Abstract

Single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNP) in the genes for pituitary adenylate cyclase-activating peptide (PACAP) and the PAC1 receptor have been associated with several psychiatric disorders whose etiology has been associated with stressor exposure and/or dysregulation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis. In rats, exposure to repeated variate stress has been shown to increase PACAP and its cognate PAC1 receptor expression in the bed nucleus of the stria terminalis (BNST), a brain region implicated in anxiety and depression-related behaviors as well as the regulation of HPA axis activity. We have argued that changes in BNST PACAP signaling may mediate the changes in emotional behavior and dysregulation of the HPA axis associated with anxiety and mood disorders. The current set of studies was designed to determine whether BNST PACAP infusion leads to activation of the HPA axis as determined by increases in plasma corticosterone. We observed an increase in plasma corticosterone levels 30 minutes following BNST PACAP38 infusion in male and female rats, which was independent of estradiol (E2) treatment in females, and we found that plasma corticosterone levels were increased at both 30 minutes and 60 minutes, but returned to baseline levels 4 hours following the highest dose. PACAP38 infusion into the lateral ventricles immediately above the BNST did not alter plasma corticosterone level, and the increased plasma corticosterone following BNST PACAP was not blocked by BNST corticotropin releasing hormone (CRH) receptor antagonism. These results support others suggesting that BNST PACAP plays a key role in regulating stress responses.

Keywords: glucocorticoids, cortisol, HPA axis, extended amygdala, anxiety, stress, estrogen, estradiol, corticotropin-releasing hormone, corticotropin-releasing factor

Introduction

We have reported that levels of pituitary adenylate cyclase-activating polypeptide (PACAP) and a single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) within an estrogen response element (ERE) for the PAC1 receptor gene were correlated with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in women, while PAC1 gene methylation correlated with PTSD in both men and women (Ressler et al., 2011). More recent studies linking PTSD (Almli et al., 2013; Uddin et al., 2013; Wang et al., 2013), , major depressive disorder (Hashimoto et al., 2010) and schizophrenia (Hashimoto et al., 2007) with PACAP gene SNP associations have also contributed to a growing interest in understanding a role for PACAP systems in stress-related psychopathologies.

PACAP has been called a “master regulator” of stress responses (for review see Stroth et al., 2011a). PACAP is highly expressed in the several regions that play a key role in stress responding and emotional behavior, including the bed nucleus of the stria terminalis (BNST, (Kozicz et al., 1997; for review see Vaudry et al., 2009)). However, the brain circuits by which central PACAP regulates the physiological and behavioral consequences of stressor exposure are still being determined.

The BNST plays a key role in regulating behavioral responses associated with anxiety and depression in animals and humans (Hammack et al., 2012; Kalin et al., 2005; Somerville et al., 2010; Walker et al., 2009), and tightly regulates the output of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis (Choi et al., 2007; Herman et al., 2005; Radley and Sawchenko, 2011). HPA dysregulation is a characteristic feature of several anxiety and mood disorders, and maladaptive BNST function may underlie both the behavioral features and the disrupted HPA-function associated with these disorders.

The BNST has been subdivided into multiple subnuclei (Dong et al., 2001), and different BNST subregions regulate HPA activity in different ways (for review, see (Herman et al., 2005)). For example, Radley and colleagues (2009) found that ablation of gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) neurons in the anteroventral BNST enhanced the glucocorticoid response to restraint stress; however, lesions to this region have also been shown to attenuate the glucocorticoid response to restraint stress, suggesting an excitatory role that may be dependent on the activation of corticotropin releasing hormone (CRH, (Choi et al., 2007)). Hence, the relationship between the BNST and HPA axis is complex, and BNST activation can inhibit or excite HPA activity depending on the BNST subregion and/or neuronal population targeted. Together, these data suggest that the BNST tightly regulates HPA activity. Moreover, as noted above, the BNST is sexually dimorphic, and the mechanisms through which the BNST modulates anxiety and stress responding has been largely studied in males. Therefore, it is unknown if this area functions in a similar manner for females in response to stress.

We have shown that PACAP and PAC1 receptor expression in the BNST is sensitive to stressor exposure (Hammack et al., 2009; Hammack et al., 2010); exposure to repeated variate stress increased anxiety-related behavior and PACAP and PAC1 receptor transcript levels in the dorsolateral BNST (BNSTld) (Hammack et al., 2009). Moreover, intra-BNST PACAP infusion increased anxiety-like behavior (Hammack et al., 2009), and produced anorexia and weight loss (Kocho-Schellenberg et al., 2014). The current set of studies examined corticosterone levels following BNST PACAP infusion in both male and female rats and how BNST PACAP and CRH, and BNST PACAP and circulating estradiol (E2) may interact to influence corticosterone levels.

Methods

Subjects

Adult male or overiectomized female Sprague-Dawley rats weighing 250–300 grams at the start of experimentation (male rats weighed ~350 – 400 g and female rats ~275 – 325 g on the day of infusion for all experiments) were obtained from Charles River Laboratories (Canada). Rats were allowed to habituate in their home cages at least one week before experimentation. Rats were single-housed and maintained on a 12 hour light/dark cycle (lights on at 07:00 hours) and food and water were available ad libitum. All procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the University of Vermont.

Surgery

Rats were secured by blunted earbars in a stereotaxic apparatus (David Kopf Instruments, Tujunga, CA) under isofluorane vapor (1.5 – 3.5%) anesthesia. Following a midline incision, 4 screws were put into the skull and bilateral guide cannulae were aimed at an angle of 20° just dorsal to the oval BNST (in respect to bregma: AP = −0.1, ML = +3.8, DV = −5.3 from dura) or at an angle of 20° in the dorsal aspect of the lateral ventricles immediately next to the BNST (respect to bregma: AP = −0.3, ML = +3.0, DV = −3.4). Placements for intra-cerebroventricular (ICV) surgeries were verified during surgery by observing the movement of a small amount of sterile isotonic saline in a length of tubing attached to the cannulae. For both BNST and ICV surgeries, stylettes were inserted to maintain cannulae patency, and a skull cap was created with dental acrylic to secure cannulae and stylettes. Immediately following surgery, rats were administered Ringer’s Solution to provide hydration and analgesic care via Meloxicam or Carprofen (Pfizer), as well as additional analgesic care 24 hours following surgery. Post-operative care was performed for seven days following surgery. Handling, consisting of light restraint, was performed for at least 3 days prior to experimentation in order to habituate rats to the infusion procedure.

For experiments involving female rats, BNST cannulae were implanted in the same manner as previously described. Females also received subcutaneous implants of silicone sealed silastic capsules containing 10mm length of 10% estradiol/90% cholesterol, or cholesterol alone (100%). In order to determine the efficacy of the implants, trunk blood was collected at the time of perfusion to be later analyzed for blood estradiol levels via an estradiol enzyme linked immunoassay. Trunk blood was allowed to clot at room temperature for one hour and then subsequently spun at 4°C at 4000rpm for one hour to separate serum. Serum samples were stored at −80°C for later processing.

Corticosterone Enzyme-Linked Immunoassay

Following collection of plasma from tail nick samples, a corticosterone enzyme-linked immunoassay (CORT EIA, Enzo Life Sciences, Farmingdale, NY) was utilized to determine corticosterone levels. Plasma samples were first diluted 1:30 and heated in a 75°C water bath for at least 45 minutes to denature corticosterone binding globulin (Buck et al., 2011). The interassay coefficient of variation was 8.35% and the sensitivity of the assay was 26.99pg/ml.

