Summary

Tendon lesions are among the most frequent musculoskeletal pathologies. Vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) is known to regulate angiogenesis. VEGF-111, a biologically active and proteolysis-resistant splice variant of this family, was recently identified. This study aimed at evaluating whether VEGF-111 could have a therapeutic interest in tendon pathologies. Surgical section of one Achilles tendon of rats was performed before a local injection of either saline or VEGF-111. After 5, 15 and 30 days, the Achilles tendons of 10 rats of both groups were sampled and submitted to a biomechanical tensile test. The force necessary to induce tendon rupture was greater for tendons of the VEGF-111 group (p<0.05) while the section areas of the tendons were similar. The mechanical stress was similar at 5 and 15 days in the both groups but was improved for the VEGF-111 group at day 30 (p <0.001). No difference was observed in the mRNA expression of collagen III, tenomodulin and MMP-9. In conclusion, we observed that a local injection of VEGF-111 improves the early phases of the healing process of rat tendons after a surgical section. Further confirmatory experimentations are needed to consolidate our results.

Keywords: biomechanical, growth factor, healing, tendon, VEGF, VEGF-111

Introduction

Tendinous lesions are among the most frequent pathologies in sportsmen and physical workers1. Tendinopathy often becomes chronic due to the current lack of conservative treatments1. It is therefore of interest to develop new treatments. Injection of platelet-rich plasma (PRP) seems to be a promising approach by releasing growth factors (GF) locally2. Among the GF released by activated platelets, the vascular endothelial growth factor-A (VEGF-A) is known to induce positive effects on vascular function and angiogenesis, and could be beneficial in the healing process of tendons3. Recently, a novel VEGF-A isoform was identified, the VEGF-111, a biologically active, diffusible and proteolysis-resistant VEGF-A splice variant generated by skipping the exons 5-73–5. Its expression is induced in several types of cells in vitro by genotoxic agents such as chemotherapeutic drugs and UV-B3,4. Recombinant VEGF-111 has been shown to significantly improve vascularization of grafted ovarian tissue6, and might present potential beneficial effects on ischemic diseases3. This prompted us to evaluate whether VEGF-111 could have a therapeutic interest within the framework of the tendon pathology.

Materials and methods

All experimental procedures and protocols used in this investigation were reviewed and approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Ethics Committee of the University of Liège (Belgium). The “Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals,” prepared by the Institute of Laboratory Animal Resources, National Research Council, and published by the National Academy Press, was followed carefully. Our study meets the etnical standards of the Journal7. We used an experimental protocol very similar to our previous study on the healing effect of PRP in tendon lesions of rats8.

Sixty Sprague-Dawley male rats of 2 months (weight ± 320 g) were used. Rats were weighed and anesthetized i.p. with pentobarbital (60 mg/kg of body weight). Buprenorphine (0.05 mg/kg of body weight) and tetracycline (15 μg/kg of body weight) were subcutaneously injected prior to surgery. Buprenorphin was administred again for 3 days. The complete surgical procedure was performed under aseptic conditions under a dissecting microscope. Skin of the left limb was shaved and incised laterally to the Achilles tendon. The Achilles tendon complex was exposed after dissection of the surrounding fascia. The plantaris tendon was removed to avoid mismeasurements during the biomechanical testing. The Achilles tendon was transversally cut 5mm proximal to its calcaneal insertion and a 5-mm segment was removed. The tendon was left unsutured with a gap between the tendon stumps. The fascia and the skin were sutured with resorbable yarn Vicryl 6/0 (Ethicon, Johnson & Johnson, New Brunswick, NJ). The animals were placed in clean cages under heating lamp until awakening and there was no postoperative immobilization. The rats were divided into “control” and “VEGF-111” groups that received 2 hours postoperatively a local injection (inside the defect) of 50 μL of a physiological solution (control group) or VEGF-111 (100 ng). They were checked daily and followed for well-being and a global observation of walk and activity.

Five, 15, or 30 days postsurgery, 10 rats of both groups were weighed and euthanized with pentobarbital (i.p., 200 mg/Kg). The healing tendon, with the attached calcaneal bone and a part of the triceps suralis, was dissected from surrounding tissues. The muscle-tendon-bone unit was fastened in the clamping device by freezing the muscular segment (triceps surae) with liquid nitrogen and clamping it between a “cryo-jaw” device9 and by fixing the bony segment between the lower clamp. The cross-sectional area of the samples was calculated from pictures made with a set of two cameras positioned perpendicular to each other. The traction test (106.2 kN, TesT GmbH, Dusseldorf, Germany) was started as soon as the expansion of the freezing zone reached the border of the metal clamp but did not extend into the tendon tissue. The displacement rate was set at a constant speed of 1 mm/s until rupture. Force vs displacement curves were recorded by a computer for subsequent data analysis. The force at rupture or ultimate tensile strength (UTS) was expressed in newtons (N). To account for the difference in the cross-sectional area of the healing tendons, the value of UTS was normalized to a unit area (megapascal, MPa) and represents the mechanical stress of the tissue.

