Abstract

The clathrin light chain (CLC) subunits participate in several membrane traffic pathways involving both clathrin and actin, through binding the actin-organizing huntingtin-interacting proteins (Hip). However, CLCs are dispensable for clathrin-mediated endocytosis of many cargoes. Here we observe that CLC depletion affects cell migration through Hip binding and reduces surface expression of β1-integrin by interference with recycling following normal endocytosis of inactive β1-integrin. CLC depletion and expression of a modified CLC also inhibit the appearance of gyrating (G)-clathrin structures, known mediators of rapid recycling of transferrin receptor from endosomes. Expression of the modified CLC reduces β1-integrin and transferrin receptor recycling, as well as cell migration, implicating G-clathrin in these processes. Supporting a physiological role for CLC in migration, the CLCb isoform of CLC is upregulated in migratory human trophoblast cells during uterine invasion. Together, these studies establish CLCs as mediating clathrin–actin interactions needed for recycling by G-clathrin during migration.

Clathrin light chain (CLC) subunits are dispensable for clathrin-mediated endocytosis of a number of cargoes. Majeed et al. report that CLCs are however required for gyrating-clathrin-dependent recycling of inactive β1-integrins, the absence of which impairs cell migration.

Clathrin light chain (CLC) subunits are dispensable for clathrin-mediated endocytosis of a number of cargoes. Majeed et al. report that CLCs are however required for gyrating-clathrin-dependent recycling of inactive β1-integrins, the absence of which impairs cell migration.

Clathrin plays a key role in intracellular membrane traffic by polymerizing into a membrane-associated latticed coat that captures cargo during receptor-mediated endocytosis and organelle biogenesis1. The lattice-forming clathrin triskelion is composed of trimerized clathrin heavy chain (CHC) subunits, which comprise the determinants for self-assembly. The major CHC isoform (CHC17) is bound by clathrin light chain (CLC) subunits that extend half way along the triskelion leg. There are two CLCs in vertebrates (CLCa and CLCb) with characteristic tissue-specific expression. Though their cellular functions have yet to be fully defined, CLCs stabilize CHC17 trimerization2 and regulate lattice formation in vitro3. Although depletion of CHC17 globally impairs clathrin-mediated endocytosis (CME)4,5,6, the only known cargo affected by CLC depletion are certain G-protein-coupled receptors7. Uptake of transferrin receptor, epidermal growth factor (EGF) receptor, cation-independent-mannose-6-phosphate receptor and low-density lipoprotein receptor occur in the absence of CLC5,6. However, depletion of CLC effectively inhibits internalization of cargo such as bacteria and virus particles that are too large for conventional CME but require clathrin and actin for uptake8,9. CLCs are also required for internalization from villous membranes under tension on mammalian cells and from the yeast plasma membrane under turgor pressure, processes that likewise require actin10,11,12. These actin-dependent clathrin pathways involve the actin-binding proteins huntingtin-interacting protein 1 (Hip1), its related homologue Hip1R or Sla2p in yeast, all of which bind to CLCs1. The 22-residue Hip-binding region is the only sequence completely shared by CLCa and CLCb and is conserved, but not identical, in yeast CLC, suggesting a key biological function13,14,15,16.

Cell migration represents a different process involving coordination of clathrin and actin activity. Migration requires trafficking of the integrins that bind extracellular matrix17,18,19,20 through endocytic, as well as fast and slow recycling pathways17,18,19,21. Clathrin has been implicated in cell migration, as siRNA targeting CHC17 or CLC overexpression affect cell motility18,22,23,24. However, distinct roles for CHC and CLC were not addressed in these studies. The rapid recycling pathways for integrins during cell migration depend on actin and actin-modulating proteins25. Rapid endosomal recycling26,27 can be mediated by intracellular peripheral clathrin-coated structures termed ‘gyrating-clathrin’ (G-clathrin), characterized by live cell imaging of fluorescent CLC or GGA1 adaptors26,28. The potential coincidence of these pathways inspired the investigation of a role for the CLC-actin connection during the rapid recycling that occurs in cell migration that we report here.

We observe that complete loss of both clathrin subunits (by CHC17 depletion) or of CLC alone impedes cell migration, but resulting actin morphologies and focal adhesion characteristics suggest distinct roles for the clathrin subunits. Analysis of integrin trafficking reveals that CLC–Hip interactions are needed for recycling of inactive β1-integrin, whereas CHC17 but not CLC is needed for its internalization. Furthermore, disruption of CLC function significantly reduces G-clathrin structures marked by Golgi-localized gamma-adaptin ear containing Arf-binding protein 1 (GGA1), and attenuates transferrin receptor recycling. In support of a key role for CLC in cell migration, we observe upregulation of CLCb, along with other proteins involved in migration and adhesion, in trophoblast cells that invade the uterus during fetal implantation. Our combined results establish that the clathrin–actin interactions mediated by the CLC subunits are important for G-clathrin recycling of β1-integrin during cell migration and have potential significance for Hip1 upregulation in metastatic cancers.

Results

Actin and focal adhesions differ upon CLC or CHC depletion

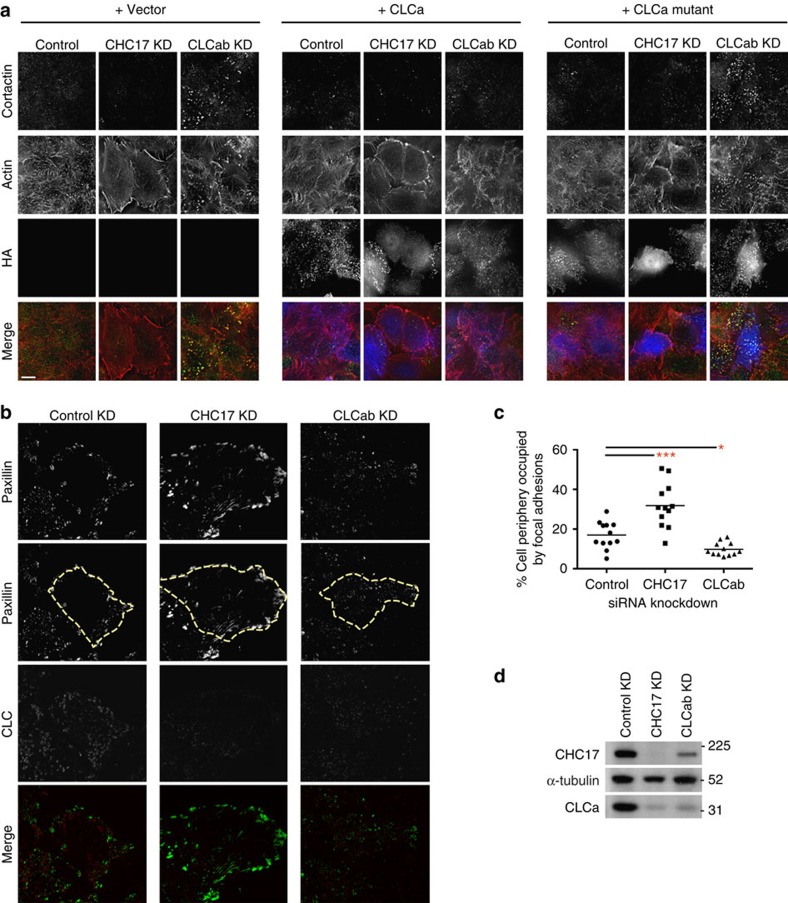

Following up our published observation that overexpression of the Hip-binding CLC fragment (residues 1–44) dramatically alters cortical cellular actin distribution13, we characterized the effects of CLC depletion on actin organization at the cell periphery. Cells were depleted of CLCs using siRNA targeting both CLCa and CLCb, or of total clathrin using siRNA targeting CHC17. During depletion, cells were co-transfected with either mutant CLCa (I38A, D25A) that does not bind Hip proteins but does bind CHC17 (ref. 13) or with WT CLCa (both siRNA-resistant and HA-tagged), or with the empty expression vector. Consistent with previous studies, CLC depletion generated short, disorganized actin structures characterized by the presence of cortactin at the tips6. This phenotype was rescued by WT CLCa, but not by mutant CLCa (Fig. 1a). CHC17-depleted cells had a completely different actin phenotype characterized by increased long actin fibres at the cell periphery. This phenotype was not reversed by expression of CLCs, which depend on CHC17 for membrane recruitment. No phenotype was seen in cells expressing the mutant CLCa without endogenous CLC depletion. These results show distinct effects of CHC17 and CLC depletion on actin morphology and extend our previous findings that CLC’s influence on actin is mediated through Hip binding.

Figure 1. CLC-depleted HeLa cells display disorganized actin fibres and reduced focal adhesions.

(a) HeLa cells treated with siRNA against CHC17, CLCab or control siRNA and transiently transfected with siRNA-resistant HA-tagged-CLCa or HA-tagged-CLCa mutant were labelled for cortactin (green in merge), actin (red) and HA (blue). In all the panels, the overlap of green and red signals is shown in yellow, scale bars, 10 μm. (b) HeLa cells transfected with siRNAs against CHC17, CLCab or control siRNA were stained for paxillin (green in merge) and CLC (red). The cell border is outlined in the second panel from the top (yellow dashed line). (c) The cell periphery occupied by focal adhesions of cells in b was measured using ImageJ to outline cells and quantify paxillin staining at the border (mean; n=12 cells from two independent experiments; *P<0.05, ***P<0.005, one-way analysis of variance followed by Newman–Keuls post hoc test). (d) HeLa cells were treated with the indicated siRNA for 72 h, harvested and subjected to immunoblotting analysis. Control, scrambled siRNA; KD, knockdown. A representative blot of many experiments is shown. Migration positions of molecular mass markers are indicated in kDa at the right of the immunoblots shown.

The changes in actin upon depletion of either clathrin subunit suggested potential correlative changes in focal adhesions resulting from these perturbations. Compared with control-treated cells, bright patches stained for the focal adhesion marker paxillin were more obvious in CHC17-depleted cells, whereas paxillin patches appeared duller and were reduced in CLC-depleted cells (Fig. 1b). Quantitative analysis revealed that 32% of the cell periphery in CHC17-depleted cells was occupied with paxillin-containing focal adhesions, compared with 17% of control and less than 10% of CLC-depleted cells (Fig. 1c). Thus, our data suggest that CLCs play a unique role in influencing focal adhesion morphology distinct from the pathway affected by depletion of both clathrin heavy and light chain subunits upon CHC17 targeting (Fig. 1d).

