Abstract

The mammalian intestine must manage to contain 100 trillion intestinal bacteria without inducing inappropriate immune responses to these microorganisms. The effects of the immune system on intestinal microorganisms are numerous and well-characterized, and recent research has determined that the microbiota influences the intestinal immune system as well. In this review, we first discuss the intestinal immune system and its role in containing and maintaining tolerance to commensal organisms. We next introduce a category of immune cells, the innate lymphoid cells, and describe their classification and function in intestinal immunology. Finally, we discuss the effects of the intestinal microbiota on innate lymphoid cells.

Keywords: microbiota, intestinal immunity, Bacteroides fragilis, polysaccharide A, innate lymphoid cell, lymphoid tissue inducer cell

Introduction

The mammalian gastrointestinal tract is home to 100 trillion bacteria (the microbiota),1,2 and the amount of genetic material contained by the microbiota (the microbiome) is perhaps 100 times the total amount of host genetic material.3 A growing body of evidence is establishing the key role of the mammalian gut flora in both health and disease.2 The commensal flora plays a critical role in normal functioning of the host. Germ-free (GF) animals have deficits in systems ranging from digestion and metabolism4 to angiogenesis5 to cognitive development.6 In humans, the microbiome differs substantially in health and disease,7,8 and effects exerted by the microbiota are associated with obesity,9-14 colon cancer,15-17 asthma,18,19 inflammatory bowel disease (IBD),7,20,21 and cardiovascular disease.22,23 We are beginning to understand in greater detail the mechanisms behind and significance of these differences. Early studies of the gut flora primarily used crude comparisons of GF and conventional specific pathogen–free (SPF) animals; however, we now know that host–bacterial interactions are highly specific24 and that in many cases particular organisms, rather than the general bacterial load, are responsible for normal host development in a given mammalian species.25-30

One aspect of host-microbial interactions that has attracted particular interest pertains to the immune system, especially the intestinal immune system, which interacts most directly with the microbiota.2,31 This review will first discuss the intestinal immune system and the role of the intestinal immune system in containing and defending against intestinal bacteria, with special emphasis on innate lymphoid cells (ILCs). We will then discuss the effects the microbiota has on the immune system in general and ILCs in particular. Unlike previous reviews on this topic, which have mostly focused on ILC classification and function in health and disease, this review will focus on the molecular mechanisms by which the microbiota influences ILCs and vice versa, and will attempt to address some of the controversies in the field and areas where the published data appear to conflict.

Intestinal Immunity

Background

The intestine has the dual function of nutrient absorption and protection against potential pathogens. These two tasks have conflicting demands. Optimal absorption requires a large surface area and selective permeability to nutrients through a thin epithelial layer. However, a large surface area increases exposure to luminal bacteria, and the thinness of the epithelium increases the possibility of bacterial invasion. Thus, the intestinal immune system must be robust enough to defend a one-cell-thick epithelial layer. At the same time, it must not initiate inappropriate immune responses to the commensal bacteria that reside in the intestinal lumen, as these responses may result in inflammatory diseases such as IBD.31,32 Accordingly, it is important for the intestinal immune system to maintain an appropriate balance of pro- and anti-inflammatory factors.33

The intestinal immune system consists of highly organized structures—namely Peyer’s patches (PPs), mesenteric lymph nodes (MLNs), and isolated lymphoid follicles (ILFs)—that are associated with the lamina propria and epithelial cells of the intestine.34 PPs are secondary lymphoid organs (SLOs) of the intestine that facilitate the sampling of luminal antigens. Murine PPs consist of B cell follicles surrounding a T cell zone.35 These follicles are surrounded by a subepithelial dome, which is in turn surrounded by a follicle-associated epithelium that is exposed to the intestinal lumen.35 PPs differ from peripheral lymph nodes in that they are not fed by afferent lymph vessels;36 instead, the follicle-associated epithelium consists of a large number of M cells, specialized epithelial cells that transcytose macromolecules and microorganisms into the subepithelial dome.37-39 This transcytosis allows antigen-presenting cells (APCs) in the subepithelial dome to sample antigens from the bacteria that are most proximal to the epithelium.38 The APCs next can either present these antigens to T cells locally within the PP or migrate to the MLNs and present the antigens there.40,41 The T cells can then be activated, as can B cells through partially T cell-independent mechanisms.42 While these PP- and MLN-activated lymphocytes do enter the bloodstream through the thoracic duct,43,44 both T45 and B43 cells then return to the intestinal lamina propria, and this return to the gut may limit systemic inflammation.46,47 APCs also play an important role in balancing activation and tolerance: some APC populations primarily produce proinflammatory cytokines, while others have a more regulatory role.40,48-51

B cell activation in the PPs and MLNs helps the host contain the microbiota. Activated B cells differentiate and produce secretory immunoglobulin (Ig) A, which is the main intraluminal antibody. IgA helps control the growth of the intestinal bacteria and prevents microbial adhesion to epithelial cells,42,52 but acts primarily locally and does not induce systemic inflammation.53 IgA is produced in the PPs and MLNs, as previously discussed. The other major source of intestinal IgA is the ILF.54 ILFs consist of large groups of B cells in addition to other, smaller cell populations such as dendritic cells (DCs) and lymphoid tissue inducer (LTi) cells (to be discussed in greater detail below).34 The B cells in ILFs primarily generate IgA not through T cell co-activation, but rather through a T cell–independent mechanism involving lymphotoxin (LT) signaling and LTi cell–stromal cell interactions.54,55

Innate lymphoid cells

The ILC is a component of the intestinal immune system that has recently attracted tremendous attention. ILCs are a diverse class of immune cells defined by three criteria: lymphoid morphology on microscopy; absence of recombination-associated, gene-mediated antigen receptors (i.e., T and B cell receptors); and absence of myeloid and DC markers.56 ILCs play an important role in the innate immune system through cytokine production and other miscellaneous functions.57,58 The ILC nomenclature has recently been standardized, with classification of the cells into three groups based on cytokine production profile.56 We will focus primarily on group 3 ILCs, which have the best-characterized role in intestinal immunity, but will briefly discuss the other groups as well (Table 1).

Table 1. Categories and functions of innate lymphoid cells.

| Cell type | Tissues | Activated by | Primary mediators | Function and disease associations | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NK cell | SLO Blood |

IL-12 IL-18 NCRs |

IFN-γ Perforin Granzymes Fas ligand |

Tumor immunity Antiviral immunity Systemic inflammation |

64–69 |

| ILC1 | Intestine | IFN-γ | Colitis | 59, 61 | |

| ILC2 | Airway/lung Intestine Mesentery |

IL-25 IL-33 |

IL-5 IL-13 Amphiregulin |

Airway hypersensitivity Postinfection homeostasis Antihelminth immunity |

73–78, 80 |

| LTi cell | SLO Intestine |

IL-1β IL-7 IL-23 AHR |

IL-17 IL-22 LT CD30L OX40L |

Colitis Intestinal infection SLO development T cell maintenance |

95–96, 99, 110–112 |

| NCR+ ILC3 | Intestine | IL-22 | Colitis Intestinal infection |

83, 96, 99 | |

| NCR− ILC3 | Intestine | IL-17 IL-22 IFN-γ |

Colitis Postinflammatory colon cancer |

81, 100 |

Abbreviations: AHR, aryl hydrogen receptor; IFN, interferon; IL, interleukin; ILC, innate lymphoid cell; LT, lymphotoxin; LTi, lymphoid tissue inducer; NCR, natural cytotoxicity receptor; SLO, secondary lymphoid organ. Note: This table is not intended to be exhaustive. Shown are the major categories of ILCs along with their locations in the body, the molecules that induce cytokine production, the mediators (cytokines and others) primarily responsible for their immune effects, and their known functions and roles in disease.

Group 1 ILCs are analogous to T-helper (Th) 1 cells in that they produce interferon (IFN)-γ but not other cytokines associated with Th17 cells, such as interleukin (IL)-17 or IL-22.56,58 Group 1 ILCs express the transcription factor T-bet59,60 and respond to the cytokines IL-12 and IL-18.59,61-63 The prototypical group 1 ILC is the natural killer (NK) cell, which is the best-characterized of all ILCs.64,65 NK cells are named for their cytotoxic effects on virus-infected cells66,67 and tumor cells;68-70 these effects are mediated through mechanisms involving perforin, granzymes, and the Fas ligand.64,65 During specific stages of development,65 NK cells also produce IFN-γ in the setting of systemic inflammation71 and after activation of the natural cytotoxicity receptors (NCRs) NKp46 (found in mice and humans) and NKp44 (humans).72 In addition to NK cells, group 1 ILCs include a class of cells called ILC1s56 that accumulate in the intestine during colitis in mice and humans and are a major source of innate IFN-γ under such conditions.59,61 Group 2 ILCs (ILC2s) are defined as cells that produce Th2-associated cytokines.56 They express the transcription factor GATA3,73,74 respond to IL-25 and IL-33,73-78 and are found in the lungs,73,75 gut,75,76 and adipose tissue.74 ILC2s protect against helminthic infection74,76 and also play an important role in the airways79 by driving airway hypersensitivity induced by influenza virus,78 ovalbumin, and dust mites77 through IL-5 and IL-13.77,78 In addition, ILC2s are critical for tissue healing and for restoration of lung and airway homeostasis after infection with influenza virus.80

