill slope, and Emax the maximum response E (see also eq. A.1 in Appendix A). To obtain concentration-dependent (dose-response) curves for the glucocorticoids, their effects were expressed as percent suppression compared to stimulation alone and fitted with the standard model using Emax and nH values constrained across all data series.

3. Results

For the present evaluation of glucocorticoid effects on cytokine-induced NF-κB-activation, we used seven well-known corticosteroids of various potencies that are in clinical use: dexamethasone (DEX), hydrocortisone (HC), prednisolone (PRED), loteprednol etabonate (LE), triamcinolone acetonide (TA), beclomethasone dipropionate (BDP), and clobetasol propionate (CP). These test compounds cover about three orders of magnitude in potency as characterized by the commonly used relative receptor binding affinity (rRBA) at the glucocorticoid receptor (GR): from 10 for the least potent (HC) to 6300 for the most potent (CP) (Table 1) [16]. To assess activity, we used a readily available cell line that was generated by stable transfection of HEK293 cells with the human CD40 gene and an NF-κB-inducible SEAP construct (HEK-Blue CD40L; see Experimental section). These cells can measure the bioactivity of CD40L (CD154) via the amount of secreted embryonic alkaline phosphatase (SEAP) released upon NF-κB activation following CD40 stimulation. Binding of CD40L to its receptor (CD40) triggers a signaling cascade leading to the activation of NF-κB and the subsequent production of SEAP, which can be detected and quantified as described in the Experimental section. Because these cells express endogenously the receptors for IL-1β and TNFα, which share a common signaling pathway with CD40L, they also respond to IL-1β and TNFα stimulation.

Table 1.

Data from the two assays of the present study (median inhibitory concentrations, IC50s, and corresponding relative receptor binding affinities, rRBAs, for the TNFα- and the CD40L-induced NF-κB activation) compared to published [16] consensus estimates of glucocorticoid potencies (Kd,lit, rRBAlit).

| DEX | HC | PRED | LE | TA | BDP** | CP | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kd,lit [nM]* | 6.60 | 68.13 | 34.70 | 4.39 | 2.44 | 0.46 | 0.10 |

| TNFα, IC50 [nM] | 2.93 | 15.52 | 14.19 | 0.79 | 0.76 | 0.10 | 0.02 |

| CD40L, IC50 [nM] | 1.89 | 0.54 | 0.30 | 0.06 | 0.43 | 0.22 | 0.01 |

| rRBAlit* | 100.0 | 10.0 | 19.0 | 150.0 | 270.0 | 1440.0 | 6300.0 |

| rRBATNFα | 100.0 | 18.9 | 20.6 | 372.6 | 387.4 | 2952.7 | 13074.5 |

| rRBACD40L | 100.0 | 350.3 | 632.9 | 3357.0 | 442.1 | 872.2 | 13653.4 |

| CD40L/TNFα pot. | 1.55 | 28.75 | 47.49 | 13.96 | 1.77 | 0.46 | 1.62 |

Averaged of published values used as collected in ref. [16].

The Kd,lit and rRBAlit values used here for beclomethasone dipropionate (BDP; Kd 4.7 nM, rRBA 140), which is a prodrug, are those for beclomethasone 17-monopropionate (BMP; Kd 0.46 nM, rRBA 1440), its more active form resulting from hydrolytic metabolism that cleaves the corresponding 21-ester side chain.

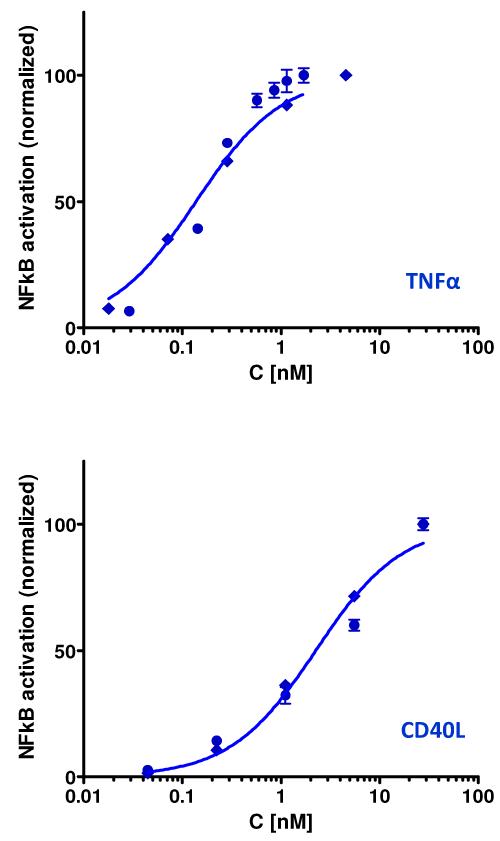

Stimulation of these sensor cells by TNFα and CD40L indeed produced NF-κB activation in a concentration-dependent (dose-responsive) manner that could be well fitted with a standard one-site specific binding model indicating median effective concentrations (EC50) of 0.14 nM (2.7 ng/mL) and 2.3 nM (41 ng/mL) for TNFα and CD40L, respectively (Figure 1). Conditions close to these EC50s were used in the subsequent activation assays to optimize the response (3 and 25 ng/mL for TNF α and CD40L, respectively). Both activations could be fully blocked by the corresponding anti-TNFα and anti-CD40L blocking antibodies (data not shown).

