Abstract

Tissue transglutaminase (TG2) is a multifunctional enzyme involved in protein cross-linking and cell adhesion to fibronectin (FN). In cancer, TG2 induces an epithelial to mesenchymal transition, contributing to metastasis. Because cadherins bind β-catenin at cell-cell junctions, disruption of adherens junctions destabilizes cadherin-catenin complexes. The goal of the present study was to analyze whether and how TG2 interacts with and regulates β-catenin signaling in ovarian cancer (OC) cells. We observed a significant correlation between TG2 and β-catenin expression levels in OC cells and tumors. TG2 augmented Wnt/β-catenin signaling, as evidenced by enhanced β-catenin transcriptional activity, inducing transcription of target genes cyclin D1 and c-Myc. By promoting integrin-mediated cell adhesion to FN, TG2 physically associates with and recruits c-Src, which in turn phosphorylates β-catenin at Tyr654, releasing it from E-cadherin and rendering it available for transcriptional regulation. By interacting with FN and enhancing β-catenin signaling, complexed TG2 stimulates OC cell proliferation. In summary, our data demonstrate that TG2 regulates β-catenin expression and function in OC cells and define the c-Src-dependent mechanism through which this occurs.—Condello, S., Cao, L., Matei, D. Tissue transglutaminase regulates β-catenin signaling through a c-Src-dependent mechanism.

Keywords: EMT, Wnt signaling, β-integrin, fibronectin

Tissue transglutaminase 2 (TG2) is a secreted protein with enzymatic and nonenzymatic functions. As an enzyme, it regulates Ca2+-dependent protein post-translational modifications and cross-linking by transferring acyl groups between glutamine and lysine residues (1). Its nonenzymatic functions include binding to fibronectin (FN; ref. 2), which regulates cell-matrix interactions, and GTPase activity involved in transduction of α-adrenergic responses (3, 4). The functions of TG2 are modulated within and outside of the cell. High extracellular Ca2+ enhances enzymatic function, whereas high intracellular GTP inhibits transglutaminase activity (5). TG2 is overexpressed in pancreatic, ovarian, breast, and brain malignancies (6–8). Although the role of TG2 in cancer is not fully understood and may vary depending on cellular context, we and others have reported that it is a tumorigenic protein involved in cellular invasion, metastasis, and chemoresistance (6–11). These functions have been attributed to TG2-induced activation of oncogenic signaling, governed in part by the transcription factors nuclear factor-κB (10, 12) and cAMP response element-binding protein (13) and by Akt serine/threonine kinase (14).

β-Catenin plays a critical role in Wnt signaling, which regulates development, cell proliferation, and differentiation (15). Wnt signaling triggered by binding of Wnt ligands to Frizzled proteins or lipoprotein receptor-related protein 5/6 (LRP5/6) induces glycogen synthase kinase 3β (GSK-3β) phosphorylation and nuclear translocation of β-catenin (16). In normal cells, β-catenin levels and function are tightly regulated; however, these are deranged in cancer cells. Cytoplasmic β-catenin binds adenomatous polyposis coli (APC) and axin, which protect it from phosphorylation by GSK-3β and proteasomal degradation, and regulate its localization. Nuclear β-catenin interacts with T-cell factor (TCF) and lymphoid enhancer-binding factor 1 (LEF1) and is a transcription factor. The target genes of β-catenin (cyclin D1, c-Myc, and snail) regulate cell proliferation and differentiation.

In cancer cells, TG2 regulates the epithelial to mesenchymal transition (EMT; refs. 11, 17), a process that promotes cell invasiveness and metastasis. A proximal event in the EMT is loss of E-cadherins that stabilize cell-cell contacts, leading to mesenchymal behavior (18). Because β-catenin binds the cytoplasmic domain of cadherins, linking them through α-catenin to the actin cytoskeleton, disruption of adherens junctions destabilizes cadherin-catenin complexes. This releases β-catenin and renders it transcriptionally active (19, 20). However, the mechanism regulating β-catenin release remains unknown. Given that TG2 causes E-cadherin down-regulation in ovarian cancer (OC) cells (17), we hypothesized that it may be implicated in the regulation of β-catenin cellular trafficking. The goal of this study was to determine the mechanism by which TG2 interacts with and regulates β-catenin signaling in OC cells.

Wnt and β-catenin signaling have been characterized in breast and colon carcinogenesis, but their roles in OC remain less understood. A recent report demonstrated that conditional inactivation of APC, which enhances β-catenin signaling, in conjunction with Akt activation in normal surface ovarian epithelium induced endometrioid carcinomas (21). Missense mutations in the N-terminal regulatory domain of β-catenin, rendering the protein resistant to degradation, along with mutations affecting other elements in the pathway (e.g., APC, axin 1, and axin 2) have been described in endometrioid ovarian tumors (22), suggesting a role of the pathway in the initiation of this OC subtype. Other reports link Wnt-β-catenin signaling to recurrent chemoresistant OC (23, 24) and Wnt-7A overexpression correlates with poor clinical outcome of serous OC (25). Active β-catenin/TCF signaling has been identified in progenitor ovarian surface epithelial cells and in OC-initiating (stem) cells (23, 26), supporting a role for this pathway in ovarian tumor initiation and persistence.

Here we demonstrate that TG2 expression correlates with expression and activity of β-catenin and that Wnt signaling is enhanced in OC cells expressing TG2. We show that by promoting cell adhesion to FN, TG2 associates with and recruits c-Src, which phosphorylates β-catenin at Tyr654, releasing it from E-cadherin and rendering it transcriptionally active. TG2-induced activation of β-catenin stimulates cell proliferation, particularly in cancer cells anchored to the extracellular matrix by TG2.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Chemicals and reagents

Unless stated otherwise, chemicals and reagents were from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). Wnt-3a, vitronectin (VN), and hyaluronan were from R&D Systems (Minneapolis, MN, USA). Monoclonal and polyclonal TG2 antibodies were from Neomarkers (Fremont, CA, USA). Antibodies for phospho-Src (Tyr416), phospho-GSK-3α/β (Ser21/9), c-Src, and E-cadherin were from Cell Signaling Technology, Inc. (Beverly, MA, USA). β-Catenin was from ECM Biosciences (Versailles, KY, USA). Phospho-β-catenin (Tyr654) was from Abcam (Cambridge, MA, USA). β1-Integrin was from EMD Millipore (Billerica, MA, USA). Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) was from Biodesign International (Saco, ME, USA). Secondary horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated antibodies were from Amersham Biosciences (San Francisco, CA, USA) and Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc. (Santa Cruz, CA, USA). The blocking antibody against α5β1-integrin (IIA1) was from BD Biosciences (San Jose, CA, USA). The antibody against the FN-binding domain of TG2 (4G3) was from EMD Millipore.

Cell culture

SKOV3, IGROV-1, and OV90 cells were from the American Type Culture Collection (Rockville, MD, USA). SKOV3 and OV90 cells were cultured in 1:1 MCDB 105 and M199 (Cellgro; Mediatech, Inc., Manassas, VA, USA) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Cellgro) and 100 U/ml penicillin and 100 μg/ml streptomycin. IGROV-1 cells were grown in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium, 10% FBS, 1 mM sodium pyruvate, and antibiotics. Cells were grown at 37°C under 5% CO2.

Transfection

Stable knockdown of TG2 was achieved by transfection of an antisense construct [antisense tissue transglutaminase (AS-TG2)] in SKOV3 cells, as described previously (7), or by transducing lentiviral particles containing short hairpin RNA (shRNA) targeting TG2 (Sigma-Aldrich) into IGROV-1 cells (11). TG2 and fibronectin-binding domain of transglutaminase (δFN) overexpression in OV90 cells was effected by the retroviral system pQCXIP, described previously, followed by puromycin selection (13). The δFN construct was from Alexey M. Belkin (University of Maryland, Baltimore, MD, USA; ref. 27), and the AS-TG2 construct was from Janusz Tucholski (University of Alabama, Birmingham, AL, USA; ref. 28). Transient transfection of short interfering RNA (siRNA) using DreamFect (Oz Biosciences, Marseille, France) targeted β-catenin (Dharmacon, Lafayette, CO, USA). Scrambled siRNA (Dharmacon) was used as a control.

Western blot analysis

Cells were lysed in buffer containing leupeptin (1 μg/ml), aprotinin (1 μg/ml), phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (PMSF; 400 μM), and sodium orthovanadate (Na3VO4; 1 mM). Lysates were sonicated briefly and centrifuged (14,000 rpm for 15 min at 4°C). Nuclear and cytosolic fractions were isolated using NE-PER Nuclear and Cytoplasmic Extraction Reagents (Pierce, Rockford, IL, USA). Equal amounts of protein were separated by SDS-PAGE and electroblotted onto polyvinylidene difluoride membranes. After incubation with primary and HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies, antigen-antibody complexes were visualized using enhanced chemiluminescence (Amersham Biosciences, Piscataway, NJ, USA). Images were captured by a luminescent image analyzer with a charge-coupled device camera (LAS 3000; Fuji Film, Valhalla, NY, USA). Densitometry was performed with Gel-Pro Analyzer 3.1 software (Media Cybernetics, Inc., Rockville, MD, USA).