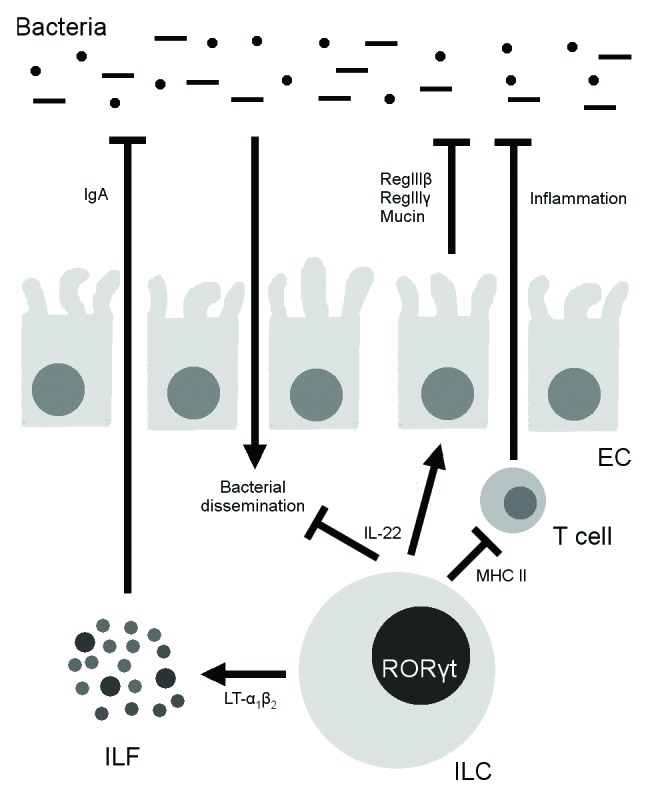

Group 3 ILCs are characterized by production of the Th17 cytokines IL-17 and IL-22, though they may also produce other cytokines, such as IFN-γ.56,81 Like Th17 cells, group 3 ILCs produce cytokines in response to IL-1β and IL-2382,83 and express varying levels of the transcription factor retinoic acid–related orphan receptor (ROR) γt and, sometimes, T-bet.84-86 IL-17 and IL-22 are both important regulators of intestinal and systemic immunity. IL-17 is typically proinflammatory and stimulates neutrophil homing, granulocyte and macrophage growth and differentiation, and acute-phase reactant production.87 This cytokine usually exacerbates inflammatory diseases88 but confers protection against fungal and certain bacterial infections.89-91 IL-22, in contrast, promotes tissue healing by inhibiting apoptosis, increasing cell cycle progression, and inducing mitogenic factor production.87,92 IL-22 also induces epithelial cells to produce the antimicrobial peptides RegIIIβ and RegIIIγ93 as well as mucin;94 these products kill microbes and maintain the barrier between host and bacteria (Fig. 1). While IL-22 generally protects against infectious95,96 and inflammatory97 diseases, it also drives colon cancer under certain circumstances.98

Figure 1. Effects of RORγt+ innate lymphoid cells (ILCs) on the microbiota. ILCs kill and inhibit bacteria by producing interleukin 22 (IL-22), with subsequent downstream effects on epithelial cells (ECs). In addition, they induce the formation of isolated lymphoid follicles (ILFs) through the induction of lymphotoxin α1β2 (LT-α1β2) and subsequent IgA production and bacterial suppression. Finally, ILCs signal to CD4+ T cells through major histocompatibility complex class II (MHCII) and suppress T cell responses to the microbiota.

IL-22 is responsible for many of the effects of group 3 ILCs in health and disease. Through IL-22, ILCs mediate experimental colitis,99 drive inflammatory colon cancer,100 and protect against infection by the intestinal pathogens Citrobacter rodentium95 and Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium.82 Group 3 ILCs are important not only in the setting of infection or inflammation but also in the steady-state, in which they contain luminal bacteria through IL-22-dependent mechanisms.101 In the absence of ILCs, there is greater dissemination of bacteria (especially Alcaligenes species) to the spleen and liver, with resultant systemic inflammation and elevated serum cytokine levels (Fig. 1). Of note, even in mice with T and B cells, ILCs are necessary for containing these bacteria. ILC-produced IL-17 is also physiologically important in defense against fungal infection89 and may drive certain models of colitis.81 In addition to exerting cytokine-dependent effects, group 3 ILCs modulate intestinal immunity through major histocompatibility complex class II (MHC II)–mediated antigen presentation to CD4+ T cells (Fig. 1).102 Such antigen presentation does not cause T cell proliferation, but rather induces T cell tolerance to commensal bacteria; mice lacking MHC II expression in ILCs develop spontaneous colitis.102

The best-characterized group 3 ILC is the LTi cell. LTi cells are named and best known for their role in the generation of SLOs, such as lymph nodes and the white pulp of the spleen, during embryogenesis.103 During fetal development, LTi cells migrate to nascent SLOs, where stromal cells activate them through IL-7 and the tumor necrosis factor (TNF)–related activation-induced cytokine (TRANCE), inducing them to express LT-α1β2.104,105 LT-α1β2 signals to the LT-β receptor on stromal cells, which causes stromal cells to express the homing molecules CC-chemokine ligand 19, CC-chemokine ligand 21, and CXC-chemokine ligand 13;106 these ligands recruit T cells, B cells, and APCs into spatially distinct T zones and follicles.107 PP development is similar, except that IL-7 plays a larger role in this process than in lymphoid development105 and DCs rather than stromal cells activate LT production and are themselves an important source of LT.108 LTi cells also signal through LT to induce the maturation of intestinal cryptopatches into ILFs, which are a source of subsequent secretory IgA production as previously discussed (Fig. 1).53,54,109 In addition to these roles in induction, LTi cells residing in the SLOs of adult mice co-stimulate T cells through CD30L and OX40L.110 This co-stimulation is required for activated T cell survival111,112 and maintenance of T cell memory against pathogens.113 Finally, like other group 3 ILCs, both splenic114 and intestinal85 LTi cells produce IL-17 and IL-22.

In addition to LTi cells, there are other group 3 ILCs that are collectively known as ILC3s.56 One subset expresses RORγt and the NCRs NKp46 (in mice and humans) and NKp44 (in humans only) and produces large amounts of IL-2283,96,115 but little or no IL-17.96,115 Another NCR− group produces IL-17, IL-22, and IFN-γ.81 Interestingly, one paper has identified a common gamma chain–independent response in a subset of splenic ILCs in which these cells produce IL-17 and IL-22 in response to flagellin and lipopolysaccharide.116 While human ILCs are less well understood than their murine counterparts, it is known that human group 3 ILC subsets can produce IL-22 alone or both IL-17 and IL-22.117-120

The developmental relationship between these different ILC populations is unclear. There is certainly some plasticity between different types of ILCs in humans. Human NCR+ and NCR− group 3 ILCs can differentiate into ILC1s.61 In addition, human LTi cells can differentiate into NKp44+ and NKp46+ ILC3s both in vitro when cultured with stromal “feeder” cells, IL-7, and IL-15 and in vivo when injected into lymphocyte-deficient mice.121118 Interestingly, the same is not the case in mice: Eberl and colleagues found that, under similar in vitro conditions, neither adult nor embryonic LTi cells differentiate into ILC3s.85 Investigation to clarify the lineage relationships of the different types of ILCs in different species is ongoing.

Effects of Gut Flora on Innate Lymphoid Cells

Background

We have discussed how the intestinal immune system influences and contains intestinal bacteria. However, host-microbial interactions are two-way, and the microbiota affects the host immune system as well. We will now consider some general principles regarding microbial effects on the host and will then describe the details of these effects on ILCs.

In addition to nonimmunologic deficits,31 GF mice have abnormal intestinal immunity, with smaller PPs, fewer IgA-secreting B cells and CD8+ intraepithelial lymphocytes, and decreased production of antimicrobial peptides.27 Systemically, GF mice have a pronounced Th2 skew: a greater proportion of CD4+ T cells produce Th2 cytokines such as IL-4 in GF mice than in conventional mice.27 Most of these immunologic changes are rapidly reversible upon introduction of a normal mouse microbiota.26,122 Interestingly, though, some of the effects of the intestinal flora are programmed very early after birth and persist even when the flora is altered later in life; this point is best illustrated by NKT cell migration to the colon.123

There appears to be considerable specificity in host–microbial interactions, as our lab recently showed while investigating the effects of intestinal colonization with a mouse microbiota or a human microbiota on murine intestinal immunity.24 The microbiotas were similar at the phylum level (the Bacteroidetes and Firmicutes dominated in both), but diverged at the genus level in the Firmicutes and at the operational taxonomic unit level in the Bacteroidetes. These differences in the microbiota resulted in drastically different immune phenotypes. The mouse microbiota nearly restored intestinal T cell numbers and fully restored T cell proliferation to SPF levels. However, the human microbiome did not change either T cell numbers or proliferation relative to GF status. Interestingly, these effects were limited to gut-associated compartments: splenic T cell numbers were identical in all groups.

