One Sentence Summary

Virtual reality reveals how sensory cues differentially influence hippocampal activity, theta rhythm, place cells and phase precession

The hippocampal cognitive map is thought to be driven by distal visual cues and self-motion cues. However, other sensory cues also influence place cells. Hence, we measured hippocampal activity in virtual reality (VR), where only distal visual and non-vestibular self-motion cues provided spatial information, and in the real world (RW). In VR place cells showed robust spatial selectivity, however only 20% were track active, compared to 45% in the RW. This indicates that distal visual and nonvestibular self-motion cues are sufficient to provide selectivity, but vestibular and other sensory cues present in RW are necessary to fully activate the place cell population. Additionally, bidirectional cells preferentially encoded distance along the track in VR, while encoding absolute position in RW. Taken together these results suggest the differential contributions of these sensory cues in shaping the hippocampal population code. Theta frequency was reduced and its speed dependence was abolished in VR but phase precession was unaffected, constraining mechanisms governing both hippocampal theta oscillations and temporal coding. These results reveal cooperative and competitive interactions between sensory cues for control over hippocampal spatiotemporal selectivity and theta rhythm.

Spatial navigation and hippocampal activity are influenced by three broad categories of stimuli: distal visual cues(1,2); self-motion cues(3, 4), e.g. proprioception, optic flow, and vestibular cues (5); and other sensory cues(6,7,8), e.g. olfaction(6, 7), audition(9), and somatosensation(10). While the cognitive map is thought to be primarily driven by distal visual, and self-motion cues(11), their contributions are difficult to assess in RW. Hence, we developed a noninvasive VR (Fig S3) for rats where the vestibular and other sensory cues did not provide any spatial information. Consequently, we will refer only to proprioception and optic flow as ‘self-motion cues’, and vestibular inputs will be treated separately. Place cells have been measured in VR in head fixed mice(12, 13) and are thought to be similar in VR and RW but this has not been tested. We used tetrodes to measure neural activity from the dorsal CA1 of six rats while they ran in VR or RW environments consisting of a linear track in the center of a square room with distinct distal visual cues on each of the four walls (Fig 1A). The visual scene was passively turned when rats reached the end of the virtual track. The distal visual cues were nearly identical in VR and RW, but rats were body fixed in VR which eliminated spatially informative other sensory cues and minimized both angular and linear vestibular inputs (Fig S4, see methods). Thus, the only spatially informative cues in VR during track running were distal visual and self-motion cues, as defined above. During recordings rats ran consistently along the track and reliably slowed before reaching the track end in both VR and RW (Fig 1B, see methods). Although their running speed was somewhat lower in VR than RW, their behavioral performance was similar.

