Abstract

Impairment of gut epithelial barrier function is a key predisposing factor for inflammatory bowel disease, type 1 diabetes (T1D), and related autoimmune diseases. We hypothesized that maternal obesity induces gut inflammation and impairs epithelial barrier function in the offspring of non-obese diabetic (NOD) mice. 4-week-old female NOD/ShiLtJ mice were fed with a control diet (CON, 10% energy from fat) or a high fat diet (HFD, 60% energy from fat) for 8 weeks to induce obesity and then mated. During pregnancy and lactation, mice were maintained in their respective diets. After weaning, all offspring were fed the CON diet. At 16 weeks of age, female offspring were subjected to in vivo intestinal permeability test and, then, ileum was sampled for biochemical analyses. Inflammasome mediators, activated caspase-1 as well as mature forms of interleukin (IL) -1β and IL-18 were enhanced in offspring of obese mothers, which was associated with elevated serum tumor necrosis factor (TNF)α level and inflammatory mediators. Consistently, abundance of oxidative stress markers including catalase, peroxiredoxin-4 and superoxide dismutase 1 were heightened in offspring ileum (P < 0.05). Furthermore, offspring from obese mothers had a higher intestinal permeability. Morphologically, maternal obesity reduced villi/crypt ratio in the ileum of offspring gut. In conclusion, maternal obesity induced inflammation and impaired gut barrier function in offspring of NOD mice. The enhanced gut permeability in HFD offspring might pre-dispose them to the development of T1D and other gut permeability associated diseases.

Keywords: Maternal obesity, intestine, inflammation, oxidative stress, permeability, tight junction proteins, NOD, offspring

1. Introduction

Type 1 diabetes (T1D), also known as insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus, is a pancreatic autoimmune disease associated with the massive destruction of insulin producing β-cells. The incidence of T1D especially in children has been increasing in recent decades and is predicted to continue to rise in the future [1, 2]. Environmental factors are recognized as an important player in the etiology of T1D [3].

According to the latest NHANES survey (2009–2010), 31.9% of non-pregnant women at 20–39 years of age are obese, and another one third are overweight [4]. Maternal obesity (MO) predisposes offspring to inflammation-related disorders [5, 6]. A recent epidemiological human study indicated that maternal high body mass index (BMI > 30) was associated with increased risks of T1D [3]. However, little is known about mechanisms mediating the link between MO and offspring T1D.

Impaired gut epithelial integrity and barrier function are the central predisposing factors to autoimmune T1D, inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) and related allergic diseases [7–9]. Indeed, enhanced gut permeability is observed in patients with T1D and IBD [10, 11]. Gut inflammation is known to enhance epithelial permeability [12]. Inflammatory cytokines such as IL-13, interferon-γ (IFN-γ), and tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) increase gut permeability [13–15]. Inflammasomes are multiple protein complexes activated by inflammation [16]. Inflammasome complexes are composed of Nod-like receptor (NLR) family members [16]. NACHT, LRR and PYD domains-containing protein 3 (NLRP3) is a major type of inflammasomes, which regulate inflammatory responses by mediating IL-18 and IL-1β maturation [17]. The maturation of IL-18 and IL-1β is linked to intestinal inflammation and causally related to IBD development [18, 19].

Inflammasome is a key mediator of the chronic low-grade inflammation associated with obesity [20], while inflammation are usually associated with oxidative stress. Healthy gut is equipped with intricate anti-oxidative defense systems including enzymes such as superoxide dismutase (SOD), peroxiredoxin and catalase to remove reactive oxygen species; their imbalance is involved in the etiology of IBD [21]. We previously observed that MO resulted in exaggeration inflammation in the sheep progeny gut [5], but the possible involvement of inflammasome and oxidative stress in offspring gut inflammation due to MO is unknown. The objective of this study is to assess the impact of MO on intestinal epithelial barrier function in the offspring of NOD mice and further explore the underlying mechanisms. NOD mice were used because it is a well-established murine model for T1D so that our data on gut epithelial permeability can be correlated with the T1D incidence.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Animal care and experimental design

The animal care procedure was approved by the Institutional Animal Use and Care Committee, University of Wyoming. Forty three-week-old female NOD/ShiLtJ mice were obtained from Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME). Mice were housed in a temperature controlled room with a 12 h light: 12 h darkness cycle and were given food and water ad libitum. At 4 weeks of age, mice were randomly separated into two groups (n=20 per group) and fed either a control diet (CON, contains 19.2% protein, 67.3% carbohydrate and 4.3% fat with 10% energy from fat, D12450B, Research diet, New Brunswick, NJ) or a high fat diet (HFD, contains 26.2% protein, 26.3% carbohydrate and 34.9% fat with 60% of energy from fat, D12492, Research diet) at ad libitum, respectively for 8 weeks to induce obesity. Then these female mice were mated with male mice of a similar age, which had been fed the CON diet. Pregnant NOD mice were fed with their respective diets during gestation and lactation, to mimic the situation with humans. At birth, maternal mice with abnormal large (above 8) or small litter sizes (less than 4) were excluded, and the sizes of remaining litters were balanced to 6 pups per litter by reducing large and increasing small litters. After weaning, offspring of both CON and HFD fed dams were fed the CON diet ad libitum. To avoid the confounding effects of sex, only female offspring at 16-week-old were used in this study, which are known to be more susceptible to the development of T1D than male mice [22]. One female offspring mice was further selected from each littler for analyses associated with this study.

2.2. In vivo intestinal permeability test

An in vivo intestinal barrier assay was performed with FITC-labeled dextran as previously described [23]. Briefly, maternal mice before mating and 16-week-old NOD female offspring were deprived of food and water for 4 hr, and mice were gavaged with permeability tracer FITC-labeled dextran 4 kDa (0.6 mg/g body weight, Sigma, St. Louis, MO). Blood was collected 5 hr following gavage and centrifuged at 4,000 × g for 5 min. The resulting serum was 1:5 diluted in PBS, pH7.4 and fluorescence intensity of serum was measured at excitation, 490 nm; emission, 520 nm using SpectraMax M5 spectrophotometer (Molecule Device, Sunnyvale, CA).

2.3. Tissue collection

On the day of necropsy, mice were anesthetized intraperitoneally with tribromoethanol (250 mg/kg body weight). Blood samples were collected under anesthesia, and mice were sacrificed by cervical dislocation. The terminal ileum was dissected, and a 5 mm ileum tissue section at the constant location was fixed in 4% (w/v) paraformaldehyde, pH7.0, processed and embedded into paraffin per standard method. The remaining ileum segment was cut open, rinsed in PBS, frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at −80 °C for further biochemical analyses.