Given that genus- and species-level differences in the microbiota can result in radically different immunologic phenotypes, it will be important to identify specific organisms and groups of organisms that drive these differences. One such organism is Bacteroides fragilis. While in the clinical setting B. fragilis is often found in infections, most notably abdominal abscesses,124,125 it is also a member of the normal human microbiota.126 Its effects on the immune system are primarily attributable to polysaccharide A (PSA), one of its eight capsular polysaccharides.32,126 Capsular polysaccharides in general are important for normal bacterial growth and have attracted a great deal of attention as potential vaccine targets.127-131 PSA in particular is necessary for B. fragilis colonization of its intestinal “niche,”132 though other bacterial products may also be necessary for this process.133 In addition, PSA, either purified and orally gavaged or produced by intestinal bacteria, regulates the systemic murine Th1/Th2 balance27 and induces the development of IL-10-producing forkhead box P3+ (Foxp3+) regulatory T cells (Tregs).28 The effects of this IL-10 production are not apparent in the steady-state,134 but in the setting of inflammation, IL-10 confers protection against murine colitis28 and experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis.135,136 PSA is recognized by host TLR2132,134 (unpublished data) and, after endosomal processing, can bind to MHC II.131 Another bacterium that drives immune development is the segmented filamentous bacterium (SFB), which is critical for the development of Th17 cells26 and the pathogenesis of Th17-associated diseases in the gut137 and other tissues.88,138,139 Finally, as another mechanism by which molecules produced by the commensal flora may influence the intestinal immune system, short-chain fatty acids upregulate Treg numbers and IL-10 production in the colon but, interestingly, not the small intestine, spleen, MLN, or thymus.140 A major mediator of this process is G-protein coupled receptor 43, which recognizes acetate and propionate141 and inhibits histone deacetylases.140

In addition to these instances in which a single organism drives immune maturation, there are other examples in which groups of bacteria are required for a similar effect. Specific Clostridium species are required for Treg development.25 Clostridia are the most numerous gram-positive spore-forming organisms in the intestine142 and constitute 10–40% of the normal microbiota, even though certain species, such as C. perfringens and C. difficile, can cause disease.143 Honda and colleagues identified a collection of 46 Clostridium strains native to the murine intestine144 whose introduction into GF mice increased by more than 3-fold (relative to the results in untreated GF mice) the number and proportion of CD4+ cells in the colon, liver, lung, and spleen25 that produce IL-10, a cytokine critical for protection against colitis.145-147 The introduction of these 46 clostridial strains even into SPF mice resulted in decreased susceptibility to dextran sodium sulfate colitis (a Th1 and Th17 cytokine-driven colitis in the disease stage investigated148) and oxazolone colitis (Th2 cytokine-driven149,150).25 This group later rationally selected a group of 17 human Clostridium strains that also induced IL-10-producing Foxp3+ Tregs and protected against 2,4,6-trinitrobenzenesulfonic acid (TNBS)-induced colitis and ovalbumin-induced diarrhea.151 Of note, it appears that a certain number of strains are required. Cocktails of three murine strains led to a much smaller effect than did the combined 46 strains.25 Monocolonization with any one of the 17 human clostridial species failed to induce Tregs relative to GF status, and colonization with a mix of three or five of these species did not induce as many Tregs as the full 17-species cocktail did.151

As has been discussed, specificity in host–microbial interactions is driven by genus- or even species-level differences.24 However, an important question arises: what is the molecular mechanism of this specificity? There are several possibilities. Microbial pattern recognition receptors that are characteristic of the innate immune system are not generally considered specific enough to recognize such differences.152 However, the aryl hydrogen receptor (AHR), which recognizes various natural products including those from bacterial tryptophan metabolism, offers a counter-example: when AHR is activated by one particular ligand, it induces Treg development, whereas AHR activation by a different ligand induces Th17 cell development.153 Another potential source of specificity is T cell receptor (TCR) recognition of bacterial antigens. The substantial differences between TCRs of colonic Tregs and those of thymic-derived natural Tregs suggest that differentiation of naïve T cells into Tregs may be driven by local antigens, and intestinal Treg TCRs do, in fact, recognize bacterial antigens.154 Interestingly, recognition of bacterial antigens by these same TCRs on naïve T cells preferentially induces these T cells to differentiate into Tregs rather than effector cells.154 Perhaps under certain circumstances bacteria can induce naïve T cells to differentiate into other T cell subsets as well.

A final possibility relates to the proximity of bacteria to host tissues. Some bacterial species, for a variety of organism-specific reasons, form closer associations with the host than others, and this greater proximity may cause greater exposure to bacterial products, recognition of bacterial antigens, or activation of host danger-associated pattern receptors.155 It is certainly plausible that bacteria in the center of the intestinal lumen have less influence on intestinal immunity than those in close proximity to epithelial cells. Interestingly, the bacteria that are most physically associated with intestinal crypts are surprisingly similar in the murine colon and the invertebrate midgut and are far more similar between species than the total microbiota, which suggests that this core group of closely associated organisms co-evolves with its hosts.156 There is no direct evidence for this proximity hypothesis, since it is not yet possible to control the spatial organization of the gut flora without modifying other factors. Nevertheless, notable bacteria that influence host immune development, such as SFB26 and clostridial species,25 appear on electron microscopy to have direct contact with epithelial cells. B. fragilis PSA–induced immunomodulation may also be location-specific. In B. fragilis–monocolonized mice, a small proportion of all B. fragilis organisms are in close proximity to colonic epithelial cells. However, in mice monocolonized with PSA-deficient bacteria, this population of tissue-associated organisms is far smaller; it increases to normal levels with oral administration of PSA.132 Depletion of Foxp3+ Tregs decreases the size of this tissue-associated population, while IL-17 blockade increases it. These findings imply that IL-17 would normally hinder B. fragilis association with the colon and that PSA induces Foxp3+ Tregs that downregulate IL-17 production and enhance this association. As a final example, mice deficient in the nucleotide oligomerization domain–containing (NOD)-like receptor P6 are susceptible to dextran sodium sulfate colitis, and this susceptibility is transmissible to wild-type (WT) mice through the gut flora.152 This colitis susceptibility phenotype is associated with greater frequency of Prevotellaceae and association of these organisms in intestinal crypts.152 Clearly, further investigation—perhaps including the development of new tools—will be necessary to better establish the extent to which and the mechanisms by which intestinal geography influences immunologic phenotype,155 but this proximity hypothesis shows promise as one explanation for the specificity of host-bacterial interactions.

In humans, too, there are associations between gut flora and intestinal immunity, though the direction of causality is much more difficult to establish in humans than in mice. The prototypical disease that illustrates this association is IBD, which comprises the subsets of Crohn disease and ulcerative colitis and is believed to arise from breakdown of immune tolerance to the microbiota.143,157-159 Humans with IBD have polymorphisms in genes associated with the immune system160 as well as intestinal microbiomes that differ markedly from those of healthy controls.7 For instance, enteroadhesive Escherichia coli colonizes a greater proportion of Crohn patients than of healthy controls,20 and Faecalibacterium prausnitzii, a human commensal that produces anti-inflammatory effects in murine colitis models, is associated with a lower risk of recurrence in Crohn.21 Given these associations, treatments directed at the microbiota may be useful in IBD patients. A recent meta-analysis has found that some antibiotics slightly decrease the likelihood and shorten the duration of IBD relapses.161 Conversely, the VSL#3 probiotic, which consists of defined cultures of four Lactobacillus, three Bifidobacterium, and one Streptococcus species, moderately increases the chance of establishing remission and decreases the risk of relapse in ulcerative colitis.162,163 Overall, these findings suggest that the microbiota regulates inflammation in human IBD. However, the significance of its role and the therapeutic value of targeting it remain unclear.

ILC numbers and cytokines

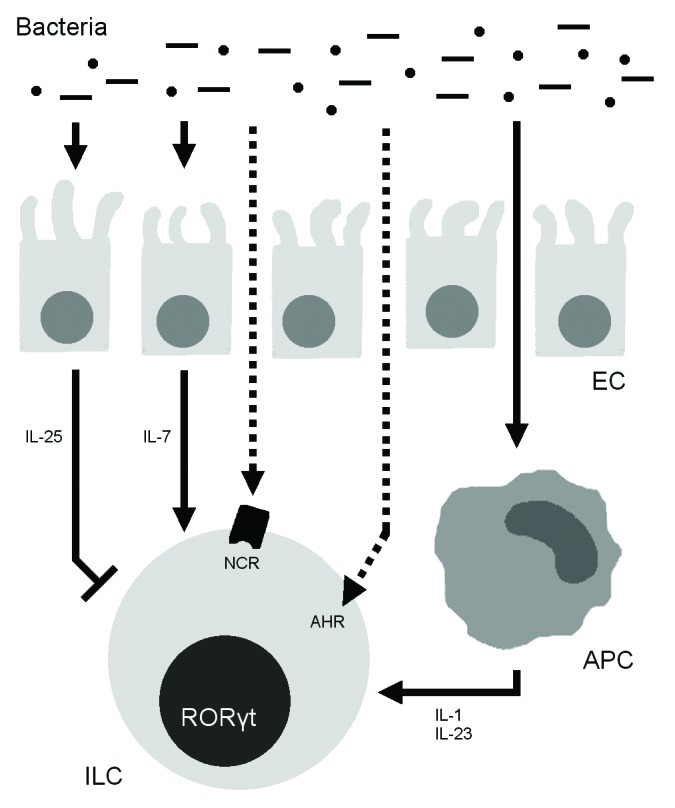

Having introduced some general principles regarding the effects of the gut flora on the immune system, we will now discuss the numerous effects that intestinal bacteria have on ILCs, starting with the role of these organisms in determining ILC numbers and cytokine production (Fig. 2). We will focus on group 3 ILCs, but clearly the microbiota can influence other cells as well. For instance, human NK cells express the microbial pattern receptors Toll-like receptor (TLR) 2,164 TLR3, and TLR9,165 and human group 3 ILCs express TLR2,117 so both cell types may directly recognize bacterial components. (Murine ILCs do not appear to express TLRs.166) Furthermore, commensal bacteria induce host epithelial cells and APCs to produce cytokines such as IL-6, IL-7, IL-12, IL-15, type 1 IFNs, and TNF-α, and this microbe-driven effect is required for full NK cell activation.167,168 The effects of commensal organisms on ILC2s have yet to be directly verified.

