Abstract

Understanding how lower-limb amputation affects walking stability, specifically in destabilizing environments, is essential for developing effective interventions to prevent falls. This study quantified mediolateral margins of stability (MOS) and MOS sub-components in young individuals with traumatic unilateral transtibial amputation (TTA) and young able-bodied individuals (AB). Thirteen AB and nine TTA completed five 3-minute walking trials in a Computer Assisted Rehabilitation ENvironment (CAREN) system under three each of three test conditions: no perturbations, pseudo-random mediolateral translations of the platform, and pseudo-random mediolateral translations of the visual field. Compared to the unperturbed trials, TTA exhibited increased mean MOS and MOS variability during platform and visual field perturbations (p < 0.010). Also, AB exhibited increased mean MOS during visual field perturbations and increased MOS variability during both platform and visual field perturbations (p < 0.050). During platform perturbations, TTA exhibited significantly greater values than AB for mean MOS (p < 0.050) and MOS variability (p < 0.050); variability of the lateral distance between the center of mass (COM) and base of support at initial contact (p < 0.005); mean and variability of the range of COM motion (p < 0.010); and variability of COM peak velocity (p < 0.050). As determined by mean MOS and MOS variability, young and otherwise healthy individuals with transtibial amputation achieved stability similar to that of their able-bodied counterparts during unperturbed and visually-perturbed walking. However, based on mean and variability of MOS, unilateral transtibial amputation was shown to have affected walking stability during platform perturbations.

Keywords: walking, transtibial amputation, perturbations, lateral stability, center of mass

Introduction

Up to 50% of individuals with lower-limb amputation experience a fall each year (Miller et al., 2001; Miller and Deathe, 2004; Pauley et al., 2006). As a result, fall prevention is commonly emphasized during rehabilitation (Gooday and Hunter, 2004). During daily activities, individuals must respond to various disturbances, or perturbations, caused by unpredictable or irregular environments (i.e. uneven terrain, crowded spaces, obstructions) to maintain stability and avoid trips, stumbles, and falls. Humans are less laterally stable while walking (Kuo, 1999; Bauby and Kuo, 2000; Dean et al., 2007; O'Connor and Kuo, 2009; Sinitksi et al., 2012) and most falls occur during walking (Tinetti et al., 1995; Niino et al., 2000). Individuals with lower-limb amputation are commonly assumed to be more unstable than able-bodied individuals due to the increased incidence of falls, and because they lack active ankle control (Viton et al., 2000).

When walking in destabilizing environments, individuals alter their movement to avoid loss of balance or falls. According to Hof et al. (2005), gait should be mediolaterally stable when the mediolateral velocity-adjusted position of the center of mass (COM), or the ‘extrapolated centre of mass’ (XcoM), is held inside the mediolateral edge of the base of support (BOS) thus resulting in positive mediolateral margins of stability (MOS). Individuals can adjust their foot placement or their COM motion in order to control MOS magnitude (Maclellan and Patla, 2006; MacLellan and Patla, 2006; Hof et al., 2007; Hof, 2008; Rosenblatt and Grabiner, 2010; McAndrew Young and Dingwell, 2012; McAndrew Young et al., 2012). Recent studies have used continuous perturbations to determine how able-bodied individuals respond (AB) to destabilizing environments (McAndrew et al., 2010; McAndrew et al., 2011; Hak et al., 2012; McAndrew Young et al., 2012; Sinitksi et al., 2012; Hak et al., 2013). Continuous pseudorandom mediolateral perturbations cause both mean and variability of MOS to increase in AB (McAndrew Young et al., 2012). Adjustments, such as taking wider steps during walking, also increase mean MOS (Hak et al., 2012; McAndrew Young and Dingwell, 2012; McAndrew Young et al., 2012) and MOS variability (McAndrew Young and Dingwell, 2012). Therefore, in continuous perturbation protocols MOS values may indicate the anticipatory changes employed to maintain stability when exposed to destabilization (Hak et al., 2012; Hak et al., 2013).