Figure 1.

Semi-log plots of the TNFα- and CD40L-induced NF-κB activations in the sensor cells of the present study quantified via SEAP (symbols) and fitted after normalization with standard one-site specific binding models (lines) indicating median effective (EC50) concentrations of 0.14 nM (2.7 ng/mL) and 2.3 nM (41 ng/mL) (top and bottom figures, respectively).

3.1. Effects on TNFα-induced activation

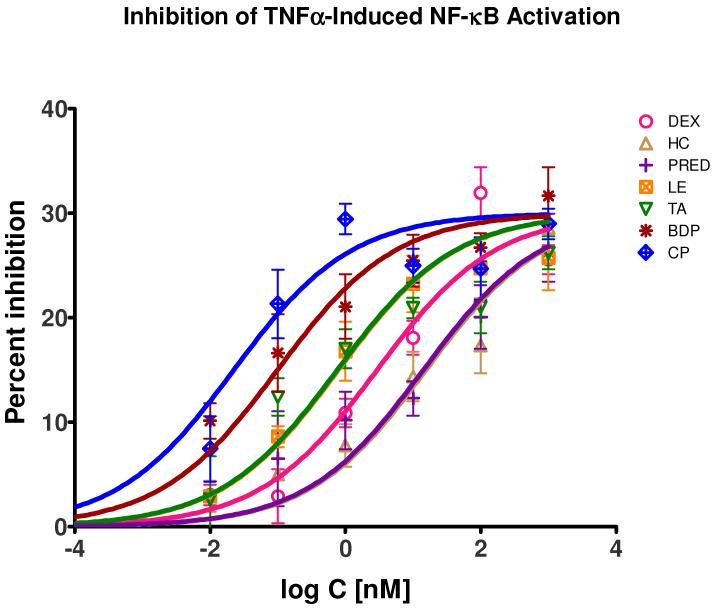

All tested glucocorticoids caused significant and concentration-dependent, but only partial inhibition of the TNFα-induced NF-κB activation. Data measured in detailed dose-response type assays were converted to percent inhibition values and could be fitted well with a standard binding model (eq. 1) using shared maximum (Emax = 30%) and Hill slope (nH = 0.5) parameters indicating typical concentration-dependent response (Figure 2). In this assay, glucocorticoids caused a maximum inhibition of around 30%. Data obtained with (6 h) or without drug pre-incubation did not show significant differences and were merged together. The median inhibitory concentration (IC50) values obtained from this fitting are in good agreement with published consensus values for GR affinities (Table 1). All compounds were about 3-to 5-fold more potent than expected based on the consensus GR Kd values, but the relative potencies with DEX as reference reflect existing rRBA estimates (Table 1). In this comparison (Table 1), for beclomethasone dipropionate (BDP; Kd 4.7 nM, rRBA 140), which is a prodrug, we used the GR potency estimate corresponding to beclomethasone 17-monopropionate (BMP; Kd 0.5 nM, rRBA 1400), which is the more active form resulting from the hydrolytic metabolism of BDP, as it gave much better fit. Esterases responsible for this metabolic transformation (BDP → BMP) are ubiquitously expressed [24, 25], and conversion of ester-type prodrugs to their active form has been shown in HEK cells [26] as well as in FBS media [27].

Figure 2.

Concentration-dependence of the percent suppression of the TNFα-induced NF-κB activation caused by selected glucocorticoids in sensor cells. Data are average of five independent experiments in triplicates or quadruplicates using TNFα stimulation (3 ng/mL) and were fitted by a standard specific binding model (eq. 1) with shared Emax and nH values. The corresponding median inhibitory concentration (IC50) values are summarized in Table 1, and they are in good agreement with published consensus Kd data [16] being about 3–5 fold lower here for all compounds.