Loss of CLC–Hip coupling impairs cell migration

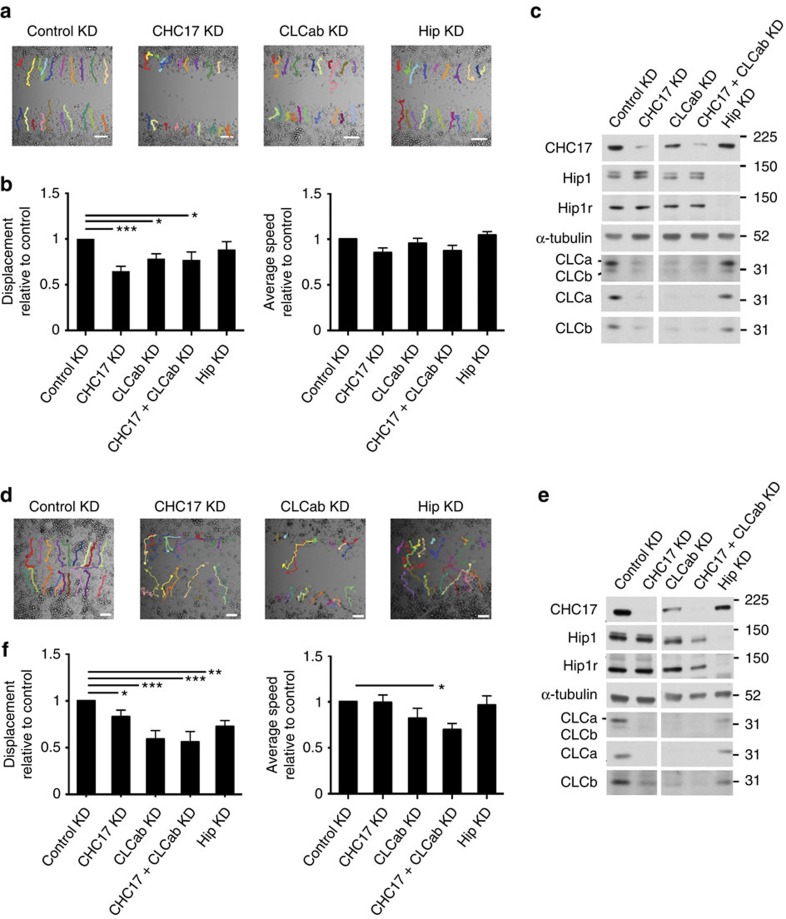

Clathrin has been implicated in cell migration18,22,23,24,29 and this has been attributed to a role in endocytosis at focal adhesions, a role in plaque formation and SCAR–WAVE binding by CHC17. Although CLC depletion has variable effects on endocytosis5,6,7, our observations (Fig. 1) that CLC influences actin and focal adhesions led us to address the role of CLC in cell migration. HeLa cells depleted of CLC or CHC17 were grown to confluency and migration was assessed in a wound-healing assay. Depletion of CHC17 impaired HeLa cell migration as measured by displacement by 35% relative to control-treated cells (Fig. 2a–c), consistent with previous reports18,24 without affecting cell speed. Migration of a HeLa cell derivative expressing SNAP-tagged CLCa30, in which whole clathrin was acutely inactivated by drug-induced crosslinking of the SNAP tag, was similarly impaired (Supplementary Fig. 1a). Notably, CLC depletion reduced HeLa cell migratory displacement by 22%, also without affecting speed (Fig. 2a–c). Depletion of the second CHC isoform CHC22, which does not influence CLC or CHC17 levels or participate in endocytosis31,32 had no effect on HeLa cell migration (Supplementary Fig. 1b,c). Cell proliferation was not significantly altered by siRNA depletion of either clathrin subunit 24–48 h or by clathrin inactivation post cell plating, indicating that wound-healing defects could be ascribed directly to altered migration (Supplementary Fig. 2a–c).

Figure 2. CHC17 or CLC depletion decreases HeLa and H1299 cell migration.

Wound-healing assays were performed in cells transfected with siRNA against CHC17, CLCab, Hip (Hip1 and Hip1R) or control siRNA. Migration across the wound was imaged in the presence of medium containing 1% serum on glass-bottomed plates using live-cell time-lapse microscopy. (a) Representative HeLa cell trajectories at end time points (24 h) are shown. The MtrackJ plugin of ImageJ was used to manually trace migratory cell tracks, marked in colour. (b) Quantitative analysis of HeLa cell relative net displacement (net displacement from the origin relative to control; left) and average speed (distance migrated per min relative to control; right) were quantified from migratory tracks (mean±s.e.m. of at least 230 cells analysed from 11 independent experiments; as in a. *P<0.05, ***P<0.005, one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Newman–Keuls post hoc test). (c) Representative immunoblots of siRNA treatments of HeLa cells as in a. (d) H1299 cell trajectories at end time points (15 h) are shown. The MtrackJ plugin of ImageJ was used to manually trace cell tracks as in a. (e) Representative immunoblots of siRNA treatments as in d. (f) Quantitative analysis of H1299 cell relative net displacement (left) and average speed (right) from migratory tracks (mean±s.e.m. of at least 100 cells analysed from five independent experiments; as in d. *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.005, one-way ANOVA followed by Newman–Keuls post hoc test). Migration positions of molecular mass markers are indicated in kDa at the right of the immunoblots shown. Scale bars, 100 μm.

In H1299 lung cancer cells, which migrate faster than HeLa cells, CHC17 depletion only reduced migration by 17%, whereas CLC depletion reduced migration by 41% relative to control cells (Fig. 2d–f), validating that the contribution of CLC to cell migration is independent of the associated decrease in CHC17 stability upon CLC depletion. As seen for HeLa, CHC or CLC depletion mainly affected H1299 cell displacement, though double depletion also affected speed (Fig. 2f) and CHC22 depletion had no effect (Supplementary Fig. 1d,e). However, Hip depletion from H1299 cells decreased cell migration by 27% (Fig. 2d–f), while having a marginal effect on HeLa cell migration. This suggests that CLC–Hip protein interaction plays a greater role in regulation of cell migration in H1299 cells compared with HeLa cells. Interestingly, H1299 cells express more Hip1 protein relative to CHC17 than HeLa cells.

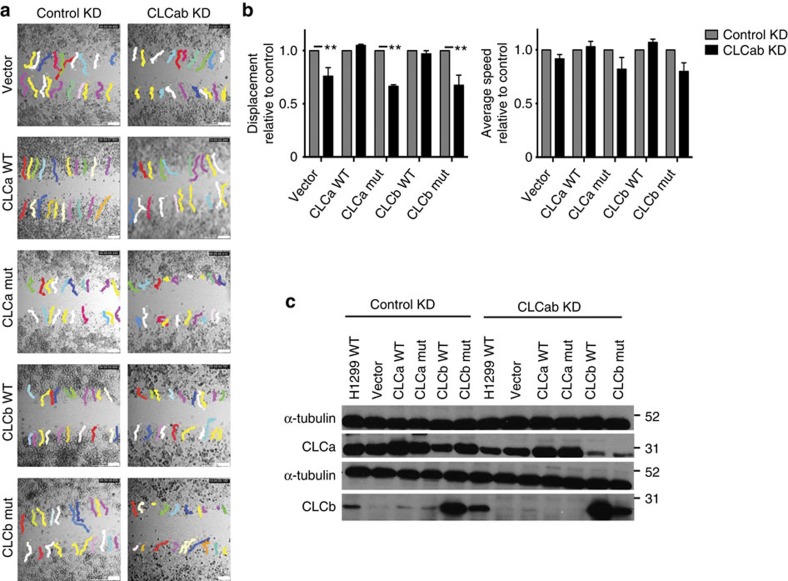

To address whether the role of CLC in migration requires association with Hip proteins, we generated H1299 and HeLa cell clones stably expressing siRNA-resistant mutant CLCa or CLCb that do not bind Hip proteins13 or siRNA-resistant WT CLCa or CLCb, using the non-coding vector as a control. Each stable transfectant was depleted of endogenous CLCa and CLCb or treated with control siRNA, and migration was compared between these two conditions for each clone. Migration defects following CLC depletion were obvious in H1299 clones with siRNA-resistant mutant CLCa or CLCb but did not occur in the clones expressing WT CLCa or WT CLCb (Fig. 3). These results were replicated in HeLa cell lines stably expressing siRNA-resistant WT or Hip-binding-deficient CLCb (Supplementary Fig. 3). We were unable to establish HeLa clones that stably express WT CLCa or mutant CLCa. These data demonstrate that CLC plays a role in cell migration that requires its binding to Hip. Migration defects caused by depletion of both CLCs were rescued by expression of WT CLCa or WT CLCb, indicating that the role in migration is a shared property of the CLC isoforms, consistent with their identical Hip-binding sequences13.

Figure 3. Hip-binding by CLC is required to rescue the migration defect induced by CLC depletion.

Wound-healing assays were performed in H1299 clones that stably expressed either empty vector, siRNA-resistant WT CLCa, siRNA-resistant WT CLCb, siRNA-resistant mutant CLCa or siRNA-resistant mutant CLCb after 72 h of treatment with siRNA targeting CLCab to deplete endogenous CLCs. Mutant (mut) CLCs are defective for Hip-binding. Migration across the wound was imaged in the presence of medium containing 1% serum using live-cell time-lapse microscopy on plastic tissue culture plates for 10 h. (a) Representative cell trajectories at end time points are shown. The MtrackJ plugin of ImageJ was used to manually trace cell tracks, marked in colour. Scale bars, 250 μm. (b) Quantitative analysis of relative net displacement (left) and relative average speed (right; mean±s.e.m. of at least 40 cells analysed from two independent experiments; as in a. **P<0.01, two-way analysis of variance followed by Bonferroni post hoc test). (c) Representative immunoblots of siRNA treatments as in a. Migration positions of molecular mass markers are indicated in kDa at the right of the immunoblots shown.

