Abstract

Aging and many neurological disorders, such as AD, are linked to oxidative stress, which is considered the common effector of the cascade of degenerative events. In this phenomenon, reactive oxygen species play a fundamental role in the oxidative decomposition of polyunsaturated fatty acids, resulting in the formation of a complex mixture of aldehydic end products, such as malondialdehyde, 4-hydroxynonenal, and other alkenals. Interestingly, 4-HNE has been indicated as an intracellular agonist of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor β/δ. In this study, we examined, at early and advanced AD stages (3, 9, and 18 months), the pattern of 4-HNE and its catabolic enzyme glutathione S-transferase P1 in relation to the expression of PPARβ/δ, BDNF signaling, as mRNA and protein, as well as on their pathological forms (i.e., precursors or truncated forms). The data obtained indicate a novel detrimental age-dependent role of PPAR β/δ in AD by increasing pro-BDNF and decreasing BDNF/TrkB survival pathways, thus pointing toward the possibility that a specific PPARβ/δ antagonist may be used to counteract the disease progression.

Keywords: aging, neurodegenerative disease, transcription factors, oxidative stress, BDNF, TrkB, p75, JNK

Introduction

Aging is a multifactorial process characterized by a broad functional decline, including cognitive impairment, associated with alterations to neocortical and hippocampal areas, both involved in learning and memory processes. In general, cognitive processes require neuronal plasticity, which markedly decreases during aging and in neurodegenerative disorders, such as Alzheimer disease (AD). AD is the most common form of dementia, characterized by a progressive loss of synapses and neurons, resulting in gradual impairment of memory, language, and reasoning skills.1 The main histopathological features of AD are extracellular plaques, formed by amyloid-β (Aβ) deposits and intracellular neurofibrillary tangles of hyperphosphorylated tau protein. Both types of deposits are caused by the conversion of soluble forms of the proteins into insoluble, fibrillary polymers.2,3

Aging and many neurological disorders are linked to oxidative stress, which is considered the common effector of the cascade of degenerative events.4,5 In this phenomenon, reactive oxygen species (ROS) play a fundamental role in the oxidative decomposition of polyunsaturated fatty acids (i.e., lipid peroxidation), resulting in the formation of a complex mixture of aldehydic end products, such as malondialdehyde (MDA), 4-hydroxynonenal (4-HNE), and other alkenals.6,7 Among such aldehydes, 4-HNE has become the most studied cytotoxic product of lipid peroxidation8 and is considered one of the main signaling molecules in the pathogenesis of neurodegenerative diseases. Moderate 4-HNE concentrations can induce differentiation, damage to proteasome,9,10 and apoptosis11,12 by modifying signal transduction, including activation of adenylate cyclase, JNK, PKC, and caspase 3, while lower concentrations of the aldehyde appear to even promote cell proliferation and survival.8,13

Interestingly, 4-HNE has been also indicated as an intracellular agonist of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor β/δ (PPAR β/δ).14

PPARs, which comprise isotypes α, β/δ, and γ, are ligand-activated transcription factors playing important physiological and pathological roles in different tissues, including the nervous tissue, both during development and in the pathogenesis of various disorders. Indeed, their involvement in neurodegenerative diseases, such as multiple sclerosis, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, Alzheimer, Parkinson, and Huntington diseases, is well recognized.15-22

Even though PPAR β/δ is the most abundant isotype in the developing and adult central nervous system (CNS),23-25 its role in neurodegenerative diseases remains unclear. We have previously demonstrated that PPAR β/δ is crucial for neuronal maturation, and that its expression affects the BDNF signaling pathway.26,27

Neurotrophins and their receptors are expressed in brain areas involved in plasticity (i.e., the hippocampus, cerebral cortex) and are considered the mediators of synaptic plasticity. The expression of BDNF and its receptors, the full-length catalytic receptor (TrkB-fl), the truncated isoform (TrkB-t), lacking intracellular tyrosine kinase activity, and the unselective low-affinity p75NGFR receptor has been described during normal brain aging and in Alzheimer disease.28

The aim of the present work was to investigate the role of 4-HNE and PPAR β/δ in relation to BDNF signaling during AD progression and in physiological aging. To this purpose, we used the Tg2576 (Tg) mouse model, as compared with its wild-type (Wt) counterpart. Differently from other AD mouse models, this strain is characterized by a slowly progressive pathology, offering the opportunity to study even subtle age-dependent alterations.17,29,30,31 In the present study, we focused on the neocortex, which is more exposed to ROS, compared with other brain regions, owing to its high aerobic metabolism and content in PUFAs and redox-active transition metals.5,32 To this purpose, we examined at early and advanced AD stages (3, 9, and 18 mo) the pattern of 4-HNE and its catabolic enzyme glutathione S-transferase P1 (GSTP1)33 in relation to the expression of PPARβ/δ, BDNF, and its receptors, as mRNA and protein, as well as on their pathological forms (i.e., precursors or truncated forms).

The data obtained indicate a detrimental age-dependent role of PPAR β/δ in AD by increasing pro-BDNF and decreasing BDNF/TrkB survival pathway, thus suggesting that a specific PPARβ/δ antagonist may be used to counteract the disease progression.

