Abstract

Theoretical considerations predict that balancer chromosomes in Drosophila melanogaster should accumulate numerous deleterious mutations with time. We counted the number of recessive lethal mutations on two balancer chromosomes from the In(2LR)SM1/In(2LR)Pm strain maintained in our lab, after making the balancers heterozygous with deficiencies from second-chromosome Kyoto Deficiency kit strains. We detected 10 recessive lethal mutations in the balancer In(2LR)Pm, which is consistent with the mutation rate estimated previously. However, we detected only three mutations, a significantly smaller number, in the balancer In(2LR)SM1, although this may be an artifact. In conclusion, we observed genetic decay over an estimable timescale by using balancers with historical records. Thus, balancers of any strain may have accumulated many unidentified recessive lethal mutations.

Keywords: inversion, mutation rate, recessive lethal, recombination, balancer chromosomes, Drosophila melanogaster

Introduction

Deleterious mutations accumulate in the genomes of asexually reproducing organisms, as their chromosomes do not undergo genetic recombination (Muller’s ratchet).1 Even in sexually reproducing organisms, deleterious mutations should accumulate in regions where recombination is suppressed. The degenerated Y chromosome is an extreme example of the evolutionary consequences of this phenomenon.2 Chromosomal inversions suppress recombination in regions where homologous chromosomes are not collinear.3 The multiple inversions present on the balancer chromosomes (balancers) of Drosophila melanogaster suppress recombination over most of their length.4,5 Moreover, balancers generally carry at least one dominant visible marker and are lethal in homozygotes, causing them to be maintained in a heterozygous state. Given that there is no selection against the retention of recessive, deleterious mutations in heterozygotes (but see Results and Discussion), it seems likely that balancers will accumulate many such mutations. Therefore, balancers provide a useful evolutionary model system for understanding the accumulation of deleterious mutations. Furthermore, quality control of balancers is necessary because Drosophila geneticists frequently use balancers to screen for new mutations or to track particular chromosomes during crossing experiments in the absence of recombination. Accordingly, it is worth examining the extent of “genetic decay” of balancers.

Results and Discussion

We crossed In(2LR)SM1/In(2LR)Pm females to males from each strain included in the second-chromosome Deficiency kit to detect recessive lethal mutations in the balancers.

At least 10 recessive lethal mutations were detected in In(2LR)Pm, whereas only three were detected in In(2LR)SM1 (Table 1, Table S1 and Fig. S1). The incidence of recessive lethal mutations on the second chromosome is estimated to be 0.0060–0.0062 per generation,6,7 which is equivalent to 0.156 mutations per year, assuming a 2-week generation time (transferred by a 2-week interval at 25 °C). Considering each inversion on a balancer that suppresses recombination, extrapolation of this mutation rate suggests that 10.6 and 10.2 recessive lethal mutations should be detected on In(2LR)Pm and In(2LR)SM1, respectively (Table S2). Assuming a Poisson distribution, the probability that In(2LR)Pm has 10 or fewer recessive lethal mutations is 0.508. Conversely, the probability that In(2LR)SM1 has three or fewer recessive lethal mutations is 0.009 (Table 1) If we assume that the In(2L)Cy + In(2R)Cy chromosome is not a good balancer and that recombination has been suppressed over the whole length of In(2LR)SM1 only after the other inversion was induced, 7.3 recessive lethal mutations should have been accumulated since 1953 on In(2LR)SM1. Even if this assumption is correct, the probability that In(2LR)SM1 has three or fewer recessive lethal mutations is 0.024. In summary, we detected a number of new recessive lethal mutations on In(2LR)Pm that is consistent with the previous estimate6,7 but not for In(2LR)SM1.

Table 1. Numbers of recessive lethal mutations.

| Balancer | Observed | Expected | Probability (≤ Observed) |

|---|---|---|---|

| In(2LR)Pm | 10 | 10.6 | 0.508 |

| In(2LR)SM1 | 3 | 10.2 | 0.009 |

Why are there so few recessive lethal mutations on In(2LR)SM1? The possibility remains that the value is an artifact. We may have not detected certain recessive lethal mutations because the deficiencies found in the second-chromosome Kyoto Deficiency kit strains do not completely cover the whole chromosome (ca. 94% coverage). Given that balancers derived from In(2L)Cy + In(2R)Cy [e.g., In(2LR)SM1, In(2LR)SM5 and In(2LR)O], which have usually been used to isolate mutations and deficiencies on the second chromosome, may have common recessive lethal mutations, the deficiency kit may not contain strains with such deficiencies on their chromosomes in addition to chromosomal regions associated with haploinsufficiency.

