Abstract

Ovarian cancer is the leading cause of death among gynecological tumors. Carboplatin/paclitaxel represents the cornerstone of front-line treatment. Instead, there is no consensus for management of recurrent/progressive disease, in which pegylated liposomal doxorubicin (PLD) ± carboplatin is widely used. We performed a systematic review and metaanalysis to evaluate impact of PLD-based compared with no-PLD-based regimens in the ovarian cancer treatment. Data were extracted from randomized trials comparing PLD-based treatment to any other regimens in the January 2000–January 2013 time-frame. Study end-points were overall survival (OS), progression free survival (PFS), response rate (RR), CA125 response, and toxicity. Hazard ratios (HRs) of OS and PFS, with 95% CI, odds ratios (ORs) of RR and risk ratios of CA125 response and grade 3–4 toxicity, were extracted. Data were pooled using fixed and random effect models for selected endpoints.

Fourteen randomized trials for a total of 5760 patients were selected and included for the final analysis, which showed no OS differences for PLD-based compared with other regimens (pooled HR: 0.94; 95% CI: 0.88–1.02; P = 0.132) and a significant PFS benefit of PLD-based schedule (HR: 0.91; 95% CI: 0.86–0.96; P = 0.001), particularly in second-line (HR: 0.85; 95% CI: 0.75–0.91) and in platinum-sensitive (HR: 0.83; 95% CI: 0.74–0.94) subgroups. This work confirmed the peculiar tolerability profile of this drug, moreover no difference was observed for common hematological toxicities and for RR, CA125 response.

PLD-containing regimens do not improve OS when compared with any other schedule in all phases of disease. A marginal PFS advantage is observed only in platinum-sensitive setting and second-line treatment.

Keywords: ovarian cancer, systemic chemotherapy, pegylated liposomal doxorubicin, randomized clinical trials, metaanalysis

Introduction

Ovarian cancer (OC) is the leading cause of death in gynecological tumors.1,2 Presently, the gold standard frontline treatment is represented by carboplatin/paclitaxel and bevacizumab.3-7 Beyond the first line, the platinum-free interval (PFI), i.e., the time between the end of the last treatment course and the occurrence of relapse or progression, is widely considered a critical issue for selecting the chemotherapy regimen.8,9 International guidelines recommend a re-challenge with carboplatin-based combination, for patients who relapse after at least 12 mo from the last chemotherapy course (platinum-sensitive patients).10 In particular, carboplatin/pegylated liposomal doxorubicin (PLD) combination is considered in the clinical practice an alternative choice compared with carboplatin/paclitaxel in this specific setting.11-14

Patients with a PFI of 6–12 mo are defined platinum-partially-sensitive and showed an intermediate likelihood of responding to a platinum-based regimen.14 In this subgroup it has been recently hypothesized, based on preclinical and clinical findings, a potential benefit derived from an “artificial” prolongation of the PFI by the use of a platinum-free regimen (such as trabectedine–PLD combination).15-17 These trials reported significant advantage in progression free survival (PFS) which did not translate in overall survival (OS) prolongation.18,19

Patients with a platinum-refractory disease (with a PFI < 6 mo) are reported to gain little benefit from monotherapy with several drugs such as PLD, topotecan, etoposide, taxanes, gemcitabine, and oxaliplatin.20-26 However, none of them demonstrated to significantly improve OS. Therefore, no standard approach has been defined in this scenario.21,24,27-29

PLD is a liposome-encapsulated formulation of doxorubicin, a cytotoxic anthracycline antibiotic obtained from Streptomyces peucetius var caesius. The mechanism of its antitumor action is still not fully understood but it is thought to block topoisomerase I and intercalate between adjacent base pairs of the double helix of DNA thus impairing the synthesis of DNA, RNA, and proteins.30,31

Overall, PLD is considered one of the most effective therapeutic agents for the treatment of recurrent and progressive disease: it may be used in platinum-based regimens for platinum-sensitive patients, in combination with trabectedin in platinum-partially-sensitive disease and as single agent for platinum-refractory patients, even if no significant advantages over other drugs have been demonstrated in the latter setting.20,25

From August 2011 until early 2013, PLD was out of production due to technical issues determining difficulties and doubts on use of this agent in daily clinical practice.32

Recent retrospective studies have raised some concern on the real efficacy of PLD in OC treatment.1,33,34

Results

Studies selection

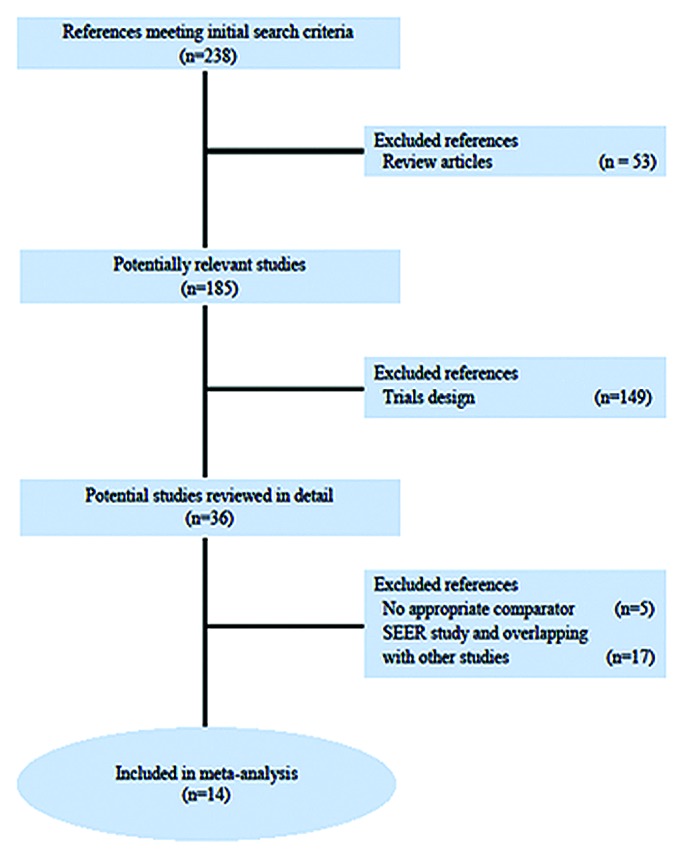

Figure 1 reports the PRISMA chart related to Randomized Clinical Trials (RCTs) selection and search strategy. In the time frame covered by the systematic review (2000–2013), 238 studies were reported as full papers or meeting abstracts. Two hundred and two studies were initially excluded: 53 of these were reviews and 149 were excluded for trial design without a clear-cut PLD-based design. Subsequently, we examined in detail the remaining 36 trials. Among them 17 included PLD comparison did not meet selection criteria and were excluded from the final analysis. Further, 5 trials were excluded for peculiar reasons, in particular: Monk et al. and Vergote et al. (2009) because control arm included PLD; Gordon et al. (2001) reported preliminary data subsequently published in 2004, in an article included in the final analysis; Markman et al. (2010) duplicate data reported in Alberts et al. (2008); HECTOR trial presented on ASCO 2012 because data were not evaluable at single agent level.18,35-38 Fourteen trials for a total of 5760 patients were selected and included in the final analysis.11,20,21,28,37,39-48 Two trials of Vergote and Rose were analyzed only for RR for missing data on survival endpoints. The trial of Kaye et al. and AURELIA trial, both designed for multiple arms comparison, were analyzed for single comparison considering an aggregate arm of different olaparib concentrations in the first study and comparing bevacizumab-free arms in the second study. At least one data-comparison in terms of survival, RR, Ca125 response and toxicity was reported in all selected RCTs, which were therefore eligible for the endpoint analysis (Tables 1 and 2).

