Abstract

The management of facial defects has rapidly changed in the last decade. Functional and esthetic requirements have steadily increased along with the refinements of surgery. In the case of advanced atrophy or jaw defects, extensive horizontal and vertical bone augmentation is often unavoidable to enable patients to be fitted with implants. Loss of vertical alveolar bone height is the most common cause for a non primary stability of dental implants in adults. At present, there is no ideal therapeutic approach to cure loss of vertical alveolar bone height and achieve optimal pre-implantological bone regeneration before dental implant placement. Recently, it has been found that specific populations of stem cells and/or progenitor cells could be isolated from different dental resources, namely the dental follicle, the dental pulp and the periodontal ligament. Our research group has cultured palatal-derived stem cells (paldSCs) as dentospheres and further differentiated into various cells of the neuronal and osteogenic lineage, thereby demonstrating their stem cell state. In this publication will be shown whether paldSCs could be differentiated into the osteogenic lineage and, if so, whether these cells are able to regenerate alveolar bone tissue in vivo in an athymic rat model. Furthermore, using these data we have started a proof of principle clinical- and histological controlled study using stem cell-rich palatal tissues for improving the vertical alveolar bone augmentation in critical size defects. The initial results of the study demonstrate the feasibility of using stem cell-mediated tissue engineering to treat alveolar bone defects in humans.

Keywords: Human palatal-derived stem cells (paldSCs), Osteogenic differentiation, Athymic immunodeficient rats, Stem-cell enriched palatal-derived tissues, Proof of principle clinical-and histologically-con, Osteoplastic surgical methods

Introduction

The management of facial defects has rapidly changed in the last decade. Functional and esthetic requirements have steadily increased along with the refinements of surgery. Facial defects include nearly all aspects of the face, i.e. the facial soft tissues, skull, and teeth. Disfigurement and extension of a defect go inparallel; seen in clefts, Noma, which is a devastating gangreneous disease that leads to severe tissue destruction of the face and long-lasting defects after trauma and tumour surgery.

The fact that speaking, mastication, deglutition, and effortless respiration are localized in the face, dictates the goal for any treatment: the most lifelike restoration possible to restore physiological function. To date the most frequently used technique for reconstruction of extended defects is the transfer of vascularized osseous respectively osseo(-myo-)cutaneous free flaps in particular as part of oncologic surgery of the head and neck region. Fibula, scapula, and iliac crest were the preferred donor sites (Vinzenz and C. Schaudy, 2011).

In the case of advanced atrophy or jaw defects, extensive horizontal and vertical bone augmentation is often unavoidable to enable patients to be fitted with implants. These implantological procedures are usually two-stage. Bone block transplantation is a good model to evaluate bone regeneration. It is common to combine autologous bone blocks with alloplastic material. Drawback of the procedure is that, to obtain autologous bone, an additional surgical step is needed, causing donor-site morbidity (Grimm et al. 2012, 2013). If alloplastic materials are used without addition, normally longer healing times are chosen to compensate for the initial lack of regeneration. This explains why there are minor reports about healing periods of less than 6 months when pure allogenic material is used. The report of our research group (Plöger and Schau, 2010) has showed in the first time the healing periods of more than three years when pure allogenic material is used.

The regeneration of bone requires an adequate scaffold as well as cells that are capable to attach to the scaffold, proliferate, and differentiate. The dynamics of bone healing are controlled by growth factors, such as bone morphogenetic proteins. To promote these requirements, several strategies for bone and tissue regeneration have been developed.

The discovery of stem cells and recent advances in cellular and molecular biology has led to the development of novel therapeutic strategies that aim at the regeneration of many tissues that were injured by disease. Tissue engineering is a multidisciplinary field that combines biology, engineering, and clinical science with the goal of generating new tissues and organs. It is a science based on fundamental principles that involves the identification of appropriate cells, the development of scaffolds and morphogenic signals required to induce cells to regenerate a tissue or organ.

Neural crest cells could be termed a dormant stem cell population in the adult, as they are pluripotent at first, but with migration they become restricted during development (Cheng et al. 2012). Neural crest cells that form the vertebrate head skeleton migrate and interact with surrounding tissues to shape the skull. In common with most organs, teeth develop from interactions between epithelial cells (oral epithelium) and mesenchymal cells (cranial neural-crest-derived ectomesenchyme).