Coimmunoprecipitation

Cells were lysed on ice in 50 mM Tris-HCl buffer (pH 7.6), 150 mM NaCl, 1% Nonidet P-40, leupeptin (1 μg/ml), aprotinin (1 μg/ml), and PMSF (400 μM). After 15 min, lysates were centrifuged (13,000 rpm, 30 min). Then 500 μg of supernatant protein was incubated overnight at 4°C with 5 μg of anti-c-Src, anti-β-catenin, or IgG and with 50 μg of slurry of Protein G Plus-Agarose beads (4 h at 4°C; Santa Cruz Biotechnology). Protein-antibody-bead complexes were centrifuged, washed, and boiled in 1× SDS protein loading dye and used for Western blotting.

Reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR)

Semiquantitative and real-time PCR quantified β-catenin, cyclin D1, TG2, c-Myc, LRP5/6, and Frizzled receptor 1, 2, and 7 expression. Total RNA was extracted using RNA STAT-60 Reagent (Tel-Test Inc., Friendswood, TX, USA) and reverse-transcribed using an iScript cDNA synthesis kit (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA). Primers and probes used are listed in Tables 1 and 2. The reverse transcriptase product (1 μl) and primers were heated at 94°C for 90 s, followed by 28 rounds of amplification for GAPDH and 32 cycles for β-catenin (30 s denaturing at 94°C, 30 s annealing at 57°C, and 30 s extension at 72°C) followed by a 10-min final extension at 72°C. The RT-PCR product was visualized under UV light after fractionation on a 1.5% agarose gel. For real-time PCR, a FastStart TaqMan Probe Master (Rox; Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN, USA) on an ABI Prism 7900 platform (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA) was used. At the end of the PCR, a melting curve was generated, and the cycle threshold (Ct) was recorded for the reference and control genes. Relative expression of target genes (cyclin D1 and c-Myc) was calculated as ΔCt, by subtracting the Ct of the reference gene from that of the control. Results are presented as means ± sd of replicates. Each experiment was performed in duplicate in 3 independent conditions.

Table 1.

Primers used for semiquantitative PCR

| Gene | 5′ Primer | 3′ Primer |

|---|---|---|

| β-Catenin | GTTCGCCTTCACTATGGACTACC | GGACCCCTGCAGCTACTCTTT |

| FZ1 | CCGCCGCCCGCCAGTTGA | CGGGCGCGTACATGGAGCACAGGA |

| FZ2 | ATCCCGCCGTGCCGCTCTATCTGT | CGGAAGCGCTGCATGTCTACCAA |

| FZ7 | GCCATCCCGCCGTGTCGTTCTCT | AGGGCGCGGTAGGGTAGGCAGTGG |

| LRP5 | GGCCCTTCCCGCACGAGTATGTC | GGGGGCGGGAAGAGATGGAAGTAG |

| LRP6 | AGCCCGGGGTTCCTCTAA | CAGCCAAATGCCACAAATCC |

| GAPDH | GATTCCACCCATGGCAAATTCC | CACGTTGGCAGTGGGGAC |

Table 2.

Primers and Universal Probe Library probes used for quantitative RT-PCR

| Gene | 5′ Primer | 3′ Primer | Probe |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cyclin D1 | TGTGTTCGCAGCAAATGG | GGCATTTTGGAGAGGAAGTG | 68 |

| c-Myc | CACCAGCAGCGACTCTGA | GATCCAGACTCTGACCTTTTGC | 34 |

| TG2 | AGGGTGACAAGAGCGAGATG | TGGTCATCCACGACTCCAC | 86 |

| GAPDH | AGCCACATCGCTCAGACAC | GCCCAATACGACCAAATCC | 60 |

Immunofluorescence (IF)

pcDNA3.1 and AS-TG2 stably transfected SKOV3 cells were plated on FN-coated chamber slides (BD Biosciences) and allowed to adhere. After fixation in 4% paraformaldehyde, cells were permeabilized using 0.2% Triton X-100 in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; 15 min) and blocked for 1 h with 3% goat serum in PBS. Subsequently, cells were incubated for 1 h with β-catenin, c-Src, β1-integrin, or TG2 primary antibodies in blocking buffer at room temperature, followed by 1 h incubation with Cy5-conjugated anti-mouse secondary antibody (1:500; Zymed Laboratories; South San Francisco, CA, USA) or Alexa Fluor 488 anti-rabbit secondary antibody (1:1000; Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR, USA). Isotype-specific IgG was used as a negative control. Nuclei were visualized by 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) staining (Vectashield; Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA, USA). Analysis was done using an LSM 510 META confocal multiphoton microscope system (Carl Zeiss Inc., Thornwood, NY, USA) under UV excitation at 630 nm (for Cy5), 488 nm (for Alexa Fluor 488), and 340 nm (for DAPI).

Immunohistochemistry (IHC)

A tissue microarray from Pantomics (San Francisco, CA, USA) including 22 human epithelial serous or endometrioid ovarian tumors arrayed in duplicate was immunostained for β-catenin and TG2. Immunostaining for TG2 was performed as described previously (7). The antibody for β-catenin (ECM Biosciences) was used at a dilution of 1:50 overnight, followed by the avidin-biotin peroxidase technique with a Dako Detection Kit (Dako, Hamburg, Germany). Intensity was scored on a scale from 0 to 3+, and the percentage of stained cells was quantified. An H score was calculated as the product between intensity and percentage of stained cells, and tumors were classified as positive or negative if the H score was more than or equal to or less than the median score, respectively.

Gene reporter assay

A Dual-Luciferase Assay (Promega) was used to quantify TCF/LEF1 promoter activity. In brief, cells were transiently cotransfected with TCF/LEF1 promoter luciferase and Renilla plasmids at a ratio of 10:1 using DreamFect Gold transfection reagent. The TCF/LEF1 reporter plasmid was a gift from Dr. Harikrishna Nakshatri (Indiana University School of Medicine, Indianapolis, IN, USA). Luminescence was measured using a TD-20/20 luminometer (Turner BioSystems, Sunnyvale, CA, USA) 48 h after transfection. Experiments were performed in triplicate and repeated. To control for transfection efficiency, luminescence was normalized to Renilla activity.

Cell proliferation

pcDNA3.1- and AS-TG2-transfected SKOV3 cells were seeded into 24-well plates (5×104 cells/well) that were uncoated or coated with FN (10 μg/ml) in serum-free medium. Proliferation was quantified by a methylthiazolyldiphenyl-tetrazolium bromide (MTT) assay (29). Optical density of solubilized cells was measured with a plate reader (SpectraMax 190; Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA, USA) at 570 nm. Four replicates were used, and data are means ± se.

Statistical analysis

Student's t tests were used to compare data between groups; χ2 tests and Spearman coefficients of correlation were used to compared IHC staining for TG2 and β-catenin. Values of P < 0.05 were considered significant.

RESULTS

TG2 and β-catenin expression correlate in OC cells

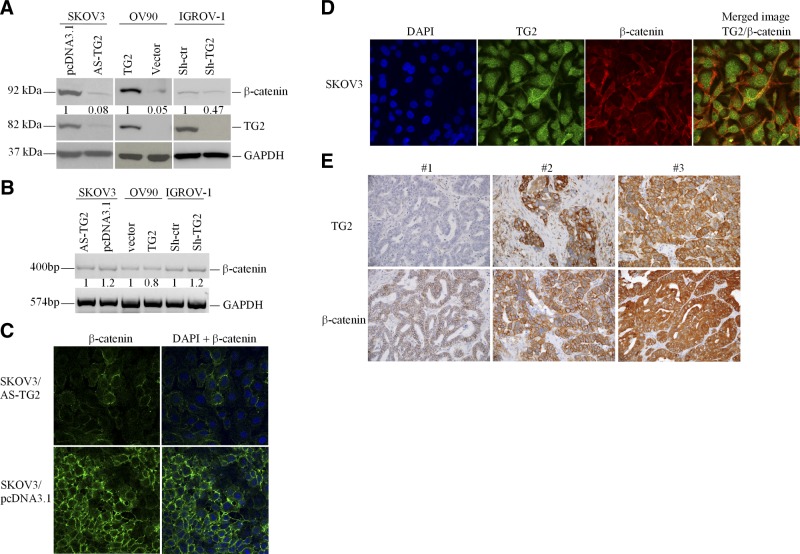

To determine whether β-catenin and TG2 expression levels correlate, we used OC cell lines in which TG2 expression was modulated. SKOV3 cells were stably transfected with vector (pcDNA3.1) or an antisense (AS-TG2) construct; IGROV-1 cells were transduced with an empty lentiviral vector control (Sh-ctr) or an shRNA targeting TG2 (Sh-TG2). β-Catenin expression in AS-TG2-transfected and Sh-TG2-transduced cells were ∼12- and 2-fold lower than SKOV3/pcDNA3.1 and IGROV-1/Sh-ctr control cells, respectively. β-Catenin expression was increased ∼20-fold in OV90 cells transduced with TG2 compared with that in vector (pQCXIP)-transduced cells (Fig. 1A). These Western blots indicate TG2-mediated induction of β-catenin protein levels.

