Humans have the ability to engage in prospective imagery to anticipate the future consequences of present behaviors (Suddendorf & Busby, 2005), but we often let our desire for immediate gratification lead us to devalue larger future consequences in favor of smaller immediate rewards. Discounting large future rewards in favor of smaller immediate rewards is known as delay discounting and increases with greater temporal distance between the rewards (Bickel & Marsch, 2001). One approach to reducing delay discounting is episodic future thinking (Atance & O'Neill, 2001). Episodic future thinking engages the episodic memory in prospectively experiencing future events (Atance & O'Neill, 2001; Schacter, Addis, & Buckner, 2007) and activates brain regions involved in prospective thinking (Benoit, Gilbert, & Burgess, 2011; Schacter et al., 2007). Episodic future thinking during intertemporal decision making reduces delay discounting, with the vividness of prospective imagery predicting the degree of the reduction (Peters & Büchel, 2010).

The inability to delay gratification is related to obesity (Davis, Patte, Curtis, & Reid, 2010; Francis & Susman, 2009; Weller, Cook, Avsar, & Cox, 2008). Delay discounting predicts intake of energy-dense convenience foods in obese women (Appelhans et al., 2012), and poor impulse control predicts a lack of success in weight loss (Best et al., 2012). To determine episodic future thinking's effect on impulsive behavior, we assessed whether episodic future thinking, compared with engagement in a control imagery task, reduced impulsivity and energy intake in overweight and obese individuals.

Method

Twenty-six overweight or obese (body mass index ≥ 25) women (mean age = 26.43 years, SD = 5.70; average body mass index = 30.99, SD = 5.80; 81% White, 19% racial-ethnic minority; 46% with at least some college education, 54% with no college education) participated in return for $25. Participants were randomly assigned to an episodic-future-thinking (n = 14) or control-episodic-thinking (n = 12) condition. To be included in the study, participants had to have endorsed at least one item on the Three-Factor Eating Questionnaire (Allison, Kalinsky, & Gorman, 1992) rigid-restraint scale, which ensured that they had a desire to control their food intake.

We had participants in each condition generate cues for episodic thinking during delay discounting and ad libitum eating, using an adapted version of a task for assessing the anticipation of future events in depressed individuals (MacLeod, Pankhania, Lee, & Mitchell, 1997). Episodic-future-thinking participants listed possible positive future events (D'Argembeau & Van der Linden, 2004) occurring at time periods corresponding to time periods specified in the delay-discounting task. The control- episodic-thinking group based episodic cues on vivid events described in entries of the travel blog of a female writer (http://almostfearless.com) posted between January 22 and February 13, 2012. Thus, control-episodic-thinking participants engaged imaging a recently experienced event. Participants rated the events on 6-point scales to identify events with the highest imagery (Peters & Büchel, 2010); once identified, participants’ reports of these events were audio recorded. The audio recordings were then used as episodic-thinking cues.

Discounting of hypothetical monetary rewards (of $10 and $100) were assessed at delays of 1 day, 2 days, 1 week, 2 weeks, 1 month, 6 months, and 2 years. Participants chose either the larger reward, available at a delay, or the smaller reward, available immediately, adjusted in 26 steps (26 choices between different combinations of immediate and delayed rewards, based on a standardized procedure commonly used in studies on delay discounting; Rollins, Dearing, & Epstein, 2010). Prior to each delay-discounting trial, episodic-future-thinking participants were instructed to think about future events corresponding to the delayed time period (Peters & Büchel, 2010), whereas control- episodic-thinking participants were instructed to think about events described in the travel blog. Indifference points (delays at which participants were equally likely to choose either immediate or delayed rewards) were calculated (Dixon, Marley, & Jacobs, 2003) to compute area-under-the-indifference-curve values (Myerson, Green, & Warusawitharana, 2001).

The ad libitum eating task simulated a food-related situation that could trigger impulsive eating, with sessions scheduled at least 90 min after lunch but before dinner. To increase food craving and temptation to eat (Fedoroff, Polivy, & Herman, 2003), we first had participants rate the sensory appeal of meatballs, fries, sausages, garlic bread, cookies, and dips without tasting them. Unlimited access to the foods was provided for 15 min afterward, and participants provided ratings of the foods’ taste quality and texture. The timing of the task and the sensory pre-exposure to the foods provided a prototypical situation that could lead participants to engage in consumption for immediate gratification instead of delaying gratification for future health. To cue episodic thinking during the taste test, we played the audio recordings of participants’ reports of high-imagery events throughout the eating task.