Results

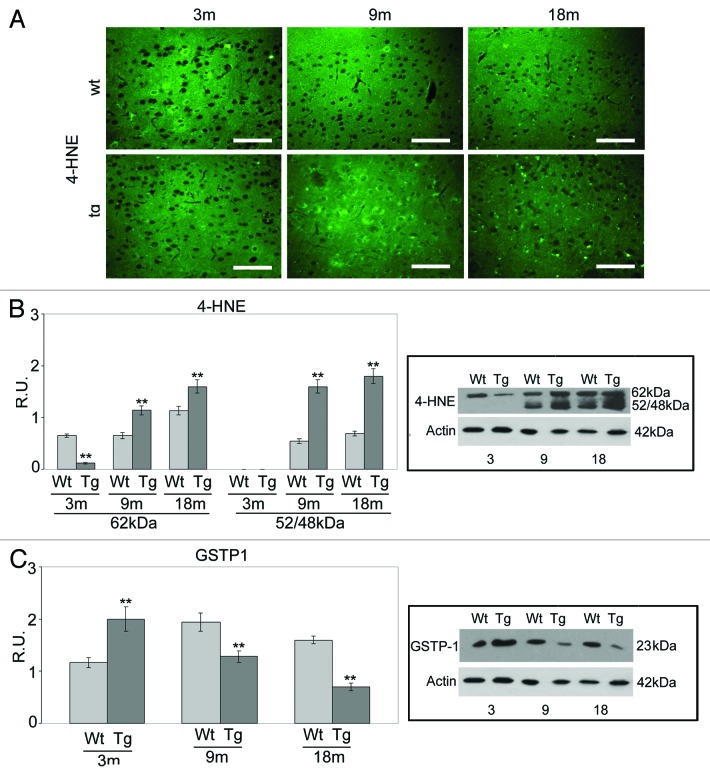

Oxidative damage has been reported in AD mice17,22,34,35 and lipid peroxidation products, such as 4-HNE,36 have been found to play an important role in AD-related neurodegeneration. Since 4-HNE has been recognized as an endogenous PPAR β/δ-ligand,14 the levels of its protein adducts were investigated. Immunofluorescence and WB results (Fig. 1A and B) show that HNE adduct levels in 9- and 18-mo-old neocortex are higher in Tg mice than in their Wt counterparts. At these ages, an additional 48/52-kDa band, denser in the Tg than in Wt samples, is observed. By contrast, at the onset of disease (3 mo), 4-HNE levels are much lower in Tg than in Wt neocortex. These data may be related to the expression pattern of GSTP-1 (Fig. 1C), known to remove 4-HNE.33 In fact, in 3-mo-old Tg animals, the enzymatic protein is upregulated, while at 9 and 18 mo, it appears progressively downregulated. This event does not happen in Wt animals, where the GSTP1 levels appear upregulated during aging, and not significant increases of HNE adducts are observed.

Figure 1. HNE adducts in Wt and Tg cortices at different ages. (A) HNE immunolocalization in 3-, 9- and 18-mo Wt and Tg cortex sections. Three Tg mice and 3 Wt littermates for each age considered were deeply anesthetized before rapid killing by transcardial perfusion. Mice were perfusion-fixed, and brains were paraffin-embedded. Sagittal brain sections from Tg and Wt animals were deparaffinized and incubated with PBS containing 0.01% trypsin, for 10 min at 37° and processed for the antigen-retrieval procedure, using a microwave oven operated at 720 W. After cooling, slides were transferred to PBS containing 4% BSA for 2 h at RT, then incubated overnight at 4 °C with mouse monoclonal anti-HNE. Sections were thoroughly rinsed with PBS, then incubated for 2 h at RT with goat anti-mouse IgG Alexafluor 488/546 conjugated diluted 1:2000 in blocking solution. Controls were performed in parallel by omitting the primary antibody. Slides were observed at florescence microscope AXIOPHOT Zeiss microscope equipped with Leica DFC 350 FX camera. Image acquisition was performed with Leica IM500 program. Bar = 50 μm. (B) Western blotting analysis for HNE protein adducts in Wt and Tg animals at the indicated ages. SDS-PAGE was performed running samples (20 μg protein) on 7.5–15% polyacrylamide denaturing gels. Protein bands were blotted onto polyvinylidene fluoride sheets. Non-specific binding sites were blocked for 1 h at RT with 5% (w/v) non-fat dry milk in TBS-T. Membranes were incubated overnight at 4°C with mouse monoclonal anti-HNE (1:400), followed by incubation with 1:2000 HRP-conjugated anti-mouse IgG secondary antibody in blocking solution, for 1 h at 4°C. After rinsing, immunoreactive bands were visualized by ECL. The relative densities of the immunoreactive bands were determined and normalized with respect to β-actin, using a semiquantitative densitometric analysis. Data are mean ± SD of 4 different experiments. **, P < 0.001, AD vs. the respective Wt. (C) Western blotting analysis for gluthatione S-transferase (GSTP1) in Wt and Tg animals at the indicated ages. SDS-PAGE was performed running samples (20 μg protein) on 7.5–15% polyacrylamide denaturing gels. Protein bands were blotted onto polyvinylidene fluoride sheets. Non-specific binding sites were blocked for 1 h at RT with 5% (w/v) non-fat dry milk in TBS-T. Membranes were incubated overnight at 4°C with rabbit polyclonal anti-GSTP1 (1:1000), followed by incubation with 1:2000 HRP-conjugated anti-rabbit IgG secondary antibody in blocking solution, for 1 h at 4°C. After rinsing, immunoreactive bands were visualized by ECL. The relative densities of the immunoreactive bands were determined and normalized with respect to β-actin, using a semiquantitative densitometric analysis. Data are mean ± SD of 4 different experiments. **P < 0.001, AD vs. the respective Wt .

In Figure 2A and B the RT-PCR and WB analyses of PPAR β/δ in the neocortex of Wt and Tg mice at the age of 3, 9, and 18 mo are shown. It is possible to observe an increase of the transcription factor during normal and pathological aging. When comparing the 2 genotypes, upregulation of PPAR β/δ mRNA (at 3 mo) and of respective protein levels (at all ages) in Tg neocortex is detected. PPAR β/δ immunofluorescence in 18-mo-old samples shows a prevalent, perinuclear localization in Wt cortical neurons, while appearing more concentrated in discrete peri- and intra-nuclear regions in the Tg animals (Fig. 2C).

Figure 2. PPARβ/δ expression in Wt and Tg animals at different ages. (A) Real-time PCR in 3-, 9-, and 18-mo cortices for peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor (PPARβ/δ). The gene expressions were quantified in a 2-step RT-PCR. Complimentary DNA was reverse transcribed from total RNA samples using High-Capacity cDNA Reverse Trancription Kit. PCR products were synthesized from cDNA using the TaqMan universal PCR master mix and Assays on Demand gene expression reagents for mouse PPARβ/δ (Assay ID: Mm01305432-m1). Measurements were made using the ABI Prism 7300HT sequence detection system. As reference, TBP gene expression assay was used. Results represent normalized PPARβ/δ mRNA amounts relative to 3 mo healthy tissue using the 2-ΔΔCt method. Data are mean ± SD of 4 different experiments. **P < 0.001, AD vs. the respective Wt. (B) Western blotting analysis for PPARβ/δ. SDS-PAGE was performed running samples (20 μg protein) on 7.5–15% polyacrylamide denaturing gels. Protein bands were blotted onto polyvinylidene fluoride sheets. Non-specific binding sites were blocked for 1 h at RT with 5% (w/v) non-fat dry milk in TBS-T. Membranes were incubated overnight at 4°C with rabbit polyclonal anti-PPARβ/δ (1:1000), followed by incubation with 1:2000 HRP-conjugated anti-rabbit IgG secondary antibody in blocking solution, for 1 h at 4°C. After rinsing, immunoreactive bands were visualized by ECL. The relative densities of the immunoreactive bands were determined and normalized with respect to β-actin, using a semiquantitative densitometric analysis. Data are mean ± SD of 4 different experiments. **P < 0.001, AD vs. the respective Wt. (C) PPARβ/δ immunolocalization in 18-mo Wt and Tg brain sections. Three Tg mice and 3 Wt littermates for each age considered were deeply anesthetized before rapid killing by transcardial perfusion. Mice were perfusion-fixed, and brains were paraffin-embedded. Sagittal brain sections from Tg and Wt animals were deparaffinized and incubated with PBS containing 0.01% trypsin, for 10 min at 37° and processed for the antigen-retrieval procedure, using a microwave oven operated at 720 W. After cooling, slides were transferred to PBS containing 4% BSA for 2 h at RT, then incubated overnight at 4°C with rabbit polyclonal anti-PPARβ/δ (1:100). Sections were thoroughly rinsed with PBS, then incubated for 2 h at RT with goat anti-rabbit IgG Alexafluor 488/546 conjugated diluted 1:2000 in blocking solution. Controls were performed in parallel by omitting the primary antibody. Slides were observed at florescence microscope AXIOPHOT Zeiss microscope equipped with Leica DFC 350 FX camera. Image acquisition was performed with Leica IM500 program. Bar = 15 μm.