Figure 1.

TG2 and β-catenin expression levels correlate in OC cells and tumors. A) Western blotting for TG2, β-catenin, and GAPDH protein levels in OC cells (SKOV3, OV90, and IGROV-1) stably transduced with AS-TG2, TG2, or siRNA targeting TG2, respectively (see Materials and Methods). B) Semiquantitative RT-PCR quantified β-catenin and GAPDH in SKOV3 (pcDNA3.1 and AS-TG2), OV90 (pQXCIP and TG2), and IGROV-1 cells (shRNA control and targeting TG2). Densitometry quantified β-catenin expression levels relative to those of GAPDH. C) IF staining for β-catenin in pcDNA3.1- and AS-TG2-transfected SKOV3 cells. D) SKOV3 OC cells were stained with polyclonal anti-TG2 antibody (Alexa Fluor 488, green) and anti-β-catenin (Cy5, red; ×600). Protein colocalization is identified by yellow spectra on merged images. Nuclei are visualized by DAPI. E) Representative IHC staining for β-catenin and TG2 in OC (×200).

To address whether TG2 promoted β-catenin expression transcriptionally, RT-PCR was performed. No significant differences in β-catenin mRNA expression levels were noted in the OC cell lines in which TG2 was overexpressed (OV90) or knocked down (IGROV-1 and SKOV3; Fig. 1B), suggesting that the correlation between TG2 and β-catenin expression is not regulated transcriptionally.

IF staining was used to analyze the cellular distribution of β-catenin in relation to TG2. In control SKOV3/pcDNA3.1 cells, β-catenin localized to the cytosol and cell membrane, particularly at cell contact points. There was also evidence of nuclear β-catenin staining, evident especially in isolated cells. In contrast, SKOV3/AS-TG2 cells were characterized by decreased β-catenin IF in all cellular compartments (Fig. 1C). Double IF staining indicated colocalization of β-catenin and TG2 mostly at the cell membrane and in invadopodia (Fig. 1D).

To assess the in vivo relevance of these observations, we correlated TG2 and β-catenin expression in human serous or endometrioid OC. A total of 22 human ovarian tumors on a multitissue array were immunostained for both proteins, and H scores were correlated. Moderate to strong (2+ to 3+) TG2 and β-catenin staining was observed in 86 and 95% of the tumors, respectively, and the Spearman coefficient of correlation was r = 0.54 (P=0.01), pointing to a significant correlation (Supplemental Table S1).

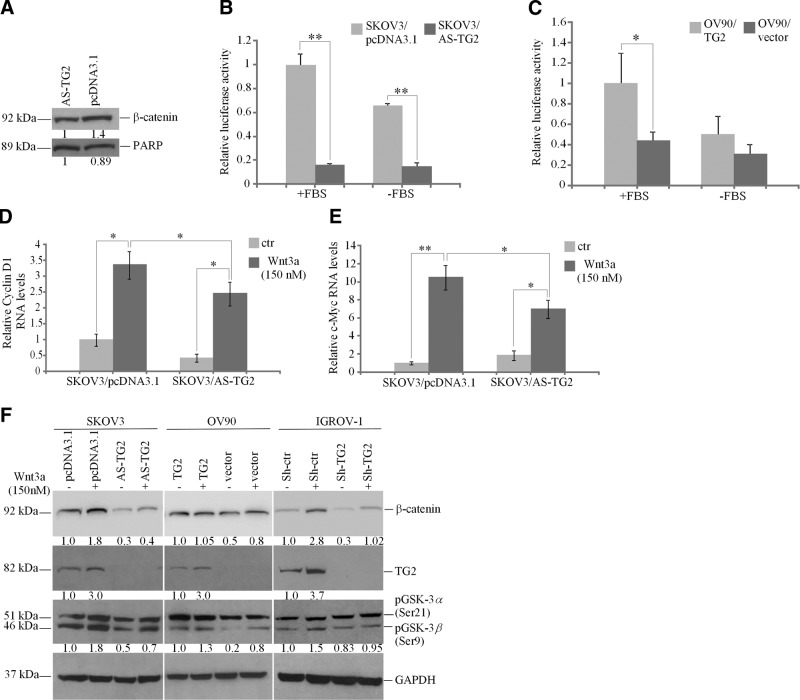

TG2 and β-catenin transcriptional activity correlate

When β-catenin translocates to the nucleus, it binds the transcriptional complex TCF/LEF1, displacing the repressor Groucho, and activating transcription (30). Because β-catenin expression was increased in TG2-expressing OC cell lysates, we evaluated its nuclear function. Western blotting quantified β-catenin expression in nuclear extracts, demonstrating a ∼50% increase in SKOV3/pcDNA3.1 compared with that in SKOV3/AS-TG2 cells (Fig. 2A). To determine whether nuclear localization of free β-catenin associated with increased transcriptional activity, a TCF/LEF1 reporter assay was performed. TG2-expressing cells grown in FBS-supplemented medium exhibited ∼5.5- and 2- to 4-fold increases in TCF/LEF1 promoter activity in SKOV3/pcDNA3.1 and OV90/TG2 cells compared with that in SKOV3/AS-TG2 (Fig. 2B) and OV90/pQCXIP cells, respectively (Fig. 2C). In the absence of FBS, a similar increase in TCF/LEF1 activity was observed in SKOV3/pcDNA3.1 and OV90/TG2 cells compared with that in SKOV3/AS-TG2 (Fig. 2B) and OV90/pQCXIP (Fig. 2C) cells. In addition, TCF/LEF1 promoter activity decreased in SKOV3 (1.4-fold) and OV90 control cells (2-fold) in basal compared with FBS-stimulated conditions (Fig. 2B, C).

Figure 2.

TG2 regulates β-catenin transcription function in OC cells. A) Western blotting for β-catenin and poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP; control) in nuclear extracts from pcDNA3.1- and AS-TG2-transfected SKOV3 cells. B, C) TCF/LEF1 promoter activity measured by a reporter assay using SKOV3 cells stably transfected with pcDNA3.1 and AS-TG2 (B) and OV90 cells transduced with pQXCIP and TG2 (C), grown in complete (+FBS) or serum-free medium (−FBS). Values for luminescence were normalized to Renilla activity. Data are means ± sd of duplicate measurements. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01. D, E) Quantitative RT-PCR for cyclin D1 (D) and c-Myc (E) in SKOV3/pcDNA3.1 and AS-TG2 cells treated with Wnt-3a (150 nM) for 4 h. Data are means ± sd of duplicate measurements. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01. ctr, control. F) Western blotting for β-catenin, TG2, phospho-GSK-3α/β, and GAPDH in SKOV3, OV90, and IGROV-1 cells expressing TG2 or not and treated with Wnt-3a (150 nM) for 4 h.

We next examined whether the effects of Wnt on β-catenin and its target genes, cyclin D1 and c-Myc, are altered by TG2. OC cell lines and tumors express Wnt ligands and receptors (Supplemental Fig. S1). Cyclin D1 mRNA expression was increased 3-fold by Wnt-3a in TG2-expressing SKOV3/pcDNA3.1 cells (P=0.01), whereas its basal expression and Wnt-3a induction were reduced in SKOV3/AS-TG2 cells (Fig. 2D). Similarly, c-Myc mRNA expression level was induced >10-fold by Wnt-3a in TG2-expressing SKOV3/pcDNA3.1 cells (P=0.008) but substantially less in SKOV3/AS-TG2 cells (Fig. 2E). These data suggest that TG2 promotes nuclear translocation of β-catenin with subsequent TCF/LEF1-mediated gene activation.

Wnt-3a also increased β-catenin expression in TG2-expressing cells (SKOV3/pcDNA3.1, OV90/TG2, and IGROV-1/Sh-ctr) compared with that in low-TG2-expressing cells (SKOV3/AS-TG2, OV90/pQCXIP, and IGROV-1/Sh-TG2; Fig. 2F), suggesting that the protein is stabilized by TG2. Notably, TG2 was induced by Wnt-3a at the protein (Fig. 2F) and mRNA levels (Supplemental Fig. S2) in SKOV3 and IGROV-1 control cells, suggesting that it is a Wnt-3a target gene.