2.4. Lipopolysaccharide (LPS) and TNF-α measurement

Plasma LPS level was assessed by an Endotoxin Assay kit using limulus amoebocyte extract (Cambrex Bioscience, Walkersville, MD, USA) per manufacture’s manual. Serum levels of TNF-α were analyzed by ELISA (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA) according to the manufacturer protocol.

2.5. Quantitative reverse transcriptase PCR (qRT-PCR) analyses

Total RNA was extracted from ileum tissues using Trizol®Reagent (Sigma, St. Louis, MO), treated with DNase I (Qiagen) and purified with an RNeasy Mini kit (Qiagen). cDNA was synthesized with the SuperScriptTM III first-strand synthesis kit (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). qRT-PCR was conducted on a Bio-Rad CFX96 real time PCR machine as described previously [24]. The mRNA expression of selected genes related to inflammation, oxidative stress and epithelial tight junctions was analyzed and the primer sequences for genes analyzed are listed in Table 1. Mouse glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) was used as the housekeeping gene. Primer sequences are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Primer sets used for quantitative RT-PCR analyses

| Gene Name | Accession No. |

Product Size |

Direction | Sequence (5’→3’) | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Capase1 | NM_009807.2 | 111bp | Forward | ACTGACTGGGACCCTCAAGT | This study |

| Reverse | GCAAGACGTGTACGAGTGGT | ||||

| Catalase | NM_009804.2 | 181bp | Forward | AGCGACCAGATGAAGCAGTG | [56] |

| Reverse | TCCGCTCTCTGTCAAAGTGTG | ||||

| Claudin2 | M_016675.4 | 120bp | Forward | GGCGTCCAACTGGTGGGCTAC | [57] |

| Reverse | AACCGCCGTCACAATGCTGGC | ||||

| GPADH | NM_008084.2 | 132bp | Forward | AACTTTGGCATTGTGGAAGG | [24] |

| Reverse | GGATGCAGGGATGATGTTCT | ||||

| IL-1β | NM_008361.3 | 77bp | Forward | TCGCTCAGGGTCACAAGAAA | [58] |

| Reverse | CATCAGAGGCAAGGAGGAAAAC | ||||

| IL-6 | NM_031168.1 | 107bp | Forward | GCTGGTGACAACCACGGCCT | [24] |

| Reverse | AGCCTCCGACTTGTGAAGTGGT | ||||

| IL-18 | NM_008360.1 | 89bp | Forward | ATGCTTTCTGGACTCCTGCCTGCT | This study |

| Forward | GGCGGCTTTCTTTGTCCTGATGCT | ||||

| NLRP3 | NM_145827.3 | 116bp | Forward | TCCCAGACACTCATGTTGCC | This study |

| Reverse | GTCCAGTTCAGTGAGGCTCC | ||||

| Peroxiredoxin-4 | NM_016764.4 | 78bp | Forward | TGTCGGAAGATCAGTGGACG | This study |

| Reverse | GGGCAGACTTCTCCATGCTT | ||||

| SOD1 | NM_011434.1 | 139bp | Forward | AACCAGTTGTGTTGTCAGGAC | [56] |

| Reverse | CCACCATGTTTCTTAGAGTGAGG | ||||

| TGF-β1 | NM_011577.1 | 148bp | Forward | TCCTTGCCCTCTACAACCAACACA | This study |

| Reverse | TTGCAGGAGCGCACAATCATGT | ||||

| TLR4 | NM_021297.2 | 98bp | Forward | AGTGCCCCGCTTTCACCTCT | This study |

| Reverse | TCCGGCTCTTGTGGAAGCCT | ||||

| ZO-1 | NM_009386.2 | 403bp | Forward | ACCCGAAACTGATGCTGTGGATAG | [58] |

| Reverse | AAATGGCCGGGCAGAACTTGTGTA | ||||

| ZO-2 | AF113005.1 | 106bp | Forward | CCCAGCACCAAGCCACCTTTTCA | [24] |

| Reverse | TCGGTTAGGGCAGACACACTCCC | ||||

| ZO-3 | AF157006.1 | 82bp | Forward | ATCCGAGGACCTTGACCTGACGG | This study |

| Reverse | GTCGCTGTTGGTCCGACTGTCAC |

2.6. Immunoblotting analyses

Immunoblotting analysis was conducted as previously described [5, 24]. Antibodies against interleukin (IL)-1β, phospho-myosin light chain (MLC) 2, CK2 and catalase were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology (Beverly, MA). Antibodies against claudin2 were purchased from Invitrogen (Camarillo, CA). Caspase-1 antibody was purchased from Millipore (Billerica, MA). NLRP3 antibody was purchased from Boster Biological (Fremont, CA). IL-18 and perroxiredoxin-4 antibody was purchased from DSHB (University of Iowa, Department of Biology). GAPDH antibody was purchased from GeneTex Inc. (Irvine, CA) while SOD1 antibody was purchased from Santa Cruz Biotech Inc. (Santa Cruz, CA). Density of bands was quantified and then normalized with reference to the GAPDH content.

2.7. Histological examination

Paraffin embedded terminal ileum was sectioned into 5 µm thickness and subjected to Alcian blue staining for measuring goblet cell density [25], The number of intestinal goblet cells per villus was counted in a double blind manner. More than 50 villi over 450 µm interval were examined for each animal. The villus: crypt ratio of ileum mucosa was determined by measuring villus height and crypt depth in at least 15 representative, well-oriented villi per mouse in a blinded manner.

2.8. Caspase-1 activity assays

Caspase-1 activity was assayed by Caspase-1 Fluorometric Assay Kit from BioVision Incorporated (Milpitas, CA). Briefly, ileum tissues were homogenized in lysis buffer at 1:40 (w/v) ratio. Homogenized tissues were centrifuged at 3,000×g for 5 min at 4°C, and 50 µl supernatant was used for measuring caspase-1 activity using the YVAD-AFC substrate (50 µM final concentration) per manufacturer instruction.

2.9. Statistical Analysis

Data were analyzed as a complete randomized design using GLM (General Linear Model of Statistical Analysis System, SAS, 2000). Means ± standard errors of mean (SEM) are reported. Statistical significance is considered as P < 0.05. A trend of difference is considered as P < 0.10.