Figure 1. PRISMA chart showing the trial exclusion and inclusion process in the metaanalysis. SEER, Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results.

Table 1. Survival data extracted from analyzed clinical trials.

| Author | Year | No. pts | Arms | Phase | OS | PFS | OS P (log rank test) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (HR) | (HR) | ||||||

| I line | |||||||

| Pignata et al.39 | 2011 | 820 | CPLD vs CP | III | 0.82 | 0.95 | 0.58 |

| (0.72–1.12) | (0.81–1.13) | ||||||

| Bookman et al.40 | 2009 | 862 | CPLD vs CP | III | 0.97 | 0.96 | 0.79 |

| (0.83–1.13) | (0.93–1.09) | ||||||

| II line | |||||||

| Bafaloukos et al.44 | 2010 | 189 | CPLD vs CP | II | - | 1.15 | - |

| (0.78–1.66) | |||||||

| Kaye et al.41 | 2011 | 97 | PLD vs O | II | - | 0.91 | 0.66 |

| (0.6–1.39) | |||||||

| Kaye et al.41 | 2011 | 97 | PLD vs O | II | - | 0.86 | 0.66 |

| (0.56–1.3) | |||||||

| Albert et al.43 | 2008 | 61 | CPLD vs C | III | 0.46 | 0.54 | 0.03 |

| (0.22–0.95) | (0.32–0.93) | ||||||

| CALYPSO11 | 2010 | 976 | CPLD vs CP | III | 0.99 | 0.82 | 0.05 |

| (0.85–1.16) | (0.72–0.94) | ||||||

| Ferrandina et al.28 | 2008 | 153 | PLD vs G | III | - | - | 0.411 |

| Mutch et al.20 | 2007 | 195 | PLD vs G | III | 1.02 | - | 0.87 |

| (0.71–1.42) | |||||||

| Gordon et al.36 | 2004 | 474 | PLD vs T | III | 0.82 | 0.79 | 0.05 |

| (0.68–1) | (0.67–0.94) | ||||||

| III line | |||||||

| Colombo et al.45 | 2012 | 829 | PLD vs Patupilone | III | 1.07 | 0.95 | |

| (0.91–1.26) | (0.8–1.12) |

Abbreviations: OS, overall survival; PFS, progression free survival; HR, hazard ratio; CPLD, carboplatin and pegylated liposomal doxorubicin; CP, carboplatin and paclitaxel; PLD, pegylated liposomal doxorubicin; O, olaparib; C, carboplatin; G, gemcitabine; T, topotecan.

Table 2. Response rate and toxicities data extracted from analyzed clinical trials.

| Author | Trial design | RR (%) | Hematologic toxicity | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TCP (%) | Anemia (%) | NTP (%) | |||

| I line | |||||

| Pignata et al.39 | CPLD | 57 | 16 | 10 | 43 |

| CP | 59 | 2 | 4 | 50 | |

| Bookman et al.40 | CPLD | - | 38 | - | 69 |

| CP | - | 22 | - | 59 | |

| II line | |||||

| CALYPSO11 | CPLD | - | 16 | 8 | 35 |

| CP | - | 6 | 5 | 45 | |

| Bafaloukos et al.44 | CPLD | 51 | 11 | - | 35 |

| CP | 57 | 2 | - | 30 | |

| Alberts et al.43 | CPLD | 52 | 29 | 16 | 29 |

| C | 29 | 10 | 0 | 3 | |

| Kaye et al.41 | PLD | 25 | - | 0 | - |

| O | 18 | - | 6 | - | |

| Kaye et al.41 | PLD | 18 | - | 0 | - |

| O | 31 | - | 13 | - | |

| Ferrandina et al.28 | PLD | 16 | 0 | 7 | 6 |

| G | 29 | 5 | 5 | 23 | |

| O’ Byrne et al.48 | PLD | 17.8 | - | - | - |

| P | 22.4 | - | - | - | |

| Mutch et al.20 | PLD | 8 | 5 | 2 | 18 |

| G | 6 | 6 | 3 | 38 | |

| Gordon et al.36 | PLD | 20 | 1 | 28 | 12 |

| T | 17 | 34 | 5 | 77 | |

| Rose et al.47 | PLD | 10 | - | - | - |

| CC | 32 | - | - | - | |

| Aurelia46 | PLD | 7.9 | - | - | - |

| T | 3.3 | - | - | - | |

| Aurelia46 | PLD | 7.9 | - | - | - |

| P | 12.6 | - | - | - | |

| III line | |||||

| Vergote et al.35 | PLD | 11 | 7 | 5 | 14 |

| Canfosfamide | 4 | 5 | 11 | 8 | |

| Colombo et al.45 | PLD | 7.9 | - | 3.7 | 10 |

| Patupilone | 15.5 | - | 4.5 | 3 | |

Abbreviations: OR, odds ratio; rr, risk ratio; CPLD, carboplatin and pegylated liposomal doxorubicin; CP, carboplatin and paclitaxel; PLD, pegylated liposomal doxorubicin; O, olaparib; C, carboplatin; G, gemcitabine; T, topotecan.

Study characteristics

These trials included two front-line (involving 1682 patients), ten second-line (2788 patients, 1669 of which were platinum-sensitive and 1119 platinum-refractory) and two third-line (1290 platinum-refractory patients) trials in which PLD-based treatment was compared with other treatment.

The quality assessment of selected studies was evaluated according to the Cochrane reviewers’ handbook for 4 requirements: method of randomization, allocation concealment, blindness, and adequacy of follow-up. Nine trials were scored A (low risk of bias), four trials were scored B (intermediate risk of bias), and one trial was scored C (high risk of bias) (Table 3).49,50

Table 3. Quality assessment.

| Included studies | Method of randomization | Allocation concealment | Blindness | Withdrawal and dropout | Baseline | Quality level |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pignata et al.39 | Centralized | Central office | No | Detailed criteria | Identical baseline | A |

| Bookman et al.40 | Centralized | Not detailed | No | Detailed criteria | Identical baseline | B |

| CALYPSO11 | Centralized | Central office | No | Detailed criteria | Identical baseline | A |

| Bafaloukos et al.44 | Centralized | Central office | No | Detailed criteria | Identical baseline | A |

| Alberts et al.43 | Centralized | Not detailed | No | Detailed criteria | Identical baseline | B |

| Kaye et al.41 | Centralized | Central office | No | Not detailed | Identical baseline | B |

| Ferrandina et al.28 | Centralized | Central office | Yes | Detailed criteria | Identical baseline | A |

| Mutch et al.20 | Centralized | Not detailed | No | Detailed criteria | Identical baseline | B |

| Gordon et al.36 | Centralized | Central office | No | Detailed criteria | Identical baseline | A |

| O’Byrne et al.48 | Not reported | Not detailed | No | Not detailed | Identical baseline | C |

| AURELIAl46 | Centralized | Central office | No | Detailed criteria | Identical baseline | A |

| Colombo et al.45 | Centralized | Central office | No | Detailed criteria | Identical baseline | A |

| Vergote et al.35 | Centralized | Central office | No | Detailed criteria | Identical baseline | A |

| Rose et al.47 | Centralized | Not detailed | No | Not detailed | Identical baseline | B |