To define the mechanism by which TG2 stabilizes β-catenin, phosphorylation of GSK-3β was assessed. Phosphorylation inactivates GSK-3β, rendering it unable to phosphorylate β-catenin for degradation. A modest increase in Ser-9 phosphorylation of GSK-3β was noted in TG2-expressing cells (SKOV3/pcDNA3.1, OV90/TG2, and IGROV-1/Sh-ctr) compared with that in SKOV3/AS-TG2, OV90/pQCXIP, and IGROV-1/Sh-TG2 cells, respectively (Fig. 2F). This result suggests that one pathway through which TG2 stabilizes β-catenin expression is by altering GSK-3β phosphorylation. However, TG2 expression did not influence GSK-3β phosphorylation levels induced by Wnt-3a. The relatively modest difference in basal GSK-3β phosphorylation and the similar response to Wnt-3a of cells expressing different TG2 expression levels suggest that mechanisms other than GSK-3β are involved in β-catenin stabilization by TG2.

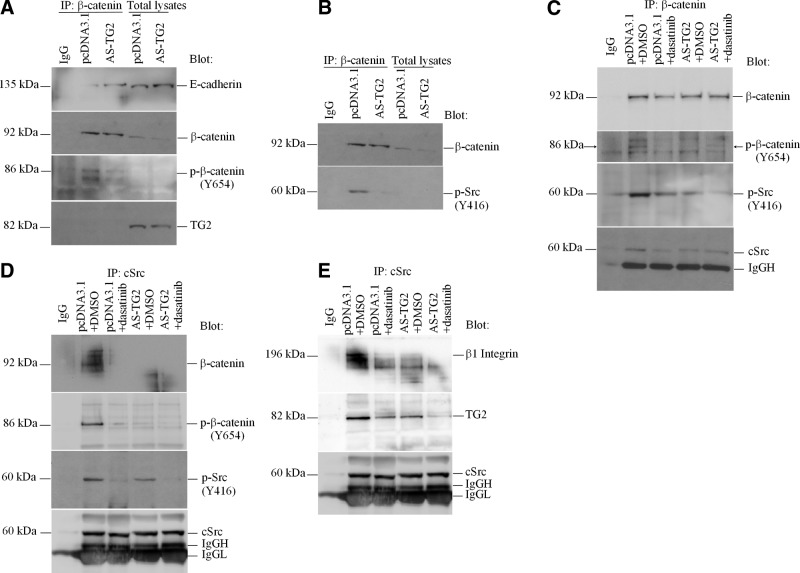

TG2 increases β-catenin phosphorylation by recruiting and activating c-Src

We tested for an interaction between TG2 and β-catenin by immunoprecipitating β-catenin in cell lysates from SKOV3/AS-TG2 and control cells. Although TG2 expression levels correlated with β-catenin expression in lysates from these cells, the β-catenin pulldown did not contain TG2, refuting the hypothesis that the 2 proteins interact (Fig. 3A). E-cadherin, however, was detected in the same complex with β-catenin, with decreased levels in SKOV3/pcDNA3.1 cells compared with that in SKOV3/AS-TG2 cells. Having previously shown that TG2 represses E-cadherin transcription (17) and knowing that phosphorylation of several tyrosine residues, particularly Tyr654 in the last armadillo repeat motif of β-catenin, affects its affinity for E-cadherin (31), we investigated whether TG2 expression alters β-catenin phosphorylation. Western blotting with anti-β-catenin phospho-Tyr654 demonstrated decreased β-catenin phosphorylation in SKOV3/AS-TG2 cells compared with that in controls. This was detectable in complexes immunoprecipitated with β-catenin but not in total cell lysates (Fig. 3A). Because c-Src is the major kinase regulating β-catenin Tyr654 phosphorylation and its interaction with E-cadherin (31), we tested whether active Src is complexed with β-catenin and whether TG2 expression alters its activity. We detected phospho-Tyr416 c-Src in β-catenin complexes immunoprecipitated from SKOV3/pcDNA3.1 TG2-expressing cells but not from SKOV3/AS-TG2 cells (Fig. 3B), suggesting that the interaction between active (phosphorylated) c-Src and β-catenin depends on TG2 expression.

Figure 3.

TG2, β-catenin, and activated c-Src form a complex in OC cells. A, B) Equal amounts of lysates of SKOV3/pcDNA3.1 and SKOV3/AS-TG2 cells were immunoprecipitated (IP) with β-catenin antibody. Western blotting was performed using E-cadherin, TG2, and phospho (p)-β-catenin (Y654) antibodies (A) or phospho-Src (Y416) antibodies (B). C) Total β-catenin was immunoprecipitated from lysates of pcDNA3.1- and AS-TG2-transfected SKOV3 cells treated with dasatinib (100 nM) or dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO; control) for 24 h. Western blotting was performed using phospho-β-catenin (Y654), phospho-Src (Y416), and total c-Src antibodies. D, E) Conversely, c-Src was immunoprecipitated from lysates of pcDNA3.1- and AS-TG2-transfected SKOV3 cells treated with dasatinib (100 nM) or DMSO (control) for 24 h. Western blotting was performed using phospho-β-catenin (Y654), phospho-Src (Y416), and total β-catenin (D) or TG2 and β1-integrin antibodies (E). Nonspecific IgG was used as control.

To demonstrate that active c-Src phosphorylates β-catenin at Tyr654 in the presence of TG2, pcDNA3.1- and AS-TG2-transfected SKOV3 cells were treated for 24 h with 100 nM dasatinib, a c-Src kinase inhibitor. Equal amounts of protein lysates from cells treated with dasatinib or vehicle (dimethyl sulfoxide) were immunoprecipitated with anti-β-catenin. Phospho-β-catenin Tyr654 was increased in SKOV3/pcDNA3.1 cells compared with that in SKOV3/AS-TG2 cells. Tyr654 β-catenin phosphorylation was blocked by dasatinib in both cell lines (Fig. 3C). Notably, decreased total β-catenin was observed in control and SKOV3/AS-TG2 cells treated with dasatinib, suggesting that c-Src activation is necessary for β-catenin stabilization. In TG2-expressing and control treated SKOV3/pcDNA3.1 cells, total and active c-Src were detectable in β-catenin complexes. Total and active c-Src levels were decreased by dasatinib in immunoprecipitates from SKOV3/pcDNA3.1 cells and in control or dasatinib-treated SKOV3/AS-TG2 pulldown lysates (Fig. 3C). Similar results were obtained when lysates from SKOV3/AS-TG2 and control cells treated with dasatinib or vehicle were coimmunoprecipitated with anti-c-Src. Total and Tyr654 β-catenin immunoprecipitated with c-Src was increased in vehicle-treated SKOV3/pcDNA3.1 cells compared with that in SKOV3/AS-TG2 cells. This result corresponded to elevated c-Src phosphorylation at Tyr416 in control cells. Dasatinib inhibited c-Src phosphorylation and reduced c-Src and β-catenin immunoprecipitation even in the presence of TG2 (Fig. 3D). Taken together, these data suggest that TG2 facilitates formation of a β-catenin-c-Src complex that promotes Tyr654 phosphorylation of β-catenin.

