Abstract

IMPORTANCE

Conjunctivitis is a common problem.

OBJECTIVE

To examine the diagnosis, management, and treatment of conjunctivitis, including various antibiotics and alternatives to antibiotic use in infectious conjunctivitis and use of antihistamines and mast cell stabilizers in allergic conjunctivitis.

EVIDENCE REVIEW

A search of the literature published through March 2013, using PubMed, the ISI Web of Knowledge database, and the Cochrane Library was performed. Eligible articles were selected after review of titles, abstracts, and references.

FINDINGS

Viral conjunctivitis is the most common overall cause of infectious conjunctivitis and usually does not require treatment; the signs and symptoms at presentation are variable. Bacterial conjunctivitis is the second most common cause of infectious conjunctivitis, with most uncomplicated cases resolving in 1 to 2 weeks. Mattering and adherence of the eyelids on waking, lack of itching, and absence of a history of conjunctivitis are the strongest factors associated with bacterial conjunctivitis. Topical antibiotics decrease the duration of bacterial conjunctivitis and allow earlier return to school or work. Conjunctivitis secondary to sexually transmitted diseases such as chlamydia and gonorrhea requires systemic treatment in addition to topical antibiotic therapy. Allergic conjunctivitis is encountered in up to 40% of the population, but only a small proportion of these individuals seek medical help; itching is the most consistent sign in allergic conjunctivitis, and treatment consists of topical antihistamines and mast cell inhibitors.

CONCLUSIONS AND RELEVANCE

The majority of cases in bacterial conjunctivitis are self-limiting and no treatment is necessary in uncomplicated cases. However, conjunctivitis caused by gonorrhea or chlamydia and conjunctivitis in contact lens wearers should be treated with antibiotics. Treatment for viral conjunctivitis is supportive. Treatment with antihistamines and mast cell stabilizers alleviates the symptoms of allergic conjunctivitis.

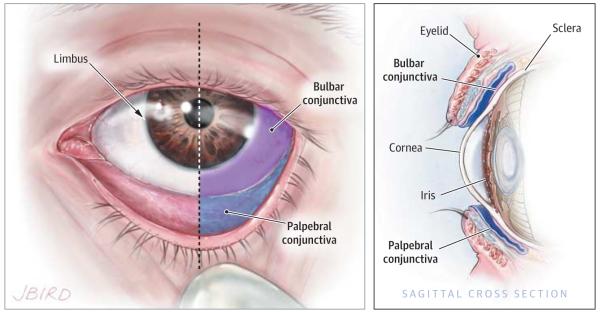

Conjunctiva is a thin, translucent membrane lining the anterior part of the sclera and inside of the eyelids. It has 2 parts, bulbar and palpebral. The bulbar portion begins at the edge of the cornea and covers the visible part of the sclera; the palpebral part lines the inside of the eyelids (Figure 1). Inflammation or infection of the conjunctiva is known as conjunctivitis and is characterized by dilatation of the conjunctival vessels, resulting in hyperemia and edema of the conjunctiva, typically with associated discharge.1

Figure 1. Normal Conjunctival Anatomy.

The conjunctiva is a thin membrane covering the sclera (bulbar conjunctiva, labeled with purple) and the inside of the eyelids (palpebral conjunctiva, labeled with blue).

Conjunctivitis affects many people and imposes economic and social burdens. It is estimated that acute conjunctivitis affects 6 million people annually in the United States.2 The cost of treating bacterial conjunctivitis alone was estimated to be $377 million to $857 million per year.3 Many US state health departments, irrespective of the underlying cause of conjunctivitis, require students to be treated with topical antibiotic eyedrops before returning to school.4

A majority of conjunctivitis patients are initially treated by primary care physicians rather than eye care professionals. Approximately 1% of all primary care office visits in the United States are related to conjunctivitis.5 Approximately 70% of all patients with acute conjunctivitis present to primary care and urgent care.6

The prevalence of conjunctivitis varies according to the underlying cause, which may be influenced by the patient’s age, as well as the season of the year. Viral conjunctivitis is the most common cause of infectious conjunctivitis both overall and in the adult population7-13 and is more prevalent in summer.14 Bacterial conjunctivitis is the second most common cause7-9,12,13 and is responsible for the majority (50%-75%) of cases in children14; it is observed more frequently from December through April.14 Allergic conjunctivitis is the most frequent cause, affecting 15% to 40% of the population,15 and is observed more frequently in spring and summer.14

Conjunctivitis can be divided into infectious and noninfectious causes. Viruses and bacteria are the most common infectious causes. Noninfectious conjunctivitis includes allergic, toxic, and cicatricial conjunctivitis, as well as inflammation secondary to immune-mediated diseases and neoplastic processes.16 The disease can also be classified into acute, hyperacute, and chronic according to the mode of onset and the severity of the clinical response.17 Furthermore, it can be either primary or secondary to systemic diseases such as gonorrhea, chlamydia, graft-vs-host disease, and Reiter syndrome, in which case systemic treatment is warranted.16

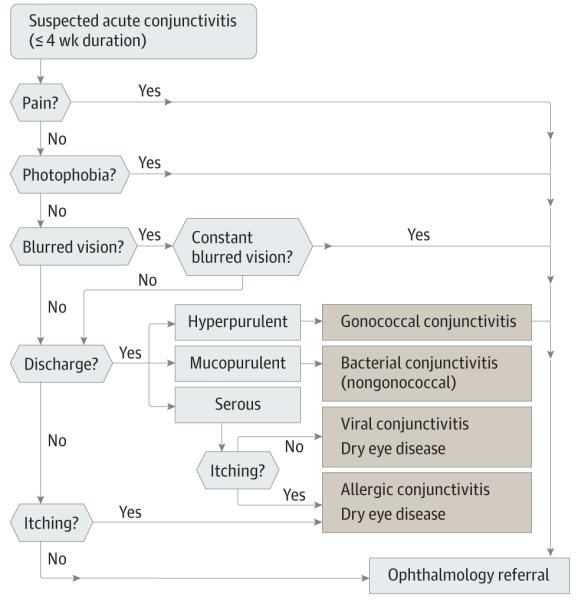

It is important to differentiate conjunctivitis from other sight-threatening eye diseases that have similar clinical presentation and to make appropriate decisions about further testing, treatment, or referral. An algorithmic approach (Figure 2) using a focused ocular history along with a penlight eye examination may be helpful in diagnosis and treatment. Because conjunctivitis and many other ocular diseases can present as “red eye,” the differential diagnosis of red eye and knowledge about the typical features of each disease in this category are important (Table 1).

Figure 2. Suggested Algorithm for Clinical Approach to Suspected Acute Conjunctivitis.

Table 1.