From a biological perspective, current and future prospects for improved regeneration of bone in the facial skull and upper and lower jaw are dependent on the ability to facilitate the repopulation of the wound by cells capable of promoting regeneration.

Several recent studies showed that neural crest-related stem cells can be isolated from mammalian craniofacial tissues such as periodontal ligament, dental pulp, and palate. These cells have in common that they form neurosphere-like clusters and proliferate in serum-free culture in the presence of fibroblast growth factor-2 (FGF-2) and epidermal growth factor (EGF).

From this perspective, the human palate has been shown to be of critical importance in the regenerative process. Although it is clear that cells residing in the subepithelial soft tissue of the palate can achieve bone regeneration, this population is heterogenous (Harris, 1999), but it is not known which subpopulations are capable of achieving regeneration. Indeed, cells derived from palate were found to have specific properties, such as increased proliferation rates, and representative of a regenerative phenotype as shown by research group (Greiner et al. 2011, Widera et al. 2009).

In order to understand the cellular origins of Neural Crest Stem Cells from Dental and Periodontal Tissues, transplanted tooth buds were used to show that the mesenchymal-derived dental follicle surrounding the developing tooth root is the source of progenitor cells for cementum, alveolar bone and periodontal ligament (Heinemann and Götz 2013). Further evidence, that cells from the dental follicle are precursors to cementoblasts and to osteoblasts, has been shown by direct cell migration in the rat molars. More recently, the dental follicle associated with third molars has been shown to contain precursor cells which are clonogenic and have the ability to differentiate under in vitro conditions to a membrane-like structure containing calcified nodules (Morsczeck et al. 2009).

The source of post-natal progenitor cells which may be capable of regenerating the alveolar bone has been investigated for a number of years. Cell kinetic experiments in mice and rats have shown that osteoblast populations of the subepithelial palatal soft tissue represent a steady-state renewal system, with the number of new cells generated by mitosis equal to the number of cells lost through apoptosis and migration. This capacity for self-renewal, which is further evidenced by the rapid turnover of these stem cells, supports the notion of progenitor/stem cell populations. Furthermore, a significant number of palatal-derived stem cells do not enter the cell cycle, suggesting that these cells may act in a similar manner to quiescent, self-renewable and multipotent stem cells.

The relationship between progenitor cells in regenerating tissues and normally functioning (steady-state) tissues has been investigated in studies performed in normal mouse alveolar bone, wounded mouse alveolar bone defects, normal rat gingiva and inflamed monkey gingiva (see overview by Mao et al.). These studies have identified a common paravascular location for osteo- and fibroblast progenitors. These cells exhibit some of the classical cytological features of stem cells, including small size, responsiveness to stimulating factors, and slow cycle time (Schomann et al. 2013). Furthermore, these paravascular cells exhibit spatial clustering which suggests a possible clonal distribution of progenitors and their progeny (Vertelov et al. 2013).

Other possible sources of osteoblast and cementoblast precursors are the endosteal spaces of alveolar bone from which cells have been observed to adopt a paravascular location in the bone of mice (Marx and Tursun 2011).

Through a combination of transplanted biomaterials containing appropriately selected and primed stem cells, together with an appropriate mix of regulatory factors and extracellular matrix components to allow growth and specialization of the cells, the research of new therapies with significant clinical potential in alveolar bone surgery and facial skull surgery are emerging (Bartold et al. 2000).

Neural Crest Stem Cells from Dental and Periodontal Tissues

Innovative therapeutic concept

Our innovation describes a new and previously overlooked way to prepare the endogenous repairing stem cells on the basis of their ecto-mesenchymal like phenotype (Molthera; PCT/EP2006/066221). Our new cell therapeutic product is already developed on a research laboratory scale. The patient-specific adult stem cells can be easily isolated and propagated without human serum (serum-free medium) from the oral cavity.

Thus neural crest cells might be the endogenous repair troop, which is also in the right differentiation stage to regenerate multi-lineage tissues. Generally, most organs including teeth develop from interactions between epithelial cells (oral epithelium) and mesenchymal cells (cranial neural-crest-derived ectomesenchyme).