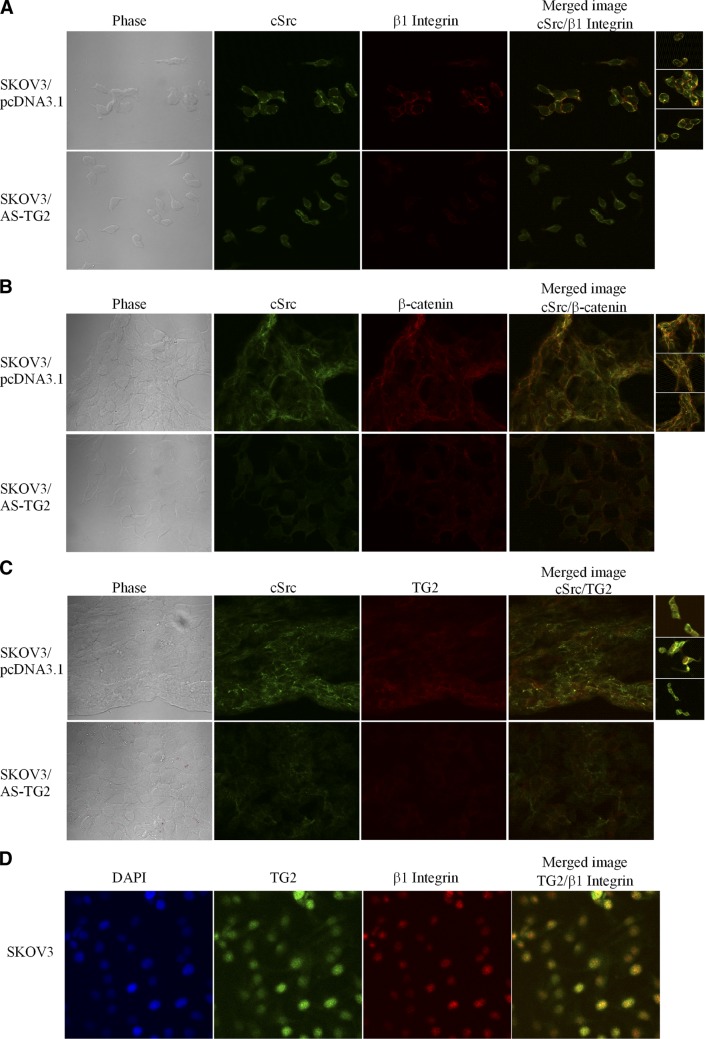

The association of TG2 and c-Src was also demonstrated by immunoprecipitation from SKOV3/pcDNA3.1 and SKOV3/AS-TG2 cells with anti-c-Src and blotting for TG2 (Fig. 3E). Dasatinib disrupted the TG2-c-Src complex in both cell types, indicating that TG2 was necessary for the activation of c-Src (Fig. 3E). Knowing that TG2 facilitates interaction of β-integrins and the FN matrix and that c-Src binds to the β-integrin cytoplasmic tail through a process that activates the kinase, we investigated whether c-Src activation in the complex with TG2 was a consequence of interaction with β1-integrins. To address this question, we tested whether the c-Src coimmunoprecipitates contain β1-integrin. Figure 3E illustrates that β1-integrin forms a complex with TG2 and c-Src in SKOV3/pcDNA3.1 cells and that its abundance in this complex was increased compared with that in SKOV3/AS-TG2 cells. Dasatinib inhibited β-integrin-TG2-c-Src complex formation (Fig. 3E). IF and confocal microscopy illustrate colocalization of β1-integrin and c-Src at the plasma membrane in TG2-expressing cells (Fig. 4A and Supplemental Fig. S3). c-Src also colocalizes with β-catenin (Fig. 4B) and TG2 (Fig. 4C) at the membrane level. In addition, TG2 directly modulates the assembly of c-Src-β1-integrin complexes by colocalizing with β-1integrins, as shown in SKOV3 cells (Fig. 4D). Taken together, these data demonstrate that the complex of TG2 and β1-integrin recruits c-Src, which is activated within the complex and subsequently phosphorylates β-catenin at Tyr654. Phosphorylation at this residue frees β-catenin from its binding to E-cadherin (31), allowing it to enter the cytoplasmic pool.

Figure 4.

TG2, β-catenin, and β-integrin form a complex with c-Src in OC cells. A−C) Immunofluorescence staining for β1-integrin (Cy5, red) and c-Src (Alexa Fluor 488, green; A), β-catenin (Cy5, red) and c-Src (B), and TG2 (Cy5, red) and c-Src (C) in SKOV3 cells transfected with AS-TG2 and pcDNA3.1. D) IF with polyclonal anti-TG2 antibody (Alexa Fluor 488, green) and anti-β1-integrin (Cy5, red; ×600). Protein colocalization is identified by emergence of yellow spectra on merged images.

TG2 interaction with integrins and FN activates c-Src

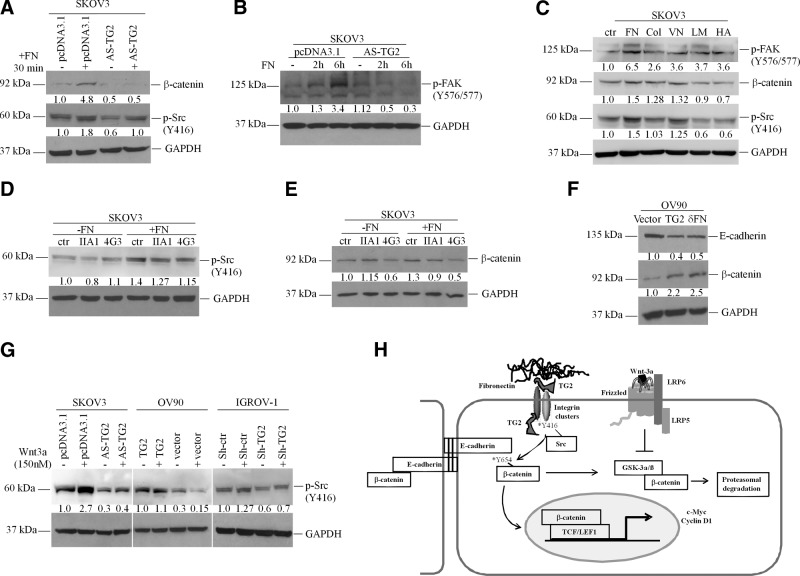

To understand the consequences of TG2-induced c-Src recruitment, activation of the kinase was measured in the context of TG2-mediated cell interaction with the matrix. First, c-Src Tyr416 phosphorylation was measured in SKOV3/pcDNA3.1 and SKOV3/AS-TG2 cells plated on FN-coated or uncoated plates. Increased c-Src phosphorylation correlating with increased β-catenin expression was observed in SKOV3/pcDNA3.1 vs. SKOV3/AS-TG2 cells and in cells plated on FN-coated vs. uncoated plastic plates (Fig. 5A), suggesting that c-Src is activated by TG2-mediated cell adhesion to FN. This corresponded to increased focal adhesion kinase (FAK) phosphorylation in control vs. SKOV3/AS-TG2 cells plated on FN (Fig. 5B), suggesting TG2-dependent increased integrin engagement on cell adhesion to the matrix. Notably, increased FAK and c-Src activation and, correspondingly, increased β-catenin expression levels were observed in SKOV3 cells plated on FN compared with those for other matrix components (VN, collagen-1, laminin, or hyaluronan; Fig. 5C). FAK and c-Src were activated modestly by cell adhesion to VN but to a lesser degree than that observed with FN.

Figure 5.

TG2 binding to FN activates c-Src and stabilizes β-catenin. A) Western blotting for β-catenin and phospho (p)-Src (Y416) in pcDNA3.1- and AS-TG2-transfected SKOV3 cells plated for 30 min onto uncoated or FN-coated (10 μg/ml) plates. B) Western blotting for p-FAK (Y576/577) in SKOV3/pcDNA3.1 and SKOV3/AS-TG2 cells plated on FN for 2 and 6 h. C) Western blotting for p-Src (Y416), β-catenin, and p-FAK (Y576/577) in SKOV3 cells plated on uncoated plastic (ctr, control), FN, collagen-1 (Col; 10 μg/ml), VN (5 μg/ml), laminin (LM; 5 μg/ml), and hyaluronan (HA; 200 μg/ml) for 30 min. D, E) Western blotting for p-Src (Y416; D) or β-catenin (E) in SKOV3 cells plated for 24 h onto uncoated or FN-coated (10 μg/ml) plates and treated with control neutralizing antibody against TG2-FN binding domain (4G3; 10 μg/ml) or α5β1-integrins (IIA1; 5 μg/ml). F) Western blotting for β-catenin and E-cadherin of OV90 cells stably transduced with TG2, pQCXIP, and δFN. G) Western blotting for p-Src (Y416) of OC cells expressing TG2 or not (SKOV3+/−AS-TG2; OV90+/−TG2, and IGROV-1+/−Sh-TG2) and treated with Wnt-3a (150 nM) or control cells for 4 h. H) Proposed mechanism by which TG2 regulates the transfer of β-catenin from its complex with E-cadherin at intercellular junctions to the cytoplasmic and nuclear pools.

To further investigate whether the interaction between TG2, FN, and β1-integrins recruits c-Src and subsequently activates β-catenin, SKOV3 cells were plated on FN-coated plates in the presence of function-inhibiting antibodies against α5β1-integrin dimer (IIA1) or against the FN-binding domain of TG2 (4G3). The increase in c-Src phosphorylation caused by cell adhesion to FN was inhibited by IIA1 (5 μg/ml) and 4G3 (10 μg/ml), suggesting that β1-integrin and TG2 play a role in the activation of this kinase on cell adhesion (Fig. 5D). Furthermore, β-catenin expression was also increased when SKOV3 cells were plated on FN-coated vs. uncoated plastic plates and was decreased by 4G3 but not by IIA1 (Fig. 5E). These observations suggest that the FN-binding function of TG2 is essential for β-catenin stabilization. Further support for this conclusion comes from observations made with the TG2-null OV90 cell line stably transduced with full-length TG2 or with the FN-binding domain of TG2 (δFN). Increased β-catenin expression was observed in OV90/TG2 and in OV90/δFN cells compared with that in vector-transduced cells (Fig. 5F), suggesting that expression of the FN-binding domain of TG is sufficient to stabilize β-catenin in OC cells. Taken together, these data narrow the regulatory effects of TG2 on β-catenin to its FN-binding function.

