Abstract

The enzymes responsible for peptidoglycan amidation in Staphylococcus aureus, MurT and GatD, were recently identified and shown to be required for optimal expression of resistance to beta-lactams, bacterial growth, and resistance to lysozyme. In this study, we analyzed the impact of peptidoglycan amidation in representative strains of the most widespread clones of methicillin resistant S. aureus (MRSA). The inhibition of the expression of murT-gatD operon resulted in different phenotypes of resistance to beta-lactams and lysozyme according to the different genetic backgrounds. Further, clonal lineages CC1 and CC398 (community-acquired MRSA [CA-MRSA]) showed a stronger dependency on MurT-GatD for resistance to beta-lactams, when compared to the impact of the impairment of the cell wall step catalyzed by MurF. In the remaining backgrounds similar phenotypes of beta-lactam resistance were observed upon the impairment of both cell-wall-related genes. Therefore, for CA-related backgrounds, the predominant beta-lactam resistance mechanism seems to involve genes associated with secondary modifications of peptidoglycan. On the other hand, the lack of glutamic acid amidation had a more substantial impact on lysozyme resistance for cells of CA-MRSA backgrounds, than for hospital-acquired MRSA (HA-MRSA). However, no significant differences were found in the resistance level of the respective peptidoglycan structure, suggesting that the lysozyme resistance mechanism involves other factors. Taken together, these results suggested that the different genetic lineages of MRSA were able to develop different molecular strategies to overcome the selective pressures experienced during evolution.

Introduction

Methicillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) are a major cause of nosocomial infections worldwide15,18,24,27 and most cases of hospital-acquired MRSA (HA-MRSA) infections are caused by a few successful multidrug-resistant epidemic clones.38

In the last two decades, the emergence of community-acquired MRSA (CA-MRSA), causing infections among healthy individuals, has been a subject of growing concern.6,7,20,33 Nevertheless, nowadays, the recent changes in the epidemiology of CA-MRSA suggest that the boundaries between the hospital and community are blurring.21,29,30,50

Several studies have demonstrated that genetic backgrounds associated with CA-MRSA have a number of features that distinguish them from HA-MRSA. CA-MRSA typically have increased virulence and carry the smaller and easier to transfer staphylococcal chromosomal cassette (SCCmec) type IV and V.12 Interestingly, the largest SCCmec type II, usually found in HA-MRSA, has a significant fitness cost for the bacteria, resulting in a decrease in the growth rate, and in a reduction of toxin expression levels.9,10 The balance between the virulence and antibiotic resistance costs may explain why MRSA with SCCmec type II are found mainly in hospital environments where high antibiotic pressure, immunocompromised individuals, and vector-mediated transmission are present.10 Moreover, for CA-MRSA strains, in contrast to HA-MRSA, mecA was suggested not to be the primary determinant of methicillin resistance, being the expression of pbp4 the main determinant of resistance.32

Recently, a small operon, encoding the enzymatic complex MurT-GatD, was identified to be responsible for a secondary modification of peptidoglycan in S. aureus, the amidation of glutamic acid in the stem peptides.17,34 Inhibition of amidation caused reduced growth rate; reduced resistance to beta-lactam antibiotics, shown previously to be affected by auxiliary genes14; and increased sensitivity to lysozyme in HA-MRSA strain COL.17

In this communication we report that peptidoglycan amidation has different impacts in the expression of resistance to beta-lactams and to lysozyme, depending on the genetic background of the particular strain. These observations suggest that S. aureus, from different genetic lineages, include different elements from their core genomes in the strategies of resistance to beta-lactam and lysozyme adopted.

Materials and Methods

Bacterial strains and growth conditions

The 11 MRSA strains analyzed in this study are listed in Table 1. The respective mutants with murT-gatD and murF conditional mutations are listed in Table 2. S. aureus strains were grown at 37°C with aeration in tryptic soy broth (TSB; Difco Laboratories) or tryptic soy agar (TSA; Difco Laboratories). The strains with murT-gatD and murF conditional mutations were grown in the presence of kanamycin (50 μg/ml; Sigma) and neomycin sulfate (50 μg/ml; Sigma). Growth medium was supplemented with the appropriate concentration of cadmium chloride (CdCl2; Sigma), unless otherwise described.

Table 1.

Methicillin Resistant Staphylococcus aureus Strains Used in This Study

| Strain | SCCmec type | HA/CA-MRSA | MLST (ST) | Clone | CC | Year of isolation | Country of origin | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| COL | I | HA-MRSA | ST250 | Archaic | CC8 | 1965 | United Kingdom | 39 |

| HDES57 | IV | HA-MRSA | ST22 | EMRSA15 | CC22 | 2007 | Portugal | 11 |

| HDE288 | VI | HA-MRSA | ST5 | Pediatric | CC5 | 1996 | Portugal | 47 |

| HUR75 | III | HA-MRSA | ST239 | Brazilian | CC8 | 1998 | Hungary | 40 |

| HUC599 | II | HA-MRSA | ST5 | NY/Japan | CC5 | 2006 | Portugal | 1 |

| DEN2294 | IV | CA-MRSA | ST30 | Southwest-Pacific | CC30 | 2001 | Denmark | 16 |

| ST398 | V | CA-MRSA | ST398 | ST398 | CC398 | 2005 | France | 2 |

| USA400 | IV | CA-MRSA | ST1 | USA400 | CC1 | 1995–2003 | United States | 31 |

| MW2 | IV | CA-MRSA | ST1 | USA400 | CC1 | 1998 | United States | 6 |

| WIS | V | CA-MRSA | ST59 | Taiwan | CC59 | 1999 | Australia | 37 |

| C377 | IV | CA-MRSA | ST8 | USA300 | CC8 | 2005 | Spain | 46 |

CA-MRSA, community-acquired methicillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus; CC, clonal complex; HA-MRSA, hospital-acquired methicillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus; SCCmec, staphylococcal chromosomal cassette; ST, sequence type.

Table 2.

