Summary

Studies using in vitro cell models enable evaluation of the effects of different PRP products under very controlled and standardized conditions. Therefore the results of such studies build the basis for understanding the variable results of clinical studies on the use of PRPs. The main lessons learned through the use of in vitro cell models are that many different PRP products exist and researchers have to report on component variation within each product. These different products may have distinctive effects on the various cells treated in musculoskeletal injuries; therefore, some products might be more beneficial in certain indication than others. In its utilization in cell models, PRP may generate a variety of positive effects on cell proliferation, recovery, and inflammatory response. There might also be a benefit to adding PRP to current pharmacological therapies (e.g. corticosteroids) to prevent their commonly known negative effects on e.g. tendon and cartilage tissue.

Keywords: platelet-rich plasma, PRP, tendon, tenocytes, in vitro

Introduction

Platelet-rich concentrates, especially platelet-rich plasma (PRP), have shown promising results for the treatment of various musculoskeletal injuries1,2. Most of these results are based on either basic research or animal studies. However, recent clinical studies reporting on a higher level of evidence fail to show consistent positive results for the use of various PRPs.3

Since the first reports on the use of PRPs in medicine in the late 1980’s, specifically in cardiac surgery, a plethora of different production methods for PRPs have been published in the literature or presented by medical companies4. This results in numerous PRP products, which differ in terms of platelet number, white blood cell content, fibrin concentration, and method of platelet activation5. Finally, the only constant factor for all of these products could be seen in the definition by Marx6, who stated in 2001 that a platelet concentrate is called a PRP if the platelet concentration is above the baseline.

This variability forces us to get back to methods of standardized basic research testing to evaluate the basic properties and principles regarding the effects of PRP on the cells in the targeted tissue7. Therefore, this paper is intended to report on the lessons we have learned through translational research methods and focuses on the detection of the significant differences found in the distinctive PRP products and their effects on cells, tested in standardized in vitro environments. This is acknowledged as the best method to evaluate these differences without the variability of in vivo testing.

Variability of PRP products

PRP is produced by two basic methods following centrifugation of whole blood: separation of the buffy coat layer or isolation of the plasma layer. Buffy coat preparations are designed to retain the maximum number of platelets, and also include a higher concentration of leukocytes as well as some residual erythrocytes. High centrifuge spin rates for long durations are used to generate buffy coat preparations, whereas plasma-based products are prepared using a slower centrifugation rate over a shorter period of time. As a result, plasma-based PRPs contain fewer platelets, but are generally devoid of both white and red blood cells. Whether there is an advantage or detriment to leukocyte inclusion in PRP remains a matter of debate1,8.

The varying methods employed for PRP production may be a basis for the inconclusive results observed in clinical studies evaluating the efficacy of PRP treatment. Therefore, it is highly important for the clinician to be mindful of the different ways to obtain PRP, and how the differing approaches affect the composition of PRP at the time of treatment. To classify the numerous production methods, integrated systems are needed to better categorize PRP according to its principal contents (platelet concentration, leukocyte concentration, etc.). Several categorization methods have been proposed; however, to date, a standardized classification system has yet to be implemented in common practice. Dohan Ehrenfest et al.5 reported on a classification of platelet concentrates, which sorted the products according to their platelet, fibrin and leukocyte concentration: pure platelet-rich plasma (P-PRP), leukocyte- and platelet-rich plasma (L-PRP), pure platelet-rich fibrin (P-PRF), and leukocyte- and platelet-rich fibrin (L-PRF). These classifications were based on three sets of parameters: 1) the functional aspect of preparation, including the type of centrifuge used, duration of spin, and cost of preparation; 2) the final volume of PRP produced and degree of platelet and leukocyte retention and preservation following centrifugation; and 3) the fibrin density and organization following fibrinogen activation and clot formation. Only the second and third parameters were used for the classification of PRP and PRF. Therefore, this system sorts different preparations on the basis of leukocyte inclusion and fibrin clot presence with consideration of the facility and cost-effectiveness of individual systems.

De Long et al.9 presented the P.A.W. classification system, which was based on the method of platelet activation in addition to platelet concentration and presence or absence of white blood cells, and therefore represented a more detailed method. Platelet concentrations were grouped into four categories in relation to physiologic baseline, normally between 150,000–300,000 platelets/μl in whole blood, depending on the individual. A P1 classification corresponds to preparations with platelet levels below this baseline, and such preparations are generally termed platelet-poor plasma (PPP). P2 describes a moderate platelet concentration up to four times the physiologic concentration. Most plasma-based PRP products fall into the P2 category. P3 describes a high concentration between four and six times baseline platelet levels. Buffy coat systems typically generate platelet concentrations in the P3 range. Finally, P4 designates any concentration greater than six times physiologic platelet levels. Products in the P4 category may actually hinder the healing process due to growth factor overload, and as a whole are largely not recommended for therapeutic use (Choi et al.10). This system further distinguishes if platelets are activated prior to PRP administration, either exogenously using thrombin and calcium chloride or endogenously via Type I collagen present at the injection site. The presence of white blood cells is characterized as either being above (A) or below (B) baseline leukocyte counts. Generally, buffy coat preparations have an “A” designation for this category while plasma-based products are classified as “B”. Overall, this classification provides a useful categorization of the important components of PRP, which can help direct the clinician’s therapeutic approach.