Individuals with above-knee amputation exhibited greater mean MOS in the prosthetic leg than in the intact leg (Hof et al., 2007). Individuals with lower-limb amputation also have exhibited MOS asymmetries between the prosthetic limb and the intact limb (Hof et al., 2007; Gates et al., 2013). Similar to able-bodied individuals, individuals with unilateral transtibial amputation (TTA) exhibited increased mean mediolateral MOS when exposed to a destabilizing loose rock surface (Gates et al., 2013). Gates et al. (2013) further broke down MOS into subcomponents based on foot placement and COM movement to determine the changes made to maintain a stable MOS when walking on rocks. TTA differed from AB, exhibiting greater distance between BOS and COM at initial contact (BOS-COMIC), greater range of COM motion (ROM), and greater COM peak velocity (PV). However, it is unknown how these subcomponents change in TTA during mediolateral perturbations.

The purpose of this study was to determine how unilateral transtibial amputation affects walking stability in a destabilizing environment. To isolate the effect of the amputation on walking stability independent of comorbid factors, young TTA of traumatic etiology were recruited. Furthermore, young adults with lower limb amputation been found to fall at nearly the same rate as older individuals with lower limb amputation (Miller et al., 2001). We quantified mediolateral MOS in AB and TTA as they responded to continuous pseudorandom perturbations of the walking surface or visual field. Based on recent findings (Hof et al., 2007; McAndrew et al., 2011; Gates et al., 2013), we hypothesized that mean MOS and MOS variability would be greater in TTA than AB during both unperturbed and perturbed walking. Finally, we expected that TTA would exhibit greater mean and variability of foot placement and COM movement than AB, as described by MOS sub-components.

Methods

Participants included nine young, healthy individuals with traumatic unilateral transtibial amputation and thirteen young, healthy able-bodied adults (Table 1). All TTA were screened to ensure they were free of orthopedic and neurological disorders to the intact side. All participants provided written informed consent prior to participation.

Table 1.

Subject characteristic data for able-bodied individuals (AB) and individuals with transtibial amputation (TTA).

| Characteristics | AB (N = 13) | TTA (N = 9) |

|---|---|---|

| Age (yrs) | 24.8 (6.9) | 30.7 (6.8) |

| Sex (female/male) | 3/10 | 0/9 |

| Height (m) | 1.75 (0.08) | 1.76 (0.11) |

| Leg Length (m) | 0.95 (0.05) | 0.95 (0.07) |

| Body mass (kg) | 79.3 (11.6) | 90.2 (16.1) |

Numbers are expressed as mean (SD). All between-group values are non-significant (p > 0.05).

Testing procedures closely resembled those used previously (McAndrew et al., 2010; McAndrew et al., 2011). All subjects walked in a Computer Assisted Rehabilitation ENvironment (CAREN; Motek, Amsterdam, Netherlands) which consisted of a 7 m-diameter dome allowing projection of a 300° field-of-view virtual environment and a six degrees-of-freedom platform with embedded treadmill. The virtual reality scene depicted a dirt path through a forest with mountains in the background. White poles, 2.4 m in height and spaced every 3 m, lined the path to enhance the visual parallax (Bardy et al., 1996; McAndrew et al., 2010). Subjects were tethered to a safety harness mounted on the platform behind the treadmill and out of the subject's field of view.

Following a 6-minute warm-up period, each participant completed five 3-minute walking trials in the CAREN with each of the following conditions: no perturbation (NOP), platform perturbations (PLAT), and visual perturbations (VIS). Net visual progression through the virtual scene was matched to the treadmill speed for all conditions. During NOP, the platform was stationary and visual progression remained matched to the treadmill speed. During PLAT, the platform translated continuously while visual progression was unperturbed. During VIS, the platform was stationary and the virtual scene translated continuously. Platform and visual perturbations were designed to represent irregular environments such as uneven terrain and crowded spaces, respectively, that cause disturbances in walking stability. Platform and visual perturbations were imposed as pseudo-random oscillations in the mediolateral direction, consisting of a sum of 4 sine waves of incommensurate frequencies:

| (1) |

where A(t) was the translation amplitude in meters, Aw was a weighing factor in meters, and t was time in seconds (McAndrew et al., 2010). These frequencies fell in the range found by Warren et al. (1996) that people were most responsive to. Based on studies that explored the effect of responses to different perturbation magnitudes, amplitudes for platform and visual translations were weighed at Aw = 0.04 and Aw = 0.45, respectively, to elicit similar responses to each type of perturbation (Sinitksi et al., 2012; Terry et al., 2012). Maximum A(t) for PLAT and VIS were ±12.5 cm and ±140 cm, respectively. For all conditions participants walked at a constant speed scaled to their leg length:

| (2) |

where speed, v, is in m/s, g = 9.8 m/s2 and l was the subject's leg length in meters (McAndrew et al., 2010). The order of presentation for all conditions was randomized for each individual and balanced across subjects.

Kinematic data were collected at 60 Hz using a 24-camera Vicon motion capture system (Oxford Metrics, Oxford, UK). Positions of 57 markers along with digitized joint centers (Wilken et al., 2012), were reconstructed and labeled in Vicon Nexus software (Oxford Metric, Oxford, UK) and exported to Visual 3D (C-motion Inc, Germantown, MD). A 13-segment model was created for each subject to determine COM motion. To ensure participants were fully acclimated to each testing condition, data from the first trial of each condition were not analyzed.

Dynamic margins of stability were determined according to Hof et al. (2005). The extrapolated center of mass (XcoM) was calculated using the following equation:

| (3) |

where COMz and CȮMz are the mediolateral position and velocity of the COM, respectively, and where g was 9.8 m/s2 and hCOM was the approximate pendulum length based on height of the COM, calculated as 1.34 times the trochanteric height (Massen and Kodde, 1979). Dynamic margins of stability (MOS) were calculated as (Hof et al., 2005):

| (4) |

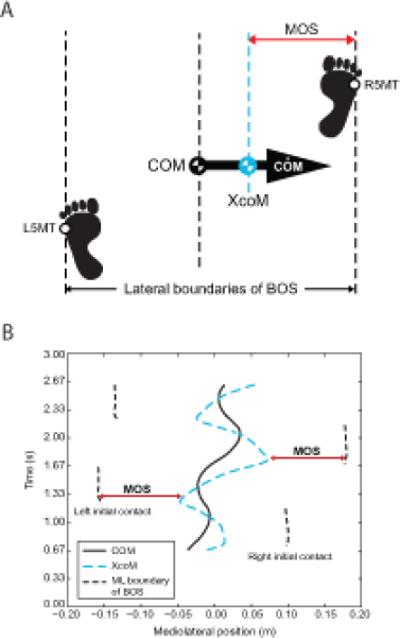

where BOS was the lateral boundary of the base of support. Here, we used the 5th metatarsal marker of the foot at heelstrike instead of the center of pressure as the lateral boundary of the BOS in order to represent the physical constraint of the BOS (Fig. 1A). The minimum value of MOS during the stance phase of each step (approximately 300 total steps per trial) was determined for each leg (Fig. 1B). Heel strikes were identified as the local minima of the vertical component of the C7 marker position (Dingwell and Marin, 2006; Dingwell et al., 2007). To allow consistency between conditions, MOS calculation during PLAT was adjusted relative to the platform by subtracting the velocity factor of the platform movement, ṖZ / ω0, from the XcoM value, where ṖZ was the mediolateral velocity of the platform.

Figure 1.

(A) Mediolateral MOS was defined as the mediolateral distance between the lateral border of the BOS and the vertical projection of XcoM. The lateral border of the BOS was defined by the 5th metatarsal marker of the lead foot (L5MT and R5MT for the left and right foot, respectively; right foot is shown leading). (B) Graphical representation of the MOS calculation.

Along with MOS, sub-components of MOS were calculated including BOS-COMIC, ROM, and PV in order to identify how foot placement and COM movement changed in response to destabilization (Gates et al., 2013). Within-subject variability of MOS and MOS subcomponents were calculated as the standard deviation across all trials for each condition. MOS and MOS sub-components were calculated using Matlab R2012a (Mathworks Inc, Natick, MA).