Estradiol Enzyme-Linked Immunoassay

Following the collection of trunk blood, an estradiol enzyme- linked immunoassay (Cayman Chemical Company, Ann Arbor, MI) was utilized to determine circulating estradiol levels. Samples were run undiluted through the EIA. The sensitivity of the assay was 129pg/ml, and the interassay coefficient of variation was 8.04%.

Histology

Upon completion of each study, rats were anesthetized with Fatal-Plus Solution (Vortech, Dearborn, MI) and perfused transcardially with saline (0.9%) containing 0.1% heparin (Sagent, Schaumburg, IL) followed by 4% paraformaldehyde. Brains were postfixed at 4°C for at least 24 hours in 4% paraformaldehyde. Fixed tissue was cut using a cryostat, and floating sections were collected at 60µm thickness. Mounted sections were then stained with a cresyl violet stain and coverslipped. Cannulae placements were visualized using a 4x Nikon Objective on an Olympus microscope.

Statistics

Statistical analyses were completed using SPSS version 20 (IBM Software, Armonk, NY) and graphical representations were completed using GraphPad version 6 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA). Rats were eliminated from analysis for BNST cannulation experiments if cannulae placement fell outside the histological boundary of the BNST, or fell within the lateral ventricles. Additionally, rats were eliminated if their corticosterone level was more than two standard deviations away from the treatment mean. ANOVA was used to calculate overall group differences and comparisons between groups were completed using Tukey’s post-hoc comparisons or t-tests.

Experimental Procedure

Experiment 1

Male rats were implanted with guide cannulae aimed at the dorsolateral BNST (BNSTld) as described above. Following one week of post-operative recovery, rats were pseudorandomly matched by weight into one of three groups that received different doses of PACAP38: 0µg/0.5µl (0.05% bovine serum albumin (BSA)/vehicle; n = 10), 0.5µg/0.5µl (n = 7) or 1.0µg/0.5µl (n = 6) in a between-subjects design. PACAP38 (American Peptide Co., Sunnyvale, CA) was diluted to the appropriate final concentration into 0.05% BSA (Santa Cruz Biotech., Santa Cruz, CA). Infusions were performed in the colony room under light restraint. For each infusion, the stylette was removed, and an internal cannula that extended 1mm beyond the end of the guide cannula was inserted. Pressure injections were completed using a 10µl Hamilton syringe connected to the internal cannula with PE50 plastic tubing. A volume of 0.5µl was infused (over 1 minute) into the BNST on each side. Following infusion, the internal cannula was kept in place for an additional minute to allow for diffusion of the drug away from the infusion site. The internal cannula was then removed, and an infusion was completed for the opposite side. Following bilateral infusion, the rat was kept in the colony room until blood sampling.

Blood sampling was conducted in a separate room; blood was collected 30 minutes following infusion via tail clip as the animal was restrained in a clear Plexiglas tube. The time from entering the colony room to the conclusion of blood collection was less than 3 minutes in order to avoid the increase in corticosterone release associated with cage removal. The blood sample was immediately put into a refrigerated centrifuge and spun between 2000 – 4000 rpm for 15 – 20 minutes to separate plasma. Plasma was stored at −20°C until corticosterone quantification through a CORT EIA. Rats were weighed for the following 2 days to assess weight loss due to treatment.

Experiment 2

The second experiment was designed to determine the time-course over which intra-BNST PACAP infusion increases plasma corticosterone levels. The time points of 30 minutes (PACAP: n = 9, vehicle: n = 11), 60 minutes (PACAP: n = 9, vehicle: n = 11), 4 hours (PACAP: n = 12, vehicle: n = 14) and 24 hours (PACAP: n = 10, vehicle: n = 10) were chosen in order to determine how long the corticosterone increase was sustained, based off of previous studies that have examined corticosterone release following stressor exposure (Agarwal et al., 2005; Choi et al., 2007). Rats were implanted with guide cannulae aimed at the BNSTld, and postoperative care was completed as described above. Prior to infusion, rats were weighed and pseudorandomly assigned to either receive PACAP38 or vehicle (0.05% BSA) treatment groups, such that all groups would have the same average weight. PACAP38 was diluted to a final concentration of 1.0µg/0.5µl into 0.05% BSA. Infusions were performed in the colony room as described previously, and rats remained in their home cage until blood sampling.

For each rat, blood samples were collected at two out of the four possible time points in a counterbalanced fashion in order to prevent sensitization due to repeated sampling. Plasma from tail nicks was stored at −20°C until corticosterone quantification by EIA was performed, and rat weights were measured over the following two days.

Experiment 3

Because PACAP dysregulation has been associated with PTSD in women, and because PACAP may interact with E2, we also assessed the effects of BNST PACAP on corticosterone in ovariectomized female (with or without E2 replacement). All procedures were conducted as described in experiment 1, except that ovariectomized female rats received silastic capsule implants containing either cholesterol or estradiol immediately following cannulation; similar to males in experiment 1, all females were allowed one week post-operative recovery (E2-vehicle: n = 13, 0.5µg PACAP: n = 6, 1.0µg PACAP: n =4; cholesterol- vehicle: n = 14, 0.5µg PACAP: n = 5, 1.0µg PACAP: n = 7).

Experiment 4

The fourth experiment was designed to determine whether the effects of intra-BNST PACAP infusion on plasma corticosterone could be explained by drug spread into the adjacent lateral ventricles. ICV cannulation surgeries were performed in the manner described above with the cannulae aimed bilaterally at the lateral ventricles immediately above the BNST in male rats (PACAP: n = 8; vehicle: n = 7).

Experiment 5

Several studies have suggested that BNST CRH receptor activation mediates behavioral responses associated with stressor exposure in rodents (see (Walker et al., 2009) for review). Moreover, BNST CRH type 1 receptor antagonism attenuated the anxiogenic effects of BNST calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP) infusion (Sink, Chung, 2013); hence, like CGRP, BNST CRH receptor activation may be downstream of the effects of BNST PACAP in the circuit that leads to increased plasma corticosterone. Consistent with this idea, PACAP-positive fibers can be observed in close proximity to BNST CRH neurons (Kozicz et al., 1998). Hence, experiment 5 was designed to determine whether the increased plasma corticosterone following intra-BNST PACAP infusion could be blocked by the administration of the CRH antagonist D-Phe CRH (12–41) prior to BNST PACAP infusion. BNST cannulation surgeries were performed in the manner described above. Following one week of post-operative care, male rats were removed from their home cages and bilaterally infused with either saline vehicle or 50 ng per side of D-Phe CRH (12–41) (Bachem, Torrance, CA), 0.5 µl per side into the BNST. 15 minutes after this infusion, rats were infused with either vehicle (0.05% BSA) or 1.0µg/0.5µl PACAP38 into the BNST in a counterbalanced manner (D-Phe CRH/BSA: n = 8, D-Phe CRH/PACAP: n = 8, Saline/BSA: n = 9, Saline/PACAP: n = 8). The dose of D-Phe CRH (12–41) was chosen because we have previously shown this dose to be effective in blocking the behavioral consequences of inescapable shock (Hammack 2002). Infusions and blood sampling were conducted in a similar manner as described above, and quantification of plasma corticosterone levels was determined by EIA.