Inactive β1-integrin recycling involves CLC and G-clathrin

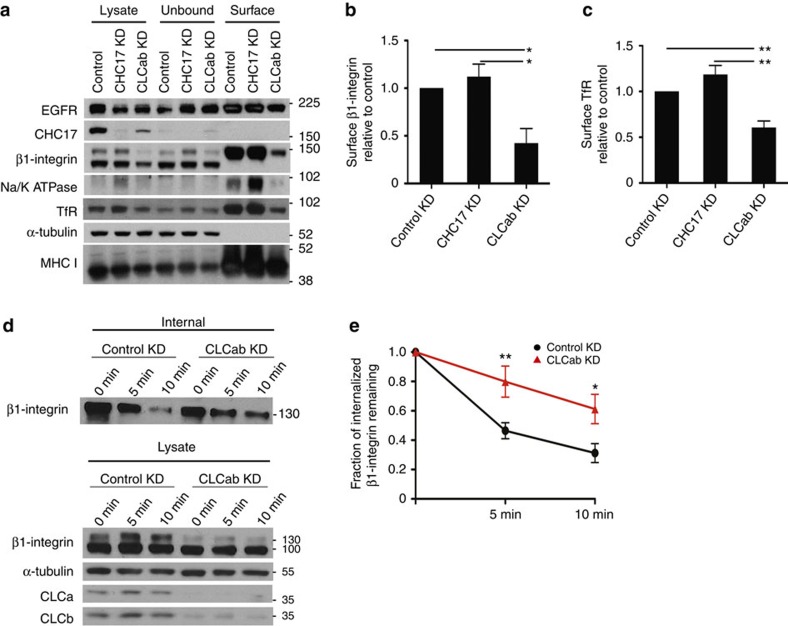

Focal adhesions and cell migration are affected by surface integrin levels17, so we assessed if these were altered by CLC depletion using cell surface biotinylation. We focused on β1-integrin, the dominant β-integrin subunit in HeLa cells, which heterodimerizes with different α-subunits to alter specificity for extracellular matrix ligands33. Biotinylated surface molecules were isolated by streptavidin binding from solubilized cells treated with siRNA, and then identified by immunoblotting. Consistent with inhibition of endocytosis, CHC17 depletion resulted in slightly increased levels of surface proteins, including β1-integrin (~\n13% increase) and transferrin receptor (~\n19% increase) (Fig. 4a–c). In contrast, CLC depletion reduced levels of several cell surface proteins, including the mature form of β1-integrin (58% reduction of upper band, note lower band is the immature form), transferrin receptor (59% reduction), EGF-receptor, major histocompatibility complex class I, and Na/K ATPase (Fig. 4a–c). CLC depletion also decreased total protein levels of β1-integrin.

Figure 4. CLC depletion reduces constitutive recycling of β1-integrin and steady state levels of other surface molecules.

(a) HeLa cells transfected with the indicated siRNAs for knockdown (KD) were biotinylated for 30 min and surface biotinylated proteins were isolated using streptavidin beads, followed by immunoblotting for the indicated proteins. (b,c) Quantification of surface levels of (b) β1-integrin and (c) transferrin receptor (TfR) from a and replicate experiments (mean±s.e.m.; n=3; *P<0.05, **P<0.01, one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Newman–Keuls post hoc test). (d) Recycling of internalized β1-integrin in control and CLCab-siRNA-treated HeLa cells. Cells were biotinylated and allowed to internalize surface proteins for 30 min at 37 °C. Surface biotin was removed by reduction and internalized proteins were chased back to the cell surface for the indicated times at 37 °C. Surface biotin was reduced again, and cells were lysed. Above: Biotinylated proteins were bound to streptavidin beads, followed by immunoblotting for β1-integrin. Below: Immunoblots of indicated proteins in total cell lysate at each time point. Representative immunoblots of one experiment (n=6). (e) Quantification of β1-integrin recycling assays as in d (mean±s.e.m.; n=6; *P<0.05, **P<0.01, two-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni post hoc test). Migration positions of molecular mass markers are indicated in kDa at the right of the immunoblots shown.

The CLC depletion phenotype was consistent with normal endocytosis coupled with impaired endosomal recycling and consequent degradation in lysosomes. Given the relevance of β1-integrin to cell migration, we focused on understanding the role of CLC in β1-integrin traffic. We performed internalization and recycling assays in control and CLC-depleted cells that were surface-labelled with biotin using a reducible crosslinker. In this assay, proteins are internalized followed by stripping of residual surface biotin. Then proteins are allowed to recycle, followed by a second surface-stripping treatment. Internalized surface proteins that do not recycle remain biotinylated. While CLC depletion reduced overall levels of β1-integrin, internalization of β1-integrin was not affected. However, after stripping, more internal β1-integrin remained in CLC-depleted cells compared with control-treated cells, indicating impaired recycling (Fig. 4d,e, and see Supplementary Fig. 4 for later time points).

There is growing evidence that inactive and active integrins are trafficked through different pathways in the cell19,21. We therefore used an antibody-based internalization and recycling assay to specifically analyse trafficking of the inactive form of β1-integrin following CLC depletion, as endocytosis of this form has been shown to be clathrin-dependent18,19. Surface-bound antibody against inactive β1-integrin was internalized and visualized after cell permeabilization. Or, residual antibody was stripped from the surface after internalization and internalized antibody allowed to recycle, followed by a second stripping step. Antibody bound to the inactive β1-integrin was taken up by the CLC-depleted cells or control-treated cells (Fig. 5a), with reduced signal for the CLC-depleted cells reflecting decreased total amounts of β1-integrin. Notably, internalized antibody remained inside CLC-depleted cells, whereas internalized antibody was recycled and lost by stripping from control-treated cells within 30 min (Fig. 5b). Thus, CLCs are not necessary for CME of inactive β1-integrins, but are involved downstream in their recycling. No antibody to inactive β1-integrin was internalized upon CHC17 depletion, as expected18,19, so recycling could not be assessed.

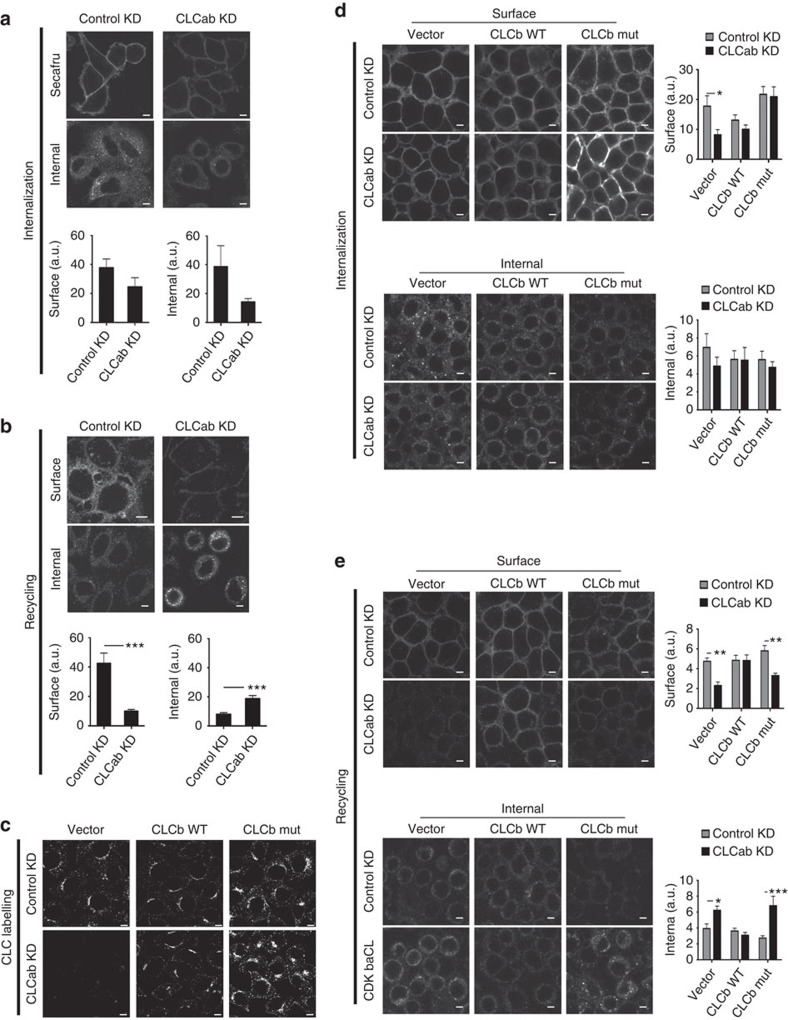

Figure 5. CLC depletion decreases recycling of inactive β1-integrin.

(a) siRNA-treated HeLa cells were allowed to internalize antibody specific for inactive β1-integrin for 30 min at 37 °C. Cells were fixed and stained with Alexafluor-conjugated secondary antibody to visualize surface integrins. For analysis of internal integrins, surface antibody was stripped by acid wash before fixation, followed by permeabilization. Quantification of surface (bottom left) and internal (bottom right) fluorescent labelling of inactive β1-integrin antibody following internalization, which are presented as raw mean fluorescent intensities (mean±s.e.m.; n=3; P=not significant, Student’s t-test). (b) Cells were treated as in a, followed by surface antibody stripping by acid washing after the 30 min internalization period. Cells were then placed at 37 °C for 30 min to chase integrins back to the cell surface. Cells were fixed and processed as in a. Quantification of surface (bottom left) and internal (bottom right) fluorescent labelling of inactive β1-integrin antibody following recycling (mean±s.e.m.; n=3; ***P<0.005, Student’s t-test). (c) HeLa clones expressing the vector, siRNA-resistant WT CLCb or siRNA-resistant mutant (mut) CLCb were treated with control or CLCab-targeting siRNA and immunostained for CLC. (d) Internalization of inactive β1-integrin antibody was assessed as in a in siRNA-treated HeLa clones that expressed the vector, siRNA-resistant WT CLCb or siRNA-resistant mutant CLCb. Quantification of surface (top right) and internal (bottom right) fluorescent labelling of inactive β1-integrin antibody following internalization (mean±s.e.m.; n=3; *P<0.05, two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Bonferroni post hoc test). (e) Recycling of inactive β1-integrin antibody was assessed as in b in siRNA-treated HeLa clones that stably expressed the vector, siRNA-resistant WT CLCb or siRNA-resistant CLCb. Quantification of surface (top right) and internal (bottom right) fluorescent labelling of inactive β1-integrin antibody following recycling (mean±s.e.m.; n=3; *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.005, two-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni post hoc test). Scale bars, 7.5 μm for all panels. a.u., arbitrary unit.