Dependent measures were compared using mixed design repeated measures ANOVAs. Separate ANOVAs were run to compare NOP with each perturbation condition. Condition (PLAT/NOP, VIS/NOP) and limb (TTA: prosthetic/intact, AB: right/left) served as within-subjects factors and subject group (TTA/AB) served as the between-subject factor. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS v19 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL).

Results

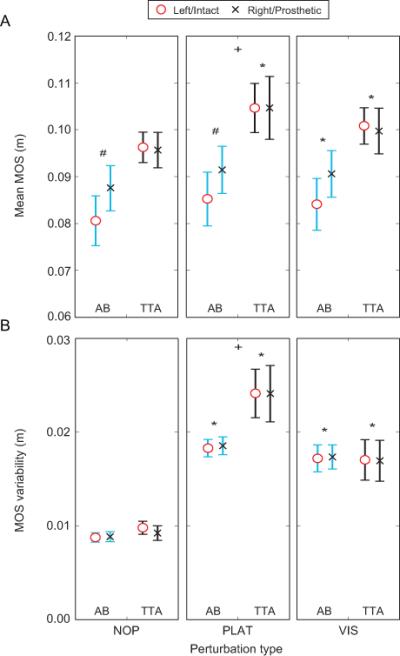

Mean MOS for TTA were significantly greater during both VIS and PLAT than NOP (p < 0.010; Fig. 2A). Mean MOS for AB was significantly greater during VIS than during NOP (p < 0.010; Fig. 2A), but were not significantly different between PLAT and NOP. Both TTA and AB exhibited greater MOS variability during both PLAT and VIS than NOP (p < 0.001; Fig. 2B). Mean MOS values in AB were significantly greater on the right limb than the left limb during NOP (p < 0.050; Fig. 2A) and approached significance during VIS (p = 0.052; Fig. 2A), but were not significantly different during PLAT. No significant differences for mean MOS were found between the intact and prosthetic sides in TTA. No significant between-limb differences were found in MOS variability for either group. TTA exhibited greater mean MOS (p < 0.050; Fig. 2A) and MOS variability (p < 0.050; Fig. 2B) than AB during PLAT. No significant differences in mean MOS and MOS variability values were found between TTA and AB during NOP and VIS.

Figure 2.

(A) Mean minimum mediolateral MOS and (B) within-subject variability of MOS are shown for both AB and TTA. Data is shown at each of the three conditions (NOP, PLAT, VIS). The ‘○’ points represent the left leg for the controls and the intact limb for the amputees. The ‘×’ points represent the right leg for the controls and the prosthetic limb for the amputees. Error bars represent between-subject standard error. ‘*’ indicate significant (p < 0.05) differences from NOP. ‘#’ indicate significant differences between limbs. ‘+’ indicate significant differences between groups.

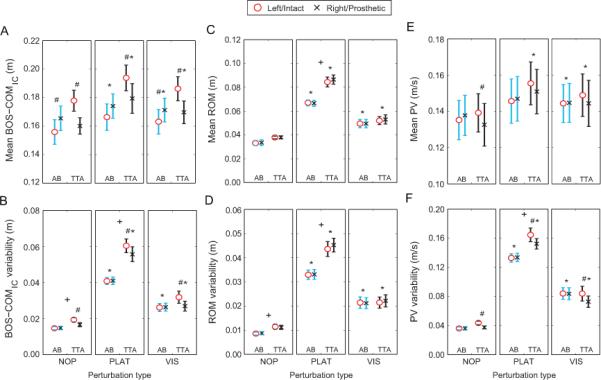

Mean BOS-COMIC (Fig. 3A) and BOS-COMIC variability (Fig. 3B) for both AB and TTA were greater during VIS and PLAT than NOP (p < 0.050). TTA exhibited greater mean BOS-COMIC and BOS-COMIC variability when they stepped on their intact limb than their prosthetic limb for all conditions (p < 0.010; Fig. 3A-B). AB exhibited significantly greater mean BOS-COMIC distance when stepping on the right leg than on the left leg during NOP (p < 0.05; Fig. 3A). Mean BOS-COMIC values between right and left legs in AB were marginally significant during PLAT (p = 0.052; Fig. 3A). No differences in variability were found between left and right limbs in AB. Finally, variability of BOS-COMIC was greater in TTA than AB during NOP and PLAT (p < 0.05; Fig. 3B).