Since we previously demonstrated26,27 that PPAR β/δ activation results in a decrease of the BDNF-specific receptor, TrkB full-length (TrkBfl), RT-PCR, and WB analyses for TrkBfl and its truncated form (TrkB-t) were performed (Fig. 3A–C). Levels of mRNA (including both full-length and truncated forms) display no genotype-based differences, while significantly decreasing at the latest stage considered. On the other hand, WB results of TrkBfl and TrkB-t show different patterns depending on the age and genotype. TrkBfl protein levels progressively decrease during pathological aging and are consistently lower in Tg animals than in Wt. By contrast, the truncated form significantly increases with age, being always more abundant in Tg than in Wt cortices. Immunofluorescence (Fig. 3D) shows a decrease in Trkfl positivity, particularly at neuritic level in 9-mo-old Tg animals.

Figure 3. TrkB expression in Wt and Tg cortices at different ages. (A) Real-time PCR in 3-, 9-, and 18-mo cortices for TrkBfl. The gene expressions were quantified in a 2-step RT-PCR. Complimentary DNA was reverse transcribed from total RNA samples using High-Capacity cDNA Reverse Trancription Kit. PCR products were synthesized from cDNA using the TaqMan universal PCR master mix and Assays on Demand gene expression reagents for mouse TrkB (Assay ID: Mm00435422-m1). Measurements were made using the ABI Prism 7300HT sequence detection system. As reference TBP gene expression assay was used. Results represent normalized TrkB mRNA amounts relative to 3-mo healthy tissue using the 2-ΔΔCt method. Data are mean ± SD of 4 different experiments. +P < 0.01, 9 mo vs. 18 mo, both Wt and Tg. (B) Western blotting analysis for TrkBfl SDS-PAGE was performed running samples (20 μg protein) on 7.5–15% polyacrylamide denaturing gels. Protein bands were blotted onto polyvinylidene fluoride sheets. Non-specific binding sites were blocked for 1 h at RT with 5% (w/v) non-fat dry milk in TBS-T. Membranes were incubated overnight at 4°C with rabbit polyclonal anti-TrkBfl (1:200), followed by incubation with 1:2000 HRP-conjugated anti-rabbit IgG secondary antibody in blocking solution, for 1 h at 4°C. After rinsing, immunoreactive bands were visualized by ECL. The relative densities of the immunoreactive bands were determined and normalized with respect to β-actin, using a semiquantitative densitometric analysis. Data are mean ± SD of 4 different experiments. **P < 0.001, AD vs. the respective Wt. (C) Western blotting analysis for TrkBt. Membranes were incubated overnight at 4°C with rabbit polyclonal anti-TrkB-t (1:200), followed by incubation with 1:2000 HRP-conjugated anti-rabbit IgG secondary antibody in blocking solution for 1 h at 4°C. After rinsing, immunoreactive bands were visualized by ECL. The relative densities of the immunoreactive bands were determined and normalized with respect to β-actin, using a semiquantitative densitometric analysis. Data are mean ± SD of 4 different experiments. **P < 0.001, AD vs. the respective Wt. (D) Immunolocalization in 9 mo Wt and Tg brain sections. Three 9 Tg mice and 3 Wt littermates, 9 mo of age were deeply anesthetized before rapid killing by transcardial perfusion. Mice were perfusion-fixed, and brains were paraffin-embedded. Sagittal brain sections from Tg and Wt animals were deparaffinized and incubated with PBS containing 0.01% trypsin, for 10 min at 37° and processed for the antigen-retrieval procedure, using a microwave oven operated at 720 W. After cooling, slides were transferred to PBS containing 4% BSA for 2 h at RT, then incubated overnight at 4°C with rabbit polyclonal anti-TrkB (1:50). Sections were thoroughly rinsed with PBS, then incubated for 2 h at RT with goat anti-rabbit IgG Alexafluor 488/546 conjugated diluted 1:2000 in blocking solution. Controls were performed in parallel by omitting the primary antibody. Slides were observed at florescence microscope AXIOPHOT Zeiss microscope equipped with Leica DFC 350 FX camera. Image acquisition was performed with Leica IM500 program. Bar = 50 μm.