Quantitative data reports

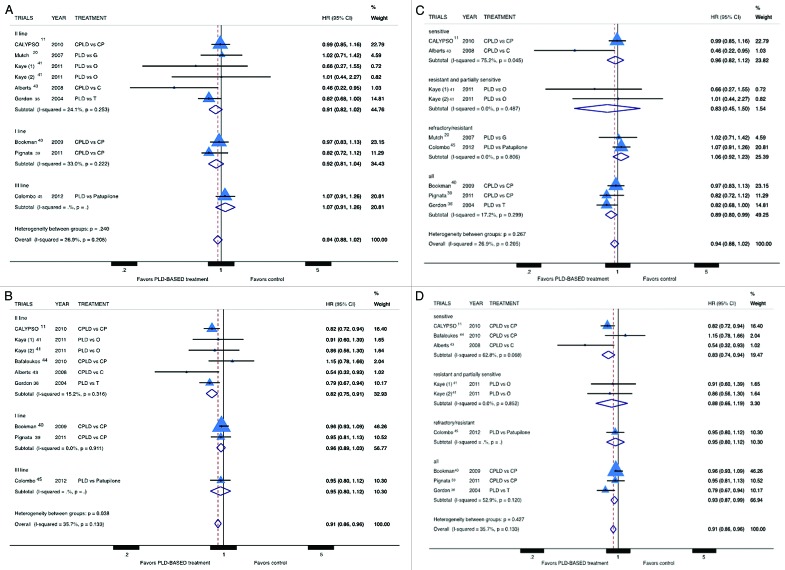

Six trials were excluded from OS analysis because did not report retrievable data for this endpoint. PLD was not associated with improved survival in OC patients (pooled HR: 0.94; 95% CI: 0.88–1.02; P = 0.132) (Fig. 2A and C) and this result was confirmed in all subgroup analyses. The trial by Gordon et al. was the only RCT that reported a significant improvement in OS for PLD compared with topotecan. PFS data were not provided in 6 trials therefore these trials were excluded from PFS analysis. PLD-based treatment was found to be significantly associated with improved PFS (pooled HR: 0.91; 95% CI: 0.86–0.96; P = 0.001) (Fig. 2B and D). However, the analyses of study subgroups demonstrate a significant PFS advantage only in second-line setting (pooled HR: 0.85; 95% CI: 0.75–0.91) and in platinum-sensitive patients (pooled HR: 0.83; 95% CI: 0.74–0.94), while analysis of other study-subgroups did not demonstrate a statistically significant advantage for PLD.

Figure 2. Comparison of OS and PFS, according to treatment line (A andB respectively) or platinum sensitivity (C and D respectively), between patients treated with a PLD-containing regimen vs. any other PLD-free schedule. Abbreviation: OS, overall survival; PFS, progression free survival; HR, hazard ratio; CPLD, carboplatin and pegylated liposomal doxorubicin; CP, carboplatin and paclitaxel; PLD pegylated liposomal doxorubicin; O, olaparib; C, carboplatin; G, gemcitabine; T, topotecan.

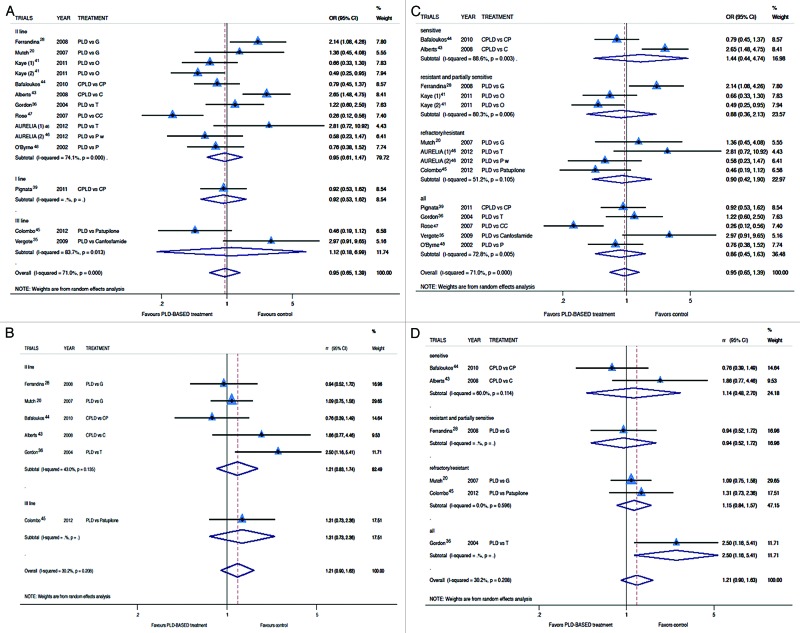

Two trials did not report data in term of RR and were excluded from this analysis. The RR analysis revealed no advantage for PLD-based treatment (Fig. 3A and C) in all study-subgroups (OR for RR: 0.95; 95% CI: 0.65–1.39; P = 0.802). The analysis of Ca125 response confirmed the absence of any advantage derived from PLD-based treatment compared with control arm (Risk Ratio for Ca125 response: 1.21; 95% CI: 0.90–1.63) (Fig. 3B and D). Again, none of the study-subgroup analyses demonstrated a significant result. Common adverse events were similar in both arms. We analyzed specifically hematological toxicity: among toxicities, anemia and neutropenia were more frequent in PLD-free treatment groups; however these differences were not statistically significant. Thrombocytopenia was revealed more frequent in the PLD group (0.74, 95% CI: 0.35–1.60) but again statistical significance was not reached. Other toxicities were not comparable for different schedules and agents in control arm for different tolerability profile. As expected palmar-plantar erythrodysesthesia was more common in PLD arms while neurotoxicity and alopecia occurred more frequently in taxane treated patients (Table 4).

Figure 3. Comparison of RR and Ca125 response, according to treatment line (A and B respectively) or platinum sensitivity (C andD respectively), between patients treated with a PLD-containing regimen vs. any other PLD-free schedule. Abbreviation: OR, odds ratio; rr, risk ratio; CPLD, carboplatin and pegylated liposomal doxorubicin; CP, carboplatin and paclitaxel; PLD, pegylated liposomal doxorubicin; O, olaparib; C, carboplatin; G, gemcitabine; T, topotecan.