It should be noted here that recessive lethal mutations are often also deleterious in heterozygotes.8,9 If this is the case, recessive lethal mutations would accumulate more slowly than expected from the mutation rate when the population size is large enough. Here we did not observe such a slow rate of accumulation in In(2LR)Pm, which might be because the balancer strain has been kept as a very small population. Hence, balancers would decay at the upper bound rate with the usual methods of fly maintenance. It would be desirable to measure the dominance of accumulated lethal mutations on the balancers.

In summary, we observed genetic decay on an estimable timescale by using balancers with historical records. In keeping with our findings, balancers in any strain must, therefore, contain many unidentified, recessive lethal mutations. Furthermore, we predict that recessive lethal mutations accumulate to a greater extent on balancers than on other chromosomes. Because such recessive lethalities might be uncovered in certain genotypic classes that have inherited the balancers, we need to be aware that certain mutations or deficiencies may not be able to be isolated when using a particular balancer and that the segregation ratio may not be as expected for certain crossing experiments.

Materials and Methods

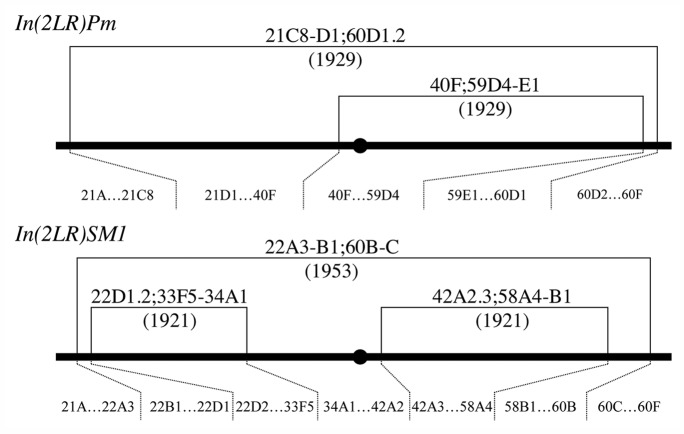

We employed the Drosophila melanogaster second-chromosome balancers In(2LR)Pm (FBab0004861) and In(2LR)SM1 (FBba0000037). The standard second chromosome consists of 240 cytological compartments, with divisions 21–40 on the left arm (2L), divisions 41–60 on the right arm (2R) and subdivisions A–F in each division.10 The balancer In(2LR)Pm, which carries the dominant visible marker Plum (= bwV1) (FBal0001401), was discovered by H.J. Muller in 1929.11,12 It has a nest of inversions extending over 236 compartments (40F;59D4-E1 in 21C8-D1;60D1.2), and we assume that In(2LR)Pm has been suppressing recombination over most of its length since it was discovered in 1929 (Fig. 1). The history of In(2LR)SM1 begins with the discovery of In(2L)Cy + In(2R)Cy carrying the dominant visible marker Curly (FBal0002196) in 1921.12,13 The chromosome contains two inversions: In(2L)Cy extends over 70 compartments (22D1.2;33F5–34A1), and In(2R)Cy extends over 97 compartments (42A2.3;58A4-B1) (Fig. 1). A large inversion extending over 229 compartments (22A3-B1;60B-C) was superimposed on In(2L)Cy + In(2R)Cy by Lewis and Mislove and reported in 1953,14 and the resultant balancer is designated In(2LR)SM1 (Fig. 1). We assume that In(2LR)SM1 has been suppressing recombination over most of its length since 1953.

Figure 1. The second-chromosome balancers examined in this study, indicating the cytology and history of In(2LR)Pm and In(2LR)SM1. The new orders are 21A…21C8|60D1…59E1|40F…59D4|40F…21D1|60D2…60F and 21…22A3|60B…58B1|42A3…58A4|42A2…34A1|22D2…33F5|22D1–22B1|60C…60F, for In(2LR)Pm and In(2LR)SM1, respectively. The black bar represents the second chromosome, and the black circle represents the centromere.