Selected Nonconjunctivitis Causes of Red Eyea

| Differential Diagnosis | Symptoms | Penlight Examination Findings |

|---|---|---|

| Dry eye disease | Burning and foreign-body sensation. Symptoms are usu- ally transient, worse with prolonged reading or watching television because of decreased blinking. Symptoms are worse in dry, cold, and windy environments because of increased evaporation. |

Bilateral redness |

| Blepharitis | Similar to dry eyes | Redness greater at the margins of eyelids |

| Uveitis | Photophobia, pain, blurred vision. Symptoms are usually bilateral. |

Decreased vision, poorly reacting pupils, constant eye pain radiating to temple and brow. Redness, severe photophobia, presence of inflammatory cells in the anterior chamber. |

| Angle closure glaucoma | Headaches, nausea, vomiting, ocular pain, decreased vision, light sensitivity, and seeing haloes around lights. Symptoms are usually unilateral. |

Firm eye on palpation, ocular redness with limbal injec- tion. Appearance of a hazy/steamy cornea, moderately dilated pupils that are unreactive to light. |

| Carotid cavernous fistula | Chronic red eye; may have a history of head trauma | Dilated tortuous vessels (corkscrew vessels), bruits on auscultation with a stethoscope |

| Endophthalmitis | Severe pain, photophobia, may have a history of eye sur- gery or ocular trauma |

Redness, pus in the anterior chamber, and photophobia |

| Cellulitis | Pain, double vision, and fullness | Redness and swelling of lids, may have restriction of the eye movements, may have a history of preceding sinus- itis (usually ethmoiditis) |

| Anterior segment tumors | Variable | Abnormal growth inside or on the surface of the eye |

| Scleritis | Decreased vision, moderate to severe pain | Redness, bluish sclera hue |

| Subconjunctival hemorrhage | May have foreign-body sensation and tearing or be asymptomatic |

Blood under the conjunctival membrane |

Methods

The literature published through March 2013 was reviewed by searching PubMed, the ISI Web of Knowledge database, and the Cochrane Library. The following keywords were used: bacterial conjunctivitis, viral conjunctivitis, allergic conjunctivitis, treatment of bacterial conjunctivitis, and treatment of viral conjunctivitis. No language restriction was applied. Articles published between March 2003 and March 2013 were initially screened. After review of titles, abstracts, text, and references for the articles, more were identified and screened. Articles and meta-analyses that provided evidence-based information about the cause, management, and treatment of various types of conjunctivitis were selected. A total of 86 articles were included in this review. The first study8 was published in 1982 and the last19 in 2012. A level of evidence was assigned to the recommendations presented in Table 2 and Table 3 with the American Heart Association grading system: “The strongest weight of evidence (A) is assigned if there are multiple randomized trials with large numbers of patients. An intermediate weight (B) is assigned if there are a limited number of randomized trials with small numbers of patients, careful analyses of non-randomized studies, or observational registries. The lowest rank of evidence (C) is assigned when expert consensus is the primary basis for the recommendation.60

Table 2.

Ophthalmic Therapies for Conjunctivitis

| Category | Epidemiology | Type of Discharge |

Cause | Treatment | Level of Evidence for Treatment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acute bacterial conjunctivitis |

135 case per 10 000 population in US3 18.3%-57% of all acute conjunctivitis7-9,12,13 |

Mucopurulent |

S aureus, S epidermidis, H influenzae, S pneumoniae, S viridans, Moraxella spp |

Aminoglycosides | |

| Gentamicin Ointment: 4 ×/d for 1 wk Solution: 1-2 drops 4 ×/d for 1 wk |

B20-22 | ||||

| Tobramycin ointment: 3 ×/d for 1 wk | A23-30 | ||||

| Fluoroquinolones | |||||

| Besifloxacin: 1 drop 3 ×/d for 1 wk | A31-34 | ||||

| Ciprofloxacin ointment: 3 ×/d for 1 wk Solution: 1-2 drops 4 ×/d for 1 wk |

A24,28,29 | ||||

| Gatifloxacin: 3 ×/d for 1 week | B35 | ||||

| Levofloxacin: 1-2 drops 4 ×/d for 1 wk | B36-38 | ||||

| Moxifloxacin: 3 ×/d for 1 wk | A34,39,40 | ||||

| Ofloxacin: 1-2 drops 4 ×/d for 1 wk | A37,38,41,42 | ||||

| Macrolides | |||||

| Azithromycin: 2 ×/d for 2 d; then 1 drop daily for 5 d |

A27,30,43,44 | ||||

| Erythromycin: 4 ×/d for 1 wk | B45 | ||||

| Sulfonamides | |||||

| Sulfacetamide ointment: 4 ×/d and at bedtime for 1 wk Solution: 1-2 drops every 2-3 h for 1 wk |

B22 | ||||

| Combination drops | |||||

| Trimethoprim/polymyxin B: 1 or 2 drops 4 ×/d for 1 wk |

A22,40,46 | ||||

| Hyperacute bacterial conjunctivitis in adults |

NA | Purulent | Neisseria gonorrhoeae | Ceftriaxone: 1 g IMonce | C16,47 |

| Lavage of the infected eye | C16 | ||||

| Dual therapy to cover chlamydia is indicated | C48 | ||||

| Viral conjunctivitis |

9%-80.3% of all acute conjunctivitis8-13 |

Serous | Up to 65% are due to adenovirus strains49 |

Cold compress Artificial tears Antihistamines |

C16,50 |

| Herpes zoster virus |

NA | Variable | Herpes zoster virus | Oral acyclovir 800 mg: 5 ×/d for 7-10 d | C16 |

| Oral famciclovir 500 mg: 3 ×/d for 7-10 d | C16 | ||||

| Oral valacyclovir 1000 mg: 3 ×/d for 7-10 d | C16 | ||||

| Herpes simplex virus |

1.3-4.8 of all acute conjunctivitis9-12 |

Variable | Herpes simplex virus | Topical acyclovir: 1 drop 9 ×/d | C16 |

| Oral acyclovir 400 mg: 5 ×/d for 7-10 d | C16 | ||||

| Oral valacyclovir 500 mg: 3 ×/d for 7-10 d | C16 | ||||

| Adult inclusion conjunctivitis |

1.8%-5.6% of all acute conjunctivitis5,8-11 |

Variable | Chlamydia trachomatis | Azithromycin 1 g: orally once | B16,51 |

| Doxycycline 100 mg: orally 2 ×/d for 7 d | B16,51 | ||||

| Allergic conjunctivitis |

90% of all allergic conjunctivitis15; up to 40% of population may be affected15 |

Serous or mucoid |

Pollens | Topical antihistamines | |

| Azelastine 0.05%: 1 drop 2 ×/d | A52 | ||||

| Emedastine 0.05%: 1 drop 4 ×/d | A52 | ||||

| Topical mast cell inhibitors | |||||

| Cromolyn sodium 4%: 1-2 drops every 4-6 h | A52 | ||||

| Lodoxamide 0.1%: 1-2 drops 4 ×/d | A52 | ||||

| Nedocromil 2%: 1-2 drops 2 ×/d | A52 | ||||

| NSAIDs | |||||

| Ketorolac: 1 drop 4 ×/d | B53,54 | ||||

| Vasoconstrictor/antihistamine | |||||

| Naphazoline/pheniramine: 1-2 drops up to 4 ×/d |

B55 | ||||

| Combination drops | |||||

| Ketotifen 0.025%: 1 drop 2-3 ×/d | A56,57 | ||||

| Olopatadine 0.1%: 1 drop 2 ×/d | A58,59 |

Abbreviations: IM, intramuscularly; NA, not available; NSAIDs, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs.

