Abstract

SALL4B plays a critical role in maintaining the pluripotency of embryonic stem cells and hematopoietic stem cells. SALL4B primarily functions as a transcription factor, and, thus, its nuclear localization is paramount to its biological activities. To understand the structural basis by which SALL4B was transported and retained in the nucleus, we made a series of SALL4B constructs with deletions or point mutations. We found that K64R mutation resulted in a random distribution of SALL4B within the cell. An analysis of neighboring amino acid sequences revealed that 64KRLR67 in SALL4B matches exactly with the canonical nuclear localization signal (K-K/R-x-K/R). SALL4B fragment (a.a. 50–109) that contained KRLR was sufficient for targeting GFP-tagged SALL4B to the nucleus, whereas K64R mutation led to a random distribution of GFP-SALL4B signal within the cell. We further demonstrated that the nuclear localization was essential for transactivating luciferase reporter gene driven by OCT4 promoter, a known transcriptional target of SALL4B. Therefore, our study identifies the KRLR sequence as a bona fide nuclear localization signal for SALL4B.

Keywords: SALL4B, nuclear localization, transcription factor, stem cells

Introduciton

SALL4, a member of the SALL gene family, encodes a transcription factor containing multiple C2H2 zinc-finger domains.1-3SALL4 expression is high in stem cells and downregulated during development, and its expression is largely absent in most adult tissues.4-6 As a stem cell transcription factor, SALL4 is capable of increasing reprogramming efficiency of somatic cells to become induced pluripotent stem cells.7-9 SALL4B is a major splicing variant product of SALL4 and possesses full transcriptional activity.10,11

Mutations of SALL4 gene are associated with several developmental syndromes, including Okihiro syndrome, acro-renal-ocular syndrome, and IVIC syndrome.12 Aberrant expression of SALL4 is associated with development of various types of malignancies.13-15 It is proposed that SALL4 may have a diagnostic or prognostic value.13,16,17 For example, SALL4 expression is correlated with a poor prognosis in AML patients.18,19 SALL4 is also found to be a biomarker for a subclass of hepatocellular carcinoma with an aggressive phenotype.20

Through physical and/or functional interaction with OCT4, SOX2, and NANOG, SALL4 plays an essential role in maintaining pluripotency and self-renewal of embryonic stem cells and hematopoietic stem cells.4,5,19,21,22 SALL4 positively regulates OCT4 gene expression through binding to the conserved regulatory region of the OCT4 promoter.5,11 On the other hand, SALL4 negatively regulates its own gene expression through a feedback loop.23 Thus, SALL4 and OCT4 work in concert to regulate expression of genes of the SALL family, as well as stem cell proliferation and differentiation.23 By interaction with the nucleosome remodeling and deacetylase (NuRD) complex, SALL4 functions as a transcriptional repressor of PTEN, a major tumor suppressor.24 Our recent study reveals that SALL4B undergoes several types of post-translational modifications, and that its sumoylation is crucial for its stability, subcellular localization, and transcriptional activity.11

Nuclear localization is the prerequisite for transcription factors to regulate downstream target gene expression, and their cellular trafficking within the cell is tightly regulated. For example, nuclear import of p53 is dependent on its 3 nuclear localization sequences (NLS).25,26 A defect in p53 subcellular localization appears to be associated with several human cancers.27,28 Small proteins with molecular weight less than 40 kDa can passively diffuse into the nucleus through nuclear pore complexes.29 Soluble carrier receptors termed as “importins” and “exportins” function to transport large proteins between the cytoplasm and the nucleus by recognizing specific NLSs and nuclear export sequences of the cargo proteins. NLS is a short stretch of amino acid residues that mediate translocation of proteins into the nucleus.30 Classical NLSs are either a monopartite motif consisting of a single, short stretch of several basic amino acids or a bipartite motif consisting of 2 separate clusters of basic residues.29

We have investigated the mechanism by which SALL4B is translocated into the nucleus. Through deletion and point-mutation analyses, we observed that a fragment encompassing amino acids 50–109 is sufficient for mediating nuclear entry. A single amino acid mutation that changed lysine 64 into arginine (SALL4BK64R) disrupted specific nuclear localization of the protein. Functional analysis showed that this mutation significantly diminished transactivation activity of target genes. Sequence analysis revealed that 64KLRK67 of SALL4B exactly matches with the canonical NLS motif (K-K/R-x-K/R). Our further sequence comparisons identified that the KLRK sequence is conserved among SALL4 proteins of various species.