Compounding the inconsistency between preparation methods are the inherent variations caused by physiological fluctuations in blood composition11. Naturally, blood from one patient may have a very different composition from another, but blood from an individual patient can also vary greatly between each draw. Therefore, the final PRP product is ultimately determined by the nature of the patient’s blood at the time of draw.

Our group12 reported a high degree of variability between subjects and within individual PRP samples prepared after three separate blood draws spaced two weeks apart. The study evaluated a plasma-based system: the Arthrex ACP Double Syringe (Arthrex Inc., Naples, FL, USA) and a buffy coat-based system: the Biomet GPS III Platelet Concentrate Separation Kit (Biomet Inc., Warsaw, IN, USA). Intra-individual platelet counts showed wide differences for each of the three preparations, indicating that variability persists even for PRP prepared using the same system on the same patient over time. The mean platelet count for the plasma-based system (378.3 ± 58.64 × 103 platelets/μl) was significantly lower than that of the buffy coat system (873.8 ± 207.82 × 103 platelets/μl). Leukocyte count was also significantly reduced in the plasma preparation (0.6 ± 0.3 × 103/μl) compared with buffy coat preparation (20.5 ± 6.7 × 103/μl), which was nearly four times above the mean whole blood white blood cell count (5.6 ± 1.7 × 103/μl).

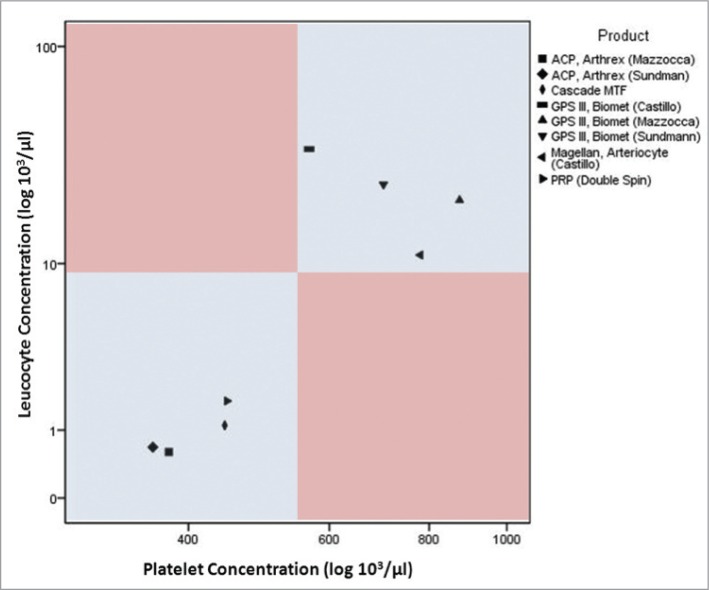

Sundman et al.13 also evaluated the Arthrex and Biomet systems and reported results similar to Mazzocca et al. for platelet (361 ± 87.0 × 103/μl) and leukocyte (0.68 ± 0.42 × 103/μl) counts for the Arthrex plasma-based system. Results from the Biomet buffy coat-derived system differed slightly: (701 ± 473 × 103 platelets/μl) and (23.7 ± 5.91 × 103 leukocytes/μl). These findings differed from those of Castillo et al.4, who also evaluated the Biomet GPS III along with other systems and reported somewhat contrasting results from the previously mentioned studies. The platelet count from the buffy coat-based system was fairly lower (566.2 ±292.6 × 103/μl) while the leukocyte count (34.4 ± 13.6 × 103/μl) was much higher than the two other reports. It is important to point out that all three studies mentioned here presented platelet counts with relatively high standard deviations, further alluding to the large variability between PRP preparations. Figure 1 illustrates differences between platelet and leukocyte content in plasma- and buffy coat-based systems.

Figure 1.

Different methods for PRP production shown according to their platelet und leukocyte concentration reported in recent studies. Please note that most “buffy coat” based procedures utilize a double spin centrifugation12,13.

Effects of different PRPs on musculoskeletal target cells

The use of PRP to augment the healing of musculoskeletal injuries is only beneficial if the contents have advantageous effects on the tissue-specific cells of the injured site. Therefore, it is important to know the specific effects of the various contents of PRP on these target cells. PRP contains high concentrations of growth factors including platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF), transforming growth factor beta (TGF-β), vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF), hepatocyte growth factor (HGF), and epidermal growth factor (EGF) that provide the potential to modulate the healing of bone, muscle, and tendon through interactions with specific cells in these respective structures14 (Fig. 2). An overview of the effect of these growth factors and secretory proteins on musculoskeletal target cells specifically related to bone, muscle, and tendon will be covered in this section.