The balancers tested here are from the In(2LR)SM1/In(2LR)Pm strain (usually denoted Cy/Pm), which has been maintained in our laboratory for a long time and is believed to have been a gift of T. Mukai.15 Because multiple recessive lethal mutations may have segregated in the balancers in our maintained strain, we isolated the balancers and established a new strain. To do so, we first mated a single In(2LR)SM1/In(2LR)Pm female to a wild-type Oregon-R male. For the second generation, we mated a +/In(2LR)Pm female and an In(2LR)SM1/+ male, and for the third generation, we mated a female and a male containing In(2LR)SM1/In(2LR)Pm to re-establish the strain.

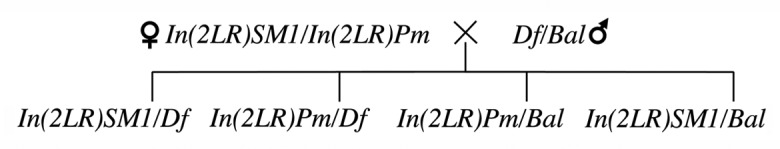

To detect recessive lethal mutations in the balancers, we crossed the In(2LR)SM1/In(2LR)Pm females to males from each strain included in the second-chromosome Kyoto Deficiency kit (www.dgrc.kit.ac.jp). The strains in this collection are generally heterozygous for both a deficiency (Df) and a balancer (Bal) (Table S3). Theoretically, four genotypic classes should appear in the crosses (Fig. 2). If Df/In(2LR)Pm or In(2LR)SM1/Df flies are not found, then a recessive lethal mutation should exist in the region rendered hemizygous by the deficiency.

Figure 2. Test to detect recessive lethal mutations on In(2LR)Pm and In(2LR)SM1.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the Drosophila Genetic Resource Center (Kyoto Institute of Technology, Japan) and the Bloomington Drosophila Stock Center (Indiana University, USA) for providing us with the fly strains. The In(2LR)SM1/In(2LR)Pm strain used here has been maintained in the laboratory of H. Kurokawa and Y. Oguma.

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material may be found here: www.landesbioscience.com/journals/fly/article/24466

References

- 1.Muller HJ. The relation of recombination to mutational advance. Mutat Res. 1964;106:2–9. doi: 10.1016/0027-5107(64)90047-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Charlesworth B, Charlesworth D. The degeneration of Y chromosomes. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2000;355:1563–72. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2000.0717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sturtevant AH. Inherited linkage variations in the second chromosome. Carnegie Inst Wash Publ. 1919;278:305–41. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Muller HJ. Genetic variability, twin hybrids and constant hybrids, in a case of balanced lethal factors. Genetics. 1918;3:422–99. doi: 10.1093/genetics/3.5.422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Altenburg E, Muller HJ. The genetic basis of truncate wing–an inconstant and modifiable character in Drosophila. Genetics. 1920;5:1–59. doi: 10.1093/genetics/5.1.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wallace B. Mutation rates for autosomal lethals in Drosophila melanogaster. Genetics. 1968;60:389–93. doi: 10.1093/genetics/60.2.389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mukai T, Chigusa SI, Mettler LE, Crow JF. Mutation rate and dominance of genes affecting viability in Drosophila melanogaster. Genetics. 1972;72:335–55. doi: 10.1093/genetics/72.2.335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mukai T, Yamaguchi O. The genetic structure of natural populations of Drosophila melanogaster. XI. Genetic variability in a local population. Genetics. 1974;76:339–66. doi: 10.1093/genetics/76.2.339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yoshikawa I, Mukai T. Heterozygous effects on viability of spontaneous lethal genes in Drosophila melanogaster. Jpn J Genet. 1976;45:443–55. doi: 10.1266/jjg.45.443. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bridges CB. Salivary chromosome maps with a key to the banding of the chromosomes of Drosophila melanogaster. J Hered. 1935;26:60–4. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Glass HB. A study of dominant mosaic eye-colour mutants in Drosophila melanogaster. II. Tests involving crossing-over and non-disjunction. J Genet. 1933;28:69–112. doi: 10.1007/BF02981769. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lindsley DL, Zimm GG. The Genome of Drosophila melanogaster. San Diego, CA: Academic Press, 1992:1-1133. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ward L. The genetics of curly wing in Drosophila. Another case of balanced lethal factors. Genetics. 1923;8:276–300. doi: 10.1093/genetics/8.3.276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lewis EB, Mislove FR. New mutants report. Drosoph Inf Serv. 1953;27:57–8. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mukai T. The genetic structure of natural populations of Drosophila melanogaster. I. Spontaneous mutation rate of polygenes controlling viability. Genetics. 1964;50:1–19. doi: 10.1093/genetics/50.1.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.