Following depletion of endogenous CLCs from HeLa clones expressing WT or mutant CLCb (Fig. 5c), antibody to inactive β1-integrin was internalized (Fig. 5d). A recycling defect was observed for cells expressing the mutant CLCb but rescued in cells expressing WT CLCb (Fig. 5e). Thus, recycling of inactive β1-integrin involves CLC–Hip interactions. Internalization of inactive β1-integrin was partially impaired in the cells expressing the mutant CLCb (Fig. 5d), but internalized antibody was not recycled in these cells upon depletion of endogenous CLC.

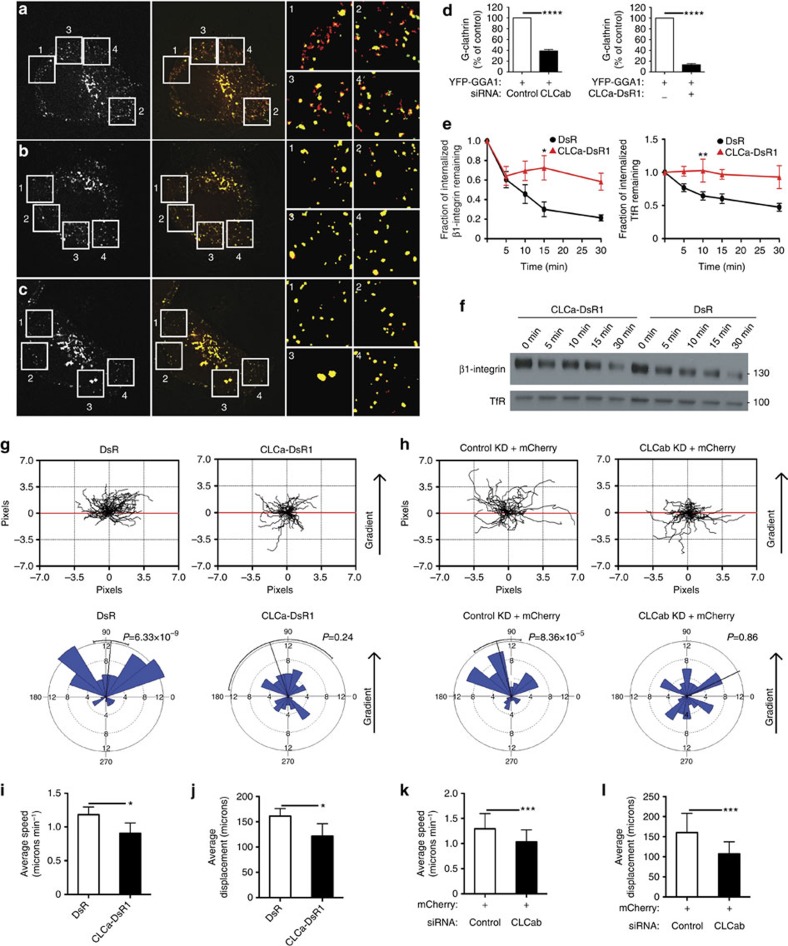

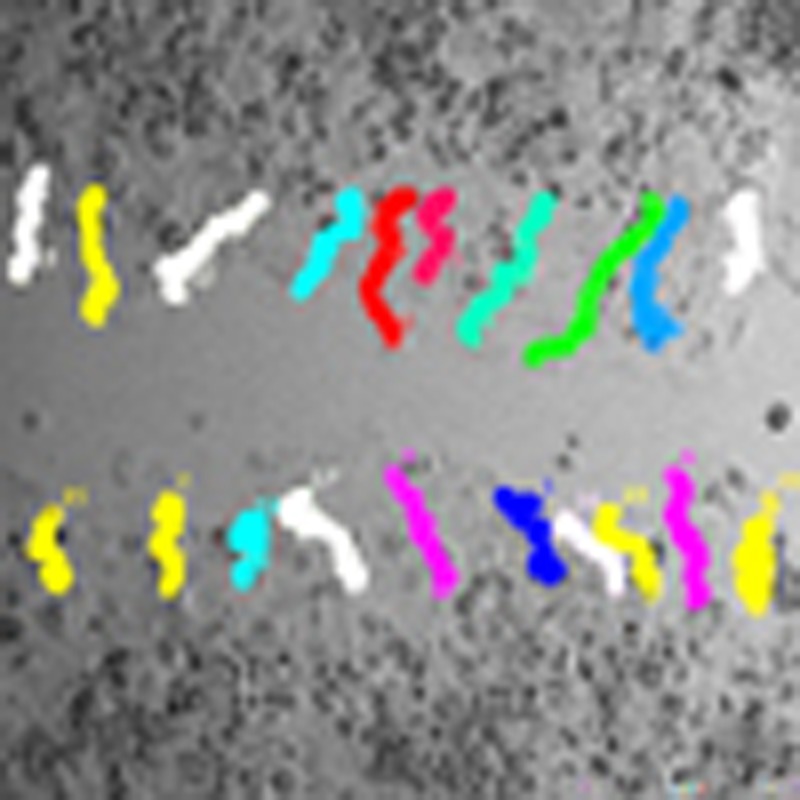

Integrins transit through rapid and slow recycling pathways during cell migration. A role for clathrin in recycling to the plasma membrane from endosomes has been much debated, but it is clear that one of the pathways for rapid recycling of transferrin receptor involves G-clathrin26. G-clathrin has been visualized using fluorescent protein fusions with CLCs or with GGA1 adaptors, with which it is associated in the cell periphery26,28, and its recruitment to endosome-derived structures is ADP-ribosylation factor 6 (ARF6)-dependent34. Many ARF6-dependent pathways involve actin, thus suggesting a role for CLCs in G-clathrin. To visualize G-clathrin under CLC depletion conditions, HeLa-M cells (a flat subclone of HeLa cells) were simultaneously transfected with siRNA and GGA1 coupled to yellow fluorescent protein (YFP)26,34. Live transfected cells were imaged using continuous 30 ms exposures (Supplementary Movie 1) and it was obvious that the peripheral, highly mobile GGA1-containing structures were significantly reduced in cells treated with siRNA targeting CLC. These structures were also absent from cells co-transfected with CLCa coupled to DsRed1 (CLCa–DsRed1). GGA1 in G-clathrin structures was quantified by comparing segmented maximum projection images (comprising both highly mobile G-clathrin and stable clathrin structures) to summed projection images (emphasizes relatively stationary structures, not G-clathrin). Upon CLC depletion, there was an ~\n60% reduction in G-clathrin structures compared with cells treated with control siRNA (Fig. 6a,b,d), and an ~\n85% reduction in G-clathrin in cells expressing CLCa–DsRed1 (Fig. 6a,c,d). Though in other respects (that is, labelling of plasma membrane coated pits and trans-Golgi network clathrin), CLCa–DsRed1 appears to be similar to GFP–CLC and has been used for live cell imaging of clathrin35,36,37, here it acts as a dominant negative CLC mutant that specifically affects G-clathrin. Consistent with its effect on G-clathrin, CLCa–DsRed1 expression attenuated recycling of the known G-clathrin cargo transferrin receptor and it reduced β1-integrin recycling, as assessed by the biotinylation-based recycling assay (Fig. 6e,f and Supplementary Fig. 5a). Linking this G-clathrin recycling pathway to migration, expression of CLCa–DsRed1 impaired migration of H1299 cells towards a gradient of EGF, visualized by tracking transiently transfected fluorescent cells in a Dunn chamber assay (Fig. 6g and Supplementary Fig. 5b). The effect of CLCa–DsRed1 expression was similar to the effect of CLC depletion in the same Dunn chamber assay, where transfected cells were visualized by co-transfection of mCherry and siRNA (Fig. 6h and Supplementary Fig. 5c). HeLa cells expressing CLCa–DsRed1 or depletion of CLCs demonstrated a reduction in speed as well as displacement, compared with control cells (Fig. 6i–l). This migration behaviour on matrigel in the Dunn chamber contrasted with the marginal reduction of speed observed in the wound-healing assay upon CLC depletion (Figs 2 and 3). Matrigel contains ligands for several integrins including β1-integrin, therefore migration on this substrate could be more sensitive to an integrin recycling defect. Together these results implicate CLC as an active component of the G-clathrin rapid recycling pathway for β1-integrin as well as transferrin receptor, and demonstrate the importance of this pathway in cell migration.

Figure 6. Expression of CLCa–DsRed1 or CLC depletion causes loss of G-clathrin structures and CLCa–DsRed1 reduces recycling and cell migration.

(a–c) HeLa-M cells transfected with YFP-GGA1, and with either (a) control siRNA, or (b) CLCab siRNA or with (c) CLCa–DsRed1 were imaged using continuous 30 ms exposures (~\n1 s total). A single image from each sequence is shown on the left. Combined maximum projections (red), which reveal both dynamic and stationary GGA1 structures and sum projections (green), which report stationary structures, are shown at the right, with overlap in yellow (54 μm square panels). Dynamic G-clathrin appears red. Boxed areas are magnified (right) and pixel intensities binarized for clarity. (d) Percent of G-clathrin relative to controls in HeLa-M cells transfected with CLCab siRNA or CLCa–DsRed1 (CLCa-DsR1) in a–c. G-clathrin for each condition was calculated as the difference between the maximum projection and sum projection of YFP-GGA1 signals (see Methods for details) (mean±s.e.m.; n=4 for CLCab, knockdown (KD) n=2 for CLCa-DsR1, ****P<0.0001, Student’s unpaired t-test). (e) Recycling of β1-integrin (left) and TfR (right), assessed by biotinylation as in Fig. 4d, in DsRed1 (DsR)- or CLCa–DsR1-transfected HeLa cells (mean±s.e.m.; n=7; *P<0.05, **P<0.01, two-way analysis of variance followed by Bonferroni post hoc test). (f) Representative immunoblots from one recycling experiment in e. Lysate samples are shown in Supplementary Fig. 5a. (g,h) Dunn chamber migration tracks of H1299 cells transfected with (g) DsR or CLCa–DsR1 or (h) mCherry plus control or CLCab siRNA in the presence of an EGF gradient (source at 90°). Tracks in the absence of a gradient are shown in Supplementary Fig. 5b,c. All tracks were set to a common origin (intersection of x [red] and y axes). Circular histograms depict proportion of cells whose final position lies within each of 18 20° sectors (mean and 95% confidence interval indicated by black line; at least 50 cells analysed from four independent experiments for each condition, P-values, Raleigh uniformity test). (i) Average speed and (j) displacement of DsR- and CLCa–DsR1-transfected gradient-exposed cells. (k) Average speed and (l) displacement of control-treated and CLCab-depleted gradient-exposed cells. (i–l: mean±s.e.m.; n=4 *P<0.05, **P<0.01, Student’s paired t-test).