Table 4. Most common adverse events analyzed in the metaanalysis.

| Adverse events | Overall risk ratio (95% CI) | P value |

|---|---|---|

| Anemia | 0.94 (0.42–2.11) | 0.88 |

| Neutropenia | 0.89 (0.57–1.39) | 0.61 |

| Thrombocytopenia | 1.34 (0.62–2.90) | 0.45 |

| Neurotoxicity | 0.48 (0.16–1.41) | 0.18 |

| Palmar–plantar erythrodysesthesia | 26.33 (11.76–58.99) | <0.01 |

| Alopecia | 0.22 (0.10–0.46) | <0.01 |

Risk of bias in individual studies

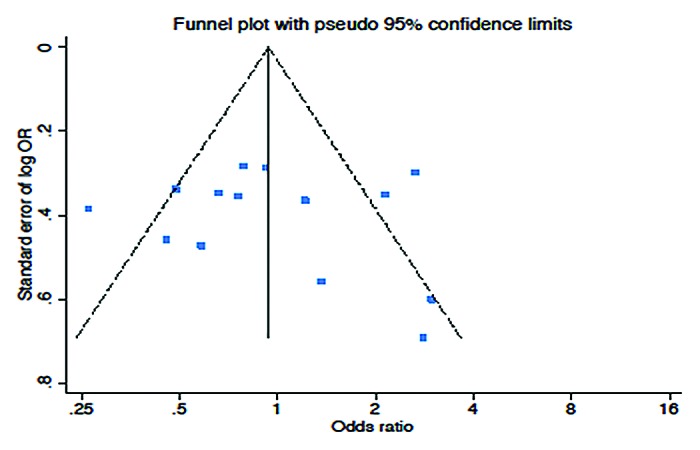

A Begg funnel plot showed no significant evidence for publication bias (Fig. 4).

Figure 4. Funnel plot (Begg test) assessing publication bias.

Discussion

This metaanalysis of 14 RCTs (for a total of 5760 patients), comparing PLD to any other drug in OC treatment, demonstrated an advantage in terms of PFS for PLD-based regimen (pooled HR: 0.91; 95% CI: 0.86–0.96; P = 0.001). However, no significant advantages were found in terms of OS, RR or Ca125-response despite of subgroups. This work confirmed the peculiar tolerability profile of this drug; moreover no differences were observed in our analysis if we consider only the most common hematological toxicities.

Two recent metaanalyses published by Cochrane Collaboration analyzed the efficacy of PLD in OC in first line of treatment and in disease recurrence respectively. In the first work the authors concluded that carboplatin–PLD is a reasonable alternative to carboplatin–paclitaxel for similar efficacy and a different profile of toxicity.51 The second Cochrane study and a metaanalysis conducted by Gibson et al. and published on the same period, demonstrated both that carboplatin-PLD combination is a reasonable alternative to carboplatin–paclitaxel for better tolerability while a monotherapy with PLD is a valid option also in a platinum-refractory setting. However Gibson et al. did not evaluate the efficacy endpoints in the different clinical subgroups.52 Moreover, in these works, the authors pay particular attention to tolerability and such analysis leads them to conclude that, despite of similar efficacy, the choice of regimen could be based on individual patient preference on the basis of side effects.52,53 In particular Lawrie et al. recognized a role of PLD in refractory-platinum subgroup without comparison with other single agents and without providing evidence in support of a rational timing of individual agent administration.52

Furthermore Lawrie et al. included in final analysis also the trials containing PLD in control arm.

On the basis of these findings, which are of relevance taking into account that tolerability is an important endpoint in the palliative setting, we focused however our attention on the analysis of drug effectiveness in terms of survival endpoints, stratifying the trials for treatment line and platinum sensitivity, that are the most important parameters in decision making.

In our study, the most impressive results were obtained when we analyzed the activity is different PLD second-line treatment and platinum-sensitive patients. Focusing on the first-line treatment, our results confirmed that carboplatin–paclitaxel combination is the only evidence-based choice with recent implementation of bevacizumab addition. Indeed, the results of this pooled analysis with a non-significant HR 0.92 for OS and HR 0.96 for PFS in this setting evidenced non-superiority of PLD in combination with carboplatin as compared with carboplatin-paclitaxel. These findings partially support the common belief that carboplatin–PLD is an adequate alternative choice in the management of first-line OC patients. In fact none of the first-line trials was based on a non-inferiority design which could actually demonstrate non-inferiority of carboplatin–PLD.

Moreover, the use of carboplatin–PLD in first line treatment needs to be investigated in new trials comparing this schedule to bevacizumab-containing regimen because at present, this anti-VEGF Ab is the only agent able to increase survival when added to standard carboplatin-paclitaxel front-line chemotherapy.6,7,54

In second-line (first recurrence or progression), PLD-based treatment produced a significant improvement in term of PFS, which did not translate in longer OS. This PFS advantage was marginal in unselected patients, becoming more evident in platinum-sensitive disease.

Most of the trials evaluated patients non-selected for platinum-sensitivity status. Indeed, subgroup analyses reported a clear survival advantage in platinum-sensitive OC patients supporting PLD-based treatment as preferred choice in this particularly setting.

According to this view, Gordon et al. in 2004 reported a clinical advantage in terms of PFS for PLD compared with topotecan on the whole study population, which was however restricted to platinum-sensitive disease. The results of this trial led to the administration in the clinical practice of PLD to OC patients regardless of platinum-sensitivity status. This highlights the need of trial design considering the platinum-sensitivity status.21

Our results on the PFS end-point in platinum-sensitive subgroup showed an advantage for PLD- containing regimen. However, forest plots in Figure 2B and D shows the preeminent weight of Calypso trial in the imbalance in favor of PLD. That study is a non-inferiority trial designed to compare the carboplatin-PLD to carboplatin-paclitaxel combination: PLD-based regimen produces an advantage of less than two months in PFS (HR 0.82) without any advantage in OS. Anyhow, a subset analysis of the CALYPSO phase III trial about health-related quality of life in platinum-sensitive OC, confirmed a slightly lower toxicity and a lower impact on the body image item in carboplatin-PLD arm compared with carboplatin-paclitaxel with borderline differences on most other items.55 The results reported in this trial, in our opinion, failed to provide a formal proof that PLD is the best option for clinical practice.11

On this basis, it is possible to conclude that, at present, the cornerstone of platinum-sensitive OC treatment is represented by a re-challenge with carboplatin-based chemotherapy; additional evidence is required in order to consider PLD as a first choice in this specific setting.56

Even in platinum-sensitive patients, the anti-VEGF monoclonal antibody bevacizumab is the only agent that demonstrated able to produce a consistent 4 mo improvement in terms of PFS, (HR 0.48) in combination to platinum-containing second-line treatment.57

As a pitfall of our analysis, none of the trials examined was specifically designed for the partially platinum-sensitive setting. Indeed, the MITO-8 trial, investigating the role of PLD against CP in this setting, is presently ongoing, and the trial by Monk et al., comparing PLD vs. PLD/trabectedine, could not be included in our analysis.18,58 Ferrandina et al. described an advantage in terms of PFS for PLD compared with gemcitabine in patients who experienced recurrence within 12 mo.28 If we consider that all trials designed for refractory patients did not report an advantage for PLD compared with any other drug, it is conceivable that these results were mostly produced in the patient cohort relapsing between 6 and 12 mo.