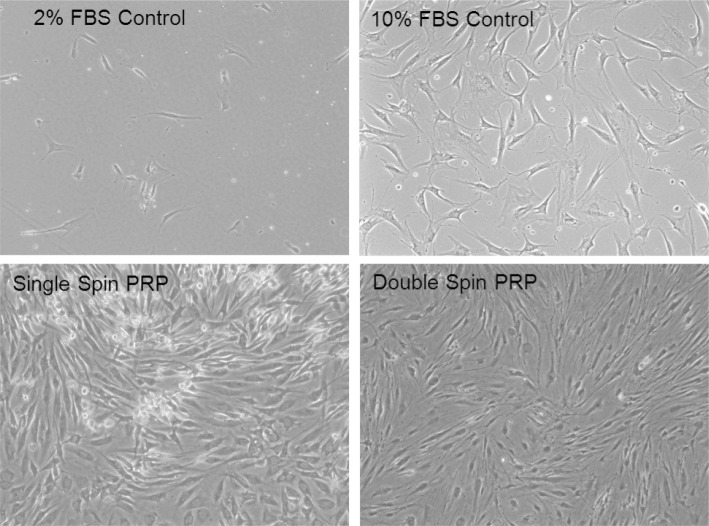

Figure 2.

Examples of human tendon like cells grown in standard culture medium were treated at the same time with different PRP products (single spin PRP with platelet concentration of 324 ± 28.7 × 103/μL and double spin PRP with platelet concentration of 555 ± 67.3 × 103/μL) vs fetal bovine serum (FBS) controls. Cells treated with 2% FBSare viable but in a non-proliferative state compared to cells treated with normal control medium (10% FBS) which promotes proliferation. Cells treated with 2% FBS and Single and Double Spin PRP preparations show a significant increase in proliferation compared to cells treated with 2 and 10% FBS alone. Cells treated with Single Spin PRP reached a state of confluence more rapidly than the other treatment groups. (Mag = 10×).

The process of bone regeneration involves a series of events dependent on resident bone cells and the extracellular environment that includes mesenchymal stromal cells (MSCs), growth factors, and vascular structures15,16. PRP contains pro-osteogenic factors including PDGF, TGF-β, EGF, VEGF, and bFGF that may play a critical role in the process of bone regeneration15,17. These factors make PRP a potential therapeutic agent to be used either alone or in combination with MSCs to regenerate bone15,18–21. For muscular injuries, specific growth factors involved in repair are not completely understood at the present time; however the effects of growth factors present in PRP are believed to have the potential to improve healing and clinical outcomes14. The underlying basis of this proposed benefit is that a muscle contusion, strain, or laceration undergoes a repair process that includes three overlapping phases – inflammation, regeneration, and repair, followed by fibrosis and remodeling14,22–24. The transition between phases of this repair process is controlled by PDGF, bFGF, TGF-β, and HGF14,25,26. Based on the presence of these growth factors and the key roles they play in the muscular repair process, the therapeutic goal of PRP for muscular injury is to shorten the sequence of the healing cascade14. Similar to its effects on muscle healing, the intrinsic properties of PRP also regulate the phases of tendon healing. The effects that growth factors have on tendon healing are still under investigation; however, it is possible that the intrinsic characteristics of PRP may augment the healing process13,14.

Our group evaluated the effects of three different PRP products on the proliferation of osteoblasts, myoblasts, and tenocytes. Comparing a single-spin process yielding low platelet and white blood cell concentration, a single-spin process yielding high platelet and white blood cell concentrations, and a double-spin process that produces a high platelet concentration and low white blood cell concentration, the authors observed increases in proliferation for each target cell (bone, muscle, and tendon) across all methods of procurement27. Based on the results, we were able to conclude that the application of various PRP separations may result in a potentially beneficial therapeutic effect on clinically relevant target cells27. Although the study reported on the potentially beneficial effects of PRP on target cells, we acknowledged that it remains unclear as to which platelet concentration or PRP preparation is considered the optimal treatment of various cell types and that a “more is better” theory for the use of higher platelet concentrations could not be supported27.

Anitua et al.28 evaluated the effects of scaffolds prepared from preparations rich in growth factors (PRGF) with increasing amounts of platelets (low number of leukocytes) on fibroblast cell cultures harvested from three different anatomical sites (skin, synovium and tendon). They observed an increase in cell proliferation for all PRGF types and preparations (even including the supernatans of platelet poor plasma) compared to the controls. However, adding scaffolds containing a platelet concentration of 2–4x above baseline resulted in the highest proliferation rate. In addition, fibroblasts harvested from different origins demonstrated variable angiogenic responses with regards to their anatomical origin.

Proliferation assays are used for most in vitro cell models, since this assay is directly linked to DNA production within cells and closely correlated with cell division, therefore demonstrating proliferative activity. Proliferation of tenocyte-like cells was affected positively by the addition of PRP products in a number of in vitro studies evaluating tendon-like cells29–32. However the in vitro models fail to conclusively show if this increased proliferation has positive or negative effects.

The type I to type III collagen ratio is seen as an important aspect for successful regeneration of functional tendon tissue. A recent review performed by Baksh et al.33 identified nine studies overall showing an increase in this collagen ratio and two explicit studies, which reported an improved collagen I/III ratio compared to the controls.