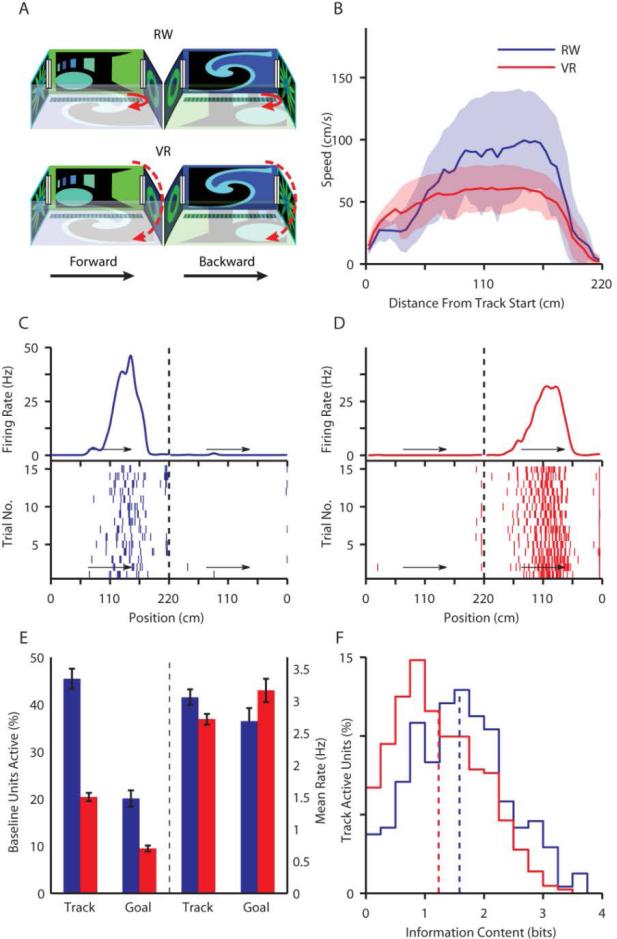

Fig 1.

Large reduction of track active cells in VR without comparable reduction in firing rates. A) Schematic of the task environment and distal visual cues in VR and RW. Rats turned themselves around in RW, while the scene was passively reversed in VR. B) Running speed (mean± STD) of rats as a function of position on a 2.2m long linear track for RW (blue) and VR (red). Similar color scheme is used throughout. While the rats were faster in RW, their behavior was similar, reliably reducing speed prior to reaching the end of the track (n=49 sessions in RW, n=128 sessions in VR). C) Example of a directional, stable place cell recorded in RW with firing rate (top panel), and raster plot (bottom panel). Arrows indicate running direction. D) A similar place cell recorded in VR. E) Comparison of activation ratio and firing rates of active cells on track (RW: 45.5%, 3.06 ± 0.12 Hz, VR: 20.4%, 2.71 ± 0.08 Hz) and at goal (RW: 20.1%, 2.68 ± 0.20 Hz, VR: 9.5%, 3.16 ± 0.18 Hz). F) Spatial information content across 432 track active cells in VR (1.23 ± 0.03 bits, n=432) was significantly lower (22%, p<10-7) than in 240 RW cells (1.58 ± 0.05 bits, n=240).

Clear, spatially focused and directionally tuned place fields, commonly found in RW (Fig 1C), were also found in VR (Fig 1D)(12). Almost all track active putative pyramidal cells had significant spatial information in VR (96 %) and RW (99 %). Thus, distal visual and self-motion cues are sufficient to generate the hippocampal rate code or cognitive map. We then examined whether the cognitive maps were similar in VR and RW.

We measured the activities of 2119 and 528 putative pyramidal neurons in the baseline sessions, conducted in a sleep box, preceding the VR and RW tasks respectively (see methods). Of these, 45.5% were track active in RW. In contrast, only 20.4% were track active in VR (Fig 1E, Fig S5). The VR track active cells had only slightly smaller mean firing rates (VR: 2.71 ± 0.08 Hz, n=432, RW: 3.06 ± 0.12 Hz, n=240, p<0.05), which is likely due to lower running speed(14). While the track active cells were measured during locomotion, we also investigated the place cell activation during periods of immobility at the goal locations, where a similar twofold reduction was seen in the proportion of active cells in VR, with no significant change in firing rates (Table S1, Fig 1E).

The firing rate maps of place cells were slightly less stable in VR (stability index 0.80 ± 0.01, n=432) than RW (0.87 ± 0.01, n=240). Hence, all subsequent comparisons were made across only the 392 and 227 track active, stable cells (Fig S6, see methods) in VR and RW respectively. Place fields were 26% wider (p<10-10) in VR (55.8 ± 1.2 cm, n=482) compared to RW (44.3 ± 1.4 cm, n=365). As a result, spatial selectivity was 22% lower in VR (Fig 1F, Fig S7 and Table S1). Further, 90% (75%) of track active cells had at least one place field in RW (VR), and place fields had comparable and significantly asymmetric shapes in both VR and RW such that the firing rates were higher at the end of a place field than at the beginning (Table S1)(12, 15, 19).