Table 3.

Evidence-Based Recommendations in Conjunctivitis

| Recommendation | Level of Evidence |

|---|---|

| Topical antibiotics are effective in reducing the duration of conjunctivitis. |

A19 |

| Observation is reasonable in most cases of bacterial conjunctivitis (suspected or confirmed) because they often resolve spontane- ously and no treatment is necessary. |

A41 |

| It is reasonable to use any broad-spectrum antibiotics for treating bacterial conjunctivitis. |

A19,41 |

| In allergic conjunctivitis, use of topical antihistamines and mast cell stabilizers is recommended. |

A52 |

| Good hand hygiene can be used to decrease the spread of acute viral conjunctivitis. |

C16 |

| Bacterial cultures can be useful in cases of severely purulent conjunctivitis or cases that are recalcitrant to therapy. |

C16 |

| It may be helpful to treat viral conjunctivitis with artificial tears, topical antihistamines, or cold compresses. |

C16 |

| Topical steroids are not recommended for bacterial conjunctivitis. | C65 |

How to Differentiate Conjunctivitis of Different Origins

History and Physical Examination

Focused ocular examination and history are crucial for making appropriate decisions about the treatment and management of any eye condition, including conjunctivitis. Eye discharge type and ocular symptoms can be used to determine the cause of the conjunctivitis.61,62 For example, a purulent or mucopurulent discharge is often due to bacterial conjunctivitis (Figure 3A and Figure 3B), whereas a watery discharge is more characteristic of viral conjunctivitis (Figure 3C)61,62; itching is also associated with allergic conjunctivitis.49,63

Figure 3. Characteristic Appearance of Bacterial and Viral Conjunctivitis.

A, Bacterial conjunctivitis characterized by mucopurulent discharge and conjunctival hyperemia. B, Severe purulent discharge seen in hyperacute bacterial conjunctivitis secondary to gonorrhea. C, Intensely hyperemic response with thin, watery discharge characteristic of viral conjunctivitis. Images reproduced with permission: © 2013 American Academy of Ophthalmology.

However, the clinical presentation is often nonspecific. Relying on the type of discharge and patient symptoms does not always lead to an accurate diagnosis. Furthermore, scientific evidence correlating conjunctivitis signs and symptoms with the underlying cause is often lacking.61 For example, in a study of patients with culture-positive bacterial conjunctivitis, 58% had itching, 65% had burning, and 35% had serous or no discharge at all,64 illustrating the nonspecificity of the signs and symptoms of this disease. In 2003, a large meta-analysis failed to find any clinical studies correlating the signs and symptoms of conjunctivitis with the underlying cause61; later, the same authors conducted a prospective study61 and found that a combination of 3 signs–bilateral mattering of the eyelids, lack of itching, and no history of conjunctivitis–strongly predicted bacterial conjunctivitis. Having both eyes matter and the lids adhere in the morning was a stronger predictor for positive bacterial culture result, and either itching or a previous episode of conjunctivitis made a positive bacterial culture result less likely.64 In addition, type of discharge (purulent, mucus, or watery) or other symptoms were not specific to any particular class of conjunctivitis.64,65

Although in the primary care setting an ocular examination is often limited because of lack of a slitlamp, useful information may be obtained with a simple penlight. The eye examination should focus on the assessment of the visual acuity, type of discharge, cor-neal opacity, shape and size of the pupil, eyelid swelling, and presence of proptosis.

Laboratory Investigations

Obtaining conjunctival cultures is generally reserved for cases of suspected infectious neonatal conjunctivitis, recurrent conjunctivitis, conjunctivitis recalcitrant to therapy, conjunctivitis presenting with severe purulent discharge, and cases suspicious for gonococcal or chlamydial infection.16

In-office rapid antigen testing is available for adenoviruses and has 89% sensitivity and up to 94% specificity.66 This test can identify the viral causes of conjunctivitis and prevent unnecessary antibiotic use. Thirty-six percent of conjunctivitis cases are due to adenoviruses, and one study estimated that in-office rapid antigen testing could prevent 1.1 million cases of inappropriate treatment with antibiotics, potentially saving $429 million annually.2

Infectious Conjunctivitis

Viral Conjunctivitis

Epidemiology, Cause, and Presentation

Viruses cause up to 80% of all cases of acute conjunctivitis.8-13,67 The rate of clinical accuracy in diagnosing viral conjunctivitis is less than 50% compared with laboratory confirmation.49 Many cases are misdiagnosed as bacterial conjunctivitis.49

Between 65% and 90% of cases of viral conjunctivitis are caused by adenoviruses,49 and they produce 2 of the common clinical entities associated with viral conjunctivitis, pharyngoconjunctival fever and epidemic keratoconjunctivitis.62 Pharyngoconjunctival fever is characterized by abrupt onset of high fever, pharyngitis, and bilateral conjunctivitis, and by periauricular lymph node enlargement, whereas epidemic keratoconjunctivitis is more severe and presents with watery discharge, hyperemia, chemosis, and ipsilateral lymphadenopathy.68 Lymphadenopathy is observed in up to 50%of viral conjunctivitis cases and is more prevalent in viral conjunctivitis compared with bacterial conjunctivitis.49

Prevention and Treatment

Viral conjunctivitis secondary to adenoviruses is highly contagious, and the risk of transmission has been estimated to be 10% to 50%.6,14 The virus spreads through direct contact via contaminated fingers, medical instruments, swimming pool water, or personal items; in one study, 46% of infected people had positive cultures grown from swabs of their hands.69 Because of the high rates of transmission, hand washing, strict instrument disinfection, and isolation of the infected patients from the rest of the clinic has been advocated.70 Incubation and communicability are estimated to be 5 to 12 days and 10 to 14 days, respectively.14

Although no effective treatment exists, artificial tears, topical antihistamines, or cold compresses may be useful in alleviating some of the symptoms (Table 2).16,50 Available antiviral medications are not useful16,50 and topical antibiotics are not indicated.18 Topical antibiotics do not protect against secondary infections, and their use may complicate the clinical presentation by causing allergy and toxicity, leading to delay in diagnosis of other possible ocular diseases.49 Use of antibiotic eyedrops can increase the risk of spreading the infection to the other eye from contaminated droppers.49 Increased resistance is also of concern with frequent use of antibiotics.6 Patients should be referred to an ophthalmologist if symptoms do not resolve after 7 to 10 days because of the risk of complications.1