Results

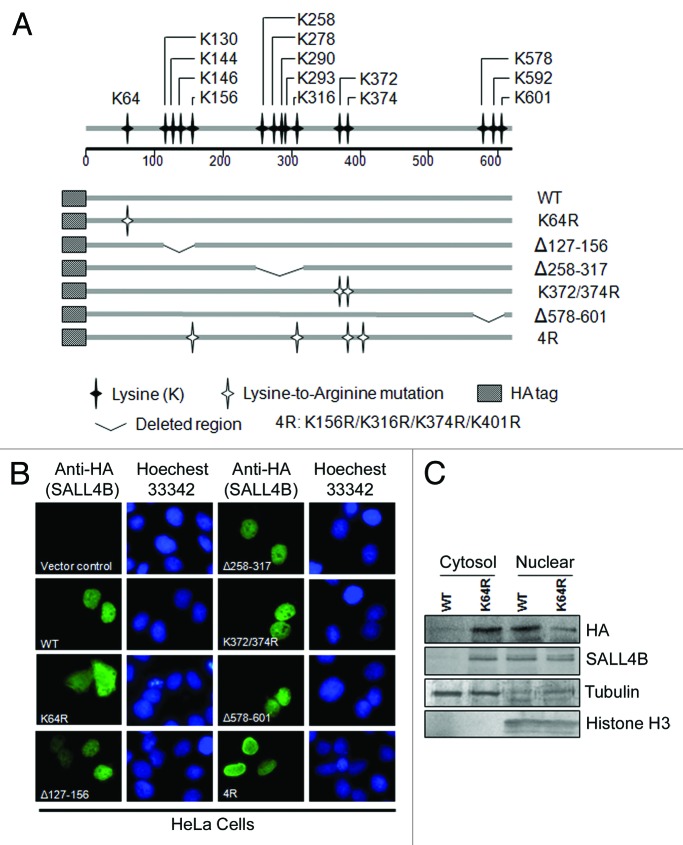

To identify possible amino acid residues essential for mediating SALL4B nuclear localization, we generated a series of mutants with sequence deletions or point mutations (Fig. 1A). We focused on lysine mutants, as NLS generally contains abundant positively charged amino acid residues.31 Mutant constructs were expressed as HA-tagged proteins. When HeLa cells were transfected with wild-type SALL4B (SALL4B-WT), HA signals, as detected by indirect fluorescent microscopy,32,33 were predominantly detected in the nucleus (Fig. 1B). Expression of SALL4B mutants with deletions of 3 lysine-rich regions (fragments of 258–317, 127–156, or 578–601) did not cause an apparent change in its subcellular localization compared with the wild-type counterpart. Moreover, mutations (4R) of those lysine residues required for SUMO-modification11 did not affect the subcellular localization either. However, when lysine 64 was mutated into arginine (K64R), HA signals were detected primarily in the cytosol (Fig. 1B). To confirm the cytosolic translocation of SALL4BK64R mutant, HeLa cells were transfected with HA-tagged SALL4B or SALL4BK64R mutants for 48 h, after which cell lysates were fractionated into cytoplasmic and nuclear fractions. Wild-type SALL4B was detected only in the nuclear fraction, whereas a significant amount of SALL4BK64R was present in the cytoplasm (Fig. 1C). Combined, our cellular and biochemical studies indicate that K64 is crucial for the nuclear localization of SALL4B.

Figure 1. Lysine 64 (K64) is crucial for nuclear localization of SALL4B in HeLa cells. (A) Schematic presentation of SALL4B and its mutant constructs. Various amino acid-substitution mutants and deletion mutants of SALL4B as depicted in the graph were constructed. K residues are represented by solid black asterisk. K to R mutation is represented by hollow asterisk. Deleted regions are represented by broken lines. 4R (K156R/K316R/K374R/K401R) denotes sumoylation-deficient mutant. (B) HeLa cells were transfected with HA-tagged SALL4B or its mutant constructs for 24 h, after which cells were fixed and stained with the anti-HA monoclonal antibody followed by FITC-conjugated anti-mouse IgGs. Control vector pcDNA3.0 was also used for transfection. Nuclei were stained with Hoechst 33342. HeLa cells were used primarily because of its relatively high efficiency of transfection and ease of manipulation for biochemical analyses. (C) HeLa cells were transfected with HA-SALL4B (WT) or HA-SALL4BK64R for 48 h, after which cell lysates were fractionated. Equal amounts of cell lysates from each fraction were blotted for HA, SALL4B, β-tubulin (primarily cytosolic), and histone H3 (primarily nuclear).