Mutant Strains and Plasmids Used in This Study

| Strains | Relevant characteristics | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| S. aureus | ||

| RN4220 | Mcs; restriction negative | 36 |

| M100 | Mcr laboratory step mutant | 51 |

| M100pCadmurT-gatD | M100 with murT-gatD operon under Pcad control, Kanr, Neor | This study |

| M100pCadmurF | M100 with murF gene under Pcad control, Kanr, Neor | This study |

| COLpCadmurT-gatD | COL with murT-gatD operon under Pcad control, Kanr, Neor | 17 |

| COLpCadmurF | COL with murF gene under Pcad control, Kanr, Neor | This study |

| HUR75pCadmurT-gatD | HUR75 with murT-gatD operon under Pcad control, Kanr, Neor | This study |

| HUR75pCadmurF | HUR75 with murF gene under Pcad control, Kanr, Neor | This study |

| HDES57pCadmurT-gatD | HDES57 with murT-gatD operon under Pcad control, Kanr, Neor | This study |

| HDES57pCadmurF | HDES57 with murF gene under Pcad control, Kanr, Neor | This study |

| HAR22pCadmurT-gatD | HAR22 with murT-gatD operon under Pcad control, Kanr, Neor | This study |

| HAR22pCadmurF | HAR22 with murF gene under Pcad control, Kanr, Neor | This study |

| HUC599pCadmurT-gatD | HUC599 with murT-gatD operon under Pcad control, Kanr, Neor | This study |

| HUC599pCadmurF | HUC599 with murF gene under Pcad control, Kanr, Neor | This study |

| HDE288pCadmurT-gatD | HDE288 with murT-gatD operon under Pcad control, Kanr, Neor | This study |

| HDE288pCadmurF | HDE288 with murF gene under Pcad control, Kanr, Neor | This study |

| MW2pCadmurT-gatD | MW2 with murT-gatD operon under Pcad control, Kanr, Neor | This study |

| MW2pCadmurF | MW2 with murF gene under Pcad control, Kanr, Neor | This study |

| USA400pCadmurT-gatD | USA400 with murT-gatD operon under Pcad control, Kanr, Neor | This study |

| USA400pCadmurF | USA400 with murF gene under Pcad control, Kanr, Neor | This study |

| ST398pCadmurT-gatD | ST398 with murT-gatD operon under Pcad control, Kanr, Neor | This study |

| ST398pCadmurF | ST398 with murF gene under Pcad control, Kanr, Neor | This study |

| WISpCadmurT-gatD | WIS with murT-gatD operon under Pcad control, Kanr, Neor | This study |

| WISpCadmurF | WIS with murF gene under Pcad control, Kanr, Neor | This study |

| C377pCadmurT-gatD | C377 with murT-gatD operon under Pcad control, Kanr, Neor | This study |

| C377pCadmurF | C377 with murF gene under Pcad control, Kanr, Neor | This study |

| DEN2294pCadmurT-gatD | DEN2294 with murT-gatD operon under Pcad control, Kanr, Neor | This study |

| DEN2294pCadmurF | DEN2294 with murF gene under Pcad control, Kanr, Neor | This study |

| Escherichia coli | ||

| DH5α | recA endA1 gyrA96 thi-1 hsdR17 supE44 relA1 F80 DlacZDM15 | Invitrogen |

| Plasmids | ||

| pBCB20 | S. aureus integrative vector including Pcad inducible promotor, Apr, Kanr | R.G. Sobral and M.G. Pinho, unpublished |

| pMurT′ | pBCB20 vector with murT ribosome-binding site and the first 298 codons fused to Pcad promotor; Apr, Kanr | 17 |

| pMurF′ | pBCB20 vector with murF ribosome-binding site and the first 256 codons fused Pcad promotor; Apr, Kanr | This study |

ApR, ampicillin resistant; KanR, kanamycin resistant; Mcs, methicillin susceptible; Mcr, methicillin resistant; NeoR, neomycin resistant.

Construction of murT-gatD conditional mutants

The murT-gatD conditional mutation17 was transduced, by phage 80α into the recipient strains (Table 1), as previously described,41 generating the murT-gatD conditional mutants in different backgrounds (Table 2).

Construction of murF conditional mutants

A 768-bp DNA fragment of the 5′ end of murF gene, including the ribosome binding site but not the promoter sequence, was amplified using chromosomal DNA from strain COL as template and the specific primers PmurF′-R and PmurF′-F (Supplementary Table S1; Supplementary Data are available online at www.liebertpub.com/mdr). The amplified murF fragment and plasmid pBCB20 (R.G. Sobral and M.G. Pinho, unpublished data), carrying a CdCl2 inducible promoter, were digested with SmaI (New England Biolabs) and ligated, generating plasmid pMurF′. Plasmid pMurF′ was electroporated into competent cells of RN4220 with a Gene Pulser apparatus (Bio-Rad). The correct insertion of pMurF′ into RN4220 chromosome was confirmed by polymerase chain reaction, using an internal murF primer chosen downstream of the cloned region (PmurFdn) and an internal primer to pCad conditional promoter (Pcad-F) (Supplementary Table S1). The murF conditional mutation was then transduced, by phage 80α into the recipient strains (Table 1), as previously described,41 generating the murF conditional mutants in different backgrounds (Table 2).

Pulsed-field gel electrophoresis

The correct insertion of murT–gatD and murF conditional mutations into the chromosome of the recipient strains was performed by comparing the pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) profiles of the parental strains and the respective transductants. DNA agarose disks of the parental strain and the respective mutant were prepared, digested with SmaI, and separated as described.8

Southern blot analysis

SmaI chromosomal fragments, from the parental strain and the respective murF and murT-gatD mutants, were transferred to nylon membranes (Hybond N+; GE Healthcare) that were subsequently hybridized with specific DNA probes labeled with the ECL direct labeling system (GE Healthcare). The DNA probes used for murT-gatD and murF genes were amplified with primer pairs PmurT-D1+PmurT-R1 and PmurF′-R+PmurF′-F, respectively (Supplementary Table S1).

Population analysis profile

Overnight-grown cultures of the parental strains and the respective murT-gatD and murF conditional strains were plated at various dilutions on TSA plates, with increasing concentrations of oxacillin (0, 0.75, 1.5, 3, 6.25, 12.5, 25, 50, 100, 200, 400, and 800 μg/ml), and colonies were counted after incubation at 30°C for 48 hours, as previously described.13

Peptidoglycan isolation for lysozyme lytic assays

Isolation of cell wall was performed as described previously.3 Briefly, cells were harvested by centrifugation, washed twice with cold 0.9% NaCl, and boiled for 20 minutes. After chilling, the cells were washed twice and disrupted using 106-mm glass beads (Sigma) and FastPrep FP120 apparatus (Bio 101). The suspension was then washed, and boiled for 30 minutes in 5% sodium dodecyl sulfate and 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7), to remove noncovalently bound proteins. After centrifugation, the cell wall fragments were diluted in 0.1 M Tris-HCl (pH 6.8) and incubated with 0.5 mg/ml trypsin for 16 hours at 37°C to degrade cell-bound proteins. Purified cell walls were washed with water and lyophilized and treated with 49% hydrofluoric acid for 48 hours at 4°C, to remove teichoic acids. The purified peptidoglycan was washed with water and lyophilized.

Turbidometric assay of peptidoglycan hydrolysis

To analyze the susceptibility of peptidoglycan to lysozyme hydrolysis, a turbidometric assay was performed as described previously.3,17,19 Briefly, purified peptidoglycan was sonicated in 100 mM sodium-potassium phosphate buffer (pH 6.6). Egg white lysozyme (Sigma) was added (300 μg/ml) and the reaction was incubated at 37°C. The optical density was monitored at 595 nm in 96-well microplates (pure grade, Brand) using a microplate reader (Infinite F200 Pro; Tecan).