Figure 3.

Mediolateral COM motion. (A) Mean and (B) within-subject variability of the distance between the COM and BOS at initial contact. (C) Mean and (D) within-subject variability of the COM range of motion (ROM) during stance. (E) Mean and (F) within-subject variability of the peak velocity of the COM during stance. Data is shown at each of the three conditions (NOP, PLAT, VIS). The ‘○’ points represent the left leg for the controls and the intact limb for the amputees. The ‘×’ points represent the right leg for the controls and the prosthetic limb for the amputees. Error bars represent between-subject standard error. ‘*’ indicate significant (p < 0.05) differences from NOP. ‘#’ indicate significant differences between limbs. ‘+’ indicate significant differences between groups.

Mean ROM and ROM variability for both AB and TTA were greater during VIS and PLAT than NOP (p < 0.005; Fig. 3C-D). No between-limb differences in mean ROM and ROM variability were found during any of the conditions for either AB or TTA. Mean ROM was greater for TTA than for AB during the PLAT condition (p < 0.005; Fig. 3C) and ROM variability was greater for TTA than for AB during NOP and PLAT (p < 0.05; Fig. 3D).

Mean PV for TTA was greater during PLAT and VIS than NOP (p < 0.05; Fig. 3E). Mean PV for AB was greater during VIS than NOP (p < 0.05; Fig. 3E). Both groups exhibited greater PV variability during PLAT and VIS than NOP (p < 0.001; Fig 3F). TTA exhibited greater mean PV when they stepped with the intact leg than with the prosthetic leg during NOP (p < 0.05; Fig. 3E) and PV variability was greater on the intact side for all conditions (p < 0.005; Fig. 3F). No between-limb differences were found in mean PV or PV variability for AB during any condition. Finally, TTA exhibited greater PV variability than AB during PLAT (p < 0.05; Fig. 3F). No between-group differences in mean PV were found for any condition.

Discussion

This study quantified MOS as well as sub-components of MOS in young individuals with traumatic unilateral transtibial amputation and young able-bodied individuals as they responded to continuous mediolateral oscillations of the platform and visual field. As expected, both platform and visual oscillations increased MOS variability for both groups. However, mean MOS in able-bodied individuals were only significantly greater in VIS than NOP, whereas individuals with transtibial amputation exhibited increased mean MOS during both perturbation conditions. No between-group differences were found for mean MOS and MOS variability during unperturbed and visually perturbed walking. However, individuals with transtibial amputation exhibited greater mean MOS and MOS variability than able-bodied individuals during mediolateral platform oscillations. This suggested that these individuals with traumatic transtibial amputation were less mediolaterally stable than able-bodied individuals when mechanically perturbed, possibly due to lack of active ankle control and distal sensation. Finally, individuals with transtibial amputation exhibited significantly greater values than able-bodied individuals for BOS-COMIC variability, mean and variability of ROM, and variability of PV during the support-surface oscillations. These results suggest that these individuals with transtibial amputation controlled foot placement and COM movement differently than able-bodied individuals in response to the applied perturbations.

Partially in accordance with the hypothesis, mean MOS and MOS variability increased for individuals with transtibial amputation during both platform and visual perturbations, but only visual oscillations caused increases in both mean and variability of MOS in able-bodied individuals. Continuous pseudorandom mediolateral perturbations have caused both mean and variability of mediolateral MOS to increase in able-bodied individuals (McAndrew Young et al., 2012). Using the initial rationale behind the development of the MOS measure, increased mean MOS could be interpreted as being more stable (Hof et al., 2005). This interpretation is, however, at odds with early findings that individuals who are at an increased risk of falling (Hof et al., 2007) or who experience challenges to stability (McAndrew Young et al., 2012) demonstrate increased mean MOS values. Conversely, it is plausible the average of MOS values over many steps reveals a compensation to reduce fall risk. Increased variability likely indicates an increased number of steps with small or negative MOS and associated corrective steps (McAndrew Young et al., 2012). As stated by Gates et al. (2013), MOS variability “may reveal how well controlled this parameter is under different conditions”.