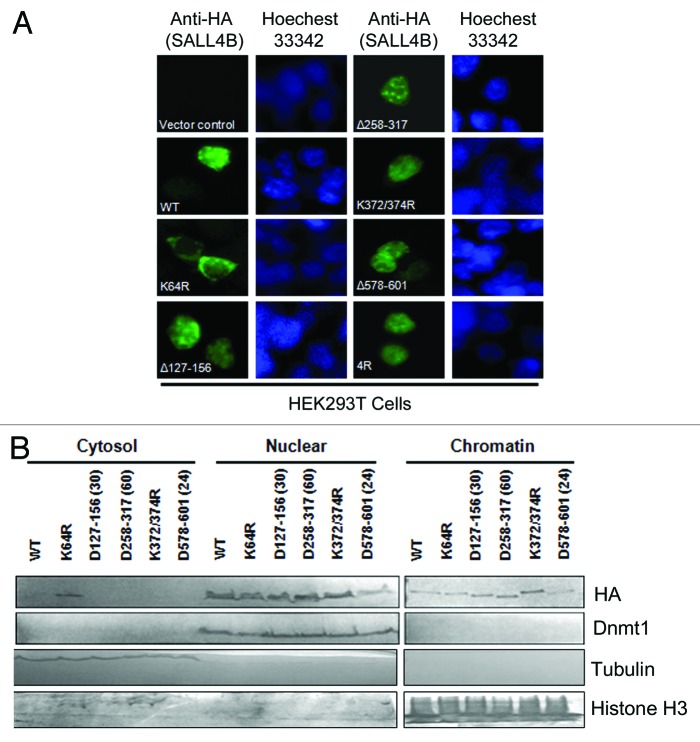

To exclude a peculiar possibility that K64-mediated nuclear localization was HeLa cell-specific, we examined the subcellular localization of SALL4B mutants, as well as wild-type SALL4B, in HEK293T cells. Cells transfected with HA-SALL4B-WT or its mutants for 24 h were fixed, stained with the antibody to the HA tag, and examined under a fluorescent microscope. Ectopically expressed SALL4B, as well as various truncation and SUMO-deficient mutants, were exclusively detected in the nuclei (Fig. 2A). In contrast, SALL4BK64R mutant protein was detected primarily in the cytoplasm. We also fractionated cells transfected with wild-type or various mutants of SALL4B into 3 fractions (cytosol, soluble nuclear, and chromatin). Equal amounts of cell lysates from each fraction were blotted with antibodies to HA and compartment markers. We observed that only SALL4BK64R mutant, but not any other mutants, exhibited a significant accumulation in the cytoplasm (Fig. 2B). Various SALL4B mutants, as well as wild-type SALL4B, were efficiently expressed (in nuclear and chromatin fractions), thus ruling out the possibility that the absence of signals in the cytoplasm were not due to a low level of expression of these proteins in the cell.

Figure 2. , SALL4BK64R displays an aberrant cytoplasmic accumulation in HEK293T cells. (A) HEK293T cells were transfected with plasmid constructs expressing HA-SALL4B or its mutants for 24 h, after which cells were fixed and stained with the anti-HA monoclonal antibody and FITC-conjugated anti-mouse IgGs. Empty vector was used for transfection as negative control. Nuclei were visualized by staining with Hoechst 33342. HEK293T cells were used because they are amenable to transfection. (B) HEK293T cells were transfected with HA-tagged SALL4B or various mutants for 48 h, after which cell lysates were separated into cytoplasmic, soluble nucleoplasmic, and insoluble chromatin fractions. Equal amounts of proteins from each fraction were blotted for HA (SALL4B), Dnmt1 (primarily nuclear), β-tubulin (primarily cytosolic), and histone H3 (primarily chromatin).