Results

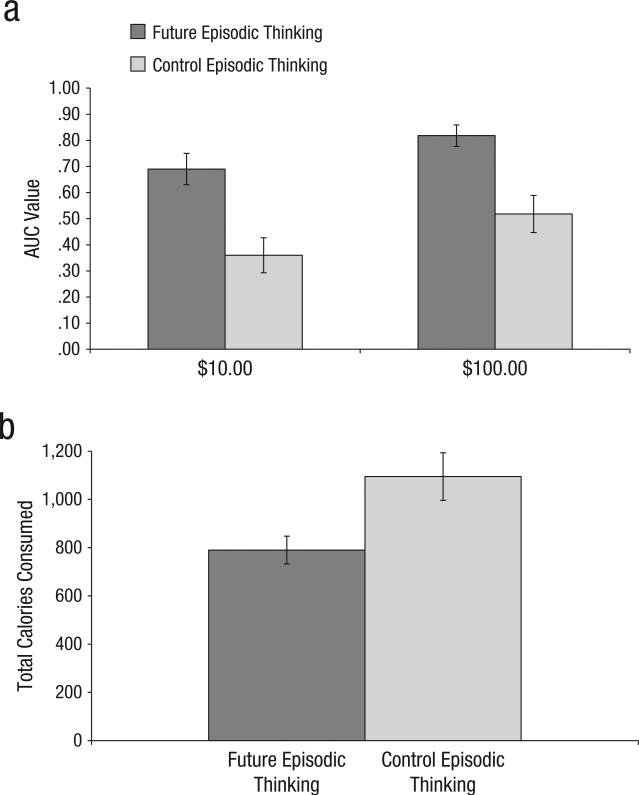

Ratings of the degree of imagery in episodic thoughts during the delay-discounting task were higher for episodic-future-thinking participants (M = 4.8, SD = 0.7) than for control-episodic-thinking participants (M = 4.0, SD = 0.6), F(1, 24) = 11.27, p < .005, Cohen's d = 1.23. Controlling for these differences, episodic-future-thinking participants discounted less than did control-episodic-thinking participants, F(1, 23) = 6.57, p = .017; $10 reward: Cohen's d =1.44; $100 reward: Cohen's d = 1.51 (Fig. 1a). No group differences were observed in the ratings of episodic thought during the ad libitum eating. Episodic-future-thinking participants consumed fewer calories (M = 789.9, SD = 215.8) than did control-episodic-thinking participants (M = 1,094.7, SD = 341.8), F(1, 24) = 7.62, p = .011, Cohen's d = 1.09 (Fig. 1b).

Fig. 1.

Mean area-under-the-curve (AUC) values for discounting of delayed rewards as a function of size of reward and condition (a), and mean caloric intake (b) as a function of condition. Error bars represent standard errors of the mean.

Discussion

Our results constitute the first evidence that episodic future thinking led overweight and obese women tempted with the immediate gratification of unhealthy foods to reduce their delay discounting and energy intake, an important self-regulatory skill in maintaining a healthy weight. Potential explanations for episodic future thinking's effect are that prospective imagery improves either the consideration of (Benoit et al., 2011) or the search for (Kurth-Nelson, Bickel, & Redish, 2012) the actual value of delayed outcomes during decision making. We based our control condition (one of the first episodic-thinking control conditions to be used in research on episodic future thinking's impact on delay discounting) on episodic thinking about nonpersonal autobiographical details to address this methodological limitation. However, events were more vividly imagined by participants engaging in episodic future thinking than by participants engaging in nonpersonal episodic thinking during delay discounting. This suggests that the vividness of nonpersonal events is not equivalent to that of episodic future events and that thinking about personal past or recent events may be more vivid and, thus, a better comparison to episodic future thinking.

Imagine a future in which people use episodic future thinking to control impulsive behavior. Given that high delay-discounting rates occur in many addictive and behavioral disorders (Bickel, Jarmolowicz, Mueller, Koffarnus, & Gatchalian, 2012), our results suggest multiple directions for future research. Research determining the temporal duration and durability of episodic future thinking's effect is needed to further the understanding of its utility as an intervention tool. Investigating episodic future thinking's impact in real-world impulsive situations will facilitate the translation of episodic future thinking into an effective intervention for impulsive behaviors.

Acknowledgments

Thanks go to Shirin Aghazadeh, to David Lowry for help with data entry, and to Katelyn Carr and Henry Lin for feedback on the study design.

Funding

This research was funded in part by Grant 1U01 DK088380 from the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases to L. H. Epstein.