Results

Experiment 1

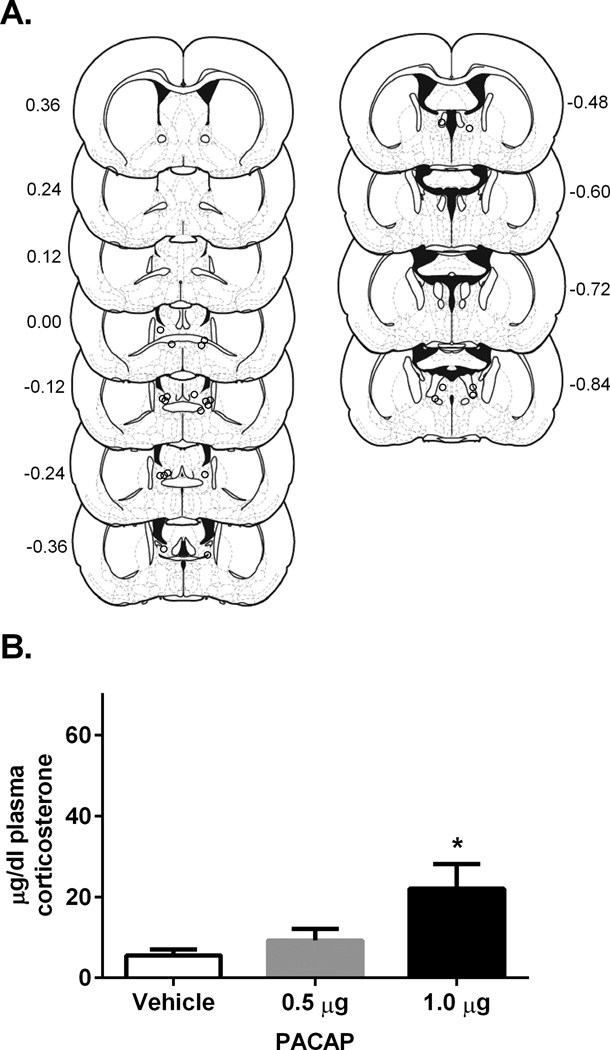

The centers of BNST infusion sites for drug treated rats are depicted in Figure 1A; note that dots may indicate cannula placement for more than one rat if infusion sites overlapped completely between rats. There was a significant effect of PACAP38 on plasma corticosterone levels for males 30 minutes following infusion F(2, 20) = 6.37, p<0.05, with Tukey post-hoc comparison indicating significantly higher corticosterone levels for rats treated with 1.0µg/0.5µl PACAP38 as compared to vehicle, p < 0.05 (Figure 1B). Hence, BNST infusion of PACAP38 elevated plasma corticosterone levels in male rats at the 1.0µg dose but not at lower doses.

Figure 1.

A. Estimates of center of drug infusion for experiment 1. Open dots represent one or multiple site(s) of drug infusion depicted on coronal sections as a distance (mm) from bregma. B. Dose- response of plasma corticosterone 30 minutes following BNST PACAP38 infusion for male rats. PACAP dose dependently increased plasma corticosterone levels 30 minutes following infusion in comparison to vehicle (0.05% bovine serum albumin, BSA). Infusion of 1.0 µg PACAP38 into the BNST caused a significant increase in plasma corticosterone levels in comparison to vehicle 30 minutes following infusion. * p < 0.05 compared to vehicle

Experiment 2

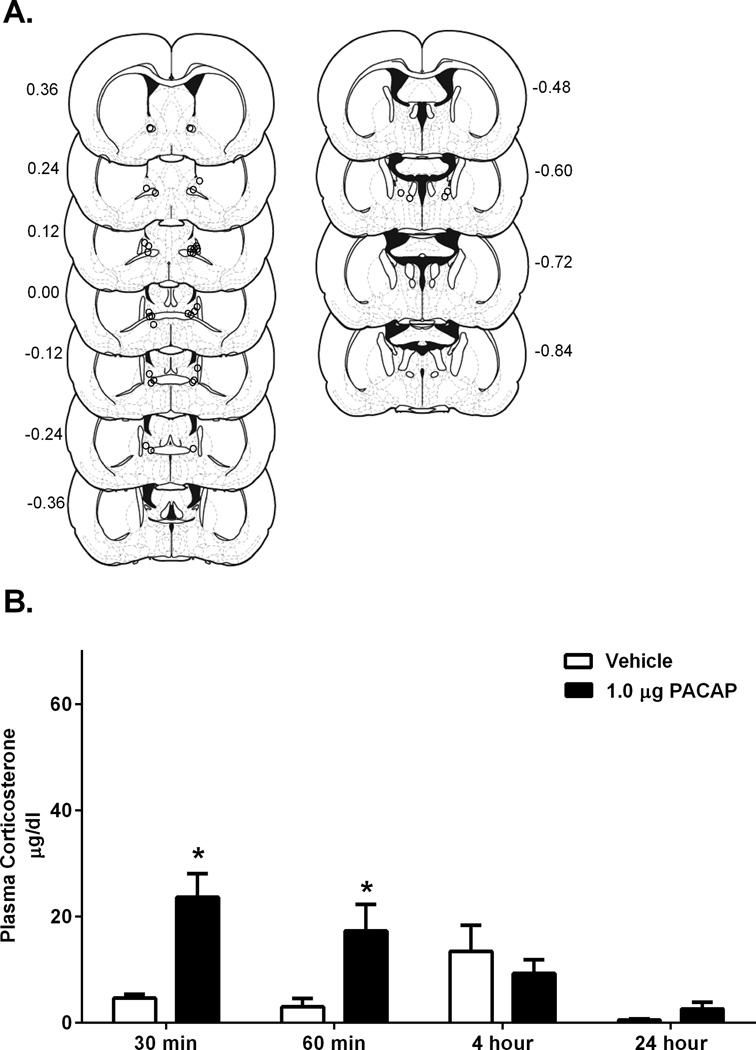

Cannulation placements for rats included in analysis for experiment 2 are depicted in Figure 2A. As noted above, because we did not obtain blood samples for each subject at every time point, we analyzed each time point individually, rather than using repeated measures ANOVA. There was a significant effect of PACAP treatment (as compared to vehicle infusion) on corticosterone levels at 30 minutes, t(18) = −4.65, p < 0.05, and 60 minutes, t(18) = −2.96, p < 0.05. This difference between corticosterone levels for PACAP and vehicle treated rats was not significant after 4 hours, t(24) = 0.71, p = 0.49, although at the 4 hour timepoint, blood samples from control rats exhibited higher than normal levels of corticosterone. We could not explain these data given any known characteristics of the experiment (animal cohort, experimenter, etc.), hence, it is likely that some of our control rats at this time point responded to an unknown variable (i.e. noise or vibration nearby one particular group of cages). Hence, it is possible that BNST PACAP infused rats may still have been slightly elevated at this point. There was no effect of BNST PACAP infusion (versus BNST vehicle infusion) on corticosterone levels at 24 hours, t(18) = −1.59, p = 0.13 (Figure 2B). Hence, the infusion of 1.0µg/0.5µl PACAP38 into the BNST produced a rise in corticosterone that peaked at 30 minutes after infusion and was returning to baseline levels around 4 hours. Furthermore, compared to vehicle infusion, 1.0 µg BNST PACAP38 infusion, a dose that increases anxiety-like behavior, also mimicked a stress response, producing plasma corticosterone levels similar to exposure to foot shock (Buck et al., 2011).