CLCb expression increases in migratory trophoblast cells

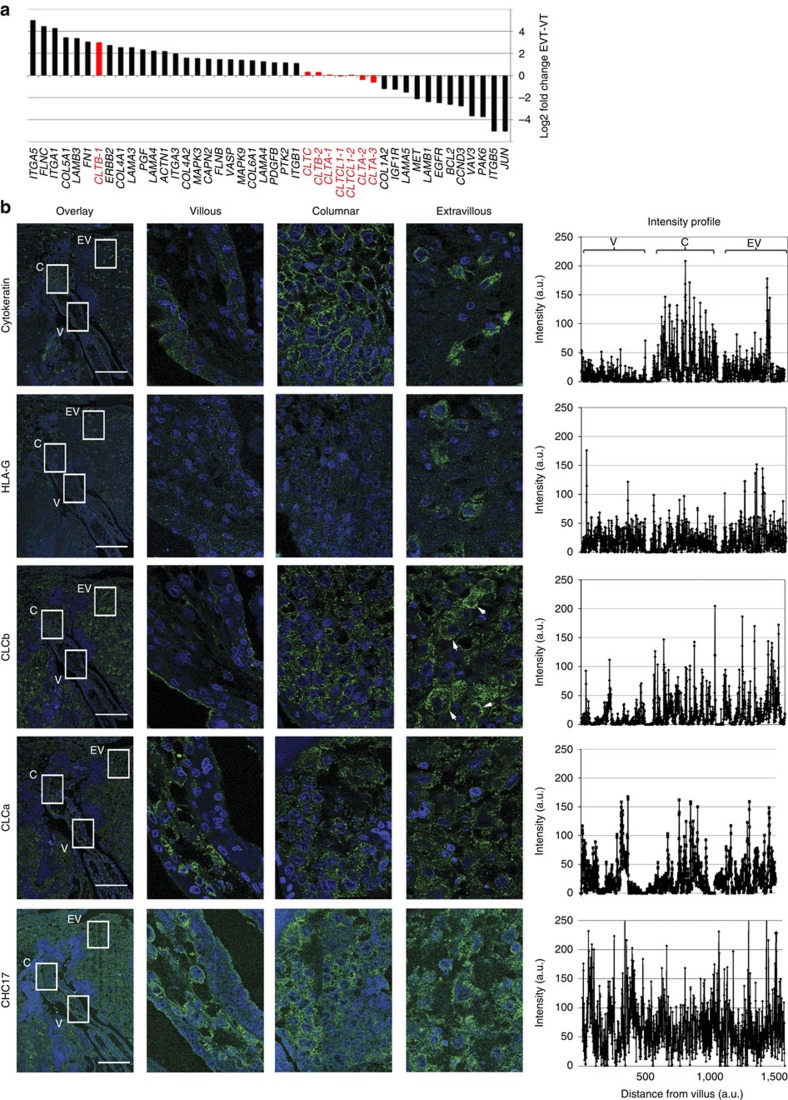

Villi of the placenta are covered by villous trophoblast (VT) cells of fetal origin. Specialized anchoring villi are formed where the placenta contacts the uterine wall from where migratory extravillous trophoblast (EVT) cells invade the uterine lining. This infiltration results in remodelling of maternal arteries, leading to placental vascularization38. In search of a physiological correlate for the role of CLC in migration, we queried available data from a microarray analysis comparing gene expression in VT versus EVT39 cells. As expected, several genes involved in cell adhesion and migration were upregulated in the migratory EVT cells compared with non-migratory VT cells (Fig. 7a). Strikingly, we noted that non-neuronal CLCb was one of the top genes upregulated in invasive EVT cells (Fig. 7a). No such increase in expression was observed for non-neuronal or neuronal CLCa, neuronal CLCb or CHC17 transcripts in these cells, suggesting that CLCb may uniquely contribute to the migratory potential of EVT cells.

Figure 7. CLCb is upregulated in invasive extravillous trophoblast cells.

(a) Microarray analysis of mRNA in human trophoblast cells showing relative gene expression levels in extravillous trophoblast (EVT) cells compared with villous trophoblast (VT) cells. Genes encoding clathrin subunits and their transcript levels are indicated in red. CLTB encodes CLCb, CLTA encodes CLCa, CLTC encodes CHC17 and CLTCL1 encodes CHC22. For three genes encoding clathrin subunits, more than one probe was used to detect splice variants and these are numbered. Probes CLTB-1, CTLA-2, CLTA-3 and CLTCL1-1 detect all variants, CLTB-2 and CLTA-1 detect the neuronal splice variants of CLCs and CLTCL1-2 detects a second splice variant encoded by this gene. (b) Serial sections of normal, non-cancerous human placental tissue were stained for CLCb, CLCa, CHC17 and trophoblast markers, as indicated. Cytokeratin staining depicts cytotrophoblast cell columns (columnar) and invading extravillous trophoblast cells developing from placental villi. Extravillous trophoblast was distinguished from villous trophoblast on the basis of HLA-G expression. Arrowheads depict extravillous trophoblast cells with high CLCb expression. Intensities of the staining are quantified as arbitrary units (a.u.) and illustrated on the right as line profiles across each box shown at the far left. V, villous; C, columnar; EV, extravillous trophoblast. Scale bars, 500 μm.

To establish whether CLCb protein increases in EVT cells as a result of increased gene expression, we analysed the distribution of clathrin and CLCs in placental tissue sections by tracking the level of immunofluorescence across tissue sections from VT to EVT cells. These trophoblast regions were identified by immunolabelling for standard markers of all trophoblast (cytokeratin) and of EVT cells, which express HLA-G on their surface during invasion40 (Fig. 7b). Consistent with known distribution, cytokeratin expression was observed in cytotrophoblast cell columns and interstitial trophoblast cells present in maternal tissue. The EVT cells showed expression of HLA-G as expected (Fig. 7b). CLCb was barely detectable in the VT cells (Fig. 7b), but labelling increased in EVT cells (indicated by arrowheads in Fig. 7b) in the vicinity of maternal vessels. In contrast, CLCa and CHC17 expression were uniform across all trophoblast regions (Fig. 7b). These observations were reproduced in other placental sections from an unrelated individual, and agree with the array data. Thus tissue expression analysis suggests a physiological role for CLCb in trophoblast invasion that is consistent with a role for CLC in cell migration.

Discussion

This study establishes a role for CLC subunits and their Hip binding in the recycling of inactive β1-integrin and in cell migration. Moreover, we show that the rapid endosomal recycling pathway mediated by G-clathrin structures depends on CLC function and that a specific inhibitor of G-clathrin attenuates cell migration and β1-integrin recycling, as well as recycling of the known G-clathrin cargo, transferrin receptor. Identification of G-clathrin as a mediator of rapid endosomal recycling during migration and demonstrating its CLC dependence, implicates the CLC-binding Hip proteins as additional actin organizers needed for this pathway, shown previously to also require the actin-organizing proteins Wiskott–Aldrich syndrome protein family homologue (WASH) and actin-related protein (Arp) 2/3 complex41. In support of a key role for CLC-dependent G-clathrin in cell migration, we observed upregulation of CLCb in migrating trophoblast, providing an in vivo correlate for our findings.

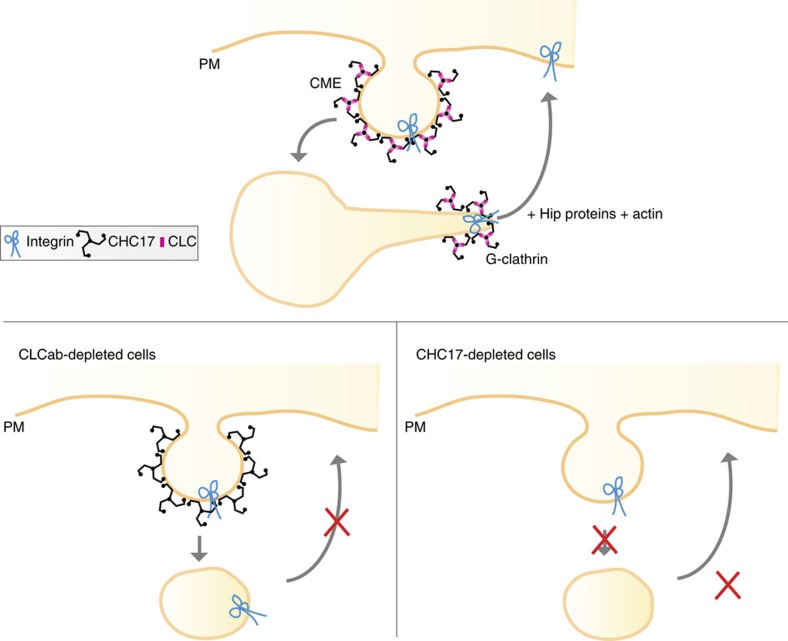

The role of clathrin in migration mediated by CLC defined here is distinct from that previously established by depletion of the CHC17 CHC, which revealed a role for clathrin in endocytosis of inactive β1-integrin during migration18. These distinguishable clathrin-mediated trafficking pathways for inactive β1-integrin (Fig. 8) both influence focal adhesions. CHC17 depletion increased focal adhesions, as expected from reduced integrin uptake, whereas CLC depletion had the opposite effect (Fig. 1), explained by reduced recycling of β1-integrin with persistent internalization. Supporting the concept that clathrin functions in balanced membrane traffic pathways during cell migration, overexpression of a CLCb mutant that reduced actin-associated clathrin plaques at the cell-substrate interface was shown to enhance migration23. That particular QQN-CLCb mutant studied, is defective for both Hip binding and for regulation of clathrin assembly13,14,42, so could not distinguish between CLC and CHC17 roles in migration. Here, using different mutants, we show that both migration and β1-integrin recycling depend on the minimal CLC–Hip binding residues, without altering the CLC residues involved in clathrin assembly. The CLC-dependent G-clathrin recycling pathway could potentially influence levels of growth factor receptors and affect directional migration, also explaining variable migration phenotypes seen with different cells and interference protocols. We further note that CHC17 has been implicated in lamellipodium formation, and could affect cell migration via recruitment of the Scar–Wave complex to the leading edge of the cell29. Thus clathrin plays multiple roles in cell motility, expanded by the function of CLC and G-clathrin in β1-integrin recycling established here.