Determination of lysozyme resistance of S. aureus growing cells

The impact of lysozyme on exponentially growing cultures was determined as described previously.17,19 Overnight cultures of the conditional mutants, grown with inducer, were inoculated into fresh TSB, with and without inducer. The cultures were incubated at 37°C to an OD620nm of 1.0. Then, each culture was diluted 1:10 into fresh TSB, with and without inducer, and lysozyme (300 μg/ml) was added as the OD620nm reached 1.0. The growth was monitored for several hours.

Statistical analysis

A two-tailed Student's t test with Welch correction was used to determine the significance of differences in lysozyme digestion within groups of CA-MRSA and HA-MRSA. Differences were considered statistically significant when p was<0.005. The Graph Pad Prism 5.0 package was used.

Results

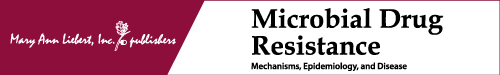

The impact of the impairment of peptidoglycan amidation on oxacillin resistance was previously demonstrated by the construction and characterization of the murT-gatD conditional mutation in strain COL. This mutation was shown to impact not only beta-lactam resistance, but also growth rate and lysozyme resistance.17 In this study, we first observed that the effects of murT-gatD inhibition in the resistance level of strain COL and strain MW2 were clearly distinct, as observed through oxacillin inhibition halos (1-mg disc) (Supplementary Fig. S1). The decrease in the resistance level of the strain was significantly more pronounced for MW2pCadmurT-gatD, showing a twofold wider inhibition halo. To test that this behavior was the result of different genetic backgrounds and not a strain-specific trait, the mutation was transferred to another strain of the same clone USA400 and a similar resistance profile was obtained (Fig. 1A). These results led to the hypothesis that murT-gatD expression and/or the enzymatic step catalyzed by the MurT-GatD complex could have different physiological consequences depending on the genetic background.

FIG. 1.

Impact of murT-gatD and murF conditional mutations on the oxacillin resistance profiles of MW2, USA400, WIS, ST398, COL, HUR75, and HDES57 strains. Overnight cultures of the parental strains and conditional mutants grown with CdCl2 inducer were plated on TSA containing increasing concentrations of oxacillin. Plates were incubated for 48 hours at 30°C. (■) Oxacillin population analysis profile of parental strains; (○) oxacillin population analysis profile of murT-gatD conditional mutants; ( ) oxacillin population analysis profile of murF conditional mutants. Oxacillin population analysis profile of (A) CA-MRSA strains and (B) HA-MRSA strains. CA-MRSA, community-acquired methicillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus; CdCl2, cadmium chloride; HA-MRSA, hospital-acquired MRSA; TSA, tryptic soy agar.

) oxacillin population analysis profile of murF conditional mutants. Oxacillin population analysis profile of (A) CA-MRSA strains and (B) HA-MRSA strains. CA-MRSA, community-acquired methicillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus; CdCl2, cadmium chloride; HA-MRSA, hospital-acquired MRSA; TSA, tryptic soy agar.

To address this hypothesis, the murT-gatD conditional mutation was transduced to representative strains of the most widespread MRSA clones, among both HA-MRSA and CA-MRSA (Table 1).

The correct transfer of the mutation was determined by comparing the SmaI PFGE profiles of the parental strains and the respective transductants (Supplementary Fig. S2). In addition, Southern blot analysis using specific probes for murT-gatD genes confirmed the correct insertion of the conditional mutation.

Impact of murT-gatD conditional mutation on resistance to beta-lactam antibiotics in different MRSA genetic backgrounds

The impact of murT-gatD conditional mutation on the beta-lactam resistance level of the different MRSA strains was evaluated by performing oxacillin population analysis profiles.

The most striking observation was that MW2/USA400, ST398, and WIS CA-MRSA murT-gatD conditional mutants (Fig. 1A) grown in the absence of inducer were overall less resistant to oxacillin, when compared with the HA-MRSA mutant strains (Fig. 1B). A first early drop in the number of cfu/ml, occurring at 0.75 μg/ml, was common to all analyzed mutant strains, followed by a high frequency of resistant subpopulations, able to grow on higher concentrations of antibiotic. Strikingly, while for the HA-MRSA (COL, HUR75, and HDES57) the subpopulations of the mutants were able to grow on antibiotic concentrations near the MIC (minimal inhibitory concentration) of the parental strain (from 50 to 800 μg/ml, Fig. 1B), for the CA-MRSA (MW2, USA400, ST398, and WIS), the mutants' subpopulations only grew at low antibiotic concentrations (from 0.75 to 6.25 μg/ml, Fig. 1A). Consequently, complete growth inhibition occurred at much lower antibiotic concentrations for murT-gatD mutants of CA-MRSA backgrounds (Fig. 1A).

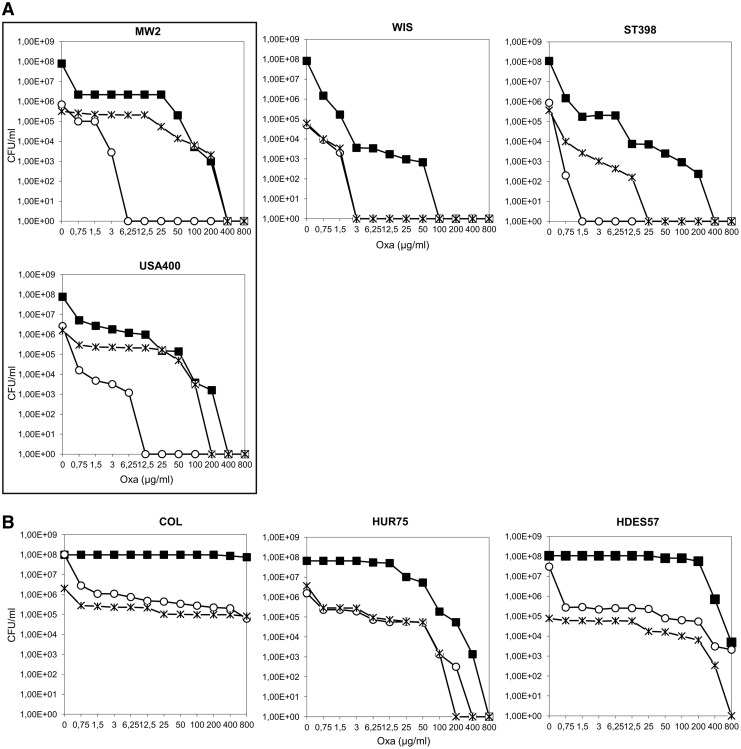

Within the CA-MRSA strains, C377pCadmurT-gatD and DEN2294pCadmurT-gatD showed a less striking decrease in resistance to oxacillin (Fig. 2A), with subpopulations that were able to grow up to 100 μg/ml. In fact, C377pCadmurT-gatD showed an overall resistance profile similar to HUR75pcadmurT-gatD (Figs. 2A and 1B, respectively). The similarities between these resistance profiles were consistent with the fact that HUR75 and C377 are genetically related, belonging to the same clonal complex (CC8).