Samples for biochemical analyses were taken directly after tendon rupture during the mechanical test, snap frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at −80°C until use. Isolation of total RNA from the samples was performed using the RNeasy Total RNA Kit (Qiagen, Venlo, the Netherlands). The expression of type III collagen (Col III), MMP 9 (MMP-9), and tenomodulin (TNMD) was measured by semi-quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) as described previously (using an internal synthetic standard RNA)8. Expression levels of mRNA were normalized to the level of 28S rRNA10.

Results are expressed as the mean ± standard deviation of the mean. The results were compared by a Friedman’s test and parametric post hoc test of Wilcox by using the statistical software Statistical Analysis System, version 9.1 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC) and a level of significance at p < 0.05.

Results

No significant difference in the body weight was observed between the control and the VEGF-111 treated group at the three time points of the experiment.

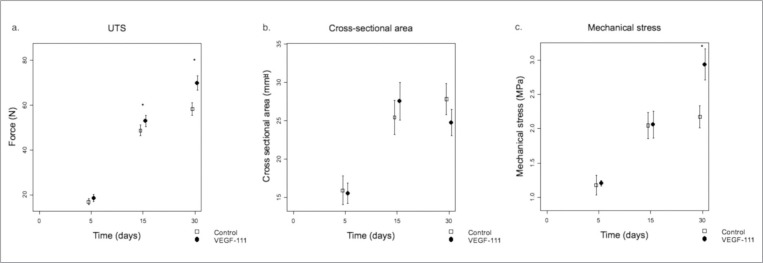

Five days after surgery, UTS was low in both control and VEGF-111 groups and significantly increased with time in both groups (p<0.0001) (Fig. 1a), above the basal normal values (42N)8. At day 15 and 30, the UTS was significantly higher in the VEGF-111 group (p<0.05).

Figure 1.

a) Breaking strength expressed in newton (N) recorded in control groups (n = 8 at each time point) and VEGF-111 groups (n = 10 at each time point) (mean ± SD) at increasing time after surgery (5, 15, and 30 days). *p-value < 0.05. b) Evolution of the cross-sectional area of the tendons (square millimeter) with time (mean ± SD, n = 10 at each time point). c) Calculated ratio between UTS and the surface area of the section of the tendon (mechanical stress in megapascal) at the 3 time points (mean ± SD, n = 10 at each time point). SD: standard deviation; UTS: ultimate tensile strength.

Five days after injury, the cross-sectional area of the tendon was similar in both groups, and continued to similarly enlarge at day 15. At day 30, it levelled off in the control group while it tended to decrease in the VEGF-111 group (Fig. 1b). As a consequence of the evolution of these parameters, the UTS per unit surface (mechanical stress) of the healing tissue was similar in both groups at day 5 and similarly increased at day 15. However, at day 30, the VEGF-111 group displayed significantly higher mechanical stress values (p <0.001) than the control group (Fig. 1c).

The expression of Col III mRNA was high during the first 2 weeks and then decreased at day 30 similarly in both groups (Tab. 1). The expression of TNMD was low at day 5, tended to increase at day 15 and to decrease slowly at day 30 (Tab. 1). The expression of mRNA coding for the MMP-9 was stable in both groups at the three time points but tended (p=0.15) to decrease in the VEGF-111 group after day 15 (Tab. 1).

Table 1.

Expression of mRNA (in arbitrary units per unit of 28S rRNA, AU) coding for Col III, TNMD and MMP-9. Col III: type III collagen; TNMD: tenomodulin, MMP9: matrix metalloproteinase 9.

| D5 | D15 | D30 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Col III | |||