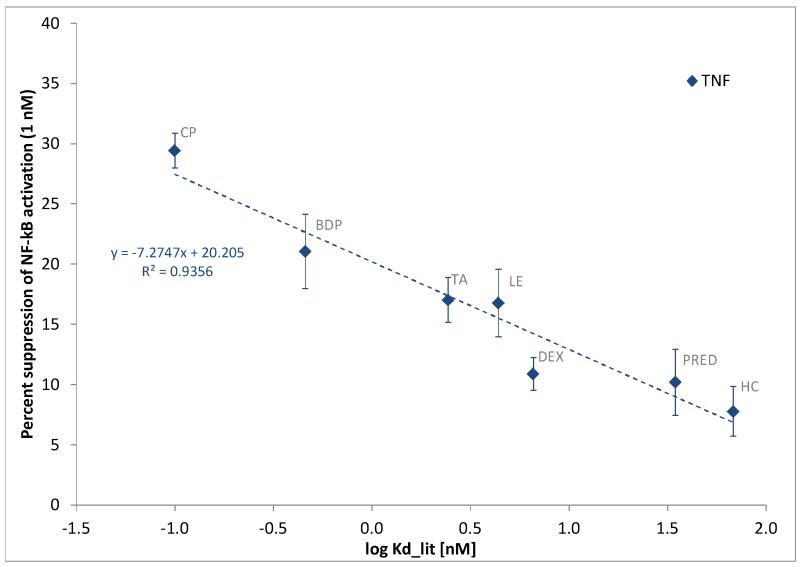

To evaluate whether a simplified assay design could provide useful rankings, we have also analyzed the percent suppression of TNFα-induced activation caused by the different test compounds used at a single fixed concentration. Figure 3 shows the percent suppression of the TNFα-induced NF-κB activation at a single (1 nM) glucocorticoid concentration as a function of decreasing glucocorticoid receptor affinity (log Kd, equivalent to a log rRBA scale). Using this type of analysis (justified by the theoretical considerations summarized in Appendix A), we found that the suppressive ability at 1 nM correlated well with the log-scaled receptor binding affinity (r2 = 0.94). Hence, this simplified assay format can by itself provide useful activity ranking information assuming an adequate test concentration is used (i.e., one that is in the range of the Kd values of the test compounds; see Appendix A).

Figure 3.

Percent suppression of the TNFα-induced NF-κB activation caused by glucocorticoids at 1 nM concentration as a function of consensus glucocorticoid receptor affinity (log Kd, equivalent to the log of the commonly used relative receptor binding affinity, rRBA, scales). Data are average of five independent experiments in quadruplicates using TNFα stimulation in the presence of the listed glucocorticoids (1 nM).

3.2. Effects on CD40L-induced activation

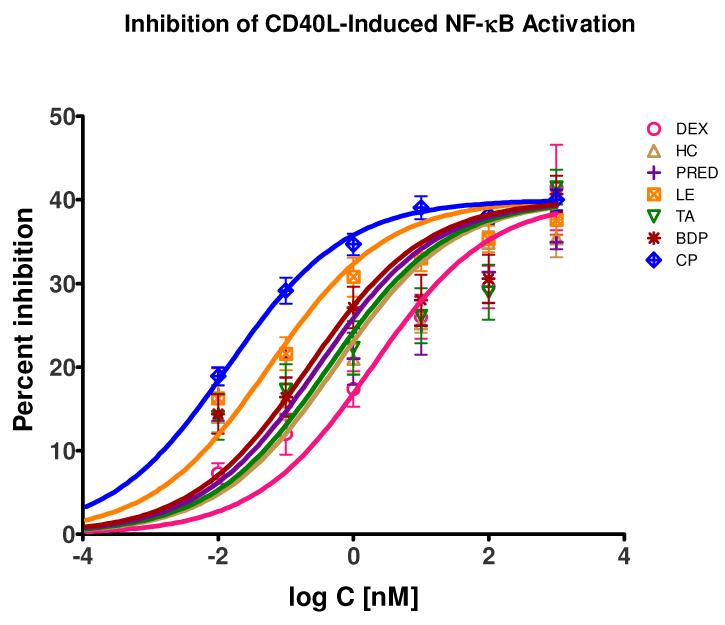

In a manner similar to that used for the TNFα-caused activation, we also tested the effects of the present glucocorticoids on CD40L-induced activation in these sensor cells. Again, all tested glucocorticoids caused significant and concentration-dependent, but only partial inhibition of the CD40L-induced NF-κB activation. Just as before, the inhibition data obtained in detailed dose-response type assays and converted to percent inhibition values could be fitted well with the same standard binding model (eq. 1) using shared maximum (Emax = 40%) and Hill slope (nH = 0.5) parameters (Figure 4). The maximum inhibition in this assay system was around 40%, somewhat more pronounced than in the TNF system (where it was around 30%). The Hill slopes seemed slightly lower, but the same value as before (nH = 0.5) was enforced. Interestingly enough, whereas four compounds (DEX, TA, BDP, and CP) showed similar inhibitory potencies to those from the TNF assay (with very close, maybe slightly less IC50 values), three compounds (HC, PRED, and LE) showed considerably, about 20-to 30-fold, increased potencies in inhibiting the CD40L-induced vs. the TNFα-induced NF-κB activation in these cells (Table 1 and Figure 2 cf. Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Concentration-dependence of the percent suppression of the CD40L-induced NF-κB activation caused by selected glucocorticoids in sensor cells. Data are average of five independent experiments in triplicates or quadruplicates using CD40L stimulation (25 ng/mL) and were fitted by a standard specific binding model (eq. 1) with shared Emax and nH values.

