Abstract

Gram-negative bacteria recycle as much as half of their cell wall per generation. Here we show that interference with cell wall recycling in Pseudomonas aeruginosa strains results in four- to eight-fold increased susceptibility to the antibiotic fosfomycin, pushing the minimal inhibitory concentration for strains PA14 and PA01 to therapeutically appropriate values of 2–4 and 8–16 mg/L, respectively. A newly discovered metabolic pathway that connects cell wall recycling with peptidoglycan de novo biosynthesis is responsible for the high intrinsic resistance of P. aeruginosa to fosfomycin. The pathway comprises an anomeric cell wall amino sugar kinase (AmgK) and an uridylyl transferase (MurU), which together convert N-acetylmuramic acid (MurNAc) through MurNAc α-1-phosphate to uridine diphosphate (UDP)-MurNAc, thereby bypassing the fosfomycin-sensitive de novo synthesis of UDP-MurNAc. Thus, inhibition of peptidoglycan recycling can be applied as a new strategy for the combinatory therapy against multidrug-resistant P. aeruginosa strains.

Introduction

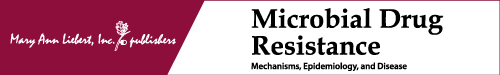

The rapid emergence of antimicrobial drug resistance, particularly in gram-negative bacteria such as Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and the critical shortage of new antibiotics in the development against multidrug-resistant strains led to reconsider the therapeutic potential of old antibiotics.2,3,38 An example of such a well-known antibiotic that was reintroduced into clinical practice is fosfomycin.6,24,26,34 This epoxide derivative of phosphonic acid (cis-1,2-epoxypropyl phosphonic acid) was discovered in 1969, originally named phosphonomycin, and was isolated from cultures of Streptomyces species.11 Fosfomycin interferes with the first cytoplasmatic step of bacterial cell wall biosynthesis, the formation of the peptidoglycan precursor uridine diphosphate N-acetylmuramic acid (UDP-MurNAc)15 and, thus, results in decelerated peptidoglycan synthesis, reduced growth, and eventually cell lysis.15,23 The UDP-N-acetylglucosamine (UDP-GlcNAc) enolpyruvyl transferase MurA, which catalyzes the transfer of enolpyruvate from phosphoenol pyruvate (PEP) to UDP-GlcNAc, is irreversibly inhibited by the PEP-mimetic fosfomycin (Fig. 1), which covalently binds to the catalytic cysteine residue of MurA.16

FIG. 1.

Simplified scheme of the peptidoglycan recycling pathway in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Peptidoglycan recycling (colored red) contributes to the pool of UDP-MurNAc by conversion of 1,6-anhydro-MurNAc (AnhMurNAc) through the AnhMurNAc kinase (AnmK), MurNAc 6-phosphate phosphatase (not yet identified), anomeric GlcNAc/MurNAc kinase (AgmK), and MurNAc α-1-phosphate-uridylyl transferase (MurU). Thereby, the recycling pathway bypasses de novo biosynthesis of the peptidoglycan precursor UDP-MurNAc (colored blue), including the fosfomycin target MurA (chemical structure of fosfomycin).

Initially, fosfomycin disodium salt was applied parenterally as an alternative drug to treat patients with severe and multidrug-resistant infections.34 Later on, fosfomycin has been produced in a hydrosoluble form, fosfomycin–trometamol (also known as tromethamine or TRIS), and administrated orally for the treatment of uncomplicated urinary tract and gastrointestinal infections.6,32 Due to its long mean half-life (5.7±2.8 hr), low toxicity, and low side effects, this drug is used alone25 or in combination with tobramycin37 to treat chronic pulmonary infections caused by multidrug-resistant P. aeruginosa strains in cystic fibrosis patients. Fosfomycin has been efficiently used in combination with various antimicrobial agents and in some cases, synergetic effects have been reported.20,28,39

Because of its small size (138 Da) and polarity, fosfomycin can readily cross the outer membrane of gram-negative bacteria through porins.10 In Pseudomonas sp., it is further actively transported into the cell by the glycerol-3-phosphate transporter GlpT.5 Mutations in glpT lead to decreased drug transport that result in fosfomycin resistance (reviewed in Castañeda-García et al.4). Fosfomycin resistance in Pseudomonas sp. may also be mediated by a plasmid-encoded or chromosomally encoded thiol transferase enzyme (FosA) that causes antibiotic inactivation by opening the epoxide ring of fosfomycin30,35,36 and leads to acquired drug resistance.27 Besides, P. aeruginosa strains generally exhibit a considerable rate of intrinsic resistance to fosfomycin. Minimal inhibitory concentrations (MICs) for fosfomycin of up to 512 mg/L in randomly selected P. aeruginosa strains were determined by agar dilution methods.7 According to the EUCAST criteria (URL: www.eucast.org/), P. aeruginosa species with a susceptibility ≥32 mg/L are classified as fosfomycin-resistant strains.19