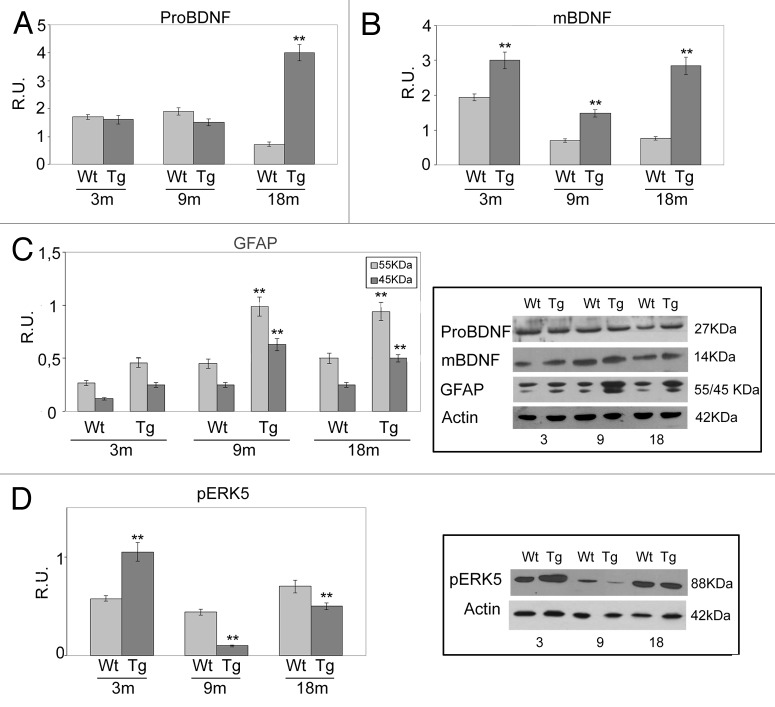

Regarding BDNF, particular attention was devoted to its immature form (pro-BDNF), owing to its negative effects on cell survival.37 This protein strongly increases in Tg animals at 18 mo, reaching significantly higher levels with respect to Wt. A partially different pattern is displayed by the mature form (mBDNF), which decreases during aging in Wt mice (Fig. 4A and B); in the Tg neocortex, mBDNF increases starting from 3 mo (Fig. 4A and B) and constantly displays higher levels that in its Wt counterpart. These data are probably related to an amyloid-related astroglia-derived neurotrophin secretion, previously described.38-40 In agreement, the WB analysis for the astrocyte marker GFAP on Wt and Tg cortices (Fig. 4C) shows a significant increase of the protein in Tg samples, starting from 9 mo, thus suggesting the ongoing of astrogliosis. Figure 4D of the same figure shows WB analysis for the activated form of ERK5, known to be involved in the neuronal survival pathway mediated by TrkBfl-BDNF. At 3 mo p-ERK5 is significantly more abundant in Tg animals than in Wt. At 9 mo, a strong decrease of the activated protein is observed in both genotypes, particularly dramatic in Tg neocortex, where its levels are significantly lower than in the respective Wt. At the latest age considered, the concentration of p-ERK5 is still decreased in the Tg animals, while it appears at the same level of the Wt 3-mo animals in 18-mo Wt genotype.

Figure 4. BDNF levels in Wt and Tg cortices at different ages. (A and B) pro-BDNF and mBDNF expression, respectively, in Wt and Tg cortices at different ages. SDS-PAGE was performed running samples (20 μg protein) on 7.5–15% polyacrylamide denaturing gels. Protein bands were blotted onto polyvinylidene fluoride sheets. Non-specific binding sites were blocked for 1 h at RT with 5% (w/v) non-fat dry milk in TBS-T. Membranes were incubated overnight at 4°C with rabbit polyclonal anti-BDNF (1:100) (able to recognize both pro and mature BDNF forms), followed by incubation with 1:2000 HRP-conjugated anti-rabbit IgG secondary antibody in blocking solution for 1 h at 4°C. After rinsing, immunoreactive bands were visualized by ECL. The relative densities of the immunoreactive bands were determined and normalized with respect to β-actin, using a semiquantitative densitometric analysis. Data are mean ± SD of 4 different experiments. **P < 0.001, AD vs. the respective Wt. (C) Western blotting analysis for the astrocyte marker GFAP in Wt and Tg cortices at different ages. Membranes were incubated overnight at 4°C with rabbit polyclonal anti-GFAP (1:200) followed by incubation with 1:2000 HRP-conjugated anti-rabbit IgG secondary antibody in blocking solution, for 1 h at 4°C. After rinsing, immunoreactive bands were visualized by ECL. The relative densities of the immunoreactive bands were determined and normalized with respect to β-actin, using a semiquantitative densitometric analysis. Data are mean ± SD of 4 different experiments. **P < 0.001, AD vs. the respective Wt. (D) Western blotting analysis for p-ERK5 in Wt and Tg cortices at different ages. Membranes were incubated overnight at 4°C with rabbit polyclonal anti-p-ERK5 (1:200),followed by incubation with 1:2000 HRP-conjugated anti-rabbit IgG secondary antibody in blocking solution, for 1 h at 4°C. After rinsing, immunoreactive bands were visualized by ECL. The relative densities of the immunoreactive bands were determined and normalized with respect to β-actin, using a semiquantitative densitometric analysis. Data are mean ± SD of 4 different experiments. **P < 0.001, AD vs. the respective Wt.

It is known that pro-BDNF detrimental effects on cell survival are mediated by the aspecific neurotrophin receptor p75NTR, which interacts with sortilin, resulting in cell death.37 Moreover, it is also known that pro-BDNF stimulates the processing of p75NTR by α- and γ-secretases, yielding a 20-kDa intracellular domain (ICD) that, upon translocation to the nucleus, triggers a delayed apoptosis. Therefore, as ICD and pro-BDNF are both mediators of apoptosis,41 we investigated the levels of p75NTR and ICD, in the neocortex of Wt and Tg mice (Fig. 5A and B). Interestingly, the ratio ICD/ p75 NTR is much higher in Tg vs. Wt animals at all stages and increases with aging (Fig. 5C). TUNEL analysis supports this notion, since apoptotic nuclei and chromatin margination are more frequently detected in Tg cortices than in their Wt counterparts, starting from 9 mo (Fig. 5D).

Figure 5. p75NTR levels in Wt and Tg cortices at different ages. (A) Western blotting analysis for p75.NTR SDS-PAGE was performed running samples (20 μg protein) on 7.5–15% polyacrylamide denaturing gels. Protein bands were blotted onto polyvinylidene fluoride sheets. Non-specific binding sites were blocked for 1 h at RT with 5% (w/v) non-fat dry milk in TBS-T. Membranes were incubated overnight at 4 °C with rabbit polyclonal anti- p75NTR (1:500), followed by incubation with 1:2000 HRP-conjugated anti-rabbit IgG secondary antibody in blocking solution, for 1 h at 4 °C. After rinsing, immunoreactive bands were visualized by ECL. The relative densities of the immunoreactive bands were determined and normalized with respect to β-actin using a semiquantitative densitometric analysis. Data are mean ± SD of 4 different experiments. **P < 0.001, AD vs. the respective Wt. (B) Western blotting analysis for ICD. Membranes were incubated overnight at 4°C with rabbit polyclonal anti- p75.NTR (1:500), (able to recognize also the cleaved p75NTR form), followed by incubation with 1:2000 HRP-conjugated anti-rabbit IgG secondary antibody in blocking solution, for 1 h at 4°C. After rinsing, immunoreactive bands were visualized by ECL. The relative densities of the immunoreactive bands were determined and normalized with respect to β-actin, using a semiquantitative densitometric analysis. Data are mean ± SD of 4 different experiments. **P < 0.001, AD vs. the respective Wt. In (C) the graphic representation of the ratio ICD/p75NTR. In (D) Tunel assay on 9- and 18-mo Wt and Tg cortices paraffin-embedded sections were de-waxed in xylene, rehydrated in descending concentration of ethanol, and rinsed in PBS; sections were then subjected to 350 W microwave irradiation in 0.1 M citrate buffer pH 6.0 for 5 min for permeabilization and washed in PBS. Sections were incubated with TdT and fluorescein-labeled dUTP in TdT buffer in a dark humid chamber at 37 °C for 60 min. Negative controls were performed omitting TdT. Slides were mounted with Vectashield Mounting Medium and were observed at florescence microscope AXIOPHOT Zeiss microscope equipped with Leica DFC 350 FX camera. Image acquisition was performed with Leica IM500 program. Bar = 40 μm.