Figure 2. Effects of the microbiota on RORγt+ innate lymphoid cells (ILCs). Intestinal bacteria stimulate ILCs through antigen-presenting cell (APC)–produced interleukin 1β (IL-1β) and IL-23 and epithelial cell (EC)–produced IL-7 and also inhibit ILCs through EC-produced IL-25. Intestinal bacteria may also directly induce ILC activity through the aryl hydrogen receptor (AHR) and natural cytotoxicity receptors (NCRs).

Two early studies found that GF mice had very few RORγt+ small-intestinal group 3 ILCs and that these cells produced little IL-22.96,115 ILC numbers could be fully restored by colonization of GF mice with an SPF intestinal flora within 15 d.115 In addition, when RORγt+ NKp46+ ILC3s from SPF mice were cultured with IL-23, the percentage of cells producing IL-22 increased dramatically from around 15% to 35%.115 However, very few ILC3s from GF mice produced IL-22 even at baseline (< 5%), and the percentage of IL-22+ cells did not increase following IL-23 stimulation. Consistent with those findings, epithelial cells from GF mice produced very low levels of Reg3b and Reg3g transcripts, which encode for RegIIIβ and RegIIIγ, two antimicrobial peptides produced by epithelial cells in response to IL-22 signaling.93 Recolonization of adult GF mice with a conventional flora normalized expression of these peptides within 1–2 wk.115 Together, these two studies demonstrate that the intestinal microbiota is necessary for the development of RORγt+ ILC3s and stimulates IL-22 production by these cells.

Other investigators, however, have found no differences in ILC numbers in mice with different microbiotas. Eberl and colleagues investigated this question using a “fate-map” mouse model—with which the progeny of a cell type can be tracked throughout life—to follow the fetal precursors of RORγt+ ILCs.85 When the investigators treated mice with streptomycin, ampicillin, and colistin starting from day 7 after birth, there was no change in the composition of any RORγt+ group 3 ILC classes. Furthermore, the proportions of the different RORγt+ subsets among all RORγt+ cells were similar in GF and SPF mice.85 Another paper from the same group described the investigation of cell numbers, rather than proportions, in GF mice and SPF mice and found no differences in numbers of RORγt+ CD4+ LTi cells or RORγt+ NCR+ ILC3s in GF and SPF mice or after antibiotic treatment starting from one day before birth.99 A separate study found that the proportion of NCR+ ILCs among RORγt+ ILCs was identical in SPF and GF mice.83

Perhaps the discrepancies in these findings have to do with how cells were quantified. That there are fewer RORγt+ ILCs may mean either that there are fewer ILCs or that fewer ILCs express RORγt, and the microbiota could theoretically affect either or both of these variables. Diefenbach and colleagues readdressed this question, using fate-map mice in which any descendant of RORγt+ precursors—even if it had subsequently lost RORγt expression—could be identified.121 The researchers found that the microbiota’s effect on RORγt+ cell numbers reflected less RORγt expression rather than lower cell numbers: GF and SPF fate-map mice had similar numbers of LTi cells and NCR+ ILC3s, but RORγt expression was lower in the GF mice. A major mechanism behind this effect was microbial stabilization of RORγt expression through the induction of host cell production of IL-7,121 which drives development of group 3 ILCs.169,170 Antibiotic treatment decreased both the number of intestinal Il7 transcripts and RORγt expression in ILCs, and IL-7R−/− mice had decreased numbers of LTi cells and NCR+ ILC3s.121 Together these results suggest that the microbiota influences not ILC development, but rather RORγt expression, through IL-7 signaling (Fig. 2).

Gut flora-induced differences in T-bet expression constitute a mechanism by which the gut flora may influence ILC numbers.86 In mice, CCR6+ RORγt+ ILCs develop largely before birth (i.e., before bacterial colonization of the intestine), do not express the Th1-associated transcription factor T-bet, do not express NKp46, and produce IL-17A, IL-17F, and IL-22 independent of T-bet; this population is most similar to the traditional fetal LTi cell population. In contrast, CCR6− RORγt+ ILCs develop and proliferate mostly after birth (i.e., after bacterial colonization). At birth, these cells are essentially all T-bet−, but around two weeks of age, a population of CCR6− T-bet+ RORγt+ cells develops from T-bet− progenitors. Intestinal microbiota and IL-23 both induce T-bet expression, which in turn increases NKp46 expression and IFN-γ production. That is, the number of CCR6+ RORγt+ cells depends on the intestinal microbiota. This provides another mechanism by which the microbiota may influence group 3 ILC numbers. However, the molecular mediators responsible T-bet induction by the microbiota remain to be identified.

ILC3s express NCRs, which can be directly activated by specific microbial products such as influenza virus hemagglutinin171 and cell surface antigens of Mycoplasma-infected cells and represent another mechanism by which the microbiota may influence ILCs.172,173 NCRs, which in conventional NK cells cause cytotoxic granule release and IFN-γ production,72 also appear to upregulate ILC function. One recent paper investigating human ILCs found that NKp44 signaling influences RORγt+ ILC signaling through a mechanism synergistic with that mediated by cytokines.174 The authors found that NKp44 activation alone caused ILCs to produce TNF but not IL-22, while IL-1, IL-7, and IL-23 preferentially induced IL-22 but not TNF. However, activating NKp44 antibodies and IL-1, IL-7, and IL-23 synergized to induce large amounts of TNF and IL-22 secretion. An earlier paper found that even in the absence of NKp46 murine ILCs produce IL-22;175 however, the earlier paper did not investigate the effects of NKp46 activation on ILCs and does not conflict with the above paper on human ILCs.

Finally, there are other speculative mechanisms by which the microbiota may influence the intestinal immune system that may not be physiologically significant. The gut flora induces APCs to produce IL-1β and IL-23,176-178 which enhance IL-17 and IL-22 production by ILCs (Fig. 2).82,83,114 In addition, group 3 ILCs express AHR,179 which recognizes, among other things, products of bacterial tryptophan metabolism.180

Although in the previously described examples the microbiota activates group 3 ILCs, there is evidence that it may also inhibit them. Eberl and colleagues identified IL-25 as a negative regulator of ILC cytokine production.99 In small-intestinal LTi cells and NCR+ ILC3s, Il22 expression in the steady-state was 1–2 orders of magnitude higher in GF mice than in their SPF counterparts. In addition, the proportion of IL-22-producing cells upon ex vivo stimulation with IL-23 was higher in GF mice than in SPF mice, and also in mice treated with streptomycin, colistin, and ampicillin from birth than in untreated mice. The authors found that the microbiota induces production of IL-25 by epithelial cells and that adding recombinant IL-25 decreases the in vitro ability of ILCs to produce IL-22 (Fig. 2). Reynders et al. also investigated IL-22 production by small-intestinal LTi cells and NCR+ ILC3s, in this case after ex vivo stimulation with IL-23.83 The proportion of cells producing IL-22 in this setting was about 2-fold higher in GF than in SPF mice, and recolonization of GF mice with a conventional flora restored IL-22 production to SPF levels within 5 wk.

These discrepant findings—i.e., that the microbiota can either activate or inhibit ILCs—may be partially attributable to differences in the microbiotas of the SPF mice in these studies. The dominant effect of the microbiota may differ widely depending on its composition. For example, in a microbiota with many organisms containing flagellin, which induces intestinal DCs to produce IL-23,176 bacterium-induced upregulation of IL-23 stimulation may be substantial and, as a result, that particular microbiota may predominantly activate ILCs. In contrast, a more “regulatory” microbiota that induces large amounts of IL-25 production may predominantly inhibit ILCs. This explanation, however, does not fully account for the differences in the studies cited: GF mice, which have an identical (i.e., absent) microbiota in all facilities, had very different levels of IL-22 production and expression in the papers cited.96,99,115 Nevertheless, it is certainly possible that, in other settings, different microbiotas have different immunomodulatory effects. To better understand these effects, it will be important to identify specific organisms that influence ILC function and to define the mechanisms by which they do so.

Lymphoid tissue development

The development of lymphoid tissues such as SLOs and ILFs is a unique and important function of RORγt+ ILCs.103,181 This process is largely microbe-driven and involves NOD1.54 While investigating microbe-associated pattern receptors in the setting of ILF formation, Bouskra et al. found that the number of ILFs in both the small intestine and the colon was substantially decreased in GF mice from that in SPF mice.54 They attempted to identify types of organisms responsible for this effect by monocolonizing 8-wk-old GF mice with individual bacterial species. Specific gram-negative organisms, including E. coli, increased the number of ILFs above GF levels, but the gram-positive Lactobacillus acidophilus did not. Consistent with that finding, mice treated from birth until 8 wk of age with colistin, which targets gram-negative bacteria, had fewer ILFs than mice treated with vancomycin, which targets gram-positive bacteria. The investigators found that peptidoglycan is a major mediator of this effect. Mice lacking NOD1, which recognizes peptidoglycans from gram-negative bacteria, had fewer small-intestinal ILFs and hypertrophic cryptopatches, indicating defective maturation from cryptopatches to ILFs, and mice monocolonized with WT E. coli had more ILFs than GF mice or mice monocolonized with an E. coli strain that produces very small amounts of peptidoglycan. Of note, in the colon of NOD1−/− mice, there were actually more ILFs and more hypertrophically mature ILFs, which suggested that the greater bacterial load in the colon triggers NOD1- and peptidoglycan-independent pathways to induce ILF maturation; these other pathways remain to be identified. Still, these results indicate that NOD1 recognition of gram-negative bacterial products such as peptidoglycan is critical for LTi cell localization and induction of ILF development as well as for ILF maturation.