More recently, Perut et al.15 investigated the efficacy of different components of platelet concentrates on the osteogenic differentiation of bone marrow stromal cells (BMSCs). Comparing two different procurement techniques, the authors reported that, in addition to the differences in platelet recovery between systems, the composition of PRP was associated with variance in the progressive release of bFGF from the platelet gel, which is significantly associated with the proliferation of BMSCs and their ability to mineralize15. Based on the results of their work, the authors concluded that the ability of different platelet gels to induce proliferation and osteogenic differentiation of BMSCs is related to the composition of PRP including the platelet, leukocyte, and growth factor concentrations and availability15. The investigators suggest that, based on the data presented in their study, composition and bioactivity of PRP should be analyzed so that the clinician has a more complete understanding of the potential effectiveness of the regenerative treatment15.

Anti-inflammatory effects of PRP

Chronic or acute inflammation of the joint, whether it be through injury or disease such as osteoarthritis (OA), can be debilitating. A wide spectrum of treatments are available, from non-pharmacological modalities to dietary supplements and pharmacological therapies, as well as minimally invasive procedures involving injections of various substances aimed at restoring joint homeostasis and providing clinical improvement and possible disease modifying effects34–45. These injections are sometimes painful and are oftentimes combined with local anesthetics to alleviate the discomfort of the injection.

As an autologous blood product, PRP provides a promising alternative to steroid injections by promoting safe and natural healing. PRP is a rich source of growth factors, but it also contains antibacterial and fungicidal proteins, metalloproteinases (MMPs), coagulation factors, and membrane glycoproteins that influence inflammation by inducing the synthesis of other integrins, interleukins, chemokines, and cytokines46. Muscles, tendons, and ligaments heal by going through three phases of wound healing - inflammation, proliferation and remodeling; various cytokines are active during each of these phases of wound healing2,47–49. The cytokines and other bioactive factors released from PRP are known to affect these basic metabolic processes in the soft tissues of the musculoskeletal system2,47–49.

Although there have been many clinical studies on the anti-inflammatory effects of corticosteroids injections, clinical studies using PRP are limited39,50–54. Studies such as these require time, resources, and a large patient pool to draw from, making in vitro studies very attractive to answer basic science questions. In vitro studies assessing PRP’s anti-inflammatory effects, however, are difficult because clinical benefits may not be directly correlated to in vitro results. Because of the wide variation of injection and PRP preparation methods used in clinical settings, it is difficult to determine the exact levels of growth factors found in or around cartilage and tendon tissue in the human body55. Although there have been in vitro studies assessing the anti-inflammatory effects of PRP, few have directly addressed PRP’s effects on chondrocytes or tenocytes. A recent review article by Filardo et al. reported 17 in vitro studies in which the role of PRP on chondrocytes were investigated, of which only 4 papers focused on PRP in OA chondrocytes for modulation of inflammation35,56–59. One reason for the lack of studies may the difficulty in recreating a state of inflammation in either chondrocyte or tenocyte cultures.

One of the most recent and interesting in vitro studies conducted by Sundman et al. assessed the anti-inflammatory effects of PRP and high molecular weight hyaluronan (HA) in an ex vivo co-culture model for OA using human cartilage and synovium60. Their results showed that tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α), a mediator of acute inflammation and an activator of MMPs, was decreased in the media of the PRP and HA groups compared to the control group61–63. MMP-13 gene expression in synoviocytes was significantly decreased in the PRP group but not the HA group, while hyaluronan synthase 2 (HAS-2) expression in the synovium was increased by the addition of PRP compared to the HA and control groups. Further, cartilage matrix gene expression of aggrecan and type I collagen in the collagen explants treated with PRP was significantly higher than in the HA groups but not from the control untreated group. Combined, these results suggest that PRP can act to stimulate endogenous HA production while decreasing cartilage catabolism. They concluded that PRP can act to suppress inflammatory mediator concentration and gene expression in synovium and cartilage tissue.

An in vitro study by El-Sharkawy et al. used monocyte culture to assess cytokine and chemokine levels, as well as monocyte chemotactic migration, in the presence and absence of PRP64. Their results showed that monocyte chemotactic protein-1 (MCP-1), which is released by monocytes in response to pro-inflammatory stimuli, was significantly decreased by PRP in monocyte culture compared to untreated cells. However, chemokine ligand 5 (CCL5), also known as RANTES (regulated on activation, normal T cell expressed and secreted), was significantly increased compared to control untreated cells and led to a dose-dependent increase in monocytechemotaxis. In addition, levels of lipoxin A4 (LXA4), an anti-inflammatory lipid, were significantly higher in PRP compared to those in whole blood. This study suggests that PRP can act as an anti-inflammatory agent by producing endogenous anti-inflammatory factors and by affecting monocyte cytokine release.