As a follow-up to the previous observations correlating activation of c-Src, TG2 expression, and β-catenin expression and function, we measured phosphorylation of c-Src in response to Wnt-3a. We observed increased basal and Wnt-3a-induced phospho-Tyr416 c-Src in cancer cells expressing TG2 compared with that in isogenic cell lines without TG2 (Fig. 5G). These data show that in the presence of TG2, c-Src is activated in response to Wnt ligands. The model we propose suggests that by modulating interactions with the matrix converging on c-Src, TG2 regulates the shuffling of β-catenin from its complex with E-cadherin at the intercellular junctions to the cytoplasmic and nuclear pool (Fig. 5H).

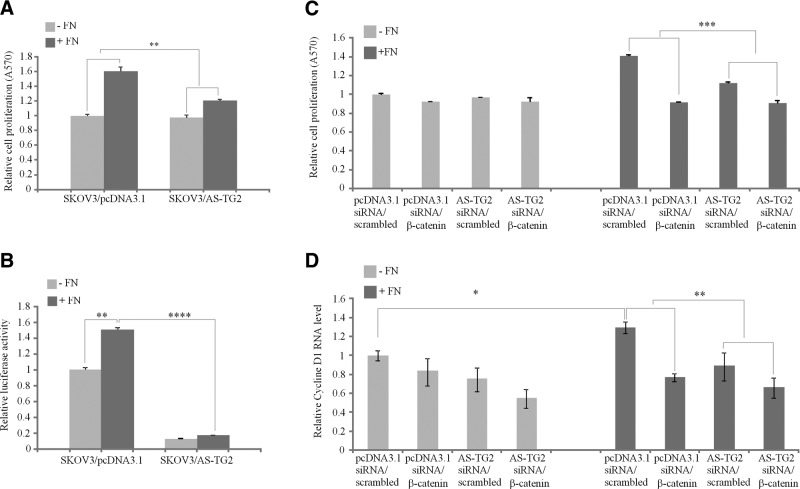

TG2-FN interaction stimulates OC cell proliferation through β-catenin activation

To define the functional consequences of c-Src-β-integrin-FN complex formation mediated by TG2, we assayed OC cell proliferation on an FN matrix. Increased adhesion of TG2-expressing cells to FN causes integrin clustering, which activates the signaling pathways that stimulate cell survival and proliferation. We evaluated whether TG2-mediated adhesion of OC cells to FN increases proliferation through β-catenin signaling. To test this, SKOV3/pcDNA3.1 and SKOV3/AS-TG2 cells were plated on uncoated or FN-coated plastic surfaces in serum-free conditions, and proliferation and β-catenin transcriptional activity were measured. Increased cell proliferation, as measured by MTT assay, was noted in SKOV3/pcDNA3.1 cells plated on FN-coated plates compared with those plated on uncoated plastic plates (Fig. 6A and Supplemental Fig. S4). This increase was significantly higher than the change in proliferation of SKOV3/AS-TG2 cells plated on FN-coated vs. uncoated plastic, suggesting that TG2 promotes cell proliferation on the FN matrix. To evaluate whether β-catenin signaling is implicated in FN-induced cell proliferation, its transactivation was measured using the TCF/LEF1 reporter. TCF/LEF1 transcriptional activity was increased by 50% in TG2-expressing cells plated on FN-coated vs. uncoated plastic but was not measurably increased by FN in SKOV3/AS-TG2 cells (Fig. 6B). Furthermore, the TCF/LEF1 reporter activity was ∼10-fold lower in SKOV3/AS-TG2 cells than in control cells, suggesting that TG2 regulates FN-induced β-catenin transcriptional activity.

Figure 6.

TG2 increases OC cell proliferation in the presence of FN through a β-catenin-dependent mechanism. A) MTT assay measuring proliferation of pcDNA3.1 and AS-TG2-transfected SKOV3 cells grown on uncoated or FN-coated (10 μg/ml) plates for 48 h. Proliferation is expressed as fold increase compared with that for control cells. B) TCF/LEF promoter activity measured by a reporter assay using SKOV3/pcDNA3.1 and SKOV3/AS-TG2 cells plated onto uncoated or FN-coated plates for 6 h. Luciferase activity normalized to Renilla is expressed as fold increase compared with that of control cells. C) MTT assay measuring proliferation of SKOV3/pcDNA3.1 and SKOV3/AS-TG2 cells transfected with scrambled or β-catenin-targeting siRNA and grown on uncoated or FN-coated (10 μg/ml) plates for 48 h. Proliferation is expressed as fold increase compared with that for control cells. D) Quantitative RT-PCR measuring cyclin D1 mRNA expression levels in SKOV3/pcDNA3.1 and SKOV3/AS-TG2 cells transfected with scrambled or β-catenin-targeting siRNA and plated onto uncoated or FN-coated plates for 48 h. Data are means ± sd of duplicate measurements. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001; ****P < 0.0001.

To further demonstrate that FN-stimulated OC cell proliferation is regulated by β-catenin, we used RNA interference-based gene silencing. Efficient β-catenin knockdown was achieved in control and SKOV3/AS-TG2 cells via transient transfection (Supplemental Fig. S5A). Phase-contrast microscopy and an MTT assay demonstrated decreased cell proliferation of FN-plated SKOV3/pcDNA3.1 cells transfected with β-catenin siRNA compared with that in control siRNA (Fig. 6B, right, and Supplemental Fig. S5B). β-Catenin knockdown reduced the proliferation of pcDNA3.1 cells to values similar to those of cells grown in the absence of FN. The effects of β-catenin knockdown on proliferation were not evident when cells were plated on uncoated plastic (Fig. 6C, left) and were more significant in TG2-expressing cells plated on FN-coated plastic than in SKOV3/AS-TG2 cells (Fig. 6C, right). Further support for the effect of TG2-FN interaction on β-catenin activation and proliferation was obtained by measuring mRNA levels for cyclin D1. Quantitative RT-PCR demonstrated that cyclin D1 mRNA basal levels were higher in control than in SKOV3/AS-TG2 cells plated on FN-coated but not on uncoated plates (P=0.04 and 0.1, respectively; Fig. 6D). In TG2-expressing cells, cyclin D1 mRNA levels were higher when cells were plated on FN-coated than on uncoated plastic (P=0.03), but this effect was not observed in SKOV3/AS-TG2 cells (P=0.35). β-Catenin targeting by siRNA did not measurably alter cyclin D1 mRNA levels in SKOV3/pcDNA3.1 and SKOV3/AS-TG2 cells grown on uncoated plates compared with that by scrambled siRNA (P=0.24 and 0.18, respectively; Fig. 6D). However, β-catenin knockdown significantly reduced cyclin D1 expression in SKOV3/pcDNA3.1 cells plated on FN-coated plates (P=0.009) compared with that in SKOV3/AS-TG2 cells (P=0.16), supporting the correlation between TG2-FN interaction and increased β-catenin transcriptional activity regulating cancer cell proliferation.

DISCUSSION

TG2 is overexpressed in >80% of ovarian tumors, as well as in pancreatic, breast, and other cancers (6, 13, 14, 32, 33) and its expression has been linked to cancer metastasis (17, 33). β-Catenin is a transcriptional regulator with oncogenic activity attributed to activating mutations, interaction with mutated catenin-interacting proteins (axin and APC; 34, 35), or canonical activation of Wnt signaling (30, 36). To our knowledge, a functional link between TG2 and β-catenin has never been demonstrated. Here we show for the first time that TG2 regulates the expression and function of β-catenin and bridges β-integrin to β-catenin signaling. An important effector of the crosstalk mediated by TG2 is c-Src, which associates with TG2, β-integrins, and β-catenin and phosphorylates β-catenin at Tyr654, enabling it to become transcriptionally active. These effects amplify Wnt-regulated signals in cancer cells anchored by TG2 in a FN-rich matrix.

Our findings have important implications. First, we show that TG2 modulates the crosstalk between 2 pathways, one activated by cell-matrix and the other by cell-cell interactions. We propose that after cell adhesion to the matrix, surface integrins cluster, this process being facilitated by the interaction between TG2 and FN (2). On formation of a TG2-FN-β-integrin complex, c-Src is recruited, activated, and phosphorylates β-catenin, allowing it to detach from the cytoplasmic domain of E-cadherin. This disrupts β-catenin-E-cadherin complexes, which stabilize cell-cell junctions and allows cells to become motile and invasive. At the same time, β-catenin becomes available in the cytosol, translocates to the nucleus, and activates the transcriptional machinery responsive to Wnt ligands. Our data are consistent with a report showing that integrin clustering is associated with increased β-catenin transcriptional activity (37) and the observation that overexpression of constitutively active integrin-linked kinase activates the LEF1-β-catenin complex (38). Here we demonstrate that TG2 is part of the integrin-mediated complex that is necessary for the recruitment of c-Src, which phosphorylates β-catenin (39).