3. Results

3.1. Obese phenotype was correlated with altered intestinal function in pregnant NOD mice

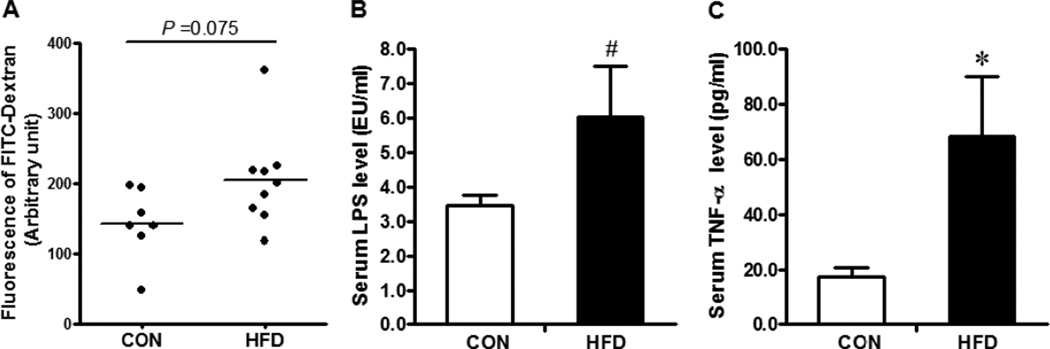

There was no significant difference in feed intake between Con and HFD groups. Pregnant NOD mice fed with HFD developed obesity after 8 wks of dietary treatment (Con vs. HFD: 21.8 ± 0.52g vs. 27.66 ± 0.74g, P < 0.01). Obese maternal NOD mice at mating had a tendency for increased gut epithelial permeability (Fig.1 A, P < 0.1) and the serum LPS level (Fig1 B; P < 0.1). The serum LPS level is known to be correlated with gut epithelial permeability, and LPS stimulates inflammation via Toll like receptors [26]. The increased serum LPS level in maternal obese mice might partially explain enhanced gut permeability as well as the system inflammation, as indicated by increased serum TNF-α level (Fig. 1C, P < 0.05).

Fig. 1.

Maternal gut permeability and systemic inflammation after feeding 8 weeks of CON (□) or HFD (■) diet. A. Maternal in vivo intestinal permeability measured with permeability tracer FITC-labeled dextran; B. Serum lipopolysaccaride (LPS) level by an Endotoxin Assay Kit; C. Serum TNF-α level by ELISA. *: P < 0.05; #: P < 0.10; Mean ± SEM; n = 8.