Our lab recently completed an in vitro study in which we assessed the anti-inflammatory effects of PRP, either alone or in combination with the corticosteroid methylprednisolone or the NSAID ketorolac tromethamine, on stimulated human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs)55. The cells were first stimulated with inflammatory cytokines: TNFα and interferonγ (INFγ), after which cell adhesion molecule expression for E-selectin, vascular cell adhesion molecule (VCAM), and human leukocyte antigen DR (HLA-DR) were measured. The results showed a decreased expression of cell adhesion molecules in stimulated cells after treatment with PRP, ketorolac, and methylprednisolone, with methylprednisolone having the greatest anti-inflammatory effect. Additionally, there were no significant differences seen between PRP and ketorolac, suggesting that PRP and ketorolac have a similar inhibitory effect on the inflammatory process in stimulated HUVECs. Although a decrease in inflammation was observed in this paper, the in vitro behavior of HUVECs may not mimic the in vivo environment surrounding the joint, making this one of the limitations of this paper. However, this is a commonly used model for general inflammation. We concluded that both PRP and ketorolac reduced cellular inflammation compared to control, but neither caused as great a reduction as methylprednisolone.

As stated earlier, the composition of different PRP products differs significantly in terms of leukocyte content. This might also affect the PRPs’ anti-inflammatory effects. Mc Carrell et al. (JBJS, 2012) demonstrated, using tendon-like cells harvested and cultured from horse flexor digitorum superficialis tendons, that an increase in leukocyte content of PRP products is positively correlated with an increased expression of inflammatory cytokines and that the platelet/leukocyte ratio had no influence on this effect.

Discussion

Studies using in vitro cell models enable evaluation of the effects of different PRP products under very controlled and standardized conditions. Therefore the results of such studies build the basis for understanding the variable results of clinical studies on the use of PRPs. However, all of the results of such in vitro models have to be evaluated with caution, since the final clinical effects are not proven1–3,33.

We have learned from these controlled laboratory studies that PRP products can vary greatly, even in such basic aspects as their platelet concentration or the content of white blood cells12,13. Recent classification methods have been established to allow the clinician to exactly report on the nature of the specific PRP product used in their study. Out of these, De Long′s classification allows for a very detailed distinction of the various PRP production methods, whereas the classification presented by Dohan Ehrenfest describes fibrin contents in more detail5,9. Besides these overall classifications, studies have shown a high intra-individual variability of PRP products, even if these have been isolated from an identical subject12. Therefore the optimal methodology for clinical studies would be at least to report on the individual platelet- and white blood cell concentration of each treatment used in clinical studies11–13. This would allow for better comparison between studies and more accurate overall conclusions on the effects of the different PRP products.

Multiple studies utilized tendon-like cell models33. Most of the reported studies showed increased cell proliferation with the addition of various PRP products. This suggests that PRP products have a positive effect on the cells’ mitogenic activity. Also, improvement in collagen production and optimization of the important collagen I/III ratio have been observed29,31,33. However, these positive effects and their consequences for “real life” tissue healing have yet to be identified in clinical studies3. It has also been shown, that different cell types (e.g. tendon-like cells vs. osteoblasts) show varying results if different PRP products are applied to the cell culture28,29. This raises the question if the variation of PRP components may allow for a targeted use of the specific product (e.g. high concentration of platelets vs low concentration) for a specific cell type. This means, for example, tendon cells may benefit from one type of PRP product for the treatment of tendinitis whereas chondrocytes and synovial cells may benefit from a different PRP product for the treatment of cartilage lesions or joint inflammation. Knowledge about these specific functions is only just emerging and many additional studies are needed to finally understand these potential relationships.

All in vitro studies have multiple limitations and conclusions drawn from these studies can only be transferred into the clinical setting with much caution. Most of the cited studies utilized different donors for the cell culture and the PRP products. In general, PRPs are intended to be an autologous treatment. Therefore, unknown immunological effects cannot be totally ruled out in such in vitro experiments. This might be of special importance for the studies evaluating PRP products with a high concentration of white blood cells. As stated earlier, only specific functions of the cells, such as cell proliferation and production of matrix proteins (e.g. collagen), are assayed in such in vitro models, which limits the conclusions about these factors and does not allow for a clinical prognosis. On the other hand, in vitro cell models allow for a very standardized and controlled set up, which enables strict evaluation of a specific question without significant variability due to the environment.

Overall, these in vitro studies give a broad basis for future clinical studies, which should take the presented findings into account and adapt the methodology according to the lessons we have learned from in vitro studies.

Conclusion

In summary, the main lessons learned through the use of in vitro cell models are that many different PRP products exist and researchers have to report on component variation within each product. These different products may have distinctive effects on the various cells treated in musculoskeletal injuries. Therefore, some products might be more beneficial in certain indication than others. In its utilization in vitro models, PRP may generate a variety of positive effects on cell proliferation, recovery, and inflammatory response. There might also be a benefit to adding PRP to current pharmacological therapies (Corticoids or NSAIDs) to prevent their commonly known negative effects on tendon and cartilage tissue.

The University of Connecticut Health Center / New England Musculoskeletal Institute has received direct funding and material support for this study from Arthrex Inc. (Naples, Fl). The company had no influence on study design, data collection, and interpretation of the results or the writing of the final manuscript.