FIG. 2.

Impact of murT-gatD and murF conditional mutations on the oxacillin resistance profiles of C377, DEN2294, HUC599, and HDE288 strains. Overnight cultures of the parental strains and conditional mutants, grown with CdCl2 inducer, were plated on TSA containing increasing concentrations of oxacillin. Plates were incubated for 48 hours at 30°C. (■) Oxacillin population analysis profile of parental strains; (○) oxacillin population analysis profile of murT-gatD conditional mutants; ( ) oxacillin population analysis profile of murF conditional mutants. Oxacillin population analysis profile of (A) CA-MRSA strains and (B) HA-MRSA strains.

) oxacillin population analysis profile of murF conditional mutants. Oxacillin population analysis profile of (A) CA-MRSA strains and (B) HA-MRSA strains.

Likewise, DEN2294 (ST30-IV, Southwest Pacific clone) is genetically related to the HA-MRSA ST36-MRSA-II (EMRSA-16) as they are descendants from the common ancestral ST30-MSSA.45 A conditional murT-gatD mutant was not constructed in the ST36-MRSA-II background, as all the strains available were resistant to the selectable marker of the pMurT′ integrative plasmid (kanamycin).

Regarding the Pediatric and New York/Japan clones (HDE288 and HUC599, respectively) the parental strains exhibited, together with a high frequency of resistant subpopulations, lower MIC values (0.75 μg/ml) than the previously analyzed HA-MRSA strains (50–800 μg/ml, Fig. 2B). Consistently, for these strains, the murT-gatD mutation had a complete inhibitory impact at lower antibiotic concentrations (6.25 and 100 μg/ml for HDE288 and HUC599 mutants, respectively, Fig. 2B), than the remaining HA-MRSA mutants.

To explore whether this behavior is associated with distinct steps of peptidoglycan biosynthesis, the impact of a murF conditional mutation was also studied in the same genetic backgrounds.

Impact of murF conditional mutation on resistance to beta-lactam antibiotics in different MRSA genetic backgrounds

A conditional mutation for murF gene (pCadmurF) was constructed using the same pCad inducible promoter, transduced from RN4220pCadmurF to the strains listed in Table 1, and oxacillin population analysis profiles were performed (Figs. 1 and 2). In the absence of inducer, the murF conditional mutants were impaired in the last biosynthetic cytoplasmic step, catalyzed by MurF protein, the addition of the D-alanyl-D-alanine terminus to the stem peptide.48

For most clonal lineages the level of resistance to oxacillin was similar for murT-gatD and murF mutants (Figs. 1B and 2B). However, for MW2/USA400 and ST398 CA-MRSA strains, all CA-MRSA strains, the inhibition of murT-gatD transcription caused a more pronounced effect on oxacillin resistance, than inhibition of murF transcription (Fig. 1A).

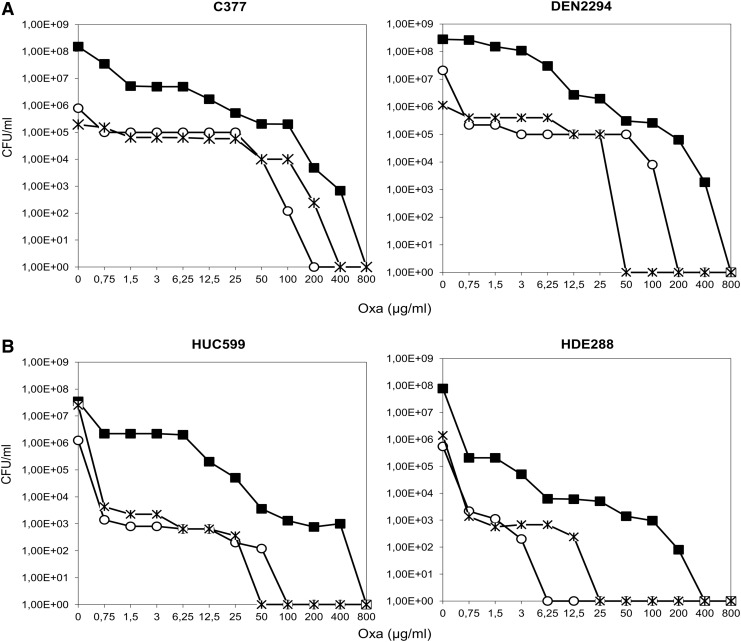

Impact of murT-gatD and murF conditional mutations on beta-lactam resistance in a mecA-negative strain resistant to methicillin

The pCadmurT-gatD and pCadmurF conditional mutations were transduced to the M100 strain (Table 2), a laboratory step mutant selected for methicillin resistance,51 which encodes a modified PBP3,43 and does not contain mecA. The inhibition of murF transcription, in the background of M100 strain, resulted in a decrease in cell viability, shown by a drop in the number of cfu/ml from 108 to 106 (Fig. 3). However, no effect was observed in the oxacillin resistance level. In contrast, the impairment of murT-gatD caused, besides the same decrease in viability, a fourfold decrease in oxacillin resistance; the conditional mutant, grown in the absence of inducer, showed complete growth inhibition at 2 μg/ml of oxacillin, in contrast to the parental strain (8 μg/ml) (Fig. 3).

FIG. 3.

Impact of murT-gatD and murF conditional mutations on the oxacillin resistance profile of mecA-negative M100 strain. Overnight cultures of the parental strain and conditional mutants, grown with CdCl2 inducer, were plated on TSA containing increasing concentrations of oxacillin. Plates were incubated for 48 hours at 30°C. (■) Oxacillin population analysis profile of M100 parental strain; (○) oxacillin population analysis profile of murT-gatD conditional mutant; ( ) oxacillin population analysis profile of murF conditional mutant.

) oxacillin population analysis profile of murF conditional mutant.

Impact of murT-gatD conditional mutation on lysozyme resistance in different MRSA genetic backgrounds

Lysozyme resistance assays in living cells

To evaluate the impact of murT-gatD conditional mutation on S. aureus intrinsic lysozyme resistance, in the several genetic backgrounds, the murT-gatD conditional mutants were grown, in the absence and in the presence of inducer, and treated with muramidase during the exponential phase. The cell density of the cultures was then monitored for several hours.