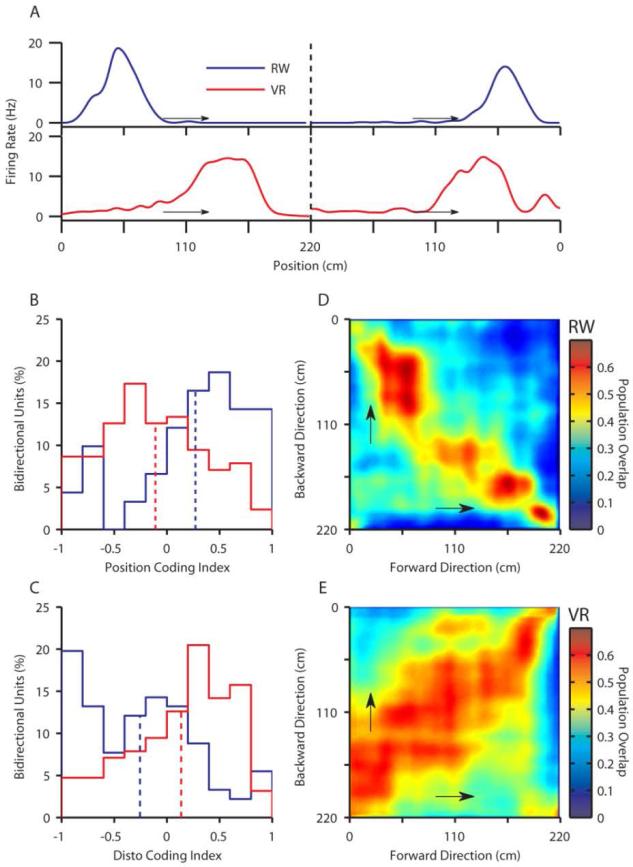

We then investigated the directionality of place cells in VR. As in RW(14), the majority of place cells were directional, spiking mostly in one running direction (Fig 1C-D). In fact, the distributions of directionality index were identical (Fig S7 and Table S1). But, bidirectional cells (40% in VR and 43% in RW), which had substantial activity along both running directions, showed different behavior in RW and VR (Fig 2A). Bidirectional cells fired around the same absolute position on the track in both running directions in RW (Fig 2A)(6)(16), expressing a position code. In contrast, bidirectional cells in VR fired around the same distance from the start position in both running directions (Fig 2A), indicative of a disto-code. The position code index (see methods) was significantly positive in RW but significantly negative in VR, indicating a position code in RW and its absence in VR (Fig 2B). Exactly the opposite was true for the disto-code (Fig 2C). Analysis of trials run at different speeds showed that spiking was more correlated with distance along the track than the duration of running, suggesting that it is distance run rather than time that determined these cells’ activity (Fig S8).

Fig. 2.

Bidirectional place cells exhibit position code in RW but disto-code in VR. A) Firing rate maps along both running directions for bidirectional cells in RW (top) and VR (bottom). Top panel depicts a position coding cell firing at the same position in both running directions. Bottom panel depicts a disto-coding cell firing at the same distance in both directions. B) Position code index is significantly positive in RW (0.27±0.05, p<10-6, n=91) but significantly negative in VR (-0.11±0.04, p<0.05, n=127). C) The disto-code index is significantly positive in VR (0.14±0.04, p<0.001, n=127) but significantly negative in RW (-0.25±0.06, p<10-4, n=91). The position code index is significantly greater in RW than VR (p<10-7) while disto-code index is significantly greater in VR (p<10-6). D) Similarity of the population of 91 bidirectional cells in RW between two movement directions was computed using the population vector overlap (see methods). Each colored pixel shows the vector overlap between two positions in opposite running directions. Note the clear increase in overlap along the -45° diagonal indicating spiking at the same position. E) As in D, for the population of 127 bidirectional cells in VR. Note the clear increase in overlap along the +45° diagonal, indicating spiking at the same distance in both running directions.

To assess these results at the population level, we performed population vector overlap analysis (Fig 2D-E, Fig S9, see methods). The population of bidirectional cells spiked around the same absolute position on the track in two movement directions in RW, indicated by a significant increase in population vector overlap along the -45° diagonal (Fig 2D). There was no significant overlap along +45° (at the same distance along two directions) in RW. The opposite was true in VR (Fig 2E), with significant overlap along +45° and no significant overlap along -45°. Thus the disto and position codes were present at the population level in VR and RW respectively, but not vice versa.