Second, we demonstrate that TG2 amplifies Wnt signaling. Unlike other cancers, in which the β-catenin pathway is constitutively activated (34), in OC its transcriptional function is mostly dependent on canonical Wnt activation, because only endometrioid ovarian tumors harbor activating β-catenin mutations (40). Overexpression of Frizzled receptors and Wnt ligands has been demonstrated in ovarian tumors, and recent reports implicate Wnt signaling in OC progression (41–43), chemoresistance (23, 43), and functions of cancer-initiating cells (24, 26). In a previous gene profiling study, we found differential mRNA expression of Wnt-5A and Frizzled-7 in human ovarian tumors compared with that in normal surface ovarian epithelium (44). Here we show that the Wnt receptors, FZD1, FZD2, and FZD7, and the LRP5/6 coreceptor are expressed in OC cell lines and in serous ovarian tumors (Supplemental Fig. S1), supporting the conclusion that the canonical Wnt pathway is functional. We also show an enhanced response of c-Myc and cyclin D1 to Wnt in TG2-expressing cells. In addition, we demonstrate that transglutaminase is a Wnt/β-catenin target, identifying an amplification loop involving Wnt and TG2 in OC cells. An exploratory bioinformatic analysis of our Affymetrix gene expression database (44) also correlated TG2 and Wnt-5A mRNA expression in OC-derived primary cells (Pearson coefficient 0.48, P=0.02), supporting the interaction of the 2 pathways. Our findings have focused on the role of membrane-bound or cytosolic TG2 in β-catenin signaling. A previous report showed direct binding of extracellular TG2 to the LRP5/6 receptor in osteoblasts, leading to modest activation of the β-catenin pathway (45). Whether direct activation of Wnt receptors by secreted TG2 occurs in cancer cells remains to be explored.

Third, we demonstrate that the association between c-Src, β-integrin, and TG2 is required for c-Src phosphorylation. Activation of c-Src has been demonstrated in TG2-overexpressing breast cancer cells treated with epidermal growth factor (46); however, in that context, the intermediate filament protein keratin-19 was part of the TG2-Src complex. Here we show that c-Src, β1-integrin, and TG2 form a complex activated on cellular interaction with the FN matrix. This interaction may contribute to Wnt-induced activation of c-Src in TG2-expressing cells. c-Src activation depends on the interaction of TG2 with integrins and the matrix, because neutralizing antibodies against the TG2-FN binding domain block it. Notably, active c-Src has been linked to increased β-catenin signaling through a mechanism that relies on enhanced cap-dependent translation and accumulation of transcriptionally active β-catenin (47). These data suggest that through cell-matrix interactions and recruitment of c-Src, TG2 regulates Wnt signaling, interconnecting the integrin and β-catenin pathways.

We and others have shown that TG2 expression is increased in cancer cells with stem cell properties (10, 48). Our present findings lead us to hypothesize that TG2 affects the functions of OC stem cells through β-catenin signaling. Evidence links Wnt/β-catenin signaling to “stemness” in cancer and development (49, 50), and a critical element regulated by β-catenin and required for the maintenance of stem cells is telomerase (51). Ultimately, our results correlating TG2 and β-catenin expression and function point to β-catenin as a pathway through which TG2 exerts tumorigenic functions and to the TG2-FN interaction as its initiating step.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr. Janusz Tucholski (University of Alabama, Birmingham, AL, USA), Dr. Harikrishna Nakshatri (Indiana University School of Medicine, Indianapolis, IN, USA), and Dr. Alexey M. Belkin (University of Maryland, Baltimore, MD, USA) for reagents; Dr. Susan Perkins for assistance with statistical analyses; and Dr. David Donner for helpful comments.

This work was supported by the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs through a merit award and the American Cancer Society through a research scholar grant (to D.M.).

This article includes supplemental data. Please visit http://www.fasebj.org to obtain this information.