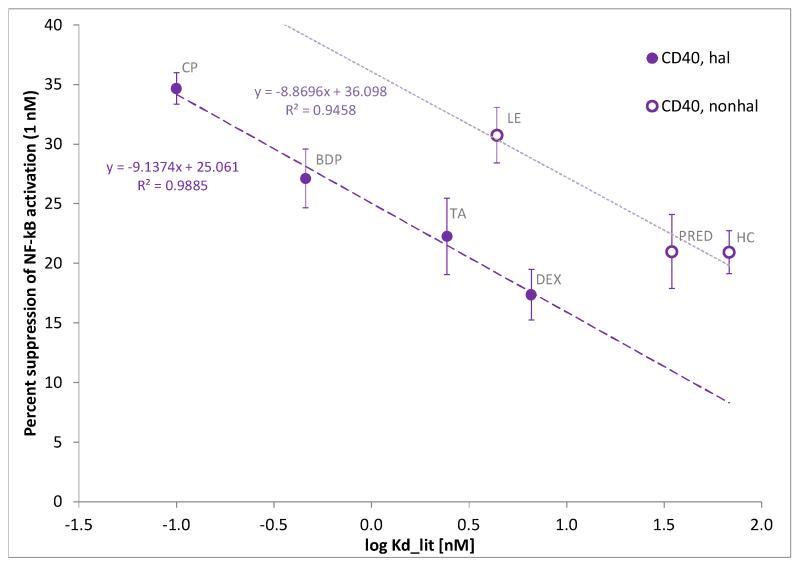

This is also evident in Figure 5 that shows the percent suppression of the CD40L-induced NF-κB activation obtained here at a single (1 nM) glucocorticoid concentration as a function of consensus log Kd values in a manner similar to Figure 3. Whereas the same linear relationship is clearly present for four compounds (DEX, TA, BDP, and CP; r2 = 0.99), three others clearly showed a similar trend, but an enhanced inhibitory activity. Notably, these three (HC, PRED, and LE) are non-halogenated steroids while the other four are all halogenated steroids with fluorine or chlorine substituents at the 9-position of the steroid framework.

Figure 5.

Percent suppression of the CD40L–induced NF-κB activation caused by glucocorticoids at 1 nM concentration as a function of consensus glucocorticoid receptor affinity (log Kd, equivalent to the log of the commonly used relative receptor binding affinity, rRBA, scales). Data are average of five independent experiments in quadruplicates using CD40L stimulation in the presence of the listed glucocorticoids (1 nM). Data for the three non-halogenated (HC, PRED, and LE) and the four halogenated steroids (DEX, TA, BDP, and CP) were fitted with different trend-lines.

4. Discussion

While both TNFα and CD40L act along similar pathways to activate NF-κB in the sensor cells used here, the response to TNFα is about an order of magnitude more sensitive than the one to CD40L (EC50s of approximately 0.1 vs. 2.0 nM; i.e., 3 vs. 40 ng/mL; Figure 1). This is in agreement with our previous results from cell-free binding assays indicating that the binding of these trimeric TNFSF ligands (TNFα and CD40L) to their respective receptors (TNF-R1 and CD40) takes place with low nanomolar affinity and is stronger for TNFα – TNF-R1 (Kd ≈ 0.5 nM) than for CD40L – CD40 (Kd ≈ 1.0 nM) [22, 28].

All glucocorticoids tested were able to cause concentration-dependent inhibition of both the TNFα- and the CD40L-induced NF-κB activations in a manner that could be well described by Hill-type sigmoid dose-response functions (eq. 1) (Figure 2, Figure 4), but maximum inhibitions were only about 30% and 40%, respectively. This somewhat limits the utility of these assays as more pronounced inhibition would allow more reliable and more sensitive quantitation. However, as illustrated by the results of the single-dose comparisons (Figure 3, Figure 5), these sensor cells still can provide sufficiently meaningful rankings of glucocorticoid activity even in a simplified assay design to be useful, for example, for preliminary screening purposes. Indeed, repression of TNFα-stimulated NF-κB activation in human lung carcinoma A549 cell line stably transfected with a plasmid containing an NF-κB-responsive ELAM (E-selectin) promoter sequence upstream of a SEAP reporter gene has been used as an estimator of GR binding by GSK researchers to evaluate the potency of their novel proprietary glucocorticoids [20, 21]. In a different setting, A549 cells stably transfected with a reporter plasmid containing an AP-1, NF-κB, and GRE induced SEAP gene were exposed to a panel of concentrations of nine glucocorticoids to evaluate transrepression and transactivation potencies [19]. However, these cells were already activated by the presence of fetal bovine serum (FBS) in the media. In these cells, the average maximal inhibition of AP-1 and NF-κB activity from baseline was also only about 40% [19]. Inhibition of NF-κB activation by glucocorticoids in Jurkat human T-cell leukemia lines seems to require transfection with GR [29]. Using the glucocorticoids tested here, we did not observe any quantifiable inhibition in Jurkat-Dual cells (InvivoGen) transfected in a similar manner to allow the monitoring of NF-κB activation (via a Lucia luciferase reporter) as well as that of the interferon regulatory factor (IRF) (via a SEAP reporter) (data not shown).