In contrast, Mebius and colleagues found that while—consistent with the previous paper—a greater proportion of ILFs were immature in GF mice, colonic ILF numbers were equal in GF and SPF mice.182 These results suggest that colonic bacteria are actually unnecessary for LTi cell induction of ILFs. However, antibiotic treatment with streptomycin, ampicillin, and colistin from embryonic day E14 to postpartum day 14 did not affect colonic ILF numbers or maturation, possibly due to incomplete depletion of colonic bacteria. These results are consistent with a classic paper demonstrating that small-intestinal cryptopatch numbers are normal in GF mice.183

In addition to NOD1, another mechanism by which the microbiota may influence ILF development is AHR.58 Kiss et al. found that there were virtually no ILFs in AHR-deficient mice.179 While newborn AHR−/− mice have normal numbers of group 3 ILCs, by 8 wk of age the AHR−/− mice in this study had several times fewer group 3 ILCs than their WT counterparts. This difference indicates that while AHR is dispensable for prenatal ILC development, it is important for expansion or survival of ILCs postnatally. ILCs from AHR-deficient mice demonstrated decreased proliferation, perhaps because AHR stabilized the expression of Kit, a receptor kinase important for ILC proliferation. The authors identified indole-3-carbinol, a product of hydrolysis of a phytochemical, as an AHR ligand and critical regulator of ILF formation and ILC proliferation,179 which indicates that diet too likely influences lymphoid tissue development. While, citing earlier studies,183 they reasoned that bacterial AHR ligands are unlikely to have a similar effect, they did not rule out that possibility experimentally, and it may be that the microbiome may play a role in ILF formation through AHR.

Conclusions

In this review, we have discussed the intestinal immune system and its effect on the gut flora, focusing primarily on ILCs, a heterogeneous class of lymphocytes that are critical components of the innate immune system. The gut flora clearly has profound effects on intestinal ILC function. Microbiota-induced IL-7 and IL-25 regulate ILC cytokine production, and the microbiota may also signal ILCs more directly through NOD1 and AHR. Our understanding of ILC development, function in health and disease, and interactions with the intestinal microbiota has expanded tremendously in the last several years. In the future, it will be important to identify more specific host and bacterial molecules involved in bacteria–ILC interactions, as these cells and the bacterial molecules could ultimately become targets of therapeutic agents. Likewise, identifying the precise organisms that interact most closely with ILCs will help us target the microbiota, perhaps with probiotics or antibiotics, to modulate the role of ILCs in disease. Finally, with the exception of NK cells, human ILCs are far less well characterized than their murine counterparts. We have already identified intriguing differences between human and murine ILCs, and further exploration of human ILC biology may yield interesting insights relevant to human health.

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest

No potential conflict of interest was disclosed.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr Suryasarathi Dasgupta and Dr Neeraj K Surana for critical discussion of this manuscript and Julie B McCoy for her excellent editorial work.

Glossary

Abbreviations:

- AHR

aryl hydrogen receptor

- APC

antigen-presenting cell

- CCR

CC-chemokine receptor

- DC

dendritic cell

- Foxp3

forkhead box P3

- GF

germ-free

- IBD

inflammatory bowel disease

- IFN

interferon

- Ig

immunoglobulin

- IL

interleukin

- ILC

innate lymphoid cell

- ILF

isolated lymphoid follicle

- LT

lymphotoxin

- LTi

lymphoid tissue inducer

- MHC

major histocompatibility complex

- MLN

mesenteric lymph node

- NCR

natural cytotoxicity receptor

- NK

natural killer

- NOD

nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain–containing

- PP

Peyer’s patch

- PSA

polysaccharide A

- ROR

retinoic acid–related orphan receptor

- SFB

segmented filamentous bacterium

- SLO

secondary lymphoid organ

- SPF

specific pathogen–free

- TCR

T cell receptor

- Th

T helper

- TLR

Toll-like receptor

- TNBS

trinitrobenzenesulfonic acid

- TNF

tumor necrosis factor

- Treg

regulatory T cell

- WT

wild-type

References

- 1.Bäckhed F, Ley RE, Sonnenburg JL, Peterson DA, Gordon JI. Host-bacterial mutualism in the human intestine. Science. 2005;307:1915–20. doi: 10.1126/science.1104816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chung H, Kasper DL. Microbiota-stimulated immune mechanisms to maintain gut homeostasis. Curr Opin Immunol. 2010;22:455–60. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2010.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gill SR, Pop M, Deboy RT, Eckburg PB, Turnbaugh PJ, Samuel BS, Gordon JI, Relman DA, Fraser-Liggett CM, Nelson KE. Metagenomic analysis of the human distal gut microbiome. Science. 2006;312:1355–9. doi: 10.1126/science.1124234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nicholson JK, Holmes E, Wilson ID. Gut microorganisms, mammalian metabolism and personalized health care. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2005;3:431–8. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stappenbeck TS, Hooper LV, Gordon JI. Developmental regulation of intestinal angiogenesis by indigenous microbes via Paneth cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:15451–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.202604299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Diaz Heijtz R, Wang S, Anuar F, Qian Y, Björkholm B, Samuelsson A, Hibberd ML, Forssberg H, Pettersson S. Normal gut microbiota modulates brain development and behavior. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:3047–52. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1010529108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Qin J, Li R, Raes J, Arumugam M, Burgdorf KS, Manichanh C, Nielsen T, Pons N, Levenez F, Yamada T, et al. MetaHIT Consortium A human gut microbial gene catalogue established by metagenomic sequencing. Nature. 2010;464:59–65. doi: 10.1038/nature08821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Claesson MJ, Jeffery IB, Conde S, Power SE, O’Connor EM, Cusack S, Harris HM, Coakley M, Lakshminarayanan B, O’Sullivan O, et al. Gut microbiota composition correlates with diet and health in the elderly. Nature. 2012;488:178–84. doi: 10.1038/nature11319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bäckhed F, Ding H, Wang T, Hooper LV, Koh GY, Nagy A, Semenkovich CF, Gordon JI. The gut microbiota as an environmental factor that regulates fat storage. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:15718–23. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0407076101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ley RE, Bäckhed F, Turnbaugh P, Lozupone CA, Knight RD, Gordon JI. Obesity alters gut microbial ecology. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:11070–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0504978102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Musso G, Gambino R, Cassader M. Interactions between gut microbiota and host metabolism predisposing to obesity and diabetes. Annu Rev Med. 2011;62:361–80. doi: 10.1146/annurev-med-012510-175505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Turnbaugh PJ, Ley RE, Mahowald MA, Magrini V, Mardis ER, Gordon JI. An obesity-associated gut microbiome with increased capacity for energy harvest. Nature. 2006;444:1027–31. doi: 10.1038/nature05414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vijay-Kumar M, Aitken JD, Carvalho FA, Cullender TC, Mwangi S, Srinivasan S, Sitaraman SV, Knight R, Ley RE, Gewirtz AT. Metabolic syndrome and altered gut microbiota in mice lacking Toll-like receptor 5. Science. 2010;328:228–31. doi: 10.1126/science.1179721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhang H, DiBaise JK, Zuccolo A, Kudrna D, Braidotti M, Yu Y, Parameswaran P, Crowell MD, Wing R, Rittmann BE, et al. Human gut microbiota in obesity and after gastric bypass. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:2365–70. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0812600106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Moore WE, Moore LH. Intestinal floras of populations that have a high risk of colon cancer. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1995;61:3202–7. doi: 10.1128/aem.61.9.3202-3207.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Marchesi JR, Dutilh BE, Hall N, Peters WHM, Roelofs R, Boleij A, Tjalsma H. Towards the human colorectal cancer microbiome. PLoS One. 2011;6:e20447. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0020447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pflughoeft KJ, Versalovic J. Human microbiome in health and disease. Annu Rev Pathol. 2012;7:99–122. doi: 10.1146/annurev-pathol-011811-132421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Azad MB, Kozyrskyj AL. Perinatal programming of asthma: the role of gut microbiota. Clin Dev Immunol. 2012;2012:932072. doi: 10.1155/2012/932072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Huffnagle GB. The microbiota and allergies/asthma. PLoS Pathog. 2010;6:e1000549. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Darfeuille-Michaud A, Boudeau J, Bulois P, Neut C, Glasser A-L, Barnich N, Bringer MA, Swidsinski A, Beaugerie L, Colombel JF. High prevalence of adherent-invasive Escherichia coli associated with ileal mucosa in Crohn’s disease. Gastroenterology. 2004;127:412–21. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2004.04.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sokol H, Pigneur B, Watterlot L, Lakhdari O, Bermúdez-Humarán LG, Gratadoux JJ, Blugeon S, Bridonneau C, Furet JP, Corthier G, et al. Faecalibacterium prausnitzii is an anti-inflammatory commensal bacterium identified by gut microbiota analysis of Crohn disease patients. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:16731–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0804812105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wang Z, Klipfell E, Bennett BJ, Koeth R, Levison BS, Dugar B, Feldstein AE, Britt EB, Fu X, Chung YM, et al. Gut flora metabolism of phosphatidylcholine promotes cardiovascular disease. Nature. 2011;472:57–63. doi: 10.1038/nature09922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tang WHW, Wang Z, Levison BS, Koeth RA, Britt EB, Fu X, Wu Y, Hazen SL. Intestinal microbial metabolism of phosphatidylcholine and cardiovascular risk. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:1575–84. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1109400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chung H, Pamp SJ, Hill JA, Surana NK, Edelman SM, Troy EB, Reading NC, Villablanca EJ, Wang S, Mora JR, et al. Gut immune maturation depends on colonization with a host-specific microbiota. Cell. 2012;149:1578–93. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.04.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Atarashi K, Tanoue T, Shima T, Imaoka A, Kuwahara T, Momose Y, Cheng G, Yamasaki S, Saito T, Ohba Y, et al. Induction of colonic regulatory T cells by indigenous Clostridium species. Science. 2011;331:337–41. doi: 10.1126/science.1198469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ivanov II, Atarashi K, Manel N, Brodie EL, Shima T, Karaoz U, Wei D, Goldfarb KC, Santee CA, Lynch SV, et al. Induction of intestinal Th17 cells by segmented filamentous bacteria. Cell. 2009;139:485–98. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.09.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mazmanian SK, Liu CH, Tzianabos AO, Kasper DL. An immunomodulatory molecule of symbiotic bacteria directs maturation of the host immune system. Cell. 2005;122:107–18. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mazmanian SK, Round JL, Kasper DL. A microbial symbiosis factor prevents intestinal inflammatory disease. Nature. 2008;453:620–5. doi: 10.1038/nature07008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gaboriau-Routhiau V, Rakotobe S, Lécuyer E, Mulder I, Lan A, Bridonneau C, Rochet V, Pisi A, De Paepe M, Brandi G, et al. The key role of segmented filamentous bacteria in the coordinated maturation of gut helper T cell responses. Immunity. 2009;31:677–89. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.08.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Talham GL, Jiang H-Q, Bos NA, Cebra JJ. Segmented filamentous bacteria are potent stimuli of a physiologically normal state of the murine gut mucosal immune system. Infect Immun. 1999;67:1992–2000. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.4.1992-2000.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Round JL, Mazmanian SK. The gut microbiota shapes intestinal immune responses during health and disease. Nat Rev Immunol. 2009;9:313–23. doi: 10.1038/nri2515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Duan J, Kasper DL. Regulation of T cells by gut commensal microbiota. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2011;23:372–6. doi: 10.1097/BOR.0b013e3283476d3e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dasgupta S, Kasper DL. Novel tools for modulating immune responses in the host-polysaccharides from the capsule of commensal bacteria. Adv Immunol. 2010;106:61–91. doi: 10.1016/S0065-2776(10)06003-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Eberl G. Inducible lymphoid tissues in the adult gut: recapitulation of a fetal developmental pathway? Nat Rev Immunol. 2005;5:413–20. doi: 10.1038/nri1600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Witmer MD, Steinman RM. The anatomy of peripheral lymphoid organs with emphasis on accessory cells: light-microscopic immunocytochemical studies of mouse spleen, lymph node, and Peyer’s patch. Am J Anat. 1984;170:465–81. doi: 10.1002/aja.1001700318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Makala LHC, Suzuki N, Nagasawa H. Peyer’s patches: organized lymphoid structures for the induction of mucosal immune responses in the intestine. Pathobiology. 2002-2003;70:55–68. doi: 10.1159/000067305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bockman DE, Cooper MD. Pinocytosis by epithelium associated with lymphoid follicles in the bursa of Fabricius, appendix, and Peyer’s patches. An electron microscopic study. Am J Anat. 1973;136:455–77. doi: 10.1002/aja.1001360406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Owen RL, Pierce NF, Apple RT, Cray WC., Jr. M cell transport of Vibrio cholerae from the intestinal lumen into Peyer’s patches: a mechanism for antigen sampling and for microbial transepithelial migration. J Infect Dis. 1986;153:1108–18. doi: 10.1093/infdis/153.6.1108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pappo J, Ermak TH. Uptake and translocation of fluorescent latex particles by rabbit Peyer’s patch follicle epithelium: a quantitative model for M cell uptake. Clin Exp Immunol. 1989;76:144–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kelsall BL, Strober W. Distinct populations of dendritic cells are present in the subepithelial dome and T cell regions of the murine Peyer’s patch. J Exp Med. 1996;183:237–47. doi: 10.1084/jem.183.1.237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Iwasaki A, Kelsall BL. Localization of distinct Peyer’s patch dendritic cell subsets and their recruitment by chemokines macrophage inflammatory protein (MIP)-3α, MIP-3β, and secondary lymphoid organ chemokine. J Exp Med. 2000;191:1381–94. doi: 10.1084/jem.191.8.1381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Macpherson AJ, Uhr T. Induction of protective IgA by intestinal dendritic cells carrying commensal bacteria. Science. 