Footnotes

Author Contributions

T. O. Daniel developed the study concept in collaboration with L. H. Epstein. T. O. Daniel and L. H. Epstein contributed to the study design. Protocol implementation and data collection were performed by T. O. Daniel and C. M. Stanton. T. O. Daniel analyzed and interpreted the data under the supervision of L. H. Epstein. T. O. Daniel drafted the manuscript, and L. H. Epstein provided critical revisions. C. M. Stanton prepared the figure and the descriptive data analysis of participant characteristics. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript for submission.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The authors declared that they had no conflicts of interest with respect to their authorship or the publication of this article.

References

- Allison DB, Kalinsky LB, Gorman BS. A comparison of the psychometric properties of three measures of dietary restraint. Psychological Assessment. 1992;4:391–398. [Google Scholar]

- Appelhans BM, Waring ME, Schneider KL, Pagoto SL, DeBiasse MA, Whited MC, Lynch EB. Delay discounting and intake of ready-to-eat and away-from-home foods in overweight and obese women. Appetite. 2012;59:576–584. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2012.07.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atance CM, O'Neill DK. Episodic future thinking. Trends in Cognitive Sciences. 2001;5:533–539. doi: 10.1016/s1364-6613(00)01804-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benoit RG, Gilbert SJ, Burgess PW. A neural mechanism mediating the impact of episodic prospection on farsighted decisions. Journal of Neuroscience. 2011;31:6771–6779. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.6559-10.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Best JR, Theim KR, Gredysa DM, Stein RI, Welch RR, Saelens BE, Wilfley DE. Behavioral economic predictors of overweight children's weight loss. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2012;80:1086–1096. doi: 10.1037/a0029827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bickel WK, Jarmolowicz DP, Mueller ET, Koffarnus MN, Gatchalian KM. Excessive discounting of delayed reinforcers as a trans-disease process contributing to addiction and other disease-related vulnerabilities: Emerging evidence. Pharmacology & Therapeutics. 2012;134:287–297. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2012.02.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bickel WK, Marsch LA. Toward a behavioral economic understanding of drug dependence: Delay discounting processes. Addiction. 2001;96:73–86. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2001.961736.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D'Argembeau A, Van der Linden M. Phenomenal characteristics associated with projecting oneself back into the past and forward into the future: Influence of valence and temporal distance. Consciousness and Cognition. 2004;13:844–858. doi: 10.1016/j.concog.2004.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis C, Patte K, Curtis C, Reid C. Immediate pleasures and future consequences. A neuropsychological study of binge eating and obesity. Appetite. 2010;54:208–213. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2009.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dixon MR, Marley J, Jacobs EA. Delay discounting by pathological gamblers. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2003;36:449–458. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2003.36-449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fedoroff I, Polivy J, Herman CP. The specificity of restrained versus unrestrained eaters’ responses to food cues: General desire to eat, or craving for the cued food? Appetite. 2003;41:7–13. doi: 10.1016/s0195-6663(03)00026-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Francis LA, Susman EJ. Self-regulation and rapid weight gain in children from age 3 to 12 years. Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine. 2009;163:297–302. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2008.579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurth-Nelson Z, Bickel W, Redish AD. A theoretical account of cognitive effects in delay discounting. European Journal of Neuroscience. 2012;35:1052–1064. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2012.08058.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacLeod AK, Pankhania B, Lee M, Mitchell D. Parasuicide, depression and the anticipation of positive and negative future experiences. Psychological Medicine. 1997;27:973–977. doi: 10.1017/s003329179600459x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myerson J, Green L, Warusawitharana M. Area under the curve as a measure of discounting. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior. 2001;76:235–243. doi: 10.1901/jeab.2001.76-235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters J, Büchel C. Episodic future thinking reduces reward delay discounting through an enhancement of pre-frontal-mediotemporal interactions. Neuron. 2010;66:138–148. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2010.03.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rollins BY, Dearing KK, Epstein LH. Delay discounting moderates the effect of food reinforcement on energy intake among non-obese women. Appetite. 2010;55:420–425. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2010.07.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schacter DL, Addis DR, Buckner RL. Remembering the past to imagine the future: The prospective brain. Nature Reviews Neuroscience. 2007;8:657–661. doi: 10.1038/nrn2213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suddendorf T, Busby J. Making decisions with the future in mind: Developmental and comparative identification of mental time travel. Learning and Motivation. 2005;36:110–125. [Google Scholar]

- Weller RE, Cook EW, III, Avsar KB, Cox JE. Obese women show greater delay discounting than healthy-weight women. Appetite. 2008;51:563–569. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2008.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]