In hybrid cells formed by artificial cell fusion or sexual hybridization, 2 different parental genomes are combined within one cell. Intergenomic parental conflicts may be a consequence of such a novel genomic constitution and result in genomic and epigenetic reorganization of the genomes, and even somatic elimination of some or all chromosomes from one parental species may occur. Several explanations have been proposed to account for chromosome elimination, such as difference in timing of essential mitotic processes and parent-specific inactivation of centromeres. However, the mechanism underlying the elimination of uniparental chromosomes is still poorly understood.

In order to establish a traceable live cell imaging model for chromosome instability, the group led by Qinghua Shi (in the April 15, 2014 issue of Cell Cycle1) generated human–mouse hybrid cells by combining differential fluorescence marker protein-tagged mouse NIH/3T3 and human HCT116 cells. As most of the human chromosomes are unstable in this hybrid situation, this artificial combination has been used in the past as a tool for somatic cell hybrid mapping of human sequences.2

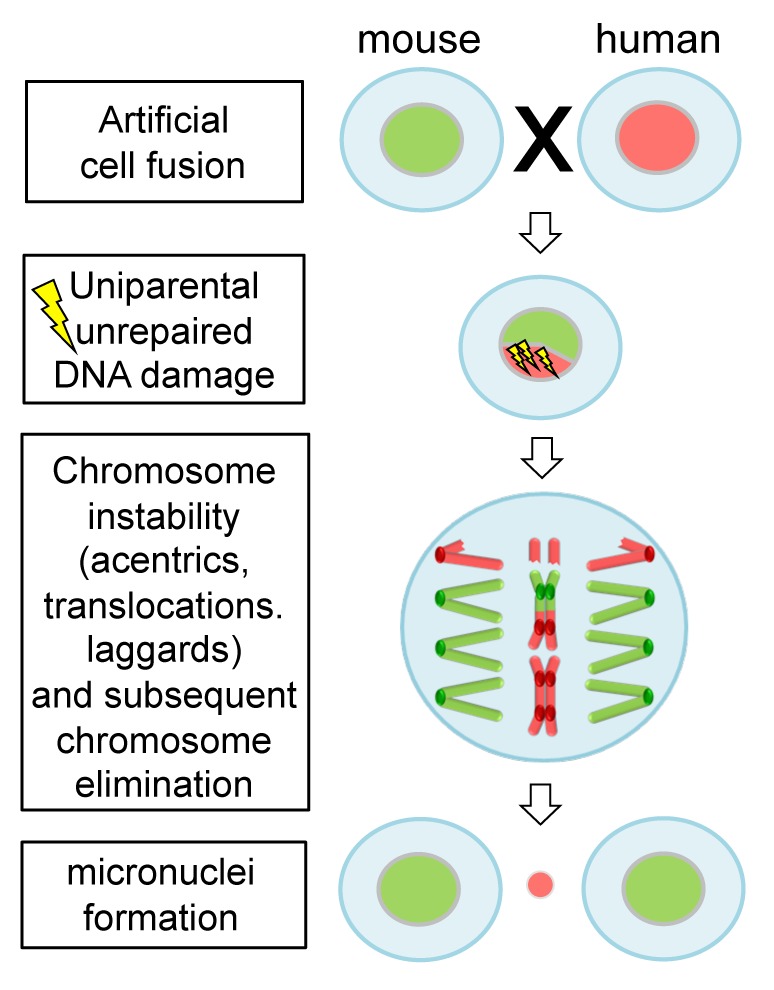

Consistent with previous findings, Wang et al.1 observed that human chromosomes in species hybrid cells are gradually and progressively eliminated during formation of clones. They showed that damaged DNA of the mouse genome was preferentially repaired during cell cycle, thus linking the observed chromosome aberrations, like acentrics and translocations, to a biased repair mechanism (Fig. 1). The progression of mitosis despite unrepaired DNA damage is unusual, as generally a DNA damage checkpoint monitors the accurate repair of DNA to maintain stability of the genome. In normal cells, if the DNA damage remains unrepaired the cells may enter cellular senescence or programmed cell death.3 Hence, the DNA damage checkpoint, but also other control mechanisms like the anaphase-promoting complex, is impaired in species hybrid cells.

Figure 1. Unrepaired DNA damage facilitates elimination of uniparental chromosomes in interspecific hybrid cells. Human–mouse hybrid cells are formed by artificial cell fusion. Deficiency in DNA damage repair of human chromosomes likely results in structural chromosome aberrations, such as acentrics, dicentrics and translocations. Consequently, progressive elimination of human chromosomes occurs.

Alternatively, degradation of chromosomes could also be triggered by asynchronous DNA replication of the 2 parental genomes. Inhibition of DNA replication induces DNA double-strand breaks and genome rearrangements.4 However, synchronous DNA replication at different time points after cell fusion of mouse and human cells was found, suggesting that the generation of most DNA damages is not related to asynchronous DNA replication.1 Given the drastic changes to the integrity of DNA during uniparental genome elimination, beside gamma histone H2AX phosphorylation, additional post-translational histone modifications might play a role in promoting and directing these changes. Heterochromatin formation and compaction of chromatin is associated with developmentally determined chromosome elimination in Sciara5 and in the mitosis-dependent process of uniparental chromosome elimination in some unstable hybrid embryos.6 The extent to which centromere inactivation or chromosome damage induced by retention of cohesin in anaphase, as suggested by Ishii et al.,7 occurs at the same time as the observed unrepaired DNA damage in human–mouse hybrid cells remains to be studied. Besides a better understanding on interaction of parental genomes in newly formed hybrids, the gained knowledge could result in establishing efficient methods for generating of doubled haploids or new species combinations for plant breeding purposes.

Wang Z, et al. Cell Cycle. 2014;13:119–130. doi: 10.4161/cc.28296.

References

- 1.Wang Z, et al. Cell Cycle. 2014;13:119–130. doi: 10.4161/cc.28296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wasmuth J. J.2001. Overview of Somatic Cell Hybrid Mapping. Current Protocols in Human Genetics. 3.1.1-3.1.4; [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Roos WP, et al. Trends Mol Med. 2006;12:440–50. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2006.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Michel B. Trends Biochem Sci. 2000;25:173–8. doi: 10.1016/S0968-0004(00)01560-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Goday C. J Cell Sci. 2002;115:4765–75. doi: 10.1242/jcs.00172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sanei M, et al. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:E498–505. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1103190108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ishii T, et al. Chromosome Res. 2010;18:821–31. doi: 10.1007/s10577-010-9158-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]