We have recently elucidated a connection of cell wall recycling and intrinsic fosfomycin resistance in Pseudomonas putida.8 A novel cell wall salvage pathway was identified in this organism that bypasses the de novo biosynthesis of UDP-MurNAc (Fig. 1). This pathway, absent in Escherichia coli and related Enterobacteria, involves three enzymes, (1) a not-yet identified MurNAc 6-phosphate (MurNAc 6P) phosphatase, (2) an anomeric MurNAc kinase (AmgK), which forms MurNAc α-1-phosphate (MurNAc α1P), and (3) an uridylyl transferase (MurU), which transfers uridine phosphate from UTP to the MurNAc α1P, yielding UDP-MurNAc.8 However, Pseudomonas sp., similar to E. coli, possess upstream of this salvage pathway enzymes for muropeptide processing, a recycling N-acetylglucosaminidase (NagZ) that yields N-acetylglucosamine (GlcNAc) and 1,6-anhydroMurNAc (AnhMurNAc) peptides, an AnhMurNAc-peptide amidase (AmpD), and an AnhMurNAc kinase (AnmK) (Fig. 1) (for more details, see Gisin et al.8 and Park and Uehara31). In this study, we show that the two pathogenic P. aeruginosa strains, PAO1 and PA14, also possess the MurNAc salvage route. Blocking this cell wall recycling pathway decreases the fosfomycin resistance of these strains at least four times, thereby pushing the MICs for the drug below the susceptibility threshold of 32 mg/L. Thus, a combinatory therapy of fosfomycin along with peptidoglycan recycling inhibitors may develop into a new strategy against multidrug-resistant P. aeruginosa strains.

Materials and Methods

Bacterial strains and culturing conditions, plasmids, and reagents

Bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in Table 1. P. aeruginosa strain PA01 was obtained from Prof. Friedrich Götz, University of Tübingen. Strain PA14 and the complete nonredundant transposon insertion mutant library were obtained from the Broad Institute, Cambridge, MA,18 which included amgK, murU, and anmK insertion mutants (07780::MAR2xT7, 07790::MAR2xT7, and 08520::MAR2xT7 clone 06_3F4, respectively). P. aeruginosa and E. coli strains were cultured at 37°C in Luria-Bertani (LB) liquid or solid (plus 15% agar) medium. For antibiotic susceptibility studies, cation-adjusted Mueller-Hinton broth (Sigma-Aldrich) liquid or solid medium was applied. E-test fosfomycin strips were obtained from BioMérieux, Craponne, France. Fosfomycin disodium salt powder and Irgasan were ordered from Sigma-Aldrich. Imipenem and ceftazidime powders were from Santa Cruz Biotechnology. Phusion high-fidelity polymerase, SmaI restriction enzyme, and E. coli DH5α cells were obtained from New England Biolabs. T4 DNA ligase, genomic and plasmid DNA isolation kits, and DNA gel extraction kits were from Thermo Scientific.

Table 1.

Bacterial Strains Used in This Study

| Strain | Genotype | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Pseudomonas strains | ||

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa PA01 | Reference strain 01 | 12 |

| PA01 Δ0596 (amgK) | PA0596 deletion mutant of PA01 | This study |

| PA01 Δ0597 (murU) | PA0597 deletion mutant of PA01 | This study |

| PA01 Δ0666 (anmK) | PA0666 deletion mutant of PA01 | This study |

| PA01 Δ3005 (nagZ) | PA3005 deletion mutant of PA01 | This study |

| P. aeruginosa PA14 | Reference strain UCBPP-PA14, human isolate | 33 |

| 07780::MAR2xT7 (amgK) | GmR, PA07780 Tn insertion mutant of PA14 | 18 |

| 07790::MAR2xT7 (murU) | GmR, PA07790 Tn insertion mutant of PA14 | 18 |

| 08520::MAR2xT7 (06_3F4) (anmK) | GmR, PA08520 Tn insertion mutant of PA14 | 18 |