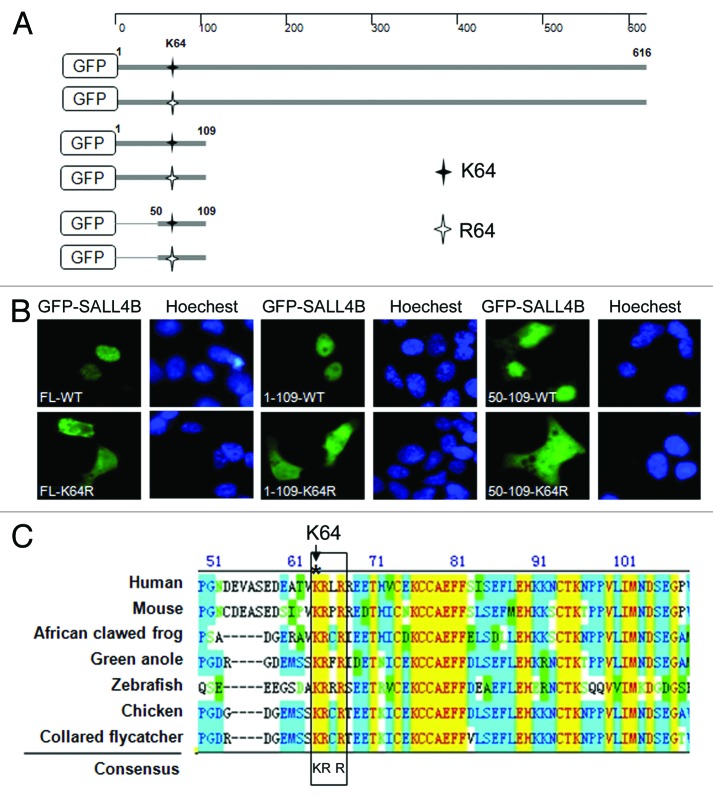

We next asked whether the N-terminus of SALL4B containing K64 is sufficient for the nuclear localization. HeLa cells were transfected with various plasmid constructs (illustrated in Fig. 3A) expressing GFP-tagged full-length SALL4B (FL-WT) and N-terminal truncation mutants (a. a. 1–109-WT and a. a. 50–109-WT) or their corresponding K64R mutants for 24 h. Ectopically expressed GFP-SALL4B and its mutant proteins were visualized via fluorescent microscopy. FL-WT and 2 N-terminal fragments (1–109-WT, and 50–109-WT) were exclusively localized to the nucleus (Fig. 3B). Significantly, substitution of K64 with R led to the cytoplasmic localization of 2 truncation mutants, as well as full-length SALL4B (Fig. 3B). These observations thus confirm that K64 is crucial for the nuclear localization of SALL4B, and that N-terminal fragment of SALL4B is sufficient for its nuclear localization.

Figure 3. KRLR within the N-terminal region of SALL4B functions as a nuclear localization signal. (A) Diagrams illustrating green fluorescent protein (GFP) fused with SALL4B or its truncated mutants (1–109 a.a. and 50–109 a.a.) with or without K64R mutation. K64 is represented by solid black asterisk. Mutant residue with K64 changed into R is represented by hollow asterisk. (B) HeLa cells were transfected with GFP-SALL4B or its truncation mutants with or without K64R mutation for 24 h, after which cells were fixed and processed for fluorescent microscopy. DNA was stained with Hoechst 33342. (C) SALL4 amino acid sequences from various species as indicated were aligned. K64 is indicated by an asterisk. Conserved NLS motifs are highlighted with a rectangular box.

We then asked whether K64 is a part of the nuclear localization signal. Sequence alignment with the classic monopartite NLS (K-K/R-x-K/R)34 revealed that 64KRLR67 sequences of SALL4B perfectly conform to the canonical NLS motif. Our further analysis showed that the short sequence of KRLR is highly conserved in SALL4 homologs/orthologs from various species (Fig. 3C), strongly supporting that the cluster of amino acids is essential for mediating nuclear localization.

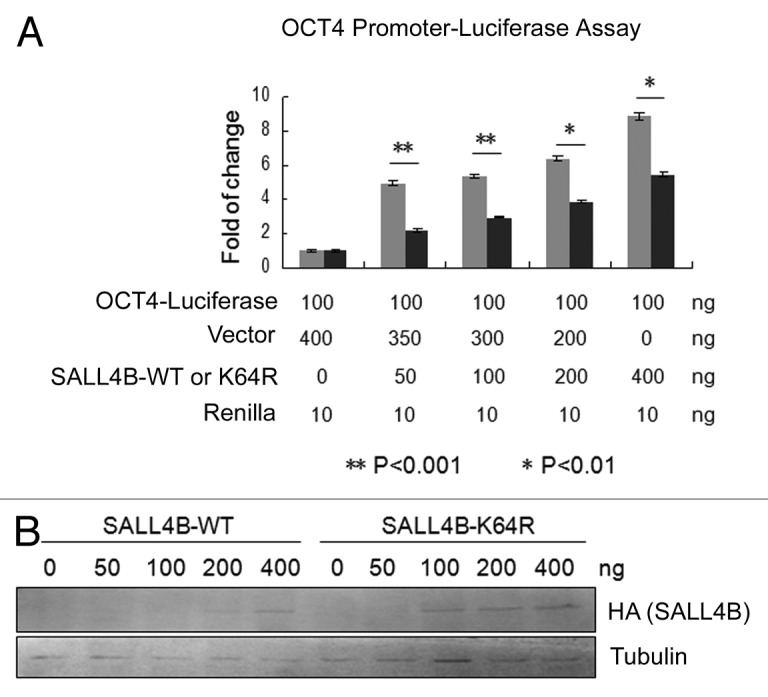

SALL4B is known to positively regulate OCT4 expression at the transcriptional level.23 To test the possibility that SALL4B nuclear localization plays an important role in mediating its biological function, we co-transfected HEK293T cells with plasmid constructs expressing firefly luciferase driven by the OCT4 promoter and wild-type SALL4B or its K64R mutant. Reporter gene assays revealed that transfection with wild-type SALL4B expression plasmid significantly activated the reporter gene activity as compared with the vector-transfected control, and that the transaction of reporter gene by SALL4B was dose-dependent (Fig. 4A and B). On the other hand, SALL4BK64R was much less efficient in trans-activating the reporter gene. Combined, these results strongly support the notion that nuclear localization of SALL4B is essential for mediating its transcriptional activity.