Figure 2.

A. Estimates of center of drug infusion for experiment 2. Open dots represent one or multiple site(s) of drug infusion depicted on coronal sections as a distance (mm) from bregma. B. Infusion of PACAP38 1.0 µg into the BNST caused a significant increase in blood plasma levels at 30 minutes and 60 minutes in comparison to vehicle (0.05% BSA). * p < 0.05 compared to vehicle

Experiment 3

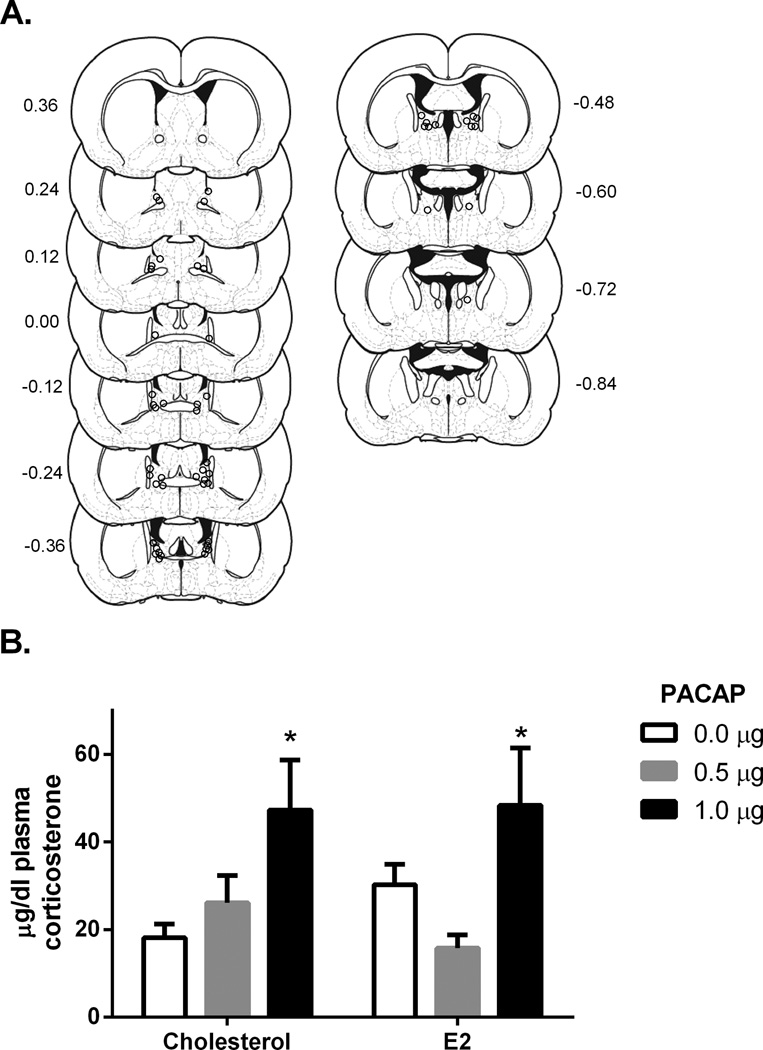

The centers of BNST infusion sites for drug treated female rats are depicted in Figure 3A, E2 levels, food intake, and body weight data for female rats in this study has been previously reported (Kocho-Schellenberg et al., 2014). E2 levels in E2 replaced rats were significantly higher than non-replaced rats (average increase of 26.17pg/ml, t(46) = 3.58, p < 0.005; E2: n = 25, cholesterol: n = 23), and were equivalent to high physiological levels (proestrous levels; (Becker et al., 2001)). A two-way ANOVA indicated a significant main effect of PACAP treatment for female rats, F(2, 43) = 7.706, p < 0.01, but no significant effect of estradiol treatment, F(1, 43) = 0.027, p = 0.869, or interaction between PACAP and estradiol treatment, F(2, 43) = 1.586, p = 0.216 (Figure 3B). Corticosterone levels were significantly increased for female rats treated with 1.0µg PACAP38 compared to vehicle treated rats as indicated through Tukey post-hoc comparisons, p < 0.05 (Figure 3B). Hence BNST PACAP also increased plasma corticosterone 30 min after infusion in female rats, and this effect was not dependent on E2 replacement.

Figure 3.

A. Estimates of center of drug infusion for experiment 3. Open dots represent one or multiple site(s) of drug infusion depicted on coronal sections as a distance (mm) from bregma. B. Dose- response of plasma corticosterone 30 minutes following BNST PACAP38 infusion for female rats. There was a main effect of PACAP, but no main effect of E2 treatment or interaction between PACAP and E2 treatment. Infusion of 1.0 µg PACAP38 into the BNST caused a significant increase in plasma corticosterone levels in comparison to vehicle (0.05% BSA) 30 minutes following infusion. * p < 0.05 compared to vehicle

Experiment 4

Experiment 4 was designed to determine whether ICV infusion in the vicinity of the BNST using the parameters outlined in experiment 1 and 2 could lead to increases in corticosterone release. There was no significant difference in plasma corticosterone levels between vehicle and PACAP38 treated rats 30 minutes following infusion, t(13) = −1.81, p = 0.094 (data not shown). Hence, it is likely that the effects observed in experiments 1 and 2 were mediated by PACAP38 action within the BNST itself, and not via leakage into the lateral ventricles.

Experiment 5

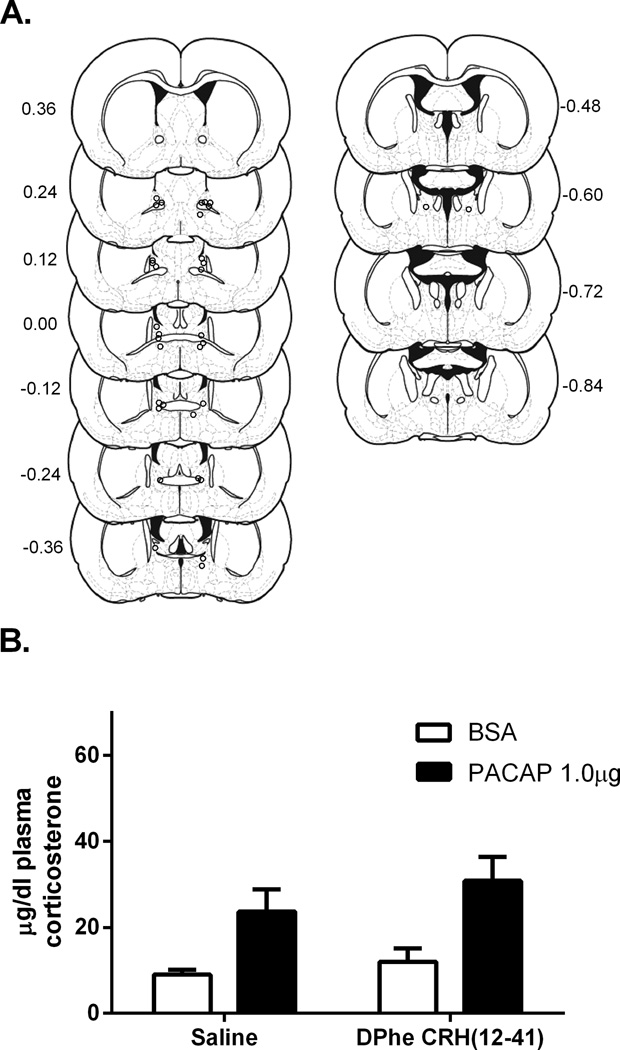

As noted above, we anticipated that BNST CRH receptor activation might

mediate the increased plasma corticosterone observed after BNST PACAP infusion. Cannulation placements for rats included in analysis for experiment 4 are depicted in Figure 4A. However, prior infusion with the CRH receptor antagonist D-Phe CRH (12–13 41) did not alter the increased plasma corticosterone following BNST PACAP (Figure 4B). Hence, two way ANOVA revealed a main effect of PACAP infusion F(1,29) = 17.12, p < .01, but no main effect of D-Phe CRH (12–41) treatment F(1,29 ) = 1.554, p = 0.22, and no interaction, F(1,29) = 0.27, p = 0.61. Hence, the effects of BNST PACAP infusion were not mediated by BNST CRH receptor activation.