Finally our analysis highlights the total ineffectiveness of PLD compared with any other agent to produce an improvement in any of the pre-specified end-points in the platinum-refractory setting. Recently, two mono-institutional experiences suggested that in platinum-refractory setting the use of PLD did not result in survival benefit.33,34 The only study designed for platinum-resistant and refractory patients (Mutch et al.) in second-line, did not show any advantage for PLD compared with gemcitabine.20 Furthermore, this trial reported that PLD was not superior even in the toxicity profile. A survival advantage for paclitaxel compared with PLD was reported in O’Byrne trial; however, these results have never been published in extenso.48 On this basis, in the platinum-resistant setting, topotecan or gemcitabine still represent an adequate alternative to PLD despite of a low RR and moderate bone marrow toxicity.

Again, the most important results on this difficult subgroup of patients have been achieved by bevacizumab, which, in the AURELIA trial, was reported to almost double the PFS of platinum-refractory OC patients (6.7 vs. 3.4 mo). Moreover, the best outcome was reported in the subgroup of patients treated with the combination of weekly paclitaxel and bevacizumab that showed an interesting median PFS of 10.4 mo.46,59

This metaanalysis presents some limitations: it was performed on literature data and was not possible to retrieve data about all end-points from all the studies; although the included trials reported homogeneity on many points, the differences in the agents used in the control arms may had produced another potential bias.

In conclusion the absence of advantage in terms of OS and the marginal benefit in terms of PFS, achieved only in selected groups of patients with a “favorable” outcome, indicate the need to reconsider the real impact of PLD in clinical practice, also taking into account the PLD-related toxicities. On the other hand, the reported findings do not argue against PLD use in clinical practice, but provide novel information which can be of help in the design of prospective studies, where combination with molecular targeted agents should be explored.

According to our results, even if PLD treatment produces a minimal advantage in terms of PFS, this effect does not translate into a significant impact in terms of OS. On this basis, PLD should not be formally considered “the first choice agent” after first-line treatment failure, especially in platinum-refractory setting, where none of the currently used agents (with the exception, perhaps, of bevacizumab) reported to be able to change the OC patient outcome. Individual treatment selection in the clinical practice should consider toxicity experienced by the patient, offering for instance PLD to patients with taxane-related neurotoxicity. New treatment approaches, largely based on preclinical findings, with validated efficacy predictors and investigated by trial design based on platinum-sensitivity are eagerly awaited.

Patients and Methods

Eligibility criteria

Eligible trials included patients with the following characteristics: diagnosis of OC and common demographic characteristics of trial population (age and performance status). In the experimental arm, patients were treated with single PLD or PLD-containing regimen, while in the control arm with other single agent or PLD-free combination. Adequate staging and follow-up had to be described. We excluded: non-randomized studies; reports in languages other than English; non-comparable end-points; studies that described particular administration of chemotherapy (e.g., intra-arterial or intra-peritoneal infusion); studies not reporting any data regarding our pre-specified end-points. To avoid overlapping patient data in duplicate publications, only larger or updated publications were included.

Information sources

Eligible trials were retrieved from PubMed, Embase, the Central Registry of Controlled Trials of the Cochrane Library) and major meeting abstract databases (ASCO and ESMO) and selected studies published between January 2000, at the time of PLD treatment introduction, and January 2013.

Search strategy

Search strategy and study identification were conducted as described in previous works.60,61 Briefly, we performed a literature search of main scientific databases. Published trials, in form of full article or abstract, were eligible. In this analysis only English-written prospective studies were allowed, in order to reduce or minimize the risk of selection or information bias.62,63 The main keywords and their combination used for the search were: ovarian cancer, systemic chemotherapy, pegylated liposomal doxorubicin, randomized clinical trials. The “related articles” function was used to include as many studies as possible in the first screening analysis and, subsequently, retrieved articles were screened to ensure accuracy of the search strategy.

Data collection

Studies were independently evaluated by two investigators (N.S. and D.C.) to select homogeneous reports. We extracted and evaluated different variables from selected trials such as number of patients enrolled, year of publication, treatment schedule, and efficacy results. Data regarding the occurrence of toxicities were obtained from the safety profile reported in each study. Any discrepancy was discussed and resolved by two additional reviewers (P.T. and P.T.).64

Study endpoints

Study end-points were OS, PFS, response rates (RRs), CA125 response, and toxicity rates (TRs). The collected efficacy outcomes included median survival and clinical response.

Metaanalysis

A metaanalysis was performed in order to evaluate the overall effects of the PLD treatment vs. control arm on the pre-specified end-points.65 Survival data were extracted as hazard ratios (HRs) of OS and PFS with relative confidence intervals (95% CI). The interaction between survival and PLD-treatment was obtained from each study by the HRs logarithm. The overall effect of PLD treatment on RR, CA125-response and toxicity was calculated using method for dichotomous data (odds ratio and risk ratio; 95% CI assessment). HR > 1 reflects more deaths or progression in the PLD-based arm. OR > 1 reflects a favorable outcome in the PLD-based arm for response, survival probability or an unfavorable outcome for toxicities. A subgroup analysis, based on the platinum-status and line of treatment, was performed for all end-points. The Cochrane Q-test and I2 statistics were used to assess heterogeneity between studies. For all endpoints the analyses were performed with the Cochrane-Mantel-Haenszel fixed-effects model and the DerSimonian and Laird random-effects model.66-68 The occurrence of publication bias was investigated through the Begg test and by visual inspection of funnel plots.69 A two-tailed P value ≤ 0.05 was considered statistically significant. All the statistical analyses were performed by STATA™ SE v. 12.0 (STATA® Corporation, Texas, USA) and according to PRISMA guidelines.70

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

Acknowledgments

This work is supported by PhD program of Magna Graecia University: PhD in molecular oncology and translational and innovative medical and surgical techniques.

Glossary

Abbreviations:

- CI

confidence intervals

- OC

ovarian cancer

- PLD

pegylated liposomal doxorubicin

- OS

overall survival

- PFS

progression free survival

- RRs

response rate

- HR

hazard ratio

- ORs

odds ratio

- RCTs

randomized clinical trials

- TRs

toxicity rates

- PFI

platinum-free interval

- RECIST

response evaluation criteria in solid tumor

- VEGF

vascular endothelial growth factor

References

- 1.Ferlay J, Shin HR, Bray F, Forman D, Mathers C, Parkin DM. Estimates of worldwide burden of cancer in 2008: GLOBOCAN 2008. Int J Cancer. 2010;127:2893–917. doi: 10.1002/ijc.25516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Siegel R, DeSantis C, Virgo K, Stein K, Mariotto A, Smith T, Cooper D, Gansler T, Lerro C, Fedewa S, et al. Cancer treatment and survivorship statistics, 2012. CA Cancer J Clin. 2012;62:220–41. doi: 10.3322/caac.21149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Thigpen T, duBois A, McAlpine J, DiSaia P, Fujiwara K, Hoskins W, Kristensen G, Mannel R, Markman M, Pfisterer J, et al. Gynecologic Cancer InterGroup First-line therapy in ovarian cancer trials. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2011;21:756–62. doi: 10.1097/IGC.0b013e31821ce75d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ozols RF, Bundy BN, Greer BE, Fowler JM, Clarke-Pearson D, Burger RA, Mannel RS, DeGeest K, Hartenbach EM, Baergen R, Gynecologic Oncology Group Phase III trial of carboplatin and paclitaxel compared with cisplatin and paclitaxel in patients with optimally resected stage III ovarian cancer: a Gynecologic Oncology Group study. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:3194–200. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.02.153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vasey PA, Jayson GC, Gordon A, Gabra H, Coleman R, Atkinson R, Parkin D, Paul J, Hay A, Kaye SB, Scottish Gynaecological Cancer Trials Group Phase III randomized trial of docetaxel-carboplatin versus paclitaxel-carboplatin as first-line chemotherapy for ovarian carcinoma. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2004;96:1682–91. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djh323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Burger RA, Brady MF, Bookman MA, Fleming GF, Monk BJ, Huang H, Mannel RS, Homesley HD, Fowler J, Greer BE, et al. Gynecologic Oncology Group Incorporation of bevacizumab in the primary treatment of ovarian cancer. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:2473–83. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1104390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Perren TJ, Swart AM, Pfisterer J, Ledermann JA, Pujade-Lauraine E, Kristensen G, Carey MS, Beale P, Cervantes A, Kurzeder C, et al. ICON7 Investigators A phase 3 trial of bevacizumab in ovarian cancer. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:2484–96. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1103799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Colombo N, Peiretti M, Parma G, Lapresa M, Mancari R, Carinelli S, Sessa C, Castiglione M, ESMO Guidelines Working Group Newly diagnosed and relapsed epithelial ovarian carcinoma: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2010;21(Suppl 5):v23–30. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdq244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cristea M, Han E, Salmon L, Morgan RJ. Practical considerations in ovarian cancer chemotherapy. Ther Adv Med Oncol. 2010;2:175–87. doi: 10.1177/1758834010361333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Friedlander M, Trimble E, Tinker A, Alberts D, Avall-Lundqvist E, Brady M, Harter P, Pignata S, Pujade-Lauraine E, Sehouli J, et al. Gynecologic Cancer InterGroup Clinical trials in recurrent ovarian cancer. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2011;21:771–5. doi: 10.1097/IGC.0b013e31821bb8aa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pujade-Lauraine E, Wagner U, Aavall-Lundqvist E, Gebski V, Heywood M, Vasey PA, Volgger B, Vergote I, Pignata S, Ferrero A, et al. Pegylated liposomal Doxorubicin and Carboplatin compared with Paclitaxel and Carboplatin for patients with platinum-sensitive ovarian cancer in late relapse. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:3323–9. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.25.7519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Weber B, Lortholary A, Mayer F, Bourgeois H, Orfeuvre H, Combe M, Platini C, Cretin J, Fric D, Paraiso D, et al. Pegylated liposomal doxorubicin and carboplatin in late-relapsing ovarian cancer: a GINECO group phase II trial. Anticancer Res. 2009;29:4195–200. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ferrero JM, Weber B, Geay JF, Lepille D, Orfeuvre H, Combe M, Mayer F, Leduc B, Bourgeois H, Paraiso D, et al. Second-line chemotherapy with pegylated liposomal doxorubicin and carboplatin is highly effective in patients with advanced ovarian cancer in late relapse: a GINECO phase II trial. Ann Oncol. 2007;18:263–8. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdl376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gladieff L, Ferrero A, De Rauglaudre G, Brown C, Vasey P, Reinthaller A, Pujade-Lauraine E, Reed N, Lorusso D, Siena S, et al. Carboplatin and pegylated liposomal doxorubicin versus carboplatin and paclitaxel in partially platinum-sensitive ovarian cancer patients: results from a subset analysis of the CALYPSO phase III trial. Ann Oncol. 2012;23:1185–9. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdr441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Horowitz NS, Hua J, Gibb RK, Mutch DG, Herzog TJ. The role of topotecan for extending the platinum-free interval in recurrent ovarian cancer: an in vitro model. Gynecol Oncol. 2004;94:67–73. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2004.03.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kavanagh J, Tresukosol D, Edwards C, Freedman R, Gonzalez de Leon C, Fishman A, Mante R, Hord M, Kudelka A. Carboplatin reinduction after taxane in patients with platinum-refractory epithelial ovarian cancer. J Clin Oncol. 1995;13:1584–8. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1995.13.7.1584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pignata S, Lauraine EP, du Bois A, Pisano C. Pegylated liposomal doxorubicin combined with carboplatin: a rational treatment choice for advanced ovarian cancer. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2010;73:23–30. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2009.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Monk BJ, Herzog TJ, Kaye SB, Krasner CN, Vermorken JB, Muggia FM, Pujade-Lauraine E, Lisyanskaya AS, Makhson AN, Rolski J, et al. Trabectedin plus pegylated liposomal Doxorubicin in recurrent ovarian cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:3107–14. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.25.4037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Poveda A, Vergote I, Tjulandin S, Kong B, Roy M, Chan S, Filipczyk-Cisarz E, Hagberg H, Kaye SB, Colombo N, et al. Trabectedin plus pegylated liposomal doxorubicin in relapsed ovarian cancer: outcomes in the partially platinum-sensitive (platinum-free interval 6-12 months) subpopulation of OVA-301 phase III randomized trial. Ann Oncol. 2011;22:39–48. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdq352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mutch DG, Orlando M, Goss T, Teneriello MG, Gordon AN, McMeekin SD, Wang Y, Scribner DR, Jr., Marciniack M, Naumann RW, et al. Randomized phase III trial of gemcitabine compared with pegylated liposomal doxorubicin in patients with platinum-resistant ovarian cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:2811–8. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.09.6735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gordon AN, Tonda M, Sun S, Rackoff W, Doxil Study 30-49 Investigators Long-term survival advantage for women treated with pegylated liposomal doxorubicin compared with topotecan in a phase 3 randomized study of recurrent and refractory epithelial ovarian cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 2004;95:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2004.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kucukoner M, Isikdogan A, Yaman S, Gumusay O, Unal O, Ulas A, Elkiran ET, Kaplan MA, Ozdemir N, Inal A, et al. Oral etoposide for platinum-resistant and recurrent epithelial ovarian cancer: a study by the Anatolian Society of Medical Oncology. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2012;13:3973–6. doi: 10.7314/APJCP.2012.13.8.3973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lortholary A, Largillier R, Weber B, Gladieff L, Alexandre J, Durando X, Slama B, Dauba J, Paraiso D, Pujade-Lauraine E, GINECO group France Weekly paclitaxel as a single agent or in combination with carboplatin or weekly topotecan in patients with resistant ovarian cancer: the CARTAXHY randomized phase II trial from Groupe d’Investigateurs Nationaux pour l’Etude des Cancers Ovariens (GINECO) Ann Oncol. 2012;23:346–52. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdr149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chiyoda T, Tsuda H, Nomura H, Kataoka F, Tominaga E, Suzuki A, Susumu N, Aoki D. Effects of third-line chemotherapy for women with recurrent ovarian cancer who received platinum/taxane regimens as first-line chemotherapy. Eur J Gynaecol Oncol. 2010;31:364–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Seliger G, Mueller LP, Kegel T, Kantelhardt EJ, Grothey A, Groe R, Strauss HG, Koelbl H, Thomssen C, Schmoll HJ. Phase 2 trial of docetaxel, gemcitabine, and oxaliplatin combination chemotherapy in platinum- and paclitaxel-pretreated epithelial ovarian cancer. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2009;19:1446–53. doi: 10.1111/IGC.0b013e3181b62f38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bamias A, Bamia C, Zagouri F, Kostouros E, Kakoyianni K, Rodolakis A, Vlahos G, Haidopoulos D, Thomakos N, Antsaklis A, et al. Improved survival trends in platinum-resistant patients with advanced ovarian, fallopian or peritoneal cancer treated with first-line paclitaxel/platinum chemotherapy: the impact of novel agents. Oncology. 2013;84:158–65. doi: 10.1159/000341366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ferrandina G, Corrado G, Licameli A, Lorusso D, Fuoco G, Pisconti S, Scambia G. Pegylated liposomal doxorubicin in the management of ovarian cancer. 2010;6:463–83. doi: 10.2147/TCRM.S3348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ferrandina G, Ludovisi M, Lorusso D, Pignata S, Breda E, Savarese A, Del Medico P, Scaltriti L, Katsaros D, Priolo D, et al. Phase III trial of gemcitabine compared with pegylated liposomal doxorubicin in progressive or recurrent ovarian cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:890–6. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.13.6606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cannistra SA. Evaluating new regimens in recurrent ovarian cancer: how much evidence is good enough? J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:3101–3. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.29.7077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Muggia FM. Clinical efficacy and prospects for use of pegylated liposomal doxorubicin in the treatment of ovarian and breast cancers. Drugs. 1997;54(Suppl 4):22–9. doi: 10.2165/00003495-199700544-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Alberts DS, Garcia DJ. Safety aspects of pegylated liposomal doxorubicin in patients with cancer. Drugs. 1997;54(Suppl 4):30–5. doi: 10.2165/00003495-199700544-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Baumann KH, Wagner U, du Bois A. The changing landscape of therapeutic strategies for recurrent ovarian cancer. Future Oncol. 2012;8:1135–47. doi: 10.2217/fon.12.112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Staropoli N, Ciliberto D, Botta C, Fiorillo L, Gualtieri S, Salvino A, Tassone P, Tagliaferri P. A retrospective analysis of pegylated liposomal doxorubicin in ovarian cancer: do we still need it? J Ovarian Res. 2013;6:10. doi: 10.1186/1757-2215-6-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dear RF, Gao B, Harnett P. Recurrent ovarian cancer: treatment with pegylated liposomal doxorubicin; a Westmead Cancer Care Centre experience. Asia Pac J Clin Oncol. 2010;6:66–73. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-7563.2009.01263.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Vergote I, Finkler N, del Campo J, Lohr A, Hunter J, Matei D, Kavanagh J, Vermorken JB, Meng L, Jones M, et al. ASSIST-1 Study Group Phase 3 randomised study of canfosfamide (Telcyta, TLK286) versus pegylated liposomal doxorubicin or topotecan as third-line therapy in patients with platinum-refractory or -resistant ovarian cancer. Eur J Cancer. 2009;45:2324–32. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2009.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gordon AN, Fleagle JT, Guthrie D, Parkin DE, Gore ME, Lacave AJ. Recurrent epithelial ovarian carcinoma: a randomized phase III study of pegylated liposomal doxorubicin versus topotecan. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19:3312–22. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2001.19.14.3312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Markman M, Moon J, Wilczynski S, Lopez AM, Rowland KM, Jr., Michelin DP, Lanzotti VJ, Anderson GL, Alberts DS. Single agent carboplatin versus carboplatin plus pegylated liposomal doxorubicin in recurrent ovarian cancer: final survival results of a SWOG (S0200) phase 3 randomized trial. Gynecol Oncol. 2010;116:323–5. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2009.11.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sehouli J, Meier W, Wimberger P, Chekerov R, Belau A, Mahner S, Kurzeder C, Hilpert F, Klare P, Doerfel S, et al. Topotecan plus carboplatin versus standard therapy with paclitaxel plus carboplatin (PC) or gemcitabin plus carboplatin (GC) or carboplatin plus pegylated doxorubicin (PLDC): A randomized phase III trial of the NOGGO-AGO-Germany-AGO Austria and GEICO-GCIG intergroup study (HECTOR). ASCO Meeting Abstracts 2012; 30:5031. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pignata S, Scambia G, Ferrandina G, Savarese A, Sorio R, Breda E, Gebbia V, Musso P, Frigerio L, Del Medico P, et al. Carboplatin plus paclitaxel versus carboplatin plus pegylated liposomal doxorubicin as first-line treatment for patients with ovarian cancer: the MITO-2 randomized phase III trial. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:3628–35. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.33.8566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bookman MA, Brady MF, McGuire WP, Harper PG, Alberts DS, Friedlander M, Colombo N, Fowler JM, Argenta PA, De Geest K, et al. Evaluation of new platinum-based treatment regimens in advanced-stage ovarian cancer: a Phase III Trial of the Gynecologic Cancer Intergroup. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:1419–25. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.19.1684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kaye SB, Lubinski J, Matulonis U, Ang JE, Gourley C, Karlan BY, Amnon A, Bell-McGuinn KM, Chen LM, Friedlander M, et al. Phase II, open-label, randomized, multicenter study comparing the efficacy and safety of olaparib, a poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase inhibitor, and pegylated liposomal doxorubicin in patients with BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations and recurrent ovarian cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:372–9. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.36.9215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Vergote I, Finkler NJ, Hall JB, Melnyk O, Edwards RP, Jones M, Keck JG, Meng L, Brown GL, Rankin EM, et al. Randomized phase III study of canfosfamide in combination with pegylated liposomal doxorubicin compared with pegylated liposomal doxorubicin alone in platinum-resistant ovarian cancer. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2010;20:772–80. doi: 10.1111/IGC.0b013e3181daaf59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Alberts DS, Liu PY, Wilczynski SP, Clouser MC, Lopez AM, Michelin DP, Lanzotti VJ, Markman M, Southwest Oncology Group Randomized trial of pegylated liposomal doxorubicin (PLD) plus carboplatin versus carboplatin in platinum-sensitive (PS) patients with recurrent epithelial ovarian or peritoneal carcinoma after failure of initial platinum-based chemotherapy (Southwest Oncology Group Protocol S0200) Gynecol Oncol. 2008;108:90–4. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2007.08.075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bafaloukos D, Linardou H, Aravantinos G, Papadimitriou C, Bamias A, Fountzilas G, Kalofonos HP, Kosmidis P, Timotheadou E, Makatsoris T, et al. A randomized phase II study of carboplatin plus pegylated liposomal doxorubicin versus carboplatin plus paclitaxel in platinum sensitive ovarian cancer patients: a Hellenic Cooperative Oncology Group study. BMC Med. 2010;8:3. doi: 10.1186/1741-7015-8-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Colombo N, Kutarska E, Dimopoulos M, Bae DS, Rzepka-Gorska I, Bidzinski M, Scambia G, Engelholm SA, Joly F, Weber D, et al. Randomized, open-label, phase III study comparing patupilone (EPO906) with pegylated liposomal doxorubicin in platinum-refractory or -resistant patients with recurrent epithelial ovarian, primary fallopian tube, or primary peritoneal cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:3841–7. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.38.8082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pujade-Lauraine E, Hilpert F, Weber B, Reuss A, Poveda A, Kristensen G, Sorio R, Vergote IB, Witteveen P, Bamias A, et al. AURELIA: A randomized phase III trial evaluating bevacizumab (BEV) plus chemotherapy (CT) for platinum (PT)-resistant recurrent ovarian cancer (OC). ASCO Meeting Abstracts 2012; 30:LBA5002. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rose P, Edwards R, Finkler N, Seiden M, Duska L, Krasner C, Cappuccini F, Kolevska T, Brand E, Brown G, et al. Phase 3 Study: Canfosfamide (C, TLK286) plus carboplatin (P) vs liposomal doxorubicin (D) as 2nd line therapy of platinum (P) resistant ovarian cancer (OC). ASCO Meeting Abstracts 2007; 25:LBA5529. [Google Scholar]