Examination of the same cells recorded in both VR and RW revealed that their mean firing rates, spatial information and directionality index were correlated between the environments, but the position of their place fields was unrelated (Fig S10-11). In the same bidirectional cells, the disto-code index was greater in VR than in RW, and the position code index was greater in RW than VR (Fig S12).

Having examined the rate-code, we investigated the temporal features(12, 17–20) of place cells. The frequency of theta rhythm (see methods) in the local field potential (LFP) during locomotion was reduced in VR compared to RW (Fig 3A). Despite this, VR cells showed clear phase precession, comparable to RW (Fig 3B-C). Indeed, across the ensemble of data, the LFP theta frequency within place fields was 8.7% lower in VR compared to RW (Fig 3D), yet there was no significant difference in the quality of phase precession between the two conditions (Fig 3E). As a result, the frequency of theta modulation of spiking of place cells (12, 17–21) was also significantly reduced in VR (Fig S13). Thus the frequency of theta rhythm is different in VR and RW, but it has no impact on the hippocampal temporal code.

Fig. 3.

Reduced theta frequency in VR without significant change in phase precession. A) Autocorrelation function of sample hippocampal LFPs in RW and VR showing significant increase in theta period in VR. Both LFPs are recorded from same electrode on the same day. B) Representative place field in RW showing clear phase precession. C) Representative place field in VR showing clear phase precession. D) Infield theta frequency of place fields in VR (7.53 ± 0.02 Hz, n=251) was significantly less (8.7%, p<10-10, n=204) than that of place fields in RW (8.25 ± 0.03 Hz, n=204). E) Quality of phase precession, measured by position-phase linear-circular correlation, in RW (0.33 ± 0.01) was not significantly different (p=0.8) from precession in VR (0.33 ± 0.01).

Theta frequency was significantly lower in VR than RW at all running speeds (Fig 4A-B). Across the ensemble, theta frequency increased with running speed in RW but this was abolished in VR (Fig 4B). We thus computed the speed dependence of theta frequency for each electrode within each session (see methods). Noisy but clear speed dependent increase in theta frequency was found within single LFP data in RW (Fig 4C), but not in VR (Fig 4D). These calculations of the single cycle theta frequency could be influenced by noise, which could especially distort the low amplitude theta and provide erroneous results. Hence, we restricted the analysis to only high amplitude theta cycles (see methods). A large majority (85.4%) of LFPs in RW showed significant correlation between running speed and theta frequency but this was abolished in VR (Fig 4E, Fig S14-15). In contrast, theta amplitude showed identical correlation with running speed in both conditions (Fig 4F).

Fig 4.

Absence of theta frequency speed dependence in VR. A) Sample theta cycles during high (>50cm/s) and low (<10cm/s) running speed in RW and VR from the same electrode as Fig 3A. Bold lines are filtered between 4 and 12 Hz, narrow lines are unfiltered traces (see Fig S15). B) Population average (mean ± s.e.m) speed dependence of theta frequency from 287 LFPs in RW and 681 LFPs in VR. C) Density map of individual theta cycle frequencies and corresponding speeds from a single LFP in RW (correlation=0.13, p<10-10). D) As in C, for the same electrode in VR on the same day (correlation=0.01, p=0.48). E) The population of LFPs in RW shows significant correlation between theta frequency and speed (0.21 ± 0.01, p < 10-10), while the population of LFPs in VR shows no significant correlation (-0.01 ± 0.01, p<0.01). F) Theta cycle amplitude is similarly (p=0.8) correlated with speed in both RW (0.16 ± 0.01) and VR (0.16 ± 0.01).

The key findings were qualitatively true within each animal. In particular, within each animal the disto (position) index was positive (negative) in VR, and negative (positive) in RW, a substantially greater fraction of cells were active in RW than VR and theta frequency was greater in RW than VR. Further, control experiments show that the disto-code was not driven by salient reward indicating cues in the environment (Fig S16-17); was present in both passive and active turning protocols (Fig S18) and was consistent between slow and fast trials in VR (Fig S19).