| Escherichia coli strain | ||

| DH5α | supE44 hsdR17 recA1 endA1 gyrA96 thi-1 relA1 23 | 9 |

| Plasmids | ||

| pEX18Gm Δ0596 (amgK) | Up/Ds PA0596 in pEX18Gm, SmaI | This study |

| pEX18Gm Δ0597 (murU) | Up/Ds PA0597 in pEX18Gm, SmaI | This study |

| pEX18Gm Δ0666 (anmK) | Up/Ds PA0666 in pEX18Gm, SmaI | This study |

| pEX18Gm Δ3005 (nagZ) | Up/Ds PA3005 in pEX18Gm, SmaI | This study |

Construction of cell wall recycling knockout mutants

For the generation of markerless knockout mutants in strain PA01 of genes PA0596 (MurNAc kinase), PA0597 (MurNAc 1P uridylyl transferase), PA0666 (AnhMurNAc kinase), and PA3005 (N-acetylglucosaminidase NagZ), PA01 genomic DNA was isolated according to the manufacturer's instructions. Ten nanograms of genomic DNA was used to amplify ≈500 bp regions upstream and downstream of the target genes by PCR (primer pairs 1 and 2, respectively; for the primer list, see Table 2). DNA products were purified using a polynucleotide gel extraction kit and further spliced by PCR yielding ≈1,000 bp products. Subsequently, the plasmid pEX18Gm was digested with SmaI and blunt end-ligated overnight with the ≈1,000 bp PCR products using T4 DNA ligase. Reactions were transformed in chemically competent E. coli DH5α cells.13 Transformants were then selected on LB agar plates supplemented with 10 μg/ml gentamycin (Gm). Recombinant plasmids were isolated from single DH5α transformants and the DNA sequences were checked by restriction analysis and DNA sequencing (Eurofins). The suicide plasmids (pEX18Gm ΔamgK, pEX18Gm ΔmurU, and pEX18Gm ΔanmK) were further transformed in chemically competent E. coli helper strain S17-1 λ pir and selected on LB agar plates with 10 μg/ml Gm. For diparental mating, 0.8 ml of overnight cultures (incubated at 37°C) of S17-1 λ pir cells, containing the suicide plasmids, and 1.7 ml PA01 wild-type cells, grown at 43°C, were mixed, centrifuged, and resuspended in 200 μl of final volume. The cell suspension was plated for 4 hr at 37°C on membrane filters on top of the LB agar plates to allow transfer of the suicide plasmids from E. coli into Pseudomonas PA01 wild-type strains during conjugation. Filters were resuspended in 0.9% NaCl and all bacteria were plated on LB supplemented with 60 μg/ml Gm and 25 μg/ml Irgasan (to kill E. coli cells). Successful PA01 merodiploids were growing in the presence of antibiotic and further selected for double crossover events on LB plates without salt and 5% sucrose. The generation of mutants was verified by the absence of growth in the presence of Gm, colony PCR with specific primers in the flanking regions (test primers) for PA0596, PA0597, and PA0666 gene deletions (Table 2).

Table 2.

Collection of Nucleotide Primers

| Primers | Primer sequence 5′-3′ | Application |

|---|---|---|

| 0596 Fw pair1 | GGCGGTCAGTTTTTCCCGAG | amgK deletion |

| 0596 Rev pair1 | TCGGCTCCCTGCGGTTCTCCACGGCCCTAGC | |

| 0596 Fw pair2 | CCGTGGAGAACCGCAGGGAGCCGAGGCATGAA | |

| 0596 Rev pair2 | CAGTACGGCGATCCCGCTG | |

| 0596 Fw test | TTGGCGGATACGTAGGTCGG | |

| 0596 Rev test | GCCAGCAATCGCTCGACTTC | |

| 0597 Fw pair1 | GCCCGCTGGAAACGGATCTG | murU deletion |

| 0597 Rev pair1 | AGCGGGCCAGAGCATGCCTCGGCTCCCTGC | |

| 0597 Fw pair2 | AGCCGAGGCATGCTCTGGCCCGCTACGCTGATCG | |

| 0597 Rev pair2 | GTTCGCTCCGCCGACCAAC | |

| 0597 Fw test | CCTTCCAGAAGGTCGATGTC | |

| 0597 Rev test | GCCAGTTTGTCCGGATGATG | |

| 0666 Fw pair1 | GTGGATTTCGCCCGTATCAG | anmK deletion |

| 0666 Rev pair1 | GGACCGAGCGCAATCAGCGCTGCTTGTTCAGGG | |

| 0666 Fw pair2 | AGCAGCGCTGATTGCGCTCGGTCCCAGAACTC | |

| 0666 Rev pair2 | CTGGGACAAGAGGATAATGG | |

| 0666 Fw test | TCAACCGTGGCAAGACCTAC | |

| 0666 Rev test | CATGTGATCATCGACGGTCAG | |

| 3005 Fw pair1 | CTACATGCTGCTGGTCAAC | nagZ deletion |

| 3005 Rev pair1 | ATCAGTTGCGCACCGATGTCGAGCATCAGAG | |

| 3005 Fw pair2 | GCTCGACATCGGTGCGCAACTGATTGATTGAGGG | |

| 3005 Rev pair2 | TAGACCCCATGGCTGCTGTG |

Overlapping regions of primer pairs are shown in bold.