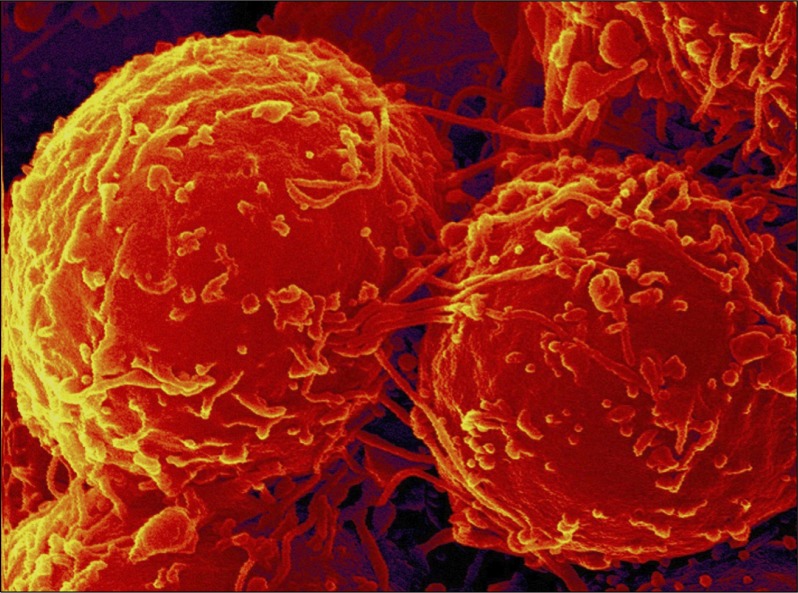

Several recent studies showed that neural crest-related stem cells can be isolated from mammalian craniofacial tissues (Fig. 1) such as periodontal ligament and from human palate as shown by our research group (Widera et al. 2007, 2009, Molnar et al. 2008) and by Techawattanawisal et al. (2007) or dental pulp as shown by our international research group (Kiraly et al. 2009).

Fig. 1.

SEM: Cultured palatal-derived stem cells (paldSC) form spheres.

These cells have in common that they form neurosphere-like clusters and proliferate in serum-free culture in the presence of fibroblast growth factor-2 (FGF-2) and epidermal growth factor (EGF). In light of these findings, the reason for this consortium is the identification of stem cells within the human palate. Palate is a highly regenerative and richly innervated craniofacial tissue. It is well described that wounds within oral mucosa heal rapidly. This capability for rapid regeneration may be explained either by the presence of growth factors, such as basic fibroblast growth factor in the saliva, or by the potential presence of at least one stem cell type within the tissue.

To decipher the developmental make-up of the alveolar and facial bone region, we will follow the path of the migratory neural crest, the neural crest lineage segregation as a blueprint for bone regeneration since it gives rise to bone progenitor tissues, which in turn are subjected to the influence of diverse bone extracellular matrices and peptide growth factors. We propose that the developmental history of a tissue is a highly instructive design template for the discovery of novel bioengineering tools and approaches (Kharazi et al. 2013). Further developments will include a formulation for clinical applications. This formulation will be based on scaffolds or delivery systems, which will be developed during this application. This will lead to the therapy of previously untreatable cases of facial defects and of advanced alveolar bone loss.

Purpose

Several tissue engineering approaches have been tried to stimulate bone formation. The addition of in vitro cultured mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) has proven to stimulate osteogenesis. Preclinical and clinical studies have demonstrated the ability of bone marrow-derived stem and progenitor cells to regenerate various tissues, including bone (Marx et al. 2012). To bypass the problem of selection, multiplication, and differentiation, most of the mentioned studies selected MSCs, multiplied them, and then differentiated them to the osteogenic lineage. As this is unreasonable to do in daily practice, in this “proof of principle” clinical-controlled study approach was chosen in which allogenic bone blocks will be combined with palatal-derived stem cells (paldSCs, see purpose).

Based on the hypothesis that the number of paldSCs is secondary, the individual potential of paldSCs to survive high stress and chemotactically attract osteogenic progenitor cells will dominate. As the augmentation material is far from local blood supply, it can be assumed that a natural selection procedure will be applied to the cells. As blood and oxygen supply are reestablished, the paldSCs could then unfold their full potential.