Typically, chronic inflammatory diseases involve the infiltration and activation of various inflammatory and immune cells, which then release inflammatory mediators to modulate structural cells at the site of inflammation. For most of these inflammatory proteins, their increased expression is regulated at the level of gene transcription through the activation of pro-inflammatory transcription factors (such as NF-κB and AP-1) that play critical roles in amplifying and perpetuating the inflammatory process. Glucocorticoids are widely used powerful drugs because they can inhibit all stages of the inflammatory response. As discussed briefly in the introduction, they exert their main effects via binding to the intracellular GR that upon binding translocates to the nucleus and modulates various gene expressions. Unbound GR is associated within the cytoplasm in an inactive oligomeric complex with several regulatory proteins as reviewed, for example, in [8]. Upon activation, GR translocates to the nucleus and binds as a dimer to DNA by targeting glucocorticoid response elements (GREs) or negative GREs (nGREs). This results in either the activation or the repression of genes containing GR-binding sites.

More important from the perspective of the present model is that glucocorticoids can also cause negative modulation of gene transcription through transrepression mechanisms. These are mediated by inhibitory influences that GR exerts on the functions of several transcription factors. Transrepression is thought to be due at least in part to direct physical interactions between GR and transcription factors such as c-Jun–c-Fos and NF-κB. GR can interact as a monomer via direct protein-protein interactions (PPIs) with NF-κB as well as AP1 resulting in a mutual repression that prevents both GR and the other transcription factors from binding to their respective DNA response elements. Furthermore, GR can also repress the NF-κB–mediated activation of proinflammatory genes via PPI with NF-κB bound at these genes [8, 30].

Because transrepression is generally thought to be the main mechanism behind the (beneficial) anti-inflammatory actions of glucocorticoids, considerable effort was spent to identify dissociated glucocorticoids, i.e., selective GR modulators that can have limited transactivation via GRE, but still can transrepress transcription factors [17, 18]. Lately, there has been increasing skepticism as it is becoming increasingly clear that transactivation versus transrepression characteristics are cell type and gene specific and, therefore, highly context dependent [17]. The present cell-based model with an NF-κB-inducible read-out can provide a valuable tool to quantify transrepression potencies.

NF-κB is a ubiquitous transcription factor involved in inflammatory disorders. In its inactive form, it is maintained in the cytoplasm through its interaction with the inhibitor IκB. NF-κB activation is induced by a wide variety of stimuli including proinflammatory cytokines, such as IL-1 and TNF, as well as byproducts of microbial and viral infections, such as lipopolysaccharides and dsRNA, respectively. These lead to activation of IκB kinase (IKK), which then phosphorylates IκB. This then causes NF-κB to translocate to the nucleus and activate the transcription of various inflammatory genes, including cytokines and enzymes associated with the synthesis of inflammatory mediators. The exact mechanism of how GR represses NF-κB is still not fully clarified. One possibility is that physical interaction between GR and NF-κB sequesters NF-κB inhibiting its binding to DNA, but there are also indications that NF-κB dissociation from DNA is not required [8]. GR can repress AP-1 through some of the same mechanisms by which it represses NF-κB including direct PPI between GR and the c-Jun subunit; however, these mechanisms are even less well understood [8]. Nevertheless, these mechanisms are behind the glucocorticoid-mediated inhibition of various inflammatory cytokines (e.g., IL-6, IL-1β, and TNFα), enzymes (e.g., iNOS, COX-2, and MMPs), and adhesion molecules (e.g., ICAM-1, VCAM, and E-selectin) that all have one or more NF-κB and/or AP-1 elements in their gene promoters [17]. Glucocorticoids also have to exert actions downstream of the binding of proinflammatory transcription factors to DNA as, for example, treatment with high doses of inhaled corticosteroids to suppress airway inflammation in asthmatic patients is not associated with any reduction in NF-κB binding to DNA, yet it is able to switch off inflammatory genes regulated by NF-κB [9]. Therefore, there is increasing attention focused on glucocorticoid effects on chromatin structure and histone acetylation [9]. The fact that glucocorticoids can cause only a limited (30–40%) inhibition of the cytokine-induced activation in the present assay that uses a NF-κB–inducible SEAP construct as readout seems to further bolster the case for the argument that a significant part of the overall glucocorticoid action has to take place downstream from the binding of proinflammatory transcription factors to DNA.

Notably, whereas inhibitory potencies obtained here for all compounds showed activity in agreement with their consensus GR binding affinities (Kd, RBAlit) in the inhibition of the TNFα-induced activation (rRBATNFα; Table 1), all non-halogenated glucocorticoids tested (hydrocortisone, prednisolone, and loteprednol etabonate) were about an order of magnitude more potent than expected in inhibiting the CD40L-induced activation in this assay system. The increased activity of non-halogenated vs. halogenated steroids is evident both in the corresponding IC50 (and rRBACD40L) values (Table 1, last row) as well as in the results of the single-dose assays as presented in Figure 5. Even if these HEK293-based sensor cells were transfected to express the receptor for CD40L while they express the receptor for TNFα endogenously, this was somewhat unexpected, as all these effects should be mediated via binding to the same GR and the mechanisms of action along the two pathways activated by TNF-R and CD40, respectively are quite similar.