3.2. Impaired intestinal barrier function in female offspring ileum of obese dam

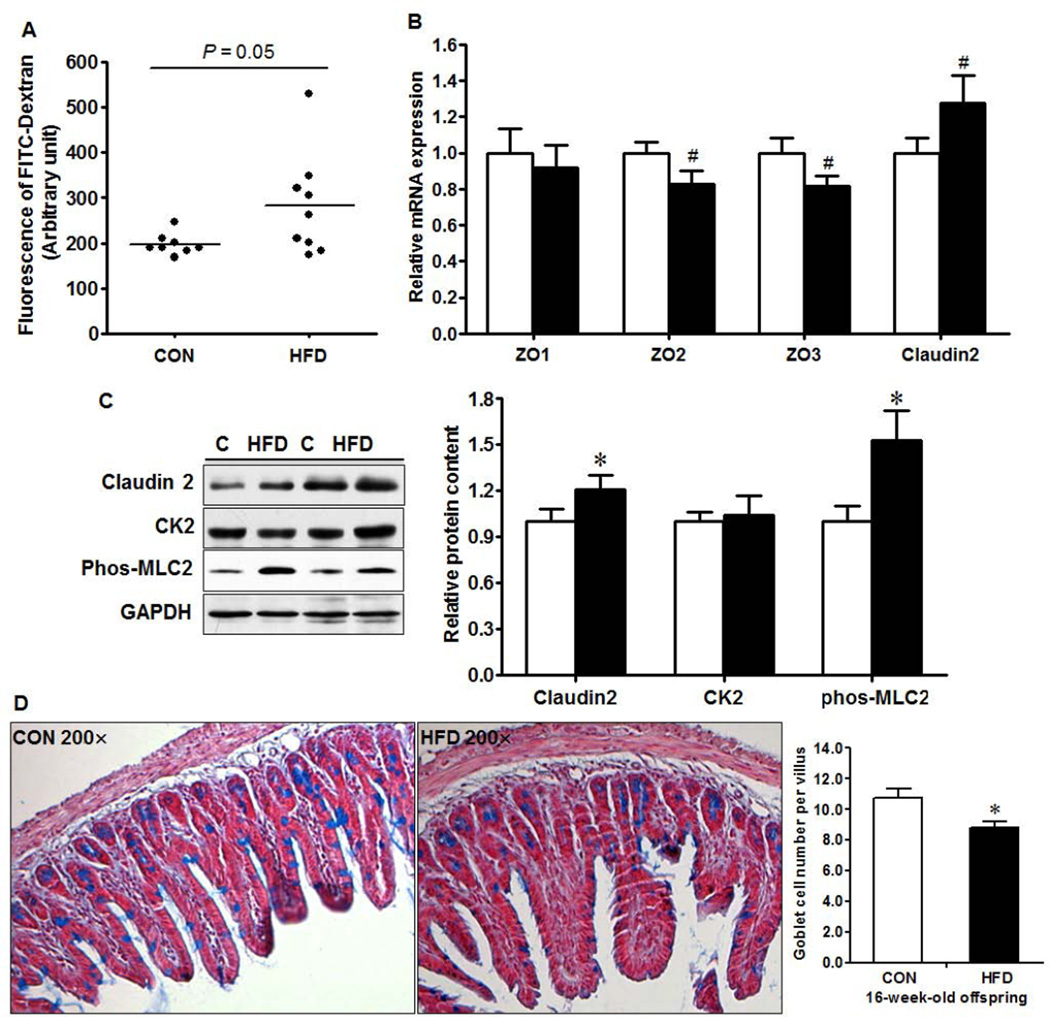

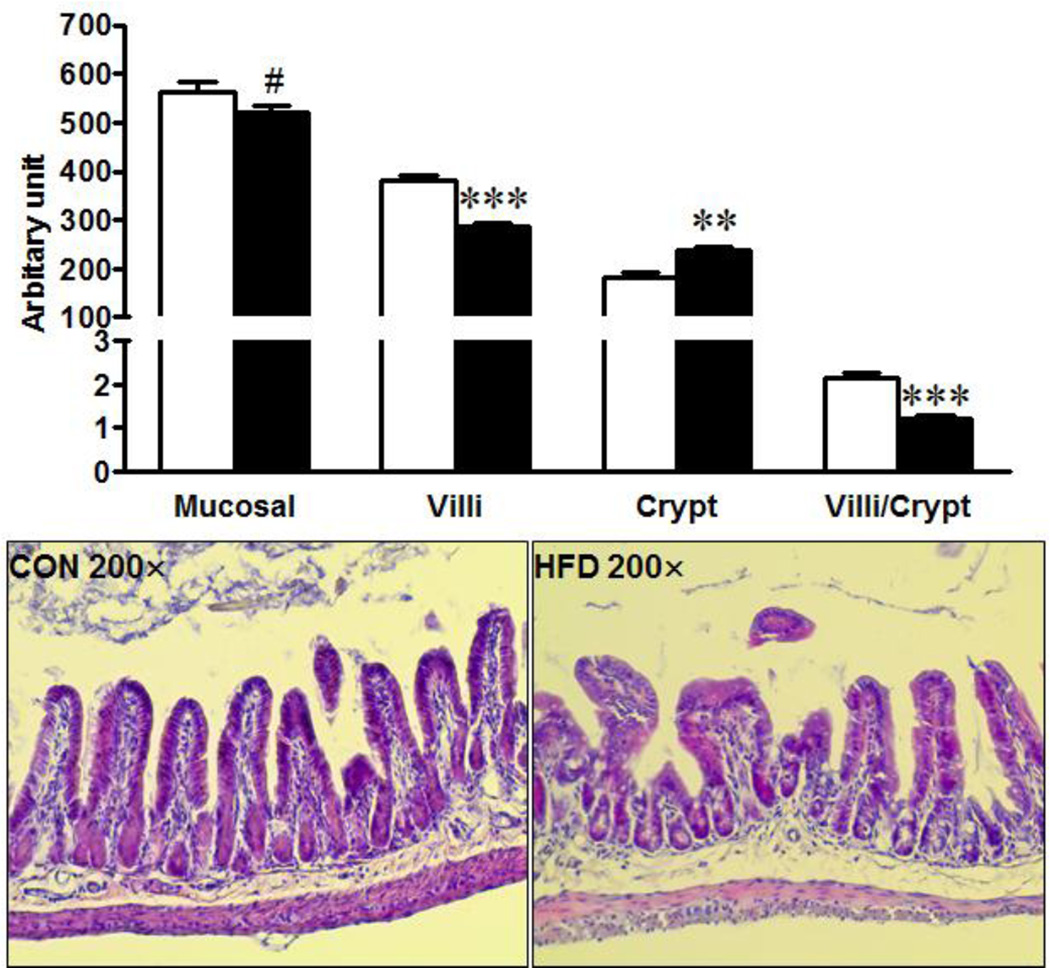

Maternal obesity resulted in an increased (P = 0.05, Fig. 2A) intestinal permeability in 16-week-old female offspring. Zonula Occluden (ZO)-2 and ZO-3 are two important tight junction proteins that regulate intercellular tight junction. Consistently, there was a trend of decreased ZO-2 and ZO-3 mRNA expression and increased pore forming claudin-2 at both mRNA (Fig. 2B, P < 0.10) and protein levels (Fig. 2C, P < 0.05) in MO female offspring. Myosin light chain kinase (MLCK) phosphorylates the regulatory myosin light chain (MLC-2) and activation of MLCK impairs intestinal barrier function [27]. In agreement, the MLC2 phosphorylation was higher in the ileum of MO female offspring (Fig. 2C). Protein kinase CK2 was reported to play an important role in intestinal epithelial homeostasis [28], however, there was no difference in CK2 protein content (Fig. 2C). In addition, the intestinal mucosal layer is crucial in maintaining gut integrity. The density of goblet cells, a major source of secreted mucin in the gastrointestinal tract, per villus was reduced (Fig. 2D, P < 0.01) in the ileum of MO offspring. Furthermore, morphologically, villus height was reduced (P < 0.001) while crypt depth (P < 0.01) was increased in the ileum of offspring experienced MO (Fig. 3), resulting in dramatically decreased villus to crypt ratio (Fig. 3).

Fig. 2.

Impaired intestinal barrier function in 16-week-old female offspring born to CON (□) and HFD (■) mothers. A. in vivo intestinal permeability, B. mRNA expression of tight junction proteins by qRT-PCR; C. Relative protein content of tight junction proteins and associated signaling: Representative western blotting bands (Left) and statistical data (Right); D. Goblet cell density in the ileum: Representative images of terminal ileum by light microscope (Left) and statistical data (Right). *: P < 0.05; #: P < 0.10; Mean ± SEM; n = 8.

Fig. 3.

Mucosal length, villus height and crypt depth in offspring born to Con (□) or HFD (■) mothers. Mean ± SEM; ***: P < 0.001; **: P < 0.01; #: P < 0.10; n = 8.