- 48.O'Byrne KJ. A phase III study of Doxil/Caelyx versus paclitaxel in platinum-treated, taxane-naive relapsed ovarian cancer. Proc Am Soc Clin Oncol. 2002;21:203a. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Armijo-Olivo S, Stiles CR, Hagen NA, Biondo PD, Cummings GG. Assessment of study quality for systematic reviews: a comparison of the Cochrane Collaboration Risk of Bias Tool and the Effective Public Health Practice Project Quality Assessment Tool: methodological research. J Eval Clin Pract. 2012;18:12–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2753.2010.01516.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Detsky AS, Naylor CD, O’Rourke K, McGeer AJ, L’Abbé KA. Incorporating variations in the quality of individual randomized trials into metaanalysis. J Clin Epidemiol. 1992;45:255–65. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(92)90085-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lawrie TA, Rabbie R, Thoma C, Morrison J. Pegylated liposomal doxorubicin for first-line treatment of epithelial ovarian cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;10:CD010482. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD010482.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lawrie TA, Bryant A, Cameron A, Gray E, Morrison J. Pegylated liposomal doxorubicin for relapsed epithelial ovarian cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;7:CD006910. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006910.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Gibson JM, Alzghari S, Ahn C, Trantham H, La-Beck NM. The role of pegylated liposomal doxorubicin in ovarian cancer: a metaanalysis of randomized clinical trials. Oncologist. 2013;18:1022–31. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2013-0126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Mäenpää J. [First-line bevacizumab in ovarian cancer] Duodecim. 2011;127:2037–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Brundage M, Gropp M, Mefti F, Mann K, Lund B, Gebski V, Wolfram G, Reed N, Pignata S, Ferrero A, et al. Health-related quality of life in recurrent platinum-sensitive ovarian cancer--results from the CALYPSO trial. Ann Oncol. 2012;23:2020–7. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdr583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Parmar MK, Ledermann JA, Colombo N, du Bois A, Delaloye JF, Kristensen GB, Wheeler S, Swart AM, Qian W, Torri V, et al. ICON and AGO Collaborators Paclitaxel plus platinum-based chemotherapy versus conventional platinum-based chemotherapy in women with relapsed ovarian cancer: the ICON4/AGO-OVAR-2.2 trial. Lancet. 2003;361:2099–106. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)13718-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Aghajanian C, Blank SV, Goff BA, Judson PL, Teneriello MG, Husain A, Sovak MA, Yi J, Nycum LR. OCEANS: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase III trial of chemotherapy with or without bevacizumab in patients with platinum-sensitive recurrent epithelial ovarian, primary peritoneal, or fallopian tube cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:2039–45. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.42.0505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Monk BJ, Herzog TJ, Kaye SB, Krasner CN, Vermorken JB, Muggia FM, Pujade-Lauraine E, Park YC, Parekh TV, Poveda AM. Trabectedin plus pegylated liposomal doxorubicin (PLD) versus PLD in recurrent ovarian cancer: overall survival analysis. Eur J Cancer. 2012;48:2361–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2012.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Cannistra SA, Matulonis UA, Penson RT, Hambleton J, Dupont J, Mackey H, Douglas J, Burger RA, Armstrong D, Wenham R, et al. Phase II study of bevacizumab in patients with platinum-resistant ovarian cancer or peritoneal serous cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:5180–6. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.12.0782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ciliberto D, Botta C, Correale P, Rossi M, Caraglia M, Tassone P, Tagliaferri P. Role of gemcitabine-based combination therapy in the management of advanced pancreatic cancer: a metaanalysis of randomised trials. Eur J Cancer. 2013;49:593–603. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2012.08.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ciliberto D, Prati U, Roveda L, Barbieri V, Staropoli N, Abbruzzese A, Caraglia M, Di Maio M, Flotta D, Tassone P, et al. Role of systemic chemotherapy in the management of resected or resectable colorectal liver metastases: a systematic review and metaanalysis of randomized controlled trials. Oncol Rep. 2012;27:1849–56. doi: 10.3892/or.2012.1740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Stewart LA, Parmar MK, Tierney JF. Metaanalyses and large randomized, controlled trials. N Engl J Med. 1998;338:61–, author reply 61-2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Parmar MK, Torri V, Stewart L. Extracting summary statistics to perform metaanalyses of the published literature for survival endpoints. Stat Med. 1998;17:2815–34. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0258(19981230)17:24<2815::AID-SIM110>3.0.CO;2-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, Mulrow C, Gøtzsche PC, Ioannidis JP, Clarke M, Devereaux PJ, Kleijnen J, Moher D. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and metaanalyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. J Clin Epidemiol. 2009;62:e1–34. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2009.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Crowther M, Lim W, Crowther MA. Systematic review and metaanalysis methodology. Blood. 2010;116:3140–6. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-05-280883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Wang D, Mou ZY, Zhai JX, Zong HX, Zhao XD. [Application of Stata software to test heterogeneity in metaanalysis method] Zhonghua Liu Xing Bing Xue Za Zhi. 2008;29:726–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.DerSimonian R, Levine RJ. Resolving discrepancies between a metaanalysis and a subsequent large controlled trial. JAMA. 1999;282:664–70. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.7.664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.DerSimonian R, Kacker R. Random-effects model for metaanalysis of clinical trials: an update. Contemp Clin Trials. 2007;28:105–14. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2006.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Sterne JA, Sutton AJ, Ioannidis JP, Terrin N, Jones DR, Lau J, Carpenter J, Rücker G, Harbord RM, Schmid CH, et al. Recommendations for examining and interpreting funnel plot asymmetry in metaanalyses of randomised controlled trials. BMJ. 2011;343:d4002. doi: 10.1136/bmj.d4002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Boston RC, Sumner AE. STATA: a statistical analysis system for examining biomedical data. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2003;537:353–69. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4419-9019-8_23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]