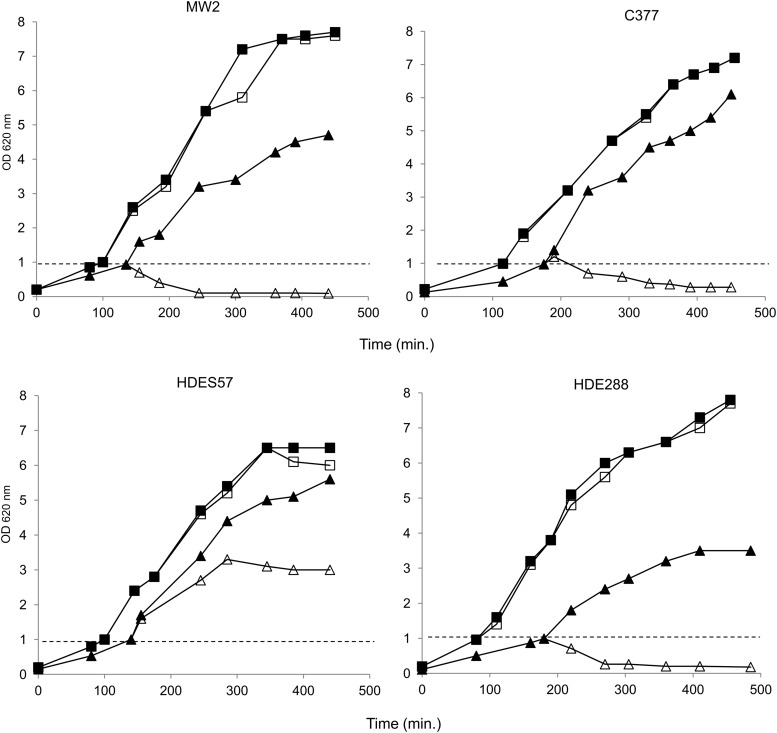

The parental strains, as the conditional mutants grown with inducer, showed no growth alteration upon addition of lysozyme to the medium (shown for HDES57, HDE288, MW2, and C377 strains and for the respective mutants, grown without inducer, Fig. 4; data not shown for the remaining strains), confirming that all these strains are resistant.

FIG. 4.

Impact of murT-gatD conditional mutation on lysozyme resistance in HDES57, HDE288, MW2, and C377 strains and the respective mutants, grown without inducer. Overnight cultures were diluted to OD620nm 0.1 and were incubated at 37°C to OD620nm of 1.0. Then, each culture was diluted into fresh medium and lysozyme (300 μg/ml) was added at OD620nm 1.0, as indicated by the dashed line. Conditional mutant grown without inducer, in the presence (△) and in the absence of lysozyme (▲); parental strain grown in the presence (□) and in the absence of lysozyme (■).

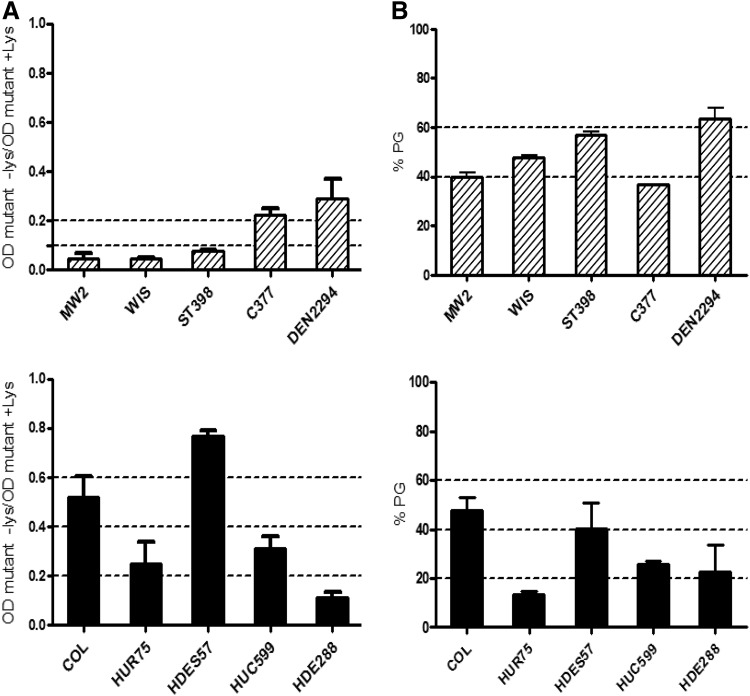

To address the effects of the impairment of murT-gatD transcription on lysozyme resistance level, the cell density values of each mutant culture, grown with and without lysozyme, were compared at 90 minutes after the addition of muramidase (Fig. 5A).

FIG. 5.

Impact of murT-gatD conditional mutation on lysozyme resistance. (A) Effect of lysozyme (300 μg/ml) on the growth rate of the conditional mutants grown without inducer. The impact of lysozyme is represented as the ratio between the optical density of the culture of the mutant grown with lysozyme (+lys) and without lysozyme (−lys), 90 minutes after addition of the muramidase. (B) Effect of lysozyme (300 μg/ml) on purified PG from the conditional mutants grown without inducer. The impact of lysozyme is represented as the percentage of undigested peptidoglycan, 40 minutes after addition of the muramidase. Dashed bars, conditional mutants of CA-MRSA strains; solid bars, conditional mutants of HA-MRSA strains. Also represented are the mean and standard deviation of triplicate experiments. PG, peptidoglycan.

Overall, murT-gatD mutants constructed in CA-MRSA backgrounds were more sensitive to lysozyme, when compared with mutants constructed in HA-MRSA backgrounds. In fact, while all CA-MRSA mutants showed a decrease in optical density above 70% (mean value of 86.1%±9.6%) when grown in the presence of lysozyme, in HA-MRSA the decrease was much more variable, ranging between 23.1% and 90.6% (Fig. 5A). The difference in the mean lysozyme digestion level, between groups of CA-MRSA and HA-MRSA, was statistically significant (p<0.005, Student's t test). Interestingly, mutants DEN2294pCadmurT-gatD and C377pCadmurT-gatD were more resistant to lysozyme, than the remaining CA-MRSA strains, showing again a different behavior, as previously observed for the oxacillin resistance profiles (Figs. 5A and 2A).

Lysozyme resistance assays with purified peptidoglycan

To determine whether the mutant phenotypes, observed in vivo, were directly associated with the lack of amidation of peptidoglycan, or whether they were associated with other strain specificities, the peptidoglycan of the parental strains and the respective mutant, grown without inducer, was isolated and purified. The peptidoglycan concentration was adjusted and after addition of lysozyme, the optical density was monitored to assess the amount of peptidoglycan digested.

The results of the lytic assays showed no statistically significant differences (Student's t test) between the lysozyme resistance of the purified peptidoglycan of the different mutant strains (Fig. 5B).

The comparison between the susceptibility to lysozyme of murT-gatD mutants' living cells and their respective purified peptidoglycan (Fig. 5A, B) showed no correlation. In fact, while cells from CA-MRSA mutants were more susceptible to lysozyme than cells from HA-MRSA mutants, their respective purified peptidoglycan showed no significant variability between the resistance levels.