During the physiological bone healing, osteoprogenitor cells migrate into the defect, differentiate into osteoblasts, and produce calcified matrix. These osteoprogenitor cells derive from multipotent ecto-mesenchymal palatal-derived stem cells (paldSCs) that are recruited from palate. PaldSCs can tolerate low oxygen concentrations and have the potential for osteogenic, chondrogenic, and adipogenic differentiation, depending on the external stimulus by cytokines. To stimulate bone healing, various grafting techniques have been developed to supply additionally either cytokines, progenitor cells, suitable scaffolds, or any combination of them. In our study design we propose adding EMDOGAIN®. EMDOGAIN® can increase bone formation dynamics.

The purpose of this study is to evaluate the potential of Adult Palatinum as a Novel source of stem cells in combination with transplantation of OsteoGraft Spongiosa/Corticalis Bonering Blocks (maxgraft® bonering, botiss biomaterials, Germany) for one-stage bone augmentation and immediatly implant placement. These combination of methods for vertical augmentation in difficult anatomical sites will be tested in in a multicentric, “proof of principle” randomized, controlled, clinical, radiological and, histological trial.

Our group gained clinical experience with the bone block technique and isolation, cultivation, and characterization of palatinal-derived stem cells (paldSCs). Based on this key discovery we aim to develop a regenerative cell therapy.

Characterization of paldSCs by RT-PCR and flow cytometry revealed expression of several stem cell markers, such as nestin and Sox2 as well as STRO-1 and CD146. In 2007 our research group first describe the characterization and neuronal differentiation capacity of stem cells derived from inflamed periodontal tissues (Widera et al., 2007a). These so called periodontal-derived stem cells (pdSCs) were isolated by minimally invasive periodontal surgery and cultured as so-called dentaspheres under serum-free conditions in the presence of FGF-2 and EGF.

Differentiation studies revealed that paldSCs exhibit an osteogenic differentiation capacity. The osteogenic differentiation capacity of paldSCs was markedly developed suggesting that these cells might be a suitable cellular tool for bone regeneration purposes (Widera et al. 2007b).

Cultivation of paldSCs in neuronal differentiation media indicated the high neuronal differentiation capacity of these stem cells from periodontal tissue. Cells adopted a neuronal morphology and expressed a variety of neuronal markers, such as β-III-tubulin, Map2, GAD67, neurofilament-L (NF-L), neurofilament-M (NF-M), neurofilament-H (NF-H), and synaptophysion (results not shown).

Thus, we looked for a novel source of stem cells from the oral cavity being higly suited for regenerative purposes. In 2009 Widera et al. described for the first time the presence of nestin-positive neural crest-related stem cells within Meissner corpuscles and Merkel cell-neurite complexes located in the hard palate of adult Wistar rats. These cells were characterized by expression of nestin, the transcription factor Sox2, and additional neural crest markers such as Slug or Snail.