- δFN

- fibronectin-binding domain of transglutaminase

- APC

- adenomatous polyposis coli

- AS-TG2

- antisense tissue transglutaminase

- DAPI

- 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole

- EMT

- epithelial to mesenchymal transition

- FAK

- focal adhesion kinase

- FBS

- fetal bovine serum

- FN

- fibronectin

- GAPDH

- glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase

- GSK-3β

- glycogen synthase kinase 3β

- HRP

- horseradish peroxidase

- IF

- immunofluorescence

- IHC

- immunohistochemistry

- LEF1

- lymphoid enhancer-binding factor 1

- LRP5/6

- lipoprotein receptor-related protein 5/6

- MTT

- methylthiazolyldiphenyl-tetrazolium bromide

- OC

- ovarian cancer

- PBS

- phosphate-buffered saline

- PMSF

- phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride

- RT-PCR

- reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction

- shRNA

- short hairpin RNA

- siRNA

- short interfering RNA

- TCF

- T-cell factor

- TG2

- tissue transglutaminase 2

- VN

- vitronectin

REFERENCES

- 1. Pincus J. H., Waelsch H. (1968) The specificity of transglutaminase. II. Structural requirements of the amine substrate. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 126, 44–52 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Akimov S. S., Belkin A. M. (2001) Cell surface tissue transglutaminase is involved in adhesion and migration of monocytic cells on fibronectin. Blood 98, 1567–1576 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Chen S., Lin F., Iismaa S., Lee K. N., Birckbichler P. J., Graham R. M. (1996) α1-Adrenergic receptor signaling via Gh is subtype specific and independent of its transglutaminase activity. J. Biol. Chem. 271, 32385–32391 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Nanda N., Iismaa S. E., Owens W. A., Husain A., Mackay F., Graham R. M. (2001) Targeted inactivation of Gh/tissue transglutaminase II. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 20673–20678 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Fesus L., Piacentini M. (2002) Transglutaminase 2: an enigmatic enzyme with diverse functions. Trends Biochem. Sci. 27, 534–539 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Mann A. P., Verma A., Sethi G., Manavathi B., Wang H., Fok J. Y., Kunnumakkara A. B., Kumar R., Aggarwal B. B., Mehta K. (2006) Overexpression of tissue transglutaminase leads to constitutive activation of nuclear factor-κB in cancer cells: delineation of a novel pathway. Cancer Res. 66, 8788–8795 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Satpathy M., Cao L., Pincheira R., Emerson R., Bigsby R., Nakshatri H., Matei D. (2007) Enhanced peritoneal ovarian tumor dissemination by tissue transglutaminase. Cancer Res. 67, 7194–7202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Verma A., Wang H., Manavathi B., Fok J. Y., Mann A. P., Kumar R., Mehta K. (2006) Increased expression of tissue transglutaminase in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma and its implications in drug resistance and metastasis. Cancer Res. 66, 10525–10533 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Antonyak M. A., Miller A. M., Jansen J. M., Boehm J. E., Balkman C. E., Wakshlag J. J., Page R. L., Cerione R. A. (2004) Augmentation of tissue transglutaminase expression and activation by epidermal growth factor inhibit doxorubicin-induced apoptosis in human breast cancer cells. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 41461–41467 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Cao L., Petrusca D. N., Satpathy M., Nakshatri H., Petrache I., Matei D. (2008) Tissue transglutaminase protects epithelial ovarian cancer cells from cisplatin-induced apoptosis by promoting cell survival signaling. Carcinogenesis 29, 1893–1900 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Cao L., Shao M., Schilder J., Guise T., Mohammad K. S., Matei D. (2012) Tissue transglutaminase links TGF-β, epithelial to mesenchymal transition and a stem cell phenotype in ovarian cancer. Oncogene 31, 2521–2534 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Verma A., Mehta K. (2007) Transglutaminase-mediated activation of nuclear transcription factor-κB in cancer cells: a new therapeutic opportunity. Curr. Cancer Drug Targets 7, 559–565 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Satpathy M., Shao M., Emerson R., Donner D. B., Matei D. (2009) Tissue transglutaminase regulates matrix metalloproteinase-2 in ovarian cancer by modulating cAMP-response element-binding protein activity. J. Biol. Chem. 284, 15390–15399 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Verma A., Guha S., Wang H., Fok J. Y., Koul D., Abbruzzese J., Mehta K. (2008) Tissue transglutaminase regulates focal adhesion kinase/AKT activation by modulating PTEN expression in pancreatic cancer cells. Clin. Cancer Res. 14, 1997–2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Cadigan K. M., Nusse R. (1997) Wnt signaling: a common theme in animal development. Genes Dev. 11, 3286–3305 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Novak A., Dedhar S. (1999) Signaling through beta-catenin and Lef/Tcf. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 56, 523–537 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Shao M., Cao L., Shen C., Satpathy M., Chelladurai B., Bigsby R. M., Nakshatri H., Matei D. (2009) Epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition and ovarian tumor progression induced by tissue transglutaminase. Cancer Res. 69, 9192–9201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Thiery J. P. (2002) Epithelial-mesenchymal transitions in tumour progression. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2, 442–454 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Gottardi C. J., Wong E., Gumbiner B. M. (2001) E-cadherin suppresses cellular transformation by inhibiting β-catenin signaling in an adhesion-independent manner. J. Cell Biol. 153, 1049–1060 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Nelson W. J., Nusse R. (2004) Convergence of Wnt, β-catenin, and cadherin pathways. Science 303, 1483–1487 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Wu R., Hendrix-Lucas N., Kuick R., Zhai Y., Schwartz D. R., Akyol A., Hanash S., Misek D. E., Katabuchi H., Williams B. O., Fearon E. R., Cho K. R. (2007) Mouse model of human ovarian endometrioid adenocarcinoma based on somatic defects in the Wnt/β-catenin and PI3K/Pten signaling pathways. Cancer Cell 11, 321–333 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Wu R., Zhai Y., Fearon E. R., Cho K. R. (2001) Diverse mechanisms of β-catenin deregulation in ovarian endometrioid adenocarcinomas. Cancer Res. 61, 8247–8255 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Chau W. K., Ip C. K., Mak A. S., Lai H. C., Wong A. S. (2012) c-Kit mediates chemoresistance and tumor-initiating capacity of ovarian cancer cells through activation of Wnt/β-catenin-ATP-binding cassette G2 signaling. [E-pub ahead of print] Oncogene doi:10.1038/onc.2012.290 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Steg A. D., Bevis K. S., Katre A. A., Ziebarth A., Dobbin Z. C., Alvarez R. D., Zhang K., Conner M., Landen C. N. (2012) Stem cell pathways contribute to clinical chemoresistance in ovarian cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 18, 869–881 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Zhang X. L., Peng C. J., Peng J., Jiang L. Y., Ning X. M., Zheng J. H. (2010) Prognostic role of Wnt7a expression in ovarian carcinoma patients. Neoplasma 57, 545–551 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Usongo M., Farookhi R. (2012) β-Catenin/Tcf-signaling appears to establish the murine ovarian surface epithelium (OSE) and remains active in selected postnatal OSE cells. BMC Dev. Biol. 12, 17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Hang J., Zemskov E. A., Lorand L., Belkin A. M. (2005) Identification of a novel recognition sequence for fibronectin within the NH2-terminal β-sandwich domain of tissue transglutaminase. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 23675–23683 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Tucholski J., Lesort M., Johnson G. V. (2001) Tissue transglutaminase is essential for neurite outgrowth in human neuroblastoma SH-SY5Y cells. Neuroscience 102, 481–491 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Kasugai S., Hasegawa N., Ogura H. (1990) A simple in vitro cytotoxicity test using the MTT (3-(4,5)-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyl tetrazolium bromide) colorimetric assay: analysis of eugenol toxicity on dental pulp cells (RPC-C2A). Jpn. J. Pharmacol. 52, 95–100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Morin P. J. (1999) β-Catenin signaling and cancer. Bioessays 21, 1021–1030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Roura S., Miravet S., Piedra J., Garcia de Herreros A., Dunach M. (1999) Regulation of E-cadherin/catenin association by tyrosine phosphorylation. J. Biol. Chem. 274, 36734–36740 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Hwang J. Y., Mangala L. S., Fok J. Y., Lin Y. G., Merritt W. M., Spannuth W. A., Nick A. M., Fiterman D. J., Vivas-Mejia P. E., Deavers M. T., Coleman R. L., Lopez-Berestein G., Mehta K., Sood A. K. (2008) Clinical and biological significance of tissue transglutaminase in ovarian carcinoma. Cancer Res. 68, 5849–5858 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Mangala L. S., Fok J. Y., Zorrilla-Calancha I. R., Verma A., Mehta K. (2007) Tissue transglutaminase expression promotes cell attachment, invasion and survival in breast cancer cells. Oncogene 26, 2459–2470 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Morin P. J., Sparks A. B., Korinek V., Barker N., Clevers H., Vogelstein B., Kinzler K. W. (1997) Activation of β-catenin-Tcf signaling in colon cancer by mutations in β-catenin or APC. Science 275, 1787–1790 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Liu W., Dong X., Mai M., Seelan R. S., Taniguchi K., Krishnadath K. K., Halling K. C., Cunningham J. M., Boardman L. A., Qian C., Christensen E., Schmidt S. S., Roche P. C., Smith D. I., Thibodeau S. N. (2000) Mutations in AXIN2 cause colorectal cancer with defective mismatch repair by activating β-catenin/TCF signalling. Nat. Genet. 26, 146–147 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Bafico A., Liu G., Goldin L., Harris V., Aaronson S. A. (2004) An autocrine mechanism for constitutive Wnt pathway activation in human cancer cells. Cancer Cell 6, 497–506 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Burkhalter R. J., Symowicz J., Hudson L. G., Gottardi C. J., Stack M. S. (2011) Integrin regulation of β-catenin signaling in ovarian carcinoma. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 23467–23475 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Novak A., Hsu S. C., Leung-Hagesteijn C., Radeva G., Papkoff J., Montesano R., Roskelley C., Grosschedl R., Dedhar S. (1998) Cell adhesion and the integrin-linked kinase regulate the LEF-1 and β-catenin signaling pathways. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 95, 4374–4379 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Coluccia A. M., Benati D., Dekhil H., De Filippo A., Lan C., Gambacorti-Passerini C. (2006) SKI-606 decreases growth and motility of colorectal cancer cells by preventing pp60(c-Src)-dependent tyrosine phosphorylation of β-catenin and its nuclear signaling. Cancer Res. 66, 2279–2286 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Shedden K. A., Kshirsagar M. P., Schwartz D. R., Wu R., Yu H., Misek D. E., Hanash S., Katabuchi H., Ellenson L. H., Fearon E. R., Cho K. R. (2005) Histologic type, organ of origin, and Wnt pathway status: effect on gene expression in ovarian and uterine carcinomas. Clin. Cancer Res. 11, 2123–2131 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Yoshioka S., King M. L., Ran S., Okuda H., MacLean J. A., 2nd, McAsey M. E., Sugino N., Brard L., Watabe K., Hayashi K. (2012) WNT7A regulates tumor growth and progression in ovarian cancer through the WNT/β-catenin pathway. Mol. Cancer Res. 10, 469–482 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Schmid S., Bieber M., Zhang F., Zhang M., He B., Jablons D., Teng N. N. (2011) Wnt and hedgehog gene pathway expression in serous ovarian cancer. Int. J. Gynecol. Cancer 21, 975–980 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Chen X., Stoeck A., Lee S. J., Shih I. M., Wang M. M., Wang T. L. (2010) Jagged1 expression regulated by Notch3 and Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathways in ovarian cancer. Oncotarget 1, 210–218 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Matei D., Graeber T. G., Baldwin R. L., Karlan B. Y., Rao J., Chang D. D. (2002) Gene expression in epithelial ovarian carcinoma. Oncogene 21, 6289–6298 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Faverman L., Mikhaylova L., Malmquist J., Nurminskaya M. (2008) Extracellular transglutaminase 2 activates β-catenin signaling in calcifying vascular smooth muscle cells. FEBS Lett. 582, 1552–1557 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Li B., Antonyak M. A., Druso J. E., Cheng L., Nikitin A. Y., Cerione R. A. (2010) EGF potentiated oncogenesis requires a tissue transglutaminase-dependent signaling pathway leading to Src activation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 107, 1408–1413 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Karni R., Gus Y., Dor Y., Meyuhas O., Levitzki A. (2005) Active Src elevates the expression of β-catenin by enhancement of cap-dependent translation. Mol. Cell. Biol. 25, 5031–5039 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Kumar A., Gao H., Xu J., Reuben J., Yu D., Mehta K. (2011) Evidence that aberrant expression of tissue transglutaminase promotes stem cell characteristics in mammary epithelial cells. PLoS One 6, e20701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Wang Y., Krivtsov A. V., Sinha A. U., North T. E., Goessling W., Feng Z., Zon L. I., Armstrong S. A. (2010) The Wnt/β-catenin pathway is required for the development of leukemia stem cells in AML. Science 327, 1650–1653 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Silva-Vargas V., Lo Celso C., Giangreco A., Ofstad T., Prowse D. M., Braun K. M., Watt F. M. (2005) β-Catenin and Hedgehog signal strength can specify number and location of hair follicles in adult epidermis without recruitment of bulge stem cells. Dev. Cell 9, 121–131 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Hoffmeyer K., Raggioli A., Rudloff S., Anton R., Hierholzer A., Del Valle I., Hein K., Vogt R., Kemler R. (2012) Wnt/β-catenin signaling regulates telomerase in stem cells and cancer cells. Science 336, 1549–1554 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.