It has been long known that glucocorticoid activity is improved by 6α- or 9α-halogenation (mainly fluorination) and by introduction of cyclic 16,17-acetal moieties [3, 31]. In our previous molecular-size based quantitative analysis of GR binding, we found RBA to be increased in average about seven-fold by 6α/9α-halogenation or introduction of a cyclic 16,17-acetal moiety [16]. Interestingly, it is still unclear why does such 6α- or 9α-halogenation increase glucocorticoid activity so significantly, especially considering that the H → F replacement is a classic isosteric replacement often used in medicinal chemistry to provide metabolic stability because of the combination of steric similarity between H and F and the stability of the C–F bond [32]. The crystal structure of the DEX–GR complex does not seem to indicate the presence of any special interactions at these halogenation sites [16, 33]. The in vitro immunosuppressive potency of several glucocorticoids investigated using a whole-blood lymphocyte proliferation assay indicated no unexpected activity for non-halogenated compounds as potency estimates were fully in line with consensus rRBA values [15]. Nevertheless, the present results could still be an indication that nonhalogenated glucocorticoids possess a somewhat increased suppressive ability of costimulatory immune activity compared to that expected on the basis of their GR RBA value, and it might be one possible explanation, for example, for the success of the nonhalogenated prednisolone as a widely used immunosuppressive agent despite its relatively low GR rRBA (≈20% of dexamethasone; Table 1).

In summary, we have shown glucocorticoids of a wide range of potency to cause concentration-dependent inhibitions of both the TNFα- and the CD40L-induced NF-κB activation in readily available sensor cells. This cell-based quantitative assay could be used to quantitate the ability of glucocorticoids to suppress the expression of proinflammatory transcription factors such as NF-κB both in a detailed, full dose-response format to estimate IC50 values as well as in a simplified, single-dose format to obtain a ranking order. To our knowledge, inhibitory activities on CD40L-induced response have not been assessed before. Whereas halogenated steroids showed about similar potency in inhibiting TNFα- and CD40L-induced activation, non-halogenated steroids seem to be about an order of magnitude more potent in inhibiting the CD40L-induced than the TNFα-induced activation in this assay system.

Highlights.

Cell-based assay used to quantitate glucocorticoid activity (transrepression potency)

Inhibitory activity on cytokine-induced NF-κB activation is assessed

Inhibitory activity can be assessed in parallel for TNFα and CD40L induced response

Sigmoid-type concentration-dependent inhibition confirmed for all steroids tested

Non-halogenated steroids were found more potent than expected in the CD40 assay

Acknowledgement

Parts of this work were supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (1R01AI101041-01; PI: P. Buchwald), the Juvenile Diabetes Research Foundation (17-2012-361), and the Diabetes Research Institute Foundation.

Appendix A. Rationale for linearity in semi-log plot of fraction effect (f = E/Emax) vs. potency (log Kd)

We will assume that the effect produced follows a regular Hill-type response function (i.e., a general Clark-type equation) as commonly used in pharmacology models [34-36]. Accordingly, the fractional (normalized) effect, f = E/Emax, can be written as a function of drug concentration C (or as a function of C/Kd for a dimensionless form) as:

| (A.1) |

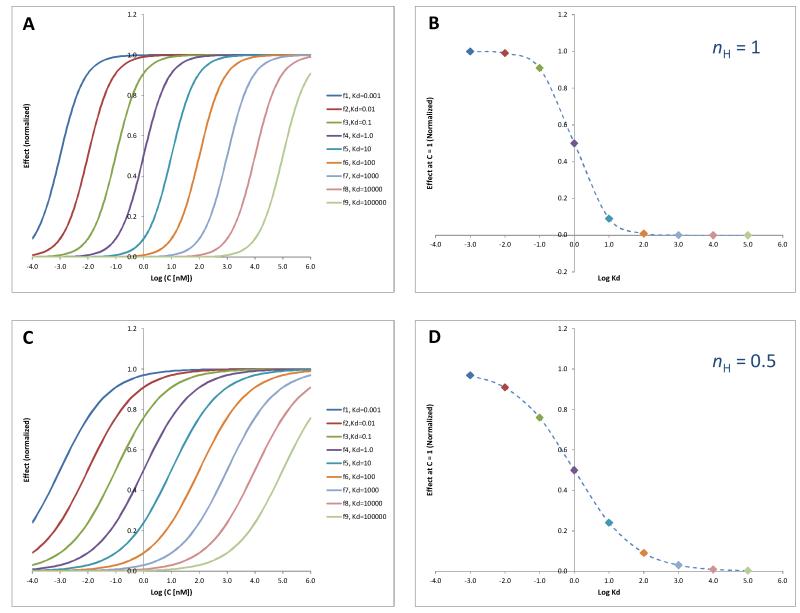

When represented on a semi-log scale, this results in the well-known sigmoid shape with an inflection point at the concentration causing half-maximal effect, which is equal to the dissociation constant Kd, and a transition width, which is characterized by the Hill slope, nH (see Figure A.1A below). With this simplified model that does not incorporate efficiencies, compounds of different potencies are characterized by different Kd values so that the response curves are shifted to the right as the potencies decrease (Kds increase).