Figure 4.

A. Estimates of center of drug infusion for experiment 5. Open dots represent one or multiple site(s) of drug infusion depicted on coronal sections as a distance (mm) from bregma. B. Infusion of D-Phe CRH(12–41) prior to 1.0 µg PACAP38 into the BNST did not block the PACAP38 induced corticosterone rise. There was a main effect of PACAP38 but no main effect of D-Phe CRH(12–41) or interaction between PACAP38 and D-Phe CRH(12–41).

Discussion

The current results suggest that BNST PACAP infusion activates the HPA axis. We demonstrated that intra-BNST PACAP38, at high but not low doses, increased plasma corticosterone levels in both male and female rats, with an increase that lasted for at least 60 minutes following infusion. We also demonstrated that this increase is likely not due to leakage of infused PACAP38 into the nearby lateral ventricles, and independent of BNST CRH receptor activation.

The increase in plasma corticosterone levels following BNST PACAP38 infusion occurred at a dose that was similar to that required to increase baseline startle responding (Hammack et al., 2009), and decrease food intake (Kocho-Schellenberg et al., 2014). Both anxiety-like behavior and the corticosterone rise following BNST PACAP38 infusion followed a similar timecourse. We previously reported that enhanced startle responding developed within 20–30 min of BNST PACAP38 infusion and still pronounced 40 min after infusion, and similarly, the increased plasma corticosterone levels reported here were most pronounced at 30 minutes and were still elevated, albeit lower than at 30 minutes, at 60 minutes following BNST PACAP38 infusion. Moreover, the peak levels and timecourse of the corticosterone response produced after 1.0µg of BNST PACAP38 were physiologically relevant as they were comparable to those observed after 30 minutes of restraint stress (Radley et al., 2009). However, it is unknown how long BNST-infused PACAP38 may remain in BNST tissue post-infusion. Hence, the extended effects of BNST PACAP38 infusion may result from multiple mechanisms; the initiation of pathways that result in sustained activation due their intrinsic network properties and/or the continued activation of these circuits by exogenous PACAP that has not yet been degraded.

Increased circulating corticosterone levels following PACAP38 BNST infusion was observed for both males and females. Ovariectomized females had been implanted with subcutaneous implants of either cholesterol or E2 in order to investigate potential interactions between E2 and PACAP signaling; however, we found no interaction. While the effects of BNST PACAP on corticosterone may not depend on E2 levels, it remains possible that we have not optimized the E2 treatment to observe an interaction. The effects of E2 may require lower or higher replacement levels, and/or a treatment regimen that allows E2 to cycle. Interestingly, females appeared to release higher levels of corticosterone as compared to male rats. While this may be indicative of a sex difference in the amount of hormones released by the HPA axis, it remains possible that these differences were mediated by procedural differences between the two studies. For example, female rats were gonadectomized while males were not; moreover, due to their smaller size, it may have taken slightly longer to obtain blood samples from female rats.

Stroth et al. (2009) suggested that PACAP is a “master regulator” of stress responses, due to the role of PACAP in regulating stress responding at multiple levels in the brain and periphery. For example, PACAP knock-out mice do not exhibit stress-induced increases in hypothalamic CRH mRNA levels, and hypothalamic activation and corticosterone release are attenuated when stressor exposure is prolonged (Stroth and Eiden, 2010). Consistent with a role for PACAP in activating multiple levels of the HPA axis, in vitro treatment of pituitary and hypothalamic cells with PACAP increases cAMP production (Kageyama et al., 2007; Miyata et al., 1989), and PACAP release may play a key role in regulating high frequency stress-associated signaling at the adrenomedullary synapse (Smith and Eiden, 2012).

Several reports have suggested that the BNST represents a critical relay station in the regulation of HPA activity by extrahypothalamic limbic structures (Herman et al., 2005; Radley and Sawchenko, 2011). Hence, our findings that BNST PACAP leads to HPA activation extend the claim by Eiden, Stroth and colleagues that PACAP is a “master regulator” of stress responding (Stroth et al., 2011a), suggesting that PACAP in extrahypothalamic sites like the BNST may play a key role in the initiation of HPA responding to threat. PACAP may exert effects on HPA activation through other brain regions, as ICV PACAP administration increased CRH levels (Dore et al., 2013; Grinevich et al., 1997) and activation of CRH containing cells in the paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus (PVN) (Agarwal et al., 2005), as well as increased CRH levels in the central amygdala (CeA) (Dore et al., 2013). PACAP null mice demonstrate reduced PVN activation and attenuated corticosterone rise in response to social defeat (Lehmann et al., 2013), as well as attenuated PVN CRH levels and corticosterone release following restraint stress (Stroth et al., 2011b). PACAP has also been demonstrated to directly increase CRH expression in hypothalamic cells (Stroth et al., 2011b). Although the current set of studies did not include PACAP38 infusion into these regions, the above studies suggest that PACAP is likely able to modulate HPA activity through actions outside the BNST.

BNST activity has been argued to mediate behavioral states associated with anxiety (Waddell et al., 2006; Walker et al., 2009), and also plays a critical role in regulating activity of the HPA-axis (Herman et al., 2005; Radley and Sawchenko, 2011). Hence, we and others have argued that the BNST may be a critical nexus between stress and emotion, and maladaptive BNST activity may be critical for mood and anxiety disorders associated with stressor exposure, as well as the HPA dysregulation that often accompanies these disorders. Many neuropeptide populations are expressed in the BNST oval nucleus, and we have argued that the activation of BNST PACAP systems is critical for stress-induced anxiety (Hammack et al., 2009; Hammack et al., 2010). The present results suggest that the activation of BNST PACAP systems may also critically regulate HPA activity in addition to anxiety-like behavior, and several characteristics of this emerging circuitry suggest that its activation may promote longterm changes in stress- and anxiety-like responding. First, recent arguments have suggested that the BNST mediates sustained anxiety-like responding to long duration anxiogenic stimuli (Waddell et al., 2006; Walker et al., 2009); hence, the BNST is likely activated in situations where its activation must be sustained. Second, several lines of evidence have suggested that BNST activity is recruited following chronic/repeated stress, likely via increases in several indices of neuroplasticity (Dumont et al., 2008; Pego et al., 2008; Vyas et al., 2003). It is therefore notable that in addition to enhancing the acute excitability of neurons (Sun et al., 2003), PACAP has well-described neurotrophic properties, and may promote anxiety-like behavior by enhancing BNST neurite outgrowth and synapse formation (see (Hammack et al., 2010) for review). Third, based on the present results, the sustained or repeated activation of BNST PACAP systems would likely lead to chronically elevated glucocorticoid levels; chronically elevated plasma glucocorticoid levels may on their own increase BNST CRH expression, BNST PACAP expression, and BNST neuroplasticity (Pego et al., 2008; Schulkin et al., 1998). Hence, the present report continues to support emerging evidence that the activation of BNST PACAP plays a critical role in mediating the consequences of stressor exposure, and may also promote the maladaptive changes that lead to stress-related psychopathology.