Herpes Conjunctivitis

Herpes simplex virus comprises 1.3% to 4.8% of all cases of acute conjunctivitis.9-12 Conjunctivitis caused by the virus is usually unilateral. The discharge is thin and watery, and accompanying vesicular eyelid lesions may be present. Topical and oral antivirals are recommended (Table 2) to shorten the course of the disease.16 Topical corticosteroids should be avoided because they potentiate the virus and may cause harm.16,71

Herpes zoster virus, responsible for shingles, can involve ocular tissue, especially if the first and second branches of the trigeminal nerve are involved. Eyelids (45.8%) are the most common site of ocular involvement, followed by the conjunctiva (41.1%).72 Corneal complication and uveitis may be present in 38.2% and 19.1% of cases, respectively.72 Patients with suspected eyelid or eye involvement or those presenting with Hutchinson sign (vesicles at the tip of the nose, which has high correlations with corneal involvement) should be referred for a thorough ophthalmic evaluation. Treatment usually consists of a combination of oral antivirals and topical steroids.73

Bacterial Conjunctivitis

Epidemiology, Cause, and Presentation

The incidence of bacterial conjunctivitis was estimated to be 135 in 10 000 in one study.3 Bacterial conjunctivitis can be contracted directly from infected individuals or can result from abnormal proliferation of the native conjunctival flora.17 Contaminated fingers,14 oculogenital spread,16 and contaminated fomites48 are common routes of transmission. In addition, certain conditions such as compromised tear production, disruption of the natural epithelial barrier, abnormality of adnexal structures, trauma, and immunosup-pressed status predispose to bacterial conjunctivitis.16 The most common pathogens for bacterial conjunctivitis in adults are staphylococcal species, followed by Streptococcus pneumoniae and Haemophilus influenzae.41 In children, the disease is often caused by H influenzae, S pneumoniae, and Moraxella catarrhalis.41 The course of the disease usually lasts 7 to 10 days (Figure 3).62

Hyperacute bacterial conjunctivitis presents with a severe copious purulent discharge and decreased vision (Figure 3). There is often accompanying eyelid swelling, eye pain on palpation, and preauricular adenopathy. It is often caused by Neisseria gonorrhoeae and carries a high risk for corneal involvement and subsequent corneal perforation.17 Treatment for hyperacute conjunctivitis secondary to N gonorrhoeae consists of intramuscular ceftriaxone, and concurrent chlamydial infection should be managed accordingly.47

Chronic bacterial conjunctivitis is used to describe any conjunctivitis lasting more than 4 weeks, with Staphylococcus aureus, Moraxellalacunata, and enteric bacteria being the most common causes in this setting62; ophthalmologic consultation should be sought for management.

Signs and symptoms include red eye, purulent or mucopurulent discharge, and chemosis (Figure 3).17 The period of incubation and communicability is estimated to be 1 to 7 days and 2 to 7 days, respectively.14 Bilateral mattering of the eyelids and adherence of the eyelids, lack of itching, and no history of conjunctivitis are strong positive predictors of bacterial conjunctivitis.64 Severe purulent discharge should always be cultured and gonococcal conjunctivitis should be considered (Figure 3B).16 Conjunctivitis not responding to standard antibiotic therapy in sexually active patients warrants a chlamydial evaluation.18 The possibility of bacterial keratitis is high in contact lens wearers, who should be treated with topical antibiotics14 and referred to an ophthalmologist. A patient wearing contact lenses should be asked to immediately remove them.65

Use of Antibiotics in Bacterial Conjunctivitis

At least 60% of cases of suspected or culture-proven acute bacterial conjunctivitis are self-limiting within 1 to 2 weeks of presentation.14 Although topical antibiotics reduce the duration of the disease, no differences have been observed in outcomes between treatment and placebo groups. In a large meta-analysis,19 consisting of a review of 3673 patients in 11 randomized clinical trials, there was an approximately 10% increase in the rate of clinical improvement compared with that for placebo for patients who received either 2 to 5 days or 6 to 10 days of antibiotic treatment compared with the placebo. No serious sight-threatening out comes were reported in any of the placebo groups.74 Some highly virulent bacteria, such as S pneumoniae, N gonorrhoeae, and H influenzae, can penetrate an intact host defense more easily and cause more serious damage.17

Topical antibiotics seem to be more effective in patients who have positive bacterial culture results. In a large systemic review, they were found to be effective at increasing both the clinical and micro-biological cure rate in the group of patients with culture-proven bacterial conjunctivitis, whereas only an improved microbial cure rate was observed in the group of patients with clinically suspected bacterial conjunctivitis.67 Other studies found no significant difference in clinical cure rate when the frequencies of the administered antibiotics were slightly changed.41,75

Choices of Antibiotics

All broad-spectrum antibiotic eyedrops seem in general to be effective in treating bacterial conjunctivitis. There are no significant differences in achieving clinical cure between any of the broad-spectrum topical antibiotics. Factors that influence antibiotic choice are local availability, patient allergies, resistance pat terns, and cost. Initial therapy for acute nonsevere bacterial conjunctivitis is listed in Table 2.

Alternatives to Immediate Antibiotic Therapy

To our knowledge, no studies have been conducted to evaluate the efficacy of ocular decongestant, topical saline, or warm compresses for treating bacterial conjunctivitis.41 Topical steroids should be avoided because of the risk of potentially prolonging the course of the disease and potentiating the infection.16

Summary of Recommendations for Managing Bacterial Conjunctivitis

In conclusion, benefits of antibiotic treatment include quicker recovery, decrease in transmissibility,49 and early return to school.4 Simultaneously, adverse effects are absent if antibiotics are not used in uncomplicated cases of bacterial conjunctivitis. Therefore, no treatment, a wait-and-see policy, and immediate treatment all appear to be reasonable approaches in cases of uncomplicated conjunctivitis. Antibiotic therapy should be considered in cases of purulent or mucopurulent conjunctivitis and for patients who have distinct discomfort, who wear contact lenses,14,18 who are immunocompromised, and who have suspected chlamydial and gonococcal conjunctivitis.