Continuous perturbations also caused nearly all measures of MOS sub-components (i.e. mean and variability of BOS-COMIC, ROM, and PV) to increase for both able-bodied individuals and individuals with transtibial amputation. Both groups likely experienced increased demand for control of foot placement and COM movement to increase margins of stability when walking in destabilizing environments. This supports the idea that continuous mediolateral oscillations challenge walking stability. However, the relative functional importance of any specific sub-component measure to MOS is difficult to determine. It should be noted that no subjects fell, therefore all subjects recovered from any steps with small or negative MOS.

Able-bodied individuals exhibited greater mean MOS on their right leg than on their left leg. This result is consistent with previous findings of asymmetry in able-bodied individuals (Rosenblatt and Grabiner, 2010; McAndrew Young et al., 2012). Greater mean MOS, paired with equal variability, may suggest greater lateral stability in the right leg for the able-body group. The only apparent between-limb differences in the MOS sub-components for the able-bodied individuals were in mean BOS-COMIC. Increased step width has been shown to increase mean MOS (Hak et al., 2012; McAndrew Young and Dingwell, 2012; McAndrew Young et al., 2012). Therefore BOS-COMIC, which like step width is evident of foot placement, likely contributed the most to the asymmetry in mean MOS.

Contrary to our expectations and the results of previously studies (Hof et al., 2007; Gates et al., 2013), individuals with transtibial amputation did not exhibit any between-limb differences in mean MOS or MOS variability. There were, however, significant between-limb differences in MOS sub-components. Mean BOS-COMIC and BOS-COMIC variability values were consistently greater when individuals with transtibial amputation stepped onto their intact limb. These differences may depict the dependence on the “stepping strategy” for foot placement adjustment in the prosthetic leg and the ability of the intact leg to make further foot placement adjustments via the “ankle strategy” (Hof et al., 2010). Between limb differences were also observed in mean PV during the NOP condition and PV variability for all conditions. Due to the fact that between-limb values for mean PV were generally similar, the increased variability on the intact limb may suggest increased difficulty of controlling COM velocity with most adaptations occurring on that side. Overall, these between-limb differences, which are apparent in more MOS sub-component measures for individuals with transtibial amputation than for able-bodied individuals, may somehow interact to provide the symmetrical MOS values observed in individuals with transtibial amputation.

Based on MOS, individuals with traumatic transtibial amputation were less stable than their able-bodied counterparts during mechanically perturbed walking. Between-group differences were also found in the sub-components of MOS during platform oscillations. Mean ROM, ROM variability, BOS-COMIC variability, and PV variability were greater in individuals with traumatic unilateral transtibial amputation than able-bodied individuals. ROM results suggest that although foot placement is the dominant manipulator of MOS, individuals with transtibial amptutation experienced a greater need or difficulty of controlling COM motion than the able-bodied individuals. This notion is further supported by the increased variability of COM peak velocity in individuals with transtibial amputation. Furthermore, the between-group differences in BOS-COMIC variability, much like the increases in variability of ROM and PV, may suggest increased difficulty in controlling the lateral distance between BOS and COM. Since between-group differences in values for sub-component variability were most apparent during the support-surface oscillations, mechanical perturbations appear to have demanded more active control of foot placement and COM movement for individuals with transtibial amputation. Given the mechanical changes in locomotion from transtibial amputation, the findings of this study are in accordance with the notion that lower-limb amputation affects an individual's ability to respond to challenges presented in mechanical form.

Despite impairment, individuals with traumatic transtibial amputation were not, on average, less stable than able-bodied individuals when walking unperturbed or with visual perturbations as determined by mean MOS and MOS variability. Furthermore, the lack of between-group differences in mean MOS and MOS variability during visual perturbations challenges the notion that individuals with transtibial amputation may be more responsive or reliant on visual perturbations due to disrupted somatosensory feedback and increased reliance on visual field information.