LC-MS analysis of cell wall recycling intermediates

PA01 wild-type and respective recycling deletion mutants, as well as PA14 wild-type and the respective recycling transposon insertion mutants were grown overnight in 50 ml of LB medium. After 20 hr of incubation, bacterial cultures (OD600nm ≈3.2) were centrifuged (10 min, 4,000 g) and pellets were dissolved in 10 ml of Tris buffer (10 mM, pH 7.6). After two washing steps, pellets were taken up in 400 μl of water and heated for 10 min at 95°C to cause cell breakage. Soluble cell extracts, containing the cell wall recycling products, were obtained by spinning down at maximum speed (12,000 g for 15 min). By adding 800 μl of acetone to each 200 μl of supernatant in an Eppendorf tube, protein precipitation was achieved and the remaining insoluble part was separated by centrifugation at maximum speed. The supernatant was transferred to a clean tube and dried in a speedvac at 60°C. The dried pellet was dissolved in 160 μl water before LC-MS measurement. Analysis of the accumulation of recycling products in P. aeruginosa mutants was conducted with a ESI-TOF mass spectrometer (MicrO-TOF II, Bruker) that was connected to the Ultimate 3000 HPLC system (Dionex), as previously described.8 For high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) separation, a Gemini C18 column (Phenomenex, 150×4.6 mm, 110Å, 5 μM) was used. Samples (5 μl injection volume) were applied to the HPLC column at a flow rate of 0.2 ml/min and using a 45-min program (for 5 min, 100% buffer A: 0.1% formic acid with 0.05% ammonium formate, then 30 min of a linear gradient to 40% buffer B with 100% acetonitrile, 5 min of 40% buffer B, and 5 min of re-equilibration step). Data are presented as differential ion chromatograms (ΔTIC). These were obtained by subtracting the total ion chromatogram (TIC) of a mutant cell extract minus the TIC of the respective wild-type extract, calculated by automatically subtracting TICs using the program called “Metabolite Detect” (Bruker).

Determination of the MICs

MICs for P. aeruginosa strains PA01 and PA14 were determined by using the broth microdilution method, according to the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) recommendations or by applying E-test fosfomycin strips following the manufacturer's instructions. Briefly, the broth microdilution method was performed in U-form 96-well plates (VWR) using the Mueller-Hinton Broth (cation-adjusted) medium in a total volume of 100 μl and a shaking incubator at 35°C, 160 rpm for 20 hr in a humidified chamber. Bacteria were harvested at an optical density (OD600nm) of 0.3 and diluted to a starter culture of 1×104 cells. Appropriate dilution series of the antibiotic fosfomycin (FOS, 0.5–256 mg/ml), imipenem (IMP, 0.0625–8 mg/L), and ceftazidime (CAZ, 0.0625–8 mg/L) were previously diluted in the broth medium. The absence of growth at the lowest used antibiotic concentration was determined as the MIC value.

For E-tests, fosfomycin strips with a dilution range between 0.064 and 1,024 mg/ml and Mueller-Hinton broth (with Ca and Mg ions) agar plates (17.5 ml) were used. Pseudomonas overnight cultures were adjusted with 0.9% NaCl to 0.5 McFarland standard and bacteria were transferred with a sterile loop to the plates. Results were documented after incubation at 37°C for 20 hr.

Results and Discussion

Peptidoglycan recycling in P. aeruginosa involves a direct shortcut pathway to UDP-MurNAc