Figure 8. Model for the roles of clathrin in inactive β1-integrin membrane traffic during cell migration.

Clathrin is involved in both endocytosis from the plasma membrane (PM) and recycling of inactive β1-integrin from endosomes. CLC is required for the recycling of β1-integrin back to the cell surface via G-clathrin structures, but not needed for clathrin-mediated endocytosis (CME). Loss of the total clathrin by CHC17 depletion inhibits all pathways, but manifests itself as an endocytosis defect. We note that non-clathrin-mediated endocytic routes can also contribute to integrin uptake21.

Defining the roles of CLC in cellular clathrin function has been challenging, although in vitro biochemical studies have demonstrated a role for CLC in regulating both clathrin assembly and Hip interactions with actin3,16. The requirement for CLCs in CME is limited to some G-protein-coupled receptors, but dispensable for many common CME cargo5,6,7. On the other hand, uptake of cargo from membranes under tension and of large pathogen particles depend on CLC interactions with Hip proteins8,9,10,43. In these latter situations, clathrin serves an actin organizer, a role that it also plays at certain bacterial–host interfaces8 and during adherens junction formation44. Hip1R has been implicated in actin-based movements of Rickettsia and clathrin is required for actin polymerization during vaccinia infection45,46, suggesting that CLC may be similarly involved. Here we add to the repertoire of actin-based functions mediated by CLC. Upon CLC depletion, we observe disorganized, branched actin filaments at the cell periphery and reversing the depletion phenotype requires CLC–Hip interaction. We further show that CLC is needed for G-clathrin, as well as migration and recycling, which also depend on CLC–Hip binding. G-clathrin has a characteristic ‘gyrating’ behaviour in the cell periphery and represents endosome-associated clathrin-coated tubules that mediate rapid recycling26. We propose that CLC is needed for G-clathrin to function in recycling and migration because, through Hip binding, CLC could connect tubule-associated clathrin coats with actin for directional extension from endosomes. Clathrin-coated carriers bound to ARF1 and adaptor protein 1 (AP1) in the trans-Golgi network form actin-based tubules47, and G-clathrin is also nucleated by ARF1 and ARF6 (ref. 34). CLC depletion was reported to change actin morphology in a perinuclear compartment labelled for the AP1 adaptor6, consistent with our finding a function for CLC on endosome-associated clathrin and possibly a further role for CLC on trans-Golgi network tubule clathrin. It is notable that CLCa–DsRed1 acts as a dominant negative mutant in the G-clathrin recycling pathway, though it has been used as a marker for live cell imaging of clathrin and functions normally at the plasma membrane. This is likely a consequence of a unique intolerance of G-clathrin to oligomerization of CLCs, driven by the obligate tetrameric quaternary structure of DsRed1 (ref. 48). In contrast, either N- or C-terminal-tagged fusions of CLCs with predominantly monomeric GFP, YFP or mCherry proteins all give robust evidence of G-clathrin.

The observation that CLCb is markedly upregulated in invasive trophoblast further strengthens our assignment of an important role for CLC in migration. In our cellular studies, there was no distinction between CLCa and CLCb function in migration or influence on actin organization or recycling, as each CLC isoform seems to substitute for the other in restoring the knockdown phenotypes observed here. Tissue analysis has indicated that the CLCa:CLCb ratio is characteristic of different tissues and that CLCa is usually the more abundant49,50. Indeed, the tissue section staining we performed shows ubiquitous expression of CLCa in all placental regions. Currently little is known about clathrin gene regulation, but it may be that CLCb expression is more subject to transcriptional regulation, allowing its increase during differentiation. Alternatively or additionally, CLCa and CLCb share only 60% sequence identity outside of their identical Hip-binding regions, so it is possible that there are functional differences in flanking sequences that affect Hip–actin interactions required for trophoblast migration, again needing further biochemical evaluation.

Pre-eclampsia occurs when trophoblast invasion of the uterine wall is defective40, so CLC expression might be a therapeutic target for women with pregnancy disorders. Another physiological correlate, not addressed directly here, is the observation that Hip1 expression is upregulated in metastatic breast and prostate cancers as well as other malignancies51,52,53. It is conceivable that increased Hip expression enhances migratory behaviour. Migration of H1299 cells was more sensitive to CLC and Hip knockdown than migration of the slower-moving HeLa cells, which express less Hip1 protein. Thus, defining the role of CLC in cell migration establishes a potential mechanism for metastasis of cancers with increased Hip expression that might be considered as a molecular target for anti-metastatic strategies.

Methods

siRNAs and plasmids

siRNA duplexes were synthesized by Qiagen. Targeting sequences were published as follows, CHC17, CLCa and CLCb5, CHC22 (ref. 31), or designed by Qiagen for Hip proteins (5′-CAGGAACTTGCCACAAGCCAA-3′, Hip1 and 5′-CTCCGACATGCTGTACTTCAA-3, Hip1R). The CLC siRNA-resistant construct (WT, with a silent mutation at serine 88 from AGT to TCA) or CLC–Hip-binding resistant mutant (I38A and D25A) of bovine brain CLCa was generated from a 5′-HA-tagged pcDNA3-based construct13, with QuikChange site-directed mutagenesis kit (Stratagene). Mutant human CLCa (I43A) and CLCb (I35A) encoding constructs that are siRNA resistant were similarly produced without the HA tag.

Tissue culture and transfections

HeLa cells (lab stock) and the H1299 lung cancer cell line (gift of J.M. Bishop, UCSF) were cultured in DMEM and RPMI-1640, respectively, supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) (Hyclone) and antibiotics. Cells were trypsinized and transfected at ~\n30% confluency with siRNA using the HiPerfect reagent (Qiagen), following the manufacturer’s protocols. For transient rescue experiments, cells were transfected with plasmid DNA one day after siRNA transfection, using Lipofectamine 2000 (Life Technologies) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Cells were analysed 72 h post siRNA treatments.

HeLa and H1299 clones expressing the empty vector, siRNA-resistant human WT CLCa or CLCb, or human Hip-binding resistant mutant CLCa (I43A) or CLCb (I35A) were established by transfection of plasmids into HeLa and H1299 cells using Lipofectamine 2000 (Life Technologies) as above. G418 (Life Technologies) was added to the cell culture medium at 500 μg ml−1 48 h post transfection to select clones. Individual G418 resistant colonies were selected and expanded into cell lines 3 weeks later, followed by confirmation of plasmid expression by immunoblotting.

Antibodies and other reagents

The following monoclonal antibodies were used for immunofluorescence: anti-CHC17 (2 μg ml−1; X22 (ref. 54)), cortactin (1:500; Millipore, number 05–180), paxillin (1:500; Millipore, number 05–417), anti-HA (1:100; Covance, number MMS-101P). Rat anti-CD29 mAb13 against inactive β1-integrin (5 μg ml−1; BD biosciences, number BDB552828), rabbit polyclonal antisera against the conserved region of CLCs55, and Hip1R (1:100; Millipore, number AB9882) were also used. Secondary labelling was done with Alexafluor-488 (1:500; Life Technologies, number A-11001) or 555-conjugated secondary antibodies (1:500; Life Technologies, number A-21422). Alexafluor 647-phalloidin (1:100; Life Technologies, number A-22287) was used to stain F-actin. The following antibodies were used for immunoblotting: anti-CHC17 (1:1,000; TD.1 (ref. 56)), Hip1R (1:500; Millipore, number AB9882), β1-integrin (1:1,000; BD Biosciences, number 610467), TfR (1:1,000; BD Biosciences, number 612124), HA (1:1,000; Covance, number MMS-101P), Hip1 (1:500; Sigma, number HPA013606), anti-β-actin (1:2,000; Sigma, number A5441) and α-tubulin (1:5,000; Sigma, number T6199).

Immunoblotting

Cells were lysed in a buffer containing 50 mM Tris (pH 7.2), 1% Triton X-100, 150 mM NaCl, and 20 mM EDTA55. Protease inhibitors (Roche) were added to the buffer before lysis. Protein content was determined using Bradford reagent (Bio-Rad). Equal amounts of cell lysates were resolved on pre-cast SDS–PAGE gels (Invitrogen) and transferred onto nitrocellulose membranes (Bio-Rad), followed labelling with primary and secondary antibodies.

Migration assays

HeLa or H1299 cells treated with 20 nM siRNA for 48 h were plated at 2 × 105 cells ml−1 in culture inserts (Ibidi GmbH) affixed to wells in glass-bottom (MatTek) or tissue culture plastic (BD Falcon) 24-well plates and allowed to adhere for 24 h. Before imaging, culture inserts were removed to create the wound, and the cells were washed in culture medium with 1% FBS. Migration across the wound was imaged once every 10 min for 24 (HeLa) or 10–15 h (H1299) using a × 10 objective on a Leica TCS SP5 microscope. Cells were maintained at 37 °C and 5% CO2 for the duration of the experiment. Cells were tracked using the MTrackJ plugin of ImageJ. Twenty cells were tracked per condition for each experiment. Wound-healing assays for parent HeLa and H1299 cell lines were performed on glass, whereas migration of CLC transfectants was assessed on plastic, which better supported migration.