These results reveal several important aspects of the sensory mechanisms governing hippocampal rate and temporal codes. Comparable levels of spatial selectivity and firing rates of track active cells in VR and RW, as well as comparable strength of temporal code all show that a robust cognitive map can indeed be formed with only distal visual and self-motion cues providing spatial information. However these cues alone do not determine the location of place fields between VR and RW, as shown by the differences in ratemaps of the same cells.

The VR and RW environments had similar dimensions and nearly identical distal visual cues, and the rats’ behavior was similar in the two conditions. Thus, these factors are unlikely to cause the observed differences in place cell activity between VR and RW. Several other factors could potentially contribute, in particular the absence of spatial information in vestibular and other sensory cues, or conflicts of other sensory cues with distal visual or self-motion cues in VR. One potential consequence of conflicting cues could be reference frame switching (between virtual and real space) occurring randomly along the track, resulting in loss of spatial selectivity in VR. The overwhelming presence of significant spatial information in cells recorded in VR argues against this possibility. Instead, these results suggest that additional sensory cues present in RW are necessary for the activation of a subpopulation of CA1 place cells, such that their removal reduces the activation of place cells without altering the firing rates of active cells. In VR spatial information is provided by only distal visual and self-motion cues, which likely change more slowly than spatially informative proximal cues, such as odors along the track in RW. This could make place fields wider in VR, reducing their information content.

The switch in coding observed in the bidirectional cell population is analogous to a previous report of different hippocampal cell response types (4), which implies either distinct classes of principal cells or alternate responses from the same cells depending on the task. The latter seems to be more likely in our data since comparisons between VR and RW show that the same hippocampal cell can acquire a different form of representation given a different subset of inputs. We cannot rule out the possibility that higher order cognitive process may influence the place cell code; however it is likely that sensory inputs play a key role in our results. Similar levels of directional tuning in VR and RW suggests that distal visual cues, which are the only cues that differ along two movement directions on the track in VR, are sufficient to generate directional firing on a linear track. Vestibular inputs are not required for generating spatially selective, directional place cells, in contrast to previous lesion based studies(5). The vestibular cues are present and identical along two movement directions in RW, therefore their presence, not their absence, should contribute to a disto-code (Fig S20, Fig S21). Bidirectional cells in RW exhibit position code(16), which is enhanced by the addition of odors and textures(6). These points suggest proximal cues in RW are the most likely to generate the position code. Bidirectional cells in VR exhibit disto-code, and are likely governed by self-motion cues, which are the only cues that are similar along the two movement directions. Finally, we hypothesize that other sensory cues present in RW have a veto power over self-motion cues in determining the bidirectional code.

While disto-code has been reported on a single unit level in RW(3, 22), we do not see significant disto-code in the RW population. Further, the effect of self-motion cues on the hippocampal population code and the suggested competitive interaction between self-motion and other sensory cues are surprising. Such competitive effects between different sensory modalities may be driven by inhibitory mechanisms across multimodal inputs, as seen recently in the primary visual cortex(23), suggesting their broader applicability. We hypothesize that some other sensory cues reach CA1 via the lateral entorhinal cortex (LEC), because LEC neurons respond to local cues such as objects(24), while distal visual and self-motion cues reach CA1 via the medial entorhinal cortex (MEC) grid cells, which are influenced by these cues(25). Consistently, both LEC and MEC project directly and indirectly to CA1 and differentially modulate CA1 activity in vivo during sleep(26), and engage local inhibition(27). The competitive interactions governing the behavior of bi-directional cells in VR and RW may therefore be the result of inhibitory interactions between the LEC and MEC pathways.