Figure 4. Nuclear localization of SALL4B is essential for transactivating its target gene. (A) HEK293T cells were co-transfected with a firefly luciferase reporter construct driven by the OCT4 gene promoter and various amounts of a plasmid expressing SALL4B or SALL4BK64R as indicated for 48 h. At the end of transfection, cell lysates were prepared and assayed for firefly luciferase activity. Data are expressed as fold-changes of firefly luciferase activity after normalizing with Renilla luciferase activity. Three independent experiments were performed. The symbol of ** represents P < 0.001 and the symbol of * represents P < 0.01 as determined by a 2-tailed Student t test. (B) Equal amounts of cell lysates obtained from luciferase reporter assays shown in (A) were blotted with antibodies to HA and tubulin, respectively.

Discussion

In this study, we report for the first time that SALL4B contains a monopartite NLS in the N-terminus, and that the NLS is not only essential for proper nuclear localization, but also important for transactivating target genes. The NLS (64KRLR67) of SALL4B conforms to the canonical NLS motif (K-K/R-x-K/R) and is highly conserved among proteins of the SALL4 family among various vertebrate species. A single mutation that changes K64 into R64 is sufficient to disrupt its subcellular distribution and compromises its function in vivo. K64R mutant does not completely lose its transactivating capability in the cells compared with the control (Fig. 4), which is likely due to the fact that SALL4BK64R can be still detected in the nucleus (Figs. 1 and 2). It is possible that SALL4B can form partner with other unknown nuclear proteins including SALL family members, thus entering the nucleus.

Translocation of proteins into the nucleus is energy-dependent, which relies primarily on the complex formation with importin αβ heterodimers.35,36 Importin-α contains the NLS binding site, whereas importin-β mediates translocation of proteins through the nuclear pore complex. Further studies are necessary to determine whether interaction between the conserved KRLR sequence with importin-α plays a role in mediating SALL4B nuclear localization.

It is known that SALL4 gene encodes at least 2 isoforms: namely, SALL4A and SALL4B.10,11 SALL4A is spliced from all 4 exons and encodes a protein containing 8 C2H2 zinc-finger domains. However, SALL4B lacks a large portion of exon 2 and encodes a protein containing 6 C2H2 zinc finger domains. SALL4A and SALL4B both are required for the inner cell mass formation during early embryonic development and participate in the maintenance of pluripotency of stem cells.5,6,37 Intriguingly, these 2 isoforms have overlapping, but not identical, binding sites within the ES cell genome.10 The conserved NLS of SALL4B is located in the N-terminus, and it is also presented in SALL4A. Thus, it is reasonable to propose that KRLR may be also required for mediating nuclear localization of SALL4A, as well as its transactivation function.

Deregulated expression (or activity) of transcription factors plays important roles in tumor development. In fact, transcription factors including SALL4 have been used as diagnostic and prognostic biomarkers for human malignancies.17 Several studies have shown that transcription factors can be targeted for tumor management through interrupting the formation of oncogenic complex.38,39 Recently, Gao et al. reported that an N-terminal fragment of SALL4 is capable of blocking specific interaction between SALL4 and the HDAC complex in regulating PTEN gene.40 This small peptide significantly inhibits tumor formation in xenograft models for both acute myeloid leukemia40 and aggressive hepatocellular carcinoma.20 It would be of interest to explore whether interrupting the nuclear localization of SALL4B would have an effect on suppressing cell proliferation for malignancies with aberrant expression of SALL. Mutations of SALL4 gene have been detected in patients with several developmental disorders, and these mutations either occur in the transactivation domain or cause premature translational termination.12,41,42 To date, no mutations have been reported that reside in the nuclear localization domain. It is likely that this type of mutations may severely disrupt the function of SALL4, thus leading to embryonic lethality.

Materials and Methods

Cell culture and antibodies

HEK293T and HeLa cell lines were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC). Cells were cultured in DMEM supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS, Invitrogen) and antibiotics (100 μg/ml of penicillin and 50 μg/ml of streptomycin sulfate, Invitrogen) at 37 °C under 5% CO2. Antibodies to SALL4 were purchased from Abcam. Antibodies to HA, tubulin, histone H3, Dnmt1, and NPM1 were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology Inc.

Plasmids and mutagenesis

The original SALL4B expression plasmid was described previously (Ma Y et al. Blood 2006). SALL4B cDNA was subcloned into pcDNA3 plasmid with the in-frame addition of 3-tandem HA tags in the N-terminal. Sall4B mutants with single or multiple lysine residues replaced with arginines (R) were generated using the QuickChange Lightning Multi Site-directed Mutagenesis Kit (Strategene) as described in our early study.43 SALL4B mutants with the deletion of lysine-rich region were generated by using Fusion Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kit (Thermo ScieSAntific). Individual mutations were confirmed by DNA sequencing (Biosone). Transfection of plasmids was performed using Lipofectamine 2000 according to the protocol provided by the supplier (Invitrogen).