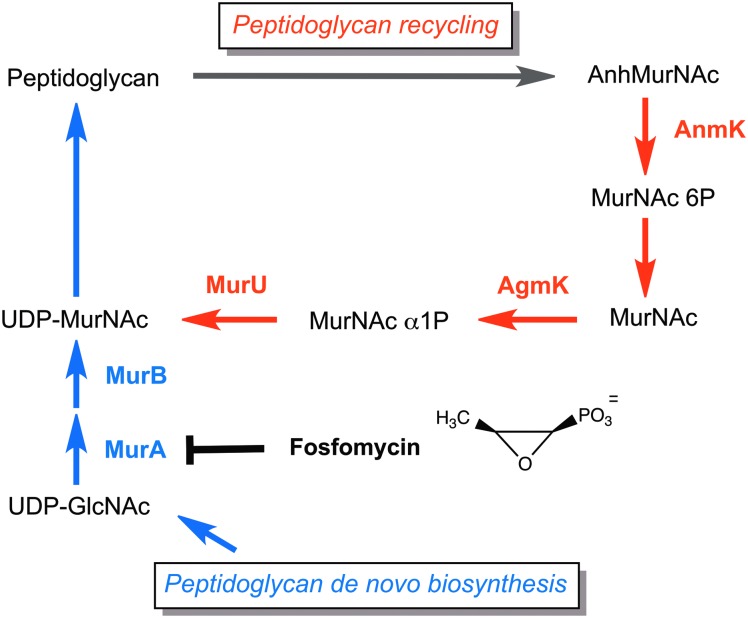

We first aimed to investigate whether peptidoglycan recycling in P. aeruginosa PA01 and PA14 involves orthologs of the newly discovered recycling genes amgK and murU of P. putida. If so, we expected that mutants for these genes will accumulate specific recycling intermediates, as was previously shown for P. putida.8 Therefore, we generated markerless deletion mutants in PA01 of genes PA0596 (ΔamgK) and PA0597 (ΔmurU), as well as deletion mutants of known recycling genes, PA3005 (ΔnagZ) and PA0666 (ΔanmK). In addition, transposon insertion mutants were obtained from the PA14 mutant collection18 of the respective genes of P. aeruginosa strain PA14 (except for PA14 nagZ mutant, which is not available in this collection). We demonstrated by LC-MS that MurNAc accumulates in the cell extract of amgK mutants (Fig. 2A) and MurNAc 1P accumulates in the cell extract of murU mutants (Fig. 2B), similar to observed accumulation products in P. putida orthologous mutants.8 Moreover, AnhydroMurNAc was shown to accumulate in the anmK mutant strains (Fig. 2C). Thus, these results indicate that AmgK and MurU in P. aeruginosa constitute a shortcut recycling pathway, contributing to the UDP-MurNAc pool.

FIG. 2.

Identification of cell wall recycling products by LC-MS analysis. Total ion chromatograms (TICs) were obtained in the negative ion mode; the y axes represent ion intensity (counts per second). (A) Overlay of GlcNAc (m/z=220.09; colored red) and MurNAc (m/z=292.11), 5 mM each, and differential ion chromatograms (ΔTICs) obtained by subtracting TIC of mutant (PA01 ΔamgK or PA14 amgK::Tn) from the respective wild type. (B) Extracted ion chromatogram (EIC) for MurNAc 1P (m/z=372.07) and PA01 ΔmurU and PA14 murU::Tn ΔTICs. (C) TIC of AnhMurNAc (m/z=274.09), 1 mM, and PA01 ΔanmK and PA14 anmK::Tn ΔTICs.

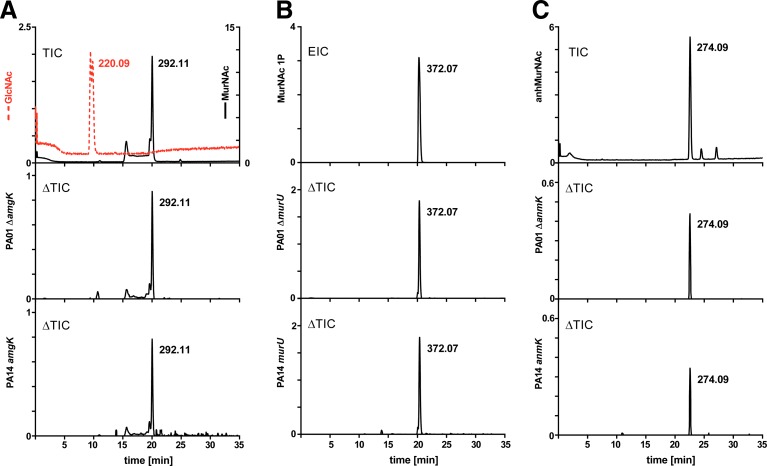

Blocking peptidoglycan recycling in P. aeruginosa does not affect growth

Growth of Pseudomonas wild-type as well as amgK, murU, and anmK mutants was compared using the LB medium. Identical growth rates were observed for wild-type (PA01 and PA14) and respective recycling mutant strains (Fig. 3A, B), indicating that blocking cell wall recycling does not affect general fitness in a rich medium. Previous studies comparing wild-type and recycling mutants in E. coli and P. putida also revealed no difference in growth rates.8,31 Since the peptidoglycan layer of E. coli, and presumably of P. aeruginosa as well, accounts for only about 2% of the cell mass,22 Park and Uehara suggested that cell wall recycling is not essential for cell viability and growth.31 Still, as shown by LC-MS results (Fig. 2), the recycling pathway through AnmK, AmgK, and MurU channels cell wall recycling fragments directly into the UDP-MurNAc pool and, thus, bypasses the MurA-catalyzed enzymatic reaction that is the target of fosfomycin (cf. Fig. 1). Cell wall recycling therefore contributes to the intrinsic fosfomycin resistance in P. aeruginosa.

FIG. 3.

Growth fitness comparison of P. aeruginosa strains in the LB medium. Optical densities (OD600nm) are presented as base 10 logarithms (log10). (A) PA01 wild-type and respective deletion mutants (ΔamgK, ΔmurU, and ΔanmK). (B) PA14 wild-type and respective transposon (Tn) insertion mutants (amgK::Tn, murU::Tn, and anmK::Tn). Results are shown as a mean±SD of two independent experiments, each done in duplicate.