Discussion

Oxidative stress is present early in the pathogenesis of Alzheimer disease,17 and overproduction of reactive oxygen species (ROS) induces excitotoxicity, neuroinflammation, neuronal death, and defects in glial cells.42 However, the biological role of ROS has recently been better elucidated, and ROS have been recognized as ubiquitous endogenous signaling molecules.43 Moderate increase of ROS was shown to act as a molecular signal exerting downstream effects that ultimately induce endogenous defense mechanisms, culminating in enhanced stress resistance and increased life span.44Specific targets for a balanced ROS regulation are peroxisome-proliferator-activated receptors (PPARs). The 3 PPAR isoforms (α, β/δ and γ) are members of the nuclear receptors superfamily, which are expressed throughout the brain at different levels and localizations.25 Since we have previously demonstrated that PPAR β/δ is a crucial factor in neuronal maturation and in BDNF pathway regulation27 and the oxidative stress mediator 4-HNE is an intracellular agonist of PPAR β/δ),14 we decided to study the expression of this nuclear receptor and of 4-HNE adducts during aging and in AD in relation to BDNF pathway. Particularly, since a moderate increase of ROS was shown in neocortex compared with hippocampus,17,22 our study were focused on this former brain area in Wt and Tg mice. We observed during normal aging and in AD conditions a parallelism between the increase of PPAR β/δ and of HNE adducts, suggesting a possible activation of the nuclear receptor that is known to modulate the BDNF pathway. In agreement, we observed a decrease of TrKBfl starting from 3 mo of age in Tg animals with the concomitant increase of the ratio of ICD/p75 NTR; pro-BDNF appears significantly increase at 18 mo in Tg animals. The level of expression of these proteins with normal aging is interesting; in fact, TrkBfl and p75 NTR appear decreased in favor of their truncated counterpart, thus indicating that the same mechanisms may act during aging and AD, but with different timing.

PPARβ/δ seems to works as sensor of oxidative stress, this phenomenon being apparent at 3 mo age in Tg mice, typically characterized by the appearance of oxidative stress,17-22 even though in the present study this event is not correlated with cell death, as apoptotic nuclei are not detected by TUNEL analysis at this age. Therefore, it appears that in the neocortex at 3 mo age, the increased levels of PPAR β/δ and the absence of an increase of 4-HNE adducts protect this brain area from the early perturbation of the redox status. These data are further supported, in neocortex, by the BDNF pathway analysis: in fact, although at 3 mo a decrease of TrkBfl and an increase of TrkB-t and of ICD/p75NTR ratio are observed with respect to Wt animals, a concomitant upregulation of p-ERK5 and BDNF levels were apparent, indicating the activation of a survival pathway and suggesting that a compensatory response to an early perturbation of the physiological status was acting in the neocortex, as previously described for peroxisomal proteins by us in the same animal model.17 On the other hand, an increase of mBDNF is observed at any age considered in the Tg mice in agreement with previous observations in APP23 transgenic mice, where higher BDNF contents were observed in the cortex.38-40 These findings are probably related to an amyloid-related glia-derived neurotrophin secretion,38-40 supported in our experimental conditions by the WB analysis for the astrocyte marker GFAP (Fig. 4C), where a significant increase of the protein in Tg samples, starting from 9 mo, is observed, thus suggesting the ongoing of astrogliosis.

It is known that Tg2576 mice develop amyloid plaques and declining cognitive functions starting from 6 mo of age,45 so in our 9- and 18-mo-old mice the AD was full blown, and higher levels of oxidative stress markers and apoptotic nuclei are observed. At these times an increase of 4-HNE adducts and PPARβ/δ and pro-BDNF levels were observed, particularly at 18 mo, suggesting a detrimental effects of the concomitant increase of 4-HNE and PPAR β/δ, pro-BDNF on cell survival. In addition the analysis of BDNF pathway shows a decrease of p-ERK5 starting at 9 mo in Tg mice, suggesting an impairment of pro-survival signaling mediated by BDNF, further supported by the TUNEL analysis.

Overall, it appears that the possible detrimental role of PPAR β/δ in AD depends on the oxidative stress level and particularly on the physiological/pathological levels of HNE adducts. These data may be useful for further studies on the use of PPARβ/δ antagonist as possible adjuvant for AD therapy.

Conclusion

It has become clear that neuroprotective strategies should accurately regulate the ROS levels to avoid either too-high or too-low ROS concentrations. Therefore, a protective drug should not just scavenge ROS as much as possible, but also normalize the disease-evoked ROS deregulation.

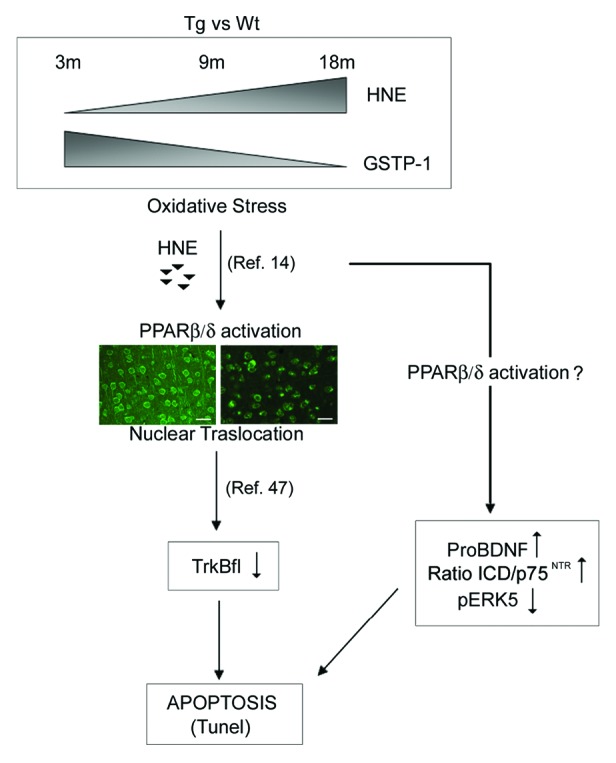

This work highlights the level of HNE during aging and, particularly in neurodegeneration, plays a crucial role in PPARβ/δ/BDNF signaling, suggesting a further mechanism of oxidative action on cell survival, as proposed in Figure 6, which shows a schematic representation depicting the interactions between the different molecular intermediates studied. The scheme proposes that the increase of oxidative stress activates, by 4-HNE, PPARβ/δ, which, in turn, triggers the decrease of TrkBfl. On the other hand, the oxidative stress, through a not well-identified pathway (PPARβ/δ-dependent?), increases pro-BDNF and the ratio ICD/p75NTR with concomitant increase of neuronal death.