Special Topics in Bacterial Conjunctivitis

Methicillin-Resistant S aureus Conjunctivitis

It is estimated that 3% to 64% of ocular staphylococcal infections are due to methicillin-resistant S aureus conjunctivitis; this condition is becoming more common and the organisms are resistant to many antibiotics.76 Patients with suspected cases need to be referred to an ophthalmologist and treated with fortified vancomycin.77

Chlamydial Conjunctivitis

It is estimated that 1.8% to 5.6% of all acute conjunctivitis is caused by chlamydia,5,8-11 and the majority of cases are unilateral and have concurrent genital infection.1 Conjunctival hyperemia, mucopurulent discharge, and lymphoid follicle formation51 are hallmarks of this condition. Discharge is often purulent or mucopurulent.18 How ever, patients more often present with mild symptoms for weeks to months. Up to 54% of men and 74% of women have concurrent genital chlamydial infection.78 The disease is often acquired via oculogenital spread or other intimate contact with infected individuals; in newborns the eyes can be infected after vaginal delivery by infected mothers.16 Treatment with systemic antibiotics such as oral azithromycin and doxycycline is efficacious (Table 2); patients and their sexual partners must be treated and a coinfection with gonorrhea must be investigated. No data support the use of topical antibiotic therapy in addition to systemic treatment.16 Infants with chlamydial conjunctivitis require systemic therapy because more than 50% can have concurrent lung, nasopharynx, and genital tract infection.16

Gonococcal Conjunctivitis

Conjunctivitis caused by N gonorrhoeae is a frequent source of hyperacute conjunctivas in neonates and sexually active adults and young adolescents.17 Treatment consists of both topical and oral antibiotics. Neisseria gonorrhoeae is associated with a high risk of cor-neal perforation.65

Conjunctivitis Secondary to Trachoma

Trachoma is caused by Chlamydia trachomatis subtypes A through C and is the leading cause of blindness, affecting 40 million people worldwide in areas with poor hygiene.79,80 Mucopurulent discharge and ocular discomfort may be the presenting signs and symptoms in this condition. Late complications such as scarring of the eyelid, conjunctiva, and cornea may lead to loss of vision. Treatment with a single dose of oral azithromycin (20 mg/kg) is effective. Patients may also be treated with topical antibiotic ointments for 6 weeks (ie, tetracycline or erythromycin). Systemic antibiotics other than azithromycin, such as tetracycline or erythromycin for 3 weeks, may be used alternatively.79,80

Noninfectious Conjunctivitis

Allergic Conjunctivitis

Prevalence and Cause

Allergic conjunctivitis is the inflammatory response of the conjunctiva to allergens such as pollen, animal dander, and other environmental antigens15 and affects up to 40% of the population in the United States15; only about 10% of individuals with allergic conjunctivitis seek medical attention, and the entity is often underdiagnosed.81 Redness and itching are the most consistent symptoms.15 Seasonal allergic conjunctivitis comprises 90% of all allergic conjunctivitis in the United States.82

Treatment

Treatment consists of avoidance of the offending antigen52 and use of saline solution or artificial tears to physically dilute and remove the allergens.15 Topical decongestants, antihistamines,52 mast cell stabilizers,52 nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs,53,54 and corticosteroids82 may be indicated. In a large systemic review, both antihistamines and mast cell stabilizers were superior to placebo in reducing the symptoms of allergic conjunctivitis; researchers also found that antihistamines were superior to mast cell stabilizers in providing short-term benefits.52 Long-term use of the antihistamine antazoline and the vasoconstrictor naphazoline should be avoided because they both can cause rebound hyperemia.52 Steroids should be used with caution and judiciously. Topical steroids are associated with formation of cataract and can cause an increase in eye pressure, leading to glaucoma.

Drug-, Chemical-, and Toxin-Induced Conjunctivitis

A variety of topical medications such as antibiotic eyedrops, topical antiviral medications, and lubricating eyedrops can induce allergic conjunctival responses largely because of the presence of benzalkonium chloride in eye drop preparations.83 Cessation of receiving the offending agent leads to resolution of symptoms.16

Systemic Diseases Associated With Conjunctivitis

A variety of systemic diseases, including mucous membrane pemphigoid, Sjögren syndrome, Kawasaki disease,84 Stevens-Johnson syndrome,85 and carotid cavernous fistula,86 can present with signs and symptoms of conjunctivitis, such as conjunctival redness and discharge. Therefore, the above causes should be considered in patients presenting with conjunctivitis. For example, patients with low-grade carotid cavernous fistula can present with chronic conjunctivitis recalcitrant to medical therapy, which, if left untreated, can lead to death.

Ominous Signs

As recommended by the American Academy of Ophthalmology,16 patients with conjunctivitis who are evaluated by nonophthalmologist health care practitioners should be referred promptly to an ophthalmologist if any of the following develops: visual loss, moderate or severe pain, severe purulent discharge, corneal involvement, conjunctival scarring, lack of response to therapy, recurrent episodes of conjunctivitis, or history of herpes simplex virus eye disease. In addition, the following patients should be considered for referral: contact lens wearers, patients requiring steroids, and those with photophobia. Patients should be referred to an ophthalmologist if there is no improvement after 1 week.1

Importance of Not Using Antibiotic/Steroid Combination Drops

Steroid drops or combination drops containing steroids should not be used routinely. Steroids can increase the latency of the adeno-viruses, the refore prolonging the course of viral conjunctivitis. In addition, if an undiagnosed corneal ulcer secondary to herpes, bacteria, or fungus is present, steroids can worsen the condition, leading to corneal melt and blindness.

Conclusions

Approximately 1% of all patient visits to a primary care clinician are conjunctivitis related, and the estimated cost of the bacterial conjunctivitis alone is $377 million to $857 million annually.3,5 Relying on the signs and symptoms often leads to an inaccurate diagnosis. Nonherpetic viral conjunctivitis followed by bacterial conjunctivitis is the most common cause for infectious conjunctivitis.7-13 Allergic conjunctivitis affects nearly 40% of the population, but only a small proportion seeks medical care.15,81 The majority of viral conjunctivitis cases are due to adenovirus.49 There is no role for the use of topical antibiotics in viral conjunctivitis, and they should be avoided because of adverse treatment effects.6,49 Using a rapid antigen test to diagnose viral conjunctivitis and avoid inappropriate use of antibiotics is an appropriate strategy.66 Bacterial pathogens are isolated in only 50% of cases of suspected conjunctivitis,18 and at least 60% of bacterial conjunctivitis (clinically suspected or culture proven) is self-limited without treatment.14 Cultures are useful in cases that do not respond to therapy, cases of hyperacute conjunctivitis, and suspected chlamydial conjunctivitis.16 Treatment with topical antibiotics is usually recommended for contact lens wearers, those with mucopurulent discharge and eye pain, suspected cases of chlamydial and gonococcal conjunctivitis, and patients with preexisting ocular surface disease.14,18 The advantages of antibiotic use include early resolution of the disease,19 early return to work or school,4,14 and the possibility of decreased complications from conjunctivitis.14 The majority of cases of allergic conjunctivitis are due to seasonal allergies.82 Antihistamines, mast cell inhibitors, and topical steroids (in selected cases) are indicated for treating allergic conjunctivitis.82 Steroids must be used judiciously and only after a thorough ophthalmologic examination has been performed to rule out her petic infection or corneal involvement, both of which can worsen with steroids.16,71

Physicians must be vigilant to not overlook sight-threatening conditions with similarities to conjunctivitis, as summarized in Table 1.