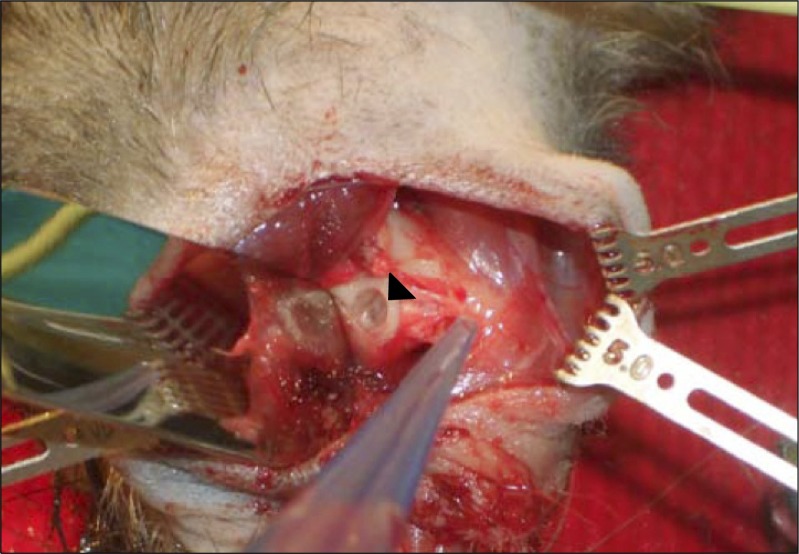

To prove for the putative bone regeneration capacity of paldSCs in an in vivo (Grimm et al. 2011) experimental setting an athymic rat model was conducted (Fig. 2). The current study demonstrates that isolating paldSCs from patients undergoing open flap minimally invasive periodontal surgery seems to be a simple and reliable method. These cells can be easily propagated ex vivo, thereby still preserving their stem cell state. As demonstrated previously and shown here, paldSCs are capable to differentiate both into the neuronal lineage as well as the osteogenic lineage. In vivo studies clearly showed that human adult pdSCs being transplanted into an athymic rat model were able to regenerate periodontal tissue elements at different levels.

Fig. 2.

Experimental setting on an athymic rat model.

Case presentation (proof of principle study) and Protocol specifications

The clinical study has been approved by the ethics committees of the Zahnärztekammer Westfalen/Lippe and the University of Münster (Germany).

The study will be conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (Fifth Revision, 2004). Patients older than 18 years with need of dental implant placement will be eligible if they had a maximum of 4 mm residual alveolar height. They had to be able to comply with study-related procedures, such as returning for follow- up examinations, exercising good oral hygiene, and being able to understand the nature of the proposed surgery. Written informed consent will be obtained prior to any study-related procedures. Exclusion criteria will be smoking, history, signs of malignancy, radiotherapy or chemotherapy, pregnancy or nursing, general contraindications for dental or surgical treatment, medications, treatments or diseases, which may have an effect on bone remodeling, bone or connective tissue metabolism, or an allergy to collagen.

The patients included in the study will be divided into three groups:

patients belonging to only test or comparitive groups and

patients with a split-mouth (cross-over) treatment

Primary parameter of the study will be new bone formation (NBF) including the histological assessment. Secondary parameters will be volume of the augmentate and bone height, see details.

Patient population

Thirty patients will be assessed for the study: Each patient will be randomly assigned to either comparative or test arm. Because of the surgical intervention, neither surgeon nor patient can be effectively blinded.

Step by step surgical procedures

For experienced oral surgeons, allograft bone blocks for block augmentation are the only real alternative to harvesting patients own autogenic bone blocks, preventing well known risks as donor-site morbidity, infection risk, pain and loss in bone stability.

As a carrier of our stem cell containing tissues we are using a sterile, high-safety (donor selection, virus testing, chemical cleaning, processing and sterilization) allograft product, derived of human donor bone, processed by the Cell+Tissue Bank Austria (CTBA). The high biologic regeneration capability of allogenic bone blocks results in a predictable clinical outcome.

Properties (Fig. 3)

Preserved biomechanical properties

Sterile without antigenic effects

Storable at room temperature for 5 years

Osteoconductive properties supporting natural and controlled tissue remodeling.

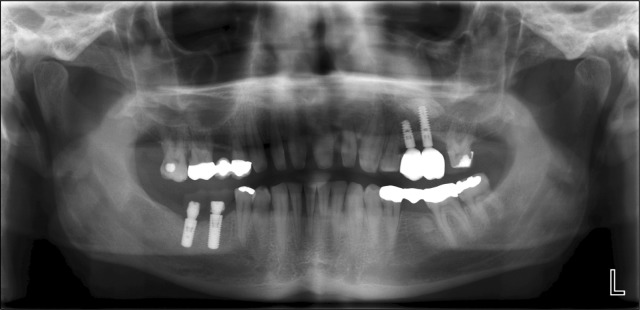

Fig. 3.

Allogen human bone rings (maxgraft® bonering, botiss bio-materials, Germany) with preserved biomechanical properties: Sterile without antigenic effects, Storable at room temperature for 5 years, Osteoconductive properties supporting natural and controlled tissue remodeling.