Discussion

In the last half-century, the cell wall biosynthetic pathway has been extensively studied, namely, for its role as an antimicrobial target. However, the enzymes responsible for the amidation of D-glutamic acid of staphylococcal peptidoglycan were described only recently. Figueiredo et al.17 identified, in MRSA strain COL, the murT-gatD operon whose protein products catalyze the amidation of peptidoglycan and showed that this cell wall modification is important for optimal growth, beta-lactam resistance, and sensitivity to the host defense factor lysozyme. Munch et al.34 demonstrated that both enzymes, MurT and GatD, are essential for survival and interact as a glutamine amidotransferase bi-enzymatic complex.

Several genes of the peptidoglycan biosynthetic pathway, among other housekeeping genes, are involved in the beta-lactam resistance mechanism. In fact, the mechanism of resistance of MRSA strains is not simply mecA-dependent, but also needs the optimal expression of the so-called auxiliary genes4,14,25,35 among which are essential cell-wall-related determinants, such as murE,28 murF,49 pbp2,44 pbp1,42 femABX,5 and murT-gatD operon.17 However, the impact of different steps of peptidoglycan synthesis in beta-lactam resistance of MRSA strains from different genetic backgrounds, was only assessed for PBP4.32 Previously, Katayama et al.23 showed that impairment of pbp4 does not affect the beta-lactam resistance level of MRSA, being not classified as an auxiliary gene. Later, Memmi et al.32 showed that pbp4 is an auxiliary gene in CA-MRSA, being the key player in the resistance mechanism of these specific strains.

In this communication, the murT-gatD conditional mutation was studied in the background of the major contemporary MRSA clones. Different impacts in the oxacillin resistance profile were observed for murT-gatD depletion in several MRSA genetic backgrounds, with a more pronounced effect on CA-MRSA-related backgrounds, when compared with HA-MRSA. The conditional mutants of MW2/USA400, ST398, and WIS strains showed complete growth inhibition at antibiotic concentrations ∼100-fold lower than HA-MRSA mutants. However, this effect was not shared by all CA-MRSA strains; the conditional mutants of C377 and DEN2294, belonging to lineages highly disseminated in community settings (USA300 and Southwest Pacific clones, respectively), showed a less striking decrease in resistance to oxacillin. In the case of C377, this behavior could be explained by the fact that this strain is genetically related with the HA-MRSA HUR75 strain, as they belong to the same clonal complex (CC8). Likewise, DEN2294 CA-MRSA (ST30-IV, Southwest Pacific clone) has a genetic background related to the hospital-acquired ST36-MRSA-II (EMRSA-16) as DEN2294 and ST36-MRSA-II have a common ancestral, ST30-MSSA.22,45

Although the differences in oxacillin resistance decrease observed between the CA- and HA-related strains are clear, the molecular mechanism behind these different phenotypes is probably directly associated rather with the strains' clonal complexes, and therefore, with their genetic background.

An association between the strains' genetic background and their capacity to acquire and maintain a recombinant plasmid expressing mecA was previously observed.22 Strains from clonal complexes CC1 and CC5 were, among the major MRSA lineages tested, the ones that were less efficiently transformed. However, CC5 lineage has been recently described to be well adapted to the hospital environment through the efficient acquisition of resistance to new antibiotics,26 suggesting that strains belonging to CC5 are able to easily acquire mecA, but not able to efficiently maintain it. Therefore, the CC5 lineage seems to be less dependent on the presence of mecA than other major lineages, for the efficient expression of resistance to beta-lactams. One hypothesis is that in strains of CC5 beta-lactam resistance relies on the presence of specific housekeeping genes, namely, murT-gatD, although the presence of mecA would still be essential.

Coincidently, strains belonging to CC1 (MW2/USA400) typically associated with the community onset, and CC5 (HDE288 and HUC599), which includes hospital-related strains, were among the ones that showed higher impact from murT-gatD impairment. The other strains that showed the same level of impact were WIS and ST398 (CC59 and CC398, respectively), which harbor the small SCCmec type V, suggesting that their genetic background would also not favor the stability of mecA expression.

In this line of thought, the clonal complexes CC8, CC22, and CC30, which showed higher efficiency of transformation with mecA and stability of mecA expression,22 were, in our study, represented by the strains showing less impact of murT-gatD impairment (COL, HUR75, C377, HDES57, and DEN2294). Taken together, these observations suggest that the genetic backgrounds less prone to receiving mecA gene recruited preferentially specific housekeeping genes, such as murT-gatD, for their beta-lactam resistance strategy. To address the importance of mecA presence in this alternative resistance strategy, murT-gatD mutation was transferred into a mecA-independent resistant strain, M100, with a truncated PBP3. The murT-gatD impairment resulted in a decrease in the level of resistance of the M100 strain, indicating that peptidoglycan amidation is essential for a mecA-independent resistant strategy.

To assess the importance of different steps of peptidoglycan biosynthesis in this alternative strategy of mecA-associated resistance, murF gene was chosen for further testing. On one hand, MurF catalyzes a crucial step of the primary pathway of peptidoglycan biosynthesis; on the other hand, it is a well-documented auxiliary gene for COL background.48 While for most genetic backgrounds the impact of murF impairment in the resistance profile was comparable to the one of murT-gatD, for MW2/USA400 and ST398 strains, murT-gatD conditional mutation showed a drastic and unique effect. Further, the inhibition of murF transcription did not affect the level of resistance in the mecA-negative strain M100, suggesting that the contribution of murF auxiliary gene for beta-lactam resistance is related to the presence of mecA.

Therefore, the alternative strategy for beta-lactam resistance seems to rely on genes involved in peptidoglycan secondary modifications, as secondary cross-linking (pbp4) and amidation (murT-gatD).32 Recently, Zapun et al.52 showed that in Streptococcus pneumoniae, peptidoglycan amidation catalyzed by MurT-GatD complex is necessary for efficient cross-linking by PBP2a, PBP2b, and PBP2×. PBP1a retained some activity for nonamidated lipid precursors. Although the substrate preferences of S. aureus PBPs regarding the amidation status of the precursor molecule are not known, it seems reasonable to speculate that PBP4 and/or PBP2 also require amidated precursors to perform transpeptidation, as these two proteins appear to be involved in the alternative mechanism of resistance to beta-lactams.32

Moreover, besides being essential for optimal beta-lactam resistance, the murT-gatD operon is also needed for optimal lysozyme resistance, evidencing its role in virulence. We also observed that the impairment of murT-gatD operon had a strong impact on lysozyme resistance in CA-MRSA backgrounds. For the HA backgrounds, the impact of this mutation is more variable, according to the genetic background. However, the lysozyme resistance levels of purified peptidoglycan were similar for strains from both CA and HA settings. This observation indicates that specific factors, intrinsic to the strain genetic background, contribute to the final lysozyme resistance level, although dependent on the amidation status of the cell wall.