Acknowledgments

Funding/Support: This work was supported by National Institutes of Health (NIH) grant P30-EY016665 (Core Grant for Vision Research) and an unrestricted department award from Research to Prevent Blindness. The project was also supported by the Clinical and Translational Science Award program through the NIH National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, grant UL1TR000427.

Role of the Sponsor: The sponsors played no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; and decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Disclosures: All authors have completed and submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest and none were reported.

REFERENCES

- 1.Leibowitz HM. The red eye. N Engl J Med. 2000;343(5):345–351. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200008033430507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Udeh BL, Schneider JE, Ohsfeldt RL. Cost effectiveness of a point-of-care test for adenoviral conjunctivitis. Am J Med Sci. 2008;336(3):254–264. doi: 10.1097/MAJ.0b013e3181637417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Smith AF, Waycaster C. Estimate of the direct and indirect annual cost of bacterial conjunctivitis in the United States. BMC Ophthalmol. 2009;9:13. doi: 10.1186/1471-2415-9-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ohnsman CM. Exclusion of students with conjunctivitis from school: policies of state departments of health. J Pediatr Ophthalmol Strabismus. 2007;44(2):101–105. doi: 10.3928/01913913-20070301-03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shields T, Sloane PD. A comparison of eye problems in primary care and ophthalmology practices. Fam Med. 1991;23(7):544–546. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kaufman HE. Adenovirus advances: new diagnostic and therapeutic options. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2011;22(4):290–293. doi: 10.1097/ICU.0b013e3283477cb5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hørven I. Acute conjunctivitis: a comparison of fusidic acid viscous eye drops and chloramphenicol. Acta Ophthalmol (Copenh) 1993;71(2):165–168. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-3768.1993.tb04983.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stenson S, Newman R, Fedukowicz H. Laboratory studies in acute conjunctivitis. Arch Ophthalmol. 1982;100(8):1275–1277. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1982.01030040253009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rönnerstam R, Persson K, Hansson H, Renmarker K. Prevalence of chlamydial eye infection in patients attending an eye clinic, a VD clinic, and in healthy persons. Br J Ophthalmol. 1985;69(5):385–388. doi: 10.1136/bjo.69.5.385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Harding SP, Mallinson H, Smith JL, Clearkin LG. Adult follicular conjunctivitis and neonatal ophthalmia in a Liverpool eye hospital, 1980-1984. Eye (Lond) 1987;1(pt 4):512–521. doi: 10.1038/eye.1987.77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Uchio E, Takeuchi S, Itoh N, et al. Clinical and epidemiological features of acute follicular conjunctivitis with special reference to that caused by herpes simplex virus type 1. Br J Ophthalmol. 2000;84(9):968–972. doi: 10.1136/bjo.84.9.968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Woodland RM, Darougar S, Thaker U, et al. Causes of conjunctivitis and keratoconjunctivitis in Karachi, Pakistan. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1992;86(3):317–320. doi: 10.1016/0035-9203(92)90328-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fitch CP, Rapoza PA, Owens S, et al. Epidemiology and diagnosis of acute conjunctivitis at an inner-city hospital. Ophthalmology. 1989;96(8):1215–1220. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(89)32749-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Høvding G. Acute bacterial conjunctivitis. Acta Ophthalmol. 2008;86(1):5–17. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0420.2007.01006.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bielory BP, O’Brien TP, Bielory L. Management of seasonal allergic conjunctivitis: guide to therapy. Acta Ophthalmol. 2012;90(5):399–407. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-3768.2011.02272.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.American Academy of Ophthalmology. Cornea/External Disease Panel . Preferred Practice Pattern Guidelines: Conjunctivitis-Limited Revision. American Academy of Ophthalmology; San Francisco, CA: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mannis MJ, Plotnik RD. Bacterial conjunctivitis. In: Tasman W, Jaeger EA, editors. Duanes Ophthalmology on CD-ROM. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cronau H, Kankanala RR, Mauger T. Diagnosis and management of red eye in primary care. Am Fam Physician. 2010;81(2):137–144. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sheikh A, Hurwitz B, van Schayck CP. McLean S, Nurmatov U. Antibiotics versus placebo for acute bacterial conjunctivitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;9:CD001211. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001211.pub3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Montero J, Perea E. A double-blind double-dummy comparison of topical lomefloxacin 0.3% twice daily with topical gentamicin 0.3% four times daily in the treatment of acute bacterial conjunctivitis. J Clin Res. 1998;1:29–39. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Papa V, Aragona P, Scuderi AC, et al. Treatment of acute bacterial conjunctivitis with topical netilmicin. Cornea. 2002;21(1):43–47. doi: 10.1097/00003226-200201000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lohr JA, Austin RD, Grossman M, Hayden GF, Knowlton GM, Dudley SM. Comparison of three topical antimicrobials for acute bacterial conjunctivitis. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1988;7(9):626–629. doi: 10.1097/00006454-198809000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Huerva V, Ascaso FJ, Latre B. Tolerancia y eficacia de la tobramicina topica vs cloranfenicol en el tratamiento de las conjunctivitis bacterianas. Ciencia Pharmaceutica. 1991;1:221–224. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Alves MRKJ. Evaluation of the clinical and microbiological efficacy of 0.3% ciprofloxacin drops and 0.3% tobramycin drops in the treatment of acute bacterial conjunctivitis. Rev Bras Oftalmol. 1993;52:371–377. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gallenga PE, Lobefalo L, Colangelo L, et al. Topical lomefloxacin 0.3% twice daily versus tobramycin 0.3% in acute bacterial conjunctivitis: a multicenter double-blind phase III study. Ophthalmologica. 1999;213(4):250–257. doi: 10.1159/000027430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jackson WB, Low DE, Dattani D, Whitsitt PF, Leeder RG, MacDougall R. Treatment of acute bacterial conjunctivitis: 1% fusidic acid viscous drops vs 0.3% tobramycin drops. Can J Ophthalmol. 2002;37(4):228–237. doi: 10.1016/s0008-4182(02)80114-4. discussion 237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bremond-Gignac D, Mariani-Kurkdjian P, Beresniak A, et al. Efficacy and safety of azithromycin 1.5% eye drops for purulent bacterial conjunctivitis in pediatric patients. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2010;29(3):222–226. doi: 10.1097/INF.0b013e3181b99fa2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Leibowitz HM. Antibacterial effectiveness of ciprofloxacin 0.3% ophthalmic solution in the treatment of bacterial conjunctivitis. Am J Ophthalmol. 1991;112((4)(suppl)):29S–33S. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gross RD, Hoffman RO, Lindsay RN. A comparison of ciprofloxacin and tobramycin in bacterial conjunctivitis in children. Clin Pediatr (Phila) 1997;36(8):435–444. doi: 10.1177/000992289703600801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Denis F, Chaumeil C, Goldschmidt P, et al. Micro-biological efficacy of 3-day treatment with azithromycin 1.5% eye-drops for purulent bacterial conjunctivitis. Eur J Ophthalmol. 2008;18(6):858–868. doi: 10.1177/112067210801800602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Silverstein BE, Allaire C, Bateman KM, et al. Efficacy and tolerability of besifloxacin ophthalmic suspension 0.6% administered twice daily for 3 days in the treatment of bacterial conjunctivitis: a multicenter, randomized, double-masked, vehicle-controlled, parallel-group study in adults and children. Clin Ther. 2011;33(1):13–26. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2010.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Karpecki P, Depaolis M, Hunter JA, et al. Besifloxacin ophthalmic suspension 0.6% in patients with bacterial conjunctivitis: a multicenter, prospective, randomized, double-masked, vehicle-controlled, 5-day efficacy and safety study. Clin Ther. 2009;31(3):514–526. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2009.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tepedino ME, Heller WH, Usner DW, et al. Phase III efficacy and safety study of besifloxacin ophthalmic suspension 0.6% in the treatment of bacterial conjunctivitis. Curr Med Res Opin. 2009;25(5):1159–1169. doi: 10.1185/03007990902837919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.McDonald MB, Protzko EE, Brunner LS, et al. Efficacy and safety of besifloxacin ophthalmic suspension 0.6% compared with moxifloxacin ophthalmic solution 0.5% for treating bacterial conjunctivitis. Ophthalmology. 2009;116(9):1615–1623. e1. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2009.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gong L, Sun XH, Qiu XD, et al. Comparative research of the efficacy of the gatifloxacin and levofloxacin for bacterial conjunctivitis in human eyes [in Chinese] Zhonghua Yan Ke Za Zhi. 2010;46(6):525–531. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hwang DG, Schanzlin DJ, Rotberg MH, et al. A phase III, placebo controlled clinical trial of 0.5% levofloxacin ophthalmic solution for the treatment of bacterial conjunctivitis. Br J Ophthalmol. 2003;87(8):1004–1009. doi: 10.1136/bjo.87.8.1004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schwab IR, Friedlaender M, McCulley J, et al. A phase III clinical trial of 0.5% levofloxacin ophthalmic solution versus 0.3% ofloxacin ophthalmic solution for the treatment of bacterial conjunctivitis. Ophthalmology. 2003;110(3):457–465. doi: 10.1016/S0161-6420(02)01894-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhang M, Hu Y, Chen F. Clinical investigation of 0.3% levofloxacin eyedrops on the treatment of cases with acute bacterial conjunctivitis and bacterial keratitis [in Chinese] Yan Ke Xue Bao. 2000;16(2):146–148. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gross RD, Lichtenstein SJ, Schlech BA. Early clinical and microbiological responses in the treatment of bacterial conjunctivitis with moxifloxacin ophthalmic solution 0.5% (Vigamox)using BID dosing. Todays Ther Trends. 2003;21:227–237. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Granet DB, Dorfman M, Stroman D, Cockrum P. A multicenter comparison of polymyxin B sulfate/trimethoprim ophthalmic solution and moxifloxacin in the speed of clinical efficacy for the treatment of bacterial conjunctivitis. J Pediatr Ophthalmol Strabismus. 2008;45(6):340–349. doi: 10.3928/01913913-20081101-07. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Epling J, Smucny J. Bacterial conjunctivitis. Clin Evid. 2005;2(14):756–761. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tabbara KF, El-Sheikh HF, Islam SM, Hammouda E. Treatment of acute bacterial conjunctivitis with topical lomefloxacin 0.3% compared to topical ofloxacin 0.3% Eur J Ophthalmol. 1999;9(4):269–275. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Abelson MB, Heller W, Shapiro AM, et al. Clinical cure of bacterial conjunctivitis with azithromycin 1%: vehicle-controlled, double-masked clinical trial. Am J Ophthalmol. 2008;145(6):959–965. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2008.01.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cochereau I, Meddeb-Ouertani A, Khairallah M, et al. 3-Day treatment with azithromycin 1.5% eye drops versus 7-day treatment with tobramycin 0.3% for purulent bacterial conjunctivitis: multicentre, randomised and controlled trial in adults and children. Br J Ophthalmol. 2007;91(4):465–469. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2006.103556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hallett JW, Leopold IH. Clinical trial of erythromycin ophthalmic ointment. Am J Ophthalmol. 1957;44(4 pt 1):519–522. doi: 10.1016/0002-9394(57)90152-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Trimethoprim-Polymyxin B Sulphate Ophthalmic Ointment Study Group Trimethoprim-polymyxin B sulphate ophthalmic ointment versus chloramphenicol ophthalmic ointment in the treatment of bacterial conjunctivitis. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1989;23(2):261–266. doi: 10.1093/jac/23.2.261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Workowski KA, Berman S, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines, 2010. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2010;59(RR-12):1–110. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sattar SA, Dimock KD, Ansari SA, Springthorpe VS. Spread of acute hemorrhagic conjunctivitis due to enterovirus-70: effect of air temperature and relative humidity on virus survival on fomites. J Med Virol. 1988;25(3):289–296. doi: 10.1002/jmv.1890250306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.O’Brien TP, Jeng BH, McDonald M, Raizman MB. Acute conjunctivitis: truth and misconceptions. Curr Med Res Opin. 2009;25(8):1953–1961. doi: 10.1185/03007990903038269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Skevaki CL, Galani IE, Pararas MV, et al. Treatment of viral conjunctivitis with antiviral drugs. Drugs. 2011;71(3):331–347. doi: 10.2165/11585330-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Katusic D, Petricek I, Mandic Z, et al. Azithromycin vs doxycycline in the treatment of inclusion conjunctivitis. Am J Ophthalmol. 2003;135(4):447–451. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(02)02094-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Owen CG, Shah A, Henshaw K, et al. Topical treatments for seasonal allergic conjunctivitis: systematic review and meta-analysis of efficacy and effectiveness. Br J Gen Pract. 2004;54(503):451–456. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Yaylali V, Demirlenk I, Tatlipinar S, et al. Comparative study of 0.1% olopatadine hydrochloride and 0.5% ketorolac tromethamine in the treatment of seasonal allergic conjunctivitis. Acta Ophthalmol Scand. 2003;81(4):378–382. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0420.2003.00079.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Donshik PC, Pearlman D, Pinnas J, et al. Efficacy and safety of ketorolac tromethamine 0.5% and levocabastine 0.05%: a multicenter comparison in patients with seasonal allergic conjunctivitis. Adv Ther. 2000;17(2):94–102. doi: 10.1007/BF02854842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Greiner JV, Udell IJ. A comparison of the clinical efficacy of pheniramine maleate/naphazoline hydrochloride ophthalmic solution and olopatadine hydrochloride ophthalmic solution in the conjunctival allergen challenge model. Clin Ther. 2005;27(5):568–577. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2005.