In the case presented here one allogen bonering was used. Until the lateral access to the maxillary sinus is prepared, the allogen bonering is steeped in native blood mixed. The bonering was introduced vertically into the maxillary sinus. It stabilizes the implant by buttressing them. The cortical portion of the rings was aligned cranially since this makes adaptation of the cancellous portion of the ring to the concave-shaped sinus floor much easier. The still existing cavity is filled with bone regeneration material. By screwing in a membrane screw, the bone ring is stabilized within the sinus and the implant is anchored in a primary stable position. This procedure enables good results with long-term effects. For harvesting the stem cell-containing subepithelial connective tissue graft from the palate a horizontal incision to the bone will be made 5 mm from the palatal gingival margin and the micro-blade will be subsequently placed parallel to the long axis of the roots. Another horizontal incision will be made 2 mm coronal to the first incision and the periosteum will be dissected before removing the wedge of soft tissue. An approximately 10×6 mm subepithelial connective tissue graft (SCTG) has been harvested from the palate in the second premolar to second molar region as the source of ecto-mesenchymal stem cells. The SCTG trimmed precisely to adapt to the recipient site. X-ray shows the situation after loading (Fig. 4) and finally clinical result with placed implants and superconstruction.

Fig. 4.

X-ray situation after loading and finally clinical result with placed implants and superconstruction.

In summary this case report confirms that bone regeneration is possible with PALATAL-DERIVED STEM CELLS.