As noted above, our data suggest that the effects of intra-BNST PACAP38 were likely mediated by action in the BNST rather than the leakage of PACAP38 into the ventricular system. While ICV PACAP38 treatment has been shown to lead to activation of the HPA axis, these effects were reported following the infusion of much higher volumes than the 0.5µl per side reported here (for example, 6.0µl (Agarwal et al., 2005) and 10.0µl (Grinevich et al., 1997)). In the present report, using the exact same infusion technique, dose and volume of PACAP38 that was effective in elevating corticosterone when infused into the BNST, we found that PACAP38 did not significantly alter corticosterone levels when infused into the lateral ventricles immediately above the BNST. This result is consistent with our previous finding that ICV PACAP38 did not mimic the effects of BNST PACAP38 on anorexia and weight loss (Kocho-Schellenberg et al., 2014). Interestingly, while PACAP38 may have direct hypothalamic effects to enhance HPA-axis activity, the current results suggest that the BNST could also be an important site of action for the increased corticosterone observed after ICV PACAP38 infused at higher volumes (Agarwal et al., 2005; Grinevich et al., 1997).

PACAP binds to three receptor subtypes, including the PAC1, VPAC1 and VPAC2 with similar affinities (Vaudry et al., 2000). Notably, we observed an increase in PACAP and PAC1 receptor expression following repeated variate stress, but no changes in VPAC1 or VPAC2 receptor, or VIP expression (Hammack et al., 2009; Hammack et al., 2010). While BNST PAC1 receptors are stress-sensitive, it is currently unknown which receptor subtype(s) mediate the effects of BNST PACAP38 infusion on anxiety-like behavior or plasma corticosterone. Recent reports from our lab have also demonstrated differing effects of PACAP38 infusion on food intake and weight gain dependent on the BNST region targeted, such that posterior but not anterior BNST PACAP38 infusion promoted attenuated weight gain 24 hours later (Kocho-Schellenberg et al., 2014), and different BNST subregions may differentially regulate glucocorticoid release (Choi et al., 2008; Choi et al., 2007; Radley and Sawchenko, 2011). The investigation of the subregional specificity of PACAP infusion on glucocorticoid release is an important future direction for the present work.

PACAP containing fibers are found in close proximity to CRH-positive neurons in the BNST (Kozicz et al., 1998); we and others have argued that the effects of PACAP may be mediated by BNST CRH activation. BNST CRH activity has been heavily implicated in mediating anxiety-like behavior, and BNST CRH receptor antagonism attenuates anxiety-like behavioral responding to bright lights (Walker and Davis, 2002), ICV CRH administration (Lee and Davis, 1997), BNST infusions of calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP, (Sink et al.)), and stress-induced reinstatement of drug seeking behavior (Erb et al., 2001). Recently, it was also shown that ICV administration of D-Phe CRH (12–41) was able to block the anxiogenic effects of ICV administration of PACAP38 (Dore, 2013). Surprisingly, in the present study BNST CRH receptor antagonism did not block the increased plasma corticosterone observed following BNST PACAP38 infusion. This inability of D-Phe CRH (12–41) to block corticosterone rise following ICV PACAP38 administration was also observed by Dore et al. (2013). Notably, we used a dose of D-Phe CRH (12–41) that was sufficient to block the behavioral consequences of inescapable tailshock when infused into the dorsal raphe nucleus (Hammack et al., 2002), hence, it is unlikely that the inability of BNST D-Phe CRH (12–41) to block the effects of BNST PACAP38 was due to insufficient CRH receptor blockade in the BNST. Our data suggest several possibilities. 1) The BNST circuits that mediate anxiety-like behavior could differ from those that regulate PVN activity, such that BNST CRH receptor activation is required for the former, but not the latter. Hence, PACAP may activate BNST CRH neurons that project to anxiety-related structures such as the dorsal raphe nucleus to promote anxiety-like behavior, while at the same time regulating activity in non-CRH neurons that promote glucocorticoid release. In this scenario, BNST CRH antagonism may attenuate the anxioenic effects of PACAP without reducing the glucocorticoid response. 2) BNST PACAP activation may activate PVN-projecting CRH neurons in the BNST, leading to PVN CRH release, which would not be blocked by BNST CRH antagonism, but would be blocked by PVN CRH antagonism. In this scenario the PVN-projecting CRH neurons may be located in ventral regions of the anterolateral BNST, rather than the BNST oval nucleus (Dong et al., 2001). 3) Despite the close proximity of PACAP fibers on CRH-expressing BNST neurons, the effects of BNST PACAP receptor activation may be truly independent of CRH function, and instead be mediated via the regulation of other neurotransmitters/peptides including GABA and enkephalin. For example, BNST PACAP may regulate GABA release from CRH-expressing neurons, since CRH can be coexpressed with GABA in the BNST (Dabrowska et al., 2011), and the effects of BNST PACAP might be attenuated by the selective destruction of PVN-projecting GABAergic neurons in the BNST. Lastly, it is notable that the role of BNST CRH may change following chronic, repeated, or severe stressor exposure, such that CRH may play a more prominent role in mediating the effects of PACAP following stress.

As noted above, PACAP levels and SNPs in the PACAP and PAC1 receptor gene have been found to be associated with multiple psychiatric disease states, some of which are associated with HPA-dysfunction (Almli et al., 2013; Hashimoto et al., 2010; Ressler et al., 2011; Uddin et al., 2013; Wang et al., 2013). Importantly, maladaptive BNST activity has also been implicated in these disorders; hence, changes in BNST PACAP signaling may be critical in producing the HPA dysfunction observed in stress-related psychophathology. This intriguing possibility highlights the need for further study into these stress response systems, but these gene association studies support data from rodent models implicating PACAP systems in stress- and anxiety-related brain circuits. A clearer understanding of the role of PACAP in these circuits may clarify both the gene associations described above, and the mechanisms of stress-related disease.

Acknowledgements

We thank Micaela Carswell, who provided much support in the laboratory. We are also grateful to Terrence Deak and Cara Hueston for their assistance with this project.

Funding

This work was supported by grants MH-97988 and MH-072088 (SEH). Portions of the work were also supported by National Alliance for Research on Schizophrenia and Depression (NARSAD) and the University of Vermont College of Arts and Sciences, as well as funds from the Center of Biomedical Research Excellence (COBRE) in Neuroscience at the University of Vermont (National Institute of Health NCRR P20RR16435).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributions

Dr. Lezak designed the studies, conducted the experiments and experimental analyses, and wrote multiple drafts of the manuscript.

Ms. Roelke conducted several of the experiments and experimental analyses.

Ms. Harris conducted several of the experiments and experimental analyses.

Ms. Choi conducted several of the experiments and experimental analyses.

Mr. Edwards conducted several of the experiments and experimental analyses.

Mr. Gick conducted several of the experiments and experimental analyses.