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Greiner JV, Minno G. A placebo-controlled comparison of ketotifen fumarate and nedocromil sodium ophthalmic solutions for the prevention of ocular itching with the conjunctival allergen challenge model. Clin Ther. 2003;25(7):1988–2005. doi: 10.1016/s0149-2918(03)80200-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Greiner JV, Michaelson C, McWhirter CL, Shams NB. Single dose of ketotifen fumarate 025% vs 2 weeks of cromolyn sodium 4% for allergic conjunctivitis. Adv Ther. 2002;19(4):185–193. doi: 10.1007/BF02848694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Butrus S, Greiner JV, Discepola M, Finegold I. Comparison of the clinical efficacy and comfort of olopatadine hydrochloride 0.1% ophthalmic solution and nedocromil sodium 2% ophthalmic solution in the human conjunctival allergen challenge model. Clin Ther. 2000;22(12):1462–1472. doi: 10.1016/s0149-2918(00)83044-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Deschenes J, Discepola M, Abelson M. Comparative evaluation of olopatadine ophthalmic solution (0.1%) versus ketorolac ophthalmic solution (0.5%) using the provocative antigen challenge model. Acta Ophthalmol Scand Suppl. 1999;(228):47–52. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0420.1999.tb01174.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Gibbons RJ, Smith S, Antman E, American College of Cardiology. American Heart Association American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association clinical practice guidelines, part I. Circulation. 2003;107(23):2979–2986. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000063682.20730.A5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Rietveld RP, van Weert HC, ter Riet G, Bindels PJ. Diagnostic impact of signs and symptoms in acute infectious conjunctivitis: systematic literature search. BMJ. 2003;327(7418):789. doi: 10.1136/bmj.327.7418.789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Yannof J, Duker JS, editors. Ophthalmology. 2nd ed Mosby; Spain: 2004. Disorders of the conjunctiva and limbus; pp. 397–412. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Morrow GL, Abbott RL. Conjunctivitis. Am Fam Physician. 1998;57(4):735–746. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Rietveld RP, ter Riet G, Bindels PJ, Sloos JH, van Weert HC. Predicting bacterial cause in infectious conjunctivitis. BMJ. 2004;329(7459):206–210. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38128.631319.AE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Tarabishy AB, Jeng BH. Bacterial conjunctivitis: a review for internists. Cleve Clin J Med. 2008;75(7):507–512. doi: 10.3949/ccjm.75.7.507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Sambursky R, Tauber S, Schirra F, et al. The RPS adeno detector for diagnosing adenoviral conjunctivitis. Ophthalmology. 2006;113(10):1758–1764. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2006.06.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Epling J. Bacterial conjunctivitis. Clin Evid (Online) 2010;2010 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Mahmood AR, Narang AT. Diagnosis and management of the acute red eye. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 2008;26(1):35–55. vi. doi: 10.1016/j.emc.2007.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Azar MJ, Dhaliwal DK, Bower KS, et al. Possible consequences of shaking hands with your patients with epidemic keratoconjunctivitis. Am J Ophthalmol. 1996;121(6):711–712. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(14)70640-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Warren D, Nelson KE, Farrar JA, et al. A large outbreak of epidemic keratoconjunctivitis: problems in controlling nosocomial spread. J Infect Dis. 1989;160(6):938–943. doi: 10.1093/infdis/160.6.938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Wilhelmus KR. Diagnosis and management of herpes simplex stromal keratitis. Cornea. 1987;6(4):286–291. doi: 10.1097/00003226-198706040-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Puri LR, Shrestha GB, Shah DN, Chaudhary M, Thakur A. Ocular manifestations in herpes zoster ophthalmicus. Nepal J Ophthalmol. 2011;3(2):165–171. doi: 10.3126/nepjoph.v3i2.5271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Sy A, McLeod SD, Cohen EJ, et al. Practice patterns and opinions in the management of recurrent or chronic herpes zoster ophthalmicus. Cornea. 2012;31(7):786–790. doi: 10.1097/ICO.0b013e31823cbe6a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Sheikh A, Hurwitz B. Topical antibiotics for acute bacterial conjunctivitis: Cochrane systematic review and meta-analysis update. Br J Gen Pract. 2005;55(521):962–964. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Szaflik J, Szaflik JP, Kaminska A, Levofloxacin Bacterial Conjunctivitis Dosage Study Group Clinical and microbiological efficacy of levofloxacin administered three times a day for the treatment of bacterial conjunctivitis. Eur J Ophthalmol. 2009;19(1):1–9. doi: 10.1177/112067210901900101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Shanmuganathan VA, Armstrong M, Buller A, Tullo AB. External ocular infections due to methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) Eye (Lond) 2005;19(3):284–291. doi: 10.1038/sj.eye.6701465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Freidlin J, Acharya N, Lietman TM, et al. Spectrum of eye disease caused by methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Am J Ophthalmol. 2007;144(2):313–315. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2007.03.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Postema EJ, Remeijer L, van der Meijden WI. Epidemiology of genital chlamydial infections in patients with chlamydial conjunctivitis. Genitourin Med. 1996;72(3):203–205. doi: 10.1136/sti.72.3.203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Kumaresan JA, Mecaskey JW. The global elimination of blinding trachoma: progress and promise. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2003;69((5)(suppl)):24–28. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.2003.69.24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Avery RK, Baker AS. Albert and Jakobiec’s Principle and Practice of Ophthalmology. 3rd ed Saunders Elsevier; Philadelphia, PA: 2008. Chlamydial disease; pp. 4791–4801. [Google Scholar]

- 81.Rosario N, Bielory L. Epidemiology of allergic conjunctivitis. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011;11(5):471–476. doi: 10.1097/ACI.0b013e32834a9676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Bielory L. Allergic conjunctivitis: the evolution of therapeutic options. Allergy Asthma Proc. 2012;33(2):129–139. doi: 10.2500/aap.2012.33.3525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Baudouin C. Allergic reaction to topical eyedrops. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2005;5(5):459–463. doi: 10.1097/01.all.0000183112.86181.9e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Newburger JW, Takahashi M, Gerber MA, et al. Diagnosis, treatment, and long-term management of Kawasaki disease: a statement for health professionals from the Committee on Rheumatic Fever, Endocarditis, and Kawasaki Disease, Council on Cardiovascular Disease in the Young, American Heart Association. Pediatrics. 2004;114(6):1708–1733. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-2182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Gregory DG. The ophthalmologic management of acute Stevens-Johnson syndrome. Ocul Surf. 2008;6(2):87–95. doi: 10.1016/s1542-0124(12)70273-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Miller NR. Diagnosis and management of dural carotid-cavernous sinus fistulas. Neurosurg Focus. 2007;23(5):13. doi: 10.3171/FOC-07/11/E13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]