2004;303:1662–5. doi: 10.1126/science.1091334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pierce NF, Gowans JL. Cellular kinetics of the intestinal immune response to cholera toxoid in rats. J Exp Med. 1975;142:1550–63. doi: 10.1084/jem.142.6.1550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Williams AF, Gowans JL. The presence of IgA on the surface of rat thoractic duct lymphocytes which contain internal IgA. J Exp Med. 1975;141:335–45. doi: 10.1084/jem.141.2.335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Arstila T, Arstila TP, Calbo S, Selz F, Malassis-Seris M, Vassalli P, Kourilsky P, Guy-Grand D. Identical T cell clones are located within the mouse gut epithelium and lamina propia and circulate in the thoracic duct lymph. J Exp Med. 2000;191:823–34. doi: 10.1084/jem.191.5.823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Macpherson AJ, Harris NL. Interactions between commensal intestinal bacteria and the immune system. Nat Rev Immunol. 2004;4:478–85. doi: 10.1038/nri1373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hooper LV, Macpherson AJ. Immune adaptations that maintain homeostasis with the intestinal microbiota. Nat Rev Immunol. 2010;10:159–69. doi: 10.1038/nri2710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Iwasaki A. Mucosal dendritic cells. Annu Rev Immunol. 2007;25:381–418. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.25.022106.141634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Johansson C, Kelsall BL. Phenotype and function of intestinal dendritic cells. Semin Immunol. 2005;17:284–94. doi: 10.1016/j.smim.2005.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Niess JH, Reinecker H-C. Dendritic cells: the commanders-in-chief of mucosal immune defenses. Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2006;22:354–60. doi: 10.1097/01.mog.0000231807.03149.54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Varol C, Vallon-Eberhard A, Elinav E, Aychek T, Shapira Y, Luche H, Fehling HJ, Hardt WD, Shakhar G, Jung S. Intestinal lamina propria dendritic cell subsets have different origin and functions. Immunity. 2009;31:502–12. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.06.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Craig SW, Cebra JJ. Peyer’s patches: an enriched source of precursors for IgA-producing immunocytes in the rabbit. J Exp Med. 1971;134:188–200. doi: 10.1084/jem.134.1.188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Macpherson AJ, Slack E. The functional interactions of commensal bacteria with intestinal secretory IgA. Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2007;23:673–8. doi: 10.1097/MOG.0b013e3282f0d012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Bouskra D, Brézillon C, Bérard M, Werts C, Varona R, Boneca IG, Eberl G. Lymphoid tissue genesis induced by commensals through NOD1 regulates intestinal homeostasis. Nature. 2008;456:507–10. doi: 10.1038/nature07450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kang H-S, Chin RK, Wang Y, Yu P, Wang J, Newell KA, Fu YX. Signaling via LTbetaR on the lamina propria stromal cells of the gut is required for IgA production. Nat Immunol. 2002;3:576–82. doi: 10.1038/ni795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Spits H, Artis D, Colonna M, Diefenbach A, Di Santo JP, Eberl G, Koyasu S, Locksley RM, McKenzie AN, Mebius RE, et al. Innate lymphoid cells--a proposal for uniform nomenclature. Nat Rev Immunol. 2013;13:145–9. doi: 10.1038/nri3365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Veldhoen M, Withers DR. Immunology. Innate lymphoid cell relations. Science. 2010;330:594–5. doi: 10.1126/science.1198298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Spits H, Cupedo T. Innate lymphoid cells: emerging insights in development, lineage relationships, and function. Annu Rev Immunol. 2012;30:647–75. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-020711-075053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Fuchs A, Vermi W, Lee JS, Lonardi S, Gilfillan S, Newberry RD, Cella M, Colonna M. Intraepithelial type 1 innate lymphoid cells are a unique subset of IL-12- and IL-15-responsive IFN-γ-producing cells. Immunity. 2013;38:769–81. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2013.02.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Szabo SJ, Sullivan BM, Stemmann C, Satoskar AR, Sleckman BP, Glimcher LH. Distinct effects of T-bet in TH1 lineage commitment and IFN-γ production in CD4 and CD8 T cells. Science. 2002;295:338–42. doi: 10.1126/science.1065543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Bernink JH, Peters CP, Munneke M, te Velde AA, Meijer SL, Weijer K, Hreggvidsdottir HS, Heinsbroek SE, Legrand N, Buskens CJ, et al. Human type 1 innate lymphoid cells accumulate in inflamed mucosal tissues. Nat Immunol. 2013;14:221–9. doi: 10.1038/ni.2534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Fehniger TA, Shah MH, Turner MJ, VanDeusen JB, Whitman SP, Cooper MA, Suzuki K, Wechser M, Goodsaid F, Caligiuri MA. Differential cytokine and chemokine gene expression by human NK cells following activation with IL-18 or IL-15 in combination with IL-12: implications for the innate immune response. J Immunol. 1999;162:4511–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Lauwerys BR, Garot N, Renauld J-C, Houssiau FA. Cytokine production and killer activity of NK/T-NK cells derived with IL-2, IL-15, or the combination of IL-12 and IL-18. J Immunol. 2000;165:1847–53. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.4.1847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Cooper MA, Fehniger TA, Caligiuri MA. The biology of human natural killer-cell subsets. Trends Immunol. 2001;22:633–40. doi: 10.1016/S1471-4906(01)02060-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Freud AG, Caligiuri MA. Human natural killer cell development. Immunol Rev. 2006;214:56–72. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2006.00451.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Khakoo SI, Thio CL, Martin MP, Brooks CR, Gao X, Astemborski J, Cheng J, Goedert JJ, Vlahov D, Hilgartner M, et al. HLA and NK cell inhibitory receptor genes in resolving hepatitis C virus infection. Science. 2004;305:872–4. doi: 10.1126/science.1097670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Dokun AO, Kim S, Smith HR, Kang HS, Chu DT, Yokoyama WM. Specific and nonspecific NK cell activation during virus infection. Nat Immunol. 2001;2:951–6. doi: 10.1038/ni714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Borg C, Terme M, Taïeb J, Ménard C, Flament C, Robert C, Maruyama K, Wakasugi H, Angevin E, Thielemans K, et al. Novel mode of action of c-kit tyrosine kinase inhibitors leading to NK cell-dependent antitumor effects. J Clin Invest. 2004;114:379–88. doi: 10.1172/JCI21102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Ruggeri L, Capanni M, Urbani E, Perruccio K, Shlomchik WD, Tosti A, Posati S, Rogaia D, Frassoni F, Aversa F, et al. Effectiveness of donor natural killer cell alloreactivity in mismatched hematopoietic transplants. Science. 2002;295:2097–100. doi: 10.1126/science.1068440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Deguine J, Breart B, Lemaître F, Bousso P. Cutting edge: tumor-targeting antibodies enhance NKG2D-mediated NK cell cytotoxicity by stabilizing NK cell-tumor cell interactions. J Immunol. 2012;189:5493–7. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1202065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Baxter AG, Smyth MJ. The role of NK cells in autoimmune disease. Autoimmunity. 2002;35:1–14. doi: 10.1080/08916930290005864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Walzer T, Bléry M, Chaix J, Fuseri N, Chasson L, Robbins SH, Jaeger S, André P, Gauthier L, Daniel L, et al. Identification, activation, and selective in vivo ablation of mouse NK cells via NKp46. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:3384–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0609692104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Halim TY, Krauss RH, Sun AC, Takei F. Lung natural helper cells are a critical source of Th2 cell-type cytokines in protease allergen-induced airway inflammation. Immunity. 2012;36:451–63. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2011.12.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Moro K, Yamada T, Tanabe M, Takeuchi T, Ikawa T, Kawamoto H, Furusawa J, Ohtani M, Fujii H, Koyasu S. Innate production of T(H)2 cytokines by adipose tissue-associated c-Kit(+)Sca-1(+) lymphoid cells. Nature. 2010;463:540–4. doi: 10.1038/nature08636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Mjösberg JM, Trifari S, Crellin NK, Peters CP, van Drunen CM, Piet B, Fokkens WJ, Cupedo T, Spits H. Human IL-25- and IL-33-responsive type 2 innate lymphoid cells are defined by expression of CRTH2 and CD161. Nat Immunol. 2011;12:1055–62. doi: 10.1038/ni.2104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Neill DR, Wong SH, Bellosi A, Flynn RJ, Daly M, Langford TKA, Bucks C, Kane CM, Fallon PG, Pannell R, et al. Nuocytes represent a new innate effector leukocyte that mediates type-2 immunity. Nature. 2010;464:1367–70. doi: 10.1038/nature08900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Klein Wolterink RG, Kleinjan A, van Nimwegen M, Bergen I, de Bruijn M, Levani Y, Hendriks RW. Pulmonary innate lymphoid cells are major producers of IL-5 and IL-13 in murine models of allergic asthma. Eur J Immunol. 2012;42:1106–16. doi: 10.1002/eji.201142018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Chang Y-J, Kim HY, Albacker LA, Baumgarth N, McKenzie AN, Smith DE, Dekruyff RH, Umetsu DT. Innate lymphoid cells mediate influenza-induced airway hyper-reactivity independently of adaptive immunity. Nat Immunol. 2011;12:631–8. doi: 10.1038/ni.2045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Monticelli LA, Sonnenberg GF, Artis D. Innate lymphoid cells: critical regulators of allergic inflammation and tissue repair in the lung. Curr Opin Immunol. 2012;24:284–9. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2012.03.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Monticelli LA, Sonnenberg GF, Abt MC, Alenghat T, Ziegler CG, Doering TA, Angelosanto JM, Laidlaw BJ, Yang CY, Sathaliyawala T, et al. Innate lymphoid cells promote lung-tissue homeostasis after infection with influenza virus. Nat Immunol. 2011;12:1045–54. doi: 10.1038/ni.2131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Buonocore S, Ahern PP, Uhlig HH, Ivanov II, Littman DR, Maloy KJ, Powrie F. Innate lymphoid cells drive interleukin-23-dependent innate intestinal pathology. Nature. 2010;464:1371–5. doi: 10.1038/nature08949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Chen VL, Surana NK, Duan J, Kasper DL. Role of murine intestinal interleukin-1 receptor 1-expressing lymphoid tissue inducer-like cells in salmonella infection. PLoS One. 2013;8:e65405. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0065405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Reynders A, Yessaad N, Vu Manh TP, Dalod M, Fenis A, Aubry C, Nikitas G, Escalière B, Renauld JC, Dussurget O, et al. Identity, regulation and in vivo function of gut NKp46+RORγt+ and NKp46+RORγt- lymphoid cells. EMBO J. 2011;30:2934–47. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2011.201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Eberl G, Marmon S, Sunshine M-J, Rennert PD, Choi Y, Littman DR. An essential function for the nuclear receptor RORgamma(t) in the generation of fetal lymphoid tissue inducer cells. Nat Immunol. 2004;5:64–73. doi: 10.1038/ni1022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Sawa S, Cherrier M, Lochner M, Satoh-Takayama N, Fehling HJ, Langa F, Di Santo JP, Eberl G. Lineage relationship analysis of RORgammat+ innate lymphoid cells. Science. 2010;330:665–9. doi: 10.1126/science.1194597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Klose CS, Kiss EA, Schwierzeck V, Ebert K, Hoyler T, d’Hargues Y, Göppert N, Croxford AL, Waisman A, Tanriver Y, et al. A T-bet gradient controls the fate and function of CCR6-RORγt+ innate lymphoid cells. Nature. 2013;494:261–5. doi: 10.1038/nature11813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Eyerich S, Eyerich K, Cavani A, Schmidt-Weber C. IL-17 and IL-22: siblings, not twins. Trends Immunol. 