Chemotaxis assays were performed using the Dunn chamber (Hawksley DCC100). Two thousand four hundred H1299 cells transfected with either DsRed1 or CLCa–DsRed1, or mCherry and either control or CLCab siRNA, were plated on 2% matrigel-coated coverslips and allowed to adhere for 6 h in complete medium. Cells were then starved overnight in a medium containing 0.01% serum. The coverslip was placed onto the Dunn chamber in which both inner and outer wells were filled with control medium (medium containing 0.01% serum) and three sides were sealed with wax. Media from the outer well was drained using filter paper and control media containing 1 ng ml−1 EGF was inserted into the outer well and the fourth side was then sealed with wax. To assess migration in the absence of a gradient, all four sides of the coverslip were sealed with wax once the coverslip was placed onto the chamber containing control medium. The Dunn chamber was then placed on a heated stage at 37 °C. Time-lapse images were taken every 5 min for 3 h using a × 10 objective on a Leica TCS SP5 microscope. Migration of non-dividing DsRed1-, CLCa–DsRed1- or mCherry-expressing cells were tracked using the MtrackJ plugin of ImageJ.

Immunofluorescence

Cells grown on coverslips were fixed using 4% PFA (Ted Pella, Inc.) for 10 min. When viewing HA-tagged CLCa with other proteins stained by a monoclonal antibody, Alexafluor 594-conjugated monoclonal antibody to HA (1:500; Covance, number A594-101L) was applied after incubation with secondary antibody. Images were collected with an API DeltaVision DV3 restoration or a Leica TCS SP5 confocal microscope. To determine the percent of cell periphery occupied by focal adhesions, the sum of edges stained for paxillin along the cell perimeter was divided by the cell perimeter, with both measured using ImageJ.

Paraffin-embedded serial placental sections from a de-identified normal human sample were deparaffinized in xylene and rehydrated in reducing concentrations of ethanol (100–70%). Following washes with water and PBS, antigen epitopes were unmasked by boiling slides in 10 mM sodium citrate for 10 min. Cooled slides were washed in PBS, and sections were permeabilized in blocking buffer (PBS, 5% BSA and 2% goat serum) with 0.1% Triton X-100 for 30 min. Sections were incubated in the following primary antibodies diluted in the blocking buffer for 1 h at room temperature: 5 μg ml−1 of LCB.1 (for CLCb)57, of X16 (for CLCa)54 and of X22 (for CHC17)54, 10 μg ml−1 of anti-HLA-G (MEM-G/1, SantaCruz, number sc-51674), or 0.2 μg ml−1 of anti-cytokeratin (Clone MNF116, Dako Cytochromation, number M082101-2). Following washes in PBS with 0.1% Tween-20, secondary antibodies (10 μg ml−1) and TO-PRO (Life Technologies, number T3605) were incubated with 10% human AB serum for 30 min. After 30 min room temperature incubation, the slides were washed in PBS with 0.1% Tween-20 and mounted. Images in Fig. 7 were cropped to depict the same area using Adobe Photoshop CS3. The intensity of all channels was adjusted equally across all images. The difference in protein expression between the villous trophoblast (V), cytotrophoblast column (C) and the extravillous trophoblast (EV) cells within an image was quantified as follows. A line was drawn within the boxed regions in the mosaic image and the plot profile function in ImageJ was used to calculate pixel intensities along the line. Approval to use these tissues was obtained by the UCSF Committee on Human Research and the Cambridge Local Research Ethics Committee.

MTT assay

To measure cell proliferation, MTT assays (Molecular Probes) were performed according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Briefly, 10,000 cells were plated in triplicate in each well of a 96-well plate. After 24 or 48 h, fresh media was added to the cells followed by 12 mM MTT reagent for 4 h at 37 °C. After the incubation period, dimethylsulphoxide was added to the cells to dissolve the formazan and absorbance was read at 540 nM.

Expression profiling by microarray

RNA expression levels in primary trophoblast cells were determined as previously described39. Briefly, biotinylated cRNA was synthesized from total RNA isolated from primary trophoblast cells using the Illumina RNA amplifcation kit (Ambion). Labelled cRNA was hybridized to Illumina Human HT-12 V3 BeadArrays according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Data were processed by converting signal intensities to log2 expression units. Differential gene expression between two groups of samples was determined using the output of a moderated t-test. P-values were converted to corrected q-values using the previously published FDR method58 and probe-sets with q<0.01 (FDR 1%) were regarded as having significant differential expression between groups.

Antibody-based internalization and recycling assays

Cells plated on glass coverslips were treated with siRNA for 72 h, then serum starved for 1 h, followed by labelling with 5 μg ml−1 antibody to inactive (mAb13) β1-integrin on ice for 15 min. Cells were washed to remove excess antibody and incubated in pre-warmed culture medium supplemented with 10% FBS at 37 °C for 30 min to start integrin internalization. To determine surface levels of integrins, cells were placed on ice, washed with ice-cold PBS, fixed in ice-cold 4% PFA, then blocked with 0.2% fetal goat serum and incubated with Alexafluor-555 secondary antibody for 1 h. To determine internal levels, surface integrins were stripped with ice-cold PBS (pH 2.5) before fixation, followed by permeabilization with 0.2% Triton X-100. The cells were blocked and incubated with Alexafluor-555 secondary antibody as above. To measure recycling, labelled integrins were allowed to internalize at 37 °C as above, followed by stripping of surface integrins with ice-cold PBS (pH 2.5). Cells were washed with ice-cold PBS, then incubated in pre-warmed medium (10% FBS) for 30 min at 37 °C to chase internal integrins to the surface. Surface and internal integrins were determined as above. Images sections were acquired every 0.5 μm in a 2.5-μm slice through the middle of the cell and merged into maximum projections. The mean fluorescent intensity for each image was obtained by measuring total fluorescence, followed by mean background subtraction using ImageJ. This value was then divided by the total number of cells in each image.

Surface biotinylation and biotinylation-based recycling assays

siRNA-treated cells were washed twice in ice-cold PBS (pH 8) and surface proteins were biotinylated with 0.5 mg ml−1 Sulfo-NHS-SS Biotin (Thermo Fisher Scientific) in ice-cold PBS (pH 8) for 30 min at 4 °C. Excess biotin was quenched by washing cells twice with ice-cold 5 mM Tris (pH 7.4), followed by two washes with ice-cold PBS (pH 8) and one wash with PBS (pH 7.4). Cells were lysed in PBS with 1% NP-40 containing protease inhibitors (Roche). Protein concentrations in the samples were determined using Bradford reagent and equal amounts of total protein were loaded onto streptavidin beads (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and incubated at 4 °C for 1 h. After washing the beads, proteins were eluted by boiling the beads in SDS sample buffer, followed by immunoblotting. Blots were quantified using ImageJ, and the level of surface receptors were normalized to the α-tubulin signal from each sample.

For biotinylation-based recycling assays, serum starved siRNA-treated cells were labelled with biotin and the excess washed as above. The cells were then placed at 37 °C in media containing 10% FBS for 30 min to allow internalization of surface proteins. Surface biotin was then reduced with two 10 min washes with 50 mM MesNa (pH 8.6) in TBS, followed by one 10 min wash with 20 mM iodoacetamide in TBS, all at 4 °C. Cells were then rinsed with ice-cold PBS and placed at 37 °C in media containing 10% FBS for indicated time points to chase internalized proteins to the cell surface. Surface biotin was then reduced again as described, and the cells were lysed, equal amounts of protein loaded onto streptavidin beads, eluted and blotted as mentioned above. The fraction of internalized receptor remaining for each protein was determined from the signal intensity of internalized protein at each time point relative to control cells that had not been placed at 37 °C after the first surface reduction.

Quantification of G-clathrin by GGA1 movement

Hela-M cells were transfected with either control or CLC-targeting siRNA, and then co-transfected with plasmid encoding YFP-GGA1 48 h later, or they were transfected with plasmid encoding either YFP-GGA1 alone or YFP-GGA1 and CLCa–DsRed1. The cells were then imaged 24 h post DNA transfection by spinning disk confocal microscopy using streaming 30 ms exposures to collect 30 frame image stacks as previously described34. For quantification of G-GGA1, we used a modified assay on the basis of movement area26. Briefly, stacks were background corrected using a rolling ball filter (r=5) in ImageJ. Using MetaMorph (Molecular Devices, Inc.), a maximum projection (comprising both highly mobile G-GGA1 and unwavering (stable ) structures) and sum projection (emphasizing unwavering (stable) structures) of each stack were prepared. Each stack was thresholded (using mean+1s.d.) and binarized. Regions 100 pixels on edge were randomly selected near the periphery of the cell and maximum projection pixels that did not overlap with the corresponding sum projection were retained, yielding an estimate of ‘G-GGA1 area’. Approximately 80 regions from 20 cells for each condition in three independent experiments were analysed, and mean G-GGA1 area in control cells was set to 100%. Data were analysed by a two-tailed unpaired t-test.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis of directionality for Dunn chamber assays was carried out using Oriana (Kovach Computing Services, Anglesey, Wales). All other analyses were carried out using GraphPad Prism software (GraphPad Software, Inc). Parametric data were analysed using two-tailed Student t-tests, one-way or two-way analysis of variance, followed by Newman–Keuls or Bonferroni post hoc tests for multiple comparisons as appropriate (95% confidence interval).

Author contributions

S.R.M., L.V., C-Y.C., A.M., J.H.K. and F.M.B. designed the experiments. S.R.M., L.V., C-Y.C., Y.L., J.A.T., T.M.E., A.S., A.B.F., N.M.L.W. and C.E. performed the experiments. A.M. contributed sample material and T.A.F. contributed analytical tools. S.R.M. and F.M.B. wrote the manuscript with input from L.V., C-Y.C., Y.L., A.M. and J.H.K.

Additional information

How to cite this article: Majeed, S. R. et al. Clathrin light chains are required for the gyrating-clathrin recycling pathway and thereby promote cell migration. Nat. Commun. 5:3891 doi: 10.1038/ncomms4891 (2014).

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Figures 1-5

CLC depletion decreases G-clathrin detected by YFP-GGA1.HeLa-M cells were transfected with YFP-GGA1 and with either control (Control) or siRNA targeting CLCab (KD CLCa+CLCb), or with CLCa-DsRed1 (DsRed-CLCa). YFP-GGA1 in expressing cells was imaged 24 hours post-transfection using continuous 30 ms exposures (~1 s total). Play back is in realtime. Blue squares are representative of boxed areas in the cell periphery that were quantified and are magnified 5 times below, as described in Methods. Field size: 7.35μm x 7.35μm

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIH grant GM038093 to F.M.B. and GM049217 to J.H.K., and NIH training grants T32 GM07175 and NCI F31 CA171594 to S.R.M.