Figure 6. Schematic representation depicting the interactions between the different molecular intermediates studied. The scheme proposes that the increase of oxidative stress activates, by 4-HNE, PPARβ/δ, which, in turn, triggers the decrease of TrkBfl. On the other hand, the oxidative stress, through a not well-identified pathway (PPARβ/δ-dependent?), increases pro-BDNF and the ratio ICD/p75NTR with concomitant increase of neuronal death.

Furthermore it appears interesting to study, in future work, the effects PPARβ/δ antagonist in counteracting this pathway.

Materials and Methods

Materials

DEPC water and Trizol reagent were purchased from Life Technologies. Triton X-100, sodium dodecylsulfate (SDS), Tween20, bovine serum albumine (BSA), nonidet P40, sodium deoxycolate, ethylen diamine tetraacetate (EDTA), phenylmethanesulphonylfluoride (PMSF), sodium fluoride, sodium pyrophosphate, ortovanadate, leupeptin, aprotinin, pepstatin, NaCl, polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) sheets were all purchased from Sigma Chemical Co.; ECL kit was from Biorad Laboratories; Vectashield was purchased from Vector Laboratories Inc. All other chemicals were of the highest analytical grade.

Animals

Heterozygous female Tg2576 mice (Tg)29 and wild-type (Wt) littermates were used for all experiments. Male mice (C57B6 × SJL), hemizygous for human AβPP695 and expressing the human AβPP 695 with the double mutation K670N and M671L (FADSwedish mutation), were purchased from Taconic Farms, Inc. The Tg2576 colony is maintained by breeding hemizygous transgenic male with female B6SJLF1 mice, and the genotyping is performed by established methods (Taconic PCR protocol).

The experiments were performed in accordance with the European Communities Council Directive of 24 November 1986 (86/609/EEC). Formal approval to conduct the experiments described was obtained from the Italian Ministry of Health (D.L.vo 116/92; Prot. No.155-VI-1.1.). All efforts were made to minimize the number of animals used and their suffering.

Real-time PCR and western blotting

For real-time PCR (RT-PCR) and western blotting (WB) analyses, Tg and Wt female mice age 3-, 9-, and 18-mo-old were used. Six animals from each group were killed by cervical dislocation; brains were rapidly excised on an ice-cold plate and sagittally cut into 2 halves to be used for RT-PCR and WB, respectively. The neocortices and hippocampi were dissected out from each half, and 3 pools of 2 hippocampi or neocortices were obtained.

RT-PCR

Total cellular RNA was extracted by Trizol Reagent, according the manufacturer’s instructions. The total RNA concentration was determined spectrophotometrically in RNase-free water. The gene expressions were quantified in a 2-step reverse transcription- polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR). Complimentary DNA was reverse transcribed from total RNA samples using High-Capacity cDNA Reverse Trancription Kit (Life Technologies). PCR products were synthesized from cDNA using the TaqMan universal PCR master mix and Assays on Demand gene expression reagents for mouse PPARβ/δ and TrkB (Assay ID: Mm01305432-m1 and Mm00435422-m1), (Life Technologies). Measurements were made using the ABI Prism 7300HT sequence detection system, according to the manufacturer’s protocol. As reference, TBP gene expression assay was used. Results represent normalized PPARβ/δ and TrkB mRNA amounts relative to 3-mo healthy tissue using the 2-ΔΔCt method.46 Data are mean of 4 independent experiments.

Western blotting

Protein extraction was performed by homogenizing tissue in lysis buffer (320 mM sucrose, 50 mM NaCl, 50 mM Tris–HCl, pH 7.5, 1% Triton X-100, 0.5 mM sodium orthovanadate, 5 mM β-glycerophosphate, 1% protease inhibitor), incubating on ice for 30 min. Homogenates were then centrifuged at 13 000 g for 10 min. The total protein content of the resulting supernatant was determined using a spectrophotometric assay, according to Bradford. Samples were then diluted 3:4 in 200 mM Tris–HCl, pH 6.8, containing 40% glycerol, 20%β-mercaptoethanol, 4% sodium dodecyl phosphate (SDS), bromophenol blue.

SDS-PAGE was performed running samples (5–20 μg protein) on 7.5–15% polyacrylamide denaturing gels. Protein bands were transferred onto polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) sheets by wet electrophoretic transfer. Non-specific binding sites were blocked for 1 h at room temperature (RT) with 5% (w/v) non-fat dry milk (Bio-Rad Laboratories) in Tris-buffered saline containing 0.1% (v/v) Tween 20 (TBS-T). Membranes were incubated overnight at 4˚C with the following primary antibodies appropriately diluted in blocking solution: mouse monoclonal anti-HNE (1:400, generous gift of Prof Koji Uchida, Nagoya University), rabbit polyclonal antibodies to: GSTP-1 (1:1000, Oxford Biomedical Research), PPARβ/δ (1:1000, Novus Biologicals), TrkBfl and Trkt (1:200, SantaCruz Biotechnology), BDNF (1:100, SantaCruz), GFAP (1:200 Sigma-Aldrich), ERK5 (1:200, Millipore [Upstate]), p75NTR (1:500 Sigma-Aldrich), β-actin (1:2000 Sigma-Aldrich).

This was followed by incubation with 1:2000 HRP-conjugated anti-rabbit or anti-mouse IgG secondary antibody (SantaCruz Biotechnology) in blocking solution, for 1 h at 4˚C. After rinsing, immunoreactive bands were visualized by enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The relative densities of the immunoreactive bands were determined and normalized with respect to β-actin, using a semiquantitative densitometric analysis. Data are mean of 4 independent experiments.

Immunofluorescence

For morphological studies, 3 Tg mice and 3 Wt littermates for each age considered were deeply anesthetized with urethane (1 g/kg body weight, injected i.p.), before rapid killing by transcardial perfusion. Mice were perfusion-fixed, and brains were paraffin-embedded, as previously described.17

Serial, 5-μm-thick sagittal brain sections from Tg and Wt animals were deparaffinized and incubated with PBS containing 0.01% trypsin for 10 min at 37° then immersed in 10 mM sodium citrate buffer, pH 6.1, and processed for the antigen-retrieval procedure, using a microwave oven operated at 720 W for 10 min.17 After cooling, slides were transferred to phosphate buffered saline (PBS) containing 4% bovine serum albumine (BSA, blocking solution) for 2 h at RT, then incubated overnight at 4°C with either of the following antibodies, all diluted in blocking solution: mouse monoclonal anti-HNE (1:400, generous gift of Prof Uchida, Nagoya university, Japan), rabbit polyclonal anti-PPARβ/δ (1:100, lot number 230-107, Affinity BioReagents, ABR), rabbit polyclonal anti-TrkBfl, 1:50, (SantaCruz Biotechnology), rabbit polyclonal anti-GFAP (1:200, Sigma-Aldrich).