3.3. Enhanced inflammatory responses in ileum of MO female offspring

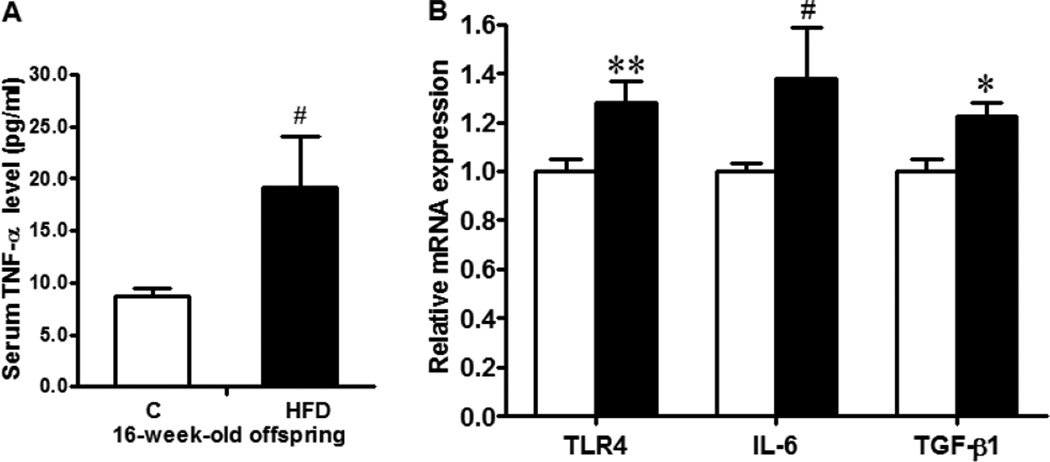

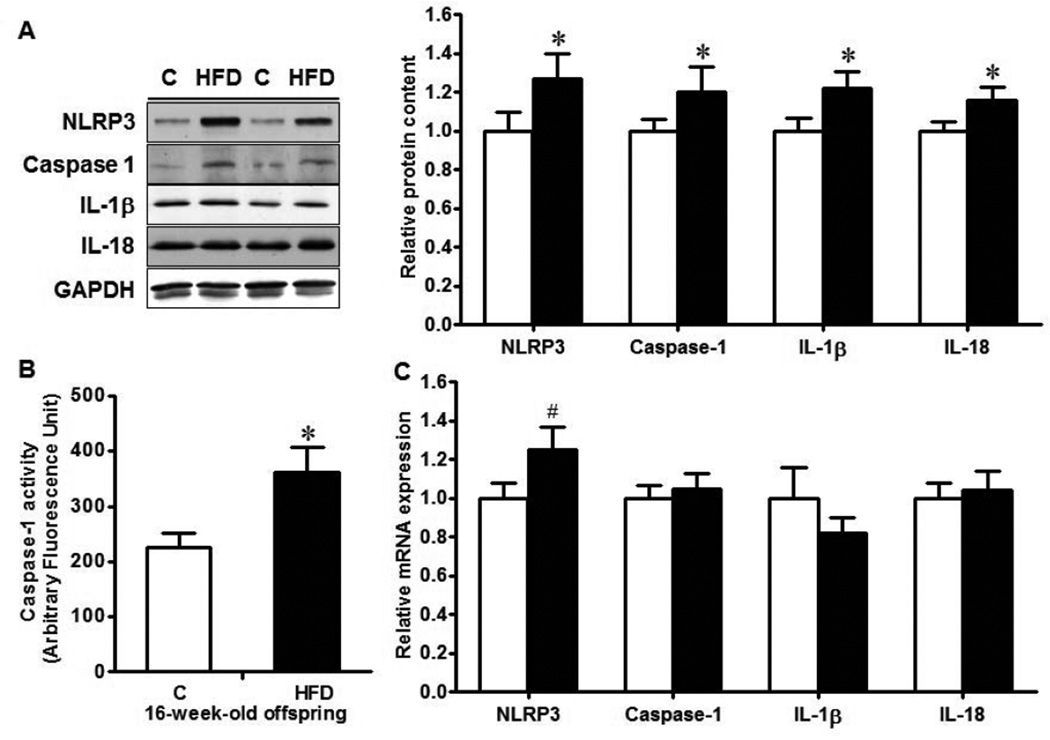

The ileum tissues of MO offspring mice experienced exaggerated inflammatory response with increased serum TNF-α level (Fig. 4A, P < 0.1), as well as enhanced TLR4 (P < 0.01), TGF-β (P < 0.05) and IL-6 (P < 0.1) levels (Fig. 4B). Inflammasomes are important molecular platforms that regulate inflammation and are responsible for the processing of inflammatory cytokines IL-1β and IL-18. Thus, we further analyzed NLRP3 inflammasome, the major inflammasome system regulating inflammatory responses. As expected, the protein level of NLRP3 was elevated in MO offspring ileum compared with their control counterpart (P < 0.05, Fig. 5A), whereas the mRNA level of NLRP3 was tended to increase (P < 0.10, Fig. 5C) in MO offspring ileum. In line with, the activity of caspase-1 was higher in MO offspring ileum (P < 0.05, Fig. 5A&B), and the final products of NLRP3 inflammasome, mature IL-1β and IL-18, were both increased in MO offspring ileum (P < 0.05, Fig. 5A).

Fig. 4.

Inflammatory response in the ileum of 16-week-old female offspring born to Con (□) or HFD (■) mothers. A. Serum TNF-α level measured by ELISA; B. Relative mRNA expression of TLR4, IL-6 and TGF-β. **: P < 0.01; *: P < 0.05; #: P < 0.10; Mean ± SEM; n = 8.

Fig. 5.

Inflammasome mediators in the ileum of 16-week-old female offspring born to Con (□) or HFD (■) mothers. A. Western blotting analysis of inflammasome mediators: representative bands (Left) and Statistical data (Right); B. Caspase-1 activity using a Fluorometric Assay Kit; C. mRNA expression of inflammasome mediators. *: P < 0.05; #: P < 0.10; Mean ± SEM; n = 8.

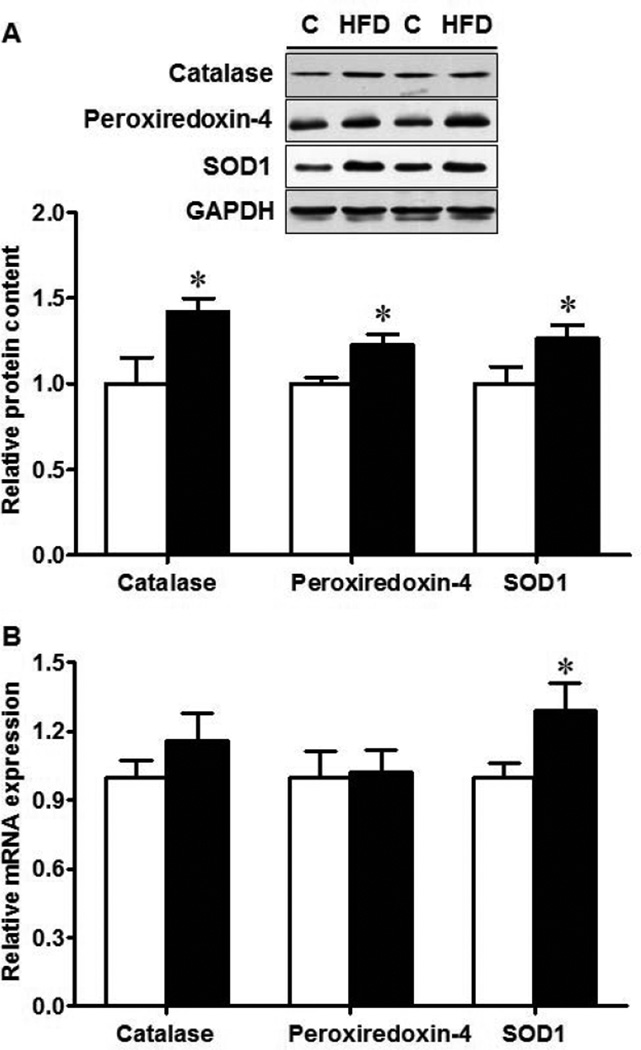

3.4. Enzymatic antioxidants were increased in the ileum of MO female offspring

Oxidative stress is a potential etiological factor for IBD [21]. SOD1 is a vital enzyme responsible for catalyzing the decomposition of superoxide radicals into oxygen and hydrogen peroxide, while catalase and peroxiredoxin further catalyze and decompose hydrogen peroxide into water and oxygen. Thus, we further evaluate the status of these enzymatic antioxidants. Protein content of catalase, peroxiredoxin-4 and SOD1 were all higher in MO offspring ileum (Fig. 6 A, P < 0.05), so was SOD1 mRNA expression (P < 0.05, Fig. 6B).

Fig. 6.

Enzymatic antioxidants in the ileum of 16-week-old female offspring born to Con (□) or HFD (■) mothers. A. Western blotting analysis; B. mRNA expression. *: P < 0.05; Mean ± SEM; n = 8.