Ms. Cocchiaro conducted several of the experiments and experimental analyses.

Mr. Missig conducted several of the experiments and experimental analyses.

Dr. Roman conducted several of the experiments and experimental analyses.

Dr. Braas designed the studies and aided in the writing of this manuscript.

Dr. Toufexis designed the studies and aided in the writing of this manuscript.

Dr. May designed the studies and aided in the writing of this manuscript.

Dr. Hammack obtained funding for this work, designed the studies, and aided in the writing of this manuscript.

All authors contributed to and have approved the final manuscript.

Disclosures

Dr. Lezak declares no conflict of interest.

Ms. Roelke declares no conflict of interest.

Ms. Harris declares no conflict of interest.

Ms. Choi declares no conflict of interest.

Mr. Edwards declares no conflict of interest.

Mr. Gick declares no conflict of interest.

Ms. Cocchiaro declares no conflict of interest.

Mr. Missig declares no conflict of interest.

Dr. Roman declares no conflict of interest.

Dr. Braas declares no conflict of interest.

Dr. Toufexis declares no conflict of interest.

Dr. May declares no conflict of interest.

Dr. Hammack declares no conflict of interest.

Literature Cited

- Agarwal A, Halvorson LM, Legradi G. Pituitary adenylate cyclase-activating polypeptide (PACAP) mimics neuroendocrine and behavioral manifestations of stress: Evidence for PKA-mediated expression of the corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH) gene. Brain Research. Molecular Brain Research. 2005;138:45–57. doi: 10.1016/j.molbrainres.2005.03.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Almli LM, Mercer KB, Kerley K, Feng H, Bradley B, Conneely KN, Ressler KJ. ADCYAP1R1 genotype associates with post-traumatic stress symptoms in highly traumatized African-American females. American journal of medical genetics. Part B, Neuropsychiatric genetics : the official publication of the International Society of Psychiatric Genetics. 2013;162B:262–272. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.32145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker C, Thiebot MH, Touitou Y, Hamon M, Cesselin F, Benoliel JJ. Enhanced cortical extracellular levels of cholecystokinin-like material in a model of anticipation of social defeat in the rat. Journal of Neuroscience. 2001;21:262–269. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-01-00262.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buck HM, Hueston CM, Bishop C, Deak T. Enhancement of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis but not cytokine responses to stress challenges imposed during withdrawal from acute alcohol exposure in Sprague-Dawley rats. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2011;218:203–215. doi: 10.1007/s00213-011-2388-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi DC, Evanson NK, Furay AR, Ulrich-Lai YM, Ostrander MM, Herman JP. The anteroventral bed nucleus of the stria terminalis differentially regulates hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenocortical axis responses to acute and chronic stress. Endocrinology. 2008;149:818–826. doi: 10.1210/en.2007-0883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi DC, Furay AR, Evanson NK, Ostrander MM, Ulrich-Lai YM, Herman JP. Bed nucleus of the stria terminalis subregions differentially regulate hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis activity: implications for the integration of limbic inputs. Journal of Neuroscience. 2007;27:2025–2034. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4301-06.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dabrowska J, Hazra R, Ahern TH, Guo JD, McDonald AJ, Mascagni F, Muller JF, Young LJ, Rainnie DG. Neuroanatomical evidence for reciprocal regulation of the corticotrophin-releasing factor and oxytocin systems in the hypothalamus and the bed nucleus of the stria terminalis of the rat: Implications for balancing stress and affect. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2011;36:1312–1326. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2011.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong HW, Petrovich GD, Watts AG, Swanson LW. Basic organization of projections from the oval and fusiform nuclei of the bed nuclei of the stria terminalis in adult rat brain. Journal of Comparative Neurology. 2001;436:430–455. doi: 10.1002/cne.1079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dore R, Iemolo A, Smith KL, Wang X, Cottone P, Sabino V. CRF mediates the anxiogenic and anti-rewarding, but not the anorectic effects of PACAP. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2013;38:2160–2169. doi: 10.1038/npp.2013.113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dumont EC, Rycroft BK, Maiz J, Williams JT. Morphine produces circuit-specific neuroplasticity in the bed nucleus of the stria terminalis. Neuroscience. 2008;153:232–239. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2008.01.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erb S, Salmaso N, Rodaros D, Stewart J. A role for the CRF-containing pathway from central nucleus of the amygdala to bed nucleus of the stria terminalis in the stress-induced reinstatement of cocaine seeking in rats. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2001;158:360–365. doi: 10.1007/s002130000642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grinevich V, Fournier A, Pelletier G. Effects of pituitary adenylate cyclase-activating polypeptide (PACAP) on corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH) gene expression in the rat hypothalamic paraventricular nucleus. Brain Res. 1997;773:190–196. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(97)01011-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammack SE, Cheung J, Rhodes KM, Schutz KC, Falls WA, Braas KM, May V. Chronic stress increases pituitary adenylate cyclase-activating peptide (PACAP) and brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) mRNA expression in the bed nucleus of the stria terminalis (BNST): roles for PACAP in anxiety-like behavior. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2009;34:833–843. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2008.12.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammack SE, Cooper MA, Lezak KR. Overlapping neurobiology of learned helplessness and conditioned defeat: implications for PTSD and mood disorders. Neuropharmacology. 2012;62:565–575. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2011.02.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammack SE, Richey KJ, Schmid MJ, LoPresti ML, Watkins LR, Maier SF. The role of corticotropin-releasing hormone in the dorsal raphe nucleus in mediating the behavioral consequences of uncontrollable stress. Journal of Neuroscience. 2002;22:1020–1026. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-03-01020.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammack SE, Roman CW, Lezak KR, Kocho-Shellenberg M, Grimmig B, Falls WA, Braas K, May V. Roles for pituitary adenylate cyclase-activating peptide (PACAP) expression and signaling in the bed nucleus of the stria terminalis (BNST) in mediating the behavioral consequences of chronic stress. Journal of molecular neuroscience : MN. 2010;42:327–340. doi: 10.1007/s12031-010-9364-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hashimoto R, Hashimoto H, Shintani N, Chiba S, Hattori S, Okada T, Nakajima M, Tanaka K, Kawagishi N, Nemoto K, Mori T, Ohnishi T, Noguchi H, Hori H, Suzuki T, Iwata N, Ozaki N, Nakabayashi T, Saitoh O, Kosuga A, Tatsumi M, Kamijima K, Weinberger DR, Kunugi H, Baba A. Pituitary adenylate cyclase-activating polypeptide is associated with schizophrenia. Molecular Psychiatry. 2007;12:1026–1032. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hashimoto R, Hashimoto H, Shintani N, Ohi K, Hori H, Saitoh O, Kosuga A, Tatsumi M, Iwata N, Ozaki N, Kamijima K, Baba A, Takeda M, Kunugi H. Possible association between the pituitary adenylate cyclase-activating polypeptide (PACAP) gene and major depressive disorder. Neurosci Lett. 2010;468:300–302. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2009.11.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herman JP, Ostrander MM, Mueller NK, Figueiredo H. Limbic system mechanisms of stress regulation: hypothalamo-pituitary-adrenocortical axis. Progress in Neuro-Psychopharmacology & Biological Psychiatry. 2005;29:1201–1213. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2005.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kageyama K, Hanada K, Iwasaki Y, Sakihara S, Nigawara T, Kasckow J, Suda T. Pituitary adenylate cyclase-activating polypeptide stimulates corticotropin-releasing factor, vasopressin and interleukin-6 gene transcription in hypothalamic 4B cells. The Journal of endocrinology. 2007;195:199–211. doi: 10.1677/JOE-07-0125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalin NH, Shelton SE, Fox AS, Oakes TR, Davidson RJ. Brain regions associated with the expression and contextual regulation of anxiety in primates. Biol Psychiatry. 2005;58:796–804. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.05.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kocho-Schellenberg M, Lezak KR, Harris OM, Roelke E, Gick N, Choi I, Edwards S, Wasserman E, Toufexis DJ, Braas KM, May V, Hammack SE. Pituitary Adenylate Cyclase Activating Peptide (PACAP) in the Bed Nucleus of the Stria Terminalis (BNST) Produces Anorexia and Weight Loss in Male and Female Rats. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2014 [Google Scholar]