Pseudomonas cell wall recycling mutants are more susceptible to fosfomycin compared with wild type

The contribution of cell wall recycling to the UDP-MurNAc pool, and thus, the intrinsic resistance to fosfomycin, was shown by comparison of the MIC values for Pseudomonas wild-type and mutant strains (Table 3). By using the broth microdilution method, we observed that the MIC value for fosfomycin of 32 mg/L for the PA01 wild type was reduced to 8 mg/L in ΔamgK, ΔmurU, ΔanmK, and ΔnagZ deletion mutants. A fourfold increase in fosfomycin susceptibility in the absence of the indicated PA01 recycling genes was also seen by applying E-test strips; the MICs dropped from 64 mg/L in PA01 wild-type to 16 mg/L in the recycling mutants.

Table 3.

Comparison of Fosfomycin and β-Lactam Resistances in P. aeruginosa Wild-Type and Recycling Mutant Strains

| MIC (mg/L) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Strain | FOSa | FOSb | CAZa | IMPa |

| PA01 wild type | 32 | 64 | 1 | 1 |

| PA01 ΔamgK | 8 | 16 | 1 | 1 |

| PA01 ΔmurU | 8 | 16 | 1 | 1 |

| PA01 ΔanmK | 8 | 16 | 1 | 1 |

| PA01 ΔnagZ | 8 | 16 | 1 | 1 |

| PA14 wild type | 16 | 24 | nd | nd |

| PA14 amgK::Tn | 2 | 4 | nd | nd |

| PA14 murU::Tn | 2 | 4 | nd | nd |

| PA14 anmK::Tn | 2 | 4 | nd | nd |

Sensitivity to fosfomycin (FOS) and the β-lactams ceftazidime (CAZ) and imipenem (IMP) was assayed using either the broth microdilution method (FOS,a CAZ,a and IMPa) or E-test strips for fosfomycin (Fosb).

Represents results of two independent experiments, each done in quadruplets.

Represents the mean of three independent experiments.

nd, not defined.

Overall, fosfomycin susceptibility of strain PA14 was two to three times higher compared with PA01. Still, fosfomycin sensitivity was similarly increased in the PA14 cell wall recycling mutants. Broth microdilution tests showed a MIC value of 16 mg/L for the PA14 wild-type strain, and eightfold decreased MICs (2 mg/L) in the PA14 anmK, amgK, and murU transposon insertion mutants. E-test strips confirmed these results. With this test, a MIC value of 24 mg/L for fosfomycin was determined in the PA14 wild type, and a value of 4 mg/L in the absence of recycling genes (a sixfold increase in fosfomycin sensitivity).

We wondered whether the fosfomycin sensitivity of cell wall recycling mutants is a specific or a general stress response. Therefore, we tested the susceptibility of PA01 wild type and ΔamgK, ΔmurU, ΔanmK, and ΔnagZ mutants toward the β-lactam antibiotics, ceftazidime (a 3rd generation cephalosporin) and imipenem (a carbapenem), both having inhibitory effects on P. aeruginosa.21 We obtained identical MIC values (1 mg/L) for the two antibiotics in wild-type and mutant strains (Table 3). This indicates that blocking cell wall recycling does not generally affect susceptibility to antimicrobial drugs.

Application of fosfomycin in combinatory therapy

Spontaneous mutations in the cell wall recycling pathway are a common cause of acquired resistance to β-lactam antibiotics in P. aeruginosa clinical isolates.40 A specific cell wall recycling product, AnhMurNAc-pentapeptide, was shown to accumulate in these isolates, acting as an inducer of the chromosomally encoded AmpC β-lactamase.14,21 Hyperproduction of AmpC was attenuated by blocking cell wall recycling at the level of NagZ, and thus, β-lactam susceptibility was restored.14,40 We showed that the PA01 ΔnagZ mutant, similar to the other recycling mutants, is four times more susceptible to fosfomycin compared with wild type (Table 3). However, the sensitivity toward the β-lactams ceftazidime and imipenem was not affected in the ΔnagZ mutant (Table 3), in agreement with previous reports.21,40 Nevertheless, in multidrug-resistant clinical isolates, inhibition of cell wall recycling may be applied in a combinatory therapy with fosfomycin to reduce its intrinsic resistance, and simultaneously, the acquired resistance to certain β-lactams.

Conclusions

P. aeruginosa is a problematic opportunistic pathogen, particularly due to its high intrinsic resistance to many antibiotics. In addition to the mechanisms that traditionally have been attributed to intrinsic resistance of P. aeruginosa, such as low permeability, efficient detoxification by efflux pumps, and antibiotic inactivation enzymes, recent studies indicate that intrinsic antibiotic resistance should be considered as an emergent systemic property rather than a specific adaptation to the presence of antibiotics.1,17,29 In this vein, the novel cell wall recycling route in Pseudomonas sp.8 provides a rationale for intrinsic resistance to fosfomycin, that is, the consequence of a unique metabolic pathway of cell wall sugar recovery in this organisms. We suggest compounds that interfere with cell wall recycling can be used to increase fosfomycin sensitivity and may be applied in combination to treat multidrug-resistant P. aeruginosa.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants to CM of the Baden-Württemberg Stiftung (P-BWS-Glyko11), and the German Research Foundation (DFG grant MA2436/4 and SFB766/A15). JG gratefully acknowledges a “Dr. Marietta-Lutze-Stipend,” of the company Dr. Kade AG (Konstanz and Berlin). Special thanks go to Alexander Schneider (Univ. of Tübingen) for valuable LC-MS advice, to Prof. Herbert P. Schweizer for pEX18Gm plasmid, and to Kai Thormann for S17-1 λ pir strain. The authors also thank Prof. Friedrich Götz (Univ. of Tübingen) for the PA01 strain and for the help from his technical team (Daniel Kühner and Regine Stemmler).

Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.Alvarez-Ortega C., Wiegand I., Olivares J., Hancock R.E., and Martinez J.L. 2010. Genetic determinants involved in the susceptibility of Pseudomonas aeruginosa to β-lactam antibiotics. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 54:4159–4167 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bassetti M., Ginocchio F., Mikulska M., Taramasso L., and Giacobbe D.R. 2011. Will new antimicrobials overcome resistance among Gram-negatives? Expert. Rev. Anti. Infect. Ther. 9:909–922 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bergen P.J., Landersdorfer C.B., Lee H.J., Li J., and Nation R.L. 2012. ‘Old’ antibiotics for emerging multidrug-resistant bacteria. Curr. Opin. Infect. Dis. 25:626–633 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Castañeda-García A., Blázquez J., and Rodríguez-Rojas A.2013. Molecular mechanisms and clinical impact of acquired and intrinsic fosfomycin resistance. Antibiotics. 2:217–236 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Castaneda-Garcia A., Rodriguez-Rojas A., Guelfo J.R., and Blazquez J. 2009. The glycerol-3-phosphate permease GlpT is the only fosfomycin transporter in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J. Bacteriol. 191:6968–6974 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Falagas M.E., Giannopoulou K.P., Kokolakis G.N., and Rafailidis P.I. 2008. Fosfomycin: use beyond urinary tract and gastrointestinal infections. Clin. Infect. Dis. 46:1069–1077 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Falagas M.E., Kanellopoulou M.D., Karageorgopoulos D.E., Dimopoulos G., Rafailidis P.I., Skarmoutsou N.D., and Papafrangas E.A. 2008. Antimicrobial susceptibility of multidrug-resistant Gram negative bacteria to fosfomycin. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 27:439–443 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gisin J., Schneider A., Nagele B., Borisova M., and Mayer C. 2013. A cell wall recycling shortcut that bypasses peptidoglycan de novo biosynthesis. Nat. Chem. Biol. 9:491–493 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hanahan D. 1983. Studies on transformation of Escherichia coli with plasmids. J. Mol. Biol. 166:557–580 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hancock R.E., Siehnel R., and Martin N. 1990. Outer membrane proteins of Pseudomonas. Mol. Microbiol. 4:1069–1075 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hendlin D., Stapley E.O., Jackson M., Wallick H., Miller A.K., Wolf F.J, Miller T.W., Chaiet L., Kahan F.M., Foltz E.L., et al. 1969. Phosphonomycin, a new antibiotic produced by strains of streptomyces. Science. 166:122–123 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Holloway B.W.1955. Genetic recombination in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J. Gen. Microbiol. 13:572–581 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Inoue H., Nojima H., and Okayama H.1990. High efficiency transformation of Escherichia coli with plasmids. Gene. 96:23–28 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jacobs C., Frere J.M., and Normark S. 1997. Cytosolic intermediates for cell wall biosynthesis and degradation control inducible β-lactam resistance in gram-negative bacteria. Cell. 88:823–832 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kahan F.M., Kahan J.S., Cassidy P.J., and Kropp H. 1974. The mechanism of action of fosfomycin (phosphonomycin). Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 235:364–386 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kim D.H., Lees W.J., Kempsell K.E., Lane W.S., Duncan K., and Walsh C.T. 1996. Characterization of a Cys115 to Asp substitution in the Escherichia coli cell wall biosynthetic enzyme UDP-GlcNAc enolpyruvyl transferase (MurA) that confers resistance to inactivation by the antibiotic fosfomycin. Biochemistry. 35:4923–4928 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Krahn T., Gilmour C., Tilak J., Fraud S., Kerr N., Lau C.H., and Poole K. 2012. Determinants of intrinsic aminoglycoside resistance in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 56:5591–5602 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liberati N.T., Urbach J.M., Miyata S., Lee D.G., Drenkard E., Wu G., Villanueva J., Wei T., and Ausubel F.M. 2006. An ordered, nonredundant library of Pseudomonas aeruginosa strain PA14 transposon insertion mutants. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 103:2833–2838 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lu C.L., Liu C.Y., Huang Y.T., Liao C.H., Teng L.J., Turnidge J.D., and Hsueh P.R. 2011. Antimicrobial susceptibilities of commonly encountered bacterial isolates to fosfomycin determined by agar dilution and disk diffusion methods. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 55:4295–4301 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.MacLeod D.L., Barker L.M., Sutherland J.L., Moss S.C., Gurgel J.L, Kenney T.F., Burns J.L., and Baker W.R. 2009. Antibacterial activities of a fosfomycin/tobramycin combination: a novel inhaled antibiotic for bronchiectasis. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 64:829–836 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mark B.L., Vocadlo D.J., and Oliver A. 2011. Providing β-lactams a helping hand: targeting the AmpC β-lactamase induction pathway. Future Microbiol. 6:1415–1427 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Matias V.R., Al-Amoudi A., Dubochet J., and Beveridge T.J. 2003. Cryo-transmission electron microscopy of frozen-hydrated sections of Escherichia coli and Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J. Bacteriol. 185:6112–6118 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mengin-Lecreulx D., and van Heijenoort J.1990. Correlation between the effects of fosfomycin and chloramphenicol on Escherichia coli. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 54:129–133 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Michalopoulos A.S., Livaditis I.G., and Gougoutas V. 2011. The revival of fosfomycin. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 15:e732–e739 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mirakhur A., Gallagher M.J., Ledson M.J., Hart C.A., and Walshaw M.J. 2003. Fosfomycin therapy for multiresistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa in cystic fibrosis. J. Cyst. Fibros. 2:19–24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Neuner E.A., Sekeres J., Hall G.S., and van Duin D. 2012. Experience with fosfomycin for treatment of urinary tract infections due to multidrug-resistant organisms. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 56:5744–5748 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nikolaidis I., Favini-Stabile S., and Dessen A. 2014. Resistance to antibiotics targeted to the bacterial cell wall. Protein Sci. 23:243–259 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Okazaki M., Suzuki K., Asano N., Araki K., Shukuya N., Egami T., Higurashi Y., Morita K., Uchimura H., and Watanabe T. 2002. Effectiveness of fosfomycin combined with other antimicrobial agents against multidrug-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolates using the efficacy time index assay. J. Infect. Chemother. 8:37–42 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Olivares J., Bernardini A., Garcia-Leon G., Corona F., Sanchez M.B., and Martinez J.L. 2013. The intrinsic resistome of bacterial pathogens. Front Microbiol. 4:103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pakhomova S., Rife C.L., Armstrong R.N., and Newcomer M.E. 2004. Structure of fosfomycin resistance protein FosA from transposon Tn2921. Protein Sci. 13:1260–1265 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Park J.T., and Uehara T. 2008. How bacteria consume their own exoskeletons (turnover and recycling of cell wall peptidoglycan). Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 72:211–227 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Patel S.S., Balfour J.A., and Bryson H.M. 1997. Fosfomycin tromethamine. A review of its antibacterial activity, pharmacokinetic properties and therapeutic efficacy as a single-dose oral treatment for acute uncomplicated lower urinary tract infections. Drugs. 53:637–656 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rahme L.G., Stevens E.J., Wolfort S.F., Shao J., Tompkins R.G., and Ausubel F.M. 1995. Common virulence factors for bacterial pathogenicity in plants and animals. Science. 268:1899–1902 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Raz R. 2012. Fosfomycin: an old-new antibiotic. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 18:4–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rife C.L., Pharris R.E., Newcomer M.E., and Armstrong R.N. 2002. Crystal structure of a genomically encoded fosfomycin resistance protein (FosA) at 1.19 A resolution by MAD phasing off the L-III edge of Tl(+). J. Am. Chem. Soc. 124:11001–11003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rigsby R.E., Rife C.L., Fillgrove K.L., Newcomer M.E., and Armstrong R.N. 2004. Phosphonoformate: a minimal transition state analogue inhibitor of the fosfomycin resistance protein, FosA. Biochemistry. 43:13666–13673 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Trapnell B.C., Mc Colley S.A., Kissner D.G., Rolfe M.W., Rosen J.M., McKevitt M., Moorehead L., Montgomery A.B., and Geller D.E. 2012. Fosfomycin/tobramycin for inhalation in patients with cystic fibrosis with pseudomonas airway infection. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 185:171–178 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Velkov T., Roberts K., Nation R., Thompson P., and Li J. 2013. Pharmacology of polymyxins: new insights into an ‘old’ class of antibiotics. Future Microbiol. 8:711–724 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yamada S., Hyo Y., Ohmori S., and Ohuchi M. 2007. Role of ciprofloxacin in its synergistic effect with fosfomycin on drug-resistant strains of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Chemotherapy. 53:202–209 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zamorano L., Reeve T.M., Deng L., Juan C., Moya B., Cabot G., Vocadlo D.J., Mark B.L., and Oliver A. 2010. NagZ inactivation prevents and reverts beta-lactam resistance, driven by AmpD and PBP 4 mutations, in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 54:3557–3563 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]