Western blotting

Immunoblotting was essentially performed as described previously.44 SDS-PAGE was performed using the mini-gel system purchased from Bio-Rad. Fractionated proteins were transferred to PVDF membranes. After blocking in TBS/T containing 5% nonfat dry milk for 1 h, the membranes were incubated with primary antibodies overnight followed by incubation with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies (Cell Signaling Technology) for 1 h at room temperature. After thorough washing with TBS/T buffer, specific signals on the membranes were developed with an enhanced Chemiluminescent system (Pierce).

Protein fractionation

Cells washed twice with cold PBS were lysed in buffer #1 (10 mm TRIS-HCl [pH7.9], 10 mm KCl, 1.5 mm MgCl2, 1 mm DTT) and left on ice for 10 min. After centrifugation (2000 × g × 10 min), the supernatants (the cytoplasmic extract) were collected, The pellet fraction was re-suspended in buffer #2 (20 mM TRIS-HCl [pH 7.9], 1.2 M KCl, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 25% [w/v] glycerol, 0.2 mM EDTA) and left on ice for 30 min. The supernatant (the nucleoplasmic fraction) were harvested after centrifugation (16 000 × g × 10 min). The pellets were re-suspended in buffer #3 (10 mM TRIS-HCl [pH 7.9], 10 mM NaCl, 3 mM MgCl2, 1.5 mM CaCl2) containing Benzonase (Novagen). The suspension was then mixed at room temperature for 5 min followed by incubation on ice for 30 min, after which the supernatant (S1) was collected (2000 × g × 10 min). The pellets were again re-suspended into buffer #3 containing 0.25 min EDTA and incubated on ice for 30 min, after which the supernatant (S2) was collected after centrifugation (16 000 × g × 15 min). Fractions S1 and S2 were designated as the chromatin-associated protein extract.

Fluorescent microscopy

Fluorescent microscopy was performed largely as described previously.32,33 Cells seeded on chamber slides were transfected with various expression constructs for 24 h. At the end of transfection, cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS for 20 min at room temperature. After permeabilization by incubation with 0.5% Triton X-100 in PBS for 20 min, cells were incubated with 2% bovine serum albumin (BSA) in PBS for 1 h, followed by incubating overnight with the antibody to the HA tag. Cells were then incubated with FITC-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG (Invitrogen) for 1 h. Cellular DNA was stained with Hoechest (Beyotime). Fluorescence signals were detected on a Leica AF6000 fluorescence microscope.

Statistic analysis

The Student t test was used to evaluate the difference between 2 groups. A value of P < 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

Acknowledgments

We thank Miss Mengru Yuan for various assistances during the course of the work. We also thank coworkers in the laboratory for valuable discussions and suggestions. This study was supported in part by a key State project of China on iPS and stem cell research (2011ZX09102-010-04), US Public Service Awards (CA090658 and ES019929), and an NIEHS Center grant (ES000260). New York State Stem Cell Science (NYSTEM) grants C028114 to Y.M.