Figure A.1.

(A) Normalized effects produced by compounds of different potencies in the same assay system that is assumed to follow a typical Hill-type response function with unity Hill slope (eq. A.1, nH = 1) shown as a classic concentration-dependent response on a semi-log scale. (B) Normalized effects produced by the compounds of different potencies from A used at a single test concentration (here, Ct = 1) shown this time as a function of log Kd. The effects used here corresponds to the intersection of the various curves with the vertical axis in A. (C) and (D) are the same as A and B, respectively, but for a system with a less abrupt response function (i.e., a lower Hill slope, nH = 0.5).

Here, we are interested in the relationship between the percent effects produced in the same system by different compounds that are all used at the same fixed test concentration Ct (e.g., Ct = 1 nM) and the potencies of these compounds (i.e., ft = E/Emax produced by different compounds at a fixed Ct concentration as a function of the Kd values). With a rearrangement of eq. A.1 above, it is apparent that this, in fact, will also be a sigmoid function on Kd, (or of Kd/Ct for a dimensionless form), just as it is on C, but with a slope of –nH:

| (A.2) |

Accordingly, the less potent a compound is (the larger Kd), the less response it produces – corresponding to Figure A.1B. From here it is also easy to notice, that for a regular response function having a unity Hill slope, nH = 1, the response is quasi-linear for about two orders of magnitude around the inflection point, which corresponds to Kd = Ct. For more or less abrupt response functions (nH > 1 or nH < 1), the width of the linear region is increasingly narrower or wider, respectively. An illustration for nH = 0.5 (a value similar to the one used in the fitting for the present assays) is included in Figure A.1C and D to illustrate that, in this case, the quasi-linear portion extends to about two orders of magnitude on each side of Ct.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- [1].Schimmer BP, Parker KL. Adrenocorticotropic hormone; adrenocortical steroids and their synthetic analogs; inhibitors of the synthesis and actions of adrenocortical hormones. In: Hardman JG, Limbird LE, editors. Goodman & Gilman’s The Pharmacological Basis of Therapeutics. McGraw-Hill; New York: 1996. pp. 1459–85. [Google Scholar]

- [2].Barnes PJ. Therapeutic strategies for allergic diseases. Nature. 1999;402(Suppl.):B31–B8. doi: 10.1038/35037026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Avery MA, Woolfrey JR. Anti-inflammatory steroids. In: Abraham DJ, editor. Burger’s Medicinal Chemistry and Drug Discovery Vol 3, Cardiovascular Agents and Endocrines. 6th Edition Wiley; Hoboken, NJ: 2003. pp. 747–853. [Google Scholar]