It should be noted that these individuals with traumatic transtibial amputation were all otherwise young, healthy, and active. This differs from most lower-limb amputation studies, where results were based on substantially older subjects (Miller et al., 2001; Gooday and Hunter, 2004; Miller and Deathe, 2004; Parker et al., 2013). The young age and relatively high activity level of this group of individuals with transtibial amputation may explain the lack of between-group differences in stability measures during unperturbed walking and visually perturbed walking. Therefore, these results may not extrapolate to other sub-groups of individuals with lower-limb amputation such as older individuals with amputation of vascular etiology.

Acknowledgements

Support was provided by NIH grant 5R01HD059844.

This project was supported by NIH Grant R01-HD059844.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

The views expressed herein are those of the authors and do not reflect the official policy or position of Brooke Army Medical Center, the U.S. Army Medical Department, the U.S. Army Office of the Surgeon General, the Department of the Army, Department of Defense or the U.S. Government.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest associated with this work.

References

- Bardy BG, Warren WH, Kay BA. Motion parallax is used to control postural sway during walking. Experimental Brain Research. 1996;111(2):271–282. doi: 10.1007/BF00227304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauby CE, Kuo AD. Active control of lateral balance in human walking. Journal of Biomechanics. 2000;33(11):1433–40. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9290(00)00101-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dean JC, Alexander NB, Kuo AD. The effect of lateral stabilization on walking in young and old adults. IEEE Trans Biomed Eng. 2007;54(11):1919–26. doi: 10.1109/TBME.2007.901031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dingwell JB, Kang HG, Marin LC. The effects of sensory loss and walking speed on the orbital dynamic stability of human walking. Journal of Biomechanics. 2007;40(8):1723–1730. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2006.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dingwell JB, Marin LC. Kinematic variability and local dynamic stability of upper body motions when walking at different speeds. Journal of Biomechanics. 2006;39(3):444–452. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2004.12.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gates DH, Scott SJ, Wilken JM, Dingwell JB. Frontal plane dynamic margins of stability in individuals with and without transtibial amputation walking on a loose rock surface. Gait and Posture. 2013 doi: 10.1016/j.gaitpost.2013.01.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gooday HM, Hunter J. Preventing falls and stump injuries in lower limb amputees during inpatient rehabilitation: Completion of the audit cycle. Clin Rehabil. 2004;18(4):379–90. doi: 10.1191/0269215504cr738oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hak L, Houdijk H, Steenbrink F, Mert A, van der Wurff P, Beek PJ, van Dieen JH. Speeding up or slowing down?: Gait adaptations to preserve gait stability in response to balance perturbations. Gait and Posture. 2012;36(2):260–4. doi: 10.1016/j.gaitpost.2012.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hak L, Houdijk H, Steenbrink F, Mert A, van der Wurff P, Beek PJ, van Dieen JH. Stepping strategies for regulating gait adaptability and stability. Journal of Biomechanics. 2013 doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2012.12.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hof AL. The ‘extrapolated center of mass’ concept suggests a simple control of balance in walking. Human Movement Science. 2008;27(1):112–125. doi: 10.1016/j.humov.2007.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hof AL, Gazendam MG, Sinke WE. J Biomech. 2005;The condition for dynamic stability.38(1):1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2004.03.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hof AL, van Bockel RM, Schoppen T, Postema K. Control of lateral balance in walking. Experimental findings in normal subjects and above-knee amputees. Gait & Posture. 2007;25(2):250–8. doi: 10.1016/j.gaitpost.2006.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hof AL, Vermerris SM, Gjaltema WA. Balance responses to lateral perturbations in human treadmill walking. The Journal of Experimental Biology. 2010;213(15):2655–2664. doi: 10.1242/jeb.042572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuo AD. Stabilization of lateral motion in passive dynamic walking. The International Journal of Robotics Research. 1999;18(9):917–930. [Google Scholar]