Theta frequency was significantly reduced in VR, corroborating earlier results that vestibular inputs contribute to theta frequency(28), and its speed dependence was abolished. On the other hand, theta power had similar speed dependence in VR and RW suggesting that theta power is largely governed by distal visual and self-motion cues. Despite the large changes in theta frequency and its speed dependence, phase precession was intact in VR(12), and its quality was identical in RW and VR, indicating that distal visual and self-motion cues are sufficient to generate a robust temporal code. Our results place restrictions on theories of phase precession that depend on the precise value of theta frequency or its speed dependence(17, 29–31). Instead they favor alternative mechanisms that are insensitive to these phenomena(15, 18, 19), that apply equally to networks with diverse connectivity patterns such as the entorhinal cortex and CA1, and hence do not require recurrent excitatory connections(15, 19). These results thus provide insight about how distinct sensory cues cooperate and compete to influence theta rhythm and hippocampal spatiotemporal selectivity.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the NSF Career award and grants from: NIH 5R01MH092925-02 and the W. M. Keck foundation to MRM. These findings were presented as two abstracts and posters at the Society for Neuroscience Meeting entitled: P. Ravassard, B. Willers, A. L. Kees, D. Ho, D. Aharoni, M. R. Mehta, ‘Directional tuning of place cells in rats performing a virtual landmark navigation task’, Soc. Neurosci. Abs. # 812.05 (2012). A. Kees, B. Willers, P.M. Ravassard, D. Ho, D. Aharoni, M. R. Mehta, ‘Hippocampal rate and temporal codes in a virtual visual navigation task’, Soc. Neurosci. Abs. # 812.07 (2012).