- [4].Bodor N, Buchwald P. Corticosteroid design for the treatment of asthma: structural insights and the therapeutic potential of soft corticosteroids. Curr Pharm Des. 2006;12:3241–60. doi: 10.2174/138161206778194132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Hollenberg SM, Weinberger C, Ong ES, Cerelli G, Oro A, Lebo R, et al. Primary structure and expression of a functional human glucocorticoid receptor cDNA. Nature. 1985;318:635–41. doi: 10.1038/318635a0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Baraniuk JN. Molecular actions of glucocorticoids: an introduction. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1996;97:141–2. doi: 10.1016/s0091-6749(96)80213-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Barnes PJ. Molecular mechanisms of corticosteroids in allergic diseases. Allergy. 2001;56:928–36. doi: 10.1034/j.1398-9995.2001.00001.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Smoak KA, Cidlowski JA. Mechanisms of glucocorticoid receptor signaling during inflammation. Mech Ageing Dev. 2004;125:697–706. doi: 10.1016/j.mad.2004.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Barnes PJ. How corticosteroids control inflammation: Quintiles Prize Lecture 2005. Br J Pharmacol. 2006;148:245–54. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0706736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Kumar R, Thompson EB. The structure of the nuclear hormone receptors. Steroids. 1999;64:310–9. doi: 10.1016/s0039-128x(99)00014-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Lu NZ, Wardell SE, Burnstein KL, Defranco D, Fuller PJ, Giguere V, et al. International Union of Pharmacology. LXV. The pharmacology and classification of the nuclear receptor superfamily: glucocorticoid, mineralocorticoid, progesterone, and androgen receptors. Pharmacol Rev. 2006;58:782–97. doi: 10.1124/pr.58.4.9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Rohdewald PJ. Comparison of clinical efficacy of inhaled glucocorticoids. Arzneim-Forsch/Drug Res. 1998;48(II):789–96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Derendorf H, Hochhaus G, Meibohm B, Möllmann H, Barth J. Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of inhaled corticosteroids. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1998;101:S440, S6. doi: 10.1016/s0091-6749(98)70156-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Rohatagi S, Arya V, Zech K, Nave R, Hochhaus G, Jensen K, et al. Population pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of ciclesonide. J Clin Pharmacol. 2003;43:365–78. doi: 10.1177/0091270002250998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Mager DE, Moledina N, Jusko WJ. Relative immunosuppressive potency of therapeutic corticosteroids measured by whole blood lymphocyte proliferation. J Pharm Sci. 2003;92:1521–5. doi: 10.1002/jps.10402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Buchwald P. Glucocorticoid receptor binding: a biphasic dependence on molecular size as revealed by the bilinear LinBiExp model. Steroids. 2008;73:193–208. doi: 10.1016/j.steroids.2007.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].De Bosscher K, Haegeman G. Minireview: latest perspectives on antiinflammatory actions of glucocorticoids. Mol Endocrinol. 2009;23:281–91. doi: 10.1210/me.2008-0283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].De Bosscher K, Vanden Berghe W, Haegeman G. The interplay between the glucocorticoid receptor and nuclear factor-kappaB or activator protein-1: molecular mechanisms for gene repression. Endocr Rev. 2003;24:488–522. doi: 10.1210/er.2002-0006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Dirks NL, Li S, Huth B, Hochhaus G, Yates CR, Meibohm B. Transrepression and transactivation potencies of inhaled glucocorticoids. Pharmazie. 2008;63:893–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Salter M, Biggadike K, Matthews JL, West MR, Haase MV, Farrow SN, et al. Pharmacological properties of the enhanced-affinity glucocorticoid fluticasone furoate in vitro and in an in vivo model of respiratory inflammatory disease. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2007;293:L660–L7. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00108.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Uings I, Needham D, Matthews J, Haase M, Austin R, Angell D, et al. Discovery of GW870086: A potent anti-inflammatory steroid with a unique pharmacological profile. Br J Pharmacol. 2013;169:1389–403. doi: 10.1111/bph.12232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Margolles-Clark E, Umland O, Kenyon NS, Ricordi C, Buchwald P. Small molecule costimulatory blockade: organic dye inhibitors of the CD40-CD154 interaction. J Mol Med. 2009;87:1133–43. doi: 10.1007/s00109-009-0519-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Ganesan L, Buchwald P. The promiscuous protein binding ability of erythrosine B studied by metachromasy (metachromasia) J Mol Recognit. 2013;26:181–9. doi: 10.1002/jmr.2263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Satoh T, Hosokawa M. Structure, function and regulation of carboxylesterases. Chem Biol Interact. 2006;162:195–211. doi: 10.1016/j.cbi.2006.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Buchwald P. Structure-metabolism relationships: steric effects and the enzymatic hydrolysis of carboxylic esters. Mini-Rev Med Chem. 2001;1:101–11. doi: 10.2174/1389557013407403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Zhou G, Marathe GK, Willard B, McIntyre TM. Intracellular erythrocyte platelet-activating factor acetylhydrolase I inactivates aspirin in blood. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:34820–9. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.267161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Mathew MP, Tan E, Shah S, Bhattacharya R, Adam Meledeo M, Huang J, et al. Extracellular and intracellular esterase processing of SCFA-hexosamine analogs: implications for metabolic glycoengineering and drug delivery. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2012;22:6929–33. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2012.09.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Ganesan L, Margolles-Clark E, Song Y, Buchwald P. The food colorant erythrosine is a promiscuous protein-protein interaction inhibitor. Biochem Pharmacol. 2011;81:810–8. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2010.12.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Auphan N, DiDonato JA, Rosette C, Helmberg A, Karin M. Immunosuppression by glucocorticoids: inhibition of NF-kappa B activity through induction of I kappa B synthesis. Science. 1995;270:286–90. doi: 10.1126/science.270.5234.286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Nissen RM, Yamamoto KR. The glucocorticoid receptor inhibits NFkappaB by interfering with serine-2 phosphorylation of the RNA polymerase II carboxy-terminal domain. Genes Dev. 2000;14:2314–29. doi: 10.1101/gad.827900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Wolff ME, Baxter JD, Kollman PA, Lee DL, Kuntz ID, Bloom E, et al. Nature of steroid-glucocorticoid receptor interactions: thermodynamic analysis of the binding reaction. Biochemistry. 1978;17:3201–8. doi: 10.1021/bi00609a005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Wermuth CG. Molecular variations based on isosteric replacements. In: Wermuth CG, editor. The Practice of Medicinal Chemistry. Academic Press; London: 1996. pp. 203–37. [Google Scholar]

- [33].Bledsoe RK, Montana VG, Stanley TB, Delves CJ, Apolito CJ, McKee DD, et al. Crystal structure of the glucocorticoid receptor ligand binding domain reveals a novel mode of receptor dimerization and coactivator recognition. Cell. 2002;110:93–105. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00817-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Jenkinson DH. Classical approaches to the study of drug-receptor interactions. In: Foreman JC, Johansen T, editors. Textbook of Receptor Pharmacology. CRC Press; Boca Raton, FL: 2003. pp. 3–80. [Google Scholar]

- [35].Kenakin TP. A Pharmacology Primer: Theory, Applications, and Methods. Academic Press; San Diego, CA: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- [36].Bodor N, Buchwald P. Wiley; Hoboken, NJ: 2012. Retrometabolic Drug Design and Targeting. [Google Scholar]