References

- 1.Vinzenz K, Schaudy C. Osteoplastic surgery of the face -state of the art and future aspects. Eur Surg. 2011;43:1–14. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Grimm WD, Dittmar T, Varga G, Giesenhagen B. Use of stem-cell induced allogenic bonerings for pre-implanto-logical vertical augmentations of alveolar bone defects in humans- a clinical controlled study. Proceedings, BIT’s 5h Annual World Congress of Regenerative Medicine & Stem Cells 2012; December 2–4 2012; Guangzhou, China. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Grimm WD, Varga G, Dittmar T. Palate-derived ecto-mesenchymal stem cells in Periodontology and Implant Dentistry. Does The Chronically Inflamed Periodontium Harbour Cancer Stem Cells?. Proceedings, BIT’ 5th Annual World Congress of Regenerative Medicine & Stem Cell 2012; December 2–4 2012; Guangzhou, China. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cheng I, Mayle RE, Cox CA, Park DY, Smith RL, Corcoran-Schwartz I, Ponnusamy KE, Oshtory R, Smuck MW, Mitra R, Kharazi AI, Carragee EJ. Functional assessment of the acute local and distal transplantation of human neural stem cells after spinal cord injury. Spine J. 2012;12:1040–1044. doi: 10.1016/j.spinee.2012.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Plöger Mathias, Schau I. Kieferkammrekonstruktion mit CAD-CAM-gefertigten allogenen Knochenblöcken. Quintessenz Publishing Company; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Harris RJ. Successful root coverage: a human histologic evaluation of a case. Int J Periodontics Restorative Dent. 1999;19:439–447. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Greiner JF, Hauser S, Widera D, Müller J, Qunneis F, Zander C, Martin I, Mallah J, Schuetzmann D, Prante C, Schwarze H, Prohaska W, Beyer A, Rott K, Hütten A, Gölzhäuser A, Sudhoff H, Kaltschmidt C, Kaltschmidt B. Efficient animal-serum free 3D cultivation method for adult human neural crest-derived stem cell therapeutics. Eur Cell Mater. 2011;22:403–419. doi: 10.22203/ecm.v022a30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Widera D, Zander C, Heidbreder M, Kasperek Y, Noll T, Seitz O, Saldamli B, Sudhoff H, Sader R, Kaltschmidt C, Kaltschmidt B. Adult palatum as a novel source of neural crest-related stem cells. Stem Cells. 2009;27:1899–1910. doi: 10.1002/stem.104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Heinemann F, Götz W. Oral tissue engineering and implants. Ann Anat. 2012;194:501. doi: 10.1016/j.aanat.2012.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Morsczeck C, Petersen J, Völlner F, Driemel O, Reichert T, Beck HC. Proteomic analysis of osteogenic differentiation of dental follicle precursor cells. Electrophoresis. 2009;30:1175–1184. doi: 10.1002/elps.200800796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mao JJ, Giannobile WV, Helms JA, Hollister SJ, Krebsbach PH, Longaker MT, Shi S. Craniofacial tissue engineering by stem cells. J Dent Res. 2006;85:966–979. doi: 10.1177/154405910608501101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schomann T, Qunneis F, Widera D, Kaltschmidt C, Kaltschmidt B. Improved method for ex ovo-cultivation of developing chicken embryos for human stem cell xenografts. Stem Cells In. 2013;2013:960958. doi: 10.1155/2013/960958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Marx RE, Tursun R. A qualitative and quantitative analysis of autologous human multipotent adult stem cells derived from three anatomic areas by marrow aspiration: tibia, anterior ilium, and posterior ilium. Oral Craniofac Tissue Eng. 2011;1:98–102. doi: 10.11607/jomi.te10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Arnold WH, Becher S, Dannan A, Widera D, Dittmar T, Jacob M, Mannherz HG, Dittmar T, Kaltschmidt B, Kaltschmidt C, Grimm WD. Morphological characterization of periodontium-derived human stem cells. Ann Anat. 2010;192:215–219. doi: 10.1016/j.aanat.2010.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bartold PM, McCulloch CA, Narayanan AS, Pitaru S. Tissue engineering: a new paradigm for periodontal regeneration based on molecular and cell biology. Periodontol 2000. 2000;24:253–269. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0757.2000.2240113.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Widera D, Grimm WD, Moebius JM, Mikenberg I, Piechaczek C, Gassmann G, Wolff NA, Thévenod F, Kaltschmidt C, Kaltschmidt B. Highly efficient neural differentiation of human somatic stem cells, isolated by minimally invasive periodontal surgery. Stem Cells Dev. 2007;16:447–460. doi: 10.1089/scd.2006.0068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Widera D, Grimm WD, Möbius JM, Dannan A, Becher S, Mikenberg I, Piechaczek C, Gassmann G, Kaltschmidt B. Human periodontium-derived neural stem cells: chance or risk? Regenerative Medicine. 2007;2:3–61. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Molnár B, Kádár K, Király M, Porcsalmy B, Somogyi E, Hermann P, Grimm WD, Gera I, Varga G. Isolation, cultivation and characterisation of stem cells in human periodontal ligament. Fogorv Sz. 2008;101:155–161. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Techawattanawisal W, Nakahama K, Komaki M, Abe M, Takagi Y, Morita I. Isolation of multipotent stem cells from adult rat periodontal ligament by neurosphere-forming culture system. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2007;357:917–923. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.04.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Király M, Porcsalmy B, Pataki A, Kádár K, Jelitai M, Molnár B, Hermann P, Gera I, Grimm WD, Ganss B, Zsembery A, Varga G. Simultaneous PKC and cAMP activation induces differentiation of human dental pulp stem cells into functionally active neurons. Neurochem Int. 2009;55:323–332. doi: 10.1016/j.neuint.2009.03.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kharazi A, Levy ML, Visperas MC, Lin CM. Chicken embryonic brain: an in vivo model for verifying neural stem cell potency. J Neurosurg. 2013;119:512–519. doi: 10.3171/2013.1.JNS12698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vertelov G, Kharazi L, Muralidhar MG, Sanati G, Tankovich T, Kharazi A. High targeted migration of human mesenchymal stem cells grown in hypoxia is associated with enhanced activation of RhoA. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2013;4:5. doi: 10.1186/scrt153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Marx RE, Harrell DB. Translational Research: The CD34+ cell is crucial for large-volume bone regeneration from the milieu of bone marrow progenitor cells in craniomandibular reconstruction. Int J Oral Maxillofac Implants. 2014;29:e201–e209. doi: 10.11607/jomi.te56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Grimm WD, Dannan A, Becher S, Gassmann G, Arnold W, Varga G, Dittmar T. The ability of human periodontium-derived stem cells to regenerate periodontal tissues: a preliminary in vivo investigation. Int J Periodontics Restorative Dent. 2011;31:e94–e101. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Keeve PL, Dittmar T, Gassmann G, Grimm WD, Niggemann B, Friedmann A. Characterization and analysis of migration patterns of dentospheres derived from periodontal tissue and the palate. J Periodontal Res. 2013;48:276–285. doi: 10.1111/jre.12005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]