Sections were thoroughly rinsed with PBS then incubated for 2 h at RT with goat anti-rabbit IgG Alexafluor 488/546 conjugated or anti-mouse IgG Alexafluor 488/546 conjugated (Life Technologies), diluted 1:2000 in blocking solution. Controls were performed in parallel by omitting the primary antibody.

Slides were observed at florescence microscope AXIOPHOT Zeiss microscope equipped with Leica DFC 350 FX camera. Image acquisition was performed with Leica IM500 program.

Tunel

The TUNEL assay was performed using the In Situ Cell Death Detection Kit, Fluorescein (Roche Diagnostics Gmgh) following the manufacturer’s instructions with modifications. Briefly, paraffin-embedded sections were de-waxed in xylene, rehydrated in descending concentration of ethanol (100%, 95%, 80%, 70%), and rinsed in PBS; sections were then subjected to 350 W microwave irradiation in 0.1 M citrate buffer pH 6.0 for 5 min for permeabilization and washed in PBS. Sections were incubated with TdT and fluorescein-labeled dUTP in TdT buffer in a dark humid chamber at 37 °C for 60 min. Negative controls were performed omitting TdT. Slides were mounted with Vectashield Mounting Medium and were observed at florescence microscope AXIOPHOT Zeiss microscope equipped with Leica DFC 350 FX camera. Image acquisition was performed with Leica IM500 program.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis for RT-PCR and western blotting experiments was performed by t test. These statistical calculations were performed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) software. For all statistical analyses, P < 0.01 was considered as statistically significant.

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

Acknowledgments

This work has been supported by Relevant Interest University (RIA) fund (Prof Cimini). The Authors thank to Human Health Foundation for the support. Many of the experiments have been performed in the Research Center for Molecular Diagnostics and Advanced therapies granted by the Abruzzo Earthquacke Relief Fund (AERF).