| Control | 1.302 ± 0.173 | 1.058 ± 0.126 | 0.765 ± 0196 |

| VEGF-111 | 1.279 ± 0.076 | 1.044 ± 0.194 | 0.876 ± 0.291 |

|

| |||

| TNMD | |||

| Control | 0.336 ± 0.065 | 2.122 ± 0.273 | 1.509 ± 0.334 |

| VEGF-111 | 0.378 ± 0.144 | 1.897 ± 0.309 | 1.702 ± 0.157 |

|

| |||

| MMP-9 | |||

| Control | 1.548 ± 1.306 | 1.552 ± 0.549 | 1.418 ± 1.515 |

| VEGF-111 | 1.044 ± 0.757 | 1.176 ± 0.573 | 0.800 ± 0.661 |

Discussion

Platelets degranulation releases growth factors stored in their granules11. VEGF is one of these growth factors4, 12 and is known to induce positive effects on vascular function and angiogenesis4, 12. However, this growth factor would be also implicated in the physiopathology of tendinopathies. Indeed, a study which applied prolonged and repetitive loading on rabbit tendons showed that this mechanical stress lead to an increased production of VEGF by tendons cells along the outer regions of the loaded tendon13. These locations may be at-risk regions in the tendon that will ultimately demonstrate changes typical of tendinopathy. A study on human patellar tendons demonstrated that VEGF expression was higher in patients with a more recent patellar tendinopathy than in symptomatic patient suffering of tendinopathy for a longer time14. Authors concluded that VEGF may contribute to the vascular hyperplasia that is a cardinal feature of symptomatic tendinosis, particularly in patients with more recent onset. This expression of VEGF could reflect a tentative tendon healing process that would be inhibited by the repetitive mechanical loading. The application of VEGF-111 in acute tendon injury might therefore accelerate the healing process, in absence of mechanical overload.

VEGF-111 is a biologically active VEGF-A splicing isoform generated by the skipping of the exons 5–7 induced by genotoxic agents such as UV-B3, 4. Due to the lack of the proteolytic cleavage site in the exon 5, this variant is resistant to proteolysis and has a longer half-life than the classical VEGF-1655. In this study, we evaluated the influence of a single postoperative injection of 100 ng of VEGF-111 on the repair of ruptured Achilles tendon of rats by following mechanical and biochemical parameters as a function of time during the healing process, using the same experimental protocol as previously used in our study evaluating the effect of PRP on the tendon healing8.

Our mechanical tests showed that a VEGF-111 injection significantly improved the UTS of the healing Achilles tendons 15 and 30 days after surgery and the mechanical stress in the late phase (30 days) of the repair compared to the control group (Fig. 1 a, c). However, if we compare these results to our previous study8, we observed that PRP-treated tendons had a significantly higher UTS and greater cross-sectional area increasis as compared to VEGF-111. In this study, we did not observe any significant difference in the cross-sectional area of tendons of both groups (Fig. 1 b). The section area of the VEGF-111 treated tendons levelled off after day 15, similarly to the control group but tended to decrease at day 30. Altogether, this resulted in a similar improvement of the mechanical stress between the VEGF-111 and PRP-treated groups although likely through different mechanisms. VEGF-111 alone could perhaps induce less inflammation than PRP, due to the absence of chemokines, inflammatory mediators and other growth factors released by platelets, but could be enough to improve the mechanical resistance of tendons.

The expression of a selected number of genes relevant to tendon healing process was investigated such as Col III which is the main fibrillar collagen synthetized during the healing process, TNMD which is a marker of tenocyte differentiation and MMP-9 which is produced by inflammatory cells. No altered level of Col III mRNA, known to participate in the healing process neither of TNMD, expressed by differentiating tenocytes nor MMP-9 was observed in the VEGF-111-treated tendons (Tab. 1). However, a tendency, although not significant, to a decreased expression of MMP-9 mRNA was observed at day 30. MMP-9 is a marker of tissue remodeling. This observation could be explained by a decreased intratendinous inflammation and an advanced maturation of the healing process. This might support the improvement of the mechanical resistance of the VEGF-111 treated tendons. VEGF-165 has been reported to induce in tenocytes in vitro the expression of TGFβ1, a growth factor known to stimulate the production of extracellular matrix molecules15. Further investigations are needed to evaluate the induction of a similar mechanism by VEGF-111.

In opposition to the observations by Hou et al.16 who suggested that VEGF-165 might have a negative impact on tendon healing via vessel formation and destruction of the collagen network, and those of Sahin et al.17 who showed that biomechanical stability of the patellar tendons of rats was decreased 7 days after surgery concomitantly with an increase of VEGF and MMP-3, our study suggest that VEGF-111 could have a potential positive effect on the healing of tendon lesions in rats. This can be related to the different vascular patterning induced by VEGF-165 (large vascular lacunae) and VEG-F111 (numerous small capillaries) as previously described in tumors3, 5. The invasion of tendon by small capillaries could be similar to the vascularization occurring at the beginning of the healing process in tendon, while larger vessels would be observed in chronic tendons lesion. Moreover, this intratendinous vascularization could be more effective to transport all the needed substrates for healing than a more superficial vascularization. Furthermore, a recent study, on the anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) reconstruction, showed that VEGF may play a positive role in the ligamentization of the tendinous graft and healing process18. These authors observed that using hyaluronan as a releasing carrier of VEGF-165 can improve revascularization and bio-mechanical properties of allografts after ACL reconstruction, and decrease the recovery period. The in situ concentration of VEGF might also be a factor worth to consider.