The results reported in this communication suggest that peptidoglycan amidation is involved through different mechanistic links in the beta-lactam resistance strategies of strains from distinct backgrounds, evidencing in this way the existence of more than one physiological approach for survival to antibiotic stress.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The work was supported by contract PTDC/BIA-MIC/3195/2012 (Fundação para a Ciência e Tecnologia, Portugal) and P-99911 (Fundação Calouste Gulbenkian) awarded to H. de Lencastre, and PTDC/BIA-MIC/101375/2008 (FCT, Portugal) awarded to R.G. Sobral. The work was supported additionally by FCT through grant numbers PEst-OE/EQB/LA0004/2011 and PEst-OE/BIA/UI0457/2011. T.A.F. was supported by the following fellowships: SFRH/BD/36843/2007 (Fundação para a Ciência e Tecnologia, Portugal), 132/BI-BI/2011 (Fundação para a Ciência e Tecnologia, Portugal), 057/BI-BI/2012 (Fundação Calouste Gulbenkian), 112/BI-BI/2012 (Fundação para a Ciência e Tecnologia, Portugal), and 102/BI-BI/2013 (Fundação para a Ciência e Tecnologia, Portugal).

Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.Aires-de-Sousa M., Correia B., de Lencastre H., and Multilaboratory Project Collaborators. 2008. Changing patterns in frequency of recovery of five methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus clones in Portuguese hospitals: surveillance over a 16-year period. J. Clin. Microbiol. 46:2912–2917 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Armand-Lefevre L., Ruimy R., and Andremont A.2005. Clonal comparison of Staphylococcus aureus isolates from healthy pig farmers, human controls, and pigs. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 11:711–714 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bera A., Herbert S., Jakob A., Vollmer W., and Gotz F.2005. Why are pathogenic staphylococci so lysozyme resistant?. The peptidoglycan O-acetyltransferase OatA is the major determinant for lysozyme resistance of Staphylococcus aureus. Mol. Microbiol. 55:778–787 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Berger-Bächi B. 1983. Insertional inactivation of staphylococcal methicillin resistance by Tn551. J. Bacteriol. 154:479–487 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Berger-Bächi B., Strässle A., Gustafson J.E., and Kayser F.H. 1992. Mapping and characterization of multiple chromosomal factors involved in methicillin resistance in Staphylococcus aureus. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 36:1367–1373 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 1999. Four pediatric deaths from community acquired methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus-Minnesota and North Dakota, 1997–1999. JAMA 282:1123–1125 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chambers H.F.2001. The changing epidemiology of Staphylococcus aureus?. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 7:178–182 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chung M., de Lencastre H., Matthews P., Tomasz A., Adamsson I., Aires de Sousa M., et al. 2000. Molecular typing of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis: comparison of results obtained in a multilaboratory effort using identical protocols and MRSA strains. Microb. Drug Resist. 6:189–198 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Collins J., Buckling A., and Massey R.C.2008. Identification of factors contributing to T-cell toxicity of Staphylococcus aureus clinical isolates. J. Clin. Microbiol. 46:2112–2114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Collins J., Rudkin J., Recker M., Pozzi C., O'Gara J.P., and Massey R.C. 2010. Offsetting virulence and antibiotic resistance costs by MRSA. ISME J 4:577–584 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Conceição T., Tavares A., Miragaia M., Hyde K., Aires-de-Sousa M., and de Lencastre H.2010. Prevalence and clonality of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) in the Atlantic Azores islands: predominance of SCCmec types IV, V and VI. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 29:543–550 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.David M.Z., and Daum R.S. 2010. Community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus: epidemiology and clinical consequences of an emerging epidemic. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 23:616–687 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.De Lencastre H., Figueiredo A.M., and Tomasz A.1993. Genetic control of population structure in heterogeneous strains of methicillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 12:13–18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.De Lencastre H., Wu S.H., Pinho M.G., Ludovice A.M., Filipe S., Gardete S., Sobral R., Gill S., Chung M., and Tomasz A. 1999. Antibiotic resistance as a stress response: complete sequencing of a large number of chromosomal loci in Staphylococcus aureus strain COL that impact on the expression of resistance to methicillin. Microb. Drug Resist. 5:163–175 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.DeLeo F.R., Otto M., Kreiswirth B.N., and Chambers H.F. 2010. Community-associated meticillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Lancet 375:1557–1568 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Faria N.A., Oliveira D.C., Westh H., Monnet D.L., Larsen A.R., Skov R., and de Lencastre H. 2005. Epidemiology of emerging methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) in Denmark: a nationwide study in a country with low prevalence of MRSA infection. J. Clin. Microbiol. 43:1836–1842 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Figueiredo T.A., Sobral R.G., Ludovice A.M., Almeida J.M., Bui N.K., Vollmer W., de Lencastre H., and Tomasz A. 2012. Identification of genetic determinants and enzymes involved with the amidation of glutamic acid residues in the peptidoglycan of Staphylococcus aureus. PLoS Pathog. 8:e1002508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gordon R.J., and Lowy F.D. 2008Pathogenesis of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infection. Clin. Infect. Dis. 46:S350–S359 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Herbert S., Bera A., Nerz C., Kraus D., Peschel A., Goerke C., Meehl M., Cheung A., and Gotz F.2007. Molecular basis of resistance to muramidase and cationic antimicrobial peptide activity of lysozyme in staphylococci. PLoS Pathog. 3:e102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Herold B.C., Immergluck L.C., Maranan M.C., Lauderdale D.S., Gaskin R.E., Boyle-Vavra S., Leitch C.D., and Daum R.S. 1998. Community-acquired methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in children with no identified predisposing risk. JAMA 279:593–598 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Horner C., Parnell P., Hall D., Kearns A., Heritage J., and Wilcox M.2013. Meticillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in elderly residents of care homes: colonization rates and molecular epidemiology. J. Hosp. Infect. 83:212–218 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Katayama Y., Robinson D.A., Enright M.C., and Chambers H.F. 2005. Genetic background affects stability of mecA in Staphylococcus aureus. J. Clin. Microbiol. 43:2380–2383 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Katayama Y., Zhang H.Z., and Chambers H.F.2003. Effect of disruption of Staphylococcus aureus pbp4 gene on resistance to beta-lactam antibiotics. Microb. Drug Resist. 9:329–336 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Klevens R.M., Morrison M.A., Fridkin S.K., Reingold A., Petit S., Gershman K., Ray S., Harrison L.H., Lynfield R., Dumyati G., Townes J.M., Craig A.S., Fosheim G., McDougal L.K., Tenover F.C., and the Active Bacterial Core Surveillance of the Emerging Infections Program Network. Tenover, and the Active Bacterial Core Surveillance of the Emerging Infections Program Network. 2006. Community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus and healthcare risk factors. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 12:1991–1993 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kornblum J., Hartman B.J., Novick R.P., and Tomasz A. 1986. Conversion of a homogeneously methicillin-resistant strain of Staphylococcus aureus to heterogeneous resistance by Tn551-mediated insertional inactivation. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. 5:714–718 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kos V.N., Desjardins C.A., Griggs A., Cerqueira G., Van Tonder A., Holden M.T., Godfrey P., Palmer K.L., Bodi K., Mongodin E.F., Wortman J., Feldgarden M., Lawley T., Gill S.R., Haas B.J., Birren B., and Gilmore M.S. Comparative genomics of vancomycin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus strains and their positions within the clade most commonly associated with Methicillin-resistant S. aureus hospital-acquired infection in the United States. mBio 3:e00112–e00112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lowy F.D.1998. Staphylococcus aureus infections. N. Engl. J. Med. 20:520–532 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ludovice A.M., Wu S.W., and de Lencastre H. 1998. Molecular cloning and DNA sequencing of the Staphylococcus aureus UDP-N-acetylmuramyl tripeptide synthetase (murE) gene, essential for the optimal expression of methicillin resistance. Microb. Drug Resist. 4:85–90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Marchese A., Gualco L., Maioli E., and Debbia E.E.2009. Molecular analysis and susceptibility patterns of meticillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) strains circulating in the community in the Ligurian area, a northern region of Italy: emergence of USA300 and EMRSA-15 clones. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 34:424–428 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Maugat S., de Rougemont A., Aubry-Damon H., Reverdy M.E., Georges S., Vandenesch F., Etienne J., and Coignard B. 2009. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus among a network of French private-sector community-based-medical laboratories. Med. Mal. Infect. 39:311–318 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.McDougal L.K., Steward C.D., Killgore G.E., Chaitram J.M., McAllister S.K., and Tenover F.C. 2003. Pulsed-field gel electrophoresis typing of oxacillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus isolates from the United States: establishing a national database. J. Clin. Microbiol. 41:5113–5120 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Memmi G., Filipe S.R., Pinho M.G., Fu Z., and Cheung A. 2008. Staphylococcus aureus PBP4 is essential for beta-lactam resistance in community-acquired methicillin-resistant strains. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 52:3955–3966 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Moran G.J., Krishnadasan A., Gorwitz R.J., Fosheim G.E., McDougal L.K., Carey R.B., Talan D.A., andEMERGEncy ID Net Study Group.2006. Methicillin-resistant S. aureus infections among patients in the emergency department. N. Engl. J. Med. 355:666–674 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Munch D., Roemer T., Lee S.H., Engeser M., Sahl H.G., and Schneider T. 2012. Identification and in vitro analysis of the GatD/MurT enzyme-complex catalyzing lipid II amidation in Staphylococcus aureus. PLoS Pathog. 8:e1002509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Murakami K., and Tomasz A.1989. Involvement of multiple genetic determinants in high-level methicillin resistance in Staphylococcus aureus. J. Bacteriol. 171:874–879 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nair D., Memmi G., Hernandez D., Bard J., Beaume M., Gill S., Francois P., and Cheung A.L.2011. Whole-genome sequencing of Staphylococcus aureus strain RN4220, a key laboratory strain used in virulence research, identifies mutations that affect not only virulence factors but also the fitness of the strain. J. Bacteriol. 193:2332–2335 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.O'Brien F.G., Pearman J.W., Gracey M., Riley T.V., and Grubb W.B. 1999. Community strain of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus involved in a hospital outbreak. J. Clin. Microbiol. 37:2858–2862 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Oliveira D.C., Tomasz A., and de Lencastre H. 2002. Secrets of success of a human pathogen: molecular evolution of pandemic clones of meticillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2:180–189 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Oliveira D.C., Tomasz A., and de Lencastre H. 2001. The evolution of pandemic clones of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus: identification of two ancestral genetic backgrounds and the associated mec elements. Microb. Drug Resist. 7:349–361 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Oliveira D.C., Crisóstomo I., Santos-Sanches I., Major P., Alves C.R., Aires-de-Sousa M., Thege M.K., and de Lencastre H. 2001. Comparison of DNA sequencing of the protein A gene polymorphic region with other molecular typing techniques for typing two epidemiologically diverse collections of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. J. Clin.Microbiol. 39:574–580 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Oshida T., and Tomasz A.1992. Isolation and characterization of a Tn551-autolysis mutant of Staphylococcus aureus. J. Bacteriol. 174:4952–4959 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pereira S.F., Henriques A.O., Pinho M.G., de Lencastre H., and Tomasz A. 2007. Role of PBP1 in cell division of Staphylococcus aureus. J. Bacteriol. 189:3525–3531 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pinho M.G., de Lencastre H., and Tomasz A. 2000. Cloning, characterization, and inactivation of the gene pbpC, encoding penicillin-binding protein 3 of Staphylococcus aureus. J. Bacteriol. 182:1074–1079 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pinho M.G., Filipe S.R., de Lencastre H., and Tomasz A. 2001. Complementation of the essential peptidoglycan transpeptidase function of penicillin-binding protein 2 (PBP2) by the drug resistance protein PBP2A in Staphylococcus aureus. J. Bacteriol. 183:6525–6531 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Robinson D.A., and Enright M.C. 2003. Evolutionary models of the emergence of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 47:3926–3934 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rolo J., Miragaia M., Turlej-Rogacka A., Empel J., Bouchami O., Faria N.A., Tavares A., Hryniewicz W., Fluit A.C., de Lencastre H., and CONCORD Working Group. 2012. High genetic diversity among community-associated Staphylococcus aureus in Europe: results from a multicenter study. PLoS One 7:e34768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sá-Leão R., Santos Sanches I., Dias D., Peres I., Barros R.M., and de Lencastre H. 1999. Detection of an archaic clone of Staphylococcus aureus with low-level resistance to methicillin in a pediatric hospital in Portugal and in international samples: relics of a formerly widely disseminated strain?. J. Clin. Microbiol. 37:1913–1920 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sobral R.G., Ludovice A.M., de Lencastre H., and Tomasz A. 2006. Role of murF in cell wall biosynthesis: isolation and characterization of a murF conditional mutant of Staphylococcus aureus. J. Bacteriol. 188:2543–2553 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sobral R.G., Ludovice A.M., Gardete S., Tabei K., De Lencastre H., and Tomasz A. 2003. Normally functioning murF is essential for the optimal expression of methicillin resistance in Staphylococcus aureus. Microb. Drug Resist. 9:231–241 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tavares A., Miragaia M., Rolo J., Coelho C., de Lencastre H., and CA-MRSA/MSSA working group. 2013. High prevalence of hospital-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in the community in Portugal: evidence for the blurring of community-hospital boundaries. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 32:1269–1283 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Tonin E., and Tomasz A.1986. Beta-lactam-specific resistant mutants of Staphylococcus aureus. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 30:577–583 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zapun A., Philippe J., Abrahams K.A., Signor L., Roper D.I., Breukink E., and Vernet T. 2013. In vitro reconstitution of peptidoglycan assembly from the Gram-positive pathogen Streptococcus pneumoniae. ACS Chem. Biol. 8:2688–2696 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.