References

- 1.Selkoe DJ. Alzheimer’s disease. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2011;3:3. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a004457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Selkoe DJ. Biochemistry and molecular biology of amyloid beta-protein and the mechanism of Alzheimer’s disease. Handb Clin Neurol. 2008;89:245–60. doi: 10.1016/S0072-9752(07)01223-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.LaFerla FM, Oddo S. Alzheimer’s disease: Abeta, tau and synaptic dysfunction. Trends Mol Med. 2005;11:170–6. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2005.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Walsh DM, Selkoe DJ. A beta oligomers - a decade of discovery. J Neurochem. 2007;101:1172–84. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2006.04426.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sayre LM, Perry G, Smith MA. Oxidative stress and neurotoxicity. Chem Res Toxicol. 2008;21:172–88. doi: 10.1021/tx700210j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Comporti M. Lipid peroxidation and biogenic aldehydes: from the identification of 4-hydroxynonenal to further achievements in biopathology. Free Radic Res. 1998;28:623–35. doi: 10.3109/10715769809065818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Catalá A. Lipid peroxidation of membrane phospholipids generates hydroxy-alkenals and oxidized phospholipids active in physiological and/or pathological conditions. Chem Phys Lipids. 2009;157:1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.chemphyslip.2008.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Uchida K, Kanematsu M, Sakai K, Matsuda T, Hattori N, Mizuno Y, Suzuki D, Miyata T, Noguchi N, Niki E, et al. Protein-bound acrolein: potential markers for oxidative stress. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:4882–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.9.4882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Friguet B, Szweda LI. Inhibition of the multicatalytic proteinase (proteasome) by 4-hydroxy-2-nonenal cross-linked protein. FEBS Lett. 1997;405:21–5. doi: 10.1016/S0014-5793(97)00148-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ferrington DA, Kapphahn RJ. Catalytic site-specific inhibition of the 20S proteasome by 4-hydroxynonenal. FEBS Lett. 2004;578:217–23. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2004.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kruman I, Bruce-Keller AJ, Bredesen D, Waeg G, Mattson MP. Evidence that 4-hydroxynonenal mediates oxidative stress-induced neuronal apoptosis. J Neurosci. 1997;17:5089–100. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-13-05089.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ji C, Amarnath V, Pietenpol JA, Marnett LJ. 4-hydroxynonenal induces apoptosis via caspase-3 activation and cytochrome c release. Chem Res Toxicol. 2001;14:1090–6. doi: 10.1021/tx000186f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Awasthi YC, Yang Y, Tiwari NK, Patrick B, Sharma A, Li J, Awasthi S. Regulation of 4-hydroxynonenal-mediated signaling by glutathione S-transferases. Free Radic Biol Med. 2004;37:607–19. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2004.05.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Coleman JD, Prabhu KS, Thompson JT, Reddy PS, Peters JM, Peterson BR, Reddy CC, Vanden Heuvel JP. The oxidative stress mediator 4-hydroxynonenal is an intracellular agonist of the nuclear receptor peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-beta/delta (PPARbeta/delta) Free Radic Biol Med. 2007;42:1155–64. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2007.01.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Heneka MT, Landreth GE. PPARs in the brain. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2007;1771:1031–45. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2007.04.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bright JJ, Kanakasabai S, Chearwae W, Chakraborty S. PPAR Regulation of Inflammatory Signaling in CNS Diseases. PPAR Res. 2008;2008:658520. doi: 10.1155/2008/658520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cimini A, Moreno S, D’Amelio M, Cristiano L, D’Angelo B, Falone S, Benedetti E, Carrara P, Fanelli F, Cecconi F, et al. Early biochemical and morphological modifications in the brain of a transgenic mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease: a role for peroxisomes. J Alzheimers Dis. 2009;18:935–52. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2009-1199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schintu N, Frau L, Ibba M, Caboni P, Garau A, Carboni E, Carta AR. PPAR-gamma-mediated neuroprotection in a chronic mouse model of Parkinson’s disease. Eur J Neurosci. 2009;29:954–63. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2009.06657.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Heneka MT, Reyes-Irisarri E, Hüll M, Kummer MP. Impact and Therapeutic Potential of PPARs in Alzheimer’s Disease. Curr Neuropharmacol. 2011;9:643–50. doi: 10.2174/157015911798376325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bhateja DK, Dhull DK, Gill A, Sidhu A, Sharma S, Reddy BV, Padi SS. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-α activation attenuates 3-nitropropionic acid induced behavioral and biochemical alterations in rats: possible neuroprotective mechanisms. Eur J Pharmacol. 2012;674:33–43. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2011.10.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sodhi RK, Singh N, Jaggi AS. Neuroprotective mechanisms of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor agonists in Alzheimer’s disease. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol. 2011;384:115–24. doi: 10.1007/s00210-011-0654-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fanelli F, Sepe S, D’Amelio M, Bernardi C, Cristiano L, Cimini A, Cecconi F, Ceru’ MP, Moreno S. Age-dependent roles of peroxisomes in the hippocampus of a transgenic mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. Mol Neurodegener. 2013;8:8. doi: 10.1186/1750-1326-8-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Braissant O, Wahli W. Differential expression of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-α, -β, and -γ during rat embryonic development. Endocrinology. 1998;139:2748–54. doi: 10.1210/endo.139.6.6049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Krémarik-Bouillaud P, Schohn H, Dauça M. Regional distribution of PPARbeta in the cerebellum of the rat. J Chem Neuroanat. 2000;19:225–32. doi: 10.1016/S0891-0618(00)00065-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Moreno S, Farioli-Vecchioli S, Cerù MP. Immunolocalization of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors and retinoid X receptors in the adult rat CNS. Neuroscience. 2004;123:131–45. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2003.08.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Di Loreto S, D’Angelo B, D’Amico MA, Benedetti E, Cristiano L, Cinque B, Cifone MG, Cerù MP, Festuccia C, Cimini A. PPARbeta agonists trigger neuronal differentiation in the human neuroblastoma cell line SH-SY5Y. J Cell Physiol. 2007;211:837–47. doi: 10.1002/jcp.20996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.D’Angelo B, Benedetti E, Di Loreto S, Cristiano L, Laurenti G, Cerù MP, Cimini A. Signal transduction pathways involved in PPARβ/δ-induced neuronal differentiation. J Cell Physiol. 2011;226:2170–80. doi: 10.1002/jcp.22552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tapia-Arancibia L, Aliaga E, Silhol M, Arancibia S. New insights into brain BDNF function in normal aging and Alzheimer disease. Brain Res Rev. 2008;59:201–20. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresrev.2008.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hsiao K, Chapman P, Nilsen S, Eckman C, Harigaya Y, Younkin S, Yang F, Cole G. Correlative memory deficits, Abeta elevation, and amyloid plaques in transgenic mice. Science. 1996;274:99–102. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5284.99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jacobsen JS, Wu CC, Redwine JM, Comery TA, Arias R, Bowlby M, Martone R, Morrison JH, Pangalos MN, Reinhart PH, et al. Early-onset behavioral and synaptic deficits in a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:5161–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0600948103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.D’Amelio M, Cavallucci V, Middei S, Marchetti C, Pacioni S, Ferri A, Diamantini A, De Zio D, Carrara P, Battistini L, et al. Caspase-3 triggers early synaptic dysfunction in a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. Nat Neurosci. 2011;14:69–76. doi: 10.1038/nn.2709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Aksenov MY, Tucker HM, Nair P, Aksenova MV, Butterfield DA, Estus S, Markesbery WR. The expression of key oxidative stress-handling genes in different brain regions in Alzheimer’s disease. J Mol Neurosci. 1998;11:151–64. doi: 10.1385/JMN:11:2:151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Xie C, Lovell MA, Xiong S, Kindy MS, Guo J, Xie J, Amaranth V, Montine TJ, Markesbery WR. Expression of glutathione-S-transferase isozyme in the SY5Y neuroblastoma cell line increases resistance to oxidative stress. Free Radic Biol Med. 2001;31:73–81. doi: 10.1016/S0891-5849(01)00553-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nunomura A, Tamaoki T, Tanaka K, Motohashi N, Nakamura M, Hayashi T, Yamaguchi H, Shimohama S, Lee HG, Zhu X, et al. Intraneuronal amyloid beta accumulation and oxidative damage to nucleic acids in Alzheimer disease. Neurobiol Dis. 2010;37:731–7. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2009.12.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Swomley AM, Förster S, Keeney JT, Triplett J, Zhang Z, Sultana R, Butterfield DA. Abeta, oxidative stress in Alzheimer disease: Evidence based on proteomics studies. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2013 doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2013.09.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hardas SS, Sultana R, Clark AM, Beckett TL, Szweda LI, Murphy MP, Butterfield DA. Oxidative modification of lipoic acid by HNE in Alzheimer disease brain. Redox Biol. 2013;1:80–5. doi: 10.1016/j.redox.2013.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Teng HK, Teng KK, Lee R, Wright S, Tevar S, Almeida RD, Kermani P, Torkin R, Chen ZY, Lee FS, et al. ProBDNF induces neuronal apoptosis via activation of a receptor complex of p75NTR and sortilin. J Neurosci. 2005;25:5455–63. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5123-04.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hellweg R, Lohmann P, Huber R, Kühl A, Riepe MW. Spatial navigation in complex and radial mazes in APP23 animals and neurotrophin signaling as a biological marker of early impairment. Learn Mem. 2006;13:63–71. doi: 10.1101/lm.2606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schulte-Herbrüggen O, Eckart S, Deicke U, Kühl A, Otten U, Danker-Hopfe H, Abramowski D, Staufenbiel M, Hellweg R. Age-dependent time course of cerebral brain-derived neurotrophic factor, nerve growth factor, and neurotrophin-3 in APP23 transgenic mice. J Neurosci Res. 2008;86:2774–83. doi: 10.1002/jnr.21704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Burbach GJ, Hellweg R, Haas CA, Del Turco D, Deicke U, Abramowski D, Jucker M, Staufenbiel M, Deller T. Induction of brain-derived neurotrophic factor in plaque-associated glial cells of aged APP23 transgenic mice. J Neurosci. 2004;24:2421–30. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5599-03.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Provenzano MJ, Minner SA, Zander K, Clark JJ, Kane CJ, Green SH, Hansen MR. p75(NTR) expression and nuclear localization of p75(NTR) intracellular domain in spiral ganglion Schwann cells following deafness correlate with cell proliferation. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2011;47:306–15. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2011.05.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mattson MP. Calcium and neurodegeneration. Aging Cell. 2007;6:337–50. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-9726.2007.00275.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Armogida M, Nisticò R, Mercuri NB. Therapeutic potential of targeting hydrogen peroxide metabolism in the treatment of brain ischaemia. Br J Pharmacol. 2012;166:1211–24. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2012.01912.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ristow M, Schmeisser S. Extending life span by increasing oxidative stress. Free Radic Biol Med. 2011;51:327–36. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2011.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lesné S, Koh MT, Kotilinek L, Kayed R, Glabe CG, Yang A, Gallagher M, Ashe KH. A specific amyloid-beta protein assembly in the brain impairs memory. Nature. 2006;440:352–7. doi: 10.1038/nature04533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) Method. Methods. 2001;25:402–8. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.D’Angelo B, Benedetti E, Di Loreto S, Cristiano L, Laurenti G, Cerù MP, Cimini A. Signal transduction pathways involved in PPARβ/δ-induced neuronal differentiation. J Cell Physiol. 2011;226:2170–80. doi: 10.1002/jcp.22552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]