- Kozicz T, Vigh S, Arimura A. Axon terminals containing PACAP- and VIP-immunoreactivity form synapses with CRF-immunoreactive neurons in the dorsolateral division of the bed nucleus of the stria terminalis in the rat. Brain Research. 1997;767:109–119. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(97)00737-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kozicz T, Vigh S, Arimura A. Immunohistochemical evidence for PACAP and VIP interaction with met-enkephalin and CRF containing neurons in the bed nucleus of the stria terminalis. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1998;865:523–528. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1998.tb11229.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee Y, Davis M. Role of the hippocampus, the bed nucleus of the stria terminalis, and the amygdala in the excitatory effect of corticotropin-releasing hormone on the acoustic startle reflex. J Neurosci. 1997;17:6434–6446. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-16-06434.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehmann ML, Mustafa T, Eiden AM, Herkenham M, Eiden LE. PACAP-deficient mice show attenuated corticosterone secretion and fail to develop depressive behavior during chronic social defeat stress. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2013;38:702–715. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2012.09.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyata A, Arimura A, Dahl RR, Minamino N, Uehara A, Jiang L, Culler MD, Coy DH. Isolation of a novel 38 residue-hypothalamic polypeptide which stimulates adenylate cyclase in pituitary cells. Biochemical & Biophysical Research Communications. 1989;164:567–574. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(89)91757-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pego JM, Morgado P, Pinto LG, Cerqueira JJ, Almeida OFX, Sousa N. Dissociation of the morphological correlates of stress-induced anxiety and fear. European Journal of Neuroscience. 2008;27:1503–1516. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2008.06112.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radley JJ, Gosselink KL, Sawchenko PE. A discrete GABAergic relay mediates medial prefrontal cortical inhibition of the neuroendocrine stress response. J Neurosci. 2009;29:7330–7340. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5924-08.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radley JJ, Sawchenko PE. A common substrate for prefrontal and hippocampal inhibition of the neuroendocrine stress response. J Neurosci. 2011;31:9683–9695. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.6040-10.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ressler KJ, Mercer KB, Bradley B, Jovanovic T, Mahan A, Kerley K, Norrholm SD, Kilaru V, Smith AK, Myers AJ, Ramirez M, Engel A, Hammack SE, Toufexis D, Braas KM, Binder EB, May V. Post-traumatic stress disorder is associated with PACAP and the PAC1 receptor. Nature. 2011;470:492–497. doi: 10.1038/nature09856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulkin J, Gold PW, McEwen BS. Induction of corticotropin-releasing hormone gene expression by glucocorticoids: implication for understanding the states of fear and anxiety and allostatic load. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 1998;23:219–243. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4530(97)00099-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sink KS, Chung A, Ressler KJ, Davis M, Walker DL. Anxiogenic effects of CGRP within the BNST may be mediated by CRF acting at BNST CRFR1 receptors. Behav Brain Res. 243:286–293. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2013.01.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith CB, Eiden LE. Is PACAP the major neurotransmitter for stress transduction at the adrenomedullary synapse? J Mol Neurosci. 2012;48:403–412. doi: 10.1007/s12031-012-9749-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Somerville LH, Whalen PJ, Kelley WM. Human bed nucleus of the stria terminalis indexes hypervigilant threat monitoring. Biol Psychiatry. 2010;68:416–424. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2010.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stroth N, Eiden LE. Stress hormone synthesis in mouse hypothalamus and adrenal gland triggered by restraint is dependent on pituitary adenylate cyclase-activating polypeptide signaling. Neuroscience. 2010;165:1025–1030. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2009.11.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stroth N, Holighaus Y, Ait-Ali D, Eiden LE. PACAP: a master regulator of neuroendocrine stress circuits and the cellular stress response. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2011a;1220:49–59. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2011.05904.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stroth N, Liu Y, Aguilera G, Eiden LE. Pituitary adenylate cyclase-activating polypeptide controls stimulus-transcription coupling in the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis to mediate sustained hormone secretion during stress. Journal of Neuroendocrinology. 2011b;23:944–955. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2826.2011.02202.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun QQ, Prince DA, Huguenard JR. Vasoactive intestinal polypeptide and pituitary adenylate cyclase-activating polypeptide activate hyperpolarization-activated cationic current and depolarize thalamocortical neurons in vitro. J Neurosci. 2003;23:2751–2758. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-07-02751.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uddin M, Chang SC, Zhang C, Ressler K, Mercer KB, Galea S, Keyes KM, McLaughlin KA, Wildman DE, Aiello AE, Koenen KC. Adcyap1r1 genotype, posttraumatic stress disorder, and depression among women exposed to childhood maltreatment. Depress Anxiety. 2013;30:251–258. doi: 10.1002/da.22037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaudry D, Falluel-Morel A, Bourgault S, Basille M, Burel D, Wurtz O, Fournier A, Chow BK, Hashimoto H, Galas L, Vaudry H. Pituitary adenylate cyclase-activating polypeptide and its receptors: 20 years after the discovery. Pharmacological Reviews. 2009;61:283–357. doi: 10.1124/pr.109.001370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaudry D, Gonzalez BJ, Basille M, Yon L, Fournier A, Vaudry H. Pituitary adenylate cyclase-activating polypeptide and its receptors: from structure to functions. Pharmacological Reviews. 2000;52:269–324. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vyas A, Bernal S, Chattarji S. Effects of chronic stress on dendritic arborization in the central and extended amygdala. Brain Research. 2003;965:290–294. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(02)04162-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waddell J, Morris RW, Bouton ME. Effects of bed nucleus of the stria terminalis lesions on conditioned anxiety: aversive conditioning with long-duration conditional stimuli and reinstatement of extinguished fear. Behavioral Neuroscience. 2006;120:324–336. doi: 10.1037/0735-7044.120.2.324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker DL, Davis M. Light enhanced startle: futher pharmacological and behavioral characterization. Psychopharmacology. 2002;159:304–310. doi: 10.1007/s002130100913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker DL, Miles LA, Davis M. Selective participation of the bed nucleus of the stria terminalis and CRF in sustained anxiety-like versus phasic fear-like responses. Progress in Neuro-Psychopharmacology & Biological Psychiatry. 2009;33:1291–1308. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2009.06.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang L, Cao C, Wang R, Qing Y, Zhang J, Zhang XY. PAC1 receptor (ADCYAP1R1) genotype is associated with PTSD’s emotional numbing symptoms in Chinese earthquake survivors. Journal of affective disorders. 2013;150:156–159. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2013.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]