References

- 1.Lopez-Vidriero E, Goulding KA, Simon DA, Sanchez M, Johnson DH. The use of platelet-rich plasma in arthroscopy and sports medicine: optimizing the healing environment. Arthroscopy. 2010;26:269–278. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2009.11.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Foster TE, Puskas BL, Mandelbaum BR, Gerhardt MB, Rodeo SA. Platelet-rich plasma: from basic science to clinical applications. Am J Sports Med. 2009;37:2259–2272. doi: 10.1177/0363546509349921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hsu WK, Mishra A, Rodeo SR, et al. Platelet-rich plasma in orthopaedic applications: evidence-based recommendations for treatment. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2013;21:739–748. doi: 10.5435/JAAOS-21-12-739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ferrari M, Zia S, Valbonesi M, et al. A new technique for hemodilution, preparation of autologous platelet-rich plasma and intraoperative blood salvage in cardiac surgery. Int J Artif Organs. 1987;10:47–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dohan Ehrenfest DM, Rasmusson L, Albrektsson T. Classification of platelet concentrates: from pure platelet-rich plasma (P-PRP) to leucocyte- and platelet-rich fibrin (L-PRF) 2009;27:158–167. doi: 10.1016/j.tibtech.2008.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Marx RE. Platelet-rich plasma (PRP): what is PRP and what is not PRP? 2001;10:225–228. doi: 10.1097/00008505-200110000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Padulo J, Oliva F, Frizziero A, Maffulli N. Muscle, Ligaments and Tendons Journal. Basic principles and recommendations in clinical and field science research. MLTJ. 2013;4:250–252. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Moojen DJ, Everts PA, Schure RM, et al. Antimicrobial activity of platelet-leukocyte gel against Staphylococcus aureus. 2008;26:404–410. doi: 10.1002/jor.20519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.DeLong JM, Russell RP, Mazzocca AD. Platelet-rich plasma: the PAW classification system. Arthroscopy. 2012;28:998–1009. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2012.04.148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Choi BH, Zhu SJ, Kim BY, Huh JY, Lee SH, Jung JH. Effect of platelet-rich plasma (PRP) concentration on the viability and proliferation of alveolar bone cells: an in vitro study. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2005;34:420–424. doi: 10.1016/j.ijom.2004.10.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Russell RP, Apostolakos J, Hirose T, Cote MP, Mazzocca AD. Variability of platelet-rich plasma preparations. Sports Med Arthrosc. 2013;21:186–190. doi: 10.1097/JSA.0000000000000007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mazzocca AD, McCarthy MB, Chowaniec DM, et al. Platelet-rich plasma differs according to preparation method and human variability. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2012;94:308–316. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.K.00430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sundman EA, Cole BJ, Fortier LA. Growth factor and catabolic cytokine concentrations are influenced by the cellular composition of platelet-rich plasma. Am J Sports Med. 2011;39:2135–2140. doi: 10.1177/0363546511417792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mejia HA, Bradley JP. The Effects of Platelet-Rich Plasma on Muscle. Basic Science and Clinical Application. 2011;19:149–153. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Perut F, Filardo G, Mariani E, et al. Preparation method and growth factor content of platelet concentrate influence the osteogenic differentiation of bone marrow stromal cells. Cytotherapy. 2013;15:830–839. doi: 10.1016/j.jcyt.2013.01.220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Arvidson K, Abdallah BM, Applegate LA, et al. Bone regeneration and stem cells. Journal of cellular and molecular medicine. 2011;15:718–746. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2010.01224.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Castillo TN, Pouliot MA, Kim HJ, Dragoo JL. Comparison of Growth Factor and Platelet Concentration From Commercial Platelet-Rich Plasma Separation Systems. Am J Sports Med. 2011;39:266–271. doi: 10.1177/0363546510387517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Intini G. The use of platelet-rich plasma in bone reconstruction therapy. Biomaterials. 2009;30:4956–4966. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2009.05.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cenni E, Perut F, Ciapetti G, et al. In vitro evaluation of freeze-dried bone allografts combined with platelet rich plasma and human bone marrow stromal cells for tissue engineering. Journal of materials science Materials in medicine. 2009;20:45–50. doi: 10.1007/s10856-008-3544-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Janicki P, Schmidmaier G. What should be the characteristics of the ideal bone graft substitute? Combining scaffolds with growth factors and/or stem cells. Injury. 2011;42(Suppl 2):S77–81. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2011.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cenni E, Savarino L, Perut F, Fotia C, Avnet S, Sabbioni G. Background and rationale of platelet gel in orthopaedic surgery. Musculoskeletal surgery. 2010;94:1–8. doi: 10.1007/s12306-009-0048-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jarvinen TA, Kaariainen M, Jarvinen M, Kalimo H. Muscle strain injuries. Current opinion in rheumatology. 2000;12:155–161. doi: 10.1097/00002281-200003000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Huard J, Li Y, Fu FH. Muscle injuries and repair: current trends in research. The Journal of bone and joint surgery American volume. 2002;84-A:822–832. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Crisco JJ, Jokl P, Heinen GT, Connell MD, Panjabi MM. A muscle contusion injury model. Biomechanics, physiology, and histology. The American journal of sports medicine. 1994;22:702–710. doi: 10.1177/036354659402200521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mishra DK, Friden J, Schmitz MC, Lieber RL. Anti-inflammatory medication after muscle injury. A treatment resulting in short-term improvement but subsequent loss of muscle function. The Journal of bone and joint surgery American volume. 1995;77:1510–1519. doi: 10.2106/00004623-199510000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Burkin DJ, Kaufman SJ. The alpha7beta1 integrin in muscle development and disease. Cell and tissue research. 1999;296:183–190. doi: 10.1007/s004410051279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mazzocca AD, McCarthy MB, Chowaniec DM, et al. The positive effects of different platelet-rich plasma methods on human muscle, bone, and tendon cells. The American journal of sports medicine. 2012;40:1742–1749. doi: 10.1177/0363546512452713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Anitua E, Sanchez M, Zalduendo MM, et al. Fibroblastic response to treatment with different preparations rich in growth factors. Cell Prolif. 2009;42:162–170. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2184.2009.00583.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mazzocca AD, McCarthy MB, Chowaniec DM, et al. The positive effects of different platelet-rich plasma methods on human muscle, bone, and tendon cells. Am J Sports Med. 2012;40:1742–1749. doi: 10.1177/0363546512452713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Carofino B, Chowaniec DM, McCarthy MB, et al. Corticosteroids and local anesthetics decrease positive effects of platelet-rich plasma: An in vitro study on human tendon cells. Arthroscopy. 2012 doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2011.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.de Mos M, van der Windt AE, Jahr H, et al. Can platelet-rich plasma enhance tendon repair? A cell culture study. Am J Sports Med. 2008;36:1171–1178. doi: 10.1177/0363546508314430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tohidnezhad M, Varoga D, Wruck CJ, et al. Platelet-released growth factors can accelerate tenocyte proliferation and activate the anti-oxidant response element. Histochem Cell Biol. 2011;135:453–460. doi: 10.1007/s00418-011-0808-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Baksh N, Hannon CP, Murawski CD, Smyth NA, Kennedy JG. Platelet-rich plasma in tendon models: a systematic review of basic science literature. Arthroscopy. 2013;29:596–607. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2012.10.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Moraes VY, Lenza M, Tamaoki MJ, Faloppa F, Belloti JC. Platelet-rich therapies for musculoskeletal soft tissue injuries. The Cochrane database of systematic reviews. 2013;12:CD010071. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD010071.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Filardo G, Kon E, Roffi A, Di Matteo B, Merli ML, Marcacci M. Platelet-rich plasma: why intra-articular? A systematic review of preclinical studies and clinical evidence on PRP for joint degeneration. Knee surgery, sports traumatology, arthroscopy: official journal of the ESSKA. 2013 doi: 10.1007/s00167-013-2743-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Reid MC. Viscosupplementation for osteoarthritis: a primer for primary care physicians. Advances in therapy. 2013;30:967–986. doi: 10.1007/s12325-013-0068-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sampson S, Botto-van Bemden A, Aufiero D. Autologous bone marrow concentrate: review and application of a novel intra-articular orthobiologic for cartilage disease. The Physician and sports medicine. 2013;41:7–18. doi: 10.3810/psm.2013.09.2022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhu Y, Yuan M, Meng HY, et al. Basic science and clinical application of platelet-rich plasma for cartilage defects and osteoarthritis: a review. Osteoarthritis and cartilage/OARS, Osteoarthritis Research Society. 2013;21:1627–1637. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2013.07.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.van Middelkoop M, Dziedzic KS, Doherty M, et al. Individual patient data meta-analysis of trials investigating the effectiveness of intra-articular glucocorticoid injections in patients with knee or hip osteoarthritis: an OA Trial Bank protocol for a systematic review. Systematic reviews. 2013;2:54. doi: 10.1186/2046-4053-2-54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bannuru RR, Vaysbrot EE, Sullivan MC, McAlindon TE. Relative efficacy of hyaluronic acid in comparison with NSAIDs for knee osteoarthritis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Seminars in arthritis and rheumatism. 2013 doi: 10.1016/j.semarthrit.2013.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Klinge SA, Sawyer GA. Effectiveness and safety of topical versus oral nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs: a comprehensive review. The Physician and sports medicine. 2013;41:64–74. doi: 10.3810/psm.2013.05.2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.McKeon BP, Rand JD. Treatment of osteoarthritis of the middle-aged athlete. Sports medicine and arthroscopy review. 2013;21:52–60. doi: 10.1097/JSA.0b013e31827ddd5e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Grazio S, Balen D. Complementary and alternative treatment of musculoskeletal pain. Acta clinica Croatica. 2011;50:513–530. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Herbal medicines for osteoarthritis Drug and therapeutics bulletin. 2012;50:8–12. doi: 10.1136/dtb.2011.02.0081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ernst E, Posadzki P. Complementary and alternative medicine for rheumatoid arthritis and osteoarthritis: an overview of systematic reviews. Current pain and headache reports. 