References and Notes

- 1.O'Keefe J, Dostrovsky J. The hippocampus as a spatial map: Preliminary evidence from unit activity in the freely-moving rat. Brain Research. 1971;34:171–175. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(71)90358-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Muller RU, Kubie JL. The effects of changes in the environment on the spatial firing of hippocampal complex-spike cells. J Neurosci. 1987;7:1951–68. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.07-07-01951.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gothard KM, Skaggs WE, Moore KM, McNaughton BL. Binding of hippocampal CA1 neural activity to multiple reference frames in a landmark-based navigation task. J Neurosci. 1996;16:823–35. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-02-00823.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pastalkova E, Itskov V, Amarasingham A, Buzsaki G. Internally generated cell assembly sequences in the rat hippocampus. Science. 2008;321:1322–1327. doi: 10.1126/science.1159775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stackman RW, Clark AS, Taube JS. Hippocampal spatial representations require vestibular input. Hippocampus. 2002;12:291–303. doi: 10.1002/hipo.1112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Battaglia FP, Sutherland GR, McNaughton BL. Local sensory cues and place cell directionality: additional evidence of prospective coding in the hippocampus. J Neurosci. 2004;24:4541–4550. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4896-03.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wood ER, Dudchenko PA, Eichenbaum H. The global record of memory in hippocampal neuronal activity. Nature. 1999;397:613–6. doi: 10.1038/17605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Save E, Nerad L, Poucet B. Contribution of multiple sensory information to place field stability in hippocampal place cells. Hippocampus. 2000;10:64–76. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-1063(2000)10:1<64::AID-HIPO7>3.0.CO;2-Y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Itskov PM, Vinnik E, Honey C, Schnupp JWH, Diamond ME. Sound sensitivity of neurons in rat hippocampus during performance of a sound-guided task. Journal of Neurophysiology. 2012 doi: 10.1152/jn.00404.2011. doi:10.1152/jn.00404.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Young BJ, Fox GD, Eichenbaum H. Correlates of hippocampal complex-spike cell activity in rats performing a nonspatial radial maze task. The Journal of neuroscience: the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 1994;14:6553–63. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.14-11-06553.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.O'Keefe J, Nadel L. The hippocampus as a cognitive map. Clarendon Press; Oxford: 1978. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Harvey CD, Collman F, Dombeck DA, Tank DW. Intracellular dynamics of hippocampal place cells during virtual navigation. Nature. 2009;461:941–946. doi: 10.1038/nature08499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dombeck DA, Harvey CD, Tian L, Looger LL, Tank DW. Functional imaging of hippocampal place cells at cellular resolution during virtual navigation. Nat Neurosci. 2011;13:1433–1440. doi: 10.1038/nn.2648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McNaughton BL, Barnes CA, O'Keefe J. The contributions of position, direction, and velocity to single unit activity in the hippocampus of freely-moving rats. Exp Brain Res. 1983;52:41–49. doi: 10.1007/BF00237147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mehta MR, Quirk MC, Wilson MA. Experience-dependent asymmetric shape of hippocampal receptive fields. Neuron. 2000;25:707–15. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)81072-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Resnik E, McFarland JM, Sprengel R, Sakmann B, Mehta MR. The Effects of GluA1 Deletion on the Hippocampal Population Code for Position. The Journal of neuroscience: the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 2012;32:8952–68. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.6460-11.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.O'Keefe J, Recce ML. Phase relationship between hippocampal place units and the EEG theta rhythm. Hippocampus. 1993;3:317–30. doi: 10.1002/hipo.450030307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.V Tsodyks M, Skaggs WE, Sejnowski TJ, McNaughton BL. Population dynamics and theta rhythm phase precession of hippocampal place cell firing: a spiking neuron model. Hippocampus. 1996;6:271–280. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-1063(1996)6:3<271::AID-HIPO5>3.0.CO;2-Q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mehta MR, Lee AK, Wilson MA. Role of experience and oscillations in transforming a rate code into a temporal code. Nature. 2002;417:741–6. doi: 10.1038/nature00807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hafting T, Fyhn M, Bonnevie T, Moser MB, Moser EI. Hippocampus-independent phase precession in entorhinal grid cells. Nature. 2008;453:1248–1252. doi: 10.1038/nature06957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Geisler C, Robbe D, Zugaro M, Sirota A, Buzsáki G. Hippocampal place cell assemblies are speed-controlled oscillators. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2007;104:8149–8154. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0610121104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mizuseki K, Royer S, Diba K, Buzsáki G. Activity dynamics and behavioral correlates of CA3 and CA1 hippocampal pyramidal neurons. Hippocampus. 2012;22:1659–1680. doi: 10.1002/hipo.22002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Iurilli G, et al. Sound-Driven Synaptic Inhibition in Primary Visual Cortex. Neuron. 2012;73:814–828. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.12.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Deshmukh SS, Knierim JJ. Representation of non-spatial and spatial information in the lateral entorhinal cortex. Frontiers in behavioral neuroscience. 2011;5:69. doi: 10.3389/fnbeh.2011.00069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hafting T, Fyhn M, Molden S, Moser MB, Moser EI. Microstructure of a spatial map in the entorhinal cortex. Nature. 2005;436:801–806. doi: 10.1038/nature03721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hahn TTG, McFarland JM, Berberich S, Sakmann B, Mehta MR. Spontaneous persistent activity in entorhinal cortex modulates cortico-hippocampal interaction in vivo. Nature Neuroscience. 2012 doi: 10.1038/nn.3236. doi:10.1038/nn.3236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hahn TT, Sakmann B, Mehta MR. Phase-locking of hippocampal interneurons’ membrane potential to neocortical up-down states. Nat Neurosci. 2006;9:1359–1361. doi: 10.1038/nn1788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Russell NA, Horii A, Smith PF, Darlington CL, Bilkey DK. Lesions of the vestibular system disrupt hippocampal theta rhythm in the rat. Journal of neurophysiology. 2006;96:4–14. doi: 10.1152/jn.00953.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Burgess N. Grid cells and theta as oscillatory interference: theory and predictions. Hippocampus. 2008;18:1157–1174. doi: 10.1002/hipo.20518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hasselmo ME, Giocomo LM, Zilli EA. Grid cell firing may arise from interference of theta frequency membrane potential oscillations in single neurons. Hippocampus. 2007;17:1252–1271. doi: 10.1002/hipo.20374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Blair HT, Welday AC, Zhang K. Scale-invariant memory representations emerge from moire interference between grid fields that produce theta oscillations: a computational model. J Neurosci. 2007;27:3211–3229. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4724-06.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.