References

- 1.Kühnlein RP, Frommer G, Friedrich M, Gonzalez-Gaitan M, Weber A, Wagner-Bernholz JF, Gehring WJ, Jäckle H, Schuh R. spalt encodes an evolutionarily conserved zinc finger protein of novel structure which provides homeotic gene function in the head and tail region of the Drosophila embryo. EMBO J. 1994;13:168–79. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06246.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kohlhase J, Heinrich M, Liebers M, Fröhlich Archangelo L, Reardon W, Kispert A. Cloning and expression analysis of SALL4, the murine homologue of the gene mutated in Okihiro syndrome. Cytogenet Genome Res. 2002;98:274–7. doi: 10.1159/000071048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Borozdin W, Wright MJ, Hennekam RC, Hannibal MC, Crow YJ, Neumann TE, Kohlhase J. Novel mutations in the gene SALL4 provide further evidence for acro-renal-ocular and Okihiro syndromes being allelic entities, and extend the phenotypic spectrum. J Med Genet. 2004;41:e102. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2004.019505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.van den Berg DL, Snoek T, Mullin NP, Yates A, Bezstarosti K, Demmers J, Chambers I, Poot RA. An Oct4-centered protein interaction network in embryonic stem cells. Cell Stem Cell. 2010;6:369–81. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2010.02.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhang J, Tam WL, Tong GQ, Wu Q, Chan HY, Soh BS, Lou Y, Yang J, Ma Y, Chai L, et al. Sall4 modulates embryonic stem cell pluripotency and early embryonic development by the transcriptional regulation of Pou5f1. Nat Cell Biol. 2006;8:1114–23. doi: 10.1038/ncb1481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Elling U, Klasen C, Eisenberger T, Anlag K, Treier M. Murine inner cell mass-derived lineages depend on Sall4 function. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:16319–24. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0607884103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wong CC, Gaspar-Maia A, Ramalho-Santos M, Reijo Pera RA. High-efficiency stem cell fusion-mediated assay reveals Sall4 as an enhancer of reprogramming. PLoS One. 2008;3:e1955. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0001955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tsubooka N, Ichisaka T, Okita K, Takahashi K, Nakagawa M, Yamanaka S. Roles of Sall4 in the generation of pluripotent stem cells from blastocysts and fibroblasts. Genes Cells. 2009;14:683–94. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2443.2009.01301.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Neff AW, King MW, Mescher AL. Dedifferentiation and the role of sall4 in reprogramming and patterning during amphibian limb regeneration. Dev Dyn. 2011;240:979–89. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.22554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rao S, Zhen S, Roumiantsev S, McDonald LT, Yuan GC, Orkin SH. Differential roles of Sall4 isoforms in embryonic stem cell pluripotency. Mol Cell Biol. 2010;30:5364–80. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00419-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yang F, Yao Y, Jiang Y, Lu L, Ma Y, Dai W. Sumoylation is important for stability, subcellular localization, and transcriptional activity of SALL4, an essential stem cell transcription factor. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:38600–8. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.391441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yang J, Liao W, Ma Y. Role of SALL4 in hematopoiesis. Curr Opin Hematol. 2012;19:287–91. doi: 10.1097/MOH.0b013e328353c684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cui W, Kong NR, Ma Y, Amin HM, Lai R, Chai L. Differential expression of the novel oncogene, SALL4, in lymphoma, plasma cell myeloma, and acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Mod Pathol. 2006;19:1585–92. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.3800694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shuai X, Zhou D, Shen T, Wu Y, Zhang J, Wang X, Li Q. Overexpression of the novel oncogene SALL4 and activation of the Wnt/beta-catenin pathway in myelodysplastic syndromes. Cancer Genet Cytogenet. 2009;194:119–24. doi: 10.1016/j.cancergencyto.2009.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Knobloch J, Rüther U. Shedding light on an old mystery: thalidomide suppresses survival pathways to induce limb defects. Cell Cycle. 2008;7:1121–7. doi: 10.4161/cc.7.9.5793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kobayashi D, Kuribayshi K, Tanaka M, Watanabe N. SALL4 is essential for cancer cell proliferation and is overexpressed at early clinical stages in breast cancer. Int J Oncol. 2011;38:933–9. doi: 10.3892/ijo.2011.929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Oikawa T, Kamiya A, Kakinuma S, Zeniya M, Nishinakamura R, Tajiri H, Nakauchi H. Sall4 regulates cell fate decision in fetal hepatic stem/progenitor cells. Gastroenterology. 2009;136:1000–11. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.11.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ma Y, Cui W, Yang J, Qu J, Di C, Amin HM, Lai R, Ritz J, Krause DS, Chai L. SALL4, a novel oncogene, is constitutively expressed in human acute myeloid leukemia (AML) and induces AML in transgenic mice. Blood. 2006;108:2726–35. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-02-001594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jeong HW, Cui W, Yang Y, Lu J, He J, Li A, Song D, Guo Y, Liu BH, Chai L. SALL4, a stem cell factor, affects the side population by regulation of the ATP-binding cassette drug transport genes. PLoS One. 2011;6:e18372. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0018372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yong KJ, Chai L, Tenen DG. Oncofetal gene SALL4 in aggressive hepatocellular carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:1171–2. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1308785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lim CY, Tam WL, Zhang J, Ang HS, Jia H, Lipovich L, Ng HH, Wei CL, Sung WK, Robson P, et al. Sall4 regulates distinct transcription circuitries in different blastocyst-derived stem cell lineages. Cell Stem Cell. 2008;3:543–54. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2008.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yang J, Chai L, Fowles TC, Alipio Z, Xu D, Fink LM, Ward DC, Ma Y. Genome-wide analysis reveals Sall4 to be a major regulator of pluripotency in murine-embryonic stem cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:19756–61. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0809321105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yang J, Gao C, Chai L, Ma Y. A novel SALL4/OCT4 transcriptional feedback network for pluripotency of embryonic stem cells. PLoS One. 2010;5:e10766. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0010766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lu J, Jeong HW, Kong N, Yang Y, Carroll J, Luo HR, Silberstein LE, Yupoma, Chai L. Stem cell factor SALL4 represses the transcriptions of PTEN and SALL1 through an epigenetic repressor complex. PLoS One. 2009;4:e5577. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0005577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shaulsky G, Goldfinger N, Ben-Ze’ev A, Rotter V. Nuclear accumulation of p53 protein is mediated by several nuclear localization signals and plays a role in tumorigenesis. Mol Cell Biol. 1990;10:6565–77. doi: 10.1128/mcb.10.12.6565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Roth J, Dobbelstein M, Freedman DA, Shenk T, Levine AJ. Nucleo-cytoplasmic shuttling of the hdm2 oncoprotein regulates the levels of the p53 protein via a pathway used by the human immunodeficiency virus rev protein. EMBO J. 1998;17:554–64. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.2.554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Moll UM, Riou G, Levine AJ. Two distinct mechanisms alter p53 in breast cancer: mutation and nuclear exclusion. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1992;89:7262–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.15.7262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bosari S, Viale G, Roncalli M, Graziani D, Borsani G, Lee AK, Coggi G. p53 gene mutations, p53 protein accumulation and compartmentalization in colorectal adenocarcinoma. Am J Pathol. 1995;147:790–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lange A, Mills RE, Lange CJ, Stewart M, Devine SE, Corbett AH. Classical nuclear localization signals: definition, function, and interaction with importin alpha. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:5101–5. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R600026200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kalderon D, Roberts BL, Richardson WD, Smith AE. A short amino acid sequence able to specify nuclear location. Cell. 1984;39:499–509. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(84)90457-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Conti E, Uy M, Leighton L, Blobel G, Kuriyan J. Crystallographic analysis of the recognition of a nuclear localization signal by the nuclear import factor karyopherin alpha. Cell. 1998;94:193–204. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)81419-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Huang Y, Yao Y, Xu HZ, Wang ZG, Lu L, Dai W. Defects in chromosome congression and mitotic progression in KIF18A-deficient cells are partly mediated through impaired functions of CENP-E. Cell Cycle. 2009;8:2643–9. doi: 10.4161/cc.8.16.9366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wang X, Yang Y, Dai W. Differential subcellular localizations of two human Sgo1 isoforms: implications in regulation of sister chromatid cohesion and microtubule dynamics. Cell Cycle. 2006;5:635–40. doi: 10.4161/cc.5.6.2547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Boulikas T. Nuclear localization signals (NLS) Crit Rev Eukaryot Gene Expr. 1993;3:193–227. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Quimby BB, Dasso M. The small GTPase Ran: interpreting the signs. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2003;15:338–44. doi: 10.1016/S0955-0674(03)00046-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Görlich D, Kostka S, Kraft R, Dingwall C, Laskey RA, Hartmann E, Prehn S. Two different subunits of importin cooperate to recognize nuclear localization signals and bind them to the nuclear envelope. Curr Biol. 1995;5:383–92. doi: 10.1016/S0960-9822(95)00079-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sakaki-Yumoto M, Kobayashi C, Sato A, Fujimura S, Matsumoto Y, Takasato M, Kodama T, Aburatani H, Asashima M, Yoshida N, et al. The murine homolog of SALL4, a causative gene in Okihiro syndrome, is essential for embryonic stem cell proliferation, and cooperates with Sall1 in anorectal, heart, brain and kidney development. Development. 2006;133:3005–13. doi: 10.1242/dev.02457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Polo JM, Dell’Oso T, Ranuncolo SM, Cerchietti L, Beck D, Da Silva GF, Prive GG, Licht JD, Melnick A. Specific peptide interference reveals BCL6 transcriptional and oncogenic mechanisms in B-cell lymphoma cells. Nat Med. 2004;10:1329–35. doi: 10.1038/nm1134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Moellering RE, Cornejo M, Davis TN, Del Bianco C, Aster JC, Blacklow SC, Kung AL, Gilliland DG, Verdine GL, Bradner JE. Direct inhibition of the NOTCH transcription factor complex. Nature. 2009;462:182–8. doi: 10.1038/nature08543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gao C, Dimitrov T, Yong KJ, Tatetsu H, Jeong HW, Luo HR, Bradner JE, Tenen DG, Chai L. Targeting transcription factor SALL4 in acute myeloid leukemia by interrupting its interaction with an epigenetic complex. Blood. 2013;121:1413–21. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-04-424275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Miertus J, Borozdin W, Frecer V, Tonini G, Bertok S, Amoroso A, Miertus S, Kohlhase J. A SALL4 zinc finger missense mutation predicted to result in increased DNA binding affinity is associated with cranial midline defects and mild features of Okihiro syndrome. Hum Genet. 2006;119:154–61. doi: 10.1007/s00439-005-0124-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kohlhase J, Chitayat D, Kotzot D, Ceylaner S, Froster UG, Fuchs S, Montgomery T, Rösler B. SALL4 mutations in Okihiro syndrome (Duane-radial ray syndrome), acro-renal-ocular syndrome, and related disorders. Hum Mutat. 2005;26:176–83. doi: 10.1002/humu.20215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yang F, Huang Y, Dai W. Sumoylated BubR1 plays an important role in chromosome segregation and mitotic timing. Cell Cycle. 2012;11:797–806. doi: 10.4161/cc.11.4.19307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hu L, Liu X, Chervona Y, Yang F, Tang MS, Darzynkiewicz Z, Dai W. Chromium induces chromosomal instability, which is partly due to deregulation of BubR1 and Emi1, two APC/C inhibitors. Cell Cycle. 2011;10:2373–9. doi: 10.4161/cc.10.14.16310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]