4. Discussion

Maternal obesity programs offspring to obesity [29], hyperglycemia/hyperinsulinemia [30], hypertension [31], cardiovascular diseases [32] and other diseases/disorders. Impairment of gut epithelial barrier function is the central predisposing factor to the incidence of autoimmune T1D, IBD and related allergic diseases [7–9], but information regarding to the impact of MO on offspring gastrointestinal integrity is underexplored. Previously, we found that MO induces inflammation in the large intestine of sheep progeny [5]. Consistently, the present study showed that MO enhanced inflammatory responses in the ileum of NOD female offspring mice. MO impaired intestinal barrier function in offspring, which is associated with decreased goblet cells, increased claudin 2 content and increased phosphorylation of MLC2, all of which are commonly associated with impaired barrier function [27, 33, 34]. The gut system is the first line of defence to oral antigens by either launching immune response or developing tolerance. Accumulating evidences suggest that impaired intestinal barrier function contributes to the development of insulitis, an indicator for autoimmune T1D in NOD mice. This barrier function impairment in NOD offspring experienced MO provides a possible explanation of the exacerbated inisulitis observed in these MO NOD offspring [35]. In consistency, dietary antigens including wheat gluten lead to barrier dysfunction and skew to Th1 immune response, promoting T1D development [36, 37]. Damage to intestinal barrier integrity caused by C. rodentium infection, accelerates the insulitis by priming CD8+ T cells in NOD mice [38].

Inflammasomes are key regulators of inflammation. NLRP3 inflammasomes are one of the major inflammasome complexes and mediate the proteolytical maturation of cytokines, IL-1β and IL-18 [39]. It plays a crucial role in the regulation of intestinal homeostasis [40, 41]. In dextran sulfate sodium (DSS) induced murine colitis, gut tissue exhibited active NLRP3 recruitment and caspase-1-dependent activation of IL-1β and IL-18 [40], while Nlrp3−/− mice are more susceptible to DSS or 2,4,6-trinitrobenzenesulfonic acid (TNBS) induced colitis [41]. Herein, we observed that MO resulted in higher activation of NLRP3 inflammasome accompanied with enhanced activation of caspase-1 and production of mature IL-1β and IL-18, showing enhanced inflammasome formation in MO offspring gut. While IL-1β and IL-18 play an essential role in host defense, excessive production of IL-1β and IL-18 contributes to the pathogenesis of IBD and other chronic inflammatory diseases [42, 43], which might be partially responsible for impaired intestinal barrier function in NOD offspring ileum due to MO. TGF-β is an important immunosuppressive cytokine associated with inflammation, which stimulates fibrosis [44]. In alignment, we found enhanced TGF-β in ileum of MO NOD offspring, which is consistent with our previous study in sheep [5], as well as a study of CD patients, where TGF-β expression correlates with collagen accumulation in the gut [44].

The epithelium of the small intestine contains crypts and villi, which is highly dynamic. The crypts are developmental units where new epithelial cells are constantly generated through the proliferation of stem cells residing at the bottom of each crypt. These new generated cells migrate along the crypt-villus axis, differentiate and shed at the tip of villus. Altered villus/crypt ratio is correlated with various immune-related bowel diseases [45]. Interestingly, MO led to increased crypt depth while reducing villus height, which is consistent with the enhanced inflammation in MO offspring gut, and also in agreement with the intestinal morphological changes associated with DSS induced colitis [46], where ileum crypt depth was greater in DSS treated mice. Increased crypt depth and reduced villus/crypt ratio probably results from enhanced epithelial turnover triggered by inflammation, which warrants further studies.

Intestinal damage in IBD is partly associated with chronic oxidative stress and enhanced exposure to reactive oxygen species (ROS) [47, 48]. In order to counterbalance excessive ROS, organisms rely on a number of anti-oxidant systems including SOD, peroxiredoxin and catalase to act as protective mechanisms. In the anti-oxidant defense mechanisms, SOD acts as a primary superoxide anion scavenger that converts O2−• into H2O2 [49], and its expression is correlated with anti-oxidative capacity [50]. However, an increase of SOD content is not always associated with a high resistance to oxidation. In IBD patients, inflamed intestinal mucosal section contained a higher SOD protein level than that of non-flamed and normal tissues [47]. Patients suffered from Crohn's disease exhibited an elevated activity of SOD compared with healthy controls [51]. In addition, mice overexpressing SOD exhibited elevated inflammatory damage and tissue injury in responses to DSS treatment [52]. Along this line, we observed that both SOD1 mRNA and protein levels were increased in the ileum of MO offspring. This might indicate a counterbalance effort of the organism to neutralize excessive ROS production associated with inflammation.

As a secondary oxidative defensive line, catalase and peroxiredoxin act synergistically with SOD to remove H2O2 and counterbalance excessive ROS [49]. Peroxiredoxin 4 is a major anti-oxidative enzyme in the peroxiredoxin family, which has been used as an oxidative stress biomarker in chronic diseases such as cancers [53, 54]. In line with increased SOD production, both catalase and peroxiredoxin 4 were increased in the ileum of MO offspring. Up-regulation of these enzymatic antioxidants might be part of anti-oxidative defense mechanisms aroused in response to oxidative damage caused by MO. On the other hand, excessive ROS can in turn enhanced IL-1β secretion through inducing NLRP3 inflammasome [40]. Consistently, SOD1 knockout in mouse suppresses the activation of NLRP3 inflammasome, producing less caspase-1-dependent proinflammatory cytokines and are more resistant to lipopolysaccharide challenge [55]. In the current study, three anti-oxidative enzymes are increased in MO offspring gut, which is consistent with enhanced activation of inflammasome in MO offspring.

Taken together, our findings indicated that MO impaired offspring barrier function through enhancing inflammatory response, inflammasome activation and oxidative stress, which likely predisposes MO offspring to develop insulitis and T1D.

Acknowledgement

The authors would like to acknowledge Mr. David Hanna for taking care of mice and facilitating experiments.

Funding

Funding was supported by USDA-AFRI 2009-65203-05716 and NIH R15HD073864.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Declaration of interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest that could be perceived as prejudicing the impartiality of the research reported.