- Maclellan MJ, Patla AE. Adaptations of walking pattern on a compliant surface to regulate dynamic stability. Exp Brain Res. 2006 doi: 10.1007/s00221-006-0399-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacLellan MJ, Patla AE. Stepping over an obstacle on a compliant travel surface reveals adaptive and maladaptive changes in locomotion patterns. Exp Brain Res. 2006;173(3):531–8. doi: 10.1007/s00221-006-0398-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Massen CH, Kodde L. A model for the description of left-right stabilograms. Agressologie. 1979;20:107–108. [Google Scholar]

- McAndrew PM, Dingwell JB, Wilken JM. Walking variability during continuous pseudo-random oscillations of the support surface and visual field. Journal of Biomechanics. 2010;43(8):1470–5. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2010.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McAndrew PM, Wilken JM, Dingwell JB. Dynamic stability of human walking in visually and mechanically destabilizing environments. Journal of Biomechanics. 2011;44(4):644–649. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2010.11.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McAndrew Young PM, Dingwell JB. Voluntary changes in step width and step length during human walking affect dynamic margins of stability. Gait &; Posture. 2012;36(2):219–224. doi: 10.1016/j.gaitpost.2012.02.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McAndrew Young PM, Wilken JM, Dingwell JB. Dynamic margins of stability during human walking in destabilizing environments. Journal of Biomechanics. 2012;45(6):1053–1059. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2011.12.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller WC, Deathe AB. A prospective study examining balance confidence among individuals with lower limb amputation. Disabil Rehabil. 2004;26(14-15):875–81. doi: 10.1080/09638280410001708887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller WC, Speechley M, Deathe B. The prevalence and risk factors of falling and fear of falling among lower extremity amputees. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. 2001;82(8):1031–7. doi: 10.1053/apmr.2001.24295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niino N, Tsuzuku S, Ando F, Shimokata H. Frequencies and circumstances of falls in the national institute for longevity sciences, longitudinal study of aging (nils-lsa). Journal of Epidemiology. 2000;10(1 Suppl.):S90–S94. doi: 10.2188/jea.10.1sup_90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Connor SM, Kuo AD. Direction-dependent control of balance during walking and standing. Journal of Neurophysiology. 2009;102(3):1411–9. doi: 10.1152/jn.00131.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker K, Hanada E, Adderson J. Gait variability and regularity of people with transtibial amputations. Gait and Posture. 2013;37(2):269–273. doi: 10.1016/j.gaitpost.2012.07.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pauley T, Devlin M, Heslin K. Falls sustained during inpatient rehabilitation after lower limb amputation: Prevalence and predictors. American Journal of Physical Medicine & Rehabilitation. 2006;85(6):521–32. doi: 10.1097/01.phm.0000219119.58965.8c. quiz, 533-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenblatt NJ, Grabiner MD. Measures of frontal plane stability during treadmill and overground walking. Gait & Posture. 2010;31(3):380–4. doi: 10.1016/j.gaitpost.2010.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinitksi EH, Terry K, Wilken JM, Dingwell JB. Effects of perturbation magnitude on dynamic stability when walking in destabilizing environments. Journal of Biomechanics. 2012;45(12):2084–2091. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2012.05.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terry K, Sinitski EH, Dingwell JB, Wilken JM. Amplitude effects of medio-lateral mechanical and visual perturbations on gait. Journal of Biomechanics. 2012;45(11):1979–1986. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2012.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tinetti ME, Doucette J, Claus E, Marottoli R. The contribution of predisposing and situational risk factors to serious fall injuries. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 1995;43(11):1207–1213. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1995.tb07395.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viton JM, Mouchnino L, Mille ML, Cincera M, Delarque A, Pedotti A, Bardot A, Massion J. Equilibrium and movement control strategies in trans-tibial amputees. Prosthet Orthot Int. 2000;24(2):108–16. doi: 10.1080/03093640008726533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warren WH, Kay BA, Yilmaz EH. Visual control of posture during walking: Functional specificity. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance. 1996;22(4):818–838. doi: 10.1037//0096-1523.22.4.818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilken JM, Rodriguez KM, Brawner M, Darter BJ. Reliability and minimal detectible change values for gait kinematics and kinetics in healthy adults. Gait Posture. 2012;35(2):301–7. doi: 10.1016/j.gaitpost.2011.09.105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]