2010;31:354–61. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2010.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Huh JR, Leung MWL, Huang P, Ryan DA, Krout MR, Malapaka RRV, Chow J, Manel N, Ciofani M, Kim SV, et al. Digoxin and its derivatives suppress TH17 cell differentiation by antagonizing RORγt activity. Nature. 2011;472:486–90. doi: 10.1038/nature09978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Gladiator A, Wangler N, Trautwein-Weidner K, LeibundGut-Landmann S. Cutting edge: IL-17-secreting innate lymphoid cells are essential for host defense against fungal infection. J Immunol. 2013;190:521–5. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1202924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Lockhart E, Green AM, Flynn JL. IL-17 production is dominated by gammadelta T cells rather than CD4 T cells during Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection. J Immunol. 2006;177:4662–9. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.7.4662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Ye P, Garvey PB, Zhang P, Nelson S, Bagby G, Summer WR, Schwarzenberger P, Shellito JE, Kolls JK. Interleukin-17 and lung host defense against Klebsiella pneumoniae infection. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2001;25:335–40. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb.25.3.4424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Sonnenberg GF, Fouser LA, Artis D. Border patrol: regulation of immunity, inflammation and tissue homeostasis at barrier surfaces by IL-22. Nat Immunol. 2011;12:383–90. doi: 10.1038/ni.2025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Zheng Y, Valdez PA, Danilenko DM, Hu Y, Sa SM, Gong Q, Abbas AR, Modrusan Z, Ghilardi N, de Sauvage FJ, et al. Interleukin-22 mediates early host defense against attaching and effacing bacterial pathogens. Nat Med. 2008;14:282–9. doi: 10.1038/nm1720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Sugimoto K, Ogawa A, Mizoguchi E, Shimomura Y, Andoh A, Bhan AK, Blumberg RS, Xavier RJ, Mizoguchi A. IL-22 ameliorates intestinal inflammation in a mouse model of ulcerative colitis. J Clin Invest. 2008;118:534–44. doi: 10.1172/JCI33194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Sonnenberg GF, Monticelli LA, Elloso MM, Fouser LA, Artis D. CD4(+) lymphoid tissue-inducer cells promote innate immunity in the gut. Immunity. 2011;34:122–34. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2010.12.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Satoh-Takayama N, Vosshenrich CAJ, Lesjean-Pottier S, Sawa S, Lochner M, Rattis F, Mention JJ, Thiam K, Cerf-Bensussan N, Mandelboim O, et al. Microbial flora drives interleukin 22 production in intestinal NKp46+ cells that provide innate mucosal immune defense. Immunity. 2008;29:958–70. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2008.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Zenewicz LA, Yancopoulos GD, Valenzuela DM, Murphy AJ, Stevens S, Flavell RA. Innate and adaptive interleukin-22 protects mice from inflammatory bowel disease. Immunity. 2008;29:947–57. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2008.11.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Huber S, Gagliani N, Zenewicz LA, Huber FJ, Bosurgi L, Hu B, Hedl M, Zhang W, O’Connor W, Jr., Murphy AJ, et al. IL-22BP is regulated by the inflammasome and modulates tumorigenesis in the intestine. Nature. 2012;491:259–63. doi: 10.1038/nature11535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Sawa S, Lochner M, Satoh-Takayama N, Dulauroy S, Bérard M, Kleinschek M, Cua D, Di Santo JP, Eberl G. RORγt+ innate lymphoid cells regulate intestinal homeostasis by integrating negative signals from the symbiotic microbiota. Nat Immunol. 2011;12:320–6. doi: 10.1038/ni.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Kirchberger S, Royston DJ, Boulard O, Thornton E, Franchini F, Szabady RL, Harrison O, Powrie F. Innate lymphoid cells sustain colon cancer through production of interleukin-22 in a mouse model. J Exp Med. 2013;210:917–31. doi: 10.1084/jem.20122308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Sonnenberg GF, Monticelli LA, Alenghat T, Fung TC, Hutnick NA, Kunisawa J, Shibata N, Grunberg S, Sinha R, Zahm AM, et al. Innate lymphoid cells promote anatomical containment of lymphoid-resident commensal bacteria. Science. 2012;336:1321–5. doi: 10.1126/science.1222551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Hepworth MR, Monticelli LA, Fung TC, Ziegler CGK, Grunberg S, Sinha R, Mantegazza AR, Ma HL, Crawford A, Angelosanto JM, et al. Innate lymphoid cells regulate CD4+ T-cell responses to intestinal commensal bacteria. Nature. 2013;498:113–7. doi: 10.1038/nature12240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Mebius RE. Organogenesis of lymphoid tissues. Nat Rev Immunol. 2003;3:292–303. doi: 10.1038/nri1054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Kim D, Mebius RE, MacMicking JD, Jung S, Cupedo T, Castellanos Y, Rho J, Wong BR, Josien R, Kim N, et al. Regulation of peripheral lymph node genesis by the tumor necrosis factor family member TRANCE. J Exp Med. 2000;192:1467–78. doi: 10.1084/jem.192.10.1467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Yoshida H, Naito A, Inoue J, Satoh M, Santee-Cooper SM, Ware CF, Togawa A, Nishikawa S, Nishikawa S. Different cytokines induce surface lymphotoxin-alphabeta on IL-7 receptor-α cells that differentially engender lymph nodes and Peyer’s patches. Immunity. 2002;17:823–33. doi: 10.1016/S1074-7613(02)00479-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Dejardin E, Droin NM, Delhase M, Haas E, Cao Y, Makris C, Li ZW, Karin M, Ware CF, Green DR. The lymphotoxin-β receptor induces different patterns of gene expression via two NF-kappaB pathways. Immunity. 2002;17:525–35. doi: 10.1016/S1074-7613(02)00423-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Ngo VN, Korner H, Gunn MD, Schmidt KN, Riminton DS, Cooper MD, Browning JL, Sedgwick JD, Cyster JG. Lymphotoxin α/β and tumor necrosis factor are required for stromal cell expression of homing chemokines in B and T cell areas of the spleen. J Exp Med. 1999;189:403–12. doi: 10.1084/jem.189.2.403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Veiga-Fernandes H, Coles MC, Foster KE, Patel A, Williams A, Natarajan D, Barlow A, Pachnis V, Kioussis D. Tyrosine kinase receptor RET is a key regulator of Peyer’s patch organogenesis. Nature. 2007;446:547–51. doi: 10.1038/nature05597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Tsuji M, Suzuki K, Kitamura H, Maruya M, Kinoshita K, Ivanov II, Itoh K, Littman DR, Fagarasan S. Requirement for lymphoid tissue-inducer cells in isolated follicle formation and T cell-independent immunoglobulin A generation in the gut. Immunity. 2008;29:261–71. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2008.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Kim MY, Gaspal FM, Wiggett HE, McConnell FM, Gulbranson-Judge A, Raykundalia C, Walker LS, Goodall MD, Lane PJ. CD4(+)CD3(-) accessory cells costimulate primed CD4 T cells through OX40 and CD30 at sites where T cells collaborate with B cells. Immunity. 2003;18:643–54. doi: 10.1016/S1074-7613(03)00110-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Rogers PR, Song J, Gramaglia I, Killeen N, Croft M. OX40 promotes Bcl-xL and Bcl-2 expression and is essential for long-term survival of CD4 T cells. Immunity. 2001;15:445–55. doi: 10.1016/S1074-7613(01)00191-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Withers DR, Gaspal FM, Mackley EC, Marriott CL, Ross EA, Desanti GE, Roberts NA, White AJ, Flores-Langarica A, McConnell FM, et al. Cutting edge: lymphoid tissue inducer cells maintain memory CD4 T cells within secondary lymphoid tissue. J Immunol. 2012;189:2094–8. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1201639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Gaspal F, Bekiaris V, Kim M-Y, Withers DR, Bobat S, MacLennan ICM, Anderson G, Lane PJ, Cunningham AF. Critical synergy of CD30 and OX40 signals in CD4 T cell homeostasis and Th1 immunity to Salmonella. J Immunol. 2008;180:2824–9. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.5.2824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Takatori H, Kanno Y, Watford WT, Tato CM, Weiss G, Ivanov II, Littman DR, O’Shea JJ. Lymphoid tissue inducer-like cells are an innate source of IL-17 and IL-22. J Exp Med. 2009;206:35–41. doi: 10.1084/jem.20072713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Sanos SL, Bui VL, Mortha A, Oberle K, Heners C, Johner C, Diefenbach A. RORgammat and commensal microflora are required for the differentiation of mucosal interleukin 22-producing NKp46+ cells. Nat Immunol. 2009;10:83–91. doi: 10.1038/ni.1684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Dumoutier L, de Heusch M, Orabona C, Satoh-Takayama N, Eberl G, Sirard JC, Di Santo JP, Renauld JC. IL-22 is produced by γC-independent CD25+ CCR6+ innate murine spleen cells upon inflammatory stimuli and contributes to LPS-induced lethality. Eur J Immunol. 2011;41:1075–85. doi: 10.1002/eji.201040878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Crellin NK, Trifari S, Kaplan CD, Satoh-Takayama N, Di Santo JP, Spits H. Regulation of cytokine secretion in human CD127(+) LTi-like innate lymphoid cells by Toll-like receptor 2. Immunity. 2010;33:752–64. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2010.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Cupedo T, Crellin NK, Papazian N, Rombouts EJ, Weijer K, Grogan JL, Fibbe WE, Cornelissen JJ, Spits H. Human fetal lymphoid tissue-inducer cells are interleukin 17-producing precursors to RORC+ CD127+ natural killer-like cells. Nat Immunol. 2009;10:66–74. doi: 10.1038/ni.1668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Geremia A, Arancibia-Cárcamo CV, Fleming MP, Rust N, Singh B, Mortensen NJ, Travis SP, Powrie F. IL-23-responsive innate lymphoid cells are increased in inflammatory bowel disease. J Exp Med. 2011;208:1127–33. doi: 10.1084/jem.20101712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Luci C, Reynders A, Ivanov II, Cognet C, Chiche L, Chasson L, Hardwigsen J, Anguiano E, Banchereau J, Chaussabel D, et al. Influence of the transcription factor RORgammat on the development of NKp46+ cell populations in gut and skin. Nat Immunol. 2009;10:75–82. doi: 10.1038/ni.1681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Vonarbourg C, Mortha A, Bui VL, Hernandez PP, Kiss EA, Hoyler T, Flach M, Bengsch B, Thimme R, Hölscher C, et al. Regulated expression of nuclear receptor RORγt confers distinct functional fates to NK cell receptor-expressing RORγt(+) innate lymphocytes. Immunity. 2010;33:736–51. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2010.10.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Duan J, Chung H, Troy E, Kasper DL. Microbial colonization drives expansion of IL-1 receptor 1-expressing and IL-17-producing γ/δ T cells. Cell Host Microbe. 2010;7:140–50. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2010.01.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Olszak T, An D, Zeissig S, Vera MP, Richter J, Franke A, Glickman JN, Siebert R, Baron RM, Kasper DL, et al. Microbial exposure during early life has persistent effects on natural killer T cell function. Science. 2012;336:489–93. doi: 10.1126/science.1219328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Gibson FC, 3rd, Onderdonk AB, Kasper DL, Tzianabos AO. Cellular mechanism of intraabdominal abscess formation by Bacteroides fragilis. J Immunol. 1998;160:5000–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Onderdonk AB, Markham RB, Zaleznik DF, Cisneros RL, Kasper DL. Evidence for T cell-dependent immunity to Bacteroides fragilis in an intraabdominal abscess model. J Clin Invest. 1982;69:9–16. doi: 10.1172/JCI110445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Surana NK, Kasper DL. The yin yang of bacterial polysaccharides: lessons learned from B. fragilis PSA. Immunol Rev. 2012;245:13–26. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2011.01075.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Avci FY, Kasper DL. How bacterial carbohydrates influence the adaptive immune system. Annu Rev Immunol. 2010;28:107–30. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-030409-101159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]