Our study presents some limitations. It would have been interesting to investigate the elasticity and stiffness of the tendons besides their resistance to evaluate another parameter of the intrinsic quality of the healed tendons. We chose to measure the expression of collagen type III which is the main fibrillar collagen synthesized by tenocytes during repair process and not the type I collagen which is the predominant collagen found in the healthy tendons. However, the ratio Col I/Col III would be also a good indicator of the healing process, taking into account the phenotype switching during healing.

In conclusion, this preliminary experimentation showed that a 100ng injection of VEGF-111 stimulated tendon healing process as suggested by the increased ultimate force needed to rupture tendons during healing and the increased mechanical stress in comparison with the control group. Other experimentations with larger number of experimental animals and various concentrations of VEGF-111, possibly associated with eccentric work19, are needed to confirm these encouraging results.

Acknowledgments

This experimentation was partially financed by Lejeune-Lechien grant of the Léon Frédéricq Foundation. We thank Prof. Serge Cescotto of the Department ARGENCO (University of Liège, Belgium) for the loan of the materials for the biomechanical testing and Marie-Jeanne Nix of the Laboratory of Connective Tissues Biology (GIGA-R, University of Liège, Belgium) for biochemical analyses.

Footnotes

Jean-François Kaux and Lauriane Janssen contributed equally to the work.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Kaux JF, et al. Current opinion on tendinopathy. Journal of Sports Science and Medicine. 2011;10:238–253. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kaux JF, Crielaard JM. Platelet-rich plasma application in the management of chronic tendinopathies. Acta Orthop Belg. 2013;79(1):10–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mineur P, et al. Newly identified biologically active and proteolysis-resistant VEGF-A isoform VEGF111 is induced by genotoxic agents. J Cell Biol. 2007;179(6):1261–1273. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200703052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lambert CA, Mineur P, Nusgens BV. [VEGF111: Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde?] Med Sci (Paris) 2008;24(6–7):579–580. doi: 10.1051/medsci/20082467579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Delcombel R, et al. New prospects in the roles of the C-terminal domains of VEGF-A and their cooperation for ligand binding, cellular signaling and vessels formation. Angiogenesis. 2013;16(2):353–371. doi: 10.1007/s10456-012-9320-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Labied S, et al. Isoform 111 of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF111) improves angiogenesis of ovarian tissue xenotransplantation. Transplantation. 2013;95(3):426–433. doi: 10.1097/TP.0b013e318279965c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Padulo J, Oliva F, Frizziero A, Maffulli N. Muscle, Ligaments and Tendons Journal. Basic principles and recommendations in clinical and field science research. MLTJ. 2013;4:250–252. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kaux JF, et al. Effects of platelet-rich plasma (PRP) on the healing of Achilles tendons of rats. Wound Repair Regen. 2012;20(5):748–756. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-475X.2012.00826.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wieloch P, et al. A cryo-jaw designed for in vitro tensile testing of the healing Achilles endons in rats. J Biomech. 2004;37(11):1719–1722. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2004.01.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lambert CA, et al. Distinct pathways in the over-expression of matrix metalloproteinases in human fibroblasts by relaxation of mechanical tension. Matrix Biol. 2001;20(7):397–408. doi: 10.1016/s0945-053x(01)00156-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.George JN. Platelets. Lancet. 2000;355(9214):1531–1539. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)02175-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nurden AT, et al. Platelets and wound healing. Front Biosci. 2008;13:3532–3548. doi: 10.2741/2947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nakama LH, et al. VEGF, VEGFR-1, and CTGF cell densities in tendon are increased with cyclical loading: An in vivo tendinopathy model. J Orthop Res. 2006;24(3):393–400. doi: 10.1002/jor.20053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Scott A, et al. VEGF expression in patellar tendinopathy: a preliminary study. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2008;466(7):1598–1604. doi: 10.1007/s11999-008-0272-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang XT, Liu PY, Tang JB. Tendon healing in vitro: modification of tenocytes with exogenous vascular endothelial growth factor gene increases expression of transforming growth factor beta but minimally affects expression of collagen genes. J Hand Surg Am. 2005;30(2):222–229. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsa.2004.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hou Y, et al. Effects of transforming growth factor-beta1 and vascular endothelial growth factor 165 gene transfer on Achilles tendon healing. Matrix Biol. 2009;28(6):324–335. doi: 10.1016/j.matbio.2009.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sahin H, et al. Impaired biomechanical properties correlate with neoangiogenesis as well as VEGF and MMP-3 expression during rat patellar tendon healing. J Orthop Res. 2012;30(12):1952–1957. doi: 10.1002/jor.22147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chen J, et al. Sodium hyaluronate as a drug-release system for VEGF 165 improves graft revascularization in anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction in a rabbit model. Exp Ther Med. 2012;4(3):430–434. doi: 10.3892/etm.2012.629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kaux JF, et al. Eccentric training improves tendon biomechanical properties: a rat model. J Orthop Res. 2013;31(1):119–124. doi: 10.1002/jor.22202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]