References

- 1.Negrato CA, Dias JP, Teixeira MF, Dias A, Salgado MH, Lauris JR, et al. Temporal trends in incidence of Type 1 diabetes between 1986 and 2006 in Brazil. J Endocrinol Invest. 2010;33:373–377. doi: 10.1007/BF03346606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sobel-Maruniak A, Grzywa M, Orlowska-Florek R, Staniszewski A. The rising incidence of type 1 diabetes in south-eastern Poland A study of the 0–29 year-old age group, 1980–1999. Endokrynol Pol. 2006;57:127–130. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.D'Angeli MA, Merzon E, Valbuena LF, Tirschwell D, Paris CA, Mueller BA. Environmental factors associated with childhood-onset type 1 diabetes mellitus: an exploration of the hygiene and overload hypotheses. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2010;164:732–738. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2010.115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Flegal KM, Carroll MD, Kit BK, Ogden CL. Prevalence of obesity and trends in the distribution of body mass index among US adults, 1999–2010. JAMA. 2012;307:491–497. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yan X, Huang Y, Wang H, Du M, Hess BW, Ford SP, et al. Maternal obesity induces sustained inflammation in both fetal and offspring large intestine of sheep. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2011;17:1513–1522. doi: 10.1002/ibd.21539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bilbo SD, Tsang V. Enduring consequences of maternal obesity for brain inflammation and behavior of offspring. FASEB J. 2010;24:2104–2115. doi: 10.1096/fj.09-144014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jager S, Stange EF, Wehkamp J. Inflammatory bowel disease: an impaired barrier disease. Langenbecks Arch Surg. 2013;398:1–12. doi: 10.1007/s00423-012-1030-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vaarala O. Is the origin of type 1 diabetes in the gut? Immunol Cell Biol. 2012;90:271–276. doi: 10.1038/icb.2011.115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yu LC. The epithelial gatekeeper against food allergy. Pediatr Neonatol. 2009;50:247–254. doi: 10.1016/S1875-9572(09)60072-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bosi E, Molteni L, Radaelli MG, Folini L, Fermo I, Bazzigaluppi E, et al. Increased intestinal permeability precedes clinical onset of type 1 diabetes. Diabetologia. 2006;49:2824–2827. doi: 10.1007/s00125-006-0465-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Irvine EJ, Marshall JK. Increased intestinal permeability precedes the onset of Crohn's disease in a subject with familial risk. Gastroenterology. 2000;119:1740–1744. doi: 10.1053/gast.2000.20231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ohman L, Simren M. Pathogenesis of IBS: role of inflammation, immunity and neuroimmune interactions. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;7:163–173. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2010.4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Weber CR, Raleigh DR, Su L, Shen L, Sullivan EA, Wang Y, et al. Epithelial myosin light chain kinase activation induces mucosal interleukin-13 expression to alter tight junction ion selectivity. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:12037–12046. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.064808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schulzke JD, Ploeger S, Amasheh M, Fromm A, Zeissig S, Troeger H, et al. Epithelial tight junctions in intestinal inflammation. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2009;1165:294–300. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.04062.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ma TY, Iwamoto GK, Hoa NT, Akotia V, Pedram A, Boivin MA, et al. TNF-alpha-induced increase in intestinal epithelial tight junction permeability requires NF-kappa B activation. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2004;286:G367–G376. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00173.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lamkanfi M, Dixit VM. Inflammasomes and Their Roles in Health and Disease. Annu Rev Cell Dev Bi, Vol 28. 2012;28:137–161. doi: 10.1146/annurev-cellbio-101011-155745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vande Walle L, Lamkanfi M. Inflammasomes: caspase-1-activating platforms with critical roles in host defense. Front Microbiol. 2011;2:3. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2011.00003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mahida YR, Wu K, Jewell DP. Enhanced production of interleukin 1-beta by mononuclear cells isolated from mucosa with active ulcerative colitis of Crohn's disease. Gut. 1989;30:835–838. doi: 10.1136/gut.30.6.835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pizarro TT, Michie MH, Bentz M, Woraratanadharm J, Smith MF, Jr, Foley E, et al. IL-18, a novel immunoregulatory cytokine, is up-regulated in Crohn's disease: expression and localization in intestinal mucosal cells. J Immunol. 1999;162:6829–6835. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stienstra R, van Diepen JA, Tack CJ, Zaki MH, van de Veerdonk FL, Perera D, et al. Inflammasome is a central player in the induction of obesity and insulin resistance. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:15324–15329. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1100255108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rezaie A, Parker RD, Abdollahi M. Oxidative stress and pathogenesis of inflammatory bowel disease: an epiphenomenon or the cause? Dig Dis Sci. 2007;52:2015–2021. doi: 10.1007/s10620-006-9622-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wicker LS, Todd JA, Peterson LB. Genetic control of autoimmune diabetes in the NOD mouse. Annu Rev Immunol. 1995;13:179–200. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.13.040195.001143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vijay-Kumar M, Sanders CJ, Taylor RT, Kumar A, Aitken JD, Sitaraman SV, et al. Deletion of TLR5 results in spontaneous colitis in mice. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:3909–3921. doi: 10.1172/JCI33084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wang H, Zhao JX, Hu N, Ren J, Du M, Zhu MJ. Side-stream smoking reduces intestinal inflammation and increases expression of tight junction proteins. World J Gastroenterol. 2012;18:2180–2187. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v18.i18.2180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pellegrinet L, Rodilla V, Liu Z, Chen S, Koch U, Espinosa L, et al. Dll1- and dll4-mediated notch signaling are required for homeostasis of intestinal stem cells. Gastroenterology. 2011;140:1230–1240. e1–e7. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.01.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Seki E, Schnabl B. Role of innate immunity and the microbiota in liver fibrosis: crosstalk between the liver and gut. J Physiol. 2012;590:447–458. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2011.219691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ferrier L, Mazelin L, Cenac N, Desreumaux P, Janin A, Emilie D, et al. Stress-induced disruption of colonic epithelial barrier: role of interferon-gamma and myosin light chain kinase in mice. Gastroenterology. 2003;125:795–804. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(03)01057-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Koch S, Capaldo CT, Hilgarth RS, Fournier B, Parkos CA, Nusrat A. Protein kinase CK2 is a critical regulator of epithelial homeostasis in chronic intestinal inflammation. Mucosal Immunol. 2013;6:136–145. doi: 10.1038/mi.2012.57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shankar K, Harrell A, Liu X, Gilchrist JM, Ronis MJ, Badger TM. Maternal obesity at conception programs obesity in the offspring. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2008;294:R528–R538. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00316.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Khalyfa A, Carreras A, Hakim F, Cunningham JM, Wang Y, Gozal D. Effects of late gestational high-fat diet on body weight, metabolic regulation and adipokine expression in offspring. Int J Obes (Lond) 2013;37:1481–1489. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2013.12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Guberman C, Jellyman JK, Han G, Ross MG, Desai M. Maternal high-fat diet programs rat offspring hypertension and activates the adipose renin-angiotensin system. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2013 doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2013.05.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Khan I, Dekou V, Hanson M, Poston L, Taylor P. Predictive adaptive responses to maternal high-fat diet prevent endothelial dysfunction but not hypertension in adult rat offspring. Circulation. 2004;110:1097–1102. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000139843.05436.A0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wang H, Xue Y, Zhang H, Huang Y, Yang G, Du M, et al. Dietary grape seed extract ameliorates symptoms of inflammatory bowel disease in IL10-deficient mice. Mol Nutr Food Res. 2013;57:2253–2257. doi: 10.1002/mnfr.201300146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Al-Sadi R, Ye D, Said HM, Ma TY. IL-1beta-induced increase in intestinal epithelial tight junction permeability is mediated by MEKK-1 activation of canonical NF-kappaB pathway. Am J Pathol. 2010;177:2310–2322. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2010.100371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wang H, Xue Y, Wang B, Zhao J, Yan X, Huang Y, et al. Maternal obesity exacerbates insulitis and type I diabetes in non-obese diabetic (NOD) mice. Reproduction. 2014 doi: 10.1530/REP-13-0614. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Flohe SB, Wasmuth HE, Kerad JB, Beales PE, Pozzilli P, Elliott RB, et al. A wheat-based, diabetes-promoting diet induces a Th1-type cytokine bias in the gut of NOD mice. Cytokine. 2003;21:149–154. doi: 10.1016/s1043-4666(02)00486-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Maurano F, Mazzarella G, Luongo D, Stefanile R, D'Arienzo R, Rossi M, et al. Small intestinal enteropathy in non-obese diabetic mice fed a diet containing wheat. Diabetologia. 2005;48:931–937. doi: 10.1007/s00125-005-1718-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lee AS, Gibson DL, Zhang Y, Sham HP, Vallance BA, Dutz JP. Gut barrier disruption by an enteric bacterial pathogen accelerates insulitis in NOD mice. Diabetologia. 2010;53:741–748. doi: 10.1007/s00125-009-1626-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sutterwala FS, Ogura Y, Szczepanik M, Lara-Tejero M, Lichtenberger GS, Grant EP, et al. Critical role for NALP3/CIAS1/cryopyrin in innate and adaptive immunity through its regulation of caspase-1. Immunity. 2006;24:317–327. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2006.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bauer C, Duewell P, Mayer C, Lehr HA, Fitzgerald KA, Dauer M, et al. Colitis induced in mice with dextran sulfate sodium (DSS) is mediated by the NLRP3 inflammasome. Gut. 2010;59:1192–1199. doi: 10.1136/gut.2009.197822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hirota SA, Ng J, Lueng A, Khajah M, Parhar K, Li Y, et al. NLRP3 inflammasome plays a key role in the regulation of intestinal homeostasis. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2011;17:1359–1372. doi: 10.1002/ibd.21478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Monteleone G, Trapasso F, Parrello T, Biancone L, Stella A, Iuliano R, et al. Bioactive IL-18 expression is up-regulated in Crohn's disease. J Immunol. 1999;163:143–147. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Agostini L, Martinon F, Burns K, McDermott MF, Hawkins PN, Tschopp J. NALP3 forms an IL-1beta-processing inflammasome with increased activity in Muckle-Wells autoinflammatory disorder. Immunity. 2004;20:319–325. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(04)00046-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Di Sabatino A, Jackson CL, Pickard KM, Buckley M, Rovedatti L, Leakey NA, et al. Transforming growth factor beta signalling and matrix metalloproteinases in the mucosa overlying Crohn's disease strictures. Gut. 2009;58:777–789. doi: 10.1136/gut.2008.149096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ruemmele FM, Seidman EG. Cytokine--intestinal epithelial cell interactions: implications for immune mediated bowel disorders. Zhonghua Min Guo Xiao Er Ke Yi Xue Hui Za Zhi. 1998;39:1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Geier MS, Smith CL, Butler RN, Howarth GS. Small-intestinal manifestations of dextran sulfate sodium consumption in rats and assessment of the effects of Lactobacillus fermentum BR11. Dig Dis Sci. 2009;54:1222–1228. doi: 10.1007/s10620-008-0495-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kruidenier L, Kuiper I, van Duijn W, Marklund SL, van Hogezand RA, Lamers CB, et al. Differential mucosal expression of three superoxide dismutase isoforms in inflammatory bowel disease. J Pathol. 2003;201:7–16. doi: 10.1002/path.1407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kruidenier L, Kuiper I, Van Duijn W, Mieremet-Ooms MA, van Hogezand RA, Lamers CB, et al. Imbalanced secondary mucosal antioxidant response in inflammatory bowel disease. J Pathol. 2003;201:17–27. doi: 10.1002/path.1408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Michiels C, Raes M, Toussaint O, Remacle J. Importance of Se-glutathione peroxidase, catalase, and Cu/Zn-SOD for cell survival against oxidative stress. Free Radic Biol Med. 1994;17:235–248. doi: 10.1016/0891-5849(94)90079-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Conner EM, Grisham MB. Inflammation, free radicals, and antioxidants. Nutrition. 1996;12:274–277. doi: 10.1016/s0899-9007(96)00000-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Beltran B, Nos P, Dasi F, Iborra M, Bastida G, Martinez M, et al. Mitochondrial dysfunction, persistent oxidative damage, and catalase inhibition in immune cells of naive and treated Crohn's disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2010;16:76–86. doi: 10.1002/ibd.21027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Krieglstein CF, Cerwinka WH, Laroux FS, Salter JW, Russell JM, Schuermann G, et al. Regulation of murine intestinal inflammation by reactive metabolites of oxygen and nitrogen: divergent roles of superoxide and nitric oxide. J Exp Med. 2001;194:1207–1218. doi: 10.1084/jem.194.9.1207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Schulte J, Struck J, Kohrle J, Muller B. Circulating Levels of Peroxiredoxin 4 as a Novel Biomarker of Oxidative Stress in Patients with Sepsis. Shock. 2011;35:460–465. doi: 10.1097/SHK.0b013e3182115f40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Basu A, Banerjee H, Rojas H, Martinez SR, Roy S, Jia ZY, et al. Differential Expression of Peroxiredoxins in Prostate Cancer: Consistent Upregulation of PRDX3 and PRDX4. Prostate. 2011;71:755–765. doi: 10.1002/pros.21292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Meissner F, Molawi K, Zychlinsky A. Superoxide dismutase 1 regulates caspase-1 and endotoxic shock. Nat Immunol. 2008;9:866–872. doi: 10.1038/ni.1633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wellen KE, Fucho R, Gregor MF, Furuhashi M, Morgan C, Lindstad T, et al. Coordinated regulation of nutrient and inflammatory responses by STAMP2 is essential for metabolic homeostasis. Cell. 2007;129:537–548. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.02.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wang H, Xue Y, Zhang H, Huang Y, Yang G, Du M, et al. Dietary grape seed extract ameliorates symptoms of inflammatory bowel disease in IL10-deficient mice. Mol Nutr Food Res. 2013 doi: 10.1002/mnfr.201300146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Cani PD, Bibiloni R, Knauf C, Waget A, Neyrinck AM, Delzenne NM, et al. Changes in gut microbiota control metabolic endotoxemia-induced inflammation in high-fat diet-induced obesity and diabetes in mice. Diabetes. 2008;57:1470–1481. doi: 10.2337/db07-1403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]