References

- Brodsky F. M. Diversity of clathrin function: new tricks for an old protein. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 28, 309–336 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ybe J. A. et al. Nuclear localization of clathrin involves a labile helix outside the trimerization domain. FEBS Lett. 587, 142–149 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilbur J. et al. Conformation switching of clathrin light chain regulates clathrin lattice assembly. Dev. Cell 18, 841–848 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinrichsen L., Harborth J., Andrees L., Weber K. & Ungewickell E. J. Effect of clathrin heavy chain- and alpha -adaptin specific small interfering RNAs on endocytic accessory proteins and receptor trafficking in HeLa cells. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 45160–45170 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang F., Khvorova A., Marshall W. & Sorkin A. Analysis of clathrin-mediated endocytosis of epidermal growth factor receptor by RNA interference. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 16657–16661 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poupon V. et al. Clathrin light chains function in mannose phosphate receptor trafficking via regulation of actin assembly. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 105, 168–173 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira F. et al. Endocytosis of G protein-coupled receptors is regulated by clathrin light chain phosphorylation. Curr. Biol. 22, 1361–1370 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonazzi M. et al. Clathrin phosphorylation is required for actin recruitment at sites of bacterial adhesion and internalization. J. Cell Biol. 195, 525–536 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cureton D. K., Massol R. H., Whelan S. P. J. & Kirchhausen T. The length of vesicular stomatitis virus particles dictates a need for actin assembly during clathrin-dependent endocytosis. PLoS Pathog. 6, e1001127 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boulant S., Kural C., Zeeh J. C., Ubelmann F. & Kirchhausen T. Actin dynamics counteract membrane tension during clathrin-mediated endocytosis. Nat. Cell Biol. 13, 1124–1131 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boettner D. R., Friesen H., Andrews B. & Lemmon S. K. Clathrin light chain directs endocytosis by influencing the binding of the yeast Hip1R homologue, Sla2, to F-actin. Mol. Biol. Cell 22, 3699–3714 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aghamohammadzadeh S. & Ayscough K. R. Differential requirements for actin during yeast and mammalian endocytosis. Nat. Cell Biol. 11, 1039–1042 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen C. Y. & Brodsky F. M. Huntingtin-interacting protein 1 (Hip1) and Hip1-related protein (Hip1R) bind the conserved sequence of clathrin light chains and thereby influence clathrin assembly in vitro and actin distribution in vivo. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 6109–6117 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Legendre-Guillemin V. et al. Huntingtin interacting protein 1 (HIP1) regulates clathrin assembly through direct binding to the regulatory region of the clathrin light chain. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 6101–6108 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gottfried I., Ehrlich M. & Ashery U. The Sla2p/HIP1/HIP1R family: similar structure, similar function in endocytosis? Biochem. Soc. Trans. 38, 187–191 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilbur J. D. et al. Actin binding by Hip1 (huntingtin-interacting protein 1) and Hip1R (Hip1-related protein) is regulated by clathrin light chain. J. Biol. Chem. 283, 32870–32879 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones M. C., Caswell P. T. & Norman J. C. Endocytic recycling pathways: emerging regulators of cell migration. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 18, 549–557 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ezratty E. J., Bertaux C., Marcantonio E. E. & Gundersen G. G. Clathrin mediates integrin endocytosis for focal adhesion disassembly in migrating cells. J. Cell Biol. 187, 733–747 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teckchandani A. et al. Quantitative proteomics identifies a Dab2/integrin module regulating cell migration. J. Cell Biol. 186, 99–111 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bridgewater R. E., Norman J. C. & Caswell P. T. Integrin trafficking at a glance. J. Cell Sci. 125, 3695–3701 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arjonen A., Alanko J., Veltel S. & Ivaska J. Distinct recycling of active and inactive beta1 integrins. Traffic 13, 610–625 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shieh J. C., Schaar B. T., Srinivasan K., Brodsky F. M. & McConnell S. K. Endocytosis regulates cell soma translocation and the distribution of adhesion proteins in migrating neurons. PLoS ONE 6, e17802 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saffarian S., Cocucci E. & Kirchhausen T. Distinct dynamics of endocytic clathrin-coated pits and coated plaques. PLoS Biol. 7, e1000191 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishimura T. & Kaibuchi K. Numb controls integrin endocytosis for directional cell migration with aPKC and PAR-3. Dev. Cell 13, 15–28 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zech T. et al. The Arp2/3 activator WASH regulates alpha5beta1-integrin-mediated invasive migration. J. Cell Sci. 124, 3753–3759 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao Y. & Keen J. H. Gyrating clathrin: highly dynamic clathrin structures involved in rapid receptor recycling. Traffic. 9, 2253–2264 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsu V. W., Bai M. & Li J. Getting active: protein sorting in endocytic recycling. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 13, 323–328 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parachoniak C. A., Luo Y., Abella J. V., Keen J. H. & Park M. GGA3 functions as a switch to promote Met receptor recycling, essential for sustained ERK and cell migration. Dev. Cell 20, 751–763 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gautier J. J. et al. Clathrin is required for Scar/Wave-mediated lamellipodium formation. J. Cell Sci. 124, 3414–3427 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foraker A. B. et al. Clathrin promotes centrosome integrity in early mitosis through stabilization of centrosomal ch-TOG. J. Cell Biol. 198, 591–605 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vassilopoulos S. et al. A role for the CHC22 clathrin heavy-chain isoform in human glucose metabolism. Science 324, 1192–1196 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esk C., Chen C. Y., Johannes L. & Brodsky F. M. The clathrin heavy chain isoform CHC22 functions in a novel endosomal sorting step. J. Cell Biol. 188, 131–144 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hynes R. O. Integrins: bidirectional, allosteric signaling machines. Cell 110, 673–687 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo Y., Zhan Y. & Keen J. H. Arf6 regulation of gyrating-clathrin. Traffic 14, 97–106 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engqvist-Goldstein A. E. et al. The actin-binding protein Hip1R associates with clathrin during early stages of endocytosis and promotes clathrin assembly in vitro. J. Cell Biol. 154, 1209–1223 (2001). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rappoport J. Z. & Simon S. M. Real-time analysis of clathrin-mediated endocytosis during cell migration. J. Cell Sci. 116, 847–855 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rappoport J. Z., Benmerah A. & Simon S. M. Analysis of the AP-2 adaptor complex and cargo during clathrin-mediated endocytosis. Traffic 6, 539–547 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King A. & Loke Y. W. Placental vascular remodelling. Lancet 350, 220–221 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Apps R. et al. Genome-wide expression profile of first trimester villous and extravillous human trophoblast cells. Placenta 32, 33–43 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moffett-King A. Natural killer cells and pregnancy. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2, 656–663 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zech T., Calaminus S. D. & Machesky L. M. Actin on trafficking: could actin guide directed receptor transport? Cell Adh. Migr 6, 476–481 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ybe J. A. et al. Clathrin self-assembly is regulated by three light chain residues controlling the formation of critical salt bridges. EMBO J. 17, 1297–1303 (1998). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boettner D. R., Chi R. J. & Lemmon S. K. Lessons from yeast for clathrin-mediated endocytosis. Nat. Cell Biol. 14, 2–10 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonazzi M. et al. A common clathrin-mediated machinery co-ordinates cell-cell adhesion and bacterial internalization. Traffic 13, 1653–1666 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serio A. W., Jeng R. L., Haglund C. M., Reed S. C. & Welch M. D. Defining a core set of actin cytoskeletal proteins critical for actin-based motility of Rickettsia. Cell Host Microbe 7, 388–398 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Humphries A. C. et al. Clathrin potentiates vaccinia-induced actin polymerization to facilitate viral spread. Cell Host Microbe 12, 346–359 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anitei M. et al. Protein complexes containing CYFIP/Sra/PIR121 coordinate Arf1 and Rac1 signalling during clathrin-AP-1-coated carrier biogenesis at the TGN. Nat. Cell Biol. 12, 330–340 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baird G. S., Zacharias D. A. & Tsien R. Y. Biochemistry, mutagenesis, and oligomerization of DsRed, a red fluorescent protein from coral. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. USA 97, 11984–11989 (2000). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brodsky F. M. & Parham P. Polymorphism in clathrin light chains from different tissues. J. Mol. Biol. 167, 197–204 (1983). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Acton S. L. & Brodsky F. M. Predominance of clathrin light chain LCb correlates with the presence of a regulated secretory pathway. J. Cell Biol. 111, 1419–1426 (1990). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rao D. S. et al. Huntingtin-interacting protein 1 is overexpressed in prostate and colon cancer and is critical for cellular survival. J. Clin. Invest. 110, 351–360 (2002). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradley S. V. et al. Aberrant Huntingtin interacting protein 1 in lymphoid malignancies. Cancer Res. 67, 8923–8931 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rao D. S. et al. Altered receptor trafficking in Huntingtin Interacting Protein 1-transformed cells. Cancer Cell 3, 471–482 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brodsky F. M. Clathrin structure characterized with monoclonal antibodies. I. Analysis of multiple antigenic sites. J. Cell Biol. 101, 2047–2054 (1985). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Acton S. L., Wong D. H., Parham P., Brodsky F. M. & Jackson A. P. Alteration of clathrin light chain expression by transfection and gene disruption. Mol. Biol. Cell 4, 647–660 (1993). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Näthke I. et al. Folding and trimerization of clathrin subunits at the triskelion hub. Cell 68, 899–910 (1992). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brodsky F. M. et al. Localization of clathrin light-chain sequences mediating heavy-chain binding and coated vesicle diversity. Nature 326, 203–205 (1987). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smyth G. K. Linear models and empirical bayes methods for assessing differential expression in microarray experiments. Stat. Appl. Genet. Mol. Biol. 3, Article3 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Figures 1-5

CLC depletion decreases G-clathrin detected by YFP-GGA1.HeLa-M cells were transfected with YFP-GGA1 and with either control (Control) or siRNA targeting CLCab (KD CLCa+CLCb), or with CLCa-DsRed1 (DsRed-CLCa). YFP-GGA1 in expressing cells was imaged 24 hours post-transfection using continuous 30 ms exposures (~1 s total). Play back is in realtime. Blue squares are representative of boxed areas in the cell periphery that were quantified and are magnified 5 times below, as described in Methods. Field size: 7.35μm x 7.35μm