2011;15:431–437. doi: 10.1007/s11916-011-0227-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cole BJ, Seroyer ST, Filardo G, Bajaj S, Fortier LA. Platelet-rich plasma: where are we now and where are we going? Sports health. 2010;2:203–210. doi: 10.1177/1941738110366385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Abrams GD, Frank RM, Fortier LA, Cole BJ. Platelet-rich plasma for articular cartilage repair. Sports medicine and arthroscopy review. 2013;21:213–219. doi: 10.1097/JSA.0b013e3182999740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Nguyen RT, Borg-Stein J, McInnis K. Applications of platelet-rich plasma in musculoskeletal and sports medicine: an evidence-based approach. PM & R : the journal of injury, function, and rehabilitation. 2011;3:226–250. doi: 10.1016/j.pmrj.2010.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Redler LH, Thompson SA, Hsu SH, Ahmad CS, Levine WN. Platelet-rich plasma therapy: a systematic literature review and evidence for clinical use. The Physician and sports medicine. 2011;39:42–51. doi: 10.3810/psm.2011.02.1861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Habib G, Artul S, Chernin M, Hakim G, Jabbour A. The effect of intra-articular injection of betamethasone acetate/betamethasone sodium phosphate at the knee joint on the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis: a case-controlled study. Journal of investigative medicine : the official publication of the American Federation for Clinical Research. 2013;61:1104–1107. doi: 10.2310/JIM.0b013e3182a67871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Habib G, Jabbour A, Artul S, Hakim G. Intra-articular methylprednisolone acetate injection at the knee joint and the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis: a randomized controlled study. Clinical rheumatology. 2013 doi: 10.1007/s10067-013-2374-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Marsland D, Mumith A, Barlow IW. Systematic review: The safety of intra-articular corticosteroid injection prior to total knee arthroplasty. The Knee. 2013 doi: 10.1016/j.knee.2013.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Mardani-Kivi M, Karimi-Mobarakeh M, Karimi A, et al. The effects of corticosteroid injection versus local anesthetic injection in the treatment of lateral epicondylitis: a randomized single-blinded clinical trial. Archives of orthopaedic and trauma surgery. 2013;133:757–763. doi: 10.1007/s00402-013-1721-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Chia SK, Wernecke GC, Harris IA, Bohm MT, Chen DB, Macdessi SJ. Peri-articular steroid injection in total knee arthroplasty: a prospective, double blinded, randomized controlled trial. The Journal of arthroplasty. 2013;28:620–623. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2012.07.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Mazzocca AD, McCarthy MB, Intravia J, et al. An in vitro evaluation of the anti-inflammatory effects of platelet-rich plasma, ketorolac, and methylprednisolone. Arthroscopy : the journal of arthroscopic & related surgery: official publication of the Arthroscopy Association of North America and the International Arthroscopy Association. 2013;29:675–683. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2012.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wu CC, Chen WH, Zao B, et al. Regenerative potentials of platelet-rich plasma enhanced by collagen in retrieving pro-inflammatory cytokine-inhibited chondrogenesis. Biomaterials. 2011;32:5847–5854. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2011.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.van Buul GM, Koevoet WL, Kops N, et al. Platelet-rich plasma releasate inhibits inflammatory processes in osteoarthritic chondrocytes. The American journal of sports medicine. 2011;39:2362–2370. doi: 10.1177/0363546511419278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Pereira RC, Scaranari M, Benelli R, et al. Dual effect of platelet lysate on human articular cartilage: a maintenance of chondrogenic potential and a transient proinflammatory activity followed by an inflammation resolution. Tissue engineering Part A. 2013;19:1476–1488. doi: 10.1089/ten.TEA.2012.0225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Bendinelli P, Matteucci E, Dogliotti G, et al. Molecular basis of anti-inflammatory action of platelet-rich plasma on human chondrocytes: mechanisms of NF-kappaB inhibition via HGF. Journal of cellular physiology. 2010;225:757–766. doi: 10.1002/jcp.22274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Sundman EA, Cole BJ, Karas V, et al. The Anti-inflammatory and Matrix Restorative Mechanisms of Platelet-Rich Plasma in Osteoarthritis. The American journal of sports medicine. 2013 doi: 10.1177/0363546513507766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kapoor M, Martel-Pelletier J, Lajeunesse D, Pelletier JP, Fahmi H. Role of proinflammatory cytokines in the pathophysiology of osteoarthritis. Nature reviews Rheumatology. 2011;7:33–42. doi: 10.1038/nrrheum.2010.196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Tetlow LC, Adlam DJ, Woolley DE. Matrix metalloproteinase and proinflammatory cytokine production by chondrocytes of human osteoarthritic cartilage: associations with degenerative changes. Arthritis and rheumatism. 2001;44:585–594. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(200103)44:3<585::AID-ANR107>3.0.CO;2-C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Wells MR, Racis SP, Jr, Vaidya U. Changes in plasma cytokines associated with peripheral nerve injury. Journal of neuroimmunology. 1992;39:261–268. doi: 10.1016/0165-5728(92)90260-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.El-Sharkawy H, Kantarci A, Deady J, et al. Platelet-rich plasma: growth factors and pro- and anti-inflammatory properties. Journal of periodontology. 2007;78:661–669. doi: 10.1902/jop.2007.060302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]